Abstract

Educational courses that teach positive psychology interventions as part of university degree programs are becoming increasingly popular, and could potentially form part of university-wide strategies to respond to the student mental health crisis. To determine whether such courses are effective in promoting student wellbeing, we conducted a systematic review of studies across the globe investigating the effects of positive psychology courses taught within university degree programs on quantitative measures of psychological wellbeing. We searched Embase, PsychInfo, PubMed, and Web of Science electronic databases from 1998 to 2021, identifying 27 relevant studies. Most studies (85%) reported positive effects on measures of psychological wellbeing, including increased life satisfaction and happiness. However, risk of bias, assessed using the ROBINS-I tool, was moderate or serious for all studies. We tentatively suggest that university positive psychology courses could be a promising avenue for promoting student wellbeing. However, further research implementing rigorous research practices is necessary to validate reported benefits, and confirm whether such courses should form part of an evidence-based response to student wellbeing.

Systematic review registration

[https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=224202], identifier [CRD42020224202].

Keywords: positive psychology interventions, university, college, higher education, psychoeducation

Introduction

Increasingly, concerns have been raised over the psychological wellbeing of university students. Psychological wellbeing encompasses both feelings of happiness (hedonic wellbeing), and a sense of meaning, purpose, or satisfaction with life (eudemonic wellbeing) (Deci and Ryan, 2008). A survey of over 10,000 students in the United Kingdom reported that just 11% report high levels of happiness and 6% report high life satisfaction (Neaves and Hewitt, 2021).

University students also commonly experience mental health issues, including suicidal ideation (Mortier et al., 2018). In an international survey, 31% of first-year students screened positive for a mental health disorder (Auerbach et al., 2018). This problem is expected to worsen with increasing numbers of young people entering university (Bolton, 2020). Although some researchers have proposed that wellbeing follows a ‘U’ shaped curve (Blanchflower and Oswald, 2008), reaching its lowest point during midlife, others’ have disputed this (Galambos et al., 2020).

Whilst poor psychological wellbeing in students may be partially due to the peak age of onset of mental health disorders coinciding with the average age of undergraduates (Kessler et al., 2005), wellbeing concerns are heightened among university students compared to peers (Lewis et al., 2021). Student psychological wellbeing declines after starting university, and does not return to pre-university levels (Bewick et al., 2010). Poor psychological wellbeing impairs academic performance (Bruffaerts et al., 2018) and increases the likelihood of dropping out (Hjorth et al., 2016). In contrast, positive psychological wellbeing increases confidence in completing degree programs (Lipson and Eisenberg, 2018).

At present, university services cannot adequately address students’ psychological wellbeing. Services are increasingly overburdened and under-resourced, resulting in long wait times (Randstad, 2020). One possible approach that may help to relieve these issues is to introduce academic courses focused on psychological wellbeing. Whereas traditional wellbeing services are targeted toward students with existing mental health difficulties, these courses take a community-wide approach, promoting psychological wellbeing at a university-level. Embedding these courses into degree programs is thought to be beneficial in promoting engagement and retention, as well as reducing stigma by having all students participate to meet course requirements.

University wellbeing courses take a variety of approaches, including mindfulness (Hassed et al., 2009), mental health literacy (Kurki et al., 2021), and psychoeducational life skills (Limarutti et al., 2021). In this review, we focus on wellbeing courses delivered within a positive psychology framework. Within such courses, students are taught evidence-based positive psychology interventions designed to enhance wellbeing by promoting happiness, life satisfaction, resilience, and social support. Examples include expressing gratitude (Wood et al., 2010), utilizing strengths (Quinlan et al., 2012), and performing acts of kindness (Curry et al., 2018).

Several meta-analyses have indicated that positive psychology interventions are effective in increasing psychological wellbeing and decreasing depression and anxiety, with benefits maintained at 3–6 months (Bolier et al., 2013; White et al., 2019; Carr et al., 2020). Within educational settings, the effectiveness of courses teaching positive psychology interventions has been predominantly investigated in schools (Seligman et al., 2009). Systematic reviews have concluded that positive psychology courses delivered as part of primary and secondary school curriculum benefit students’ psychological wellbeing, mental health, and academic performance (Waters, 2011; Tejada-Gallardo et al., 2020).

The strong evidence base underlying positive psychology interventions suggests that they may be beneficial in promoting student psychological wellbeing when delivered as part of university curriculum. Such courses are increasingly common (see Barrington-Leigh, 2022 for a list of courses offered across universities), are highly popular, and receive widespread media attention (Shimer, 2018). However, there is a lack of systematic understanding of the nature of these courses and their effects on psychological wellbeing. With courses reaching growing numbers of students, it is increasingly important that we understand their impact.

As there was a conspicuous gap in the literature, we therefore conducted a systematic review of wellbeing courses teaching positive psychology interventions that were embedded in university degree programs. Systematic reviews are an essential component of research governance and good professional practice. We aimed to identify the characteristics of courses offered to students, and whether the courses have a positive effect on psychological wellbeing and mental health.

Methods

Systematic review protocol

This review was pre-registered on PROSPERO prior to study searches being conducted1.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for studies was formulated using the PICOS framework as follows:

-

•

Participants were students enrolled in taught degree programs at higher education institutions.

-

•

Interventions were courses embedded within university taught degree programs that used positive psychology techniques with the aim of improving student psychological wellbeing.

-

•

Comparators were other higher education courses without positive psychology interventions. For studies without control conditions, we included studies comparing within-subject effects from pre- to post-course.

-

•

Outcomes were quantitative measures of psychological wellbeing. As a secondary outcome we extracted data for quantitative measures of mental health difficulties. We included loneliness within this due to strong links with mental health (Mann et al., 2022).

-

•

Study Designs were restricted to quantitative studies, although studies could use a variety of designs including randomized clinical trials, quasi-experimental and observational designs.

We restricted studies to those available in English and published from 1998 onward, to coincide with the beginning of the positive psychology movement as in similar reviews (Bolier et al., 2013).

Exclusion criteria

We excluded (1) narrative reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses, (2) conference proceedings/presentations as sufficient data was typically not available to establish eligibility, (3) studies that were not available in English, (4) courses that only implemented mindfulness-based techniques as there is already well-established evidence of the benefits of such courses in university settings (Dawson et al., 2020). During the screening stage, we also chose to exclude courses that only taught Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) techniques. Although ACT incorporates Positive Psychology principles it originated from a clinical psychology framework (Howell and Passmore, 2019). Additionally, the effectiveness of ACT courses in university settings has previously been reviewed (Howell and Passmore, 2019).

Search strategy

We searched four electronic databases for studies published between January 1998 and November 2021: PsychInfo, PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science. We used four main search terms combined using the Boolean operator ‘And’:

-

(1)

Wellbeing OR wellbeing OR ‘positive psychology’ OR happiness OR happy OR ‘PERMA’

-

(2)

University OR college OR ‘higher education’ OR undergraduate

-

(3)

Course OR programme OR program

-

(4)

Effect OR impact OR eval* OR effic*

Study screening and selection, data extraction and study quality assessment

The references of studies identified in the electronic search were uploaded to the systematic review software Covidence, and duplicates were removed. The following steps were then completed independently by two reviewers, and disagreements at each stage were resolved by a third reviewer. Studies were first screened based on titles and abstracts, and then re-assessed based on the full text. The reference list of identified studies were manually searched for additional eligible studies, which underwent the same screening procedure. A standardized, pre-piloted form was used to extract data.

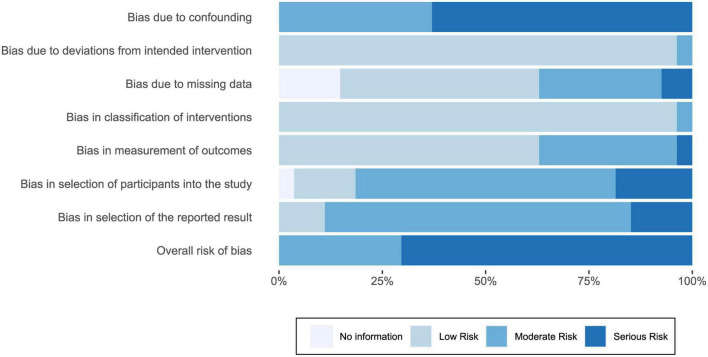

Reviewers also independently conducted a quality assessment using the risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) tool (Sterne et al., 2016). Potential bias relating to confounding, participant selection, classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of reported results was assessed. An overall risk of bias was determined based on the highest risk identified in each subtype of risk.

Results

Search

Figure 1 shows a PRISMA flow diagram detailing the full search process. A simplified table illustrating the search results is presented in Supplementary Table 1. From 2978 unique references identified in electronic databases and 12 references from manual searches, 27 studies were included. Inter-rater reliability was κ = 0.58 for title and abstract screening, and κ = 0.72 for the full text screening.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study search process.

Study characteristics

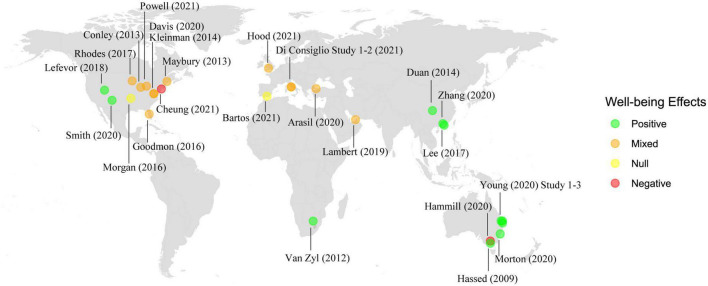

Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Studies were published between 2009 and 2021 and were conducted in 10 countries (Figure 2). The most common countries were the USA (k = 11), Australia (k = 6), China (k = 2), and Italy (k = 2).

TABLE 1.

Study characteristics and reported effects of interventions on wellbeing.

| Study | Institution, country | Timepoints | Intervention condition |

Control condition |

Well-being |

|||||||

| N Pre | N Post | Course length | Program | PPIs | Type | N Pre | N Post | Measure | Effect | |||

| Arasil et al., 2020 | Üsküdar University, Turkey | Pre, Post | 308 | 308 | 14 weeks | Mandatory open unit | Empathy, emotional skills, communication skills, relationships, resilience | None | – | – | Life evaluation questiona | Increase |

| WEMWBS | None | |||||||||||

| OHQ | None | |||||||||||

| SWLS | None | |||||||||||

| PWI | None | |||||||||||

| Bartos et al., 2021 | Royal Conservatory of Music Victoria Eugenia, Spain | Post | 82 | 40 | 27 weeks | Music | Gratitude, kindness, empathy, strengths, mindfulness, physical activity (yoga), emotional skills, communication skills, flow | Other elective courseb | 115 | 53 | VAS psychological health | None |

| Cheung et al., 2021 | Albert Einstein College of Medicine, USA | Each session | 157 | 157 | 16 weeks | Medicine | Gratitude, kindness, savoring, mindfulness, emotional skills, positive reappraisal | None | – | – | Frequency of positive emotions | Decrease |

| Conley et al., 2013 | Loyola University Chicago, USA | Pre, Post | 29 | 29 | 8 months | Open unit | Strengths, emotional skills, communication skills, relationships, stress management | Alternative course (‘Global citizens and citizenships’) | 22 | 22 | Latent variable ‘positive wellbeing’ | None |

| Perceived improvements – Psychosocial adjustment | Increase | |||||||||||

| Davis, 2020 | James Madison University, USA | Pre, Post | 30 | 30 | 15 weeks | Psychology | Gratitude, forgiveness, savoring, strengths, mindfulness, physical activity, emotional skills, engaging with the natural environment, resilience, meaning in life, flow, positive reappraisal, relationships | Other psychology course | 20 | 20 | Henrique’s 10-Item wellbeing scale | Increase |

| PANAS positive | Increase | |||||||||||

| PERMA profiler | None | |||||||||||

| SLS | None | |||||||||||

| OHQ | None | |||||||||||

| Di Consiglio et al., 2021, Study 1 | Sapienza University of Rome, Italy | Pre, Post | 12 | 12 | 12 weeksc | Open Unit | Gratitude, kindness, empathy, strengths, emotional skills, communication skills | Offline version of unit without exercises and self-monitoring tools | 12 | 12 | R-PWB | Increase in self-acceptance subscale only |

| Di Consiglio et al., 2021, Study 2 | Sapienza University of Rome, Italy | Pre, Post | 154 | 59 | 12 weeksc | Open Unit | Gratitude, kindness, empathy, strengths, emotional skills, communication skills | None | – | – | R-PWB | Increase in self-acceptance subscale only |

| Duan et al., 2014 | Southwest University, Chongqing, China | Pre, Post, 18-weeks | 211 | 211 | 6 weeksd | Psychology writing skills training | Strengths | Psychology writing skills training without positive psychology interventionse | 74 | 74 | SWLS | Increase |

| Goodmon et al., 2016 | Florida Southern College, USA | Pre, Post | 18 | 18 | 16 weeks | Psychology | Gratitude, kindness, forgiveness, savoring, strengths, mindfulness | Social psychology course | 20 | 20 | AHI | Increase |

| GHQ | None | |||||||||||

| SWLS | Increase | |||||||||||

| AHQ | Increase | |||||||||||

| Hammill et al., 2020 | Victoria University, Australia | Post | 37 | 37 | 4 weeks | Business | Gratitude, strengths, mindfulness | Comparator coursef | 21 | 21 | Likert scale – Happy at university | No change in intervention group vs. increase in control croup |

| Hassed et al., 2009 | Monash University, Australia | Pre, Post | 239 | 148 | 6 weeks | Medicine | Mindfulness, physical activity, stress management, meaning in life, relationships | None | – | – | WHOQOL psychological | Increase |

| Hood et al., 2021 | University of Bristol, UK | Pre, Post, 6-weeks | 135 | 119 | 12 weeks | Open unit | Gratitude, kindness, savoring, strengths, mindfulness, physical activity | Wait-list | 137 | 118 | SWEMWBS | Increase |

| ONS Life Satisfaction | None | |||||||||||

| ONS life worthwhile | No change in intervention group vs. small decrease in control group | |||||||||||

| ONS Happiness | None | |||||||||||

| Kleinman, 2014 g | James Madison University, USA | Pre, Post, 4-months | 25 | 17 | 14 weeks | Psychology | Kindness, forgiveness, strengths, mindfulness, physical activity, meaning in life, emotional skills, relationships, resilience, stress management | Other psychology course | 26 | 14 | PWBNF | None |

| SWLS | None | |||||||||||

| PANAS Positive | None | |||||||||||

| OHQ | None | |||||||||||

| WBI | Increase | |||||||||||

| R-PWB | None | |||||||||||

| Lambert et al., 2019 | Canadian University Dubai, UAE | Pre, Post, 3-months | 159 | 159 | 14 weeks | Open unit | Gratitude, forgiveness, savoring, mindfulness | ‘Not enrolled in the course’f | 108 | 108 | SPANE | None |

| SWLS | None | |||||||||||

| Flourishing scale | None | |||||||||||

| QEWB | Increase | |||||||||||

| MHC-SF | None | |||||||||||

| Lee, 2017 | School of Continuing Education of Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong | Pre, Post | 44 | 44 | 12 weeks | Professional Diploma in Applied Psychology | Gratitude, kindness, empathy, savoring, strengths, mindfulness, relationships, meaning in life | Other psychology course | 50 | 50 | SHS | Increase |

| SWLS | Increase | |||||||||||

| AHS | Increase | |||||||||||

| Lefevor et al., 2018 | Brigham Young University, USA | Pre, Post | 146 | 133 | One semesterh | Open unit | Gratitude, savoring, strengths, mindfulness | None | – | – | R-PWB | Increase |

| LOT-R | Increase | |||||||||||

| AHQ | Increasei | |||||||||||

| SHS | Increase | |||||||||||

| Maybury, 2013 | University of Maine at Farmington, USA | Pre, Post | 32 | 23 | 14 weeks | Open unit | Gratitude, strengths | None | – | – | SWLS | None |

| THS | Increase | |||||||||||

| SHS | Increase | |||||||||||

| Morgan, 2016 | University of Arkansas, USA | Pre, Post | 53 | 53 | 8 weeks | Public health | Gratitude, kindness, forgiveness, strengths, mindfulness, communication skills | Personal health and safety course | 22 | 22 | QEWB | None |

| Morton et al., 2020 | Avondale College of Higher Education, Australia | Pre, Post | 67 | 67 | 10 weeks | Open unit | Gratitude, kindness, forgiveness, mindfulness, physical, emotional skills, communication skills, engaging with the natural environment, relationships | None | – | – | SWLS | Increase |

| Powell et al., 2021 | University of Michigan, USA | Pre, Post | 42 | 38 | 15 weeks | Pharmacy | Kindness, mindfulness | None | – | – | Brief inventory of thriving | Increase only ‘Life having a sense of purpose’ item |

| Rhodes, 2017 | Walden University, USA | Pre, Post | 25 | 25 | 9 weeks | Foundational courses at a non-traditional career college | Gratitude, kindness, strengths | None | – | – | AHI | Small increase |

| SWLS | None | |||||||||||

| Smith et al., 2020 | University of New Mexico, USA | Pre, Post | 127 | 112 | 16 weeks | Psychology | Gratitude, kindness, strengths | Other psychology coursesj | 325 | 176 | PERMA profiler | Increase |

| Van Zyl and Rothmann, 2012 | North-West University, South Africa | Pre, Post, 4-months | 20 | 20 | 8 months | Industrial/Organizational psychology | Gratitude, forgiveness, savoring, strengths, mindfulness, positive visualization, relationships, communication skills | None | – | – | SWLS | Increase |

| PANAS affect balance | Increase | |||||||||||

| Young et al., 2020, Study 1 | University of Queensland, Australia | Weekly during course | 67 | 38 | 6 weeks | Psychology | Gratitude, kindness, strengths, mindfulness, positive visualization, emotional skills | None | – | – | MHC-SF | Increase |

| Young et al., 2020, Study 2 | University of Queensland, Australia | Pre, Post | 155 | 129 | 6 weeks | Psychology | Gratitude, kindness, strengths, mindfulness | None | – | – | MHC-SF | Increase |

| PANAS positive | Increase | |||||||||||

| Young et al., 2020, Study 3 | University of Queensland, Australia | Pre, Post | 105 | 55 | 6 weeks | Psychology | Gratitude, kindness, strengths, mindfulness | Other psychology course | 83 | 58 | MHC-SF | Decrease in control, no change in intervention |

| Zhang et al., 2020 | South China University of Technology, China | Pre, Post | 113 | 95 | 8 weeks | Medicine | Gratitude, forgiveness, strengths, meaning in life, emotional skills, relationships, resilience, stress management | None | – | – | THS | Increase |

| SWLS | Increase | |||||||||||

| SHS | Increase | |||||||||||

AHI, Authentic Happiness Inventory; AHQ, Approaches to Happiness Questionnaire; AHS, Adult Hope Scale; GHQ, General Happiness Questionnaire; LOT-R, Life Orientation Test-Revised; MHC-SF, Mental Health Continuum Short-Form; OHQ, Oxford Happiness Questionnaire; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; PERMA Profiler, Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment Profiler; PPIs, Positive Psychology Interventions; PWBNF, Psychological Well-Being Narrative Form; PWI, Personal Wellbeing Index; QEWB, Questionnaire for Eudemonic Well-Being; R-PWB, Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-Being; SHS, Subjective Happiness Questionnaire; SWEMWBS, Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale; SWLS, Satisfaction with Life Scale; SPANE, Scale of Positive and Negative Experience; THS, Trait Hope Scale; WBI, The Well-Being Interview; WEMWBS, Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, WHOQOL Psychological, World Health Organization Quality of Life.

aSingle item question: ‘How do you rate yourself when you think about your whole life in general?’ Responses ranged from (1) very unhappy to (5) very happy.

bOther elective courses included History of Spanish Music, Ergonomics, Ethnomusicology, Ensemble Foundations of Direction, German, English.

cStudents completed the course online in their own time, the maximum permitted time for completion was 12 weeks.

dTotal course was 18 weeks, but positive psychology component was only included for 6 weeks.

eParticipants in the control condition were asked to write about 10 things they had done that week instead of the positive psychology intervention.

fNo further details provided.

gThesis version of the study included in this review as it included a greater number of well-being measures. A shortened version was also published in an academic journal (Kleinman et al., 2014).

hLength of the semester not reported.

iA significant increase was observed in the ‘meaning’ subscale, change in the ‘pleasure’ and ‘engagement’ were trend level effects (p = 0.053).

jAlternative psychology courses included were Cognitive Psychology, Statistics, Neuropsychology, Psychology of Perception, Research Methods.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of study effects on psychological well-being by geographic location.

Thirteen studies used a within-subjects design, measuring change in wellbeing pre- and post-course. Twelve studies used a mixed-design, comparing change in wellbeing pre- and post-course in intervention and control groups. Two studies used a between-subject design, comparing psychological wellbeing post-course only in intervention and control groups.

Most studies collected psychological wellbeing outcomes at two timepoints, pre- and post-course (k = 18). Five studies collected additional follow-up timepoints varying from 6 weeks to 4 months. Two studies collected psychological wellbeing measures at each session, and two studies collected post-course timepoints only.

Participants

A total of 2,176 participants were analyzed as part of intervention groups across studies (mean = 81, SD = 71, min = 12, max = 308). However, demographics were reported inconsistently. Where participant characteristics were reported, participants tended to be young (reported mean range of 18.8–25.9) and predominantly female (reported range of 49–92%). Of studies reporting ethnicity, most students were caucasian except for two studies that reported an equal or greater number of hispanic students (Rhodes, 2017; Smith et al., 2020).

Intervention groups – positive psychology courses

Course features

Courses were embedded into a variety of programs, including open units available to all students (k = 9), Psychology (k = 10), Medicine (k = 3), Business (k = 1), Music (k = 1), Pharmacy (k = 1), Public Health (k = 1), and Foundational courses (k = 1). Courses ranged from 4 weeks to 8 months, with a median length of 12 weeks.

Positive psychology interventions

The most common positive psychology interventions taught within courses focused on character strengths (k = 21) and gratitude (k = 21). Activities related to character strengths included identifying strengths and using strengths in new ways. Gratitude activities included writing messages of gratitude to others and keeping a gratitude journal.

Eighteen studies taught activities relating to mindfulness. This involved meditation practices and mindful listening. Sixteen studies covered acts of kindness, where, most commonly, students were asked to do something nice for someone else without expecting anything in return. Eight studies included activities or readings relating to forgiveness. Most commonly, students were asked to write a letter forgiving a previous transgressor. Eight studies covered savoring, such as focusing on sensations during an enjoyable activity (e.g., eating chocolate). Five studies included components related to empathy, such as empathetic listening. Finally, five studies included physical health components, such as completing 30 min of exercise per day.

Beyond the positive psychology interventions extracted in accordance with our protocol, we identified several other topics including emotional skills training (e.g., emotional intelligence, awareness and regulation; k = 12), communication skills (e.g., conflict management; k = 8), promoting social relationships (e.g., reflecting on how one’s relationships impact wellbeing; k = 9), spirituality and meaning in life (k = 5), positive visualization (e.g., drawing a picture of a positive future; k = 3), stress management and resilience (e.g., coping strategies; k = 6), engaging with the natural environment (e.g., immersing oneself in a brightly lit natural environment; k = 2), and positive reappraisal (e.g., positively reframing stressful events, k = 2).

Control groups

Half of studies (k = 14, 52%) used a control group, none of which randomized group assignment. Ten studies compared positive psychology courses to alternative university courses; six were alternative Psychology courses, one a Personal Health and Safety course, one a Global Citizens and Citizenships course, one any elective course, and one study did not provide details of the comparison course. Two studies used the same type of course in both intervention and control groups but removed the positive psychology interventions for the control group. One study used a wait-list control group of students enrolled to take the course in the following academic semester. One study did not provide details of the nature of the comparison group. Wellbeing was analyzed in a total of 768 participants in control groups across studies (mean = 55, SD = 49, min = 12, max = 176).

Outcome measures

Psychological well-being

In total, 33 different measures of psychological wellbeing were used (Table 1). On average, studies used two measures of psychological wellbeing (Min = 1, Max = 6). The most common measure was the Satisfaction with Life Scale (k = 12). Most studies used validated measures of psychological wellbeing. However, three studies used single-item Likert or Visual Analog Scales only (Hammill et al., 2020; Bartos et al., 2021; Cheung et al., 2021). One study used ten individual measures of wellbeing to create a latent variable of ‘positive wellbeing’ (Conley et al., 2013).

Mental health difficulties

Of studies included in the review, thirteen studies also assessed the impact of positive psychology courses on mental health. Of these, an average of two measures were included per study (Min = 1, Max = 4). This included measures of depression, anxiety, stress, loneliness, and burnout (Table 2). However, there was little overlap in measures across studies.

TABLE 2.

Summarized effects of positive psychology courses on measures relating to mental health.

| Area of mental health | Study | Measure | Effect |

| Anxiety | Bartos et al., 2021 | Change in anxiety (yes/no) | None |

| Di Consiglio et al., 2021, Study 2 | Anxiety sensitivity index | None | |

| Social interaction anxiety scale | None | ||

| Social phobia scale | None | ||

| Hassed et al., 2009 | Symptom checklist revised | None | |

| Hood et al., 2021 | ONS anxiety | None | |

| Morton et al., 2020 | DASS | Decrease | |

| Zhang et al., 2020 | PROMIS | Decrease | |

| Burnout | Cheung et al., 2021 | Modified Maslach burnout inventory | Increase |

| Depression/Negative affect | Cheung et al., 2021 | Frequency of negative emotions | None |

| Conley et al., 2013 | Negative distress latent variable | None | |

| Davis, 2020 | PANAS negative | None | |

| PERMA negative emotion | None | ||

| Goodmon et al., 2016 | Center for epidemiologic studies depression questionnaire | Decrease | |

| Hassed et al., 2009 | Symptom checklist revised | Decrease | |

| Kleinman, 2014 | PANAS negative | Decrease a | |

| Morton et al., 2020 | DASS | Decrease | |

| Smith et al., 2020 | PERMA negative emotion | Decrease | |

| Zhang et al., 2020 | PROMIS | Decrease | |

| Stress | Bartos et al., 2021 | Change in stress (yes/no) | None |

| Cheung et al., 2021 | Perceived stress scale | None | |

| Conley et al., 2013 | Perceived improvements in stress scale | Decrease b | |

| Goodmon et al., 2016 | Perceived stress scale | Decrease | |

| Morton et al., 2020 | DASS | Decrease | |

| Loneliness | Davis, 2020 | PERMA loneliness | None |

| Hood et al., 2021 | ONS loneliness | Decrease | |

| UCLA 3-item loneliness scale | None | ||

| Smith et al., 2020 | PERMA loneliness | Decrease | |

| Worry | Di Consiglio et al., 2021, Study 2 | Penn state worry questionnaire | Decrease |

| Overall psychological distress | Bartos et al., 2021 | Mental emotional issues (yes/no) | None |

| Hassed et al., 2009 | Symptom checklist revised | Decrease | |

| Lefevor et al., 2018 | Outcome questionnaire-45 | Decrease |

DASS, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Scale; PERMA, Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment Profiler; ONS, Office of National Statistics.

aWeak evidence, group × time interaction effect of p = 0.051.

bRepresented by an increase in scores.

Effect on psychological wellbeing

Results are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 2. Eleven (41%) studies reported positive effects across all measures of psychological wellbeing, 12 (45%) studies reported positive findings on at least one measure of psychological wellbeing but also reported null effects, two (7%) studies reported null effects on all measures, and two (7%) studies reported negative effects.

Positive effects

Eleven studies (41%) reported consistently beneficial effects of positive psychology courses across all measures of psychological wellbeing employed. Three of these studies reported a relatively greater increase in psychological wellbeing in the intervention versus control group (Duan et al., 2014; Lee, 2017; Smith et al., 2020). One study reported a decline in emotional wellbeing in the control group versus stable levels in the intervention group, suggesting the course may have had a protective effect (Young et al., 2020).

Seven studies reported an increase in psychological wellbeing from pre- to post-course but did not include a control group comparison. Of these, two were delivered to medical students (Hassed et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2020), three to psychology students (Van Zyl and Rothmann, 2012; Young et al., 2020), and two as open units (Lefevor et al., 2018; Morton et al., 2020).

Mixed effects

Twelve studies (44%) reported at least one positive effect across measures of psychological wellbeing. However, the extent of supportive evidence varied. Providing stronger support that the course had a beneficial effect, Goodmon et al. (2016) reported increases in life satisfaction and two measures of happiness relative to a control group, but did not find an effect for a third measure of happiness. Similarly, Maybury (2013) reported increases in hope and happiness, but not life satisfaction.

Providing weaker evidence of beneficial effects, Davis (2020) found evidence of increased positive mood and wellbeing measured using Henrique’s 10-item wellbeing scale, but no evidence of positive effects on three other measures of wellbeing. Similarly, Hood et al. (2021) reported increased wellbeing using the Shortened Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) in students completing an open-unit wellbeing course versus no change in a wait-list control group. Additionally, whereas the wait-list control group showed a decline in feelings that life was worthwhile, no change was found in the intervention group. However, no evidence of beneficial effects were reported for measures of happiness or life satisfaction. Kleinman (2014) reported increased wellbeing when measured using a structured clinical assessment (the wellbeing interview), but did not find evidence in five self-report measures of wellbeing. Arasil et al. (2020) used five measures of wellbeing, reporting only positive effects in a single-item Likert scale question developed for the study, but not for the four validated measures of wellbeing. Conley et al. (2013) found evidence of greater perceived wellbeing but only when measured post-course. No evidence of a beneficial effect was found for a latent measure of ‘positive wellbeing’ collected pre- and post-course. Lambert et al. (2019) reported increased eudemonic wellbeing but no effects for four other measures. Di Consiglio et al. (2021) reported only beneficial effects on a single subscale of Ryff’s Psychological Wellbeing scale across two studies. Rhodes (2017) reported only weak evidence of a change in happiness and no change in life satisfaction. Lastly, in a pilot study of pharmacy students, Powell et al. (2021) found beneficial effects on only a single item of the Brief Inventory of Thriving (‘Life having a sense of purpose’).

Null and negative effects

Two studies (7%) reported no evidence of a difference in wellbeing between intervention and control groups (Morgan, 2016; Bartos et al., 2021). Two studies (7%) reported negative effects. Business students that completed the positive psychology course showed lower levels of happiness compared to the control group (Hammill et al., 2020). Medicine students reported a decline in the frequency of positive emotions throughout the course (Cheung et al., 2021).

Long term effects

Five studies examined psychological wellbeing at follow-up timepoints. Duan et al. (2014) found that the participants in the intervention group continued to show greater life satisfaction versus controls. Hood et al. (2021) reported that psychological wellbeing effects were maintained 6-weeks post-course, but benefits were no longer found for perceptions that life was worthwhile. Van Zyl and Rothmann (2012) and Lambert et al. (2019) found that wellbeing increased from pre-course to three and four month follow-ups respectively. However, for Lambert et al. (2019) these analyses were conducted in the intervention group only, limiting conclusions. Finally, Kleinman (2014) reported no differences between intervention and control groups at 4-month follow-up. However, an abbreviated battery of measures was completed, none of which showed an effect post-course.

Effect on mental health

Most studies investigating mental health reported beneficial effects on at least one measure (k = 10; 77%) (Hassed et al., 2009; Conley et al., 2013; Kleinman, 2014; Goodmon et al., 2016; Lefevor et al., 2018; Morton et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Di Consiglio et al., 2021, Study 2; Hood et al., 2021). However, when examining individual areas of mental health, findings were more mixed (Table 2). Positive effects were observed in 2/6 (33%) studies examining anxiety (Morton et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), 6/9 (66%) studies examining depression/negative affect (Hassed et al., 2009; Kleinman, 2014; Goodmon et al., 2016; Morton et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), and 3/5 (60%) studies examining stress (Conley et al., 2013; Goodmon et al., 2016; Morton et al., 2020). Two of three studies reported beneficial effects on loneliness (Smith et al., 2020; Hood et al., 2021). However, in one of these studies, there was disagreement between the different measures of loneliness; although a decline in loneliness was observed in the intervention group using the single-item ONS measures, no change was found using the UCLA loneliness scale (Hood et al., 2021). One study reported negative effects on mental health, with medical students reporting increased burnout throughout the course (Cheung et al., 2021).

Characteristics of courses with a positive effect on psychological wellbeing

Benefits to psychological wellbeing were observed across studies with varying characteristics, including participants’ degree programs, lengths of courses, and positive psychology interventions taught. We therefore did not identify specific characteristics of courses that may be linked to positive effects.

Risk of bias

Figure 3 summarizes judgments of risk for each domain of bias. Individual judgments per study are available in Supplementary Table 2. Across studies, overall risk of bias was moderate (k = 8; 30%) or serious (k = 19; 70%). Most studies were at high risk of bias as they did not adjust for potential confounding effects in statistical analyses, such as imbalanced characteristics between groups. Studies were also at moderate or serious risk of bias in the selection of reported results, with only one study pre-registering statistical analyses (Hood et al., 2021). However, all studies included in the review followed the intended intervention. Additionally, bias in the classification of interventions and measurement of outcomes was mainly low.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of risk of bias judgments, illustrating the proportion of studies that were judged to be at low, moderate, or serious risk of bias (or whether sufficient information was not available for a judgment) for individual domains of bias and overall risk.

Discussion

There is increasing concern over university students’ psychological wellbeing (Auerbach et al., 2018; Neaves and Hewitt, 2021). Positive psychology courses embedded into university degree programs may help address this problem. Such courses have received positive media attention (e.g., Shimer, 2018), but to date evidence of their effectiveness has not been systematically established. We therefore conducted a systematic review of positive psychology courses embedded into university degree programs.

We found evidence that the majority of studies evaluating such courses reported beneficial effects on student psychological wellbeing, including increased levels of happiness, life satisfaction, and quality of life. Of the 27 studies included in this review, 23 (85%) studies reported at least one positive effect, of which 11 reported consistently positive findings across all psychological wellbeing measures employed. However, risk of bias was high across studies. Findings are therefore not conclusive but suggest that positive psychology courses delivered within degree programs may be one tool to promote psychological wellbeing in university students.

Thirteen studies also examined the impact of courses on measures relating to mental health difficulties. Although psychological wellbeing courses are not intended as a treatment for mental health disorders, there was some evidence across this subset of studies that courses were beneficial in reducing mental health difficulties including depression, negative affect, and stress. Implementing courses into university curriculum may be valuable in supporting students with mental health difficulties until services designed to treat these problems are available.

However, it must be acknowledged that there was also evidence of null and negative effects of courses on wellbeing. Forty-four percent of studies reported mixed findings across different measures of wellbeing used. Two studies reported null effects, and of most concern, two studies reported negative effects on student wellbeing. One study found that business students reported lower levels of happiness compared to controls (Hammill et al., 2020). However, this study used only a single-item Likert scale to measure happiness and did not provide details of the nature of the comparator group. Additionally, one study found that medicine students reported reduced positive emotions and increased burnout (Cheung et al., 2021). As this study lacked a control group this effect may be attributed to the wider stressors of the degree program. However, other courses in medicine students reported positive effects suggesting that positive psychology courses can be effective in similar degree programs (Hassed et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2020).

It is possible that differences in findings between studies was partly attributable to substantial variation across courses and study designs. There was no positive psychology intervention that was implemented across all courses, although character strengths and gratitude were most common. Courses varied in length, ranging from as brief as 4 weeks to as long as 8 months. Additionally, there was also inconsistency in measures used to evaluate psychological wellbeing. Although most studies used validated self-report measures, some studies focused on single-item measures developed for the study, making comparisons problematic. Due to these variations it is difficult to identify aspects of courses that may be most beneficial or detrimental to participants, or whether effects may be more sensitively detected using certain measures.

Furthermore, study quality was generally poor with most studies at high risk of bias. In particular, studies were at moderate or high risk of bias for selective reporting of results. Only one study identified in this review pre-registered hypotheses or statistical analyses (Hood et al., 2021), and there was also inconsistency between reported outcomes in methods and results, increasing the likelihood of false-positive findings (Simmons et al., 2011). Additionally, most studies did not control for potential confounding. The beneficial effects of courses highlighted in this review may therefore be at least partly attributable to poor research practices in this field.

Future research and recommendations

The findings from our review raise several questions regarding the use of positive psychology courses within student populations. Firstly, the magnitude of effects is unclear. It is possible that whilst these courses have a statistically significant effect on psychological wellbeing, these changes are small and not perceived as meaningful by students (Hobbs et al., 2021). Future studies should ensure outcome data are fully reported, or where possible data is published open access to allow meta-analysis of effects. This would also allow the use of meta-regression to identify which aspects of courses are most beneficial to student wellbeing.

Secondly, it is currently unclear as to what extent positive findings may be attributable to poor quality research in this area. Future studies within this field should implement rigorous research practices to validate the reported beneficial effects of positive psychology courses. In light of our findings, we recommend researchers pay greater consideration to potential confounding effects, as well as pre-registering hypotheses and statistical analyses to ensure validity of findings.

Additionally, we identified that there is currently large variation in the type of positive psychology courses on offer across universities, making comparisons problematic. It is likely that the quality of courses and the type of positive psychology interventions on offer moderate effects on student wellbeing. Future reviews in this field should consider including a measure of the quality of courses to evaluate this possibility.

We also identified substantial variation in study designs. One source of variation that would be relatively easy to address in future research is identifying a consistent self-report measure of wellbeing to use across studies. This would enable clearer comparisons of course effectiveness. One potential candidate may be the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985) as this was the most widely used measure across studies, has good psychometric properties (Pavot et al., 1991), and is relatively brief.

Finally, it is somewhat unclear how long beneficial effects of courses on psychological wellbeing are sustained for. Whilst four studies found some evidence that effects were sustained approximately 4 months post-course, most studies did not conduct follow-ups. It would be helpful for studies to implement long-term follow-ups with participants, using a short self-report measure, to help estimate how long effects of courses may be maintained for. In the future, this may aid the development of brief ‘top-up’ interventions to further sustain potential beneficial effects of courses on wellbeing.

Strengths and limitations

Despite the growing popularity of university positive psychology courses (Shimer, 2018), this is the first systematic review on the effects of these courses on psychological wellbeing. Taking a rigorous approach, from approximately 3,000 unique records we identified 27 studies in this field, documenting effects for each measure of wellbeing employed.

However, this review was limited in its focus on quantitative measures of wellbeing. Whilst this allowed us to compare quantified effects on wellbeing, we lack a detailed understanding of students’ experiences of participating in such courses, which may be better obtained using a qualitative approach.

Additionally, despite focusing on quantitative measures we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis due to studies not reporting sufficient data. We are therefore not able to comment on the magnitude of effects or conduct meta-regressions that may allow us to more precisely identify beneficial course aspects.

We did not extract data on the quality of courses on offer or student engagement. It is likely that these factors play a role in the effect of courses on student wellbeing. Future reviews in this field should consider including this information to determine where courses may be most beneficial for students.

Finally, we combined findings using different measures of wellbeing. Our findings are therefore based on the assumption that effects from different measures are comparable despite measuring distinctive facets of wellbeing. However, as this is the first systematic review in this field, it was not possible to anticipate which wellbeing measure would be most appropriate to extract. Future reviews in this field focusing on specific measures would be helpful in confirming our findings.

Conclusion

From systematic review of current literature, we found that most studies report at least one positive effect of positive psychology courses embedded within university degree programs on student psychological wellbeing. However, a small number of studies report null or negative effects. A lack of consistency across courses on offer makes it difficult to determine which aspects of courses are most beneficial for students. Furthermore, study quality was relatively poor, increasing the potential for false-positive findings and potential confounding. Adoption of rigorous research practices, including pre-registration and open-access publication of data, is required to confirm the positive effects of positive psychology courses embedded into university degree programs on student psychological wellbeing.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CH, BH, and SJ conceptualized the study. CH wrote the review protocol, which was reviewed and edited by JA, BH, and SJ. CH conducted the database search. CH and JA screened the studies, extracted the data, and assessed risk of bias. SJ acted as a third reviewer and resolving disagreements. CH wrote the original draft of this manuscript, which was reviewed and edited by JA, BH, and SJ. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by a grant awarded jointly by the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute, University of Bristol and the Rosetrees Trust, the Bristol Alumni Association, and the Wellcome Trust (204813/Z/16/Z).

Conflict of interest

Author BH and SJ teach a positive psychology course at the University of Bristol and authored one of the manuscripts included in this review. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1023140/full#supplementary-material

References

- Arasil A. B. S., Turan F., Metin B., Ertas H. S., Tarhan N. (2020). Positive Psychology Course: A Way to Improve Well-Being. J. Educ. Futur. 17, 15–23. 10.30786/jef.591777 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach R. P., Mortier P., Bruffaerts R., Alonso J., Benjet C., Cuijpers P., et al. (2018). WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 127 623–638. 10.1037/abn0000362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Leigh C. (2022). Happiness (university) courses (economics of/science of). Available online at: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1kICp8Equ4Ak7zOfBfyYW9y_tuWjOkW0yAgOYoJIOvVU/edit#gid=0 (Accessed April 6, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Bartos L. J., Funes M. J., Ouellet M., Posadas M. P., Krägeloh C. (2021). Developing Resilience During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Yoga and Mindfulness for the Well-Being of Student Musicians in Spain. Front. Psychol. 12:642992. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.642992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewick B., Koutsopouloub G., Miles J., Slaad E., Barkham M. (2010). Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well-being as they progress through university. Stud. High. Educ. 35 633–645. 10.1080/03075070903216643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower D. G., Oswald A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle?. Soc. Sci. Med. 66 1733–1749. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolier L., Haverman M., Westerhof G. J., Riper H., Smit F., Bohlmeijer E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 13:119. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P. (2020). Higher education student numbers: Briefing Paper. Available online at: www.parliament.uk/commons-library%7Cintranet.parliament.uk/commons-library%7Cpapers@parliament.uk%7C@commonslibrary (accessed on Nov 11, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Bruffaerts R., Mortier P., Kiekens G., Auerbach R. P., Cuijpers P., Demyttenaere K., et al. (2018). Mental health problems in college freshmen: Prevalence and academic functioning. J. Affect. Disord. 225 97–103. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A., Cullen K., Keeney C., Canning C., Mooney O., Chinseallaigh E., et al. (2020). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 16 1–21. 10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung E. O., Kwok I., Ludwig A. B., Burton W., Wang X., Basti N., et al. (2021). Development of a Positive Psychology Program (LAVENDER) for Preserving Medical Student Well-being: A Single-Arm Pilot Study. Glob. Adv. Heal. Med. 10:2164956120988481. 10.1177/2164956120988481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley C. S., Travers L. V., Bryant F. B. (2013). Promoting psychosocial adjustment and stress management in first-year college students: The benefits of engagement in a psychosocial wellness seminar. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 61 75–86. 10.1080/07448481.2012.754757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry O. S., Rowland L. A., Van Lissa C. J., Zlotowitz S., McAlaney J., Whitehouse H. (2018). Happy to help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of performing acts of kindness on the well-being of the actor. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 76 320–329. 10.1016/j.jesp.2018.02.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J. (2020). A General Education Course Designed to Cultivate College Student Well-Being. Ph.D thesis. Harrisonburg, VA: James Madison University. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson A. F., Brown W. W., Anderson J., Datta B., Donald J. N., Hong K., et al. (2020). Mindfulness-Based Interventions for University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Appl. Psychol. Heal. Well Being 12 384–410. 10.1111/aphw.12188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci E. L., Ryan R. M. (2008). Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. J. Happiness Stud. 9 1–11. 10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Consiglio M., Fabrizi G., Conversi D., La Torre G., Pascucci T., Lombardo C., et al. (2021). Effectiveness of NoiBene: A Web-based programme to promote psychological well-being and prevent psychological distress in university students. Appl. Psychol. Heal. Well Being 13 317–340. 10.1111/aphw.12251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Emmons R. A., Larsem R. J., Griffin S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49 71–75. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan W. J., Ho S. M. Y., Tang X. Q., Li T. T., Zhang Y. H. (2014). Character Strength-Based Intervention to Promote Satisfaction with Life in the Chinese University Context. J. Happiness Stud. 15 1347–1361. 10.1007/s10902-013-9479-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos N. L., Krahn H. J., Johnson M. D., Lachman M. E. (2020). The U Shape of Happiness Across the Life Course: Expanding the Discussion. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 15 898–912. 10.1177/1745691620902428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodmon L. B., Middleditch A. M., Childs B., Pietrasiuk S. E. (2016). Positive Psychology Course and Its Relationship to Well-Being, Depression, and Stress. Teach. Psychol. 43 232–237. 10.1177/0098628316649482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammill J., Nguyen T., Henderson F. (2020). Student engagement: The impact of positive psychology interventions on students. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 23:146978742095058. 10.1177/1469787420950589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassed C., De Lisle S., Sullivan G., Pier C. (2009). Enhancing the health of medical students: Outcomes of an integrated mindfulness and lifestyle program. Adv. Heal. Sci. Educ. 14 387–398. 10.1007/s10459-008-9125-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth C. F., Bilgrav L., Frandsen L. S., Overgaard C., Torp-Pedersen C., Nielsen B., et al. (2016). Mental health and school dropout across educational levels and genders: A 4.8-year follow-up study. BMC Public Health 16:976. 10.1186/s12889-016-3622-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs C., Jelbert S., Santos L. R., Hood B. (2021). Evaluation of a credit-bearing online administered happiness course on undergraduates’ mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 17:e0263514. 10.1371/journal.pone.0263514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood B., Jelbert S., Santos L. R. (2021). Benefits of a psychoeducational happiness course on university student mental well-being both before and during a Covid-19 lockdown. Heal. Psychol. Open 8:2055102921999291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell A. J., Passmore H. A. (2019). Acceptance and Commitment Training (ACT) as a Positive Psychological Intervention: A Systematic Review and Initial Meta-analysis Regarding ACT’s Role in Well-Being Promotion Among University Students. J. Happiness Stud. 20 1995–2010. 10.1007/s10902-018-0027-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Merikangas K. R., Walters E. E. (2005). Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62 593–602. 10.1001/ARCHPSYC.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman K. E. (2014). A unified approach to well-being: The development and impact of an undergraduate course. Ph.D thesis. Harrisonburg, VA: James Madison University. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman K. E., Asselin C., Henriques G. (2014). Positive Consequences: The Impact of an Undergraduate Course on Positive Psychology. Psychology 05 2033–2045. 10.4236/psych.2014.518206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurki M., Sonja G., Kaisa M., Lotta L., Terhi L., Susanna H. Y. S., et al. (2021). Digital mental health literacy -program for the first-year medical students’ wellbeing: A one group quasi-experimental study. BMC Med. Educ. 21:563. 10.1186/S12909-021-02990-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert L., Passmore H. A., Joshanloo M. (2019). A Positive Psychology Intervention Program in a Culturally-Diverse University: Boosting Happiness and Reducing Fear. J. Happiness Stud. 20 1141–1162. 10.1007/s10902-018-9993-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. P. (2017). The impact of a positive psychology course on well-being among adults in Hong Kong. Ph.D thesis. Ann Arbor: ProQuest. [Google Scholar]

- Lefevor G. T., Jensen D., Jones P., Janis R., Hsieh C. H. (2018). An Undergraduate Positive Psychology Course as Prevention and Outreach. Psyarxiv [Preprint]. 10.31234/osf.io/r52wg [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis G., McCloud T., Callender C. (2021). Higher education and mental health: Analyses of the LSYPE cohorts. Washington, DC: Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Limarutti A., Maier M. J., Mir E., Gebhard D. (2021). Pick the Freshmen Up for a “Healthy Study Start” Evaluation of a Health Promoting Onboarding Program for First Year Students at the Carinthia University of Applied Sciences, Austria. Front. Public Heal. 9:652998. 10.3389/FPUBH.2021.652998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipson S. K., Eisenberg D. (2018). Mental health and academic attitudes and expectations in university populations: Results from the healthy minds study. J. Ment. Heal. 27 205–213. 10.1080/09638237.2017.1417567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann F., Wang J., Pearce E., Ma R., Schlief M., Lloyd-Evans B., et al. (2022). Loneliness and the onset of new mental health problems in the general population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1 1–18. 10.1007/S00127-022-02261-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maybury K. K. (2013). The Influence of a Positive Psychology Course on Student Well-Being. Teach. Psychol. 40 62–65. 10.1177/0098628312465868 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A. J. (2016). The efficacy of an eight-week undergraduate course in resilience. Ph.D thesis. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas. [Google Scholar]

- Mortier P., Cuijpers P., Kiekens G., Auerbach R. P., Demyttenaere K., Green J. G., et al. (2018). The prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among college students: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 48 554–565. 10.1017/S0033291717002215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton D. P., Hinze J., Craig B., Herman W., Kent L., Beamish P., et al. (2020). A Multimodal Intervention for Improving the Mental Health and Emotional Well-being of College Students. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 14 216–224. 10.1177/1559827617733941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neaves J., Hewitt R. (2021). Student Academic Experience Survey. York: Advance HE and Higher Education Policy Institute. Available online at: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/SAES_2021_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W., Diener E., Colvin C. R., Sandvik E. (1991). Further Validation of the Satisfaction With Life Scale; Evidence for the Cross-Method Convergence of Well-Being Measures. J. Pers. Assess. 57 149–161. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell K. M., Mason N. A., Gayar L., Marshall V., Bostwick J. R. (2021). Impact of a pilot elective course to address student pharmacist well-being. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 13 1464–1470. 10.1016/j.cptl.2021.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan D., Swain N., Vella-Brodrick D. A. (2012). Character Strengths Interventions: Building on What We Know for Improved Outcomes. J. Happiness Stud. 13 1145–1163. 10.1007/s10902-011-9311-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randstad (2020). Student Wellbeing in Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.randstad.co.uk/s3fs-media/uk/public/2020-01/mentalhealthreport-StudentSupport-Softcopy_1.pdf (accessed February 16, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes R. H. (2017). Evaluating positive psychology curriculum among nontraditional students in a foundational course. Ph.D thesis. Minneapolis, MN: Walden University. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M. E. P., Ernst R. M., Gillham J., Reivich K., Linkins M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Rev. Educ. 35 293–311. 10.1080/03054980902934563 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimer D. (2018). Yale’s Most Popular Class Ever: Happiness. New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/26/nyregion/at-yale-class-on-happiness-draws-huge-crowd-laurie-santos.html (accessed February 16, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Simmons J. P., Nelson L. D., Simonsohn U. (2011). False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychol. Sci. 22 1359–1366. 10.1177/0956797611417632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. W., Ford C. G., Erickson K., Guzman A. (2020). The Effects of a Character Strength Focused Positive Psychology Course on Undergraduate Happiness and Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 22 343–362. 10.1007/s10902-020-00233-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne J. A., Hernán M. A., Reeves B. C., Savović J., Berkman N. D., Viswanathan M., et al. (2016). ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 355:i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejada-Gallardo C., Blasco-Belled A., Torrelles-Nadal C., Alsinet C. (2020). Effects of School-based Multicomponent Positive Psychology Interventions on Well-being and Distress in Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 49 1943–1960. 10.1007/s10964-020-01289-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zyl L. E., Rothmann S. (2012). Beyond smiling: The evaluation of a positive psychological intervention aimed at student happiness. J. Psychol. Afr. 22 369–384. [Google Scholar]

- Waters L. (2011). A review of school-based positive psychology interventions. Aust. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 28 75–90. 10.1375/aedp.28.2.75 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White C. A., Uttl B., Holder M. D. (2019). Meta-analyses of positive psychology interventions: The effects are much smaller than previously reported. PLoS One 14:e0216588. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0216588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood A. M., Froh J. J., Geraghty A. W. A. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30 890–905. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T., Macinnes S., Jarden A., Colla R. (2020). The impact of a wellbeing program imbedded in university classes: The importance of valuing happiness, baseline wellbeing and practice frequency. Stud. High. Educ. 47 1–20. 10.1080/03075079.2020.1793932 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. Q., Zhang B. S., Wang M. D. (2020). Application of a classroom-based positive psychology education course for Chinese medical students to increase their psychological well-being: A pilot study. BMC Med. Educ. 20:323. 10.1186/s12909-020-02232-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.