Abstract

Immunogenic peptides that mimic linear B-cell epitopes coupled with immunoassay validation may improve serological tests for emerging diseases. This study reports a general approach for profiling linear B-cell epitopes derived from SARS-CoV-2 using an in-silico method and peptide microarray immunoassay, using healthcare workers’ SARS-CoV-2 sero-positive sera. SARS-CoV-2 was tested using rapid chromatographic immunoassays and real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Immunogenic peptides mimicking linear B-cell epitopes were predicted in-silico using ABCpred. Peptides with the lowest sequence identity with human protein and proteins from other human pathogens were selected using the NCBI Protein BLAST. IgG and IgM antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, membrane glycoprotein and nucleocapsid derived peptides were measured in sera using peptide microarray immunoassay. Fifty-three healthcare workers included in the study were RT-PCR negative for SARS-CoV-2. Using rapid chromatographic immunoassays, 10 were SARS-CoV-2 IgM sero-positive and 7 were SARS-CoV-2 IgG sero-positive. From a total of 10 SARS-CoV-2 peptides contained on the microarray, 3 (QTH34388.1-1-14, QTN64908.1-135-148, and QLL35955.1-22-35) showed reactivity against IgG. Three peptides (QSM17284.1-76-89, QTN64908.1-135-148 and QPK73947.1-8-21) also showed reactivity against IgM. Based on the results we predicted one peptide (QSM17284.1-76-89) that had an acceptable diagnostic performance. Peptide QSM17284.1-76-89 was able to detect IgM antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 with area under the curve (AUC) 0.781 when compared to commercial antibody tests. In conclusion in silico peptide prediction and peptide microarray technology may provide a platform for the development of serological tests for emerging infectious diseases such as COVID-19. However, we recommend using at least three in-silico peptide prediction tools to improve the sensitivity and specificity of B-cell epitope prediction, to predict peptides with excellent diagnostic performances.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, B-cell epitopes, Epitope prediction, Peptide microarrays, Serological tests

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Diagnostic methods are crucial for the control of the ongoing coronavirus diseases of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, triggered by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Ferreira et al., 2021; Musicò et al., 2021). Though real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is the most established method in detecting active or current SARS-CoV-2 infections (Rai et al., 2021) serological tests (or equivalently, serology, or antibody testing) are useful in resource-limited settings (Ong et al., 2021; Lagatie et al., 2017). Serological tests are primarily useful to determine whether people were previously infected by SARS-CoV-2 (West and Kobokovich, 2020). This is important at the population level to support surveillance studies, to determine the extent of exposure, case fatality rate, and to track changes in incidence and prevalence (Rai et al., 2021; West and Kobokovich, 2020; Ludolf et al., 2022).

With inadequate access to reagents and equipment, restrictive biosafety level facilities and technical sophistication (Javadi Mamaghani et al., 2021; Vengesai et al., 2021), serology offers an alternative method for screening SARS-CoV-2 (West et al., 2021). However, rapid antigen tests should be considered, as they can diagnose current viral infections unlike serological tests (Ong et al., 2021). Moreover, serological tests may be utilized when molecular or antigen tests results are inconclusive. Serological tests may be helpful in highly suspicious cases with negative molecular tests. In those circumstances, serologic tests may help explain clinical symptom (Ong et al., 2021). Some studies have reported that combining RT-PCR test and serological testing improve the overall sensitivity for detecting SARS-CoV-2 (Fokam et al., 2022; Sidiq et al., 2020).

SARS-CoV-2 infection history could be important for future medical management in cases of late-onset post-infection complications. Serological testing to identify past SARS-CoV-2 infection could be particularly helpful in paediatric patients with multisystem inflammatory syndrome (West et al., 2021). Furthermore, serology tests are often necessary to determine potential donors of convalescent plasma, a therapy for COVID-19 given to patients with active infections to boost their immune response (West et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2020).

Recombinant proteins, especially the S1 protein, are one of the major reagents for SARS-CoV-2 serological tests (Li et al., 2021). Despite recombinant protein based serological tests offering the advantages of (i) working without stringent biosafety requirements, (ii) easy assay standardization and (iii) availability in short periods of time, these tests have several shortcomings (Sidiq et al., 2020). In addition to high spike protein production costs and storage constraints, full length recombinant proteins have significant instability problems, they suffer from batch-to-batch variations and in some cases may cross-react with other coronaviruses (Musicò et al., 2021; Javadi Mamaghani et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). The biggest challenge with cross-reactivity is that it leads to false positive results: a person previously exposed to SARS-CoV may test positive for SARS-CoV-2, although uninfected (Rai et al., 2021). Expressing S1 protein in the correct conformation is difficult, and in some cases, the antibodies that recognize the membrane spike protein are unable to bind recombinant S1 protein (Sidiq et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Additionally, currently available serological tests have sub-optimal diagnostic accuracies (EUA Authorized Serology Test Performance | FDA, 2022). Sidiq and colleagues reported that several studies showed different reactivity of SARS-CoV-2 patient sera with spike protein, ranging from very low (13%) to 100%, depending on the test used (Sidiq et al., 2020).

Immunogenic peptides mimicking linear B-cell epitopes may improve SARS-CoV-2 serological testing (Javadi Mamaghani et al., 2021). Peptide-based serological tests are advantageous, compared to recombinant proteins based serological tests. The main reasons for this are that synthetic peptides are well defined, easily produced in large amounts when required, highly pure with almost no batch-to-batch variation and they are very stable. Moreover, synthetic peptide use is often cost-effective, compared to the production of the spike protein (Li et al., 2021; List et al., 2010; Vengesai et al., 2021; Qi et al., 2020).

We previously reported that six methods can be used for the identification and prediction of linear B-cell epitopes (peptides) (Vengesai et al., 2022). For comprehensive mapping of B-cell epitopes, experimental techniques including overlapping peptides and phage display library are time consuming and expensive even for SARS-CoV-2 which has relatively few genes (Vengesai et al., 2021). In contrast, in-silico B-cell epitope prediction bioinformatics techniques are manageable alternatives that allow for virtual cost-effective screening in the search for immuno-dominant epitopes with serological diagnostic potential (Van Regenmortel, 1989; Giacò et al., 2012).

Several in-silico B-cell epitope prediction bioinformatics databases (Table 1 ) are available, in which computational strategies guide the selection of candidate epitopes for peptide microarray technology validation (Vengesai et al., 2022). For identification of effective vaccine candidates against SARS-CoV-2, Kumar et al. (2021) used various software and online bioinformatics tools including ABCpred, to predict B cell epitopes (Jena et al., 2021). Moreover, Singh et al. (2020) predicted SARS-CoV-2 continuous and discontinuous B-cell epitopes using BCpred 2.0 and Ellipro server, in-silico tools, respectively (Singh et al., 2020). In this study we report on a general approach to discover immunogenic peptides mimicking linear B-cell epitopes derived from SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, membrane glycoprotein and nucleocapsid protein using ABCpred in-silico B-cell epitope prediction and peptide microarray immunoassay validation.

Table 1.

In-silico B-cell epitope prediction software (Vengesai et al., 2022).

| Software | Server |

|---|---|

| APRANK | https://github.com/trypanosomatics/aprank) |

| MLCE | http://bioinf.uab.es/BEPPE |

| ABCpred | http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/abcpred/ |

| BepiPred 1.0 | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/BepiPred/ |

| Epitopia web server | http://epitopia.tau.ac.il/ |

| Antigenic | http://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/emboss/antigenic |

| BCPREDS | http://ailab.ist.psu.edu/bcpred/ |

| Bcepred | http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/bcepred/bcepred_instructions.html |

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical approval and study population

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MCRZ/A/2571/ and MRCZ/A2443/). Fifty-three healthcare workers (cleaners, security officers, nurses, administrators, and doctors) were recruited into the study from health facilities in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe (20.1457˚ S, 28.5873˚ E) in June 2020 prior to COVID-19 vaccination rollout. Prior to recruitment, the study objectives were fully explained to the healthcare workers who then gave their written consent to participate in the study. Negative sera were obtained from Schistosoma mansoni infected individuals collected in 2015 before the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.2. Antibody testing/serological test

Five millilitres of venous blood were collected from each worker. The blood was separated into serum samples within 24 h of collection by centrifugation at 3000 g for 15 min. The serum was used to detect SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (IgM and IgG) using two rapid immunoassay kits (Wuhan UNscience Biotechnology Companies UNICOV-40 test kit and Standard-Q Covid-19 IgM/IgG Duo antibody test from SD Biosensor) following manufacturer's guidelines .

Both test kits detect the presence of IgM and IgG antibodies directed against the nucleocapsid and the spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 (Rusakaniko et al., 2021; SD Biosensor | Products, 2022).

2.3. SARS-CoV-2 real-time reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR-diagnosis

Clinicians collected nasopharyngeal swabs according to WHO and CDC protocols (https://www.who.int/docs/default source/coronaviruse/whoinhouseassays.pdf). RNA was then extracted from these swabs using the respiratory sample RNA isolation kit. Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 virus was performed using Real-Time reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR as described by Rusakaniko et al (2021). The nucleocapsid protein gene and the virus open reading frame 1ab (ORF1ab) gene were amplified simultaneously as recommended by WHO. An internal control (RNasep) gene was used together with negative and positive samples in the assay (Rusakaniko et al., 2021).

2.4. Peptide selection

SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, nucleocapsid protein membrane glycoprotein sequences were obtained from the NCBI protein database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The bioinformatics tool ABCpred was used for the in silico prediction of the SARS-CoV-2 B-cell epitopes on the selected protein sequences. Peptides with the lowest sequence identity with human protein and proteins from other human pathogens were selected using the NCBI Protein BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi select Protein BLAST) to minimize cross reactivity. Peptides that had the highest ABCpred rank (higher probability of being B-cell epitopes) and the lowest sequence identity with peptides from other human pathogens or proteins were selected for inclusion on the peptide microarrays.

2.5. Peptide microarray design and layout

2.5.1. Peptide microarray design

The peptide microarray was designed to contain 9aa-18aa peptides that were obtained from a variety of pathogens and printed in a laser-printer technique by PEPperPRINT GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany) (https://www.pepperprint.com/). Each sub-array on the peptide microarray contained 260 peptide positions. The microarray had 16 sub-arrays (copies) that were framed by flag anti-polio (KEVPALTAVETGAT, 3 spots) and flag anti-HA (hemagglutinin glycoprotein of influenza virus) (YPYDVPDYAG, 3 spots) as a quality control measurement. Ten SARS-CoV-2 peptides (14aa and 16aa) (details given in Table 2 ) were printed with random distribution across each sub-array.

Table 2.

ABCpred predicted B-cell linear epitopes.

| Peptide name | Source Protein | Peptide Sequence | Peptide length |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB: 7KRQ_A-879-894 | Chain A, spike glycoprotein | AGTITSGWTFGAGAAL | 16 |

| PDB: 7KRQ_A-257-272 | Chain, A spike glycoprotein | GWTAGAAAYYVGYLQP | 16 |

| QPK73947.1-8-21 | membrane glycoprotein | ITVEELKKLLEQWN | 14 |

| PDB: 7LX5_B-686-701 | Chain B, spike glycoprotein | GVSVITPGTNTSNQVA | 16 |

| QSM17284.1-76-89 | nucleocapsid protein | TNSSPDDQIGYYRR | 14 |

| QLL35955.1-22-35 | nucleocapsid protein | DGKMKDLSPRWYFY | 14 |

| QTH34388.1-1-14 | membrane glycoprotein | MADSNGTITVEELK | 14 |

| QTN64908.1-135-148 | membrane glycoprotein | ESELVIGAVILRGH | 14 |

| QRU89900.1-41-54 | nucleocapsid protein | RPQGLPNNTASWFT | 14 |

| QTN64908.1-136-149 | membrane glycoprotein | SELVIGAVILRGHL | 14 |

The peptide name consisted of the protein/antigen accession number followed by the amino acids’ positions of the peptide in the protein.

2.5.2. Peptide microarrays immunoassays

The immunoassays consisted of two steps on the same microarray: the pre-incubation step for identifying false positive signals by binding of the fluorescently labelled secondary antibody followed by the main incubation with serum and the secondary antibodies. Each step involved pre-swelling of the peptide microarray with washing buffer (PBS, pH 7.4 with 0.05% Tween 20) for 10 min, followed by incubation with a blocking buffer (Rockland blocking buffer MB-070) for 30 min. Initially, the peptide microarrays were incubated with secondary antibodies [Goat anti-human IgG (Fc) DyLight680 (0.1 µg/ml) and goat anti-human IgM (µ chain) DyLight800 (0.2 µg/ml)] and control antibodies [Mouse monoclonal anti-HA DyLight800 (0.5 µg/ml) and mouse monoclonal anti-polio DyLight800 (0.5 µg/ml] diluted in incubation buffer (washing buffer with 10% blocking buffer) at room temperature for 45 min. In the main step the microarrays were incubated with serum or plasma diluted 1:250 in incubation buffer for 16 h at 4°C and 140 rpm orbital shaking followed by incubation with the secondary antibodies. After each incubation step the microarrays were washed three times with washing buffer for 10 s. The microarrays were scanned using an LI-COR Odyssey Imaging System; scanning offset 0.65 mm, resolution 21 µm, scanning intensities of 7/7 (red = 680 nm / green = 800 nm). To ensure that all microarrays were responding correctly, all steps were repeated with the Cy3-conjugated anti-HA control antibody and Cy3-conjugated anti-polio control antibodies.

2.5.3. Image analysis and spot intensity quantification

Microarray image analysis was done using PepSlide® Analyzer (SICASYS Software GmbH; Heidelberg, Germany) and resulted in raw data CSV files for each sample (green = 800 nm = IgM staining, red = 680 nm = IgG staining). Quantification of spot intensities was based on 16-bit gray scale tiff files. Averaged median foreground intensities (foreground-background signal) and spot-to-spot deviations of spot duplicates were calculated using a PEPperPRINT software algorithm. For duplicate spots a maximum spot-to-spot deviation of 50% was tolerated, otherwise the corresponding intensity value was regarded as artefact and was zeroed.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The data set used for statistical analysis of the peptide microarray results were based on fluorescence intensity. Non-parametric statistical methods were used for data analysis with p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC) were obtained using the web-based calculator for ROC curves, format 5 continuous rating scale. Bar graphs were created in Microsoft excel 2013.

2.7. Antibody reactivity and discrimination between the infected and uninfected groups by detection of immunodominant epitopes

The negative cut-off was determined by averaging the negative control readings (sera from 19 Schistosomiasis mansoni infected individuals collected in 2015 prior the COVID-19 pandemic) and adding 3 standard deviations. A positive response was defined as fluorescence intensity ≥ 500 FU (fluorescence intensity units) (Schwarz et al., 2021) and fluorescence intensity above the negative cut-off for each specific peptide for both IgG and IgM. Peptides not reactivity with at least one sero-positive sera were considered to be not reactive with SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. ROC curve analysis assessed diagnostic accuracy of the peptides and AUC assessed the overall diagnostic performance of the peptide.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

The study population consisted of forty-nine health care workers [14.3% (Ludolf et al., 2022) males and 85.7% (Ceraolo and Giorgi, 2020) females] within the age range of 20-64 years (median age: 38.9; IQR: 29-23) from Bulawayo. The cohort of health workers were of two different health settings [87.8% (Carmona et al., 2012) hospital and 12.2% (West and Kobokovich, 2020) clinic] and comprised of 53.1% (Jena et al., 2021) nurses, 2% (Ferreira et al., 2021) doctor, 16.3% (Javadi Mamaghani et al., 2021) nurse aides, 16.3% (Javadi Mamaghani et al., 2021) student nurses, 8.2% (Ong et al., 2021) general and 4.1% (Musicò et al., 2021) clerks. Four workers who did not have demographic data were also included in the study. All individuals tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 using RT-PCR. Using rapid chromatographic immunoassays, 10 were SARS-CoV-2 IgM positive and 7 were SARS-CoV-2 IgG positive.

3.2. SARS-CoV-2 B-cell epitope profiling

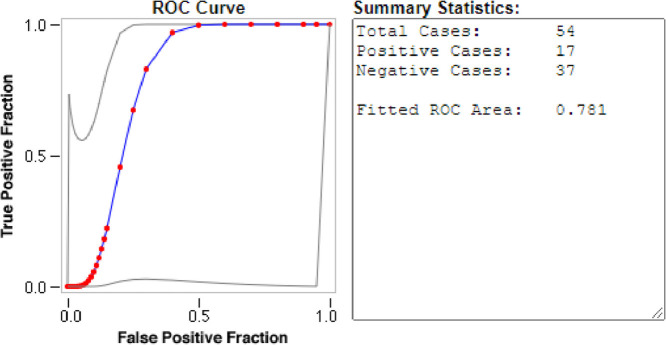

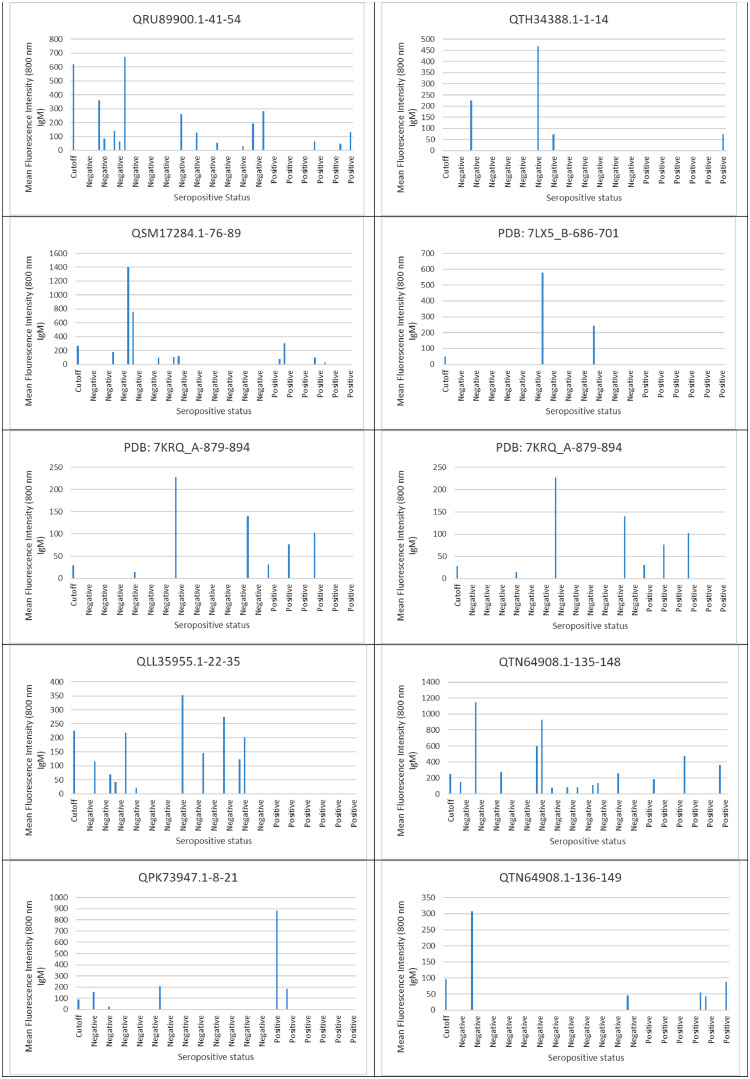

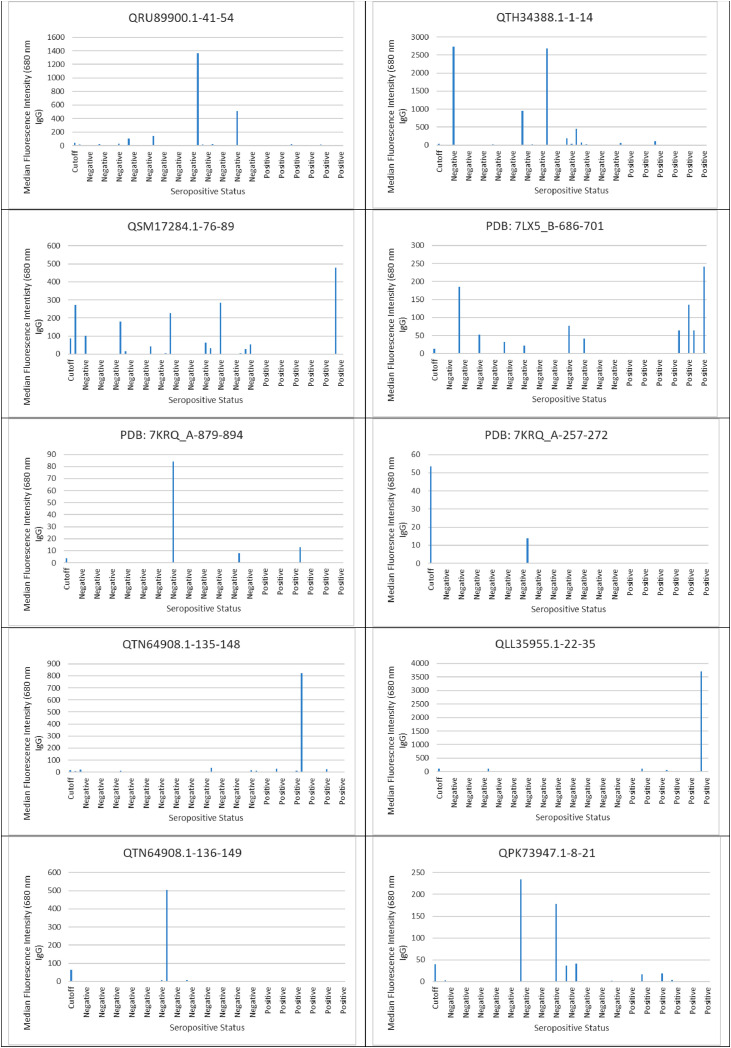

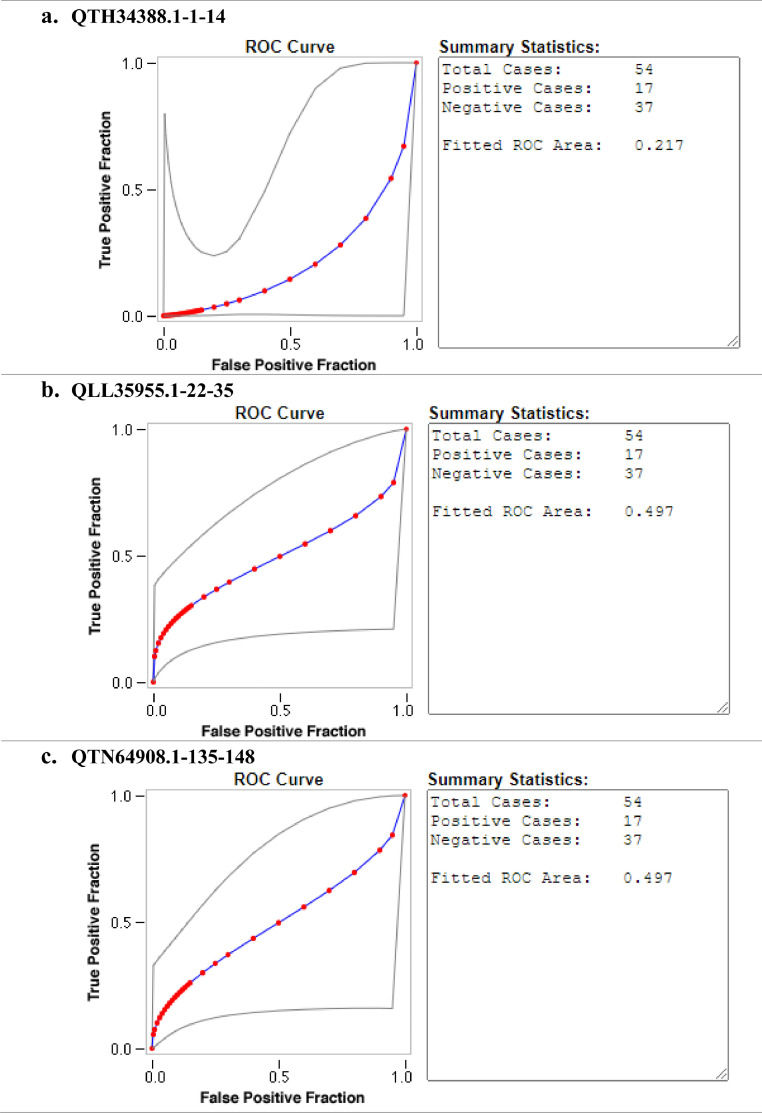

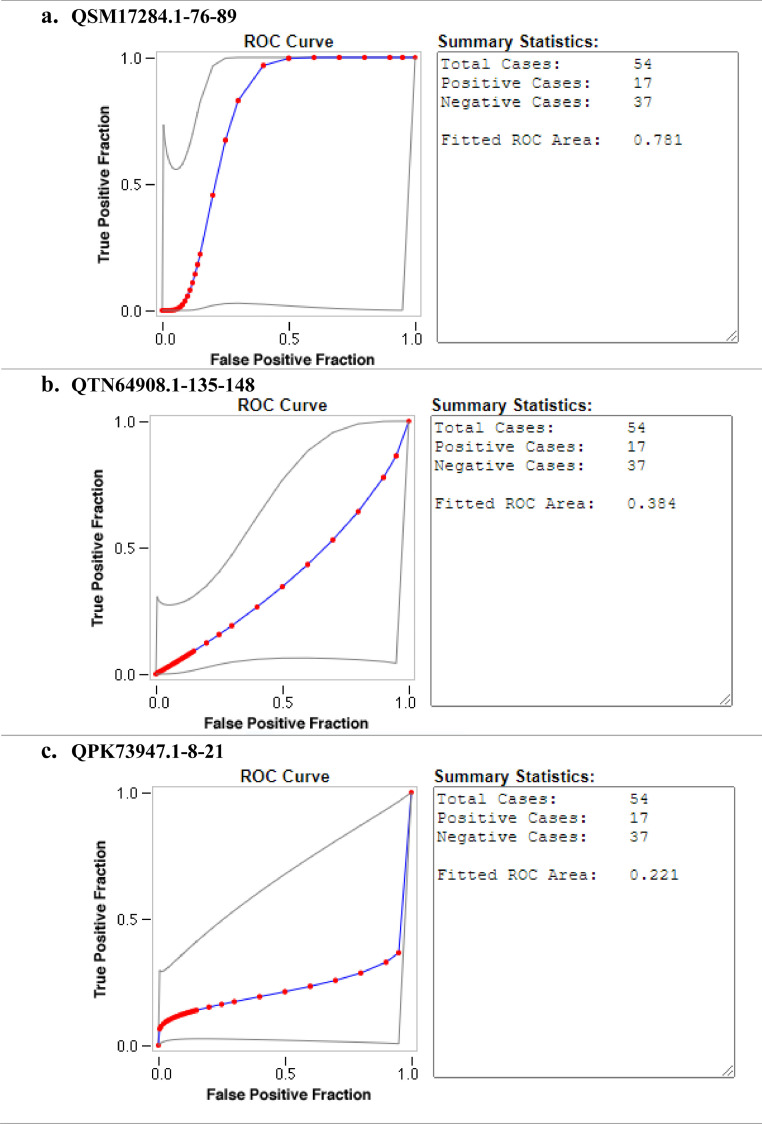

Ten SARS-CoV-2 ABCpred in-silico predicted peptides were screened on a peptide microarray platform and five peptides were reactive (Figs. 1 and 2 and supplementary file 1). For IgG, two were reactive; QTH34388.1-1-14 derived from the membrane glycoprotein (reactive with nine sero-negative sera and one sero-positive serum) and QLL35955.1-22-35 derived from nucleocapsid protein (reactive with one sero-positive serum). With respect to IgM, two peptides were also reactive; QSM17284.1-76-89 derived from nucleocapsid protein (reactive with one sero-negative serum and one sero-positive serum), QPK73947.1-8-21 derived from membrane glycoprotein (reactive with one sero-negative serum and one sero-positive serum). Peptide QTN64908.1-135-148 was reactive with both SARS-CoV-2 IgG (reactive with three sero-negative sera and three sero-positive sera) and IgM (reactive with five sero-negative sera and two sero-positive sera). None of the peptides that reacted with SARS-CoV-2 IgG were able to distinguish between SARS-CoV-2 sero-negative and sero-positive sera with AUC below 0.5 (Fig. 3 ). Peptide QSM17284.1-76-89 was able to detect IgM antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 with an acceptable AUC of 0.781 when compared to commercial antibody tests (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 1.

IgM evaluation in serum and plasma samples derived SARS-CoV-2 sero-negative and sero-positive healthcare workers against SARS-CoV-2 predicted peptides.

Fig. 2.

IgG evaluation in serum and plasma samples derived SARS-CoV-2 sero-negative and sero-positive healthcare workers against SARS-CoV-2 predicted peptides.

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of the accuracy of SARS-CoV-2 reactive peptides against IgG. The diagnostic accuracy was determined by ROC curves. RED symbols and BLUE line indicate the fitted ROC curve. GRAY lines indicate the 95% confidence interval of the fitted ROC curve.

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of the accuracy of SARS-CoV-2 reactive peptides against IgM. The diagnostic accuracy was determined by ROC curves. RED symbols and BLUE line indicate the fitted ROC curve. GRAY lines indicate the 95% confidence interval of the fitted ROC curve.

4. Discussion

Peptide microarray technology is an ideal tool to decipher epitope-specific B-cell immune responses toward the proteome of an emerging pathogen including SARS-CoV-2. The technology enables the simultaneous analysis of peptides in a fast and cost-effective way for applications, such as epitope discovery (Deeks et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 has relatively few numbers of proteins, classified as either structural or non-structural. The spike glycoprotein, nucleocapsid protein, membrane glycoproteins and envelope protein are the main structural proteins (Farrera-Soler et al., 2020). In light of this background, this study focused on the spike protein, nucleocapsid protein, membrane glycoproteins. Ten SARS-CoV-2 peptides were predicted in-silico with ABCpred, a widely used, freely available and user-friendly online tool. Following epitope prediction, peptide microarrays were generated in a laser-printer based approach by PEPperPRINT and evaluated with SARS-CoV-2 sero-positive and sero-negative sera.

Despite several studies identifying linear B-cell epitopes with good diagnostic performances in discriminating SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals from SARS-CoV-2 negative individuals (Musicò et al., 2021, Li et al., 2021, Schwarz et al., 2021, Holenya et al., 2021), our approach however identified one peptide (QSM17284.1-76-89) with an acceptable diagnostic performance. Tatjana and colleagues identified linear B-cell epitopes potentially applicable for early and or late COVID-19 diagnosis (Schwarz et al., 2021). Musicò et al. (2021), identified an epitope of the nucleocapsid protein (region 155-71) with good diagnostic performance (92% sensitivity and 100%) in discriminating SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals from healthy individuals. Li et al. (2021) identified several spike protein-derived 12-mer peptides that have high diagnostic performance. One peptide (aa 1148–1159 or S2–78) in particular exhibited a sensitivity of 95.5%, 95% CI 93.7–96.9% and specificity of 96.7%, 95% CI 94.8–98.0%.

However, it should be noted that the studies that identified linear B-cell epitopes with good diagnostic performances used whole-proteome peptide microarray analysis whilst in our current in-silico-based study only a few peptides were selected. The spike glycoprotein is transcribed into 1273 amino acid (aa), envelope protein into 76 aa, membrane protein into 220 aa to 260 aa, and nucleocapsid protein into 419 aa (Satarker and Nampoothiri, 2020). In the present study, only three 16 aa non-overlapping peptides covering approximately 4% of protein sequence were selected for the spike protein, only three 14 aa non-overlapping peptides covering approximately 10% of protein sequence were selected for the nucleocapsid protein and with respect to membrane glycoprotein, four 14 aa non-overlapping peptides covering approximately 20% of protein sequence were selected. The implication for such selection is that potential immunogenic peptides may be missed and we recommend including all predicted peptides in prospective studies.

Several SARS-CoV-2 studies have reported antibody reactivity against the spike protein, nucleocapsid protein and membrane proteins with binding predominantly occurring on the spike protein and nucleocapsid protein, indicating that these two proteins are immunodominant (Holenya et al., 2020; Poh et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Lopandić et al., 2021). However, we detected the nucleocapsid protein and membrane glycoproteins antibody reactivity, suggesting possible early infection as it has been postulated that antibody to the nucleocapsid protein is more sensitive than the spike protein antibody for detecting early SARS-CoV-2 infection (Burbelo et al., 2020).

One of the principal condition in antibody testing is to ensure that there is limited cross-reactivity of antibodies to other antigens (La Marca et al., 2020). Antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection are impeded by immunological cross-reactivity among the human coronaviruses. The SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 genomes are highly similar. SARS-CoV-2 has ∼30 kb positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome which shares ∼80% sequence identity with that of SARS-CoV-1 (Wang et al., 2020; Arya et al., 2021). Consequently, many of the proteins found in SARS-CoV-2 (NC_045512.2) are also found in SARS-CoV-1 (AY515512.1 or NC_004718.3) with 77.1% of the protein sequences shared in their proteomes (Ceraolo and Giorgi, 2020). To increase the probability of selecting SARS-CoV-2 unique peptides and mitigate the limitation posed by cross reactivity, peptides with the highest ABCpred rank and with the least cross-reactivity with proteins from other human pathogens (especially SARS-CoV-1 and Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus) were selected for inclusion in the peptide microarrays.

5. Limitations

In-silico prediction of B-cell epitopes is still an active biotechnology research field and a number of servers show improved performance, albeit with prediction accuracies that are still not satisfactory. ABCpred server predict B cell epitopes in an antigen sequence with 65.93% accuracy using artificial recurrent neural network (machine based technique) (Saha and Raghava, 2006). Current B-cell epitope predictors are also based on epitopes derived from heterogeneous experimental conditions including many cases in which laboratory animals were immunized with relatively large doses of highly purified antigens. Unfortunately, it has been reported that humoral immune responses against the same antigen differ between species and members of the same species. Moreover, significant variability in individual B-cell epitope reactivity has been reported in tuberculosis and toxoplasmosis (Carmona et al., 2012).

6. Conclusion

Three peptides (QTH34388.1-1-14, QTN64908.1-135-148, and QLL35955.1-22-35) showed reactivity against SAR-CoV-2 IgG. Three peptides (QSM17284.1-76-89, QTN64908.1-135-148 and QPK73947.1-8-21) showed reactivity against SARS-CoV-2 IgM. The reactive peptides were derived from the membrane glycoprotein and nucleocapsid protein. Peptide QSM17284.1-76-89 was able to detect IgM antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 with area under the curve of 0.781 when compared to commercial serological tests. In conclusion in silico peptide prediction and peptide microarray technology provide a powerful platform for the development of new serological tests for emerging infectious diseases.

Funding

This research was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research programme (16/136/33) using UK aid from the UK Government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Arthur Vengesai: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Thajasvarie Naicker: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Herald Midzi: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Maritha Kasambala: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Victor Muleya: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Isaac Chipako: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Emilia Choto: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Praise Moyo: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Takafira Mduluza: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Francisca Mutapi funding acquisition. The authors would also like to acknowledge the valuable input of Professor Francisca Mutapi and Professor Simbarashe Rusakaniko. We would also like to acknowledge, Tackling Infections to Benefit Africa (TIBA) for training on the selection of B-cell epitopes.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2022.106781.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

References

- Ferreira C.S., Martins Y.C., Souza R.C., Vasconcelos ATR. EpiCurator: an immunoinformatic workflow to predict and prioritize SARS-CoV-2 epitopes. PeerJ. 2021;9:e12548. doi: 10.7717/peerj.12548. https://peerj.com/articles/12548 [Internet]Nov 30 [cited 2022 Jun 23]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musicò A., Frigerio R., Mussida A., Barzon L., Sinigaglia A., Riccetti S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 epitope mapping on microarrays highlights strong immune-response to N protein region. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):35. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010035. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/9/1/35/htm Vol. 9, Page 35 [Internet]. 2021 Jan 11 [cited 2022 Jun 23]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai P., Kumar B.K., Deekshit V.K., Karunasagar I., Karunasagar I. Detection technologies and recent developments in the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021;105(2):441–455. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-11061-5. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00253-020-11061-5 [Internet]Jan 1 [cited 2022 Oct 6]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong D.S.Y., Fragkou P.C., Schweitzer V.A., Chemaly R.F., Moschopoulos C.D., Skevaki C. How to interpret and use COVID-19 serology and immunology tests. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021;27(7):981–986. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.05.001. https://www.clinicalmicrobiologyandinfection.com/article/S1198743X21002214/fulltext [Internet]Jul 1 [cited 2022 Oct 6]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagatie O., Van Loy T., Tritsmans L., Stuyver L.J., Stansfield S.H., Patel P., et al. No title. PLoS One. 2017;8(1):317–325. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ukzn.idm.oclc.org/25836992/ [Internet]Dec 1 [cited 2020 Nov 22]Available from: [Google Scholar]

- West R., Kobokovich A. Understanding the accuracy of diagnostic and serology tests: sensitivity and specificity factsheet. 2020.

- Ludolf F., Ramos F.F., Bagno F.F., Oliveira-Da-Silva J.A., Reis T.A.R., Christodoulides M., et al. Detecting anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in urine samples: a noninvasive and sensitive way to assay COVID-19 immune conversion. Sci. Adv. 2022;8(19) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abn7424. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abn7424 [Internet]May 1 [cited 2022 Oct 6]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadi Mamaghani A., Arab-Mazar Z., Heidarzadeh S., Ranjbar M.M., Molazadeh S., Rashidi S., et al. In-silico design of a multi-epitope for developing sero-diagnosis detection of SARS-CoV-2 using spike glycoprotein and nucleocapsid antigens. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Jun 11];10(1):1–15. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34849326/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vengesai A., Midzi H., Kasambala M., Mutandadzi H., Mduluza-Jokonya T.L., Rusakaniko S., et al. A systematic and meta-analysis review on the diagnostic accuracy of antibodies in the serological diagnosis of COVID-19. Syst. Rev. 2021;10(1):1–23. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01689-3. https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-021-01689-3 [Internet]Dec 1 [cited 2022 Jun 14]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R., Kobokovich A., Connell N., Gronvall GK. COVID-19 antibody tests: a valuable public health tool with limited relevance to individuals. Trends Microbiol. 2021;29(3):214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2020.11.002. https://www.cell.com/article/S0966842X20302808/fulltext [Internet]Mar 1 [cited 2022 Oct 6]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokam J., Alteri C., Colagrossi L., Genevieve A.-.M., Siré Takou D., Ndjolo A., et al. Diagnostic performance of molecular and serological tests of SARS-CoV-2 on well-characterised specimens from COVID-19 individuals: the EDCTP ‘PERFECT-study’ protocol (RIA2020EF-3000) PLoS One. 2022;17(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0273818. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0273818 [Internet][cited 2022 Oct 6]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidiq Z., Hanif M., Dwivedi K.K., Chopra KK. Benefits and limitations of serological assays in COVID-19 infection. Indian J. Tuberc. 2020;67(4):S163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2020.07.034. [Internet]Dec 1 [cited 2022 Oct 6]Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7409828/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Zhang H., Zhan M., Jiang J., Yin H., Dauphars D.J., et al. Antibody response and therapy in COVID-19 patients: what can be learned for vaccine development? Sci. China Life Sci. 2020;63(12):1833–1849. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1859-y. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11427-020-1859-y 2020 6312 [Internet]Dec 1 [cited 2022 Oct 6]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Lai D., yun, Lei Q., Xu Z., Wei, Wang F., Hou H., et al. Systematic evaluation of IgG responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-derived peptides for monitoring COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021;18(3):621–631. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-00612-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33483707/ [Internet]Mar 1 [cited 2022 Oct 6]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., L.D. yun, Lei Q., XuZ wei, Wang F., Hou H., et al. Systematic evaluation of IgG responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-derived peptides for monitoring COVID-19 patients. 2021 [cited 2022 Jun 11];18(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33483707/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li Y., yun L.D., Lei Q., wei XuZ, Wang F., Hou H., et al. Systematic evaluation of IgG responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-derived peptides for monitoring COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021;18(3):621–631. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-00612-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33483707/ [Internet]Mar 1 [cited 2022 Oct 31]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUA Authorized Serology Test Performance | FDA. [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/eua-authorized-serology-test-performance.

- List C., Qi W., Maag E., Gottstein B., Müller N., Felger I. Serodiagnosis of echinococcus spp. infection: explorative selection of diagnostic antigens by peptide microarray. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010;4(8):e771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000771. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20689813/ [Internet]Aug 3 [cited 2020 Feb 26]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengesai A., Naicker T., Kasambala M., Midzi H., Mduluza-Jokonya T., Rusakaniko S., et al. Clinical utility of peptide microarrays in the serodiagnosis of neglected tropical diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: protocol for a diagnostic test accuracy systematic review. 2021 Jul [cited 2022 Jan 9];11(7):e042279. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34330850/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Qi H., Ma M.-.L., Jiang H.-.W., Ling J.-.Y., Chen L.-.Y., Zhang H.-.N., et al. Systematic profiling of SARS-CoV-2 specific IgG epitopes at single amino acid resolution. medRxiv [Internet]. 2020 Sep 9 [cited 2020 Dec 11];2020.09.08.20190496. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.08.20190496.

- Vengesai A., Kasambala M., Mutandadzi H., Mduluza-Jokonyaid T.L., Mduluzaid T., Naicker T., et al. Scoping review of the applications of peptide microarrays on the fight against human infections. PLoS One. 2022;17(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248666. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0248666 [Internet]Jan [cited 2022 Feb 13]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengesai A., Kasambala M., Mutandadzi H., Mduluza-5 Jokonya T.L., Mduluza T., Naicker T. Scoping review of the applications of peptide microarrays on the fight against human short title: peptide microarrays application 4. bioRxiv [Internet]. 2021 Mar 4 [cited 2021 Jun 14];2021.03.04.433859. Available from: 10.1101/2021.03.04.433859.

- Van Regenmortel M.H.V. Structural and functional approaches to the study of protein antigenicity. Immunol. Today. 1989;10:266–272. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(89)90140-0. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2478146/ [Internet] [cited 2021 Jun 14]. Immunol TodayAvailable from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S., Raghava G.P.S.S. Prediction of continuous B-cell epitopes in an antigen using recurrent neural network. 2006 [cited 2021 Feb 9];65(1):40–8. Available from: https://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/prot.21078. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Giacò L., Amicosante M., Fraziano M., Gherardini P.F., Ausiello G., Helmer-Citterich M., et al. B-Pred, a structure based B-cell epitopes prediction server. Adv. Appl. Bioinform. Chem. 2012;5(1):11–21. doi: 10.2147/AABC.S30620. [Internet]Jul 25 [cited 2021 Jun 14]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jena M., Kumar V., Kancharla S., Kolli P. Reverse vaccinology approach towards the in-silico multiepitope vaccine development against SARS-CoV-2. F1000Research 2021 1044 [Internet]. 2021 Jan 23 [cited 2022 Feb 18];10:44. Available from: https://f1000research.com/articles/10-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Singh A., Thakur M., Sharma L.K., Chandra K. Designing a multi-epitope peptide based vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 18];10(1):1–12. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-73371-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rusakaniko S., Sibanda E.N., Mduluza T., Tagwireyi P., Dhlamini Z., Ndhlovu C.E., et al. SARS-CoV-2 serological testing in frontline health workers in Zimbabwe. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021;15(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009254. [Internet]Mar 1 [cited 2021 Jun 14]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SD Biosensor | Products [Internet]. [cited 2022 Oct 6]. Available from: https://www.sdbiosensor.com/product/product_view?product_no=239.

- Schwarz T., Heiss K., Mahendran Y., Casilag F., Kurth F., Sander L.E., et al. SARS-CoV-2 proteome-wide analysis revealed significant epitope signatures in COVID-19 patients. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:765. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.629185. www.frontiersin.org [Internet]Mar 23 [cited 2021 May 24]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks J.J., Dinnes J., Takwoingi Y., Davenport C., Spijker R., Taylor-Phillips S., et al. Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013652. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD013652/full [Internet] John Wiley and Sons Ltd[cited 2021 Mar 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrera-Soler L., Daguer J.P., Barluenga S., Vadas O., Cohen P., Pagano S., et al. Identification of immunodominant linear epitopes from SARS-CoV-2 patient plasma. PLoS One. 2020;15(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238089. [Internet]Sep 1 [cited 2021 Jun 14]septemberAvailable from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holenya P., Lange P.J., Reimer U., Woltersdorf W., Panterodt T., Glas M., et al. Peptide microarray-based analysis of antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 identifies unique epitopes with potential for diagnostic test development. Eur. J. Immunol. 2021;51(7):1839–1849. doi: 10.1002/eji.202049101. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/eji.202049101 [Internet]Jul 1 [cited 2022 Jun 24]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satarker S., Nampoothiri M. Structural proteins in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2. Arch. Med. Res. 2020;51:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.05.012. Elsevier Inc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holenya P., Lange P.J., Reimer U., Woltersdorf W., Pan-Terodt T., Glas M., et al. Peptide microarray based analysis of antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 identifies unique epitopes with potential for diagnostic test development. medRxiv [Internet]. 2020 Nov 27 [cited 2020 Dec 11];2020.11.24.20216663. Available from: 10.1101/2020.11.24.20216663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Poh C.M., Carissimo G., Wang B., Amrun S.N., Lee C.Y.P., Chee R.S.L., et al. Two linear epitopes on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein that elicit neutralising antibodies in COVID-19 patients. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16638-2. [Internet]Dec 1 [cited 2021 Jun 14]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Wu X., Zhang X., Hou X., Liang T., Wang D., et al. SARS-CoV-2 proteome microarray for mapping COVID-19 antibody interactions at amino acid resolution. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020;6(12):2238–2249. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00742. [Internet]Dec 23 [cited 2021 Jun 14]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopandić Z., Protić-Rosić I., Todorović A., Glamočlija S., Gnjatović M., Ćujic D., et al. Igm and IgG immunoreactivity of SARS-CoV-2 recombinant m protein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(9):4951. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094951. [Internet]May 1 [cited 2021 Jun 14]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbelo P.D., Riedo F.X., Morishima C., Rawlings S., Smith D., Das S., et al. Detection of nucleocapsid antibody to SARS-CoV-2 is more sensitive than antibody to spike protein in COVID-19 patients. medRxiv. 2020 Apr 24;2020.04.20.20071423.

- La Marca A., Capuzzo M., Paglia T., Roli L., Trenti T., Nelson S.M. Testing for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): a systematic review and clinical guide to molecular and serological in-vitro diagnostic assays. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2020;41:483–499. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.06.001. Elsevier Ltd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya R., Kumari S., Pandey B., Mistry H., Bihani S.C., Das A., et al. Structural insights into SARS-CoV-2 proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2021;Vol. 433 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.11.024. Academic Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceraolo C., Giorgi F.M. Genomic variance of the 2019-nCoV coronavirus. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(5):522–528. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25700. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jmv.25700 [Internet]May 1 [cited 2021 Jun 14]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona S.J., Sartor P.A., Leguizamón M.S., Campetella O.E., Agüero F. Diagnostic peptide discovery: prioritization of pathogen diagnostic markers using multiple features. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):50748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050748. www.plosone.org [Internet]Dec 14 [cited 2020 Nov 22]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.