Abstract

Lignin, one of the most abundant polymers in plants, is derived from the phenylpropanoid pathway, which also gives rise to an array of metabolites that are essential for plant fitness. Genetic engineering of lignification can cause drastic changes in transcription and metabolite accumulation with or without an accompanying development phenotype. To understand the impact of lignin perturbation, we analyzed transcriptome and metabolite data from the rapidly lignifying stem tissue in 13 selected phenylpropanoid mutants and wild-type Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). Our dataset contains 20,974 expressed genes, of which over 26% had altered transcript levels in at least one mutant, and 18 targeted metabolites, all of which displayed altered accumulation in at least one mutant. We found that lignin biosynthesis and phenylalanine supply via the shikimate pathway are tightly co-regulated at the transcriptional level. The hierarchical clustering analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) grouped the 13 mutants into 5 subgroups with similar profiles of mis-regulated genes. Functional analysis of the DEGs in these mutants and correlation between gene expression and metabolite accumulation revealed system-wide effects on transcripts involved in multiple biological processes.

Analysis of transcripts and metabolites in wild-type and 13 lignin biosynthetic mutants of Arabidopsis reveals the global impact on transcription and metabolite network perturbations.

Introduction

Lignin, a phenolic polymer co-deposited with polysaccharides in the secondary cell wall, provides plant cells with mechanical strength and the hydrophobicity required to conduct water. In angiosperms, lignin is derived from three major monomers, namely p-coumaryl, coniferyl, and sinapyl alcohol, which form p-hydroxyphenyl (H), guaiacyl (G), and syringyl (S) lignin, respectively (Boerjan et al., 2003; Bonawitz and Chapple, 2010). These monomers are derived from the phenylpropanoid pathway starting with phenylalanine (Phe), and in grasses, tyrosine (Tyr) (Barros et al., 2016), both of which are products of the shikimate pathway (Maeda and Dudareva, 2012). In each case, the side chain of the amino acid is deaminated and reduced, and the phenyl ring is hydroxylated and O-methylated, to give rise to the three monolignols through eleven enzymatic steps. These enzymes include PHE AMMONIA LYASE (PAL), or PHE/TYR AMMONIA LYASE in grasses, CINNAMATE 4-HYDROXLASE (C4H), 4-COUMARATE:COA LIGASE (4CL), HYDROXYCINNAMOYL:COA SHIKIMATE HYDROXYCINNAMOYL TRANSFERASE (HCT), p-COUMARIC ACID 3-HYDROXYLASE (C3H) p-COUMAROYL 3′-HYDROXYLASE (C3′H), CAFFEOYL SHIKIMATE ESTERASE (CSE), CAFFEOYL COA O-METHYLTRANSFERASE (CCoAOMT), FERULATE 5-HYDROXYLASE (F5H), CAFFEIC ACID O-METHYLTRANSFERASE (COMT), CINNAMOYL COA REDUCTASE (CCR), and CINNAMYL ALCOHOL DEHYDROGENASE (CAD). The monomers, once synthesized, are exported to the cell wall, activated to their free radicals by laccases (LAC) and peroxidases (PRX), and polymerized into lignin (Berthet et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2013).

Phenylpropanoid metabolism is tightly regulated at both the transcriptional and posttranslational levels to control the substantial carbon flux toward lignin. A hierarchical network of transcription factors (TFs) regulates lignification and secondary cell wall formation in plants. Five master regulators from the NAM, ATAF1,2, and CUC2 (NAC) family activate the secondary-level MYB TFs including MYB46 and MYB83 (Zhong et al., 2008; Taylor-Teeples et al., 2015). These master switches together turn on the downstream TFs to activate (via MYB20, MYB42, MYB43, MYB58, MYB63, and MYB85) or repress (via MYB4) lignification (Zhong et al., 2011; Geng et al., 2020a, 2020b). In addition to the TFs, the Mediator complex maintains phenylpropanoid homeostasis via bridging the TFs and the transcriptional machinery. Disruption of Mediator subunits MED5a and MED5b (MED5a/b) in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) leads to increased levels of phenylpropanoids and transcripts of the biosynthetic genes involved (Bonawitz et al., 2012, 2014). Posttranslationally, four Kelch-repeat-containing F-box (KFB) proteins mediate the proteolytic degradation of PAL, controlling the entry step for phenylpropanoid production (Zhang et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2015a, 2015b). Similarly, another KFB protein (KFBCHS) targets chalcone synthase (CHS), the enzyme that catalyzes the first committed step for flavonoid production, to regulate the biosynthesis of anthocyanins and flavonols (Zhang et al., 2017a, 2017b).

Alterations in the abundance of lignin biosynthetic gene transcripts lead to changes in enzyme activities and subsequent metabolite accumulation (Rohde et al., 2004; Li et al., 2015). At the same time, changes in phenylpropanoid content can in turn result in differential gene expression in plants. For example, it has been shown that trans-cinnamate, the product of PAL, inhibits the transcription of three PAL genes in bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) (Mavandad et al., 1990). cis-Cinnamate, readily derived from trans-cinnamate under UV irradiation, causes auxin-like phenotype and triggers induction of early auxin-responsive genes in Arabidopsis seedlings (Vanholme et al., 2019; El Houari et al., 2021a, 2021b). Abolition of MED5a/b expression in C3′H-deficient mutants rescues their dwarf phenotype, an observation that has led to a model in which altered metabolites levels are sensed directly or indirectly by Mediator to influence gene expression (Bonawitz et al., 2014). Furthermore, glucosinolate intermediates cause Mediator-dependent enhanced phenylpropanoid KFB gene expression with concomitant decreases in PAL and phenylpropanoid levels (Kim et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2020).

Genetic modification of the genes involved in lignification often leads to altered lignin content and/or composition (Chen and Dixon, 2007; Wang et al., 2015). Numerous studies of natural mutants or genetically manipulated plants have demonstrated that perturbations at each step of lignification result in global transcriptional reprogramming and shifts in primary and secondary metabolism (Rohde et al., 2004; Vanholme et al., 2012a, 2012b; Bonawitz et al., 2014). To investigate metabolic activities of the whole lignin biosynthetic pathway, we sought to obtain a picture of the global transcriptional alterations in response to defects in lignification. When combined with metabolome information, it can illuminate the impacts of pathway perturbations on carbon flux into, and within, the phenylpropanoid network. The rich collection of mutants makes Arabidopsis a good model in which to systematically study how blockage in particular steps of lignification influences gene expression and carbon re-allocation, like the systems biology approach previously employed linking microarray and metabolomic data from plants defective in ten lignin biosynthetic steps (Vanholme et al., 2012a, 2012b). Here we selected double mutants with stronger deficiency in PAL (pal1 pal2) (Rohde et al., 2004), and CAD (cadc cadd) (Anderson et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c), a 4CL1 mutant (4cl1) that is defective in the last step of the general phenylpropanoid metabolism (Li et al., 2015), and a mutant of the recently identified lignin biosynthetic gene CSE (cse-2) (Vanholme et al., 2013). We also included two allelic mutants of C4H (a severe mutant called reduced epidermal fluorescence 3-2 [ref3–2], and a moderate mutant ref3–3) (Schilmiller et al., 2009). Three mutants were chosen with different expression of F5H, a gene that determines the ratio of G and S lignin in plants (Meyer et al., 1998), namely a knockout mutant (fah1) enriched in G lignin, an over-expresser of F5H gene (C4H:F5H) enriched in S lignin, and a mutant that bypasses C3′H and expresses F5H from Selaginella moellendorffii (ref8 fah1 SmF5H) to generate mainly H and S lignin (Chapple et al., 1992; Meyer et al., 1998; Weng et al., 2010). Two of the remaining mutants, med5a/b, med5a/b ref8, are defective in the MED5 subunit of the Mediator complex and C3′H (ref8) (Bonawitz et al., 2014), and the final two are defective in ref2 (cyp83a1) a mutant of glucosinolate biosynthesis that accumulates reduced levels of phenylpropanoids as well as med5a/b ref2, a mutant combination that suppresses ref2 (Hemm et al., 2003).

We conducted transcriptome analysis using RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) in these selected mutants along with wild-type controls and surveyed their phenylpropanoid profiles. We show that the 13 perturbed mutant lines all exhibited transcriptional and metabolic responses to the genetic mutations, although most of the plants were morphologically indistinguishable from wild-type. Defects in lignin biosynthesis triggered systematic induction of genes involved in lignification and Phe supply; however, these genes were repressed in fah1 and cse-2. The similarity of gene expression patterns identified five subgroups of mutants with related but distinct metabolite accumulation. In addition to changes related to phenylpropanoid metabolism, these mutants exhibited transcriptional reprogramming associated with various stress responses. Combined, the transcriptome and metabolite data identified the molecular responses to perturbed lignin biosynthesis in plants that will provide further insights to analyze flux re-distribution.

Results

Phenylpropanoid pathway mutations lead to global changes in the Arabidopsis transcriptome

To investigate the system-wide effects of lignin perturbation on transcripts and metabolites in Arabidopsis, we selected 13 mutants together with wild-type for analysis. Plants were harvested 28 days after planting when the inflorescence stems were ∼8–20 cm high. We collected the basal 0.5–2 cm of the primary stems for RNA-seq analysis because lignin is being deposited rapidly in this tissue at this stage (Guo et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). We harvested comparable tissue for metabolite quantification the next day. At harvest, the morphology of most of the mutants was like wild-type, except for ref3-2, ref3-3, and ref8 fah1 SmF5H (Figure 1). Both ref3 mutants, defective in C4H, had narrow and down-curled leaves, a phenotype previously seen in high auxin mutants (Kim et al., 2011). ref3-3 was of similar stature to wild-type, whereas ref3-2 was dwarfed, as previously reported (Schilmiller et al., 2009). Like ref3-2, ref8 fah1 SmF5H was also substantially shorter than wild-type (Weng et al., 2010). The cse-2 mutant was morphologically similar to wild-type when we sampled the basal stems (Figure 1), although it has a dwarf phenotype at maturity (Vanholme et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Growth phenotype of 28-day-old wild-type Arabidopsis and plants with perturbed lignification.

For the RNA-seq experiment, we included eight replicates of wild-type controls and four replicates for each mutant. After the transcript reads were mapped to the Arabidopsis genome, the whole dataset contained 20,974 expressed genes. Preliminary analysis using STRING (von Mering et al., 2005) of the 50 genes with highest counts across all samples revealed that these genes function in lignin biosynthesis, photosynthesis, glucosinolate biosynthesis, S-adenosylmethionine biosynthesis, and cellulose biosynthesis (Supplemental Figure S1). Indeed, the major isoforms of lignin biosynthetic genes showed high expression among all expressed genes in wild-type plants (Supplemental Table S1). These observations suggest that the basal stem segments analyzed in these experiments were undergoing active lignification.

To examine the data quality of the replicates and similarity of the expression profiles of all the samples, we performed principal component analysis (PCA) with the transcriptome data of individual samples (Figure 2). The first two principal components (PCs) together explained ∼60% variance. Interestingly, the eight wild-type replicates clustered less tightly than the mutants on PC1 and PC2. This result demonstrated that some variance existed among wild-type. The mutants of the same genotypes clustered together, indicating that they were distinguishable based on their transcriptome profiles. pal1 pal2, fah1, 4cl1, cse-2, and ref2 samples were distributed near to the wild-type samples (Figure 2), indicating that their overall expression profiles are similar to the wild-type controls. The two ref3 allelic mutants were close to each other and separated from the wild-type samples on PC1. An independent PCA analysis with only wild-type, ref3–2, and ref3–3 showed that the ref3–3 samples, from the weaker of the two mutants (Schilmiller et al., 2009), were closer to wild-type on PC1 than those from ref3–2 (Supplemental Figure S2) suggesting that the more severe defect in C4H in ref3–2 caused greater changes in the transcriptome than those seen in ref3–3. C4H:F5H, cadc cadd, ref8 fah1 SmF5H clustered close to one another, indicating they share similar changes in gene expression patterns (Figure 2). The three mutants containing med5 mutations formed another subgroup, suggesting that alterations in genes directly or indirectly regulated by MED5 differentiated the samples from all other genotypes. A separate PCA of only the three med5-containing mutants with wild-type revealed that they were separated from each other on PC2 (Supplemental Figure S3), indicating distinct expression patterns caused by the additional mutation in REF8 or REF2. To independently evaluate the PCA-based clustering results between individual samples and identify their similarity, we clustered samples based on the Euclidean distance of all genes (Supplemental Figure S4). Like the PCA result, the eight wild-type samples were clustered into two groups containing different mutants, again showing variance among the replicates. pal1 pal2, fah1, 4cl1, cse-2, and ref2 samples were closely clustered with wild-type samples. ref3–3 samples were more similar to wild-type than ref3–2, again suggesting that the weak allele of C4H caused fewer and/or more subtle changes than the strong allele.

Figure 2.

PCA analysis of expressed genes in RNA-seq data from individual samples of wild-type and the perturbed plants. The values were determined with log transformed transcript counts. The first two principal components were plotted here. Percentage on x- and y-axes showed the variance explained by PC1 and PC2, respectively.

Genes involved in phenylpropanoid metabolism are mis-expressed in mutants with perturbed lignification

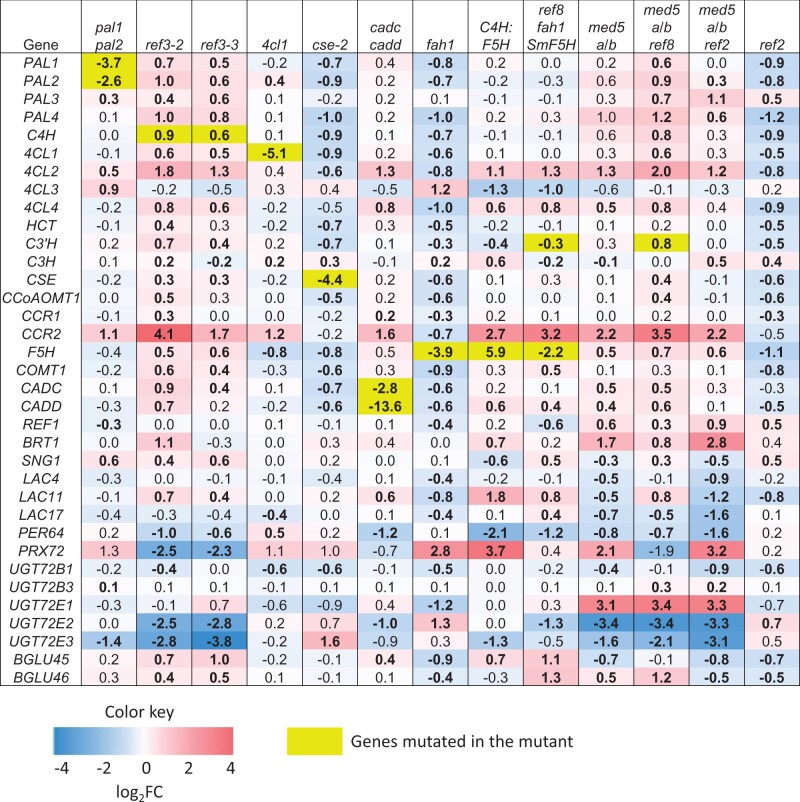

To closely examine the effect on the transcript levels of genes of the lignin biosynthetic pathway, we compared the expression of every gene in each mutant to wild-type and extracted the log2 fold change (log2FC) for target phenylpropanoid genes (Figure 3). The expression of mutated genes in the T-DNA mutants (pal1 pal2, 4cl1, cse-2, and cadc cadc) and fah1 (harboring a nonsense mutation that is known to trigger nonsense-mediated decay (Chiba and Green, 2009)) was significantly reduced (Figure 3). ref3–2, ref3–3, and ref8 mutants, isolated from an ethyl methanesulfonate mutated population, each contain missense mutations (Franke et al., 2002; Schilmiller et al., 2009), but unlike fah1, the corresponding transcripts showed increased levels (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Expression of lignin biosynthetic genes in the RNA-seq data. Values are log2FC of expression in mutant compared to wild-type. Bold indicates the value is significant (P-value cutoff of 0.05).

In the biosynthetic mutants analyzed, transcript abundance of the rest of the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic genes was increased or not changed, except for in cse-2, fah1, and ref2, which showed decreased levels of transcripts of most of the other genes in the pathway. In pal1 pal2, PAL3 was slightly upregulated. Although it has been reported that 4CL1 was induced in pal1 pal2 in the ecotype of C24 (Rohde et al., 2004), we found that 4CL2 and 4CL3 instead exhibited higher induction in Columbia-0 (Col-0) (Figure 3). The ref3 mutants showed elevated levels of transcript for most of the other lignin biosynthetic genes. In med5a/b, med5a/b ref8, and med5a/b ref2, phenylpropanoid biosynthetic genes showed increased expression, in line with the repressive role of MED5a/b in pathway homeostasis (Bonawitz et al., 2014; Dolan et al., 2017). Although the suppression of phenylpropanoid metabolism in ref2 is thought to occur primarily through the degradation of PAL enzymes (Kim et al., 2020), the transcript levels of all the major isoforms of lignin biosynthetic genes in ref2 were decreased, suggesting additional modes of downregulation of the phenylpropanoid pathway may occur in this mutant. Among the differentially expressed lignin biosynthetic genes, PAL2, 4CL2, 4CL4, and CCR2 displayed more substantially altered transcription in more mutants than their respective homologs. 4CL3, with a dominant role in flavonoid biosynthesis (Li et al., 2015), was induced in fah1 but repressed in C4H:F5H, in contrast to the other 4CL isoforms (Figure 3). This type of phenomenon may be explained by the fact that genetically redundant paralogs are often subject to differential regulation (Kondrashov, 2012; Weng, 2014).

Disruption in a number of LAC and PRX genes involved in the polymerization of monolignols results in decreased lignin content as well as altered soluble phenylpropanoids in plants (Berthet et al., 2011; Herrero et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2013). In our mutants, defects in lignin biosynthetic genes caused altered expression of LAC4, LAC11, LAC17, PRX64, and PRX72 (Figure 3). Interestingly, in med5a/b, med5a/b ref8, and med5a/b ref2, the three LAC genes and PRX64 were downregulated, indicating that in wild-type plants Mediator activates their expression, distinct from the role it plays in regulating monolignol biosynthetic genes. The repression of monolignol biosynthetic genes and activation of LAC and PRX64 may together suppress the accumulation of soluble phenylpropanoids.

Glycosylation of phenylpropanoids by UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs) and hydrolysis of glycosides by β-glucosidases (BGLU) maintain homeostasis of hydroxycinnamic acids and monolignols in plants (Lim et al., 2001, 2005; Lanot et al., 2006; Baldacci-Cresp et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2016; Speeckaert et al., 2020; Chapelle et al., 2012). Mutants of UGT72B and UGT72E family genes accumulate altered levels of lignin and glycosylated phenylpropanoids (Lin et al., 2016; Baldacci-Cresp et al., 2020). Analysis of these genes in our dataset revealed substantial changes in the expression of UGT72E1, UGT72E2, UGT72E3, BGLU45, and BGLU46 when lignification is perturbed. UGT72E2 and UGT72E3 were downregulated, whereas BGLU45 and BGLU46 were upregulated in both ref3–2 and ref3–3, probably to accommodate the decreased availability of the metabolite substrates (Simpson et al., 2021). UGT72E1 exhibited substantially increased expression, whereas UGT72E2 and UGT72E3 had decreased expression in three med5a/b containing mutants, suggesting these gene isoforms are regulated differently.

We next examined the genes involved in the aromatic amino acid biosynthesis to determine whether the production of Phe was affected at the transcriptional level in any of the mutants examined (Tzin and Galili, 2010; Maeda and Dudareva, 2012). Hierarchical clustering of the expression of the shikimate and lignin pathway genes showed that genes from both pathways were mixed in the clusters (Figure 4) and were similarly upregulated in ref3–2, ref3–3, cadc cadd, med5a/b, mefd5a/b ref8, and med5a/b ref2, but downregulated in cse-2, fah1, and ref2 (Figure 4; Supplemental Figure S5). Interestingly, ref3–2 clustered closer to meda/b ref8 than ref3–3, perhaps due to their more substantial changes in gene expression. pal1 pal2 showed a slight increase in the expression of 3-DEOXY-D-ARABINO-HEPTULOSONATE 7-PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE 2 (DAHPS2), AROGENATE DEHYDRATASE 2 (ADT2), and ADT3. Like pal1 pal2, cadc cadd had a modest enhancement in the expression of DAHPS2, 3-DEHYDROQUINATE SYNTHASE, SHIKIMATE KINASE 1, and four of the six ADT genes including the major isoform ADT4 and ADT5 (Corea et al., 2012), but a reduction in steady state mRNA levels for ADT3 and CHORISMATE MUTASE 2. ref3–2 exhibited more substantial changes than ref3–3 for the three DAHPS genes and SK2, and the major ADT genes. med5a/b, med5a/b ref8, and med5a/b ref2 exhibited upregulation of the genes responsible for the synthesis of chorismate and the four ADT genes that were also upregulated in cadc cadd, whereas the three mutants all showed decreased transcripts of ADT1, an isoform with lower expression than ADT4 and ADT5 in wild-type. On the other hand, cse-2, fah1, and ref2 displayed reduced expression in genes involved in every step except chorismate synthase. Despite the slight upregulation of DAHPS2 and ADT2 in both fah1 and ref2, the repressed transcription of the shikimate biosynthetic genes in the three mutants was consistent with the suppression of lignin biosynthetic genes in these mutants (Figure 4). These results suggest that transcription of genes for Phe biosynthesis and subsequent lignification are coordinated in rapidly lignifying stem tissue.

Figure 4.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of the shikimate and lignin pathway genes from 13 mutants compared with wild-type. Log2FC values for 47 genes were used to generate the heat map and ward.D2 method was used for clustering both the genes and the mutants.

We then evaluated the transcript abundance of the TFs known to be involved in regulating lignin biosynthetic genes (Figure 5; Zhong et al., 2008, 2011; Taylor-Teeples et al., 2015; Geng et al., 2020a, 2020b). cse-2, fah1, and ref2 showed repression in activators such as MYB42, MYB58, MYB63, and MYB85, but activation of the repressor MYB4 except in fah1. In contrast, in ref3–2, ref3–3, C4H:F5H, and ref8 fah1 SmF5H, increased transcript abundance was observed for numerous transcription activators, but decreased mRNA levels were evident for MYB4. The opposite changes in expression of these TFs may lead to disparate changes in the expression of biosynthetic genes in cse-2, fah1, ref2 versus ref3–2, ref3–3, cadc cadd, C4H:F5H, and ref8 fah1 SmF5H. MED5a and MED5b as co-regulators repress the transcription of genes in lignin biosynthesis, but only subtle changes in their expression were seen in the mutants (Figure 5). In ref3–2, cadc cadd, and C4H:F5H, the only three mutants in which both MED5 genes were statistically altered in expression, MED5a was downregulated but MED5b was upregulated.

Figure 5.

Expression of genes involved in regulating phenylpropanoid metabolism in the RNA-seq data. Values are log2FC of expression in mutant compared to wild-type. Bold indicates the value is significant (P-value cutoff of 0.05). Yellow background indicates genes mutated in the line.

KFB1, KFB20, KFB39, and KFB50 are involved in the proteasome-mediated degradation of PAL and thus posttranslationally control the entry point enzyme for phenylpropanoid metabolism (Zhang et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2015a, 2015b). In pal1 pal2, KFB39 was substantially repressed, which may reduce PAL turnover and partially alleviate the impact of the PAL mutations (Figure 5). KFB39 and KFB50 were downregulated in the ref3 mutants, 4cl1, and C4H:F5H and even more strongly in the med5a/b mutants (Figure 5) consistent with the higher accumulation of phenylpropanoids in the Mediator subunit mutants (Figure 5; Bonawitz et al., 2012, 2014; Kim et al., 2020). Disruption of MED5a/b in ref2 rescued the decreased transcript abundance of KFB20 in ref2 (Figure 5) as previously reported (Kim et al., 2020). cse-2, with reduced expression of the PAL genes, had an over two-fold increase in the transcripts of KFB39 (Figure 5). In contrast, fah1, which also had lower expression of the PAL genes, showed reduced transcript accumulation of all four KFB genes. With the exception of the cse-2 data, these results are consistent with a model in which KFB gene expression is modulated in a direction that tends to restore phenylpropanoid metabolite homeostasis.

DEGs in phenylpropanoid mutants identify multiple mis-regulated processes

The analysis described above revealed that phenylpropanoid biosynthetic mutants have system-wide changes in phenylpropanoid and shikimate pathway gene expression. To investigate the global impact of these mutations on the transcriptome, we compared the expression of all 20,974 expressed genes in our dataset and identified genes with at least a two-fold change in expression (false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.01) in each mutant (Supplemental Figure S6). In aggregate, 5,581 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified from the 13 mutants (Supplemental Table S2). The mutants close to wild-type on the PCA plot, including pal1 pal2, 4cl1, cse-2, fah1, and ref2 (Figure 3) had fewer than 1,000 DEGs, whereas more were observed in the other mutants. Among the phenylpropanoid pathway structural gene mutants, the highest number of DEGs (approximately 2,500) were observed in plants overexpressing F5H, although the med5a/b ref2 mutant had over 2,900.

To quantitatively examine the DEGs among the mutants, we performed Pearson’s correlation analysis using the log2FC of the 5,581 genes that were mis-regulated in aggregate (Figure 6). pal1 pal2, 4cl1, cse-2, fah1, and ref2 not only showed few DEGs, but also positively correlated DEG profiles, which suggested that common DEGs were similarly mis-expressed. Similarly, the mutants with more DEGs, namely ref3–2, ref3–3, cadc cadd, C4H:F5H, ref8 fah1 SmF5H, med5a/b, med5a/b ref8, and med5a/b ref2, also showed positively correlated DEG profiles among themselves, suggesting that DEGs shared between every mutant pair were generally mis-regulated in the same direction. Global changes in gene expression in fah1, and to a lesser extent in ref2, negatively correlated with that in the mutants with more DEGs. To identify the DEGs that contributed to these correlations, hierarchical clustering analysis was conducted to group both mutants and the 5,581 DEGs (Figure 7; Dolan et al., 2017). The five mutants with fewer DEGs (designated subgroups A and B) clustered together and apart from the other eight with more DEGs (subgroups C, D, and E). pal1 pal2, fah1, and ref2 grouped together, with decreased transcripts for gene Clusters 2–8 and increased transcripts for gene Clusters 13–15. Genes in these clusters exhibited opposite changes in the eight mutants with higher numbers of DEGs, resulting in a negative correlation in gene expression profiles with fah1-2 and ref2. As seen before in Figure 6, changes in gene expression were similar in ref3–2 and ref3–3, with more substantial changes in the stronger allele ref3–2 (Figure 7). The eight mutants in subgroups C, D, and E had similar changes in DEGs, with generally increased transcription for genes in Clusters 1–7, and decreased transcription in gene Clusters 14–16. Upregulated genes included those involved in various defense responses and salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and abscisic acid (ABA) signaling, and repressed genes included those responsible for photosynthesis, lipid catabolism, and auxin signaling (Supplemental Table S3; Figure 7). Five subgroups with related DEG profiles emerged from the hierarchical clustering analysis (Figure 7), providing a basis for detailed analysis of the mutant subgroups for their transcriptome and phenylpropanoid metabolite content.

Figure 6.

Pearson’s correlation (r) of gene expression profiles. Values were obtained based on log2FC of 5,581 genes that were up or downregulated more than two-fold in at least one mutant. Size of circle represents the absolute values of r and color code represents the value of r indicated as the scale on the right. Blank wells mean that the correlation is not significant based on P-value cutoff of 0.01.

Figure 7.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of substantial DEGs from 13 mutants compared with wild-type. Log2FC values for 5,581 DEGs with at least two-fold changes in at least one mutant were used to generate the heat map and ward.D2 method was used for clustering. GO terms of BPs for 16 clusters are shown on the right. Black color indicates statistically significant (FDR < 0.01) and gray color indicates FDR between 0.01 and 0.1.

Comparison of metabolites and DEGs in subgroups of mutants

To assess how the perturbations in lignification affect the levels of phenylpropanoids, we extracted soluble metabolites from the basal stem tissue of wild-type and the 13 mutant plants and quantified 18 selected compounds by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) (Jaini et al., 2017), which revealed substantial differences in the accumulation of numerous phenylpropanoids (Supplemental Table S4), consistent with previous reports (Vanholme et al., 2012a, 2012b; Simpson et al., 2021). To probe the extent to which transcript alterations associated with changes in metabolite accumulation, we analyzed each of the five subgroups in detail. We compared DEGs in mutants within the subgroup whose expression change were two-fold or more, performed functional analysis of the common genes, and compared their phenylpropanoids profiles among the subgroup mutants and wild-type.

Subgroup A: pal1 pal2, fah1, and ref2

pal1 pal2, fah1, and ref2 constituted subgroup A with 14 and 44 commonly upregulated and downregulated DEGs, respectively, and a more substantial overlap of downregulated genes in fah1 and ref2 (Supplemental Figure S7, A and B). The 14 upregulated genes were enriched in those involved in carbon fixation but there was no significant enrichment (FDR < 0.01) in the 44 downregulated genes (Supplemental Table S5). We analyzed the 338 repressed genes shared by fah1 and ref2 and found significant enrichment for genes involved in transcription regulation, ethylene-activated signaling pathway, and response to chitin and cold (Supplemental Table S5). Among these genes was a Kelch Domain F-Box protein that targets CHS (Zhang et al., 2017a, 2017b), the enzyme that catalyzes the first committed step for flavonoid production, suggesting altered posttranslational regulation of flavonoid metabolism in fah1 and ref2.

pal1 pal2 accumulated 660-nmol g−1 FW Phe, 25 times of that in wild-type, consistent with the enhanced Phe accumulation seen in the double mutant in the Arabidopsis ecotype C24 (Rohde et al., 2004). This substantial accumulation of Phe was unique to pal1 pal2, whereas the remaining compounds downstream of PAL showed similar or reduced levels compared to wild-type, presumably due to decreased flux into the pathway. All three mutants in this subgroup showed lower levels of sinapaldehyde and sinapyl alcohol (Supplemental Figure S7C), consistent with the inability of fah1 mutants to make syringyl-substituted compounds (Chapple et al., 1992; Meyer et al., 1998), lower levels of S lignin in ref2 (Hemm et al., 2003) and reduced transcript abundance of F5H and COMT1 (Figure 3). They also exhibited reduced concentrations of coniferaldehyde, consistent with an overall reduction of flux toward lignin precursors. ref2 and fah1 accumulated ferulate, instead of the immediate substrate of F5H, coniferaldehyde. This observation suggests that re-distribution of flux occurs by oxidation of the hydroxycinnamaldehyde to the hydroxycinnamate possibly by the hydroxycinnamaldehyde dehydrogenase encoded by REF1 (Nair et al., 2004), or by hydroxylation and subsequent methylation of p-coumarate via 4-COUMARATE 3-HYDROXYLASE (Barros et al., 2019).

Subgroup B: ref3-2 and ref3-3

ref3–2 is a strong missense allele of C4H that exhibits stunted growth, whereas ref3–3 is a weaker allele that develops normally (Figure 1; Schilmiller et al., 2009). As mentioned previously (Supplemental Figure S6; Figure 7), there were more DEGs in ref3–2 and DEGs with larger fold changes compared to ref3–3 (Supplemental Figures S8, A and B). Analysis of the common upregulated genes revealed enrichment for response to protein phosphorylation, response to SA, defense response to bacteria and to fungus, and flavonoid biosynthetic process (Supplemental Table S5). Among those genes were DOWNY MILDEW RESISTANT 6 (DMR6) and DMR6-LIKE OXYGENASE 1, encoding SA 5-hydroxylase and SA 3-hydroxylase, respectively, which are induced by SA treatment and maintain SA homeostasis in plants (Zhang et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2017a, 2017b). The 387 common downregulated genes showed enrichment in cell wall organization, including a number of xyloglucan:xyloglucosyl transferase genes and expansin genes (Supplemental Table S5).

Consistent with the lower lignin phenotype of ref3 mutants reported before (Schilmiller et al., 2009), the amounts of caffeoyl CoA and sinapaldehyde were lower in ref3–2 and both ref3 mutants showed decreased levels of p-coumaraldehyde and coniferaldehyde (Supplemental Figure S8C). Despite their diminished C4H activity and lower lignin content, both mutants did not accumulate detectable levels of free cinnamate, consistent with previous observations that they instead synthesize cinnamate conjugates (Simpson et al., 2021).

Subgroup C: 4cl1 and cse-2

Both 4cl1 and cse-2 mutants had fewer upregulated DEGs than downregulated DEGs (Supplemental Figure S9, A and B). The majority of commonly downregulated genes in 4cl1 and cse-2 were involved in stress responses, including a number of WRKY, ERF, CBF TFs (Supplemental Table S5).

Both mutants accumulated the phenylpropanoid intermediate that is the substrate for their defective enzyme. 4cl1 mutants contained a higher level of p-coumarate and ferulate (Supplemental Figure S9C), consistent with the mutant’s 80% reduction in 4CL activity (Li et al., 2015). Similarly, caffeoyl shikimate levels were high in the cse-2 mutant (Supplemental Figure S9C). In 4cl1 and cse-2, coniferaldehyde and sinapaldehyde levels were lower, but ferulate and sinapate levels were much higher, suggesting oxidation of the hydroxycinnamaldehydes to hydroxycinnamates, similar to the re-distributed pools seen in the fah1 and ref-2 mutants. REF1, encoding the aldehyde dehydrogenase that catalyzes this conversion (Nair et al., 2004), was not altered in expression in either mutant (Figure 3). Similarly, there was only a modest increase in transcript levels of C3H in 4cl1 and cse-2 suggesting that it is unlikely to contribute to the higher accumulation of ferulate and sinapate by hydroxylation of p-coumarate to caffeate (Barros et al., 2019).

Subgroup D: C4H:F5H and cadc cadd

The C4H promoter is very effective in driving the overexpression of F5H (Meyer et al., 1998) such that its transcript was ∼60 times higher than in wild-type and F5H became the most highly expressed gene in the stem (Figure 3). Interestingly, despite their relatively normal stature, cadc cadc and C4H:F5H both exhibited large numbers of DEGs, many of which were commonly mis-regulated (Supplemental Figure S10, A and B). Further analysis revealed that the common upregulated genes in cadc cadc and C4H:F5H showed enrichment for responses to detoxification, glutathione metabolic process, and the common downregulated genes were related to auxin response and its polar transport, cell wall biogenesis and organization (Supplemental Table S5).

CAD and F5H compete for the common substrate coniferaldehyde in lignin biosynthesis. When the major isoforms of CAD were knocked out in cadc cadd, the only metabolite changes observed were the expected increases in coniferaldehyde and decreases in coniferyl alcohol content (Supplemental Figure S10C). In C4H:F5H, coniferyl alcohol level was lower than in wild-type suggesting that overexpression of F5H depletes pools of the enzyme’s substrate, but no significant difference was seen for other phenylpropanoids (Supplemental Figure S10C).

Subgroup E: med5a/b, med5a/b ref8, and med5a/b ref2

Disruption of MED5a/b results in increased transcripts of lignin biosynthetic genes and enhanced levels of phenylpropanoids in rosettes (Bonawitz et al., 2012, 2014; Kim et al., 2020). We observed the same trend for transcripts and intermediates for lignin biosynthesis in the stem tissue from med5a/b, med5a/b ref8, and med5a/b ref2 (Supplemental Figure S11). In addition, the shikimate pathway was transcriptionally activated, potentially increasing capacity for Phe synthesis (Figure 4). Many genes were commonly differentially expressed in all of these lines, presumably dictated by the common lack of MED5a/b (Supplemental Figures S6 and S11A). An enrichment in SA response and various defense responses toward external stresses was identified from functional analysis of the commonly upregulated genes. Among the 440 genes were DMR6 and DMR6-LIKE OXYGENASE 1, that were also upregulated in the ref3 mutants. Analysis of the shared downregulated genes showed an enrichment in auxin-regulated growth processes, cell wall, and cell membrane biogenesis and degradation. A substantial number of these genes encode secreted proteins, including glycoproteins and expansins (Supplemental Table S5).

In these three mutants, Phe content was reduced by ∼50%, whereas there was increased accumulation of some of phenylpropanoids (Supplemental Figure S11C). The decrease in Phe content is consistent with the suppressed expression of KFB39 and KFB50, which leads to enhanced levels of PAL and increases in phenylpropanoid content (Zhang et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2015a, 2015b; Kim et al., 2020). The med5a/b double mutant had increased levels of monolignols, potentially due, at least in part, to the decreased transcript levels of the three LACCASE genes and PRX64 involved in lignification (Figure 3), which could be a reason that med5a/b does not deposit more lignin than wild-type (Bonawitz et al., 2014). More substantial reductions in the LACCASE genes and PRX64 were seen in med5a/b ref2, consistent with its hyper-accumulation of p-coumaryl alcohol and coniferyl alcohol. med5a/b ref8 exhibited higher accumulation of p-coumaryl derivatives because C3′H is blocked in that line, consistent with its deposition of lignin largely derived from H subunits (Supplemental Figure S11C; Bonawitz et al., 2014).

Plants altered in F5H expression: fah1, C4H:F5H, and ref8 fah1 SmF5H

In addition to the subgroups derived from the hierarchical analysis, we also compared fah1, C4H:F5H, and ref8 fah1 SmF5H because they all have perturbations at the F5H step (Supplemental Figure S12). As expected, F5H transcript was absent in fah1 but highly expressed in C4H:F5H (Figure 3). ref8 fah1 SmF5H is deficient in C3′H and F5H, but expresses an independently evolved F5H from Selaginella moellendorffii that catalyzes both 3- and 5-hydroxylation (Weng et al., 2010). The mutant accumulates mainly H and S lignin (Weng et al., 2010). As seen in Figure 6, a majority of shared DEGs between fah1 and C4H:F5H showed changes of opposite directions (red dots in Supplemental Figure S12A), fewer showed changes of the same direction, consistent with their opposite changes in F5H activity. Similarly, in a recent microarray analysis of transcriptome in fah1 and C4H:F5H, only six and eight genes were found to be both upregulated or both downregulated compared to wild-type, respectively (Gallego-Giraldo et al., 2018). The same trend was observed between fah1 and ref8 fah1 SmF5H. In contrast, common DEGs between C4H:F5H and ref8 fah1 SmF5H overall were mostly misregulated in the same direction (Supplemental Figure S12A). We thus examined the 70 DEGs with decreased expression in fah1 and increased in C4H:F5H and ref8 fah1 SmF5H, and the 50 DEGs with increased expression in fah1 and decreased in C4H:F5H and ref8 fah1 SmF5H. We found enrichment for genes involved in extracellular processes and secretion (Supplemental Table S5). C4H:F5H exhibited substantial overexpression of genes associated with responses to aphid feeding, encoding a cytochrome P450 (CYP81D11) and two glutathione S-transferase, that were identified in a previous study (Gallego-Giraldo et al., 2018).

Consistent with the mutation in C3′H, ref8 fah1 SmF5H accumulated higher levels of p-coumarate, p-coumaroyl shikimate, and p-coumaraldehyde, but not p-coumaryl alcohol presumably due to the ability of the dual meta-hydroxylation activity of SmF5H to consume p-coumaryl derivatives and synthesize G and S lignin (Weng et al., 2010; Supplemental Figure S12C). In addition, ref8 fah1 SmF5H had substantial increase of sinapate despite a lower transcript level of REF1 that encode the aldehyde dehydrogenase (Figure 3).

Expression of gene clusters correlates with phenylpropanoid accumulation

In addition to the detailed analysis of DEGs and metabolites in the subgroups, we further created a system-wide Pearson correlation matrix of pairwise comparisons between gene expression and phenylpropanoid content across all 14 genotypes. Genes and metabolites with strong correlation are potentially functionally related in vivo, such as genes encoding enzymes that catalyze the synthesis or degradation of metabolites or signaling molecules that regulate gene expression (Saito et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2012; Wisecaver et al., 2017). A total of 2,987 genes were identified with significant correlation (|r| ≥ 0.7, P < 0.05) with at least one of the 18 metabolites measured (Supplemental Table S6). Hierarchical clustering analysis of the Pearson correlation coefficients grouped the 2,987 genes into 6 clusters (Figure 8) and the 18 metabolites into two major subgroups. One subgroup comprised metabolites mostly upstream of HCT, namely Phe, p-coumarate, p-coumaroyl CoA, p-coumaryl alcohol, p-coumaroyl shikimate, caffeate, caffeoyl shikimate, and ferulate. The other subgroup included downstream pathway intermediates as well as shikimate, free CoA, and p-coumaraldehyde. Not surprisingly, a few phenylpropanoids close to each other in the pathway exhibited similar correlation profile, suggesting similar alteration of their contents in the mutants. For example, p-coumaroyl CoA, p-coumaroyl shikimate, and p-coumaryl alcohol clustered together and their accumulation positively correlated with gene Cluster 3 and negatively correlated with Cluster 6.

Figure 8.

Hierarchical clustering of Pearson correlation analysis between metabolite accumulation and gene expression in all genotypes. Out of 20,974 expressed genes, 2,987 genes have significant correlation (|r| ≥ 0.7, P < 0.05) with at least one metabolite. The rows and columns of the heap map are clusters of genes and metabolites, respectively, generated using ward.D2 method. GO terms of BPs and cellular compartments (FDR < 0.01) for six clusters are shown on the right.

Sinapaldehyde exhibited a strong positive and negative correlation with genes in Clusters 1 and 4, respectively. Functional analysis revealed that genes in Cluster 1 were associated with ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation and toxin catabolism, whereas genes in Cluster 4 were associated with cell division, cell cycle, and microtubule-based movement (Supplemental Table S6). About 29% of the 594 genes in Cluster 1 were upregulated in C4H:F5H, and 46% of the 684 genes in Cluster 4 were downregulated in C4H:F5H (Supplemental Tables S3 and S6), suggesting that the substantial hyper-accumulation of sinapaldehyde in C4H:F5H contributed to the correlation result (Supplemental Figure S12). Cluster 2 was enriched in genes functioning in glucosinolate biosynthesis, methionine biosynthesis, and iron–sulfur cluster assembly and displayed strong positive correlations with free shikimate, CoA, feruloyl CoA, caffeoyl CoA, coniferyl alcohol, p-coumaraldehyde, and sinapyl alcohol. Genes in Cluster 3 were also positively correlated with these metabolites as well as p-coumaroyl CoA, p-coumaryl alcohol, and p-coumaroyl shikimate. Functional analysis of Cluster 3 identified genes encoding subunits of ribosome and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 complex. In contrast to Clusters 2 and 3, Cluster 5 was composed of genes negatively correlated with shikimate, free CoA, feruloyl CoA, caffeoyl CoA, coniferyl alcohol, p-coumaraldehyde, and sinapyl alcohol, whereas Cluster 6 of genes negatively correlated with p-coumaroyl CoA, p-coumaryl alcohol, and p-coumaroyl shikimate. Although no significant gene ontology (GO) was identified in Cluster 5, it contained a list of genes encoding enzymes involved in acetyl CoA metabolism including acyl-activating enzyme 17, acyl-CoA oxidase 2 (ACX2), ACX3, and ACX4, suggesting their relationship with acyl-CoA metabolism resulted in them being negatively correlated with free CoA, caffeoyl CoA, and feruloyl CoA accumulation. Functional analysis of Cluster 6 identified enrichment of genes related to the chloroplast.

Discussion

Plants tightly control lignin biosynthesis at multiple levels to allocate carbon toward this major carbon sink (Zhong et al., 2008; Bonawitz and Chapple, 2010; Zhang et al., 2013a, 2013b; Bonawitz et al., 2014; Taylor-Teeples et al., 2015). Despite this quantitative control, there is a great deal of flexibility in monomer composition. In addition to the canonical lignin monomers p-coumaryl alcohol, coniferyl alcohol, and sinapyl alcohol, a range of available phenylpropanoids such as coniferaldehyde, and sinapaldehyde, tricin, and monolignol hydroxycinnamate esters can function as lignin subunits (Boerjan et al., 2003; Vanholme et al., 2012a, 2012b; Wang et al., 2015). Despite the plasticity of lignin composition, modifications of lignin biosynthesis can lead to global alterations in transcription and metabolite profiles (Rohde et al., 2004; Vanholme et al., 2012a, 2012b; Bonawitz et al., 2014; Gallego-Giraldo et al., 2018), and in some cases these changes have impacts on plant growth, development, and defense (Xie et al., 2018; Muro-Villanueva et al., 2019). In this study, we conducted genome-wide transcriptome analysis and phenylpropanoid profiling in Arabidopsis plants of 14 different genotypes to understand how these plants respond to genetic perturbations of lignification. Our molecular phenotyping revealed substantial changes at the transcript and metabolic levels in mutants with perturbed lignin biosynthesis, even when there were no obvious differences in growth.

Coordinated regulation of shikimate pathway and phenylpropanoid pathway

Consistent with previous reports (Rohde et al., 2004; Vanholme et al., 2012a, 2012b; Bonawitz et al., 2014; Gallego-Giraldo et al., 2018), we found that genetic manipulation at each step of lignin biosynthesis affected the expression of other genes in the pathway. Interestingly, most of the genes in the shikimate pathway were upregulated in ref3–2, ref3–3, med5a/b, med5a/b ref8, and med5a/b ref2 and downregulated in cse-2 and fah1, in the same direction as lignin biosynthetic genes (Figure 4). These observations suggest that the supply of Phe and lignification are tightly coordinated in plants at the transcript level, consistent with previous co-expression analysis of microarray data (Gachon et al., 2005; Vanholme et al., 2012a, 2012b). Upregulation of genes in the shikimate and flavonoid pathways has been reported in transgenic tomato fruits that express the Arabidopsis TF MYB12 (Zhang et al., 2015a, 2015b). Similarly, consistent suppression of the shikimate and phenylpropanoid pathway genes occurs in the Arabidopsis nst1 nst3 mutant, which is deficient in the master TFs regulating secondary cell wall formation (Mitsuda et al., 2007). Our RNA-seq data show that the expression of MYB42 and its homologs MYB20, MYB43, and MYB85, all of which are activators of Phe and lignin biosynthesis (Zhong et al., 2008; Zhong and Ye, 2009; Zhong et al., 2011), were decreased in fah1 and ref2, and the expression of MYB4, a repressor TF of general phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (Zhong and Ye, 2009), increased in cse-2 (Figure 5). In addition, the induction of the pathway genes in ref3 and the med5a/b containing mutants was consistent with the increased transcript abundance of the activator MYB42 and lower transcript abundance of the repressor MYB4 (Figure 5). These data suggest that these MYB TFs may be involved in the regulation of Phe synthesis, its conversion to downstream products, and the metabolic phenotypes seen in the mutants employed in this study.

Expression of KFB genes maintains phenylpropanoid metabolic homeostasis

KFB proteins interact with enzymes in the phenylpropanoid pathway and regulate their degradation via the ubiquitin-26S proteasome pathway (Zhang et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2015a, 2015b, 2017a, 2017b, 2020; Feder et al., 2015; Zhang and Liu, 2015). In Arabidopsis, four KFBs redundantly regulate the turnover of PAL enzymes and mediate the accumulation of soluble phenylpropanoids and lignin (Zhang et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2015a, 2015b). In both Camelina sativa and Arabidopsis, cross-talk between aldoxime metabolism and the phenylpropanoid pathway occurs through regulation of KFBs expression and PAL activity (Kim et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Here we found that the expression of KFB39 and KFB50 were substantially decreased when lignin biosynthesis was perturbed, suggesting that they are regulated similarly to reduce the degradation of PAL (Figure 5) and increase its activity in the face of reductions of end products such as lignin and hydroxycinnamate derivatives (Zhang et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2015a, 2015b; Kim et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2020). Significant reduction in KFB39 and KFB50 expression in med5a/b, med5a/b ref8, and med5a/b ref2 suggests that MED5a/b functions as a coactivator for their expression. These data are consistent with that MED5a/b is required in ref2 and ref5 mutants to activate the expression of KFB39 and KFB50 to suppress phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (Kim et al., 2020). These results together indicate that posttranslational regulation of PAL enzymes by KFBs is coordinated with the existence of the homeostatic mechanisms to maintain phenylpropanoid metabolic flux.

In addition to PAL, CHS, the gateway enzyme for flavonoid biosynthesis, is ubiquitinated by KFBCHS for degradation in Arabidopsis. Both anthocyanins and kaempferol glycosides exhibit higher accumulation in KFBCHS mutants (Zhang et al., 2017a, 2017b). In rice (Oryza sativa) and muskmelon (Cucumis melo), KFBs have been identified to negatively impact flavonoid including anthocyanin, but the protein targets remain to be isolated (Shao et al., 2012; Feder et al., 2015; Xia et al., 2016). fah1 is anthocyanin deficient (Anderson et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c), but CHS and 4CL3, the 4CL paralog that has a dominant role in flavonoid biosynthesis (Li et al., 2015), showed increased expression in fah1 compared to wild-type (Figure 3; Supplemental Table S5). Similarly, the transcript level of KFBCHS was decreased in fah1 (Supplemental Table S5), potentially leading to decreased CHS degradation by the proteasome and higher CHS activity (Zhang et al., 2017a, 2017b). These data suggest that expression of CHS, 4CL3, and KFBCHS are all coordinated to mitigate the reduction of anthocyanin synthesis in fah1.

Global impact on transcription caused by perturbations in lignin biosynthesis

Differential gene expression analysis revealed that perturbations in lignin biosynthesis lead to system-wide transcriptional reprogramming, despite the normal growth of most of these mutants. The comparison of DEGs from all mutants and within subgroups sharing similar expression profiles illustrated substantial changes in diverse biological processes (BPs) and molecular functions (MFs) (Figure 7; Supplemental Tables S3 and S5). Responses to hormones including SA, ABA, JA, ethylene, and auxin are highlighted in the functions of DEGs identified in the mutants analyzed. It has been shown that alteration in phenylpropanoid metabolism leads to changes in: (1) SA accumulation in Arabidopsis, Artemisia annua, tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), and alfalfa (Medicago sativa) (Schoch et al., 2002; Gallego-Giraldo et al., 2011; Bonawitz et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2016); (2) auxin transport in Arabidopsis seedlings (El Houari et al., 2021a, 2021b); and (3) JA accumulation and signaling in Brassica napus (Islam et al., 2019). In turn, these hormones regulate the expression of lignin pathway genes and result in changed accumulation of phenylpropanoids in a variety of plants as a mechanism to defend against various abiotic and biotic stresses (Fraissinet-Tachet et al., 1998; Nugroho et al., 2002; Park et al., 2019; Crizel et al., 2020; Hildreth et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021). In our DEG profiles across mutants (Figure 7; Supplemental Table S3) and within subgroups (Supplemental Table S5), responses to hormones are accompanied by stress responses, such as cold acclimation as well as response to water deprivation highlighted in gene Clusters 5 and 7 in Figure 7. It has been shown that silencing CAD2 and CAD3 leads to higher sensitivity to drought in oriental melon (Cucumis melo var. makuwa) (Liu et al., 2020), and that elevated phenylpropanoids contribute to drought tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum) (Li et al., 2020) and apple (Malus domestica) (Geng et al., 2020a, 2020b). We identified more enrichment of genes involved in biotic stresses, including responses to bacteria, to fungus, to chitin in gene Clusters 1, 3, and 8, and in all Subgroups. These observations are consistent with previous reports showing, for example, that Arabidopsis fah1 and C4H:F5H exhibit increased transcription of defense genes and altered responses to bacteria and aphid inoculation (Gallego-Giraldo et al., 2018), citrus displays enhanced phenylpropanoid production in response to bacterial pathogens (Ference et al., 2020), and in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), de novo synthesis of phenolic compounds contributes to defense to fungus (Tugizimana et al., 2018). The substantial transcriptional changes to various stresses suggest profound connection between phenylpropanoid metabolism and the responses of plants to environmental changes.

In the stem tissue analyzed, expression of photosynthetic genes ranked high among all transcripts mapped and annotated (Supplemental Figure S1). Among them are Rubisco Small Subunit 1A (RBCS1A), Rubisco Activase, components of Light Harvesting Complex A and B. Surprisingly, transcript levels of RBCS1B, RBCS2B, and RBCS3B were all increased over two-fold in pal1 pal2, fah1, and ref2 (Supplemental Table S5), suggesting increased demand of carbon fixation and primary metabolism in these mutants. Increased expression of carbohydrate-related genes including RBCS3B has been reported in pal1 and pal2 mutants in Arabidopsis (Rohde et al., 2004). In contrast, transcript levels of these three RBCS subunits were decreased in cadc cadd, C4H:F5H, med5a/b containing mutants. It is not clear how transcription of these RBCS genes is affected in these mutants. Lignin accounts for 20%–30% of carbon fixed in land plants (Bonawitz et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015). When lignin biosynthesis is perturbed, some signaling mechanism may be triggered to fix more carbon and increase the carbon flux toward the pathway (Vanholme et al., 2012a, 2012b). More investigations are necessary to understand the molecular connection between the phenylpropanoid metabolism and transcriptional regulation of photosynthesis.

Linking altered transcription to changed accumulation of metabolites

Perturbation in lignification causes changes in soluble phenylpropanoid metabolite accumulation, lignin deposition, and often defects in plant growth and defenses (Bonawitz and Chapple, 2010; Xie et al., 2018; Muro-Villanueva et al., 2019). One model suggests that certain phenylpropanoids act as bioactive signaling molecules and their accumulation will lead to altered growth or defense responses, potentially through transcriptional reprogramming (Bonawitz et al., 2014; Muro-Villanueva et al., 2019; El Houari et al., 2021a, 2021b). Phenylpropanoid pathway genes are also often mis-regulated in lignin biosynthetic mutants (Rohde et al., 2004; Vanholme et al., 2012a, 2012b; Bonawitz et al., 2014). Consistent with these previous observations, pal1 pal2, ref3–2, ref3–3, 4cl1, cadc cadd as well as C4H:F5H all showed higher transcript abundance for phenylpropanoid structural genes. In contrast, cse-2 and fah1 showed the opposite (Figures 3 and 7). fah1 exhibited reduced transcript abundance for genes in nearly every step of the lignin biosynthetic pathways and decreased accumulation of soluble phenylpropanoids (Figure 3; Supplemental Figure S7), yet its total lignin content is the same as wild-type (Chapple et al., 1992; Meyer et al., 1998). These results suggest that in fah1, expression of shikimate and phenylpropanoid genes does not determine the total carbon flux channeled toward lignin. Reduced accumulation of hydroxycinnamates and anthocyanins in fah1 has been reported previously and suggested to be the result of accumulation of phenylpropanoid(s) between C3′H and F5H that represses the pathway via a Mediator-dependent feedback mechanism (Anderson et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c). It has also been proposed that hyper-accumulation of coniferyl derivatives leads to repression of the phenylpropanoid pathway, whereas reduced accumulation leads to overexpression (Vanholme et al., 2012a, 2012b). Consistent with this hypothesis, both C4H:F5H and cadc cadd exhibited reduction in coniferyl alcohol and share a remarkably similar transcriptional profile including overexpression of lignin biosynthetic genes (Figure 7; Supplemental Figure S10). If similar feedback mechanisms lead to the contrasting transcriptional changes of the shikimate and phenylpropanoid pathway genes in cse-2 and fah1 compared to pal1 pal2, ref3–2, ref3–3, 4cl1, cadc cadd, and C4H:F5H, it is not clear which metabolites may trigger this feedback. In our targeted LC–MS/MS analysis, no common phenylpropanoid was altered uniquely to both cse-2 and fah1 (Supplemental Table S4), but it remains possible that some derivatives of phenylpropanoids not measured here are involved as regulators.

Like C4H:F5H and cadc cadd, ref3 mutants and the med5a/b containing mutants also exhibited high similarity in their DEG profiles (Figure 7), marked by upregulation of genes involved in SA responses. The majority of these upregulated DEGs in ref3 and med5a/b containing mutants are induced by 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid, a synthetic SA analog, treatment in wild-type Arabidopsis leaves (Jin et al., 2018). The activation of SA-responsive genes is consistent with higher SA content in med5a/b ref8 (Bonawitz et al., 2014). Although a larger fraction of SA is thought to be synthesized from isochorismate rather than Phe (Garcion et al., 2008), hyper-accumulation of SA has also been reported in A. annua with RNAi suppressed C4H (Kumar et al., 2016), in tobacco cell culture treated with C4H inhibitors (Schoch et al., 2002), and in transgenic alfalfa lines with RNAi-mediated repression of HCT (Gallego-Giraldo et al., 2011). Interestingly, the genes encoding SA 5-hydroxylase and SA 3-hydroxylase, known to be induced by high SA (Zhang et al., 2013a, 2013, 2017a, 2017b), showed increased expression in these five mutants, suggesting that catabolism of SA is upregulated to maintain SA homeostasis.

The correlation network analysis between metabolite levels and gene expression demonstrated intriguing connections between the accumulation of phenylpropanoids and various biological activities. Interestingly, sinapaldehyde exhibited strong negative correlation with genes involved in cell division, cell cycle, and microtubule-based movement (Figure 8). Arabidopsis C4H:F5H plants that are also defective in CADD deposit sinapaldehyde-derived lignin, are dwarf, and have decreased numbers of tracheary elements in xylem tissue (Anderson et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c). Enhanced accumulation of sinapaldehyde or its derivatives may lead to suppression of genes vital for the cell cycle, such as Cyclin Dependent Kinase B1;2, and a few Cyclin genes (Supplemental Table S6; Vandepoele et al., 2002; Menges et al., 2005; Gutierrez, 2009), causing the defects in cell proliferation observed in cadd C4H:F5H xylem. In our analysis, C4H:F5H had elevated sinapaldehyde content compared to the wild-type control (Supplemental Figure S12), and decreased expression of Cyclin B2;2, Cyclin J18, Cyclin P3;2 (Supplemental Tables S2 and S6; Wang et al., 2004; Gutierrez, 2009). Future exploration is necessary to determine whether and how phenylpropanoids including sinapaldehyde, coniferyl alcohol, and their derivatives act as bioactive signaling molecules to regulate transcriptional reprogramming.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth

Plant lines in this study are all in Arabidopsis (A. thaliana) Col-0background. pal1 (SALK_096474C), pal2 (GABI_692H09-025071), 4cl1 (WiscDsLox473B01), cse-2 (SALK_023077), cadc (SALL_1265_A06), cadd (SALL_776_B06), med5a (SALK_011621), med5b (SALK_037472), are T-DNA insertional mutants that were obtained from Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Ohio State University). ref3–2, ref3–3, ref2, ref8, and fah1 are mutants isolated from ethyl methanesulfonate-generated population with reduced accumulation of sinapoylmalate as reported before (Chapple et al., 1992; Ruegger and Chapple, 2001; Schilmiller et al., 2009). The C4H:F5H F5H over-expresser is a transgenic plant in which the Arabidopsis F5H gene is expressed under the control of the C4H promoter (Meyer et al., 1998). SmF5H contains a Selaginella moellendorffii F5H driven by the Arabidopsis C4H promoter (Weng et al., 2010). Higher order mutants were made by crosses of the single mutants, followed by PCR-based genotyping. Primer sequences for genotyping and expected digestion results are listed in Supplemental Table S7.

Arabidopsis thaliana plants were grown in soil in a growth chamber at 23°C under 100 µE m−2 s−1 with 16-h light/8-h dark cycle. The basal 0.5–2 cm of the inflorescent stems were harvested, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. At noon 28 days after planting, six plants from six randomly positioned pots were gathered for one biological sample for RNA-seq experiment. Four replicate samples were collected for each mutant genotype and eight samples for wild-type. At noon on Day 29, the basal 0.5–2-cm stem fragments of 10 plants from 6 randomly positioned pots were collected as one replicate for soluble metabolites analysis with three replicates for each genotype. Samples were stored at −80°C before extraction for total RNA or soluble metabolites.

RNA-seq

Frozen stem samples were ground in ceramic mortars in liquid nitrogen. About 100 mg ground tissue was used per sample for RNA extraction with the QIAGEN RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA, USA). An on-column DNase treatment was performed to remove DNA from samples. Total RNA samples were submitted to the Purdue Genomics Core Facility (Purdue University) for library construction and subsequent sequencing. PolyA+ RNA libraries were constructed using Illumina’s TruSeq stranded mRNA library prep kit for each sample. Double-end 50-bp sequencing were done on a single chip with an Illumina’s NovaSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The raw transcript reads were mapped using the TAIR10 genome build and the HISAT2 alignment program (Kim et al., 2015a, 2015b). RNA-seq data have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus under GEO Series accession number GSE206323.

Statistical analysis of RNA-seq data

The mapped reads from the RNA-seq experiment were utilized to determine digital gene expression (counts) for every exon using TAIR10 gene model and HTSeq-count program (Anders et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c). Counts were summarized by gene ID. The counts for each gene in all 60 samples were processed with DESeq2 for differential gene expression analysis (R Core Team, 2013; Love et al., 2014). A gene was considered to express at low levels if both its average raw counts were fewer than 30 in at least one genotype and its averaged normalized counts in all 60 samples were less than 5. Removal of genes with low expression resulted in a count table comprising 20,974 expressed genes. Using the result function in DESeq2, expression of genes in every mutant genotype was compared with eight wild-type controls to identify DEGs (FDR < 0.01). Log2FC (mutant to wild-type) values of 5,581 DEGs with at least two-fold changes in at least one mutant were used for hierarchical clustering analysis. Ward.D2 clustering method was applied to generate the heatmap using gplots package (Warnes et al., 2016). GO analysis was done using the DAVID Bioinformatics Resource version 6.8 (Jiao et al., 2012) and 20,974 expressed genes as background, and GO enrichments in BP, MF, and cellular components were captured.

Soluble metabolite analysis on LC/MS–MS

Soluble phenylpropanoids were analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS/MS) using a method developed previously (Jaini et al., 2017). Stem tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen into fine powder then extracted with (10-µL mg−1 fresh weight) 75% aqueous methanol (v/v), for 2 h at 4°C. Samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 4,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was dried under nitrogen gas before being re-dissolved in 60 µL 50% aqueous methanol (v/v). An aliquot of 10 µL samples were injected on LC–MS/MS for quantification of the phenylpropanoid metabolites. Separation was performed on a Zorbax Eclipse C8 column (150 mm 4.6 mm, 5 µm, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with ammonium acetate (pH 5.6) and acetonitrile/H2O/HCOOH (9.8/2/0.2) as mobile phase. Detection was done by an AbSciex QTrap 5,500 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization probe in the negative ion mode. External standards were analyzed with the same method to obtain calibration curves.

Pearson correlation analysis of gene expression and metabolite accumulation

Pearson correlation coefficients r and P-value were calculated in R for pairwise comparison between the normalized counts of all 20,974 expressed genes and the concentrations of 18 measured metabolites in 14 genotypes. Genes with |r| ≥ 0.7 and P < 0.05 with at least one metabolite were selected for hierarchical clustering analysis. Pearson correlation coefficients between 2,987 selected genes and metabolites were used to generate heatmap with Ward.D2 clustering method in gplots package (Warnes et al., 2016). GO analysis of six gene clusters was conducted in DAVID Bioinformatics Resource version 6.8 (Jiao et al., 2012) similarly as described in statistical analysis of RNA-seq data.

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under the following Arabidopsis Genome Initiative accession numbers:_PAL1 (AT2G37040), PAL 2 (AT3G53260), PAL3 (AT5G04230), PAL4 (AT3G10340), C4H (AT2G30490), 4CL1 (AT1G51680), 4CL2 (AT3G21240), 4CL3 (AT1G65060), 4CL4 (AT3G21230), HCT (AT5G48930), C3'H (AT2G40890), C3H (AT1G07890), CSE (AT1G52760), CCoAOMT (AT4G34050), CCR1 (AT1G15950), CCR2 (AT1G80820), F5H (AT4G36220), COMT1 (AT5G54160), CADC (AT3G19450), CADD (AT4G34230), REF1 (AT3G24503), LAC4 (AT2G38080), LAC11 (AT5G03260), LAC17 (AT5G60020), PER64 (AT5G42180), PRX72 (AT5G66390), UGT72B1 (AT1G01070), UGT72B3 (AT1G01020), UGT72E1 (AT3G50740), UGT72E2 (AT5G66690), UGT72E3 (AT5G26310), BGLU45 (AT1G61810), BGLU46 (AT1G61820), Med5A (AT3G23590), Med5B (AT2G48110), REF2 (AT4G13770), REF5 (AT4G31500), KFB01 (AT1G15670), KFB20 (AT1G80440), KFB39 (AT2G44130), and KFB50 (AT3G59940). RNA-seq data can be found in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus under GEO Series accession number GSE206323.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Association of the 50 genes with the highest expression.

Supplemental Figure S2. PCA analysis of expressed genes in RNA-seq data from individual samples of wild type, ref3–2, and ref3–3.

Supplemental Figure S3. PCA analysis of expressed genes in RNA-seq data from individual samples of wild type, med5a/b, med5a/b ref8, and med5a/b ref2.

Supplemental Figure S4. Comparison of gene expression profiles among all the samples.

Supplemental Figure S5. Expression of genes involved in shikimate biosynthesis in the RNA-seq data.

Supplemental Figure S6. Numbers of substantial DEGs in each perturbed plant compared to wild type.

Supplemental Figure S7. Comparison of metabolites and transcripts in wild type, pal1 pal2, fah1, and ref2.

Supplemental Figure S8. Comparison of metabolites and transcripts in wild type, ref3–2, and ref3–3.

Supplemental Figure S9. Comparison of metabolites and transcripts in wild type, 4cl1, and cse-2.

Supplemental Figure S10. Comparison of metabolites and transcripts in wild type, cadc cadd, and C4H:F5H.

Supplemental Figure S11. Comparison of transcripts and metabolites in wild type, med5a/b, med5a/b ref8, and med5a/b ref2.

Supplemental Figure S12. Comparison of metabolites and transcripts in wild type, fah1, C4H:F5H, and ref8 fah1 SmF5H.

Supplemental Table S1. The rank of expression of lignin biosynthetic genes in wild-type samples.

Supplemental Table S2. Differential expression of genes in mutants compared to wild type.

Supplemental Table S3. GO enrichment of gene clusters from the hierarchical clustering results.

Supplemental Table S4. Concentrations of 18 phenylpropanoids from wild type and mutants.

Supplemental Table S5. Common DEGs and enriched GO from subgroups of mutants.

Supplemental Table S6. Pearson correlation analysis between genes expression and metabolite concentrations.

Supplemental Table S7. Primer sequences for genotyping the Arabidopsis mutants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Shaunak Ray for helping with LC/MS–MS analysis of samples.

Funding

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, Genomic Science program, under Award Number DE-SC0008628.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Contributor Information

Peng Wang, Department of Biochemistry, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA.

Longyun Guo, Department of Biochemistry, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA.

John Morgan, Davidson School of Chemical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA; Purdue Center for Plant Biology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA.

Natalia Dudareva, Department of Biochemistry, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA; Purdue Center for Plant Biology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA.

Clint Chapple, Department of Biochemistry, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA; Purdue Center for Plant Biology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA.

P.W., J.M., N.D., and C.C. conceived of the project. P.W. conducted the experiments. P.W. and L.G. analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the analysis and discussion of the results. P.W. and C.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is Clint Chapple (chapple@purdue.edu).

References

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W (2015a) HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31: 166–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NA, Bonawitz ND, Nyffeler K, Chapple C (2015b) Loss of FERULATE 5-HYDROXYLASE leads to Mediator-dependent inhibition of soluble phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 169: 1557–1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NA, Tobimatsu Y, Ciesielski PN, Ximenes E, Ralph J, Donohoe BS, Ladisch M, Chapple C (2015c) Manipulation of guaiacyl and syringyl monomer biosynthesis in an Arabidopsis cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase mutant results in atypical lignin biosynthesis and modified cell wall structure. Plant Cell 27: 2195–2209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldacci-Cresp F, Le Roy J, Huss B, Lion C, Créach A, Spriet C, Duponchel L, Biot C, Baucher M, Hawkins S, et al (2020) UDP-GLYCOSYLTRANSFERASE 72E3 plays a role in lignification of secondary cell walls in Arabidopsis. Int J Mol Sci 21:6094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros J, Escamilla-Trevino L, Song L, Rao X, Serrani-Yarce JC, Palacios MD, Engle N, Choudhury FK, Tschaplinski TJ, Venables BJ, et al (2019) 4-Coumarate 3-hydroxylase in the lignin biosynthesis pathway is a cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase. Nat Commun 10: 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros J, Serrani-Yarce JC, Chen F, Baxter D, Venables BJ, Dixon RA (2016) Role of bifunctional ammonia-lyase in grass cell wall biosynthesis. Nat Plants 2: 16050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthet S, Demont-Caulet N, Pollet B, Bidzinski P, Cezard L, Le Bris P, Borrega N, Herve J, Blondet E, Balzergue S, et al (2011) Disruption of LACCASE4 and 17 results in tissue-specific alterations to lignification of Arabidopsis thaliana stems. Plant Cell 23: 1124–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerjan W, Ralph J, Baucher M (2003) Lignin biosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol 54: 519–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz ND, Chapple C (2010) The genetics of lignin biosynthesis: connecting genotype to phenotype. Annu Rev Genet 44: 337–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz ND, Kim JI, Tobimatsu Y, Ciesielski PN, Anderson NA, Ximenes E, Maeda J, Ralph J, Donohoe BS, Ladisch M, et al (2014) Disruption of Mediator rescues the stunted growth of a lignin-deficient Arabidopsis mutant. Nature 509: 376–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz ND, Soltau WL, Blatchley MR, Powers BL, Hurlock AK, Seals LA, Weng JK, Stout J, Chapple C (2012) REF4 and RFR1, subunits of the transcriptional coregulatory complex mediator, are required for phenylpropanoid homeostasis in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 287: 5434–5445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapelle A, Morreel K, Vanholme R, Le-Bris P, Morin H, Lapierre C, Boerjan W, Jouanin L, Demont-Caulet N (2012) Impact of the absence of stem-specific β-glucosidases on lignin and monolignols. Plant Physiol 160: 1204–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapple CC, Vogt T, Ellis BE, Somerville CR (1992) An Arabidopsis mutant defective in the general phenylpropanoid pathway. Plant Cell 4: 1413–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Dixon RA (2007) Lignin modification improves fermentable sugar yields for biofuel production. Nat Biotechnol 25: 759–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y, Green PJ (2009) mRNA degradation machinery in plants. J Plant Biol 52: 114–124 [Google Scholar]

- Corea OR, Ki C, Cardenas CL, Kim SJ, Brewer SE, Patten AM, Davin LB, Lewis NG (2012) Arogenate dehydratase isoenzymes profoundly and differentially modulate carbon flux into lignins. J Biol Chem 287: 11446–11459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crizel RL, Perin EC, Siebeneichler TJ, Borowski JM, Messias RS, Rombaldi CV, Galli V (2020) Abscisic acid and stress induced by salt: effect on the phenylpropanoid, L-ascorbic acid and abscisic acid metabolism of strawberry fruits. Plant Physiol Biochem 152: 211–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan WL, Dilkes BP, Stout JM, Bonawitz ND, Chapple C (2017) Mediator complex subunits MED2, MED5, MED16, and MED23 genetically interact in the regulation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 29: 3269–3285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Houari I, Boerjan W, Vanholme B (2021a) Behind the scenes: the impact of bioactive phenylpropanoids on the growth phenotypes of Arabidopsis lignin mutants. Front Plant Sci 12: 734070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Houari I, Van Beirs C, Arents HE, Han H, Chanoca A, Opdenacker D, Pollier J, Storme V, Steenackers W, Quareshy M, et al (2021b) Seedling developmental defects upon blocking CINNAMATE-4-HYDROXYLASE are caused by perturbations in auxin transport. New Phytol 230: 2275–2291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder A, Burger J, Gao S, Lewinsohn E, Katzir N, Schaffer AA, Meir A, Davidovich-Rikanati R, Portnoy V, Gal-On A, et al (2015) A Kelch domain-containing F-box coding gene negatively regulates flavonoid accumulation in muskmelon. Plant Physiol 169: 1714–1726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ference CM, Manthey JA, Narciso JA, Jones JB, Baldwin EA (2020) Detection of phenylpropanoids in citrus leaves produced in response to Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Phytopathology 110: 287–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraissinet-Tachet L, Baltz R, Chong J, Kauffmann S, Fritig B, Saindrenan P (1998) Two tobacco genes induced by infection, elicitor and salicylic acid encode glucosyltransferases acting on phenylpropanoids and benzoic acid derivatives, including salicylic acid. FEBS Lett 437: 319–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke R, Humphreys JM, Hemm MR, Denault JW, Ruegger MO, Cusumano JC, Chapple C (2002) The Arabidopsis REF8 gene encodes the 3-hydroxylase of phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant J 30: 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachon CM, Langlois-Meurinne M, Henry Y, Saindrenan P (2005) Transcriptional co-regulation of secondary metabolism enzymes in Arabidopsis: functional and evolutionary implications. Plant Mol Biol 58: 229–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Giraldo L, Escamilla-Trevino L, Jackson LA, Dixon RA (2011) Salicylic acid mediates the reduced growth of lignin down-regulated plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 20814–20819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Giraldo L, Pose S, Pattathil S, Peralta AG, Hahn MG, Ayre BG, Sunuwar J, Hernandez J, Patel M, Shah J, et al (2018) Elicitors and defense gene induction in plants with altered lignin compositions. New Phytol 219: 1235–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcion C, Lohmann A, Lamodiere E, Catinot J, Buchala A, Doermann P, Metraux JP (2008) Characterization and biological function of the ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE2 gene of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 147: 1279–1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng D, Shen X, Xie Y, Yang Y, Bian R, Gao Y, Li P, Sun L, Feng H, Ma F, Guan Q (2020a) Regulation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis by MdMYB88 and MdMYB124 contributes to pathogen and drought resistance in apple. Hortic Res 7: 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng P, Zhang S, Liu J, Zhao C, Wu J, Cao Y, Fu C, Han X, He H, Zhao Q (2020b) MYB20, MYB42, MYB43, and MYB85 regulate phenylalanine and lignin biosynthesis during secondary cell wall formation. Plant Physiol 182: 1272–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Wang P, Jaini R, Dudareva N, Chapple C, Morgan JA (2018) Dynamic modeling of subcellular phenylpropanoid metabolism in Arabidopsis lignifying cells. Metab Eng 49: 36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]