Abstract

Characterization of glycerophospholipid isomers is of significant importance as they play different roles in physiological and pathological processes. In this work, we present a novel and bifunctional derivatization method utilizing Mn(II)-catalyzed epoxidation to simultaneously identify carbon-carbon double bond (C=C bond)- and stereonumbering (sn)-positional isomers of phosphatidylcholine. Mn(II) coordinates with picolinic acid and catalyzes epoxidation of unsaturated lipids by peracetic acid. Collision-induced dissociation (CID) of the epoxides generates diagnostic ions that can be used to locate C=C bond positions. Meanwhile, CID of Mn(II) ion-lipid complexes produces characteristic ions for determination of sn positions. This bifunctional derivatization takes place in seconds, and the diagnostic ions produced in CID are clear and easy to interpret. Moreover, relative quantification of C=C bond-and sn-positional isomers was achieved. The capability of this method in identifying lipids at multiple isomer levels was shown using lipid standards and lipid extracts from complex biological samples.

Introduction

Lipids are important biomolecules as they are major components of cell membranes and play many key roles in cellular functions such as energy storage and signal transduction.1, 2 Dysregulation of lipid metabolism occurs in many diseases including cancer,3–5 obesity,6 cardiovascular diseases,7, 8 and neurodegenerative diseases.9, 10 To further understand the physiological and pathological roles of lipids, accurate structural characterization is essential. Lipids are structurally diverse and often exist as mixtures of isomers. Despite subtle alternations in structures, isomers can play different roles in pathologies. Carbon-carbon double bond (C=C bond)-positional isomers result from different locations of C=C bonds in fatty acyl chains, and stereonumbering (sn)-positional isomers have distinct esterified positions of fatty acyl chains attached to the glycerol backbone.11, 12 Recent studies have shown that the ratios of these isomers are highly associated with the onset and progression of diseases such as type II diabetes and various cancers, and can be used as biomarkers for disease diagnosis.13–15 Thus, lipid structure characterization at the isomer level is highly demanded.

Mass spectrometry (MS) has been used as a powerful tool to elucidate lipid structures.16 Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) such as low-energy collision-induced dissociation (CID) can provide information on lipid acyl chain length and head group, distinguishing class/subclass and acyl chain isomers.11, 17 However, traditional CID can rarely identify C=C bond- or sn-positional isomers due to the absence of sufficient fragments cleaved at those isomeric positions.18, 19 Various activation methods have been developed to generate informative fragment ions to facilitate isomeric lipid analysis, including radical-directed dissociation (RDD),20 metastable atom activated dissociation (MAD),21 charge transfer dissociation (CTD),22 electron-impact excitation of ions from organics (EIEIO),23 ozone-induced dissociation (OzID)24 and ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD).25–27 Hyphenation of MS with high-performance liquid chromatography and ion mobility mass spectrometry provides an orthogonal dimension of separation, which helps with lipid isomer analysis.26, 28–31

Chemical derivatization of lipids prior to MS analysis can produce critical structural information on the isomeric positions upon CID. This strategy has minimal requirements for instrumentation and derivatizing reagents can be easily accessible, so it holds the potential for wide applications. Derivatization commonly focuses on the functional group at an isomeric position. The newly formed bond has reduced bond energy that can be fragmented in CID to provide isomeric structure information. Reactions such as methoxylation,32 cross-metathesis,33 methylthiolation,34 Paternò–Büchi(P-B) reaction,35, 36 ozonolysis,37, 38 singlet oxygen oxidation,39 and epoxidation40–46 were used to react with C=C bonds in lipids, and fragmentation of new bonds formed in lipid derivatives produced the ions by CID that enabled C=C bond localization. These methods have been summarized in recent reviews on lipid analysis47, 48.

The formation of metal ion-adducted lipids has also been used to generate characteristic fragment ions for isomer identification. 49–52 Silver salts can bind lipids at C=C bonds which helps with C=C bond-positional determination.49 Divalent metals such as Nickel (II) and Iron (II) salts favor the coordination with oxygen atoms in the glycerol backbone, allowing the identification of sn-positions through the observation of dominant five-membered ring fragments that includes the sn-1 chain.50, 52 The activation of these complexes favorably forms the five-membered ring fragments and releases the sn-2 chain, which allows the differentiation of sn-positional isomers.50 However, due to the derivatization of specified functional groups, it is often rare to achieve both C=C bond- and sn- positional isomer identification in a single derivatization experiment.14, 53

In this work, we present a fast and bifunctional derivatization method: Mn(II)/picolinic acid catalyzed peracetic acid (PAA) epoxidation coupled with CID to achieve simultaneous elucidation of C=C bond positions and sn positions in lipids (Scheme 1). Mn(II) plays two roles: (i) catalyzing epoxidation to determine C=C bond positions which is otherwise a slow process; and (ii) interacting with oxygens in the lipid backbone for sn-positional isomer characterization. Due to the efficiency of Mn-catalyzed reaction, the MS analysis can be performed immediately after mixing the reagents and lipids. We have applied this method to the analysis of both lipid standards and complex lipid extracts.

Scheme 1.

Simultaneous characterization of lipid C=C bond- and sn-positional isomers by Mn(II)-catalyzed epoxidation

Experimental Section

Materials

Acetonitrile (ACN), water (H2O), chloroform, methanol (MeOH), N’N-dimethylformaide (DMF), tetrahydrofuran (THF), and ethyl acetate (EtOAc) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All solvents have purity greater than 99.9% and were used without purification. Manganese bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) (also called manganese triflate, Mn(CF3SO3)2), peracetic acid (PAA), potassium hydroxide (KOH), acetic acid, and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) from porcine pancreas were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Picolinic acid, manganese chloride and potassium hydroxide were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Glycerophospholipids (GPLs), fatty acids (FAs) and egg phosphatidylcholine (PC) extract were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL).

Nomenclature

Lipid nomenclature used here refers to the guidelines by Liebisch et al.54 The positions of C=C bonds are indicated by the numbers in brackets in lipid names using Δ-nomenclature system, while the sn positions of fatty acyl chains are denoted by the symbol of “/” and the fatty acyl chains at sn-1 position are listed first followed by the ones at sn-2 position. If sn positions are not determined, the sign “_” is used. For example, PC 16:0/18:1(9) represents a PC lipid with the saturated chain 16:0 at sn-1 and chain 18:1 at sn-2 position with one C=C bond between carbon 9 and 10 from the carbonyl group.

Epoxidation of lipid standards and lipid extracts by Mn(II)/picolinic acid/PAA.

Lipid and FA standards were dissolved in ACN to achieve the concentrations of 50 μM. PAA (275 μM), Mn(CF3SO3)2 (100 μM) and picolinic acid (1μM) were added to lipid solutions followed by vortexing for 3 s before nanoelectrospray ionization (nanoESI) MS analysis. Modified PAA (PAAM, 32% PAA/10% KOH/acetic acid 13:3:10) was used to substitute PAA in experiments of analyzing fatty acids and lipid extracts from egg yolk due to its better epoxidation efficiency55 (see supporting information S1 for details). PC lipid extract from egg yolk was dissolved in ACN to achieve a concentration of 250 μM, and PAAM (500 μM), Mn(CF3SO3)2 (100 μM), and picolinic acid (10 μM) were added to the lipid solution. The solution was analyzed by nanoESI-MS immediately after mixing.

MS analysis

Lipid analysis was performed on an LTQ XL™ linear ion trap mass spectrometer from Thermo Fisher Scientific (San Jose, CA). NanoESI emitters were made from borosilicate glass tubing from WPI Inc. (Sarasota, FL) with a P-100 micropipette puller from Sutter Instrument Company (Novato, CA) using the following parameters: heat 552, pull 0, velocity 8, time 250 and pressure 500. Samples were ionized in both positive and negative ion modes with spray voltages ranging from 1.5–2.5 kV. The following MS parameters were set for data acquisition: capillary temperature was set at 275 oC; capillary voltage was −20 V and tube lens was −120 V in negative ion mode; capillary voltage was 44 V and tube lens was 85 V in positive ion mode. Full MS scans were acquired over the range of m/z 150–1000 in both ion modes, the microscan number was set at 2, and the maximum injection time was set at 200 ms. CID was used to obtain tandem mass spectra at a normalized collision energy of 30.

Results and Discussion

C=C bond-positional isomer identification by Mn(II) catalyzed epoxidation

Epoxidation of C=C bonds has been used for determination of C=C bond positions due to the key structural information gained from the cleavage of C-O bond in the three-membered ring of epoxide via CID.40, 41, 43, 44 The generation of a pair of alkene and aldehyde ions with a mass difference of 16 Da informs the C=C bond positions in lipid fatty acyl chains. Unactivated olefins can be epoxidized using peroxides such as m-CPBA40 and peracetic acid.41 These reactions often take 10 minutes to 2 hours before MS analysis and require a large excess (50 equiv.) of oxidant41 to functionalize multiple C=C bonds in polyunsaturated FAs and lipids. In order to accelerate epoxidation and improve the efficacy of oxidation for polyunsaturated lipids, transition metal catalyst Mn(CF3SO3)2 is used in this work, which enables the MS analysis immediately after mixing lipids and reagents.55–57 More importantly, the usage of Mn2+ allows for simultaneous identification of sn-positional isomers.

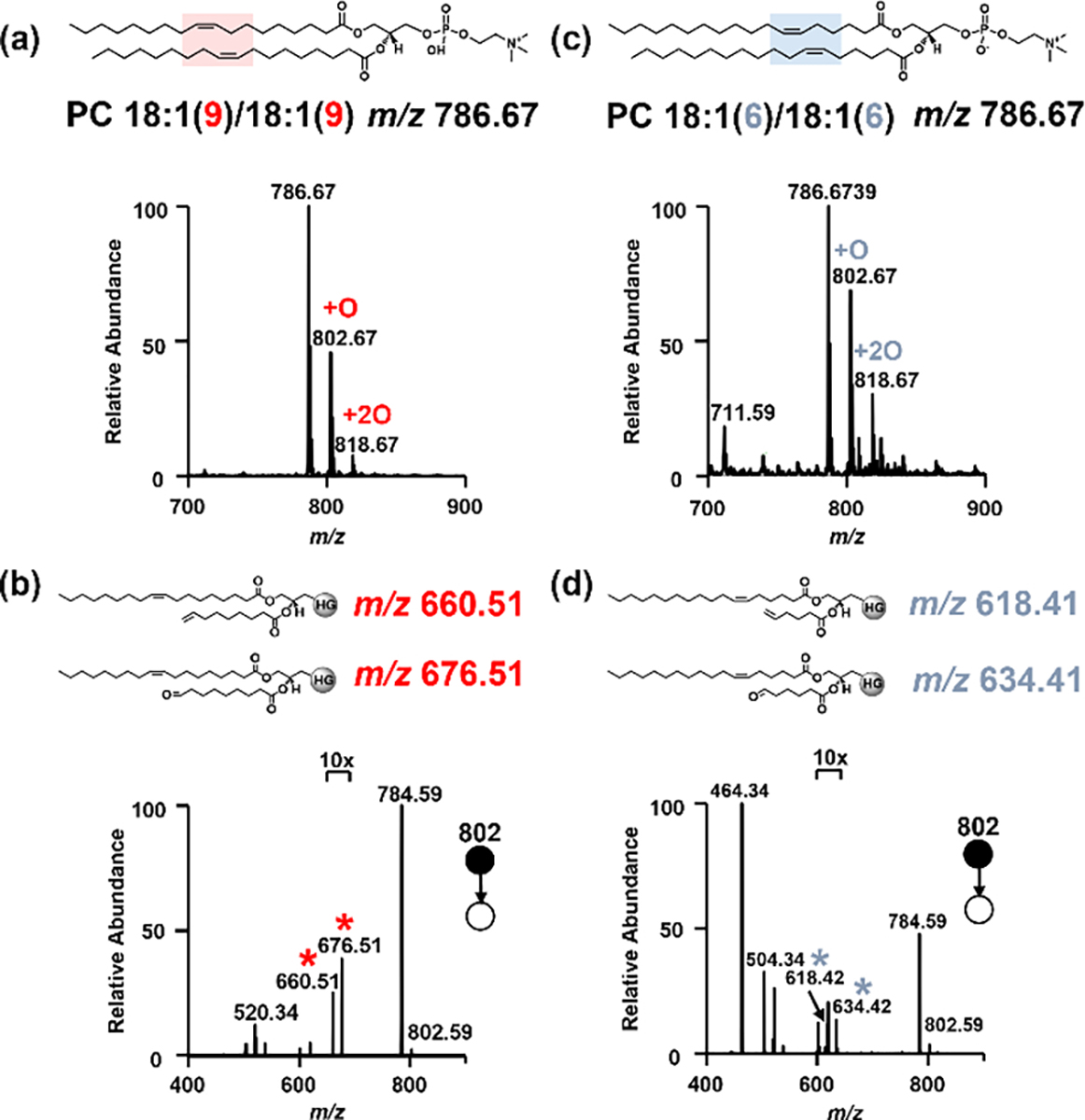

PC 18:1(9)/18:1(9) and PC 18:1(6)/18:1(6) were used to demonstrate C=C bond-positional isomer identification using Mn (II) catalyzed epoxidation. The lipid solutions (50 μM in ACN) were mixed with the oxidant PAA (165 μM), the catalyst Mn(CF3SO3)2 (0.6 μM), and its ligand picolinic acid (3 μM) in 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes and vortexed for 3 seconds. The solutions were then loaded into nanoESI emitters for MS analysis. The mono-epoxides and bi-epoxides of the two PC lipid isomers (m/z 786.59) were immediately shown at m/z 802.59 and m/z 818.59 (Figure 1 and S5). Fragmentation of the mono-epoxides in CID produced two distinctive pairs of diagnostic ions for C=C bond localization, i.e., m/z 660.51 and 676.51 indicating the C=C bond at Δ9 in PC 18:1(9)/18:1(9) and m/z 618.51 and 634.51 showing the C=C bond at Δ6 in PC 18:1(6)/18:1(6). In addition, the water loss (m/z 784.59), headgroup loss (m/z 619.50) and fatty acyl chain loss peaks (m/z 504.34 and 520.34) were observed for characterization of the headgroups, backbones, and acyl chain lengths. Optimization of the reaction was investigated at various concentrations of reagents, catalysts, and ligand (see supporting information Figure S1–3). Different solvents including ACN, MeOH, DMF, CHCl3, EtOAc, H2O and THF were examined. It was found that Mn(II) catalyzed epoxidation only occurred readily in ACN and H2O (Figure S4).

Figure 1.

Mass spectra showing epoxidation of (a) PC 18:1(9)/18:1(9), and (b) its fragmentation in CID; (c) epoxidation of PC 18:1(6)/18:1(6), and (d) its fragmentation in CID. Red and blue asterisks indicate the diagnostic fragment ions for C=C bond localization.

We further examined the scope of lipids using other classes of lipids including phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylserine (PS), and FA (Figure S7–8). These lipids prefer to be detected in negative ion mode, and their epoxides were all observed once the lipid solutions were mixed with Mn2+ and PAA. MS2 of PG and PS produced the fragments of epoxidized fatty acyl chains and further MS3 displayed the expected diagnostic ions of C=C bond positions. We also studied a representative poly-unsaturated FA, arachidonic acid FA 20:4 (5,8,11,14), which has four C=C bonds in the acyl chain. The diagnostic ions of the four double bonds were all clearly shown in the MS2 spectra at m/z 99.08 (Δ5), 139.08 and 155.08 (Δ8), 179.08 (Δ11), and 219.17 (Δ14) immediately after mixing it with the reagents (Figure S7(b)). These results indicate that the Mn(II)/picolinic acid/PAA system can be used to identify C=C bond-positional isomers in various classes of GPLs.

PC sn-Positional isomer identification via doubly charged Mn-lipid adducts

We selected Mn catalyzed epoxidation with the consideration of its potential in identifying sn-positions. Mn(II) is expected to bind tightly with the phosphate anion of the headgroup due to electron occupation in d orbitals. We used a pair of sn-positional isomers, PC 18:1(9)/16:0 and PC 16:0/18:1(9), to demonstrate the role of Mn2+ in identifying the sn-positions of acyl chains. The lipid solutions of 50 μM in ACN/H2O 4:1 were mixed with 100 μM Mn(II) salt and loaded into nanoESI emitters for MS analysis. Protonated native lipids were detected at m/z 760.59, while Mn-lipid adducts were shown at m/z 407.33. CID of the adducts of these two isomers results in distinct patterns of fragment ions due to the attachment of acyl chains at sn-positions. The activation of [PC 18:1(9)/16:0 +Mn]2+ favored the formation of five-membered ring with acyl chain 18:1, which produced dominant fragment ions at m/z 504.34 ([Lipid-FAsn-2]+) and 310.17 ([Mn+FAsn-2]+). In comparison, the activation of [PC 16:0/18:1(9)+Mn]2+ generated dominant fragment ions of a five-membered ring with acyl chain 16:0 at m/z 478.34 ([Lipid-FAsn-2]+) and its corresponding Mn2+ adducted acyl chain 18:1 at m/z 336.17 ([Mn+FAsn-2]+). Based on the obvious ion abundance alternation of these two pairs of characteristic fragments, sn positions of the fatty acyl chains in the two lipid isomers were determined (Figure 2). The fragment ions with a six-membered ring formed in a competitive but disfavored fragmentation pathway were also shown in Scheme 1. It is worth noting that the diagnostic ions for determination of sn-positions generated from Mn-lipid adducts were much more abundant than the headgroup loss ions50 which are often the dominant fragments in lipid adducts with commonly used metals like Na+ and K+.

Figure 2.

Mass spectra of (a) Mn adduct of PC 18:1(9)/16:0 and its fragmentation upon CID. Mass spectra of (c) Mn adduct of PC 16:0/18:1(9), and (d) its fragmentation upon CID. Asterisks indicate the characteristic fragment ions of sn-positions.

When PCs were replaced with other classes of lipids such as PG, PS and FA, singly charged Mn-lipid adducts were observed in the full mass spectra (Figure S9–12). However, fragmentation of these Mn-lipid adducts via CID did not produce diagnostic ions as shown in PC lipids. For example, the majority ions after fragmentation of Mn-fatty acid adducts stemmed from the charge-remote fragmentation due to the π-Mn interactions instead of Mn-O coordination (Figure S9). Therefore, determination of sn-positions of PC lipids can be achieved by fragmenting metal adducts upon CID. Other lipids from classes such as PG, PS and PE can produce Mn-lipid adducts, but the fragmentation of the adducts cannot provide ions for sn-position determination. The following work is focused on PC sn-positional isomer identification.

Identification of PC C=C bond- and sn- positional isomers using Mn(II)-catalyzed epoxidation

Next, the feasibility of Mn(II)-catalyzed epoxidation in simultaneous identification of C=C bond- and sn-positional isomers was studied. PC 18:1(9)/16:0 and PC 16:0/18:1(9) were prepared at 50 μM in ACN and mixed with 275 μM PAA, 100 μM Mn(CF3SO3)2 and 1 μM picolinic acid. The nanoESI-MS analysis of the mixture showed that the native lipids, epoxidized lipids, and their Mn-lipid adducts were detected at m/z 760.59, 776.59, and 407.33, respectively in the full mass spectrum (Figure 3). Fragmentation of epoxidized lipids in CID produced the diagnostic ions of C=C bond at Δ9 (i.e., m/z 634.51 and 650.51). Fragmentation of Mn-lipid adducts generated dominant sn-positional characteristic ions at m/z 310.25 & 504.50 for PC 18:1(9)/16:0 and m/z 336.25 & 478.42 for PC 16:0/18:1(9) (Figure 3). PC 18:1(9)/18:1(9) and PC 18:1(6)/18:1(6) were also examined with unambiguous diagnostic ions for C=C bond and sn positions (Figure S13). These results indicate that Mn(II)-catalyzed epoxidation can identify the two types of PC isomers in a single experiment.

Figure 3.

Mass spectra of (a) Mn-catalyzed epoxidation of a mixture of PC 18:1(9)/16:0 and PC 16:0/18:1(9); Tandem mass spectra of (b) PC 18:1(9)/16:0 and (c) PC 16:0/18:1(9) showing the fragmentation of Mn-adducts at m/z 407.34 for identification of sn-positions, and the fragmentation of epoxide ions at m/z 776.67 for identification of C=C bond- positions in a single experiment. Asterisks indicate the diagnostic fragment ions of C=C bond and sn positions.

In addition, we observed Mn adducts of epoxidized lipids at m/z 415.33. Although the fragment ion at m/z 210.08 (from parent ion at m/z 352.25, [Mn+C9H16O2]+) could also be used for C=C bond position identification, no obvious disparate ions were observed to distinguish sn-positional isomers because [Mn+epoxidized FA]+ and [Mn+lipid-epoxidized FA]+ always dominated the tandem mass spectra (Figure S14). This might be due to the preference of Mn binding to the oxygen atom in the oxirane after epoxidation. Other divalent metal ions such as Cu2+, Fe2+, and Co2+ were investigated for catalyzing epoxidation and forming metal adducts, but were not superior to Mn2+ (Figure S15 and S6). The detection limit of the method using Mn2+ was evaluated using PC 18:1(9)/18:1(9) and PC 16:0/18:1(9), and the diagnostic ions for both C=C bond-and sn-positional isomers could be observed at a concentration of 1 μM (Figure S17–18).

Relative quantification of C=C bond- and sn-positional isomers

Relative quantification of C=C bond- and sn-positional isomers was conducted using diagnostic fragment ions produced from Mn(II)-catalyzed epoxidation products and Mn-lipid adducts. Quantification of C=C bond-positional isomers was performed with PC 18:1(9)/18:1(9) and PC 18:1(6)/18:1(6) (Figure 4a). The calibration curve was constructed by plotting the intensity ratio of diagnostic ions against the ratio of lipid isomer concentrations. The intensity ratios of their diagnostic ions were calculated as (I660 + I676)/(I618 + I634), where ‘I’ refers to ion intensities. The total concentration of these two isomers was maintained at 50 μM, while the concentrations of individual isomers varied from 0, 10, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45 μM. The concentration ratios of these two isomers were calculated as C(PC 18:1(9)/18:1(9))/C(PC 18:1(6)/18:1(6)). A linear relationship was observed with a good R2 value of 0.997.

Figure 4.

Relative quantification of (a) C=C bond-positional isomers, PC 18:1(9)/18:1(9) and PC 18:1(6)/18:1(6) and (b) sn-positional isomers, PC 18:1(9)/16:0 and PC 16:0/18:1(9).

Quantification of sn-positional isomers was carried out with PC 16:0/18:1(9) and PC 18:1(9)/16:0 (Figure 4b). The intensity fraction of a pair of the diagnostic ions was calculated as (I310 + I504)/(I310 + I504+ I336 + I478), and the concentration fraction of the corresponding isomer was calculated as C(PC 18:1(9)/16:0)/C(PC 16:0/18:1(9) + PC 18:1(9)/16:0). The total concentration of these two isomers was maintained at 50 μM, while the concentrations of individual isomers were 0, 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 μM. A linear relationship between the ion intensity fraction and the concentration fraction was found with an R2 value of 0.999 (Figure 4b) when isolation window width of 2.5 was applied. The result is comparable to that using PLA2 hydrolysis method (Figure S19). We observed that the selection of isolation window width affected the accuracy of quantification. With an isolation window smaller than 1.5 units, the intensity of fragments from Mn-lipid adducts dropped, which diminished the linear relationship between the characteristic fragment ions and lipid isomer ratio (Figure S20).

Analysis of complex lipid mixture with Mn(II)-catalyzed-epoxidation

We then applied the method to the analysis of the PC lipid extract from egg yolk obtained from Avanti. The lipid extract was dissolved in ACN to achieve a concentration of 0.2 μg/μL (250 μM). The lipid solution was mixed with PAAM (500 μM), Mn salt (100 μM), picolinic acid (10 μM), and 1% formic acid before the mixture was subjected to nanoESI-MS analysis (Figure S21). After epoxidation, Lipids with +16 Da and + 32 Da signals were observed in the m/z range of 700–850 in both positive and negative ion modes. Mn-lipid adducts were shown in the range of m/z 400–500. Fragmentation of epoxidation products and Mn-lipid adducts provided the diagnostic ions or characteristic fragment ions for C=C bond- and sn-positional determination. In addition, CID of the protonated lipids produced the structural information on head groups and acyl chain lengths.

Characterization of PC 16:0_18:2 was illustrated as an example (Figure S21). The protonated lipid was shown at m/z 758.67, and CID produced ions at m/z 575.50 (−183 Da) indicating the loss of the phosphatidylcholine group. Other fragment ions at m/z 478.35 (−280 Da), 496.34 (−262 Da) and m/z 502.17 (−256 Da), 520.25 (−238 Da) resulted from the loss of fatty acyl chain 18:2 and 16:0. The mono-epoxide was found at m/z 774.58 (+ 16 Da), and the CID diagnostic fragment ions at m/z 634.50 & 650.50 and m/z 674.51 & 690.51 indicating the locations of C=C bonds at Δ9 and Δ12 in fatty acyl chain 18:2. The Mn-lipid adduct was shown at m/z 406.33, and its fragmentation via CID produced ions at m/z 334.17 and m/z 478.34, indicating the fatty acyl chain 16:0 at sn-1 position and 18:2 at sn-2 position. The other pair of characteristic fragment ions for sn-positional isomer was not observed, hence, PC 16:0_18:2 was determined as PC 16:0/18:2(9,12). In total, 12 chain length isomers, 19 C=C bond-positional isomers, and 12 sn-positional isomers were characterized using Mn(II)-catalyzed epoxidation from 7 PC lipids shown in the full mass spectrum (Table 1).

Table 1.

C=C bond- and sn-positional isomers in the PC extract of egg yolk identified via Mn(II)-catalyzed epoxidation.

| Protonated ion | Chain length isomer | db-Positional isomer | sn-positional isomer |

|---|---|---|---|

| [M+H]+ | (CID@[M+H]+) | (CID@[M+O+H]+) | (CID@[M+Mn]2+) |

|

| |||

| 732.59 | PC 16:1_16:0 | PC 16:1(9)_16:0 | PC 16:0/16:1 |

| PC 16:1(7)_16:0 | |||

| PC 18:1_14:0 | PC 18:1(11)_14:0 | PC 14:0/18:1 | |

| PC 18:1(9)_14:0 | |||

|

| |||

| 758.67 | PC 18:2_16:0 | PC 18:2(9,12)_16:0 | PC 16:0/18:2 |

| PC 18:1_16:1 | PC 18:1(9)_16:1(9) | PC 16:1/18:1 | |

|

| |||

| 760.67 | PC 18:1_16:0 | PC 18:1(9)_16:0 | PC 16:0/18:1 |

| PC 18:1(11)_16:0 | |||

| PC 18:1(12)_16:0 | |||

|

| |||

| 784.59 | PC 18:2_18:1 | PC 18:2(9,12)_18:1(9) | PC 18:1/18:2 & PC 18:2/18:1 |

| PC 20:3_16:0 | PC 20:3(5,11,14)_16:0 | PC 16:0/20:3 | |

|

| |||

| 786.67 | PC 18:1_18:1 | PC 18:1(9)_18:1(9) | PC 18:1/18:1 |

| PC 18:1(12)_18:1(12) | |||

| PC 18:1(9)_18:1(12) | |||

| PC 18:2_18:0 | PC 18:1(9,12)_18:0 | PC 18:0/18:2 | |

|

| |||

| 788.67 | PC 18:1_18:0 | PC 18:1(9)_18:0 | PC 18:0/18:1 |

| PC 18:1(11)_18:0 | |||

| PC 20:1_16:0 | PC 20:1(11)_16:0 | PC 16:0/20:1 | |

|

| |||

| 810.67 | PC 20:4_18:0 | PC 20:4(5,8,11,14)_18:0 | PC 18:0/20:4 |

Conclusions

We have developed a bifunctional derivatization method coupled with nanoESI-MS/MS for simultaneous characterization of PC lipid C=C bond- and sn-positional isomers. The method uses Mn(II), picolinic acid, and peracetic acid to form epoxidized lipids and Mn-lipid adducts, followed by CID of them to generate diagnostic/characteristic fragment ions for determination of C=C bond and sn-positions. The feasibility of the method has been demonstrated with lipid standards and a PC mixture. Considering its capability of identifying lipid isomers at multiple isomer levels in a single experimental run, superfast reaction rate, mild reaction condition, and direct coupling with a commercial mass spectrometer without instrumental modification, this method holds great potential in lipidomic studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the NIH NIGMS Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award MIRA (R35GM143047) and Welch grant (A-2089) for financial support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

References

- 1.Shevchenko A and Simons K, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol, 2010, 11, 593–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harayama T and Riezman H, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol, 2018, 19, 281–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo X, Cheng C, Tan Z, Li N, Tang M, Yang L and Cao Y, Mol. Cancer, 2017, 16, 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beloribi-Djefaflia S, Vasseur S and Guillaumond F, Oncogenesis, 2016, 5, e189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng C, Geng F, Cheng X and Guo D, Cancer Commun, 2018, 38, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parekh S and Anania FA, Gastroenterology, 2007, 132, 2191–2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pechlaner R, Kiechl S and Mayr M, Circulation, 2016, 134, 1651–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han X, Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 2022, 18, 335–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadav RS and Tiwari NK, Mol. Neurobiol, 2014, 50, 168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mesa-Herrera F, Taoro-González L, Valdés-Baizabal C, Diaz M and Marín R, Int. J. Mol. Sci, 2019, 20, 3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rustam YH and Reid GE, Anal. Chem, 2018, 90, 374–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown SHJ, Mitchell TW and Blanksby SJ, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2011, 1811, 807–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Zhang D, Chen Q, Wu J, Ouyang Z and Xia Y, Nat. Commun, 2019, 10, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao W, Cheng S, Yang J, Feng J, Zhang W, Li Z, Chen Q, Xia Y, Ouyang Z and Ma X, Nat. Commun, 2020, 11, 375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paine MRL, Poad BLJ, Eijkel GB, Marshall DL, Blanksby SJ, Heeren RMA and Ellis SR, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2018, 57, 10530–10534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han X and Gross RW, Mass Spectrom. Rev, 2005, 24, 367–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hancock SE, Poad BLJ, Batarseh A, Abbott SK and Mitchell TW, Anal. Biochem, 2017, 524, 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ekroos K, Ejsing CS, Bahr U, Karas M, Simons K and Shevchenko A, J. Lipid Res, 2003, 44, 2181–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu F-F and Turk J, J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom, 2008, 19, 1681–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pham HT, Ly T, Trevitt AJ, Mitchell TW and Blanksby SJ, Anal. Chem, 2012, 84, 7525–7532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deimler RE, Sander M and Jackson GP, Int. J. Mass spectrom, 2015, 390, 178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li P and Jackson GP, J. Mass Spectrom, 2017, 52, 271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell JL and Baba T, Anal. Chem, 2015, 87, 5837–5845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas MC, Mitchell TW, Harman DG, Deeley JM, Murphy RC and Blanksby SJ, Anal. Chem, 2007, 79, 5013–5022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams PE, Klein DR, Greer SM and Brodbelt JS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 15681–15690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macias LA, Garza KY, Feider CL, Eberlin LS and Brodbelt JS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2021, 143, 14622–14634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feider CL, Macias LA, Brodbelt JS and Eberlin LS, Anal. Chem, 2020, 92, 8386–8395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyle JE, Zhang X, Weitz KK, Monroe ME, Ibrahim YM, Moore RJ, Cha J, Sun X, Lovelace ES, Wagoner J, Polyak SJ, Metz TO, Dey SK, Smith RD, Burnum-Johnson KE and Baker ES, Analyst, 2016, 141, 1649–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng X, Smith RD and Baker ES, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol, 2018, 42, 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poad BLJ, Zheng X, Mitchell TW, Smith RD, Baker ES and Blanksby SJ, Anal. Chem, 2018, 90, 1292–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng G, Gao M, Wang L, Chen J, Hou M, Wan Q, Lin Y, Xu G, Qi X and Chen S, Nat. Commun, 2022, 13, 2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minnikin DE, Chem. Phys. Lipids, 1978, 21, 313–347. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwon Y, Lee S, Oh D-C and Kim S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2011, 50, 8275–8278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Francis GW, Chem. Phys. Lipids, 1981, 29, 369–374. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma X and Xia Y, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2014, 53, 2592–2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma X, Chong L, Tian R, Shi R, Tony Y. H, Ouyang Z and Xia Y, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2016, 113, 2573–2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas MC, Mitchell TW and Blanksby SJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2006, 128, 58–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas MC, Mitchell TW, Harman DG, Deeley JM, Nealon JR and Blanksby SJ, Anal. Chem, 2008, 80, 303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unsihuay D, Su P, Hu H, Qiu J, Kuang S, Li Y, Sun X, Dey SK and Laskin J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2021, 60, 7559–7563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng Y, Chen B, Yu Q and Li L, Anal. Chem, 2019, 91, 1791–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang H, Xu M, Shi X, Liu Y, Li Z, Jagodinsky JC, Ma M, Welham NV, Morris ZS and Li L, Chem. Sci, 2021, 12, 8115–8122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cao W, Ma X, Li Z, Zhou X and Ouyang Z, Anal. Chem, 2018, 90, 10286–10292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang S, Cheng H and Yan X, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2020, 59, 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chintalapudi K and Badu-Tawiah AK, Chem. Sci, 2020, 11, 9891–9897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang S, Fan L, Cheng H and Yan X, J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom, 2021, 32, 2288–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wan L, Gong G, Liang H and Huang G, Anal. Chim. Acta, 2019, 1075, 120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang W, Jian R, Zhao J, Liu Y and Xia Y, J. Lipid Res, 2022, 63, 100219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu H, Zhang H, Xu S and Li L, Metabolites, 2021, 11, 781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sehat N, Kramer JKG, Mossoba MM, Yurawecz MP, Roach JAG, Eulitz K, Morehouse KM and Ku Y, Lipids, 1998, 33, 963–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becher S, Esch P and Heiles S, Anal. Chem, 2018, 90, 11486–11494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoo HJ and Håkansson K, Anal. Chem, 2010, 82, 6940–6946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ho Y-P, Huang P-C and Deng K-H, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom, 2003, 17, 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao X, Zhang W, Zhang D, Liu X, Cao W, Chen Q, Ouyang Z and Xia Y, Chem. Sci, 2019, 10, 10740–10748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liebisch G, Vizcaíno JA, Köfeler H, Trötzmüller M, Griffiths WJ, Schmitz G, Spener F and Wakelam MJO, J. Lipid Res, 2013, 54, 1523–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moretti RA, Du Bois J and Stack TDP, Org. Lett, 2016, 18, 2528–2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huber S, Cokoja M and Kühn FE, J. Organomet. Chem, 2014, 751, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joergensen KA, Chem. Rev, 1989, 89, 431–458. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.