Abstract

The number of new cases of cancer is increasing each year, and rates of diabetes mellitus are also increasing dramatically over time. It is not an unusual occurrence for an individual to have both cancer and diabetes at the same time, given they are both individually common, and that one condition can increase the risk of the other. In this manuscript, we use national-level diabetes (Virtual Diabetes Register) and cancer (New Zealand Cancer Registry) data on nearly five million individuals over 44 million person-years of follow-up to examine the occurrence of cancer amongst a national prevalent cohort of patients with diabetes. We completed this analysis separately by cancer for the 24 most commonly diagnosed cancers in Aotearoa New Zealand, and then compared the occurrence of cancer among those with diabetes to those without diabetes. We found that the rate of cancer was highest amongst those with diabetes for 21 of the 24 most common cancers diagnosed over our study period, with excess risk among those with diabetes ranging between 11% (non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) and 236% (liver cancer). The cancers with the greatest difference in incidence between those with diabetes and those without diabetes tended to be within the endocrine or gastrointestinal system, and/or had a strong relationship with obesity. However, in an absolute sense, due to the volume of breast, colorectal and lung cancers, prevention of the more modest excess cancer risk among those with diabetes (16%, 22% and 48%, respectively) would lead to a substantial overall reduction in the total burden of cancer in the population. Our findings reinforce the fact that diabetes prevention activities are also cancer prevention activities, and must therefore be prioritised and resourced in tandem.

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of death globally and in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ), and its prevalence will rise as our population ages [1]. There are approximately 19 million new cancer cases each year, and almost 10 million cancer deaths [2]. Similar to other regions, recent projections indicate that there will be an approximate doubling of cancer patients aged 65 years and over, in the Oceania region by 2035 [3].

Rates of diabetes mellitus (hereafter diabetes) are also increasing dramatically over time, and are poised to increase by approximately 100 million cases over the next ten years [4]. Rates of diabetes are increasing in Aotearoa New Zealand by a staggering 7% per year [5]. In 2018, around 253,000 New Zealanders had some form of diabetes [6], with 90–95% of these likely to be Type 2 [7].

It is not an unusual occurrence for an individual to have both cancer and diabetes at the same time, given they are both individually common, and that one condition can increase the risk of the other [8–11]. Based on international evidence, we might expect approximately 35% of the population to be diagnosed with diabetes and 44% with cancer within their lifetime; with around 15% diagnosed with both [12].

The number of people diagnosed with cancer is projected to increase substantially over the coming decades–while simultaneously, the number of people living with diabetes will increase dramatically over the same period. Diabetes and cancer co-occurrence is likely to increase the complexity of the care of both conditions–in the context of cancer, the timing of diagnosis, access to treatment, and ultimately affect survival outcomes are impacted. Patients with diabetes are more likely to have cancer that is further advanced at diagnosis, compared to those without diabetes [13–15], while those patients with diabetes and localised cancer at diagnosis are more likely to develop metastases [16]. There is also evidence indicating that patients with diabetes are less likely to receive aggressive curative treatment for their cancer [17, 18]. People with diabetes have poorer survival from cancer [19, 20] (including women with breast cancer [15, 21]), with a large meta-analysis finding that cancer patients with diabetes were 41% more likely to die than cancer patients without diabetes [22].

Given the growing issue of diabetes and cancer co-occurrence, there is a need to better understand the burden of this co-occurrence at a population level and across the spectrum of cancer types. In Aotearoa New Zealand, we are well placed to provide robust evidence on the prevalence of cancer and diabetes co-occurrence at present, and also describe how this is patterned by cancer type, due to advantages in health care funding and the collection of health data, and its centralisation. In addition to the existence of a high-quality and mandated national Cancer Registry [23], Aotearoa New Zealand has a Virtual Diabetes Register, which uses national health data to ascribe diabetes status to every individual living in Aotearoa New Zealand [24]. This data capability is relatively unique in the international setting, and in the context of this study, allows us to measure the extent to which our population experiences diabetes and cancer co-occurrence.

Therefore, in this manuscript we use national-level data on nearly five million individuals over 44 million person-years of follow-up and describe the burden of cancer and diabetes co-occurrence. We examine the occurrence of cancer amongst a national prevalent cohort of patients with diabetes, separately by cancer for the 24 most commonly diagnosed cancers in Aotearoa New Zealand, and then compare this occurrence to those without diabetes.

Materials and methods

Participants and data sources

We used Statistics New Zealand’s Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) estimated resident population (ERP) for each year between 2008–2017 as our baseline population. We extracted annual national cohorts (or ‘annual cohorts’ / ‘risk sets’), beginning in the middle of 2008 through to the middle of 2018 (i.e. 10 individual annual cohorts, from 1st July through to 30th June of the next year). Diabetes status for each annual risk set was defined at the start of each annual period using data from the Virtual Diabetes Register (VDR, see below). Cancer incidence was also determined for each annual risk set to allow calculation of incidence of cancer among those with and without diabetes (total follow-up time: 43,967,454 person-years).

The methods underlying the VDR are detailed elsewhere [25]; but in brief, an algorithm is utilised to define diabetes prevalence within the population on the basis of national level data on inpatient hospitalisation ICD diagnosis codes (using the National Minimum Dataset, or NMDS), relevant outpatient events (National Non-Admitted Patient Collection, NNPAC), retinal screening (using regional retinal screening programme datasets), pharmaceutical dispensing (Pharmaceutical Claims dataset) and pathology test claims (Laboratory Claims dataset). The algorithm has been iteratively modified over time to improve sensitivity (around 90%) and specificity (around 96%), and has been validated against primary care registers [25, 26]. The VDR is used to determine official diagnosed diabetes prevalence in Aotearoa New Zealand, but does not differentiate between diabetes type [24].

Once we had set our annual cohorts and defined diabetes status, we utilised the IDI to link the cohorts to the New Zealand Cancer Registry (NZCR; follow-up period 2008–2018). The NZCR is a nationally-mandated population-based registry of all malignancies diagnosed in Aotearoa New Zealand, with the exception of basal and squamous cell skin cancers [23]. We initially searched for all malignancies (i.e. all ‘C’ codes within the International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-10-AM coding definitions [27]), and identified the 24 most commonly diagnosed cancers amongst the total cohort over the study period.

Variables

As noted above, diabetes status (with diabetes/without diabetes) was derived from the VDR, while cancer status was derived from the NZCR. Cancer type (e.g. lung cancer) was determined using site codes on the NZCR. Date of cancer diagnosis was derived from the NZCR. Age was determined as age at the start of the individual annual cohort, and derived from the IDI personal details table. Age was divided into seven categories (<20, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70+ years) for the purposes of age-standardisation. Sex (male/female) was also defined using the IDI personal details table.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis proceeded by constructing annual cohorts (defined above) which were then summed to provide person-time at risk across the entire study period. This approach was chosen to allow for handling of (a) censoring of follow-up time and (b) changes in diabetes status across the study period (time-varying covariate: diabetes status defined at the start of each annual cohort). These choices also reflected restrictions in the data available for analysis (see Discussion).

In terms of censoring, we utilised the estimated residential population to determine who is at risk using a constrained follow-up period. At the beginning of each mid-year cycle, the ERP removes those who died or emigrated during the previous 12 months, leaving just the numbers of those at risk in the subsequent period for our annual cohorts.

We calculated cancer incidence rates for both diabetes groups (with diabetes/without diabetes). The numerator for rate calculation was the number of cancers (in total, and by cancer type) occurring among patients with and without diabetes, both in total and stratified by sex. Because we wanted to calculate total cancer incidence, it was possible for an individual to have a number of different cancer types within each year, and the same individual could also end up with a second primary cancer of the same type in a subsequent year. The denominator was the number of person-years of follow-up time among patients with and without diabetes, in total and stratified by sex. Person-time of follow-up was calculated by summing the number of years of follow-up within each diabetes group (with/without diabetes) for each annual cohort, and then summing that time across all years of follow-up.

Rates of cancer incidence were age standardised using direct standardisation methods. Because rates of diabetes are disproportionately high amongst Māori (and Pacific) peoples in Aotearoa New Zealand [5], and because these populations have a substantially younger age structure than the non-Māori/non-Pacific population [28], we utilised the total Māori diabetes population over the study period as the standard. Finally, crude and age-standardised rate ratios (RRs) comparing the rate of cancer between those with and without diabetes were calculated using the age-standardised rates to be consistent in reporting ratios that were directly derived from the reported age-standardised rates (rather than age-adjusted RRs from regression modelling). RRs are presented with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Data analysis was completed in SAS Enterprise Guide v7.1 and SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., USA), and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, USA). Ethical approval for this study was sought and received from the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (reference # HD21/073). All data were de-identified prior to being made available by the Ministry of Health, and our ethical approval did not require informed consent for this retrospective analysis of national-level data.

Results

Overall trends

Age-standardised rates of cancer incidence among those with and without diabetes are shown in Fig 1, with the base data for the figure shown in S1 Table. Rate ratios comparing the rate of cancer incidence between the two groups are shown in Fig 2, with the base data for the figure shown in S2 Table. Overall, 176,055 individuals without diabetes developed cancer over the study period (age-standardised rate [ASR]: 875/100,000, 95% CI 870–879), along with 31,155 individuals with diabetes (ASR: 1,097/100,000, 1,084–1,111). When standardised for age, the rate of cancer was 25% higher among those with diabetes when compared to those without (age-standardised rate ratio [RR]: 1.25, 95% CI 1.24–1.27).

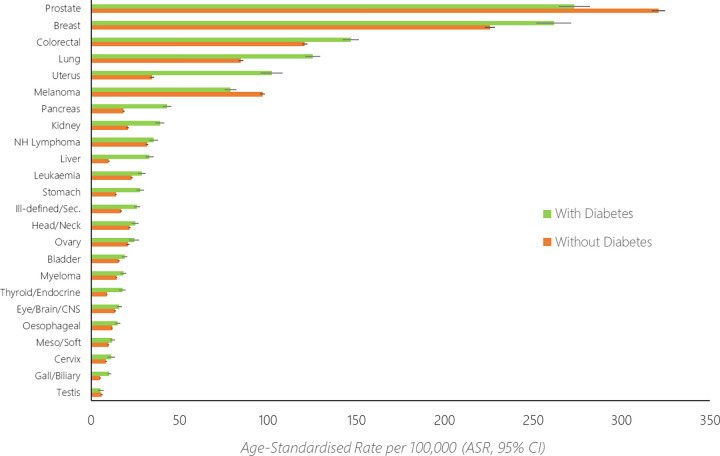

Fig 1. Age–standardised rates (ASR, 95% confidence intervals) of cancer amongst those with and without diabetes, for the 24 most commonly diagnosed cancers in Aotearoa New Zealand.

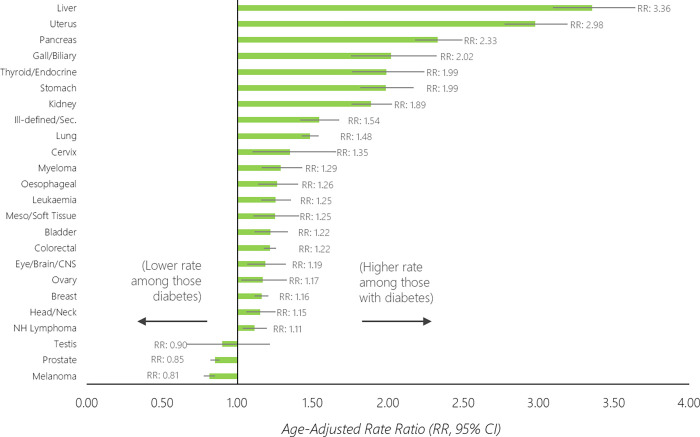

Fig 2. Age–standardised rate ratios (RR) of cancer between those with diabetes compared to those without diabetes (reference group), for the 24 most commonly diagnosed cancers in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The age-standardised rate (Figs 1 and 2) was highest for prostate (ASR: without diabetes, 321/100,000; with diabetes, 273/100,000), breast (ASR: without diabetes: 226/100,000, with diabetes 262/100,000), colorectal (ASR: without diabetes, 121/100,000; with diabetes 147/100,000), lung (ASR: without diabetes, 85/100,000; with diabetes, 125/100,000) and uterine cancers (ASR: without diabetes, 34/100,000; with diabetes 102/100,000). The relative difference in rates between those with diabetes compared to without diabetes was highest for liver (RR: 3.36, 95% CI 3.09–3.64), uterine (RR: 2.98, 95% CI 2.77–3.19), pancreatic (RR: 2.33, 95% CI 2.18–2.49), gallbladder/biliary (RR: 2.02, 95% CI 1.76–2.32) and thyroid/endocrine cancers (RR: 1.99, 95% CI 1.79–2.24). The cancer incidence rate was higher amongst those with diabetes compared to those without diabetes for 21 of the 24 investigated cancers (Figs 1 and 2).

Trends by sex

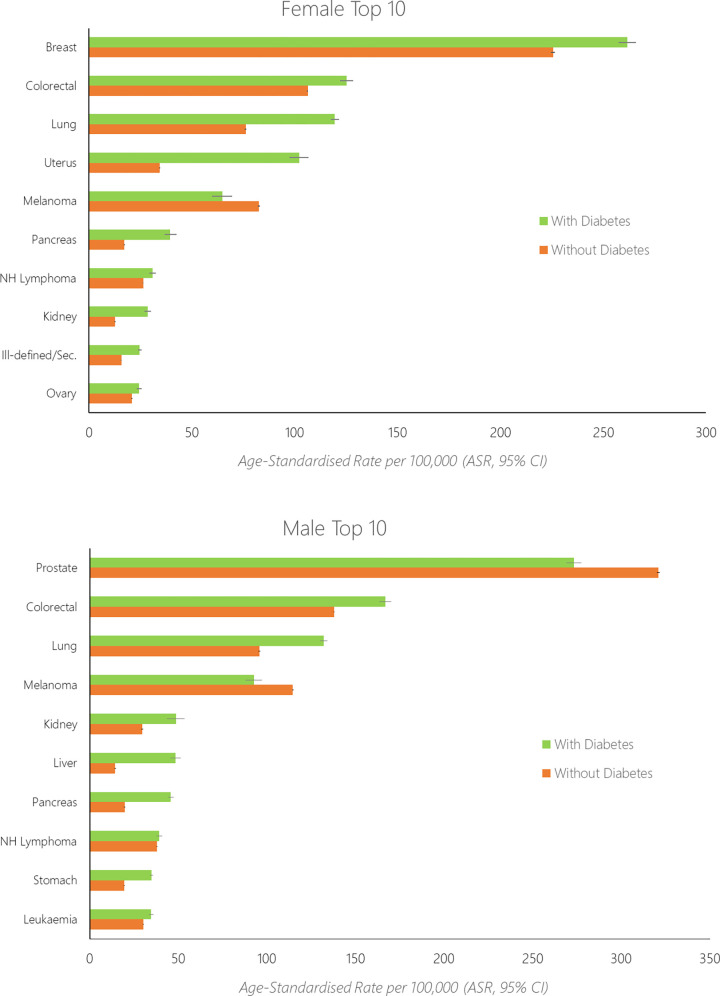

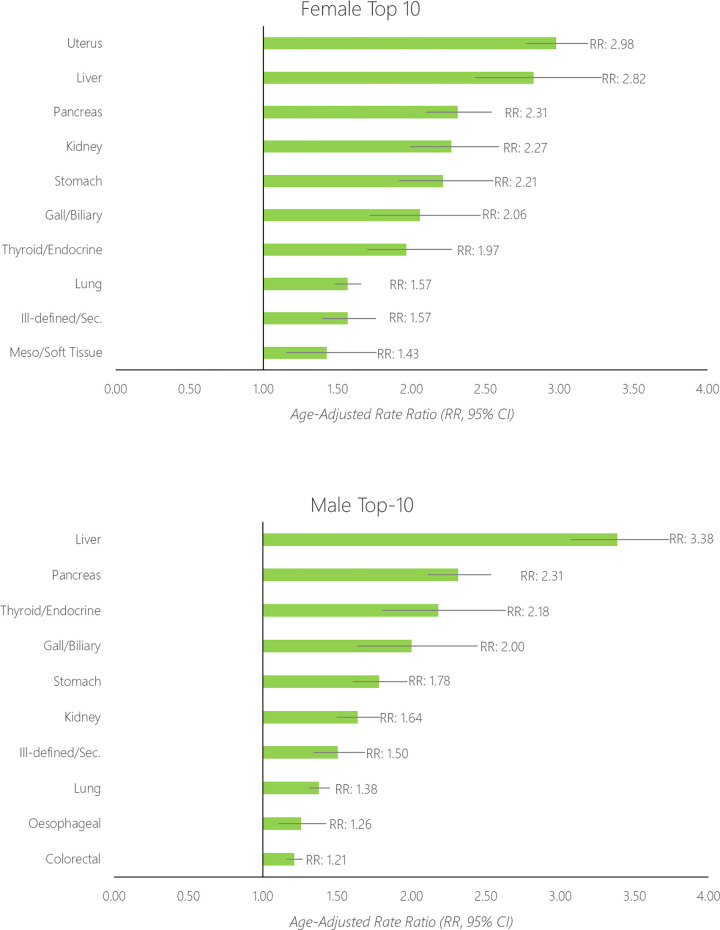

Age-standardised rates for the top-10 most common cancers among females and males with diabetes are shown in Fig 3 alongside data for those without diabetes, while rates for the full 24 cancers are shown in S3 Table. Sex-stratified rate ratios comparing the rate of cancer incidence between the two diabetes groups are shown in Fig 4.

Fig 3.

Age–standardised rates (ASR) of the top–10 cancers diagnosed among females (top) with diabetes and males (bottom) with diabetes, alongside data for those without diabetes.

Fig 4.

Age–standardised rate ratio (RR) of cancer between those with diabetes compared to those without diabetes (reference group), separately for the top–10 largest disparities for females (top) and males (bottom).

For females, overall the age-standardised rate of cancer was 761/100,000 individuals without diabetes, and 1,037/100,000 individuals with diabetes. The rate of cancer was 36% higher among females with diabetes compared to those without (age-standardised rate ratio [RR]: 1.36, 95% CI 1.34–1.39). The age-standardised rate was highest for breast (ASR: without diabetes, 226/100,000; with diabetes, 262/100,000), colorectal (ASR: without diabetes: 106/100,000, with diabetes 125/100,000), lung (ASR: without diabetes, 76/100,000; with diabetes 119/100,000), uterine (ASR: without diabetes, 34/100,000; with diabetes, 102/100,000) and melanoma cancers (ASR: without diabetes, 83/100,000; with diabetes 65/100,000). For females the relative difference in rate between those with diabetes compared to without diabetes was highest for uterine (RR: 2.98, 95% CI 2.77–3.19), liver (RR: 2.82, 95% CI 2.43–3.28), pancreatic (RR: 2.31, 95% CI 2.10–2.54), kidney (RR: 2.27, 95% CI 1.99–2.59) and stomach cancers (RR: 2.21, 95% CI 1.92–2.55).

For males, overall the age-standardised rate of cancer was 1,015/100,000 individuals without diabetes, and 1,156/100,000 individuals with diabetes. The rate of cancer was 14% higher among males with diabetes compared to those without (age-standardised rate ratio [RR]: 1.14, 95% CI 1.12–1.16). The age-standardised rate was highest for prostate (ASR: without diabetes, 321/100,000; with diabetes, 273/100,000), colorectal (ASR: without diabetes: 138/100,000, with diabetes 167/100,000), lung (ASR: without diabetes, 96/100,000; with diabetes 132/100,000), melanoma (ASR: without diabetes, 115/100,000; with diabetes, 93/100,000) and kidney cancers (ASR: without diabetes, 30/100,000; with diabetes 49/100,000). For males the relative difference in rate between those with diabetes compared to without diabetes was highest for liver (RR: 3.38, 95% CI 3.07–3.73), pancreatic (RR: 2.31, 95% CI 2.11–2.53), thyroid/endocrine (RR: 2.18, 95% CI 1.80–2.63), gallbladder/biliary tract (RR: 2.00, 95% CI 1.64–2.45) and stomach cancers (RR: 1.78, 95% CI 1.61–1.97).

Of the female-specific cancers, the strongest relative difference in cancer incidence between those with diabetes compared to those without diabetes, was found for uterine cancers (RR ~3). The rate of cervical cancers were approximately 35% higher among those with diabetes, and around 15% higher for both ovarian and breast cancers. Of the male-specific cancers, there was no difference in the rate of testicular cancer between those with diabetes and those without diabetes (RR: 0.90, 95% CI 0.66–1.22). The rate of prostate cancer was 15% lower among those with diabetes compared to those without (RR: 0.85, 95% CI 0.82–0.88).

Discussion

In this study, we utilised national prevalence data on diabetes alongside national incidence data on cancer to describe the co-occurrence of these conditions, and report the extent to which some cancers occur more commonly amongst those with diabetes, when compared to those without. We found that the cancers with the highest incidence rate among those with diabetes largely reflected the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the general population. For women, the three most commonly diagnosed cancers amongst those with diabetes were breast, colorectal and lung cancers, while for men it was prostate, colorectal and lung cancers.

We found that the rate of cancer is highest amongst those with diabetes for nearly all of the 24 most common cancers diagnosed over our study period. Only melanoma, prostate and testis cancers were more common amongst those without diabetes when compared to those with diabetes. The cancers with the greatest relative difference in incidence by diabetes status tended to be within the endocrine or gastrointestinal system (liver, pancreas, gallbladder, thyroid/endocrine, stomach), and/or had a strong relationship with obesity (uterus, kidney). This trend was observable for both males and females. These findings largely echo those of previous studies, which have found similarly elevated risk of cancer among those with diabetes as we have identified here (e.g. [29–34]).

These differences in cancer burden by diabetes status have multifactorial causes. Diabetes and cancer co-occur either because a) of shared risk factors, such as socioeconomic deprivation, obesity, and physical inactivity [35–38]; b) because of direct causation between diabetes and a given cancer [8–10, 39], or vice-versa [11]; and c) because both conditions occur relatively commonly in the population. For example, the patterning of elevated risk of gastrointestinal and endocrine tumours amongst those with diabetes supports existing evidence of a strong relationship between diabetes and these tumours, likely through shared risk factors but also (particularly in the case of pancreatic cancer) a direct causative relationship [32, 40–42]. The substantially higher rate of uterine cancer amongst those with diabetes is a reminder of the importance of addressing obesity (i.e. a shared risk factor) in reducing the occurrence of both Type-2 diabetes and obesity-related cancer, including uterine, breast and steatohepatitic liver cancer [43, 44]. It must be noted that the current study is not able to disentangle whether the increased risk of some cancers among those with diabetes is a direct consequence of their diabetes, or their diabetes is a direct consequence of their cancer, or due to some other reason. In this Discussion section we focus primarily on the ramifications of this increased risk. Because the vast majority of Type-2 diabetes cases are preventable [45], we might view the excess risk of most cancers experienced by these people as also being potentially preventable. In other words, for those cancers where diabetes is linked to tumour development either directly (as a risk factor itself) or indirectly (through shared risk factors, such as obesity), the prevention of Type-2 diabetes can be viewed as also preventative against the excess cases of cancer observed among those with diabetes in our study. Prevention of these cancers would perhaps have the most dramatic impact on those cancers with the starkest relative difference between those with and without diabetes–such as liver cancer, where incidence was 236% higher amongst those with diabetes compared to those without. However, in an absolute sense, due to the volume of breast, colorectal and lung cancers, prevention of the more modest excess cancer risk amongst those with diabetes (16%, 22% and 48%, respectively), would lead to a substantial overall reduction in the total burden of cancer in the population. This observation reinforces the fact that diabetes and obesity prevention activities are also cancer prevention activities, and must therefore be prioritised and resourced in tandem.

Further, the heightened risk of cancer amongst those with diabetes provides reasoning for this group to be considered prime candidates for cancer surveillance [30]. The increased contact with health care services for diabetes management presents a prime opportunity for these services to engage in evidence-based early cancer detection activities, including the promotion of national cancer screening programmes and a low threshold for primary care referral to secondary diagnostics when a patient presents with symptoms that may be either diabetes-derived or signs of cancer. The importance of this opportunity is underpinned by evidence that cancer patients with diabetes have poorer cancer-specific survival than cancer patients without diabetes [46–48]. Unfortunately, international evidence suggests that access to cancer screening and other surveillance amongst those with diabetes is either the same or poorer than those without diabetes [49, 50], suggesting we are missing valuable opportunities for early detection of cancers amongst patients with diabetes.

Our observation of substantially lower rates of prostate cancer amongst men with diabetes compared to men without diabetes, echoes similar findings from other studies [51–54]. It is thought that detection bias may be an important driver of this observation [51], in which increased access to prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening amongst those without diabetes may increase the number of prostate cancers diagnosed among this group.

Our observation of substantially lower rates of melanoma amongst those with diabetes, is somewhat contrary to other studies which have shown either heightened risk or no additional risk relative to those without diabetes [55, 56]. Our contrary observation may be related to the profile of patients diagnosed with diabetes in Aotearoa New Zealand, which is quite different to the profile of those diagnosed with melanoma skin cancer–wherein diabetes is much more common among Māori, Pacific and South Asian peoples than European peoples [6], and higher amongst those living in socioeconomic deprivation than for those not living in deprivation [57], whereas the opposite is true for the incidence of melanoma [58, 59]. The rarity of melanoma amongst these ethnic groups and/or those living in deprivation is likely to reduce the overall observed burden of melanoma among those with diabetes when data for all ethnic groups are pooled together. Ethnic disparities in diabetes and cancer co-occurrence are the focus of a separate study that we are currently undertaking with the data sources utilised for the current study, and we will aim to explore the relationship between diabetes and melanoma there.

Strengths and limitations

This national study utilised the total Aotearoa New Zealand population as the base, a relatively unique national dataset to determine diabetes status for all Aotearoa New Zealanders, and a national cancer register to determine cancer incidence. As such, our findings are generalizable to the total population of Aotearoa New Zealand and similar countries worldwide. Rather than studying new exposure to diabetes, diabetes status was defined based on a prevalent basis for each annual cohort, which may result in a bias in situations where the risk of an outcome is somewhat dependent on the duration of the exposure [60, 61]. Our annualised cohort approach, where diabetes exposure was reset each year, may have reduced the likelihood of this bias from occurring. Relatedly, the analysis approach of using annualised cohorts to analyse rates and rate ratios was partly dictated by these and other limitations of the available data (e.g. population data only updated on an annual basis), but closely aligns with a population-level analysis of cancer outcomes amongst those with diabetes, rather than an individual-level analysis of cancer outcomes (and their timings relative to diabetes onset) that might have been feasible if accurate diabetes onset/diagnosis information had been available.

We note that our study describes the co-occurrence of diabetes and cancer in purely descriptive terms, and does not take into account the mediating and/or confounding impact of other chronic conditions (including obesity) on cancer risk, nor the role of social determinants of health such as socioeconomic status, which limits our ability to make causal inferences regarding the relationship between the two conditions. Relatedly, while it is thought that drugs used to treat cancer may either cause diabetes or worsen pre-existing diabetes [62], the current study was designed to detect new cases of cancer amongst those already with diabetes, meaning that we were unable to examine reverse causation (i.e. the development of diabetes following a diagnosis of cancer). Finally, we could not differentiate between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes using the available data; and the available data only recorded sex as male or female.

Conclusions

In this national study of nearly five million individuals and 44 million person-years of follow-up, we found that the cancers with the highest incidence rate amongst those with diabetes largely reflected the cancers most commonly diagnosed within the general population. We found that the rate of cancer was highest amongst those with diabetes for 21 of the 24 most common cancers diagnosed over our study period, with excess risk among those with diabetes ranging between 11% (non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) and 236% (liver cancer). The cancers with the greatest difference in incidence between those with diabetes and those without, tended to be within the endocrine or gastrointestinal system, and/or had a strong relationship with obesity. However, in an absolute sense, due to the volume of breast, colorectal and lung cancers, prevention of the more modest excess cancer risk among those with diabetes (16%, 22% and 48%, respectively) would lead to a substantial overall reduction in the total burden of cancer in the population. Our findings reinforce the fact that diabetes prevention activities are also cancer prevention activities, and must therefore be prioritised and resourced in tandem.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

PY = person-years.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Ruth Cunningham for reviewing a draft of the manuscript. We would also like to thank Statistics New Zealand (Stats NZ) for facilitating access to the Integrated Data Infrastructure for the purposes of data extraction for this study. The research team takes full responsibility for the paper, Stats NZ will not be held accountable for any error or inaccurate findings within the paper or presentation, and access to data was in accordance with the Statistics Act 1975.

Data Availability

Data cannot be shared publicly because of data restrictions put in place by the New Zealand Government. The data underlying the results presented in this study are available from the Statistics New Zealand (Stats NZ) Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI), following a project review and approval process. For further information regarding access to these data, go to https://stats.govt.nz/integrated-data/apply-to-use-microdata-for-research/.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (HRC reference # 21/068). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilleron S, Sarfati D, Janssen-Heijnen M, Vignat J, Ferlay F, Bray F, et al. Global incidence of cancer in older adults in 2012 and 2035: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2018; doi: 10.1002/ijc.31664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2019;157:107843. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health. Living Well with Diabetes: A plan for people at high risk of or living with diabetes 2015–2020. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health Quality and Safety Commission. Atlas of Healthcare Variation—Diabetes. Wellington, New Zealand; 2020.

- 7.American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes care. 2015;38(Supplement 1):S8-S16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Friberg E, Orsini N, Mantzoros CS, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2007;50(7):1365–74. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0681-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartosch-Harlid A, Andersson R. Diabetes mellitus in pancreatic cancer and the need for diagnosis of asymptomatic disease. Pancreatology. 2010;10(4):423–8. doi: 10.1159/000264676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Extermann M. Interaction between comorbidity and cancer. Cancer Control. 2007;14(1):13–22. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwangbo Y, Kang D, Kang M, Kim S, Lee EK, Kim YA, et al. Incidence of Diabetes After Cancer Development: A Korean National Cohort Study. JAMA Oncology. 2018;4(8):1099–105. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carstensen B, Jørgensen ME, Friis S. The Epidemiology of Diabetes and Cancer. Current Diabetes Reports. 2014;14(10). doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0535-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipscombe LL, Fischer HD, Austin PC, Fu L, Jaakkimainen RL, Ginsburg O, et al. The association between diabetes and breast cancer stage at diagnosis: a population-based study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2015;150(3):613–20. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3323-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurney J, Sarfati D, Stanley J. The impact of patient comorbidity on cancer stage at diagnosis. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:1375–80. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peairs KS, Barone BB, Snyder CF, Yeh HC, Stein KB, Derr RL, et al. Diabetes mellitus and breast cancer outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(1):40–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du W, Simon MS. Racial disparities in treatment and survival of women with stage I-III breast cancer at a large academic medical center in metropolitan Detroit. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2005;91(3):243–8. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-0324-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renehan AG, Yeh HC, Johnson JA, Wild SH, Gale EAM, Møller H, et al. Diabetes and cancer (2): evaluating the impact of diabetes on mortality in patients with cancer. Diabetologia. 2012;55(6):1619–32. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2526-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross CP, McAvay GJ, Guo Z, Tinetti ME. The impact of chronic illnesses on the use and effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. Cancer. 2007;109(12):2410–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleeff J, Costello E, Jackson R, Halloran C, Greenhalf W, Ghaneh P, et al. The impact of diabetes mellitus on survival following resection and adjuvant chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(7):887–94. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsilidis K, Kasimis J, Lopez D, Ntzani E, Ioannidis J. Type 2 diabetes and cancer: umbrella review of meta-analyses of observation studies. Bmj. 2015;350:g7607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiderlen M, de Glas NA, Bastiaannet E, Engels CC, van de Water W, de Craen AJ, et al. Diabetes in relation to breast cancer relapse and all-cause mortality in elderly breast cancer patients: a FOCUS study analysis. Annals of Oncology. 2013;24(12):3011–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barone BB, Yeh HC, Snyder CF, Peairs KS, Stein KB, Derr RL, et al. Long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2008;300(23):2754–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Health. New Zealand Cancer Registry Wellington, New Zealand2020 [Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/nz-health-statistics/national-collections-and-surveys/collections/new-zealand-cancer-registry-nzcr].

- 24.Ministry of Health. Virtual Diabetes Register (VDR) Wellington, New Zealand2020 [Available from: http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/diabetes/about-diabetes/virtual-diabetes-register-vdr].

- 25.Jo EC, Drury PL. Development of a Virtual Diabetes Register using Information Technology in New Zealand. Healthcare Informatics Research. 2015;21(1):49–55. doi: 10.4258/hir.2015.21.1.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan WC, Papaconstantinou D, Lee M, Telfer K, Jo E, Drury PL, et al. Can administrative health utilisation data provide an accurate diabetes prevalence estimate for a geographical region? Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2018;139:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Centre for Classification in Health. The international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision, australian modification (ICD-10-AM/ACHI/ACS) (Third ed.). Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia: Independent Hospital Pricing Authority; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ministry of Health. Position paper on Māori health analytics–age standardisation. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beef and Lamb NZ. [Available from: http://www.beeflambnz.com/Documents/Information/nz-farm-facts-compendium-2016%20Web.pdf].

- 30.Xiao W, Huang J, Zhao C, Ding L, Wang X, Wu B. Diabetes and Risks of Right-Sided and Left-Sided Colon Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohorts. Frontiers in Oncology. 2022;12. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.737330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linkeviciute-Ulinskiene D, Patasius A, Zabuliene L, Stukas R, Smailyte G. Increased risk of site-specific cancer in people with type 2 diabetes: A national cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang HJ, Shan SB, Zhou YH, Zhong LY. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of gastrointestinal cancer in women compared with men: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1). doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4351-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin CC, Chiang JH, Li CI, Liu CS, Lin WY, Hsieh TF, et al. Cancer risks among patients with type 2 diabetes: A 10-year follow-up study of a nationwide population-based cohort in Taiwan. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1). doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ballotari P, Vicentini M, Manicardi V, Gallo M, Chiatamone Ranieri S, Greci M, et al. Diabetes and risk of cancer incidence: Results from a population-based cohort study in northern Italy. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1). doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3696-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, Renehan PAG, Stevens GA, Ezzati PM, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. The Lancet Oncology. 2015;16(1):36–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71123-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Attributable to Obesity Lyon, France2020 [Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/causes/obesity/home].

- 37.Connolly V, Unwin N, Sherriff P, Bilous R, Kelly W. Diabetes prevalence and socioeconomic status: a population based study showing increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in deprived areas. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2000;54(3):173–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.3.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Singh GK, Lin YD, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer causes & control: CCC. 2009;20(4):417–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabares-Seisdedos R, Dumont N, Baudot A, Valderas JM, Climent J, Valencia A, et al. No paradox, no progress: inverse cancer comorbidity in people with other complex diseases. Lancet Oncology. 2011;12(6):604–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70041-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jamal MM, Yoon EJ, Vega KJ, Hashemzadeh M, Chang KJ. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for gastrointestinal cancer among American veterans. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;15(42):5274–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Jong RGPJ, Peeters PJHL, Burden AM, de Bruin ML, Haak HR, Masclee AAM, et al. Gastrointestinal cancer incidence in type 2 diabetes mellitus; results from a large population-based cohort study in the UK. Cancer epidemiology. 2018;54:104–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin SW, Freedman ND, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Abnet CC. Prospective study of self-reported diabetes and risk of upper gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2011;20(5):954–61. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown JC, Carson TL, Thompson HJ, Agurs-Collins T. The Triple Health Threat of Diabetes, Obesity, and Cancer—Epidemiology, Disparities, Mechanisms, and Interventions. Obesity. 2021;29(6):954–9. doi: 10.1002/oby.23161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lega IC, Lipscombe LL. Review: Diabetes, Obesity, and Cancer-Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. Endocrine Reviews. 2020;41(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. Geneva, Switzerland; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu X, Ji J, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. The impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on cancer-specific survival: A follow-up study in Sweden. Cancer. 2012;118(5):1353–61. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El brahimi S, Smith ML, Pinheiro PS. Role of pre-existing type 2 diabetes in colorectal cancer survival among older Americans: a SEER-Medicare population-based study 2002–2011. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2019;34(8):1467–75. doi: 10.1007/s00384-019-03345-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lam C, Cronin K, Ballard R, Mariotto A. Differences in cancer survival among white and black cancer patients by presence of diabetes mellitus: Estimations based on SEER-Medicare-linked data resource. Cancer Medicine. 2018;7(7):3434–44. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calip GS, Yu O, Boudreau DM, Shao H, Oratz R, Richardson SB, et al. Diabetes and differences in detection of incident invasive breast cancer. Cancer Causes and Control. 2019;30(5):435–41. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01166-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao G, Ford ES, Ahluwalia IB, Li C, Mokdad AH. Prevalence and trends of receipt of cancer screenings among us women with diagnosed diabetes. Journal of general internal medicine. 2009;24(2):270–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0858-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feng X, Song M, Preston MA, Ma W, Hu Y, Pernar CH, et al. The association of diabetes with risk of prostate cancer defined by clinical and molecular features. British Journal of Cancer. 2020;123(4):657–65. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0910-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waters KM, Henderson BE, Stram DO, Wan P, Kolonel LN, Haiman CA. Association of diabetes with prostate cancer risk in the multiethnic cohort. American journal of epidemiology. 2009;169(8):937–45. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bansal D, Bhansali A, Kapil G, Undela K, Tiwari P. Type 2 diabetes and risk of prostate cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases. 2013;16(2):151–8. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2012.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wright JL, Stanford JL. Metformin use and prostate cancer in Caucasian men: Results from a population-based case-control study. Cancer Causes and Control. 2009;20(9):1617–22. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9407-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qi L, Qi X, Xiong H, Liu Q, Li J, Zhang Y, et al. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Risk of Malignant Melanoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2014;43(7):857–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tseng H-W, Shiue Y-L, Tsai K-W, Huang W-C, Tang P-L, Lam H-C. Risk of skin cancer in patients with diabetes mellitus: A nationwide retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(26):e4070–e. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ministry of Health. Annual Data Explorer 2020/21: New Zealand Health Survey Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2022 [Available from: https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2018-19-annual-data-explorer/.

- 58.Ministry of Health. Cancer: New registrations and deaths 2019 (tables). Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blakely T, Shaw C, Atkinson J, Tobias M, Bastiampillai N, Sloane K, et al. Cancer trends: trends in incidence by ethnic and socioeconomic group, New Zealand 1981–2004. Wellington: University of Otago and Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heaton B, Applebaum KM, Rothman KJ, Brooks DR, Heeren T, Dietrich T, et al. The influence of prevalent cohort bias in the association between periodontal disease progression and incident coronary heart disease. Annals of epidemiology. 2014;24(10):741–6. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brookmeyer R, Gail MH. Biases in Prevalent Cohorts. Biometrics. 1987;43(4):739–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vigneri P, Frasca F, Sciacca L, Pandini G, Vigneri R. Diabetes and cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2009;16(4):1103–23. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

PY = person-years.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

Data cannot be shared publicly because of data restrictions put in place by the New Zealand Government. The data underlying the results presented in this study are available from the Statistics New Zealand (Stats NZ) Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI), following a project review and approval process. For further information regarding access to these data, go to https://stats.govt.nz/integrated-data/apply-to-use-microdata-for-research/.