Abstract

Some medically important viruses―including retroviruses, flaviviruses, coronaviruses, and herpesviruses―code for a protease, which is indispensable for viral maturation and pathogenesis. Viral protease inhibitors have become an important class of antiviral drugs. Development of the first-in-class viral protease inhibitor saquinavir, which targets HIV protease, started a new era in the treatment of chronic viral diseases. Combining several drugs that target different steps of the viral life cycle enables use of lower doses of individual drugs (and thereby reduction of potential side effects, which frequently occur during long term therapy) and reduces drug-resistance development. Currently, several HIV and HCV protease inhibitors are routinely used in clinical practice. In addition, a drug including an inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 main protease, nirmatrelvir (co-administered with a pharmacokinetic booster ritonavir as Paxlovid®), was recently authorized for emergency use. This review summarizes the basic features of the proteases of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and SARS-CoV-2 and discusses the properties of their inhibitors in clinical use, as well as development of compounds in the pipeline.

1. Antivirals

Established and emerging viruses cause a wide range of illnesses (McArthur, 2019). Unlike bacteria, viruses replicate solely intracellularly and rely on the synthetic machinery of the host cell. Thus, development of drugs targeting viruses without affecting the host cell is challenging (Kausar et al., 2021).

Idoxuridine was the first antiviral drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1963. This compound is a nucleoside analogue, which targets synthesis of herpesviral DNA (Maxwell, 1963; Prusoff, 1959). Other drugs with a similar mechanism of action followed, including the widely used acyclovir (De Clercq and Li, 2016; Elion et al., 1977; Furman et al., 1981; Hermans and Cockerill, 1983). These nucleoside analogues enter the cell, where they are phosphorylated. Subsequently, such phosphorylated drugs can block viral DNA or RNA polymerases from intracellular synthesis of the functional viral genome. Viral polymerases are less specific than mammalian polymerases, which means that in many cases, a nucleoside derivative designed against one viral polymerase also acts against several others (Kataev and Garifullin, 2021). Due to viral polymerase promiscuity, nucleoside drugs can be considered broad-spectrum, or “less-narrow-spectrum” antivirals. This attribute is beneficial for drug repurposing, an emerging drug discovery strategy in which approved or investigational drugs are used for a condition different to their original medical indications. Recent examples of drug repurposing include remdesivir and molnupiravir. These compounds were originally developed as anti-HCV, anti-Ebola or anti-influenza drugs but are now used to treat the SARS-CoV-2 infection (de Wit et al., 2020; Kabinger et al., 2021; Sheahan et al., 2017; Toots et al., 2019, 2020; Warren et al., 2016; Williamson et al., 2020). The major disadvantage of nucleoside analogues is their potential toxicity and mutagenicity for the host cells (Wutzler and Thust, 2001; Zhou et al., 2021). Off-target actions are particularly problematic in the treatment of chronic infections, when the drugs must be administered for a prolonged period of time. Development of structurally diverse antivirals with a better safety profile, which also retain activity against drug-resistant viral variants, has become of primary interest (Bean, 1992; Kuroki et al., 2021; Meganck and Baric, 2021). These needs have turned the attention of researchers to compounds with new mechanisms of action.

The first antiviral compound with a completely new mechanism of action was saquinavir, a peptidomimetic inhibitor of HIV protease (Craig et al., 1991; James, 1995; Roberts et al., 1990). Other inhibitors of viral proteases and compounds targeting various steps of viral infection followed (De Clercq, 2004). The availability of compounds with different mechanisms of action (Matthew et al., 2021) enables several steps of the viral replication cycle to be targeted simultaneously. Such combination therapies can be more efficient and safer, as concomitantly administrated low doses can induce antiviral action while reducing the side effects (Hézode, 2018; Paredes and Clotet, 2010).

Nevertheless, all compounds in current clinical use are virostatic drugs that stop further viral replication, but cannot eliminate viral particles that have already been formed (Pankey and Sabath, 2004; Sutton et al., 2021). Due to the inherent nature of virostatic drugs, antivirals have to be administered in the early phases of acute viral infection to minimize the viral load in the infected individual (Dunning et al., 2020; Mehta et al., 2021).

2. Viral polyprotein processing

Some viruses express their proteins in the form of a polyprotein containing one or more proteases. Such proteases autocatalytically release themselves from the precursor and cleave the remaining parts of the polyprotein into functional proteins. Inhibition of this proteolytic activity can block production of infectious viral progeny and reduce pathogenic processes (Han et al., 1995; Schneider and Kent, 1988; Seelmeier et al., 1988; Tsu et al., 2021). All positive single-stranded RNA viruses and some DNA viruses belong to this group (see Table 1 for summary). Examples of clinically important inhibitors of viral proteases include inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) proteases (Skwarecki et al., 2021). In addition, the FDA recently authorized an inhibitor of the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 (Hammond et al., 2022; Owen et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Medically important families of viruses (Siegel, 2018) coding for one or more proteases.

| Family | Genus | Examples of viruses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive single-stranded RNA viruses, enveloped | Retroviridae | Lentivirus | HIV-1, HIV-2, HTLV-1, HTLV-2 |

| Flaviviridae | Flavivirus | Dengue virus, Zika virus, yellow fever virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, West Nile virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus | |

| Hepacivirus | Hepatitis C virus | ||

| Coronaviridae | Coronavirus | SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV, OC43,32 229E, NL63,33, HKU134 | |

| Togaviridae | Rubivirus | Rubeola virus | |

| Alphavirus | Chikungunya virus | ||

| Positive single-stranded RNA viruses, non-enveloped | Picornaviridae | Enterovirus | Polio virus, rhinoviruses, coxsackieviruses, echoviruses |

| Hepatovirus | Hepatitis A virus | ||

| Hepeviridae | Hepevirus | Hepatitis E virus | |

| Caliciviridae | Norovirus | Noroviruses causing gastroenteritis | |

| Sapovirus | Sapoviruses causing gastroenteritis | ||

| Negative single-stranded RNA viruses, enveloped | Nairoviridae | Orthonairovirus | Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus |

| Double-stranded DNA viruses, enveloped | Herpesviridae | Simplexvirus | Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 |

| Varicellovirus | Varicella-zoster virus | ||

| Cytomegalovirus | Cytomegalovirus | ||

| Rhadinovirus | Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus | ||

| Poxviridae | Orthopoxvirus | Small pox virus | |

| Double-stranded DNA viruses, non-enveloped | Adenoviridae | Mastadenovirus | Human adenoviruses 1-57 |

Some RNA and DNA viruses cannot be targeted by protease inhibitors, as they exploit different strategies, such as alternative mRNA splicing, to express several proteins from one RNA molecule (Ho et al., 2021). These include negative single-stranded RNA viruses (Payne, 2017), such as influenza viruses (Majerová et al., 2010), Lassa virus, Marburg virus, morbillivirus, mumps virus, lyssavirus, and vesicular stomatitis virus (Trovato et al., 2020); double-stranded RNA viruses including rotaviruses; and certain DNA viruses, such as papillomaviruses (Graham, 2017) and polyomaviruses (Saribas et al., 2019).

3. HIV and anti-HIV therapy

HIV is the retrovirus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (Barré-Sinoussi et al., 1983; Gallo et al., 1983; Sharp and Hahn, 2011). There are two types of HIV – HIV-1 and HIV-2 – with HIV-2 being less transmissible and less virulent than HIV-1. While HIV-1 is spread worldwide, HIV-2 is confined mainly to West Africa (Clavel et al., 1986). Other medically significant retroviruses include endemic human T-lymphotropic viruses (Gallo et al., 1981). Human DNA also harbors fragments of ancient retroviruses, some of which are partially retained as functional genes (Grandi and Tramontano, 2018; Lander et al., 2001).

Retroviruses utilize two important enzymes supporting their unique replication cycle: reverse transcriptase, which copies viral genomic RNA into DNA, and integrase, which integrates this DNA (called proviral DNA) into the host cell genome. As cells divide, the integrated proviral DNA remains a part of the genome of newly arising cells. Proliferating host cells, such as CD4+ T-cells, with integrated proviral DNA, form the latent HIV reservoir (Chun et al., 1995; Morcilla et al., 2021). Because the integrated proviral DNA becomes part of the host cell genome, it cannot be removed by commonly used antivirals. Recently, in animal models, integrated provirus was removed from the host cell genome using the genome-editing technology CRISPR/Cas9 (Dash et al., 2019; Mancuso et al., 2020). These promising results led to initiation of an early-stage clinical trial, announced by Excision BioTherapetics in September 2021 (Excision; https://www.excision.bio/technology). Another potentially promising approach involves activation of latent virus reservoirs combined with active elimination of virus-producing cells (recently reviewed in (Ward et al., 2021)).

Although antiretroviral therapy currently cannot eliminate proviral DNA from the genome, it averts development of AIDS. The first anti-HIV drug – 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT or zidovudine) – is a nucleoside chain terminator of viral reverse transcription (De Clercq, 1987; Mitsuya et al., 1985; Robins and Robins, 1964). After FDA approval of AZT in 1987, other compounds with the same mechanism of action followed (Broder, 2010). A novel mechanism of action – HIV protease inhibition – was introduced by the development of saquinavir (Invirase®), which was approved by the FDA in 1995 (Craig et al., 1991; James, 1995; Roberts et al., 1990). This enabled simultaneous use of nucleosides targeting reverse transcription and protease inhibitors blocking viral maturation. Simultaneously targeting these two steps of the viral life cycle led to a decrease of viremia below a detectable level, followed by an increase in CD4+ T-cell count to a normal level. This approach started a new era in anti-HIV therapy: HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy; today referred to as cART or ART) (Smart, 1995).

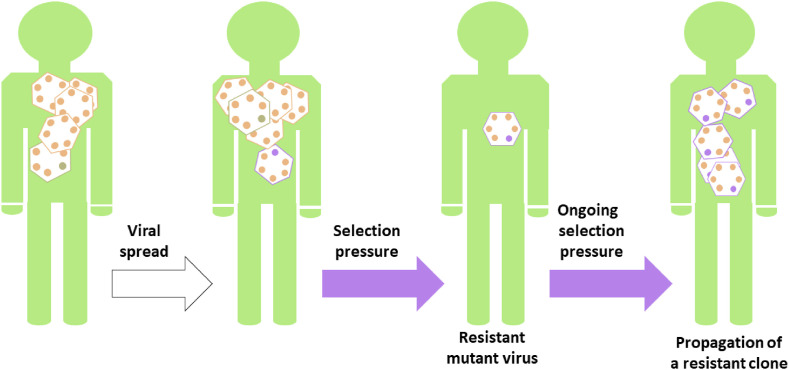

Subsequently, inhibitors with other mechanisms of action have been approved: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, integrase inhibitors, and compounds blocking the initial steps of the viral life cycle (enfuvirtide, maraviroc, fostemsavir, and the anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody ibalizumab) (Tseng et al., 2015; Weichseldorfer et al., 2021). At present, a wide range of drug combinations is available to achieve maximal antiviral effect while minimizing the side effects. However, the risk of development of drug-resistant viral variants still persists (Fig. 1 ). Although the drug-resistant variants are usually less viable, other compensatory mutations can restore viral fitness. In addition, the number of compensatory mutations likely decreases the probability of reappearance of revertant mutants when therapy is discontinued (Zhang et al., 2020b). HIV subtypes have different virulence and drug susceptibility (Spira et al., 2003). Potential differences in virulence among drug-resistant variants have yet to be described.

Fig. 1.

A simplified schematic representation of drug resistance development: Due to errors randomly incorporated into the viral genome during viral replication, mutated viral variants continuously evolve. Most mutations are lethal for the virus or neutral. When the virus is under selection pressure (e.g., a person is treated by an antiviral drug), only viral variants able to circumvent the action of the drug can produce a new viral progeny.

3.1. HIV protease

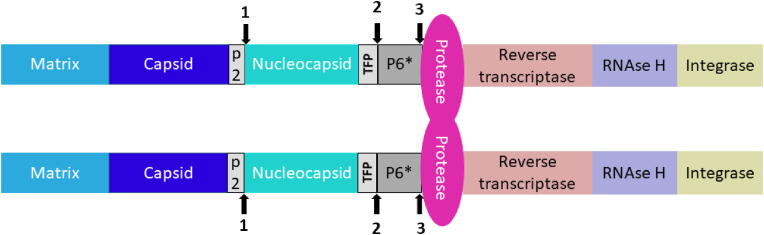

HIV expresses its proteins as the Gag-Pol polyprotein (Fig. 2 ). While Gag region bears viral structural proteins, Pol contains viral enzymes (protease, reverse transcriptase, RNase H, and integrase). During translation, either only the Gag region or the entire Gag-Pol polyprotein is synthesized. Synthesis of the whole Gag-Pol polyprotein is enabled by suppression of the stop codon between the Gag and Pol regions by a −1 frameshift at a specific mRNA site (Jacks et al., 1988). This process is precisely regulated and occurs in 5% of cases, as this ratio of Gag to Gag-Pol is crucial for efficient virus assembly, genome packaging, and maturation (Shehu-Xhilaga et al., 2001). Gag and Gag-Pol are myristoylated at the N-terminus by the host cell machinery. These myristoyl tags enable anchoring of the Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins into the cell membrane (Hermida-Matsumoto and Resh, 1999), which gives rise to the sites of viral assembly. The viral genomic RNA is subsequently recruited to these sites, followed by formation of immature viral particles and their budding from the cell. To be able to infect new host cells, viral particles released from the cell of origin must undergo maturation, during which Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins are cleaved by HIV protease into functional proteins (Katsumoto et al., 1987; Tabler et al., 2022).

Fig. 2.

A schematic representation of initial cleavage sites in HIV Gag-Pol polyprotein cleaved by HIV protease in cis (intramolecularly). The Gag region harbors viral structural proteins (matrix, capsid and nucleocapsid), whereas viral enzymes are expressed in the Pol region. Each Gag-Pol polyprotein bears one monomer of HIV protease, which must form a homodimer to be catalytically active. The numerals 1, 2 and 3 denote the order of cis-cleavage events.

HIV protease is an aspartic protease, active only as a homodimer. Each monomeric subunit provides one catalytic Asp-Ser-Gly triad to form the active site. Gag and Gag-Pol cleavage by HIV protease must be preceded by autoactivation of the protease, resulting in its release from the Gag-Pol precursor. The initial cuts occur exclusively in cis, i.e. intramolecularly (Pettit et al., 2004) (Fig. 2). The cleavage sites are upstream of the N-terminus of HIV protease – between the p2 peptide and the nucleocapsid, and between the trans-frame octapeptide (TFP) and the p6*peptide. Then, the free N-terminus of HIV protease is released from the precursor by cleaving out the p6*peptide (Pettit et al., 2003, 2004). The subsequent cleavages of the Gag and Gal-Pol polyprotein by HIV protease occur in trans (intermolecularly) (Pettit et al., 2005).

Once the viral polyproteins are cleaved by HIV protease in the process of maturation, the virus becomes infectious and can attack a new host cell (Kohl et al., 1988; Tabler et al., 2022). For successful maturation, the proteolysis of viral polyproteins must be perfectly timed. This was demonstrated experimentally by adding a protease inhibitor during viral assembly and subsequently removing it from purified immature virions. While cleavage of Gag and Gag-Pol was restored after the inhibitor was removed, the viral particles remained noninfectious (Mattei et al., 2014). Indeed, inhibitors of HIV protease are capable of locking viral particles in a noninfectious immature state and thus play a crucial role in current anti-HIV treatment (Konvalinka et al., 2015).

Interestingly, release of HIV protease from the Gag-Pol polyprotein prior to virion assembly results in decreased production of viral particles and might lead to elimination of infected cells due to the cytotoxicity of HIV protease (Jochmans et al., 2010; Kaplan and Swanstrom, 1991; Kräusslich, 1991; Majerová and Novotný, 2021; Pan et al., 2012; Sudo et al., 2013; Trinité et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). A drug that would be able to provoke this premature release of HIV protease from Gag-Pol could potentially eliminate host cells with integrated proviral DNA in the genome. This would represent a complete cure of HIV infection.

3.1.1. Inhibitors of HIV protease

Inhibitors of HIV protease are important components of ART. A typical initial ART regimen consists of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and one integrase inhibitor or protease inhibitor. The regimen is usually modified over the course of therapy due to development of adverse drug reactions or drug resistance (Vitoria et al., 2019). Adverse events include gastrointestinal problems and hyperlipidemia (except for atazanavir), hepatic problems (mainly ritonanir, tipranavir, darunavir), rash (amprenavir, tipranavir, darunavir), hyperbilirubinemia (indinavir, atazanavir), paresthesia (ritonavir, amprenavir), nephrolithiasis (indinavir, atazanavir), retinoid-like effects (indinavir) (Boesecke and Cooper, 2008), cardiovascular problems (Alvi et al., 2018), and reversible inhibition of insulin secretion (mainly indinavir; also amprenavir, nelfinavir, and ritonavir) (Koster et al., 2003; Pokorná et al., 2009).

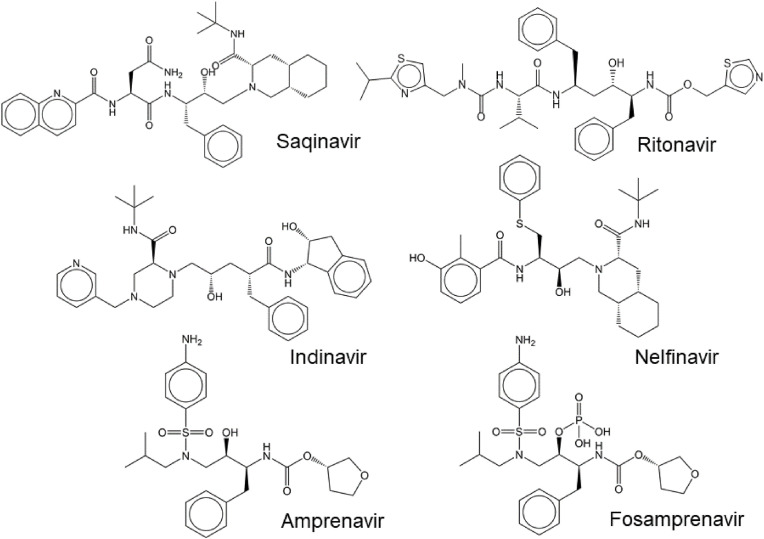

3.1.1.1. First-generation HIV protease inhibitors

The first-generation HIV protease inhibitors primarily targets the active site. They bind reversibly into the substrate pocket of the enzyme, hindering binding of substrates. Most of these inhibitors are peptidomimetics derived from natural cleavage sites. They include saquinavir, ritonavir, indinavir, nelfinavir, amprenavir, and fosmaprenavir (Ghosh et al., 2016) (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Structures of the first-generation inhibitors of HIV protease in clinical use.

The peptidomimetic structure of the first-in-class drug saquinavir (Invirase®, Fortovase®) was inspired by the Tyr-Pro cleavage sites naturally occurring in the Gag-Pol polyprotein; the scissile bond is replaced with an uncleavable hydroxyethylamine transition state mimetic. Saquinavir interacts with all subsites of the substrate binding cavity (Craig et al., 1991; Thompson et al., 1993). As Tyr-Pro substrates are atypical for mammalian proteases, the inhibitors derived from unique structures are anticipated to be specific for viral proteases, reducing off-target activities against host proteolytic enzymes (Jacobsen et al., 1995; Roberts et al., 1990).

Ritonavir (Norvir®) was approved by the FDA as a second HIV protease inhibitor in 1996 (Kempf et al., 1995). However, high doses of ritonavir cause strong gastrointestinal side effects, as ritonavir also potently inhibits the 3A4 isoenzyme of hepatic cytochrome P-450. Inhibition of cytochrome P-450 3A4 blocks metabolism of many drugs, including HIV protease inhibitors, and thus leads to increased plasma levels of these drugs (Kumar et al., 1996). This surprising observation lead to the development of new class of compounds, inhibitors of cytochromes P450 that can be used as general “boosters” improving of therapeutics with compromised serum half-life, including HIV protease inhibitors. Ritonavir became “first in class” of these boosters (Hakkola et al., 2020; Kempf et al., 1997).

Another example of a pharmacokinetic booster used in anti-HIV therapy is cobicistat, which also inhibits cytochrome P-450 3A4 but does not inhibit HIV protease (Elion et al., 2011; Mathias et al., 2010). Moreover, cobicistat is more specific to the P-450 3A4 isoenzyme and does not interact with other cytochrome isoenzymes to much extent. It is thus a preferred choice of pharmacokinetic booster in newer drug formulations. However, in contrast to ritonavir, cobicistat may influence serum creatinine and is less suitable for use in pregnancy (Nguyen et al., 2016; Sherman et al., 2015). The effectiveness of some compounds is not improved equally by addition of cobicistat or ritonavir. For instance, tipranavir is boosted by ritonavir more effectively than by cobicistat (Ramanathan et al., 2016).

Indinavir (Crixivan®), the next HIV protease inhibitor to be approved by the FDA, in 1996, was developed based on the structure of experimental renin inhibitors (Churchill, 1996; Vacca et al., 1994). Researchers screened a library of renin inhibitors to provide a lead peptide structure for HIV protease inhibition. A small modification of the lead molecule (removal of N-terminal phenylalanine) resulted in a compound lacking anti-renin activity, but retaining anti-HIV activity (Vacca et al., 1991). The compound was further modified to improve its pharmacokinetic properties (Vacca et al., 1994). However, indinavir has a very short half-life (1.8 h) under physiological conditions and thus requires frequent administration (Churchill, 1996).

Nelfinavir (Viracept®), approved by the FDA in 1997, is the first nonpeptidic HIV protease inhibitor obtained by rational, iterative, structure-based design combined with pharmacokinetic optimizations (Gehlhaar et al., 1995; Kaldor et al., 1997; Shetty et al., 1996). Nelfinavir shares some structural features with saquinavir, including a 2-quinoline-carboxamide moiety (Fig. 3) (Ghosh et al., 2016).

Amprenavir (Agenerase®) was approved by the FDA in 1999 to treat HIV infection (Kim et al., 1995; Miller, 1999; Murphy et al., 1999). This compound was again developed based on modified experimental renin inhibitors. It contains a sulfonamide moiety and a hydroxyethylamine isostere, which serves to mimic the transition state (Kim et al., 1995). To improve the pharmacokinetics a hydrophilic phosphate ester of amprenavir―fosamprenavir (Lexiva®) ―was developed as a prodrug and introduced into clinical use in 2003. During absorption in the gut, fosamprenavir is converted to amprenavir by host phosphatases (Furfine et al., 2004; Wire et al., 2006).

3.1.1.2. Drug resistance development

The first generation of HIV protease inhibitors suffered from suboptimal pharmacokinetics, requiring administration of high doses of the drugs several times per day (van Heeswijk et al., 2001). This dosing reinforced the side effects of these drugs, leading to health problems that have sometimes required changes in the treatment regimen and/or caused poor adherence. Consequently, suboptimal dosing accelerated the development of drug-resistant viral variants, which became an important problem in anti-HIV therapy (Pokorná et al., 2009).

Due to the reverse transcription step, replication of HIV continuously gives rise to mutated variants. Retroviral reverse transcriptase lacks proofreading activity and introduces mutations into nascent proviral DNA at a frequency of 1 error per 1,700–4,000 bases, i.e. 2 to 6 errors per each HIV-1 genome molecule. The errors are not distributed equally and are more frequent in mutation hotspots (Preston et al., 1988; Roberts et al., 1988), which are likely delineated by the 3D structure of the viral template genetic information. Most mutations in coding regions are deleterious or neutral (they do not influence the function of a mutated protein). Occasionally, mutations that confer an advantage to the virus appear. Viruses with such mutations can produce viral progeny more efficiently, and the viral population becomes gradually enriched with such variants. In some cases, a mutation can only be beneficial under certain conditions, such as in the presence of a drug (Nijhuis et al., 2009) (Fig. 1).

Complete blockade of production of viral progeny during ART is crucial, as suboptimal drug concentrations lead to selection and replication of drug-resistant viral variants. Interestingly, mutations that originate under selection pressure do not necessarily have to result in increased HIV protease activity, as even minor HIV protease activity is sufficient for production of infectious viral progeny. This was demonstrated with an active site mutant of HIV protease, in which a threonine adjacent to the catalytic aspartate was replaced with a serine. Even though the purified mutant protease had one-order-of-magnitude lower activity than the wild type, the virus bearing this mutant protease showed no significant differences in polyprotein cleavage, infection kinetics, and titer compared with the wild-type virus (Konvalinka et al., 1995). Similarly, some drug-resistant HIV protease mutants show lower activity in vitro, while the infectivity of viruses bearing these protease variants remains unchanged (Weber et al., 2002).

The first-generation HIV protease inhibitors share some structural features and target similar binding sites (Fig. 3). It is therefore not surprising that the development of drug resistance under selection pressure of one inhibitor usually causes cross-resistance to one or more other inhibitors. Fortunately, the genetic drug resistance barrier is quite high, i.e., a virus usually needs to accumulate several mutations to become resistant to a drug (Chang and Torbett, 2011; Shah et al., 2020; Weikl and Hemmateenejad, 2020). Interestingly, the mutations that confer resistance to HIV protease inhibitors do not occur only within the active site of the protease but also in other parts of the Gag-Pol polyprotein, mainly in the polyprotein cleavage sites. This brings even greater complexity to the problem of anti-HIV drug resistance (Aoki et al., 2009; Kozísek et al., 2012; Nijhuis et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 1997).

Characteristic primary drug-resistance-conferring mutations developed under the selection pressure of saquinavir include G48V and L90M (Jacobsen et al., 1995). The D30N mutation arises with nelfinavir treatment (Kožíšek et al., 2007; Patick et al., 1998). Amprenavir/fosamprenavir treatment can lead to M46I/L, I47V, I50L, I54 L/V, and I84V variants (Arabi et al., 2021; Marcelin et al., 2004). The mutations M46L/I and V82A arise upon treatment with indinavir, later followed by a mutation at either I54V or A71 V/T (Zhang et al., 1997). Typical mutations that confer cross-resistance include M46I/L, I47V, G48V, V82 A/T, I84V, and L90M (Svicher et al., 2005). Cross-resistance to saquinavir and ritonavir or to nelfinavir and indinavir is common (Majerová-Uhlíková et al., 2006; Pawar et al., 2018; Shah et al., 2020).

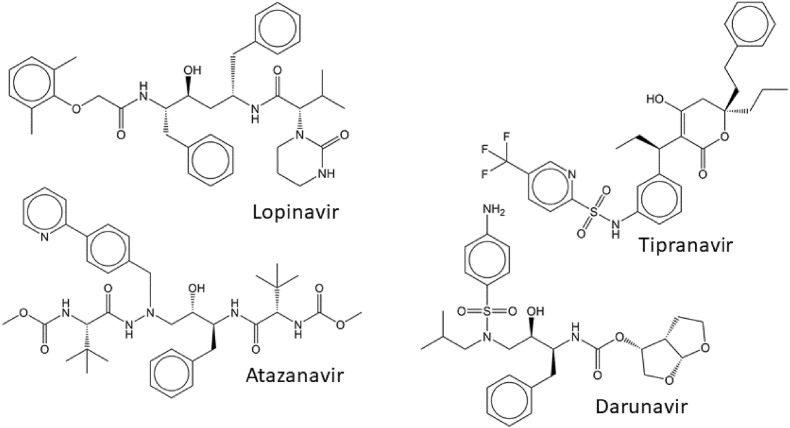

3.1.1.3. Second-generation HIV protease inhibitors

Rapid development of drug resistance to first-generation HIV protease inhibitors led to efforts to design drugs with higher barriers to resistance development. Second-generation inhibitors of HIV protease were designed to form fewer binding contacts with non-conserved residues prone to mutations and more binding contacts with the backbone of the enzyme and conserved residues (Ghosh et al., 2008). The latter includes interactions beyond the active site cavity of the enzyme, namely with the flaps of HIV protease (Weber et al., 2015). Additionally, the enthalpic and entropic contributions of the protease-inhibitor interaction were optimized, and attempts were made to improve the pharmacokinetic profiles of the new compounds (Ghosh et al., 2016; Majerová and Konvalinka, 2021; Wensing et al., 2010). Second-generation inhibitors include lopinavir, tipranavir, atazanavir, and darunavir (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Structures of the second-generation inhibitors of HIV protease.

Lopinavir (Kaletra®) was approved by the FDA in 2004. Its structure was derived from ritonavir and modified to minimize contacts with Val82 of HIV protease, a residue inside the substrate-binding pocket that is critical in drug resistance development. Lopinavir was the first HIV protease inhibitor co-administered with the pharmacokinetic booster ritonavir (Sham et al., 1998; Vogel and Rockstroh, 2005). The main mutations associated with failure of lopinavir treatment are K20 M/R and F53L. These mutations, in combination with other compensatory mutations, dramatically decrease the protease's sensitivity to lopinavir (Kempf et al., 2001). Other lopinavir-resistance-conferring mutations include L76V, Q58E, L90M, and I54V (Champenois et al., 2011). Some mutations that evolve under the selection pressure of lopinavir even result in sub-optimal binding of some first-generation HIV protease inhibitors. For example, the I47A mutation causes a 100-fold decrease in sensitivity to lopinavir as well as resistance to amprenavir/fosamprenavir. Interestingly, it also leads to hyper-susceptibility to saquinavir (de Mendoza et al., 2006; Sasková et al., 2008, 2009).

Tipranavir (Aptivus®), which the FDA approved in 2005, is based on the nonpeptidic compound phenprocoumon, which was identified as a lead structure during compound library screening for inhibition of HIV protease. Tipranavir has no amide group but contains one sulfonamide moiety. Unlike other inhibitors of HIV protease, tipranavir not only binds to the substrate pocket of the enzyme (Thaisrivongs et al., 1996; Thaisrivongs and Strohbach, 1999), but also blocks HIV protease dimerization (Aoki et al., 2012). Tipranavir is a strong inducer of cytochrome P450 and is thus co-administered with higher doses of the pharmacokinetic booster ritonavir (Morello et al., 2007).

Tipranavir retains a high activity against drug-resistant variants of HIV protease. Loss of sensitivity to tipranavir is accompanied by loss of sensitivity to other specific HIV protease inhibitors, except saquinavir. Decreased susceptibility to tipranavir has been reported for viral variants accumulating different combinations of the HIV protease mutations L10F, I13V, V32I, L33F, M36I, K45I, I54V, A71V, V82L, and I84V, as well as one cleavage site within the Gag polyprotein. These tipranavir-resistant variants have lower replicative capacity (Doyon et al., 2005).

Atazanavir (Reyataz®), which the FDA approved in 2003, is an azapeptide inhibitor with a long half-life (Bold et al., 1998; Piliero, 2002). It can be administered once per day with cobicistat (Evotaz®) or without a pharmacokinetic booster (von Hentig, 2008). As atazanavir is both a substrate and inhibitor of cytochrome P450, its administration increases plasma levels of some other drugs, including other HIV protease inhibitors, statins, warfarin, and drugs used to treat gastric ulcers (Busti et al., 2004). The I50L mutation is a hallmark of drug resistance to atazanavir (Goldsmith and Perry, 2003).

Darunavir is the most recently developed FDA-approved protease inhibitor, which was approved for single-agent administration in 2006 (Prezista®) (Ghosh et al., 2007; Koh et al., 2003). Additionally, darunavir is available in combinations with cobicistat (Prezcobix®) or cobicistat and two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (Symtuza®) (Rittweger and Arastéh, 2007). The structure of darunavir resembles that of amprenavir, as it contains a sulfonamide moiety and hydroxyethylamine, which mimics the transition state of the substrate cleavage (Fig. 4). In contrast to amprenavir, darunavir also contains a bis-tetrahydrofuranyl group at its N-terminus, which mediates hydrogen bonding with the backbone of the enzyme in the vicinity of residues Asp29 and Asp30, mimicking conserved enzyme-substrate bonds (Koh et al., 2003). While darunavir primarily binds to the HIV protease active site, a secondary binding site blocking HIV protease dimerization has been reported (Hayashi et al., 2014). Darunavir also seems to have a high affinity to the precursor form of HIV protease. In fact, inhibition of HIV protease in its noncleaved precursor form has been observed for other inhibitors, but it required much higher (several orders of magnitude) doses of the drugs. Darunavir has the highest affinity to the precursor form of all inhibitors in clinical use, possibly because of the contribution of the secondary binding site (Davis et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2019; Humpolíčková et al., 2018; Louis et al., 2011; Park et al., 2016). Although darunavir has a high barrier to drug-resistance development, darunavir-resistant variants accumulating over 20 mutations have been reported (Kožíšek et al., 2014; Sasková et al., 2009) (Fig. 5 ). The hallmark mutations are V11I, V32I, L33F, I47V, I50V, I54 L/M, G73S, L76V, I84V, and L89V (Tremblay, 2008).

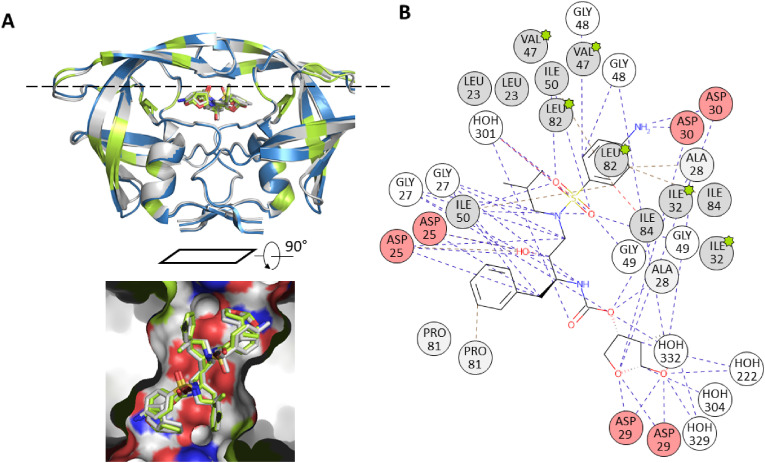

Fig. 5.

A. Superimposition of the wild type (blue, pdb structure 4LL3) and a darunavir-resistant mutant of HIV-1 protease homodimer, pdb code 3TTP (Kožíšek et al., 2014). The 3TTP structure is grey, mutated positions are marked in green, RMSD between the structures was calculated as 0.49 Å. The inset shows the inhibitor in the substrate binding site using protein surface representation. The surface color denotes hydrophobic (grey) and hydrophilic (red and blue) atoms of amino acid residues. B. 2D interaction diagram of darunavir bound to the dimeric HIV-1 protease (pdb structure 3TTP). Mutated residues are marked with the green stars. The figures were generated using PyMol (Schrödinger and DeLano, 2020) and the PDBe application (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/entry/pdb/3TTP). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.1.1.4. Drugs with non-canonical mechanisms of action targeting HIV protease

Some non-nucleoside HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors are also able to trigger premature release of HIV protease out of the Gag-Pol polyprotein. Rilpivirine, efavirenz, and etravirine can bind to the reverse transcriptase domain of the Gag-Pol precursor and enhance dimerization of two Gag-Pol molecules, bringing together their protease domains. This dimerization then results in autocatalytic release of HIV protease from the Gag-Pol precursor prior to assembly of new virions. This leads to decreased production of viral particles. At the same time, HIV protease is cytotoxic and its presence within the host cell could lead to elimination of infected cells harboring integrated proviral DNA (Jochmans et al., 2010; Kaplan and Swanstrom, 1991; Kräusslich, 1991; Majerová and Novotný, 2021; Pan et al., 2012; Sudo et al., 2013; Trinité et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). Although this phenomenon has been observed in cell culture experiments with such high doses of non-nucleoside HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors that cannot be reached in vivo, it nevertheless represents an interesting proof-of-principle of a potential approach to causative cure of HIV infection.

3.1.1.5. Repurposing of HIV protease inhibitors

Some evidence suggests that HIV protease inhibitors could be beneficial for treatment of Kaposi sarcoma; however, the reports are contradictory and further research is needed (Lebbé et al., 1998; Palich et al., 2021; Subeha and Telleria, 2020). Nelfinavir has been studied for its potential anticancer effect (Allegra et al., 2020; Subeha and Telleria, 2020), as it interferes with the cell cycle (Brüning et al., 2010; Chow et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2012) and proteasomal degradation (Fassmannová et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2020); affects signal transduction pathways (Subeha and Telleria, 2020) and mitochondrial processes (Deng et al., 2010; Utkina-Sosunova et al., 2013); and induces cell death (Bissinger et al., 2015; Kawabata et al., 2012), endoplasmic reticulum stress (Okubo et al., 2018), and autophagy (Gills et al., 2008; Xia et al., 2019). Nelfinavir also interferes with late steps of adenovirus and herpesvirus replication in vitro, but it does not affect adenoviral cysteine protease or herpes serine protease (Georgi et al., 2020; Kalu et al., 2014). Similarly, lopinavir could act against papillomaviruses through its interactions with host targets (Barillari et al., 2018; Batman et al., 2011; Loharamtaweethong et al., 2019; Zehbe et al., 2011).

Recently, HIV protease inhibitors have been studied as potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 drugs. Even though SARS-CoV-2 harbors two proteases, neither has a specificity or mechanism of action resembling that of HIV protease. Thus, it is not probable that HIV protease inhibitors would inhibit SARS-CoV-2 proteases. Indeed, clinical trials assessing potential use of lopinavir-ritonavir among critically ill COVID-19 patients showed that this combination was not beneficial (Cao et al., 2020; Lecronier et al., 2020); in fact, they seemed to have adverse effect (Arabi et al., 2021).

However, there have been speculations that HIV PR inhibitors could affect a different step in the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle. Nelfinavir might act by blocking cell-cell fusion mediated by the spike protein (Yousefi et al., 2021). Amprenavir might destabilize the complex between the host ACE2 receptor and the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and thus inhibit entry of the virus into the host cells (Buitrón-González et al., 2021). Viral entry might be also blocked by lopinavir and darunavir (Singh et al., 2020). No clinical data confirming these speculations are available at present.

4. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) and antiviral therapy

Flaviviruses are enveloped positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses that possess a serine protease with a chymotrypsin-like fold embedded in the viral polyprotein. Once the host cell is infected by a flavivirus, the viral polyprotein is synthesized and intertwined across the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum with the protease located on the cytoplasmic side (Pierson and Diamond, 2020). The protease is part of the multidomain protein NS3, which possesses proteolytic, NTPase, and helicase activity. To be fully active, NS3 needs an activating peptide (Erbel et al., 2006; Hilgenfeld et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2017; Lei et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2015; Majerová et al., 2019; Nie et al., 2021; Tomei et al., 1996). Although inhibitors of flaviviral proteases have been designed, no classical inhibitor of the NS2B/NS3 protease from the Flavivirus genus (such as Dengue, Zika, tick-born encephalitis virus or West-Nile virus) is currently undergoing the approval process. However, a closed derivative of JNJ-A07, a compound blocking protein-protein interactions between Dengue NS3 and NS4, has entered into clinical trials (Behnam and Klein, 2021, 2022; Kaptein et al., 2021).

The situation is different in the case of HCV (a flavivirus from the Hepacivirus genus), against which inhibitors have been developed and are successfully used clinically. HCV is a very important human pathogen: as many as 58 million people worldwide have chronic HCV infection and approximately 290 thousand of them die every year (WHO; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c). Acute infection with HCV can be asymptomatic. While 25% of patients recover spontaneously, 75% develop chronic hepatitis C, which can lead to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, or chronic system inflammatory problems (Pol and Lagaye, 2019). Seven HCV genotypes have been reported, differing in their susceptibility to antiviral drugs (Han et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2014).

HCV enters host cells by receptor-mediated endocytosis. After endosomal fusion, the viral particle is uncoated and viral RNA is released into the host cytoplasm. The 9.6-kb viral genomic RNA is used directly as a template for translation into a single viral polyprotein (Rosenberg, 2001). The nascent viral polyprotein is entwined through the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum and co- and post-translationally processed by proteases on both sides of the membrane. Host proteases ensure processing of viral structural proteins on the luminal side, whereas viral proteases process the nonstructural (NS) proteins on the cytoplasmic side (Lohmann et al., 1996). The viral cysteine protease NS2 autocatalytically cleaves between NS2 and NS3 (Isken et al., 2022; Santolini et al., 1995); the viral serine protease NS3 ensures maturation of viral proteins expressed downstream of NS3, including NS5 replication complex. NS3, which harbors not only a protease but also a helicase, requires an activating cofactor, NS4A, for proteolytic activity. NS4A also anchors NS3 to the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (Hahm et al., 1995).

During viral RNA replication, the endoplasmic reticulum membranes undergo extensive rearrangement. Assembly of new viral particles is initiated at specific sites of rearranged membrane structures. Such membrane vesicles pass through the Golgi apparatus and are released by exocytosis (Alazard-Dany et al., 2019; Dustin et al., 2016; Li et al., 2021). Many host biomolecules are exploited during the HCV replication cycle, including cyclophilin A, liver-specific miRNAs, phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIα, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1, and endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) proteins (Manns et al., 2017).

As HCV is an RNA virus that does not require a DNA intermediate and thus does not integrate into the host cell genome, antivirals can cure HCV infection (in contrast with HIV infection). A combination of two or three direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) administered for 8–24 weeks cures HCV infection in more than 90% of patients (Manns et al., 2017).

Three classes of antivirals are currently in clinical use: NS5 replication complex inhibitors (daclatasvir, elbasvir, ledipasvir, ombitasvir, velpatasvir), NS5B RNA polymerase inhibitors (the nucleoside inhibitor sofosbuvir and the nonnucleoside inhibitor dasabuvir), and NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors (Cervino and Hynicka, 2018). Previous treatment regimens involved therapy using PEGylated interferons and the nucleoside analogue ribavirin (Palumbo, 2011). Several order-of-magnitude increase in the HCV mutation rate and shifts in the mutation spectrum were documented in viral genomes obtained from patients after six months of such a treatment indicating that lethal mutagenesis of the virus is one of the mechanisms of the antiviral effect (Cuevas et al., 2009).

The propensity of HCV to generate mutations is comparable to that of HIV. Thus, minimizing the risk of drug-resistance development became an important factor in therapeutic decision-making and drug design. HCV's RNA genome is replicated by NS5 RNA polymerase, which lacks a proofreading mechanism. The mutation rate is 2.5 × 10⁻⁵ mutations per nucleotide per genome replication (range 1.6–6.2 × 10⁻⁵) (Ribeiro et al., 2012), which translates to two to six mutations per each newly synthesized molecule of viral RNA. The mutations are not spread equally throughout the genome. Studies have indicated differences in mutability across genome sites of more than three orders of magnitude (Geller et al., 2016).

4.1. HCV NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors

Heterodimeric HCV NS3/NS4A protease adopts a chymotrypsin-like fold with the characteristic catalytic triad His-Asp-Ser. All first-generation HCV NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors bind to the active site of the enzyme. In contrast with the aspartic HIV protease, to which inhibitors bind only via non-covalent interactions (e.g. hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions), inhibitors of the serine HCV NS3/NS4A protease bind both via non-covalent interactions and formation of a covalent bond with the catalytic serine. The substrate binding pocket of HCV NS3/NS4A protease is flat, not charged, and exposed to solvent. Moreover, the whole enzyme is structurally flexible and can adapt its conformation depending on the inhibitor structure (Kim et al., 1996; Kwong et al., 1998; Love et al., 1996). Interestingly, early work demonstrated that N-terminal cleavage products of substrate peptides act as potent inhibitors of HCV NS3/NS4A protease. This encouraged the design of inhibitors bound to P positions, with a warhead in the P1 position that covalently modifies the catalytic serine (Steinkühler et al., 1998). First-generation inhibitors of HCV NS3/NS4A protease include the linear compounds boceprevir, telaprevir, and narlaprevir and “a second wave first generation inhibitors” comprising the P1–P3 macrocycles simeprevir and danoprevir (Fig. 6 ) (Sarrazin et al., 2012). Boceprevir, telapreveir, and simeprevir are approved by the FDA, although newer second-generation drugs (see chapter 3.4) are currently preferred in clinical use (Zephyr et al., 2022). Narlaprevir and danoprevir have not been approved by the FDA, but they are used in eastern markets (Baker et al., 2021; Miao et al., 2020).

Fig. 6.

Structures of the first-generation inhibitors of HCV NS3/4A protease.

The first-in-class inhibitor boceprevir (Victrelis®) was approved by the FDA in 2011 (Foote et al., 2011). It is a ketoamide that forms a reversible covalent bond with the catalytic serine of HCV NS3/NS4A protease. Boceprevir was obtained after extensive modifications of the lead ketoamide undecapeptide to maximize inhibition, minimize off-target effects, and optimize pharmacokinetic properties (Madison et al., 2008; Prongay et al., 2007; Venkatraman et al., 2006). The broad-spectrum serine protease neutrophil elastase was used as a model off-target enzyme; boceprevir inhibited HCV NS3/NS4A protease three orders of magnitude more potently than the elastase (Njoroge et al., 2008). Side effects of boceprevir include changes in blood counts, vomiting, changes in taste sensing, and chills (Marks and Jacobson, 2012).

Telaprevir (Incivek® and Incivo®) was also approved by the FDA in 2011 (Traynor, 2011). Like boceprevir, telaprevir is a peptidomimetic with a ketoamide warhead. Its structure was obtained after extensive optimization of all amino acid positions (Kwong et al., 2011; Perni et al., 2003, 2004a, 2004b, 2007) of the natural substrate. Side effects of telaprevir include skin and anorectal problems, gastrointestinal problems, and dysgeusia (Marcellin et al., 2011; Marks and Jacobson, 2012).

Despite differences in the structures of both inhibitors (see Fig. 6), the same patterns of drug-resistance mutations were identified in the S2 subsite of the substrate binding cavity of HCV NS3/NS4A protease: A156 T/S, T54S, V36M, and R155K (Howe and Venkatraman, 2013; Lin et al., 2004; Marks and Jacobson, 2012; Tong et al., 2006; Venkatraman, 2012). Nevertheless, the replicative capacity of telaprevir-resistant variants is lower than that of the wild type virus (Jiang et al., 2013).

The clinical use of boceprevir and telaprevir is limited by their adverse events, suboptimal pharmacokinetics, and low genetic barrier to drug-resistance development (even a single mutation can decrease the sensitivity of the protease to the inhibitor by one order of magnitude (Jiang et al., 2013). Moreover, only HCV genotype 1 is susceptible to these inhibitors (Dienstag, 2015). Because compounds with better features are now available, boceprevir and telaprevir have been withdrawn from the market.

Narlaprevir (Arlansa®) is active against HCV genotypes 1–3. Narlaprevir has a similar profile of drug-resistance development as boceprevir and telaprevir, but HCV harboring drug-resistant variants of NS3/NS4A protease retains some sensitivity to narlaprevir due to its tighter binding (Arasappan et al., 2010; Tong et al., 2010).

4.2. “Second wave” first-generation HCV NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors

The second wave drugs were obtained by cyclization of peptidomimetic inhibitors between the P1 and P3 residues. Cyclization increases the metabolic stability of the drug and decreases the variability of its conformational states which might result in tighter binding to the substrate cavity of the enzyme (Rosenquist et al., 2014).

Simeprevir (Olysiowas) was approved by the FDA in 2013. Simeprevir acts only against HCV genotype 1, but in comparison with other first-generation inhibitors, it has an improved pharmacokinetic profile, reduced side effects, and dramatically reduced drug-drug interactions (Lin et al., 2009; Raboisson et al., 2008; Reesink et al., 2010; You and Pockros, 2013). A polymorphic variant (Q80K) and the mutations A156 T/V, R155K, and D168 T/Y/H/A/V/I confer resistance to this drug (Shepherd et al., 2015).

Another compound developed by a similar strategy is danoprevir (Ganovo®). Like simeprevir, danoprevir occupies the S3–S1′subsites of the substrate binding pocket, but the interactions with the S4 subsite differ between the two compounds (Markham and Keam, 2018; Seiwert et al., 2008; Zephyr et al., 2021).

4.3. Second-generation HCV NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors

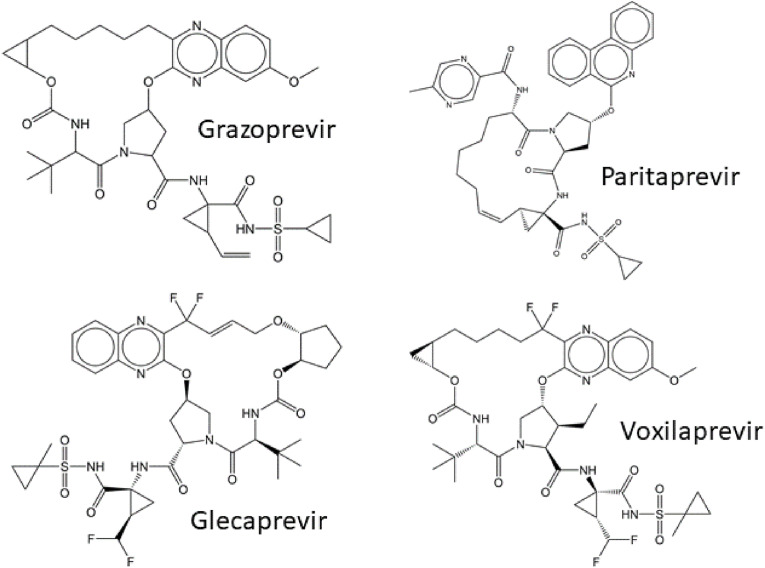

The second-generation HCV NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors were designed to act against a broader spectrum of natural HCV phenotypes and drug-resistant variants, as well as possess a higher barrier to drug-resistance development. The design was inspired by the substrate-envelope hypothesis, which proposes that interactions of an inhibitor with the enzyme binding site should not protrude beyond the substrate envelope, otherwise, the risk increases that a drug-resistant variant will evade inhibitor binding via a mutation outside the substrate envelope, while the interaction with natural substrates will be retained (Nalam et al., 2010). Therefore, the second-generation inhibitors contain a macrocyclic structure formed by connecting the P2 and P4 positions with a linker (Fig. 7 ), which ensures restricted conformational motion. The P2 position is locked in a suitable conformation and modified to block inhibitor contact with R155, as mutation at this position is known to give rise to drug-resistant variants. Instead, the interactions of the P2 position of inhibitors with the strictly conserved catalytic residues D75 and H57 are reinforced (Matthew et al., 2020; Taylor et al., 2019). The second-generation HCV NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors include grazoprevir, paritaprevir, glecaprevir, and voxilaprevir (Fig. 7, Fig. 8 ). Only grazoprevir, glecaprevir, and voxilaprevir are currently in clinical use (Zephyr et al., 2022).

Fig. 7.

Structures of the second-generation inhibitors of HCV NS3/4A protease.

Fig. 8.

A. Structure of HCV NS3/4A protease in the complex with voxilaprevir, pdb code 6NZT (Taylor et al., 2019). The activating peptide is highlighted in green, catalytic residues His 57, Asp 81 and Ser 139 are highlighted in cyan. The inset shows in detail the substrate binding cavity using surface representation with the inhibitor bound. The surface denotes hydrophobic (grey) and hydrophilic (red and blue) atoms of amino acid residues. B. 2D interaction diagram of voxilaprevir bound to HCV NS3/4A protease. The figures were generated using PyMol (Schrödinger and DeLano, 2020) and the PDBe application (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/entry/pdb/6NZT). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Grazoprevir is typically used together with the NS5 replication complex inhibitor elbasvir in a combined formulation (Zepatier®), which was approved by the FDA in 2016 (Harper et al., 2012; Keating, 2016; Summa et al., 2012). It acts against genotypes 1 and 4 (Jacobson et al., 2017b; Zeuzem et al., 2015). The side effects of this therapy include fatigue, headache, and nausea. Even though grazoprevir has a high barrier to drug resistance development, mutations connected with treatment failure can evolve, including V36 L/M, Y56 F/H, Q80 K/L, R155I/K/L/S, A156 G/M/T/V, V158A, and D168 A/C/E/G/K/N/V (Sorbo et al., 2018).

Unlike other second-generation HCV NS3/NS4A inhibitors, paritaprevir is cyclized at positions P1–P3. This macrocyclic acylsulfonamide is used mainly against HCV genotype 1. Drug combinations involving paritaprevir were approved by the FDA in 2016 (Saab et al., 2016); however, they are not currently available on the market. Paritaprevir was a component of Technivie®, which contained ombitasvir (an inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase), paritaprevir, and ritonavir as a pharmacokinetic booster, and Viekira Pak®, which contained ombitasvir, paritaprevir, ritonavir, and dasabuvir. These treatments were effective and well-tolerated (Bacinschi et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2019; Lawitz et al., 2013). Drug resistance was associated with the mutations R155K and D168 N/Y/V (Boonma et al., 2019; Krishnan et al., 2015).

Glecaprevir, approved by the FDA in 2017, is a component of Mavyret®/Maviret®, which also contains the replicase complex inhibitor pibrentasvir (Mensa et al., 2019). It acts against all HCV genotypes, including genotype 3, which is not otherwise sensitive to inhibition (Gane et al., 2016a; Lawitz et al., 2013, 2015). Common drug-resistant HCV mutants are somewhat more sensitive to glecaprevir compared to other HCV protease inhibitors. Glecaprevir failure may occur in the presence of V36M, Y56 H/N, Q80 K/R, R155T, A156 G/T/V, and Q168 A/K/L/R mutations (Sorbo et al., 2018). Glecaprevir is well-tolerated (Lin et al., 2017; Park et al., 2021) and associated with a low frequency of adverse events, with serious adverse events reported in 0.8–7.5% of cases. One study indicated that therapy was stopped due to adverse events in 0.3–3.8% of cases (Cotter and Jensen, 2019), another study reported 1% of serious adverse events, leading in 0.6% to discontinuation of the therapy. For comparison, discontinuation of the therapy due to adverse events was one order of magnitude higher, e.g. 18% for boceprevir and telaprevir (Gordon et al., 2015).

Voxilaprevir (Fig. 7, Fig. 8), approved by the FDA in 2017, is a component of Vosevi®, which also includes the anti NS5 RNA polymerase drugs sofosbuvir and velpatasvir. It is active against multiple genotypes and is also useful in re-treatment regimens (Gane et al., 2016b, 2016c; Jacobson et al., 2017a; Lawitz et al., 2016, 2017; Rodriguez-Torres et al., 2016). Mutations associated with drug therapy failure include Y56F for the G1b phenotype and A166T for the G3a phenotype (Garcia-Cehic et al., 2021). The side effects include fatigue, headache, nausea, and diarrhea (Heo and Deeks, 2018).

4.4. Repurposing of HCV NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors

In vitro assays revealed that some HCV NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors also act against SARS-CoV-2 main protease. However, the inhibition constants (IC50 and EC50) of the HCV NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 main protease were in the micromolar range in experiments with the purified enzyme and antiviral tissue culture assays (Baker et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2020; Oerlemans et al., 2021). This range is probably above the concentrations needed for effective and safe use of these compounds in clinical practice.

The HCV NS3/NS4A protease inhibitors simeprevir, vaniprevir, paritaprevir, and grazoprevir showed a similar potency against SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease as against the main SARS-CoV-2 protease. Importantly, these four compounds exhibited a synergistic effect with remdesivir (an inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase) (Boras et al., 2021) in antiviral cell culture experiments. This effect was not observed for compounds that inhibit solely SARS-CoV-2 main protease (e.g., boceprevir) (Bafna et al., 2021). None of the inhibitors of HCV NS3/NS4A protease has been approved for treatment of COVID-19.

5. SARS-CoV-2 and antiviral therapy

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the third emerging coronavirus within the last twenty years. It was preceded by SARS-CoV (Qin et al., 2003) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (van Boheemen et al., 2012). SARS-CoV was first identified in 2003 in China and spread to 29 countries, leading to 8,096 cases and 774 confirmed deaths. This epidemic was successfully eradicated by strict public health measures. MERS-CoV, originating from natural reservoirs in bats and transmitted via dromedary camels, was first identified in humans in 2012 in Saudi Arabia. All reported cases in humans have been related to residence in or travel to the Middle East, with 2,519 cases and 866 deaths from MERS-CoV infection reported by January 2020 (da Costa et al., 2020). The other human coronaviruses―HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, and HCoV-HKU1―have been circulating in the human population for a long time and cause common cold (Corman et al., 2018).

The first SARS-CoV-2 infections were reported in Wuhan, China at the end of 2019 (Hui et al., 2020) The virus has spread worldwide, resulting in a pandemic that has led to the loss of several million lives and caused severe economic and social consequences. Several antigenic variants, differing in virulence and infectivity, have evolved over time. The Omicron variants that are currently dominant seem to be more contagious than previous variants but cause less serious illness that is more frequently restricted to the upper respiratory tract (Pia and Rowland-Jones, 2022; Shuai et al., 2022).

Like other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 has a 30-kb single-stranded positive RNA genome (Bar-On et al., 2020). Viral structural proteins, among them the surface spike protein, are expressed from alternatively spliced mRNAs. Viral enzymes are translated as a shorter polyprotein called pp1a (harboring proteins nsp1–nsp11) and as the longer pp1ab polyprotein (harboring proteins nsp1–nsp16) after a frameshift suppressing the stop codon at the terminus of pp1a (Bhatt et al., 2021). This mechanism likely ensures an optimal ratio of viral non-structural proteins. Two proteases are embedded in pp1a: SARS-CoV-2 main protease (also known as chymotrypsin-like main protease 3CLpro or nsp5) and papain-like protease (PLpro), which is a part of a multifunctional multidomain protein called nsp3 (Klemm et al., 2020; Osipiuk et al., 2021). Both enzymes are cysteine proteases (Arya et al., 2021).

PLpro (nsp3) cleaves the first three nonstructural proteins of the viral polyprotein into the functional proteins nsp1, nsp2, and nsp3. This protease also cleaves ubiquitin-like interferon-stimulated gene 15 protein (ISG15) and has a deubiquitylating activity, which can disrupt the host interferon response and interfere with NF-κB pathways. In vitro, inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro by the compound GRL-0617, originally designed to inhibit SARS-CoV PLpro (Ratia et al., 2008), reduced virus-induced cytopathogenic effects, preserved the antiviral interferon response, and reduced production of viral particles in infected cells (Shin et al., 2020). As noted, some inhibitors of HCV NS3/NS4A protease are able to inhibit PLpro in vitro and act synergistically with other compounds (Bafna et al., 2021). However, no inhibitors of PLpro are currently in clinical use.

The second protease, SARS-CoV-2 main protease, cleaves the 13 remaining sites of the viral polyprotein (Jin et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a). Although the polyprotein harbors nsp3, nsp4, and nsp6 proteins, which are intertwined across the membrane of endoplasmic reticulum, all of the cleavage sites are accessible from the cytosolic side (Majerová et al., 2019; V'Kovski et al., 2021).

Over the last two years, efforts to develop antivirals against SARS-CoV-2 have led to discoveries and FDA emergency use authorization or approvals of several drugs, including anti-spike specific monoclonal antibodies (Hwang et al., 2022) and the viral RNA polymerase inhibitors remdesivir (Veklury®) and molnupiravir (Lagevrio®). Remdesivir is administered intravenously, while molnupiravir is available orally (de Wit et al., 2020; Kabinger et al., 2021; Sheahan et al., 2017; Toots et al., 2019, 2020; Warren et al., 2016; Williamson et al., 2020). At the end of 2021, the FDA authorized nirmatrelvir (PF-07321332) (Owen et al., 2021) co-administered with the pharmacokinetic booster ritonavir (Paxlovid®). Nirmatrelvir is a specific inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. In addition, the following immunomodulating compounds are currently available to treat COVID-19: baricitinib (Olumiant®, Janus kinase inhibitor), recently approved by both the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Rubin, 2022a), and anakinra (Kineret®, antagonist of interleukin-1), only approved by EMA (Atluri et al., 2022).

Interestingly, most of these drugs were obtained from drug repurposing programs. Remdesivir was originally studied as a potential anti-HCV and later anti-Ebola drug (Sheahan et al., 2017; Warren et al., 2016), and molnupiravir as a potential anti-influenza drug (Toots et al., 2019). Baricitinib and anakinra were originally approved for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases. Another compound with a similar mechanism of action as baricitinib―tofacitinib―has recently entered the authorization process (Ely et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2021). Different supportive drugs such as corticoids and anticoagulants are also sometimes used to improve COVID-19 symptoms (Napoli et al., 2021).

Like other viruses, SARS-CoV-2 acquires mutations over time. The mutation rate of coronaviruses is lower than that of other RNA viruses, as their exonucleases are capable of proofreading (Denison et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2021). SARS-CoV-2 typically accumulates two point mutations per month, while the mutation rates of influenza and HIV are two- and four-times higher, respectively (Callaway, 2020), Importantly, viruses harboring mutations in the spike protein, which are responsible for overcoming acquired host immunity, do not harbor mutations in the viral enzymes exploited as drug targets. Indeed, even the Omicron variant, which has an increased ability to escape antibodies after previous immunizations, retains sensitivity to low-molecular-weight antivirals (Vangeel et al., 2022). As clinical use of novel antiviral drugs expands, resistant variants of SARS-CoV-2 may evolve under selection pressure. However, a potential trade-off between virulence and transmissibility (Blanquart et al., 2016; Simmonds et al., 2019) (together with a necessity to circumvent acquired immunity and/or to reduce susceptibility to antivirals) could favor the selection of milder viral variants.

5.1. SARS-CoV-2 main protease as an established therapeutic target

SARS-CoV-2 main protease (SARS-CoV-2 Mpro) is a key player in viral maturation and an important factor for SARS-CoV-2 pathogenicity (Pablos et al., 2021). SARS-CoV-2 Mpro was also exploited for a potential detection of the virus in clinical samples using activity-based probes (Rut et al., 2021). SARS-CoV-2 main protease is a cysteine protease with a catalytic dyad of Cys 145 and His 41 (Lee et al., 2020). The protease is embedded in viral polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab, from which it is autocatalytically released. Each SARS-CoV-2 Mpro monomer consists of three domains: rigid N-terminal domains I and II with a chymotrypsin-like fold and the more dynamic domain III. The protease is almost inactive in its monomeric form, and dimerization between the N-terminus of one monomer and domain II of a second monomer is required to establish a fully active enzyme. Binding of a ligand then stabilizes the active conformation (Jin et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a). Interestingly, although the dimer harbors two active sites, only one monomeric subunit binds the substrate, and the monomeric subunits alternate in their activity through a flip-flop mechanism (Sheik Amamuddy et al., 2021). In contrast, SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors bind to both monomeric subunits simultaneously, as observed in X-ray structures (Jin et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a).

5.2. Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease

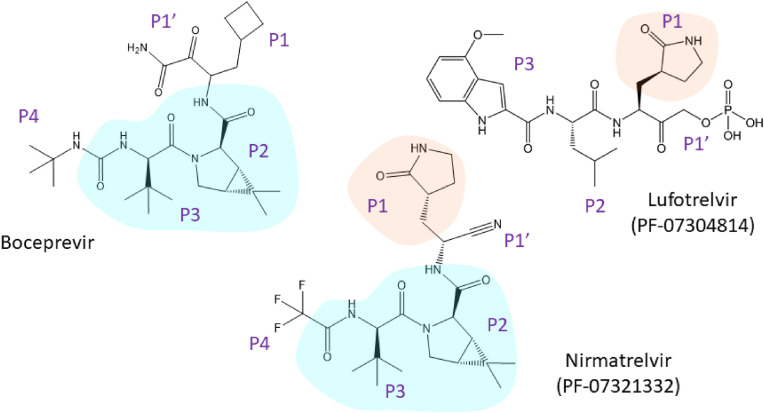

Although allosteric binding sites in the SARS-CoV-2 main protease structure have been reported (El-Baba et al., 2020), most inhibitors being developed, including nirmatrelvir (PF-07321332) (Fig. 9, Fig. 10 ), target the active site of the enzyme (Chia et al., 2022; Owen et al., 2021). The development of nirmatrelvir was facilitated by prior efforts to target SARS-CoV that emerged in years 2002–2003. SARS-CoV main protease is 96% identical with the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Zhang et al., 2020a). An inhibitor of SARS-CoV main protease PF-00835231 was developed by Pfizer. The α-hydroxymethylketone warhead of this compound forms a covalent reversible bond with the catalytic cysteine of the protease (Hoffman et al., 2020). Masking this reactive warhead by phosphorylation resulted in a prodrug lufotrelvir (PF-07304814) (Fig. 9), which is suitable for intravenous application. This prodrug is more soluble than the parental compound. The phosphate group is removed by host alkaline phosphatase, which is abundant in liver, lung and kidney. Lufotrelvir (PF-07304814) is now in clinical trials for treatment of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients (Boras et al., 2021).

Fig. 9.

Rational design of nirmatrelvir - the first FDA-authorized inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (emergency use authorization). Nirmatrelvir shares similar features with lufotrelvir (a phosphate prodrug in the pipeline) and with boceprevir (an approved inhibitor of HCV NS3/NS4A protease).

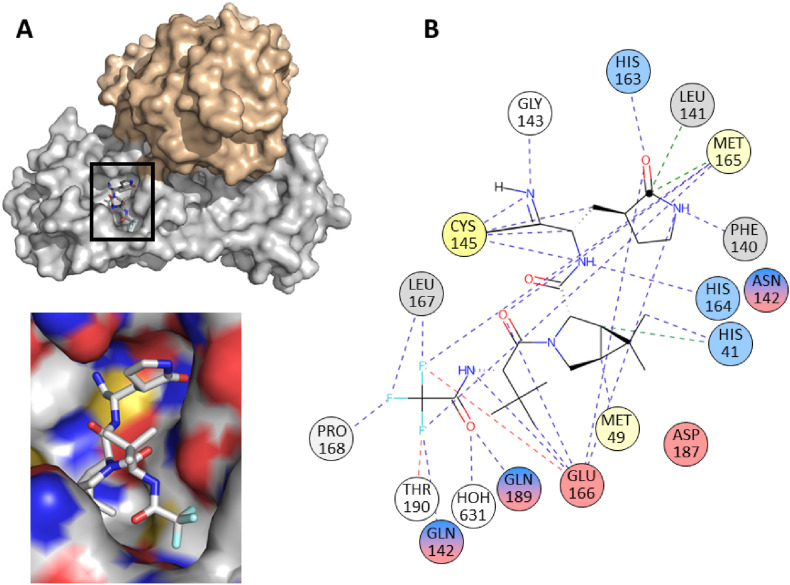

Fig. 10.

A. A homodimeric structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease with nirmatrelvir bound to one of the monomeric subunits (grey) with the inset showing in detail the nirmatrelvir using the substrate binding site of the protein surface representation. The surface denotes hydrophobic (grey) and hydrophilic (red and blue) atoms of amino acid residues. B. 2D interaction diagram of nirmatrelvir bound to the monomer of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (pdb 7RFW, (Owen et al., 2021). The figures were generated using PyMol (Schrödinger, 2020) and the PDBe application (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/entry/pdb/7RFW). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The structure of nirmatrelvir was also inspired by PF-00835231 (Fig. 9) (Boras et al., 2021; Hoffman et al., 2020; Owen et al., 2021). Nirmatrelvir was optimized for the antiviral effect and for stability enabling oral administration. Similar to PF-00835231, the glutamine, which is essential at the P1 position of natural substrates, was replaced with the γ-lactam moiety (Dragovich et al., 1999). To reduce the chance of off-target binding, the α-hydroxymethylketone warhead of PF-00835231 was replaced with a nitrile group. The nitrile group retains its reactivity with the thiol group of the catalytic cysteine in the active-site of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, but the binding is more reversible (Boike et al., 2022; Boras et al., 2021; Chuck et al., 2013; Owen et al., 2021). The P2 and P3 positions are formed by a dipeptide fragment of boceprevir. Boceprevir is an inhibitor of HCV protease approved for clinical use, and it showed moderate activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro (Fu et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2020; Madison et al., 2008; Prongay et al., 2007; Shekhar et al., 2022). Leucine in the P2 position is preferred in natural SARS-CoV-2 substrates (Rut et al., 2021). To preserve this structural feature in the inhibitor, a leucine mimetic harboring 6,6-dimethyl-3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane structure was incorporated. This moiety retains hydrophobic interactions and is more conformationally rigid (Fu et al., 2020). The trifluoromethyl group in the P4 position increases hydrophobic interaction with the substrate binding pocket, membrane permeability and metabolic stability (Gillis et al., 2015; Owen et al., 2021).

A combination of nirmatrelvir with the pharmacokinetic booster ritonavir (Paxlovid®) was authorized by the FDA for treatment of COVID-19 in late 2021. Clinical studies showed that when nirmatrelvir/ritonavir therapy was initiated 3 or 5 days after diagnosis, the probability of hospitalization was reduced 8.8- and 6.7-fold, respectively (Couzin-Frankel, 2021). Co-administration of ritonavir with nirmatrelvir is necessary to achieve a plasma concentration of nirmatrelvir sufficient for an efficient antiviral effect (Lamb, 2022). Even though ritonavir is a well-established pharmacokinetic booster, caution is required when using it in combination with nirmatrelvir (Heskin et al., 2022). Several adverse events have been reported among people using this therapy, with dysgeusia, diarrhea, hypertension, and myalgia being the most frequent. Additionally, ritonavir is not only a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4, but also shows inhibitory effects on other isoenzymes of cytochrome P450 (namely CYP3A4, CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C8, and CYP2C9) as well as on the multidrug resistance transporter ABCB5 P- glycoprotein, breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2), the liver organic anion transporter (hOCT1), and the drug efflux mediating protein MATE1. Moreover, ritonavir induces isoenzymes CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19. It is thus not surprising that this compound has significant drug-drug interactions, including with anticoagulants, antiarrhythmics, statins, steroids, and sedative hypnotics. Many of these agents are prescribed separately to elderly patients who are at the greatest risk of developing complications from SARS-CoV-2 infection (Heskin et al., 2022). Patients under long-term medication containing a pharmacokinetic booster (ritonavir or cobicistat) can use nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, if necessary (Marzolini et al., 2022).

Nirmatrelvir is a reversible covalent inhibitor with a nitrile warhead targeting the catalytic Cys 145 of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (Fig. 9, Fig. 10). Upon binding, the nitrile group of the inhibitor forms a thioimidate adduct with Cys 145; the binding is stabilized by a hydrogen bond with the backbone of Gly 143. The (S)-γ-lactam ring of the glutamine surrogate in the P1 position of the inhibitor forms hydrogen bonds with the side chains of His 163 and Glu 166 and the main chain of His 164. A conformationally constrained hydrophobic dimethylcyclopropylproline group in the P2 position interacts with the side chains of His 41, Met 49, Tyr 54, Met 165, and Asp 189, and with the main chains of Asp 187 and Arg 188. The tert-butyl group in the P3 position of the inhibitor is exposed to solvent and has limited interactions with Mpro. The amide nitrogen of the trifluoroacetyl group in the P4 position of the inhibitor forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Glu 166. Moreover, the trifluoromethyl group forms hydrogen bonds with Gln 192 and binds two ordered water molecules, which stabilizes the interaction with the S4 subsite of Mpro (Zhao et al., 2021) (Fig. 9, Fig. 10). The contacts between the inhibitor and the protein backbone are important, as they reduce the risk of drug-resistance development. Nevertheless, (see above) nirmatrelvir forms several contacts outside the “substrate envelope” with Asn 142 at P1 position, with Asp 187, Gln 189, Thr 190, Gln 192 at P2 position and with Met 165 in P3 position (Shaqra et al., 2022). For potential development of drug resistance were predicted residues in regions 45–51 and 186–192. Such mutations were found in sequences of clinical viral isolates, but they were not phenotypically evaluated (Yang et al., 2022). In vitro selection revealed three mutations that conferred resistance to nirmatrelvir: L50F, E166 A/V and L167F. (Jochmans et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022). Furthermore, although the E166V mutation resulted in a reduction of sensitivity to nirmatrelvir by two orders of magnitude, this mutation also resulted in viruses bearing it losing replicative fitness. The fitness was restored by compensatory mutations L50F and T21I (Iketani et al., 2022). Mpro mutants of all common viral variants found in patients were susceptible to inhibition by nirmatrelvir (Greasley et al., 2022).

Although Paxlovid® reduces hospitalizations and deaths (Wen et al., 2022), a rebound phenomenon has been reported. In some patients, the virus is eradicated during the course of Paxlovid® therapy, but several days after the therapy is discontinued, the patient tests positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection again (Burki, 2022; Coulson et al., 2022). No drug-resistant variants have appeared, and no antibody-evading spike mutations have been identified in samples from such patients (Carlin et al., 2022). There are hypotheses that this phenomenon results from a suboptimal dose of the drug or that the early onset of the therapy blocks an efficient immune response (Rubin, 2022b). Inter and extracellular membrane structures containing the virus could play a role in virus and viral fragments shedding (e.g. preserving intact genomic viral RNA) or even in spread via intercellular transport pathways acting as a “Trojan horse”. Such viruses could be reactivated after finishing of the antiviral therapy (Badierah et al., 2021; Borowiec et al., 2021; Merolli et al., 2022). Further investigation of the rare rebound phenomenon is required.

Combinations of drugs targeting different steps of the viral life cycle have proven to be efficient in the therapy of viral infections. For SARS-CoV-2, possible combinations include nirmatrelvir with either molnupiravir or remdesivir. A study has shown improvement in survival of SARS-CoV-2 infected mice under such experimental combination therapies (Jeong et al., 2022), but clinical data are needed. Co-administration of these drugs could synergize some adverse drug reactions.

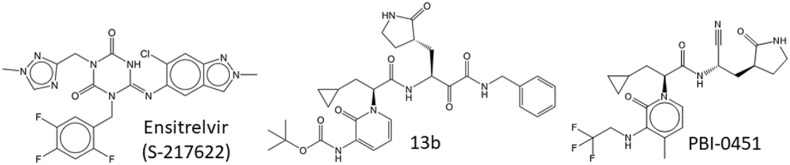

For individual treatment optimization, in terms of circumventing development of SARS-CoV-2 drug resistance and obtaining drugs with acceptable side effects and drug-drug interactions as well as with improved plasma stability without the necessity to use pharmacokinetics boosters, the availability of additional Mpro inhibitors would be beneficial. Currently, several Mpro inhibitors are in the pipeline (Fig. 9, Fig. 11 ), including lufotrelvir (PF-07304814), a peptidomimetic prodrug intended for intravenous application; ensitrelvir (S-217622, Xocova®) (Sasaki et al., 2022; Unoh et al., 2022); PBI-0451 (Pardesbio; https://www.pardesbio.com/pipeline/) as well as 13b (Cully, 2022; Zhang et al., 2020a); and tollovir (Todosmedical; https://todosmedical.com/tollovir). As main protease is well-conserved (Yang et al., 2022), inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro may be at least partially active against new SARS-CoV-2 variants, and could be useful for repurposing against potential novel emerging coronaviruses.

Fig. 11.

Structures of compounds in the pipeline.

Computer aided design speeds up drug development, reduces experimental work and makes processes more cost-effective. Approaches, such as structure-based and ligand-based virtual screening, help to identify novel drugs, to optimize leading compounds (da Silva Rocha et al., 2019; Evenseth et al., 2020; Proia et al., 2022) or can help in drug-repurposing strategies (Gan et al., 2022; Mody et al., 2021). Positive hits identified, must be verified experimentally. Even inhibition of a target in an experiment does not necessarily mean clinically relevant inhibition.

For design of novel structures an innovative approach “Virtual SYNThhon Hierarchical Enumeration Screening” (V-SYNTHES) has been employed: final molecules are obtained after several iterative steps of screening of small fragment-like molecules followed by building a focused library of larger compounds combining fragment hits as building blocks (Sadybekov et al., 2022). Machine learning further boosts drug design. Here, an algorithm searches for general structural patterns of desired pharmacodynamical and/or pharmacokinetic properties in known molecules and tries to transfer these properties into structures of newly designed compounds (Graff et al., 2021; Priya et al., 2022; Tanramluk et al., 2022; Zhang and Lee, 2019; Zhang et al., 2022). All the artificial intelligence (AI) approaches need experimental data sets for a starting input as well as for validation (e.g., X-ray structures, inhibition constants). High quality and quantity of experimental data boost the future success of AI in drug design.

AI has been involved in the COVID Moonshot initiative for non-profit patent-free development of antivirals, when non-covalent SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors were designed (Achdout et al., 2022; Morris et al., 2021). Compounds obtained by the Moonshot initiative and non-covalent inhibitors designed earlier against SARS-CoV were helpful in construction of pharmacophores in the binding site of SARS-CoV-2 main protease and subsequent virtual screening followed by biological screening. This effort led to the identification of compound S-217622, which is currently being approved in Japan (Fig. 11) (Han et al., 2022; Jacobs et al., 2013; Unoh et al., 2022).

6. Important viral proteases for future targeting

Even though the field of antiviral research has been rapidly advancing, there are viral infections with limited or no therapy options. Indeed, no inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 papain like protease (PLpro), herpes serine proteases, or poxviral protease are currently in clinical use, although such drugs would increase the possibility of individual treatment optimization. Moreover, no treatments for infections caused by the flaviviruses Dengue virus, Zika virus, West Nile virus, yellow fever virus, and tick-born encephalitis virus are available. Efforts are underway to develop such drug candidates.

SARS-CoV-2 papain like protease (SARS-CoV-2 PLpro) plays an important role in SARS-CoV-2 maturation and contributes to evasion of the host antiviral immune response. It is embedded in the large multifunctional multidomain membrane protein nsp3, which is released from the pp1a and pp1ab precursor by the PLpro domain (Klemm et al., 2020; Lei et al., 2018). SARS-CoV-2 PLpro contains a catalytic cysteine and four conserved non-active-site cysteines, which coordinate a zinc cation. Clinical availability of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors would be beneficial, as they could reduce viral replication and support an innate immune response to virus-induced cytopathogenic effects (Osipiuk et al., 2021). Design of specific inhibitors targeting the active site of the enzyme might be problematic due to substrate specificity similarities with host enzymes, particularly deubiquitinylases. However, highly specific active-site targeted inhibitors have been designed (Rut et al., 2020). Compounds with alternative binding modes could represent another interesting alternative. For instance, some inhibitors reported to bind SARS-CoV-2 PLpro and showing no serious cytotoxicity (including GRL-0617) bind atypically to the substrate cavity, as they interact with the P3 and P4 positions and omit the catalytic site (Lv et al., 2022). In addition, allosteric compounds might have a reduced risk of off-target binding (Armstrong et al., 2021; Majerová and Novotný, 2021). Flaviviral proteases (viruses like Dengue, Zika, West-Nile, tick-born encephalitis) have some similar structural and enzymological features that could be exploited for design of panflaviviral inhibitors (Akaberi et al., 2021). On the other hand, less specific compounds acting against a wide range of viruses might inadvertently damage the host virome (De Vlaminck et al., 2013; Liang and Bushman, 2021).

Studies of autoprocessing of Dengue protease revealed a trans-dominant inhibitory effect of unprocessed precursors on production of infectious viral particles. This trans-dominant effect (i.e. blocking active enzyme molecules via interactions with inactive enzyme species) could be achieved either by partial inhibition of polyprotein processing by a PR inhibitor, or by co-infection of the cells by an autoprocessing defective mutant. This effect could slowdown potential drug resistance development during treatment of flavivirus infections using specific protease inhibitors (Constant et al., 2018; Majerová and Novotný, 2021).