Abstract

Persistent organic chemicals are non-biodegradable in nature and have a tendency to bioaccumulate in the top organisms of the food chain. We measured persistent organic chemicals, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), and benzotriazole-based ultraviolet stabilizers (UV-BTs), in the serum of captive king penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus) using gas chromatography with an electron capture detector and mass spectrometry to examine their age-related accumulation. PCBs, DDE, UV-PS, and UV-9 were detected in the blood of captive king penguins, and the concentrations of total PCBs, DDE, and UV-9 were positively correlated with age. These results suggest that there is a similar age-related accumulation of persistent organic chemicals in marine birds in the wild, and that older individuals are at a higher risk of contamination.

Keywords: benzotriazole-based ultraviolet stabilizers, blood, dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene, marine bird, polychlorinated biphenyls

Persistent organic chemicals are not easily decomposed in nature and their presence has raised concerns regarding various adverse effects on living organisms. Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are persistent organic chemicals released into the environment, mainly from densely populated areas. The marine environment is widely contaminated by POPs. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), and the metabolite dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), which are typical POPs, are persistent, long-range transported, and accumulated in marine organisms [6]. Consequently, they bio-accumulate in the top organisms of the marine food chain [3, 7, 10, 11].

In recent years, a high frequency of plastic feeding has been observed in marine organisms, particularly marine birds [22]. Although plastics are physically fragmented, they are chemically persistent and remain in the ocean for long periods of time [8]. Marine plastics adsorb POPs from seawater over time while floating in the marine environment, resulting in a concentration of POPs that is approximately one million times higher than that of seawater [14]. Furthermore, plastic additives such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers and benzotriazole-based ultraviolet stabilizers (UV-BTs) remain in plastics without being fully leached out into seawater. On ingestion through feeding, these plastic additives are transferred to the bodies of marine birds [20]. Hence, marine birds are subjected to accumulation of and exposure to various persistent organic chemicals, and some biological effects of these chemicals have been reported [2, 15].

The accumulation of persistent organic chemicals such as POPs and plastic additives can increase with age in marine birds. Clarification of this issue will facilitate the environmental risk assessment of persistent organic chemical substances in marine birds. However, age estimation is difficult for wild avian species; therefore, assessing potential accumulation of persistent organic chemicals with age is difficult to address. Aquariums are the best places to study such relationships, because the ages of marine birds are known. In this study, we investigated the relationship between age and levels of persistent organic chemical substances in captive king penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus) as a model for marine birds.

Eight (male: n=4, female: n=4) healthy king penguins kept at Kamogawa Sea World, located in Kamogawa city, Chiba Prefecture, Japan, were used in this study. The ages of the males were 1, 2, 14, and 18 years, and those of the females were 14,18, 28, and 32 years. The basic information of each individual is listed in Supplementary Table 1. One female estimated to be more than 28 years was assumed to be 28 years old for subsequent analyses. The breeding environment was maintained at 12°C under both ambient and water temperatures. Between November and December 2020, after the breeding season, 5–6 mL of blood was collected from the caudal artery at the base of the tail. The blood was then centrifuged and 1.2–1.5 mL of serum was separated. Serum was stored in a freezer at −50°C until further analysis. Sampling was performed safely by veterinarians according to the guidelines of Kamogawa Sea World.

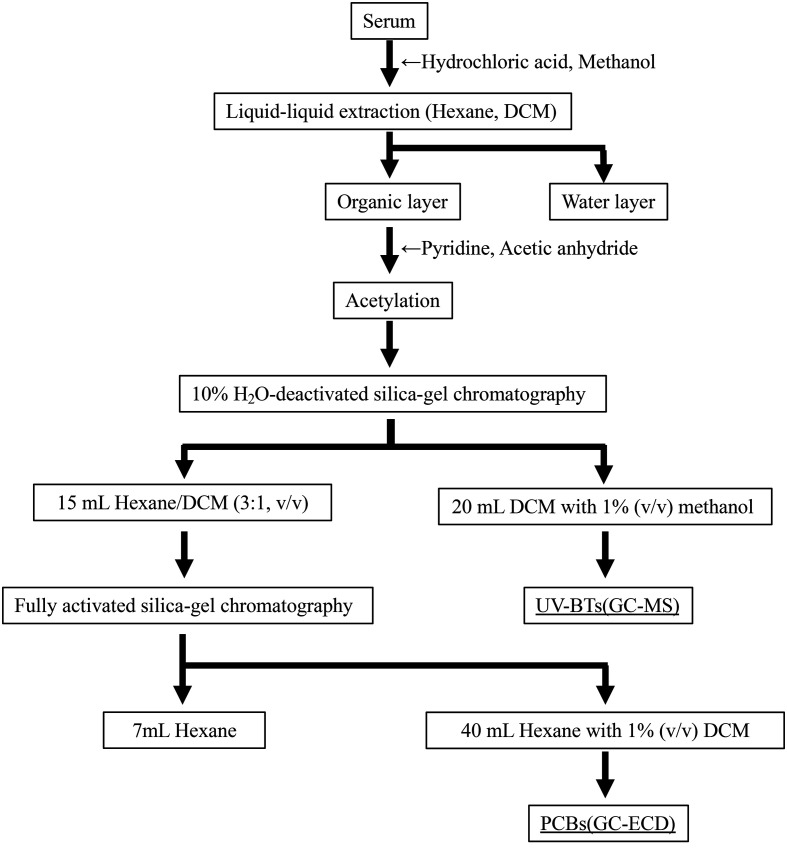

All solvents and reagents for extraction and cleanup procedures, except for dichloromethane (DCM), were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). The DCM used was from Kanto Chemical (Tokyo, Japan). One mL of serum was transferred to a glass tube for each individual and 50 µL of surrogate mixtures in acetone (three PCB surrogates: 70 ng/mL of CB-14, CB-54 and 28 ng/mL of CB-204, and four UV-BT surrogates: 2 μg/mL of UV326-d3, UV327-d20, 13C6-UV328 and UV-P-d3) was spiked. These internal standards were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Tewksbury, MA, USA; the three PCBs), Hayashi Pure Chemical Ind., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan; 13C6-UV328), and Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, ON, Canada; the other three UV-BTs). Detailed information on the standard chemicals used in this study is available in Yamashita et al. [23]. The analytical procedure is illustrated in Fig. 1. First, 0.5 mL of hydrochloric acid (HCl) was added to the tube. Next, 1 mL of methanol was added, and the mixture was stirred. Liquid–liquid extractions with 3 mL of hexane were conducted three times, followed by liquid–liquid extraction with 3 mL of DCM, and all the organic layers were combined in a pear-shaped flask. The solvent was then evaporated using a rotary evaporator and transferred to a glass tube. The solvent was evaporated under a nitrogen stream, and 50 µL of pyridine and acetic anhydride were added. The glass tube was tightly capped and kept in a sand bath at 45°C for ≥12 hr to complete the acetylation. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.2 mL of HCl, and the target compounds were extracted five times with hexane. The hexane extracts were rotary evaporated and subjected to 10% H2O–deactivated silica-gel chromatography (I. D. 1 cm × 9 cm, Wakogel®Q-22) with an elution of 15 mL hexane/DCM (3:1, v/v), followed by 20 mL DCM with 1% (v/v) methanol. The DCM with methanol fraction containing acetylated UV-BTs was rotary-evaporated and transferred to a brown glass ampoule. The solvent was evaporated to dryness under a nitrogen stream, the residue was dissolved in 100 µL isooctane to which internal standards (acenaphthene-d8 and chrysene-d12 at 5 μg/mL) were added, and UV-BTs were measured using a gas chromatograph equipped with a mass spectrometer (GC-MS; 7890A/5977; Agilent Technology, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The hexane/DCM fraction was rotary evaporated and the solvent was replaced with hexane. This fraction was eluted by fully activated silica–gel chromatography (0.45 cm i.d. × 18 cm, Wakogel®Q-22) with 7 mL of hexane (first fraction) followed by 40 mL of hexane with 1% (v/v) DCM (second fraction). The second fraction containing PCBs was rotary evaporated, transferred to a 1 mL clear glass ampoule, evaporated to dryness under a nitrogen stream, dissolved in 100–1,500 µL of isooctane, and analyzed for PCBs on a gas chromatograph equipped with an electron capture detector (GC-ECD; 7890A. Agilent Technology). The target compounds were 26 congeners of PCBs (IUPAC numbers 8/5, 18, 28, 52, 44, 66/95, 90/101, 110/77, 149/106, 118, 132/153, 105, 138/160, 187, 128, 180, 170/190, and 206) and seven compounds of UV-BTs (UV-P, UV-PS, UV-9, UV-320, UV-326, UV-327, and UV-328). In addition, there was a DDE peak in the GC-ECD chromatograms where PCBs were measured. Therefore, we quantified DDE concentration. A procedural blank was run for the sample analysis, and the limit of quantitation (LOQ) was set at three times the concentration of the blank. The LOD and LOQ values of each PCB congener and each UV-BT compound are listed in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3, respectively.

Fig. 1.

The analytical procedure of polychlorinated biphenyls and benzotriazole-based ultraviolet stabilizers.

Single point quantitative calibration curves (0.48 μg/mL) for PCBs and five-point quantitative calibration curves (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 μg/mL) for UV-BTs were obtained using each standard. The concentration of each component was calculated by correcting the corresponding surrogate recovery rate. No corrections were made for UV-PS, UV-9, or UV-320 because there were no corresponding surrogates.

The reproducibility of this analytical procedure was confirmed by analyzing four aliquots of another blood sample for PCBs and UV-BTs, which were prepared for QA/QC. The relative standard deviation of the reproducibility tests was 2.5–7.5% for PCBs and 1.4–7.9% for UV-BTs. Recovery was tested by spiking aliquots of the blood with concentration-certified standards; the recovery rates were 90.9–131% for PCBs and 75.2–110% for UV-BTs.

For age and each chemical concentration, the Shapiro–Wilk test was performed to determine a normal distribution. Correlations were investigated using Spearman’s correlation analysis for non-parametric data. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

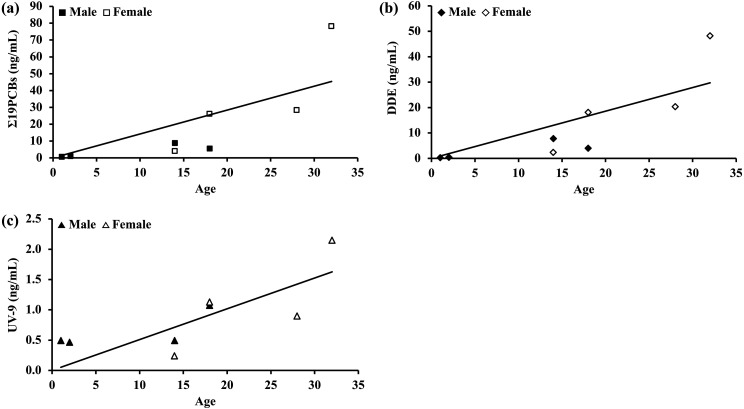

The blood concentrations of 26 PCB congeners were measured, and 19 congeners were detected (the concentrations of each congener are shown in Supplementary Table 2). The total PCB concentration detected (Σ19PCBs) is listed in Table 1. Seven congeners (IUPAC numbers: 8/5, 18, 66/95, and 110/77) were not detected. A significant positive correlation between Σ19PCBs and age was observed (Fig. 2a; Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient rho=0.94, P=0.0005).

Table 1. Blood concentration of total polychlorinated biphenyls (Σ19PCBs), dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), UV-PS and UV-9 in king penguins.

| Statistic value | Σ19PCBs | DDE | UV-PS | UV-9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (ng/mL) | 7.14 | 5.91 | 0.057 | 0.69 |

| Average (ng/mL) | 19.1 | 12.7 | 0.057 | 0.87 |

| Minimum–Maximum (ng/mL) | 0.61−78.2 | 0.27−48.2 | 0.050−0.067 | 0.24−2.15 |

| Detection rate (%) | 100 | 100 | 25 | 100 |

Fig. 2.

The relationships between the measured (a) Σ19 polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), (b) dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), and (c) UV-9 and age. Significant positive correlations between these chemicals and age were found (Σ19PCBs, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, n=8, rho=0.94, P=0.0005; DDE, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, n=8, rho=0.94, P=0.0005; UV-9, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, n=8, r=0.77, P=0.03).

DDE concentrations are shown in Table 1. A significant, strong positive correlation between DDE and age was observed (Fig. 2b: Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, rho=0.94, P=0.0005).

The blood concentrations of the seven UV-BT compounds were measured. Two compounds (UV-PS and UV-9) are listed in Table 1. Five compounds (UV-P, UV-320, UV-326, UV-327, and UV-328) were undetectable. UV-PS was detected in two of the eight individuals. A significant positive correlation was found between UV-9 exposure and age (Fig. 2c; Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, n=8, r=0.77, P=0.03).

In this study, we measured blood PCBs, DDE, and UV-BT concentrations in captive king penguins. PCB132/153 was the congener with the highest concentration among the target PCB congeners, and we selected PCB153 for comparison with other references. Although we could not separate PCB132 and PCB153 in the GC-ECD analysis, PCB153 is a more dominant congener than PCB132 [16]. The concentrations of PCB153 (0.21–28.3 ng/mL, 6.62 ng/mL on average) and DDE (0.27–48.2 ng/mL, 12.7 ng/mL on average) in blood were compared with those reported for marine birds in the Northern Hemisphere. PCB-153 concentrations in the blood of two albatross species, the laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis) and the black–footed albatross (Phoebastria nigripes) in the North Pacific Ocean were reported to average 6.1 and 35.3 ng/g wet weight, respectively [12], while blood DDE concentrations were reported to be 27 and 125 ng/mL, respectively [9]. The POP concentrations in the albatross species were similar to or one order of magnitude higher than those observed in the present study. This is probably because albatross highly bioaccumulate POPs due to their feeding habitats [23]. On the other hand, PCB-132/153 concentrations in the blood of two species of shearwaters, short–tailed shearwater (Puffinus tenuirostris) and sooty shearwater (Puffinus griseus), averaged 0.60 and 0.06 ng/mL, respectively, and DDE in blood was 1.25 and 0.18 ng/mL, respectively [Rei Yamashita, personal communication]. These values were lower than those observed in the present study. These results could be due to differences in food items. The Kamogawa aquarium uses fish species collected from the seas around Japan and the east coast of Canada to feed the king penguins. Fish in the coastal zone are probably more contaminated with POPs than those in the open ocean, which constitute the diet of shearwaters.

This may be the first study to report UV-9 in marine birds. UV-BTs are UV stabilizers that are used in various plastic products to prevent their degradation by UV light. UV-BTs can be regarded as plastic-derived chemical substances and are thus considered an indicator of plastic feeding. In this study, UV-PS and UV-9 were the only UV-BTs detected in the blood; UV-PS is present in plastic bags and UV-9 in food packages [19]. UV-PS and UV-9 have been reported to have androgen receptor antagonist activity [19], raising concerns about their biological effects. Plastic feeding is unlikely in a captive environment, and the two compounds detected in this study were thought to be derived from food (i.e., plastic taken in by the prey fish through the digestive organs). Further studies are required to assess the current status of UV-BTs in wild marine birds. Our results could provide a reference source for studying blood UV-BT concentrations in wild marine birds.

A significant positive correlation was found between PCB, DDE, and UV-9 concentrations in the blood and the age of king penguins. The possibility that such correlation is due to sex differences cannot be completely ruled out because of the sex bias in age in the present sample set. However, previous studies on seabirds have reported that POP concentrations are lower in females than in males during the breeding season due to transfer to eggs by egg-laying, and that there is no difference between non-breeding males and females [13]. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, all females in this study experienced egg-laying at least once. Here, higher concentrations were detected in older females, and we believe that this indicates age-related accumulation. To examine the differences in the accumulation of persistent organic chemicals between males and females, and the changes in the concentration of persistent organic chemicals in relation to the number of times females lay eggs, it is necessary to unify the sexes and increase the sample size; this is a subject that should be addressed in future studies. PCB-153 and DDE are highly lipophilic substances with logarithmic octanol–water partition coefficients (log Kow) of 6.83 and 6.37, respectively [5]. Substances that are highly hydrophobic and persistent are likely to undergo biomagnification [21]. For example, PCBs and DDTs, including DDE, have both been detected in the preen gland oil of marine birds, suggesting that they bioaccumulate through food webs [23]. On the other hand, UV-9 has a log Kow value of 3.16 [5], which is relatively small compared to those of PCB-153 and DDE. Therefore, UV-9 might not be expected to bioaccumulate with age in the king penguins studied here. However, we found a positive and statistically significant correlation between blood UV-9 levels and age. Mechanisms to excrete UV-9 may be lacking, thus getting retained in the penguin’s body. Peng et al. studied the bioaccumulation of UV-BTs in an ecosystem in the Pearl River catchment, China, and showed that most UV-BTs were not biomagnified [17, 18]. Their target UV-BTs did not include UV-9, but biomagnification of UV-P, with hydrophobicity similar to that of UV-9, was not observed. The interaction between UV-BT molecules and biomolecules can be considered in future studies.

These results indicate that the accumulation of hydrophobic chemicals is associated with age in captive marine birds, which are known for their longevity. Reproductive success is higher and more stable in older individuals [1, 4]. Thus, these results suggest that population maintenance may be affected if older individuals are exposed to high concentrations of these chemicals and are unable to achieve reproductive success.

In summary, PCBs, DDE, UV-PS, and UV-9 were detected in the blood of captive king penguins, indicating that they were exposed to these chemicals. Based on the age-related information available for captive penguins, the concentrations of total PCBs, DDE, and UV-9 in the blood were positively correlated with age. These results suggest a similar accumulation of age-related chemicals in marine birds in the field. In marine birds, older individuals with high reproductive success are important for population maintenance. Older individuals who accumulate chemicals and are exposed to higher concentrations are likely at a higher risk for persistent organic chemical contamination.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Supplementary

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Kamogawa Sea World staff for collecting the samples.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angelier F, Weimerskirch H, Dano S, Chastel O. 2007. Age, experience and reproductive performance in a long-lived bird: a hormonal perspective. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 61: 611–621. doi: 10.1007/s00265-006-0290-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barron MG, Galbraith H, Beltman D. 1995. Comparative reproductive and developmental toxicology of PCBs in birds. Comp Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol 112: 1–14. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(95)00074-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayarri S, Baldassarri LT, Iacovella N, Ferrara F, di Domenico A. 2001. PCDDs, PCDFs, PCBs and DDE in edible marine species from the Adriatic Sea. Chemosphere 43: 601–610. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00412-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman M, Gaillard JM, Weimerskirch H. 2009. Contrasted patterns of age-specific reproduction in long-lived seabirds. Proc Biol Sci 276: 375–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ChemSrc. 2021. A Smart Chem-Search Engine. https://www.chemsrc.com/en/ [accessed on July 8, 2022].

- 6.Corsolini S, Sarà G. 2017. The trophic transfer of persistent pollutants (HCB, DDTs, PCBs) within polar marine food webs. Chemosphere 177: 189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.02.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desforges JP, Hall A, McConnell B, Rosing-Asvid A, Barber JL, Brownlow A, De Guise S, Eulaers I, Jepson PD, Letcher RJ, Levin M, Ross PS, Samarra F, Víkingson G, Sonne C, Dietz R. 2018. Predicting global killer whale population collapse from PCB pollution. Science 361: 1373–1376. doi: 10.1126/science.aat1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everaert G, De Rijcke M, Lonneville B, Janssen CR, Backhaus T, Mees J, van Sebille E, Koelmans AA, Catarino AI, Vandegehuchte MB. 2020. Risks of floating microplastic in the global ocean. Environ Pollut 267: 115499. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finkelstein M, Keitt BS, Croll DA, Tershy B, Jarman WM, Rodriguez-Pastor S, Anderson DJ, Sievert PR, Smith DR. 2006. Albatross species demonstrate regional differences in North Pacific marine contamination. Ecol Appl 16: 678–686. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[0678:ASDRDI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guruge KS, Tanaka H, Tanabe S. 2001. Concentration and toxic potential of polychlorinated biphenyl congeners in migratory oceanic birds from the North Pacific and the Southern Ocean. Mar Environ Res 52: 271–288. doi: 10.1016/S0141-1136(01)00099-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller JM, Kucklick JR, Stamper MA, Harms CA, McClellan-Green PD. 2004. Associations between organochlorine contaminant concentrations and clinical health parameters in loggerhead sea turtles from North Carolina, USA. Environ Health Perspect 112: 1074–1079. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klasson-Wehler E, Bergman A, Athanasiadou M, Ludwig JP, Auman HJ, Kannan K, van den Berg M, Murk AJ, Feyk LA, Giesy JP. 1997. Hydroxylated and methylsulfonyl polychlorinated biphenyl metabolites in albatrosses from Midway Atoll, North Pacific Ocean. Environ Toxicol Chem 17: 1620–1625. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620170825 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallory ML, Braune BM, Forbes MRL. 2006. Contaminant concentrations in breeding and non-breeding northern fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis L.) from the Canadian high arctic. Chemosphere 64: 1541–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.11.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mato Y, Isobe T, Takada H, Kanehiro H, Ohtake C, Kaminuma T. 2001. Plastic resin pellets as a transport medium for toxic chemicals in the marine environment. Environ Sci Technol 35: 318–324. doi: 10.1021/es0010498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNabb FMA, Fox GA. 2003. Avian thyroid development in chemically contaminated environments: is there evidence of alterations in thyroid function and development? Evol Dev 5: 76–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-142X.2003.03012.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niimi AJ, Lee HB, Muir DCG. 1996. Environmental assessment and ecotoxicological implications of the co-elution of PCB congeners 132 and 153. Chemospnere 32: 627–638. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(95)00367-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng X, Fan Y, Jin J, Xiong S, Liu J, Tang C. 2017. Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of ultraviolet absorbents in marine wildlife of the Pearl River Estuarine, South China Sea. Environ Pollut 225: 55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng X, Zhu Z, Xiong S, Fan Y, Chen G, Tang C. 2020. Tissue distribution, growth dilution, and species-specific bioaccumulation of organic ultraviolet absorbents in wildlife freshwater fish in the Pearl River Catchment, China. Environ Toxicol Chem 39: 343–351. doi: 10.1002/etc.4616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakuragi Y, Takada H, Sato H, Kubota A, Terasaki M, Takeuchi S, Ikeda-Araki A, Watanabe Y, Kitamura S, Kojima H. 2021. An analytical survey of benzotriazole UV stabilizers in plastic products and their endocrine-disrupting potential via human estrogen and androgen receptors. Sci Total Environ 800: 149374. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka K, Watanuki Y, Takada H, Ishizuka M, Yamashita R, Kazama M, Hiki N, Kashiwada F, Mizukawa K, Mizukawa H, Hyrenbach D, Hester M, Ikenaka Y, Nakayama SMM. 2020. In vivo accumulation of plastic-derived chemicals into seabird tissues. Curr Biol 30: 723–728.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeuchi I, Miyoshi N, Mizukawa K, Takada H, Ikemoto T, Omori K, Tsuchiya K. 2009. Biomagnification profiles of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, alkylphenols and polychlorinated biphenyls in Tokyo Bay elucidated by δ13C and δ15N isotope ratios as guides to trophic web structure. Mar Poll Bull 58: 663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamashita R, Tanaka K, Takada H. 2016. Marine plastic pollution: dynamics of plastic debris in marine ecosystem and effect on marine organisms. Japanese J Ecol 66: 51–68 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamashita R, Hiki N, Kashiwada F, Takada H, Mizukawa K, Hardesty BD, Roman L, Hyrenbach D, Ryan PG, Dilley BJ, Muñoz-pérez JP, Valle CA, Pham CK, Frias J, Nishizawa B, Takahashi A, Thiebot JB, Will A, Kokubun N, Watanabe YY, Yamamoto T, Shiomi K, Shimabukuro U, Watanuki Y. 2021. Plastic additives and legacy persistent organic pollutants in the preen gland oil of seabirds sampled across the globe. Environ. Monit. Contam. Res. 1: 97–112. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.