Abstract

Osteoma is a common, slow growing bone tumor, and often affects the paranasal sinus. Typically, it shows a very hyperdense osseous lesion on computed tomography (CT) scan and low-intensity change on T2-weighted image on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). No report has mentioned osteomas in blood supply on MRI. A 57-year-old male patient presented with a prolonged declined activity and a gigantic osseous tumor that originated from the frontal sinus, which markedly compressed the bilateral frontal lobe. MRI revealed a slightly enhanced front basal part of the tumor by gadolinium, with blood supply from ethmoidal arteries. The patient underwent surgery, and the diagnosis of osteoma was made based on histological findings. We reported a case of giant osteoma originating from the frontal sinus with unusual blood supply on 4-dimensional MR angiography.

Keywords: Frontal sinus, Giant osteoma, Blood supply

Introduction

Osteoma is a slow growing and the most common bone tumor that is frequently observed in daily clinical practice. The commonly affected areas in the skull are the cranial vault, maxilla, mandible, external auditory canal, and paranasal sinus [1,2]. Osteoma in the cranial vault usually grows outward [1], while osteoma arising from the paranasal sinus is often reported with intracranial involvement. Regarding paranasal osteoma, asymptomatic lesions were observed in 3% of the population [3]. Large lesions might block the outlet of sinuses, thereby forming mucocele or pneumatocele [4], [5], [6], [7] and leading to abscess or meningitis. Differential diagnosis on imaging includes osteoblastoma, which is also a benign tumor but malignant transformation into osteosarcoma was reported [8,9]. The pathological specimens in some reported osteoma cases suggested osteoblastoma-like lesions, and such entities were described as osteomas with osteoblastic features (OObF) [10], [11], [12], [13]. OObF does not have a more aggressive and clinical course than osteoma, but it more likely extends into adjacent structures, such as the orbit or other paranasal sinuses [10]. Radiologically, they are reported to show a ground glass appearing (GGA) area surrounded by hyper osseous parts on computed tomography (CT) scan and have enhancement on MRI; however, differentiating them solely based on radiological findings is difficult because these findings can be shared between osteoma and OObF.

Here, we report a case of giant osteoma with unusual blood supply on 4-dimensional (4D)-magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) with a review of related literature.

Case report

A 57-year-old male patient presented with a chronic headache and prolonged declined activity of daily living. Physical examination revealed a small solid protrusion on the middle of the forehead, decreased cognitive function, and olfactory loss. No other neurological dysfunction was observed. CT revealed a gigantic osseous tumor (7 × 84 × 65 mm) in the frontal fossa, apparently originating from the frontal sinus. The tumor, which was divided by falx cerebri, had 2 components: a GGA part in the front basal part and a peripheral hyper osseous part. The caudal part of the tumor extends to the ethmoidal sinus and the medial part of the left-sided orbital fossa (Fig. 1). MR imaging (MRI) revealed a compact component, as in cortical bone, with markedly low-signal on T1WI and T2WI, comparable to air, without contrast enhancement effect; GGA component showed low-signal intensity on T2WI, slightly lower than cerebral white matter and comparable to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) on T1WI, with a uniform enhancement effect on post-contrast. There was a mucocele posterior to the tumor, the surrounding of which was enhanced, and the frontal lobe was markedly compressed (Fig. 2). Gradual blood staining, from ethmoidal arteries, was observed in the front basal part of the tumor on 4D-MRA (Fig. 3). The patient underwent a bifrontal craniotomy. A mucus cyst with yellowish fluid within it was observed and removed in addition to the osseous tumor. Most parts of the tumor were removed by drilling. The GGA area was a little softer but still needed drilling compared to the peripheral hyper osseous part. The front basal part of the tumor was left for CSF leakage prevention, from which continuous oozing of blood was seen and requires extra caution in hemostasis.

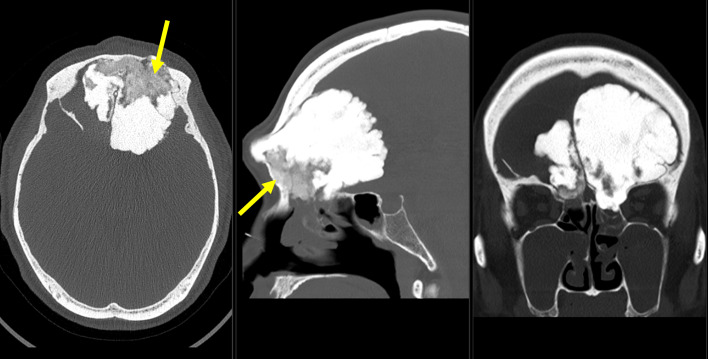

Fig. 1.

Axial, sagittal, and coronal view of head CT. A lobulated mass, 8.4 cm in length is seen just below the frontal bone. The tumor extends into the olfactory fossa and ethmoid sinus. The bilateral orbital walls are deformed, thinned, and partially missing. Most of the mass has a density equivalent to that of bone cortex, while the basal areas show a ground-glass density (arrows).

Fig. 2.

Axial view of brain MRI. (A):T2-weighted image, (B):T1-weighted image, (C): T1 with gadolinium. (A, B) The osseous tumor showed overall non to low intensity. Compact component, as in cortical bone, was low-signal on T1WI and T2WI, comparable to air; ground glass appearing component was low-signal on T2WI, slightly lower than cerebral white matter, and comparable to CSF on T1WI. A fluid retention was seen between the lesion and the brain parenchyma. The fluid content showed mixed intensity. The brain parenchyma is strongly compressed by lesions mentioned above. (C) Slight enhancement was observed on the ground-glass area (arrow), high enhancement was seen along this fluid-filled lumen (arrowhead).

Fig. 3.

Sagittal view of Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI (A) and 4D-MR angiography (B). Gradual tumor staining in the basal part of the tumor was observed (arrows), which was consistent to the enhanced area.

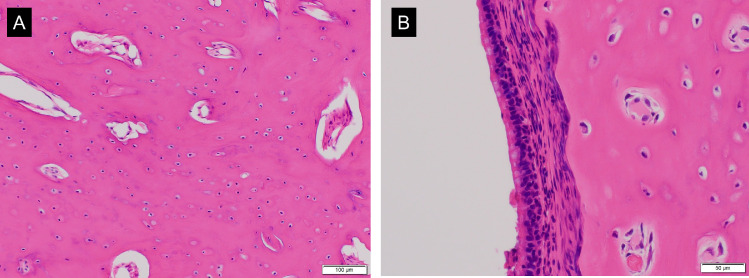

Histopathologic examination with hematoxylin-eosin staining revealed osteocytes in the compact bone and mucus attachment on the surface of the tumor (Fig. 4). The patient was diagnosed with osteoma. The cognitive function improved 2 months postoperatively, and the patient was transferred to a rehabilitation hospital for further improvement.

Fig. 4.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining of the tumor. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining showed osteocytes in the compact bone with little fibrous stroma observed. (B) Mucus membrane was attached to the surface of the tumor. (hematoxylin and eosin staining, magnification: A, ×200; B, ×400).

Discussion

Osteoma is the most common osseous tumor in the sinonasal cavities, mostly affecting the frontal sinus, followed by ethmoidal and maxillary sinus [3,10]. Small lesions are asymptomatic in most cases [3], while large ones, to the maximum of 80 mm are also reported [7,10], and may show intracranial or intraorbital expansion and coexistence with mucocele [5,6,14]. Radiologically, paranasal osteoma shows a very dense osseous lesion with or without less dense areas [3,10]. Enhancement might be observed in occasional cases [15], but even giant osteomas did not show any enhanced effect on the osseous part with enhancement only in the mucocele [6,16]. Several studies reported on paranasal osteoma [3,7,10,17,18], but none reported on its blood flow [19].

Differential diagnosis includes osteoblastoma, which is usually seen in the vertebra or long bone of lower extremities, and its intracranial involvement is rare [2,20,21], but intracranial cases where malignant transformation into osteosarcoma occurred has been reported [8,9]. Its radiographic features include a well-demarcated osteolytic appearance, distinctive hypervascularity, and gadolinium enhancement [2,20,22]. OObF has been described as osteoma which partially contains pathological findings similar to those of osteoblastoma [10,12,13]. The characteristic imaging features include the GGA areas where the tumor is thought to have originated, demarcated by dense bone around it [10,12,13,23], and with enhancement [23]. Radiologically, the tumor of the current case did not contradict these OObF findings.

Osteoma can be divided into 3 categories based on a histological point of view: ivory, mature, or mixed ivory/mature type, according to predominant components. The ivory type is predominantly composed of mature lamellar bone with little stroma, while the mature type consists of trabeculae of mature lamellar bone with or without osteoblastic rimming and fibrous stroma [10]. Conversely, OObF is characterized by anastomosing bone trabeculae with enlarged osteoblasts, loose fibrous stroma, and abundant small vessels [10,13], and this part corresponds to the GGA area in radiology. The tumor of our patient did not have such fibrous stroma, osteoblasts, or vessels; thus, it can be categorized as ivory type osteoma. We pathologically confirmed every excisional lesion but could not diagnose OObF because osteoblastoma has no component although OObF has a pathological concept [10,13]; therefore, we pathologically diagnosed osteoma.

The recurrence rate of osteoma varies from 0% to 27% over a mean follow-up of 42.4-69 months postoperatively [7,10]. The difference in the rate could be due to the removal rate. Jonathan et al. showed a higher recurrence rate in osteoma compared to OObF (27% vs 8%) although osteoma had a lower rate of residual tumors than OObF (14% vs 25%) [10]. The activity might be more aggressive because the osteoma of the current case showed an unusual finding of contrast effect and blood flow on 4D-MRA.

This case report has a limitation, which may be the sampling error; however, among “osteoma tumors,” cases revealed contrast and blood flow upon diagnosis, and extra caution is needed in performing hemostasis if the GGA with blood supply is left.

Conclusion

We report a case of giant osteoma arising from the frontal sinus with enhancement and blood supply. The front basal part of the tumor was preserved to not cause postoperative meningitis from CSF leakage, and hemostasis of the residual tumor needed extra caution. The full picture, including prognosis, of osteoma with contrast and blood flow remained unknown and required careful follow-up.

Patient consent

Written informed consent to publish this case report and use anonymized radiologic material was obtained from the patient.

Ethics declarations

The current study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of University of Tsukuba Hospital. The institutional review board of the University of Tsukuba Hospital approved the study protocol (R01-202).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: None.

References

- 1.Izci Y. Management of the large cranial osteoma: experience with 13 adult patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005;147(11):1151–1155. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0605-4. discussion 1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen GP, Rosenberg AE. Update on bone forming tumors of the head and neck. Head Neck Pathol. 2007;1(1):87–93. doi: 10.1007/s12105-007-0023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Earwaker J. Paranasal sinus osteomas: a review of 46 cases. Skelet Radiol. 1993;22(6):417–423. doi: 10.1007/BF00538443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakamoto H, Tanaka T, Kato N, Arai T, Hasegawa Y, Abe T. Frontal sinus mucocele with intracranial extension associated with osteoma in the anterior cranial fossa. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2011;51(8):600–603. doi: 10.2176/nmc.51.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunardi P, Missori P, Di Lorenzo N, Fortuna A. Giant intracranial mucocele secondary to osteoma of the frontal sinuses: report of two cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1993;39(1):46–48. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(93)90109-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Manen SR, Bosch DA, Peeters FL, Troost D. Giant intracranial mucocele. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1995;97(2):156–160. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(94)00068-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giotakis E, Sofokleous V, Delides A, Razou A, Pallis G, Karakasi A, et al. Gigantic paranasal sinuses osteomas: clinical features, management considerations, and long-term outcomes. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(5):1429–1441. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06420-x. eCollection 2021 May 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figarella-Branger D, Perez-Castillo M, Garbe L, Grisoli F, Gambarelli D, Hassoun J. Malignant transformation of an osteoblastoma of the skull: an exceptional occurrence. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1991;75(1):138–142. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.1.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraft CT, Morrison RJ, Arts HA. Malignant transformation of a high-grade osteoblastoma of the petrous apex with subcutaneous metastasis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2016;95(6):230–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McHugh JB, Mukherji SK, Lucas DR. Sino-orbital osteoma: a clinicopathologic study of 45 surgically treated cases with emphasis on tumors with osteoblastoma-like features. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(10):1587–1593. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165-133.10.158710.5858/133.10.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans M, Priddy N, Tran B. Report of 3 cases of pediatric sinus osteomas with osteoblastoma-like features. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15(7):955–960. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmer LM, Kissel P, Ragsdale BD. Frontal sinus osteoma with osteoblastoma-like histology and associated intracranial pneumatocele. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(3):384–388. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0332-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCann JM, Tyler D, Jr., Foss RD. Sino-orbital osteoma with osteoblastoma-like features. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9(4):503–506. doi: 10.1007/s12105-015-0613-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen S, Nadeau S. Giant frontal sinus osteomas: demographic, clinical presentation, and management of 10 cases. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2019;33(1):36–43. doi: 10.1177/1945892418804911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koeller KK. Radiologic features of sinonasal tumors. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0686-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajima Y, Yoshimine T, Ogawa M, Takanashi M, Nakamuta K, Maruno M, et al. A giant intracranial mucocele associated with an orbitoethmoidal osteoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2000;92(4):697–701. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.4.0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panagiotopoulos V, Tzortzidis F, Partheni M, Iliadis H, Fratzoglou M. Giant osteoma of the frontoethmoidal sinus associated with two cerebral abscesses. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43(6):523–525. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng KJ, Wang SQ, Lin L. Giant osteomas of the ethmoid and frontal sinuses: clinical characteristics and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2013;5(5):1724–1730. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farah RA, Poletti A, Han A, Navarro R. Giant frontal sinus osteoma and its potential consequences: illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2021;1(21) doi: 10.3171/CASE21105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang K, Yu F, Chen K, et al. Osteoblastoma of the frontal bone invading the orbital roof: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(42):e12803. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park YK, Kim EJ, Kim SW. Osteoblastoma of the ethmoid sinus. Skelet Radiol. 2007;36(5):463–467. doi: 10.1007/s00256-006-0269-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cekic B, Toslak IE, Yildirim S, Uyar R. Osteoblastoma originating from frontoethmoidal sinus causing personality disorders and superior gaze palsy. Niger J Clin Pract. 2016;19(1):153–155. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.173706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yazici Z, Yazici B, Yalcinkaya U, Gokalp G. Sino-orbital osteoma with osteoblastoma-like features: case reports. Neuroradiology. 2012;54(7):765–769. doi: 10.1007/s00234-011-0973-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]