Abstract

Background: Pregnancy-induced Hypertension (PIH) is a disease that causes serious maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. Alisma Orientale (AO) has a long history of use as traditional Chinese medicine therapy for PIH. This study explores its potential mechanism and biosafety based on network pharmacology, network toxicology, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation.

Methods: Compounds of AO were screened in TCMSP, TCM-ID, TCM@Taiwan, BATMAN, TOXNET and CTD database; PharmMapper and SwissTargetPrediction, GeneCards, DisGeNET and OMIM databases were used to predict the targets of AO anti-PIH. The protein-protein interaction analysis and the KEGG/GO enrichment analysis were applied by STRING and Metascape databases, respectively. Then, we constructed the “herb-compound-target-pathway-disease” map in Cytoscape software to show the core regulatory network. Finally, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation were applied to analyze binding affinity and reliability. The same procedure was conducted for network toxicology to illustrate the mechanisms of AO hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity.

Results: 29 compounds with 78 potential targets associated with the therapeutic effect of AO on PIH, 10 compounds with 117 and 111 targets associated with AO induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity were obtained, respectively. The PPI network analysis showed that core therapeutic targets were IGF, MAPK1, AKT1 and EGFR, while PPARG and TNF were toxicity-related targets. Besides, GO/KEGG enrichment analysis showed that AO might modulate the PI3K-AKT and MAPK pathways in treating PIH and mainly interfere with the lipid and atherosclerosis pathways to induce liver and kidney injury. The “herb-compound-target-pathway-disease” network showed that triterpenoids were the main therapeutic compounds, such as Alisol B 23-Acetate and Alisol C, while emodin was the main toxic compounds. The results of molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation also showed good binding affinity between core compounds and targets.

Conclusion: This research illustrated the mechanism underlying the therapeutic effects of AO against PIH and AO induced hepato-nephrotoxicity. However, further experimental verification is warranted for optimal use of AO during clinical practice.

Keywords: pregnancy induced hypertension, Alisma orientale, network pharmacology, network toxicology, molecular docking

Introduction

Pregnancy-induced Hypertension (PIH) encompasses a series of serious pregnancy complications in the second trimester (after 20 weeks of gestation), including pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, chronic hypertension with pre-eclampsia and chronic hypertension with pregnancy (Chen et al., 2019). Little is currently known about the exact etiology, although it has been established that genetic, immunological and oxidative stress are risk factors (Magalhães et al., 2020). The pathological features include endothelial cell dysfunction, multiple cytokine stimulation and activation of the coagulation system with vasospasm and increased vascular reactivity, which lead to inadequate spiral arterioles and decreased invasion of trophoblasts into the maternal decidua of the uterus, leading to a series of clinical symptoms, such as generalized edema, vomiting, blurred vision, proteinuria and even disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (Chaiworapongsa et al., 2014). Furthermore, it causes fetal growth retardation, premature birth and perinatal stillborn fetus (Al Khalaf et al., 2022). Current evidence suggests that PIH is a significant threat to more than 70,000 gravidas and half a million fetuses worldwide yearly, with a high maternal mortality rate ranging from 10 to 16% (Bruno et al., 2022).

The complexity of the interactions also limits the efficacy of treatment. Currently available management consists of symptomatic treatment, including spasmolytics (magnesium sulfate), anticoagulants (aspirin), antihypertensive drugs, and termination of pregnancy as a last resort (Zhang et al., 2022a). Nevertheless, the clinical curative efficacy is highly heterogeneous and has been reported to cause maternal and fetal adverse effects (Ni et al., 2022).

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) therapy is an ancient practice used for more than 2000 years in China (Tian et al., 2021). The application of TCM therapy in modern society provides a novel approach for complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatment and is recognized by more and more people worldwide (Chu et al., 2022). Zhong-jing Zhang originally described PIH in “Synopsis in the Golden Chamber” as “nausea in pregnancy” “eclampsia” and “edema during pregnancy” (Xue et al., 2016). According to the syndrome differentiation theory, PIH is caused by Yin deficiency and Yang excess, deficiency of both spleen and kidney and blood stasis (Yeh et al., 2009). Over the years, many therapeutic methods and prescriptions of TCM have been used to treat PIH, and countless patients have benefited from it (Perry et al., 2018).

Alisma Orientale (AO), also called Ze Xie in Chinese, is a high-efficacy and low-toxicity herb medicine primarily used in Southeast Asian countries. Its efficacy is mainly mediated by removing dampness and promoting water metabolism (Wang et al., 2022), accounting for its efficacy in treating oliguria, edema and hypertension. “Women’s prescription” also recorded that AO could relieve systemic edema of gravida. In recent years, pharmacological research has demonstrated that AO compounds exhibit diuretic, anti-atherosclerotic and immunomodulatory activities, which all suitable for the treatment of PIH (Loh et al., 2017). Chen et al. reported that the natural compound of AO, alisol B 23-acetate, could inhibit Ang II-induced RAS/Wnt/β-catenin axis and attenuate podocyte injury (Chen et al., 2017). Moreover, it could inhibit collagen I, vimentin and α-smooth muscle actin at the mRNA and protein levels in rats (Chen et al., 2020). Notwithstanding that hundreds of active compounds have been isolated from AO, the specific compounds and correlative mechanisms have been largely understudied. Therefore, a novel method is urgently needed to reveal the complex treatment network and identify compounds underlying the therapeutic effect of AO against PIH. Besides, toxicology studies on AO have revealed that chronic administration may induce mild nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity (Yuen et al., 2006), emphasizing the need to verify the toxicity and safety profile of AO compounds and their molecular mechanisms.

The concept of network pharmacology was first officially reported by the British Pharmacologist Hopkins in 2007 (Hopkins, 2008), while network toxicology was originally proposed by Academician Liu of Chinese in 2011 (Li et al., 2019a). Both methods were based on the theories of “multi-target” and “multi-pathway” between the drug and disease, which are consistent with the characteristics of TCM therapy (Li et al., 2022).

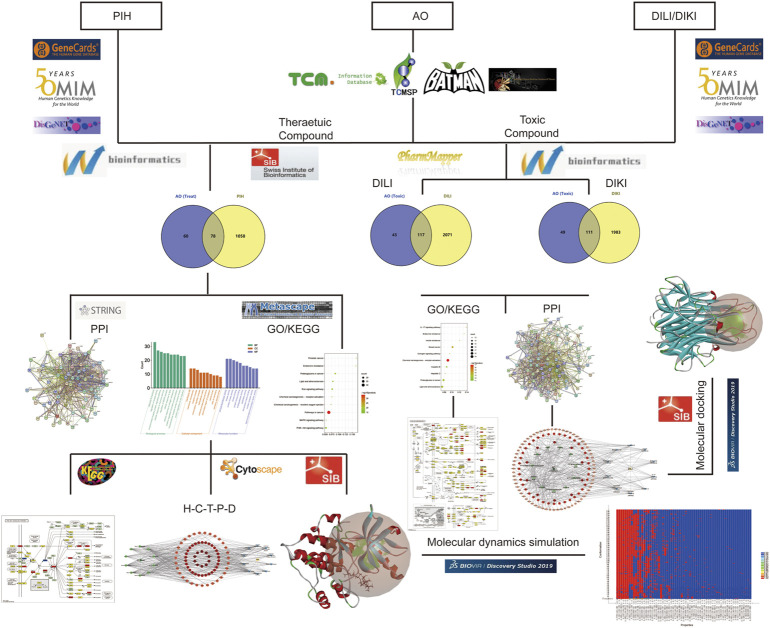

In this study, we applied network pharmacology to screen the main therapeutic compounds of AO and predicted the potential mechanism. In addition, we analyzed the potential hepato-nephrotoxicity mechanism of AO compounds by network toxicology during the treatment of PIH. Finally, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation analyses were used to estimate the binding stability. Overall, this study improves our current understanding of the potential pharmacodynamic and toxicity mechanism of AO in PIH patients and explores how to enhance efficacy and reduce toxicity. The detailed research content of this study is presented in the flow chart (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The flow chart of this study to explore the potential molecular mechanism of AO in the treatment of PIH and toxic compounds induced hepato-nephrotoxicity.

Methods

Obtaining therapeutic and toxicity-related compounds

The Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform (TCMSP http://lsp.nwu.edu.cn/tcmsp.php) database (Ru et al., 2014), Traditional Chinese Medicine Information Database (Kang et al., 2013) (TCM-ID http://bidd.group), BATMAN-TCM (Liu et al., 2016) (a bioinformatics analysis Tool for molecular mechanism of traditional Chinese medicine http://bionet.ncpsb.org.cn/) and TCM@Taiwa (Chen, 2011) (http://tcm.cmu.edu.tw/zh-tw/) database were used to acquire detailed information on identified AO compounds. Oral bioavailability (OB) refers to the dosage of drugs that enter the blood circulation through oral absorption and act on local tissues and organs to produce corresponding pharmacological effects. Drug-likeness (DL) is defined as the similarity of the chemical structure of a drug compared with known drugs. Both characteristics are important to assess the potential medicinal value of compounds (Dai et al., 2022). We selected the biologically active compounds of AO in the TCMSP database using the screening criteria: OB ≥ 30 and DL ≥ 0.18 (Gao et al., 2022). Similarly, compounds from other database sources were screened in SwissADME (Daina et al., 2017) (http://www.swissadme.ch) database according to their pharmacokinetic parameters. The toxicity compound of AO was further searched in Toxicology data network (TOXNET, http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/index.html) database (Fowler and Schnall, 2014) and Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD, https://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/ctd.htm) to analyze the biosafety profile of AO in the treatment of PIH (Stanic et al., 2021).

Potential targets related to AO compounds, PIH, liver and kidney injury

The structural formulas of therapeutic and toxic compounds obtained in the previous step were input into the PharmMapper (Liu et al., 2010) (http://www.lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/) and SwissTargetPrediction database (Daina et al., 2019) (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/) to predict the possible targets based on the spatial conformation. The uniport ID of the target was converted to the standardized gene name by Uniport (Holzhüter and Geertsma, 2022) (https://www.uniprot.org/) database. MeSH database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh) was utilized to verify the standard name of the disease as “Pregnancy-induced Hypertension” “drug-induced liver injury” (DILI) and “drug-induced kidney injury” (DIKI) (Zouhal et al., 2021). Then, GeneCards database (Barshir et al., 2021) (https://www.genecards.org/), DisGeNET database (Piñero et al., 2020) (https://www.disgenet.org) and Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (Li et al., 2012) (OMIM, https://omim.org) database were retrieved to obtain potential targets using the keywords “Pregnancy-induced Hypertension” “drug-induced liver injury” and “drug-induced kidney injury”. After merging and removing duplicate targets, the intersected targets in the Venn plot were defined as potential targets of OA compounds during PIH treatment and toxic compounds associated with hepato-nephrotoxicity.

Constructing PPI network to screen core target

A protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was generated to identify interacting proteins. STRING (Szklarczyk et al., 2021) (http://string-db.org, Version 11.5) database was used to construct a PPI network of the anti-PIH effect of AO, with species limited to “Homo sapiens” and interaction score >0.4. The Cytoscape plug-ins Cytohubba and MCODE (molecular complex detection) were used to analyze the topological parameters and select the core targets of AO anti-HIP with high accuracy and exhibit the complex relationship between disease and herb (Ye et al., 2022). The same steps were used to construct the PPI network of network toxicology.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

Functional enrichment analysis was conducted to better understand the functions of the screened genes. Gene Ontology (GO) enables the analysis of gene function based on the cellular compound (CC), molecular function (MF) and biological process (BP). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enables an understanding of the biological pathways associated with genes. Both were used to illustrate the core pathway and mechanism of AO anti-HIP. Targets were inputted in the Metascape database (Zhou et al., 2019) (http://www.metascape.org/), and the cut-off p-value, min overlap and enrichment value were set to 0.01, 3 and 1.5, respectively. And q-value < 0.05 (Benjamini–Hochberg method) was used to remove the false positive enrichment results (Zou et al., 2016). The R package available on the bioinformatics website (http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/) was used to visualize the enriched results as bar and bubble plots. Then, the KEGG (Kanehisa and Sato, 2020) (http://www.kegg.jp.org/) database was used to map and color the detailed target messages in the most significantly enriched pathway. Finally, the complex regulatory network of AO in the treatment of PIH was shown by the “herb-compound-target-pathway-disease” network, incorporating the elements of AO, therapeutic compound, potential target, and top 10 enriched pathway, and visualized by Cytoscape software (v.3.9.1, https://cytoscape.org/). The same steps were used to analyze the core pathways of toxic AO compounds associated with hepato-nephrotoxicity.

Molecular dock verified the binding affinity

The Swiss dock platform (Grosdidier et al., 2011) (http://www.swissdock.ch/) is an online molecular docking (MD) tool that enables the calculation of the binding affinity of each binding site between small molecule ligand and receptor protein. The X-ray diffraction of the protein crystal structure of core targets was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database (www.rcsb.org) (Nakamura et al., 2022). The results were ranked by the binding affinity score, and the lowest binding affinity score value corresponded to the best binding site. The binding affinity < -7 kcal/mol indicates a strong combination possibility, which was visualized in Discovery Studio 2019 software (https://www.3ds.com/) (Sultana et al., 2022).

Molecular dynamics simulation verified the binding stability

Molecular Dynamics simulations (MDS) were further conducted to investigate the stability of small molecule ligands in proteins by the “Standard Dynamics Cascade” unit of Discovery Studio2019 software for ligand-protein complexes with the lowest binding affinity after molecular docking (Hu et al., 2022). The ligand-protein complex was placed in a solvent chamber, filled with water molecules and stabilized the electrically neutral system with Cl− and Na+. After balancing the system by the NPT ensemble (fixed the pressure, temperature and number of particles), the simulation time value was set to 500 ps and heating, equilibrium and production phases were conducted. Finally, the result was derived by trajectories analyzed with Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) and hydrogen bond properties.

Result

Target prediction of AO compounds, PIH, liver and kidney injury

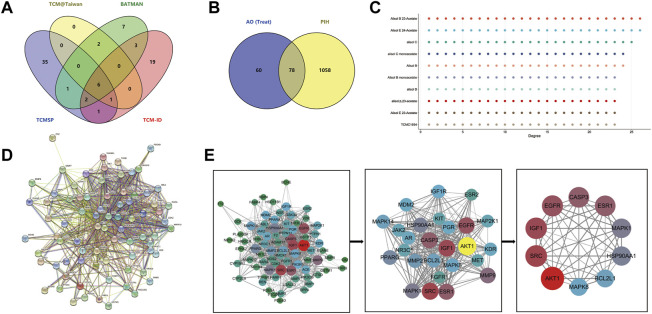

There were 77 compounds of AO obtained from TCMSP, TCM-ID, TCM@Taiwan and BATMAN database (Figure 3A) (Details were listed in Supplementary Table S1). Based on the screening criteria OB ≥ 30 and DL ≥ 0.18, 10 eligible active compounds were obtained from the TCMSP database, including sitosterol (MOL000359), Alisol B (MOL000830), Alisol B monoacetate (MOL000831), alisol b 23 acetate (MOL000832), 16β-methoxyalisol B monoacetate (MOL000849), alisol B (MOL000853), alisol C (MOL000854), alisol C monoacetate (MOL000856), 1-Monolinolein (MOL002464) and Alisol B acetate (MOL000862). There were 19 bioactive compounds from other database sources, including 13Β,17Β-Epoxyalisol A, 24-Deacetylalisol O, 25-Anhydroalisol F, Alismol, Alisol B 23-Acetate, Alisol E 23-Acetate, Alisol E 24-Acetate, Alizexol A, Neoalisol, Oriediterpenol, Oriediterpenoside and other eight compounds without formally name. The 10 toxic compounds retrieved from TOXNET and CTD databases were choline (MOL000394), emodin (MOL000472), 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF, MOL000748), 1 h-indole-3-carboxylic acid (MOL000823), sucrose (MOL000842), nicotinamide (NCA, MOL000857), stearic acid (MOL000860), Healip (MOL000861), 2-Furaldehyde and 2-Furancarboxylic acid (details shown in Table1, chemistry structure shown in Figure 2).

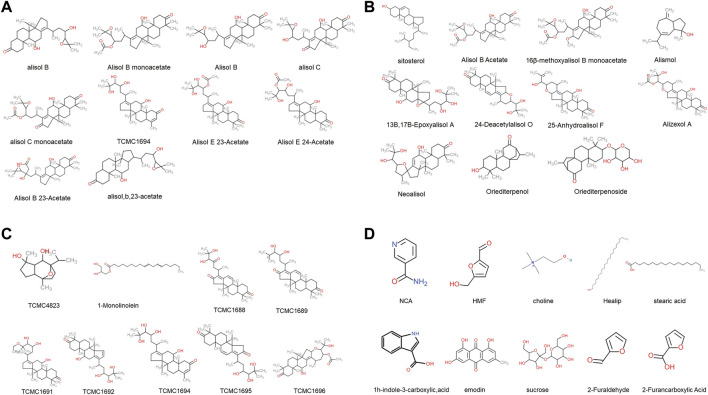

FIGURE 3.

The PPI network of AO active compounds in the treatment of PIH (A), Venn diagram of AO identified compounds from TCMSP, TCM-ID, TCM@Taiwan and BATMAN-TCM database (B), Venn diagram of potential targets to the AO treat PIH (C), The degree value of compound potential targets (D), The 78 targets PPI network gain from STRING database (E), Plug-in of Cytoscape to screen core targets.

TABLE 1.

The chemical characteristics of 39 AO bioactive compounds obtained in TCMSP, TCM-ID, TCM@Taiwan, and BATMAN-TCM database.

| No. | Molecule name | Molecular weight | InCHIKey ID | Compound | OB (%) | DL | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-Monolinolein | 354.59 | WECGLUPZRHILCT-GSNKCQISSA-N | Treat | 37.18 | 0.3 | TCMSP |

| 2 | Sitosterol | 414.79 | KZJWDPNRJALLNS-ZFVHJZABSA-N | Treat | 36.91 | 0.75 | TCMSP |

| 3 | Alisol B | 444.72 | XOWUWSRAQZUPJP-ASMOWKBLSA-N | Treat | 36.76 | 0.82 | TCMSP |

| 4 | Alisol B monoacetate | 514.82 | NLOAQXKIIGTTRE-JOGPTBIUSA-N | Treat | 35.58 | 0.81 | TCMSP |

| 5 | Alisol B Acetate | 514.82 | NLOAQXKIIGTTRE-JSWHPQHOSA-N | Treat | 35.58 | 0.81 | TCMSP |

| 6 | Alisol B | 472.78 | GBJKHDVRXAVITG-HKXAQQBESA-N | Treat | 34.47 | 0.82 | TCMSP |

| 7 | Alisol C monoacetate | 514.77 | KOOCQNIPRJEMDH-QSKXMHMESA-N | Treat | 33.06 | 0.83 | TCMSP |

| 8 | Alisol C | 486.76 | DORJGGFFCMZTHW-KXVAGGRESA-N | Treat | 32.7 | 0.82 | TCMSP |

| 9 | Alisol,b,23-acetate | 446.74 | QIMPSOXWCKBEBD-PQZUBQKGSA-N | Treat | 32.52 | 0.82 | TCMSP |

| 10 | 16β-methoxyalisol B monoacetate | 544.85 | UJRPGLKPBYUOLM-XBKPOWCMSA-N | Treat | 32.43 | 0.77 | TCMSP |

| 11 | NCA | 122.14 | DFPAKSUCGFBDDF-UHFFFAOYSA-N | Toxic | 71.13 | 0.02 | TCMSP |

| 12 | HMF | 126.12 | NOEGNKMFWQHSLB-UHFFFAOYSA-N | Toxic | 45.07 | 0.02 | TCMSP |

| 13 | Choline | 104.2 | GDPPXFUBIJJIKR-UHFFFAOYSA-N | Toxic | 0.47 | 0.01 | TCMSP |

| 14 | Healip | 326.68 | NOPFSRXAKWQILS-UHFFFAOYSA-N | Toxic | 11.65 | 0.22 | TCMSP |

| 15 | Emodin | 270.25 | RHMXXJGYXNZAPX-UHFFFAOYSA-N | Toxic | 24.4 | 0.24 | TCMSP |

| 16 | 1h-indole-3-carboxylic,acid | 161.17 | KUQQAVBKLJHQJI-UHFFFAOYSA-O | Toxic | 25.83 | 0.05 | TCMSP |

| 17 | Stearic acid | 284.54 | QIQXTHQIDYTFRH-UHFFFAOYSA-N | Toxic | 17.83 | 0.14 | TCMSP |

| 18 | Sucrose | 342.34 | CZMRCDWAGMRECN-UGDNZRGBSA-N | Toxic | 7.17 | 0.23 | TCMSP |

| NO. | Molecule name | Molecular weight | InCHIKey ID | Compound | GI absorption | Lipinski RO5 | Source |

| 19 | 13Β,17Β-Epoxyalisol A | 506.7 | BLYMKZZHAHHGBK-KOMKTNACSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 20 | 24-Deacetylalisol O | 470.34 | ZQFQEWOYCZTQFY-OZBSICFQSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 21 | 25-Anhydroalisol F | 470.34 | MRBFVJVQQIVGMY-CDJAXXMBSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 22 | Alismol | 220.35 | BUPJOLXWQXEJSQ-GIJJTGMTSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | BATMAN |

| 23 | Alisol B 23-Acetate | 516.35 | CPYFCYMXHGAZTF-WXYIYAPGSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 24 | Alisol E 23-Acetate | 532.8 | KRZLECBBHPYBFK-GLHMJAHESA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 25 | Alisol E 24-Acetate | 532.8 | WXHUQVMHWUQNTG-GLHMJAHESA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 26 | Alizexol A | 530.7 | KFWYQAKZMXFEFB-XKFNBYHKSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 27 | Neoalisol | 488.7 | QOEBTWRYOBEBPF-FZUOWIMQSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 28 | Oriediterpenol | 304.5 | ZALNTAHRBOFRCM-SVGWTELYSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | BATMAN |

| 29 | Oriediterpenoside | 436.6 | ITBIOEXYDKFWDZ-SUMMCVSUSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | BATMAN |

| 30 | TCMC1688 | 484.32 | GHJSMGTZWLBPHU-DSAUVPRUSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 31 | TCMC1689 | 468.32 | MPDDCFALNXXKHF-AJFHEMKZSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 32 | TCMC1691 | 518.4 | QVVRXENOONWNGX-IPAXGOGQSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 33 | TCMC1692 | 488.35 | OVJNKAWWCRMIMP-UNPOXIGHSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 34 | TCMC1694 | 474.33 | DCYOPZMJKBYLCO-QJDZRUNDSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 35 | TCMC1695 | 486.33 | PGQUPZCFLHXEHV-KPYCMCGFSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 36 | TCMC1696 | 530.36 | QJQGTCCCAJRIPR-QRPPABIJSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 37 | TCMC4823 | 254.36 | JNTOHIOAISZSEJ-SAAWNECCSA-N | Treat | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 38 | 2-Furaldehyde | 96.08 | HYBBIBNJHNGZAN-UHFFFAOYSA-N | Toxic | High | Yes | TCM-ID |

| 39 | 2-Furancarboxylic acid | 112.08 | SMNDYUVBFMFKNZ-UHFFFAOYSA-N | Toxic | High | Yes | TCM-ID/TCM@Taiwan |

OB, oral bioavailability; DL, drug-likeness; GI absorption, gastrointestinal absorption; HMF, 5-Hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde; NCA, nicotinamide; TCMC1688, (24R)-24,25-Dihydroxyprotosta-11,13(17)-Diene-3,16,23-Trione; TCMC1689, (23S,24R)-23,24-Dihydroxyprotosta-11,13(17),25-Triene-3,16-Dione; TCMC1691, (23S,24R)-11beta,23,24-Trihydroxy-25-Ethoxyprotosta-13(17)-Ene-3-One; TCMC1692, (23S,24R)-11beta,23,24,25-Tetrahydroxyprotosta-13(17),15-Diene-3-One; TCMC1694, (23S,24R)-11beta,23,24,25-Tetrahydroxy-29-Nor-3,4-Didehydroprotosta-13(17)-Ene-2-One; TCMC1695, (5R,8S,9S,10S,14R)-4,4,8,10,14-pentamethyl-17-[(2R,4S,5S)-4,5,6-trihydroxy-6-methylheptan-2-yl]-2,5,6,7,9,15-hexahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-3,16-dione; TCMC1696, [(1S,2R,4S,6S,7S,9R,13S,14S,15S,20R)-13-hydroxy-6-(2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)-1,2,9,15,19,19-hexamethyl-18-oxo-5-oxapentacyclo[12.8.0.02,11.04,10.015,20]docos-10-en-7-yl]; TCMC4823, (1S,2S,5R,6S,7R,8S)-1,5-dimethyl-8-propan-2-yl-11-oxatricyclo[6.2.1.02,6]undecane-5,7-diol.

FIGURE 2.

The chemical structure of 39 AO bioactive compounds obtained from TCMSP, TCM-ID, TCM@Taiwan and BATMAN-TCM database (A), The chemical structure of top 10 therapeutic compounds (B) and (C), The chemical structure of remaining 19 therapeutic compounds (D), The chemical structure of 10 toxic compounds.

After screening and removing duplicates, we identified 138 potential targets associated with 29 therapeutic compounds and 160 targets associated with 10 AO toxic compounds. Besides, 1136 putative targets of PIH, 2188 targets of drug-induced liver injury and 2094 targets of drug-induced kidney injury were retrieved from the GeneCards, DisGeNET and OMIM databases. 78 targets overlapped between therapeutic compounds of AO and PIH, while 117 and 111 targets overlapped between AO toxic compounds and liver and kidney injury were obtained by Venn (detailed targets provided in Table 2).

TABLE 2.

The detail gene name of potential targets of AO in the treatment of PIH and AO toxic compounds induced hepato-nephrotoxicity.

| No. | Target | Symbol | Entrez ID | Compound | NO. | Target | Symbol | Entrez ID | Compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Angiotensin-converting enzyme | ACE | P12821 | Treat/Toxic | 79 | Acetylcholinesterase | ACHE | P22303 | Toxic |

| 2 | Androgen receptor | AR | P10275 | Treat/Toxic | 80 | Long-chain-fatty-acid--CoA ligase 1 | ACSL1 | P33121 | Toxic |

| 3 | Cholinesterase | BCHE | P06276 | Treat/Toxic | 81 | Actin, aortic smooth muscle | ACTA2 | P62736 | Toxic |

| 4 | Carbonic anhydrase 2 | CA2 | P00918 | Treat/Toxic | 82 | All-trans-retinol dehydrogenase | ADH1B | P00325 | Toxic |

| 5 | Caspase-3 | CASP3 | P42574 | Treat/Toxic | 83 | Alcohol dehydrogenase 1C | ADH1C | P00326 | Toxic |

| 6 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 | CDK2 | P24941 | Treat/Toxic | 84 | Adenosylhomocysteinase | AHCY | P23526 | Toxic |

| 7 | Aromatase | CYP19A1 | P11511 | Treat/Toxic | 85 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B1 | AKR1B1 | P15121 | Toxic |

| 8 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 | DPP4 | P27487 | Treat/Toxic | 86 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | ALDH2 | P05091 | Toxic |

| 9 | Epidermal growth factor receptor | EGFR | P00533 | Treat/Toxic | 87 | Arginase-1 | ARG1 | P05089 | Toxic |

| 10 | Neutrophil elastase | ELANE | P08246 | Treat/Toxic | 88 | Beta-secretase 1 | BACE1 | P56817 | Toxic |

| 11 | Bifunctional epoxide hydrolase 2 | EPHX2 | P34913 | Treat/Toxic | 89 | Tyrosine-protein kinase BTK | BTK | Q06187 | Toxic |

| 12 | Estrogen receptor | ESR1 | P03372 | Treat/Toxic | 90 | Cyclin-A2 | CCNA2 | P20248 | Toxic |

| 13 | Estrogen receptor beta | ESR2 | Q92731 | Treat/Toxic | 91 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | CDK6 | Q00534 | Toxic |

| 14 | Coagulation factor X | F10 | P00742 | Treat/Toxic | 92 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 | CDKN1A | P38936 | Toxic |

| 15 | Prothrombin | F2 | P00734 | Treat/Toxic | 93 | Liver carboxylesterase 1 | CES1 | P23141 | Toxic |

| 16 | Fatty acid-binding protein, adipocyte | FABP4 | P15090 | Treat/Toxic | 94 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase Chk1 | CHEK1 | O14757 | Toxic |

| 17 | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta | GSK3B | P49841 | Treat/Toxic | 95 | Chitinase-3-like protein 1 | CHI3L1 | P36222 | Toxic |

| 18 | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase | HMGCR | P04035 | Treat/Toxic | 96 | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M1 | CHRM1 | P11229 | Toxic |

| 19 | 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 | HSD11B1 | P28845 | Treat/Toxic | 97 | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M2 | CHRM2 | P08172 | Toxic |

| 20 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha | HSP90AA1 | P07900 | Treat/Toxic | 98 | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M3 | CHRM3 | P20309 | Toxic |

| 21 | Tyrosine-protein kinase JAK2 | JAK2 | O60674 | Treat/Toxic | 99 | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain | COL1A1 | P02452 | Toxic |

| 22 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 | KDR | P35968 | Treat/Toxic | 100 | Collagen alpha-1(VII) chain | COL7A1 | Q02388 | Toxic |

| 23 | Mast/stem cell growth factor receptor Kit | KIT | P10721 | Treat/Toxic | 101 | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor | CSF2 | P04141 | Toxic |

| 24 | Galectin-3 | LGALS3 | P17931 | Treat/Toxic | 102 | Casein kinase II subunit alpha | CSNK2A1 | P68400 | Toxic |

| 25 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 | MAPK14 | Q16539 | Treat/Toxic | 103 | Cytochrome P450 1A1 | CYP1A1 | P04798 | Toxic |

| 26 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 | MAPK8 | P45983 | Treat/Toxic | 104 | Cytochrome P450 1A2 | CYP1A2 | O77810 | Toxic |

| 27 | Hepatocyte growth factor receptor | MET | P08581 | Treat/Toxic | 105 | Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (quinone) | DHODH | Q02127 | Toxic |

| 28 | Interstitial collagenase | MMP1 | P03956 | Treat/Toxic | 106 | Pro-epidermal growth factor | EGF | P01133 | Toxic |

| 29 | 72 kDa type IV collagenase | MMP2 | P08253 | Treat/Toxic | 107 | Coagulation factor VII | F7 | P08709 | Toxic |

| 30 | Stromelysin-1 | MMP3 | P08254 | Treat/Toxic | 108 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 | FLT1 | P17948 | Toxic |

| 31 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 | MMP9 | P14780 | Treat/Toxic | 109 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 | FLT4 | P35916 | Toxic |

| 32 | Oxysterols receptor LXR-beta | NR1H2 | P55055 | Treat/Toxic | 110 | Glutamate carboxypeptidase 2 | FOLH1 | Q04609 | Toxic |

| 33 | Bile acid receptor | NR1H4 | Q96RI1 | Treat/Toxic | 111 | Protein c-Fos | FOS | P01100 | Toxic |

| 34 | Glucocorticoid receptor | NR3C1 | P59667 | Treat/Toxic | 112 | Glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit 1 | G6PC1 | P35575 | Toxic |

| 35 | Mineralocorticoid receptor | NR3C2 | P08235 | Treat/Toxic | 113 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit alpha-1 | GABRA1 | P14867 | Toxic |

| 36 | Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 | PARP1 | P09874 | Treat/Toxic | 114 | Gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit alpha-2 | GABRA2 | P47869 | Toxic |

| 37 | Progesterone receptor | PGR | P06401 | Treat/Toxic | 115 | Glutamine synthetase | GLUL | P15104 | Toxic |

| 38 | Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit gamma isoform | PIK3CG | P48736 | Treat/Toxic | 116 | Glutamate receptor 2 | GRIA2 | P42262 | Toxic |

| 39 | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha | PPARA | Q07869 | Treat/Toxic | 117 | Glutathione reductase, mitochondrial | GSR | P00390 | Toxic |

| 40 | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma | PPARG | P37231 | Treat/Toxic | 118 | Histone deacetylase 8 | HDAC8 | Q9BY41 | Toxic |

| 41 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 1 | PTGS1 | P23219 | Treat/Toxic | 119 | Hexokinase-1 | HK1 | P19367 | Toxic |

| 42 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 1 | PTPN1 | P18031 | Treat/Toxic | 120 | Immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 1 | IGHG1 | P01857 | Toxic |

| 43 | Retinoic acid receptor alpha | RARA | P10276 | Treat/Toxic | 121 | Interleukin-1 beta | IL1B | P01584 | Toxic |

| 44 | Retinol-binding protein 4 | RBP4 | P02753 | Treat/Toxic | 122 | Interleukin-2 | IL2 | P60568 | Toxic |

| 45 | Sex hormone-binding globulin | SHBG | P04278 | Treat/Toxic | 123 | Integrin alpha-L | ITGAL | P20701 | Toxic |

| 46 | Vitamin D3 receptor | VDR | F8VRJ4 | Treat/Toxic | 124 | Kinesin-like protein KIF11 | KIF11 | P52732 | Toxic |

| 47 | Tyrosine-protein kinase ABL1 | ABL1 | P00519 | Treat | 125 | Tyrosine-protein kinase Lck | LCK | P06239 | Toxic |

| 48 | Disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 17 | ADAM17 | P78536 | Treat | 126 | Lysozyme C | LYZ | P61626 | Toxic |

| 49 | RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase | AKT1 | P31749 | Treat | 127 | Amine oxidase [flavin-containing] B | MAOB | P27338 | Toxic |

| 50 | Bcl-2-like protein 1 | BCL2L1 | Q07817 | Treat | 128 | Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | MIF | P14174 | Toxic |

| 51 | Cathepsin D | CTSD | P07339 | Treat | 129 | Macrophage metalloelastase | MMP12 | P39900 | Toxic |

| 52 | Cytochrome P450 2C9 | CYP2C9 | P11712 | Treat | 130 | Myc proto-oncogene protein | MYC | P01106 | Toxic |

| 53 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 | FGFR1 | P11362 | Treat | 131 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group I member 3 | NR1I3 | Q14994 | Toxic |

| 54 | Hexokinase-4 | GCK | P35557 | Treat | 132 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase pim-1 | PIM1 | P11309 | Toxic |

| 55 | Glutathione S-transferase Mu 1 | GSTM1 | P09488 | Treat | 133 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase PLK1 | PLK1 | P53350 | Toxic |

| 56 | Glutathione S-transferase P | GSTP1 | P09211 | Treat | 134 | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta | PPARD | Q03181 | Toxic |

| 57 | Heme oxygenase 1 | HMOX1 | P09601 | Treat | 135 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit alpha | PRKACA | P17612 | Toxic |

| 58 | Insulin-like growth factor I | IGF1 | P05019 | Treat | 136 | Protein kinase C delta type | PRKCD | Q05655 | Toxic |

| 59 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor | IGF1R | P08069 | Treat | 137 | Protein kinase C epsilon type | PRKCE | Q02156 | Toxic |

| 60 | Insulin receptor | INSR | P06213 | Treat | 138 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 | PTGS2 | P27607 | Toxic |

| 61 | Dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 | MAP2K1 | Q02750 | Treat | 139 | Glycogen phosphorylase, liver form | PYGL | P06737 | Toxic |

| 62 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | MAPK1 | P28482 | Treat | 140 | RAF proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase | RAF1 | P04049 | Toxic |

| 63 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 10 | MAPK10 | P53779 | Treat | 141 | Retinoic acid receptor beta | RARB | P10826 | Toxic |

| 64 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Mdm2 | MDM2 | Q00987 | Treat | 142 | Retinoic acid receptor RXR-alpha | RXRA | P19793 | Toxic |

| 65 | Neprilysin | MME | P08473 | Treat | 143 | Solute carrier family 2, facilitated glucose transporter member 1 | SLC2A1 | P11166 | Toxic |

| 66 | Matrilysin | MMP7 | P09237 | Treat | 144 | Solute carrier family 2, facilitated glucose transporter member 4 | SLC2A4 | P14672 | Toxic |

| 67 | Neutrophil collagenase | MMP8 | P22894 | Treat | 145 | Transcription factor Sp1 | SP1 | P08047 | Toxic |

| 68 | Nitric oxide synthase, inducible | NOS2 | P35228 | Treat | 146 | Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 | SREBF1 | P36956 | Toxic |

| 69 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group I member 2 | NR1I2 | O75469 | Treat | 147 | Tyrosine-protein kinase SYK | SYK | P43405 | Toxic |

| 70 | cAMP-specific 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase 4D | PDE4D | Q08499 | Treat | 148 | Transforming growth factor beta-1 proprotein | TGFB1 | P01137 | Toxic |

| 71 | cGMP-specific 3′,5′-cyclic phosphodiesterase | PDE5A | O76074 | Treat | 149 | Tumor necrosis factor | TNF | P01375 | Toxic |

| 72 | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulatory subunit alpha | PIK3R1 | P27986 | Treat | 150 | DNA topoisomerase 2-alpha | TOP2A | P11388 | Toxic |

| 73 | Phospholipase A2, membrane associated | PLA2G2A | P14555 | Treat | 151 | Cellular tumor antigen p53 | TP53 | P04637 | Toxic |

| 74 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11 | PTPN11 | Q90687 | Treat | 152 | Transthyretin | TTR | P02766 | Toxic |

| 75 | Renin | REN | P00797 | Treat | — | — | — | — | — |

| 76 | Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src | SRC | P12931 | Treat | — | — | — | — | — |

| 77 | TGF-beta receptor type-1 | TGFBR1 | P36897 | Treat | — | — | — | — | — |

| 78 | Thyroid hormone receptor beta | THRB | P10828 | Treat | — | — | — | — | — |

PPI network analysis

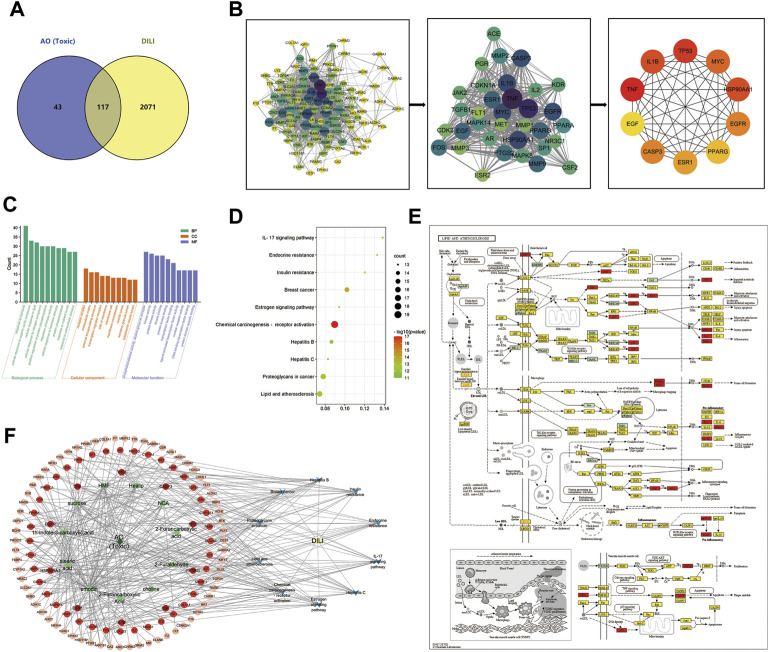

The 78 targets of AO in the treatment of PIH were incorporated into the STRING database to construct the PPI network. 78 nodes and 771 edges of protein-protein interaction were visually displayed in Cytoscape software, topological analysis including degree centrality (DC) and combined score, and the maximal clique centrality (MCC) algorithm was further used to screen the core targets. The top 10 targets were AKT1, BCL2L1, CASP3, EGFR, ESR1, HSP90AA1, IGF1, MAPK1, MAPK8 and SRC (Figure 3). Besides, after removing the disconnect node, the PPI network of toxic compounds-induced liver injury included 116 nodes and 1176 edges, the top 10 targets were CASP3, EGF, EGFR, ESR1, HSP90AA1, IL1B, MYC, PPARG, TNF and TP53 (Figures 5A,B). And the PPI network of toxic compounds-induced kidney injury included 109 nodes and 1130 edges, the top 10 targets were CASP3, EGF, EGFR, FOS, HSP90AA1, MMP9, MYC, PTGS2, TNF and TP53 (Supplementary Figure S1A,B).

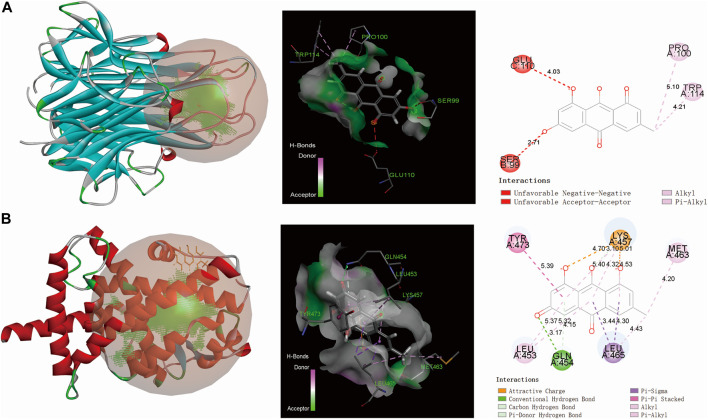

FIGURE 5.

The PPI network and GO/KEGG enrichment analysis of AO-induced liver injury (A), Venn diagram of potential targets to the AO-induced hepatotoxicity (B), The 116 targets PPI network and plug-in of Cytoscape to screen core targets (C), The bar graph of top 10 BP, CC and MF items (D), The bubble diagram of the top 10 KEGG pathway (E), The lipid and atherosclerosis pathway mapped by KEGG Mapper database (F), The H-C-T-P-D network showed the regulation mechanism of AO induced liver injury.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

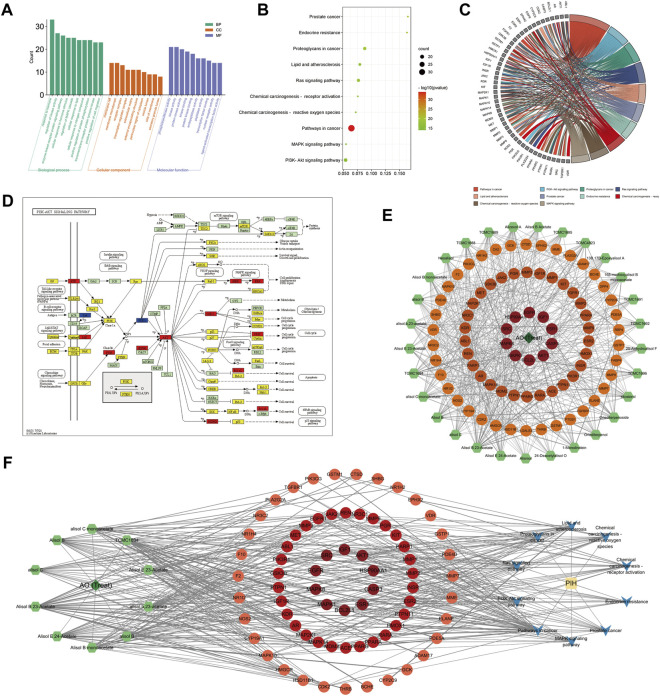

A total of 1022 biological process, 50 cellular compound and 93 molecular function items were obtained from the Metascape database, and 151 KEGG pathways were significantly enriched (p < 0.01, q < 0.05), demonstrating the characteristic of multi-pathway of AO in the treatment of PIH. The top 10 biological processes included the response to hormone, regulation of kinase activity, enzyme-linked receptor protein signaling pathway, cellular response to hormone stimulus, regulation of MAPK cascade cellular response to lipid, cellular response to nitrogen compound, positive regulation of protein phosphorylation, transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase and positive regulation of cell migration (Figures 4A–C).

FIGURE 4.

GO/KEGG enrichment analysis of AO treat PIH (A), The bar graph of top 10 GO items, including biological process (BP), cellular compound (CC) and molecular function (MF) (B), The bubble diagram of the top 10 KEGG pathway (C), GO chord chart (D), The core pathway, PI3K-AKT cascade mapped by KEGG Mapper database, whereby therapeutic targets were colored in red, targets of AO but not in the treatment of PIH were in blue, the other targets of PIH were yellow (E), The H-C-T network map showed the importance of each AO compounds, whereby 29 compounds ranked by degree value (F), The H-C-T-P-D network map showed the complex regulation of AO treat PIH. The deep green diamond represents herb (AO), the light green hexagon represents the therapeutic compound of AO, the red and orange circles represent targets based on the degree value, the blue V icon represents the pathway involved, and the yellow rectangle is the disease (PIH).

The top 10 significantly enriched KEGG pathways included Pathways in cancer, MAPK signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, Proteoglycans in cancer, Prostate cancer, Lipid and atherosclerosis, Ras signaling pathway, Endocrine resistance, Chemical carcinogenesis -receptor activation and reactive oxygen species. Based on the enrichment ratio of pathways and their correlation with diseases, the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway was the most important. We further colored the detailed targets of the PI3K-Akt pathway in the KEGG mapper database, whereby therapeutic targets were colored in red, targets of AO but not in the treatment of PIH were in blue, the other targets of PIH were yellow (Figure 4D). Besides, a total of 1262 biological process, 55 cellular compound and 117 molecular function and 168 KEGG pathway items were significantly enriched (p < 0.01, q < 0.05), and the lipid and atherosclerosis pathway was significantly associated with AO induced liver injury (Figures 5C–E). And a total of 1260BP, 52 CC, 115 MF items, and 161 KEGG pathway were enriched (p < 0.01, q < 0.05), the lipid and atherosclerosis pathway was also significantly associated with AO induced kidney injury (Supplementary Figures S1C,E).

Herb-compound-target-pathway-disease network analysis

After identifying the core targets and the top 10 pathways from previous analysis, a “herb-compound-target-pathway-disease” (H-C-T-P-D) network was constructed by Cytoscape 3.9.1 to reveal the complex molecular mechanism and multi-compound, multi-target and multi-pathway characteristic of AO in the treatment of PIH (Figures 4E,F). The major active compounds from the network were Alisol B 23-Acetate, Alisol E 24-Acetate and alisol C. The deep green diamond represents herb (AO), the light green hexagon represents the therapeutic compound of AO, the red and orange circles represent targets based on the degree value, the blue V icon represents the pathway involved, and the yellow rectangle is the disease (PIH). Similarly, the “H-C-T-P-D” network was used to illustrate the mechanism of AO toxic compounds induced liver injury (Figure 5F) and kidney injury (Supplementary Figure S1F), whereby the green diamond, the light green hexagon, the red circle, the blue Vicon and the yellow rectangle represent the herb, the toxic compounds of AO, targets, pathways, and disease (AO induced hepato-nephrotoxicity). The main toxic compound was emodin (MOL000472).

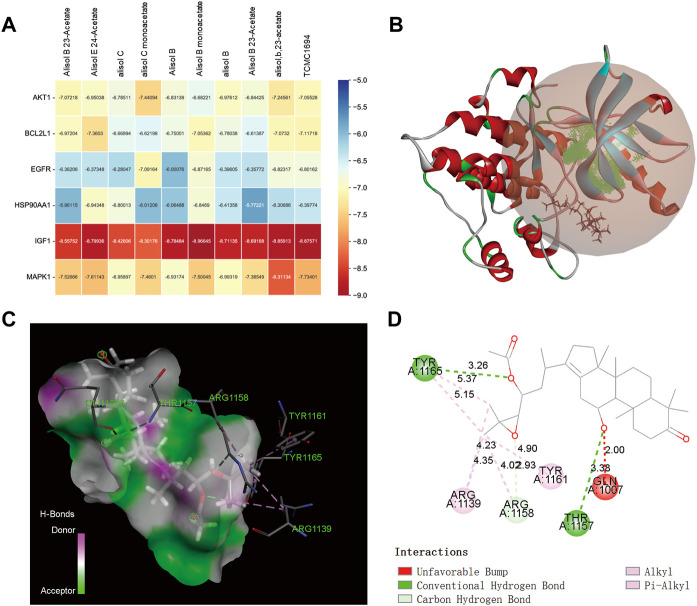

Molecular docking

Supplementary Table S2 exhibits the binding affinity of the top 10 therapeutic compounds and emodin with their core targets, respectively. The results showed that the active compounds had good binding activities with all targets. A binding affinity < -5.0 kcal/mol indicated that the small molecule ligand has a good binding activity with the receptor protein, and binding affinity < -7.0 kcal/mol indicated stronger binding activity. Among them, we found a binding affinity < -7.0 kcal/mol between all compounds and IGF1 as well as emodin with TNF and PPARG, indicating that IGF1 may be an important target mediating the therapeutic effect against PIH, and PPARG and TNF may be the main targets of AO-induced liver injury. Figure 6A was the binding affinity heatmap of ligand-protein complexes, and Figures 6B–D shows the details of molecular docking between Alisol B monoacetate and IGF1 (lowest binding affinity); the intermolecular forces include alkyl bonding, π-alkyl bonding, conventional hydrogen bonding and carbon-hydrogen bonding. Figure 7 shows the results of emodin binding with PPARG and TNF.

FIGURE 6.

The molecular docking results of AO therapeutic compounds with core targets (A), The binding affinity heatmap of ligand-receptor complex (B), 3D structures of the Alisol B monoacetate-IGF1 complex (C), spatial structure of Alisol B monoacetate-IGF1 show binding details (D), 2D structure of Alisol B monoacetate-IGF1 complex show intermolecular force types.

FIGURE 7.

The molecular docking results of AO toxic compounds with corresponding core targets (A), emodin docking with TNF (B), emodin docking with PPARG (From left to right: 3D, spatial and 2D structure).

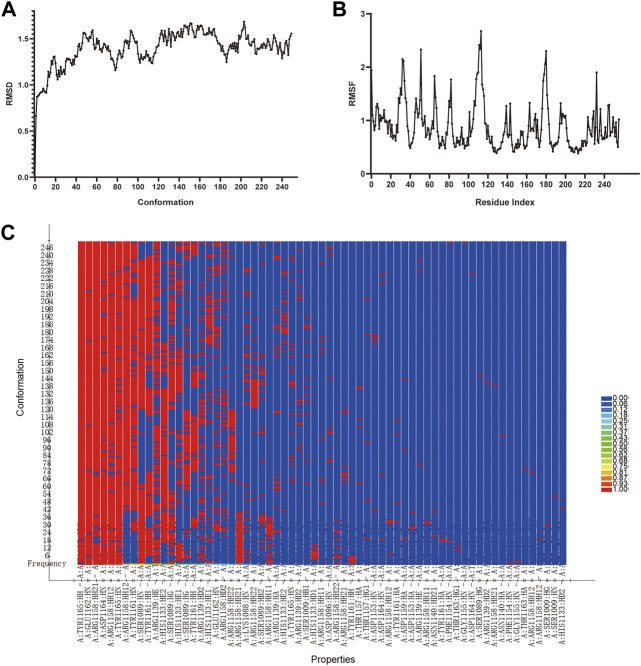

Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular dynamics simulation represents an important technology for analyzing the ligand-protein complex’s conformational change and stability after docking. To explore the binding stability of Alisol B monoacetate with IGF1, the RMSD, RMSF curves, energies alternate tendency and hydrogen bonding heat map were calculated. Figure 8 shows that after 50 ps, the trajectories of all molecules and energy levels tend to stabilized. The RMSD, RMSF curve and hydrogen bond heat map exhibited good stability.

FIGURE 8.

The molecular dynamic simulations results of Alisol B monoacetate binding with IGF1 (A), RMSD and (B), RMSF curves of MDS (C), Hydrogen bond heat map of Alisol B monoacetate binding with IGF1.

Discussion

Pregnancy-induced hypertension is a common disease during pregnancy, with a 10–12% incidence rate (Lan et al., 2022). Elevated arterial pressure and proteinuria are the most prominent clinical manifestations, and disease progression can cause reversible pathological damage to multiple systems and organs. Given the importance of the safety profile of drugs indicated for pregnant women and the unknown pathogenesis of PIH, significant emphasis has been placed on better understanding the underlying therapeutic and toxic mechanisms of these drugs (Reddy et al., 2022).

As mentioned above, oxidative stress, immune dysregulation, endothelial cell malfunction and other perplex factors have been associated with the pathogenesis of PIH. Unlike Western medicine which adopts a targeted approach, TCM fosters a more holistic approach based on the multi-compound, multi-target and multi-pathway of TCM drugs and has huge prospects for use as complementary and alternative medicine.

Alisma Orientale, also known as “Ze Xie” in Chinese, is the most important herbal compound in Ze Xie decoction indicated for treating hypertension, according to ancient records. Modern studies have isolated more than 100 active compounds, mainly terpenoids and small amounts of flavonoids, alkaloids, phytosterols and fatty acids. It is worth mentioning that protostane triterpenoids are the characteristic compounds, including alisol A-I and their derivatives (Shu et al., 2016). It has been established that Alisol B 23-acetate is an important compound with excellent bioactivities used to characterize AO in the “Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China” (Li et al., 2019b). Our findings showed that compounds with therapeutic effects included Alisol B 23-acetate, Alisol E 24-acetate and other derivatives, consistent with the “H-C-T-P-D” network.

Previous studies have demonstrated that AO plants, especially triterpene compounds, have diuretic activity. Zhang et al. reported that Alisol B, alisol B 23-acetate and other derivatives could interfere with the Na+, K+, and Cl− co-transport carrier on the luminal membrane of the Henle and sodium–chloride co-transporter in the renal distal convoluting tubule to exert diuretic action (Zhang et al., 2017). It could also significantly affect K+ excretion by competitively binding the receptor site in the collecting tube to influence sodium, potassium exchange and acid absorption. Besides, the immunomodulatory activity of the methanol extract of triterpenoids from the AO plant (alisol A, B and their acetate derivatives) significantly inhibited paw swelling in rats showing type I-IV hypersensitivity (Shao et al., 2018). In addition, alisol B and alisol B monoacetate could inhibit the complement system through the antigen–antibody-mediated process, exhibiting a good therapeutic effect against immune-related diseases (Lee et al., 2003). Further studies illustrated that alisol B 23-acetate could prevent lipid peroxidation and regulate inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression, with significant reticuloendothelial system-potentiating activities (Matsuda et al., 1999). In conclusion, the active compounds of AO possess diuretic, immunomodulatory and vascular endothelial modulatory activities, exhibiting multi-compound, multi-target and cooperation characteristics as well as multi-compound amplification effects in the treatment of PIH.

Few studies have hitherto assessed the toxicity and side effects of AO and its compounds to determine its biosafety profile (Tian et al., 2014). Accordingly, network toxicology was applied to explore the potential mechanism in this research. Our findings showed that emodin belonging to flavonoids was the main compound that induced hepato-nephrotoxicity, and other toxic compounds with smaller proportions, including fatty acids and carbohydrates, such as stearic acid and sucrose. PPI network and GO/KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that AO toxic compounds mainly targeted PPARG and TNF and regulated the lipid and atherosclerosis signaling pathway. PPARG, also known as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, is a nuclear receptor binding peroxisome proliferator that regulates adipocyte differentiation and controls the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway of fatty acids (Małodobra-Mazur et al., 2022). Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is mainly secreted by macrophages and can induce insulin resistance through inhibition of Insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1), tyrosine phosphorylation and G kinase-anchoring protein 1 (GKAP42) degradation in adipocytes (Ando et al., 2015). Taken together, we provide preliminary evidence that the potential mechanism in AO-induced liver injury may mediate lipid metabolism via network toxicology.

PPI network analysis showed that IGF, AKT1, EGFR and MAPK1 were the main targets of AO in the treatment of PIH; the molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation results also exhibited good binding affinity and stability. Besides, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that MAPK and PI3K-AKT signal pathways were significantly enriched. Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF1) can bind to the alpha subunit of IGF1 receptor and modulate the tyrosine kinase activity to initiate the down-stream signaling events activation of PI3K-AKT and Ras-MAPK pathways (Mohindra et al., 2022). It has been reported that IGF1 is differentially expressed between PIH and normal pregnancy newborns, and IGF1 could stimulate extra-villous trophoblast (EVT) cell migration and invasion, given that insufficient invasion into the uterine endometrium may be the crucial reason for PIH (Seedorf et al., 2020). Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase (AKT1) are important hub genes that regulate a series of biological functions, including angiogenesis (Zhang et al., 2022b). Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (MAPK1) has been associated with the transduction of endothelial inflammatory response and inflammatory factor expression action (Galganska et al., 2021). Wang Z et al. indicated that overexpressing miR-106 and downregulating the MAPK signaling cascade could attenuate oxidative stress injury and inflammatory response in the liver of mice with PIH (Wang et al., 2019). Li X et al. found significant Cx43 protein overexpression on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in PIH patients, which may lead to monocyte-endothelial adhesion increase by PI3K-AKT signaling pathway activation and upregulate the downstream genes of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 (Li et al., 2019c).

In conclusion, we found that the main compounds of AO in treating PIH are triterpenoids, especially Alisol B, Alisol C and their derivatives, which target IGF, AKT1, EGFR and MAPK1 and mediate the MAPK and PI3K-AKT signal pathways to produce diuretic and immunomodulatory activities and regulate the function of endothelial cells, anti-vascular inflammation and oxidative stress. In addition, our study preliminarily indicated that the toxic compounds in AO were mainly emodin and small amounts of fatty acids, which may produce hepato-nephrotoxicity by interfering with lipid metabolism. Furthermore, our study suggests that an optimal therapeutic effect against PIH may be achieved by increasing the triterpenoid content and reducing toxic compounds through appropriate methods. However, some shortcomings in the present study affect the robustness of our findings to some extent. First, our study was based on the identified and main bioactive compounds of AO, which may have some selection bias. Second, and crucially, further in vivo and in vitro basic research is needed to confirm and extend our conclusions. And this was exactly what we need to do next, to verify the mechanisms of AO core compounds with therapeutic efficacy in PIH and hepato-nephrotoxicity in future research.

Conclusion

This study was based on the bioinformatics analysis of network pharmacology, network toxicology, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. The finding shows that the triterpenoids were the main therapeutic compounds and emodin was the main toxic compound of Alisma Orientale. And also illustrated the potential mechanism underlying the therapeutic effects of AO against PIH and AO induced hepato-nephrotoxicity. In short, our research could guide directions for subsequent basic experimental verification and provide points of view for enhance efficacy and reduce toxicity in clinical.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the databases of TCMSP, TCM-ID, TCM@Taiwan, BATMAN-TCM, TOXNET, CTD, PharmMapper, Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB, including SwissADME, SwissTargetPrediction and Swiss Dock), Uniport, GeneCards, DisGeNET, OMIM, STRING, Metascape, bioinformatics and Cytoscape, Discovery Studio 2019 software for provided the data and making the charts.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

YL designed the study and wrote the manuscript, MY derived the datasets and performed statistical analyses; YD revised the manuscript; LY and CX draw all figures and prepared the supplementary materials.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2022.1027112/full#supplementary-material

References

- Al Khalaf S., Khashan A. S., Chappell L. C., O'Reilly É J., McCarthy F. P. (2022). Role of antihypertensive treatment and blood pressure control in the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes: A population-based study of linked electronic health records. Hypertension 79, 1548–1558. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.18920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando Y., Shinozawa Y., Iijima Y., Yu B. C., Sone M., Ooi Y., et al. (2015). Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α-induced repression of GKAP42 protein levels through cGMP-dependent kinase (cGK)-Iα causes insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 5881–5892. 10.1074/jbc.M114.624759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barshir R., Fishilevich S., Iny-Stein T., Zelig O., Mazor Y., Guan-Golan Y., et al. (2021). GeneCaRNA: A comprehensive gene-centric database of human non-coding RNAs in the GeneCards suite. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 166913. 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno A. M., Allshouse A. A., Metz T. D., Theilen L. H. (2022). Trends in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in the United States from 1989 to 2020. Obstet. Gynecol. 140, 83–86. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiworapongsa T., Chaemsaithong P., Yeo L., Romero R. (2014). Pre-eclampsia part 1: Current understanding of its pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 10, 466–480. 10.1038/nrneph.2014.102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. Y. (2011). TCM Database@Taiwan: The world's largest traditional Chinese medicine database for drug screening in silico, PLoS One 6, e15939. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Wang M. C., Chen Y. Y., Chen L., Wang Y. N., Vaziri N. D., et al. (2020). Alisol B 23-acetate attenuates CKD progression by regulating the renin-angiotensin system and gut-kidney axis. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 11, 2040622320920025. 10.1177/2040622320920025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chen D. Q., Wang M., Liu D., Chen H., Dou F., et al. (2017). Role of RAS/Wnt/β-catenin axis activation in the pathogenesis of podocyte injury and tubulo-interstitial nephropathy. Chem. Biol. Interact. 273, 56–72. 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Li N., Mei Z., Ye R., Li Z., Liu J., et al. (2019). Micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy and the risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 38, 146–151. 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.01.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H., Moon S., Park J., Bak S., Ko Y., Youn B. Y. (2022). The use of artificial intelligence in complementary and alternative medicine: A systematic scoping review. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 826044. 10.3389/fphar.2022.826044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai W., Chen C., Dong G., Li G., Peng W., Liu X., et al. (2022). Alleviation of fufang fanshiliu decoction on type II diabetes mellitus by reducing insulin resistance: A comprehensive network prediction and experimental validation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 294, 115338. 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. (2017). SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 42717. 10.1038/srep42717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. (2019). SwissTargetPrediction: Updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W357-W364–w364. 10.1093/nar/gkz382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler S., Schnall J. G. (2014). Toxnet: Information on toxicology and environmental health. Am. J. Nurs. 114, 61–63. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000443783.75162.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galganska H., Jarmuszkiewicz W., Galganski L. (2021). Carbon dioxide inhibits COVID-19-type proinflammatory responses through extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2, novel carbon dioxide sensors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78, 8229–8242. 10.1007/s00018-021-04005-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Ji W., Lu M., Wang Z., Jia X., Wang D., et al. (2022). Systemic pharmacological verification of Guizhi Fuling decoction in treating endometriosis-associated pain. J. Ethnopharmacol. 297, 115540. 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosdidier A., Zoete V., Michielin O. (2011). SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W270–W277. 10.1093/nar/gkr366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzhüter K., Geertsma E. R. (2022). Uniport, not proton-symport, in a non-mammalian SLC23 transporter. J. Mol. Biol. 434, 167393. 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A. L. (2008). Network pharmacology: The next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 682–690. 10.1038/nchembio.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Wu Y., Jiang C., Wang Z., Shen C., Zhu Z., et al. (2022). Investigative on the molecular mechanism of licorice flavonoids anti-melanoma by network pharmacology, 3D/2D-QSAR, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulation. Front. Chem. 10, 843970. 10.3389/fchem.2022.843970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Sato Y. (2020). KEGG Mapper for inferring cellular functions from protein sequences. Protein Sci. 29, 28–35. 10.1002/pro.3711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H., Tang K., Liu Q., Sun Y., Huang Q., Zhu R., et al. (2013). HIM-herbal ingredients in-vivo metabolism database. J. Cheminform. 5, 28. 10.1186/1758-2946-5-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan X., Guo L., Zhu S., Cao Y., Niu Y., Han S., et al. (2022). First-trimester serum cytokine profile in pregnancies conceived after assisted reproductive technology (ART) with subsequent pregnancy-induced hypertension. Front. Immunol. 13, 930582. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.930582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. M., Kim J. H., Zhang Y., An R. B., Min B. S., Joung H., et al. (2003). Anti-complementary activity of protostane-type triterpenes from Alismatis rhizoma. Arch. Pharm. Res. 26, 463–465. 10.1007/BF02976863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Wang L., Du Z., Jin S., Song C., Jia S., et al. (2019). Identification of the lipid-lowering component of triterpenes from Alismatis rhizoma based on the MRM-based characteristic chemical profiles and support vector machine model. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 411, 3257–3268. 10.1007/s00216-019-01818-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Chen H., Yang H., Liu J., Li Y., Dang Y., et al. (2022). Study on the potential mechanism of tonifying kidney and removing dampness formula in the treatment of postmenopausal dyslipidemia based on network pharmacology, molecular docking and experimental evidence. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 918469. 10.3389/fendo.2022.918469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhang Q., Zhang R., Cheng N., Guo N., Liu Y., et al. (2019). Down-regulation of Cx43 expression on PIH-HUVEC cells attenuates monocyte-endothelial adhesion. Thromb. Res. 179, 104–113. 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang Y., Wang Y., Li Y., Yang F., Zhang P., et al. (2019). A strategy for the discovery and validation of toxicity quality marker of Chinese medicine based on network toxicology. Phytomedicine 54, 365–370. 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Ying B., Liu X., Zhang X., Yu H. (2012). An examination of the OMIM database for associating mutation to a consensus reference sequence. Protein Cell. 3, 198–203. 10.1007/s13238-012-2037-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Ouyang S., Yu B., Liu Y., Huang K., Gong J., et al. (2010). PharmMapper server: A web server for potential drug target identification using pharmacophore mapping approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W609–W614. 10.1093/nar/gkq300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Guo F., Wang Y., Li C., Zhang X., Li H., et al. (2016). BATMAN-TCM: A bioinformatics analysis tool for molecular mechANism of traditional Chinese medicine. Sci. Rep. 6, 21146. 10.1038/srep21146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh Y. C., Tan C. S., Ch'ng Y. S., Ahmad M., Asmawi M. Z., Yam M. F. (2017). Vasodilatory effects of combined traditional Chinese medicinal herbs in optimized ratio. J. Med. Food 20, 265–278. 10.1089/jmf.2016.3836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães E., Méio M., Peixoto-Filho F. M., Gonzalez S., da Costa A. C. C., Moreira M. E. L. (2020). Pregnancy-induced hypertension, preterm birth, and cord blood adipokine levels. Eur. J. Pediatr. 179, 1239–1246. 10.1007/s00431-020-03586-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Małodobra-Mazur M., Cierzniak A., Ryba M., Sozański T., Piórecki N., Kucharska A. Z. (2022). Cornus mas L. Increases glucose uptake and the expression of PPARG in insulin-resistant adipocytes. Nutrients 14, 2307. 10.3390/nu14112307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H., Kageura T., Toguchida I., Murakami T., Kishi A., Yoshikawa M. (1999). Effects of sesquiterpenes and triterpenes from the rhizome of Alisma orientale on nitric oxide production in lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages: Absolute stereostructures of alismaketones-B 23-acetate and -C 23-acetate. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 9, 3081–3086. 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00536-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohindra V., Chowdhury L. M., Chauhan N., Maurya R. K., Jena J. K. (2022). Transcriptome analysis revealed hub genes for muscle growth in Indian major carp, Catla catla (Hamilton, 1822). Genomics 114, 110393. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2022.110393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura R., Ogawa S., Takahashi Y., Fujishiro T. (2022). Cycloserine enantiomers inhibit PLP-dependent cysteine desulfurase SufS via distinct mechanisms. Febs J. 289, 5947–5970. 10.1111/febs.16455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Z., Mei S., You S., Lin Y., Cheng W., Zhou L., et al. (2022). Adverse effects of polycystic ovarian syndrome on pregnancy outcomes in women with frozen-thawed embryo transfer: Propensity score-matched study. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 878853. 10.3389/fendo.2022.878853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry H., Khalil A., Thilaganathan B. (2018). Preeclampsia and the cardiovascular system: An update. Trends cardiovasc. Med. 28, 505–513. 10.1016/j.tcm.2018.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñero J., Ramírez-Anguita J. M., Saüch-Pitarch J., Ronzano F., Centeno E., Sanz F., et al. (2020). The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D845-D855–d855. 10.1093/nar/gkz1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy M., Palmer K., Rolnik D. L., Wallace E. M., Mol B. W., Da Silva Costa F. (2022). Role of placental, fetal and maternal cardiovascular markers in predicting adverse outcome in women with suspected or confirmed pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 59, 596–605. 10.1002/uog.24851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ru J., Li P., Wang J., Zhou W., Li B., Huang C., et al. (2014). Tcmsp: A database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J. Cheminform. 6, 13. 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedorf G., Kim C., Wallace B., Mandell E. W., Nowlin T., Shepherd D., et al. (2020). rhIGF-1/BP3 preserves lung growth and prevents pulmonary hypertension in experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 201, 1120–1134. 10.1164/rccm.201910-1975OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao C., Fu B., Ji N., Pan S., Zhao X., Zhang Z., et al. (2018). Alisol B 23-acetate inhibits IgE/Ag-mediated mast cell activation and allergic reaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 4092. 10.3390/ijms19124092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Z., Pu J., Chen L., Zhang Y., Rahman K., Qin L., et al. (2016). Alisma orientale: Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology of an important traditional Chinese medicine. Am. J. Chin. Med. 44, 227–251. 10.1142/S0192415X16500142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanic B., Samardzija Nenadov D., Fa S., Pogrmic-Majkic K., Andric N. (2021). Integration of data from the cell-based ERK1/2 ELISA and the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database deciphers the potential mode of action of bisphenol A and benzo[a]pyrene in lung neoplasm. Chemosphere 285, 131527. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana N., Chung H. J., Emon N. U., Alam S., Taki M. T. I., Rudra S., et al. (2022). Biological functions of Dillenia pentagyna roxb. Against pain, inflammation, fever, diarrhea, and thrombosis: Evidenced from in vitro, in vivo, and molecular docking study. Front. Nutr. 9, 911274. 10.3389/fnut.2022.911274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D., Gable A. L., Nastou K. C., Lyon D., Kirsch R., Pyysalo S., et al. (2021). The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D605–d612. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian N. N., Zheng Y. B., Li Z. P., Zhang F. W., Zhang J. F. (2021). Histone methylatic modification mediates the tumor-suppressive activity of curcumol in hepatocellular carcinoma via an Hotair/EZH2 regulatory axis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 280, 114413. 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian T., Chen H., Zhao Y. Y. (2014). Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicology and quality control of Alisma orientale (sam.) juzep: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 158 Pt A, 373–387. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Peng Q., Wang R., Yu S., Li Q., Huang C. (2022). Efficient Microcystis removal and sulfonamide-resistance gene propagation mitigation by constructed wetlands and functional genes analysis. Chemosphere 292, 133481. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.133481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Bao X., Song L., Tian Y., Sun P. (2019). Role of miR-106-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in oxidative stress injury and inflammatory infiltration in the liver of the mouse with gestational hypertension. J. Cell. Biochem. 122, 958–968. 10.1002/jcb.29552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue B., Yu Y., Zhang Z., Guo F., Beltz T. G., Thunhorst R. L., et al. (2016). Leptin mediates high-fat diet sensitization of angiotensin II-elicited hypertension by upregulating the brain renin-angiotensin system and inflammation. Hypertension 67, 970–976. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X. W., Wang H. L., Cheng S. Q., Xia L. J., Xu X. F., Li X. R. (2022). Network pharmacology-based strategy to investigate the pharmacologic mechanisms of coptidis rhizoma for the treatment of alzheimer's disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 890046. 10.3389/fnagi.2022.890046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh H. Y., Chen Y. C., Chen F. P., Chou L. F., Chen T. J., Hwang S. J. (2009). Use of traditional Chinese medicine among pregnant women in Taiwan. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 107, 147–150. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen M. F., Tam S., Fung J., Wong D. K., Wong B. C., Lai C. L. (2006). Traditional Chinese medicine causing hepatotoxicity in patients with chronic Hepatitis B infection: A 1-year prospective study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 24, 1179–1186. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Li J., Fu X., Zhang Y., Zhang T., Wu B., et al. (2022). Endometrial thickness is an independent risk factor of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: A retrospective study of 13, 458 patients in frozen-thawed embryo transfers. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 20, 93. 10.1186/s12958-022-00965-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Li X. Y., Lin N., Zhao W. L., Huang X. Q., Chen Y., et al. (2017). Diuretic activity of compatible triterpene components of alismatis rhizoma. Molecules 22, 1459. 10.3390/molecules22091459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Liu L., Liu D., Li Y., He J., Shen L. (2022). 17β-Estradiol promotes angiogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by upregulating the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 3864–3873. 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.07.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., Chang M., Khodabakhshi A. H., Tanaseichuk O., et al. (2019). Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 10, 1523. 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X., Holmes E., Nicholson J. K., Loo R. L. (2016). Automatic spectroscopic data categorization by clustering analysis (asclan): A data-driven approach for distinguishing discriminatory metabolites for phenotypic subclasses. Anal. Chem. 88, 5670–5679. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zouhal H., Berro A. J., Kazwini S., Saeidi A., Jayavel A., Clark C. C. T., et al. (2021). Effects of exercise training on bone health parameters in individuals with obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 12, 807110. 10.3389/fphys.2021.807110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.