Abstract

Introduction

The Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) published the Good Surgical Practice guidelines in 2008 and subsequently revised them in 2014. Essentially, they outline the basic standards that need to be met by all surgical operation notes. The objective of the present study was to retrospectively audit the orthopaedic operation notes from a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai (between October 2020 to March 2021) against the recommended RCS Good Surgical Practice guidelines published in 2014.

Method

In the present study a total of 153 orthopaedic operation notes of 200 patients were audited by a single reviewer. During the period between October 2020 and March 2021, the data collection took place. All notes were typed on the standard operative proforma available on the hospital patient management software (SAP).

Results

Overall, the mandated fields in the EMR had excellent documentation. Documentation was excellent for the date and time of surgery, name of the surgeon, the procedure performed (100%), operative diagnosis (99.35%), an extra procedure performed (100%), and details of antibiotic prophylaxis (99.35); Inadequate for details of incision (94.77%), details of operative findings (92.16%), details of prosthesis (97.37%), DVT prophylaxis (96.08%) and detailed post-operative instructions (93.46%) and poor for tourniquet time (41.83%;), estimated blood loss (59.48%), closure details (16.99%), documentation of complications or lack of (51.63%) and setting of surgery elective or emergency (0%).

Conclusion

Compliance for completion and documentation of operative procedures was high in some areas; improvement is needed in documenting tourniquet time, prosthesis and incision details, and the location of operative diagnosis and postoperative instructions. With wider adoption of electronic medical record systems, there is a scope of improving documentation by mandating certain fields.

Keywords: Audit, Notes, Operation, Orthopaedics, Documentation

Introduction

Written communication and methodological documentation plays a significant role in preventing all aspects of error with illegible handwriting and unclear instructions highlighted as common problems [1]. Human factors were identified as a major contributor to Patient Safety Incidents (PSIs) in a study conducted by National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA), the United Kingdom in 2019, and problems with inefficient communication, in particular, have been acknowledged [2]. It is therefore emphasized that improving the quality of communication among healthcare workers can help reduce PSIs.

An operation note is an essential element of written communication in patient management. They carry vital information and are important tools for auditing the standards of care as well as forming a body of evidence in medico-legal proceedings. Audits of operation note quality have previously identified a failure to meet the required standards [3–5]. Against this background, the Royal College of Surgeons, England (RCS) issued guidelines in 2014 on maintaining high-quality operative notes with the view that the surgeons must ‘Ensure all medical records are legible, complete and contemporaneous’ [6]. This was subsequently endorsed by the British Orthopaedic Association. Both the RCS and BOA (British Orthopaedic Association) guidance aimed to set out a number of criteria that ought to be met to constitute a safe and satisfactory operation note [7].

The aim of the study was to audit the quality of elective and trauma orthopaedic operation notes against the standards set by the RCS and BOA in a tertiary care set-up in Mumbai. We further expanded on the guidelines to include data points that are documented in our institution to assess compliance with these expanded- documentation data points (Table 1; 19–25).

Table 1.

Percentage of compliances followed

| Parameters | Yes | NA | No |

|---|---|---|---|

| Date and time | 100 | 0.00 | 0 |

| Elective/emergency procedure | 0 | 0.00 | 100 |

| Names of the operating surgeon and assistant | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Name of the theatre anaesthetist | 98.13 | 0.00 | 1.87 |

| Operative procedure carried out | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Incision | 94.77 | 0.00 | 5.23 |

| Operative diagnosis | 99.35 | 0.00 | 0.65 |

| Operative findings | 92.16 | 0.00 | 7.84 |

| Any problems/complications (mentioned) | 51.63 | 0.00 | 48.37 |

| Any extra procedure performed and the reason why it was performed | 4.58 | 95.42 | 0.00 |

| Details of tissue removed/ biopsy, added or altered (mentioned) | 23.53 | 62.75 | 13.73 |

| Identification of any prosthesis used, including the serial numbers of prostheses and other implanted materials | 90.85 | 6.54 | 2.61 |

| Details of closure technique | 14.38 | 2.61 | 83.01 |

| Anticipated/Estimated blood loss | 54.25 | 5.23 | 40.52 |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis (where applicable) | 96.73 | 2.61 | 0.65 |

| DVT prophylaxis (where applicable) | 85.62 | 10.46 | 3.92 |

| Detailed postoperative care instructions | 92.81 | 0.65 | 6.54 |

| Tourniquet time(documented) | 1.31 | 40.52 | 58.17 |

| Surgical team | 100 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Time out, consent checked | 100 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Time stamps – suture times, etc | 100 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Cautery site | 100 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Surgical count | 100 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Relatives informed about wheel out | 100 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Type of dressing and immobilization | 100 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Materials and Methods

Operative notes of 200 consecutive patients treated in the orthopaedic department of a tertiary care hospital (Sir H.N. Reliance Foundation Hospital, Mumbai) in Mumbai between October 2020 and March 2021 were assessed by a single reviewer to check for completeness (Table 1). Following a correction for duplicates entries arising due to a surgical grading system used in the hospital, 153 operative notes were screened to assess for the presence of vital information like date and time of surgery, name of the surgeon, name of the surgical procedure, operative diagnosis, incision details, closure details, tourniquet time, postoperative instructions, complications, prosthesis used, and serial numbers as per the aforementioned guidelines. The categorical data were analysed based on frequency and percentage. Fields 1–18 (Table 1) were the standards set out by the RCS as previously mentioned, whereas no.19 to 25 (Table 1) were additional safety and quality improvement data that was captured.

Results

There were 75(49.02%) trauma cases and 78 (50.98%) elective cases (Fig. 1). 60.13% of the operation notes were written by consultants, 23.53% by a post-qualification senior registrar (Clinical Associates), and 16.34% by an orthopaedic trainee. All the notes were documented electronically on patient management software (SAP Inc.) used across the hospital.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of trauma or elective procedure

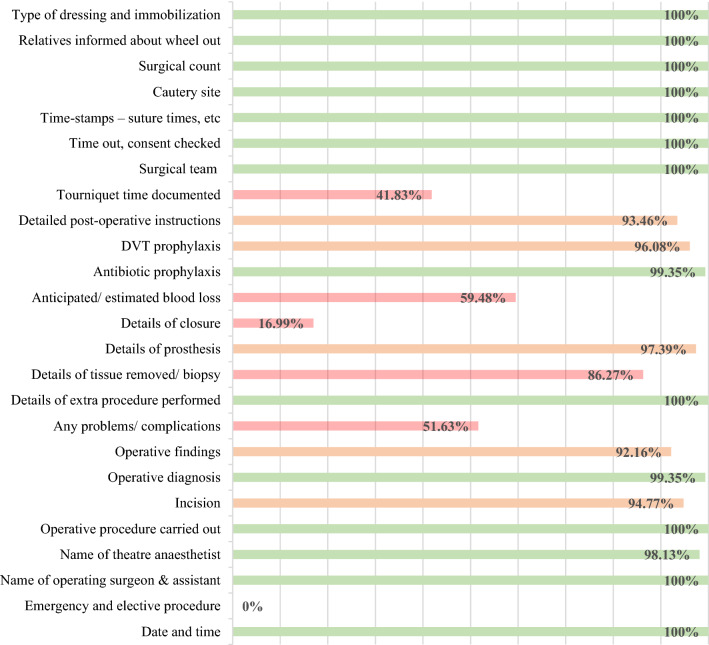

The outcomes were then stratified into groups based on compliance as follows, ‘green’ for percentage compliance of 98–100% ‘amber’ for 88–97%, and ‘red’ for compliance between 0 and 87%. The benchmark set was 100% for all criteria. However, we awarded a “green” for compliance above 98%, therefore, leaving some room for further improvement for a follow-up audit that we plan to undertake in due course. Amber criteria were inadequately documented and needed addressing. Red criteria were the ones well below accepted standards of practice and required urgent attention (Table 1).

Documentation was excellent for the date and Time of surgery (100%), name of the surgeon (100%), name of anaesthetist (98.13%), a procedure performed (100%), operative diagnosis (99.35%), an extra procedure performed (100%), and details of antibiotic prophylaxis (99.35%). Surgical team introduction, Time out and consent to check, Time-stamps (wheel in Time, wheel out Time, and suture time), Assessment of the cautery site, Surgical count—instrument, swabs and needles, Type of dressing and immobilization (100%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Study parameters categorised into red, amber and green based on the degree of compliance ‘green’ percentage completion of 98–100%, ‘amber’ 88–97%, ‘red’ 0–87%

Documentation was inadequate for details of incision (94.77%), details of operative findings (92.16%), details of prosthesis (97.37%), DVT prophylaxis (96.08%), and detailed post-operative instructions (93.46%). Documentation was poor for tourniquet time (41.83%;), estimated blood loss (59.48%), closure details (16.99%), documentation of complications or lack of (51.63%) and mention the setting—elective or emergency (0%).

Discussion

Illegible notes and missing information due to a failure of documentation are a major health care concern. In the previously published literature, they were as high as 20% [3, 8, 9]. Computerized notes avoid illegibility and help in medicolegal defence as well as in ensuring robust record keeping. We did not encounter this issue as all our operative notes were electronically documented, and an electronic proforma has ensured compliance of 99.38 to 100% for 14 out of the 25 parameters.

It has been previously argued that proforma operation notes are beneficial to many specialities. [3–5, 10] and the use of computer-generated templates or ready-made proforma together with typed notes have been found superior to handwritten notes [11]. Andrew et al. used electronic, custom-made operation notes for hip arthroplasty [12]. They demonstrated that it raised the general accuracy from 58 to 92% as well as improved documentation as per all the specific Royal College of Surgeons parameters and reduced variations seen with handwritten notes [13]. In our study, we have observed high compliance (green group) in parameters that were mandatory fields on the system.

We observed that certain areas needed improvement (red and amber groups). Poor documentation of tourniquet time may cause medicolegal problems in case of postoperative complications related to its use. Likewise, incomplete or ineligible postoperative instructions maybe put the patients at an increased risk of a Patient Safety Incident.

One probability for low compliance in this study is that the tourniquet time and blood loss were recorded by the anaesthetist and not surgeons. However, being an important operative consideration, it may be prudent for surgeons to record the same in their notes.

Likewise, details of prostheses were additionally captured by the nursing team for the hospital records. Additionally, a surgeon may not be recording negative factors; for example, if no complications occurred during the operation, they would not have stated ‘no complications’ in the note.

Nevertheless, we aim to improve on the findings and plan to introduce specificity to the template, like a drop-down menu and mandatory fields, which will be followed up by a close-the-loop audit to assess the effectiveness of our intervention. The RCS guidelines are comprehensive, but compliance with them continues to be an issue that is highlighted in this study. It may therefore be worthwhile to reconsider if each parameter still holds relevance in relation to a said speciality. In our opinion, some entries like details of closure are redundant in the orthopaedic context, whereas certain parameters which we feel are relevant, like position and use of technology like a robotic system, do not find a mentioned. We, therefore, feel that going forward the present guidelines warrant a re-look. Additionally, there were some data points captured by our system which may enhance patient safety like communication to the next of kin (NOK) regarding transfer out of the surgery. Although this may not be very relevant in certain healthcare systems due to a limited NOK involvement, it becomes significant in the Indian context where the family and friends are very actively involved in the treatment being administered to the patient and updating them of a change in the patient environment would enhance the patient experience and thereby play a role in reducing grievances.

The study was performed in a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai with state-of-the-art IT facilities and one that adopts an industry-wide best practice standard. Any deficiencies in such a setup can at best be seen as the tip of the iceberg, and the deficiencies might be much greater in a non-institutional setting as well as in other setups lacking the kind of IT facilities available at our institution. In such settings, especially in the lack of a proforma, the magnitude of these errors may be higher many folds. At present, there are no guidelines that set the standards for surgical operative notes in India. Additionally, electronic medical records systems are rapidly being adopted by hospitals all across the country. In such an early stage of adoption, there is a scope of framing these guidelines and building systems which can be customised (mandates, memory aids etc.) as well as be intuitive to enable easier adoption, encourage wide-spread use and bring about standardisation in operative record keeping. The World Health Organisation Surgical Safety Checklist was introduced in 2009 and has had a positive impact on patient safety with a reduction in overall complications including mortality and going forward, this could perhaps have a similar kind of impact [14, 15].

Conclusion

Completion and documentation of operative procedures were excellent in some areas; improvement is needed in documenting tourniquet time, prosthesis and incision details, and the location of operative diagnosis and postoperative instructions.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sanesh Tuteja, Email: sanesh.tuteja@outlook.com.

Anjali Tiwari, Email: anjalitiwari2988@gmail.com.

Jayesh Bhanushali, Email: bjayesh22@gmail.com.

Vaibhav Bagaria, Email: bagariavaibhav@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Organisation WH. (2008). Patient Safety Workshop LEARNING FROM ERROR.

- 2.Catchpole, K., Panesar, S., Russel, J., Tang, V., Hibbert, P., Cleary, K. (2009). Surgical safety can be improved through better understanding of incidents reported to a national database. Nat Patient Safety Agency

- 3.Payne K, Jones K, Dickenson A. Improving the standard of operative notes within an oral and maxillofacial surgery department, using an operative note proforma. Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery. 2011;10:203–208. doi: 10.1007/s12663-011-0231-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Hussainy H, Ali F, Jones S, McGregor-Riley J, Sukumar S. Improving the standard of operation notes in orthopaedic and trauma surgery: The value of a proforma. Injury. 2004;35:1102–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan D, Fisher N, Ahmad A, Alam F. Improving operation notes to meet British Orthopaedic Association guidelines. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2009;91:217. doi: 10.1308/003588409X359367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.RCSEng. (2014). Good Surgical Practice

- 7.BOA/BASK. (1999). Knee replacement: a guide to good practice

- 8.Sweed T, Bonajmah A, Mussa M. Audit of operation notes in an orthopaedic unit. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery. 2014;22:218–220. doi: 10.1177/230949901402200221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh A. An audit of orthopedic operation notes: What are we missing? Clinical Audit. 2010;2:37–40. doi: 10.2147/CA.S9665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bateman ND, Carney AS, Gibbin KP. An audit of the quality of operation notes in an otolaryngology unit. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. 1999;44:94–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baigrie RJ, Dowling BL, Birch D, Dehn TC. An audit of the quality of operation notes in two district general hospitals. Are we following Royal College guidelines? Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1994;76(1):8–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mustafa MKE, Khairy AMM, Ahmed ABE. Assessing the quality of orthopaedic operation notes in accordance with the royal college of surgeons guidelines: an audit cycle. Cureus. 2020;12(8):e9707. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barritt AW, Clark L, Cohen AM, Hosangadi-Jayedev N, Gibb PA. Improving the quality of procedure-specific operation reports in orthopaedic surgery. The Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2010;92:159–162. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12518836439245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(2008). WHO’s patient-safety checklist for surgery. Lancet. 372 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Fudickar A, Hörle K, Wiltfang J, Bein B. The effect of the WHO surgical safety checklist on complication rate and communication. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2012;109(42):695–701. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]