Abstract

Background.

Optimal hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening strategies for cancer patients have not been established. We compared the performance of selective HCV screening strategies.

Methods.

We surveyed patients presenting for first systemic anticancer therapy during 2013–2014 for HCV risk factors. We estimated the prevalence of positivity for HCV antibody (anti-HCV) and examined factors associated with anti-HCV status using Fisher’s exact test or Student’s t-test. Sensitivity was calculated for screening patients born during 1945–1965, patients with ≥1 other risk factor, or both cohorts (“combined screening”).

Results.

We enrolled 2,122 participants. Median age was 59 years (range, 18–91); 1,138 participants were women. Race/ethnicity distribution was white non-Hispanic, 76% (n=1616); Hispanic, 11% (n=233); black non-Hispanic, 8% (n=160); Asian, 4% (n=78); other, 2% (n=35). Primary cancer distribution was non-liver solid tumor, 78% (n=1,664); hematologic cancer, 20% (n=422); liver cancer, 1% (n=28). Prevalence of anti-HCV was 1.93% (95% CI, 1.39%–2.61%). Over 28% of patients with detectable HCV RNA were unaware of infection. Factors significantly associated with anti-HCV positivity included less than a bachelor’s degree, birth in 1945–1965, chronic liver disease, injection drug use, and blood transfusion or organ transplant before 1992. A total of 1,315 participants (62%), including 39 of 41 with anti-HCV, reported ≥1 risk factor. Sensitivity was 80% (95% CI, 65–91%) for birth-cohort-based, 68% (95% CI, 52–82%) for other-risk-factor-based, and 95% (95% 83–99%) for combined screening.

Conclusion.

Combined screening still missed 5% of patients with anti-HCV. These findings favor universal HCV screening to identify all HCV-infected cancer patients.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, neoplasms, drug therapy, virus activation

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is strongly associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma and may be associated with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic cancer, and head and neck cancer.[1–3] In cancer patients, untreated chronic HCV infection can cause complications, including cirrhosis[4]; persistently elevated alanine aminotransferase levels, which could necessitate delays in or even prevent the use of cancer chemotherapy[5]; viral reactivation, which might require changes in or even discontinuation of cancer therapy[6,7]; and secondary HCV-associated malignancies.[8] Chronic HCV infection can also increase the risk of death in patients with selected hematologic malignancies or solid tumors.[9,10] Therefore, screening for HCV in cancer patients is important, especially since infected patients can be referred for HCV treatment to cure the infection and reduce the risk of adverse outcomes during cancer treatment.[11]

The United States (U.S.) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends selective HCV screening, specifically, 1-time screening for individuals born in 1945–1965 and screening of persons with high risk of exposure to HCV.[12,13] However, patients with a high risk of exposure frequently lack care by a medical provider who can offer HCV testing,[14] making selective screening inferior to universal HCV screening, which has been found to be cost-effective for the general population in the U.S.[15–17] To date, there is no consensus regarding optimal HCV screening strategies in patients with cancer. While universal HCV screening has been recommended for patients with hematologic malignancies and those anticipating hematopoietic cell transplant,[18,19] it remains unclear whether universal HCV screening should be performed in all cancer patients. The aim of this study was to determine the sensitivity of various HCV screening strategies among patients with either solid tumor or hematologic malignancy presenting for first anticancer therapy at a tertiary cancer center in the U.S.

Methods

This study was approved by the MD Anderson Institutional Review Board prior to study initiation, and informed consent was obtained from all study participants. We conducted a cross-sectional study of universal versus selective screening to identify patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or HCV infection prior to chemotherapy, and the study reported herein investigated HCV risk factors and screening. We detailed the patient selection criteria for this study in our previous paper.[20] In brief, we prospectively enrolled cancer patients 18 years of age or older who presented for their first outpatient systemic anticancer therapy appointment at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center during the period from July 2013 through December 2014. Due to the high numbers of eligible patients and challenges of recruiting patients in multiple areas in our cancer center where patients receive anticancer therapy, after the first three months of our study, we initiated a simple random sampling algorithm to identify 80% of the eligible patients over 11 hours each weekday. Study participants completed a survey of hepatitis risk factors from a publicly available CDC hepatitis risk assessment tool (see appendix).[21] We assessed the risk of HCV infection on the basis of national guidelines [12,22]; factors taken into account were birth year and any of the other HCV risk factors: injection drug use, blood transfusion or organ transplant before July 1992, history of chronic liver disease, receipt of clotting factor concentrate before 1987, and a history of HIV infection. History of HCV was not part of the survey. We also asked participants about race and ethnicity, sex, marital status, education level, and primary cancer type. We collapsed the primary cancer types into solid tumors (liver vs. non-liver) and hematologic malignancies. We subdivided liver cancers into HCC and cholangiocarcinoma. In addition, we screened participants for HBV infection using hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc). We defined chronic HBV infection as positive HBsAg and anti-HBc test results and past HBV infection as a negative HBsAg test result with a positive anti-HBc test result.

Participants had hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV) tests performed during the period from 3 months before to 2 months after study enrollment. All participants were tested for anti-HCV using the ABBOTT PRISM HCV assay (Abbott Park, IL). Participants found to have positive anti-HCV test results were informed of their status by the clinical study team and also asked if they had prior knowledge of having a positive anti-HCV test result or HCV infection. To ensure an accurate estimate of the prevalence of HCV infection, we chose not to exclude participants who self-reported having been previously diagnosed with HCV. As part of the standard of care for patients with positive anti-HCV test results, these patients were referred to HCV specialists for confirmation of infection using HCV RNA tests and for consideration of direct-acting antiviral treatment. Reflex HCV RNA testing is not standard practice at our center. We considered patients with detectable HCV RNA to be viremic.

Statistical methods

We estimated the prevalence of positive anti-HCV test results with its exact binomial 95% CI, and we determined the sensitivity and specificity for each of 3 HCV screening strategies: 1) screening only individuals born during 1945–1965 (birth-cohort-based screening), 2) screening only individuals with any of the 5 other HCV risk factors listed above (risk-factor-based screening), and 3) screening individuals born during 1945–1965 or having any of the 5 other HCV risk factors (“combined screening”). In addition, we compared participants with positive and negative anti-HCV test results with respect to individual demographic and clinical factors, using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for participant age at registration. All P values were 2-sided, and P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. Relative risks of anti-HCV positivity and exact 95% CIs are presented to describe the likelihood of anti-HCV positivity by specific cancer type versus all other cancer types. Analyses were conducted using SAS software for Windows, V9.4 (https://www.sas.com/en_us/software/sas9.html; RRID:SCR_008567).

Results

A total of 4,131 patients were eligible. With the implementation of random sampling, we approached 3,534 patients and enrolled 2,206. Of those enrolled, 68 patients did not complete serologic HCV testing, 9 did not complete the HCV risk survey, and 7 withdrew, leaving 2,122 patients in our final cohort. There was no difference in sex or age (p=.48 and 0.57, respectively) between enrolled patients and nonenrollees. The proportions of black and Hispanic patients were lower in our study cohort (7.5% and 10.3%, respectively) than among nonenrollees (12.2% and 14.6%), while the proportions of Asian and non-Hispanic white patients were higher in our study cohort (3.2% and 77.1%, respectively) than among nonenrollees (0.5% and 63%, respectively; overall p<0.001). Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Seventy-eight percent of the participants had a primary non-liver solid tumor, 20% had a hematologic cancer, and 1% had liver cancer. Forty-one (1.93%, 95% CI, 1.39% to 2.61%) had positive anti-HCV test results.

Table 1.

Comparison of participants with positive versus negative anti-HCV test results by demographics, cancer type, and risk factorsa

| Variable | Level | Total | Anti-HCV test result |

P b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n=41) |

Negative (n=2081) |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age at registration, mean (SD), years | 57.9 | (13.3) | 59.3 | (7.7) | 57.9 | (13.3) | .26 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Race/ethnicity | White | 1616 | (76.2) | 30 | (1.9) | 1586 | (98.1) | .08 |

| Black | 160 | (7.5) | 8 | (5.0) | 152 | (95.0) | ||

| Asian | 78 | (3.7) | 0 | (0.0) | 78 | (100.0) | ||

| Other | 35 | (1.6) | 0 | (0.0) | 35 | (100.0) | ||

| Hispanic | 233 | (11.0) | 3 | (1.3) | 230 | (98.7) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Sex | Female | 1138 | (53.6) | 26 | (2.3) | 1112 | (97.7) | .27 |

| Male | 984 | (46.4) | 15 | (1.5) | 969 | (98.5) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Marital status | Single | 175 | (8.3) | 1 | (0.6) | 174 | (99.4) | .13 |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 395 | (18.6) | 12 | (3.0) | 383 | (97.0) | ||

| Married | 1552 | (73.1) | 28 | (1.8) | 1524 | (98.2) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Education level | Less than high school | 116 | (5.5) | 7 | (6.3) | 109 | (94.0) | .0004 |

| High school degree | 331 | (15.6) | 10 | (3.0) | 321 | (97.0) | ||

| Associate’s degree or some college, no college degree | 665 | (31.3) | 16 | (2.4) | 649 | (97.6) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 579 | (27.3) | 3 | (0.5) | 576 | (99.5) | ||

| Graduate degree | 431 | (20.3) | 5 | (1.2) | 426 | (98.8) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Current employment status | Employed | 978 | (46.1) | 18 | (1.8) | 960 | (98.2) | .21 |

| Retired | 649 | (30.6) | 9 | (1.4) | 640 | (98.6) | ||

| Other | 495 | (23.3) | 14 | (2.8) | 481 | (97.2) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Born in U.S. | Yes | 1871 | (88.2) | 41 | (2.2) | 1830 | (97.8) | .012 |

| No | 251 | (11.8) | 0 | (0.0) | 251 | (100.0) | ||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Current primary malignancyc | Non-liver solid | 1664 | (78.4) | 32 | (1.9) | 1632 | (98.1) | .008 |

| Hematologic | 422 | (19.9) | 5 | (1.2) | 417 | (98.8) | ||

| Liver | 28 | (1.3) | 3 | (10.7) | 25 | (89.3) | ||

| Unknown | 7 | (0.3) | 1 | (14.3) | 6 | (85.7) | ||

| No cancer diagnosis | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (100.0) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| HCCd | No | 2091 | (98.9) | 37 | (1.8) | 2054 | (98.2) | .009 |

| Yes | 23 | (1.1) | 3 | (13.0) | 20 | (87.0) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Head & neck cancerd | No | 1917 | (90.7) | 31 | (1.6) | 1886 | (98.4) | .009 |

| Yes | 197 | (9.3) | 9 | (4.6) | 188 | (95.4) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Lung cancerd | No | 1864 | (88.2) | 31 | (1.7) | 1833 | (98.3) | .046 |

| Yes | 250 | (11.8) | 9 | (3.6) | 241 | (96.4) | ||

| Risk factors | ||||||||

| Year of birth 1945–1965 | No | 890 | (41.9) | 8 | (0.9) | 882 | (99.1) | .003 |

| Yes | 1232 | (58.1) | 33 | (2.7) | 1199 | (97.3) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Ever injected drugs | No | 2075 | (97.8) | 21 | (1.0) | 2054 | (99.0) | <.0001 |

| Yes | 47 | (2.2) | 20 | (42.6) | 27 | (57.4) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Blood transfusion or organ transplant before July 1992 | No | 1948 | (94.0) | 35 | (1.8) | 1913 | (98.2) | .034 |

| Yes | 125 | (6.0) | 6 | (4.8) | 119 | (95.2) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Diagnosed with a chronic liver disease | No | 2064 | (98.0) | 22 | (1.1) | 2042 | (98.9) | <.0001 |

| Yes | 42 | (2.0) | 16 | (38.1) | 26 | (61.9) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Received a clotting factor concentrate before 1987 | No | 2051 | (99.4) | 35 | (100.0) | 2016 | (99.4) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 12 | (0.6) | 0 | (0.0) | 12 | (0.6) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Previously diagnosed with HIV or AIDS | No | 2115 | (99.9) | 41 | (1.9) | 2074 | (98.1) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 3 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (100.0) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| HBV test results | Negative | 1987 | (93.6) | 28 | (1.4) | 1959 | (98.6) | < .0001 |

| Positivee | 135 | (6.4) | 13f | (9.6) | 122 | (90.4) | ||

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SD, standard deviation.

Values in table are number of participants (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

P values are from Fisher’s exact test, with the exception of age, which was tested using Student’s t-test, Satterthwaite method for unequal variances.

Liver: HCC (n = 23) or cholangiocarcinoma (n = 5). Lung: primary lung cancers and other cancers affecting the respiratory system.

The 3 primary cancer subcategories (HCC, head & neck cancer, and lung cancer) exclude participants with no cancer (n = 1) or with an unknown primary malignancy (n = 7).

HBV positive: either HBsAg-positive or anti-HBc-positive. Seven participants were HBsAg-positive and anti-HBc-positive, and 128 participants were HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc-positive.

All 13 participants were HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc-positive.

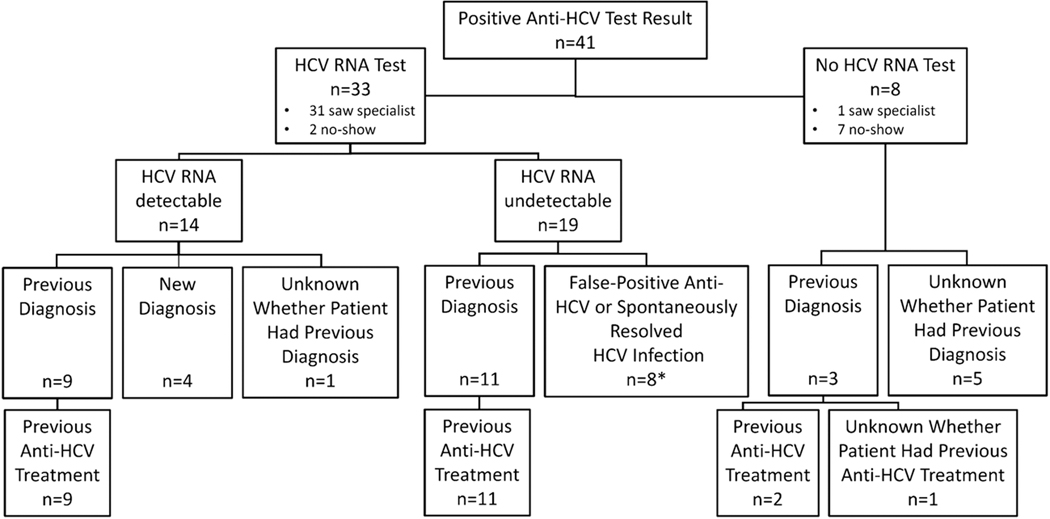

All 41 patients were referred to HCV specialists for further care; 33 (80%) had subsequent HCV RNA testing, while 8 (20%) did not (Figure 1). Among the 33 patients tested, HCV RNA was detectable in 14 (42%) and undetectable in 19 (58%). Of the 14 patients with detectable viremia, 4 were newly diagnosed, and 9 had been previously diagnosed and treated but had not achieved a sustained virologic response to interferon-containing antiviral therapy; for 1 patient, the history related to HCV diagnosis was unknown. Among the 19 patients tested who had undetectable HCV RNA, 11 had a prior history of HCV infection and had completed anti-HCV therapy, and 8 had either a false-positive anti-HCV test result or spontaneous resolution of HCV infection. Of the 8 patients with positive anti-HCV test results who did not undergo subsequent HCV RNA testing, 3 had been previously diagnosed with HCV infection (2 of them had been previously treated, and 1 had unknown treatment history); for the other 5 patients, the history related to HCV diagnosis was unknown. In summary, among 41 patients with positive anti-HCV results, 14 (42%) of the 33 patients tested for HCV RNA were viremic. Of these 14 patients, 4 were newly diagnosed representing 29% of the viremic patients (n=14) and 10% of all anti-HCV-positive patients (n=41).

Figure 1.

Details regarding diagnosis and treatment of HCV infection in 41 patients with positive anti-HCV test results

*7 patients had no previous diagnosis of HCV infection; 1 was previously diagnosed but did not get treatment.

The performance of the 3 HCV screening strategies is summarized in Table 2. A total of 1,232 patients (58%) were born during 1945–1965, and 90% (n = 1103) of these were born in the U.S. All 41 anti-HCV positive patients were born in the U.S. Birth-cohort-based screening had a sensitivity of 80% (95% CI, 65% to 91%), failing to identify 8 of the 41 patients with positive anti-HCV test results (Table 2) or 19.5% of these patients (Figure 2). A total of 207 patients (10%) reported having ≥1 of the 5 other HCV risk factors. Risk-factor-based screening had a sensitivity of 68% (95% CI, 52% to 82%), missing 13 of the 41 patients with positive anti-HCV test results. A total of 1,315 patients (62%) were either born in 1945–1965 or had ≥1 of the 5 other HCV risk factors. Combined screening had a sensitivity of 95% (95% CI, 83% to 99%), failing to identify 2 of the 41 patients with positive anti-HCV test results. The specificity of combined screening was only 39% (95% CI, 37% to 41%). Most (6 of 8, 75%) of the patients with positive anti-HCV test results not identified by birth-cohort-based screening were born before 1945 (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Diagnostic performance of 3 strategies for screening for anti-HCV (n = 2122)

| Performance criterion | Birth-cohort-based screeninga | Risk-factor-based Screeningb | Combined birth-cohort-based and risk-factor-based screening | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meeting criteria, n (%) | 1232 | (58.1) | 207 | (9.8) | 1315 | (62.0) |

| Anti-HCV identified, n (%) | 33 | (80.5) | 28 | (68.3) | 39 | (95.1) |

| Anti-HCV missed, n (%) | 8 | (19.5) | 13 | (31.7) | 2 | (4.9) |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | .80 | (.65 to .91) | .68 | (.52 to .82) | .95 | (.83 to .99) |

| Specificity (95% CI) | .42 | (.40 to .45) | .91 | (.90 to .93) | .39 | (.37 to .41) |

Abbreviation: anti-HCV, hepatitis C virus antibody.

Birth-cohort-based screening was screening of individuals born during 1945–1965.

Risk-factor-based screening was screening of individuals positive for ≥1 of 5 risk factors: ever injected drugs, received a blood transfusion or organ transplant before July 1992, diagnosed with a chronic liver disease, received clotting factor concentrate before 1987, and diagnosed with HIV or AIDS.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the 41 anti-HCV-positive patients by birth-year risk cohort

Birth in 1945–1965, injection drug use, blood transfusion or organ transplant before 1992, and chronic liver disease were individually associated with positive anti-HCV test results (Table 1). Other demographic and clinical variables associated with anti-HCV positivity included having less than a bachelor’s degree, having HCC, and being HBV positive (having chronic or past infection) (Table 1). Patients with HCC, head and neck cancer, or lung cancer had higher rates of anti-HCV positivity (13%, 5%, and 4%, respectively) than the overall rate of anti-HCV positivity in our study (1.93%). The relative risks of anti-HCV positivity for specific cancer types versus all other cancer types were as follows: HCC, 7.37 (95% CI, 2.45 to 22.20); head and neck cancer, 2.83 (95% CI, 1.36 to 5.85); and lung cancer, 2.16 (95% CI, 1.04 to 4.49).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we found that selective screening is suboptimal because not all HCV patients have risk factors or are aware of their infection. Comparing birth-cohort-based, risk-factor-based, and combined screening in patients with cancer presenting for first systemic anticancer therapy, most of the patients with positive anti-HCV test results either were born in 1945–1965 or had another HCV risk factor, but 5% (2/41) of the patients with positive anti-HCV test results would have been left undiagnosed even with combined screening. Of viremic patients with detectable HCV RNA, 29% (4/14) were unaware of their HCV infection. These findings favor universal HCV screening over selective HCV screening in cancer centers, as was recently suggested by the authors of another study in cancer patients in the U.S., in which over 30% of patients with chronic HCV infection either lacked HCV risk factors or were unaware of their infection.[23]

Our findings regarding the deficiencies of selective screening agree with other published studies of HCV screening in the general and cancer patient populations. Studies conducted in emergency departments showed that birth-cohort-based screening would have missed 28% of non-cancer patients with positive anti-HCV test results[24] and that a combined screening strategy with both birth-cohort-based testing and risk-factor-based testing also failed to identify up to 25% of patients with detectable anti-HCV.[25] In a retrospective study from our group that compared selective versus universal HCV screening in 13,718 patients with hematologic malignancies and hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, 42 (30%) of 142 patients newly identified to be anti-HCV positive neither were born in 1945–1965 nor had another known risk factor for HCV infection.[26] In a multicenter prospective cohort study of 3,092 patients with cancer in which risk factors for HCV infection were systematically assessed, 32.4% (23/71) patients with chronic HCV infection neither were born in 1945–1965 nor had another risk factor for HCV infection.[23] The lower proportion of anti-HCV-positive patients not identified by birth cohort or HCV risk factors in our current study than in the other studies may reflect our systematic use of a standardized tool for risk assessment.

Although the results of our systematic combined screening approach appear promising, implementation of screening on the basis of birth cohort or other HCV risk factor may be impractical in busy oncology clinics. Further, selective screening based on birth cohort and other HCV risk factors would require provider familiarity with HCV screening recommendations and patient recall or acknowledgement of past HCV risk behaviors, both of which are potential sources of inaccuracies.[27]

At present, rates of birth-cohort-based and risk-factor-based HCV screening for the general U.S. population appear to be low. This has resulted in only 20% of the 71 million persons infected with HCV infection having received a diagnosis.[14] An analysis of self-reported HCV testing among 21,827 baby boomers in the 2013 and 2015 National Health Interview Surveys showed that the prevalence of HCV screening among individuals born in 1945–1965 was low, 13.8%.[28] In a survey of 4,689 HCV-infected patients who were part of the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study, only 22.3% reported having a risk factor for HCV infection which prompted their initial HCV testing.[27] Of note, the United States Preventive Services Task Force is exploring an update to their HCV screening guidelines and plans to examine the effectiveness of different risk-based or prevalence-based screening strategies on clinical outcomes[29]

Similarly, for patients with cancer, the rates of HCV screening are low, and risk-based screening is not effective. In our previous retrospective study of HCV screening patterns among 16,773 patients with cancer, we found that the HCV screening rate was low overall (13.9%) as well as among persons with known HCV risk factors (42%).[30] The results of the current study favor universal screening for HCV in cancer patients as an effective strategy for identifying all HCV-positive patients.

Expanding the recommendation for 1-time HCV testing to all cancer patients would increase the probability of early diagnosis and treatment of HCV infection, which would improve cancer-related outcomes and also align with the national public health hepatitis vision to identify all people with chronic HCV infection and to ensure they have access to health care and curative HCV treatment[31] as well as the World Health Organization’s Global Hepatitis Elimination Plan to increase the proportion of HCV-infected person who are aware of their diagnosis from 20% to 90% by 2030.[32,14] Universal HCV testing among cancer patients would also align with the 2019 draft recommendation from United States Preventative Task Force for universal HCV testing of all adult persons.[33]

We found that the prevalence of anti-HCV positivity among all cancer patients was 1.9%, similar to the current HCV prevalence among adults in the U.S. general population, 1.7%.[34] We found a higher prevalence of anti-HCV positivity among patients with head and neck cancer (5%) and lung cancer (4%).This higher than expected prevalence of positive anti-HCV test results in patients with head and neck cancer is in agreement with our recently reported finding of an association between chronic HCV infection and head and neck cancer in the U.S. independent of smoking and alcohol use,[2] a finding now validated in other countries in Europe and South America.[35,3] Previous research findings suggest that HCV infection is associated with an increased risk of cancer-specific mortality and cancer progression among patients who have oropharyngeal cancer.[10] Lung cancer is another non-HCC solid tumor with a significantly increased incidence among HCV-infected patients in the general U.S. population,[36] consistent with the high prevalence of HCV among patients with lung cancer in our study. Future longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the etiological role of HCV in these solid tumors and impact on clinical outcomes.

The current study had limitations. First, we did not collect information regarding all HCV risk factors (e.g., we did not collect information about hemodialysis), and thus the results may underestimate the efficacy of risk-factor-based screening. Second, not all patients with positive anti-HCV test results had HCV RNA testing to confirm chronic infection. Future efforts should include reflex testing of HCV RNA in those who test positive for anti-HCV to facilitate HCV screening in clinical practice. Third, risk factors were self-reported, introducing potential recall and reporting biases that could lead to underestimation of the proportion of patients with HCV risk factors. Fourth, because our study was conducted at a single tertiary cancer center, our results may not be generalizable to other cancer patient populations. Finally, we were not able to determine the effect of universal screening on the long-term liver and clinical oncology outcomes. Given the high efficacy and safety of brief (8–12 weeks) direct-acting antiviral therapy, most cancer patients with HCV viremia can be cured of HCV infection prior to or concurrent with anticancer treatment.[37] This would likely improve clinical outcomes by allowing broader options for cancer treatment and eliminate the risk of HCV reactivation.

Although we did not perform a cost-effectiveness analysis, a recent study found that universal screening was cost-effective compared with birth-cohort-based screening when the prevalence of anti-HCV positivity in the general U.S. population was greater than 0.07%,[15] a threshold exceeded in our study, where the overall prevalence of anti-HCV positivity was 1.93%.

In conclusion, many cancer patients with HCV infection are unaware of their infection, and combined screening identified more patients with positive anti-HCV test results than did either birth-cohort-based screening or risk-factor-based screening alone. With combined screening, 62% of patients would need to be screened, and patients with anti-HCV outside the birth cohort and without HCV risk factors would be missed. Risk-factor-based screening is subject to recall and reporting biases and difficult to implement in clinical practice. Thus, our study results favor universal HCV screening to identify all HCV-infected cancer patients. Future research should study the implementation of HCV screening strategies in community-based oncology settings and the impact of anti-HCV therapy and management on patients’ clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge Cynthia Jorgensen at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for assistance with the hepatitis risk survey; Rhodrick Haralson, Sheila Khalili-Ahmadi, and Dianne Stryk for assistance with patient enrollment; Reeni Luke and Sanjivkumar Dave for guidance with institutional databases; Jean Caputo and Calvin Harris for help with survey development; Stephanie Deming for editorial assistance; and Laurissa Gann for assistance with references. We are grateful to the study patients who generously gave their time and effort to this project.

Funding support:

Supported by the National Cancer Institute [K07CA132955 to Hwang, R21CA167202 to Hwang, and P30CA016672 (MD Anderson Cancer Center Clinical Trials Support Resource)]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Authors’ declaration of personal interests:

Jessica P. Hwang reports grants from Gilead and Merck. Harrys A. Torres is or has been the principal investigator for research grants from Gilead Sciences, Inc, and Merck & Company, Inc, with all funds paid to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. He also is or has been a paid scientific advisor for Gilead Sciences, Inc, Merck & Company, Inc, and Dynavax Technologies; the terms of these arrangements are being managed by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies. Anna S. Lok reports receiving research grants paid to the University of Michigan from Assembly Biosciences, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, and TARGET Pharma Solutions and has served on an advisory board of Gilead Sciences. Maria E. Suarez-Almazor reports receiving consultant fees (≤10,000 USD) Pfizer, Inc., AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Agile Therapeutics, and Amag Pharmaceuticals as well as a research grant from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. Erich M. Sturgis reports a grant from Roche Diagnostics.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

All authors accept this version of the article and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Torres HA, Shigle TL, Hammoudi N, Link JT, Samaniego F, Kaseb A, Mallet V (2017) The oncologic burden of hepatitis C virus infection: A clinical perspective. CA Cancer J Clin 67: 411–431. doi: 10.3322/caac.21403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahale P, Sturgis EM, Tweardy DJ, Ariza-Heredia EJ, Torres HA (2016) Association Between Hepatitis C Virus and Head and Neck Cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 108. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rangel JB, Thuler LCS, Pinto J (2018) Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and its impact on the prognosis of head and neck cancer patients. Oral Oncol 87: 138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peffault de Latour R, Levy V, Asselah T, Marcellin P, Scieux C, Ades L, Traineau R, Devergie A, Ribaud P, Esperou H, Gluckman E, Valla D, Socie G (2004) Long-term outcome of hepatitis C infection after bone marrow transplantation. Blood 103: 1618–1624. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres HA, Mahale P, Miller ED, Oo TH, Frenette C, Kaseb AO (2013) Coadministration of telaprevir and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 5: 332–335. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i6.332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahale P, Kontoyiannis DP, Chemaly RF, Jiang Y, Hwang JP, Davila M, Torres HA (2012) Acute exacerbation and reactivation of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in cancer patients. J Hepatol 57: 1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres HA, Hosry J, Mahale P, Economides MP, Jiang Y, Lok AS (2018) Hepatitis C virus reactivation in patients receiving cancer treatment: A prospective observational study. Hepatology 67: 36–47. doi: 10.1002/hep.29344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dandachi D, Hassan M, Kaseb A, Angelidakis G, Torres HA (2018) Hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma as a second primary malignancy: exposing an overlooked presentation of liver cancer. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 5: 81–86. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S164568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramos CA, Saliba RM, de Padua L, Khorshid O, Shpall EJ, Giralt S, Patah PA, Hosing CM, Popat UR, Rondon G, Khouri IF, Nieto YL, Champlin RE, de Lima M (2009) Impact of hepatitis C virus seropositivity on survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Haematologica 94: 249–257. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Economides MP, Amit M, Mahale PS, Hosry JJ, Jiang Y, Bharadwaj U, Sturgis EM, Torres HA (2018) Impact of chronic hepatitis C virus infection on the survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer 124: 960–965. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torres HA, Pundhir P, Mallet V (2019) Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with cancer: impact on clinical trial enrollment, selection of therapy, and prognosis. Gastroenterology. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.271 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Smith BD, Jorgensen C, Zibbell JE, Beckett GA (2012) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initiatives to prevent hepatitis C virus infection: a selective update. Clin Infect Dis 55 Suppl 1: S49–53. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Ward JW (2012) Hepatitis C virus testing of persons born during 1945–1965: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med 157: 817–822. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas DL (2019) Global Elimination of Chronic Hepatitis. N Engl J Med 380: 2041–2050. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1810477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckman MH, Ward JW, Sherman KE (2019) Cost Effectiveness of Universal Screening for Hepatitis C Virus Infection in the Era of Direct-Acting, Pangenotypic Treatment Regimens. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 17: 930–939 e939. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Younossi Z, Blissett D, Blissett R, Henry L, Younossi Y, Beckerman R, Hunt S (2018) In an era of highly effective treatment, hepatitis C screening of the United States general population should be considered. Liver Int 38: 258–265. doi: 10.1111/liv.13519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barocas JA, Tasillo A, Eftekhari Yazdi G, Wang J, Vellozzi C, Hariri S, Isenhour C, Randall L, Ward JW, Mermin J, Salomon JA, Linas BP (2018) Population-level Outcomes and Cost-Effectiveness of Expanding the Recommendation for Age-based Hepatitis C Testing in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 67: 549–556. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torres HA, Chong PP, De Lima M, Friedman MS, Giralt S, Hammond SP, Kiel PJ, Masur H, McDonald GB, Wingard JR, Gambarin-Gelwan M (2015) Hepatitis C Virus Infection among Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Donors and Recipients: American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Task Force Recommendations. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21: 1870–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mallet V, van Bommel F, Doerig C, Pischke S, Hermine O, Locasciulli A, Cordonnier C, Berg T, Moradpour D, Wedemeyer H, Ljungman P, Ecil (2016) Management of viral hepatitis in patients with haematological malignancy and in patients undergoing haemopoietic stem cell transplantation: recommendations of the 5th European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL-5). Lancet Infect Dis 16: 606–617. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00118-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang JP, Lok AS, Fisch MJ, Cantor SB, Barbo A, Lin HY, Foreman JT, Vierling JM, Torres HA, Granwehr BP, Miller E, Eng C, Simon GR, Ahmed S, Ferrajoli A, Romaguera J, Suarez-Almazor ME (2018) Models to Predict Hepatitis B Virus Infection Among Patients With Cancer Undergoing Systemic Anticancer Therapy: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol JCO2017756387. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.6387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Centers for Disease C (2000) Hepatitis C: prevention and risk assessment. Plast Surg Nurs 20: 20–26; quiz 27–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) Hepatitis Risk Assessment (archived). https://web.archive.org/web/20120925161047/https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/riskassessment/index.htm. Accessed August 7, 2012

- 23.Ramsey SD, Unger JM, Baker LH, Little RF, Loomba R, Hwang JP, Chugh R, Konerman MA, Arnold K, Menter AR, Thomas E, Michels RM, Jorgensen CW, Burton GV, Bhadkamkar NA, Hershman DL (2019) Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus, Hepatitis C Virus, and HIV Infection Among Patients With Newly Diagnosed Cancer From Academic and Community Oncology Practices. JAMA oncology. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Lyons MS, Kunnathur VA, Rouster SD, Hart KW, Sperling MI, Fichtenbaum CJ, Sherman KE (2016) Prevalence of Diagnosed and Undiagnosed Hepatitis C in a Midwestern Urban Emergency Department. Clin Infect Dis 62: 1066–1071. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsieh YH, Rothman RE, Laeyendecker OB, Kelen GD, Avornu A, Patel EU, Kim J, Irvin R, Thomas DL, Quinn TC (2016) Evaluation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations for Hepatitis C Virus Testing in an Urban Emergency Department. Clin Infect Dis 62: 1059–1065. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angelidakis G, Hwang JP, Dandachi D, Economides MP, Hosry J, Granwehr BP, Torres HA (2018) Universal screening for hepatitis C: A needed approach in patients with haematologic malignancies. J Viral Hepat 25: 1102–1104. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease C, Prevention (2013) Locations and reasons for initial testing for hepatitis C infection--chronic hepatitis cohort study, United States, 2006–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 62: 645–648 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jemal A, Fedewa SA (2017) Recent Hepatitis C Virus Testing Patterns Among Baby Boomers. Am J Prev Med 53: e31–e33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United States Preventive Services Task Force. Draft Research Plan for Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adolescents and Adults: Screening. (2017). www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-research-plan/hepatitis-c-screening1. Accessed February 8, 2019

- 30.Hwang JP, Suarez-Almazor ME, Torres HA, Palla SL, Huang DS, Fisch MJ, Lok AS (2014) Hepatitis C virus screening in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract 10: e167–174. doi: 10.1200/jop.2013.001215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Services UDoHaH National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan 2017–2020. https://www.hhs.gov/hepatitis/action-plan/national-viral-hepatitis-action-plan-overview/index.html. Accessed May 22, 2019

- 32.World Health Organization Global Hepatitis Report, 2017. http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/. Accessed February 6, 2019

- 33.Draft Recommendation Statement: Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adolescents and Adults: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. August 2019. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-recommendation-statement/hepatitis-c-screening1. Accessed September 13, 2019.

- 34.Hofmeister MG, Rosenthal EM, Barker LK, Rosenberg ES, Barranco MA, Hall EW, Edlin BR, Mermin J, Ward JW, Ryerson AB (2019) Estimating Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in the United States, 2013–2016. Hepatology 69: 1020–1031. doi: 10.1002/hep.30297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu X, Chen Y, Wang Y, Dong X, Wang J, Tang J, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Ji J (2017) Cancer risk in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a population-based study in Sweden. Cancer Med 6: 1135–1140. doi: 10.1002/cam4.988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allison RD, Tong X, Moorman AC, Ly KN, Rupp L, Xu F, Gordon SC, Holmberg SD, Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study I (2015) Increased incidence of cancer and cancer-related mortality among persons with chronic hepatitis C infection, 2006–2010. J Hepatol 63: 822–828. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torres HA, Economides MP, Angelidakis G, Hosry J, Kyvernitakis A, Mahale P, Jiang Y, Miller E, Blechacz B, Naing A, Samaniego F, Kaseb A, Raad II, Granwehr BP (2019) Sofosbuvir-Based Therapy in Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Cancer Patients: A Prospective Observational Study. Am J Gastroenterol 114: 250–257. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0383-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.