Abstract

This cohort study assesses the frequency of approval and marketing of skinny-label biosimilars and their savings to Medicare.

Analogous to generic drugs, biosimilars are versions of biologic drugs made by other manufacturers that help stimulate price competition after the biologic’s market exclusivity ends. Although biologics comprise fewer than 5% of prescription drug use, they account for approximately 40% of US drug spending.1,2 Biologic manufacturers often take steps to delay availability of biosimilars, including by obtaining patents and regulatory exclusivities for supplemental indications that expire years after those covering the biologic’s original indications.3 To help prevent this source of potential delay, federal law permits the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve “skinny-label” generic drugs and biosimilars that carve out indications protected by patents or regulatory exclusivities.4 With recent court rulings threatening the skinny-label pathway,5 we assessed the frequency of approval and marketing of skinny-label biosimilars and their savings to Medicare.

Methods

We compared FDA labels of biosimilars approved from 2015 through 2021 with those of their corresponding biologic, assessing whether they included all (full label) or some (skinny label) of the biologic’s indications. For skinny-label biosimilars, we searched supplemental approval letters, FDA review documents, the FDA’s Orphan Drug Product Approvals database, and the Espacenet patent database to identify patents and regulatory exclusivities protecting carved-out indications (eMethods and eTable 1 in the Supplement).

We measured the time biologics experienced competition due to skinny labeling from the marketing of the first skinny-label biosimilar to the first full-label biosimilar approval, the latest patent or regulatory exclusivity expiration protecting carved-out indications, or December 31, 2021, whichever was earliest. In a sensitivity analysis, we projected potential periods of competition from skinny-label biosimilars beyond 2021. In another sensitivity analysis, we excluded the effects of patents because they can be invalidated in litigation.

Using the Medicare Dashboard, we estimated annual Part B (clinician-administered) savings from skinny-label biosimilars through 2020 by comparing actual biologic and skinny-label biosimilar spending with estimated biologic spending without competition, assuming the unit price of the biologic would increase at its 5-year compound annual growth rate prior to competition. We multiplied the difference in price by the annual units of the biologic and biosimilar used by Medicare beneficiaries. In a sensitivity analysis, we estimated Medicare savings holding constant the use and price of the biologic from the year before biosimilar competition. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Results

From 2015 to 2021, FDA approved 33 biosimilars linked to 11 biologics (Figure 1), including 22 (66.7%) with a skinny label. Of 21 biosimilars marketed before 2022, 13 (61.9%) were launched with a skinny label. These 21 biosimilars were linked to 8 biologics.

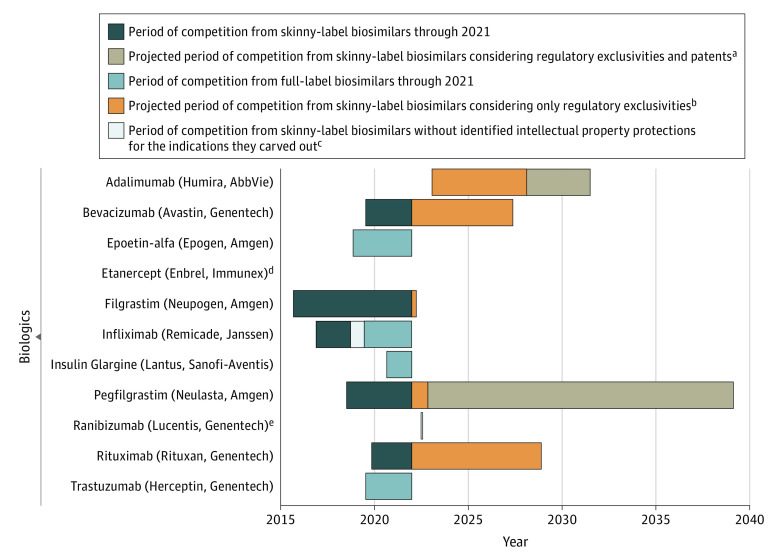

Figure 1. Competition From Skinny-Label and Full-Label Biosimilars for Biologics Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Through 2021.

aThis projected period of competition was based on the latest expiration date among patents and regulatory exclusivities protecting the indication(s) carved out of the biologic’s label.

bThis projected period of competition was based on the latest expiration date among regulatory exclusivities protecting the indication(s) carved-out of the biologic’s label.

cThis period of competition represents when only skinny-label biosimilars were commercially available but a full-label biosimilar could have been marketed based on the expiration dates of the identified patents and regulatory exclusivities protecting the carved-out indication(s).

dTwo full-label etanercept biosimilars were approved by the FDA but are not expected to be marketed until 2029.

eThis bar is shaded white.

For 5 of these 8 biologics, the first-to-market biosimilar had a skinny label, leading to a median (IQR) of 2.5 (2.1-3.5) years of earlier competition through 2021 (Figure 1). Beyond 2021, skinny labeling could lead to earlier competition for 6 of 11 biologics by a median (IQR) of 5.8 (4.5-7.5) years until expiration of regulatory exclusivities (principally from the Orphan Drug Act) and a median (IQR) of 8.2 ( 6.9-8.9) years until expiration of patents.

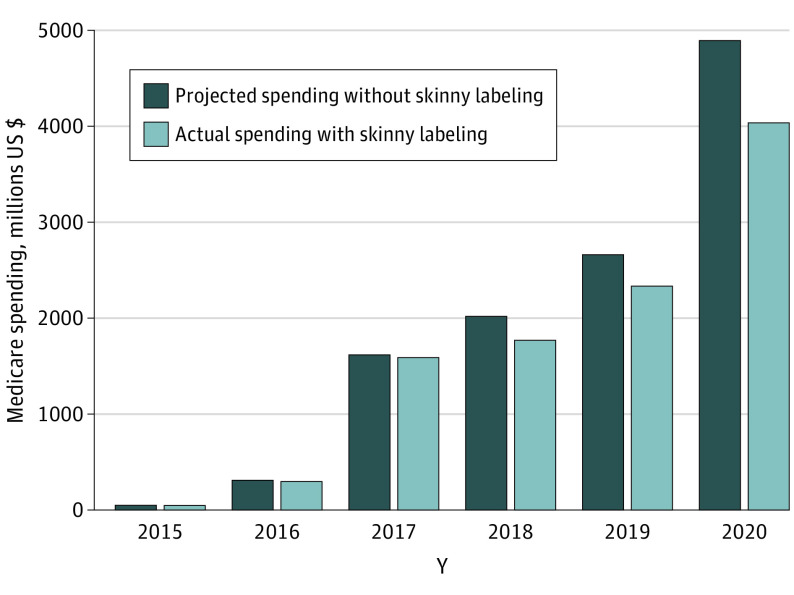

Competition from skinny-label biosimilars was estimated to save Medicare $1.5 billion from 2015 to 2020 (Figure 2), which is 4.9% of the $30.2 billion Medicare spent on the 5 biologics during the period. In the sensitivity analysis with biologic use and price held constant, the estimated savings were $925 million.

Figure 2. Estimated Medicare Savings From Skinny-Label Biosimilars, 2015 to 2020.

Each light-blue bar represents reported annual Medicare Part B spending on biologics and their skinny-label biosimilars, whereas each dark-blue bar represents estimated annual spending on originator biologics had skinny labeling not been available. The difference between each light-blue and dark-blue bar pair represents annual estimated savings, which increased from $2 million in 2015 to $857 million in 2020 because more biologics experienced skinny-label biosimilar competition and additional skinny-label biosimilars were marketed. Spending was converted to 2021 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers.

Discussion

Use of skinny labeling led to years of earlier competition for 5 biologics through 2021, with estimated savings to Medicare of $1.5 billion through 2020. Once the blockbuster immunosuppressive drug adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie) faces competition from skinny-label biosimilars in 2023, savings will likely grow substantially.6 Skinny labeling for biosimilars is important to ensure timely competition for biologics, helping make these medications more affordable and accessible.

This study was restricted to information available before 2022. The biologics in our sample may in the future acquire additional indications, regulatory exclusivities, and patents. Our study also may not have identified all patents protecting carved-out indications. Both unidentified and future patents and regulatory exclusivities could further delay competition without skinny labeling.

eMethods

eTable 1. Rules for Assessing Whether a Patent is Protective of a Carved-Out Indication

eReferences

References

- 1.Mulcahy AW, Hlavka JP, Case SR. Biosimilar Cost Savings in the United States: Initial Experience and Future Potential. RAND Corporation. Published 2017. Accessed September 21, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE264.html [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.IQVIA Institute . Biosimilars in the United States 2020-2024. Published October 2020. Accessed September 21, 2022. https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/iqvia-institute-biosimilars-in-the-united-states.pdf

- 3.Van de Wiele VL, Beall RF, Kesselheim AS, Sarpatwari A. The characteristics of patents impacting availability of biosimilars. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40(1):22-25. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-01170-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh BS, Sarpatwari A, Rome BN, Kesselheim AS. Frequency of first generic drug approvals with “skinny labels” in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(7):995-997. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh BS, Bloomfield D, Kesselheim AS. A court decision on “skinny labeling”: another challenge for less expensive drugs. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1371-1372. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulcahy A, Buttorff C, Finegold K, et al. Projected US savings from biosimilars, 2021-2025. Am J Manag Care. 2022;28(7):329-335. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2022.88809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eTable 1. Rules for Assessing Whether a Patent is Protective of a Carved-Out Indication

eReferences