With the continuous growth and connectedness of the human population, there is an increased threat of emerging and re-emerging diseases. These threats are often exacerbated by the environmental and sociopolitical crises facing humanity. The unprecedented speed at which the COVID-19 pandemic spread worldwide highlights the urgent need to address the issues that increase risks of disease emergence and spread. Such risks can be addressed through bolstering global surveillance and increasing concerted efforts to mitigate disease spread locally. After local emergence of any disease, an understanding of the geographical risks of widespread transmssion is fundamental for preparedness and resource allocation strategies to contain the disease before it becomes a global health emergency. For re-emerging diseases, it is crucial to evaluate the immunity landscape. In The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Juliana C Taube and colleagues1 use demographic modelling to generate a comprehensive and granular global immunity landscape for smallpox vaccination coverage. The authors developed an innovative approach that incorporates country-specific historical vaccination data with data on demographic growth to assess age-distributed pre-existing smallpox immunity, a proxy for orthopoxvirus immunity.

Since the identification of an initial cluster of monkeypox cases in the UK on May 14, 2022, monkeypox has been reported in more than 90 countries where it had not previously circulated.2 Several observational studies in past have shown that vaccination against smallpox might provide up to 85% protection against monkeypox for 3–5 years.3 Although routine vaccination against smallpox worldwide ceased by 1980, individuals who received smallpox vaccination might still have some protection against monkeypox. Therefore, understanding the smallpox vaccination coverage among the current population could be instrumental in identifying subpopulations most susceptible to infection and areas where widespread outbreaks are most probable. Accounting for the cross-immunity by smallpox vaccination and waning efficacy, Taube and colleagues1 combine country-specific data on smallpox vaccination coverage before cessation of the routine vaccination campaign in that country along with data on current demography to generate a global landscape of susceptibility to orthopoxviruses including for monkeypox.

Characterisation of the global spatial landscape for vulnerability to orthopoxviruses by Taube and colleagues1 showed that the age-specific coverage at the time of cessation of routine vaccination was the primary factor in determining the current spatial heterogeneity in susceptibility across the globe. Their finding was consistent with the observed median age of 37 (IQR 32–43) years for monkeypox infections globally,4 and suggested previous immunity through the smallpox vaccine might be protecting the older population from monkeypox infection. Similarly, the influenza A H1N1 pandemic in 2009 mostly affected the young population as the older population had previous immunity.5 An accurate understanding of the immunity landscape for H1N1, such as that generated by Taube and colleagues1 for smallpox, would have informed swift and optimal allocations of vaccines.6

The current multicountry monkeypox outbreak has disproportionately affected men who have sex with men. The rapid rollouts of vaccination with prioritisation of men who have sex with men in several countries have been effective in mitigating ongoing transmission.7 In addition to monkeypox, the risk of outbreaks from other orthopoxviruses, such as cowpox and buffalopox, has been increasing.8, 9 Beyond orthopoxviruses, global databases for immunity profiles of other vaccine-preventable diseases have become more crucial now than ever. Pandemic-driven restrictions, economic disruptions, and resource reallocations have caused reductions in routine immunisations for multiple diseases across the world.10 In 2021, 25 million children did not receive vaccines against preventable diseases such as measles and poliovirus.11 Moreover, misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines has exacerbated hesitancy towards vaccination more broadly.12 Although there remain only two poliovirus-endemic countries (Afghanistan and Pakistan), the recent identification of polio cases in non-endemic countries such as the USA and the UK underscores the importance of maintaining high vaccination coverage.13 Global assessment of the immunity landscape of vaccine-preventable diseases, as developed by Taube and colleagues,1 can identify locations that most need surveillance and proactive action.

Future extensions of the Taube and colleagues1 framework could capture the interplay of the immunity landscape with the shifting of viable geographical range for pathogens to identify areas that are at greatest risk of disease emergence and spread.14 Another dimension that could be incorporated in extensions of the framework is the sociopolitical factors that can affect transmission rates. For example, political destabilisation coinciding with drought from climate change has stoked a devastating cholera outbreak in Yemen, with disease fatality rates compounded by malnutrition.15 The foundational study by Taube and colleagues1 paves the way to develop novel approaches to understanding the complex interplay between immunological, climate, and sociopolitical systems that can improve prediction and proactively curb disease outbreaks worldwide.

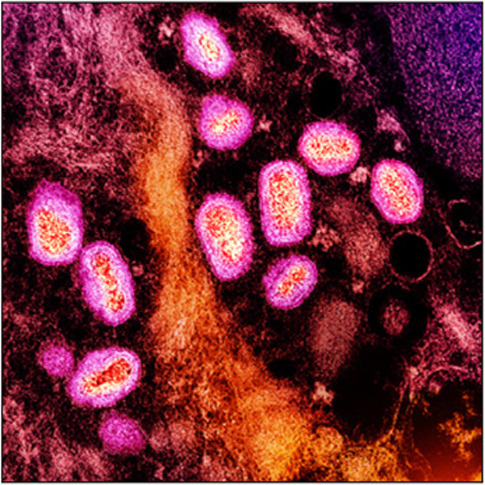

© 2023 Flickr - NIAID

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Taube JC, Rest EC, Lloyd-Smith JO, Bansal S. The global landscape of smallpox vaccination history and implications for current and future orthopoxvirus susceptibility: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00664-8. Published online Nov 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reuters . Reuters; Oct 28, 2022. Factbox: monkeypox cases and deaths around the world.https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/monkeypox-cases-around-world-2022-05-23/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Monkeypox. May 19, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

- 4.WHO Multi-country monkeypox outbreak: situation update. June 17, 2022. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON393

- 5.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009 H1N1 Pandemic (H1N1pdm09 virus) June 11, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/2009-h1n1-pandemic.html

- 6.Medlock J, Galvani AP. Optimizing influenza vaccine distribution. Science. 2009;325:1705–1708. doi: 10.1126/science.1175570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kupferschmidt K. Monkeypox cases are plummeting. Scientists are debating why. Oct 26, 2022. https://www.science.org/content/article/monkeypox-cases-are-plummeting-scientists-are-debating-why

- 8.Eltom KH, Samy AM, Abd El Wahed A, Czerny C-P. Buffalopox virus: an emerging virus in livestock and humans. Pathogens. 2020;9:E676. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9090676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vorou RM, Papavassiliou VG, Pierroutsakos IN. Cowpox virus infection: an emerging health threat. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:153–156. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f44c74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UNICEF COVID-19 pandemic fuels largest continued backslide in vaccinations in three decades. July 14, 2022. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/WUENIC2022release

- 11.Guglielmi G. Pandemic drives largest drop in childhood vaccinations in 30 years. Nature. 2022;608:253. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-02051-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opel DJ, Brewer NT, Buttenheim AM, et al. The legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic for childhood vaccination in the USA. Lancet. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01693-2. published online Oct 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKenna M. Wired; Aug 24, 2022. Polio is back in the US and UK. Here's how that happened.https://www.wired.com/story/polio-is-back-in-the-us-and-uk-heres-how-that-happened/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mora C, McKenzie T, Gaw IM, et al. Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change. Nat Clim Chang. 2022;12:869–875. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01426-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.UN Yemen hit by world's worst cholera outbreak as cases reach 200,000. June 24, 2017. https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/06/560332