Abstract

Purpose

The effect of high arterial oxygen levels and supplemental oxygen administration on outcomes in traumatic brain injury (TBI) is debated, and data from large cohorts of TBI patients are limited. We investigated whether exposure to high blood oxygen levels and high oxygen supplementation is independently associated with outcomes in TBI patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and undergoing mechanical ventilation.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of two multicenter, prospective, observational, cohort studies performed in Europe and Australia. In TBI patients admitted to ICU, we describe the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) and the oxygen inspired fraction (FiO2). We explored the association between high PaO2 and FiO2 levels within the first week with clinical outcomes. Furthermore, in the CENTER-TBI cohort, we investigate whether PaO2 and FiO2 levels may have differential relationships with outcome in the presence of varying levels of brain injury severity (as quantified by levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in blood samples obtained within 24 h of injury).

Results

The analysis included 1084 patients (11,577 measurements) in the CENTER-TBI cohort, of whom 55% had an unfavorable outcome, and 26% died at a 6-month follow-up. Median PaO2 ranged from 93 to 166 mmHg. Exposure to higher PaO2 and FiO2 in the first seven days after ICU admission was independently associated with a higher mortality rate. A trend of a higher mortality rate was partially confirmed in the OzENTER-TBI cohort (n = 159). GFAP was independently associated with mortality and functional neurologic outcome at follow-up, but it did not modulate the outcome impact of high PaO2 and FiO2 levels, which remained independently associated with 6-month mortality.

Conclusions

In two large prospective multicenter cohorts of critically ill patients with TBI, levels of PaO2 and FiO2 varied widely across centers during the first seven days after ICU admission. Exposure to high arterial blood oxygen or high supplemental oxygen was independently associated with 6-month mortality in the CENTER-TBI cohort, and the severity of brain injury did not modulate this relationship. Due to the limited sample size, the findings were not wholly validated in the external OzENTER-TBI cohort. We cannot exclude the possibility that the worse outcomes associated with higher PaO2 were due to use of higher FiO2 in patients with more severe injury or physiological compromise. Further, these findings may not apply to patients in whom FiO2 and PaO2 are titrated to brain tissue oxygen monitoring (PbtO2) levels. However, at minimum, these findings support the need for caution with oxygen therapy in TBI, particularly since titration of supplemental oxygen is immediately applicable at the bedside.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00134-022-06884-x.

Keywords: PaO2, FiO2, Traumatic brain injury, GOSE, Mortality, GFAP

Take-home message

| In two large prospective multicenter cohorts of traumatic brain injured patients, arterial and supplemental oxygen levels varied widely across centers during the first seven days after admission to the intensive care unit. |

| Exposure to high arterial blood oxygen or high supplemental oxygen—a therapeutic gas immediately titratable at the bedside—was independently associated with 6-month mortality, regardless of brain injury severity. |

Introduction

In patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI), hypoxemia is a major predictor of hospital and 6-month mortality [1]. Oxygen supplementation aims to reverse tissue hypoxia and, thus, improve cell viability, organ function, and survival in critically ill patients [2]. However, this may lead to administering more oxygen than needed to patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) [3].

While hyperbaric oxygen is known to be neurotoxic [4], it is not clear whether high normobaric oxygen levels may play a detrimental role in the brain [5]. Hyperoxia, i.e., high inspiratory oxygen fraction, may be associated with excitotoxicity in severe TBI [6]. Furthermore, hyperoxemia, i.e., high blood oxygen partial pressure levels, may potentially worsen organ injury and impact the case fatality rate of critically ill patients with TBI [7, 8]. Therefore, not only too low but even extreme hyperoxemia might cause injury in TBI patients, as David et al. showed [9]. Data on more than 36,000 mixed ICU patients mechanically ventilated with early arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) suggested an independent U-shape association with hospital mortality [10]. A recent metanalysis of 32 studies in acute brain-damaged patients highlighted that hyperoxemia, differently defined across studies, was associated with an increased risk of poor neurological outcomes [11]. Patients with a poor neurological outcome also had a significantly higher maximum PaO2 and mean PaO2. These associations were present, especially in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage and ischemic stroke, but not in traumatic brain injured.

Currently, there is no evidence to support the role of hyperoxemia or hyperoxia in a large real-world dataset of critically ill patients admitted to ICU with severe TBI [12–14].

Therefore, we described variability across centers in the blood oxygen levels (i.e., PaO2) and oxygen supplementation distributions (i.e., inspiratory oxygen fraction, FiO2) and investigated whether high PaO2 and FiO2 levels are associated with worse 6-month outcomes. We validated our findings in the multicenter Australian OzENTER-TBI database [15]. Finally, we explored whether PaO2 and FiO2 levels may contribute differently to outcomes in the presence of increasing levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a biomarker of brain injury severity.

The aims of this study are to:

Describe the values and the differences in PaO2 and FiO2 in the first week from ICU admission in mechanically ventilated TBI patients across centers in CENTER-TBI;

assess whether high levels of PaO2 or FiO2 are independently associated with 6-month mortality and unfavorable neurologic outcome in CENTER-TBI;

evaluate whether the impact of high levels of oxygen exposure (PaO2) or high levels of supplemental oxygen (FiO2) on 6-month outcome could be worsened by increasing brain injury severity, as assessed by acute (first 24 h) serum levels of GFAP in the CENTER-TBI cohort.

All these objectives (except the last one) were subsequently validated in an external cohort of patients with traumatic brain injury from OzENTER-TBI. Hypotheses of the current analyses were that exposure to high oxygen and FiO2 levels in TBI patients mechanically ventilated and admitted to ICU may promote brain injury and have a negative impact on both functional neurological disability and survival.

Methods

Study design and patients

The Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness in Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI study, registered at clinicaltrials.gov NCT02210221) is a longitudinal, prospective data collection from TBI patients across 65 centers in Europe between December 2014 and December 2017. The design and the results of the screening and enrollment process have been previously described [12, 13]. The Australia–Europe NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury OzENTER-TBI Study was conducted in two designated adult major trauma centers in Victoria, Australia, between February 2015 and March 2017 [15]. The Medical Ethics Committees approved both studies in all participating centers, and informed consent was obtained according to local regulations (https://www.center-tbi. eu/project/ethical-approval). Therefore, the studies have been performed per the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

In the OzENTER-TBI Study, patients or families were allowed to opt out of data collection. OzENTER-TBI was used as an external validation cohort.

Before starting the analysis, this project on PaO2 management was preregistered on the CENTER-TBI proposal platform and approved by the CENTER-TBI proposal review committee.

We included all patients in the CENTER-TBI Core study who had:

a TBI necessitating ICU admission,

tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation,

at least two PaO2 measurements in the first seven days.

These inclusion criteria were also applied to select patients from the OzENTER-TBI study for the validation cohort.

This report complies with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Data collection and definitions

Detailed information on data collection is available on the study website (https://www.center-tbi.eu/data/dictionary). The daily lowest and highest PaO2 and FiO2 values from arterial blood gases—that were collected as per the case report form—were evaluated in this study. Specifically, we investigated the role of variables representing different aspects of arterial oxygen levels and supplemental oxygen administration during the first week of ICU admission, including:

The highest PaO2 (PaO2max) and FiO2 (FiO2max) exposures.

The mean of the highest daily PaO2 (PaO2mean) and FiO2 (FiO2mean).

The mean of the swings of PaO2 (ΔPaO2mean) and of FiO2 (ΔFiO2mean). The swings were calculated daily as the difference between the highest and the lowest PaO2 and FiO2. They represent the average day-to-day variability of PaO2 and FiO2.

Mortality and functional neurological outcome measured as the 8-point Extended Glasgow Outcome Score (GOSE) were assessed six months post-injury. An unfavorable outcome was defined as GOSE ≤ 4 (i.e., low and upper severe disability, vegetative state, or dead), including both poor functional outcome and mortality. All responses were obtained by trained study personnel—blinded to the PaO2 and FiO2 data—from patients or from a proxy (where impaired cognitive capacity prevented patient interview), during a face-to-face visit, by telephone interview, or by postal questionnaire around six months after injury [16].

In CENTER-TBI, the severity of brain injury, traditionally evaluated with clinical and neuroradiologic elements, was also gauged by serum brain injury biomarkers. For this study, a decision was made to use GFAP, a glial cytoskeletal protein, as a proxy measure of brain injury severity. GFAP was the brain injury biomarker with the highest discriminative performance on computed tomography (CT) brain injury [17], and it is strongly associated with mortality and long-term outcomes after injury [18, 19]. GFAP within 24 h after trauma was quantified by an ultrasensitive immunoassay using digital array technology (Single Molecule Arrays, SiMoA)-based assay (Quanterix Corp., Lexington, MA).

Statistical methods

Patient characteristics were described by medians (interquartile range, IQR) or means (standard deviations, SD) as appropriate and counts or proportions. The role of PaO2max, FiO2max, PaO2mean, FiO2mean or ΔPaO2mean, ΔFiO2mean (one at a time) on 6-month mortality and unfavorable neurological outcome was evaluated through mixed-effect logistic regression models, adjusting for the IMPACT core covariates (age, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) motor score and pupillary reactivity) and injury severity score (ISS), with the center as a random effect. The assumption of linearity of the effect for continuous variables was evaluated using splines, and the results of the models were reported as odds ratios (OR) along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). To simplify the clinical interpretation of the OR of the exposure variables, PaO2 and FiO2 increases were referred to 10 mmHg and 0.1 each, respectively. Then, we enriched the models, including GFAP, which was log-transformed to satisfy the linearity assumption. We also investigated a potential interaction between GFAP and the six variables representing the oxygen status (one at a time) through a flexible approach based on restricted cubic splines and tensor-product splines. The final models were selected using standard statistical performance measures such as Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) and likelihood ratio tests for non-nested and nested models. Finally, we used data from the OzENTER-TBI cohort to validate our findings through the same modeling approach used for CENTER-TBI. However, here we omitted the random term for centers, while including the only two centers in the study as a dummy variable. Analyses were done on complete cases and using the MICE algorithm for multiple imputations of missing data (ten imputed datasets). Tests were performed two-sided with a significance alpha level of 5%. To protect from the risk of alpha inflation in testing the effect of arterial oxygen levels and supplemental oxygen administration on outcomes, we also adjusted the p values in the models according to the approach of Benjamini–Hochberg. All analyses were conducted using R statistical software (version 4.03).

Results

Of the 4509 patients included in the CENTER-TBI dataset, 2138 subjects were admitted to ICU and, among these, 1084 (median age was 49 [29–65], and 75% male) from 51 centers fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Supplemental Fig. 1). Half of the population experienced thoracic trauma, which in 41.5% of the cases was major.

All 198 patients included in the OzENTER-TBI dataset were admitted to ICU and, among these, 159 fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Supplemental Figure 1). In OzENTER-TBI, the median age was 39 [24–65], and 77% of the population was male. Almost 55% of the population experienced thoracic trauma, which in 46.5% of the cases was severe or critical. A comprehensive description of the population of the CENTER-TBI and OzENTER-TBI study is reported in Table 1. Patient characteristics stratified by 6-month mortality are described in Supplemental Table 1 (CENTER-TBI) and Supplemental Table 2 (OzENTER-TBI). We focused on the highest PaO2 and FiO2 daily levels in the current analysis in both cohorts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study cohorts from CENTER-TBI and OzENTER-TBI

| Variable | Level | CENTER-TBI (N = 1084) | OzENTER-TBI (N = 159) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age, median [IQR] | 49 [29–65] | 39 [24–65] | |

| Sex, n (%) | Female | 270 (25) | 37 (23) |

| Male | 814 (75) | 122 (77) | |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Hypotension, n (%) | No | 843 (77.9) | 116 (73) |

| Yes | 239 (22.1) | 43 (27) | |

| NA (n) | 2 | 0 | |

| Hypoxia, n (%) | No | 1030 (95) | 157 (98.7) |

| Yes | 54 (5) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Injury Severity Score, median [IQR] | 34 [25–45] | 29 [25–38] | |

| NA (n) | 3 | 0 | |

| pH, median [IQR] | Lowest | 7.34 [7.29–7.39] | 7.33 [7.29–7.37] |

| NA (n) | 20 | 0 | |

| Highest | 7.43 [7.39–7.47] | 7.41 [7.38–7.45] | |

| NA (n) | 6 | 0 | |

| Neurological presentation | |||

| Pupillary reactivity, n (%) | Both reactive | 790 (72.9) | 119 (74.8) |

| One reactive | 87 (8) | 11 (7) | |

| Both unreactive | 157 (14.5) | 25 (15.7) | |

| NA | 50 (4.6) | 4 (2.5) | |

| GCS Motor Score, n (%) | Localizes/obeys | 419 (38.7) | 33 (20.7) |

| None/extension | 493 (45.5) | 117 (73.6) | |

| Any flexion | 151 (13.9) | 8 (5) | |

| NA | 21 (1.9) | 1 (0.7) | |

| GCS score, n (%) | GCS > 8 | 370 (34.1) | 58 (36.5) |

| GCS ≤ 8 | 657 (60.6) | 97 (61) | |

| NA | 57 (5.3) | 4 (2.5) | |

| ICP at ICU admission, median [IQR] | 8 [4–14] | 11 [7–15] | |

| NA (n) | 521 | 108 | |

| Mean ICP, median [IQR] | 11 [6–15] | 11 [8–15] | |

| NA (n) | 521 | 108 | |

| Brain injury severity | |||

| Marshall CT Classification, median [IQR] | 3 [2–6] | 2 [2–6] | |

| NA (n) | 105 | 21 | |

| GFAP, median [IQR] | ng/mL | 20.5 [7–50.8] | / |

| NA (n) | 198 | 159 | |

| Oxygenation | |||

| Day 1 PaO2overall, mean (SD) | mmHg | 207.17 (99.91) | 328.18 (144.46) |

| PaO2mean, mean (SD) | mmHg | 155.79 (46.93) | 197.79 (73.79) |

| PaO2max, mean (SD) | mmHg | 230.92 (102.95) | 356.01 (134.47) |

| ΔPaO2mean, mean (SD) | mmHg | 57 (36.7) | 98.20 (59.95) |

| Day 1—PaO2/FiO2, mean (SD) | mmHg | 412.48 (197.08) | 453.59 (207.1) |

| Day 1 FiO2overall, mean (SD) | 0.54 (0.21) | 0.76 (0.26) | |

| FiO2mean, mean (SD) | 0.45 (0.15) | 0.48 (0.15) | |

| FiO2max, mean (SD) | 0.59 (0.22) | 0.82 (0.23) | |

| ΔFiO2mean, mean (SD) | 0.05 (0.08) | 0.15 (0.11) | |

| Functional neurologic outcome | |||

| GOSE 6-month follow-up, n (%) | |||

| GOSE < = 4 | 528 (48.7) | 53 (33.3) | |

| GOSE > 4 | 439 (40.5) | 95 (59.7) | |

| NA | 117 (10.8) | 11 (7) | |

Hypotension was defined as a documented systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg; hypoxia was defined as a documented partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) < 8 kPa (60 mmHg), oxygen saturation (SaO2) < 90%, or both

CT computed tomography, GCS Glasgow Coma Scale, GFAP gliofibrillar acid protein, GOSE Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended, ICP intracranial pressure, ICU intensive care unit, IQR interquartile range, NA not available, SD standard deviation

CENTER-TBI

Arterial oxygen levels and supplemental oxygen administration

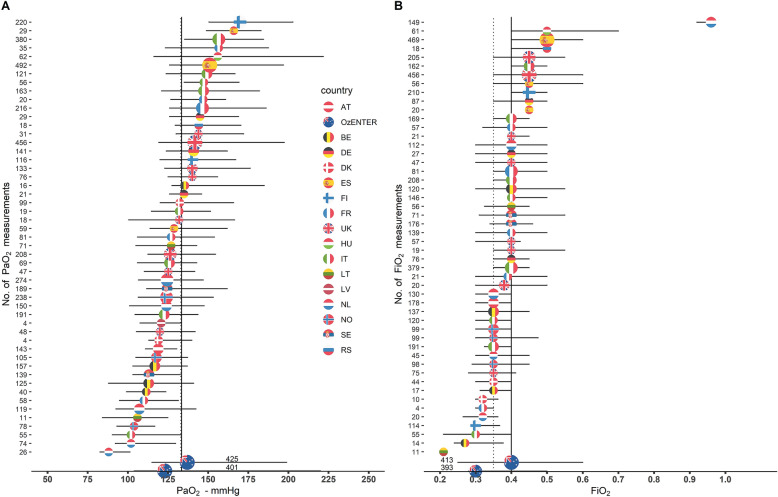

During the first week of ICU admission, a total of 11,577 measurements of PaO2 were available (5747 lowest and 5830 highest daily values), for an overall median of PaO2 and FiO2 of 112 mmHg (IQR 86–144) and 0.4 (IQR 0.3–0.5), respectively. A total of 526 (48.5%) patients had complete daily measurements of high PaO2 during the first week (median of 6 measures, IQR 4–7). The remaining patients had, respectively, 6 (136, 12.5%), 5 (72, 6.6%), 4 (89, 8.2%), 3 (94, 8.7%) and 2 (167, 15.4%) daily measurements of PaO2. The median highest PaO2 level during the first seven days since ICU admission was 134 mmHg (IQR 113–167). The median of highest FiO2 levels during the first seven days since ICU admission was 0.45 (IQR 0.40–0.5) (Supplemental Fig. 2). Mean PaO2max, PaO2mean and ΔPaO2mean were 231, 156 and 57 mmHg, respectively. PaO2max showed a strong correlation with ΔPaO2mean (TKendall = 0.51, 95% CI [0.48–0.53]) and with PaO2mean (TKendall = 0.66, 95% CI [0.64–0.68]). Mean FiO2max, FiO2mean and ΔFiO2mean were 0.59, 0.45 and 0.05 mmHg, respectively (Table 1). The highest PaO2 levels varied widely across centers, with the center-specific median ranging from 88 to 170 mmHg and the highest PaO2 levels within center ranging from 162 to 612 mmHg. Similarly, the highest median FiO2 levels during the first seven days since ICU admission varied widely across centers ranging from 0.21 to 0.96. Center variability in PaO2 (panel A) and FiO2 levels (panel B) across centers is represented in Fig. 1. Of note, overall median PaO2 levels in patients with brain tissue oxygen monitoring (PbtO2) were similar compared to the patient population with no PbtO2 monitoring (133 versus 137 mmHg, data not shown) (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Center-specific median values of daily highest PaO2 and FiO2 in CENTER-TBI and OzENTER-TBI cohorts. A Center-specific median values (colored by country flag) of daily highest PaO2 with the corresponding interquartile range. The solid vertical line represents the overall CENTER-TBI median of daily highest PaO2 values, while the dashed one refers to OzENTER-TBI, and the size of the dots is proportional to the number of PaO2 measurements in the center. B Center-specific median values (colored by country flag) of daily highest FiO2 with the corresponding interquartile range. The solid vertical line represents the overall CENTER-TBI median of daily highest FiO2 values, while the dashed one refers to OzENTER-TBI, and the size of the dots is proportional to the number of FiO2 measurements in the center

Arterial oxygen levels and outcomes in TBI patients

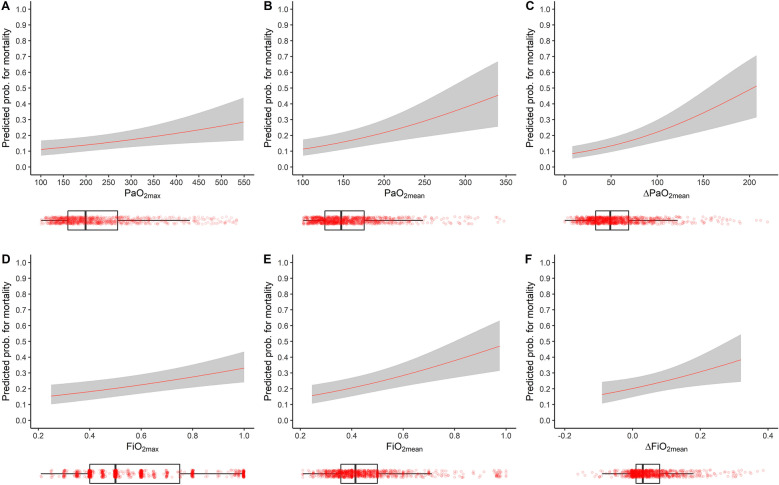

Data on mortality and neurological functional score GOSE at 6 months were available in 967 (89.2%) TBI patients. Five hundred and twenty-eight patients (54.6%) had an unfavorable GOSE at a 6-month follow-up, and 252 died within that period (26.1%). After adjusting, we estimated the OR for a 10 mmHg increase in PaO2. We found that both PaO2max (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1–1.04) and ΔPaO2mean (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.03–1.12) were independently associated with an unfavorable functional neurologic outcome as expressed by a GOSE score ≤ 4 at 6-month follow-up (Model 1, Table 2 and Supplemental Table 3 for the estimates in the complete regression model). Furthermore, we observed that all the exposure variables to high PaO2 were positively associated with an increased risk of mortality (PaO2max, OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.05; PaO2mean, OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.04–1.13; ΔPaO2mean, OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.08–1.2; all estimates for 10 mmHg) (Model 1, Table 2 and Supplemental Table 4). A detailed description of all confounders estimates for both outcomes is described in Supplemental Tables 3 and 4. The estimated probability of mortality from the regression model by arterial oxygen levels is depicted in Fig. 2 (Panel A, B, C).

Table 2.

Multivariable models on GOSE and mortality at 6-month follow-up in CENTER-TBI (Models 1, 2, 3 and 4)

| CENTER-TBI | 6-month GOSE N = 912 patients, 489 GOSE≤4 |

6-month mortality N = 912 patients, 225 died |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | OR* | 95% CI | p | OR* | 95% CI | p value |

| PaO2max (for 10 mmHg increase) | 1.02 | 1–1.04 | 0.014 | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | 0.002 |

| PaO2mean (for 10 mmHg increase) | 1.03 | 1–1.07 | 0.059 | 1.08 | 1.04–1.13 | < 0.001 |

| ΔPaO2mean (for 10 mmHg increase)b | 1.07 | 1.03–1.12 | 0.001 | 1.14 | 1.08–1.20 | < 0.001 |

| 6-month GOSE N = 764 patients, 407 GOSE≤4 |

6-month mortality N = 764 patients, 175 died |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2 | OR* | 95% CI | p | OR* | 95% CI | p |

| Logarithm GFAP | 1.51 | 1.33–1.71 | < 0.001 | 1.51 | 1.29–1.77 | < 0.001 |

| PaO2max (for 10 mmHg increase) | 1.02 | 1–1.03 | 0.064 | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | 0.008 |

| Logarithm GFAP | 1.52 | 1.34–1.72 | < 0.001 | 1.52 | 1.3–1.78 | < 0.001 |

| PaO2mean (for 10 mmHg increase) | 1.03 | 0.99–1.07 | 0.092 | 1.09 | 1.04–1.14 | 0.001 |

| Logarithm GFAP | 1.52 | 1.34–1.72 | < 0.001 | 1.53 | 1.3–1.81 | < 0.001 |

| ΔPaO2mean (for 10 mmHg increase) | 1.05 | 1–1.11 | 0.031 | 1.14 | 1.08–1.21 | < 0.001 |

| 6-month GOSE N = 877 patients, 470 GOSE≤4 |

6-month mortality N = 877 patients, 212 died |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3 | OR*** | 95% CI | p | OR*** | 95% CI | p |

| FiO2max (for 0.1 increase) | 1.03 | 0.96–1.1 | 0.453 | 1.18 | 1.08–1.29 | < 0.001 |

| FiO2mean, (for 0.1 increase) | 1.02 | 0.92–1.14 | 0.694 | 1.31 | 1.13–1.51 | < 0.001 |

| ΔFiO2mean, (for 0.1 increase) | 1.03 | 0.84–1.27 | 0.761 | 1.46 | 1.13–1.88 | 0.004 |

| 6-month GOSE N = 741 patients, 397 GOSE≤4 |

6-month mortality N = 741 patients, 168 died |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 4 | OR* | 95% CI | p | OR* | 95% CI | p |

| Logarithm GFAP | 1.52 | 1.34–1.72 | < 0.001 | 1.55 | 1.31–1.83 | < 0.001 |

| FiO2max (for 0.1 increase) | 1.03 | 0.96–1.12 | 0.389 | 1.20 | 1.08–1.33 | 0.001 |

| Logarithm GFAP | 1.52 | 1.34–1.72 | < 0.001 | 1.55 | 1.32–1.84 | < 0.001 |

| FiO2mean (for 0.1 increase) | 1.04 | 0.93–1.17 | 0.498 | 1.33 | 1.13–1.55 | < 0.001 |

| Logarithm GFAP | 1.51 | 1.33–1.72 | < 0.001 | 1.55 | 1.31–1.83 | < 0.001 |

| ΔFiO2mean (for 0.1 increase) | 0.98 | 0.78–1.23 | 0.846 | 1.40 | 1.05–1.87 | 0.023 |

Model 1. Adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals of exposure to high blood oxygen levels within 7 days of ICU admission on GOSE and mortality at 6-month follow-up in CENTER-TBI. Mixed-effect logistic regression models adjusted for age, pupillary reactivity (both reactive, one reactive, both unreactive), GCS motor (any flexion, none/extension, localizes/obey), Injury Severity Score, and, once at a time, PaO2max, PaO2mean and ΔPaO2mean for CENTER-TBI with center as a random effect. Model 2. Model 1 plus the degree of brain injury quantified as GFAP levels. Model 3. Adjusted odds ratio with 95% CI of GOSE and mortality at 6-month follow-up in TBI patients exposed to high supplemental oxygen administration within 7 days of ICU admission in CENTER-TBI. Mixed-effect logistic regression models adjusted for age, pupillary reactivity (reactive, one reactive, both unreactive), GCS motor (any flexion, none/extension, localizes/obey) and, once at a time, FiO2max, FiO2mean and ΔFiO2mean for CENTER-TBI with center as a random effect. Full models with all covariates estimates are reported in the Supplemental material. Model 4. Model 3 plus the degree of brain injury quantified as GFAP levels

aOR is for 10 mmHg increase in PaO2 covariate

b1 patient did not have low PaO2

cOR regards 0.1 increments in FiO2 covariate

Fig. 2.

The model-based probability for mortality in CENTER-TBI. A–C The probability for mortality estimated by Model 1 (i.e., Table 2) for PaO2max, PaO2mean and ΔPaO2mean vary through the corresponding spanned range of values, respectively, while continuous variables were set to median value and categorical variables to middle category. D–F The probability for mortality estimated by Model 3 (i.e., Table 2) for FiO2max, FiO2mean and ΔFiO2mean vary through the corresponding spanned range of values, respectively. At the same time, continuous variables were set to median value and categorical variables to middle category. Below each panel there are boxplots of the corresponding PaO2 and FiO2 variables, with scattered points of all measurements

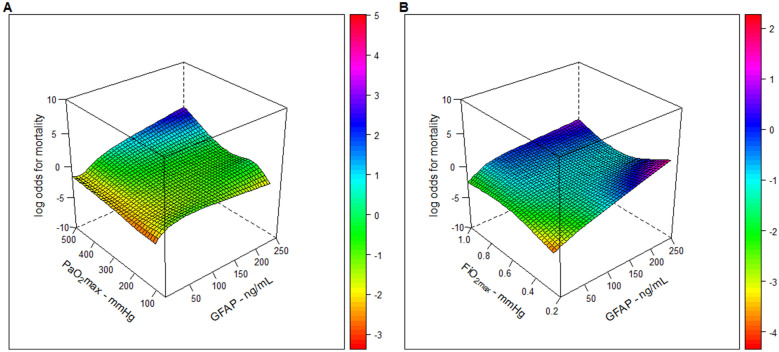

We also explored the role of exposure to high blood oxygen levels on the neurologic outcome by further adjusting the model for GFAP levels. GFAP was positively associated with a lower GOSE score and a higher mortality rate. Among the variables representing higher blood oxygenation, the ΔPaO2mean confirmed its positive association with a lower GOSE, while all the three high oxygenation variables remained positively associated with a higher mortality rate (Model 2, Table 2). A detailed description of all confounders estimates is reported in Supplemental Tables 5 and 6. We explored the interaction between exposure to high PaO2max and GFAP levels on GOSE and mortality. We did not find any interaction between the studied variables, as shown in Supplemental Figure 4 (panel A) and in Fig. 3 (panel A), respectively, for PaO2max—and for both PaO2mean and ΔPaO2mean as well (data not shown), where the surfaces that represent the smoothed interactions (on log scale) are mainly flattened on zero.

Fig. 3.

Tensor cubic spline for the interaction between PaO2max and FiO2max with GFAP in CENTER-TBI. In A on the left, we represented the tensor cubic spline with 4 degrees of freedom each, used for the interaction between PaO2max and GFAP in the logistic model with 6-month mortality as outcome. In B on the right, we represented the tensor cubic spline with 4 degrees of freedom each, used for the interaction between FiO2max and GFAP in the logistic model with 6-month mortality as outcome. All other continuous covariates were set to median values and mid-category for categorical ones

Supplemental oxygen administration and outcome

After adjustment for confounders, FiO2max, FiO2mean and ΔFiO2mean had no significant association with neurological outcomes. However, they showed a positive independent association with mortality at 6 months (Model 3, Table 2, and Supplemental Tables 7 and 8). The estimated mortality probability by administering supplemental oxygen is depicted in Fig. 2 (Panels D, E, and F). We also explored the role of exposure to high supplemental oxygen levels on the neurologic outcome by further adjusting the model for GFAP levels. GFAP was positively associated with a lower GOSE score and a higher mortality rate. Among the variables representing higher supplemental oxygen, no association was observed with GOSE. However, all the three high supplemental oxygen variables remained positively associated with a higher mortality rate (Model 4, Table 2). A detailed description of all confounders estimates is reported in Supplemental Tables 9 and 10. We explored the presence of interaction on GOSE and mortality between exposure to high FiO2 levels and GFAP levels. We did not find any interaction among the studied variables, as shown in Supplemental Figure 4 (panel B) and in Fig. 3 (panel B), respectively, for FiO2max—and for both FiO2mean and ΔFiO2mean as well (data not shown)—where the surfaces that represent the smoothed interactions (on log scale) are mainly flattened on zero.

Results concerning PaO2 and FiO2 were confirmed when the Benjamini–Hochberg method was applied to control the false discovery rate (results not shown). The sensitivity analyses accounting for missing data also corroborated the findings from the models on complete cases for both PaO2 and FiO2 data (Supplemental Table 11). From the descriptive analysis reported in Supplemental Table 12, patients with and without missing data have similar characteristics. As 5 patients died within 48 h with PaO2 levels beyond 450 mmHg and PaCO2 > 60 mmHg and may have undergone an apnea breath test, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding these patients for all the explored outcomes in the original analysis. No differences were observed as reported in Supplemental Table 13.

OzENTER-TBI

Arterial oxygen levels and supplemental oxygen administration

During the first week of ICU admission, a total of 1651 measurements of PaO2 were available (825 lowest and 826 highest daily values) for an overall median value of PaO2 and FiO2 of 133 (IQR 109–212) and 0.3 (IQR 0.25–0.4), respectively. During the first week, 43.4% had complete daily measurements of PaO2 (median 6, IQR 3–7). The median of the highest PaO2 level during the first 7 days since ICU admission was 133 (IQR 109–212) (Supplemental Fig. 2). The highest median FiO2 levels during the first 7 days since ICU admission was 0.35 (IQR 0.25–0.5) (Supplemental Fig. 2). Mean PaO2max, PaO2mean and ΔPaO2mean were 356, 197 and 98 mmHg, respectively (Table 1). PaO2max showed a strong correlation with ΔPaO2mean (TKendall = 0.63, p = < 0.001) and with PaO2mean (TKendall = 0.71, p < 0.001). Mean FiO2max, FiO2mean and ΔFiO2mean were 0.82, 0.48 and 0.15 mmHg, respectively. Center variability in PaO2 (panel A) and FiO2 levels (panel B) across the 2 centers was represented in Fig. 1.

Arterial oxygen levels and outcomes in TBI patients

Data on mortality and neurological functional score GOSE at 6 months were available for 148 (93.1%) TBI patients. Ninety-five patients (64.2%) had an unfavorable GOSE at 6-month follow-up, and 40 died within that period (27%). After adjusting for multiple confounders, including IMPACT core baseline covariates, ISS and the 2 different centers (i.e., site code), we observed that none of the oxygen exposure variables was independently associated with GOSE (Model 1, Table 3 and Supplemental Table 14). After adjustment for the same confounders, we observed that ΔPaO2mean, (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1–1.18) trended toward a higher mortality rate (Model 1, Table 3 and Supplemental Table 15). A detailed description of all confounders estimates for both outcomes was described in Supplemental Tables 14 and 15.

Table 3.

Multivariable models on GOSE and mortality at 6-month follow-up in OzENTER-TBI (Model 1 and 2)

| OzENTER-TBI | 6-month GOSE N = 141 patients, 92 GOSE ≤ 4 |

6-month mortality N = 141 patients, 39 died |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ORa | 95% CI | p value | ORa | 95% CI | p value |

| PaO2max (for 10 mmHg increase) | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 | 0.433 | 1 | 0.97–1.04 | 0.898 |

| PaO2mean (for 10 mmHg increase) | 1.01 | 0.96–1.07 | 0.656 | 1.05 | 0.99–1.11 | 0.118 |

| ΔPaO2mean (for 10 mmHg increase) | 1.03 | 0.96–1.12 | 0.376 | 1.08 | 1–1.18 | 0.054 |

| 6-month GOSE N = 141 patients, 92 GOSE ≤ 4 |

6-month mortality N = 141 patients, 39 died |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2 | ORb | 95% CI | p value | OR* | 95% CI | p value |

| FiO2max (for 0.1 increase) | 1.06 | 0.89–1.26 | 0.492 | 1 | 0.83–1.23 | 0.963 |

| FiO2mean (for 0.1 increase) | 1.02 | 0.77–1.34 | 0.911 | 1.32 | 0.98–1.8 | 0.069 |

| ΔFiO2mean (for 0.1 increase) | 1.15 | 0.79–1.69 | 0.483 | 1 | 0.68–1.48 | 0.981 |

Model 1. Adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals effect of exposure to high blood oxygen levels within 7 days of ICU admission on GOSE and mortality at 6-month follow-up. Validation on OzENTER-TBI. Standard logistic regression models adjusted for age, pupillary reactivity (both reactive, one reactive, both unreactive), GCS Motor (any flexion, none/extension, localizes/obey), Injury Severity Score, and, once at a time, PaO2max, PaO2mean and ΔPaO2mean for OzENTER-TBI with a dummy variable for center. Model 2. Adjusted odds ratio with 95% CI of GOSE and mortality at 6-month follow-up in TBI patients exposed to high supplemental oxygen administration within 7 days of ICU admission in OzENTER-TBI. Standard logistic regression models adjusted for age, pupillary reactivity (both reactive, one reactive, both unreactive), GCS Motor (any flexion, none/extension, localizes/obey) and, once at a time, FiO2max, FiO2mean and ΔFiO2mean for OzENTER-TBI with a dummy variable for center. Full models with all covariates estimates are reported in the Supplemental material

aOR is for 10 mmHg increase in PaO2 covariate

bOR regards 0.1 increments in FiO2 covariate

Supplemental oxygen administration and outcome

After adjustment for confounders, FiO2max, FiO2mean and ΔFiO2mean confirmed the data of CENTER-TBI with no significant association with neurological outcome. However, increases in FiO2mean trended toward a higher mortality rate (Model 2, Table 3). A detailed description of all confounders estimates for both outcomes was described in Supplemental Tables 16 and 17.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether exposure to high blood oxygen levels and high oxygen supplementation is independently associated with outcomes in TBI patients admitted to ICU and undergoing mechanical ventilation.

The main findings can be summarized as follows:

TBI patients were largely exposed, with wide variability between centers, to high levels of PaO2 during the first week of ICU admission.

Exposure to high PaO2 within seven days after ICU admission was an independent predictor of 6-month mortality in the CENTER-TBI cohort, even regardless of the severity of brain injury as defined by higher serum concentration of GFAP.

A higher average daily variability in PaO2 (ΔPaO2mean) predicts an unfavorable GOSE at 6 months in CENTER-TBI. These findings were not validated in the OzENTER-TBI cohort, where only ΔPaO2mean trended to a higher mortality rate.

Exposure to high levels of supplemental oxygen has an independent positive association with mortality in the CENTER-TBI cohort. In contrast, the association between higher FiO2mean and worse mortality in the OzENTER-TBI cohort showed similar directional trends but did not achieve statistical significance.

The first insight of this study is that more than 50% of TBI patients are exposed to hyperoxemia, defined as PaO2 levels above 120 mmHg [20, 21], during the first week after ICU admission. Despite hyperoxemia being quite often defined as the presence of a PaO2 > 120 [20, 22, 23], there is no agreement in the literature about a univocal threshold to define it [7, 8, 24–27]. Understanding if there is a maximum dose of oxygen that may be harmful for the brain tissue and whether a prolonged time of exposure to high oxygen levels may impair brain function and have an impact on mortality is debated. The lack of a clear definition of hyperoxemia and a limited time of oxygen exposure may lead to underestimate an association with outcome in TBI patients [27–30], despite some reports of a higher mortality in TBI patients exposed to higher levels of oxygen [7–9, 24].

This clinical investigation highlights a relevant finding that might have a direct potential clinical implication.

We reported that increasing exposure to high blood oxygen levels within the first 7 days after ICU admission independently correlates with long-term mortality in patients with TBI. This association was observed by exploring either the highest PaO2 levels (interpreted for each 10-mmHg increase) or the daily highest PaO2 variability. This may suggest that clinicians should pay attention not just to the absolute values of PaO2 but also to the daily swings of blood oxygenation. We logically hypothesized that PaO2 levels are driven by inappropriately high inspiratory levels of oxygen administered to TBI patients. When we explored the role of supplemental oxygen use (i.e., FiO2), similarly to the association reported between blood oxygenation and mortality, we showed that the highest the levels of FiO2 or the most elevated average daily swings of FiO2 within the first 7 days, the higher the mortality rate. These findings highlight a direct potential clinical implication for the management of oxygen administration in critically ill patients mechanically ventilated and admitted to the ICU with TBI. The amount of oxygen delivered to TBI patients can be easily titrated by ICU physicians by setting FiO2 levels on the ventilator. In the presence of an isolated TBI, therefore not involving the lung parenchyma that may lead to impaired oxygenation, high oxygen supplementation may be easily avoided on the ventilator by setting FiO2 levels to target a physiological range of blood oxygenation.

Furthermore, avoiding major changes in daily FiO2—if not needed to avoid hypoxemia—should prevent a major blood oxygenation variability and limit exposure to high oxygen levels and its detrimental effects. Our findings are in line with the recent guidelines of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) on the management of mechanical ventilation in patients with an acute brain injury which, with a low level of evidence, recommend targeting normoxia (80–120 mmHg) regardless of the presence of intracranial pressure (ICP) elevation while it remains unknown whether a certain threshold of high PaO2 should be considered safe in TBI patients [20]. The pathophysiological mechanisms behind the role of oxygen toxicity induced by hyperoxia (i.e., high FiO2) [31, 32] and hyperoxemia (i.e., high PaO2) [33, 34] in humans are widely recognized [5, 35]. On the one hand, hyperoxia has been shown to induce direct pulmonary toxicity by alveolar-capillary leak and fibrogenesis in healthy volunteers [36] and to have cytotoxic properties [37–39]. On the other hand, hyperoxemia increases peripheral vascular resistances [40–43], and determines the production of reactive oxygen species [44, 45] with the release of proinflammatory mediators [46]. In a cohort of severe TBI patients studied with advanced multimodality monitoring, hyperoxia had variable effects on lactate and lactate/pyruvate ratio. Microdialysis did not demonstrate a constant increase in the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen in at-risk tissue [47]. Similar results have been shown in TBI patients exposed to high FiO2. Hyperoxia marginally reduced lactate levels in brain tissue after TBI. However, the estimated redox status of the cells did not change and cerebral O2 extraction seemed to be reduced. These data indicate that glucose oxidation was not improved by hyperoxia in cerebral and adipose tissue and might even be impaired [48].

In recent years, the role of oxygen on outcome has been explored in ICU patients to evaluate whether oxygen's inflammatory and cytotoxic effects on organ viability might translate into a worse survival. Two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in critically ill (Oxygen-ICU) [49] and in septic patients (HYPERS-2S) [50] showed that targeting higher levels of PaO2 or hyperoxia could cause a higher mortality rate. A large meta-analysis including critically ill patients confirmed that a strategy targeting more elevated levels of PaO2 increased mortality [51].

In contrast, so far, 4 big RCTs (LOCO2 trial [52], ICU-ROX trial [53], HOT-ICU trial [54] and O2-ICU trial [55]) suggested no significant differences in terms of primary study outcome (i.e., mortality [52, 54]; ventilator-free days [53]; and non-respiratory Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [55]) between patients managed with lower versus higher oxygen targets. However, these trials showed differences in their study design in terms of targeted physiologic variables of oxygenation (i.e., PaO2, SpO2 and SaO2), targets of oxygenation, safety threshold for oxygen conservative therapy [52] and study outcomes. These trials were in broad populations of critically ill patients, and do not specifically address patients with TBI. Indeed, the one trial that specifically reported on patients with brain injury provided data suggesting that patients with neurological disease not due to hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy may have had worse outcomes with conservative oxygen therapy [53]. In the meantime, the UK-ROX trial (ISRCTN13384956) and the Mega-ROX trial (ACTRN12620000391976)—two large RCTs aimed at exploring the role of oxygen targets on mortality in critically ill patients—are currently ongoing and will shed further light on the role of oxygen targets on outcome in ICU.

We also investigated whether these negative associations of hyperoxia with outcome were modulated by injury severity, as measured by GFAP levels [17, 56]. GFAP is a biomarker representing glial injury [56] and correlates well with the severity of brain injury evaluated by brain computed tomography [17]. Furthermore, GFAP is associated with outcomes in TBI patients [57]. However, we could not demonstrate an interaction between injury severity (as measured by GFAP levels) and the association between oxygen exposure variables and outcome. This corroborates the idea that oxygen exposure may somehow influence the outcome in TBI patients regardless of the severity of brain injury. Therefore, preventing exposure to high oxygen levels in TBI patients might be suggested even in milder TBI.

However, another potential explanation for the lack of interaction between oxygen levels and GFAP may be the temporal misalignment of GFAP and oxygen levels assessment. TBI is not an acute event but an evolving process. Hence, acute GFAP and sub-acute oxygen level measures may capture distinct complementary aspects providing independent prognostic information which can enable a more effective risk-stratification of patients with TBI. Moreover, it is conceivable that high blood oxygen levels could have a differential effect based on the injury pattern/type rather than the severity of structural brain damage after TBI owing to distinct pathogenetic and pathobiological pathways. In support of such a possibility, robust experimental evidence has indicated specific therapeutic responses according to different injury models as also tracked by circulating GFAP [58, 59].

Strengths

Strengths of this work include the prospective nature of the two multicenter cohorts of patients, with the OzENTER-TBI validation cohort confirming a trend similar to the findings reported in the sizeable CENTER-TBI cohort. Data comes from a large real-world dataset of patients with TBI representing a global population of TBI patients. Evaluating the effect of exposure to oxygen on the outcome is not episodic but integrated over the first week after ICU admission increases the association's credibility. Furthermore, the exposure variables (i.e., PaO2 and FiO2) are not evaluated using a pre-set cut-off. Still, their association with the outcome is explored by including them as continuous data, strengthening the findings in the multivariable models. The use of GFAP, which allowed to investigate whether oxygen exposure could play a different contribution to the outcome because of a different degree of brain injury severity, make the results generalizable to most of the spectrum of TBI. Moreover, although we acknowledge that various models were performed, the strong associations we found on mortality were supported even when we accounted for multiple comparisons.

Limitations

Several limitations deserve mention. First, considering the observational nature of the data, it is speculative to draw a direct causal relationship between high arterial oxygen levels and supplemental oxygen administration and their relationship with outcome. Therefore, our results should be taken with caution. Further randomized controlled studies are necessary to assess the effect of high arterial oxygen levels and supplemental oxygen administration on the TBI patients' outcomes. Second, 6-month GOSE and mortality are influenced by several other factors, such as systemic and ICU complications and post-ICU events. To overcome this limitation, we used an analytic model considering the effect of other available confounding factors, particularly patient clinical condition and neuroimaging features.

Besides, in these two cohorts, only a minority of patients had a brain tissue oxygen monitor. As documented by a phase-2 RCT, monitoring brain tissue (PbtO2) oxygenation could reduce brain tissue hypoxia with a trend toward more favorable outcomes compared to treatment driven by intracranial pressure monitoring only [60]. A recent consensus suggested the possibility, in the presence of low PbtO2 values, of elevating the PaO2 up to 150 mmHg or higher in more severe cases, fine-tuned to the patient's PbtO2 values [61]. Some phase III randomized trials are ongoing to demonstrate the benefit of exposing hypoxic brain patients to higher oxygen levels. Therefore, our findings are not focused on a population with brain tissue hypoxia but to the overall TBI population, with/without brain hypoxia. However, we did not observe a difference in the distribution of PaO2 levels between TBI with or without PbtO2 monitoring. We cannot exclude the possibility that the worse outcomes associated with higher PaO2 were due to use of higher FiO2 in patients with more severe injury or physiological compromise. Further, these findings may not apply to patients in whom FiO2 and PaO2 are titrated to PbtO2 levels.

Moreover, the two cohorts were prospectively collected with the primary aim of assessing the epidemiology and clinical practice in the management of TBI patients. As respiratory targets are not included in the primary outcome, more frequent daily data on gas exchange and more specific data on the ventilator management of these patients are missing and would have strengthened our analysis. Further, we do not have detailed data about the presence of hyperoxemia in patients undergoing an apnea breath test. However, only five patients who died within 48 h had PaO2 levels beyond 450 mmHg with a PaCO2 > 60 mmHg in the CENTER-TBI dataset, which may suggest an apnea breath test. Sensitivity analyses excluding these patients confirmed the independent association with outcome of both PaO2 and FiO2 variables. Finally, our dataset is limited to the first week after TBI. However, our analysis includes data that provides a longitudinal view of PaO2 management over time.

Conclusions

In two large prospective multicenter cohorts of critically ill patients with TBI arterial oxygen levels and supplemental oxygen, administration varied widely across centers during the first 7 days after ICU admission. Exposure to high arterial blood oxygen and high supplemental oxygen were independently associated with 6-month mortality in the CENTER-TBI cohort. This was not driven by the severity of brain injury quantified by serum levels of GFAP within 24 h. The findings were not externally validated in the OzENTER-TBI cohort likely due to the limited sample size, although the effects were in the same direction of the ones from CENTER-TBI. Titration of supplemental oxygen in the presence of TBI is a practice immediately applicable at bedside. Randomized controlled trials and high-level evidence guidelines are warranted to help clinicians optimize oxygen exposure management in this cohort of patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The CENTER-TBI ICU WP6 participants and ICU ONLY investigators: Cecilia Ackerlund: Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Section of Perioperative Medicine and Intensive Care, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. Krisztina Amrein: János Szentágothai Research Centre, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary. Nada Andelic: Division of Surgery and Clinical Neuroscience, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Oslo University Hospital and University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway. Lasse Andreassen: Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Northern Norway, Tromso, Norway. Audny Anke: Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University Hospital Northern Norway, Tromso, Norway. Gérard Audibert: Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care, University Hospital Nancy, Nancy, France. Philippe Azouvi: Raymond Poincare hospital, Assistance Publique – Hopitaux de Paris, Paris, France. Maria Luisa Azzolini: Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care, S Raffaele University Hospital, Milan, Italy. Ronald Bartels: Department of Neurosurgery, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Ronny Beer: Department of Neurology, Neurological Intensive Care Unit, Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria. Bo-Michael Bellander: Department of Neurosurgery & Anesthesia & intensive care medicine, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. Habib Benali: Anesthesie-Réanimation, Assistance Publique – Hopitaux de Paris, Paris, France. Maurizio Berardino: Department of Anesthesia & ICU, AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino—Orthopedic and Trauma Center, Torino, Italy. Luigi Beretta: Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care, S Raffaele University Hospital, Milan, Italy. Erta Beqiri: NeuroIntensive Care, Niguarda Hospital, Milan, Italy. Morten Blaabjerg: Department of Neurology, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark. Stine Borgen Lund: Department of Public Health and Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway. Camilla Brorsson: Department of Surgery and Perioperative Science, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden. Andras Buki: Department of Neurosurgery, Medical School, University of Pécs, Hungary and Neurotrauma Research Group, János Szentágothai Research Centre, University of Pécs, Hungary. Manuel Cabeleira: Brain Physics Lab, Division of Neurosurgery, Dept of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Alessio Caccioppola: Neuro ICU, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy. Emiliana Calappi: Neuro ICU, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy. Maria Rosa Calvi: Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care, S Raffaele University Hospital, Milan, Italy. Peter Cameron: ANZIC Research Centre, Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Guillermo Carbayo Lozano: Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital of Cruces, Bilbao, Spain. Marco Carbonara: Neuro ICU, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy. Ana M. Castaño-León: Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain. Simona Cavallo: Department of Anesthesia & ICU, AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino—Orthopedic and Trauma Center, Torino, Italy. Giorgio Chevallard: NeuroIntensive Care, Niguarda Hospital, Milan, Italy. Arturo Chieregato: NeuroIntensive Care, Niguarda Hospital, Milan, Italy. Giuseppe Citerio: School of Medicine and Surgery, Università Milano—Bicocca, Milano, Italy and NeuroIntensive Care, ASST di Monza, Monza, Italy. Hans Clusmann: Department of Neurosurgery, Medical Faculty RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany . Mark Steven Coburn: Department of Anaesthesiology, University Hospital of Aachen, Aachen, Germany. Jonathan Coles: Department of Anesthesia & Neurointensive Care, Cambridge University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK. Jamie D. Cooper: School of Public Health & PM, Monash University and The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Marta Correia: Radiology/MRI department, MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, UK. Endre Czeiter: Department of Neurosurgery, Medical School, University of Pécs, Hungary and Neurotrauma Research Group, János Szentágothai Research Centre, University of Pécs, Hungary. Marek Czosnyka: Brain Physics Lab, Division of Neurosurgery, Dept of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Claire Dahyot-Fizelier: Intensive Care Unit, CHU Poitiers, Potiers, France. Paul Dark: University of Manchester NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Critical Care Directorate, Salford Royal Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Salford, UK. Véronique De Keyser: Department of Neurosurgery, Antwerp University Hospital and University of Antwerp, Edegem, Belgium. Vincent Degos: Anesthesie-Réanimation, Assistance Publique – Hopitaux de Paris, Paris, France. Francesco Della Corte: Department of Anesthesia & Intensive Care, Maggiore Della Carità Hospital, Novara, Italy. Hugo den Boogert: Department of Neurosurgery, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Bart Depreitere: Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium. Đula Đilvesi: Department of Neurosurgery, Clinical centre of Vojvodina, Faculty of Medicine, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia. Abhishek Dixit: Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Jens Dreier: Center for Stroke Research Berlin, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and Berlin Institute of Health, Berlin, Germany. Guy-Loup Dulière: Intensive Care Unit, CHR Citadelle, Liège, Belgium. Ari Ercole: Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Erzsébet Ezer: Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Therapy, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary. Martin Fabricius: Departments of Neurology, Clinical Neurophysiology and Neuroanesthesiology, Region Hovedstaden Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark. Kelly Foks: Department of Neurology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Shirin Frisvold: Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive care, University Hospital Northern Norway, Tromso, Norway. Alex Furmanov: Department of Neurosurgery, Hadassah-hebrew University Medical center, Jerusalem, Israel. Damien Galanaud: Anesthesie-Réanimation, Assistance Publique – Hopitaux de Paris, Paris, France. Dashiell Gantner: ANZIC Research Centre, Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Alexandre Ghuysen: Emergency Department, CHU, Liège, Belgium. . Lelde Giga: Neurosurgery clinic, Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital, Riga, Latvia. Jagoš Golubović: Department of Neurosurgery, Clinical centre of Vojvodina, Faculty of Medicine, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia. Pedro A. Gomez: Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain. Benjamin Gravesteijn: Department of Public Health, Erasmus Medical Center-University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands . Francesca Grossi: Department of Anesthesia & Intensive Care, Maggiore Della Carità Hospital, Novara, Italy. Deepak Gupta: Department of Neurosurgery, Neurosciences Centre & JPN Apex trauma centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi-110029, India. Iain Haitsma: Department of Neurosurgery, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Raimund Helbok: Department of Neurology, Neurological Intensive Care Unit, Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria. Eirik Helseth: Department of Neurosurgery, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway. Jilske Huijben: Department of Public Health, Erasmus Medical Center-University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Peter J. Hutchinson : Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Addenbrooke’s Hospital & University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Stefan Jankowski: Neurointensive Care, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield, UK. Faye Johnson: Salford Royal Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Acute Research Delivery Team, Salford, UK. Mladen Karan: Department of Neurosurgery, Clinical centre of Vojvodina, Faculty of Medicine, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia. Angelos G. Kolias : Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Addenbrooke’s Hospital & University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Daniel Kondziella: Departments of Neurology, Clinical Neurophysiology and Neuroanesthesiology, Region Hovedstaden Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark. Evgenios Kornaropoulos: Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Lars-Owe Koskinen: Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Neurosurgery, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden. Noémi Kovács: Hungarian Brain Research Program—Grant No. KTIA_13_NAP-A-II/8, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary. Ana Kowark: Department of Anaesthesiology, University Hospital of Aachen, Aachen, Germany. Alfonso Lagares: Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain. Steven Laureys: Cyclotron Research Center, University of Liège, Liège, Belgium. Aurelie Lejeune: Department of Anesthesiology-Intensive Care, Lille University Hospital, Lille, France. Fiona Lecky: Centre for Urgent and Emergency Care Research (CURE), Health Services Research Section, School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK and Emergency Department, Salford Royal Hospital, Salford UK. Didier Ledoux: Cyclotron Research Center , University of Liège, Liège, Belgium . Roger Lightfoot: Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care, University Hospitals Southampton NHS Trust, Southampton, UK. Hester Lingsma: Department of Public Health, Erasmus Medical Center-University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Andrew I.R. Maas: Department of Neurosurgery, Antwerp University Hospital and University of Antwerp, Edegem, Belgium. Alex Manara: Intensive Care Unit, Southmead Hospital, Bristol, Bristol, UK. Hugues Maréchal: Intensive Care Unit, CHR Citadelle, Liège, Belgium. Costanza Martino: Department of Anesthesia & Intensive Care,M. Bufalini Hospital, Cesena, Italy. Julia Mattern: Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany. Catherine McMahon: Department of Neurosurgery, The Walton centre NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, UK. David Menon: Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Tomas Menovsky: Department of Neurosurgery, Antwerp University Hospital and University of Antwerp, Edegem, Belgium. Benoit Misset: Cyclotron Research Center , University of Liège, Liège, Belgium . Visakh Muraleedharan: Karolinska Institutet, INCF International Neuroinformatics Coordinating Facility, Stockholm, Sweden. Lynnette Murray: ANZIC Research Centre, Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Ancuta Negru: Department of Neurosurgery, Emergency County Hospital Timisoara, Timisoara, Romania. David Nelson: Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Section of Perioperative Medicine and Intensive Care, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. Virginia Newcombe: Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. József Nyirádi: János Szentágothai Research Centre, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary. Fabrizio Ortolano: Neuro ICU, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy. Jean-François Payen: Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care, University Hospital of Grenoble, Grenoble, France. Vincent Perlbarg: Anesthesie-Réanimation, Assistance Publique – Hopitaux de Paris, Paris, France. Paolo Persona: Department of Anesthesia & Intensive Care, Azienda Ospedaliera Università di Padova, Padova, Italy. Wilco Peul: Dept. of Neurosurgery, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands and Dept. of Neurosurgery, Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague, The Netherlands. Anna Piippo-Karjalainen: Department of Neurosurgery, Helsinki University Central Hospital. Horia Ples: Department of Neurosurgery, Emergency County Hospital Timisoara, Timisoara, Romania. Inigo Pomposo: Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital of Cruces, Bilbao, Spain. Jussi P. Posti: Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Department of Neurosurgery and Turku Brain Injury Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Turku, Finland. Louis Puybasset: Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Pitié -Salpêtrière Teaching Hospital, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris and University Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France. Andreea Rădoi: Neurotraumatology and Neurosurgery Research Unit (UNINN), Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Barcelona, Spain. Arminas Ragauskas: Department of Neurosurgery, Kaunas University of technology and Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania. Rahul Raj: Department of Neurosurgery, Helsinki University Central Hospital. Jonathan Rhodes: Department of Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain Medicine NHS Lothian & University of Edinburg, Edinburgh, UK. Sophie Richter: Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Saulius Rocka: Department of Neurosurgery, Kaunas University of technology and Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania. Cecilie Roe: Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Oslo University Hospital/University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway. Olav Roise: Division of Orthopedics, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway and Institute of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Olso, Oslo, Norway. Jeffrey Rosenfeld: National Trauma Research Institute, The Alfred Hospital, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Christina Rosenlund: Department of Neurosurgery, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark. Guy Rosenthal: Department of Neurosurgery, Hadassah-hebrew University Medical center, Jerusalem, Israel. Rolf Rossaint: Department of Anaesthesiology, University Hospital of Aachen, Aachen, Germany. Sandra Rossi: Department of Anesthesia & Intensive Care, Azienda Ospedaliera Università di Padova, Padova, Italy. Juan Sahuquillo: Neurotraumatology and Neurosurgery Research Unit (UNINN), Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Barcelona, Spain. Oliver Sakowitz: Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany and Klinik für Neurochirurgie, Klinikum Ludwigsburg, Ludwigsburg, Germany. Renan Sanchez-Porras: Klinik für Neurochirurgie, Klinikum Ludwigsburg, Ludwigsburg, Germany. Oddrun Sandrød: Klinik für Neurochirurgie, Klinikum Ludwigsburg, Ludwigsburg, Germany. Kari Schirmer-Mikalsen: Department of Anasthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, St.Olavs. Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway and Department of Neuromedicine and Movement Science, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway. Rico Frederik Schou: Department of Neuroanesthesia and Neurointensive Care, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark. Charlie Sewalt: Department of Public Health, Erasmus Medical Center-University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands . Peter Smielewski: Brain Physics Lab, Division of Neurosurgery, Dept of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Abayomi Sorinola: Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary. Emmanuel Stamatakis: Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Ewout W. Steyerberg: Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care, University Hospitals Southampton NHS Trust, Southampton, UK and Dept. of Department of Biomedical Data Sciences, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands. Nino Stocchetti: Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, Milan University, and Neuroscience ICU, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Italy. Nina Sundström: Department of Radiation Sciences, Biomedical Engineering, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden. Riikka Takala: Perioperative Services, Intensive Care Medicine and Pain Management, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Turku, Finland. Viktória Tamás: Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary. Tomas Tamosuitis: Department of Neurosurgery, Kaunas University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania. Olli Tenovuo: Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Department of Neurosurgery and Turku Brain Injury Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Turku, Finland. Matt Thomas: Intensive Care Unit, Southmead Hospital, Bristol, Bristol, UK. Dick Tibboel: Intensive Care and Department of Pediatric Surgery, Erasmus Medical Center, Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Christos Tolias: Department of Neurosurgery, Kings college London, London, UK. Tony Trapani: ANZIC Research Centre, Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Cristina Maria Tudora: Department of Neurosurgery, Emergency County Hospital Timisoara, Timisoara, Romania. Andreas Unterberg: Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany . Peter Vajkoczy: Neurologie, Neurochirurgie und Psychiatrie, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Egils Valeinis: Neurosurgery clinic, Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital, Riga, Latvia. Shirley Vallance: ANZIC Research Centre, Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Zoltán Vámos: Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Therapy, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary. Gregory Van der Steen: Department of Neurosurgery, Antwerp University Hospital and University of Antwerp, Edegem, Belgium. Jeroen T.J.M. van Dijck: Dept. of Neurosurgery, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands and Dept. of Neurosurgery, Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague, The Netherlands. Thomas A. van Essen: Dept. of Neurosurgery, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands and Dept. of Neurosurgery, Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague, The Netherlands. Roel van Wijk: Dept. of Neurosurgery, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands and Dept. of Neurosurgery, Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague, The Netherlands. Alessia Vargiolu: NeuroIntensive Care, ASST di Monza, Monza, Italy. Emmanuel Vega: Department of Anesthesiology-Intensive Care, Lille University Hospital, Lille, France. Anne Vik: Department of Neuromedicine and Movement Science, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway and Department of Neurosurgery, St.Olavs. Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway. Rimantas Vilcinis: Department of Neurosurgery, Kaunas University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania. Victor Volovici: Department of Neurosurgery, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Peter Vulekovic: Department of Neurosurgery, Clinical centre of Vojvodina, Faculty of Medicine, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia. Eveline Wiegers: Department of Public Health, Erasmus Medical Center-University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Guy Williams: Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Stefan Winzeck: Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Stefan Wolf: Department of Neurosurgery, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and Berlin Institute of Health, Berlin, Germany. Alexander Younsi: Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany. Frederick A. Zeiler: Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK and Section of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada. Agate Ziverte: Neurosurgery clinic, Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital, Riga, Latvia. Tommaso Zoerle: Neuro ICU, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy. OzENTER TBI participants and Investigators: Jamie Cooper: School of Public Health & PM, Monash University and The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Dashiell Gantner: ANZIC Research Centre, Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Russel Gruen: NTU Institute for Health Technologies and Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Lynette Murray: ANZIC Research Centre, Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Jeffrey V Rosenfeld: National Trauma Research Institute, The Alfred Hospital, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Dinesh Varma: Department of Radiology, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia and Department of Surgery, Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Tony Trapani: ANZIC Research Centre, Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Shirley Vallance: ANZIC Research Centre, Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Christopher MacIsaac: Intensive Care Unit, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. Andrea Jordan Department of Intensive Care, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia.

Author contributions

GC ideated and supervised the project, participated in the data analysis, drafted the manuscript and the supplementary tables, discussed the findings with all the authors and collected the COIs. ER ideated the project, participated in the data analysis and drafted the manuscript and supplementary tables. MP, PR and SG analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript and the supplementary tables. DKM, SM, DJC, AM and EJAW were actively involved the manuscript drafting and revision. All co-authors gave substantial feedback on the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Milano - Bicocca within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. European Commission 7th Framework program and the Australian Health and Medical Research Council.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

GC reports grants and personal fees as Speakers' Bureau Member and Advisory Board Member from Integra and Neuroptics. DKM reports grants from the European Union and UK National Institute for Health Research, during the study; grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from GlaxoSmithKline; personal fees from Neurotrauma Sciences, Lantmaanen AB, Pressura, and Pfizer, outside of the submitted work. DJC reports grants and Fellowship from National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), Medical Research Future Fund (Australia) during the study, and personal fees from Pressura, outside of the submitted work.

Footnotes

CENTER-TBI ICU and OzENTER-TBI Participants and Investigators are listed in the Acknowledgements section.

The original online version of this article was revised: Modifications have been made to the Abstract, several text parts and Figure 3. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the erratum/correction for this article.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

2/13/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s00134-022-06924-6

Contributor Information

Giuseppe Citerio, Email: giuseppe.citerio@unimib.it.

CENTER-TBI, OzENTER-TBI Participants and Investigators:

Cecilia Ackerlund, Krisztina Amrein, Nada Andelic, Lasse Andreassen, Audny Anke, Gérard Audibert, Philippe Azouvi, Maria Luisa Azzolini, Ronald Bartels, Ronny Beer, Bo-Michael Bellander, Habib Benali, Maurizio Berardino, Luigi Beretta, Erta Beqiri, Morten Blaabjerg, Stine Borgen Lund, Camilla Brorsson, Andras Buki, Manuel Cabeleira, Alessio Caccioppola, Emiliana Calappi, Maria Rosa Calvi, Peter Cameron, Guillermo Carbayo Lozano, Marco Carbonara, Ana M Castaño-León, Simona Cavallo, Giorgio Chevallard, Arturo Chieregato, Giuseppe Citerio, Hans Clusmann, Mark Steven Coburn, Jonathan Coles, Jamie D Cooper, Marta Correia, Endre Czeiter, Marek Czosnyka, Claire Dahyot-Fizelier, Paul Dark, Véronique Keyser, Vincent Degos, Francesco Della Corte, Hugo Boogert, Bart Depreitere, Đula Đilvesi, Abhishek Dixit, Jens Dreier, Guy-Loup Dulière, Ari Ercole, Erzsébet Ezer, Martin Fabricius, Kelly Foks, Shirin Frisvold, Alex Furmanov, Damien Galanaud, Dashiell Gantner, Alexandre Ghuysen, Lelde Giga, Jagoš Golubović, Pedro A Gomez, Benjamin Gravesteijn, Francesca Grossi, Deepak Gupta, Iain Haitsma, Raimund Helbok, Eirik Helseth, Jilske Huijben, Peter J Hutchinson, Stefan Jankowski, Faye Johnson, Mladen Karan, Angelos G Kolias, Daniel Kondziella, Evgenios Kornaropoulos, Lars-Owe Koskinen, Noémi Kovács, Ana Kowark, Alfonso Lagares, Steven Laureys, Aurelie Lejeune, Fiona Lecky, Didier Ledoux, Roger Lightfoot, Hester Lingsma, Andrew I.R. Maas, Alex Manara, Hugues Maréchal, Costanza Martino, Julia Mattern, Catherine McMahon, David Menon, Tomas Menovsky, Benoit Misset, Visakh Muraleedharan, Lynnette Murray, Ancuta Negru, David Nelson, Virginia Newcombe, József Nyirádi, Fabrizio Ortolano, Jean-François Payen, Vincent Perlbarg, Paolo Persona, Wilco Peul, Anna Piippo-Karjalainen, Horia Ples, Inigo Pomposo, Jussi P Posti, Louis Puybasset, Andreea Rădoi, Arminas Ragauskas, Rahul Raj, Jonathan Rhodes, Sophie Richter, Saulius Rocka, Cecilie Roe, Olav Roise, Jeffrey Rosenfeld, Christina Rosenlund, Guy Rosenthal, Rolf Rossaint, Sandra Rossi, Juan Sahuquillo, Oliver Sakowitz, Renan Sanchez-Porras, Oddrun Sandrød, Kari Schirmer-Mikalsen, Rico Frederik Schou, Charlie Sewalt, Peter Smielewski, Abayomi Sorinola, Emmanuel Stamatakis, Ewout W Steyerberg, Nino Stocchetti, Nina Sundström, Riikka Takala, Viktória Tamás, Tomas Tamosuitis, Olli Tenovuo, Matt Thomas, Dick Tibboel, Christos Tolias, Tony Trapani, Cristina Maria Tudora, Andreas Unterberg, Peter Vajkoczy, Egils Valeinis, Shirley Vallance, Zoltán Vámos, Gregory Steen, T.J.M. van Dijck Jeroen, Thomas A Essen, Roel Wijk, Alessia Vargiolu, Emmanuel Vega, Anne Vik, Rimantas Vilcinis, Victor Volovici, Peter Vulekovic, Eveline Wiegers, Guy Williams, Stefan Winzeck, Stefan Wolf, Alexander Younsi, Frederick A Zeiler, Agate Ziverte, Tommaso Zoerle, Jamie Cooper, Dashiell Gantner, Russel Gruen, Lynette Murray, Jeffrey V Rosenfeld, Dinesh Varma, Tony Trapani, Shirley Vallance, Christopher MacIsaac, and Andrea Jordan

References

- 1.McHugh GS, Engel DC, Butcher I, Steyerberg EW, Lu J, Mushkudiani N, Hernández AV, Marmarou A, Maas AI, Murray GD. The IMPACT study results from the prognostic value of secondary insults in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(2):287–293. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacIntyre NR. Tissue hypoxia: implications for the respiratory clinician. Respir Care. 2014;59(10):1590–1596. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itagaki T, Nakano Y, Okuda N, Izawa M, Onodera M, Imanaka H, Nishimura M. Hyperoxemia in mechanically ventilated, critically ill subjects: incidence and related factors. Respir Care. 2015;60(3):335–340. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behnke AR, Johnson FS, Poppen JR, Motley EP. The effect of oxygen on man at pressures from 1 to 4 atmospheres. Am J Physiol. 1934;110:565–572. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1934.110.3.565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer M, Young PJ, Laffey JG, Asfar P, Taccone FS, Skrifvars MB, Meyhoff CS, Radermacher P. Dangers of hyperoxia. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):440. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03815-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quintard H, Patet C, Suys T, Marques-Vidal P, Oddo M. Normobaric hyperoxia is associated with increased cerebral excitotoxicity after severe traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2015;22(2):243–250. doi: 10.1007/s12028-014-0062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenner M, Stein D, Peter Hu, Kufera J, Wooford M, Scalea T. Association between early hyperoxia and worse outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Arch Surg. 2012;147(11):1042–1046. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rincon F, Kang J, Vibbert M, Urtecho J, Athar MK, Jallo J. Significance of arterial hyperoxia and relationship with case fatality in traumatic brain injury: a multicentre cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(7):799–805. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis DP, Meade W, Sise MJ, Kennedy F, Simon F, Tominaga G, Steele J, Coimbra R. Both hypoxemia and extreme hyperoxemia may be detrimental in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(12):2217–2223. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jonge E, Peelen L, Keijzers PJ, Joore H, de Lange D, van der Voort PHJ, Bosman RJ, de Waal RA, Wesselink R, de Keizer NF. Association between administered oxygen, arterial partial oxygen pressure and mortality in mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients. Crit Care. 2008;12(6):R156. doi: 10.1186/cc7150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirunpattarasilp C, Shiina H, Na-Ek N, Attwell D. The effect of hyperoxemia on neurological outcomes of adult patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurocrit Care. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12028-021-01423-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maas AIR, Menon DK, Steyerberg EW, Citerio G, Lecky F, Manley GT, Hill S, Legrand V, Sorgner A, CENTER-TBI Participants and Investigators Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI): a prospective longitudinal observational study. Neurosurgery. 2015;76(1):67–80. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steyerberg EW, Wiegers E, Sewalt C, Buki A, Citerio G, De Keyser V, Ercole A, Kunzmann K, Lanyon L, Lecky F, Lingsma H, Manley G, Nelson D, Peul W, Stocchetti N, von Steinbüchel N, Vande Vyvere T, Verheyden J, Wilson L, Maas AIR, Menon DK, CENTER-TBI Participants and Investigators Case-mix, care pathways, and outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury in CENTER-TBI: a European prospective, multicentre, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(10):923–934. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]