Significance

Marchantia polymorpha serves as an excellent model organism for studying the formation of basal complex multicellular structures in land plants. Gemma development is initiated from a single cell, which undergoes a series of spatially organized divisions to differentiate into meristem notches at each side of the gemma. Thus, notch formation provides a good system for investigating how the cell division pattern and subsequent differentiation processes are established during plant organogenesis. Genetic analysis indicates a critical role for M. polymorpha’s sole ROP gene (MpROP) in the regulation of developmental processes, including the spatial pattern of cell division and meristem formation in early gemma development. Our results reveal a function of ROP in the regulation of fundamental developmental processes.

Keywords: ROP GTPase, cell polarity, cell division, developmental axis, Marchantia

Abstract

The formation of cell polarity is essential for many developmental processes such as polar cell growth and spatial patterning of cell division. A plant-specific ROP (Rho-like GTPases from Plants) subfamily of conserved Rho GTPase plays a crucial role in the regulation of cell polarity. However, the functional study of ROPs in angiosperm is challenging because of their functional redundancy. The Marchantia polymorpha genome encodes a single ROP gene, MpROP, providing an excellent genetic system to study ROP-dependent signaling pathways. Mprop knockout mutants exhibited rhizoid growth defects, and MpROP was localized at the tip of elongating rhizoids, establishing a role for MpROP in the control of polar cell growth and its functional conservation in plants. Furthermore, the Mprop knockout mutant showed defects in the formation of meristem notches associated with disorganized cell division patterns. These results reveal a critical function of MpROP in the regulation of plant development. Interestingly, these phenotypes were complemented not only by MpROP but also Arabidopsis AtROP2, supporting the conservation of ROP’s function among land plants. Our results demonstrate a great potential for M. polymorpha as a powerful genetic system for functional and mechanistic elucidation of ROP signaling pathways during plant development.

The development of a multicellular organism requires precisely controlled cell division and cell specification. In Arabidopsis, the establishment of zygotic cell polarity is involved in the initiation of embryogenesis, and the subsequent spatially controlled cell division and cell specification determine the body axes and tissue/organ formation. Plants possess a unique single ROP subfamily of the conserved Rho family GTPases, including Rho, Cdc42, and Rac subfamilies in fungi, animals, and humans. Rho-like GTPases from Plants (ROPs) act as signaling hubs implicated not only in the regulation of cell polarity formation and cell morphogenesis in plants, as do fungal and animal Rho GTPases, but also in many other important plant processes such as plant hormone responses (1–5). However, whether ROP signaling pathways regulate the spatial pattern of cell division and meristem formation during embryogenesis and organogenesis in plants remains unclear.

Recently, Marchantia polymorpha, a bryophyte, has become an exciting but simple model system for genetic studies of basal developmental processes and organogenesis in plants (6–11). A large-scale screen for rhizoid-defective mutants in M. polymorpha in a previous study revealed conserved mechanisms for tip growth among land plants, such as cell wall synthesis and integrity sensing and vesicle trafficking (12). Knockout mutants for MpREN, an ortholog of Arabidopsis REN1 RhoGAP (GTPase-activating protein) that deactivates ROP1, exhibited a rhizoid growth defect, hinting at a role for MpROP in the regulation of rhizoid tip growth in M. polymorpha and fundamental cellular processes such as cell polarity formation. Genetic analyses of ROP signaling pathways in model angiosperm species such as Arabidopsis are challenging, and most of the functional studies of ROPs in developmental processes have been carried out in single-cell systems, such as pollen tubes and root hairs. Furthermore, the vast majority of the studies on ROPs involved overexpression or the use of constitutively active or dominant negative mutants because of functional redundancy among ROP members (13–15). The analysis of knockout mutants for all ROP genes has never been reported in any given angiosperm species. Arabidopsis contains 11 ROPs, but a limited number of knockout mutants, including rop2, rop3, and rop4, have revealed their roles in several developmental processes (16–19). The significance of ROP function during embryogenesis and organogenesis is largely unknown. M. polymorpha has a single ROP gene, MpROP, and the formation of some structures serves as a good model for investigating the mechanisms underlying basal developmental processes (e.g., gemma formation is a developmental process that is highly similar to embryogenesis or axillary meristem development in flowering plants) (20, 21). Here, our analysis using a loss-of-function mutant of a single MpROP gene revealed functions of ROP such as the regulation of spatially organized cell division in early gemma development and meristem notch formation in M polymorpha. Our results suggest a genetic system for the study of ROP signaling pathways in the regulation of plant developmental processes.

Results and Discussion

MpROP and ROP Genes in Land Plants.

MpROP (Mp7g17540) has a high similarity to Arabidopsis ROP genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The evolutionarily conserved domains in ROP proteins are all present in MpROP (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Phylogenetic analysis of ROPs from representative land plants indicated that ROP genes could be divided into three clades (SI Appendix, Dataset S1). MpROP belongs to clade I, suggesting that ROP from land plants originated in clade I, consistent with previous phylogenetic analyses including moss and lycophyte (22, 23). However, the amino acid sequence encoded by MpROP has the highest sequence identity with AtROP2 among the 11 Arabidopsis ROPs. Arabidopsis clade I ROP (AtROP7 and AtROP8) and AtROP2 regulate developmental processes such as xylem formation, root hair initiation, stomata opening, and pavement cell morphogenesis (14, 24, 25), processes that are not required for M. polymorpha growth and development, thus suggesting that MpROP may regulate developmental processes different from those modulated by Arabidopsis clade I ROP, AtROP7 and AtROP8, and AtROP2.

MpROP Regulates Polar Cell Growth of Rhizoids.

We designed CRISPR target sites for exons 1 and 3 of MpROP and generated two independent CRISPR knockout mutants, Mprop-1 and Mprop-2 (Fig. 1 A and B). Both Mprop-1 and Mprop-2 mutants showed severe morphological defects and overall reduction in plant size (Fig. 1C). The total number of rhizoid initial cells was significantly lower in the Mprop mutants than in the wild type (WT) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B), which is consistent with spare rhizoids in gemmalings (Fig. 1D). However, the ratio between total cell number and rhizoid initial cells was not different between Mprop mutants and WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). Importantly, rhizoid elongation was dramatically retarded (Fig. 1 D and F). Rhizoid development and growth in bryophytes are thought to be highly similar to those of root hairs and pollen tubes in angiosperm, involving the selection of polar sites for outgrowth and subsequent polarized cell elongation known as tip growth, which are both known to be governed by ROP GTPase signaling in model plant species of angiosperms (6, 26, 27). Here, defective rhizoid growth in the Mprop mutant showed direct evidence that evolutionally conserved ROPs function in polar tip growth in land plants. Therefore, the Mprop mutant phenotypes suggest the great potential of M. polymorpha as a powerful genetic system to dissect the basal mechanism by which ROP GTPase signaling controls cell polarity establishment in plant development.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of Mprop knockout mutant plants. (A) Schematic representation of the MpROP (Mp7g17540) genomic locus and CRISPR target sites in the MpROP gene. Gray boxes indicate untranslated regions. Red boxes and gray lines indicate exons and introns of the MpROP gene, respectively. The Mprop-1 and Mprop-2 mutants have 6-bp deletion in the third exon and single nucleotide (T) insertion in the first exon of MpROP gene, respectively. (B) The alignment of amino acid sequence of mutation sites of Mprop-1, Mprop-2, and MpROP. The numbers indicate the distance of the translation starts (ATG, which encodes methionine) in genomic DNA. * indicates translational termination of Mprop-1. The changed amino acid residues in Mprop-1, Mprop-2 are shown in a different color. (C) The images of 1-mo-old WT, Mprop-1, Mprop-2, and complementation lines carrying proMpROP:MpROPCRISPRr or proMpEF1:MpROPCRISPRr in the Mprop-1 background. Top: shows whole plants; scale bar, 16 mm. Bottom: shows detached thallus with gemma cup; scale bar, 5 mm. Red arrows indicate the gemma cups. (D) Images of rhizoid growth. Three-day-old gemmaling of WT, Mprop-1, Mprop-2, and complementation lines carrying proMpROP:MpROPCRISPRr or proMpEF1:MpROPCRISPRr in the Mprop-1 background were used for the photos. Scale bar, 500 μm. (E) Images of WT, Mprop-1, Mprop-2, and complementation lines carrying proMpROP:MpROPCRISPRr or proMpEF1:MpROPCRISPRr in the Mprop-1 background showing premature and postmature gemmae. Gemmae were taken out of the gemma cup for the photos. The premature and postmature were classified according to size. Scale bar, 500 μm. * indicates the connection part of the gemma with the gemma cup. The arrowheads indicate the meristem notch. (F) Quantitative analysis of maximum rhizoid length of the gemmaling shown in D. Values are mean ± SEM; n > 8. (G) Gemma number in each gemma cup. n > 15 (n represents individual cups). (H) Gemma cup number per branch of thallus. n > 5 (n represents individual plants). Values are mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate significant difference (one-way ANOVA post hoc Tukey’s honest significant difference test, P < 0.01).

MpROP Is Essential for Meristem Notch Formation during Gemma Development.

Gemmae in WT M. polymorpha have two meristem notches, resulting in bidirectional growth along the left and right axes at the gemmaling stage (Fig. 1E). The mature thallus in WT produces asexual reproductive organs, gemmae, inside of the gemma cup on the dorsal side of the thallus. In both Mprop-1 and Mprop-2 mutants, gemma cups were only occasionally observed, and the mutant gemma cups generated few gemmae (Fig. 1 C, G, and H). Mprop mutant gemmae did not have meristem notches, suggesting the disruption of axis formation for symmetrical morphogenesis (Fig. 1E). At the mature thallus, a meristem notch-like structure was observed in the Mprop mutant (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B). Scanning electron microscopy analysis further revealed the detailed phenotype of the Mprop mutant, such as lack of a clear meristem notch, a jagged margin, and abnormal epidermal cells without an air pore in 1-mo-old plants (Fig. 2A). Importantly, the developmental phenotypes described above were all observed in both Mprop-1 and Mprop-2 alleles (Figs. 1 C–H and 2A), strongly suggesting that mutations in the MpROP gene caused these phenotypes. Furthermore, all of the morphological abnormal phenotypes of the Mprop-1 mutant were restored in the complementation lines carrying proMpROP:MpROPCRISPRr (CRISPR resistance MpROP) or proMpEF1:MpROPCRISPRr in Mprop-1 (Figs. 1 C–H and 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A–D). Thus, we concluded that the mutant phenotypes described above were caused by loss of function of the MpROP gene. Consistent with the decreased gemma formation in Mprop mutants, the analysis of the proMpROP:GUS line showed that expression was especially high in the entire gemma cup, gemmae in the early stage of gemma development, and meristem notch (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). These results are consistent with qPCR analysis of MpROP transcripts (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 C and D). MpROP expression was not detectable after the postmature stage of gemma development during gemma dormancy but reappeared around meristem notches during the gemmaling stage (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Hence, the expression of MpROP seemed to be associated with active cell division and gemma growth in young tissues.

Fig. 2.

The detailed characterization of developmental phenotypes in Mprop knockout mutants. (A) Scanning electron micrographs of 1-mo-old WT, Mprop-1, Mprop-2, and complementation lines carrying proMpROP:MpROPCRISPRr or proMpEF1:MpROPCRISPRr in the Mprop-1 background. Top: shows meristem notch. Scale bar, 1 mm. Middle: shows gemma cup. Scale bar, 1 mm. Bottom: shows surface of the thallus with air pore. Scale bar, 0.2 mm. Images of WT and Mprop-1 were also taken by a dissect microscope and are shown as inserted pictures. Scale bar, 0.5 mm. (B) Confocal images of developing gemma and gemma cup of the WT, Mprop-1, Mprop-2, and complementation lines carrying proMpROP:MpROPCRISPRr or proMpEF1:MpROPCRISPRr in the Mprop-1 mutant background with PI staining. Top: shows the whole gemma cup. Scale bar, 200 µm. Middle: shows abnormal cells (in yellow) and papilla cell with higher magnification. Scale bar, 50µm. Bottom: shows gemmae with higher magnification. The gemma-like clustered cells in mutants are marked in red. Scale bar, 50 µm. (C) The gemmaling of the Mprop-1 mutant shows a defect in cell division pattern at 2 and 6 d. For the 2-d-old plants, the left column shows the image of whole plants. Images 1 and 3 show the margin cells at the meristem region. Images 2 and 4 show the margin cells away from the meristem notch. For the 6-d-old plants, the two upper panels in the left column show the image of WT and Mprop-1 in lower magnification. The close-up views of the boxed area are shown as separate images. Images 5 (red arrow) and 6 show margin cells at the meristem region. Image 7 shows the margin cells away from the meristem notch. Arrowheads indicate the outermost cell layer in the WT and Mprop-1 mutant in the meristem notch region. (D) Cell division analysis of the outer cell layers in the meristem notch region in the WT and Mprop-1 mutant. The images show representative cell division analysis. The boundary of the mother cell is outlined in yellow. The yellow dot indicates the center of mass. The yellow line indicates the default division plane. The red line indicates the actual division plane. (E) The difference (Δθ) between the division plane predicted from the physical rule and the actual division plane. The individual data points are shown as dots in the bar graph. Values are mean ± SD (n = 27 for mutants, N = 19 for WT (unpaired t test with Welch’s correction, *P = 0.0158). (F) The histogram of the difference between the division plane predicted from the physical rule and the actual division plane. Δθ indicates the angle between the division plane predicted from the physical rule and the actual division plane. The greater the Δθ, the more deviation of the actual division plane from the predicted plane.

ROP signaling is involved in auxin-related developmental pathways in angiosperms (28–31). Interestingly, auxin plays an important role in axis formation in gemma development (27). AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR1 (ARF1) knockout mutant, Mparf1, showed various numbers of meristem notches (20), and the auxin biosynthesis gene, YUC2, is highly expressed at the meristem notch in M. polymorpha (32). We observed that YUC2 expression in the Mprop mutant was significantly decreased compared with that of WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), supporting a link between ROP signaling and auxin in meristem notch development. In addition, auxin has a pivotal role in the regulation of gemma dormancy (32). After the maturation process, gemmae undergo a period with temporary suspension of visible growth until the gemmae come out from the gemma cup (33). Interestingly, Mprop mutant gemmae started forming rhizoids and thallus when the gemmae were still inside the gemma cup (Fig. 1E). The dormancy defect in the Mprop mutants may also be associated with the defect in meristem notch formation. The dormancy was promoted by auxin coming from the thallus (32). However, the relationship between low-level expression of YUC2 and meristem notch formation in the Mprop mutant is still not clear. The relationship between ROP and auxin during meristem notch formation will need to be elucidated.

MpROP Regulates the Spatial Pattern of Cell Division.

Analogous to early embryogenesis in angiosperms involving polar zygote elongation and subsequent oriented cell division, gemma development also starts with the elongation of a single initial cell, which then divides transversely into basal and apical cells (28). The basal cell becomes a stalk cell, while the apical cell undergoes further oriented division to form gemma bearing two meristem notches, one each at the right and left axes, respectively (34, 35). Because the Mprop mutant failed to form the correct axis in gemma development (Fig. 1E), we examined its cell division pattern during early gemma development using confocal microscopy analysis of PI (propidium iodide)-stained plants (Fig. 2B). As described above, Mprop mutants generated few gemmae in the gemma cup (Figs. 1C and 2 A and B). We failed to observe any initial stage of gemmae with a normal cell division pattern in Mprop mutants (Fig. 2B). Instead of gemmae and secretory hair (papilla cells), the Mprop mutant had a number of abnormally proliferated small cells at the bottom of the gemma cup (Fig. 2B, Middle and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). These small cells sometimes formed a cluster of stacked cells (Fig. 2B, Bottom). These clustered cells seemed to be at the initial stage of gemma formation, with random division orientation in the Mprop mutant (Fig. 2B, Bottom). Importantly, these abnormal cell phenotypes in the Mprop mutant were also clearly restored in the complementation lines (Fig. 2B).

An organized spatial pattern of cell division is necessary for meristem formation and organ development in plants. Sequential cell division at the meristem notch further promotes thalli formation (36). Next, we observed cell division patterns in gemmaling in detail (Fig. 2C). The margin of the WT thallus is smooth and has an organized layer of cells with anticlinal division planes (Fig. 2C, Middle). In contrast, the Mprop mutant exhibited a rough thallus margin with cells having randomly oriented division planes (Fig. 2C, Middle) and cells with random shapes (Fig. 2C, Middle), suggesting disruption of the spatial cell division pattern in the Mprop mutant. The margin area of the Mprop mutant eventually formed a meristem notch-like structure in a subsequent developmental process (Fig. 2A). However, the Mprop mutant did not seem to have an organized cell division pattern at the notch-like area, unlike the meristem notch area of the WT (Fig. 2C). These observations suggest that MpROP signaling regulates the spatial pattern of cell division either by transmitting a developmental signal that controls the orientation of cell division during meristem notch development or by modulating the shape of cells that subsequently impacts cell division orientation. The default mechanism for determining the orientation of cell division follows a physical rule (i.e., the plane of division aligns with the shortest path that crosses the center of the cell mass in a two-dimensional cell) (37). This physical rule is overridden by a specific developmental signal that generates formative cell division, typically occurring during the formation of a new organ. If MpROP directly transmits such a developmental signal to regulate the orientation of cell division during notch meristem development, we anticipate that WT cells will not follow the physical rule, whereas Mprop mutant cells will. We compared the actual plane of cell division with that predicted from the physical rule using the mathematical model (37) and used Δθ to describe the deviation of the actual cell division plane from the one predicted by the physical rule (Fig. 2D). As shown in Fig. 2 E and F, the division plane of cells in the meristematic region greatly deviated from that predicted by the physical rule in WT. In WT, the angle between the predicted default and actual division plane was quite variable, but the mean of Δθ was around 40 (Fig. 2E). In contrast, the angle was much smaller (Δθ < 20) in most of the cells in the Mprop-1 mutant (Fig. 2F). These results support the hypothesis that MpROP is critical for determining formative cell division during the formation of notch meristem in Marchantia.

The cytoskeleton plays an important role in the spatial regulation of cell division (38, 39) and is known to be regulated by ROP signaling in Arabidopsis (17, 40). To further characterize a subcellular defect associated with the disorganized cell division pattern of the Mprop-1 mutant, we observed microtubules (MT) in the notch-like area in the Mprop mutant and the meristem notch area of the WT in 2-d-old gemmalings by immunostaining. The dividing cells were often observed in the area in Mprop-1 and WT, supporting active cell division in the area we observed. We further quantified the orientation of cell division by measuring the angle of mitotic spindles or polar organizer relative to the direction of the meristem notch. The orientation of cell division was mostly in parallel with the direction of margin in the WT, but much more random in the Mprop-1 mutant (Fig. 3 A and C). These results provide further strong support for the crucial role of MpROP in the spatial pattern of cell division during meristem notch formation. Although cortical microtubules were observed in both the WT and Mprop-1 mutant, their orientation tended to be more random in Mprop-1 cells compared to WT cells (Fig. 3B). The anisotropy of cortical microtubules was quantified by FibrilTool (41, 42). We found that anisotropy of microtubules was significantly reduced in the Mprop-1 mutant compared with the WT (Fig. 3 B and D). These results suggest that like Arabidopsis ROP6 (17), MpROP regulates the organization of ordered cortical microtubules, which are important for the proper formation of preprophase bands that predicts the position and orientation of cell division planes. Unfortunately, we were unable to observe preprophase bands in immunostained cells and to determine whether preprophase bands were altered in the Mprop1 mutants.

Fig. 3.

Severe defects in cell division pattern and MT array in the early gemma of the Mprop mutant. (A) Images of the cell division angle to the margin cell layer direction. The lines indicate the meristem notch direction. The doubled-up arrows indicate the direction of cell division by spindle or polar organizer during mitosis. (B) The cortical MT organization into ordered arrays is indicated by MT anisotropy in the WT and Mprop-1 mutant. The length of the line is proportional to the array anisotropy. Scale bar, 20 µm. (C) Quantification of the cell division angle to the margin cell layer. Values are mean ± SEM. Significance of Mprop-1 mutant against WT was tested with a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (***P < 0.001). (D) Quantitative data of the MT anisotropy in B. Values are mean ± SEM. Significance of Mprop-1 mutant against WT was tested with a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test (****P < 0.0001).

Subcellular Localization of MpROP Supports Its Conserved Function in the Regulation of Cell Polarization.

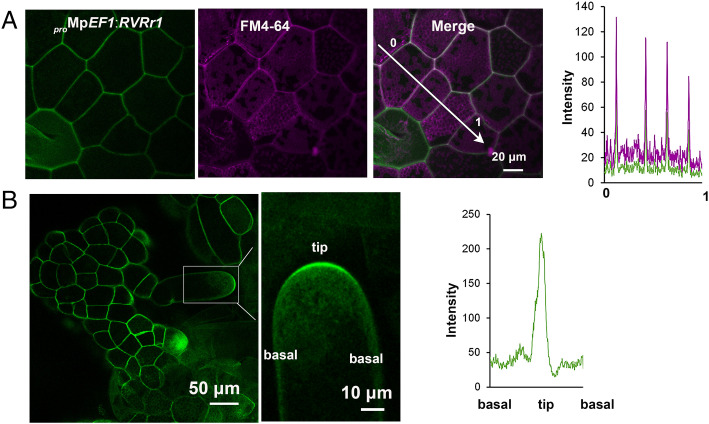

We next assessed whether the subcellular distribution of MpROP supports its role in the spatial regulation of cell growth and division. We generated transgenic lines carrying Venus-tagged MpROP, proMpEF1:RVRr1 (promoter MpEF1α:MpROPN CRISPR resistance-Venus-MpROPC) in Mprop-1 mutant background (described in Methods). The expression of proMpEF1:RVRr1 significantly restored the developmental phenotype of the Mprop-1 mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), such as short rhizoid, gemma formation, and thallus growth, except for the frequency of gemma cup formation in the mature thallus (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). These results show that Venus-MpROP expressed under proMpEF1:RVRr1 is functional. As shown for ROP localization in Arabidopsis, Venus-MpROP was localized to the plasma membrane, which was costained by fn4-64 in cells of the young thallus (Fig. 4A). The differential distribution of ROPs along the plasma membrane is important for developing the characteristic pavement cell shape with multiple lobes and indentations in Arabidopsis epidermal cells (17). In contrast, the differential distribution of MpROP along the PM (plasma membrane) was not observed in the epidermal cells of thallus lacking the jigsaw puzzle shape (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

Fig. 4.

Subcellular localization of MpROP. (A and B) Confocal images of proMpEF1:MpRop(N)-Venus-MpRop(C) (proMpEF1:RVRr1) expression in epidermal cells (A) or rhizoid cells (B) of the Mprop-1 mutant. The cell membrane was visualized by fn4-64 staining. (A) The graph shows the fluorescence intensity of Venus-MpROP (green) and fn4-64 (purple) along the arrow in the right image corresponding with the numbers. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Right image: the close up-view of the boxed area is shown. The graph shows the fluorescence intensity of Venus-MpROP along the cell membrane of the rhizoid in the rhizoid tip (left image). Scale bar, 50 μm in the left image and 10 μm in the right image.

We found that Venus-MpROP was preferentially localized to the apical plasma membrane in the growing rhizoids, indicating polar localization of MpROP during the early stage of rhizoid growth (Fig. 4B). ROP is localized to the apex of tip-growing cells, such as growing pollen tube and root hair, to establish cell polarity and regulate tip growth (14, 43). Together with the strong defect in rhizoid growth in Mprop mutants, our results strongly support the idea that polar localization of MpROP is important for polar growth in rhizoid elongation. ROP interacting proteins, RICs (ROP interactive CRIB motif–containing proteins)/ICRs (Interactor of constitutive active ROPs), are often involved in the establishment of polar localization of ROP in tip-growing cells (43). However, M. polymorpha does not have RICs/ICRs (SI Appendix, Table S1), suggesting the existence of some unknown effectors that play a basal function in the regulation of tip growth.

The Single MpROP Is Activated by Multiple RopGEFs Including the KAR MpRopGEF.

The activation of ROPs by the Arabidopsis RopGEF guanine nucleotide exchange factors results in a conformational change in the highly flexible switch I and switch II motifs of ROPs involved in the interaction with ROP regulators and effectors (44–47). The M. polymorpha MpRopGEF protein has a conserved plant-specific ROP regulator and ROP nucleotide exchanger (PRONE) domain for GEF activity (48). MpRopGEF was originally identified as a causal gene of karappo (kar) knockout mutant (48), which showed overlapping phenotypes (defects in gemma development) with Mprop mutants. Interestingly Mprop-1 with a 6-bp deletion in the third exon of MpROP resulted in the removal of two amino acid residues in switch II (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Our yeast two-hybrid analysis showed that the mutant Mprop-1 protein failed to interact with the MpROPGEF protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). These results explain why Mprop-1 exhibited the same severe phenotypes as the null Mprop-2 mutant (Figs. 1 C–H and 2 A and B) and further confirm the role of MpRopGEF in activating MpROP for its function in gemma development and the functional conservation of ROP’s switch II in M. polymorpha and Arabidopsis thaliana.

As described above, Mprop mutants have many severe developmental defects in other organs in addition to the gemma defect shared by kar (Figs. 1 C–H and 2 A–C) (48). These contrasting phenotypes suggest that apart from the KAR MpRopGEF (the PRONE domain containing GEF), MpROP is likely activated by other activators. One such potential activator is SPK1 (SPIKE1, the lone DOCK family GEF), whose homolog (MpSPK1) is present in M. polymorpha (SI Appendix, Fig. S10) (49). However, the yeast two-hybrid assay failed to detect an interaction between MpROP and SPK1 in yeast (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A and B). M. polymorpha also has a homolog of another Rho GEF, SWAP70, that is conserved in animals and plants (50, 51) (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Further genetic and biochemical studies should determine whether MpSPK1 and MpSWAP70 indeed act as MpROP activators and how they differentially or coordinately activate single ROP to modulate different developmental processes in Marchantia.

The Functional Conservation of ROP Signaling between M. polymorpha and A. thaliana.

As shown above, the MpROP amino acid sequence is highly similar to Arabidopsis ROPs genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), and MpROP has a role in the regulation of polar cell growth, a fundamental process regulated by ROP GTPases in many plant species. To further assess the functional conservation of ROPs, we performed complementation analysis of the Mprop-1 mutant by using the Arabidopsis AtROP2 (CRISPR resistance; SI Appendix, Fig. S2D) gene driven by the MpEF1α promoter. Introduction of proMpEF1:AtROP2 restored the developmental defects in the Mprop-1 mutant described above, such as meristem notch formation and rhizoid elongation (Fig. 5 A–C), suggesting that the function of AtROP2 and MpROP are evolutionally conserved not only in tip growth but also in other developmental processes. MpROP was also able to interact with one of Arabidopsis ROP effector RICs in yeast (Fig. 5D). We further tested whether MpROP expression caused developmental defects in Arabidopsis. AtROP2 controls the formation of the puzzle piece cell shape in leaf epidermal pavement cells through the regulation of actin and microtubule dynamics (15). Overexpression of the constitutive active-form AtCAROP2 (Q64L) caused reduction of the interdigitation pattern of pavement cells (52). We observed that expression of MpCAROP (Q64L) also caused the aberrant pavement cell shape, similar to that induced by Arabidopsis CAROP2 (Q64L) (Fig. 5 E–G). These results further suggest that the functions of ROPs are broadly conserved among land plants. In most land plants, multiple ROPs have evolved to control not only the conserved function but also presumably more specialized functions necessary for complex developmental processes. However, single ROP is sufficient to control many developmental processes in M. polymorpha, and this function of MpROP is conserved in AtROP2.

Fig. 5.

The function of ROP is conserved between M. polymorpha and Arabidopsis. (A) Top: images of 1-mo-old plants; Middle: mature gemmae; Bottom: 3-d-old rhizoids in WT, Mprop-1, proMpEF1:AtROP2CRISPRr/Mprop-1line #1, and line #2. Scale bar, 16 mm (Top), 500 μm (Middle and Bottom). * indicates the connection part with the gemma cup. Arrowheads indicate the meristem notch. (B) Image of 4-wk-old thallus of, proMpEF1:AtROP2CRISPRr/Mprop-1. Scale bar, 2 mm. The red and blue arrows indicate the gemma cup and meristem notch, respectively. (C) Quantitative analysis of maximum rhizoid length of the gemmalings shown in A. Values are mean ± SEM, n > 9. Different letters indicate significant difference (one-way ANOVA post hoc Tukey’s honest significant difference test, P < 0.01). (D) MpROP interacts with AtRIC2. Two-hybrid assays of MpROP and AtRIC2. BD and AD indicate the binding domain in pGBKT7 and activation domain in pGADT7, respectively. Yeast was grown on selective medium lacking Leu and Trp (SD-LW) to verify the presence of both plasmids or in selective medium lacking Ade, His, Leu, and Trp (SD-LWHA) to test protein interactions. N means negative control fused with SV40 large T-antigen in AD and lamin in BD. EV means empty vector. (E) Images of cotyledon pavement cells of col-0, 35S:AtCAROP2, and 35S:MpCAROP in Arabidopsis; 3-d-old plants were stained with fn1-43 and observed. MpCAROPQ64L was used as the constitutively active protein of MpROP. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) Quantitative analysis of pavement cells. The number of lobes shown in E was counted. Values are mean ± SEM; ***P < 0.001 compared with col-0 using two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test, n > 40. No lobes were observed in 35S:AtCAROP2 transgenic lines. (G) Alignment of the amino acid sequence of MpROP and AtROP2. The mutation site, Q64L (constitutively active form), is indicated with a red line.

M. polymorpha: A Simple Model System to Study ROP Signaling in Regulating the Spatial Pattern of Cell Division and Meristem Formation.

Our genetic analysis revealed critical roles for the MpROP protein in the regulation of multiple developmental processes in the bryophyte M. polymorpha, including processes conserved in all eukaryotic organisms, such as polar cell growth as well as developmental and morphogenetic processes requiring the spatial control of cell division in early gemma development and meristem notch formation (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). A single ROP is sufficient to regulate a broad range of developmental processes in M. polymorpha. In contrast, multiple ROPs have evolved to regulate distinct biological processes in model plant species of angiosperm (2, 4). How does a single MpROP regulate a broad range of biological processes such as rhizoid elongation, spatial cell division pattern during gemma formation, and meristem notch formation? One possible explanation is that ROP controls a fundamental cellular process, such as the formation of cell polarity, that impacts multiple developmental processes (2). Alternatively, ROP is a central component of a crucial signaling pathway that controls multiple distinct processes or participates in multiple signaling pathways. The existence of multiple functionally distinct RopGEFs in M. polymorpha supports the latter. ROPs are key signaling components of cell surface auxin signaling, which regulates multiple cell and developmental processes in Arabidopsis (28–31). Our results also suggest a possible association of MpROP with auxin function (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). A tantalizing question is whether MpROP signaling directly participates in the regulation of patterned cell division in meristem notch formation controlled by auxin. Interestingly, cell surface auxin signaling and ROPs have both been suggested to modulate the spatial pattern of cell division in Arabidopsis (53), but it is unclear whether ROP-based auxin signaling governs this process. The single MpROP in M. polymorpha may provide an excellent system to dissect the complex relationship between auxin and regulation of the spatial pattern of cell division and subsequent meristem formation in plant development. Characterization of putative RopGEFs such as MpSPK1 and MpSWAP70 may eventually lead to the identification of upstream signals of MpROP signaling pathways that determine functional diversity of the single ROP in M. polymorpha. Interestingly, additional meristem notch formation was previously observed in gemmae of the kar mutant when the KAR (MpROPGEF) gene was expressed; however, its knockout mutant (kar) does not exhibit a defect in notch formation (48), suggesting the presence of additional GEF in M. polymorpha that may be functionally redundant with KAR to activate MpROP during notch formation. Together, these results strongly indicate a tight connection between meristem notch formation and ROP signaling pathways, most likely via its regulation of cell division pattern.

ROP signaling in the spatial regulation of cell division appears to be a common underlying mechanism regulating different developmental processes in plants. In addition to the gemma development and meristematic notch formation described above, ROPs have also been implicated in the spatial regulation of several developmental processes in other plant species (54–57). In Physcomitrium patens, ROP and actin are essential for nuclear positioning and cell division in side-branch formation (57). In Arabidopsis, knocking out two RopGAP (ROP GTPase-activating proteins) that interact with kinesins (POK1/2) resulted in mis-oriented cell division in early embryos and in roots (55). Interestingly, DNrop3 expression induced abnormal cell division in both roots and embryos in Arabidopsis (19). However, it is unknown whether PHGAP1/2 and ROP3 are physically and functionally linked in the spatial regulation of cell division in these cases. Knockdown of RopGEF7 impacted stem cell niche maintenance (58). Therefore, ROP signaling to the spatial regulation of cell division appears to be a common developmental mechanism in plants.

ROP signaling controls many biological processes by interacting with downstream effectors (59). Interestingly, unlike Arabidopsis, M. polymorpha does not have well-known effectors such as RIC proteins (SI Appendix, Table S1), showing that MpROP does not require a CRIB motif to interact with downstream targets like many yeast and animal Cdc42/Rac effectors (60, 61). Genes encoding some other known ROP interactive protein partner homologous genes, such as REN4, TOR, and ABI1/2, exist in the genome of M. polymorpha (SI Appendix, Table S1). We tested the interaction between these effector candidates and MpROP by yeast two-hybrid analysis and found that none of them interacted with MpROP (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 A–C). Therefore, although homologs of MpROP effectors may not have been reported as ROP effectors in any plant species, they may widely exist in plants. The functional study of downstream interactive partners of MpROP may have the potential to provide additional new insights into conserved fundamental functions of ROP GTPase signaling pathways in plant development.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Condition.

M. polymorpha male accession of Takaragaike-1 (Tak1) was used as WT to generate Mprop-1, Mprop-2 CRISPR knockout lines and transgenic lines. M. polymorpha plants were grown on half-strength Gamborg’s B5 medium (Coolaber) containing 1% (wt/vol) sucrose and 1% agar (wt/vol) under 50 to 60 µmol m−2 s−1, 18-h/6-h white light at 22 °C or on vermiculite under white light with far-red light at 22 °C. All the plants grown on vermiculite were covered by plastic films to keep higher humidity, since the Mprop mutant could not grow under low-humidity conditions. A. thaliana Col-0 (ecotype columbia-0) WT transgenic plants were grown at 22 °C in a controlled growth room with 16-h light and 8-h dark. Transgenic plants expressing the mutant gene AtCAROP2, provided by Zhenbiao Yang’s laboratory, were described previously (52).

Generation of Mprop-1 and Mprop-2 Mutants.

Loss-of-function mutants of MpROP were generated with the CRISPR/Cas9 system as described previously (62). CRISPR target sites were predicted on the website (http://crispr.hzau.edu.cn/CRISPR2/), and two target sites on the first (Mprop-2) and third exon (Mprop-1) were selected. Synthetic oligos DNA for Mprop-1 named MpROPcas9.1-F(En_01)/MpROPcas9.1-R(En_01) and for Mprop-2 named Mpropcrispr.6-En01-F/Mpropcrispr.6-En01-R were annealed, inserted in the entry vector pMpGE_En01 (62) with the in-fusion HD cloning kit (Clontech), and then introduced into the destination vector pMpGE010 (62) by using LR clonase II Enzyme mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The reconstructed vectors were introduced into regeneration thalli of WT by Agrobacterium GV3101, and transformants were selected with 10 mg/L hygromycin (Roche). The transgene was confirmed by sequence analysis using genomic DNA. Then the target region was amplified by PCR (Biosune, Fuzhou) to sequence for the respective target sites.

Phenotype Analysis.

Thalli of M. polymorpha were observed using a digital camera (DSC-RX10, Sony). Thalli were observed with a scanning electron microscope (TM3030 PLUS, Hitachi). Gemmae were observed with an upright microscope (SMZ18, Nikon) after being taken out from the gemma cup or grown on B5 medium. To measure the maximum rhizoid length, gemmae were grown vertically on B5 medium for 3 d, and images were taken with an upright microscope (SMZ18, Nikon). The longest rhizoids per gemmaling were measured for each genotype by ImageJ.

Quantitative Analysis of Microtubule Anisotropy and Cell Division Angle.

Two-day-old gemmalings of Tak1 and Mprop-1 mutant were first fixed in PEMT buffer (50 mM 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid [Pipes], pH 6.8, 5 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid [EGTA], 1 mM MgSO4, and 0.05% Triton X-100) with 4% paraformaldehyde after vacuum pump three times for 8 min each. Then the fixed samples were incubated in a cell wall digestion solution (0.2% Driselase and 0.15% Macerozyme in 2 mM MES, pH 5.0) for 60 min at 37 °C started with a vacuum pump for 5 min after being washed in PEMT buffer (without paraformaldehyde) three times for 5 min each. The samples were incubated into permeabilization buffer (1x phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], pH 7.4, with 1% Trition X-100) for 2 h, then blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (PBS buffer) at 4 °C for 3 h. Then, the fixed samples were used for the staining of microtubules, and primary antibody (anti–β-tubulin, mouse, 1:100; Abmart) was incubated at 4 °C overnight started with a vacuum pump for 15 min. After washing five times for 2 min each in 1x PBS solution, the samples were incubated with secondary antibody (anti-Mouse immunoglobulin G–tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate [TRITC], 1:100; Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at room temperature or 4 °C overnight, started with a vacuum pump for 15 min. The samples were mounted on slides with antifade media after being washed with PBS for 2 min five times. Images were taken using a Leica SP8 Laser Scanning Confocal system. ImageJ with FibrilTool plug-in to quantify fibrillar structures was used to analyze the average anisotropy of MT. The anisotropy score “0” indicates no order (isotropic arrays), and “1” indicates perfectly ordered (anisotropic arrays). For quantitative analysis of cell division angle, the angle between the spindle or polar organizer split direction and the line along the edge of the apical notch were analyzed. One or two cell layers along the edge of the apical meristem were selected for analysis.

Subcellular Localization of MpROP.

For observation of MpROP subcellular localization, pENTR-MpROPr1 was amplified by PCR using primer set MpROP-G134-F/MpROP-G134-R to generate linearized pENTR-MpROPr1 (63). Venus was cloned into the linearized pENTR-MpROP r1 vector by using In-Fusion HD Cloning kits (Clontech) to generate the construct of pENTR-MpROP(N)-Venus- MpROP(C). MpROP(N)-Venus-MpROP(C) was introduced into binary constructs pMpGWB303 by using LR clonase II Enzyme mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). pMpGWB303-MpROP(N)-Venus-MpROP(C) (proMpEF1:RVRr1) vector was transformed into regenerating thalli of Mprop-1 mutant mediated by Agrobacterium GV3101, and transformants were selected with 0.5 μM Chlorsulfuron. Two-day-old gemmalings of proMpEF1:RVRr1 transgenic plants were used to check the localization of MpROP. For counterstaining with fn4-64, 2-d-old gemmalings of proMpEF1:RVRr1 transgenic plants were stained with fn4-64 (0.2 μg/μL stock solution, diluted to 1:100; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min. Images were acquired after the application of fn4-64 dye by using a confocal microscope (Leica SP8). The samples were excited with a white light laser (488 nm for Venus, 561 for fn4-64), and the emission was sequentially collected between 499 and 551 nm for Venus and 731 and 736 nm for fn4-64. Quantitative signal intensity was analyzed by ImageJ.

Cell Division Analysis.

To analyze if cell division obeys the shortest-path division rule [a cell is divided by the shortest path that divides the cell into two equally sized daughter cells (37)] in the Marchantia meristem notch outer layer cells, we took fluorescent images of WT and mutant stained/labeled with Calcofluor White. First, we identified cells that were newly divided, with a nascent cell wall dividing each cell into two. As a criterion to distinguish a pair of new daughter cells from two unrelated cells, the former should constitute a convex polygon. Next, we identified the boundary of the mother cell and computed the center of mass. We found the default division plane (the one if cell division followed the shortest-path division rule) by finding the shortest line segment passing through the center of mass and intersecting with the mother cell wall. The actual division plane was defined by the nascent cell wall. The angle between the default and the actual division plane, Δθ, was determined as a measure of how much the actual division direction deviated from the default one.

Generation of MpCAROP Overexpression in Arabidopsis and Pavement Cell Observation.

To create MpCAROP, site-directed mutagenesis was conducted on the basis of pENTR-MpROP. Two oligo nucleotides, MpCAROP-F/MpCAROP-R, containing the desired changes were used based on the amino acid sequence alignment with AtCAROP2. Site mutations were confirmed by sequencing. Q64L mutations are predicted to cause constitutive activation of MpROP, and the entry vector pENTR-MpCAROP was used in Gateway LR reaction with the Gateway binary vector pGWB2 (64) to generate pro35S:MpCAROP. The reconstructed vector was introduced into Col-0. Transgenic plants were selected with 50 mg/L hygromycin (Roche).

For observation of the pavement cell, 3-d-old T3 generation homologous transgenic lines were stained with fn1-43 (0.2 μg/μL stock solution, diluted to 1:100; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min. Images were acquired by epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Ti-E).

Marchantia and Arabidopsis Transformation.

Transgenic M. polymorpha plants were generated by the thallus transformation method with Agrobacterium strain (GV3101) carrying the above binary vectors (7). Transgenic Arabidopsis plants were generated by the floral dipping method with Agrobacterium strain (GV3101) carrying the above binary vectors (65).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Zhenbiao Yang (University of California, Riverside) and Dr. Takayuki Kohchi (Kyoto University) for their careful and critical comments on this manuscript. Arabidopsis AtCAROP2 transgenic line was kindly provided by Zhenbiao Yang’s laboratory. M. polymorpha (Tak-1), the vector series used for this study, and method for stable transformation were kindly provided by Takayuki Kohchi’s laboratory. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant Nos. 31972388 to C.Y. and 32100576 to D.R.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. B.L. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2117803119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Etienne-Manneville S., Hall A., Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature 420, 629–635 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Z., Cell polarity signaling in Arabidopsis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 24, 551–575 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez P., Rincón S. A., Rho GTPases: Regulation of cell polarity and growth in yeasts. Biochem. J. 426, 243–253 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craddock C., Lavagi I., Yang Z., New insights into Rho signaling from plant ROP/Rac GTPases. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 492–501 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao H., Tang R., Zhang X., Luan S., Yu F., FERONIA receptor kinase at the crossroads of hormone signaling and stress responses. Plant Cell Physiol. 58, 1143–1150 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eklund D. M., Svensson E. M., Kost B., Physcomitrella patens: A model to investigate the role of RAC/ROP GTPase signalling in tip growth. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 1917–1937 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubota A., Ishizaki K., Hosaka M., Kohchi T., Efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha using regenerating thalli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 77, 167–172 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishizaki K., Nishihama R., Yamato K. T., Kohchi T., Molecular genetic tools and techniques for Marchantia polymorpha research. Plant Cell Physiol. 57, 262–270 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohchi T., Yamato K. T., Ishizaki K., Yamaoka S., Nishihama R., Development and molecular genetics of Marchantia polymorpha. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 72, 677–702 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowman J. L., et al. , The renaissance and enlightenment of Marchantia as a model system. Plant Cell 34, 3512–3542 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naramoto S., Hata Y., Fujita T., Kyozuka J., The bryophytes Physcomitrium patens and Marchantia polymorpha as model systems for studying evolutionary cell and developmental biology in plants. Plant Cell 34, 228–246 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honkanen S., et al. , The mechanism forming the cell surface of tip-growing rooting cells is conserved among land plants. Curr. Biol. 26, 3238–3244 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu Y., Wu G., Yang Z., Rop GTPase-dependent dynamics of tip-localized F-actin controls tip growth in pollen tubes. J. Cell Biol. 152, 1019–1032 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones M. A., et al. , The Arabidopsis Rop2 GTPase is a positive regulator of both root hair initiation and tip growth. Plant Cell 14, 763–776 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu Y., Gu Y., Zheng Z., Wasteneys G., Yang Z., Arabidopsis interdigitating cell growth requires two antagonistic pathways with opposing action on cell morphogenesis. Cell 120, 687–700 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeon B. W., et al. , The Arabidopsis small G protein ROP2 is activated by light in guard cells and inhibits light-induced stomatal opening. Plant Cell 20, 75–87 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu Y., Xu T., Zhu L., Wen M., Yang Z., A ROP GTPase signaling pathway controls cortical microtubule ordering and cell expansion in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 19, 1827–1832 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagawa S., Xu T., Yang Z., RHO GTPase in plants: Conservation and invention of regulators and effectors. Small GTPases 1, 78–88 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J. B., et al. , ROP3 GTPase contributes to polar auxin transport and auxin responses and is important for embryogenesis and seedling growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 3501–3518 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato H., et al. , The roles of the sole activator-type auxin response factor in pattern formation of Marchantia polymorpha. Plant Cell Physiol. 58, 1642–1651 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yasui Y., et al. , GEMMA CUP-ASSOCIATED MYB1, an ortholog of axillary meristem regulators, is essential in vegetative reproduction in Marchantia polymorpha. Curr. Biol. 29, 3987–3995.e5 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christensen T. M., et al. , Conserved subgroups and developmental regulation in the monocot rop gene family. Plant Physiol. 133, 1791–1808 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fowler J. E., “Evolution of the ROP GTPase signaling module” in Integrated G Proteins Signaling in Plants: Signaling and Communication in Plants, Yalovsky S., Baluška F., Jones A., Eds. (Springer, Berlin, 2010), pp. 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brembu T., Winge P., Bones A. M., The small GTPase AtRAC2/ROP7 is specifically expressed during late stages of xylem differentiation in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 2465–2476 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang W., et al. , The RopGEF2-ROP7/ROP2 pathway activated by phyB suppresses red light-induced stomatal opening. Plant Physiol. 174, 717–731 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones V. A. S., Dolan L., The evolution of root hairs and rhizoids. Ann. Bot. 110, 205–212 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rounds C. M., Bezanilla M., Growth mechanisms in tip-growing plant cells. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 243–265 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin D., et al. , A ROP GTPase-dependent auxin signaling pathway regulates the subcellular distribution of PIN2 in Arabidopsis roots. Curr. Biol. 22, 1319–1325 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nibau C., Tao L., Levasseur K., Wu H. M., Cheung A. Y., The Arabidopsis small GTPase AtRAC7/ROP9 is a modulator of auxin and abscisic acid signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3425–3437 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin D., Ren H., Fu Y., Lin D., ROP GTPase-mediated auxin signaling regulates pavement cell interdigitation in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 57, 31–39 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren H., Lin D., ROP GTPase regulation of auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 8, 193–195 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eklund D. M., et al. , Auxin produced by the indole-3-pyruvic acid pathway regulates development and gemmae dormancy in the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. Plant Cell 27, 1650–1669 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taren N., Factors regulating the initial development of gemmae in Marchantia polymorpha. Bryologist 61, 191–204 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnes C. R., Land W. J. G., The origin of the cupule of Marchantia contributions from the hull botanical laboratory. Bot. Gaz. 46, 401–409 (1908). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kato H., Yasui Y., Ishizaki K., Gemma cup and gemma development in Marchantia polymorpha. New Phytol. 228, 459–465 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimamura M., Marchantia polymorpha: Taxonomy, phylogeny and morphology of a model system. Plant Cell Physiol. 57, 230–256 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahlin P., Jönsson H., A modeling study on how cell division affects properties of epithelial tissues under isotropic growth. PLoS One 5, e11750 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimata Y., et al. , Cytoskeleton dynamics control the first asymmetric cell division in Arabidopsis zygote. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 14157–14162 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaddepalli P., et al. , Auxin-dependent control of cytoskeleton and cell shape regulates division orientation in the Arabidopsis embryo. Curr. Biol. 31, 4946–4955.e4 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hasi Q., Kakimoto T., ROP interactive partners are involved in the control of cell division patterns in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 63, 1130–1139 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boudaoud A., et al. , FibrilTool, an ImageJ plug-in to quantify fibrillar structures in raw microscopy images. Nat. Protoc. 9, 457–463 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang W., et al. , Mechano-transduction via the pectin-FERONIA complex activates ROP6 GTPase signaling in Arabidopsis pavement cell morphogenesis. Curr. Biol. 32, 508–517.e3 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gu Y., et al. , A Rho family GTPase controls actin dynamics and tip growth via two counteracting downstream pathways in pollen tubes. J. Cell Biol. 169, 127–138 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bourne H. R., Sanders D. A., McCormick F., The GTPase superfamily: A conserved switch for diverse cell functions. Nature 348, 125–132 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bourne H. R., Sanders D. A., McCormick F., The GTPase superfamily: Conserved structure and molecular mechanism. Nature 349, 117–127 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berken A., Thomas C., Wittinghofer A., A new family of RhoGEFs activates the Rop molecular switch in plants. Nature 436, 1176–1180 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas C., Fricke I., Scrima A., Berken A., Wittinghofer A., Structural evidence for a common intermediate in small G protein-GEF reactions. Mol. Cell 25, 141–149 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hiwatashi T., et al. , The RopGEF KARAPPO is essential for the initiation of vegetative reproduction in Marchantia polymorpha. Curr. Biol. 29, 3525–3531.e7 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ren H., et al. , SPIKE1 activates ROP GTPase to modulate petal growth and shape. Plant Physiol. 172, 358–371 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamaguchi K., et al. , SWAP70 functions as a Rac/Rop guanine nucleotide-exchange factor in rice. Plant J. 70, 389–397 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamaguchi K., Kawasaki T., Function of Arabidopsis SWAP70 GEF in immune response. Plant Signal. Behav. 7, 465–468 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H., Shen J. J., Zheng Z. L., Lin Y., Yang Z., The Rop GTPase switch controls multiple developmental processes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 126, 670–684 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang R., et al. , Noncanonical auxin signaling regulates cell division pattern during lateral root development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 21285–21290 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Humphries J. A., et al. , ROP GTPases act with the receptor-like protein PAN1 to polarize asymmetric cell division in maize. Plant Cell 23, 2273–2284 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stöckle D., et al. , Putative RopGAPs impact division plane selection and interact with kinesin-12 POK1. Nat. Plants 2, 16120 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Y., Xiong Y., Liu R., Xue H. W., Yang Z., The Rho-family GTPase OsRac1 controls rice grain size and yield by regulating cell division. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 16121–16126 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yi P., Goshima G., Rho of plants GTPases and cytoskeletal elements control nuclear positioning and asymmetric cell D. Curr. Biol. 30, 1–9 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen M., et al. , RopGEF7 regulates PLETHORA-dependent maintenance of the root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23, 2880–2894 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feiguelman G., Fu Y., Yalovsky S., ROP GTPases structure-function and signaling pathways. Plant Physiol. 176, 57–79 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burbelo P. D., Drechsel D., Hall A., A conserved binding motif defines numerous candidate target proteins for both Cdc42 and Rac GTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 29071–29074 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Owen D., Mott H. R., CRIB effector disorder: Exquisite function from chaos. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 46, 1289–1302 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sugano S. S., et al. , Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing and its application to conditional genetic analysis in Marchantia polymorpha. PLoS One 13, e0205117 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheng X., Mwaura B. W., Chang Stauffer S. R., Bezanilla M., A fully functional ROP fluorescent fusion protein reveals roles for this GTPase in subcellular and tissue-level patterning. Plant Cell 32, 3436–3451 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakagawa T., et al. , Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104, 34–41 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clough S. J., Bent A. F., Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.