Abstract

Pore-forming proteins (PFPs) comprise the largest single class of bacterial protein virulence factors and are expressed by many human and animal bacterial pathogens. Cells that are attacked by these virulence factors activate epithelial intrinsic cellular defenses (or INCEDs) to prevent the attendant cellular damage, cellular dysfunction, osmotic lysis, and organismal death. Several conserved PFP INCEDs have been identified using the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and the nematicidal PFP Cry5B, including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways. Here we demonstrate that the gene nck-1, which has homologs from Drosophila to humans and links cell signaling with localized F-actin polymerization, is required for INCED against small-pore PFPs in C. elegans. Reduction/loss of nck-1 function results in C. elegans hypersensitivity to PFP attack, a hallmark of a gene required for INCEDs against PFPs. This requirement for nck-1-mediated INCED functions cell-autonomously in the intestine and is specific to PFPs but not to other tested stresses. Genetic interaction experiments indicate that nck-1-mediated INCED against PFP attack is independent of the major MAPK PFP INCED pathways. Proteomics and cell biological and genetic studies further indicate that nck-1 functions with F-actin cytoskeleton modifying genes like arp2/3, erm-1, and dbn-1 and that nck-1/arp2/3 promote pore repair at the membrane surface and protect against PFP attack independent of p38 MAPK. Consistent with these findings, PFP attack causes significant changes in the amount of actin cytoskeletal proteins and in total amounts of F-actin in the target tissue, the intestine. nck-1 mutant animals appear to have lower F-actin levels than wild-type C. elegans. Studies on nck-1 and other F-actin regulating proteins have uncovered a new and important role of this pathway and the actin cytoskeleton in PFP INCED and protecting an intestinal epithelium in vivo against PFP attack.

Author summary

The mechanism of action for a significant number of bacterial protein toxins is the formation of pores in the membrane of target cells. Host cells contain programmed defenses against such attacks. Here we use the model system of the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans and crystal proteins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis to demonstrate a new defense pathway mediated by the activity of the NCK-1 protein. Consistent with its known function in mammalian cells, the NCK-1-mediated defense involves various actin-interacting proteins and affects the kinetics of pore repair. This pathway is novel in its independence from MAPK signaling. Furthermore, the NCK-1 activity is found to be generally needed for defense against multiple pore-forming proteins and yet is specific to defense against such proteins but not against other environmental stressors.

Introduction

The largest class of bacterial protein virulence factors is pore-forming proteins (PFPs) [1–4]. Produced by many major human pathogens, these are critical virulence factors; many strains that have been deleted for their PFP genes become avirulent or significantly less virulent in lab animals. It is therefore critical to better understand how host cells respond to attack by these toxins. Typically, toxin monomers are secreted or externalized by bacteria, activated by cleavage by host proteases, and oligomerize before being inserted into the plasma membrane and forming pores. PFPs can generally be split into large pore-formers (~30 nm diameter) and small pore-formers (~2 nm diameter). The host range and cellular tropism can be determined by expression of host factors at the membrane that serve as receptors for the toxin. Receptors for different toxins include cholesterol, other lipids, and proteins. Cells that are perforated by toxins are thought to die by osmotic lysis, necrosis, programmed cell death, or dysfunction caused by ion dysregulation. [5].

Cells can mitigate this damage, however, by activating intrinsic cellular defenses or INCED [6–12]. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and exposure to PFPs (e.g., Cry5B PFP; [13]) made by the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis have proven to be an invaluable model for discovering and studying INCED pathways by which cells defend against PFPs. These INCEDs include activation and up-regulation of p38 and JNK-like mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways [13,14], the unfolded protein response [9], the hypoxia response [6], endocytosis and membrane shedding [15], and autophagy [7]. Investigation in animal cell culture systems has shown that all of these PFP INCED response processes discovered and/or described in C. elegans are evolutionarily conserved [9,13,14,16].

We previously reported on a C. elegans genome-wide RNAi screen for genes required for INCED against PFPs, in which >16,000 RNAi knock-downs were performed followed by selection and repeat testing at a single dose of Cry5B PFP [13]. This screen yielded 106 hpo genes (hypersensitive to pore-forming toxin). One of the conserved hits included nck-1, the C. elegans homolog of mammalian Nck that is involved in linking tyrosine phosphorylation with localized F-actin polymerization by recruiting several effectors to the plasma membrane, including N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex [17]. nck-1 is known to be involved in C. elegans axonal guidance, excretory cell and distal tip cell migration, male mating, vulval development, dauer formation, and susceptibility to Orsay virus [18–22]. Here we study the role of nck-1 in PFP INCED, uncovering a key, important, and previously unknown role in vivo between PFP INCED, nck-1 and other F-actin modulating genes, and the filamentous (F-) actin cytoskeleton.

Results

To follow up on the genome-wide RNAi screen for PFP INCED genes [13], we selected a few hpo genes for dose-dependent Cry5B PFP response assays using RNAi and also looked at the corresponding response of available genetic mutants associated with these hpo genes. From these preliminary follow up studies, the hpo gene nck-1 emerged as a gene of interest. Wild-type N2 C. elegans larvae grown on E. coli expressing RNAi sequences directed against nck-1 were subjected to dose-response mortality assays using purified Cry5B (Fig 1A). nck-1(RNAi) C. elegans hermaphrodites were hypersensitive to Cry5B relative to empty-vector(RNAi) C. elegans hermaphrodites over a wide range of Cry5B PFP concentrations. In these and other experiments below, RNAi of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MAPKK) sek-1, knockdown of which is known to give a high level of hypersensitivity to Cry5B PFP [14,15], was included as a positive control. These experiments confirm nck-1 is required for normal PFP INCED over a wide range of PFP doses.

Fig 1. nck-1 loss sensitizes C. elegans to Cry5B.

(A) Wild-type N2, (B) glp-4(bn2); rrf-3(pk1426), or (D) VP303 (intestine-specific RNAi) C. elegans were grown from the L1 to L4 stage on E. coli expressing the indicated RNAi, then transferred to liquid culture with purified Cry5B for 6 days, then assayed for survival. (C) Wild-type N2 or nck-1(ok694) null L4s were grown on OP50 E. coli until the L4 stage before being subjected to the same experiment. All data show the mean of three experiments. Error bars here and in other figures represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). Each data point is the average of three independent experiments with three wells/experiment (n = 25–34 worms/well).

These experiments have a time course of 6 days, and the presence of progeny born during that time can obscure the results, so the thymidine analog 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine (FUdR) was included in the media in Fig 1A to prevent progeny production. To ensure that the presence of FUdR itself did not contribute to the Cry5B hypersensitivity of nck-1-deficient worms, the experiment was repeated using the glp-4(bn2); rrf-3(pk1426) strain, which is hypersensitive to RNAi (due to the rrf-3 mutation) as well as sterile at the assay temperature of 25°C (due to the glp-4 mutation), obviating the need for FUdR. In this background, knockdown of nck-1 also led to hypersensitivity to Cry5B as measured by mortality (Fig 1B). The outcrossed null mutant nck-1(ok694) was viable and fertile, but larvae that were synchronized by standard hypochlorite treatment nevertheless developed at variable speeds. Therefore, L4 larvae were visually identified and handpicked for experiments using the mutant strain. As with wild-type worms knocked down for nck-1 by RNAi, nck-1(ok694) mutants were also hypersensitive to Cry5B compared to wild-type worms, and the effect was more penetrant than in the RNAi experiment (Fig 1C). Because the intestinal epithelium is the tissue directly targeted by the PFP Cry5B [23–25], we also tested whether nck-1 activity is required in the intestinal epithelium itself. Knockdown of nck-1 in the VP303 strain—which preferentially carries out RNAi in the intestine—also led to hypersensitivity to Cry5B (Fig 1D), indicating that nck-1 is required for a cell-autonomous defense process for protection against PFPs.

The p38 MAPK pathway, for which sek-1 is the MAPKK, is clearly a central player in cellular defenses against PFPs [5,13,26]. We next tested whether or not nck-1’s role in PFP defenses was part of the p38 MAPK PFP defense pathway. First, we examined the MAPK-dependent activation of the xbp-1-dependent arm of the unfolded protein response (UPR) in response to Cry5B PFP. The hsp-4::gfp worm strain carries a GFP reporter for this response, increasing its fluorescence in response to classic UPR inducers such as tunicamycin or heat shock, but also after worms are fed Cry5B-expressing E. coli for 8 hours [9]. The latter, PFP-induced UPR response is known to be dependent upon MAPK signaling, as it was previously shown to be blocked in animals that carry a secondary mutation in pmk-1, which encodes the C. elegans p38 homolog that is a direct target of SEK-1 kinase activity. Here we similarly found that hsp-4::gfp worms that lacked MAPK signaling due to knockdown of sek-1 showed no increase in GFP signal in response to an 8-hour E. coli-Cry5B feeding exposure (Fig 2A). In contrast, the knockdown of nck-1 did not block Cry5B-induced activation of the UPR. Worms knocked down for sek-1 or nck-1 still showed increased GFP signaling following an 8-hour 30°C heat shock exposure, demonstrating that the hsp-4::gfp response was still intact in those worms (S1 Fig). As a control, worms with a knockdown for xbp-1 showed a loss of even basal levels of reporter activity in response to either stressor (Figs 2A and S1). These results suggested a distinction between a sek-1-mediated and nck-1-mediated PFP response.

Fig 2. nck-1 works independently of MAPK signaling.

(A) hsp-4::gfp C. elegans were grown to the L4 stage on the indicated RNAi bacteria and transferred to E. coli plates expressing empty vector or Cry5B for 8 hours, then subjected to fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar = 0.1mm. (B) sek-1(km4) p38 MAPKK(-) mutant C. elegans were grown on the indicated RNAi bacteria to the L4 stage and then transferred to liquid culture with varying amounts of purified Cry5B and incubated for 6 days before being scored for survival. pmk-1 is p38 MAPK. (C) The reverse experiment to the one in (B), with nck-1(ok694) mutant animals and RNAi of MAPK pathway genes at a single concentration of Cry5B. For (B) and (C), each data point is the average of three independent experiments with three wells/experiment (n = 20–33 worms/well).

We therefore next directly tested for a genetic interaction between MAPK signaling and nck-1 in toxin defense. sek-1(km4) p38 MAPKK mutant hermaphrodites were subjected to additional knock down of either nck-1 or pmk-1. As expected, pmk-1 knockdown did not increase the PFP sensitivity of hermaphrodites that were already null for the upstream activator sek-1 (Fig 2B). In contrast, nck-1 knockdown did further sensitize sek-1(km4) null hermaphrodites to Cry5B. We also performed this experiment in reverse, knocking down either sek-1 or kgb-1 in nck-1(ok694) null mutants. The kgb-1 gene encodes a JNK-like MAPK that has also been critically implicated in PFP defense in C. elegans [13,14]. Knockdown of either MAPK pathway further sensitized nck-1(ok694) worms to Cry5B (Fig 2C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that nck-1 functions independently of the p38 and JNK-like MAPK signaling pathways for Cry5B PFP defense.

We next characterized the specificity of the nck-1-mediated PFP response. Namely, is the hypersensitivity of nck-1 reduction/loss-of-function to Cry5B PFP due to a specific defect in Cry5B PFP responses or to a more generalized inability to protect against even non-PFP stressors that attack the health of the nematode? We therefore next tested the ability of nck-1-deficient animals to withstand other types of stress. Worms that experienced nck-1 RNAi in the intestine alone (the VP303 strain) showed no change in their sensitivity to a prolonged 35°C heat stress (Fig 3A). The intestinal knockdown of nck-1 also did not sensitize worms to the heavy metal copper sulfate (Fig 3B). Global knockdown of nck-1 in N2 did not lead to a change in sensitivity to osmotic stress (Fig 3C) or oxidative stress either (Fig 3D), as assayed by exposure to increasing concentrations of NaCl or H2O2, respectively. Since the tested stresses mentioned to this point are all environmental rather than pathogenic, we also tested the requirement for nck-1 in defense against the pathogenic food source Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA14), which produces several toxic factors but is not known to produce a PFP. Knockdown of nck-1 did not sensitize the worms to PA14 (Fig 3E). Consistent with previous reports [27], sek-1 knockdown did sensitize worms to PA14 feeding. In all specificity experiments, some empty vector-treated and nck-1(RNAi) worms were tested in parallel to confirm that the RNAi was effective (i.e., that the nck-1(RNAi) worms were hypersensitive to feeding on E. coli expressing Cry5B). Taken together, the results suggest that, whereas some pathways, e.g., p38 MAPK signaling, are known to be utilized as a defense against PFPs as well as other stresses [27–29], the use of nck-1 to protect cells from PFPs appears to be more narrow.

Fig 3. nck-1 loss does not affect sensitivity to other stressors.

(A) VP303 (intestinal-specific RNAi) C. elegans L4 animals grown on RNAi bacteria were incubated at 35°C, with survival determined at each indicated time-point. (B) VP303 L4 animals grown on the indicated RNAi bacteria were transferred to liquid culture with varying amounts of CuSO4 for 6 days at 25°C. (C and D) Wild-type N2 C. elegans grown to the L4 stage on the indicated RNAi were transferred to liquid culture with varying amounts of (C) NaCl for 6 days or (D) H2O2 for 4 hours, before survival was measured. (E) Wild-type C. elegans grown to the L4 stage on the indicated RNAi were transferred to plates spread with Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 and survival was followed over the indicated time. For (A), each data point is the average of three independent experiments with one plate/experiment (n = 40–50 worms/plate). For (B), (C), and (D), each data point is the average of three independent experiments with three wells/experiment (n = 27–29 worms/well). The data in (E) are a single representative of three independent trials with comparable results (n = 90 animals/genotype). Logrank analysis shows no significant difference in survival between empty vector and nck-1(RNAi) animals.

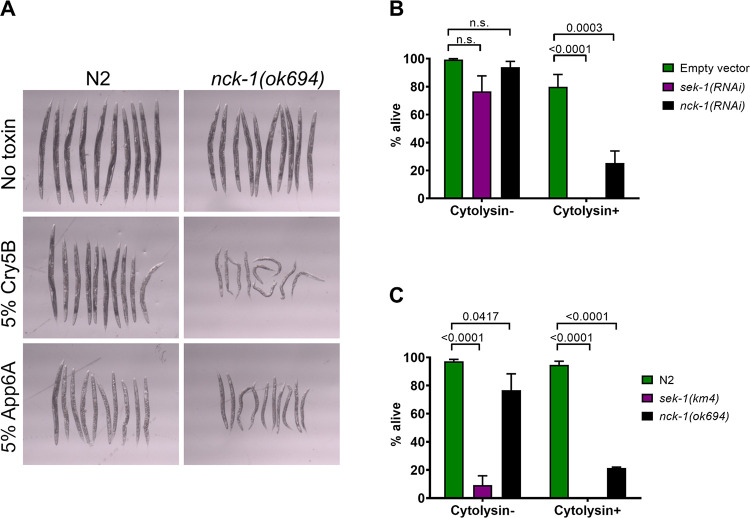

We then investigated whether or not nck-1 protects C. elegans against PFPs other than Cry5B. For this, we tested the requirement for nck-1 in defense against another member of the Bacillus thuringiensis crystal protein family of PFPs, App6A (formerly called Cry6A; [30]). Although Cry5B and App6A are both B. thuringiensis proteins that form pores, the two PFPs are structurally distinct and use different receptors, and C. elegans mutants that are resistant to Cry5B remain sensitive to App6A [13,31–35]. Hence, App6A represents an independent PFP for testing with nck-1 animals. We found that nck-1(ok694) null mutants were visually hypersensitive to feeding on E. coli expressing recombinant App6A, compared to wild-type worms (Fig 4A).

Fig 4. nck-1 loss sensitizes C. elegans to multiple PFPs.

(A) Wild-type N2 or nck-1(ok694) null C. elegans L4s were transferred to plates spread with the indicated percentage of E. coli expressing Cry5B or App6A (formerly Cry6A). Plates were incubated two days at 20°C and then worms were transferred to spot wells and photographed. (B) Wild-type N2 C. elegans grown to the L4 stage on the indicated RNAi bacteria were transferred to plates spread with Vibrio cholerae that do or do not express the PFP cytolysin, and survival was measured after 48 hours. (C) The same experiment as in (B) but using wild-type N2 or mutant C. elegans L4 animals. The data in (A) are representative of three independent trials. For (B) and (C), each data point is the average of three independent experiments with one plate/experiment (n = 50 worms/plate).

We also tested the sensitivity of C. elegans to Vibrio cholerae cytolysin, a PFP that is active against both mammalian cells and C. elegans [6,36]. C. elegans with an nck-1 deficiency due to either RNAi knockdown (Fig 4B) or genetic mutation (Fig 4C) were much more sensitive to feeding on a cytolysin-positive strain of V. cholerae compared to wild-type worms. C. elegans with a sek-1 deficiency were also much more sensitive to feeding on a cytolysin-positive strain of V. cholerae compared to wild-type worms (Fig 4B). The increased sensitivity of nck-1-deficient animals compared to wild-type animals was not retained when fed V. cholerae lacking cytolysin, although sek-1(km4) null animals (but not sek-1(RNAi) reduction of function animals) were also hypersensitive to the cytolysin-minus strain of V. cholerae, consistent with the fact that sek-1 is more generally involved in stress responses and that V. cholerae may produce other non-PFP virulence factors against C. elegans [37]. Taken together, these data demonstrate that nck-1 shows specificity for defense against multiple PFPs but not the other environmental or pathogenic factors tested.

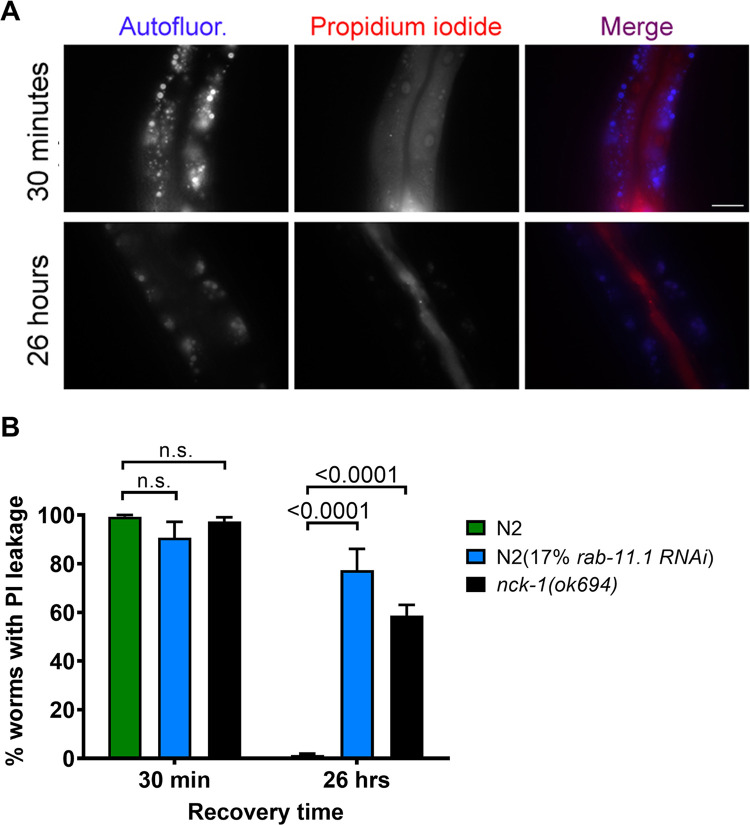

C. elegans intestinal cells that have pores inserted into their apical surface take steps to repair the integrity of the perforated membrane [15]. When worms are given an acute exposure to Cry5B PFP and then immediately fed the fluorescent dye propidium iodide, the ingested dye leaks from the intestinal lumen into the cytoplasm of the intestinal epithelial cells (Fig 5A; top panels). If, however, Cry5B PFP feeding and subsequent propidium iodide dye loading are separated by a ~24-hr recovery period, the ingested dye is confined to the intestinal lumen, as the pores are repaired in the interim (Fig 5A; lower panels) [15]. Loss of RAB-11.1 activity due to partial RNAi knockdown weakens the cell’s ability to repair pores [15]. We asked whether or not NCK-1 was also involved in cellular pore repair. We found that whereas wild-type worms showed almost 100% repair during the ~24-hr recovery period, nck-1(ok694) animals failed to repair dye-permeable pores, similar to rab-11.1 control knockdowns (Fig 5B). Importantly, the nck-1(ok694) mutant did not exhibit an endogenous intestinal permeability to propidium iodide in the absence of PFP exposure (S2 Fig).

Fig 5. nck-1 loss affects the ability of cells to repair PFP pores.

(A) Wild-type C. elegans were grown to the L4 stage on the indicated RNAi bacteria and transferred to Cry5B plates for 1 hour. C. elegans were then either fed propidium iodide within 30 minutes or allowed to recover for 26 hours and then fed propidium iodide. Dye-loaded worms were imaged on slides. Autofluorescent gut granules serve as a surrogate marker indicating the position of the intestinal epithelial cells. Scale bar = 25um. (B) Quantitation of the same type of experiment as in (A) except the strains used were nck-1(ok694) null mutants (grown on standard OP50 E. coli) and N2 (grown on either OP50 or rab-11.1 RNAi E. coli as indicated). “PI leakage” = animals with dye found in intestinal cell cytoplasm. The data represent the mean and SEM of three independent experiments with 50 worms/experiment.

Following our finding that nck-1 was required for efficient pore repair, we considered how it might function. In mammalian cells, the NCK-1 homolog Nck is an SH2/SH3 adaptor protein that recruits a large number of effector proteins to the plasma membrane following its own recruitment to phosphorylated tyrosine residues. In particular, Nck has been shown to be a potent activator of actin assembly, in part by effectively activating Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Protein (WASP)-family proteins so that they in turn activate the Arp2/3 complex, which initiates branched actin filament polymerization. The genome-wide RNAi and toxin hypersensitivity screen that identified nck-1 as a C. elegans PFP defense gene also identified WASP-interacting protein wip-1 as well as three subunits of the C. elegans Arp2/3 complex—arx-3, arx-5, and arx-7—as hpo (PFP defense) genes [13]. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that the nck-1-mediated response to PFPs might also function via the Arp2/3 complex.

We confirmed that Arp2/3 subunits are involved in PFP defense. Feeding of undiluted RNAi bacteria against arx-3 or arx-5 led to a significant growth defect in wild-type C. elegans, so the RNAi bacteria were diluted 1:1 with bacteria carrying an empty vector. The level of knockdown afforded by this (50%) dilution was sufficient to qualitatively sensitize worms to Cry5B (Fig 6A). One Arp2/3-encoding gene, arx-5, was chosen for further experimentation. Wild-type worms knocked down for arx-5 also show impaired pore repair (Fig 6B), a phenotype shared with nck-1 mutants. We then looked for genetic interactions between arx-5 and nck-1. Knockdown of arx-5 in the nck-1(ok694) null background did not increase or decrease the sensitivity of the worms to Cry5B, whereas knockdown of sek-1 in the nck-1(ok694) null background displayed increased sensitivity (Fig 6C; just as in the experiment in Fig 2C). Taken together, these results indicate that nck-1 works in the same PFP defense pathway as arx-5—and presumably the rest of the Arp2/3 complex—but separately from the sek-1 MAPK pathway, consistent with the relationship between Nck and Arp2/3 derived from mammalian studies.

Fig 6. nck-1genetically is in the same pathway with the Arp2/3 complex in PFP defense.

(A) N2 worms grown on the indicated RNAi bacteria to the L4 stage and then photographed after two days of feeding on the indicated amount of E. coli-expressed Cry5B. (B) A pore repair assay identical to the one in Fig 5B, but with N2 worms knocked down for sek-1 or arx-5. (C) Survival of nck-1(ok694) worms fed the indicated RNAi bacteria to the L4 stage and then incubated in liquid culture with purified Cry5B for 6 days. The data in Fig 6B represent the mean and SEM of five independent trials (n = 50 worms per trial), while Fig 6C includes data from three independent trials (n = 11 worms/well and three wells/trial).

In order to identify additional proteins and processes required for defense against PFPs, we undertook a proteomic approach. Other groups have previously reported transcriptomic and/or proteomic changes in C. elegans exposed to Bacillus thuringiensis and have mentioned cytoskeletal proteins among the results list [38,39]. We chose a more targeted approach to finding changes directly attributable to Cry5B PFP exposure. glp-4(bn2) animals were grown at 25°C to block gonad development and thus remove a significant amount of non-intestinal tissue so that a greater percent of the protein analyzed was derived from the intestine (glp-4(bn2) animals have a normal response to Cry5B [14]). L4s were then exposed for 8 hours to E. coli either carrying an empty vector or expressing Cry5B. Worms were then processed for proteomic analysis. The list of hits was narrowed down to ones with a significant p-value (p < 0.05), spectral counts > 2, and at least a 2-fold change up or down in expression in Cry5B-exposed worms relative to worms fed with empty vector bacteria. The resulting 386 proteins with increased abundance and 108 proteins with decreased abundance were then analyzed using the PANTHER classification system [40,41]. Analysis of the proteins increased in abundance in the context of Protein Class gave “hydrolase” as the largest category (47 hits). The second largest category was “cytoskeletal protein” (29 hits), and its largest subcategory was “actin family cytoskeletal protein” (21 hits), including 4 subunits of the Arp2/3 complex (ARX1, ARX2, ARX5, ARX7) (Table 1). Furthermore, the largest Molecular Function category in an overrepresentation test of all upregulated proteins was “actin binding” (p = 4.22E-10), with 13 of 55 reference genes represented. This list was mostly a subset of the “actin family cytoskeletal protein” Protein Class and again included the Arp2/3 subunits ARX5 and ARX7. Other noteworthy proteins increased in abundance included components of MAPK signaling, including MEK2, KGB1, and PMK3. Among the proteins with reduced abundance, only one was associated with the Molecular Function term “actin binding”: TWF2, a homolog of the actin-binding protein twinfilin. NCK1 itself was not identified in the proteomic screen. Note, in our proteomic study (8 hr incubation) and previously published proteomic studies above (12 hr incubation) the extended length of the incubations could have resulted in some animals reaching molting, which could add an additional variable in these experiments.

Table 1. Actin-related C. elegans glp-4(bn2) proteins altered by Cry5B feeding as detected by proteomics.

| Increased in abundance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actin-binding (GO:0003779) or actin family cytoskeletal protein (PC00041) | |||||

| act-5 | WBGene00000067 | T25C8.2 | gsnl-1 | WBGene00010593 | K06A4.3 |

| alp-1 | WBGene00001132 | T11B7.4 | mlc-1 | WBGene00003369 | C36E6.3 |

| arx-1 | WBGene00000199 | Y71F9AL.16 | pat-6 | WBGene00003932 | T21D12.4 |

| arx-2 | WBGene00000200 | K07C5.1 | pfn-1 | WBGene00003989 | Y18D10A.20 |

| arx-5 | WBGene00000203 | Y37D8A.1 | plst-1 | WBGene00022425 | Y104H12BR.1 |

| arx-7 | WBGene00000205 | M01B12.3 | pqn-22 | WBGene00004112 | C46G7.4 |

| clik-1 | WBGene00020808 | T25F10.6 | tni-3 | WBGene00006585 | T20B3.2 |

| cpn-1 | WBGene00000777 | F43G9.9 | tth-1 | WBGene00006649 | F08F1.8 |

| dbn-1 | WBGene00010664 | K08E3.4 | unc-22 | WBGene00006759 | ZK617.1 |

| eps-8 | WBGene00001330 | Y57G11C.24 | unc-94 | WBGene00006823 | C06A5.7 |

| erm-1 | WBGene00001333 | C01G8.5 | ZK1321.4 | WBGene00014262 | ZK1321.4 |

| F42C5.9 | WBGene00018349 | F42C5.9 | zyx-1 | WBGene00006999 | F42G4.3 |

| Decreased in abundance | |||||

| Actin-binding (GO:0003779) | |||||

| twf-2 | WBGene00018187 | F38E9.5 | |||

The proteomics results nonetheless lent further strength to the hypothesis that actin regulation plays a role in the cellular response to attack by Cry5B. We tested a few of the genes found in the proteomics screen by RNAi knockdown or with mutant strains to see if they sensitized worms to Cry5B. We found that partial knockdown of erm-1 (Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin-like, involved in linking cortical F-actin to the plasma membrane; [42]) in N2 animals sensitized them to Cry5B feeding (Fig 7A). We obtained the mutant strain dbn-1(ok925) (Drebrin-like, an F-actin-binding protein that changes the helical pitch of actin filaments and decreases rate of F-actin depolymerization; [43]), outcrossed it four times, and subjected it to our standard Cry5B LC50 experiment. Consistent with the fact that DBN1 levels were increased in the Cry5B-treated worms in the proteomics experiment, the null mutant strain was hypersensitive to Cry5B relative to N2 (Fig 7B). We also tested for genetic interaction between erm-1 and either nck-1-mediated or sek-1-mediated PFP responses. sek-1(km4) animals treated with nck-1 RNAi did significantly shift the IC50 (Fig 7C), in accordance with the earlier genetic interaction data (Fig 2B). As with nck-1 RNAi, sek-1(km4) animals treated with 50% erm-1 RNAi also showed a significant hypersensitization to Cry5B based on IC50. These genetic data implicate additional actin-interacting proteins, namely Arp2/3, erm-1 (Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin), and likely dbn-1 (Drebrin), in the mechanism of an nck-1-mediated response to pore-forming proteins that is independent of the p38 MAPK pathway.

Fig 7. nck-1 genetically functions in the same pathway as other F-actin-interacting proteins in PFP defense.

(A) Wild-type N2 C. elegans were grown from the L1 to L4 stage on E. coli expressing the indicated RNAi, then transferred to liquid culture with purified Cry5B for 6 days and assayed for survival. (B) N2 or mutant worms were grown on OP50 E. coli to the L4 stage, then transferred to liquid culture with purified Cry5B for 6 days and assayed for survival. (C) sek-1(km4) mutant C. elegans were grown on the indicated RNAi bacteria to the L4 stage and then transferred to liquid culture with varying amounts of purified Cry5B, incubated for 6 days, and scored for survival. For (A), (B), and (C), each data point is the average of three independent experiments with three wells/experiment (n = 26–40 worms/well).

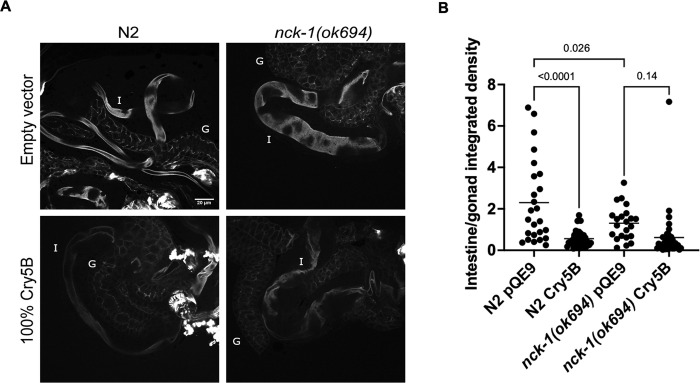

To support the conclusion that the actin cytoskeleton plays an important role in PFP defenses, we examined whether changes in F-actin abundance occurred in C. elegans intestinal tissue upon exposure to Cry5B PFP. We therefore exposed N2 and nck-1(ok694) mutant worms to E. coli-expressed Cry5B or empty vector for 2 hours, then transferred the worms to slides, externalized the intestines, and then stained with FITC-phalloidin to visualize F-actin in the exposed internal tissues. The worms were then analyzed on a confocal scope and images were taken of the stained intestines (Fig 8A). There was a qualitative visual decrease in actin staining at the apical surface in wild-type N2 following Cry5B PFP exposure, and in nck-1(ok694) animals relative to wild-type animals in the absence of Cry5B PFP (no toxin) (Fig 8A).

Fig 8. Cry5B exposure causes a reduction in intestinal F-actin levels.

(A) Wild-type N2 or nck-1(ok694) C. elegans L4 animals were fed E. coli-expressed Cry5B or empty vector for 2 hours, permeabilized, and then their internal organs were fixed and stained with FITC-phalloidin. The honeycombed staining is the gonad (labeled G in the upper panels) and the smoother staining is the intestine (I). (B) The integrated density from images (mean pixel intensity x area) of the intestine divided by that of the gonad following the two-hour toxin incubation was graphed. Each dot represents one worm. The data come from three experiments (n = 10 animals per condition and per genotype per trial), and the bars show the mean. Statistical analyses are as described in the Methods.

To analyze further, we quantitated the intensity of F-actin staining in three independent experiments under these four conditions: wild-type animals not exposed/exposed to Cry5B PFP and nck-1(ok694) animals not exposed/exposed to Cry5B PFP (Fig 8B; see Materials and Methods for details). In order to compare between experiments, we normalized F-actin staining in the intestine to that of the gonad, a tissue that plays no apparent role in Cry5B PFP response [14]. We found that wild-type animals had significantly decreased F-actin upon exposure to Cry5B PFP (Fig 8B). Furthermore, relative to F-actin in the gonad, nck-1(ok694) animals had significantly decreased intestinal F-actin than wild-type animals (Fig 8B; nck-1 itself is expressed in both the intestine and gonad [18]). Conversely, there was not a significant decrease in F-actin in nck-1(ok694) animals upon exposure to Cry5B PFP (Fig 8B), presumably because F-actin levels were already low in nck-1 mutant animals. Taken together, these data indicate that a consequence of intestinal exposure to PFPs in wild-type animals is a reduction in F-actin levels and are consistent with relative stabilization of F-actin in the wild-type intestine by NCK-1.

Discussion

Here we describe one of the most compelling associations between genes involved in regulating filamentous (F-)actin and in vivo intrinsic cellular defenses (INCED) against pore-forming proteins. We find that nck-1, a gene known to play a central role in regulated F-actin assembly in cells in response to cell signaling, protects C. elegans against small-pore PFPs, genetically functioning in the same pathway as a number of key regulators of F-actin including C. elegans Arp2/3 complex (arx-5), Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin (erm-1), and Drebrin (dbn-1). This role in the nck-1 pathway protecting against small PFP attack is applicable to at least three unrelated PFPs (Cry5B, App6A, VCC) and highly specific in that loss of nck-1 does not result in increased sensitivity to heat stress, heavy metal stress, high salt, oxidative stress, or pathogenic P. aeruginosa bacterial attack. At least part of the role of nck-1/arx-5 in PFP INCED involves enhancing the ability of C. elegans intestinal cell apical membrane to repair the small pores formed by Cry5B.

Specific events that could be tied to F-actin-mediated protection against PFP attack include regulation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis or membrane trafficking (e.g., in C. elegans; [15,44]), direct interaction between PFPs and actin [45,46], or generation/maintenance of epithelial junction integrity [47,48].

These results are in contrast to those of the p38 and JNK-like MAPK signaling pathways that are required in C. elegans for defense against pathogenic P. aeruginosa [27], oxidative stress [28], heat stress [29], and heavy metal stress [14]. This positions nck-1 as part of a much more specific response to PFPs than any previously characterized.

Consistent with differences in protection against various stressors, nck-1 and p38 and JNK-like MAPK pathways appear to function differently in PFP defense. Microarrays of C. elegans exposed to Cry5B led to the discovery of p38 and JNK-like MAPK signaling as critical mediators of PFP defense, as C. elegans that are deficient in either signaling pathway are quite sensitive to small amounts of toxin [13,14]. Indeed, the majority, but not all, of the genes that were upregulated in response to Cry5B exposure became so in a MAPK-dependent manner [13]. Our results here from hsp-4::gfp staining and double mutant analyses indicate that nck-1/arx-5/erm-1 function separately from the p38 MAPK signaling pathway in PFP INCED. This is the first instance of a major PFP INCED pathway in C. elegans functioning independently of a MAPK pathway.

Changes in the actin cytoskeleton by PFPs have been seen in a few instances before, although in general it was not known whether the actin changes are initiated as a means of promoting or resisting pathogenesis [49–51]. An exception was Vega-Cabrera et al. where RNAi of actin led to increased PFP toxicity [46]. Recently, studies on changes in actin remodeling and the role of actin cytoskeleton during plasma membrane damage repair have been reviewed [16]. Interestingly, compounds that stabilize F-actin, like jasplakinolide and phalloidin, were found to hinder the recovery of plasma membrane recovery upon mechanical, laser, or PFP-induced damage. Conversely, F-actin depolymerizing drugs like cytochalasin D and latrunculin increased the speed of repair. There are several important differences between these studies and ours. First, these studies look at repair from membrane damage much larger than that caused by the small-pore PFPs, including by large pore-forming PFPs [5] or by mechanical injury or laser injury. It is possible that defense and repair from smaller pores differs significantly from those caused by much larger plasma membrane disruptions. Second, our study is carried out in vivo in an intact epithelium whereas these studies were carried out in vitro. In the case of bacterial virulence, this is the actual context in which a PFP attack would occur. Third, it is possible that what is most important is actin dynamics and less so the total amount of F- vs G-actin.

Our data for the first time indicate that an NCK-1—ARP2/3—ERM F-actin-regulating pathway is important in PFP INCED in C. elegans and, based on the wide range of small-pore PFPs protected against by nck-1, likely in other cells as well. Our results support a model in which small-pore PFPs at the C. elegans apical intestinal membrane destabilize F-actin, which is counteracted by the activity of NCK-1—ARP2/3—ERM, leading to repair of the pores and perhaps other actin-associated INCED processes. Future studies will be directed at determining what other effectors are involved in nck-1-mediated PFP defenses and characterizing more precisely how actin dynamics may be involved in INCED against pore-forming proteins.

Materials and methods

C. elegans and bacterial strains

C. elegans N2 Bristol was maintained using standard techniques [52]. The following strains were used in this study and were purchased from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center: glp-4(bn2), glp-4(bn2); rrf-3(pk1426), nck-1(ok694) following 4X outcross with lon-2(e678), dbn-1(ok925) following 4X outcross with unc-64(e246), VP303 rde-1(ne219);KbIs7[nhx-2P::rde-1] [53], sek-1(km4), and SJ4005 zcIs4[hsp-4::GFP]. E. coli empty-vector control and Cry5B-expressing strains were JM103-pQE9 and JM103-Cry5B. The App6A gene was subcloned into the BamHI and PstI sites of the vector pQE9 (adding an N-terminal His tag and a seven amino acid extension to the C-terminus) and transformed into JM103 [54]. Feeding RNAi bacterial strains were Escherichia coli HT115 with pL4440 vector derived from the Ahringer RNAi library [55] except for rab-11.1 [15]. RNAi clones were confirmed by plasmid DNA sequencing. In all experiments where arx-5, dbn-1, or erm-1 RNAi bacteria were used, a mixture of equal parts HT115 carrying empty pL4440 and or pL4440 bearing the gene-specific RNAi sequence was prepared. In all experiments where rab-11.1 RNAi bacteria was used, a 17% rab-11.1 mixture was prepared in a similar way. E. coli OP50, Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 [56], and Vibrio cholerae strains CVD109 Δ(ctxAB zot ace) and CVD110 Δ(ctxAB zot ace) hlyA::(ctxB mer) Hgr were used [57].

Microscopy and image editing

Images from qualitative toxicity assays were obtained from assay plates, using an Olympus SZ60 dissecting microscope linked to a Canon Powershot A620 digital camera, and using Canon Remote Capture software or from slides with an Olympus BX60 compound microscope with an UplanFl 10x/0.25NA or 40x/1.35NA objective, mounted to a Spot Insight CCD camera and using Spot software. Actin staining images were taken on a Leica TCS SP8 Spectral Confocal DMi8 Inverted Stage Microscope, with LAS X software. All images within an experiment were taken with identical camera settings. Final images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop and/or GIMP.

Quantitative Cry5B assays in liquid media

Assays for determining LC50 of C. elegans exposed to purified Cry5B were performed as described [58] with any changes described below. Unless otherwise indicated, all assays were scored after 6 days and included 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine (FUdR; SIGMA) to prevent the appearance of the next generation of larvae that would complicate the experiments [58]. For experiments in which genes were knocked down by feeding RNAi, L1 larvae were synchronized by hypochlorite treatment and plated onto ENG-IA agar plates spread with RNAi bacteria. Animals were grown at 20°C to the L4/young adult stage. OP50 bacteria in the wells were substituted with overnight cultures of RNAi bacteria that were induced with 1 mM IPTG for 1 hr at 37°C before inclusion in wells. Some L1s were plated in parallel on act-5 or unc-22 RNAi to verify RNAi effect. In the assays for Fig 1B, no FUdR was present, and animals were grown to the L4 stage at 25°C. In assays involving nck-1(ok694) mutants, L4 worms were manually transferred into wells. In the assays for Fig 3B and 3C, CuSO4 (SIGMA) or NaCl (SIGMA), respectively, were substituted for Cry5B [15]. In the assays for Fig 3D, L4 animals were put into wells with only S Media and the indicated concentration of H2O2 for four hours at 20°C before scoring. In the assays for Fig 3B, 3C and 3D, a parallel qualitative agar plate assay was performed (described below).

Heat stress assay

VP303 C. elegans were synchronized by hypochlorite treatment and grown from the L1 stage on ENG-IA agar plates spread with RNAi bacteria. Some L4 animals were used for a qualitative plate assay (described below). One-day adults were transferred to fresh RNAi plates and placed in a 35°C incubator. At the indicated time-points, plates were removed from the incubator, dead worms (unresponsive to touch by an eyelash pick) were removed from the plate, and the plates were replaced in the incubator.

C. elegans survival assays

PA14 slow-killing assays were performed as described [59], except SK plates seeded with PA14 were incubated overnight at 25C. N2 C. elegans were synchronized by hypochlorite treatment and grown from the L1 stage on ENG-IA agar plates spread with RNAi bacteria. Worms were moved to new SK plates at each timepoint.

Some L4 animals were used for a qualitative plate assay (described below). In the Vibrio cholerae assays, CVD109 and CVD110 were inoculated into LB and grown overnight at 30°C. Cultures were then diluted to OD 2.00 and 30 μl were spread on 60mm NG plates and the plates incubated at 25°C overnight. Fifty L4 animals (grown on RNAi bacteria for Fig 4B or OP50 bacteria for Fig 4C) were transferred to each plate and kept at 25°C. Dead worms were removed at 24 hours and remaining live worms moved to a new set of plates. Final survival counts were taken at 48 hours and those results graphed. Some L4 animals were used for a qualitative plate assay (described below).

Qualitative agar plate assays

Qualitative agar plate assays were performed as described [58]. C. elegans were synchronized and grown to the L4 stage on agar plates spread with either RNAi bacteria or OP50, as required by the experimental design. JM103-pQE9 or JM103-Cry5B bacteria were grown overnight in LB-ampicillin in a 37°C shaker. The next day, the cultures were diluted 10-fold into fresh LB-ampicillin and shaken for 1 hr at 37°C and then 50 μM IPTG was added to induce Cry5B production and the cultures were shaken for 3–4 hours at 30°C. The bacteria were diluted to an OD of 2.00 and spread onto 60mm ENG-IA plates at the indicated concentrations, usually with one set of plates spread with only JM103-pQE9 (0% plates) and another set spread with a 95:5 mixture of JM103-pQE9:JM103-Cry5B (5% plates). Plates were incubated overnight at 25°C and then ten L4 animals were placed on the plates and incubated at 20°C for 2 days. Animals were recovered and placed into glass spot wells with M9 solution with 15 mM sodium azide to paralyze them, and the wells were photographed. In the assays for Fig 4A, an additional set of plates were spread with 5% JM103-App6A, prepared identically to JM103-Cry5B.

Unfolded protein response

Synchronized hsp-4::gfp animals were grown to the L4 stage at 20°C on ENG-IA agar plates spread with RNAi bacteria. Animals were then transferred to ENG-IA agar plates that had been spread as described above with either JM103-pQE9 (0% plates) or JM103-Cry5B (100% plates) and incubated at 20°C or 30°C for eight hours. Animals were then washed from the plates and mounted in 0.1% NaN3 in M9, on slides made with 5% agar in water with 0.1% NaN3.

Pore repair assay

The experiment was performed similarly to previously-described ones [15]. Synchronized L1 animals were grown on RNAi or OP50 at 20°C. L4 stage animals were washed off the plates with ddH2O, rinsed once with ddH2O, then transferred to 100% Cry5B plates and incubated for 1 hr at 20°C. After this Cry5B pulse, worms were washed from the plates with M9 and rinsed once. Then some worms were transferred to fresh RNAi plates or OP50 plates and allowed to recover at 20°C for 26 hr, while others were immediately stained as follows. Worms were incubated in M9 with 5 mg/ml serotonin on a rotator for 15 min at room temperature, after which propidium iodide (Sigma) was added. This was incubated 40–60 min on a room-temperature rotator, after which worms were washed twice with M9 media and mounted on slides. Animals were scored positive for cytosolic PI staining if at least one of the enterocytes in the anterior half of the animal was filled with propidium iodide. At least three independent repeats were performed with 50 animals per treatment.

Actin staining experiment

N2 or nck-1(ok694) L4 animals were transferred to plates that had been spread with JM103 E. coli carrying either the pQE9 empty vector or pQE9/Cry5B and incubated at 20C for 2 hrs. Worms were then transferred to polylysine-treated glass slides in a drop of cutting buffer (5% sucrose, 100 mM NaCl, 0.02 mM levamisole (Acros cat. no. 187870100)) and the heads were sliced off using two syringe needles. The worms were fixed in 1.25% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature then placed in a Coplin jar to wash for 30 min in PBT (1X PBS, 0.1% Tween-20, 0.1% EDTA, 0.05% NaN3). Worms were then treated with 6.6 μM FITC-labeled phalloidin (SIGMA P5282) for 1 hr at room temperature and washed for 1 hr in PBT. Worms were mounted in Vectashield. Image stacks were acquired on a Leica TCS SP8 Spectral Confocal Microscope with DMi8 Inverted Stage Microscope, using LAS X software. Images were analyzed by selecting a middle slice, drawing a region around the intestine and the gonad in ImageJ, and dividing the Integrated Density of the intestine by that of the gonad. In the data set, there were two outlier animals, one in the N2 untreated group and one in the nck-1(ok694) untreated group, that showed exceptionally high background (>5X the mean integrated density). These animals were removed from analyses.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed and graphs were generated with GraphPad Prism 9.2.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). In all figures, p-values are written out, in which “n.s.” denotes “not significant.” Sigmoidal graphed data (Figs 1A, 1B, 1D, 2B, 3B, 3C, 3D, 7A, 7B and 7C) were analyzed using Prism’s nonlinear variable slope (four parameters) dose-response model log(test compound concentration; independent variable) vs. response (% alive; dependent variable). An experimental condition was determined to be significantly different from the control if the 95% confidence intervals of the logIC50 value of the two did not overlap. In bar-graph assays comparing two conditions (Figs 1C and 3A), a two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test were performed. In bar-graph assays comparing three conditions (Figs 2C, 4B, 4C, 5B, 6B and 6C), a two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test were performed. For Fig 3E, Kaplan-Meier estimate and the log-rank test were conducted. In Fig 8B, one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were conducted. LC50 and 95% confidence intervals are provided in S1 Table.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

hsp-4::gfp worms grown on the indicated RNAi bacteria to the L4 stage, moved to 30°C for heat shock, and then photographed after 8 hours of incubation at that temperature. Scale bar = 0.1mm.

(TIF)

The indicated C. elegans strains were grown to the L4 stage and subjected to the normal propidium iodide feeding protocol, with no exposure to Cry5B. Scale bar = 25um.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank You-Mie Kim with help on microscopy. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Funding Statement

This research was funded by National Institute of Healths grants R01GM071603 and R01AI056189 to RVA as well as F32GM105266 to AS. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Los FCO, Randis TM, Aroian RV, Ratner AJ. Role of Pore-Forming Toxins in Bacterial Infectious Diseases. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2013. pp. 173–207. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00052-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alouf JE. Molecular features of the cytolytic pore-forming bacterial protein toxins. Folia Microbiol. 2003;48: 5–16. doi: 10.1007/BF02931271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dal Peraro M, van der Goot FG. Pore-forming toxins: ancient, but never really out of fashion. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14: 77–92. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mesa-Galloso H, Pedrera L, Ros U. Pore-forming proteins: From defense factors to endogenous executors of cell death. Chem Phys Lipids. 2021;234: 105026. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2020.105026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huffman DL, Bischof LJ, Griffitts JS, Aroian RV. Pore worms: using Caenorhabditis elegans to study how bacterial toxins interact with their target host. Int J Med Microbiol. 2004;293: 599–607. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellier A, Chen C-S, Kao C-Y, Cinar HN, Aroian RV. Hypoxia and the hypoxic response pathway protect against pore-forming toxins in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5: e1000689. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H-D, Kao C-Y, Liu B-Y, Huang S-W, Kuo C-J, Ruan J-W, et al. HLH-30/TFEB-mediated autophagy functions in a cell-autonomous manner for epithelium intrinsic cellular defense against bacterial pore-forming toxin in C. elegans. Autophagy. 2017;13: 371–385. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1256933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C-S, Bellier A, Kao C-Y, Yang Y-L, Chen H-D, Los FCO, et al. WWP-1 is a novel modulator of the DAF-2 insulin-like signaling network involved in pore-forming toxin cellular defenses in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One. 2010;5: e9494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bischof LJ, Kao C-Y, Los FCO, Gonzalez MR, Shen Z, Briggs SP, et al. Activation of the unfolded protein response is required for defenses against bacterial pore-forming toxin in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4: e1000176. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou T-C, Chiu H-C, Kuo C-J, Wu C-M, Syu W-J, Chiu W-T, et al. EnterohaemorrhagicEscherichia coli O157:H7 Shiga-like toxin 1 is required for full pathogenicity and activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inCaenorhabditis elegans. Cellular Microbiology. 2013. pp. 82–97. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinos D, Andrés-Garrido A, Ferré J, Hernández-Martínez P. Response Mechanisms of Invertebrates to Bacillus thuringiensis and Its Pesticidal Proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2021;85. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00007-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aroian R, van der Goot FG. Pore-forming toxins and cellular non-immune defenses (CNIDs). Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10: 57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kao C-Y, Los FCO, Huffman DL, Wachi S, Kloft N, Husmann M, et al. Global functional analyses of cellular responses to pore-forming toxins. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7: e1001314. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huffman DL, Abrami L, Sasik R, Corbeil J, van der Goot FG, Aroian RV. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways defend against bacterial pore-forming toxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101: 10995–11000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404073101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Los FCO, Kao C-Y, Smitham J, McDonald KL, Ha C, Peixoto CA, et al. RAB-5- and RAB-11-dependent vesicle-trafficking pathways are required for plasma membrane repair after attack by bacterial pore-forming toxin. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9: 147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brito C, Cabanes D, Sarmento Mesquita F, Sousa S. Mechanisms protecting host cells against bacterial pore-forming toxins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76: 1319–1339. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2992-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaki SP, Rivera GM. Integration of signaling and cytoskeletal remodeling by Nck in directional cell migration. Bioarchitecture. 2013;3: 57–63. doi: 10.4161/bioa.25744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohamed AM, Chin-Sang ID. The C. elegans nck-1 gene encodes two isoforms and is required for neuronal guidance. Dev Biol. 2011;354: 55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt KL, Marcus-Gueret N, Adeleye A, Webber J, Baillie D, Stringham EG. The cell migration molecule UNC-53/NAV2 is linked to the ARP2/3 complex by ABI-1. Development. 2009;136: 563–574. doi: 10.1242/dev.016816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martynovsky M, Wong M-C, Byrd DT, Kimble J, Schwarzbauer JE. mig-38, a novel gene that regulates distal tip cell turning during gonadogenesis in C. elegans hermaphrodites. Dev Biol. 2012;368: 404–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goh KY, Ng NW, Hagen T, Inoue T. p21-activated kinase interacts with Wnt signaling to regulate tissue polarity and gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109: 15853–15858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120795109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang H, Chen K, Sandoval LE, Leung C, Wang D. An Evolutionarily Conserved Pathway Essential for Orsay Virus Infection of Caenorhabditis elegans. MBio. 2017;8. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00940-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffitts JS, Whitacre JL, Stevens DE, Aroian RV. Bt toxin resistance from loss of a putative carbohydrate-modifying enzyme. Science. 2001;293: 860–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1062441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffitts JS, Huffman DL, Whitacre JL, Barrows BD, Marroquin LD, Müller R, et al. Resistance to a bacterial toxin is mediated by removal of a conserved glycosylation pathway required for toxin-host interactions. J Biol Chem. 2003;278: 45594–45602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308142200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrows BD, Haslam SM, Bischof LJ, Morris HR, Dell A, Aroian RV. Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin in Caenorhabditis elegans from loss of fucose. J Biol Chem. 2007;282: 3302–3311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606621200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cancino-Rodezno A, Alexander C, Villaseñor R, Pacheco S, Porta H, Pauchet Y, et al. The mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 is involved in insect defense against Cry toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;40: 58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim DH, Feinbaum R, Alloing G, Emerson FE, Garsin DA, Inoue H, et al. A conserved p38 MAP kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. Science. 2002;297: 623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1073759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoue H, Hisamoto N, An JH, Oliveira RP, Nishida E, Blackwell TK, et al. The C. elegans p38 MAPK pathway regulates nuclear localization of the transcription factor SKN-1 in oxidative stress response. Genes Dev. 2005;19: 2278–2283. doi: 10.1101/gad.1324805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mertenskötter A, Keshet A, Gerke P, Paul RJ. The p38 MAPK PMK-1 shows heat-induced nuclear translocation, supports chaperone expression, and affects the heat tolerance of Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2013;18: 293–306. doi: 10.1007/s12192-012-0382-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crickmore N, Berry C, Panneerselvam S, Mishra R, Connor TR, Bonning BC. A structure-based nomenclature for Bacillus thuringiensis and other bacteria-derived pesticidal proteins. J Invertebr Pathol. 2020; 107438. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2020.107438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marroquin LD, Elyassnia D, Griffitts JS, Feitelson JS, Aroian RV. Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxin susceptibility and isolation of resistance mutants in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2000;155: 1693–1699. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.1693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dementiev A, Board J, Sitaram A, Hey T, Kelker MS, Xu X, et al. The pesticidal Cry6Aa toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis is structurally similar to HlyE-family alpha pore-forming toxins. BMC Biol. 2016;14: 71. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0295-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi J, Peng D, Zhang F, Ruan L, Sun M. The Caenorhabditis elegans CUB-like-domain containing protein RBT-1 functions as a receptor for Bacillus thuringiensis Cry6Aa toxin. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16: e1008501. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffitts JS, Haslam SM, Yang T, Garczynski SF, Mulloy B, Morris H, et al. Glycolipids as receptors for Bacillus thuringiensis crystal toxin. Science. 2005;307: 922–925. doi: 10.1126/science.1104444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hui F, Scheib U, Hu Y, Sommer RJ, Aroian RV, Ghosh P. Structure and glycolipid binding properties of the nematicidal protein Cry5B. Biochemistry. 2012;51: 9911–9921. doi: 10.1021/bi301386q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saka HA, Bidinost C, Sola C, Carranza P, Collino C, Ortiz S, et al. Vibrio cholerae cytolysin is essential for high enterotoxicity and apoptosis induction produced by a cholera toxin gene-negative V. cholerae non-O1, non-O139 strain. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2008. pp. 118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindmark B, Ou G, Song T, Toma C. A Vibrio cholerae protease needed for killing of Caenorhabditis elegans has a role in protection from natural predator grazing. Proceedings of the. 2006. Available: https://www.pnas.org/content/103/24/9280.short [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Yang W, Dierking K, Esser D, Tholey A, Leippe M, Rosenstiel P, et al. Overlapping and unique signatures in the proteomic and transcriptomic responses of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans toward pathogenic Bacillus thuringiensis. Dev Comp Immunol. 2015;51: 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Treitz C, Cassidy L, Höckendorf A, Leippe M, Tholey A. Quantitative proteome analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans upon exposure to nematicidal Bacillus thuringiensis. J Proteomics. 2015;113: 337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Huang X, Ebert D, Mills C, Guo X, et al. Protocol Update for large-scale genome and gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system (v.14.0). Nat Protoc. 2019;14: 703–721. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0128-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Ebert D, Huang X, Thomas PD. PANTHER version 14: more genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47: D419–D426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ponuwei GA. A glimpse of the ERM proteins. J Biomed Sci. 2016;23: 35. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0246-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shirao T, Hanamura K, Koganezawa N, Ishizuka Y, Yamazaki H, Sekino Y. The role of drebrin in neurons. J Neurochem. 2017;141: 819–834. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel FB, Soto MC. WAVE/SCAR promotes endocytosis and early endosome morphology in polarized C. elegans epithelia. Dev Biol. 2013;377: 319–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hupp S, Förtsch C, Wippel C, Ma J, Mitchell TJ, Iliev AI. Direct transmembrane interaction between actin and the pore-competent, cholesterol-dependent cytolysin pneumolysin. J Mol Biol. 2013;425: 636–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vega-Cabrera A, Cancino-Rodezno A, Porta H, Pardo-Lopez L. Aedes aegypti Mos20 cells internalizes cry toxins by endocytosis, and actin has a role in the defense against Cry11Aa toxin. Toxins. 2014;6: 464–487. doi: 10.3390/toxins6020464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernadskaya YY, Patel FB, Hsu H-T, Soto MC. Arp2/3 promotes junction formation and maintenance in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine by regulating membrane association of apical proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22: 2886–2899. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-10-0862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bücker R, Krug SM, Rosenthal R, Günzel D, Fromm A, Zeitz M, et al. Aerolysin from Aeromonas hydrophila perturbs tight junction integrity and cell lesion repair in intestinal epithelial HT-29/B6 cells. J Infect Dis. 2011;204: 1283–1292. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar B, Alam SI, Kumar O. Host response to intravenous injection of epsilon toxin in mouse model: a proteomic view. Proteomics. 2013;13: 89–107. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ray A, Kinch LN, de Souza Santos M, Grishin NV, Orth K, Salomon D. Proteomics Analysis Reveals Previously Uncharacterized Virulence Factors in Vibrio proteolyticus. mBio. 2016. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01077-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Djannatian JR, Nau R, Mitchell TJ. Cholesterol-dependent actin remodeling via RhoA and Rac1 activation by the Streptococcus pneumoniae toxin pneumolysin. Proceedings of the. 2007. Available: https://www.pnas.org/content/104/8/2897.short [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77: 71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Espelt MV, Estevez AY, Yin X, Strange K. Oscillatory Ca2+ signaling in the isolated Caenorhabditis elegans intestine: role of the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and phospholipases C beta and gamma. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126: 379–392. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei J-Z, Hale K, Carta L, Platzer E, Wong C, Fang S-C, et al. Bacillus thuringiensis crystal proteins that target nematodes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100: 2760–2765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0538072100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, et al. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421: 231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan M-W, Mahajan-Miklos S, Ausubel FM. Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa used to model mammalian bacterial pathogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999. pp. 715–720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michalski J, Galen JE, Fasano A, Kaper JB. CVD110, an attenuated Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor live oral vaccine strain. Infect Immun. 1993;61: 4462–4468. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4462-4468.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bischof LJ, Huffman DL, Aroian RV. Assays for toxicity studies in C. elegans with Bt crystal proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;351: 139–154. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-151-7:139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Troemel ER, Chu SW, Reinke V, Lee SS, Ausubel FM, Kim DH. p38 MAPK regulates expression of immune response genes and contributes to longevity in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2006;2: e183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

hsp-4::gfp worms grown on the indicated RNAi bacteria to the L4 stage, moved to 30°C for heat shock, and then photographed after 8 hours of incubation at that temperature. Scale bar = 0.1mm.

(TIF)

The indicated C. elegans strains were grown to the L4 stage and subjected to the normal propidium iodide feeding protocol, with no exposure to Cry5B. Scale bar = 25um.

(TIF)