Abstract

Health promotion and disease prevention (P&P) are essential components of primary health care. This study investigated the coverage of P&P services and barriers to services among primary care units in Thailand before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. A web-based cross-sectional survey was conducted to compare the data from primary care units across the 13 health regions in two fiscal years: October 2018 to September 2019 (before the pandemic) and October 2019 to September 2020 (during the pandemic). A total of 340 primary care units responded to the questionnaire. While most participating primary care units provided basic P&P services (n = 327, 96.2%) and community-based P&P services (n = 244, 71.8%), fewer offered area-based P&P services (n = 120, 35.3%) for all target populations. The high coverage of basic P&P services remained in place during the pandemic, while coverage of community-based P&P services for vulnerable and at-risk populations improved during the pandemic. Area-based P&P services improved for pregnant and postpartum women, preschoolers, children and adolescents, adults, and older people. Lack of human resources, materials and equipment, and financial support were cited as the primary challenges to offering P&P services. The higher coverage of P&P services in several target populations during the pandemic contributed to a heavy workload. Effective resource allocation, capacity building, and support from relevant parties, such as government and local agencies, are required to maintain high P&P service coverage.

Keywords: COVID-19, Disease prevention, Health promotion, Health services, Primary health care

COVID-19; Disease prevention; Health promotion; Health services; Primary health care.

1. Introduction

The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (1986) defined health promotion as “the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health” [1]. The following five goals for health promotion are identified: 1) build healthy public policy, 2) create a supportive environment for health, 3) strengthen community action, 4) develop personal skills, and 5) reorient health services [2, 1]. The 2018 Astana Declaration stated primary health care (PHC) is a cornerstone of a sustainable health system that provides universal health coverage and empowers individuals and communities [3, 4]. PHC represents the first contact with individuals and families in a community-oriented health system [5, 6, 7]. Good health and well-being is a key component of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [8]. PHC has a vital function to provide equal access to quality health care services [9, 10]. This concept is supported by the World Health Organization’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development of universal health coverage and health equity, especially in low- and middle-income countries [11, 12, 13, 14].

In Thailand, PHC exists in primary care units within several settings including subdistrict health-promoting hospitals, community health centers, community medical units, and municipal-affiliated health care centers [10]. The integrated and comprehensive services provided in PHC settings include health promotion, disease prevention, curative care, rehabilitative care, and palliative care [10, 11]. Health promotion and disease prevention (P&P) are important public health services according to the Thailand Ministry of Public Health’s motto, “take health promotion first, get health repairing later” [15]. Thailand has been striving for national universal health coverage since 2002 [16]. P&P services across age groups are subsidized by Thailand’s national health insurance system. The main objective of P&P is to reduce individual health-risk factors, morbidity, and mortality, and lower the overall disease burden [17]. P&P services provided by primary care units in Thailand include: 1) services for each age group according to the national public health guidelines (basic P&P), 2) policy-based services specific to the context and needs of each geographic area (area-based P&P), and 3) community-based services focused on the health of people at the community level rather than the individual level (community-based P&P).

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic contributes to a huge impact on health systems and the provision of P&P services [18, 19, 20]. In addition, the effects on the health system and individual lives (e.g., a reduction in non-urgent services, COVID-19-related personal health recommendations, travel restrictions) have altered P&P service capacity. This raised an important question according to the changes in P&P services at the national level due to the COVID-19 pandemic. To gain a better understanding and fill this knowledge gap, this study aimed to investigate the coverage of P&P services and barriers to services among primary care units in Thailand during fiscal years 2019 (before COVID-19 pandemic) and 2020 (during COVID-19 pandemic).

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted between December 2020 and April 2021. The online questionnaire was used to collect data of fiscal years 2019 (October 2018 to September 2019) and 2020 (October 2019 to September 2020). The target population for the survey was 10,925 primary care units in 77 provinces representing all 13 health regions of Thailand. An in-charge staff for P&P at each primary care unit was invited to participate in the study. Primary care units that were not listed in the national database during fiscal years 2019 and 2020 were excluded.

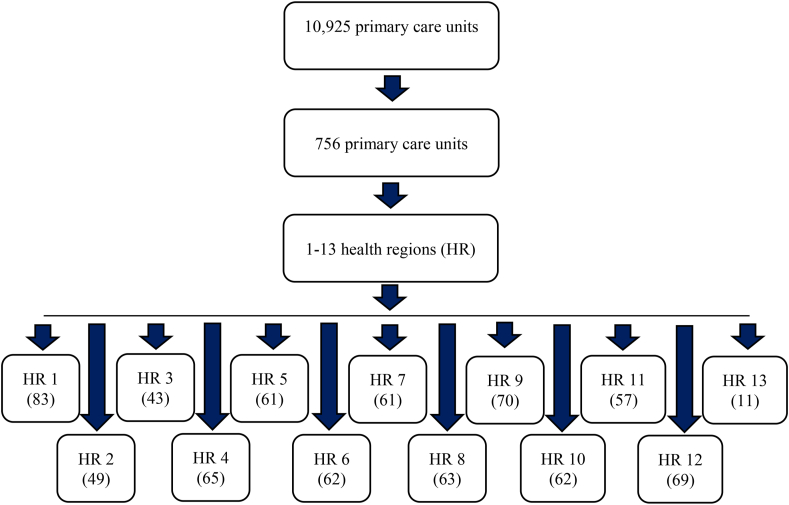

The sample size was calculated with the sample size calculator program called n4Studies, using a function for estimating a finite population proportion [21]. The values of proportion = 0.5, error = 0.05, and alpha = 0.1 were applied [21]. The sample size was calculated as 626, and after adding 20% to compensate for non-respondents, 756 was defined as the target sample of primary care units [22, 23]. A multistage sampling approach was conducted by classifying the primary strata (health region) into 13 regions and weighting the number of primary care units in each region (Figure 1). The sample size of each province was determined as proportional to the number of primary care units in the province.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the sample size.

2.2. Data collection

Printed invitation letters with a link and a QR code for accessing the online questionnaire on Google Form were sent to the target primary care units. The regional coordinators followed up with each primary care unit after 2–4 weeks by phone and email. A second reminder was made by phone and email 2 weeks after the first reminder. Primary care units that did not respond to the questionnaire after the second reminder were defined as non-respondents. Data were collected between February 1, 2021, and April 30, 2021.

The questionnaire was developed by the research team based on characteristics of primary care units in the Thai context and the literature on the Thai health insurance schemes and the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion [1, 24]. Subsequently, public health academics and workers from different health regions reviewed and provided comments on the questionnaire (content validity). Several rounds of reviews and revisions were made. The questionnaire was piloted by three PHC providers from non-participating primary care units for wording and content appropriateness (face validity). Minor issues were addressed to finalize the questionnaire. The questionnaire included four sections (Supplementary file 1).

Section 1primary care unit demographics included general information about the primary care units: 1.1) type of primary care units (i.e., municipal-affiliated health care center, health-promoting hospital, other), 1.2) affiliations (name of the Ministry), and locations (health region, province, and district).

Section 2P&P service characteristics included 2.1) coverage of each target population during fiscal years 2019 and 2020 for area-based P&P (ten target populations), basic P&P (five target populations), and community-based P&P (eight target populations). The service coverage of each target population was labeled as “very low” (0–25% of the target population), “low” (26–50% of the target population), “moderate” (51–75% of the target population), or “high” (76–100% of the target population). The rest of questions in section 2 were collected: 2.2) names of relevant agencies for each target population, 2.3) levels of participation for each target population (score ranged from 1 (low) to 4 (high)), and 2.4) challenges for each target group. The data obtained from 2.2 and 2.3 were context-specific and reported in a Thai version of full research report (Supplementary file 2).

Section 3P&P service processes consisted of the questions with regard to 3.1) building healthy public policies (i.e., availability in fiscal years 2019 and 2020 (yes/no), patterns (multiple options that commonly established in Thailand and a space for other options), names of financial sources (multiple options and a space for other options)); 3.2) strengthening the community (i.e., availability in fiscal years 2019 and 2020 (yes/no), target populations (village health volunteers, community leaders, youth, elderly, other), patterns (multiple options that commonly established in Thailand and a space for other options), names of financial sources (multiple options and a space for other options)); and 3.3) developing personal skills (i.e., availability in fiscal years 2019 and 2020 (yes/no), target populations (village health volunteers, community leaders, youth, elderly, other), target skills (self-care, health literacy, public policy implementation, other), methods (frequency of activities), names of financial sources (multiple options and a space for other options)). The data collected from section 3 were context-specific and reported in a Thai version of research report (Supplementary file 2).

Section 4P&P service comments and needs were open-ended questions as qualitative data: 4.1) comments on P&P services in fiscal years 2019 and 2020 and 4.2) recommendations on P&P services for primary care units.

2.3. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as frequencies and percentages for the following variables: health region, geographic region, coverage of area-based P&P, basic P&P, and community-based P&P, and performance coverage in each target population. Chi-square test was used to investigate the differences between area-based, basic, and community-based P&P services during fiscal years 2019 (before COVID-19 pandemic) and 2020 (during COVID-19 pandemic). All analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 4.0.5) [25]. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The qualitative data obtained from the open-ended data were grouped into themes and the frequencies were counted.

2.4. Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Walailak University (Project No. WU-EC-MD-3-001-64). All respondents provided informed consent at the beginning of the online questionnaire by selecting a checkbox to confirm their willingness to participate in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Participating primary care units

Of 756 invitations, 340 questionnaires were received (45.0% response rate). The highest response rate was in the health region 1 (97.6%), followed by the health region 4 (92.3%) and the health region 2 (83.7%). The majority of the respondents were in the northern region (81.1%) (Table 1). The majority of participating primary care units were under the Ministry of Public Health (n = 323, 95.0%), followed by the Ministry of Interior (n = 10, 2.9%), the Ministry of Justice (n = 4, 1.2%), and the Ministry of Education/the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation (n = 3, 0.9%). Most participants were categorized into subdistrict health-promoting hospitals (n = 307, 90.3%), primary care units affiliated with public hospitals (n = 16, 4.7%), municipal-affiliated health care centers (n = 11, 3.2%), and others (n = 6, 1.8%).

Table 1.

Distribution of respondents by health region and regional area of Thailand.

| General information | Sample size | Respondent (n) | Response rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health region | |||

| Health region 1 | 83 | 81 | 97.6 |

| Health region 2 | 49 | 41 | 83.7 |

| Health region 3 | 43 | 20 | 46.5 |

| Health region 4 | 65 | 60 | 92.3 |

| Health region 5 | 61 | 27 | 44.3 |

| Health region 6 | 62 | 12 | 19.4 |

| Health region 7 | 61 | 21 | 34.4 |

| Health region 8 | 63 | 5 | 7.9 |

| Health region 9 | 70 | 11 | 15.7 |

| Health region 10 | 62 | 12 | 19.4 |

| Health region 11 | 57 | 17 | 29.8 |

| Health region 12 | 69 | 30 | 43.5 |

| Health region 13 | 10 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Region of Thailand | |||

| Northern | 175 | 142 | 81.1 |

| Central | 198 | 102 | 51.5 |

| Southern | 126 | 47 | 37.3 |

| Northeastern | 256 | 49 | 19.1 |

3.2. Health promotion and disease prevention services

Most participating primary care units provided basic P&P services for all target populations (n = 327, 96.2%). A total of 244 primary care units (71.8%) provided community-based P&P services, while 120 (35.3%) provided area-based P&P services for all target populations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency and percentage of health promotion and disease prevention services.

| Services | Number (N = 340) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Area-based P&P (10 target populations) | ||

| Cover all target populations | 120 | 35.3 |

| Cover some target populations | 104 | 30.6 |

| No activities | 116 | 34.1 |

| Basic P&P (5 target populations) | ||

| Cover all target populations | 327 | 96.2 |

| Cover some target populations | 8 | 2.4 |

| No activities | 5 | 1.5 |

| Community-based P&P (8 target populations) | ||

| Cover all target populations | 244 | 71.8 |

| Cover some target populations | 74 | 21.8 |

| No activities | 22 | 6.4 |

3.3. Coverage of P&P services during fiscal years 2019 (before COVID-19 pandemic) and 2020 (during COVID-19 pandemic)

3.3.1. Coverage of area-based P&P services

The majority of primary care units rated their coverage of area-based P&P for all target populations at moderate to high. The number of primary care units that rated their services as high coverage increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic for pregnant and postpartum women, preschoolers, children and adolescents, adults, and the elderly (Table 3).

Table 3.

Coverage of area-based P&P services during fiscal years 2019 and 2020.

| Target group | 2019 (Before COVID-19 pandemic) |

2020 (During COVID-19 pandemic) |

Goodness of fit |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) |

n (%) |

|||||||||||

| High | Moderate | Low | Very low | Total | High | Moderate | Low | Very low | Total | Chi-square | P-Value | |

|

150 (68.2) | 53 (24.1) | 8 (3.6) | 9 (4.1) | 220 (100) | 171 (78.1) | 34 (15.5) | 8 (3.7) | 6 (2.4) | 219 (100) | 10.80 | 0.01∗ |

|

163 (73.4) | 47 (21.2) | 7 (3.2) | 5 (2.3) | 222 (100) | 178 (80.9) | 35 (15.9) | 4 (1.8) | 3 (1.4) | 220 (100) | 6.57 | 0.04∗ |

|

133 (59.6) | 75 (33.6) | 13 (5.8) | 2 (0.9) | 223 (100) | 150 (67.9) | 61 (27.6) | 6 (2.7) | 4 (1.8) | 221 (100) | 6.49 | 0.04∗ |

|

148 (66.7) | 61 (27.5) | 11 (5.0) | 2 (0.9) | 222 (100) | 164 (74.2) | 50 (22.6) | 6 (2.7) | 1 (0.5) | 221 (100) | 6.51 | 0.04∗ |

|

169 (76.5) | 42 (19.0) | 8 (3.6) | 2 (0.9) | 221 (100) | 184 (84.8) | 30 (13.8) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) | 217 (100) | 9.76 | 0.01∗ |

|

43 (35.8) | 22 (18.3) | 13 (10.8) | 42 (35.0) | 120 (100) | 47 (39.5) | 19 (16.0) | 15 (12.6) | 38 (31.9) | 119 (100) | 1.47 | 0.69 |

|

155 (69.8) | 55 (24.8) | 8 (3.6) | 4 (1.8) | 222 (100) | 162 (74.0) | 43 (19.6) | 10 (4.6) | 4 (1.8) | 219 (100) | 3.27 | 0.19 |

|

128 (57.9) | 65 (29.4) | 20 (9.0) | 8 (3.6) | 221 (100) | 139 (64.1) | 52 (24.0) | 15 (6.9) | 11 (5.1) | 217 (100) | 5.96 | 0.11 |

|

81 (42.2) | 56 (29.2) | 28 (14.6) | 27 (14.1) | 192 (100) | 86 (46.2) | 49 (26.3) | 27 (14.5) | 24 (12.9) | 186 (100) | 1.41 | 0.70 |

|

60 (41.1) | 27 (18.5) | 19 (13.0) | 40 (27.4) | 146 (100) | 58 (41.4) | 25 (17.9) | 19 (13.6) | 38 (27.1) | 140 (100) | 0.07 | 0.99 |

P-value <0.05.

3.3.2. Coverage of basic P&P services

More than 90% of primary care units rated the coverage of their basic P&P services as moderate to high during both fiscal years. The coverage was not statistically different before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 4).

Table 4.

Coverage of basic P&P services during fiscal years 2019 and 2020.

| Target group | 2019 (Before COVID-19 pandemic) |

2020 (During COVID-19 pandemic) |

Goodness of fit |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) |

n (%) |

|||||||||||

| High | Moderate | Low | Very low | Total | High | Moderate | Low | Very low | Total | Chi-square | P-Value | |

|

242 (72.7) | 66 (19.8) | 16 (4.8) | 9 (2.7) | 333 (100) | 254 (76.3) | 57 (17.1) | 14 (4.2) | 8 (2.4) | 333 (100) | 2.18 | 0.53 |

|

272 (81.7) | 51 (15.3) | 9 (2.7) | 1 (0.3) | 333 (100) | 286 (85.9) | 36 (10.8) | 10 (3.0) | 1 (0.3) | 333 (100) | 5.23 | 0.07 |

|

229 (68.6) | 93 (27.8) | 10 (3.0) | 2 (0.6) | 334 (100) | 236 (70.7) | 86 (25.7) | 10 (3.0) | 2 (0.6) | 334 (100) | 0.74 | 0.69 |

|

246 (73.7) | 75 (22.5) | 12 (3.6) | 1 (0.3) | 334 (100) | 246 (73.9) | 75 (22.5) | 11 (3.3) | 1 (0.3) | 333 (100) | 0.07 | 0.96 |

|

280 (84.3) | 46 (13.9) | 5 (1.5) | 1 (0.3) | 332 (100) | 277 (83.2) | 49 (14.7) | 6 (1.8) | 1 (0.3) | 333 (100) | 0.39 | 0.82 |

3.3.3. Coverage of community-based P&P services

Community-based P&P services provide care for the elderly, people with disabilities, and mothers and children. There was significantly higher service coverage for at-risk and vulnerable people during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 5).

Table 5.

Coverage of community-based P&P services in fiscal years 2019 and 2020.

| Target group | 2019 (Before COVID-19 pandemic) |

2020 (During COVID-19 pandemic) |

Goodness of fit |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) |

n (%) |

|||||||||||

| High | Moderate | Low | Very low | Total | High | Moderate | Low | Very low | Total | Chi-square | P-Value | |

|

226 (72.2) | 71 (22.7 | 9 (2.9) | 7 (2.2) | 313 (100) | 229 (72.9) | 70 (22.3) | 16 (1.9) | 9 (2.9) | 314 (100) | 1.62 | 0.66 |

|

196 (62.2) | 88 (27.9) | 23 (7.3) | 8 (2.5) | 315 (100) | 198 (63.3) | 91 (29.1) | 15 (4.8) | 9 (2.9) | 313 (100) | 3.04 | 0.39 |

|

244 (77.2) | 67 (21.2) | 50 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 316 (100) | 256 (81.0) | 54 (17.1) | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.3) | 316 (100) | 3.31 | 0.19 |

|

226 (71.7) | 74 (23.5) | 12 (3.8) | 3 (1.0) | 315 (100) | 236 (75.4) | 64 (20.4) | 8 (2.6) | 5 (1.6) | 313 (100) | 2.06 | 0.36 |

|

126 (46.7) | 68 (25.2) | 52 (19.3) | 24 (8.9) | 270 (100) | 131 (49.6) | 71 (26.9) | 39 (14.8) | 23 (8.7) | 264 (100) | 3.57 | 0.31 |

|

92 (37.4) | 58 (23.6) | 42 (17.1) | 54 (22.0) | 246 (100) | 105 (43.0) | 58 (23.8) | 41 (16.8) | 40 (16.4) | 244 (100) | 5.52 | 0.14 |

|

192 (61.7) | 92 (29.6) | 20 (6.4) | 7 (2.3) | 311 (100) | 207 (67.4) | 70 (22.8) | 18 (5.9) | 12 (3.9) | 307 (100) | 10.28 | 0.02∗ |

|

161 (53.5) | 87 (28.9) | 28 (9.3) | 25 (8.3) | 301 (100) | 179 (60.5) | 68 (23.0) | 22 (7.4) | 27 (9.1) | 296 (100) | 26.15 | 0.01∗ |

P-value < 0.05.

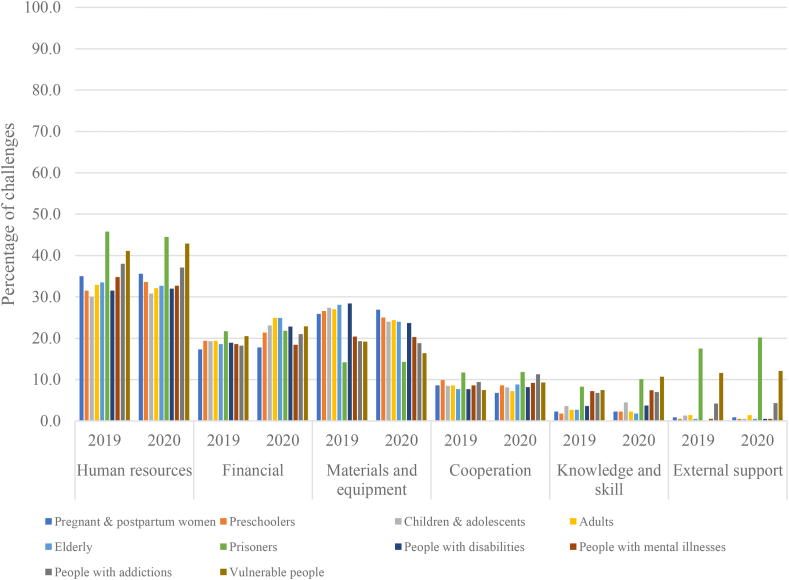

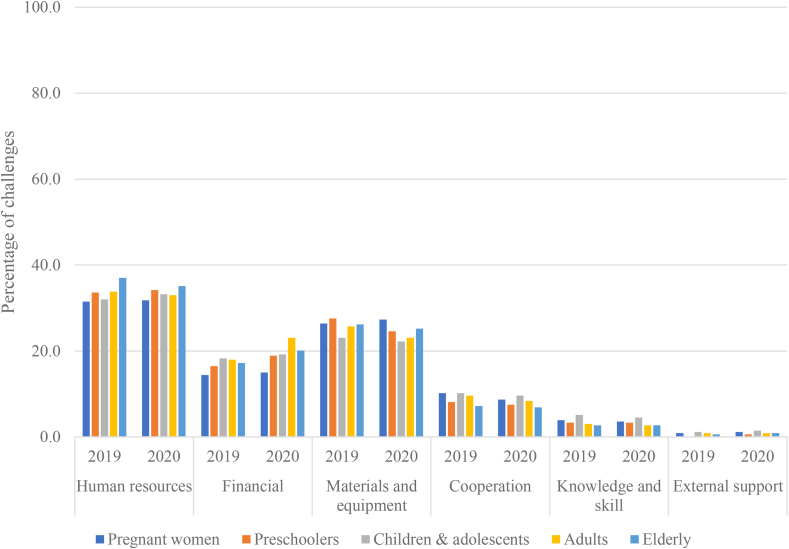

3.4. Challenges of providing P&P services

Figures 2, 3 and 4 demonstrate the comparisons of common challenges of P&P services between the fiscal years 2019 and 2020. The different colors of the bar charts represent the challenges among different target populations. The primary challenges for area-based P&P services (Figure 2), basic P&P services (Figure 3), and community-based P&P services (Figure 4) were limited human resources, materials and equipment, and financial support. Approximately 30% of primary care units experienced human resource challenges.

Figure 2.

Challenges of providing area-based P&P services.

Figure 3.

Challenges of providing basic P&P services.

Figure 4.

Challenges of providing community-based P&P services.

3.5. Needs for improving P&P services

The needs for improving P&P services identified from the qualitative data were classified into three themes: 1) resource allocation, 2) capacity building, and 3) support (Figure 5). Financial support (49 responses) was the most cited need for resource allocation. Service management (49 responses) was the most commonly cited need for capacity building. Cooperation between internal and external organizations (21 responses) was considered the most important element required to support P&P services.

Figure 5.

Needs for developing P&P services.

4. Discussion

The majority of primary care units across Thailand provided basic P&P services for pregnant women, preschoolers, children and adolescents, adults, and the elderly. The priority of community-based P&P services was to improve health at a community level. Primary care units were less responsible for area-based P&P services that were led by top-down policies. The high coverage of basic P&P services remained in place during the COVID-19 pandemic. The community-based P&P service coverage for at-risk and vulnerable people improved during the COVID-19 pandemic. The coverage of area-based P&P services was higher for pregnant and postpartum women, preschoolers, children and adolescents, adults, and the elderly. Limited human resources, materials and equipment, and financial support were all cited as challenges of providing P&P services.

The coverage of basic P&P services was high in both fiscal years (before and during the COVID-19 pandemic). This could be explained by the functionality of the universal health coverage scheme which has been implemented since 2002 [16, 26]. Basic P&P services are aimed at healthy individuals across all age groups. These services are the routine work of primary care units according to the Ministry of Public Health’s health promotion actions [11, 27]. The COVID-19 pandemic did not have a high impact on this level of P&P services.

Primary care units had the authority to drive the direction of community-based P&P services depending on the needs of their communities. While the overall coverage of P&P services increased across all eight target populations, coverage of community-based services for at-risk and vulnerable people increased significantly during the pandemic. These findings reflected a need to provide community P&P services in populations that were susceptible to COVID-19 [28, 29]. Increased coverage rates in other minority populations, including people with disabilities, people with addiction, and illegal migrants, were also found, but these changes were not statistically significant.

Differences in the coverage of area-based P&P services before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were observed. Significant increases in service coverage were found in pregnant and postpartum women, preschoolers, children and adolescents, adults, and the elderly. These target groups composed the majority of the population. The national policies for controlling COVID-19 and promoting health in the population might lead to a higher coverage in the majority population rather than in other minority groups (e.g., prisoners, people with disabilities, people with mental illnesses, people with addictions, and vulnerable people).

4.1. Implication

P&P services are a vital component of PHC. While basic P&P services were remained during the pandemic, the coverage of community-based and area-based P&P services were improved. Increasing service coverage without additional support resulted in a heavy workload for primary care units. To compensate for the imbalance, sufficient human resources were needed to serve P&P during the pandemic [30, 31, 32]. Insufficient funding was another important issue for P&P service provision [33]. Adequate materials and equipment, such as technology systems that could support virtual home visits and health education, were essential during the pandemic [34]. The findings regarding the needs for P&P services are consistent with previous studies. Primary care units required effective management to reduce workload, improve staff morale, and develop the capacity to strengthen service delivery [35]. A system-based partnership is an approach to enhance cooperation between networks to provide P&P services in PHC [36].

4.2. Recommendations

The findings of this study highlighted essential considerations of P&P services in Thailand. There were statistical differences of the coverage of P&P services in some target populations during the COVID-19 pandemic, while P&P services among several target populations were not found statistical significance. However, the percentages of “high coverage” increased in all target populations. This manifested the importance of P&P and required more efforts or heavier workload of primary care units during the pandemic. To deal with this challenge, this study showed that effective resource allocation, capacity building, and support from relevant parties were expected; however, these strategies may be idealistic. Context-specific strategies have the potential to support P&P services. For example, primary care units may allocate budget for some limited services during the pandemic (e.g., in-person rehabilitative care) to P&P services. Primary care unit executive teams can provide clear management directions and strengthen staff’s management skills to enhance the effectiveness of P&P services. Relevant parties outside the health care sector (e.g., schools) can be a good partner to support P&P services among children and adolescents.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study was the representativeness of primary care units across all the health regions of Thailand. Types of participating primary units were various, such as subdistrict health-promoting hospitals, primary care units affiliated with public hospitals, and municipal-affiliated health care centers. The survey questionnaire was designed based on the context of Thailand and revised according to the public health experts/workers' perspectives. This study had several limitations. First, the response rate was low. Data collection occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many primary care units were busy and not able to respond to the questionnaire after the second reminder. Second, the questionnaire was not tested for some types of validity (e.g., construct validity, concurrent validity) and reliability (e.g., test-retest reliability, inter-rater reliability) [37]. In addition, the questionnaire asked participants to provide information about their services in the previous fiscal years. This may have resulted in recall bias. Third, this study did not explore the details of the change in services, such as vaccination, between fiscal years 2019 and 2020. Fourth, the study did not investigate the associations between independent variables (e.g., characteristics of primary care units, numbers of COVID-19 cases) and dependent variables (i.e., the coverage of P&P services).

5. Conclusions

This study highlighted the importance of P&P services and changes in service provision that occurred before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The coverage of P&P services among several target populations was higher during the pandemic. This contributed to a heavy workload for primary care units. Effective resource allocation, capacity building of primary care units and staff, and support from the government, as well as public and private sectors, are required to improve P&P service delivery by primary care units.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Nuntaporn Klinjun, Apichai Wattanapisit, Supattra Srivanichakorn, Patcharin Pingmuangkaew: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents; materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Chutima Rodniam, Thanawan Songprasert, Kannika Srisomthrong, Pornchanuch Chumpunuch, Pattara Sanchaisuriya: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

Dr. Apichai Wattanapisit was supported by Thai Health Promotion Foundation and Community based Health Research and Development Foundation [PP-PC.63-P01003-002].

Data availability statement

Data associated with this study has been deposited at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/BK9KM8.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the study participants for their cooperation and the regional coordinators for their support with data collection.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization Ottawa charter for health promotion 1986. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/129532/Ottawa_Charter.pdf Available from: (accessed on Dec 15, 2021)

- 2.Lee A., Fu H., Chenyi J. Health promotion activities in China from the Ottawa charter to the Bangkok charter: revolution to evolution. Promot. Educ. 2007;14(4):219–223. doi: 10.1177/10253823070140040701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jungo K.T., Anker D., Wildisen L. Astana declaration: a new pathway for primary health care. Int. J. Publ. Health. 2020;65(5):511–512. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01368-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walraven G. The 2018 Astana declaration on primary health care, is it useful? J Glob Health. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.010313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S., Preetha G. Health promotion: an effective tool for global health. Indian J. Commun. Med. 2012;37(1):5–12. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.94009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The L. The Astana Declaration: the future of primary health care? Lancet. 2018;392(10156):1369. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32478-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . World Health Organzation; Geneva: 2019. Report of the Global Conference on Primary Health Care: from Alma-Ata towards Universal Health Coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations Sustainable Development Goals - goal 3: ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/ Available from: (accessed on Feb 6, 2022)

- 9.Kitreerawutiwong N., Kuruchittham V., Somrongthong R., Pongsupap Y. Seven attributes of primary care in Thailand. Asia Pac. J. Publ. Health. 2010;22(3):289–298. doi: 10.1177/1010539509335500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prakongsai P., Srivanichakorn S., Yana T. SSRN; 2009. Enhancing the primary care system in Thailand to improve equitable access to quality health care. (2nd National Health Assembly in Thailand). [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Primary Health Care Systems (PRIMASYS): Case Study from Thailand, Abridged Version. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Geneva World Health Organization; 2017. Primary Health Care Systems (PRIMASYS): Case Study from Nigeria, Abridged Version. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Primary Health Care Systems (PRIMASYS): Case Study from Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . Geneva World Health Organization; 2017. Primary Health Care Systems (PRIMASYS): Case Study from Sri Lanka, Abridged Version. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Primary Health Care Division . Ministry of Public Health; Nonthaburi: 2014. The Four-Decade of Primary Health Development in Thailand 1978-2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wattanapisit A., Saengow U. Patients' perspectives regarding hospital visits in the universal health coverage system of Thailand: a qualitative study. Asia Pac. Fam. Med. 2018;17:9. doi: 10.1186/s12930-018-0046-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srithamrongsawat S., Aekplakorn W., Jongudomsuk P., Thammatach-aree J., Patcharanarumol W., Swasdiworn W., et al. World Health Organization; 2010. Funding Health Promotion and Prevention - the Thai Experience. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lal A., Erondu N.A., Heymann D.L., Gitahi G., Yates R. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. Lancet. 2021;397(10268):61–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32228-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mainous A.G., 3rd, Saxena S., de Rochars V.M.B., Macceus D. COVID-19 highlights health promotion and chronic disease prevention amid health disparities. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020;70(697):372–373. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X711785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weine S., Bosland M., Rao C., Edison M., Ansong D., Chamberlain S., et al. Global health education amidst COVID-19: disruptions and opportunities. Ann. Glob. Health. 2021;87(1):12. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ngamjarus C. n4Studies: Sample size calculation for an epidemiological study on a smart device. Siriraj Med. J. 2016;68(3):160–170. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filion F.L. Estimating bias due to nonresponse in mail surveys. Publ. Opin. Q. 1975;39(4):482–492. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wayne I. Nonresponse, sample size, and the allocation of resources. Publ. Opin. Q. 1975;39(4):557–562. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Health Security Office . Sahamitr Printing & Publishing; Nonthaburi: 2017. 10 Things to Know about Health Insurance. (book in Thai) [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Development Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing Vienna.http://www.r-project.org Available from. (accessed on Mar 31, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tangcharoensathien V., Witthayapipopsakul W., Panichkriangkrai W., Patcharanarumol W., Mills A. Health systems development in Thailand: a solid platform for successful implementation of universal health coverage. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1205–1223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Witthayapipopsakul W., Kulthanmanusorn A., Vongmongkol V., Viriyathorn S., Wanwong Y., Tangcharoensathien V. Achieving the targets for universal health coverage: how is Thailand monitoring progress? WHO South East Asia. J. Public Health. 2019;8(1):10–17. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.255343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuschieri S., Grech V. Protecting our vulnerable in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learnt from Malta. Publ. Health. 2021;198:270–272. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell T., Bellin E., Ehrlich A.R. Older adults and Covid-19: the most vulnerable, the hardest hit. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2020;50(3):61–63. doi: 10.1002/hast.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kabene S.M., Orchard C., Howard J.M., Soriano M.A., Leduc R. The importance of human resources management in health care: a global context. Hum. Resour. Health. 2006;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaweenuttayanon N., Pattanarattanamolee R., Sorncha N., Nakahara S. Community surveillance of COVID-19 by village health volunteers, Thailand. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021;99(5):393–397. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.274308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tejativaddhana P., Suriyawongpaisal W., Kasemsup V., Suksaroj T. The roles of village health volunteers: COVID-19 prevention and control in Thailand. Asia Pac J Health Manag. 2020;15(3):18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merkur S., Sassi F., McDaid D. World Health Organization; 2013. Promoting Health, Preventing Disease: Is There an Economic Case? [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cook L.L., Zschomler D. Virtual home visits during the COVID-19 pandemic: social workers’ perspectives. Practice. 2020;32(5):401–408. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin Y., Wang H., Wang D., Yuan B. Job satisfaction of the primary healthcare providers with expanded roles in the context of health service integration in rural China: a cross-sectional mixed methods study. Hum. Resour. Health. 2019;17(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s12960-019-0403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailie R., Matthews V., Brands J., Schierhout G. A systems-based partnership learning model for strengthening primary healthcare. Implement. Sci. 2013;8(1):143. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsang S., Royse C.F., Terkawi A.S. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2017;11(Suppl 1):S80–S89. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_203_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with this study has been deposited at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/BK9KM8.