Abstract

Purpose

This study highlights the advantages and disadvantages of Anterolateral Thigh (ALT) free flap using the brachial artery as the recipient vessel in large posterior defects of the elbow with early mobilization.

Methods

Eight patients with a soft tissue defect on the posterior elbow underwent reconstruction with an ALT free flap. Average age and follow-up were 29.5 years (range, 18–43 years) and 54 months (range, 35–76 months), respectively. All defects were on the posterior side, and brachial arteries on the anterior side were used as the recipient artery in all cases. Four defects were created by tumor excision, four were exposed with hardware after fixation of distal humeral and/or proximal ulna fractures. The dimensions of defects were between 80 and 352 cm2. Cases were evaluated according to function (ROM), complications, tissue quality anticipated from reconstruction and immobilization time after the reconstruction.

Results

All flaps except one survived and met the tissue quality anticipated from this reconstruction. In the bigger flaps, an apparent ugly scar at the donor site was the main problem. The flap on the posterior, and recipient artery on the anterior had no adverse effects on early motion of the elbow. Two cases with fractures had minimal restriction of elbow movement due to post-traumatic stiff elbow. There was one case of partial flap loss after myocardial infarction. After the patient was medically stable, the remaining distal defect was closed with a pedicled radial forearm flap.

Conclusion

ALT free flap has numerous advantages in covering defects at the posterior elbow such as being pliable, thin and durable skin, with a long and reliable pedicle reaching the brachial artery without causing any problem in early motion and surgical reconstruction can be easily completed in the supine position.

Keywords: Anterolateral thigh flap, Defect soft tissue, Elbow, Reconstructive surgical procedures

Introduction

Most elbow soft tissue defects which require soft tissue coverage are located posteriorly which means the ulna and ulnar nerve are exposed. The soft tissue prerequisites of this area are that it should be thin, pliable, durable and able to withstand repetitive flexion and extension [1, 2]. In addition, early or immediate range of motion of the elbow joint is essential in trauma cases which have hardware for fixation of fractures [1]. Other possible covering options for large (> 40 cm2) elbow defects are radial forearm flap, latissimus dorsi flap, scapular, parascapular and lateral arm flap. Despite the multiple options for coverage of defects, especially distal to olecranon with exposed ulnar shaft, the anterolateral thigh flap (ALT) with its long pedicle has several advantages for large defects because a pedicled latissimus dorsi flap cannot reach this region safely and the radial forearm may not provide sufficient coverage due to its inadequate size. There are a limited number of articles in literature about the use of ALT free flap for the closure of posterior elbow defects [1–3].

This study points out clinical results, complications and the possibility of early motion of the elbow joint after reconstruction using ALT free flap with the brachial artery as recipient vessel in the coverage of large posterior defects of the elbow.

Methods

A retrospective review was made of 8 patients who underwent reconstruction with an ALT free flap for large soft tissue defects in the posterior elbow before March 2011. The average age was 29.5 years (range, 18–43 years) and the mean follow-up period was 54 months (range, 35–76 months). In all patients, the defects were on the posterior side, around and distal to the olecranon. The dimension of the defects varied between 80 and 352 cm2 and were considered large for this area.

Four defects were created by malignant or benign tumor excision and were from exposed hardware after fixation of distal humeral and/or proximal ulnar fractures. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients and the results of the study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of cases

| Case | Age | Sex | Etiology | Defect size (cm2) | Follow-up duration (months) | Preop flexion/extension | Postop flexion/extension | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | M | Giant hemangioma of skin | 350 | 42 | 140/0 | 140/0 | No |

| 2 | 18 | M | Exposure of hardware both ulna and distal humerus | 100 | 35 | 145/0 | 145/10 | No |

| 3 | 40 | M | Soft tissue malignant fibrous histiocytoma | 125 | 57 | 140/0 | 140/0 | No |

| 4 | 25 | M | Exposure of hardware ulna | 90 | 62 | 140/0 | 140/0 | No |

| 5 | 22 | M | Hemangioma of skin | 80 | 75 | 145/0 | 145/0 | No |

| 6 | 30 | M | Exposure of hardware ulna | 80 | 61 | 140/0 | 140/15 | No |

| 7 | 38 | M | Exposure of hardware ulna | 80 | 54 | 140/0 | 140/0 | No |

| 8 | 43 | M | Defect over olecranon due to trauma | 110 | 46 | 145/0 | 130/30 | Peroperative myocardial infarct, partial flap loss |

Surgical Technique

The ALT free flaps were harvested including the fascia to augment durability for repetitive flexion and extension as mentioned in previously published reports [4]. The brachial artery and deep venous system on the anterior side were used as a recipient artery and vein in all cases. A loose medial supra medial epicondylar subcutaneous tunnel was used to deliver the flap pedicle to the anterior side and anastomoses were performed proximal to the anterior flexor crease of the elbow via a separate anterior incision (Fig. 1). It was also attempted to provide a tension-free anastomosis flap at the posterior recipient artery and veins at the anterior side. Alternative to the brachial artery is using the profunda brachii artery as recipient vessel. This vessel has a good size match for the ALT, is easy to harvest on the lateral side of the arm, and an end-to-end anastomosis can be performed. There are risks of performing end-to-side anastomosis into brachial artery such as possible brachial artery thrombosis leading to ischemia of forearm and hand. All reconstructions were performed by the same author.

Fig. 1.

Skin incision at the antecubital fossa to prepare the brachial artery and deep venous system, which were used as recipient artery and vein

The cases were evaluated according to the tissue quality anticipated from the reconstruction, the initiation of elbow motion, function (Range of motion of the elbow and forearm) and all complications. A descriptive analysis of the continuous and categorical data was performed using proportions, frequency distributions, means, and standard deviations. No statistical analysis was performed in this descriptive study.

Results

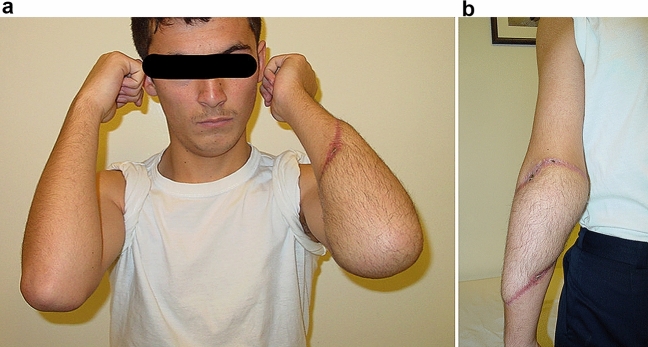

The patient group who underwent reconstruction was relatively young and very active. The mean age was 29.5 years (range, 18–43 years) and the mean follow-up was 54 months (range, 35–76 months) All cases were male, and the average defect size was 125 cm2 (range, 80–352 cm2) with a location around the olecranon and proximal ulna (Fig. 2a, b). In all cases, tension-free anastomosis was possible with mean 12 cm (range, 8–15 cm) of pedicle length out of the flap used for tension-free anastomosis (Fig. 3). Seven of the 8 flaps survived. All surviving flaps met the tissue quality anticipated from this reconstruction in terms of pliable and durable skin. There were no skin problems around the olecranon or along the ulnar shaft in daily use of the elbow during the follow-up period even without hardware removal. The flap on the posterior, and the recipient artery on the anterior side with tension-free anastomosis had no adverse effects on early range of elbow motion. If the ALT free flap was uneventful during the early postoperative period, gentle elbow motion was allowed on the fourth day. Range of motion exercises were allowed in all tumor cases on the fourth day. The mean elbow immobilization period was 8 days (range, 4–15 days), and after 3 weeks postoperatively, there was no restriction on elbow movement, including the trauma cases. All tumor cases and one trauma case had full ROM of elbow and forearm joint when compared with the uninjured contralateral side in the early follow–up at 6 weeks postoperatively (Fig. 4a, b). Two cases had minimal restriction of the elbow but normal forearm motion due to fracture complications, but both were still in the functional arc of elbow joint motion (30°–130°) [5].

Fig. 2.

a The defect after debridement. b Intraoperative view of the defect after debridement

Fig. 3.

Pedicle (10 cm) of the ALT flap

Fig. 4.

a Full flexion/extension at 6 weeks. b Full flexion/extension at 6 weeks

Complications

Partial flap failure was seen in 1 patient. Reconstructive surgery was uneventfully completed in this 43-year-old multitrauma patient, who then had a myocardial infarction in the recovery period and was transferred emergently to the Coronary Intensive Care Unit (CICU). Probably due to catecholamine release, the flap was fully white and pale showing arterial insufficiency (Fig. 5a). Emergency coronary angiography was performed, and a coronary stent was placed for the infarction. When the global perfusion and blood pressure normalized, the patient became hemodynamically stable after the angiography in CICU, and the circulation of the flap gradually improved but unfortunately, partial necrosis of the ALT flap had occurred (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

a Postoperatively the flap was completely white and pale showing arterial insufficiency. b Partial necrosis of the ALT flap

The partially necrotic flap was left on the defect for 6 weeks while awaiting cardiac stability of the patient. The defect and partially necrotic flap gradually became smaller, and the patient also had substantial weight loss resulting in the loosening of subcutaneous tissue during this critical period (Fig. 5b). This failed case was successfully reconstructed using antegrade pedicled radial forearm flap as a secondary flap 6 weeks after MI.

Discussion

There are many options available to reconstructive surgeons for the coverage of defects especially in the posterior of the elbow. These include, radial forearm flap, pedicled latissimus dorsi flap and free tissue transfer [1, 2]. Moreover, Ramadevi and Kumar successfully applied the pedicle thoracoumbilical flap to cover the soft tissue defect around the elbow in cases with recipient vessel problems [6].

The LD is a large muscle with a wide arc of rotation. It can be used as a pedicle flap for defects around the elbow. Ooi and Ng et al. have described LD to be the workhorse flap for elbow reconstruction [7]. However, extending the latissimus dorsi beyond the olecranon may compromise the flap and also require extended periods of immobilization [1–3].

Haquebord et al. in a retrospective study of 18 pedicled latissimus dorsi flaps for post-traumatic elbow defects, experienced 3 partial necrosis and 1 complete flap loss [8]. The ultimate choice of flap coverage depends on a number of variables, including the size of the wound, exposure of vital structures, comorbid conditions and potential donor site morbidity [1–3]. Free flap coverage would seem to be preferable, if the posterior elbow defect size is large and situated around or distal to the olecranon with exposed ulnar shaft and nerve. The chosen free flap should cover the prerequisites of this area and also allow early motion without endangering the flap. Therefore, fasciocutaneous free flaps favorable for this area include anterolateral thigh, scapular, parascapular and lateral arm flaps.

The anterolateral thigh flap has several advantages over other free flaps especially for the coverage of the posterior elbow. The ALT free flap can be easily raised in a supine position without any need for patient positioning during surgery and the flap has a long and reliable vascular pedicle with an acceptable large lumen. The flap has durable, pliable and thin soft tissue, especially in young, active males and an irregular shape and large size can also be raised as required. Primary closure of the donor site is possible if the skin paddle is ≤ 7 to 9 cm wide, but the donor site is skin grafted if a larger skin paddle is needed. The main disadvantage of a large ALT flap is an ugly scar at the large donor site which needs skin grafting even if it can be hidden under clothes during daily life [1, 2, 9].

In this retrospective review, seven of eight flaps survived (87.5%). The range of elbow and forearm motion in 5 cases was normal when compared with the uninjured contralateral side without any restriction. However, 2 cases had minimal restriction of elbow motion due to the bone injury, but both were still in the functional arc of the elbow joint (30°–130°) [5]. In fact, in our opinion and experience, the absolute stability of fracture fixation dictates the postoperative rehabilitation period, not the flap reconstruction. All surviving flaps completely met the tissue quality anticipated from this reconstruction in terms of pliable and durable skin (Fig. 6). There were no skin problems around the olecranon or along the ulnar shaft in daily use of the elbow during the follow-up period even without hardware removal. Including fascia with the flap may augment durability by opposing the shearing force in this area in daily activities.

Fig. 6.

Final result at 6 years

Tension-free anastomosis is the cornerstone of this procedure. The flap on the posterior side and the recipient artery on the anterior side with tension-free anastomosis had no adverse effects on early range of elbow motion. All anastomoses were performed just superior to the flexor crease of the elbow and a medial loose tunnel just superior to the medial epicondylar prominence was preferred in all cases. Therefore, pedicle length is quite important. If the perforator entrance to the flap is located eccentrically during flap design, the pedicle can be elongated, and an ALT flap offers the possibility of extending the pedicle length. In our experience it is not difficult to obtain a 10–12 cm pedicle, which is sufficient for anastomosis without using a vein graft (Fig. 3). The exact anastomosis site for tension-free anastomosis should be tested by flexion–extension of the elbow joint. This should be mandatory after flap in setting and delivering the pedicle to the anastomosis site, even when the detailed plan seems perfect. Gentle elbow motion was allowed on the fourth day in this series, but this cannot be taken as a general rule.

In obese patients, due to the thickness of the ALT flap its pliability is reduced, and it may not allow early range of elbow motion and reasonable reconstruction. Thinner free flaps may be preferred in obese patients. As a result, the ALT free flap may not be thin in all cases and the flap may therefore require thinning. However, flap thinning can be considered risky due to the possible complications of flap necrosis, pedicle division, hematoma and nerve damage [9]. In this case series, all the cases were young, active males so there was no need for flap thinning. In cases where ALT flap thinning is required, subfascial dissection of ALT flaps has been shown to be the safest method for thinning with minimum vascular complications, which account for a 3.1% probability of marginal necrosis, and can be managed conservatively [10]. However, marginal necrosis in elbow coverage easily impairs the postoperative protocol, especially in trauma cases.

The failed “myocardial infarction” case in this series had a highly unpredictable course and the case was followed up under observation without any type of invasive surgical attempt. The patient had distal flap loss and thus this defect was able to be covered with a radial forearm flap. If the patient with the myocardial infarction had proximal flap loss, a radial forearm flap would not be able to reach the defect. In such a case, it would be more logical to choose a pedicled latissimus dorsi flap. A pedicled latissimus dorsi flap may be reasonable, especially in proximal arm defects extending to the elbow where there are no reliable recipient vessels. The metabolic and pathological events of both the flap and the patient after the reconstruction could be of interest for a further case report but are not the issue of this paper. Nevertheless, the partially failed case demonstrates the reliability and robustness of the ALT flap. An antegrade pedicled radial forearm flap for secondary reconstruction performed well in this patient with some motion restriction due to the bone injury.

There were no donor site problems in any cases. An apparent ugly scar at the donor site is the major point of concern in this procedure because all donor sites needed skin grafting (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Donor site at 6 weeks

This case series highlights the utility of ALT free flaps in the coverage of large posterior elbow defects especially distal to the olecranon. Jensen and Moran recommended using radial forearm flap or free flap for large defects ≥ 40 cm2 especially those located distal of the olecranon and pedicled LDF or free flap for large defects ≥ 40 cm2, located proximal of the olecranon [2]. Therefore, the ALT free flap was preferred for the large defects in this case series. The antegrade radial forearm flap is not generally suitable for such large defects and pedicled LDF has high complication rates when used distal to the olecranon [1, 2, 11]. In addition, the ALT free flap has numerous advantages in covering defects at the posterior elbow such as pliable, thin and durable skin. Harvesting of ALT flap is more convenient for the surgeon because it usually does not require a change in the patient’s position during surgery and it can be harvested at the same time as the recipient-site procedure, unlike scapular, parascapular, and latissimus dorsi flaps [4].

The ALT free flap offers the options of using muscle, nerve and fascia, which helps surgeons to reconstruct the upper extremity as needed. Vascularised vastus lateralis muscle can be used to obliterate dead space and to struggle against infection. We did not take the flap with the muscle because there was no dead space and infection in our cases. The ALT free flap provides a vascular bed for nerve grafts, avoids infection and helps in accessing fascia lata grafts for reconstruction of the tendon in the upper extremity [12–15].

The major limitation of this study is the small number of patients. However, as ALT free flap coverage for large defects of the posterior elbow may not be a frequently performed procedure, even eight elbow reconstructions can be considered a sufficient series when compared to other reports in current literature [12–15]. The lack of a control group may be accepted as another limitation.

Conclusion

Anterolateral thigh flap presents an excellent option for covering large defects in the posterior elbow. The flap provides thin, pliable and durable skin, a long and reliable pedicle reaching the brachial artery, does not cause any problems in early motion and surgical reconstruction is easily completed in the supine position. A disadvantage of this reconstruction is the apparent ugly scar at the donor site, which is a major point of concern, even in experienced hands. The long-term functional and esthetic results were good in this series. The ALT free flap can be recommended as the workhorse flap for the coverage of large defects in the posterior elbow.

Acknowledgements

We did not receive any contributions from anyone.

Author Contributions

UB: conceived and design the analysis, wrote the paper. YY: wrote the paper, collected the data. SSB: performed operations. MA: performed operations, wrote the paper.

Funding

We have no financial biases.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors have no potential conflicts of interest, including financial interests, activities, relationships, and affiliations, to disclose.

Ethical Standard Statement

We obtained ethical approval from review board of Ankara University Faculty of Medicine.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Uğur Bezirgan, Email: ugurbezirgan@gmail.com.

Yener Yoğun, Email: yogunyener@gmail.com.

Sırrı Sinan Bilgin, Email: ssbilgin@yahoo.com.

Mehmet Armangil, Email: mehmetarmangil@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Choudry UH, Moran SL, Li S, Khan S. Soft-tissue coverage of the elbow: An outcome analysis and reconstructive algorithm. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2007;119:1852–1857. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000259182.53294.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen M, Moran SL. Soft tissue coverage of the elbow: A reconstructive algorithm. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 2008;39:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevanovic M, Sharpe F. Soft-tissue coverage of the elbow. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2013;132:387e–402e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829ae29f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei F, Jain V, Celik N, et al. Have we found an ideal soft-tissue flap? An experience with 672 anterolateral thigh flaps. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2002;109:2219–2226. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ljungquist KL, Beran MC, Awan H. Effects of surgical approach on functional outcomes of open reduction and internal fixation of intra-articular distal humeral fractures: A systematic review. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2012;21:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramadevi V, Kumar KS. Pedicle thoracoumbilical flap for soft tissue coverage defects around elbow region. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2019;18:2327. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ooi, A., Ng, J., Chui, C., Goh, T. & Tan, B. K. (2016). Maximizing outcomes while minimizing morbidity: an illustrated case review of elbow soft tissue reconstruction. Plastic Surgery International, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Hacquebord JH, Hanel DP, Friedrich JB. The pedicled latissimus dorsi flap provides effective coverage for large and complex soft tissue injuries around the elbow. The Hand. 2018;13:586–592. doi: 10.1177/1558944717725381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura N, Satoh K. Consideration of a thin flap as an entity and clinical applications of the thin anterolateral thigh flap. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1996;97:985–992. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199604001-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agostini T, Lazzeri D, Spinelli G. Anterolateral thigh flap thinning: Techniques and complications. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2014;72:246–252. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31825b3d3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevanovic M, Sharpe F, Thommen VD, et al. Latissimus dorsi pedicle flap for coverage of soft tissue defects about the elbow. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 1999;8:634–643. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(99)90104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chui CH-K, Wong C-H, Chew WY, et al. Use of the fix and flap approach to complex open elbow injury: The role of the free anterolateral thigh flap. Archives of Plastic Surgery. 2012;39:130. doi: 10.5999/aps.2012.39.2.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Momeni A, Kalash Z, Stark GB, Bannasch H. The use of the anterolateral thigh flap for microsurgical reconstruction of distal extremities after oncosurgical resection of soft-tissue sarcomas. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 2011;64:643–648. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koshima I, Nanba Y, Tsutsui T, et al. Vascularized femoral nerve graft with anterolateral thigh true perforator flap for massive defects after cancer ablation in the upper arm. Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery. 2003;19:299–302. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muneuchi G, Suzuki S, Ito O, Saso Y. One-stage reconstruction of both the biceps brachii and triceps brachii tendons using a free anterolateral thigh flap with a fascial flap. Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery. 2004;20:139–142. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-820769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]