Abstract

The aim of this research is to examine the trend of water use efficiency (WUE) and the spillover effect of its determinants in 28 sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries over the period 2007 to 2018 using the directional distance function (DDF) and the spatial Durbin model. Results of the DDF revealed that the most efficient countries include Botswana, and Liberia whereas countries with poor performance include Niger and South Africa. Also, the average efficiency scores over the study period improved steadily from 0.582 in 2007 to 0.698 in 2018. The study showed that under economic distance weight in the spatial Durbin model, the values of the spatial lag coefficients of urbanisation (URB), export (EX), and education (EDU) depict positive and statistically significant effects on WUE, while industrial activities (IND), foreign direct investment (FDI), and government interference (COR) had an adverse influence on WUE in SSA. Results of the spatial decomposition effect of URB demonstrated a major impact on WUE in both the local and adjacent countries. However, a significant decline of WUE through the direct and indirect impacts of FDI, EX, and COR in the local and neighboring countries was recorded which indicate the presence of a negative spatial dependency on WUE in SSA. The outcome of this study implies that policymakers in SSA countries must strengthen sustainable water resources management decisions with neighbouring countries to achieve sustainable development goal 6 by 2030 and beyond.

Keywords: Directional distance function, Moran's index, Spatial effects, Spatial panel approaches, sub-Saharan Africa, Water use efficiency

Directional distance function; Moran's index; Spatial effects; Spatial panel approaches; sub-Saharan Africa; Water use efficiency.

1. Introduction

Water is a widely treasured and irreplaceable natural resource for human existence and well-being. However, Africa is challenged with water problems such as water scarcity, limited water supplies, increased use of water, and ineffective water regulation. In countries like Kenya, Malawi, and South Africa among others, water resource shortages, and corruption in the water sector are the major problems restricting water sustainability (Muller, 2020). Additionally, several water ecology issues such as poor water quality, loss of biodiversity, and algae growth are present throughout Africa. According to the World Development Indicators (WDI 2020), sub-Saharan Africa's per capita freshwater resource was only 3602 m3 as of 2018 and even the allocation of these scarce water resources is uneven as countries in the northern parts suffer prolonged inadequate access to water than countries in the south (Sun et al., 2021). Given the enormous difficulties associated with Africa's water resources, promoting the sustainable use of water resources ought to be a major focus of current reform and study. This is because efficient systems of water resources could support societal goals both now and in the future whilst still preserving the hydrological, and ecological integrity (Russo et al., 2014). Hence, Addae et al. (2022) mentioned that it is essential to look at water use efficiency as a key strategy for ensuring water sustainability.

Originally, water efficiency was described as the economic value of goods generated per unit of water consumed, indicating how effectively an economic output affects the aquatic environment (Marlow 1999). Data envelopment analysis (DEA) is a traditional technique frequently used for calculating the effectiveness of decision-making units (DMUs). Data envelopment analysis (DEA) was initially introduced by Charnes et al. (1978) as a non-parametric system that does not involve any restrictive assumptions of the related function among several dependent and independent variables. Additionally, it is not essential to acquire pricing data of input and output attributes, making appraisal convenient and the efficiency assessment process more factual (Addae et al., 2022). (Hu et al., 2006) were the first to use traditional radial DEA to assess regional total factor WUE in China, and the WUE framework has so far been applied to WUE research in several nations and locations (Addae et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2019). Generally, in the conventional water use efficiency framework, labour, water, and capital are used as input factors and economic growth is the output factor representing the substitution of different input factors in the production process ignoring undesirable output.

DEA has been extensively used to analyze WUE. Notwithstanding its effectiveness, DEA is a nonparametric method that does not account for statistical disturbances and could result in highly susceptible data quality and possibly lead to skewed efficiency estimations (Zhou et al., 2019). Moreover, DEA is unable to directly assess the elements that affect efficiency, nor the spatial effect of these determinants on neighbouring areas’ water use efficiency. Therefore, researchers have to adopt a one-stage method like the stochastic frontier analysis (Zheng et al., 2018) or a two-stage method like the DEA-Tobit model to study WUE and its determinants (Wang et al., 2018). Given the shortfalls of DEA, previous researchers have adopted the directional distance function (DDF) to determine the direction of efficiency of different economies because it takes into consideration the variance of the indicators, thereby reducing errors in estimation.

As a typical nonradial approach, the DDF can assess performance when the production function generates both desired and unwanted results. The non-radial DDF is an approach that Färe et al. (2005) proposed, and it has been used extensively by several scholars (Ma et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2019) in the fields of business, environmental, and energy efficiency evaluation. For instance, Wang and Choi (2019) employed the global nonradial DDF to investigate the challenges of urban-industry activities on sustainable water use in Korea. Using the non-radial DDF, Zhou et al. (2019) measured the environmental efficiency of China's industrial water consumption from 2011 to 2015. In the same vein, Zhang et al. (2021) used the DDF's dynamic two-stage recycling model to measure urban WUE and the spatial migration path of 30 provinces in China. However, despite the DDF's strengths, it cannot analyse the possible influencing factors of water use efficiency amid several geographical units. According to Li and Ma (2015), recent studies do not often take into consideration the spillover effects of WUE, but it is essential to note that the efficient use of water resources in a specific spatial unit may be influenced by environmental, and socioeconomic indicators of a country's adjoining spatial units. Therefore, spatial econometric analysis is utilized in this study to that effect.

The spatial spillover effect of WUE assumes that improving a country's efficiency will benefit nearby countries (Sun et al., 2021). A sustained WUE and socioeconomic growth in SSA might be attained by the spatial spillover effect, which could also reduce the unbalanced geographic variation of overall WUE caused by related geographic key variables. Using the spatial econometric model, Ma et al. (2016) estimated China's WUE as well as the factors that influence the use efficiency of water resources through spatial correlation analysis. Likewise, Zhao et al. (2017) explored the interprovincial WUE environmental challenges and spatial spillover effects in China. Several countries in Africa are bent on achieving SDG 6, which clearly states that by 2030, everyone must have access to safe water and that water efficiency must be improved (Mugagga and Nabaasa 2016; National Development Planning Commission 2019). Consequently, using the generated WUE values, we may identify the trends in efficiency changes and comprehend how efficiently various nations within the sub-region use water. In the meantime, the spillover effects of the determinants may be able to assist policymakers when creating pertinent policies and initiatives. To that effect, this paper proposes a DDF-spatial econometric model to accomplish the sequential execution of WUE measurement and spatial analysis of its determinants in SSA which is described herein as a two-step method. This study contributes to the literature as follows:

-

(a)

This study explores the WUE of 28 countries in SSA from 2007 to 2018. Studies of this nature are important because water resources such as transboundary rivers flow through several countries and so, the quest for its management demands the collaborative efforts of the beneficiary countries. Therefore, assessing the trend of WUE in countries within SSA provides evidence for policy consideration. Theoretically, the study has extended the literature on the urban environmental transition theory. Also, it aligns with (Poumanyvong and Kaneko 2010) that environmental problems associated with urbanisation may reduce at a high level of income, technological improvement, and better ecological laws.

-

(b)

Methodologically, extant research (Ma et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019) has reported on WUE based on the DDF. However, no study has employed the DDF on water use efficiency in the context of SSA, hence our research will serve as a basis for future DDF studies in SSA. Countries in SSA have attracted more foreign investors in recent times, which has enhanced other socioeconomic sectors such as industrialisation, human capital development, and trade openness, among others. To this effect, the present study adds to the literature by extending spatial econometric models such as the global Moran's Index and spatial Durbin model (SDM) to explore the spatial outcomes of corruption, economic growth, human capital development, foreign direct investment, industrial activities, and urbanisation on water use efficiency in the sampled SSA countries.

-

(c)

The purpose of SDG 6.4.2 is to enable adequate freshwater abstraction and distribution to resolve water shortages (FAO 2018). However, studies (Doeffinger and Hall 2020) have shown that non-renewable water consumption coupled with water storage properties have not been reported by the SDG. Again, there is a problem with the current information on the volume and quality of water supplies to calculate and track water stress on a national level, especially in Africa. Therefore, this research incorporates water stress into our analysis for efficient outcomes. The study provides appropriate policy recommendations to the governments in SSA countries on measures to enhance the use efficiency of water and attain the SGD goal six by 2030. The remaining sections of the paper are grouped into three: the methodology (materials, methods, index selection, and data sources) is found in section 2; section 3 is made up of the statistical results and discussion of the study outcome; and section 4 is made up of the conclusion, policy recommendations, limitations, and possible areas for future research.

2. Materials and methods

Data envelopment analysis is an effective way to assess multiple inputs and yields of DMUs. It is not subject to the weights and biases of the DMUs which makes it good to achieve efficient results. Presently, techniques for evaluating WUE include Meta frontier analysis, ratio analysis, SFA, and index system. According to Ma et al. (2016), conventional DEA methods like the Charnes, Cooper, and Rhodes (CCR model), and Banker, Charnes, and Cooper (BCC model) are not strong enough to quantify the efficiency of a desired and undesired input-output model. Therefore, this section of the study highlights the application of the nonradial directional distance function of DEA, which can measure efficiency with a production function made up of desired inputs, the desired output, and an undesired output.

2.1. Directional distance function (DDF)

The directional distance function was first used by Chambers et al. (1996, 1998), and it represents an approach that is very useful in measuring efficiency using non-parametric functions. Färe et al. (2005) added that the old DEA reproductions were insufficient to quantify the efficiency of a production function made up of desired and undesired inputs, hence the need for the DDF. Taking into consideration the need for an undesired output, this study assumes αi as the desired inputs, be as the desired output, and cf as the undesired output in a simple model as follows:

| (1) |

where WUE denotes WUE in different countries of SSA; k−, ke, and kf represent the slacks of desired inputs, desired output, and undesired output respectively; δ is the spatial weight; A, Be, and Cf denote the metrics of the desired inputs, desired output, and undesired output.

2.2. Spatial econometric methodology

According to (Halleck and Elhorst, 2015), spatial econometric modelling became more acceptable when scientists started to focus on spatial characteristics in addition to the conventional panel data, and time series regression modelling. The reason was that the panel data regression study could disclose the long-run connection amid dependent and independent parameters without taking into account the geographic multiplier effects. In the analysis of most time series and panel studies, for example, the estimated parameters derived from the ordinary least square (OLS) regression are usually inconsistent, and at this point, the right approach for resolving such distortion is the spatial econometric modelling (Zhou et al., 2019). However, a spatial correlation test is required before creating a spatial econometric approach to determine the reliance of the explained variable. When spatial dependence is detected, the spatial error model (SEM), spatial autoregressive (SAR), and the spatial Durbin model (SDM) are employed.

2.2.1. Spatial autocorrelation analysis

Spatial autocorrelation analysis has been proven to be a useful tool for describing the spatial uniformity or variation of panel data. According to Bao and Chen (2017), the properties of spatial autocorrelation are to be discovered to characterize a model's spatial evidence in a panel data regression. For such testing, the global Moran's index (I) by Moran (1950) is commonly used, and it is described as follows:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Where It is the whole area's global Moran's I over time t; n denotes the total spatial units; xit signifies the sampled parameters in time t and country i; xt represents the average scores over time t; wij embodies the average of the spatial weight of country i besides country j during time t, wij = 1 if the ith spatial units are neighbors, otherwise, wij = 0. The global Moran's I (It) vary from -1 to 1. A favorable spatial autocorrelation is observed when the result is above zero (0), whereas a negative spatial autocorrelation is observed when the output is less zero (0). Consequently, a higher magnitude of the Moran's I indicates an increase in the spatial autocorrelation. The formula in Eq. (5) is used to determine the significance of the Moran's I.

| (5) |

2.2.2. Spatial econometric models

According to Zhou et al. (2019), issues created by spatial variability and spatial correlation within variables can be solved using spatial models. In distinct, the spatial autoregressive approach depicts the explained parameter's interaction impact in adjacent areas on the dependent variable in a particular spatial unit. Besides, a spatial error term in the SEM reveals the interplay influence of the independent factors in an adjoining unit on the explained variable in a local unit. But then, both the spatial lag of the explanatory variable and the spatial error term of the predator factors are included in the SDM. The SAR, SEM, and SDM adapted from Elhorst (2003, 2014) for this study are defined as follows:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

where yit is the explained parameter in location i and time t; β is the explanatory parameter's regression coefficient which represents the contribution of xit on yit; α is the persistent term; the intercepts in country i and time t are; μit is the error term; δ is the spatial autoregression coefficient which indicates how the relying element in surrounding locations affects the outcome parameter in the actual spatial area. When δ is positively significant, it is worth noting that improving a specific feature in a spatial area might result in an improvement in the parameter in other nearby spatial units; N denotes the number of geographical areas, which in this case is 28 countries in sub-Saharan Africa; σit is the spatial autocorrelation error term; ρ is the spatial error quotient which represents the relationship between the spatial error term in neighbouring spatial units and the spatial error term in the local spatial unit; θ is the explanatory parameter's spatial lag term coefficient, which shows the effect of the explanatory parameters in nearby spatial units on the local spatial unit, and Wij is the spatial weight matrix, which shows that the ith and jth spatial units are neighbours when Wij = 1, otherwise Wij = 0.

Eliminating spatial correlation leads to incorrect OLS estimates of multi-WUE driven by spatial correlation (Bao and Chen, 2017). As a result, this research used a geographic panel data technique to assess WUE characteristics for 28 countries in SSA. The fixed and random effect methods were evaluated using the Hausman test. The random fixed-effect model ignores impacts from nearby units, whereas fixed-effect models show how specific geographical units can affect regression parameters. Because the researchers are concerned with the individual effects of the spatial units, the fixed-effect model is employed in our analysis.

2.2.3. Direct and indirect effects estimation

The SDM depicts that the local spatial unit's explained parameter (ya) is impacted by the neighbouring spatial unit's explained parameter (yb), as well as the local spatial unit's explanatory parameters (xa), and the neighbouring spatial unit's explanatory parameters (xb). That is, xa can have a significant influence on (xa → ya). Also, through spatial autocorrelation, xa can have an impact on yb, and later on ya as (xa → yb → ya). The significant impacts of the predictor factors are the two effects of xa on ya. Similarly, xa can affect yb (xa → yb), whilst influencing ya and yb via spatial autocorrelation of (xa → ya → yb). The spillover effects or indirect effects of the explanatory variables are the results of xa on ya. The consequence of the explanatory variable's direct and indirect impacts on the explained parameter must be recognized. The SDM is therefore converted into the subsequent (Elhorst 2014) approach since it deviates from the estimated regression coefficient of the parameters as stated in Eq. (9).

| (9) |

where the spatial error term is denoted by αtN. As a result, the explained variable's truncated expression for the kth explanatory parameters at a given time is described as follows:

| (10) |

From Eq. (10) above, the direct effects are the mean of the matrix's diagonal elements on the right, while the indirect effects are the column entries off-diagonal in the model (Elhorst 2014).

2.3. Data source

This section comprises the sampled variables, data sources and period of the study. To measure the WUE, the two main aspects for consideration are the resource, and the environmental dimensions (Ma et al., 2016). Labor, capital, and water formed the resources aspect while water stress is used as the environmental aspect. The authors of this study adopted three desired inputs, one desired output and one undesired output based on the construction of the index system for the WUE used in previous studies (Addae et al., 2022; H. Wang et al., 2019). Specifically, labour, capital, and total water abstracted were used as the desired inputs, water stress as the undesired output, and gross domestic product (GDP) as the desired output. The items used to develop the WUE input-output system are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Display of data characteristics for evaluating water use efficiency.

| Index | Variable | Units | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Capita Stock | Millions of US Dollars | WDI |

| Input | Labor | Total Employment | WDI |

| Input | Water withdrawal | Billions of cubic meters | WDI |

| Desired Output | GDP | Millions of US Dollars | WDI |

| Undesired Output | Water Stress | GDP per cubic meter of Total Freshwater (US Dollars) | WDI |

Please note: WDI indicates World Development Indicators.

The total number of the population who are employed represented the labour input. Because liquidity plays an important role in every economic development, capital stock, which is measured in millions of US dollars was used as input. In addition, total water abstracted for domestic, industrial, and agricultural purposes was employed. Previous studies have engaged overall wastewater as the undesired product. However, due to data unavailability for wastewater in most countries in Africa, water stress was adopted based on research by Mekonnen and Hoekstra (2016). Finally, GDP, measured in constant 2010 US dollars was used as the economic indicator.

The improvement of WUE is essential to promoting sustainable water resources management. Therefore, it is essential to investigate possible factors that may influence the efficient use of water, especially in Africa where there has been a record of decoupling nexus between anthropogenic activities and water resources management (Sun et al., 2021). Urbanization, industrial activities, export, foreign direct investment, education, and government interference are some of the possible indicators of WUE. As urbanisation increase with proper urban planning, it is possible for WUE, and water resources management to be achieved (Cai et al., 2018). As a key contributor to economic development, industrial activities are considered to be the primary determinants of WUE (Ma et al., 2016). That is, from the abstraction, and production, through to the final disposal stage of industrial water, its efficiency may be compromised if strict regulations are not adhered to. Studies have shown that countries that are well endowed with water resources tend to manufacture water-intensive products for export. However, the long-term production of these water-intensive products for consumption in a country and export to other countries will result in virtual water transfer, and reduce the available water resources (Wang et al., 2018).

Foreign direct investment promotes human capital development and management, increases technology and equipment use, strengthens, and promotes industrial spillover effects which ensure WUE. According to Zomorrodi and Zhou (2017), foreign direct investments not only increase innovations and new technologies that conserve resources but also help to optimize resource allocation and reduce the waste of resources. In addition, education, in the form of human capital formation helps to enhance environmental quality and WUE as stated in previous studies (Dauda et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2016). Wang et al. (2018) found that increasing the literacy rate of a population promotes innovation, skills, and knowledge quality of the working force in China. They further stated that educated people are conscious of protecting their environment, and it is also easy for authorities to disseminate information to educated people through print and electronic media. In terms of government interference, Muller (2020) reported that nepotism and embezzlement of funds for water resources management are the main contributors to poor quality and inadequate water supply in Africa.

This study thus investigates the spillover effects of urbanisation (URB), industrial activities (IND), export (EX), foreign direct investment (FDI), education (EDU), and corruption (COR) on WUE in SSA. Other factors such as water price, technological progress and environmental regulations could have been used in this study as control variables, but data on such elements are not available for most countries in SSA. The study used panel data from 28 sampled countries in SSA based on the selected variables. The study covers the period 2007–2018 for better and in-depth analysis and discussions to implicate the WUE elements in SSA. The sources of information for the variables used in this research are World development indicators (WDI 2020) and Transparency International (2016). These are internationally recognized data sources that have been used by previous researchers such as (Addae et al., 2022; Musah et al., 2020). The variables, their descriptions, and sources are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of data characteristics and sources.

| Variable | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| WUE | Water use efficiency scores | DDF calculated by the authors |

| URB | Urbanization (total urban population) | WDI |

| IND | Industry (value added, constant 2010 US$) | WDI |

| FDI | Foreign direct investment (Net inflows %) | WDI |

| EX | Export of goods and services (constant 2010 US$) | WDI |

| EDU | Literacy rate (% cumulative) | WDI |

| COR | Corruption (CPI %) | TI |

Note: WDI indicates World Development Indicators; CPI is corruption perception index, TI is Transparency International.

3. Empirical results and discussion

3.1. Estimates of water use efficiency in sub-Saharan Africa based on the directional distance function

The MaxDEA ultra 8.17.1 software was used in calculating the WUE based on the DDF in SSA, as presented in Eq. (1). The DDF model by Chambers et al. (1996, 1998) was employed to get a fair understanding of the direction of performance in WUE over time. Extant studies (Pan et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2018) have demonstrated that under normal conditions, water consumption alone cannot produce the desired outcome. They, therefore have suggested that extra items (multiple inputs) should be added to the system to produce a satisfactory output. There is no doubt that the ecosystem and the human environment are affected by water use, consequently, an undesired output needs to be included, and in this research, we introduced water stress.

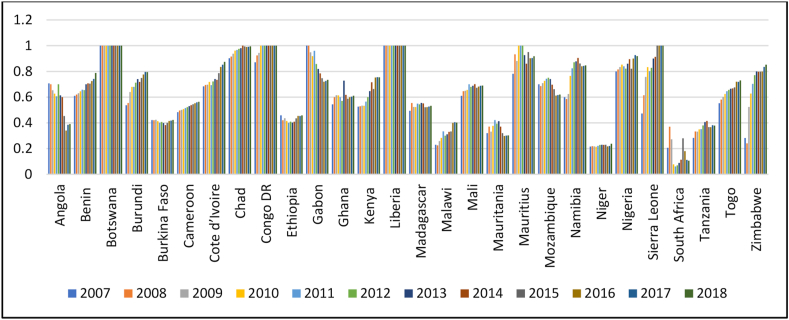

Figure 1 shows the country variations of the WUE scores using the multiple inputs method to extract the desired and undesired outcomes. The average WUE in Botswana and Liberia reached the optimal frontier (1.00). The results also reveal that the next efficient countries are Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Mauritius, Congo DR, Gabon, and Nigeria, and countries with very poor performance are Niger and South Africa. The economic implication could be that countries with high WUE scores have superior infrastructure and policies, allowing them to leverage economic expansion while keeping activities that strain water resources to a minimum. This outcome is in line with the press release of the Minister of Energy and Public utilities of Mauritius concerning the government's efforts to provide efficient water management systems to the populace on a 24-hour basis (AllAfrica 2015). Similarly (World Bank 2021), featured a story on the Nigerian government's efforts to develop several initiatives to improve access to water and sanitation such as the construction of treatment plants and water saving infrastructure in schools, healthcare facilities, markets and motor parks.

Figure 1.

Water use efficiency in sub-Saharan Africa.

The overall mean efficiency values for all countries over the study period was also examined, and the results, as shown in Figure 2, indicate that the total mean efficiency scores improved steadily from 0.582 in 2007 to 0.669 in 2013. However, it decreased in 2014 and 2015 by 0.666 and 0.661, respectively, but an increase to 0.698 was witnessed in 2018. The economic implication of this outcome could be that the overall SSA has experienced an upsurge in the efficient use of water resources. This can be attributed to urbanisation better management policies that authorities in various countries are implementing to enhance sustainable WUE. For instance, the African Vision for 2025 aimed at ensuring sustainable use of water across the continent of Africa (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa et al., 2003). In the same vein, a World Bank Group report by (van den Berg and Danilenko 2017) has shown how utilities that provide water and wastewater services in low-income countries of Africa tend to express slightly higher levels of water coverage and operational performance.

Figure 2.

Overall mean score of water use efficiency between 2007 and 2018.

3.2. Spatial autocorrelation analysis of water use efficiency in SSA

Based on Eqs. (2), (3), (4), and (5), the global Moran's I of WUE for the sampled SSA countries was computed using Matlab R2015a software, and the result is found in Table 3. All the values were positively significant at the 1% threshold. This result indicates that the variations in WUE in the SSA nations are defined by a positive spatial correlation. Also, unlike a random distribution, the outline of a spatial distribution shows persistent spatial accretion. That is, countries with comparable WUEs possess features of strong spatial aggregation.

Table 3.

Moran's index of water use efficiency in SSA.

| Year | Moran's I | Z (I) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 0.742 | 21.037 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

| 2008 | 0.965 | 17.003 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

| 2009 | 0.977 | 13.007 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

| 2010 | 0.953 | 10.305 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

| 2011 | 0.601 | 12.734 | 0.003∗∗∗ |

| 2012 | 0.965 | 7.932 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

| 2013 | 0.937 | 13.304 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

| 2014 | 0.904 | 20.312 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

| 2015 | 0.851 | 33.757 | 0.000 ∗∗∗ |

| 2016 | 0.827 | 17.604 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

| 2017 | 0.913 | 18.268 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

| 2018 | 0.911 | 25.004 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

Note: ∗∗∗ indicates a significant level of 1%.

3.2.1. Model selection

To generate models for spatial econometrics, spatial tests of relevance are performed. The spatial lag Lagrange Multiplier (LM), spatial lag robust LM, spatial error LM, and spatial error robust LM were used to investigate the spatial effects of spatial fixed effect, time fixed effect, and spatial and time fixed effects. The result as shown in Table 4 indicates that the spatial error effects in the form of spatial fixed effect and the time fixed effect did not pass the robustness LM test. However, the spatial lag and spatial error tests were significant in the spatial and time fixed-effect form. Also, the spatial lag effects were highly effective compared to the spatial error effects, thus, the proposal of the SDM.

Table 4.

Results of Lagrange multiplier test with varied spatial and time-specific effects in SSA.

| Item | Spatial fixed-effect | Time fixed-effect | Spatial and time fixed-effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial lag LM | 32.38∗∗∗ | 20.72∗∗∗ | 65.05∗∗∗ |

| Spatial lag robust LM | 17.49∗∗∗ | 11.68∗∗∗ | 25.03∗∗∗ |

| Spatial error LM | 25.11∗∗ | 13.43∗ | 51.56∗∗∗ |

| Spatial error robust LM | 10.22 | 4.36 | 11.54∗∗∗ |

Note: ∗∗∗ indicate a significant level at 1%.

Furthermore, Table 5 displays the outcome of the Hausman test and the Wald test conducted to assess the appropriateness of the SDM with spatial and time-fixed effects. At a significant threshold of 1%, the Hausman test was 32.19, and the p-value was 0.000, which is an indication that the spatial and time-fixed effect is better than going for a random effect. The Wald test results showed that the SDM could not be reduced to spatial SAR or SEM because both the Wald Lag and the Wald error were statistically significant at 1%. Therefore, the SDM with spatial and time-fixed effects is best for the study. The WUE of different countries is selected as the explained variable, and the explanatory variables include URB, IND, FDI, EX, EDU, and COR.

Table 5.

Results of the spatial and time fixed effect model tests.

| Test | Statistics | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Hausman | 32.19 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

| Wald lag | 15.90 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

| Wald error | 24.51 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

Note: ∗∗∗ indicates a significant level of 1%.

3.3. Estimation models for the spillover effects

In line with Eqs. (6), (7), and (8), the estimated results of the SAR, SEM, and SDM are presented in Table 6. To arrive at a better result, a lagged dependent variable term (L. dep) and an error term (error. dep) were added to the SAR, SEM, and SDM, respectively. The coefficients of the added lagged variables and the rho were all significant at 1%. However, the spatial regression coefficient and rho of the SDM were relatively large. This means that the SDM could perform better extraction of WUE's spatial effects and generate reliable results. Therefore, the SDM model is further discussed.

Table 6.

Estimation results of the spatial panel models.

| Variables | SAR |

SEM |

SDM |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value | |

| URB | 0.963 | 0.063∗ | 0.093 | 0.047∗∗ | -0.763 | 0.072∗ |

| IND | -0.146 | 0.158 | -0.891 | 0.730 | 0.173 | 0.004∗∗∗ |

| FDI | -0.185 | 0.027∗∗ | 0.519 | 0.063∗ | 0.204 | 0.041∗∗ |

| EX | -0.401 | 0.986 | -0.247 | 0.485 | -0.641 | 0.074∗ |

| EDU | 0.004 | 0.000∗∗∗ | -0.040 | 0.443 | -0.251 | 0.069∗ |

| COR | 0.006 | 0.005∗∗∗ | 0.003 | 0.086∗ | 0.032 | 0.014∗∗ |

| W∗URB | -0.921 | 0.028∗∗ | ||||

| w∗IND | 0.243 | 0.072∗ | ||||

| w∗FDI | -0.229 | 0.015∗∗ | ||||

| w∗EX | 0.014 | 0.286 | ||||

| w∗EDU | -0.001 | 0.703 | ||||

| w∗COR | 0.016 | 0.011∗∗ | ||||

| δ | 1.299 | 0.000∗∗∗ | 0.175 | 0.000∗∗∗ | ||

| ρ | 0.156 | 0.004∗∗∗ | ||||

| rho | 0.978 | 0.000∗∗∗ | 0.788 | 0.001∗∗∗ | 0.982 | 0.000∗∗∗ |

Note: ∗∗∗, ∗∗, ∗ indicate a significant level at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively.

The SDM results, as displayed in Table 6, indicate that the significant and positive spatial regression coefficient is an indication that WUE in one country is not only influenced by the independent indicators such as URB, IND, FDI, EX, EDU, and COR but also influenced by the water use efficiency and independent indicators of the neighbouring countries. In other words, WUE has noticeable spatial spillover effects on SSA's economies. That is, for the average of 28 countries sampled for this study, a unit change in WUE in neighbouring countries can harness the WUE of the local country by 0.175 units. Explaining further, WUE in SSA exhibits spatial aggregation features, and the countries with high-efficiency levels play a significant role in fostering effective use and management of water resources in the adjacent countries. This outcome agrees with (United Nations Development Program 2012) that the technical and commercial operations in the quality of service provided by the water sector in Gabon have shown a substantial improvement.

The coefficient of URB had a significant and positive influence on water use efficiency in the local country. That is, all things being equal, a unit change in urban growth will lead to an increase of 0.763 units in the use efficiency of water in the local spatial unit. The economic implication is that a local country with better urban growth policies tends to manage the available water resources, hence promoting water use efficiency as less water is consumed. For instance, infrastructure for improving the abstraction and supply of water resources and water pollution treatment is implemented in recent urban housing in West Africa (Addae et al., 2022). The coefficient of URB in adjacent countries’ influence on water use in the local unit is negative and statistically significant. This means that a unit change in URB in neighbouring countries leads to a 0.921 increase in water use efficiency in the local country. This means that with time, good urban growth policies in countries with high URB in SSA could promote the efficient use of water resources in adjacent countries. This result is in line with McGrane (2016), who reported that recent urban infrastructures aid in promoting water resources' sustainable use.

The coefficient of IND (−0.173) effect on water use efficiency in the local country as shown in Table 6 is negative and statistically significant at 1%. This indicates that industrial activities play an essential role in intensive water use and deaccelerating WUE in a given country. The economic implication of this outcome is that, as population growth and URB increase, more pressure is placed on the industrial sectors to produce and process goods for the populace's consumption. In doing so, water resources are exploited, which affects the effective supply of the resource to other sectors. Also, Sun et al. (2021) have reported that most industries in Africa do not have adequate infrastructure to treat wastewater before discharging it into nearby water bodies, hence reducing the quality and quantity of the available water resources. For this reason, areas with high agriculture and industrial activities experience low WUE. The coefficient of IND in the neighbouring countries' influence on water use in the local country is 0.243 and significant at 10%. This means that as IND in neighbouring countries upsurges, there will be an over-exploitation of water resources in those countries. And due to spatial aggregation, polluted water resources in a country could flow into adjacent countries and, in the long run, reduce the water use efficiency in the local country. This finding aligns with the report of Failler et al. (2016) that untreated water disposed of in the environment of Djibouti pollutes upstream rivers of Ethiopia and Somalia. Also, Amuquandoh (2016) indicated that the excessive withdrawal of water by Burkina Faso has resulted in a low water supply to the Volta River of Ghana.

This study also indicated that the local unit's water use efficiency decreased significantly as a result of FDI but had a negative impact on WUE. That is, a unit increase in FDI resulted in a decrease of 0.203 units in water use efficiency, which in the long run, decreases the efficient use of water resources in a specific country in SSA. The economic implication is that, as economic cooperation increases, multi-national companies that establish their firms in SSA countries exert much stress on water resources through withdrawal for various production purposes. According to (Neafie 2018), FDI inflows into developing countries are mostly focused on the manufacturing and resources extractive sectors that causes increased water use and create a water quality and quantity issue. This finding of our study is similar to the result of Jorgenson (2007) who explored the effect of FDI on air and drinking water in developing countries. His outcome showed that multi-national companies in emerging economies are more likely to use unprocessed substances in diverse productive activities and this often spawns waste products, resulting in water pollution and excess water consumption. In countries such as Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, and Zambia, Chuhan-Pole et al. (2017), and Mapani and Kříbek (2012) have reported on how mining activities spearheaded by foreign investors have polluted water resources. This outcome also aligns with Aboka et al. (2018) that FDI in the mining sector is the primary cause of water pollution in most Ghanaian water bodies. Therefore, in as much as trade openness promotes economic development, implementable measures for water consumption by both foreign and domestic investors should be formulated by water authorities in the SSA countries.

Moreover, the adjacent economies' FDI had a substantial influence on water use efficiency and a rise in WUE in the local spatial unit. That is, a unit change in FDI of the adjacent economies led to a 0.229 unit increase in water use efficiency of a local country in SSA. The economic implication is that knowledge and technology spillover through FDI in neighbouring countries can reduce the amount of water consumed in an adjacent country, and thereby harness water use efficiency. This result agrees with a presentation by Ola-David (2013) that the efficient role of institutions and FDI in Africa can promote sustainable development of which water is an essential component. In addition, Xu et al. (2019) found that enterprises invested with foreign capital have a positive and significant influence on China's water environment.

The result of the study also demonstrated that export in a local unit had a positive and statistically significant influence on water use efficiency. A unit change in export improved water use efficiency in SSA countries by 0.641 units. The economic implication is that countries in SSA experiencing an upsurge in economic growth through export can fund the purchase and installation of water conservation infrastructure in the agriculture, industrial, and domestic sectors. Therefore, a small amount of water is required to produce several products for both export and consumption in a local country. To buttress this point, the 2020 OEC report for Botswana showed that total exports reached $4.58 billion (OEC 2020). According to (Mguni 2019), major export products of Botswana are mainly minerals such as Diamonds, Gold, and Bovine among others which do not depend so much on water use. Similarly, the (U. S. Department of Commerce 2020) revealed that Chad's export of goods such as oil, cotton and livestock have increased remarkably increasing their per capita GDP to $1645 at purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2019. This outcome is consistent with Cazcarro et al. (2015)'s finding that export significantly reduced Spain's water footprint. Again, this result is in line with the observation of Zheng et al. (2018), who claimed that import and export trade positively impacted WUE in China during their entire study period. In terms of the impact of export from the neighbouring countries on a local country's WUE, a positive but insignificant coefficient was recorded. To explain further, a unit change in export in the neighbouring countries had no strong impact on the efficiency of water use in the local country.

Education is the backbone of development in every economy. Thus, this study explored the impact of education on WUE in the sampled countries of SSA. The results showed that education in a particular country had a good impact on WUE in that specific local unit. However, people's educational level in the adjacent countries did not possess any material influence on the efficient use of water resources in the local country. To explain further, a unit change in the people's literacy rate led to an upsurge of 0.251 units in water use efficiency in the local country. This indicates that the higher the educational level of the residents in a particular country, the more they will advocate for environmental protection, including the efficient use of water resources. Authorities in countries with high literacy rates spend less time and resources introducing innovative ways and technologies to save water and reduce pollution to the citizenry. This outcome agrees with Joshi and Amadi (2013) who examined the effect of water, sanitation, and hygiene measures on adequate health among African schoolchildren. The children's awareness of hand-washing habits and management of the school's limited water supply was one of the most praiseworthy aspects of their findings. Again, this study supports Wang et al. (2018) whose research identified a strong link between human development and WUE in China. Similarly, Yao et al. (2019) stated that raising people's standards of education produces advantageous externalities that improve environmental quality. Proudfoot and Kelley (2017), on the other hand, highlighted that technical improvement, as a result of increased knowledge, might have a positive impact on water consumption. They went on to say that when people's academic levels rise, they learn how to make equipment and chemicals that cause environmental and water resources pollution in the long term. Nonetheless, Ma et al. (2019) posited that persons with higher education levels are more likely to follow environmental protection laws and conserve biodiversity.

Finally, the result in Table 6 revealed that in a specific country and from the adjacent countries, COR, which is a proxy for government interference in this study, recorded a significant negative influence on water use efficiency of the local country and neighbouring countries by 0.032 and 0.016 units at a significant level of 5% respectively. It is a fact that government influence could have different effects on WUE in different countries. But a common trend of government interference where adequate water-saving infrastructure is found in some urban regions while other residents in the peri-urban and rural areas lack these facilities is common among most countries in Africa (Transparency International 2016). The finding of this study corresponds to the report of Davis (2004) that in Africa, people in low-income areas pay four times higher than those in high-income areas yet, the water supplied to the former sect of people is of low quality. This result also aligns with Stålgren (2006) that some officials in the water sector often collude with some water service providers and sell water at unauthorized prices to people living in the urban fringes of African countries. Again, this finding coincides with Odiwuor (2013) who emphatically stated that corruption is the primary cause of water pollution in Africa. It is not surprising that people in the gold mining areas of Ghana have registered their displeasure about how the present government allow foreigners to engage in illegal mining, which is the prime cause of forest destruction and pollution of almost all the country's water resources (Asante 2017; Crawford and Botchwey 2017). Furthermore, Muller (2020) investigated corruption in South Africa's water sector and their results indicated that the embezzlement of funds for water resources management contributed to the shortage of water supply in the country. They further reported on how industrial companies in South Africa frown on water demand management plans. Yet, authorities in the water sector refuse to punish those culprits due to their relationship with officials in those entities irrespective of efforts made by some cross-country policymakers (African Ministers Council on Water (AMCOW), and the Volta Basin Authority) to promote the accessibility of safe and adequate water for the people.

3.4. Analysis of the determining components' spatial spillover effects

The regression coefficient of the SDM shows how the observed factors of the specific country and its neighbouring countries interact with WUE. However, the ancillary interaction impacts through spatial spillovers of water use efficiency are usually not measured. For that reason, the authors further estimated the direct and indirect effects of the inducing elements on SSA countries’ WUE based on the SDM (Eqs. (9) and (10)). As shown in Table 7, the results of the indicators vary based on the strength of their coefficients. Also, grounded on the absolute values, the magnitude of the respective effects is examined.

Table 7.

Direct and indirect effects of the influencing factors of SSA's water use efficiency.

| Variables | Direct effects |

Indirect effects |

Total effects |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value | |

| URB | -0.249 | 0.056∗ | -0.702 | 0.001∗∗∗ | -0.951 | 0.055∗ |

| IND | 0.560 | 0.797 | 1.418 | 0.814 | 1.978 | 0.795 |

| FDI | 0.760 | 0.001∗∗∗ | 2.017 | 0.041∗∗ | 2.777 | 0.004∗∗∗ |

| EX | 0.142 | 0.019 | 0.621 | 0.062∗ | 0.763 | 0.032∗∗ |

| EDU | -0. 576 | 0.392 | - 0.131 | 0.474 | -0.707 | 0.390 |

| COR | 0.032 | 0.003∗∗∗ | 0.024 | 0.084∗ | 0.056 | 0.097∗ |

Note: ∗∗∗, ∗∗, and ∗ indicate significant levels at 1%, 5%, and 10% respectively.

According to the findings, URB had both direct and indirect significant negative impacts on water consumption in SSA. This suggests that URB reduces water use in both the local country and the adjoining countries. More so, the indirect effect of URB is stronger in absolute value than the direct effect. On average, a unit change in URB would lower water consumption by 0.249 and 0.702 points in each country and its neighbouring units, correspondingly, and by 0.951 points in the entire region, implying that water use efficiency will increase. The economic implication is that proper water management by recent SSA urban authorities leads to water consumption reduction. However, FDI, EX, and COR had considerable positive direct and indirect impacts on water consumption (a harmful influence on WUE). Building on the foregoing assumption, a shift in FDI, EX, and COR increased water consumption in each country by 0.760, 0.142, and 0.032, while their indirect effects on neighbouring countries were 2.017, 0.621, and 0.024, respectively. This suggests that URB, FDI, EX, and COR's spillover effects are the primary indicators of SSA's WUE. The implications of IND and EDU were, however, different. The direct and indirect implications of IND on water consumption were positive but statistically insignificant in both the local and nearby countries. EDU, as well, had negative and insignificant direct and indirect effects on water consumption. This suggests that neither IND nor EDU had a significant impact on water consumption and WUE in a specific country and its SSA neighboring economies. This outcome that EDU had no major effect on WUE differs from Ma et al. (2019) who reported that EDU has a significant and positive effect on WUE in China.

4. Conclusions and policy recommendations

With the recent increase in water scarcity and pollution cases in SSA, it is important to enhance the efficient use of water resources to ensure a sustainable water supply for all. This study thus estimated the trend, and levels of WUE in 28 SSA countries from 2007 to 2018 using the directional distance function approach. The results showed that the most water-use-efficient countries in SSA are Chad, Botswana, Congo DR, Gabon, Cote d’Ivoire, Liberia, Mauritius, and Nigeria whereas countries with poor performance include Niger and South Africa. The study further explored the spatial effects of WUE indicators in SSA using robust spatial panel techniques. The main results for the spatial models relate to the positive spatial spillover effects in the water use efficiency estimate of a single country on neighbouring states. The outcome of the global Moran's I revealed that WUE in SSA exhibit a substantial spatial autocorrelation. Employing the spatial Durbin model, the findings exhibited that URB, EX, and EDU have an encouraging and noteworthy influence on WUE in SSA. This implies that in the long run, URB, an increase in HCD, as well as EX can contribute to the efficient use of water resources. However, IND, FDI, and COR had a substantial and adverse influence on WUE in SSA. Therefore, SSA countries have to be well prepared to confront the challenges of intensifying FDI which is extensive in the manufacturing and resources extraction sectors, and COR by authorities in the water sectors which have been discussed as factors inhibiting the efficient use of water resources in SSA. The outcome of the spatial model is linked to that of the spillover effects where URB demonstrated a major positive impact on WUE in both the local and adjacent countries whereas FDI, EX, and COR had significantly adverse direct and indirect impacts on WUE in the local and neighbouring countries. This is an indication that a country's degree of water resources management would cause similar response in neighbouring countires.

Grounded on the above-mentioned outcomes, the following recommendations are made to harness water use efficiency in SSA:

-

(a)

This study showed that URB improved water use efficiency in SSA. Therefore, the responsible authorities should continue with the measures that they have adopted. Also, the authorities in SSA countries responsible for water resources management should formulate and implement other policies that would promote the sustainable and efficient use of water resources. In addition, authorities in the SSA countries should collaborate with other countries like China which have success stories of water use efficiency in promoting mechanisms that enhance the efficient use of water resources such as water-saving technologies and management while making them affordable, especially in the urban sectors. This can be done by promoting urban designs that consider water use efficiency from the turn of the tap until the wastewater flows into appropriate drains. Although some developing countries are implementing rainwater harvesting policies, most countries in SSA are yet to roll it as a full-fledged policy for implementation. This study, thus, suggests that given the rapid climate change leading to extensive rainfall in recent years, authorities in SSA countries should harvest, treat, and store the rainwater to improve the sustainable supply of water in the water-rich countries while enough water can be transferred to neighbouring water-stressed countries.

-

(b)

As industrial activities had negative impact on water use efficiency, this study suggests that authorities should frequently monitor the amount of water withdrawn for industrial purposes at a particular time and periodically monitor how wastewater from industrial sites is treated before discharging into nearby waterbodies or the environment.

-

(c)

Although the outcome of this study showed that export had a positive influence on water use efficiency, authorities should ensure that the production and exportation of water-intensive products are replaced with goods that require less water for production to reduce the exploitation of the available water resources.

-

(d)

Human capital development should be made accessible and affordable in SSA countries to enlighten the citizens on the need to ensure environmental sustainability. In addition, authorities in the water sectors of SSA countries should involve all stakeholders in sensitization and awareness programs on water resource management in both rural and urban settings. This can be done by using the local people and local languages that can be well understood by the indigenous people. Moreover, safe water groups can be formed in schools and communities as an add-up to the awareness creation through the print and electronic media.

-

(e)

Private investors should be allowed into the water sector to break the menace of monopoly entrusted into the hands of a few government officials in the SSA countries who determine when and where adequate and potable water should be supplied. This can be done by re-strategizing the water sector management which is often dominated by the government to include private entities in the form of public-private partnerships or grant independence to private investors to also abstract, treat, supply, and manage water resources.

-

(f)

Foreign investors in SSA countries should be tasked to adhere to all protocols concerning water resources management. This can be promoted by periodic inspection of water use and disposal, especially by industries and large-scale farming. Authorities should enforce water pollution charges and sanctions on both foreign and local investors who defy the recommended water demand management plans to deter industries from over-exploiting water resources in their quest to increase production for local consumption and export purposes.

-

(g)

Positive spatial spillover effects could be beneficial for water resources management, policy formulation and implementation when a cordial relationship exists among transboundary shareholders of water resources. It is therefore important for authorities in the water sectors of SSA countries to strengthen the already established water authorities such as the African Ministers Council on Water (AMCOW), International Congo-Ubangui-Sangha Commission, Niger Basin Authority, and Volta Basin Authority to learn and share implementable policy ideas to achieve the SDG 6 by 2030 and beyond. In this case, success stories and indigenous innovative capabilities can be shared with member states to ensure sustainable water use and management in SSA.

5. Limitations and suggestions for future research

Regardless of the extensive work done, this study encountered a few limitations. For instance, the outcomes presented are based on data for the years 2007–2018 due to data unavailability for most countries in SSA, especially before the year 2000. Future research may consider other important variables such as water price, technological progress and environmental regulations to comprehend the relationship amid urbanization, industrial growth, foreign direct investment, human capital development, government interference, and water use efficiency in SSA and other regional blocs. Methodologically, the directional distance function is weak in complying with unit-invariant properties regarding the value of the direction vectors. Therefore, prospective studies may take into account new methods that may take into account characteristics that comply with unit-invariant properties. The current study's focus is restricted to SSA nations, but a comparative study involving SSA and other regional blocs like Asia and Europe can be conducted in future. Future research may also analyze and expand our model and datasets by incorporating more African countries or have a comparative water use efficiency study on African countries grouped into sub-regional blocs or income levels.

Disclaimer

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding body.

Consent to publish

The authors of this manuscript grant the publisher of this journal the sole exclusive license of the full copyright, which licenses the Publisher hereby accepts.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Ethel Ansaah Addae, Ph.D.: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Dongying Sun, Ph.D: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Olivier Joseph Abban; Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Jeffery Fianko Addae: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or, data.

Funding statement

Dongying Sun was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China of China [71704068], Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation, Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China [21YJCZH139], Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province [21GLB007].

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Aboka E.Y., Jerry C.S., Dzigbodi D.A. Review of environmental and health impacts of mining in Ghana. J. Health Poll. 2018;8(17):43–52. doi: 10.5696/2156-9614-8.17.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addae E.A., Sun D., Abban O.J. Evaluating the effect of urbanization and foreign direct investment on water use efficiency in West Africa: application of the dynamic slacks-based model and the common correlated effects mean group estimator. Environ. Develop. Sustain. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- AllAfrica Mauritius: government determined that the population has water supply on a 24 hour basis. 2015. https://allafrica.com/stories/201502241589.html

- Amuquandoh M.K. University of Ghana; 2016. An Assessment of the Effects of the Bagre Hydro Dam Spillage on Ghana-Burkina Faso Relations.http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/handle/123456789/27435 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Asante R. China’s security and economic engagement in West Africa: constructive or destructive? China Quart. Int. Strat. Stud. 2017;3(4):575–596. [Google Scholar]

- Bao C., Chen X. Spatial econometric analysis on influencing factors of water consumption efficiency in urbanizing China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017;27(12):1450–1462. [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Yin H., Varis O. Impacts of urbanization on water use and energy-related CO2 emissions of residential consumption in China: a spatio-temporal analysis during 2003-2012. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;194:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cazcarro I., Duarte R., Martín-Retortillo M., Pinilla V., Serrano A. How sustainable is the increase in the water footprint of the Spanish agricultural sector? A provincial analysis between 1955 and 2005-2010. Sustainability. 2015;7(5):5094–5119. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R.G., Chung Y., Färe R. Profit, directional distance functions, and Nerlovian efficiency. J. Optim. Theor. Appl. 1998;98(2):351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers Robert G., Chung Y., Färe R. Benefit and distance functions. J. Econ. Theor. 1996;70(2):407–419. [Google Scholar]

- Charnes A., Cooper W.W., Rhodes E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978;2(6):429–444. [Google Scholar]

- Chuhan-Pole P., Dabalen A.L., Land B.C. 2017. Mining in Africa: Are Local Communities Better off? the World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford G., Botchwey G. Conflict, collusion and corruption in small-scale gold mining: Chinese miners and the state in Ghana. Commonwealth Comp. Polit. 2017;55(4):444–470. [Google Scholar]

- Dauda L., Long X., Mensah C.N., Salman M., Boamah K.B., Ampon-Wireko S., Kofi Dogbe C.S. Innovation, trade openness and CO2 emissions in selected countries in Africa. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;281 [Google Scholar]

- Davis J. Corruption in public service delivery: experience from south Asia’s water and sanitation sector. World Dev. 2004;32(1):53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Doeffinger T., Hall J.W. Water Resources Research; 2020. Water Stress and Productivity: an Empirical Analysis of Trends and Drivers. [Google Scholar]

- Elhorst J.P. Specification and estimation of spatial panel data models. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2003;26(3):244–268. [Google Scholar]

- Elhorst J.P. Matlab software for spatial panels. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2014;37(3):389–405. [Google Scholar]

- Failler P., Karani P., Seide W. IGAD - Intergovernmental Authority on Development; Djibouti: 2016. Assessment of Environmental Pollution and its Impact on Economic Cooperation and Integration Initiatives of the IGAD Region. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . 2018. SDG Indicator 6.4.2 - Water Stress.http://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/indicators/642/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Färe R., Grosskopf S., Noh D.-W., Weber W. Characteristics of a polluting technology: theory and practice. J. Econom. 2005;126(2):469–492. [Google Scholar]

- Halleck Vega S., Elhorst J.P. The slx model: the slx model. J. Reg. Sci. 2015;55(3):339–363. [Google Scholar]

- Hu J.-L., Wang S.-C., Yeh F.-Y. Total-factor water efficiency of regions in China. Resour. Pol. 2006;31(4):217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson A.K. Does foreign investment harm the air we breathe and the water we drink? A cross-national study of carbon dioxide emissions and organic water pollution in less-developed countries, 1975 to 2000. Organ. Environ. 2007;20(2):137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A., Amadi C. Impact of water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions on improving health outcomes among school children. J. Environ. Publ. Health. 2013:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2013/984626. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Ma X. Econometric analysis of industrial water use efficiency in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015;17(5):1209–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., Shi C., Chou N.-T. China’s water utilization efficiency: an analysis with environmental considerations. Sustainability. 2016;8(6):516. [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Dai J., Wen H. The influence of trade openness on the level of human capital in China: on the basis of environmental regulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;225:340–349. [Google Scholar]

- Mapani B., Kříbek B. Czech Geological Survey; Windhoek, Namibia: 2012. Environmental and Health Impacts of Mining in Africa: Proceedings of the Annual Workshop IGCP/SIDA No. 594. [Google Scholar]

- Marlow R.J. Presented at the Water Resources Management Conference; USA: 1999. Agriculture Water Use Efficiency in the United States; pp. 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- McGrane S.J. Impacts of urbanisation on hydrological and water quality dynamics, and urban water management: a review. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2016;61(13):2295–2311. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen M.M., Hoekstra A.Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2016;2(2) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mguni B.S. Botswana; 2019. International Merchandise Trade Statistics; pp. 1–20.https://www.statsbots.org.bw/sites/default/files/publications/International%20Merchandise%20Trade%20Statistics%20%20April%202019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Moran P.A.P. Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika. 1950;37(1/2):17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugagga F., Nabaasa B.B. The centrality of water resources to the realization of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). A review of potentials and constraints on the African continent. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2016;4(3):215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Muller M. Water Integrity Network/Corruption watch; 2020. Money Down the drain: Corruption in South Africa’s Water Sector. A Water Integrity Network Corruption Watch Report.https://www.corruptionwatch.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/water-report_2020-single-pages-Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Musah M., Kong Y., Mensah I.A., Antwi S.K., Donkor M. The link between carbon emissions, renewable energy consumption, and economic growth: a heterogeneous panel evidence from West Africa. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2020;27(23):28867–28889. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-08488-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Development Planning Commission . Accra; Ghana: 2019. National Development Planning Commission. “GHANA: Voluntary National Review Report on the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; pp. 1–127. [Google Scholar]

- Neafie J. The role of foreign direct investment (FDI) in promoting access to clean water. Politikon: IAPSS J. Politic. Sci. 2018;39:7–35. [Google Scholar]

- Odiwuor K. Africa, Corruption Dirties the Water. 2013. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2013/03/14/africa-corruption-dirties-water

- OEC . 2020. Botswana.https://oec.world/en/profile/country/bwa [Google Scholar]

- Ola-David O. Working Paper. Department of Economics and Development Studies. Covenant University; 2013. Making FDI work for sustainable development: the role of institutions. [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z., Wang Y., Zhou Y., Wang Y. Analysis of the water use efficiency using super-efficiency data envelopment analysis. Appl. Water Sci. 2020;10(6):139. [Google Scholar]

- Poumanyvong P., Kaneko S. Does urbanization lead to less energy use and lower CO2 emissions? A cross-country analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2010;70(2):434–444. [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot R., Kelley S. WWF; Australia: 2017. Can Technology Save the Planet?https://www.wwf.org.au/ArticleDocuments/360/pub-can-technology-save-the-planet [Google Scholar]

- Russo T., Alfredo K., Fisher J. Sustainable water management in urban, agricultural, and natural systems. Water. 2014;6(12):3934–3956. [Google Scholar]

- Stålgren P. Swedish Water House Policy Brief. Vol. 4. Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI); Sweden: 2006. Corruption in the water sector: causes, consequences, and potential reform.http://hdl.handle.net/10535/5135 [Google Scholar]

- Sun D., Addae E.A., Jemmali H., Mensah I.A., Musah M., Mensah C.N., Appiah-Twum F. Examining the determinants of water resources availability in sub-Sahara Africa: a panel-based econometrics analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2021;28(17):21212–21230. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-12256-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transparency International World water day: corruption in the water sector’s costly impacts. World water day: corruption in the water sector’s costly impacts. 2016. https://www.transparency.org/en/news/world-water-day-corruption-in-the-water-sectors-costly-impact

- U. S. Department of Commerce . 2020. United States Country Commercial Guides, Chad.https://www.export-u.com/CCGs/2020/Chad-2020-CCG.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program . Gabon: Special Unit for South-South Cooperation; 2012. Gabon, Nationwide Water & Power; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, African Union Commission, & African Development Bank . 2003. Africa Water Vision for 2025 : Equitable and Sustainable Use of Water for Socioeconomic Development.https://hdl.handle.net/10855/5488 [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg C., Danilenko A. 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433. The World Bank Group; 2017. Performance of Water Utilities in Africa (Pp. 1–171)https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/26186/113075-WP-P151799-PUBLIC-WeBook.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Liu H., Wang C., Bai Y., Fan L. A study of industrial relative water use efficiency of Beijing: an application of data envelopment analysis. Water Pol. 2019;21(2):326–343. [Google Scholar]

- Wang N., Choi Y. Challenges for sustainable water use in the urban industry of Korea based on the global non-radial directional distance function model. Sustainability. 2019;11(14):3895. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Zhou L., Wang H., Li X. Water use efficiency and its influencing factors in China: based on the data envelopment analysis (DEA)-Tobit model. Water. 2018;10(7):832. [Google Scholar]

- WDI . The World Bank; 2020. World Development Indicators (Data Bank) [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2021. Nigeria: Ensuring Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for All.https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/05/26/nigeria-ensuring-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-for-all [Google Scholar]

- Xu R., Wu Y., Wang G., Zhang X., Wu W., Xu Z. Evaluation of industrial water use efficiency considering pollutant discharge in China. PLoS One. 2019;14(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y., Ivanovski K., Inekwe J., Smyth R. Human capital and energy consumption: evidence from OECD countries. Energy Econ. 2019;84 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Zhuang Y., Chiu Y., Pang Q., Chen Z., Shi Z. Measuring urban integrated water use efficiency and spatial migration path in China: a dynamic two-stage recycling model within the directional distance function. J. Environ. Manag. 2021;298 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Sun C., Liu F. Interprovincial two-stage water resource utilization efficiency under environmental constraint and spatial spillover effects in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017;164:715–725. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Zhang H., Xing Z. Re-examining regional total-factor water efficiency and its determinants in China: a parametric distance function approach. Water. 2018;10(10):1286. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Wu H., Song P. Measuring the resource and environmental efficiency of industrial water consumption in China: a non-radial directional distance function. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;240 [Google Scholar]

- Zomorrodi A., Zhou X. Impact of FDI on environmental quality of China. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017;4(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.