Abstract

The karrikin (KAR) receptor and several related signaling components have been identified by forward genetic screening, but only a few studies have reported on upstream and downstream KAR signaling components and their roles in drought tolerance. Here, we characterized the functions of KAR UPREGULATED F-BOX 1 (KUF1) in drought tolerance using a reverse genetics approach in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). We observed that kuf1 mutant plants were more tolerant to drought stress than wild-type (WT) plants. To clarify the mechanisms by which KUF1 negatively regulates drought tolerance, we performed physiological, transcriptome, and morphological analyses. We found that kuf1 plants limited leaf water loss by reducing stomatal aperture and cuticular permeability. In addition, kuf1 plants showed increased sensitivity of stomatal closure, seed germination, primary root growth, and leaf senescence to abscisic acid (ABA). Genome-wide transcriptome comparisons of kuf1 and WT rosette leaves before and after dehydration showed that the differences in various drought tolerance-related traits were accompanied by differences in the expression of genes associated with stomatal closure (e.g. OPEN STOMATA 1), lipid and fatty acid metabolism (e.g. WAX ESTER SYNTHASE), and ABA responsiveness (e.g. ABA-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT 3). The kuf1 mutant plants had higher root/shoot ratios and root hair densities than WT plants, suggesting that they could absorb more water than WT plants. Together, these results demonstrate that KUF1 negatively regulates drought tolerance by modulating various physiological traits, morphological adjustments, and ABA responses and that the genetic manipulation of KUF1 in crops is a potential means of enhancing their drought tolerance.

A smoke-activated F-box protein negatively regulates drought tolerance by inhibiting stomatal closure, cuticle formation, and root hair development in Arabidopsis.

Introduction

Drought is a substantial environmental problem that limits crop production worldwide. This problem is becoming more serious as a growing global population increases the demand for agricultural water (Farooq et al., 2009; Abdelrahman et al., 2018). Plants adjust their physiological, biochemical, morphological, and molecular responses to survive under water deficiency, but these changes often result in yield reduction (Farooq et al., 2009; Tardieu et al., 2018; Gupta et al., 2020). Changes in endogenous hormone levels, hormone-mediated signal transduction, and metabolite production and mobilization are well-known processes by which plants regulate the balance between growth and drought tolerance (Claeys and Inze, 2013; Bailey-Serres et al., 2019; Fabregas and Fernie, 2019; Gupta et al., 2020). Abscisic acid (ABA) is the best-studied hormone that regulates plant tolerance to drought. ABA promotes stomatal closure, cuticle formation, and the accumulation of several metabolites under water-deficient conditions (Santiago et al., 2009; Kuromori et al., 2018; Gupta et al., 2020). Complex interactions between ABA signaling and other plant hormone signaling pathways also occur in response to drought stress (Nakata et al., 2013; Colebrook et al., 2014; Nir et al., 2014; Riemann et al., 2015; Urano et al., 2017).

Recently, two types of butenolide signaling molecules, strigolactones (SLs) and karrikins (KARs), and several members of their identified signaling components were shown to positively regulate plant drought responses through their effects on the same processes, namely stomatal closure, cuticle formation, and the accumulation of secondary metabolites like anthocyanins (Bu et al., 2014; Ha et al., 2014; Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020). KARs are bioactive signaling molecules originally purified from smoke-water that are known for their role in promoting seed germination (Flematti et al., 2004; Nelson et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 2012). Under different abiotic stress conditions, however, KARs inhibit seed germination (Wang et al., 2018). KARs also promote cotyledon expansion and greening (Nelson et al., 2010), inhibit elongation of light-grown hypocotyls and root skewing (Nelson et al., 2010; Waters et al., 2012; Swarbreck et al., 2019; Villaecija-Aguilar et al., 2019), and promote root hair density and elongation (Villaecija-Aguilar et al., 2019; Carbonnel et al., 2020).

Genetic studies have shown that KAR responses in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) require the genes MORE AXILLARY GROWTH 2 (MAX2) and KARRIKIN INSENSITIVE 2 (KAI2; Nelson et al., 2010; Sun and Ni, 2011; Waters et al., 2012). MAX2 encodes an F-box protein that also participates in SL signaling (Nelson et al., 2010), while KAI2 encodes an α/β hydrolase with high similarity to the SL receptor DWARF14 (D14; Sun and Ni, 2011; Waters et al., 2012). Phenotypic analyses of kai2 mutant plants suggested that KAI2 was a possible KAR receptor (Waters et al., 2012), and this possibility was supported by the direct binding of KAI2 to different types of KARs (Guo et al., 2013). However, more recent observations suggest that KARs require metabolism by plants to activate KAI2 (Waters et al., 2015; Khosla et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). KAI2 is also thought to recognize an endogenous signal, KAI2 ligand (KL), that has not yet been identified (Conn and Nelson, 2016). A negative regulatory component in KAR signaling, SUPPRESSOR OF MAX2 1 (SMAX1), was identified by screening for suppressors of max2 (Stanga et al., 2013). Genetic analyses showed that SMAX1 and its homolog SMAX1 LIKE 2 (SMXL2) suppress KAR responses with partial redundancy (Stanga et al., 2013; Stanga et al., 2016). The current model of KAR signaling proposes that KAR-derived molecules or KL are bound by KAI2, triggering a conformational change in KAI2 that allows for recruitment of MAX2 to form a KAI2-Skp1-Cullin-F-box (SCF)MAX2 complex (Stanga et al., 2016; Khosla et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020). This complex then polyubiquitinates SMAX1 and SMXL2, triggering their degradation by the 26S proteasome (Stanga et al., 2016; Khosla et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020). The degradation of SMAX1 and SMXL2, which putatively function as transcriptional co-repressors, leads to the expression of KAR-responsive genes that activate a series of biological processes summarized above (Stanga et al., 2016; Khosla et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

Several genes, such as D14-LIKE2 (DLK2), B-BOX DOMAIN PROTEIN 20/SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOG 7 (BBX20/STH7), KARRIKIN UPREGULATED F-BOX1 (KUF1), and INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID INDUCIBLE 19 (IAA19), are frequently used as transcriptional markers of KAR/KL signaling because their expression is strongly affected by KAR treatment or the loss of core KAR/KL signaling components (Nelson et al., 2010; Nelson et al., 2011; Waters et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). Some KAR-responsive genes have been implicated in drought tolerance. Among these marker genes, IAA19 has been reported to enhance drought tolerance by promoting the accumulation of glucosinolates (GLSs; Salehin et al., 2019). BBX20/STH7 and its close homolog BBX21 (53% identity) function in part as downstream KAR signaling components that influence anthocyanin accumulation and hypocotyl elongation (Thussagunpanit et al., 2017; Bursch et al., 2021). Although direct evidence for the role of BBX20/STH7 in drought tolerance is still lacking, its positive role in anthocyanin accumulation suggests its possible involvement in enhancing plant drought tolerance (Thussagunpanit et al., 2017; Bursch et al., 2021), owing to the well-known ROS-scavenging activity of anthocyanins (Nakabayashi et al., 2014). Interestingly, two homologs of BBX20/STH7 in Chrysanthemum morifolium, CmBBX19 and CmBBX22, were recently shown to attenuate and enhance C. morifolium drought tolerance, respectively (Liu et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2020).

These observations led us to wonder whether another marker gene of KAR/KL response, KUF1 that is upregulated by KAR treatment (Nelson et al. 2010), may influence drought tolerance. A recent reverse genetic analysis of KUF1 revealed that it attenuates KAR/KL signaling, thus forming a negative feedback loop (Sepulveda et al., 2022). A kuf1 loss-of-function mutant shows constitutive KAR/KL response phenotypes, such as enhanced seedling photomorphogenesis, increased root hair density and elongation, and differential expression of KAR/KL markers. The photomorphogenesis phenotypes of kuf1 seedlings are dependent on MAX2 and KAI2, but they are not due to changes in KAI2 protein abundance. Intriguingly, kuf1 is hypersensitive to KAR1 but not to KAR2. kuf1 seedlings also have normal responses to rac-GR24, a mixture of an SL analog and its enantiomer that preferentially activate D14 and KAI2, respectively. This indicates that KUF1 acts upstream of KAI2-SCFMAX2 to influence perception of some ligands by KAI2. It is currently hypothesized that KUF1 negatively regulates the biosynthesis of endogenous KL and the metabolism of KAR1 into an active ligand for KAI2 (Sepulveda et al., 2022).

Current evidence indicates that KUF1 imposes negative feedback regulation of KAR/KL signaling. However, only a few traits regulated by KAR/KL signaling have been examined, raising the question of whether the role of KUF1 is limited to seedlings. We previously found that KAI2 promotes drought tolerance in Arabidopsis (Li et al., 2017). This led us to investigate the role of KUF1 in the regulation of Arabidopsis drought tolerance under both severe and moderate drought conditions.

Results

kuf1 mutant plants are more drought tolerant than WT plants

To evaluate the contribution of KUF1 to drought tolerance, we first compared the survival rates of kuf1 mutant and WT plants under severe drought stress using the “same tray method.” After drought treatment and re-watering, the survival rate was significantly higher in the kuf1 mutant (by approximately 4.7-fold) than in the WT plants (Figure 1A). To confirm the improved drought tolerance of the kuf1 plants, we also compared the survival rates of kuf1 and two KUF1pro:KUF1 kuf1 complementation lines (KUF1 8-5 and 19-8) under drought conditions. The kuf1 plants showed 5.3- and 2.4-fold increases in survival rate compared with KUF1 8-5 and KUF1 19-8 plants, respectively (Supplemental Figure S1, A and B). Higher drought tolerance in the kuf1 mutant than in the WT was also observed under moderate drought stress using the “gravimetric method” (Harb and Pereira, 2011). As shown in Figure 1, B–D, the relative biomass reduction of kuf1 plants was lower than that of WT, KUF1 8-5, and KUF1 19-8 plants after 14 d of moderate drought. Together, these results demonstrated that the loss of KUF1 function enhances plant tolerance to both severe and moderate drought stresses.

Figure 1.

Drought tolerance of different genotypes under severe and moderate drought stresses. A, Survival rates of WT and kuf1 plants under severe drought were assessed by the “same tray method.” WT and kuf1 plants were grown in pairs for 3 weeks under well-watered conditions (Before drought), and water was then withheld until visible differences in wilting of stem bases were observed between the genotypes (Drought + re-watered). Well-watered control plants were grown at the same time (Well-watered). Survival rates of the tested genotypes after drought and re-watering are shown at right. Data are means ± SDs of three independent experiments (n = 3, 30 plants/genotype/experiment). Asterisks indicate significant differences between the two genotypes (***P < 0.001; Student’s t test). B, Pot weights of WT, kuf1, and two complementation lines under moderate drought (n = 12 biological replicates). C and D, Biomass accumulation (C) and biomass reduction percentages (D) of WT, kuf1, and two complementation lines (KUF1 8-5 and KUF1 19-8) under moderate drought and well-watered conditions were measured by the “gravimetric method.” Data are means ± SDs (n = 15 biological replicates). Different alphabet letters indicate significant differences among the genotypes (P < 0.05; Tukey’s honestly significant difference test).

Leaf water loss and stomatal aperture size are reduced in the kuf1 mutant

Next, we studied the physiological mechanisms associated with the increased drought tolerance of kuf1 mutant plants. We measured leaf surface temperatures as a proxy for estimation of transpiration rates in the kuf1 mutant, the WT, and the two KUF1 complementation lines. The kuf1 mutant always had a higher leaf surface temperature than the WT (Figure 2A) and the complementation lines (Supplemental Figure S1C), suggesting that slower leaf water loss is an important trait that contributes to the drought tolerance phenotype of the kuf1 mutant plants. Guard cells in the leaf epidermis form a stomatal pore that is the main channel for water transpiration (Buckley, 2019). Stomatal aperture was smaller in the leaves of the kuf1 mutant than in those of the WT (Figure 2, B and C), suggesting that KUF1 plays an important role in slowing water loss by modulating stomatal opening.

Figure 2.

Leaf surface temperatures and stomatal apertures of WT and kuf1 plants. A, Leaf surface temperatures of 24-d-old, soil-grown WT and kuf1 plants (24 plants/genotype) grown in well-watered soil. Optical (Left) and thermal imaging (Right) pictures were taken at the same time. B and C, Stomatal aperture sizes of leaves from WT and kuf1 plants under well-watered conditions. Representative guard cell pictures taken within 5 min after the epidermal strips being peeled from leaves and incubated in water (B), and stomatal aperture size data (C) from the abaxial side of rosette leaves of WT and kuf1 plants. Data are means ± SDs (n = 10, average stomatal aperture from each of 10 leaves was determined using 20 randomly selected stomata from each leaf). Asterisks indicate significant differences between the genotypes (**P < 0.01; Student’s t test). D and E, Stomatal closure response of WT and kuf1 plants to ABA. Representative guard cell pictures taken within 2 h after the peeled epidermal strips being incubated in buffer solution containing 0 (H2O) or 30 μM of ABA (D), and stomatal aperture size data (E) from the abaxial side of rosette leaves of WT and kuf1 plants (D). Data are means ± SDs (n = 10, average stomatal aperture from each of 10 leaves was determined using 20 randomly selected stomata from each leaf). Different alphabet letters indicate significant differences between the two genotypes in all treatments (P < 0.05; Tukey’s honestly significant difference test).

ABA responsiveness of the kuf1 mutant

It has been well documented that ABA responsiveness is associated with stomatal closure and drought tolerance (Hsu et al., 2021). We hypothesized that the smaller stomatal aperture observed in kuf1 mutant leaves might be related to enhanced ABA responsiveness. Stomatal closure assays (Figure 2, D and E) revealed faster ABA-induced stomatal closure in the kuf1 mutant than in the WT plants, indicating that the kuf1 mutant was more highly responsive to ABA in terms of stomatal closure. To further investigate the role of KUF1 in ABA responsiveness, we measured seed germination, primary root growth, and chlorophyll levels of kuf1 and WT plants in the presence and absence of ABA. ABA significantly inhibited seed germination and primary root growth to a greater extent in the kuf1 mutant than in the WT, and the effect of ABA increased with increasing concentration as evidenced by seed germination assay (Figure 3, A and B). Furthermore, in growth medium without ABA, the level of chlorophyll was higher in the leaves of kuf1 than of WT (0 μM ABA, Figure 3C; Supplemental Figure S2); however, its content was lower in kuf1 leaves than in WT leaves when 1 μM ABA was present in the growth medium (Figure 3, C and D; Supplemental Figure S2). These data suggested that kuf1 has increased ABA responsiveness, in terms of seed germination, primary root growth, and ABA-induced senescence as well. Together, these results demonstrated that KUF1 negatively regulates ABA responsiveness, and that loss-of-function of KUF1 contributes to a greater ABA responsiveness, and thus drought tolerance in kuf1 plants.

Figure 3.

Seed germination, primary root length, and chlorophyll levels of WT and kuf1 plants in response to ABA. A, Seed germination percentages for WT and kuf1 mutant in the absence (0 μM) and presence (0.5, 1, and 2 μM) of ABA. Data are mean ± SDs (n = 3, 50 seeds/genotype/experiment). Asterisks indicate significant differences between the genotypes (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; Student’s t test). B, Primary root length of 11-d-old WT and kuf1 mutant seedlings grown in media containing 0 and 1 μM ABA for 7 d. Data are means ± SDs (n = 8). C and D, Chlorophyll levels (C) and relative chlorophyll levels (D) of 19-d-old shoots from WT and kuf1 mutant seedlings grown in media containing 0 and 1 μM ABA for 15 d. Data are means ± SDs (n = 5). Different alphabet letters indicate significant differences between the genotypes in all treatments (P < 0.05; Tukey’s honestly significant difference test).

Germination of kuf1 seeds under different abiotic stresses

Originally, KUF1 came into view for its induced expression during seed germination process by exogenous application of KARs that promotes seed germination under normal conditions (Nelson et al. 2009; Nelson et al., 2010). These results suggested that KUF1 might be involved in regulation of seed germination. Interestingly, a later investigation indicated that KARs inhibited seed germination under salt, mannitol-induced osmotic, and high-temperature stress conditions (Wang et al., 2018). We, therefore, asked whether KUF1 plays a role in seed germination under these environmental stresses. Our results showed that the germination rates of kuf1 seeds were significantly lower than those of WT seeds at 40, 80, and 120 mM NaCl concentrations (Supplemental Figure S3A). The same tendency was observed in responses to 40, 80, and 120 mM mannitol concentrations (Supplemental Figure S3B). However, after the imbibed seeds were incubated at 30°C for 0, 2, and 4 d, kuf1 seeds showed higher germination percentage than WT seeds (Supplemental Figure S3C). These results indicate that KUF1 plays different roles in seed germination under different types of abiotic stress.

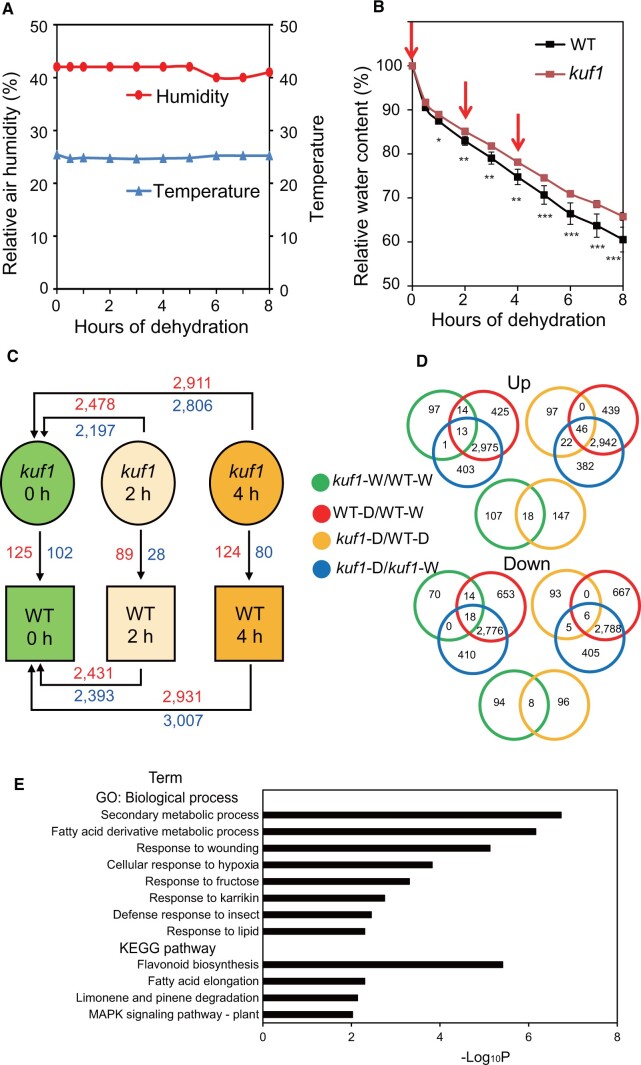

Transcriptome data show that KUF1 regulates plant hormone signaling and fatty acid metabolism

To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms by which KUF1 functions in drought tolerance, we performed transcriptome profiling of rosette leaves from WT and kuf1 mutant plants under normal and dehydrated conditions. Rosette leaves were dissected from soil-grown plants, and their water loss was monitored by measuring relative water content (RWC) over time under laboratory conditions (Figure 4A). Consistent with the drought tolerance phenotype of kuf1 plants, RWC was higher in leaves of the kuf1 mutant than in those of the WT after dehydration (Figure 4B). Rosette leaves of WT and kuf1 mutant plants were harvested for microarray analysis after 0, 2, and 4 h of dehydration (Figure 4B) as shown in Figure 4C. The resulting transcriptome data are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information under accession number GSE167120, and the results of the transcriptome analysis are provided in Supplemental Table S1. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in each comparison were identified based on a transcript-level fold-change of at least 2 and an adjusted false discovery rate (i.e. q-value) < 0.05. The numbers of DEGs in all comparisons are summarized in Figure 4C and Supplemental Table S2. In brief, there were 125, 89, and 124 upregulated genes, and 102, 28, and 80 downregulated genes in the comparisons of kuf1 with WT under well-watered conditions (kuf1-W/WT-W), kuf1 with WT after 2 h of dehydration (kuf1-D2/WT-D2), and kuf1 with WT after 4 h of dehydration (kuf1-D4/WT-D4), respectively (Figure 4C; Supplemental Table S2, m–o and q–s). These DEGs were potentially associated with the roles of KUF1 under well-watered and dehydrated conditions. In comparison between dehydrated and well-watered WT plants, there were more DEGs after 4 h (5,938) than after 2 h (4,824) of dehydration (Figure 4C; Supplemental Table S2, a–b and d–e). Similar trends and numbers of DEGs were observed in the kuf1 mutant plants after 2 (4,675) and 4 h (5,717) of dehydration (Figure 4C; Supplemental Table S2, g–h and j–k).

Figure 4.

Comparative transcriptome analysis of kuf1 and WT plants under well-watered and dehydrated conditions. A, Room temperature and relative air humidity during the dehydration treatment. B, Relative water contents of leaves from 24-d-old WT and kuf1 plants. Data are means ± SDs (n = 4 plants/genotype). Asterisks indicate significant differences between the genotypes (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; Student’s t test). Red arrows indicate sampling time points. C, Summary of differential gene expression data for kuf1 versus WT plants before and after dehydration treatments. Shoot tissues were used in the transcriptome analysis. Numbers indicate the numbers of DEGs for different comparisons; red indicates upregulation, and blue indicates downregulation. D, Venn diagrams showing the common and unique DEGs from different comparisons. kuf1-W/WT-W, kuf1 well-watered 0 h versus WT well-watered 0 h; WT-D/WT-W, WT dehydrated 2 h and/or 4 h versus WT well-watered 0 h; kuf1-D/WT-D, kuf1 dehydrated 2 h versus WT dehydrated 2 h and/or kuf1 dehydrated 4 h versus WT dehydrated 4 h; kuf1-D/kuf1-W, kuf1 dehydrated 2 h and/or 4 h versus kuf1 well-watered 0 h. E, Top 12 enriched terms/pathways of the DEGs identified from kuf1-D/WT-D. The DEGs were classified based on enrichment analysis of GO biological process terms and KEGG pathways. The horizontal axis shows the cumulative hypergeometric P-values of genes mapped to the terms/pathways and represents the abundance of the GO terms and KEGG pathways.

Venn diagram analyses indicated that 27 genes were upregulated and 32 genes were downregulated in kuf1 versus WT plants under well-watered conditions (kuf1-W/WT-W) and also in dehydrated versus well-watered WT plants (WT-D/WT-W; Figure 4D; Supplemental Tables S3b and S4b). These genes were differentially expressed in response to dehydration in the WT but were also differentially expressed in the mutant compared with the WT under well-watered conditions. Their differential expression may therefore have primed the kuf1 mutant to better respond to dehydration. In addition, many genes (46) were upregulated and a few (6) were downregulated in kuf1-D/WT-D and also in the WT-D/WT-W and kuf1-D/kuf1-W comparisons (Figure 4D; Supplemental Tables S3e and S4e). These genes were differentially expressed in both WT and kuf1 plants under dehydration, but the extent of their differential expression under dehydration was greater in kuf1 plants. Some upregulated (18) and downregulated (8) genes also overlapped in both the kuf1-W/WT-W and kuf1-D/WT-D comparisons (Figure 4D; Supplemental Tables S3h and S4h), suggesting that these genes were stably regulated by KUF1 under both normal and dehydrated conditions. We selected 26 genes involved in important drought tolerance mechanisms (e.g. anthocyanin biosynthesis, GLS biosynthesis, and cuticle formation), and synthesis or signaling of several plant hormones (e.g. auxin, ethylene, KARs, etc.) for confirmation of the transcriptome data by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR; Supplemental Figure S4). We generally observed consistent results between the microarray and RT-qPCR data.

To further investigate the roles of KUF1 in drought tolerance, we analyzed DEGs derived from transcriptomic comparisons of the kuf1 mutant with those of the WT under well-watered (Supplemental Table S2, m and q) and dehydrated conditions (Supplemental Table S2, p and t). We performed enrichment analysis using Metascape (http://metascape.org) to classify the DEGs from the kuf1-W/WT-W and kuf1-D/WT-D comparisons into various functional categories and pathways based on Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; Supplemental Table S5, a–b). On the basis of the P-values, the top 12 enriched terms/pathways in the kuf1-W/WT-W DEG set (Supplemental Figure S5) and the top 12 enriched terms/pathways in the kuf1-D/WT-D DEG set (Figure 4E) were selected for further analysis (Figure 4E; Supplemental Figure S5).

In the DEG set from the kuf1-W/WT-W comparison, three sulfate metabolism-related terms/pathways (“S-glycoside biosynthesis process”, “cellular response to sulfur starvation,” and “glucosinolate biosynthesis”) and two hormone-related terms (“response to jasmonic acid” and “response to karrikin”) were enriched (Supplemental Figure S5). In the DEG set from the kuf1-D/WT-D comparison, five drought tolerance-related terms/pathways (“secondary metabolic process,” “fatty acid derivative metabolic process,” “flavonoid biosynthesis,” “response to lipid,” and “fatty acid elongation”) and one hormone-related term (“response to karrikin”) were enriched (Figure 4E). In summary, the “response to karrikin” term appeared in both the kuf1-W/WT-W and kuf1-D/WT-D comparisons. Under normal growth conditions, KUF1 appeared to mainly influence sulfate metabolism and hormone interactions, whereas under drought stress conditions KUF1 appeared to mainly affect drought tolerance through the regulation of fatty acid and lipid metabolism.

KUF1 negatively regulates cuticle formation and positively regulates anthocyanin accumulation

Because the DEGs derived from the kuf1-W/WT-W comparison were enriched in the term “response to karrikin” (Figure 4E), and KAR signaling enhances drought tolerance by promoting cuticle formation (Li et al., 2017), we hypothesized that cuticle formation was enhanced in the kuf1 mutant plants, thereby reducing leaf water loss through a non-stomatal mechanism. To assess this possibility, we measured the cuticular permeability of kuf1 and WT leaves by toluidine blue (TB) staining and chlorophyll leaching assays. Consistent with the differential expression of genes related to cuticle formation that was observed when comparing the leaf transcriptomes of kuf1 and WT plants (Supplemental Figure S4; Supplemental Table S6a), the rosette leaves of the mutant exhibited less TB staining than those of the WT under both low (Figure 5A and B) and high humidity (Supplemental Figure S6) conditions. Likewise, the kuf1 mutant showed significantly less chlorophyll leaching than the WT under low humidity conditions (Figure 5C). We suspected that enhanced cuticle formation might be related to increased wax biosynthesis, as the wax content of the cuticle layer strongly affects its permeability (Yeats and Rose, 2013). Therefore, we used scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to observe epicuticular wax crystals on the surfaces of young stems and siliques. The wax crystal density was markedly higher on the stem and silique surfaces of the kuf1 mutant than on those of the WT after 10 d of drought stress (Figure 5D). Taken together, these results indicate that KUF1 negatively regulates cuticle formation, wax synthesis, and wax crystal formation under drought.

Figure 5.

Cuticle permeability of rosette leaves and epicuticular wax accumulation on stems and siliques of WT and kuf1 plants grown under low humidity (40%–50%). A and B, Rosette leaves of plants grown in soil for 24 d were stained with toluidine blue for 4 h. C, Chlorophyll leaching percentages from rosette leaves of plants grown in soil for 24 d and measured at different time points. Data are means ± SDs (n = 5 plants/genotype). Asterisks indicate significant differences between WT and kuf1 mutant plants (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; Student’s t test). D, Scanning electron micrographs of epicuticular wax on the surface of the stems (2 cm from the top when the stem was > 15 cm) and siliques (4 d after flowering) of 35-d-old, soil-grown plants after water had been withheld for 10 d.

Many anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes were strongly downregulated in the kuf1 mutant relative to the WT under dehydrated conditions (kuf1-D/WT-D), particularly after 4 h of dehydration (Supplemental Figure S4 and Supplemental Table S6b). We, therefore, hypothesized that anthocyanin accumulation might be inhibited in the kuf1 mutant plants. To test this possibility, we measured anthocyanin contents in kuf1 and WT plants under normal and drought conditions. Under well-watered conditions, there were no significant differences in shoot anthocyanin content between kuf1 and WT plants (Supplemental Figure S7, A and B). Under drought conditions, the shoots of both kuf1 and WT plants accumulated higher levels of anthocyanins than those of well-watered conditions, and anthocyanin content was significantly lower in kuf1 plants than in WT plants (Supplemental Figure S7, A and B). To confirm the role of KUF1 in anthocyanin accumulation under drought stress, we investigated the leaf anthocyanin contents of the WT, the kuf1 mutant, and two KUF1 complementation lines under drought conditions. As shown in Supplemental Figure S7, C and D, anthocyanin content of the rosette leaves was lower in the kuf1 mutant than in the WT and the two KUF1 complementation lines under drought. Taken together, these results suggest that KUF1 promotes anthocyanin accumulation under drought conditions.

KUF1 negatively regulates root/shoot ratio and root hair density

The architecture of the root system also strongly influences drought tolerance through its effects on water absorption (Iwata et al., 2013; Uga et al., 2013). The shoots of the kuf1 seedlings were smaller than those of the WT (Figures 5, A and B and 6A; Supplemental Figures S2, S6, A and B), and the root/shoot ratio was higher in the kuf1 mutant than in the WT seedlings (Figure 6B). Because root/shoot ratio is an important morphological parameter for estimating plant drought tolerance (Du et al., 2020), this result suggests that the kuf1 mutant may have a higher ratio of water absorption to water loss capacity than the WT. Detailed investigations showed that kuf1 mutant seedlings had smaller palisade cells than WT in fully expanded cotyledons and the fifth rosette leaf. The hypocotyl cortex cells were also smaller in kuf1 than WT seedlings (Figure 6, C–E). Furthermore, detailed observation of root hair development confirmed that the kuf1 mutant had a higher root hair density and root hair length than the WT (Figure 6, F–H; Sepulveda, 2022). These observations imply that kuf1 plants may have a greater relative capacity for soil water and nutrient uptake. Taken together, these results indicate that KUF1 negatively regulates the root/shoot ratio and root hair development.

Figure 6.

Root/shoot ratios, cell sizes of different tissues, and root hairs of WT and kuf1 plants. A, Representative picture of 14-d-old WT and kuf1 mutant seedlings. B, Root/shoot ratios of 14-d-old WT and kuf1 mutant seedlings. Data are means ± SDs (n = 12 seedlings/genotype). C, The sizes of palisade mesophyll cells from cotyledons of 7-d-old agar-grown WT and kuf1 seedlings. Data are means ± SDs (n = 4 seedlings/genotype, 12 cells/seedling). D, The sizes of cortex cells from hypocotyls of 7-d-old agar-grown WT and kuf1 seedlings. Data are means ± SDs (n = 4 seedlings/genotype, 12 cells/seedling). E, The sizes of palisade mesophyll cells from the fifth leaf of 21-d-old soil-grown WT and kuf1 plants. Data are means ± SDs (n = 4 seedlings/genotype, 12 cells/seedling). F, Representative pictures of 8-d-old root hairs of the WT and kuf1 mutant plants. G, Root hair densities of WT and kuf1 mutant plants. Data are means ± SDs (n = 25 roots/genotype). H, Root hair lengths of WT and kuf1 mutant plants. Data are means ± SDs (n = 10 roots/genotype, 21 root hairs/root). Asterisks indicate significant differences between the genotypes for all statistical analyses in this figure (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; Student’s t test).

Discussion

KAI2-mediated KAR/KL signaling positively regulates plant tolerance to drought stress by promoting stomatal closure, cuticle formation, and anthocyanin accumulation (Li et al., 2020). However, the roles of many genes downstream of KAR/KL signaling in drought tolerance are not yet fully understood. Here, we characterized such a downstream gene, KUF1, which is known to be induced by KAR signaling (Nelson et al., 2010; Nelson et al., 2011; Waters et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). Our aims were to clarify the functions and mechanisms by which KUF1 influences plant drought responses through physiological, transcriptomic, and morphological comparisons of the kuf1 mutant and WT plants under drought stress.

KUF1 negatively regulates drought tolerance by inhibiting cuticle formation, stomatal closure, ABA responsiveness, root/shoot ratios, root hair densities, and root hair length

Under natural growth conditions, crop plants are typically affected by moderate drought stress over long periods of time because of insufficient precipitation or irrigation during the growing season, which decreases plant growth and crop productivity (Farooq et al., 2009; Tardieu et al., 2018; Gupta et al., 2020). The effect of moderate drought stress on biomass is therefore widely used as an indicator of crop drought tolerance, as in the calculation of water use efficiency (Salekdeh et al., 2009). We found that relative biomass reduction was lower in the kuf1 mutant than in the WT plants under drought stress (Figure 1D), indicating that kuf1 plants were more tolerant to moderate drought stress than the WT. We also found that the kuf1 mutant was more tolerant to severe drought than the WT based on the comparison of their survival rates (Figure 1A). Consistently, moderate and severe drought tolerance phenotypes were lost when KUF1 was transferred back into the kuf1 mutant plants (Figure 1, A and D). These results consistently supported the notion that KUF1 functions as a negative regulator of plant drought tolerance.

The prevention of leaf water loss is an important drought avoidance mechanism, and our results suggest that KUF1 enhances leaf water loss (Figures 2A and 4B; Supplemental Figure S1C), leading to enhanced drought tolerance in kuf1 mutant plants (Figure 1, A and D). Leaf water loss can be regulated by both stomatal and non-stomatal mechanisms (Varone et al., 2012). The smaller stomatal apertures and lower cuticular permeability of the kuf1 mutant (Figure 2, B and C, Figure 5, A–C; Supplemental Figure S6) implied that KUF1 contributes to increasing both stomatal and nonstomatal water loss. This result was consistent with the leaf temperature measurements that suggested reduced transpiration rates in kuf1 plants relative to the WT (Figure 2A). At the molecular level, our transcriptome analysis suggested that genes associated with the regulation of stomatal aperture, such as ATP-BINDING CASSETTE G22 (ABCG22; Kuromori et al., 2011; Kuromori et al., 2017), OPEN STOMATA 1 (OST1; Acharya et al., 2013) and PLASMA MEMBRANE INTRINSIC PROTEIN 2;1/2A (PIP2;1/PIP2A; Grondin et al., 2015), were significantly upregulated in leaves of the kuf1 mutant under well-watered and dehydrated conditions (Supplemental Table S6c). ABCG22 was also found to be differentially regulated in max2, kai2, and smax1 smxl2 mutants, confirming its importance as a KAR/KL pathway-regulated gene (Ha et al., 2014; Li et al., 2017; Bursch et al., 2021). These results suggest that KUF1 may negatively regulate the expression of these stomatal closure-related genes, and thereby promoting stomatal opening. In addition, the kuf1 mutant showed upregulation of many cuticle formation-related genes compared with the WT under well-watered and dehydrated conditions. These genes included ECERIFERUM 1 (CER1), CER2, CYTOCHROME P450 86A2 (CYP86A2), WAX ESTER SYNTHASE/DIACYLGLYCEROL ACYLTRANSFERASE 1 (WSD1), MYB DOMAIN PROTEIN 94 (MYB94) and WAX INDUCER1/SHINE1 (WIN1/SHN1; Cui et al., 2016; Supplemental Figure S4; Supplemental Table S6a). These findings collectively suggest that KUF1 inhibits cuticle formation and promotes stomatal opening, thereby increasing leaf water loss.

The plant hormone ABA is widely reported to positively regulate plant drought tolerance (Kuromori et al., 2018; Hsu et al., 2021). Here, we found that kuf1 mutant plants were more sensitive to ABA in terms of stomatal closure, seed germination, primary root growth, and leaf senescence (Figures 2, D and E and 3, A–C; Supplemental Figure S2). These results suggest that the drought tolerance of kuf1 mutant plants is associated with the enhancement of ABA signaling, which also promotes stomatal closure and cuticle formation (Cui et al., 2016; Figures 2, B and C and 5; Supplemental Figure S6). Consistently, several ABA response-related genes, such as ABA-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT 3 (AREB3), HVA22 HOMOLOGUE C (HVA22C), MYB2, OST1, and PIP2A, were significantly upregulated in leaves of the kuf1 mutant relative to those of WT plants under well-watered and/or dehydrated conditions (Supplemental Table S6c). Although we did not measure endogenous ABA levels in kuf1 mutant plants, the expression of CYP707A3 (Supplemental Table S6c), a key gene in ABA catabolism during dehydration stress (Umezawa et al., 2006), was significantly higher in the leaves of drought-tolerant kuf1 than in those of WT under dehydration, suggesting that endogenous ABA levels may have been lower in the kuf1 mutant under those conditions. This possibility remains to be experimentally verified. The opposite results have been observed in drought-susceptible kai2 mutant plants, which exhibit lower expression of CYP707A3 and higher ABA levels than WT plants (Li et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2020). Given the greater ABA sensitivity of the kuf1 mutant relative to WT plants (Figure 3; Supplemental Figure S2), we hypothesize that ABA levels might be decreased. These results might indicate a feedback mechanism, which is associated with the function of KUF1 during drought stress, between ABA levels and ABA responsiveness. Further experiments will be required to investigate the involvement of ABA levels and signal transduction in kuf1 mutant plants under drought stress.

In addition to the physiological mechanisms of leaf water loss, we were also curious about the process of water uptake from the soil through the root system. A root system architecture with favorable root traits, including vigorous root growth and high root hair density, may enhance plant water uptake and drought tolerance (Iwata et al., 2013; Uga et al., 2013). Here, the kuf1 mutant exhibited higher root/shoot ratios, root hair densities, and root hair length than the WT (Figure 6, B, G, and H), which might endorse it with a greater water uptake capacity, thereby contributing to its enhanced drought tolerance (Figure 1, A and D). These findings collectively suggest that KUF1 negatively regulates root/shoot ratios, root hair densities, and root hair length, affecting plant response to drought.

KAI2 and KUF1 often, but not always, have opposing effects on drought tolerance traits and gene expression

It has recently been established that KUF1 attenuates KAR/KL signaling and that kuf1 and kai2 seedlings have opposing phenotypes (Sepulveda, 2022). We found further support for this antagonistic relationship in our analysis of kuf1, which included the examination of genome-wide changes in gene expression. The expression levels of several KAR-signaling marker genes, such as DLK2, DWARF4 (DWF4), BBX20/STH7, and WOX2, were significantly higher in the kuf1 mutant but lower in the kai2 mutant than in the WT under both normal and dehydrated conditions (Supplemental Table S6d). This result was consistent with constitutive activation of KAR/KL signaling in the kuf1 mutant. KUF1 has been proposed to restrict the biosynthesis of the unknown endogenous signal KL (Sepulveda, 2022). If so, our findings here and prior analyses of max2 and kai2 (Ha et al., 2014; Li et al., 2017) suggest a positive role for KL in establishing drought tolerance. F-box proteins typically form part of an SCF-E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase complex that tags specific substrate proteins for ubiquitination and induces 26S proteasome-mediated degradation (Xu et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2019). Screening for the target substrates of KUF1 will be an interesting topic for future research and may aid in the identification of KL.

In comparing the effects of KAI2 and KUF1 on drought tolerance, we found that they play opposite roles in stomatal closure, cuticle formation, and ABA responsiveness (Figure 7A; Supplemental Table S6, a–c; Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2020). However, both KUF1 and KAI2 positively regulate anthocyanin accumulation under drought stress, as indicated by the lower anthocyanin contents and the reduced expression of several anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes in both kuf1 and kai2 mutant plants in comparison with WT (Supplemental Figures S3 and S6; Supplemental Table S6b; Li et al., 2017). One possible interpretation of this observation is that kuf1 mutants are less stressed by water-deprivation than WT, and this somehow overrides KAI2-mediated anthocyanin accumulation. We also found that some GLS biosynthesis-related genes were significantly downregulated in kuf1 versus WT and kai2 versus WT under well-watered and dehydrated conditions (Supplemental Table S6f), suggesting a positive role for both KUF1 and KAI2 in GLS biosynthesis (Figure 7A). Furthermore, many jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthesis-related genes were downregulated in kuf1 versus WT and kai2 versus WT under well-watered and dehydrated conditions (Supplemental Table S6e), suggesting that both KUF1 and KAI2 positively regulate JA biosynthesis as well (Figure 7A). However, many BR biosynthesis-related genes were significantly upregulated in kuf1 versus WT but not in kai2 versus WT under well-watered and dehydrated conditions (Supplemental Table S6e), suggesting that KUF1 negatively regulates BR biosynthesis (Figure 7A). Key GA-biosynthetic genes, such as GA20OX3 and GA3OX1 (Yamaguchi, 2008), were upregulated in kuf1 versus WT but downregulated in kai2 versus WT under dehydration (Supplemental Table S6e; Supplemental Figure S4), suggesting that KUF1 and KAI2 may have opposite roles in the regulation of GA biosynthesis. Measurement of JA, BR, GA, and GLS contents in kuf1 and kai2 mutant plants under normal and drought stress conditions will provide further insight into the influence of KUF1 on these hormones and their metabolic regulation in comparison with KAI2.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the roles of KUF1 and KAI2 and a model of the mechanisms by which KUF1 functions in Arabidopsis drought tolerance. A, KUF1 inhibits stomatal closure and cuticle formation and decreases the ABA response, whereas KAI2 functions in opposite ways, as supported by both phenotypic analyses and gene expression under drought stress. Both KUF1 and KAI2 promote anthocyanin biosynthesis and accumulation under drought stress. Transcriptome data demonstrate that KUF1 may inhibit brassinosteroid (BR) biosynthesis and gibberellin (GA) biosynthesis, and may promote JA and GLS biosyntheses. KAI2 may promote JA, GA, and GLS biosyntheses, as well as KAR signaling. In addition, KAI2 may be activated by an endogenous ligand (KL), and activated KAI2 induces the expression of KUF1 (long black arrow). KUF1 may interact with an SCF-type E3 ubiquitin ligase complex to target an unknown protein(s) (question mark) for polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This unknown protein(s) may participate in KL biosynthesis. Arrows indicate promotion, and blunt bars indicate inhibition. Blue arrows and blunt bars represent the various roles of KUF1, and red arrows and blunt bars represent the various roles of KAI2. Dotted bars and arrows indicate possible regulation. Components of the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex other than Arabidopsis S-phase Kinase-associated protein 1 (ASK1) are not shown. B, KUF1 inhibits ABA responsiveness, stomatal closure, cuticle formation, root/shoot ratios, root hair densities, and root hair development, thereby negatively regulating drought tolerance through increasing shoot water loss and reducing root water absorption. Black blunt bars indicate inhibition by KUF1, and black arrows indicate promotion of processes associated with drought tolerance.

Previous investigations showed that seed germination is a very complex developmental process, which is affected by both endogenous hormone signaling pathways and environmental clues (Gazzarrini and Tsai, 2015). KARs promote germination of seeds of Arabidopsis under normal conditions (Nelson et al., 2009), but inhibit Arabidopsis seed germination in the presence of osmolytes or under high-temperature stresses (Wang et al., 2018). Additionally, even under normal (non-stress) conditions, KARs play negative regulatory role in germination of soybean (Glycine max) seeds under weak light conditions via regulation of ABA levels (Meng et al., 2016). These data indicated that the function of KARs in seed germination is largely dependent on the growth conditions and environmental cues, and demonstrated complex interactions between KAR signaling and growth conditions, which requires further investigations.

In summary, our results show that KUF1 negatively regulates drought tolerance by inhibiting stomatal closure, cuticle formation, and root system development (Figure 7B). In addition, our transcriptome data suggest that KUF1 regulates genes associated with multiple plant hormone pathways and with several primary and secondary metabolic pathways under drought, implying that these pathways and hormones may be related to drought tolerance with the involvement of KUF1. More studies of the underlying mechanisms by which KUF1 regulates drought tolerance will help delineate the signaling network that controls plant drought stress responses and will provide potential approaches for enhancing crop productivity on arid land.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The Columbia-0 accession of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) was used as the wild-type (WT) in all experiments. The kuf1 loss-of-function allele (kuf1-1) and the two rescued KUF1p:KUF1 kuf1-1 transgenic lines are described in (Sepulveda et al., 2022). There is a 200-bp deletion (between +107 and +307 in the coding sequence) in the kuf1 allele (Sepulveda et al., 2022).

Drought tolerance assays

The “same tray method” and “gravimetric method” were used to evaluate the drought tolerance of different genotypes under severe and mild drought stress conditions, respectively. The details of the “same tray method” have been described previously (Nishiyama et al., 2011). In brief, we placed 14-d-old agar-grown seedlings of different genotypes side-by-side in a soil-filled tray. After the seedlings had grown in soil for 1 week, water was withheld. After withholding water for about 2 weeks, the drought-stressed plants were re-watered when a clear difference was observed between the genotypes. To calculate survival rates, 30 plants/genotype/experiment and three (n = 3) experiments were used. We also grew WT and kuf1 plants in parallel under well-watered conditions. The “gravimetric method” was performed as described previously (Harb and Pereira, 2011; Li et al., 2017), and the following equation was used to calculate the percentage of biomass reduction:

To calculate biomass reduction percentages, 15 plants/genotype (n = 15) were used.

Leaf water loss and surface temperature measurements

Relative water content was measured in rosette leaves of kuf1 mutant and WT plants after dehydration. In brief, rosette leaves were cut from 24-d-old, soil-grown kuf1 mutant and WT plants, then placed on the surface of a paper for drying. Fresh weights (FWs) of the leaf samples were measured at different time points after the initiation of dehydration (0.5–8 h). When the dehydration treatment was complete, the leaf samples were immersed in distilled water with shaking for 3 h at room temperature. When the leaves were fully hydrated, leaf turgid weights (TWs) were measured after removing water from the leaf surface using tissue paper. The leaves were then oven-dried at 65°C for 48 h in paper bags, and their dry weights (DWs) were recorded. Relative water contents of the leaf samples (n = 4 plants/genotype) were calculated using the following equation:

Room temperature and relative air humidity were also measured throughout the dehydration treatment. Leaf surface temperatures of rosette leaves from 24-d-old, soil-grown WT and kuf1 plants were estimated using a thermal camera system (FLIR-530; FLIR Optoelectronic Technology, Shanghai Co., Ltd, USA).

Measurement of stomatal aperture

Measurements of stomatal aperture were modified from a previously described method (Osakabe et al., 2013). In brief, 24-d-old fully expanded rosette leaves were harvested from different genotypes, and the abaxial epidermis was peeled from the detached leaves. To measure aperture sizes of kuf1 and WT plants under normal growth conditions, the epidermal strips were quickly placed in water and the pictures of stomata were taken within 5 min after peeling from leaves.

To measure the response of stomatal closure to ABA, the epidermal strips were preincubated in MES-KCl buffer (10 mM MES, 50 mM KCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, pH adjusted to 6.15 with 1 M NaOH) for 2 h in the light (150 μmol m−2 s−1) to promote stomatal opening. Subsequently, the strips were transferred to new MES-KCl buffer alone or with ABA and incubated for an additional 2 h, as indicated in each experiment. Pictures of guard cells were taken using a light microscope equipped with a digital camera at the right moment, and stomatal apertures were measured using ImageJ software package. Stomatal aperture sizes are presented as the means ± SDs of 10 leaves (n = 10, for each leaf the average of 20 stomatal measurements was calculated).

Assays for ABA responsiveness in terms of seed germination, seedling growth inhibition, and leaf senescence

To obtain the seeds for ABA responsiveness assay, we grew WT and kuf1 plants (30 plants/genotype) in the same tray side-by-side, then their seeds were harvested at the same time. To allow after-ripening effect, we stored the seeds in a desiccator (in the presence of silica gel) under room temperature for 2 months. When the germination abilities of WT and kuf1 seeds were similar, these seeds were used for germination assays with and without ABA.

For germination assay, after 2 d of cold treatment at 4°C in the dark, seeds of WT and kuf1 mutant plants were sown on germination medium (GM, 4.43 g Murashige & Skoog Basal Medium with vitamins, 10 g sucrose, and 0.8 g agar were added in 1 L GM, pH adjusted to 7.7 with 1 M KOH) plates supplemented with 0, 0.5, 1, or 2 μM ABA and incubated in a growth chamber at 22 ± 2°C with an 8-h dark/16-h light photoperiod (white light 150 μmol m−2 s−1). Seed germination was defined as the appearance of the radicle and was observed every 12 h after the GM plates had been transferred to the light. To calculate germination percentages, 50 seeds/genotype/experiment and three (n = 3) experiments were used. After 2 weeks of growth on GM plates, whole seedlings were harvested, and their FWs were measured (6 seedlings/reading). Relative FWs were determined using the following equation:

The germination assays in responses to different NaCl and mannitol concentrations, and high temperature were performed following the procedures previously reported in (Wang et al., 2018) and (Toh et al., 2008), respectively.

For the leaf senescence assay, WT and kuf1 mutant seeds were sown on GM plates and grown for 3 d, then transferred to another set of GM plates supplemented with 0 or 1 μM ABA and grown in the growth chamber as previously described (Zhao et al., 2016). When the seedlings had grown for another 11 d, their shoots were harvested, FWs were recorded, and chlorophyll contents (n = 5 plants/genotype) were measured as previously described (Li et al., 2020). Absorbances of the chlorophyll extracts were measured at 663 nm and 645 nm (A663 and A645) using a spectrophotometer (Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer; BioTek Instruments, Inc, USA).

Rosette leaf dehydration treatment and microarray analysis

Rosette leaves from 24-d-old seedlings were subjected to a dehydration treatment under the same environmental conditions described above for leaf water loss measurements, and leaves were harvested after 0, 2, and 4 h of dehydration. Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol Reagent Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). For microarray analysis, RNA samples from 4 biological replicates (n = 4 of WT and kuf1 leaves) were processed using the Arabidopsis Oligo 44K DNA microarray (version 4.0; Agilent, USA). Details of data acquisition and processing were described previously (Ha et al., 2014), and more information on the microarray dataset is available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE167120.

TB staining and chlorophyll leaching assays

A TB staining assay was used to observe cuticle defects in Arabidopsis leaves (Tanaka et al., 2004). In brief, rosette leaves of 24-d-old plants grown in soil under low (40–50%) or high (> 90%) relative air humidity were harvested, placed on ice for 30 min, and submerged in 40 mL TB solution (0.05% w/v) for 2 h. The leaves were gently transferred to water to remove excess TB stain, then cut and placed on dry soft wet paper for photography to prevent leaf water loss. For the chlorophyll leaching assay, detached rosette leaves (n = 5 plants/genotype) were submerged in 40 mL of 80% (v/v) ethanol. Small volumes of leaching solution (100 μL) were sampled every 10 min until 60 min, then sampled again at 24 h. The percentage of extracted chlorophylls was calculated as: [(100 × concentration at a given time point)/(concentration at 24 h)].

Observation of epicuticular wax by SEM

Epicuticular wax was observed using SEM (Quanta 250, FEI, USA). Stem samples were harvested 2 cm from the top of the stem, and silique samples were harvested 4 d after flowering. The tissue samples were coated with platinum using an auto fine coater (Leica RM2235, Germany) before SEM observation.

Measurement of anthocyanin contents

Seeds of the kuf1 mutant and WT were sown directly in the soil. After 21 d of growth in soil trays, water was withheld from the seedlings (n = 30) for 14 d, while another set of seedlings continued to receive water. To confirm the role of KUF1 in anthocyanin accumulation under drought, 14-d-old agar-grown seedlings of WT, kuf1, and two kuf1 complementation lines (KUF1 8-5 and KUF1 19-8) were transferred to soil. The 2-week-old plants (n = 12) were then subjected to drought stress for 21 d. The rosette leaves from all plants were freeze-dried (LGJ-12D freeze drier; Beijing Sihuan Technology, China) for 48 h. After measuring their DWs, leaf anthocyanin contents were measured according to a previously described method (Ito et al., 2015). Absorbance of the anthocyanin extracts was measured at 530 nm (A530) using a microplate reader (Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer; BioTek, USA).

Observations of cells from different plant tissues and root hairs

Palisade mesophyll cells form 7-d-old agar-grown cotyledons (n = 4 seedlings/genotype, 12 cells/seedling), cortex cells from 7-d-old agar-grown hypocotyls (n = 4 seedlings/genotype, 12 cells/seedling) and palisade mesophyll cells from 21-d-old soil-grown fifth true leaves (n = 4 seedlings/genotype, 12 cells/seedling) were photographed by using microscope, and cell sizes were measured by using ImageJ software package. The root hairs of 8-d-old WT and kuf1 were photographed using microscope. Then root hair density (n = 25 roots/genotype) and the root hair lengths (n = 10 roots/genotype, 21 root hairs/root) were measured at 4–5 mm place from root tip by using ImageJ software package.

RT-qPCR analysis

The PrimeScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan) was used for reverse transcription and cDNA synthesis from the same RNA samples used for microarray analysis. RT-qPCR was performed following a previously reported procedure (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001; Le et al., 2012) with UBQ10 as the reference gene. All primers for RT-qPCR analysis are listed in Supplemental Table S7.

Statistical analyses

Statistically significant differences among the data sets (more than three data sets) were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) Sum of Squares Type II (P < 0.05; Tukey’s honestly significant difference test).

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers: KUF1, At1g31350; KAI2, At4g37470. The transcriptome data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information GEO database under accession number GSE167120,

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Drought tolerance and leaf surface temperatures of different genotypes.

Supplemental Figure S2. Leaf senescence of WT and kuf1 plants in response to ABA.

Supplemental Figure S3. Seed germination percentages of WT and kuf1 mutant plants in responses to NaCl, mannitol-induced osmotic, and high-temperature stresses.

Supplemental Figure S4. Confirmation of transcriptome data by qRT-qPCR.

Supplemental Figure S5. Top 12 enriched terms/pathways of the DEGs identified by comparing the transcriptomes of kuf1 and WT plants under well-watered conditions.

Supplemental Figure S6. TB staining of rosette leaves of WT and kuf1 plants grown under high humidity (>90%).

Supplemental Figure S7. Anthocyanin accumulation in rosette leaves of different genotypes under drought stress.

Supplemental Table S1. Gene expression levels and fold-changes in rosette leaves of kuf1 and WT plants under well-watered and dehydrated conditions.

Supplemental Table S2. List of upregulated and downregulated genes (fold-change > 2 and q-value < 0.05) in the different comparisons.

Supplemental Table S3. Venn analysis of the upregulated gene (fold-change > 2 and q-value < 0.05) sets in the different comparisons.

Supplemental Table S4. Venn analysis of the downregulated gene (fold-change > 2 and q-value < 0.05) sets in the different comparisons.

Supplemental Table S5. Enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes from kuf1 versus WT under well-watered and dehydrated conditions using both Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analyses.

Supplemental Table S6. Gene sets related to cuticle formation, anthocyanin metabolism, hormone biosynthesis and signaling, sulfur metabolism, and glucosinolate biosynthesis from different comparisons.

Supplemental Table S7. List of primers used in reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge helpful discussions with Dr. Qingtian Li (University of California, Riverside) of the D.C.N. laboratory.

Funding

W.L. appreciates grant support from the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDA28110100), the National Key R&D Programme of China (#2018YFE0194000, 2018YFD0100304,) from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China and the Key Scientific Research Projects of Institutions of Higher Education in Henan Province (22A180012). Y.M. appreciates grant support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China. (31770300), Henan Overseas Expertise Introduction Centre for Discipline Innovation (CXJD2020004), and the 111 Project#D16014. Support to D.C.N. was provided by National Science Foundation award IOS-1856741. This work was partially supported by Cabinet Office, Government of Japan, Moonshot Research and Development Program for Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (funding agency: Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution, No. JPJ009237).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Contributor Information

Hongtao Tian, Jilin Da’an Agro-ecosystem National Observation Research Station, Changchun Jingyuetan Remote Sensing Experiment Station, Key Laboratory of Mollisols Agroecology, Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changchun 130102, China; State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology, Henan Joint International Laboratory for Crop Multi-Omics Research, School of Life Sciences, Henan University, No. 85 Jinming Road, Kaifeng 475004, China.

Yasuko Watanabe, Bioproductivity Informatics Research Team, RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science, 1-7-22 Suehiro-cho, Tsurumi, Yokohama 230-0045, Japan.

Kien Huu Nguyen, National Key Laboratory for Plant Cell Biotechnology, Agricultural Genetics Institute, Vietnam Academy of Agricultural Science, Pham-Van-Dong Str., Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam.

Cuong Duy Tran, National Key Laboratory for Plant Cell Biotechnology, Agricultural Genetics Institute, Vietnam Academy of Agricultural Science, Pham-Van-Dong Str., Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam.

Mostafa Abdelrahman, Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Aswan University, Aswan 81528, Egypt; Molecular Biotechnology Program, Faculty of Science, Galala University, Suze, New Galala 43511, Egypt.

Xiaohan Liang, State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology, Henan Joint International Laboratory for Crop Multi-Omics Research, School of Life Sciences, Henan University, No. 85 Jinming Road, Kaifeng 475004, China.

Kun Xu, State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology, Henan Joint International Laboratory for Crop Multi-Omics Research, School of Life Sciences, Henan University, No. 85 Jinming Road, Kaifeng 475004, China.

Claudia Sepulveda, Department of Botany & Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, California 92521, USA.

Mohammad Golam Mostofa, Institute of Genomics for Crop Abiotic Stress Tolerance, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409, USA.

Chien Van Ha, Institute of Genomics for Crop Abiotic Stress Tolerance, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409, USA.

David C Nelson, Department of Botany & Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, California 92521, USA.

Keiichi Mochida, Bioproductivity Informatics Research Team, RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science, 1-7-22 Suehiro-cho, Tsurumi, Yokohama 230-0045, Japan; Microalgae Production Control Technology Laboratory, RIKEN Baton Zone Program, RIKEN Cluster for Science, Technology and Innovation Hub, Yokohama, Japan; Kihara Institute for Biological Research, Yokohama City University, Yokohama, Japan; Graduate School of Nanobioscience, Yokohama City University, Yokohama, Japan; School of Information and Data Sciences, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki, Japan.

Chunjie Tian, Jilin Da’an Agro-ecosystem National Observation Research Station, Changchun Jingyuetan Remote Sensing Experiment Station, Key Laboratory of Mollisols Agroecology, Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changchun 130102, China.

Maho Tanaka, Plant Genomic Network Research Team, RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science, Yokohama, Japan; Plant Epigenome Regulation Laboratory, RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research, Wako, Japan.

Motoaki Seki, Plant Genomic Network Research Team, RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science, Yokohama, Japan; Plant Epigenome Regulation Laboratory, RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research, Wako, Japan.

Yuchen Miao, State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology, Henan Joint International Laboratory for Crop Multi-Omics Research, School of Life Sciences, Henan University, No. 85 Jinming Road, Kaifeng 475004, China.

Lam-Son Phan Tran, Institute of Genomics for Crop Abiotic Stress Tolerance, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409, USA.

Weiqiang Li, Jilin Da’an Agro-ecosystem National Observation Research Station, Changchun Jingyuetan Remote Sensing Experiment Station, Key Laboratory of Mollisols Agroecology, Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changchun 130102, China; State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology, Henan Joint International Laboratory for Crop Multi-Omics Research, School of Life Sciences, Henan University, No. 85 Jinming Road, Kaifeng 475004, China.

L.-S.P.T. and W.L. planned and designed the research. W.L., H.T., X.L. K.H.N., C.D.T., Y.W., M.T, M.S., K.X., and C.V.H. performed the experiments. W.L., M.A., C.T., M.G.M., Y.M., and K.M. analyzed the data with the input of L.-S.P.T., C.S., and D.C.N. contributed research materials. L.-S.P.T., D.C.N., and W.L. wrote the paper.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is: Weiqiang Li (liweiqiang@iga.ac.cn)

References

- Abdelrahman M, Jogaiah S, Burritt DJ, Tran LP (2018) Legume genetic resources and transcriptome dynamics under abiotic stress conditions. Plant Cell Environ 41: 1972–1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya BR, Jeon BW, Zhang W, Assmann SM (2013) Open Stomata 1 (OST1) is limiting in abscisic acid responses of Arabidopsis guard cells. New Phytol 200: 1049–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey-Serres J, Parker JE, Ainsworth EA, Oldroyd GED, Schroeder JI (2019) Genetic strategies for improving crop yields. Nature 575: 109–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu Q, Lv T, Shen H, Luong P, Wang J, Wang Z, Huang Z, Xiao L, Engineer C, Kim TH, et al. (2014) Regulation of drought tolerance by the F-box protein MAX2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 164: 424–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TN (2019) How do stomata respond to water status? New Phytol 224: 21–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursch K, Niemann ET, Nelson DC, Johansson H (2021) Karrikins control seedling photomorphogenesis and anthocyanin biosynthesis through a HY5-BBX transcriptional module. Plant J 107:1346–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonnel S, Das D, Varshney K, Kolodziej MC, Villaecija-Aguilar JA, Gutjahr C (2020) The karrikin signaling regulator SMAX1 controls Lotus japonicus root and root hair development by suppressing ethylene biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117: 21757–21765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claeys H, Inze D (2013) The agony of choice: how plants balance growth and survival under water-limiting conditions. Plant Physiol 162: 1768–1779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colebrook EH, Thomas SG, Phillips AL, Hedden P (2014) The role of gibberellin signalling in plant responses to abiotic stress. J Exp Biol 217: 67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn CE, Nelson DC (2016) Evidence that KARRIKIN-INSENSITIVE2 (KAI2) receptors may perceive an unknown signal that is not karrikin or strigolactone. Front Plant Sci 6: 1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui F, Brosche M, Lehtonen MT, Amiryousefi A, Xu E, Punkkinen M, Valkonen JP, Fujii H, Overmyer K (2016) Dissecting abscisic acid signaling pathways involved in cuticle formation. Mol Plant 9: 926–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Zhao Q, Chen L, Yao X, Zhang W, Zhang B, Xie F (2020) Effect of drought stress on sugar metabolism in leaves and roots of soybean seedlings. Plant Physiol Biochem 146: 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabregas N, Fernie AR (2019) The metabolic response to drought. J Exp Bot 70: 1077–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq M, Wahid A, Kobayashi N, Fujita D, Basra SMA (2009) Plant drought stress: effects, mechanisms and management. Sustain Agric 153–188 [Google Scholar]

- Flematti GR, Ghisalberti EL, Dixon KW, Trengove RD (2004) A compound from smoke that promotes seed germination. Science 305: 977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzarrini S, Tsai AY. (2015) Hormone cross-talk during seed germination. Essays Biochem 58: 151–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grondin A, Rodrigues O, Verdoucq L, Merlot S, Leonhardt N, Maurel C (2015) Aquaporins contribute to ABA-Triggered stomatal closure through OST1-mediated phosphorylation. Plant Cell 27: 1945–1954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Zheng Z, La Clair JJ, Chory J, Noel JP (2013) Smoke-derived karrikin perception by the alpha/beta-hydrolase KAI2 from Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 8284–8289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Rico-Medina A, Cano-Delgado AI (2020) The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science 368: 266–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Sinha R, Fernandes JL, Abdelrahman M, Burritt DJ, Tran LP (2020) Phytohormones regulate convergent and divergent responses between individual and combined drought and pathogen infection. Crit Rev Biotechnol 40: 320–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha CV, Leyva-Gonzalez MA, Osakabe Y, Tran UT, Nishiyama R, Watanabe Y, Tanaka M, Seki M, Yamaguchi S, Dong NV, et al. (2014) Positive regulatory role of strigolactone in plant responses to drought and salt stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 851–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harb A, Pereira A (2011) Screening Arabidopsis genotypes for drought stress resistance. Methods Mol Biol 678: 191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PK, Dubeaux G, Takahashi Y, Schroeder JI (2021) Signaling mechanisms in abscisic acid-mediated stomatal closure. Plant J 105: 307–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Nozoye T, Sasaki E, Imai M, Shiwa Y, Shibata-Hatta M, Ishige T, Fukui K, Ito K, Nakanishi H, et al. (2015) Strigolactone regulates anthocyanin accumulation, acid phosphatases production and plant growth under low phosphate condition in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 10: e0119724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata S, Miyazawa Y, Fujii N, Takahashi H (2013) MIZ1-regulated hydrotropism functions in the growth and survival of Arabidopsis thaliana under natural conditions. Ann Bot 112: 103–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla A, Morffy N, Li Q, Faure L, Chang SH, Yao J, Zheng J, Cai ML, Stanga J, Flematti GR, et al. (2020) Structure-function analysis of SMAX1 reveals domains that mediate its darrikin-induced proteolysis and interaction with the receptor KAI2. Plant Cell 32: 2639–2659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromori T, Seo M, Shinozaki K (2018) ABA transport and plant water stress responses. Trends Plant Sci 23: 513–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromori T, Sugimoto E, Ohiraki H, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K (2017) Functional relationship of AtABCG21 and AtABCG22 in stomatal regulation. Sci Rep 7: 12501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromori T, Sugimoto E, Shinozaki K (2011) Arabidopsis mutants of AtABCG22, an ABC transporter gene, increase water transpiration and drought susceptibility. Plant J 67: 885–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le DT, Aldrich DL, Valliyodan B, Watanabe Y, Ha CV, Nishiyama R, Guttikonda SK, Quach TN, Gutierrez-Gonzalez JJ, Tran LS, et al. (2012) Evaluation of candidate reference genes for normalization of quantitative RT-PCR in soybean tissues under various abiotic stress conditions. PLoS One 7: e46487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Nguyen KH, Chu HD, Ha CV, Watanabe Y, Osakabe Y, Leyva-Gonzalez MA, Sato M, Toyooka K, Voges L, et al. (2017) The karrikin receptor KAI2 promotes drought resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet 13: e1007076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Nguyen KH, Chu HD, Watanabe Y, Osakabe Y, Sato M, Toyooka K, Seo M, Tian L, Tian C, et al. (2020) Comparative functional analyses of DWARF14 and KARRIKIN INSENSITIVE 2 in drought adaptation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 103: 111–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Chen H, Ping Q, Zhang Z, Guan Z, Fang W, Chen S, Chen F, Jiang J, Zhang F (2019) The heterologous expression of CmBBX22 delays leaf senescence and improves drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep 38: 15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25: 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Chen F, Shuai H, Luo X, Ding J, Tang S, Xu S, Liu J, Liu W, Du J, et al. (2016) Karrikins delay soybean seed germination by mediating abscisic acid and gibberellin biogenesis under shaded conditions. Sci Rep 6: 22073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakabayashi R, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Urano K, Suzuki M, Yamada Y, Nishizawa T, Matsuda F, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Shinozaki K, et al. (2014) Enhancement of oxidative and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by overaccumulation of antioxidant flavonoids. Plant J 77: 367–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata M, Mitsuda N, Herde M, Koo AJ, Moreno JE, Suzuki K, Howe GA, Ohme-Takagi M (2013) A bHLH-type transcription factor, ABA-INDUCIBLE BHLH-TYPE TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR/JA-ASSOCIATED MYC2-LIKE1, acts as a repressor to negatively regulate jasmonate signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 1641–1656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DC, Flematti GR, Ghisalberti EL, Dixon KW, Smith SM (2012) Regulation of seed germination and seedling growth by chemical signals from burning vegetation. Annu Rev Plant Biol 63: 107–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DC, Flematti GR, Riseborough JA, Ghisalberti EL, Dixon KW, Smith SM (2010) Karrikins enhance light responses during germination and seedling development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 7095–7100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DC, Riseborough JA, Flematti GR, Stevens J, Ghisalberti EL, Dixon KW, Smith SM (2009) Karrikins discovered in smoke trigger Arabidopsis seed germination by a mechanism requiring gibberellic acid synthesis and light. Plant Physiol 149: 863–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DC, Scaffidi A, Dun EA, Waters MT, Flematti GR, Dixon KW, Beveridge CA, Ghisalberti EL, Smith SM (2011) F-box protein MAX2 has dual roles in karrikin and strigolactone signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 8897–8902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nir I, Moshelion M, Weiss D (2014) The Arabidopsis gibberellin methyl transferase 1 suppresses gibberellin activity, reduces whole-plant transpiration and promotes drought tolerance in transgenic tomato. Plant Cell Environ 37: 113–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama R, Watanabe Y, Fujita Y, Le DT, Kojima M, Werner T, Vankova R, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K, Kakimoto T, et al. (2011) Analysis of cytokinin mutants and regulation of cytokinin metabolic genes reveals important regulatory roles of cytokinins in drought, salt and abscisic acid responses, and abscisic acid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 23: 2169–2183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osakabe Y, Arinaga N, Umezawa T, Katsura S, Nagamachi K, Tanaka H, Ohiraki H, Yamada K, Seo SU, Abo M, et al. (2013) Osmotic stress responses and plant growth controlled by potassium transporters in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 609–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann M, Dhakarey R, Hazman M, Miro B, Kohli A, Nick P (2015) Exploring jasmonates in the hormonal network of drought and salinity responses. Front Plant Sci 6: 1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehin M, Li B, Tang M, Katz E, Song L, Ecker JR, Kliebenstein DJ, Estelle M (2019) Auxin-sensitive Aux/IAA proteins mediate drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by regulating glucosinolate levels. Nat Commun 10: 4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salekdeh GH, Reynolds M, Bennett J, Boyer J (2009) Conceptual framework for drought phenotyping during molecular breeding. Trends Plant Sci 14: 488–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago J, Rodrigues A, Saez A, Rubio S, Antoni R, Dupeux F, Park SY, Marquez JA, Cutler SR, Rodriguez PL (2009) Modulation of drought resistance by the abscisic acid receptor PYL5 through inhibition of clade A PP2Cs. Plant J 60: 575–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda C, Guzmán MA, Li Q, Villaécija-Aguilar JA, Martinez S, Kamran M, Khosla A, Liu W, Gendron JM, Gutjahr C, et al. (2022) KARRIKIN UPREGULATED F-BOX 1 (KUF1) imposes negative feedback regulation of karrikin and KAI2 ligand metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 119: e2112820119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanga JP, Morffy N, Nelson DC (2016) Functional redundancy in the control of seedling growth by the karrikin signaling pathway. Planta 243: 1397–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanga JP, Smith SM, Briggs WR, Nelson DC (2013) SUPPRESSOR OF MORE AXILLARY GROWTH2 1 controls seed germination and seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 163: 318–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XD, Ni M (2011) HYPOSENSITIVE TO LIGHT, an alpha/beta fold protein, acts downstream of ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 to regulate seedling de-etiolation. Mol Plant 4: 116–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YK, Flematti GR, Smith SM, Waters MT (2016) Reporter gene-facilitated detection of compounds in Arabidopsis leaf extracts that activate the karrikin signaling pathway. Front Plant Sci 7: 1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarbreck SM, Guerringue Y, Matthus E, Jamieson FJC, Davies JM (2019) Impairment in karrikin but not strigolactone sensing enhances root skewing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 98: 607–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Tanaka H, Machida C, Watanabe M, Machida Y (2004) A new method for rapid visualization of defects in leaf cuticle reveals five intrinsic patterns of surface defects in Arabidopsis. Plant J 37: 139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardieu F, Simonneau T, Muller B (2018) The physiological basis of drought tolerance in crop plants: a scenario-dependent probabilistic approach. Annu Rev Plant Biol 69: 733–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh S, Imamura A, Watanabe A, Nakabayashi K, Okamoto M, Jikumaru Y, Hanada A, Aso Y, Ishiyama K, Tamura N, et al. (2008) High temperature-induced abscisic acid biosynthesis and its role in the inhibition of gibberellin action in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiol 146: 1368–1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]