Summary

Background

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has evolved quickly, with numerous waves of different variants of concern resulting in the need for countries to offer continued protection through booster vaccination. To ensure adequate vaccination coverage, Thailand has proactively adopted heterologous vaccination schedules. While randomised controlled trials have assessed homologous schedules in detail, limited data has been reported for heterologous vaccine effectiveness (VE).

Methods

Utilising a unique active surveillance network established in Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand, we conducted a test-negative case control study to assess the VE of heterologous third and fourth dose schedules against SARS-CoV-2 infection among suspect-cases during Oct 1–Dec 31, 2021 (delta-predominant) and Feb 1–Apr 10, 2022 (omicron-predominant) periods.

Findings

After a third dose, effectiveness against delta infection was high (adjusted VE 97%, 95% CI 94–99%) in comparison to moderate protection against omicron (adjusted VE 31%, 95% CI 26–36%). Good protection was observed after a fourth dose (adjusted VE 75%, 95% CI 71–80%). VE was consistent across age groups for both delta and omicron infection. The VE of third or fourth doses against omicron infection were equivalent for the three main vaccines used for boosting in Thailand, suggesting coverage, rather than vaccine type is a much stronger predictor of protection.

Interpretation

Appropriately timed booster doses have a high probability of preventing COVID-19 infection with both delta and omicron variants. Our evidence supports the need for ongoing national efforts to increase population coverage of booster doses.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) under The Smart Emergency Care Services Integration (SECSI) project to Faculty of Public Health Chiang Mai University.

Keywords: Effectiveness of heterologous COVID-19 vaccines, Booster dose, Omicron, Delta

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The COVID-19 pandemic has evolved quickly, with numerous waves of different variants of concern resulting in the need for countries to adopt heterologous vaccination schedules to ensure adequate coverage. Limited data has been reported for heterologous vaccine effectiveness against delta and omicron variants. We searched “PubMed”, “medRxiv”, websites of public health organizations including “World Health Organization”, “Centers for Disease and Control, USA” and “UK Health Security Agency” for articles up to 01 July, 2022, using the search terms “SARS CoV-2” OR “COVID-19”, AND “vaccine effectiveness” AND “heterologous”.

Majority of studies assessed the effectiveness of heterologous vaccine schedules against early variants of concern. Reported vaccine effectiveness (VE) against infection for omicron variant is consistently lower than for the delta variant, but majority of studies assessed homologous series. Very little real-world data exist for schedules which incorporates inactivated vaccines and fourth dose schedules.

Added value of this study

We found high VE against delta infection (adjusted VE 97%, 95% CI 94–99%), but moderate VE (adjusted VE 31%, 95% CI 26–36%) against omicron infection after third dose, while a fourth dose provided good protection against omicron infection (adjusted VE 75%, 95% CI 71–80%). The VE values were equivalent for the three main vaccine types, BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech), ChAdOx1 (AstraZeneca) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna), used for boosting in Thailand. This suggests that coverage, rather than vaccine type is a much stronger predictor of protection.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our paper provides much needed evidence to supports the ongoing national efforts to increase population coverage of booster doses. Our data supports the use of ChAdOx1, BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 as booster vaccines, providing much needed flexibility to incorporate different vaccines into schedules according to local supply and logistical considerations.

Introduction

As of November 9, 2022, the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has led to more than 638 million confirmed cases globally with more almost 200 million in Asia and 4.7 million in Thailand alone.1 Almost 6.6 million deaths were reported worldwide, with almost 1.5 million deaths across Asia and over 33,000 in Thailand.1 COVID-19 pandemic has also created an enormous burden on healthcare, on people and on the economy.2,3 While public health measures like wearing of masks, social distancing and appropriate hygiene measures were able to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2, it was the rapid development and deployment of vaccines which reduced the impact of COVID-19 substantially.4,5

WHO has licensed 11 COVID-19 vaccines to date and globally over 12 billion doses have been administered.6 While these vaccines have had an enormous impact in countries that have achieved high coverage rates, as at May 22, 2022, only 57 countries have vaccinated 70% of their population and almost one billion people in lower-income countries remain unvaccinated.7 There are six approved COVID-19 vaccines in Thailand8 and a sustained effort by the government has resulted in 83% of the population being fully vaccinated (two doses) and an additional 47% receiving three doses or above as of October 21, 2022.1,9

Randomised controlled clinical trials demonstrated several COVID-19 vaccines to be safe and immunogenic in homologous schedules, with high efficacy against both symptomatic infection and severe outcomes such as hospitalisation and death. This enabled the rapid emergency use authorisation and initial rollout of the following vaccines in Thailand: CoronaVac (Sinovac) in March 202110 ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca) in June 202111 and BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) in October 2021.12

Subsequently, most of the initial vaccinations in Thailand were given as two doses of CoronaVac for people aged 18–59 years old or two doses of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 for those who aged 60 or above. People living with chronic medical conditions such as coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, cancer patients on chemotherapy, were given priority for vaccination. With the arrival of BNT162b2, doses were initially targeted to younger age groups (>12 years). Due to challenges in vaccine supply and to manage concerns around the effectiveness and duration of CoronaVac, “mix and match” vaccine schedules were implemented from July 2021 onwards including third dose (boosters) with ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and BNT162b2. Small number of fourth doses (second booster) were administered to high-risk individuals throughout Q4 2021 but were implemented more widely beginning in January 2022, using BNT162b2, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and Spikevax (Moderna) in part to address additional concerns around potential immune escape by the omicron variant. The majority of fourth doses vaccines in Thailand have been administered to individuals receiving a two-dose CoronaVac primary series. The initial global clinical trials evaluated efficacy of vaccines (using homologous schedules) against early variants of concern. The most widely used vaccines in real world studies showed high and equivalent effectiveness, especially against severe COVID-19 outcomes.13 Some studies have reported higher neutralizing-antibody response with heterologous boosters as compared to homologous boosters.14, 15, 16, 17 However, there is limited data available on the real-world vaccine effectiveness (VE) of heterologous schedules, particularly against the newer omicron variants.18,19 Reports of waning antibody titres and protection against infections, particularly with the omicron variant(s) have driven the rollout of booster doses globally, and hence, it is critical to evaluate the effectiveness of additional doses. The evaluation becomes even more relevant for Asian countries where heterologous schedules have been widely used.

The current study draws on a unique active surveillance network20 established in Chiang Mai, located in Northern Thailand, with a population of 1.6 million. The comprehensive system allows serial assessment of VE for SARS-CoV-2 infection of heterologous schedules during delta-predominant and omicron-predominant periods in the same population. The primary objectives of the study were to evaluate the effectiveness of heterologous three dose COVID-19 vaccine schedules for SARS-CoV-2 infection during delta-predominant period, and to evaluate the effectiveness of heterologous three dose and four dose COVID-19 vaccine schedules for SARS-CoV-2 infection during omicron-predominant period.

Methods

Study population

Residents of Chiang Mai, Thailand, aged 18 years or older, presenting to any community-based testing facilities for a SARS-CoV-2 test during Oct 01–Dec 31, 2021 (delta-predominant) and Feb 01–April 10, 2022 (omicron-predominant) were assessed for eligibility to be included in the study. Molecular testing revealed 96.5% delta and 95.6% omicron lineage during Oct 1–Dec 31, 2021 and Feb 1–April 10, 2022 periods respectively. Tests done in Jan 2022 were excluded due to mixed delta-omicron lineage among samples (omicron 75%, Delta 25%). The data capture ended on April 10, 2022, which was the last date when the community testing ended in Chiang Mai, and shifted to self-testing.

Subjects were included in the study if they met suspect-case criteria, i.e. either close-contacts of COVID-19 cases or attended an event where a COVID-19 outbreak was detected or had symptoms suggestive of COVID-19. Those with uncertain exposure were excluded. Non-Thai residents (foreigners and migrants) were excluded as the vaccination and other data for this group may be incomplete.

The patient selection flow is presented under Supplementary Figure 1a and b.

Data sources

We have previously published the details on creating and implementing the information systems used in this study.19 In brief: COVID-19 cases are reported in the surveillance system of Chiang Mai Provincial Health Office (Epid-CM platform), under the Communicable Disease Control Act (B.E. 2558) which mandates national reporting of all COVID-19 cases. After detection of COVID-19 case, the patient details, including laboratory results are entered into the system under a unique individual ID. Epid-CM is synchronized with Chiang Mai hospital management platform for COVID-19 (CMC-19 platform). Data on progression of the disease and treatments are recorded in each hospital information system. Death cases are reported to Chiang Mai Provincial Health Office and recorded in Epid-CM.

Community-based testing sites were initiated in the city of Chiang Mai since April 2021 and provided free COVID-19 tests. Those tested included close contacts of COVID-19 cases, attendees of an event with a COVID-19 outbreak, or those with suggestive respiratory symptoms. Health personnel performed either RT-PCR (November 2021 to January 2022) or antigen testing (February 2022 onwards), and results were uploaded in Epid-CM.

All national vaccination records are available from the Ministry of Public Health Immunization Center (MOPH IC) database maintained by the Ministry of Public Health, Thailand.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted on routine data collected as part of the national COVID-19 response under the Communicable Disease ACT (B.E. 2558) and was exempted from ethics review. Data were de-identified at source and analysed by Chiang Mai Provincial Health Office and Faculty of Public Health, Chiang Mai University.

Study design

A test-negative, case-control analysis was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of heterologous three dose COVID-19 vaccine schedules for SARS-CoV-2 infection during delta-predominant period, and heterologous three dose and four dose COVID-19 vaccine schedules for SARS-CoV-2 infection during omicron-predominant period among suspect-cases. “Cases” were defined as those with a positive SARS-CoV-2 result, and “controls” were those with negative SARS-CoV-2 result, either by RT-PCR or medically administered antigen testing. The type of COVID-19 vaccine, and date of vaccination were extracted from MOPH-IC. Subjects who received their COVID-19 vaccination within 14 days of the test date were excluded to allow time for the development of adequate immune responses.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported separately for the cases and controls, stratified by delta and omicron predominance. Continuous variables were summarised as mean and SD or median and IQR depending on the distribution. Categorical variables were summarised as frequency and percentages. Between group comparisons were done using Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal Wallis test for continuous variables and Chi-squared test for categorical variables.

Associations between SARS-CoV-2 infection and heterologous vaccination schedule were estimated by comparing the odds of vaccination (exposed) vs no vaccination (unexposed) separately for delta and omicron-predominant periods. The odds ratio (OR) was used to estimate VE, where VE = (1 – OR) × 100% with 95% CI. Separate VEs were calculated for different vaccination schedules and stratified by age group. Forest plots were used to visualise the VEs. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate ORs for SARS-CoV-2 infection, adjusting for age in years, gender, calendar day of test (in weekly units), separately for delta and omicron-predominant periods. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata (version 15.0 SE, College station, TX: StataCorp LP). Significance tests were 2-sided and a p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Role of the funding source

This research was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) under The Smart Emergency Care Services Integration (SECSI) project to Faculty of Public Health Chiang Mai University. The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Population demographics

There was a total of 19,235 COVID-19 cases and 156 deaths during the delta predominant period, and 296,064 COVID-19 cases and 175 deaths during the omicron-predominant period in Chiang Mai province. For the final analysis, a total of 27,301 subjects (2130 cases and 25,171 controls) and 36,170 subjects (14,682 cases and 21,488 controls) were included during the delta and omicron-predominant periods respectively (Supplementary Figure 1a and b).

During the delta-predominant period, cases and controls were of similar ages, while during the omicron-predominant period, cases were slightly younger than controls, primarily due to a higher proportion of individuals aged 18–29 years identified as cases during this period. In both periods, subjects who received boosters were significantly older compared to those who received only one or two doses. During the omicron-predominant period, subjects who received four doses were more likely to be in 30–59 age group, while those who received three doses were more likely to be in 60–69 age group (Supplementary Table 1a and b). This is reflective of the vaccine roll out in Thailand, where individuals aged <60 years received their first doses earlier from April 2021, while those aged >60 years mostly received their first dose beginning in Jun 2021. A slightly higher proportion of females were included in both periods and overall, proportions were relatively consistent across doses with the exception of a higher proportion of males being unvaccinated during the delta-predominant period or receiving only single dose of vaccine during omicron-predominant period.

Multiple schedules of vaccines were used for the primary schedule and vaccine use varied between the two periods. Overall, controls were more likely to have received both two-dose and booster vaccinations, and cases had significantly longer median intervals since their last vaccinations during the omicron-predominant period for their second dose (117 vs 104 days), third dose (58 vs 50 days) and fourth dose (44 vs 39 days) (Table 1). Notably during the delta-predominant period, only five (0.4%) cases were reported among 1197 subjects receiving third doses (Table 2). During the omicron-predominant period, amongst 12,366 subjects with recorded third dose vaccinations, approximately 46% received BNT162b2, 35% received ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, 18% received mRNA-1273 and less than 0.5% received inactivated vaccine (Sinovac). For the 823 subjects with a recorded fourth dose in the omicron-predominant period, approx. 50% received BNT162b2, 44% received mRNA-1273 and approx. 6% received ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects included in analysis of association of vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults, during Omicron-predominant period (Feb 1–Apr 10, 2022).

| Variable | Total (N = 36,170) | SARS-CoV-2 status |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (controls) | Positive (cases) | p-value | ||

| Number (%) | 214,881 (59.4) | 14,682 (40.6) | - | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 33 (24, 46) | 35 (25, 47) | 31 (23, 44) | <0.01 |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||

| 18–29 | 14,981 (41.42) | 8107 (37.7) | 6874 (46.8) | <0.01 |

| 30–39 | 7712 (21.3) | 4732 (22.0) | 2980 (20.3) | |

| 40–49 | 6276 (17.3) | 4034 (18.7) | 2242 (15.3) | |

| 50–59 | 4125 (11.4) | 2686 (12.5) | 1439 (9.8) | |

| 60–69 | 2340 (6.5) | 1471 (6.8) | 869 (5.9) | |

| ≥70 | 736 (2.0) | 458 (2.1) | 278 (1.9) | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 16,783 (46.4) | 10,011 (46.6) | 6772 (46.1) | 0.38 |

| Female | 19,387 (53.6) | 11,477 (53.4) | 7910 (53.9) | |

| Vaccination status, n (%) | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 4610 (12.7) | 2681 (12.5) | 1929 (13.1) | <0.01 |

| Vaccinated one dose only | 470 (1.3) | 272 (1.3) | 198 (1.3) | |

| Vaccinated two doses only | 17,897 (49.5) | 9934 (46.2) | 7963 (54.2) | |

| Vaccinated three doses only | 12,369 (34.2) | 7950 (37.0) | 4419 (30.1) | |

| Vaccinated four doses | 824 (2.3) | 651 (3.0) | 173 (1.2) | |

| Type of primary vaccine series (n=17,893),an (%) | ||||

| SV/SP-AZ | 7780 (43.5) | 4464 (44.9) | 3316 (41.7) | <0.01 |

| AZ-PFZ/Mod | 3661 (20.5) | 1904 (19.2) | 1757 (22.1) | |

| SV-SV or SP-SP | 3080 (17.2) | 1713 (17.2) | 1367 (17.2) | |

| PFZ-PFZ | 2340 (13.1) | 1237 (12.5) | 1103 (13.9) | |

| Mod-Mod | 516 (2.9) | 294 (2.9) | 222 (2.8) | |

| AZ-AZ | 396 (2.2) | 249 (2.5) | 147 (1.9) | |

| SV/SP-PFZ/Mod | 120 (0.7) | 72 (0.7) | 48 (0.6) | |

| Type of third vaccine dose (n=12,366),bn (%) | ||||

| PFZ | 5700 (46.1) | 3670 (46.2) | 2030 (45.9) | 0.50 |

| AZ | 4418 (35.7) | 2874 (36.2) | 1544 (35.0) | |

| Mod | 2212 (17.9) | 1378 (17.3) | 834 (18.9) | |

| SV/SP | 36 (0.29) | 28 (0.3) | 8 (0.2) | |

| Type of fourth vaccine dose (n=823),cn (%) | ||||

| Mod | 356 (43.3) | 278 (42.7) | 78 (45.4) | 0.68 |

| PFZ | 414 (50.3) | 329 (50.5) | 85 (49.4) | |

| AZ | 53 (6.4) | 44 (6.7) | 9 (5.2) | |

| Median (IQR) time since last vaccination,ddays | 85 (53, 122) | 80 (48, 112) | 93 (61, 137) | <0.01 |

| Median (IQR) time since last vaccination (two doses only) | 110 (84, 150) | 104 (81, 140) | 117 (89, 167) | <0.01 |

| Median (IQR) time since last vaccination (three doses only) | 53 (35, 75) | 50 (32, 74) | 58 (40, 77) | <0.01 |

| Median (IQR) time since last vaccination (four doses) | 40 (26, 57) | 39 (26, 56) | 44 (27, 62) | 0.06 |

| Vaccination coverage | ||||

| Completed primary vaccine series, n (%) | 31,090 (85.9) | 18,535 (86.3) | 12,555 (85.5) | 0.04 |

| Completed third vaccine dose, n (%) | 13,193 (36.5) | 8601 (40.0) | 4592 (31.3) | <0.01 |

| Completed fourth vaccine dose, n (%) | 824 (2.3) | 651 (3.0) | 173 (1.2) | <0.01 |

SV = CoronaVac (Sinovac), SP = Sinopharm, AZ = ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca), PFZ = BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech), Mod = mRNA-1273 (Moderna).

Vaccine type missing in 4 (0.02%).

Vaccine type missing in 3 (0.02%), 36 subjects received homologous vaccine schedules, 2 with BNT162b228 three dose, 6 with ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 three doses, 28 with CoronaVac three doses.

Vaccine type missing in 1 (0.12%).

Among 31,299 who received at least 1 dose and dates of vaccination available.

Table 2.

Characteristics of subjects included in analysis of association of vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults, during delta-predominant period (Oct 1–Dec 31, 2021).

| Variable | Total (N = 27,301) | SARS-CoV-2 status |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (controls) | Positive (cases) | p-value | ||

| Number (%) | 25,171 (92.2) | 2130 (7.8) | - | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 37 (28, 49) | 37 (28, 49) | 37 (26, 50) | 0.36 |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||

| 18–29 | 8202 (30.0) | 7491 (29.7) | 711 (33.4) | <0.01 |

| 30–39 | 7147 (26.2) | 6667 (26.5) | 480 (22.5) | |

| 40–49 | 5334 (19.5) | 4948 (19.7) | 386 (18.1) | |

| 50–59 | 3707 (13.6) | 3465 (13.8) | 242 (11.4) | |

| 60–69 | 2097 (7.7) | 1905 (7.6) | 192 (9.0) | |

| ≥70 | 814 (2.9) | 695 (2.7) | 119 (5.6) | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 12,745 (46.7) | 11,693 (46.5) | 1052 (49.4) | <0.01 |

| Female | 14,556 (53.3) | 13,478 (53.6) | 1078 (50.6) | |

| Vaccination status, n (%) | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 9697 (35.5) | 8570 (34.0) | 1127 (52.9) | <0.01 |

| Vaccinated one dose only | 3360 (12.3) | 3001 (11.9) | 359 (16.9) | |

| Vaccinated two doses only | 13,045 (47.8) | 12,406 (49.3) | 639 (30.0) | |

| Vaccinated three doses | 1199 (4.4) | 1194 (4.7) | 5 (0.2) | |

| Type of primary vaccine series (n = 13,045), n (%) | ||||

| SV/SP-AZ | 6609 (50.7) | 6333 (51.1) | 276 (43.2) | NA |

| SV-SV or SP-SP | 4770 (36.6) | 4485 (36.1) | 285 (44.6) | |

| AZ-AZ | 1326 (10.2) | 1251 (10.1) | 75 (11.7) | |

| PFZ-PFZ | 194 (1.5) | 191 (1.5) | 3 (0.5) | |

| AZ-PFZ/Mod | 133 (1.0) | 133 (1.1) | 0 | |

| SV/SP-PFZ/Mod | 11 (0.1) | 11 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Mod–Mod | 2 (0.02) | 2 (0.02) | 0 | |

| Type of third vaccine dose (n = 1197),an (%) | ||||

| PFZ | 210 (17.6) | 210 (17.6) | 0 | 0.40 |

| AZ | 879 (73.4) | 874 (73.3) | 5 (100) | |

| Mod | 108 (9.0) | 108 (9.1) | 0 | |

| Median (IQR) time since last vaccination,bdays | 53 (28, 84) | 53 (28, 84) | 48 (29, 79) | 0.22 |

| Median (IQR) time since last vaccination (two doses only)c | 53 (32, 79) | 53 (32, 79) | 49 (30, 74) | 0.35 |

| Vaccination coverage | ||||

| Completed primary vaccine series, n (%) | 14,244 (52.2) | 13,600 (54.0) | 644 (30.2) | <0.01 |

| Completed third vaccine dose, n (%) | 1199 (4.4) | 1194 (4.7) | 5 (0.2) | <0.01 |

SV = CoronaVac (Sinovac), SP = Sinopharm, AZ = ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca), PFZ = BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech), Mod = mRNA-1273 (Moderna).

Vaccine type missing in 2 (0.02%).

Date of last vaccination missing in 258 (1.5%).

Date of last vaccination missing in 96 (0.7%).

Vaccine effectiveness

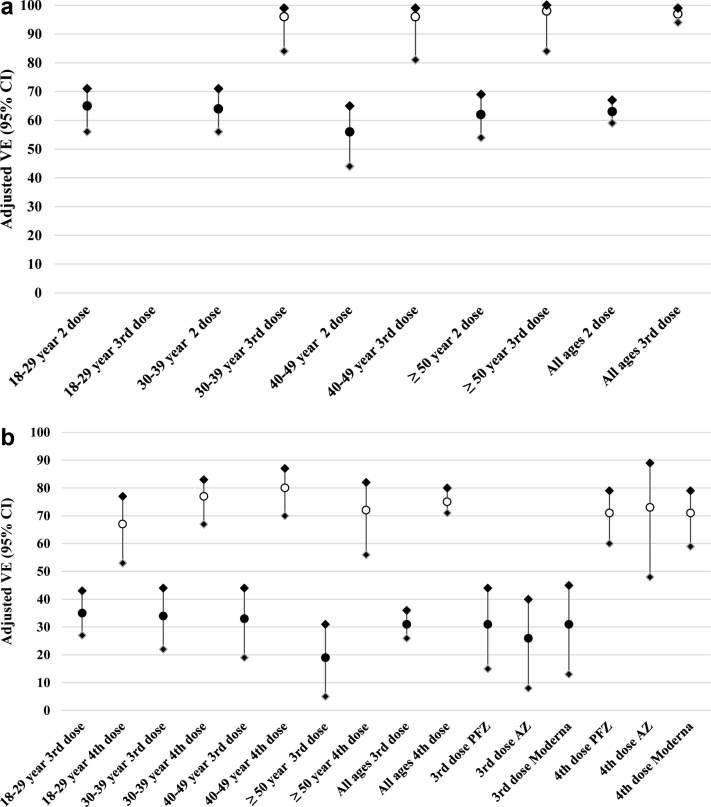

Majority (99.7%) of the boosted subjects received heterologous vaccine schedules. Effectiveness against delta infection was minimal after receiving only a single dose of vaccine. After adjusting for age, gender and calendar week of test, a two-dose primary vaccine series had a VE of 63% (95% CI 59–67%) against delta while a third dose increased the VE to 97% (95% CI 94–99%) (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 2a). The VE against delta was consistent across different age groups for either two or three doses (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a: Effectiveness of two (•) and three (○) dose vaccination regimens against SARS-CoV-2 infection during delta-predominant period (Oct 1–Dec 31, 2021). ∗Age stratified vaccine effectiveness (VE) adjusted for gender and calendar time. b: Effectiveness of three (•) and four (○) dose vaccination regimens against SARS-CoV-2 infection during Omicron-predominant period (Feb 1–Apr 10, 2022). AZ = ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca), PFZ = BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech), Moderna = mRNA-1273 (Moderna), VE = vaccine effectiveness. ∗Age stratified VE adjusted for gender and calendar time. ∗VE by vaccine type adjusted for age, gender, calendar time and preceding vaccine series type.

During the omicron-predominant period, one or two doses of vaccine provided little to no protection against omicron infection while adjusted VE for a three dose vaccine series was 31% (95% CI 26–36%) and a four dose vaccine series was 75% (95% CI 71–80%) (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 2b). Three or four dose VE against omicron was consistent across age group 18–50 years but limited case numbers prevented accurate assessment of older ages.

Due to the very small numbers of cases observed, it was possible to calculate only the VE for the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine as a third dose in the delta-predominant period with an adjusted VE of 93% (95% CI 82–97) against infection (delta variant). During the omicron-predominant period, adjusted VE for the effectiveness of the third dose did not differ significantly by type of vaccine for the three main vaccines used in Chiang Mai (26–31%) (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 2b). Similarly, adjusted VE for the effectiveness of the fourth dose also did not differ significantly by type of vaccine (71–73%) (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 2b).

Discussion

While the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths globally is unacceptably high, the impact of vaccinations is undisputable, when implemented appropriately. As vaccination schedules have rapidly evolved to third and fourth doses, to manage new variants and concerns around waning immunity, the availability of data to support decision makers has struggled to keep pace. The current study provides urgently needed evidence to support the continued rollout booster schedules in Thailand and Asia, and for the first time provides VE for fourth dose schedules incorporating inactivated vaccines into the primary series. Our results corroborate with findings that VE against infection for omicron variant is consistently lower than VE against the delta variant.19,21 Heterologous booster vaccines elicit a stronger immune response, but like homologous regimes, antibodies decay over time.22,23 From a local context, our findings are consistent with a recent study conducted in Bangkok (Thailand) by Sritipsukho and colleagues evaluating the three dose schedules against the delta variant.24 In that study, the adjusted VE among individuals who received two and three doses of the vaccines was 65% (95% CI 56–72), and 91% (95% CI 84–95), respectively during the delta-predominant period, which is in agreement with the results of the current study: 63% (two doses) and 97% (three doses).

Previous studies have demonstrated little to no protection against omicron infection for two doses and only mild protection against severe outcomes.21 We also observed minimal protection against omicron infection after one or two doses. We see moderate protection against omicron infection after a third dose (30–40%) and good protection (>70%) after a fourth dose. Recent studies have reported lower hospitalization rates and severe COVID-19 related outcomes due to the omicron variant,25,26 this could partly be due to T-cell response which underpin good protection against severe infection and death, irrespective of newer variants of concern.27

The VE of third or fourth vaccine doses against omicron infection were equivalent for the three main vaccines used for boosting in Thailand. Although we were unable to compare VE of third dose against delta by vaccine type, the study by Sritipsukho and colleagues, found comparable protection from a third dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and BNT162b2.24 The equivalent VE observed for the main booster vaccines used in Thailand is consistent with a recent global analysis of VE data demonstrating equivalence of mRNA and vector vaccines as two dose schedules against earlier variants of concern.13 This strongly suggests that accelerating booster vaccinations and increasing coverage by using any vaccines available, particularly among those aged 60 and older or those with co-morbidities is a valid strategy.

The current study has few limitations. The subjects included in the study were those meeting suspect-case definition and hence, those tested due to epidemiological linkages may or may not have presented with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19. Therefore, the results may not be completely generalisable to those who are symptomatic. In addition to age, gender and calendar time, other key baseline confounders such as chronic comorbidities, socioeconomic status, and prior COVID-19 infection were not examined in this analysis. Due to the variations in the vaccine roll-out, the current study did not differentiate between vaccine eligible population, as compared to those who received recent vaccination and are not yet eligible for next vaccination.

The strengths of the study include the use of harmonised databases with complete record capture for vaccination status. The community-based testing sites provided facilities for people who stayed in the city and surrounding districts where around 40–50% of the COVID-19 cases were reported and is therefore largely representative of the resident population.

The current study provides important findings to support the administration of additional doses of COVID-19 vaccines. Despite the high effectiveness observed for all vaccine booster schedules evaluated, coverage rates in Thailand and in most of the world, are much lower than needed, particularly among the elderly and higher risk segments of the population. Maintaining high vaccination coverage is important in the face of new variants of concern and waning immunity over time. As the pandemic evolves and COVID-19 is eventually declared an endemic disease complacency will likely increase and it may be difficult for governments to continue to support a strong emphasis on preventative measures. As a result, having a high coverage of third booster vaccinations is projected to play a crucial role in decreasing mortality. Our data supports the use of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 as booster vaccines, providing much needed flexibility to incorporate different vaccines into schedules according to local supply and logistical considerations.

Contributors

KI, SC, KC, TW, WK, AT, NC, WT, PK, JW, and SI conceptualised the study. SC, KI, and AT led the literature review. KI, SC, KC, TW, WK, AT, NC, WT, PK, JW, and SI contributed towards the methodology. KI did the analysis with the support from SC. SC, KI, and AT wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript. All the authors contributed to data collection, curation, validation, and data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. KI, SC, and AT had full access of all data in the study. KI and SC contributed equally as joint first authors.

Data sharing statement

All relevant data is available in the paper. Additional requirements, if any will be welcome and de-identified dataset and related codes for analysis will be made available to researchers on request after publication. Requests for data should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Declaration of interests

None.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) under The Smart Emergency Care Services Integration (SECSI) project to Faculty of Public Health Chiang Mai University. We are grateful to the Chiang Mai Provincial Health Office and the Department of Disease Control Ministry of Public Health for the collaborative partnerships in managing health information of COVID-19 epidemic.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2022.100121.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Mathieu E., Ritchie H., Rodés-Guirao L., et al. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Available online at:

- 2.Richards F., Kodjamanova P., Chen X., et al. Economic burden of COVID-19: a systematic review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2022;14:293–307. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S338225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaye A.D., Okeagu C.N., Pham A.D., et al. Economic impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare facilities and systems: international perspectives. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2021;35(3):293–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2020.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doroshenko A. The combined effect of vaccination and nonpharmaceutical public health interventions-ending the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore S., Hill E.M., Tildesley M.J., Dyson L., Keeling M.J. Vaccination and non-pharmaceutical interventions for COVID-19: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(6):793–802. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO COVID-19 dashboard. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2022. https://covid19.who.int/ Available online at: [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO COVID-19 vaccines. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2022. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines Available online at: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thailand Food and Drug Administration: Medicines Regulation Division. 2022. https://www.fda.moph.go.th/sites/drug/SitePages/Vaccine_SPC-Name.aspx Available online at:

- 9.Thailand Department of Disease Control. https://ddc.moph.go.th/vaccine-covid19/diaryPresentMonth/06/10/2022 Available online at:

- 10.Palacios R., Patiño E.G., de Oliveira Piorelli R., et al. Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of treating healthcare professionals with the adsorbed COVID-19 (inactivated) vaccine manufactured by Sinovac - PROFISCOV: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):853. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04775-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voysey M., Clemens S.A.C., Madhi S.A., et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397(10269):99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chuenkitmongkol S., Solante R., Burhan E., et al. Expert review on global real-world vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21(9):1255–1268. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2022.2092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atmar R.L., Lyke K.E., Deming M.E., et al. Homologous and heterologous Covid-19 booster vaccinations. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(11):1046–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barros-Martins J., Hammerschmidt S.I., Cossmann A., et al. Immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 variants after heterologous and homologous ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/BNT162b2 vaccination. Nat Med. 2021;27(9):1525–1529. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01449-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X., Shaw R.H., Stuart A.S.V., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of heterologous versus homologous prime-boost schedules with an adenoviral vectored and mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Com-COV): a single-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10303):856–869. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01694-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borobia A.M., Carcas A.J., Pérez-Olmeda M., et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of BNT162b2 booster in ChAdOx1-S-primed participants (CombiVacS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10295):121–130. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01420-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayr F.B., Talisa V.B., Shaikh O., Yende S., Butt A.A. Effectiveness of homologous or heterologous Covid-19 boosters in veterans. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(14):1375–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2200415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Accorsi E.K., Britton A., Shang N., et al. Effectiveness of homologous and heterologous Covid-19 boosters against omicron. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(25):2433–2435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2203165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Intawong K., Olson D., Chariyalertsak S. Application technology to fight the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned in Thailand. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;538:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.01.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UK Health Security Agency COVID-19 vaccine surveillance report. Week 24. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-vaccine-weekly-surveillance-reports.

- 22.Ascaso-Del-Rio A., García-Pérez J., Pérez-Olmeda M., et al. Immune response and reactogenicity after immunization with two-doses of an experimental COVID-19 vaccine (CVnCOV) followed by a third-fourth shot with a standard mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2): RescueVacs multicenter cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;51 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.García-Pérez J., González-Pérez M., Castillo de la Osa M., et al. Immunogenic dynamics and SARS-CoV-2 variant neutralisation of the heterologous ChAdOx1-S/BNT162b2 vaccination: secondary analysis of the randomised CombiVacS study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;50 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sritipsukho P., Khawcharoenporn T., Siribumrungwong B., et al. Comparing real-life effectiveness of various COVID-19 vaccine regimens during the delta variant-dominant pandemic: a test-negative case-control study. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11(1):585–592. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2037398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veneti L., Bøås H., Bråthen Kristoffersen A., et al. Reduced risk of hospitalisation among reported COVID-19 cases infected with the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 variant compared with the Delta variant, Norway, December 2021 to January 2022. Euro Surveill. 2022;27(4) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.4.2200077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyberg T., Ferguson N.M., Nash S.G., et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022;399(10332):1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00462-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moss P. The T cell immune response against SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol. 2022;23(2):186–193. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01122-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.