Abstract

Two virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori, cagA and vacA, have been known to play a role in the development of severe gastric symptoms. However, they are not always associated with peptic ulcer or gastric cancer. To predict the disease outcome more accurately, it is necessary to understand the risk of severe symptoms linked to other virulence factors. Several other virulence factors of H. pylori have also been reported to be associated with disease outcomes, although there are many controversial descriptions. H. pylori isolates from Koreans may be useful in evaluating the relevance of other virulence factors to clinical symptoms of gastric diseases because the majority of Koreans are infected by toxigenic strains of H. pylori bearing cagA and vacA. In this study, a total of 116 H. pylori strains from Korean patients with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancers were genotyped. The presence of virulence factors vacAs1c, alpA, babA2, hopZ, and the extremely strong vacuolating toxin was found to contribute significantly to the development of severe gastric symptoms. The genotype combination vacAs1c/alpA/babA2 was the most predictable determinant for the development of severe symptoms, and the presence of babA2 was found to be the most critical factor. This study provides important information on the virulence factors that contribute to the development of severe gastric symptoms and will assist in predicting clinical disease outcomes due to H. pylori infection.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, vacAs1c, alpA, babA2, hopZ, gastric diseases

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative, spiral-shaped capnophilic bacterium [1] which is closely associated with the epithelial surface or the surface mucus of gastric mucosa [2]. H. pylori is the causative agent of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer, and prolonged carriage is known to be a significant risk factor for the development of gastric cancer [3-7]. Therefore, H. pylori was defined as a Class 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1994, and estimates indicate that more than half of the global population is infected by H. pylori [7]. In 2020, the International Agency for Research on Cancer reported that H. pylori was responsible for the most infectious pathogen-related carcinogenesis in 2018 (https://gco.iarc.fr/causes/infections). In addition, most Koreans are carriers of H. pylori by early childhood [8], which is believed to be a major reason for the high prevalence of gastric disorders including gastric cancer in Korea [9].

The incidence of gastric cancer differs geographically [10], and East Asian countries have the highest incidence rates of this disease worldwide [11]. This regional discrepancy can be partly explained by different prevalence rates of H. pylori infection [11], which in East Asian countries are reported to be higher than those in Western countries [8]. However, the incidence of gastric cancer in countries located in West South Asia is similar to that in Western countries, even though H. pylori infection is more prevalent in West South Asia than in Western countries [11]. These studies suggest that other factors in addition to infection could play a role in the pathogenesis of H. pylori and the development of pestilential gastric symptoms.

H. pylori is a highly heterogeneous bacterium [12], and various virulence factors have been identified in isolates [5, 13]. The cagA and vacA genes have been extensively studied as virulence markers of H. pylori strains, and toxigenic strains of H. pylori carrying cagA and vacA are closely associated with the development of gastric diseases such as peptic ulcer and gastric cancer [2, 10, 11, 14, 15]. More cagA-positive strains of H. pylori have been recovered from East Asian populations than from Western populations [16], and more vacA-positive strains have been recovered from patients with peptic ulcer than from patients without peptic ulcer [17, 18]. These studies on cagA and vacA suggest that these virulence factors play an important role in the development of clinical entities of gastric diseases. However, although infections of H. pylori bearing cagA and vacA cause chronic gastritis in many cases, they are not always associated with peptic ulcer or gastric cancer [3]. Only approximately 10–15% of infected individuals were reported to develop peptic ulcer, gastric carcinoma, and mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma [6, 19]. Similarly, in Korea, even though the majority of people become infected early in life with toxigenic H. pylori strains bearing cagA and vacA [20-22], only a small proportion of infected Koreans complain of severe gastric maladies [21-23]. These studies suggest that additional virulence factors of H. pylori are involved in disease outcome.

In addition to CagA and VacA, other virulence factors, including adherence proteins, endonuclease restriction/modification systems, and vir homologs have been explored to identify their relevance to the development of different outcomes of gastric diseases. AlpA/B [17, 24, 25], BabA2 [26-28], HopZ [29], OipA [30, 31], SabA [3, 5, 32], HrgA [14], HpyIII [14], IceA [33], and vir homologues [22] have been reported to be partly associated with disease outcomes, although there are many controversial descriptions. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate which of these virulence factors, in addition to CagA and VacA, critically contribute to the development of severe symptoms of gastric diseases.

Most H. pylori isolates from East Asian countries, including Korea, contain both an East Asian repeat pattern in the 3′-region of the cagA gene and the toxigenic vacA genotype, irrespective of the presentation of gastric symptoms [11, 21, 23, 34]. Therefore, H. pylori isolates recovered from the Korean population are of value in evaluating the relevance of other virulence factors in the development of clinical outcomes in addition to cagA and vacA. Here, we assessed Korean isolates of H. pylori by genotyping for different virulence factors including vacuolating toxin, adherence proteins, endonuclease restriction/modification systems, and vir homologues. In addition, we analyzed the relevance of these genes to the clinical symptoms of gastric disorders and investigated the polymorphisms of cagA and vacuolating toxin activities.

Materials and Methods

H. pylori Isolates

H. pylori strains were isolated at Gyeongsang National University Hospital (Korea), Kosin University Gospel Hospital (Korea), and St. Carollo Hospital (Korea) from 1987 to 2005, as previously described [35-37]. Briefly, biopsy specimens were inoculated by smearing onto Mueller-Hinton agar (Merck, USA) plates containing 10%bovine serum (Gibco, USA), vancomycin (Merck, 10 μg/ml), nalidixic acid (Merck, 25 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (Merck, 1 μg/ml). The plates were incubated at 37°C under 10% CO2 and 100% humidity for 7 days. The bacteria were identified as H. pylori on the basis of their morphology, urease test, and 16S rRNA PCR. To amplify the 16SrRNA gene of H. pylori, primers of PV31 (5'-CGGCCCAGACTCCTACGGG-3') and PV32 (5'-TTACCGCGG CTGCTGGCAC-3') were designed based on the previous publication [38]. The PCR amplification was performed with AccuPower PCR PreMix (Cat. No. K-2016, Bioneer, Korea) containing 1 unit of Top DNA polymerase, 250 μM dNTPs, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 30 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 10 pmol of the primers. The PCR condition was as follows: pre-denaturation at 94°C for 5 min; followed by denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, annealing at 55°C for 30 sec, extension at 72°C for 3 min (35 cycles), and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. PCR-amplified products (180 bp) were detected by agarose gel electrophoresis to identify H. pylori.

All isolates were deposited at the former H. pylori Korean Type Culture Collection (HpKTCC; College of Medicine, Gyeongsang National University, Korea; 2006–2015) with anonymized clinical information. Among the deposited strains, H. pylori strains recovered from patients with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, and gastric cancer were selected for analysis. Frozen stocks within 50 subcultures were revitalized and grown on Brucella agar (Accumedia, USA) plates containing the same composition as Mueller-Hinton agar at 37°C under 10% CO2 and 100% humidity.

Preparation of Genomic DNA from H. pylori

Genomic DNA was extracted from H. pylori as described previously [39]. Briefly, cultured bacterial colonies were collected and suspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2). Bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 12,700 ×g for 5 min and suspended in 200 μl of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (pH 7.0). After adding 600 μg of lysozyme (Genery, China), the cell mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Then, after adding 20 μl of 10%SDS solution and 10 μg of RNase (RBC, Taiwan), the cell mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h, followed by treatment with 120 μg of Protease K (GeNet Bio, Korea) and 172 μg of pronase (Merck) at 37°C for 1 h. After adding 1/10 volume of 5% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (BDH Chemicals Ltd., England)-0.5 M NaCl solution and incubating at 37°C for 1 h, the mixture was chloroform extracted by adding an equal volume of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) solution and vortexing. After centrifuging at 12,700 ×g for 10 min, the aqueous layer was collected, mixed with 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2), and added to an equal volume of isopropanol. After incubating at −70°C for 20 min, the sample was centrifuged at 12,700 ×g for 10 min. DNA pellets were washed with 1 mL of 70% ethanol, dried completely, dissolved in 30 μl of TE buffer, and frozen at -70°C until required.

PCR

Extracted DNA (50 ng) was PCR amplified with AccuPower PCR PreMix using 10 pmol of forward and reverse primers listed in Table 1. After pre-denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, PCR was carried out at the annealing temperature for 1 min with extension at 72°C for 30 sec, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. The annealing temperatures and number of cycles are listed in Table 1. Amplified DNA was separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized and analyzed with a Fluor-S MultiImager (Bio-Rad, USA).

Table 1.

Sequences of oligonucleotide primers and PCR conditions for the genotyping of H. pylori isolates.

| Genes | primer F (5'⇒3') | Primer R (5‘⇒3’) | Annealing temp | Cycles | Amplified DNA size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cagA5’region | GATAACAGGCAAGCTTTTGATG | CTGCAAAAGATTGTTTGGCAGA | 55°C | 35 | 349 | [16] |

| cagA EPIYA FR | ACCCTAGTCGGTAATGGG | GCAATTTTGTTAATCCGGTC | 48°C | 30 | 293~299 | [72] |

| cagA EPIYA JSR | GCAATTTTGTTAATCCGGTC | GCTTTAGCTTCTGAYACYGC | 48°C | 30 | 222 | [72] |

| vacA s1/s2 | ATGGAAATACAACAAACACAC | CTGCTTGAATGCGCCAAAC | 52°C | 35 | 259/286 | [73] |

| vacA s1a s1a | TCTYGCTTTAGTAGGAGC | CTGCTTGAATGCGCCAAAC | 52°C | 35 | 212 | [16] |

| vacA s1b ss3 | AGCGCCATACCGCAAGAG | CTGCTTGAATGCGCCAAAC | 55°C | 35 | 187 | [73] |

| vacA s1c s1c | CTYCTTTAGTRGGGYTA | CTGCTTGAATGCGCCAAAC | 55°C | 35 | 213 | [16] |

| vacA m1/m2 | CAATCTGTCCAATCAAGCGAG | GCGTCTAAATAATTCCAAGG | 52°C | 35 | 570/645 | [16] |

| vacA i1 | TTAATTTAACGCTGTTTGAAG | GTTGGGATTGGGGGAATGCCG | 53°C | 35 | 426 | [74] |

| vacA i2 | GATCAACGCTCTGATTTGA | GTTGGGATTGGGGGAATGCCG | 53°C | 35 | 432 | [74] |

| alpA | ACGCTTTCTCCCAATACC | AACACATTCCCCGCATTC | 65°C | 40 | 304 | [75] |

| alpB | TCGCCGGGACTTTGGGCAAC | TGCGCTAAAGCGGCGTCCAA | 55°C | 35 | 505 | Designed |

| oipA | CAAGCGCTTAACAGATAGGC | AAGGCGTTTTCTGCTGAAGC | 55°C | 35 | 450 | [76] |

| babA2 | AATCCAAAAAGGAGAAAAAACATGAAA | ATAGTTGTCTGAAAGATC | 50°C | 38 | 180 | [26] |

| hopZ | GCCTGATATGGGTGGCATGGG | ATTTGATAGCCCGCGCTGAT | 50°C | 35 | 493 | [77] |

| sabA | GAGCTATTGACCAGCTCAATG | TAGTTTGGATTCGTTCTCATTA | 50°C | 35 | 447 | [78] |

| iceA1 | TATTTCTGGAACTTGCGCAACCTGAT | GGCCTACAACCGCATGGATAT | 55°C | 30 | 642 | [79] |

| iceA2 | CGGCTGTAGGCACTAAAGCTA | TCAATCCTATGTGAAACAATGATCGTT | 55°C | 30 | 662 | [79] |

| iceA1Δ94 | GGTGAGTCGTTGGGTAAGCGTTACAGAATT | CACAACCATCATATTCAGCCTCCCCCTCATA | 55°C | 30 | 520 | [79] |

| hrgA | TCTCGTGAAAGAGAATTTCC | TAAGTGTGGGTATATCAATC | 55°C | 30 | 682 | [80] |

| hpyIIIR | CTCATTGCTGTGAGGGAT | TCTTGATAGGATCTTGCG | 55°C | 30 | 443 | [80] |

| hpyIIIM | CTCATTGCTGTGAGGGAT | TCTTGATAGGATCTTGCG | 55°C | 30 | 562 | [80] |

| dupA jhp0917 | TGGTTTCTACTGACAGAGCGC | AACACGCTGACAGGACAATCTCCC | 57°C | 30 | 307 | [22] |

| dupA jhp0918 | CCTATATCGCTAACGCGCGCTC | AAGCTGAAGCGTTTGTAACG | 57°C | 30 | 276 | [22] |

For nucleotide sequence analysis, PCR was performed using the pfu PCR Kit (Cat. No. EBT-11011, ELPIS, Korea), 4 ng of genomic DNA, 10 pM of primers, and 0.5 unit of pfu DNA polymerase under the conditions described above. Amplified PCR product was purified using an EZ-Pure PCR Purification Kit (Cat. No. EP201-50N, Enzynomics, Korea). Purified PCR products were sequenced using an Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Carlsbad, USA).

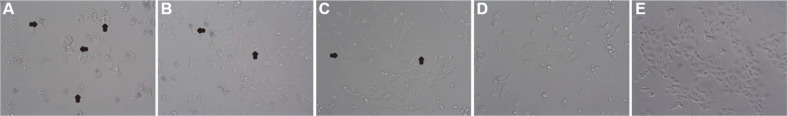

Vacuolation Activity Test

Vacuolation activity was measured using RK-13 (ATCC CCL-37) cells as described previously with slight modifications [40]. Briefly, RK-13 cells were grown overnight in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), adjusted to 1.5 × 104 cells/100 μl, added in 96-well microplates at 100 μl/well and incubated for 4 h. H. pylori strains were grown in a thin-layer liquid culture system [1]. Briefly, bacteria were grown overnight on a Petri dish (100 mm diameter) containing 3 ml of Brucella broth (Accumedia) supplemented with 10% bovine serum (Gibco) at 37°C for 24 h in an atmosphere of 10% CO2 and 100% humidity. Supernatants (50 μl) were harvested, serially (1:2) diluted with the culture medium, added into 96-well plates of RK-13 cells, and incubated at 37°C for 12 h. The degree of vacuolation was observed under a light microscope (Olympus, Japan). Vacuolation activity was defined as the reciprocal of the dilution factor of the culture supernatant in which 10% of cells were vacuolated. Vacuolation activity was defined as the reciprocal of the dilution factor of the culture supernatant in which 10% of cells were vacuolated.

Statistical Analysis

The two-way association between genotypes of virulent factors and clinical entities of gastric disease was examined using the Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. The distribution of patient ages among clinical entities of gastric disorder was assessed with an independent two-sample t-test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Odds ratios (ORs) adjusted for sex were given with 95% confidence intervals to estimate the risk. All data were statistically analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 22 (SPSS Inc., USA).

Results

Patients and H. pylori Isolates

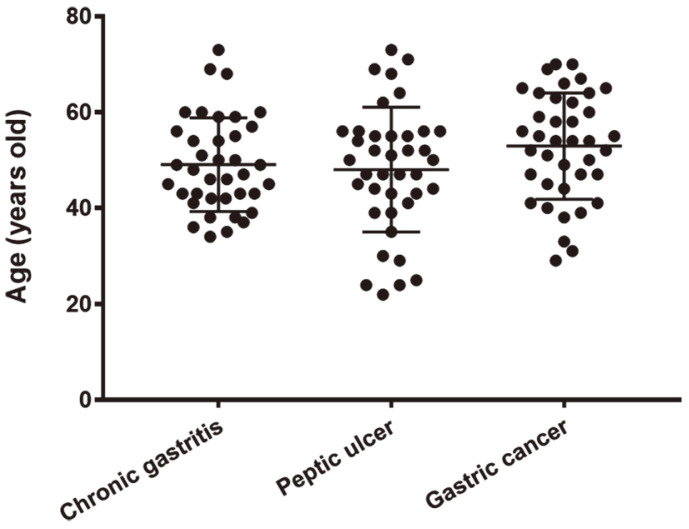

A total of 116 H. pylori strains were recovered from patients diagnosed clinically and pathologically with chronic gastritis (38 strains; male/female, 18/20), peptic ulcers (39 strains; male/female, 32/6), and gastric cancers (39 strains; male/female, 25/14) [35-37]. Patients were from the southern area of the Korean peninsula. The average patient age with standard deviation was 48.6 ± 12.1 years for those with chronic gastritis, 48.4 ± 13 years for those with peptic ulcer, and 52.9 ± 11.1 years for those with gastric cancer. Patient ages did not significantly differ from each other, although the average age of patients with gastric cancer was higher than that of others (Fig. 1). Strains that had been subcultured less than 50 times were chosen for this study to minimize the probability of genomic mutation during in vitro maintenance.

Fig. 1.

Age distribution of patients with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, or gastric cancer.

Polymorphism of vacA Alleles

vacA allele polymorphisms are determined by variation in the signal sequence region (s1a, s1b, s1c, and s2), mid-region (m1 and m2), and intermediate region (i1, i2, and i3). In this study, the vacA genotype in the signal sequence region was the s1 type for all 116 H. pylori strains, whereas 109 strains (94%) were grouped as the m1 type in the mid-region, and 110 strains (95%) were grouped as the i1 type in the intermediate region (Table 2). No strains exhibited the s2 type. Only 6% and 2.5% of strains were grouped as m2 and i2 types, respectively. The s1 subtypes s1a and s1c were identified in 37 (32%) and 79 (68%) strains, respectively, whereas the s1b subtype was not detected. Eighteen strains associated with chronic gastritis (47%) were grouped into the s1a subtype, which was more than the number of strains associated with gastric cancer (eight strains, 21%) grouped into this subtype. In contrast, 31 (79%) strains associated with gastric cancer were grouped into the s1c subtype, which was significantly (p = 0.017) higher than the number (20 strains, 53%) of strains associated with chronic gastritis grouped into this subtype. No significant differences were found when vacuolating toxin activity was measured, although the average value for the gastric cancer-associated strains was higher than that of those associated with chronic gastritis or peptic ulcer (Fig. 2 and Table 2). There was no significant difference in vacuolating toxin activity between the s1a and s1c subtypes. However, 33% of gastric cancer strains were classified into the extremely strong group, which was significantly (p = 0.026) higher than that of chronic gastritis strains or peptic ulcer strains when toxin activity was classified into the following four groups: extremely strong (> 41, more than the average value plus 1 SD); strong (41–21.8, from less than the extremely strong to the average); weak (21.7–2.6, from the average value to the average minus 1 SD); and extremely weak (< 2.6, less than the value of the average minus 1 SD) (Table 3).

Table 2.

vacA genotypes and vacuolating toxin activity of H. pylori isolates recovered from patients with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, or gastric cancer.

| vacA genotypes and Vac activity | Total (n=116) | Chronic gastritis (n=38) | Peptic ulcer (n=39) | Gastric cancer (n=39) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1 | 116(100%) | 38(100%) | 39(100%) | 39(100%) |

| s1a | 37 (32%) | 18 (47%) | 11 (28%) | 8 (21%) |

| s1b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| s1c | 79 (68%) | 20 (53%) | 28 (72%)a | 31 (79%) b |

| s2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| m1 | 109 (94%) | 36 (95%) | 37 (95%) | 36 (92%) |

| m2 | 7 (6%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 3 (8%) |

| i1 | 110 (95%) | 35 (89%) | 38 (97%) | 37 (95%) |

| i2 | 3 (2.5%) | 1 (3%) | 0 | 2 (5%) |

| i1,i2(-) | 3 (2.5%) | 2 (5%) | 1 (3%) | 0 |

| Vacuolating toxin activity | 21.8±19.2 | 20.3±17.2 | 18.7±18.0 | 26.3±21.2 |

ap = 0.103 and bp = 0.017 compared with that in chronic gastritis with Fisher’s exact test.

Fig. 2. Vacuolating toxic effects of H. pylori culture broth on RK-13 cells.

The RK-13 cells showed vacuolation after 12 h of coculture with a two-fold diluted culture medium of each H. pylori strain. Arrows indicate well-characterized vacuolation. A, extremely strong; B, strong; C, moderate; D, weak; E, non-toxic effect control.

Table 3.

Vacuolating toxin activity of H. pylori isolates recovered from patients with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, or gastric cancer.

| Symptoms | No | Vacuolating toxin activity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Extremely Strong (>41) | Strong (41~21.8) | Moderate (21.8~2.6) | Weak (<2.6) | ||

| Chronic gastritis | 38 | 5 (13%) | 8 (21%) | 20 (53%) | 5 (13%) |

| Peptic ulcer | 39 | 4 (10%) | 7 (18%) | 19 (49%) | 9 (23%) |

| Gastric cancer | 39 | 13 (33%)a | 6 (15%) | 17 (44%) | 3 (8%) |

| Total | 116 | 22 (19%) | 21 (18%) | 56 (48%) | 17 (15%) |

Parentheses indicate percentage of each group classified by vacuolating cytotoxin activity.

ap = 0.026 compared with groups of chronic gastritis or peptic ulcer using Fisher’s exact test.

Genotypes of cagA

The cagA gene was found in almost all strains, with the exception of two strains isolated from patients with chronic gastritis. Polymorphisms in the 3'-region of cagA were analyzed by PCR and nucleotide sequencing. Five kinds of repeat patterns of EPIYA were identified in cagA-positive H. pylori isolates, and most H. pylori isolates grouped into the EPIYA-ABD pattern, which has been frequently isolated in Asia. Four patterns of variant EPIYA-ABDs were found in six strains by PCR and nucleotide sequencing (Table 4). There was no EPIYA motif in the EPIYA-B segment or deletion of amino acid residues in the downstream region of EPIYA-A and/or -D segments. Multiple EPIYA-AB motifs were found in one chronic gastritis strain and one gastric cancer strain. Multiple EPIYA-D segments (EPIYA-ABD′bD and A′bD′bD) were present in one peptic ulcer strain and in three gastric cancer strains.

Table 4.

Repeat patterns of EPIYA in the 3'-region of cagA of H. pylori isolates recovered from patients with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, or gastric cancer.

| CagA EPIYA types a | Chronic gastritis (n=38) | Peptic ulcer (n=39) | Gastric cancer (n=39) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABD or A′bD | 35 (92.0%) | 38 (97.4%) | 35 (89.7%) |

| ABD′bD or A′bD′bD | 0 | 1 (2.6%) | 3 (7.7%) |

| ABABD | 1 (2.7%) | 0 | 1 (2.6%) |

| CagA negative | 2 (5.3%) | 0 | 0 |

a, A, B, and D indicate typical EPIYA segment, b notes the EPIYA-B segment deleted in the 5’-end region including EPIYA motif, and A′ and D′ indicate the segment deleted in the downstream region of EPIYA motif. ABD segments produced DNA fragments of 293~299 bp with cagA EPIYA FR primers and 222 bp with EPIYA JSR primers. When amplified DNAs of different sizes were produced, amplified DNAs were subjected to nucleotide sequence analysis.

Genotypes of Adhesion Genes

The genotypes of the adhesion genes alpA, alpB, babA1, babA2, hopZ, oipA, and sabA were examined by PCR. Among the 116 strains, alpA, alpB, babA2, hopZ, oipA, and sabA were detected in 88 (76%), 113 (97%), 91 (79%), 96 (83%), 112 (97%), and 70 (60%) strains, respectively (Table 5). The prevalence of alpA in peptic ulcer strains (82%) and gastric cancer strains (87%) was significantly (p = 0.026 and 0.005, respectively) higher than that in chronic gastritis strains (58%), and the prevalence of babA2 in peptic ulcer (95%) or gastric cancer strains (95%) was also significantly (p = 0.000) higher than that in chronic gastritis strains (45%). The prevalence of hopZ was significantly (p = 0.036) higher in the gastric cancer strain (92%) than that in the chronic gastritis strains (73%). The prevalence of alpB, oipA, and sabA did not differ significantly among the three clinical entities of gastric diseases (Table 5).

Table 5.

Genotypes of adhesion proteins of H. pylori isolates recovered from patients with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, or gastric cancer.

| Genotypes | Total (n=116) | Chronic gastritis (n=38) | Peptic ulcer (n=39) | Gastric cancer (n=39) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alpA | 88 (76%) | 22 (58%) | 32 (82%) a | 34 (87%) b |

| alpB | 113 (97%) | 35 (92%) | 39 (100%) | 39 (100%) |

| babA2 | 91 (79%) | 17 (45%) | 37 (95%) c | 37 (95%) d |

| hopZ | 96 (83%) | 28 (73%) | 32 (82%) | 36 (92%)e |

| oipA | 112 (97%) | 35 (92%) | 38 (97%) | 39 (100%) |

| sabA | 70 (60%) | 25 (66%) | 23 (59%) | 22 (56%) |

ap = 0.026, bp = 0.005, cp = 0.000, dp = 0.000, and ep = 0.036 compared with those with chronic gastritis using Fisher’s exact test.

Genotypes of Genes in the Endonuclease Restriction/Modification Systems

Genes in the endonuclease restriction/modification systems were used for genotyping H. pylori isolates, including hrgA, hypIII, and iceA. Among the 116 strains, hrgA, hypIIIR, and hypIIIM were detected in 49 (35%), 79 (69%), and 116 (100%) strains, respectively. The iceA1 and iceA2 genotypes were found in 98 (84%) and 15 (13%) strains, respectively. The prevalence of hrgA in chronic gastritis (44%) strains was higher than that in peptic ulcer (21%) or gastric cancer (33%), although there was no significant difference among the three groups. The prevalence of hypIII and iceA was not significantly associated with clinical outcomes (Table 6).

Table 6.

Genotypes of endonuclease enzyme genes of H. pylori isolates recovered from patients with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, or gastric cancer.

| Genes | Total (n = 116) | Chronic gastritis (n = 38) | Peptic ulcer (n = 39) | Gastric cancer (n = 39) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hrgA | 36 (35%) | 16 (44%) | 8 (21%) | 12 (30%) |

| hypⅢR | 80 (70%) | 22 (56%) | 30 (77%) | 27 (70%) |

| hypⅢM | 116 (100%) | 38 (100%) | 39 (100%) | 39 (100%) |

| iceA1 | 98 (84%) | 30 (78%) | 34 (87%) | 33 (85%) |

| iceA1Δ94 | 2 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| iceA2 | 15 (13%) | 6 (16%) | 4 (10%) | 5 (13%) |

Genotypes of dupA Genes in CagPAI

Genotyping of dupA genes was performed by PCR-based identification of jhp0917 and jhp0918; dupA was detected in 28 (24%) strains while jhp0918 was found in 2 (2%) strains. The prevalence of dupA in peptic ulcer strains (26%) and gastric cancer strains (28%) was higher than that in chronic gastritis strains (18%), although this lacked statistical significance (Table 7).

Table 7.

Genotypes of dupA in CagPAI of H. pylori isolates recovered from patients with chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, or gastric cancer.

| Genes | Total (n = 116) | Chronic gastritis (n = 38) | Peptic ulcer (n = 39) | Gastric cancer (n = 39) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| jhp0918 | 2 (2%) | 2 (5%) | 0 | 0 |

| jhp0917–0918 | 28 (25%) | 7 (18%) | 10 (26%) | 11 (28%) |

Contribution of Genotyping Factors and Vacuolating Toxicity to the Development of Severe Gastric Symptoms

Among the bacterial factors analyzed in this study, the prevalence of genotypes vacAs1c, alpA, babA2, and hopZ and the extremely strong vacuolating toxicity showed significant differences between strains associated with chronic gastritis strains and those associated with severe symptoms (peptic ulcer and gastric cancer). The presence of the babA2 genotype contributed the most to the development of peptic ulcer (OR: 27.5; 95% CI: 5.0–151.2; p = 0.000) and gastric cancer (OR: 21.7; 95% CI: 4.4–106.3; p = 0.000) (Table 8). The presence of alpA also contributed to the development of peptic ulcer (OR: 7.0; 95% CI: 2.0–24.9; p = 0.026) and gastric cancer (OR: 4.5; 95% CI: 1.2–17.6; p = 0.005). Genotypes of vacAs1c and hopZ also showed significant associations with the development of gastric cancer. Extremely strong vacuolating toxicity was significantly associated with the development of gastric cancer compared with that of chronic gastritis (OR: 3.5; 95% CI: 1.1–11.2; p = 0.009)(Table 8).

Table 8.

Analysis of the contributory role of genotyping factors and vacuolating toxicity in the development of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer.

| vacAs1c | alpA | babA2 | hopZ | Extremely strong vacuolating toxin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Peptic ulcer | Gastric cancer | Peptic ulcer | Gastric cancer | Peptic ulcer | Gastric cancer | Peptic ulcer | Gastric cancer | Peptic ulcer | Gastric cancer | |

| OR | 1.7 | 3.2 | 7.0 | 4.5 | 27.5 | 21.7 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 1.4 | 3.5 |

| 95% CI | 0.60–5.2 | 1.1–9.8 | 2.0–24.9 | 1.2–17.6 | 5.0–151.2 | 4.4–106.3 | 0.7–8.8 | 0.6–18.2 | 0.3–6.0 | 1.1–11.2 |

| p value | 0.103 | 0.017 | 0.026 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.421 | 0.036 | 0.702 | 0.009 |

Combination of Genotypes Predicting the Development of Peptic Ulcer and Gastric Cancer

A total of 11 combinations generated by double, triple, and quadruple genotypes of vacAs1c, alpA, babA2, and hopZ were significantly associated with the development of severe symptoms (Table 9). Among these combinations, babA2/hopZ was present at the highest proportion (82.1%) in severe symptom strains, followed by alpA/babA2 (79.5%), alpA/hopZ (75.6%), vacAs1c/babA2 (71.8%), and alpA/babA2/hopZ (70.5%). The combination of vacAs1c/alpA/babA2 was the most predictable determinant for the development of severe symptoms (OR: 15.8; 95% CI: 4.6–53.8; p = 0.000), followed by vacAs1c/alpA/babA2/hopZ (OR: 11.6; 95% CI: 3.4–39.6; p = 0.000), alpA/babA2 (OR: 10.9; 95% CI: 3.9–30.5; p = 0.000), vacAs1c/babA2 (OR: 8.4; 95% CI: 3.0–23.6; p = 0.000), and vacAs1c/babA2/hopZ (OR: 8.6; 95% CI: 3.0–25.0; p = 0.000).

Table 9.

The multiple correspondence analysis of the genotypes vacAs1c, alpA, babA2, and hopZ with gastric symptoms.

| Combinations of genotypes | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Genotypes | Double | Triple | Quadruple | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| vacAs1c | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| alpA | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| babA2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| hopZ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

| No. (%) in 38 chronic gastritis strains | 10 (26.3) | 8 (21.1) | 15 (39.5) | 11 (29.0) | 18 (47.4) | 13 (34.2) | 4 (10.5) | 6 (15.8) | 8 (21.1) | 10 (26.3) | 4 (10.5) |

|

|

|

||||||||||

| No. (%) in of 78 severe symptoms strains | 52 (66.7) | 56 (71.8) | 52 (66.7) | 62 (79.5) | 59 (75.6) | 64 (82.1) | 49 (62.8) | 49 (62.8) | 46 (59.0) | 55 (70.5) | 43 (55.1) |

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Odds ratio | 7.0 | 8.4 | 3.3 | 10.9 | 4.0 | 8.9 | 15.8 | 8.6 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 11.6 |

| 95% CI | 2.7–18.01 | 3.0–23.6 | 1.4–8.0 | 3.9–30.5 | 1.5–10.6 | 3.4–23.2 | 4.6–53.8 | 3.0–25.0 | 2.4–17.1 | 2.8–19.3 | 3.4–39.6 |

| p value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Among the four genotype markers, the OR average of double and triple combination groups containing babA2 showed the highest value when compared with combinations containing other genotype markers, demonstrating that babA2 might be the most critical determinant in the development of severe symptoms of gastric diseases (Tables 8 and 9).

Discussion

Toxigenic strains of H. pylori carrying cagA and vacA are known to be closely associated with the development of gastric diseases such as peptic ulcer and gastric cancer [2, 10, 11, 14, 15]. Notably, although infections of H. pylori bearing cagA and vacA cause chronic gastritis in many cases, they are not always associated with peptic ulcer or gastric cancer [3]. Only approximately 10–15% of infected individuals were reported to develop peptic ulcer, gastric carcinoma, and MALT lymphoma [6, 19]. In Korea, most people are infected early in life with toxigenic H. pylori strains bearing cagA and vacA [20-22], but only a small proportion of these individuals have complained of severe gastric maladies [21-23]. These studies suggest that, along with cagA and vacA, other virulence factors of H. pylori are involved in disease outcomes.

A variety of candidate virulence factors have been identified for their role in provoking gastric pathogenesis. Unfortunately, their relevance to severe gastric disorders has proved epidemiologically controversial [3]. The reported discrepancies in the relationship between virulence factors and disease outcomes may be due to differences in prevalence rates and the types of cagA and vacA virulence factors present in different regions [3,5,26-28,41,42]. In contrast, most Korean H. pylori isolates contain cagA and vacA, thereby simplifying the analysis of the influence of other virulence factors and the understanding of their roles in the development of severe gastric symptoms. The risk prediction of severe gastric symptoms according to virulence factors is critical in the management and treatment of H. pylori infections. Therefore, in this study we investigated the relevance of virulence factors to clinical symptoms and sought to establish risk rates for the development of gastric diseases caused by H. pylori infections based on previously identified virulence factors.

Difference in vacuolating ability of H. pylori is conferred by vacA type variations in the signal sequence (s1a, s1b, s1c, and s2), mid-region (m1 and m2), and intermediate region (i1, i2, and i3). Recently, a deletion-region (d1 and d2) and c-region (c1 and c2) have also been identified [3, 43]. Genotypes and subtypes of vacA in H. pylori strains have been reported to be geographically distributed. H. pylori strains in Northeast Asia have been predominantly grouped into the s1, m1, and i1 types based on the vacA signal sequence, middle, and intermediate regions, respectively [16, 34]. Consistent with the results of previous studies [16, 34], most strains in this study were grouped as s1/m1/i1, irrespective of gastric symptoms, with a third of strains being classified as s1a subtype and two-thirds of strains being classified as s1c subtypes. Several studies have reported that subtypes s1a and m1 are associated with peptic ulcer, intestinal metaplasia, or gastric cancer [15, 44, 45]. However, the proportion of s1c subtype was significantly higher in the gastric cancer group in this study (Table 2). The proportion of s1c was > 2.5-fold higher in peptic ulcer strains (72%) and > 3.5-fold higher in gastric cancer strains (79%) than those (28% in peptic ulcer strains and 21% in gastric cancer strains) of s1a, demonstrating that the s1c subtype may increase the risk of severe symptoms. Since all H. pylori strains carry different actual vacuolating abilities [3], the risk rates based on the expressed toxicity were analyzed. Values for the vacuolating cytotoxin activities of all 116 strains were widely distributed from 0 to 191 with no significant difference among gastric symptoms (Table 2). However, when vacuolating toxin activities were divided into four levels as shown in Table 3, gastric cancer strains were noticeably more classified into the extremely strong group than strains in other symptom groups (p < 0.05). This result might reflect the extent to which vacuolating toxin activity has a critical role in the development of gastric cancer.

The vacAs1/i1/m1 gene is closely associated with cagA [3, 46], and therefore the repeat pattern of EPIYA of cagA in all 116 isolates was also investigated. Most East Asian H. pylori strains carry the cagA gene that encodes CagA proteins of the EPIYA-ABD type (Asian type CagA), irrespective of gastric symptoms [3, 21, 41]. Our results are consistent with these previous studies that demonstrated a low-level association of cagA with gastric cancer and peptic ulcer in Asian strains [6, 21]. In this study, since most isolates were found to be EPIYA-ABD type, the difference in risk rate between EPIYA type and multi-EPIYA type could not be identified.

The gastric mucus moves rapidly outward and H. pylori has to overcome the shedding flow of mucus by using bacterial factors to attach to the epithelium of the gastric mucosa. Therefore, H. pylori adherent factors play important roles in the initial colonization, long-term persistence, and gastric pathogenesis [47]. Several H. pylori adhesins belonging to the H. pylori outer membrane prion (HOP) subfamily, including BabA (HopS), SabA (HopP), AlpA (HopC), AlpB (HopB), HopZ, and OipA (HopH), have been extensively analyzed to understand bacterial interaction with the epithelial surface of the gastric mucosa [32].

In this study, the presence of alpA, babA2, and hopZ in H. pylori strains with severe gastric symptoms was significantly higher than that in chronic gastritis strains (Table 5). alpA is known as a virulence factor involved in signal transduction of host epithelial cells during H. pylori infection [4, 48]. Previous studies also demonstrated that an H. pylori ΔalpA/B mutant poorly colonized the stomachs of guinea pigs, mice, and Mongolian gerbils, indicating that AlpA and AlpB play an important role in bacterial colonization [24, 25, 48]. AlpA and AlpB have not yet been clearly identified as a virulence factor in humans and their role remains controversial [4]; however, in this study, we confirmed that the presence of alpA was significantly correlated with the development of gastric cancer in H. pylori infection (Table 5, p < 0.05).

Previous studies showed that the presence of the babA2 gene substantially increased the risk of peptic ulcer development [28, 49]. In addition, a genome-wide association study on European H. pylori isolates demonstrated that, compared with isolates from gastritis patients, the gastric cancer phenotype was associated with the babA2 gene [42]. Conversely, a meta-analysis study reported a lack of significant correlation in Asian populations [49]. This controversial result of the Asian type is probably due to the high overall prevalence of the babA2 gene and significant heterogeneity in Asian isolates [3]. Limiting factors, such as the distinct genotypic profile of Western/Asian isolates and poor correlation between the presence of babA2 gene and actual expression of BabA2 protein also hamper demonstrating the risk of the babA2 gene on disease outcome [28, 50]. Although there is still controversy as to whether the babA2 gene is related to the development of severe gastric symptoms, we observed the presence of the babA2 gene with high frequency in patients with peptic ulcer and gastric cancer in this study (Table 5, p < 0.05).

hopZ was found to be regulated at the transcriptional level according to pH change [51], and hopZ expression depends on an on/off switch during early bacterial colonization [29]. These results indicate that hopZ has a strong selectivity in vivo, plays an important role in adaptation to the host environment [52], and has an essential role in colonization of the gastric mucosa during early infection [29]. Nevertheless, it is unclear whether hopZ is related to other virulence factors or is linked to other clinical diseases [29, 53]. However, we confirmed that the presence of the hopZ gene had a significant correlation with the disease outcome of gastric cancer (Table 5, p < 0.05).

Unlike alpA, babA2, and hopZ, the difference in gene prevalence of alpB, opiA, and sabA was difficult to determine according to the clinical outcomes. alpB has high homogeneity with alpA and is known to play a similar important role in adhering to gastric tissues and colonization [24, 25, 48]. In this study, most isolates from each clinical symptom group were found to have alpB (97%), and therefore alpB may not be a useful marker for predicting the clinical outcome of H. pylori infection. Previous studies reported that oipA is closely linked to the expression of cagA [31, 54], which was also confirmed in this study with only 2 out of 112 oipA(+) strains being cagA(-) strains. Yamaoka Y. et al. reported that oipA can be functionally turned “on” or “off ” by a slipped strand mispairing mechanism [6]. Several studies of prevalence and meta-analysis demonstrated that the oipA “on” function increased the risk of development of peptic ulcer and gastric cancer [55]. Conversely, an induced oipA “on” status is reported to have no relation to the risk of severe gastric symptoms [27, 54, 56]. This study focused on discovering virulence factors of H. pylori that could be detected by PCR and then used as markers of development of gastric symptoms, which would be more useful in clinical approaches than sequencing to identify the functional status of oipA. This limitation made it more difficult to find any link between oipA prevalence and disease outcome in this study. Moreover, oipA does not appear to be a useful marker for predicting the clinical outcome of H. pylori infection because most H. pylori isolates in Korea were identified as virulent strains [56].

sabA is known to be associated with chronic infection establishment of H. pylori [57]. The proportion of the sabA gene was slightly higher in chronic gastritis strains than in others, although this lacked statistical significance (Table 5). A survey in Japan reported that sabA was linked to gastric cancer [58]. However, although severe neutrophil infiltration and epithelial atrophy are associated with sabA, there are reports that sabA does not affect clinical outcome, and therefore the relationship between sabA and clinical diseases remains controversial [58, 59].

Alleles of restriction and modification systems, including iceA and hrgA, are reportedly predictive of gastric symptoms in East Asia [14, 33, 60]. However, the relationship between H. pylori iceA/hrgA and clinical outcomes is still controversial [5, 13, 61]. There are two main allelic variants, iceA1 and iceA2, of which iceA1 is reported to be predominant in East Asia [62]. Several studies have suggested that iceA1 is frequently found in strains isolated from patients with peptic ulcer and gastric cancer [33, 60, 62], whereas others have shown different findings [16, 63], even though iceA1 is presumed to facilitate neutrophil filtration and inflammation [62, 64]. In this study, the prevalence of iceA1 was higher in peptic ulcer- and gastric cancer-associated strains in comparison with that of iceA2, and significant discrepancies were not found. H. pylori has a highly heterogeneous and variable type II R-M system, whereas the hypIII R-M system contains two genes, hypIIIR and hypIIIM [12]. The hrgA gene, which is considered an important virulence determinant in H. pylori-associated gastric diseases, can replace hypIIIR [14]. Therefore, the correlation between hrgA/hypIIIR status and clinical outcome has been used to determine H. pylori toxicity [14]. Subgroup analysis of possible correlations between clinical outcome and hrgA/hpyIIIR status suggested that the prevalence of the hrgA gene was increased among gastric cancer patients (42%) in East Asian countries compared with that in patients without gastric cancer (17%) [14]. In contrast, another study reported that hrgA/hypIIIR status and iceA genotypes are not related to gastric outcomes, although regional differences in the prevalence between Asia and the West were observed [61]. In addition, these authors suggested that the prevalence of the hrgA gene was not related to other putative virulence factors, such as cagA, vacA, or iceA, in either East Asia or Western countries [61]. In this study, the prevalence of hrgA gene was higher, though not significantly, in chronic gastritis strains than in other strains, showing different results from the previous study. Thus, the results of studies on hrgA are contradictory. This may be because hrgA prevalence was not related to other putative virulence factors (cagA, vacA, or iceA), which play an important role in the development of pestilent gastric disease caused by H. pylori infection [22, 61].

Members of the pathogenic island region (CagPAI) of H. pylori containing the type IV secretion system have been proposed as playing a role in the pathogenesis of gastric diseases [12, 19]. dupA is a component gene of the type IV secretion system, which encompasses both jhp0917 and jhp0918. dupA is the first identified disease-specific H. pylori virulence factor that induces duodenal ulcer and has a suppressive action on gastric cancer [22]. Despite the reported gastric cancer inhibitory function, a pooled analysis of data from three Western countries (the USA, Belgium, and South Africa) linked the presence of the dupA gene to peptic ulcer and gastric cancer [65]. In addition, although there is a large regional difference in prevalence of the dupA gene, this may be a risk factor for gastric cancer along with duodenal ulcer [66]. However, a meta-analysis using 11–12 studies on dupA (9 countries) reported that dupA had no correlation with the development of peptic ulcer and gastric cancer [67]. Other studies also reported no correlation between dupA and gastric disease outcome, and this association remains controversial [68, 69]. In this study, the prevalence of dupA (jhp0917) was higher, but not significantly, in peptic ulcer- and gastric cancer-associated strains than that in chronic gastritis-associated strains. The dupA gene may be mutated and protein expression may be inhibited. Therefore, a study based on DupA protein expression should be considered to accurately analyze the correlation between dupA expression and clinical outcome [6].

Prediction of the severe gastric disease outcome of H. pylori using one virulence factor is difficult. Many virulence factors have been correlated with each other. The oipA “on” status has been found to be associated with cagA and vacA [27, 30], and other major virulence factors have also been reported to be correlated [3]. Therefore, severe symptoms may originate from the complex results of several linked virulence factors, rather than the function of a single factor [3, 52, 53, 57]. Multiple correspondence analysis has been shown to serve as a better approach for the prediction of peptic ulcer, gastric cancer, and MALT lymphoma [26, 57]. Therefore, this study was conducted using the four identified virulence factors, vacAs1c, alpA, babA2, and hopZ, that showed significant discrepancies in their prevalence between chronic gastritis strains and severe symptoms, to investigate whether clinical outcome could be predicted with each combination. Eleven combinations of genotypes using the four virulence factors were generated (Table 9), all of which showed an OR value of 3.3 or higher (p < 0.001). These results confirmed that all four factors could affect gastric symptoms and be used as markers for disease outcome. Among the combinations, the triple genotype vacAs1c/alpA/babA2 was the most predictable for the development of severe symptoms (OD: 15.8). The average OR of double and triple combination groups containing babA2 was significantly higher than that of the other groups. Taken together, these data suggest that the genotype factor babA2 might contribute more to the development of severe gastric symptoms than others.

Various other factors, as well as genotype factors, play an important role in the development of severe clinical symptoms, including age, sex, genetic characteristics, diet conditions, and underlying diseases [3, 54]. The link between gene presence and functional protein expression must also be considered [28]. In addition, the possibility of complex H. pylori infections in which different genotype combinations coexist cannot be ruled out [70]. In this case, only one strain of H. pylori was isolated from each patient, making it difficult to analyze the correlation between virulence factors and disease outcome. The large regional differences in the prevalence of virulence factors also impose limitations, causing bias in the analysis results. In this study, 116 strains of H. pylori isolates from patients with no significant age difference were analyzed (Fig. 1): all strains were vacAs1 genopositive while 114 strains were cagA genopositive. The OR value for the development of gastric symptoms and the statistical significance in the relevance of genotype factors to gastric symptoms were calculated by the adjustment of sex using the Mantel-Haenszel method [71] to overcome gender imbalance. However, other limiting factors in this study remain a challenge.

This study attempted to identify candidate virulence factors of H. pylori that can predict severe gastric symptoms via PCR screening. Since this study analyzed H. pylori isolated over a limited period of time, it could not provide information on the current prevalence of the virulence factors. However, we found that the presence of vacAs1c, alpA, babA2, and hopZ genes could increase the risk of disease outcome in infections with toxigenic H. pylori that also harbor the cagA and vacA genes. Moreover, we confirmed that severe gastric symptoms could be predicted at a high level of possibility through multiple correspondence analysis using a combination of these four genes. This could improve our understanding of the role of these virulence factors of H. pylori, which will assist in early prediction of disease outcome through the simple PCR method and thereby enable appropriate treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the fund of a research promotion program, Gyeongsang National University, 2017, by the grant (0820050) of the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, and by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants (2017R1C1B5076887 and 2019R1I1A3A01059312) funded by the Korean government (MSIT).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joo JS, Park KC, Song JY, Kim DH, Lee KJ, Kwon YC, et al. A thin‐layer liquid culture technique for the growth of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2010;15:295–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaser MJ, Atherton JC. Helicobacter pylori persistence: biology and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2004;113:321–333. doi: 10.1172/JCI20925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Šterbenc A, Jarc E, Poljak M, Homan M. Helicobacter pylori virulence genes. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4870–4884. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i33.4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuo Y, Kido Y, Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter pylori outer membrane protein-related pathogenesis. Toxins (Basel) 2017;9:101. doi: 10.3390/toxins9030101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamaoka Y, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori virulence and cancer pathogenesis. Future Oncol. 2014;10:1487–1500. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaoka Y. Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;7:629–641. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malaty HM. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2007;21:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Youn HS, Baik SC, Cho YK, Woo HO, Ahn YO, Kim K, et al. Comparison of Helicobacter pylori infection between Fukuoka, Japan and Chinju, Korea. Helicobacter. 1998;3:9–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1998.08011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin A, Kim J, Park S. Gastric cancer epidemiology in Korea. J. Gastric Cancer. 2011;11:135–140. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2011.11.3.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int. J. Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fock KM, Ang TL. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer in Asia. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;25:479–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alm RA. Analysis of the genetic diversity of Helicobacter pylori: the tale of two genomes. J. Mol. Med. 1999;77:834–846. doi: 10.1007/s001099900067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiota S, Suzuki R, Yamaoka Y. The significance of virulence factors in Helicobacter pylori. J. Dig. Dis. 2013;14:341–349. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ando T, Wassenaar TM, Peek RM, Aras RA, Tschumi AI, van Doorn LJ, et al. A Helicobacter pylori restriction endonucleasereplacing gene, hrgA, is associated with gastric cancer in Asian strains. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2385–2389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choe YH, Kim PS, Lee DH, Kim HK, Kim YS, Shin YW, et al. Diverse vacA allelic types of Helicobacter pylori in Korea and clinical correlation. Yonsei Med. J. 2002;43:351–356. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2002.43.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaoka Y, Kodama T, Gutierrez O, Kim JG, Kashima K, Graham DY. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori iceA, cagA, and vacA status and clinical outcome: studies in four different countries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999;37:2274–2279. doi: 10.1128/JCM.37.7.2274-2279.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kao CY, Sheu BS, Wu JJ. Helicobacter pylori infection: An overview of bacterial virulence factors and pathogenesis. Biomed. J. 2016;39:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClain MS, Beckett AC, Cover TL. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin and gastric cancer. Toxins (Basel) 2017;9:316. doi: 10.3390/toxins9100316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalali B, Mejías Luque R, Javaheri A, Gerhard M. H. pylori virulence factors: influence on immune system and pathology. Mediators Inflamm. 2014:ID 426309. doi: 10.1155/2014/426309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhee KH. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. J. Korean Soc. Microbiol. 1990;25:475–490. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko JS, Kim KM, Oh YL, Seo JK. cagA, vacA, and iceA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori in Korean children. Pediatr. Int. 2008;50:628–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu H, Hsu PI, Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. Duodenal ulcer promoting gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:833–848. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim N, Park RY, Cho SI, Lim SH, Lee KH, Lee W, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and development of gastric cancer in Korea: long-term follow-up. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2008;42:448–454. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318046eac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senkovich OA, Yin J, Ekshyyan V, Conant C, Traylor J, Adegboyega P, et al. Helicobacter pylori AlpA and AlpB bind host laminin and influence gastric inflammation in gerbils. Infect. Immun. 2011;79:3106–3116. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01275-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Jonge R, Durrani Z, Rijpkema SG, Kuipers EJ, van Vliet AH, Kusters JG. Role of the Helicobacter pylori outer-membrane proteins AlpA and AlpB in colonization of the guinea pig stomach. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004;53:375–379. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerhard M, Lehn N, Neumayer N, Borén T, Rad R, Schepp W, et al. Clinical relevance of the Helicobacter pylori gene for bloodgroup antigen-binding adhesin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:12778–12783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zambon C, Navaglia F, Basso D, Rugge M, Plebani M. Helicobacter pylori babA2, cagA, and s1 vacA genes work synergistically in causing intestinal metaplasia. J. Clin. Pathol. 2003;56:287–291. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.4.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujimoto S, Ojo OO, Arnqvist A, Wu JY, Odenbreit S, Haas R, et al. Helicobacter pylori BabA expression, gastric mucosal injury, and clinical outcome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007;5:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennemann L, Brenneke B, Andres S, Engstrand L, Meyer TF, Aebischer T, et al. In vivo sequence variation in HopZ, a phasevariable outer membrane protein of Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 2012;80:4364–4373. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00977-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dossumbekova A, Prinz C, Mages J, Lang R, Kusters JG, Van Vliet AH, et al. Helicobacter pylori HopH (OipA) and bacterial pathogenicity: genetic and functional genomic analysis of hopH gene polymorphisms. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194:1346–1355. doi: 10.1086/508426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horridge DN, Begley AA, Kim J, Aravindan N, Fan K, Forsyth MH. Outer inflammatory protein a (OipA) of Helicobacter pylori is regulated by host cell contact and mediates CagA translocation and interleukin-8 response only in the presence of a functional cag pathogenicity island type IV secretion system. Pathog. Dis. 2017;75:ftx113. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftx113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odenbreit S. Adherence properties of Helicobacter pylori: impact on pathogenesis and adaptation to the host. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005;295:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peek Jr RM, Thompson SA, Donahue JP, Tham KT, Atherton JC, Blaser MJ, et al. Adherence to gastric epithelial cells induces expression of a Helicobacter pylori gene, iceA, that is associated with clinical outcome. Proc. Assoc. Am. Physicians. 1998;110:531–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim SY, Woo CW, Lee YM, Son BR, Kim JW, Chae HB, et al. Genotyping CagA, VacA subtype, IceA1, and BabA of Helicobacter pylori isolates from Korean patients, and their association with gastroduodenal diseases. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2001;16:579–584. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.5.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baik SC, Kim JB, Cho MJ, Kim YC, Park CK, Ryou HH, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among normal Korean adults. J. Korean Soc. Microbiol. 1990;25:455–462. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baik SC, Youn HS, Chung MH, Lee WK, Cho MJ, Ko GH, et al. Increased oxidative DNA damage in Helicobacter pyloriinfected human gastric mucosa. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1279–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song GY, Chang MW. Antibiotic susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori and the combination effect of antibiotics on the antibioticresistant H. pylori strains. J. Korean Soc. Microbiol. 1999;34:543–554. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monstein HJ, Nikpour Badr S, Jonasson J. Rapid molecular identification and subtyping of Helicobacter pylori by pyrosequencing of the 16S rDNA variable V1 and V3 regions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001;199:103–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor NS, Fox JG, Akopyants NS, Berg DE, Thompson N, Shames B, et al. Long-term colonization with single and multiple strains of Helicobacter pylori assessed by DNA fingerprinting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995;33:918–923. doi: 10.1128/JCM.33.4.918-923.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohta-Tada U, Takagi A, Koga Y, Kamiya S, Miwa T. Flagellin gene diversity among Helicobacter pylori strains and IL-8 secretion from gastric epithelial cells. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1997;32:455–459. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park JY, Forman D, Waskito LA, Yamaoka Y, Crabtree JE. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and CagA-positive infections and global variations in gastric cancer. Toxins (Basel) 2018;10:163. doi: 10.3390/toxins10040163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berthenet E, Yahara K, Thorell K, Pascoe B, Meric G, Mikhail JM, et al. A GWAS on Helicobacter pylori strains points to genetic variants associated with gastric cancer risk. BMC Biol. 2018;16:84. doi: 10.1186/s12915-018-0550-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soyfoo DM, Doomah YH, Xu D, Zhang C, Sang HM, Liu YY, et al. New genotypes of Helicobacter pylori VacA d-region identified from global strains. BMC Mol. Cell. Biol. 2021;22:4. doi: 10.1186/s12860-020-00338-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aydin F, Kaklikkaya N, Ozgur O, Cubukcu K, Kilic A, Tosun I, et al. Distribution of vacA alleles and cagA status of Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease and non‐ulcer dyspepsia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004;10:1102–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Höcker M, Hohenberger P. Helicobacter pylori virulence factors-one part of a big picture. Lancet. 2003;362:1231–1233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Homan M, Luzar B, Kocjan BJ, Mocilnik T, Shrestha M, Kveder M, et al. Prevalence and clinical relevance of cagA, vacA, and iceA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori isolated from Slovenian children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2009;49:289–296. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31818f09f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Posselt G, Backert S, Wessler S. The functional interplay of Helicobacter pylori factors with gastric epithelial cells induces a multi-step process in pathogenesis. Cell Commun. Signal. 2013;11:77. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu H, Wu JY, Beswick EJ, Ohno T, Odenbreit S, Haas R, et al. Functional and intracellular signaling differences associated with the Helicobacter pylori AlpAB adhesin from Western and East Asian strains. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:6242–6254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611178200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen MY, He CY, Meng X, Yuan Y. Association of Helicobacter pylori babA2 with peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4242–4251. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i26.4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Homan M, Šterbenc A, Kocjan BJ, Luzar B, Zidar N, Poljak M. Prevalence of the Helicobacter pylori babA2 gene and correlation with the degree of gastritis in infected Slovenian children. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;106:637–645. doi: 10.1007/s10482-014-0234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Merrell DS, Goodrich ML, Otto G, Tompkins LS, Falkow S. pH-regulated gene expression of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:3529–3539. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3529-3539.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu C, Soyfoo DM, Wu Y, Xu S. Virulence of Helicobacter pylori outer membrane proteins: An updated review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020;39:1821–1830. doi: 10.1007/s10096-020-03948-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Servetas SL, Kim A, Su H, Cha JH, Merrell DS. Comparative analysis of the Hom family of outer membrane proteins in isolates from two geographically distinct regions: the United States and South Korea. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12461. doi: 10.1111/hel.12461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farzi N, Yadegar A, Aghdaei HA, Yamaoka Y, Zali MR. Genetic diversity and functional analysis of oipA gene in association with other virulence factors among Helicobacter pylori isolates from Iranian patients with different gastric diseases. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018;60:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sallas ML, Dos Santos MP, Orcini WA, David ÉB, Peruquetti RL, Payão SLM, et al. Status (on/off) of oipA gene: their associations with gastritis and gastric cancer and geographic origins. Arch. Microbiol. 2019;201:93–97. doi: 10.1007/s00203-018-1580-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Torres K, Valderrama E, Sayegh M, Ramírez JL, Chiurillo MA. Study of the oipA genetic diversity and EPIYA motif patterns in cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori strains from Venezuelan patients with chronic gastritis. Microb. Pathog. 2014;76:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lehours P, Ménard A, Dupouy S, Bergey B, Richy F, Zerbib F, et al. Evaluation of the association of nine Helicobacter pylori virulence factors with strains involved in low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:880–888. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.880-888.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamaoka Y, Ojo O, Fujimoto S, Odenbreit S, Haas R, Gutierrez O, et al. Helicobacter pylori outer membrane proteins and gastroduodenal disease. Gut. 2006;55:775–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.083014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yanai A, Maeda S, Hikiba Y, Shibata W, Ohmae T, Hirata Y, et al. Clinical relevance of Helicobacter pylori sabA genotype in Japanese clinical isolates. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007;22:2228–2232. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kidd M, Peek R, Lastovica A, Israel D, Kummer A, Louw J. Analysis of iceA genotypes in South African Helicobacter pylori strains and relationship to clinically significant disease. Gut. 2001;49:629–635. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.5.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu H, Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. The Helicobacter pylori restriction endonuclease-replacing gene, hrgA, and clinical outcome: comparison of East Asia and Western countries. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2004;49:1551–1555. doi: 10.1023/B:DDAS.0000042263.18541.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yakoob J, Abbas Z, Khan R, Salim SA, Abrar A, Awan S, et al. Helicobacter pylori: correlation of the virulence marker iceA allele with clinical outcome in a high prevalence area. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2015;72:67–73. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2015.11666799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ashour AAR, Collares GB, Mendes EN, de Gusmão VrR, de Magalhães Queiroz DM, Magalhães PP, et al. iceA genotypes of Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from Brazilian children and adults. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001;39:1746–1750. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.5.1746-1750.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sgouras DN, Trang TTH, Yamaoka Y. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2015;20:8–16. doi: 10.1111/hel.12251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Argent RH, Burette A, Miendje Deyi VY, Atherton JC. The presence of dupA in Helicobacter pylori is not significantly associated with duodenal ulceration in Belgium, South Africa, China, or North America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007;45:1204–1206. doi: 10.1086/522177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hussein N. The association of dupA and Helicobacter pylori-related gastroduodenal diseases. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010;29:817–821. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0933-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shiota S, Matsunari O, Watada M, Hanada K, Yamaoka Y. Systematic review and meta-analysis: the relationship between the Helicobacter pylori dupA gene and clinical outcomes. Gut Pathog. 2010;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pacheco A, Proença-Módena J, Sales A, Fukuhara Y, Da Silveira W, Pimenta-Módena J, et al. Involvement of the Helicobacter pylori plasticity region and cag pathogenicity island genes in the development of gastroduodenal diseases. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008;27:1053–1059. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0549-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nguyen L, Uchida T, Tsukamoto Y, Kuroda A, Okimoto T, Kodama M, et al. Helicobacter pylori dupA gene is not associated with clinical outcomes in the Japanese population. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010;16:1264–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim JW, Kim JG, Chae SL, Cha YJ, Park SM. High prevalence of multiple strain colonization of Helicobacter pylori in Korean patients: DNA diversity among clinical isolates from the gastric corpus, antrum and duodenum. Korean. J. Intern. Med. 2004;19:1–9. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2004.19.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.dos Santos Silva I. Cancer epidemiology: principles and methods. Renouf Pub Co Ltd; Lyon, France: 1999. pp. 305–331. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamaoka Y, El-Zimaity HMT, Gutierrez O, Figura N, Kim JK, Kodama T, et al. Relationship between the cagA3 repeat region of Helicobacter pylori, gastric histology, and susceptibility to low pH. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:342–349. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Atherton JC, Cao P, Peek RM, Tummuru MKR, Blaser MJ, Cover TL. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori: association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:17771–17777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rhead JL, Letley DP, Mohammadi M, Hussein N, Mohagheghi MA, Hosseini ME, et al. A new Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin determinant, the intermediate region, is associated with gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:926–936. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rokbi B, Seguin D, Guy B, Mazarin V, Vidor E, Mion F, et al. Assessment of Helicobacter pylori gene expression within mouse and human gastric mucosae by real-time reverse transcriptase PCR. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:4759–4766. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.4759-4766.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamaoka Y, Kwon DH, Graham DY. A Mr 34,000 proinflammatory outer membrane protein (oipA) of Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7533–7538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130079797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peck B, Ortkamp M, Diehl KD, Hundt E, Knapp B. Conservation, localization and expression of HopZ, a protein involved in adhesion of Helicobacter pylori. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3325–3333. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.16.3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.De Jonge R, Pot RGJ, Loffeld RJLF, Van Vliet AHM, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG. The functional status of the Helicobacter pylori sabB adhesin gene as a putative marker for disease outcome. Helicobacter. 2004;9:158–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mukhopadhyay AK, Kersulyte D, Jeong JY, Datta S, Ito Y, Chowdhury A, et al. Distinctiveness of genotypes of Helicobacter pylori in Calcutta, India. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:3219–3227. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.11.3219-3227.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ando T, Wassenaar TM, Peek RM, Aras RA, Tschumi AI, van Doorn L-J, et al. A Helicobacter pylori restriction endonucleasereplacing gene, hrgA, is associated with gastric cancer in Asian strains. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2385–2389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]