Abstract

Background

In the present study, the first aim was to compare the accuracy of three guidelines in the diagnosis of thyroid nodule malignancy. The second purpose was to find sonographic features potentially associated with the risk of malignancy.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, we prospectively recruited patients referred with a diagnosis of thyroid nodule (≥ 1 cm) for fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Sonographic features were recorded and scored according to the American Thyroid Association (ATA-2015), the American College of Radiology-Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (ACR-TIRADS), and the Korean TIRADS (K-TIRADS). FNA was conducted and cytological findings were reported.

Results

A total of 984 thyroid nodules were ultimately included, of which 144 (14.6%) were malignant and 840 (85.4%) were benign. The accuracy of ACR-TIRADS categories TR5 and TR4/5 was 88.3% and 69.3%, respectively. This rate for ATA-2015 classes High suspicion and Intermediate suspicion/High suspicion was 87.9% and 80.4%, respectively. For K-TIRADS classes 5 and 4/5, the diagnostic accuracy was 88.0% and 80.6%, respectively. The rate of unnecessary FNA was highest with ATA-2015 and K-TIRADS guidelines (53.9% and 53.7%, respectively), followed by ACR-TIRADS (32.0%). Significant direct associations were observed between malignancy and hypoechogenicity (odds ratio [OR] 5.78), fine calcification (OR = 6.7), rim calcification (OR = 2.56), ill-defined margin (OR = 3.31), and irregular margin (OR = 6.95).

Conclusions

There are different strengths of ACR-TIRADS, K-TIRADS, and ATA-2015 guidelines in the prediction of malignant thyroid nodules, and clinicians and radiologists should consider these differences in the management of thyroid nodules.

Keywords: Ultrasonography, Fine-needle aspiration, Biopsy, Cytology

Introduction

Thyroid nodules are usually asymptomatic and are frequently found in clinical practice and/or imaging evaluations, but it is noteworthy that up to 15% of nodules can be malignant [1, 2]. Consequently, discriminating between benign and malignant nodules is important but also a significant challenge for clinicians. In this regard, thyroid sonography with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is presently recommended as the first diagnostic step [3]. However, differences in subjective assessment of imaging findings by radiologists can potentially cause misdiagnosis or overtreatment. Thus, the Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TIRADS) was proposed on the basis of various sonographic features of thyroid nodules to help in objective detection, as well as in prevention of FNA overuse [4].

It has been over a decade since TIRADS was first established, and since then different versions of this system have been developed, such as the American College of Radiology TIRADS (ACR-TIRADS) and the Korean TIRADS (K-TIRADS) [5–7]. In addition to TIRADS, there are other guidelines widely used by clinicians for diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules, such as that of the American Thyroid Association (ATA) [8]. These guidelines have different characteristics with various diagnostic accuracy measures for distinguishing benign nodules from malignant ones [9, 10]. In the present study, we first aimed to compare the accuracy of these guidelines in the diagnosis of thyroid nodule malignancy in order to provide clinical evidence for suggestion of the most appropriate system. Secondly, we tried to find sonographic features potentially associated with the risk of malignancy.

Methods

Locations and patients

In this prospective cross-sectional study, we consecutively recruited patients referred to the clinics of Shahid Beheshti teaching hospital or private offices in Babol, northern Iran, with a diagnosis of thyroid nodules for FNA during February 2019–April 2021. The nodules were diagnosed in a thyroid examination by an endocrinologist. Exclusion criteria were nodules smaller than 1 cm, purely cystic nodules without a solid focus, unwillingness to perform FNA, and suspected cytology results (atypical diagnosis).

Sonographic examination

Sonography of thyroid nodules was performed by two senior radiologists (MN and RM) before the FNA procedure using a Samsung H60 ultrasound machine with a 3–14 MHz linear probe. The following ultrasonographic features were documented for all nodules: size, composition (solid, solid-cystic), echogenicity (hyperechogenicity, hypoechogenicity, isoechogenicity), calcification (fine calcification, coarse calcification, rim calcification, none), margins (regular, irregular, ill-defined), and nodule shape (taller-than-wide, wider-than-tall). Considering the ultrasonographic features of each thyroid nodule, we categorized the nodule as per ACR-TIRADS [5, 11], K-TIRADS (proposed by the Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology) [7], and ATA-2015 [8] guidelines, separately.

ACR-TIRADS is scored on the basis of ultrasound features of composition, echogenicity, shape, margin, and echogenic foci, and it is categorized as follows: TR1 (benign, aggregate risk level 0.3%), TR2 (non-suspicious, aggregate risk level 1.5%), TR3 (mildly suspicious, aggregate risk level 4.8%), TR4 (moderately suspicious, aggregate risk level 9.1%), and TR5 (highly suspicious, aggregate risk level 35.0%).

Regarding K-TIRADS, ultrasound features of solid component, irregular margins, hypoechogenicity, taller-than-wide shape, and microcalcifications are suggestive of nodule malignancy. This system is categorized as follows: K-TIRADS 2 (Benign, malignancy risk of < 3%), K-TIRADS 3 (Low suspicion, malignancy risk of 3–15%), K-TIRADS 4 (Intermediate suspicion, malignancy risk of 15–50%), and K-TIRADS 5 (High suspicion, malignancy risk of > 60%).

According to ATA-2015, hypoechogenicity, irregular margins, microcalcifications, rim calcifications, and taller-than-wide shape are defined as ultrasound features of high suspicion for malignancy. This system is categorized as follows: Benign (malignancy risk of < 1%), Very low suspicion (malignancy risk of < 3%), Low suspicion (malignancy risk of 5–10%), Intermediate suspicion (malignancy risk of 10–20%), and High suspicion (malignancy risk of < 70–90%).

FNA and cytology

The ultrasound-guided FNA was conducted by a senior radiologist (MN) with more than 15 years of experience in performing the procedure, using a 5-cc plastic syringe attached to a 23-gauge needle. The aspiration was conducted from the solid area of the nodules if solid-cystic nodules were present. The specimens were then smeared on microscope glass slides, dried in the air, and fixed with 95% ethanol. Finally, they were stained using the Papanicolaou, Giemsa and hematoxylin–eosin methods. The cytological assessment was performed by two pathologists with more than 15 years of experience in the procedure, and the final decision was made with consensus. The pathologists were blinded to the sonographic diagnosis of the thyroid nodules in order to control the bias.

Statistical analyses

The obtained data primarily underwent descriptive analysis. For measuring the performance of the three ultrasound classification systems (ACR-TIRADS, ATA-2015, K-TIRADS) in the diagnosis of malignant thyroid nodules, the contingency table values were defined as follows:

True positive (TP): Both ultrasound and cytology corresponded with malignant nodule.

True negative (TN): Both ultrasound and cytology corresponded with benign nodule.

False positive (FP): Ultrasound was suggestive of malignant nodule, but cytology corresponded with benign nodule.

False negative (FN): Ultrasound was suggestive of benign nodule, but cytology corresponded with malignant nodule.

Sensitivity was calculated as TP/TP + FN, specificity as TN/TN + FP, positive predictive value (PPV) as TP/TP + FP, negative predictive value (NPV) as TN/TN + FN, and accuracy as a proportion of TP + TN in all patients. A receiver operator characteristics (ROC) analysis was also used to estimate the ability of the three ultrasound classification systems to predict malignancy, as estimated by the area under the curve (AUC). We conducted the above-mentioned analyses for cut-off values of 4 and 5 for each guideline, separately.

The association between sonographic features and malignancy was initially assessed using the chi-squared test; then, the features with significant association were entered into the multivariable logistic regression analysis. The results were presented as an odds ratio (OR) along with a 95% confidence interval (CI). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical issues

The study protocol was initially explained to the patients, and then written informed consent was collected from all of them. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Babol University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.MUBABOL.REC.1400.182). The patients’ information was kept confidential.

Results

A total of 844 patients with thyroid nodules were included; of these, 792 had a single nodule and the others had multiple nodules. Overall, 1021 thyroid nodules were initially assessed, of which 37 had atypical diagnoses according to cytology and were excluded from further investigation. In total, 984 thyroid nodules were ultimately included in the study. Out of 807 patients, 170 (21.1%) were male and 637 (78.9%) were female. The mean age was 45.58 ± 13.21 years. The mean size of the thyroid nodules was 2.02 ± 1.06 cm. Of the 984 nodules, 144 (14.6%) were malignant and 840 (85.4%) were benign. Cytology findings proved that 91.7% (n = 132) of the malignant nodules were papillary thyroid carcinoma and others were follicular carcinoma.

Table 1 shows the distribution of benign and malignant nodules according to the three ultrasound classification systems. The prevalence of malignancy for ACR-TIRADS classes TR2-TR5 was 2.2%, 3.5%, 17.4%, and 62.0%, respectively. This rate for ATA-2015 classes Very low suspicion to High suspicion was 4.1%, 7.2%, 19.2%, and 48.6%, respectively. For K-TIRADS classes 2–5, the prevalence of malignancy was 4.1%, 7.2%, 21.3%, and 62.3%, respectively.

Table 1.

Distribution of benign and malignant thyroid nodules according to the three ultrasound classification systems

| Risk category | Benign nodules (n, [%]) | Malignant nodules (n, [%]) | Prevalence of malignancy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACR-TIRADSa | |||

| TR2 | 87 (10.4) | 2 (1.4) | 2.2 |

| TR3 | 470 (56.0) | 17 (11.8) | 3.5 |

| TR4 | 237 (28.2) | 50 (34.7) | 17.4 |

| TR5 | 46 (5.5) | 75 (52.1) | 62.0 |

| ATA-2015b | |||

| Very low suspicion | 94 (11.2) | 4 (2.8) | 4.1 |

| Low suspicion | 604 (71.9) | 47 (32.6) | 7.2 |

| Intermediate suspicion | 97 (1.5) | 23 (16.0) | 19.2 |

| High suspicion | 45 (5.4) | 70 (48.6) | 48.6 |

| K-TIRADSc | |||

| 2 | 94 (11.2) | 4 (2.8) | 4.1 |

| 3 | 606 (72.1) | 47 (32.6) | 7.2 |

| 4 | 100 (11.9) | 27 (18.8) | 21.3 |

| 5 | 40 (4.8) | 66 (45.8) | 62.3 |

aAmerican College of Radiology—Thyroid imaging reporting and data system

bAmerican Thyroid Association

cKorean thyroid imaging reporting and data system

The performance of the three ultrasound classification systems in the diagnosis of malignant nodules is listed in Table 2. The accuracy of ACR-TIRADS categories TR5 and TR4/5 was 88.3% and 69.3%, respectively. This rate for ATA-2015 classes high suspicion and Intermediate suspicion/High suspicion was 87.9% and 80.4%, respectively. For K-TIRADS classes 5 and 4/5, the diagnostic accuracy was 88.0% and 80.6%, respectively.

Table 2.

Diagnostic performance values of the three ultrasound classification systems for malignant thyroid nodules

| Risk category | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACR-TIRADSa | |||||

| TR5 | 52.1 | 94.5 | 62.0 | 92.0 | 88.3 |

| TR4 or TR5 | 86.8 | 66.3 | 30.6 | 96.7 | 69.3 |

| ATA-2015b | |||||

| High suspicion | 48.6 | 94.6 | 60.9 | 91.5 | 87.9 |

| Intermediate suspicion or High suspicion | 64.6 | 83.1 | 39.6 | 93.2 | 80.4 |

| K-TIRADSc | |||||

| 5 | 45.8 | 95.2 | 62.3 | 91.1 | 88.0 |

| 4 or 5 | 64.6 | 83.3 | 39.9 | 93.2 | 80.6 |

aAmerican College of Radiology—Thyroid imaging reporting and data system

bAmerican Thyroid Association

cKorean thyroid imaging reporting and data system

Figure 1 shows the ROC curve for the ability of the three ultrasound classification systems in predicting malignant thyroid nodules according to their categories. For category 5, the greatest predictive ability was related to ACR-TIRADS (AUC = 0.733), followed by ATA-2015 (AUC = 0.716), and K-TIRADS (AUC = 0.705). For category 4 or 5, the greatest predictive ability related to ACR-TIRADS (AUC = 0.766), followed by K-TIRADS (AUC = 0.740) and ATA-2015 (AUC = 0.738).

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of different ultrasound classification systems (category 5; category 4 or 5) for predicting thyroid nodule malignancy

In Table 3, the distribution of benign and malignant thyroid nodules by the three ultrasound classification systems according to their FNA biopsy criteria is summarized. Among 984 thyroid nodules, a total of 421 (42.8%), 649 (66.0%), and 647 (65.8%) FNA biopsies were recommended by ACR-TIRADS, ATA-2015, and K-TIRADS, respectively. It was also calculated that 38 (6.8%), 25 (7.5%), and 25 (7.4%) thyroid malignancies would be missed among non-FNA biopsies according to the corresponding systems. The rate of unnecessary FNA was highest with ATA-2015 and K-TIRADS guidelines (53.9% and 53.7%, respectively), followed by ACR-TIRADS (32.0%). Figures 2, 3, 4 show the ultrasound-guided FNA from thyroid nodules, along with risk stratification.

Table 3.

Distribution of benign and malignant thyroid nodules by the three ultrasound classification systems according to their fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy criteria

| System | N of FNA biopsies | N of benignity among FNA biopsies [A] | N of malignancy among FNA biopsies | N of missed malignancy among non-FNA biopsies | Unnecessary FNA biopsy rate [A/984] (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACR-TIRADS | 421 | 315 (74.8%) | 106 (25.2%) | 38 (6.8%) | 32.0 |

| ATA-2015 | 649 | 530 (81.7%) | 119 (18.3%) | 25 (7.5%) | 53.9 |

| K-TIRADS | 647 | 528 (81.6%) | 119 (18.4%) | 25 (7.4%) | 53.7 |

Fig. 2.

The ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration from a mild hypoechoic solid nodule with irregular margin, taller-than-wide shape, and incomplete rim calcification (ACR-TIRADS-5, ATA-2015-High suspicion, K-TIRADS-5), which was proved by cytology to be a papillary carcinoma

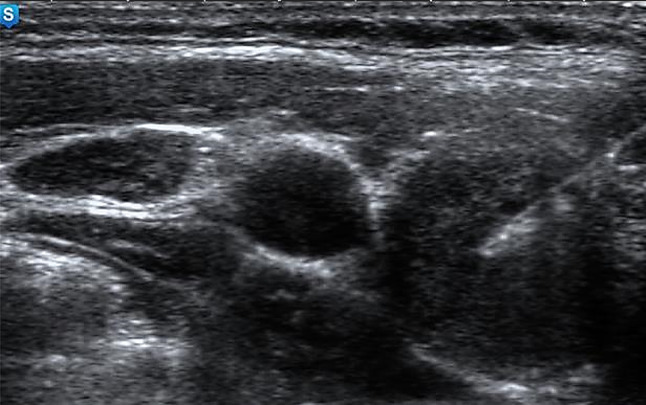

Fig. 3.

The ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration from a mildly hypoechoic solid nodule (ACR-TIRADS-4, ATA-2015-Intermediate suspicion, K-TIRADS-4), which was proved by cytology to be a nodular goiter

Fig. 4.

The ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration from a hypoechoic solid nodule with rim calcification (ACR- TIRADS-4, ATA-2015-Intermediate suspicion, K-TIRADS-4), which was proved by cytology to be a papillary carcinoma

Table 4 indicates the association between the sonographic features of the thyroid nodules and the risk of malignancy. Significant direct associations were observed between malignancy and hypoechogenicity (OR = 5.78, 95% CI 3.34–10.03), fine calcification (OR = 6.7, 95% CI 4.01–11.24), rim calcification (OR = 2.56, 95% CI 1.13–5.73), ill-defined margin (OR = 3.31, 95% CI 2.01–5.46), and irregular margin (OR = 6.95, 95 CI 2.66–18.12).

Table 4.

Association between sonographic features and cytology results of the thyroid nodules

| Sonographic features | Benign nodules (n, [%]) | Malignant nodules (n, [%]) | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodule size (cm) | ||||

| < 2 | 500 (83.8) | 97 (16.2) | 1 | |

| ≥ 2 | 340 (87.9) | 47 (12.1) | 0.92 (0.60–1.43) | 0.712 |

| Echogenicity | ||||

| Hyperechogenicity | 534 (95.4) | 26 (4.6) | 1 | |

| Isoechogenicity | 161 (86.6) | 25 (13.4) | 1.49 (0.75–2.94) | 0.244 |

| Hypoechogenicity | 145 (60.9) | 93 (39.1) | 5.78 (3.34–10.03) | < 0.001 |

| Calcification | ||||

| Negative | 637 (93.7) | 43 (6.3) | 1 | |

| Fine calcification | 87 (52.4) | 79 (47.6) | 6.71 (4.01–11.24) | < 0.001 |

| Coarse calcification | 56 (91.8) | 5 (8.2) | 1.01 (0.34–2.93) | 0.982 |

| Fine + coarse calcification | 12 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) | 2.78 (0.81–9.53) | 0.104 |

| Rim calcification | 48 (81.4) | 11 (18.6) | 2.56 (1.13–5.73) | 0.023 |

| Margin of nodule | ||||

| Regular | 739 (91.2) | 71 (8.8) | 1 | |

| Ill-defined | 90 (62.5) | 54 (37.5) | 3.31 (2.01–5.46) | < 0.001 |

| Irregular | 11 (36.7) | 19 (63.3) | 6.95 (2.66–18.12) | < 0.001 |

| Composition | ||||

| Solid-cyst | 112 (94.9) | 6 (5.1) | 1 | |

| Solid | 728 (84.1) | 138 (15.9) | 1.12 (0.44–2.82) | 0.808 |

| Taller-than-wide shape | ||||

| Negative | 818 (87.8) | 114 (12.2) | 1 | |

| Positive | 22 (42.3) | 30 (57.7) | 0.81 (0.38–1.69) | 0.578 |

Discussion

In the present study, we compared the performance values of ACR-TIRADS, K-TIRADS, and ATA-2015 guidelines in distinguishing between benign and malignant thyroid nodules. We initially observed that the prevalence rate of malignancy increased with increasing risk categories of the three guidelines. Then, we tried to calculate the diagnostic accuracy for cut-off values of 4 and 5 separately for each guideline. For category 5, the values of specificity and NPV were higher than sensitivity and PPV, respectively, for all three systems; however, the accuracy of these guidelines was acceptable (nearly 90%). When the analyses were done for category 4 or 5, sensitivities and NPVs relatively increased in comparison to category 5; conversely, specificities, PPVs, and accuracies decreased.

A recent meta-analysis by Yang et al. [9] reported that the pooled estimate of sensitivity for the ATA guideline was 94%, which was slightly higher than that for ACR-TIRADS (85%) and K-TIRADS (85%). On the other hand, the pooled specificity estimate for ACR-TIRADS (68%) was higher than that for ATA (44%) and K-TIRADS (47%). The other recent meta-analysis by Kim et al. [12] showed that the sensitivity of ACR-TIRADS and K-TIRADS was 70% and 64%, respectively, for TIRADS category 5, which was higher than the values found in the present study. On the other hand, K-TIRADS had the highest pooled specificity (93%) for category 5, followed by ACR-TIRADS (89%), which was almost similar to the current survey. For TIRADS category 4 or 5, Kim et al. [12] reported that both ACR-TIRADS and K-TIRADS showed sensitivities higher than 90%, which was higher than our findings. Concerning specificity, K-TIRADS had a higher estimate than ACR-TIRADS (61% versus 49%), which was not in agreement with our results.

The differences in the diagnostic performance of the various ultrasound classification systems firstly result from the differences in their approach and scoring strategies regarding the nodules’ ultrasonographic features. Actually, ACR-TIRADS gives scores for thyroid nodules based on the malignant potential of all sonographic characteristics that can be helpful to assess nodules objectively, while ATA and K-TIRADS are pattern-based systems and use pre-defined ultrasonographic features to stratify nodules that seem to be more feasible for clinical application. Overall, these systems have their own advantages and disadvantages.

Over the past decade, some studies have alluded to the benefits of ultrasound elastography in the risk stratification of thyroid nodules. In other words, it has been reported that ultrasound elastography could be used as part of thyroid nodule characterization, and its combination with TIRADS can improve the diagnostic performance of this system [13–16]. However, further multicentre studies on this subject are warranted.

Another subject with which the ultrasound-based risk stratification systems are compared is the number of unnecessary FNA biopsies of thyroid nodules. According to the literature, ACR-TIRADS reduces unnecessary FNAs by 19.9–46.5% compared with other systems [17]. Our results showed that the rate of unnecessary FNA biopsies was 32% for ACR-TIRADS, which was lower than that for K-TIRADS and ATA-2015 guidelines (about 54%), indicating the superiority of ACR-TIRADS over other in this regard. In agreement with these findings, Xu et al. [18] reported that the rate of unnecessary FNAs in ACR-TIRADS was lower than K-TIRADS (17.3% versus 32.1%). Despite these results, the information on this point is limited and more studies are needed to evaluate the rate of unnecessary FNA biopsies in different systems.

In addition to how to classify the thyroid nodules mentioned above, these systems propose different size thresholds for FNA of suspected nodules. For category 5, ACR-TIRADS, K-TIRADS, and ATA-2015 recommend aspiration biopsy when nodules are ≥ 1 cm in size. However, the size criteria differ between the guidelines for category 4. K-TIRADS and ATA-2015 recommend FNA for nodules that are ≥ 1 cm in size, while this threshold in ACR-TIRADS is 1.5 cm. Despite the fact that these cut-offs have been suggested to avoid unnecessary FNAs, we should also consider the number of malignant nodules that can be potentially missed without FNA. For example, in the present study, we found that 28 of 50 malignant nodules in ACR-TIRADS-4 had a size between 1 and 1.5 cm (results not shown), meaning that about 56% of the malignant nodules could be potentially missed without a biopsy according to TR4. Although the overall rate of missed malignancies among non-FNA biopsies for ACR-TIRADS was low in the present study, the probability of missing the cancers in TR4 seems to be considerable; therefore, more investigations are proposed to be done on the size thresholds to decrease the likelihood of missing malignancy, especially for ACR-TIRADS class TR4.

Our results demonstrated a direct association between risk of malignancy and sonographic characteristics of hypoechogenicity, fine calcification, rim calcification, ill-defined margin, and irregular margin. Each guideline has its own imaging approach to stratify the thyroid nodules. In ACR-TIRADS, sonographic features of solid composition, hypoechogenicity, taller-than-wide shape, lobulated or irregular margin, extra-thyroidal extension, and rim or fine calcification are considered highly suspicious for malignancy [5], which is somewhat similar to the ATA-2015 guideline [8], while K-TIRADS emphasizes nodule solidity and other ultrasonographic characteristics are evaluated beside nodule solidity [7]. Contrary to these guidelines, we did not find a significant association between taller-than-wide and cancer risk in the present study, which could be explained by the low number of included nodules with this feature.

A limitation of this study was the lack of histological results for the malignant nodules that underwent surgery. Also, we did not access the findings of repeated FNA on nodules with atypical diagnoses. Furthermore, the present survey was conducted in a single-centre environment. These limitations should be addressed in future studies.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that there are different strengths of ACR-TIRADS, K-TIRADS, and ATA-2015 guidelines in the prediction of malignant thyroid nodules, and clinicians and radiologists should consider these differences in the management of thyroid nodules. We suggest multicentre studies with a greater sample size to have more accurate results.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Vice Chancellor for the Research of Babol University of Medical Sciences for supporting this study. We are also thankful to Dr. Kourosh Movagharnejad and Dr. Majid Sharbatdaran for their help in cytological assessments.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kamran SC, Marqusee E, Kim MI, Frates MC, Ritner J, Peters H, Benson CB, Doubilet PM, Cibas ES, Barletta J. Thyroid nodule size and prediction of cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:564–570. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nabahati M, Moazezi Z, Fartookzadeh S, Mehraeen R, Ghaemian N, Sharbatdaran M. The comparison of accuracy of ultrasonographic features versus ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology in diagnosis of malignant thyroid nodules. J Ultrasound. 2019;22:315–321. doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00377-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang AL, Falciglia M, Yang H, Mark JR, Steward DL. Validation of American Thyroid Association ultrasound risk assessment of thyroid nodules selected for ultrasound fine-needle aspiration. Thyroid. 2017;27:1077–1082. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tessler FN, Middleton WD, Grant EG. Thyroid imaging reporting and data system (TI-RADS): a user’s guide. Radiology. 2018;287:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017171240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tessler FN, Middleton WD, Grant EG, Hoang JK, Berland LL, Teefey SA, Cronan JJ, Beland MD, Desser TS, Frates MC. ACR thyroid imaging, reporting and data system (TI-RADS): white paper of the ACR TI-RADS committee. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwak JY, Han KH, Yoon JH, Moon HJ, Son EJ, Park SH, Jung HK, Choi JS, Kim BM, Kim E-K. Thyroid imaging reporting and data system for US features of nodules: a step in establishing better stratification of cancer risk. Radiology. 2011;260:892–899. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin JH, Baek JH, Chung J, Ha EJ, Kim J-H, Lee YH, Lim HK, Moon W-J, Na DG, Park JS, Choi YJ, Hahn SY, Jeon SJ, Jung SL, Kim DW, Kim E-K, Kwak JY, Lee CY, Lee HJ, Lee JH, Lee JH, Lee KH, Park S-W, Sung JY, Korean Society of Thyroid R, Korean Society of R Ultrasonography diagnosis and imaging-based management of thyroid nodules: revised Korean society of thyroid radiology consensus statement and recommendations. Korean J Radiol. 2016;17:370–395. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2016.17.3.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, Schuff KG, Sherman SI, Sosa JA, Steward DL, Tuttle RM, Wartofsky L. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American thyroid association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26:1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang R, Zou X, Zeng H, Zhao Y, Ma X. Comparison of diagnostic performance of five different ultrasound TI-RADS classification guidelines for thyroid nodules. Front Oncol. 2020;10:598225. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.598225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossi ED, Pantanowitz L, Raffaelli M, Fadda G. Overview of the ultrasound classification systems in the field of thyroid cytology. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:3133. doi: 10.3390/cancers13133133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Middleton WD, Teefey SA, Reading CC, Langer JE, Beland MD, Szabunio MM, Desser TS. Multiinstitutional analysis of thyroid nodule risk stratification using the American College of Radiology Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208:1331–1341. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim DH, Chung SR, Choi SH, Kim KW. Accuracy of thyroid imaging reporting and data system category 4 or 5 for diagnosing malignancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:5611–5624. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06875-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantisani V, David E, Grazhdani H, Rubini A, Radzina M, Dietrich CF, Durante C, Lamartina L, Grani G, Valeria A. Prospective evaluation of semiquantitative strain ratio and quantitative 2D ultrasound shear wave elastography (SWE) in association with TIRADS classification for thyroid nodule characterization. Ultraschall Med. 2019;40:495–503. doi: 10.1055/a-0853-1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Săftoiu A, Gilja OH, Sidhu PS, Dietrich CF, Cantisani V, Amy D, Bachmann-Nielsen M, Bob F, Bojunga J, Brock M. The EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations for the clinical practice of elastography in non-hepatic applications: update 2018. Ultraschall Med. 2019;40:425–453. doi: 10.1055/a-0838-9937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celletti I, Fresilli D, De Vito C, Bononi M, Cardaccio S, Cozzolino A, Durante C, Grani G, Grimaldi G, Isidori AM. TIRADS, SRE and SWE in INDETERMINATE thyroid nodule characterization: Which has better diagnostic performance? Radiol Med. 2021;126:1189–1200. doi: 10.1007/s11547-021-01349-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grani G, Lamartina L, Ascoli V, Bosco D, Biffoni M, Giacomelli L, Maranghi M, Falcone R, Ramundo V, Cantisani V. Reducing the number of unnecessary thyroid biopsies while improving diagnostic accuracy: toward the “right” TIRADS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:95–102. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoang JK, Middleton WD, Tessler FN. Update on ACR TI-RADS: Successes, challenges, and future directions, from the AJR special series on radiology reporting and data systems. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:570–578. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu T, Wu Y, Wu R-X, Zhang Y-Z, Gu J-Y, Ye X-H, Tang W, Xu S-H, Liu C, Wu X-H. Validation and comparison of three newly-released Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data Systems for cancer risk determination. Endocrine. 2019;64:299–307. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1817-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]