Abstract

Phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) are responsible for regulating biofilm formation, persister cell formation, pmtR expression, host cell lysis, and anti-bacterial effects. To determine the effect of psm deletion on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, we investigated psm deletion mutants including Δpsmα, Δpsmβ, and Δpsmαβ;. These mutants exhibited increased β-lactam antibiotic resistance to ampicillin and oxacillin that was shown to be caused by increased Nacetylmannosamine kinase (nanK) mRNA expression, which regulates persister cell formation, leading to changes in the pattern of phospholipid fatty acids resulting in increased anteiso-C15:0, and increased membrane hydrophobicity with the deletion of PSMs. When synthetic PSMs were applied to Δpsmα and Δpsmβ mutants, treatment of Δpsmα with PSMα1-4 and Δpsmβ with PSMβ1-2 restored the sensitivity to oxacillin and slightly reduced the biofilm formation. Addition of a single fragment showed that α1, α2, α3, and β2 had an inhibiting effect on biofilms in Δpsmα; however, β1 showed an enhancing effect on biofilms in Δpsmβ. This study demonstrates a possible reason for the increased antibiotic resistance in psm mutants and the effect of PSMs on biofilm formation.

Keywords: MRSA, phenol-soluble modulins, β-lactam antibiotic, biofilm, fatty acid, persister cell

Introduction

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains are regarded as major human pathogens [1]. These bacteria cause many diseases ranging from pneumonia to skin infections; most importantly, they have become resistant to antibiotics, resulting in problems during treatment [2]. MRSA are classified into two groups, i.e., healthcare-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) and community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA), depending on the infection site [3]. CA-MRSA are different from HA-MRSA in that they generally contain Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), which used to be the major relevant virulence factor of CA-MRSA skin and soft-tissue infections [4]. Furthermore, it has recently been determined that CA-MRSA express more phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs), and are therefore more virulent than HA-MRSA [5]. In other words, PSMs are significant major effectors of skin and soft-tissue infections, compared to PVL [6]. Along with PVL and alpha-hemolysin (Hla), PSMs are major virulence factors that are highly expressed in Staphylococci and CA-MRSA [7].

PSMs are a group of small, amphipathic peptides that have an α-helical structure, and there have been seven PSMs discovered, including PSM α1- α4, PSM β1-2, and PSMδ [8]. The general functions of PSMs include host cell lysis, biofilm formation, regulating persister cell formation, pmtR regulation and anti-bacterial effects [9]. psm genes are regulated by the agr system that positively regulates capsule formation, as well as extracellular protease and hemolysin production [10]. However, PSMs negatively regulate cell metabolism and the expression of biosynthetic genes [11]. To consolidate virulence in CA-MRSA, agr systems have been expressed to produce PSMs during the late exponential phase [12]. Recently, Δpsm mutants have produced thicker biofilms compared to those of the wild-type strain; it is unknown how PSMs influence physiological changes in MRSA [13].

In this study, the antibiotic resistance of the Δpsm mutants was compared to that of the LAC wild-type strain (USA300). Each PSM fragment and the whole peptide were supplemented to confirm the reversal of antibiotic susceptibility and elucidate the roles of each fragment. The expression profiles of N-acetylmannosamine kinase (nanK) and penicillin-binding protein 2a (encoded by mecA) were determined to investigate the regulatory function of PSMs related to antibiotic resistance. Membrane fatty acid profiling was performed to determine if the modified microenvironment was affecting the mechanism of antibiotic resistance. Additionally, membrane fluidity and cell surface hydrophobicity were compared to determine their relationship with antibiotic resistance.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Media, and Culture Conditions

For cell preparation, the wild-type strain S. aureus USA300 (LAC, ATCC BAA1756) [14] and the mutant strains Δpsmα, Δpsmβ, and Δpsmαβ [15] were cultured in tryptic soybean broth (TSB) agar and/or liquid broth. For pre-culture, a single colony of the strain from a TSB agar plate was used to inoculate 5 ml of TSB medium. Then, 1% (v/v) of the cell culture suspension was inoculated in a 96-well plate for the antibiotic resistance test, and cells were cultured overnight in a 37°C incubator without shaking, unless stated otherwise. PSMs were synthesized and prepared, as described previously [16].

Analysis of Cell Growth and Biofilm Formation

For analysis of cell and biofilm growth, a 96-well microplate reader was used to detect the optimal density at 595 nm (Tescan, Switzerland). Culture suspension (1%, v/v) from the pre-culture was inoculated into a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h without shaking. Biofilm formation was analyzed using crystal violet, in accordance with previous protocols [17]. Briefly, the supernatant was discarded, and the biofilm was fixed with methanol and air-dried. Then, the biofilm was stained with 200 μl 0.2% crystal violet for 5 min, after which, the crystal violet was discarded, the plate was washed with distilled water, and air-dried. Finally, the biofilm was analyzed at 595 nm using a 96-well microplate reader (Tescan).

Semi-Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Pre-culture was conducted using 5 ml of TSB, initiated using a single colony from an agar plate, in a shaking incubator at 37°C, overnight. Cells were cultured using 5 ml TSB with 1% inoculum in a shaking incubator at 37°C for 12 and 24 h to extract total RNA. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,521 ×g for 20 min. Then, total RNA was prepared using the TRIzol Reagent and reverse transcription was performed using Superscript IV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen Co., USA) to generate cDNA, as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers were designed using Primer express software v3.0.1 from Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA) (Table S1). These primers generated amplicons of 150 bp when comparing gene expression. Prior to semi-quantitative PCR, the cycle number was optimized to determine the saturated gene expression levels of DNA gyrase subunit B (gyrB, the endogenous control) for each template. After optimization, the optimal cycle number was set at 25 cycles to enable the further comparative analysis of gene expression. Semi-quantitative PCR was conducted using LA taq with GC buffer I (Takara Medical Co., Ltd.), using the methods in the manual.

Fatty Acid Analysis

Gas chromatography (GC)/mass spectrometry (MS) was used for the detection and quantification of fatty acids, in accordance with a previously described method, with a slight modification [18]. For methanolysis of fatty acids, approximately 10 mg of freeze-dried cells was weighed and placed in Teflon-stoppered glass vials. Then, 1 ml chloroform and 1 ml methanol/H2SO4 (85:15 v/v %) were added to the vials, after which they were incubated at 100°C for 2 h, cooled to room temperature, and then incubated on ice for 10 min. After adding 1 ml ice-cold water, the samples were thoroughly mixed by vortexing for 1 min, and then centrifuged at 3,521 ×g. The bottom organic phases were extracted using a pipette and moved to clean, borosilicate glass tubes, containing Na2SO4. GC/MS chromatography was performed using a Perkin Elmer Clarus 500 Gas Chromatograph that was connected to a Clarus 5Q8S Mass Spectrometer at 70 eV (m/z 50–550; source at 230°C and quadruple at 150°C) in the electrospray ionization mode with an Elite 5 ms capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. × 0.25 mm film thickness; PerkinElmer, USA). The carrier gas, helium, was used at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The inlet temperature was maintained at 300°C, and the oven temperature was programmed at an initial temperature of 150°C for 2 min before increasing to 300°C at a rate 4°C/min; the temperature was maintained for 20 min. The injection volume was 1 μl, with a split ratio of 50:1. The structural assignments were based on the interpretation of the mass spectrometric fragmentation and confirmed by comparison with the retention times and fragmentation patterns of the standards and spectral data that were obtained from the Wiley (http://www.palisade.com) and National Institute of Standards and Technology (http://www.nist.gov) online libraries. Methyl heneicosanoate (10 mg/ml; 10 μl) was used as an internal standard.

Membrane Fluidity and Cell Surface Hydrophobicity (CSH) Tests

Membrane fluidity was measured as a fluorescence polarization or anisotropy value. Harvested cells were treated as per the protocol described [19]. Briefly, the samples were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, pH = 7.0, resuspended, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min with 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH; Life Technologies, USA) at a concentration of 0.2 μM (0.2 mM stock solution in tetrahydrofuran). Fluorescence polarization values were determined using a SpectraMax 2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices; 360/40 nm excitation and 460/40 nm emission) using sterile black-bottom Nunclon delta surface 96-well plates. The excitation polarized filter was set in the vertical position. The emission polarized filter was set either in the vertical (IVV) or horizontal (IVH) position. The polarization value was calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

where G is the grating factor, assumed to be 1.

Cell surface hydrophobicity was estimated using the following method [20]. Cells grown in TSB medium were harvested by centrifugation (3,521 ×g, 20 min, 4°C) at the stationary phase of growth. The cells were suspended in cold phosphate buffer to an optical density at 595 nm (OD595) of 0.6. Aliquots of the suspension (3 ml) were transferred to two glass tubes. n-Octane (0.6 ml) was added to one tube (sample), but not to the other (control). Both suspensions were agitated vigorously for 2 min and then allowed to stand for 15 min to allow for separation into n-octane and saline layers.

Results and Discussion

Increased Resistance of psm Mutants to β-Lactam Antibiotics

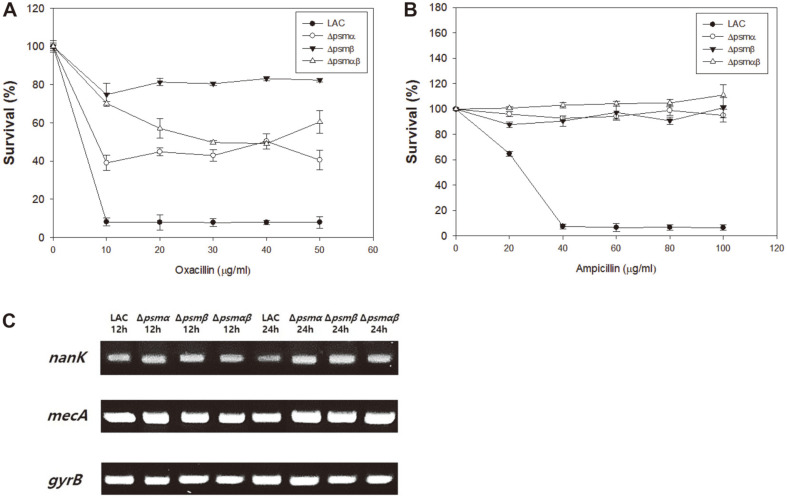

PSMs are related to biofilm structure and dispersion in that they support the biofilm structure by generating an amyloid structure and are capable of disseminating the biofilm by virtue of their surfactant properties [21]. psm null mutants lose their surfactant ability and are therefore unable to disperse biofilms; this results in biofilm thickening, which might eventually culminate in increased antibiotic resistance [18]. Therefore, the antibiotic resistance of Δpsm mutants was compared to that of the wild-type MRSA LAC strain to determine how psm deletions would affect the antibiotic sensitivity. The wild-type MRSA strain also showed oxacillin and ampicillin resistance; however, the growth of wild type was inhibited in response to increased concentrations of oxacillin and ampicillin ( > 40 μg/ml) (Figs. 1A and 1B). In contrast, Δpsm mutant strains were able to grow, even in the presence of 50 μg/ml oxacillin and 100 μg/ml ampicillin; their growth was not inhibited with further increases in antibiotic concentration. To determine the minimum inhibitory concentration of oxacillin, the mutant strains were treated with increasing concentrations of oxacillin (Fig. S1). As Δpsm mutants showed a thicker biofilm compared to the wild-type LAC strain, leading to blockage of antibiotic access and generation of persister cells, which is relevant to nanK expression [15, 22], other reasons for increased resistance were examined.

Fig. 1. Investigation of antibiotic resistance in Δpsm mutants.

(A) Identification of oxacillin resistance of Δpsm mutants. (B) Identification of ampicillin resistance of Δpsm mutants. (C) Semi-quantitative PCR of nanK and mecA. gyrB is used as an endogenous control. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three replicates.

As mecA is directly related to β-lactam antibiotic resistance, the expression of mecA in Δpsm mutants was investigated. The expression of nanK, which regulates the persister cell formation mentioned above, was also investigated (Fig. 1C). Mutations of psmα, psmβ and psmαβ resulted in increased nanK expression, suggesting that all Δpsm mutants expressed more nanK than the wild-type strain and formed more persister cells. When the expression of mecA was compared, the difference between strains was not dramatic, suggesting the production of PBP2a protein was not an issue in the resistance of psm mutants.

Analysis of Membrane Fatty Acid, Membrane Fluidity, and CSH of Δpsm Mutants

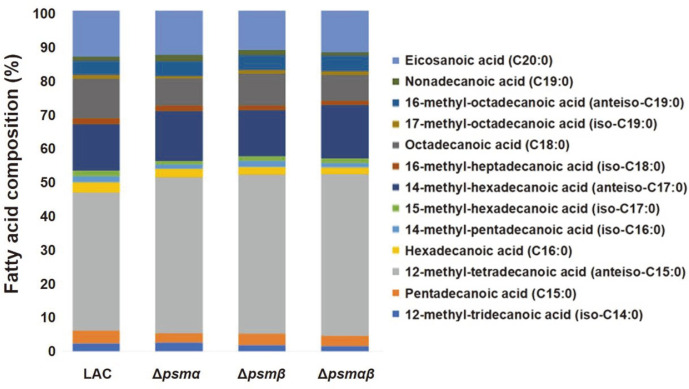

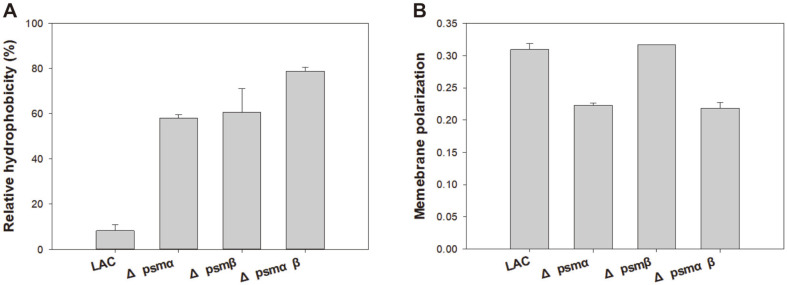

The complexity of antibiotic resistance mechanisms can be attested by the fact that various factors affect the physiological changes in MRSA resulting in increased antibiotic resistance. Biofilm formation, fatty acid synthesis, CSH, membrane fluidity, and membrane permeability are the major factors responsible for antibiotic resistance [23-26]. To check if a compositional change in fatty acids is responsible for the development of antibiotic resistance, membrane fatty acids are analyzed using GC-MS [18]. Additionally, CSH and membrane fluidity were investigated as CSH is known to be related to biofilms, which result in lower exposure to the surroundings and a less fluid membrane in some isolated MRSA strains that are known to have higher resistance. Phospholipid fatty acid analysis (PLFA) showed that all Δpsm mutants contained higher anteiso-C15:0 content compared to that of the wild-type strain, suggesting that the higher anteiso-C15:0 content was related to increased antibiotic resistance (Fig. 2). With respect to CSH, Δpsm mutants seemed to be more hydrophobic, which might have affected the increased antibiotic resistance (Fig. 3A). However, no correlation was observed between membrane fluidity and antibiotic resistance (Fig. 3B). Considering the roles of the membrane, changes in PLFA and hydrophobicity could be evidence of increased antibiotic resistance.

Fig. 2.

Membrane fatty acid profiles of the wild-type LAC strain and Δpsm mutants.

Fig. 3. Analysis of cell surface hydrophobicity and membrane fluidity of the wild-type LAC strain and the Δpsm mutants.

(A) Comparative analysis of cell surface hydrophobicity. (B) Comparative analysis of membrane fluidity. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three replicates.

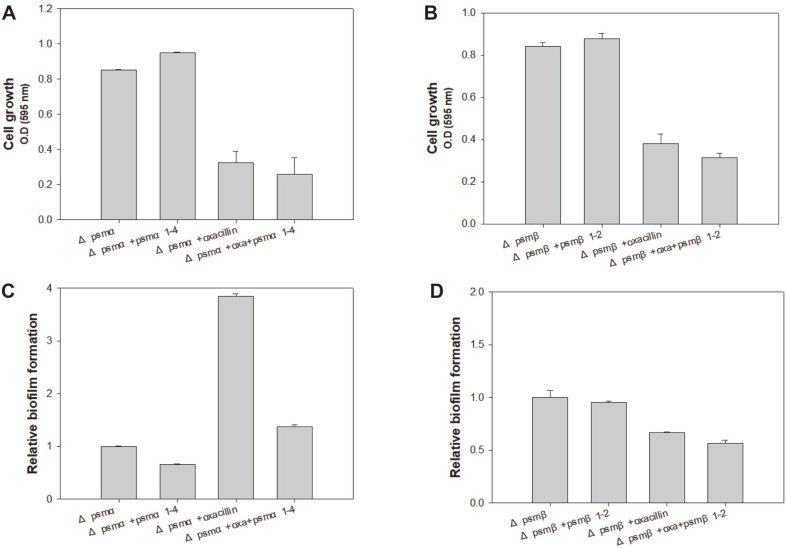

The Complex Effect of PSM Peptides on Antibiotic Susceptibility and Biofilm Formation

As the loss of PSM peptides in MRSA resulted in increased antibiotic resistance, it was expected that the exogenous supply of PSM peptides to psm deletion mutants could possibly revert the antibiotic sensitivity, similar to that observed in the wild-type LAC strain. PSMs are composed of several fragment units and previous studies have demonstrated that they tend to have common and dissimilar features [27, 28]. The Δpsm mutants were independently exposed to all fragments of PSMα1-4 and PSMβ1-2. The treatment of Δpsm mutants with PSM fragments and the complementation of each deletion mutant with the fragments resulted in slightly increased growth in the absence of oxacillin; however, complementation reversed loss of susceptibility to antibiotics leading to decreased growth compared to the Δpsm mutants without PSMs (Figs. 4A and 4B), although it did not fully reverse antibiotic susceptibility to the levels observed in the wild-type strain. Wild-type and Δpsm mutant USA300 exhibited different biofilm formation patterns. In case of Δpsmα, oxacillin greatly increased the biofilm formation, which was clearly decreased by PSMα1-4 (Fig. 4C). The results obtained in Δpsmβ were similar to those obtained in Δpsmα; however, the effect of PSMα1-4 was not as dramatic (Fig. 4D). Exogenous PSM supplementation revealed that PSMα1-4 decrease biofilms, while PSMβ1-2 have a mixed effect on biofilms, depending on the fragment.

Fig. 4. Reversed antibiotic susceptibility in Δpsm mutants with PSM peptide complementation.

(A, B) Growth comparison of the wild-type LAC strain and the Δpsm mutants with PSM peptide complementation. (C, D) Biofilm formation of the wild-type LAC strain and Δpsm mutants with PSM peptide complementation. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three replicates.

Effect of Each Peptide Fragment on Antibiotic Resistance and Biofilm Formation

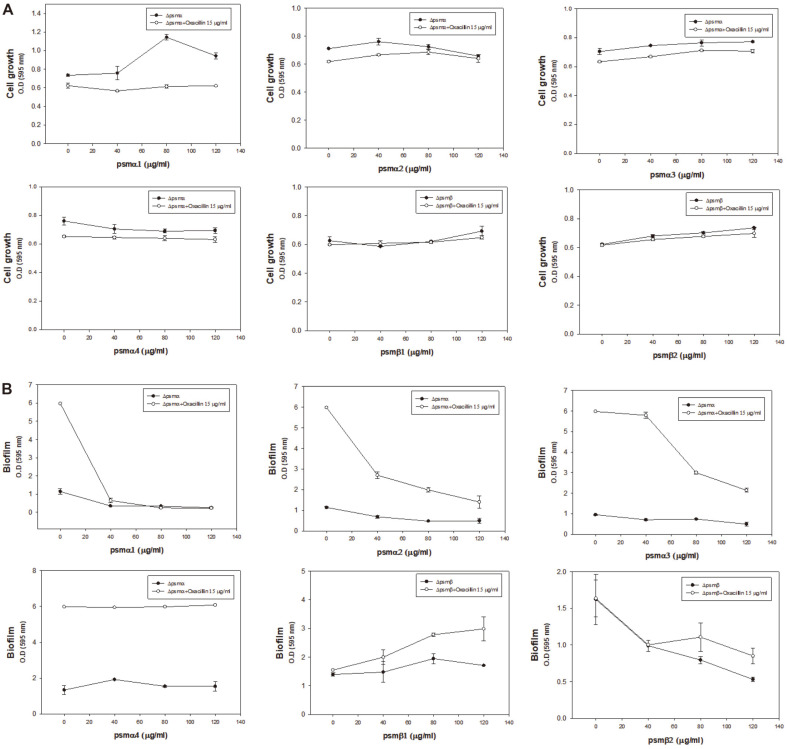

As PSMs are composed of several fragment units and they tend to have common and dissimilar features [27, 28], it was desirable to understand the effect of each PSM peptide. However, it is unknown which segment affects biofilm thickening and decreased antibiotic sensitivity. Therefore, six peptides from PSMα1- α4 and PSMβ1-2 were initially tested for complementation to determine if antibiotic resistance was reversed for Δpsmα and Δpsmβ, respectively. However, single fragment complementation did not result in reversed susceptibility to oxacillin in both Δpsm mutants (Fig. 5A). Biofilm formation decreased upon complementation with PSMα1, PSMα2, and PSMα3 in Δpsmα, though PSMα4 did not exhibit any effect (Fig. 5B). Additionally, PSMβ1 showed an increased effect on biofilm formation by Δpsmβ, but, PSMβ2 decreased biofilm formation by the Δpsmβ mutant. These data explain the decrease in biofilm formation by Δpsmα exposed to a mixture of PSMα1-4 in Fig. 4C, and the mixed results in Δpsmβ with PSMβ1-2 in Fig. 4D. Overall, among PSM peptides, PSMα1, PSMα2, PSMα3 and PSMβ2 decreased biofilm formation and PSMβ1 increased biofilm formation in a concentration-dependent manner. However, even with the decrease in the biofilm formation, the mutants did not show reversed susceptibility and remained antibiotic resistant.

Fig. 5. PSM fragment complementation into Δpsm mutants.

(A) Growth of Δpsm mutants with PSM fragment complementation. (B) Biofilm formation of Δpsm mutants with PSM fragment complementation. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three replicates.

Conclusion

PSMs are involved in host cell lysis, anti-bacterial effects, control of biofilm formation and persister cell formation and are produced more in CA-MRSA than in HA-MRSA [28]. Without PSM, MRSA lose their ability to release cytoplasmic proteins and lipids into the supernatant [18, 29]. In addition, psm mutants produce thicker biofilms compared to the wild type [15]. Although important microscopy-based results have been identified, many roles of PSMs in the pathophysiology of MRSA remain unknown. This might be because PSMs were regarded as an offensive weapon to the human host and the link between an offensive weapon and the internal antibiotic resistance of MRSA seemed to be very weak. However, considering the survival strategy of MRSA, the loss of an offensive strategy need not necessarily result in weakness in the context of infection. Although MRSA might lose some virulence due to the absence of PSMs, there are other benefits, such as saving energy to produce PSMs or modifying their membrane structure. In addition, all MRSA strains have fewer PSMs than methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA), suggesting the complex role of PSMs in the context of virulence to the host and antibiotic resistance [30]. Thus, these findings describing the link between PSMs and oxacillin resistance demonstrate the sensitizing role of PSMs in MRSA.

To determine this, Δpsm mutants have been used to examine resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, as the Δpsm mutant strain is able to produce thicker biofilms and form persister cells [13, 31]. However, even with the surfactant effect of the PSM fragment leading to elimination of biofilms, Δpsm mutants did not become susceptible to β-lactam antibiotics. Thus, a biofilm is not the only factor affecting the mechanism underlying antibiotic resistance. With the use of deletion mutants i.e., Δpsm, the expression of nanK and PLFA and hydrophobicity were changed. In addition to the fact that MRSA strains have lost their ability to release cytoplasmic proteins and lipids into the supernatant [29], a decrease in cell leakage and reduced fatty acids in the environment might facilitate membrane integrity followed by stable lipid raft formation, thereby increasing nanK expression to result in persister cell formation, leading to higher cell survival and cell wall hydrophobicity to help the cells attach more tightly to each other. This also may be a favorable situation for MRSA to oligomerize PBP2a into a functional conformation to increase antibiotic resistance [32]. Further investigation of fatty acids has shown that the anteiso-C15:0 proportion increased in the psm mutants. The increase in the acyl-chain length is responsible for the ordered state of the lipid bi-layer and aids the assembly of stable membrane microdomains, which further facilitate the oligomerization of PBP2a [18, 32]. In conclusion, PSMs clearly affect biofilm formation; however, they have more functions with respect to membrane composition and resistance-related genes that result in changes in the patterns of antibiotic resistance.

Supplemental Material

Supplementary data for this paper are available on-line only at http://jmb.or.kr.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research Program to Solve Social Issues of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2017M3A9E4077234) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (NRF-2019M3E6A1103979 and NRF-2019R1F1A1058805). In addition, this work was also supported by the Polar Academic Program (PAP, PE20900). This paper was supported by the Konkuk University Researcher Fund in 2020.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lakhundi S, Zhang KY. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: molecular characterization, evolution, and epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018;31:e00020–18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00020-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambers HF, Deleo FR. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:629–641. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang H, Flynn NM, Kim JH, Monchaud C, Morita M, Cohen SH. Comparisons of community-associated methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and hospital-associated MSRA infections in Sacramento, California. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:2423–2427. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00254-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatta DR, Cavaco LM, Nath G, Kumar K, Gaur A, Gokhale S, et al. Association of Panton Valentine Leukocidin (PVL) genes with methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Western Nepal: a matter of concern for community infections (a hospital based prospective study) BMC Infect. Dis. 2016;16:199. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1531-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaito C, Saito Y, Ikuo M, Omae Y, Mao H, Nagano G, et al. Mobile genetic element SCCmec-encoded psm-mec RNA suppresses translation of agrA and attenuates MRSA virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003269. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armbruster NS, Richardson JR, Schreiner J, Klenk J, Günter M, Kretschmer D, et al. PSM Peptides of Staphylococcus aureus Activate the p38-CREB Pathway in Dendritic Cells, Thereby Modulating Cytokine Production and T Cell Priming. J. Immunol. 2016;196:1284–1292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudkin JK, Laabei M, Edwards AM, Joo HS, Otto M, Lennon KL, et al. Oxacillin alters the toxin expression profile of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:1100–1107. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01618-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otto M. Phenol-soluble modulins. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014;304:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joo HS, Otto M. Toxin-mediated gene regulatory mechanism in Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Cell. 2016;4:29–31. doi: 10.15698/mic2017.01.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Queck SY, Jameson-Lee M, Villaruz AE, Bach THL, Khan BA, Sturdevant DE, et al. RNAIII-independent target gene control by the agr quorum-sensing system: insight into the evolution of virulence regulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quave CL, Horswill AR. Flipping the switch: tools for detecting small molecule inhibitors of staphylococcal virulence. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:706. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James EH, Edwards AM, Wigneshweraraj S. Transcriptional downregulation of agr expression in Staphylococcus aureus during growth in human serum can be overcome by constitutively active mutant forms of the sensor kinase AgrC. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013;349:153–162. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Periasamy S, Joo HS, Duong AC, Bach THL, Tan VY, Chatterjee SS, et al. How Staphylococcus aureus biofilms develop their characteristic structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:1281–1286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115006109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. CDC. Outbreaks of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections--Los Angeles County, California, 2002-2003. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2003;52:88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Periasamy S, Joo H-S, Duong AC, Bach T-HL, Tan VY, Chatterjee SS, et al. How Staphylococcus aureus biofilms develop their characteristic structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:1281–1286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115006109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joo HS, Otto M. The isolation and analysis of phenol-soluble modulins of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1106:93–100. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-736-5_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shukla S, Toleti SR. An improved crystal violet assay for biofilm quantification in 96-well microtitre plate. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1101/100214. doi.org/10.1101/100214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song H-S, Choi T-R, Han Y-H, Park Y-L, Park JY, Yang S-Y, et al. Increased resistance of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Δagr mutant with modified control in fatty acid metabolism. AMB Expxpress. 2020;10:64. doi: 10.1186/s13568-020-01000-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Royce LA, Liu P, Stebbins MJ, Hanson BC, Jarboe LR. The damaging effects of short chain fatty acids on Escherichia coli membranes. Appl.Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;97:8317–8327. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5113-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aono R, Kobayashi H. Cell surface properties of organic solvent-tolerant mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63:3637–3642. doi: 10.1128/AEM.63.9.3637-3642.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taglialegna A, Lasa I, Valle J. Amyloid Structures as Biofilm Matrix Scaffolds. J. Bacteriol. 2016;198:2579–2588. doi: 10.1128/JB.00122-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu T, Wang XY, Cui P, Zhang YM, Zhang WH, Zhang Y. The Agr quorum sensing system represses persister formation through regulation of phenol soluble modulins in Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:2189. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisignano C, Ginestra G, Smeriglio A, La Camera E, Crisafi G, Franchina FA, et al. Study of the lipid profile of ATCC and clinical strains of Staphylococcus aureus in relation to their antibiotic resistance. Molecules. 2019;24:1276. doi: 10.3390/molecules24071276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selvaraj A, Jayasree T, Valliammai A, Pandian SK. Myrtenol attenuates MRSA biofilm and virulence by suppressing sarA expression dynamism. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:2027. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bessa LJ, Ferreira M, Gameiro P. Evaluation of membrane fluidity of multidrug-resistant isolates of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus in presence and absence of antibiotics. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2018;181:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao L-Y, Liu H-X, Wang L, Xu Z-F, Tan H-B, Qiu S-X. Rhodomyrtosone B, a membrane-targeting anti-MRSA natural acylgphloroglucinol from Rhodomyrtus tomentosa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019;228:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.li L, Pian Y, Chen S, Hao H, Zheng Y, Zhu L, et al. Phenol-soluble modulin α4 mediates Staphylococcus aureus-associated vascular leakage by stimulating heparin-binding protein release from neutrophils. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29373. doi: 10.1038/srep29373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joo HS, Chatterjee SS, Villaruz AE, Dickey SW, Tan VY, Chen Y, et al. Mechanism of gene regulation by a Staphylococcus aureus toxin. mBio. 2016;7:e01579–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01579-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ebner P, Luqman A, Reichert S, Hauf K, Popella P, Forchhammer K, et al. Non-classical protein excretion is boosted by PSMα-induced cell leakage. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1278–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qi R, Joo H-S, Sharma-Kuinkel B, Berlon NR, Park L, Fu C-L, et al. Increased in vitro phenol-soluble modulin production is associated with soft tissue infection source in clinical isolates of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. 2016;72:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu T, Wang XY, Cui P, Zhang YM, Zhang WH, Zhang Y. The Agr Quorum sensing system represses persister formation through regulation of phenol soluble modulins in Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:2189. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Fernandez E, Koch G, Wagner RM, Fekete A, Stengel ST, Schneider J, et al. Membrane microdomain disassembly inhibits MRSA antibiotic resistance. Cell. 2017;171:1354–1367.: e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data for this paper are available on-line only at http://jmb.or.kr.