Abstract

Background

Mental disorders are recognised as the leading causes of disability worldwide. Despite high rates of incidence, few young people pursue formal help-seeking. Low levels of mental health literacy have been identified as a contributing factor to the notable lack of formal help-seeking by young people. Social media offers a potential means through which to engage and improve young people's mental health literacy. Mental health influencers could be a means through which to do this.

Objective

The objectives of this study were two-fold: (1) to systematically identify the most popular mental health professionals who could be classified as ‘influencers’; and (2) to determine whether their content contributed to mental health literacy.

Methods

The search function of Instagram and TikTok was used to generate a list of accounts owned by mental health professionals with over 100,000 followers. Accounts not in English, in private, with no posts in the last year or with content unrelated to the search terms were excluded. Accounts were assessed for number of followers, country of origin, verified status and whether a disclaimer was included. Using content analysis, the five most recent posts dating back from 15 November 2021 were analysed for purpose and dimensions of mental health literacy as outlined by Jorm (2000) by three separate reviewers.

Results

A total of 28 influencer accounts were identified on TikTok and 22 on Instagram. Majority of the accounts on both TikTok and Instagram originated from the United States (n = 35). A greater number of accounts included disclaimer and crisis support information on Instagram (12/22, 54.55 %) than on TikTok (8/22, 36.36 %). A total of 140 posts were analysed on TikTok and 110 posts on Instagram. When addressing elements of mental health literacy from this sample, 23.57 % (33/140) TikTok posts and 7.27 %. (8/110) posts on Instagram enhanced the ability to recognise specific difficulties.

Conclusions

These platforms and accounts provide a potential means through which to make mental health information more accessible, however, these accounts are not subjected to any credibility checks. Careful consideration should be given to the impact of content created by mental health professionals and its role in supporting help-seeking.

Keywords: Social media, Mental health literacy, Help-seeking, Mental health, Influencers

Highlights

-

•

A total of 28 influencer accounts were identified on TikTok and 22 on Instagram.

-

•

More accounts on Instagram included a disclaimer and crisis support information than on TikTok.

-

•

About two thirds of posts on both TikTok and Instagram could be categorised as having the purpose to ‘educate.’

-

•

Most of the ‘influencers’ were based in North America.

-

•

No posts on either TikTok or Instagram were coded as ‘Promotes knowledge of how to seek mental health information.’

1. Introduction

Currently mental disorders are recognised as one of the leading causes of the burden of disease globally, with no evidence of global reduction in the burden since 1990 (GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022). Research suggests that mental health difficulties are especially prevalent amongst young people, with the onset of most mental disorders taking place before the age of 25 (Kessler et al., 2007; ACAMH Special Interest Group in Youth Mental Health, 2013). Despite high rates of incidence, few receive the necessary treatment or pursue formal help-seeking (Rickwood et al., 2005). Previous research has identified low mental health literacy, stigma and access as significant barriers to help-seeking amongst young people (Gulliver et al., 2012).

It is well-established that young people are avid users of the Internet and social media (Eurostat, 2015; Pew Research Center, 2019; Scott et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2021). On the one hand, social media has been proposed as a risk factor for youth mental health difficulties due to associated risks with the amount of time spent on social media and types of content accessed (Huang, 2017; Dooley et al., 2019). On the other hand, social media has been identified as a resource to aid mental health literacy and help-seeking (Naslund et al., 2020; Power et al., 2020). According to the Pew Research Center's 2021 report on social media use, the majority of young people aged 18–29 year-old, make use of Instagram (76 %), Snapchat (75 %) and TikTok (55 %) (Anderson and Auxier, 2021). Young people use social media for several purposes including entertainment, communication, connecting with peers, education and more recently, to gain health information (Gere et al., 2020; Goodyear and Armour, 2021). It has been reported that it is more likely that young people will pose health queries, including mental health queries, through the Internet than through any other means (Scott et al., 2022). This is especially true in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, with many young people using social media and user-generated content to access the advice and support they are looking for (Pretorius and Coyle, 2021). When understanding young people's help-seeking, a holistic understanding of their online and offline activities must be taken into account. The majority of young people accessing formal mental health services have searched for mental health information online prior to their first consultation (Scott et al., 2022). Research by Pagnotta et al. (Pagnotta et al., 2018) indicates that young people expect their mental health professionals to be aware of the social media relevant at the time and they perceive their therapist's social media competency directly related to their ability to understand their clients. Similarly, research indicates that young people appreciate it when health professionals make recommendations for credible sources of online mental health information to supplement their formal mental health care (Rickwood et al., 2016; Birnbaum et al., 2017).

Given the daily utilization of social media by large portions of the population, it is logical that some mental health professionals are using these platforms to connect with the public. There is a growing number of mental health professionals who use social media to share mental health related content and information that would usually be shared in a therapeutic setting with the broader public. They are known as mental health influencers (Triplett et al., 2022). Influencers are individuals who have a reputation as having expertise in a particular area or topic. Influencers can be classified in several ways, including types of content, number of followers and level of influence (What is an Influencer? - Social Media Influencers Defined [Updated 2022], no date). Influencers are often categorised according to tiers of (1) mega (someone with over a million followers, usually a celebrity, who well known outside of social media, i.e. actors or music artists; their posts are diverse rather that topic specific); (2) macro (usually have over 100,000 followers, has reached fame through the Internet and are usually online experts who have built up a significant following); (3) micro influencers(are normal everyday people who have become known for their specialist niche knowledge, usually have over a 100 but <100,000 followers);and (4) nano influencers (less than a 100, extremely specialised and niche topic usually) (Social Media Influencers: Mega, Macro, Nano or Micro Influencers, no date).

In the health domain, collaborations with influencers have been found to yield very positive results in communicating health messages. In a recent study by Gou, researchers worked with micro-influencers to reduce tobacco use. Results indicated increased reach and engagement with the target audience (Guo et al., 2020). Another study by Yousuf et el. (Yousuf et al., 2020) reported very favourable findings from a national personal hygiene campaign conducted during the beginning stages of the pandemic. Infographics in the newspaper and a video formed part of the campaign. The influencer video was watched over 80,000 times. Whilst collaborations with influencers need to be explored with regard to mental health, social media campaigns on platforms such as YouTube and Facebook are increasingly being used to share and spread messages about mental health and wellbeing (Yap et al., 2019; Latha et al., 2020). Research conducted with social media users confirm that young people identify social media as a potential source of information to pursue positive mental health and to help educate them on mental illness (Naslund et al., 2019; O’Reilly et al., 2019).

Low levels of mental health literacy have been identified as an important contributor to low levels of help-seeking and increase poor mental health outcomes (Bonabi et al., 2016; Gorczynski et al., 2017). Mental health literacy is defined by Jorm (2000) as “knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management or prevention”. There have been studies to investigate the use of different online interventions to improve mental health literacy, but few have looked at the use of social media. A systematic review by Brijnath et al. (Brijnath et al., 2016) highlighted that internet interventions to improve mental health literacy were most successful if they were tailored to specific populations, delivered evidenced-based content, and promoted interactivity. Innovative ways to improve mental health literacy and help-seeking need to be explored. The stigma surrounding mental health negatively impacts help-seeking and it has been found that individuals are now starting to seek help in spaces with which they are already familiar, such as social media (Pagnotta et al., 2018; Gere et al., 2020; Triplett et al., 2022). It offers a means to overcome the traditional barriers to help-seeking such as lack of access (including cost and location), a preference for self-reliance and the avoidance of stigma (Scott et al., 2022).

Despite the growing use of social media, there is limited evidence to suggest how these digital platforms can be used to improve mental health literacy and help-seeking. Mental health professionals who have achieved the status of Mental health Influencer could play an important role in improving mental health literacy and help-seeking. Currently, no research exists on the number of mental health influencers and the nature of their content and how their content relates to mental health literacy and help-seeking. This is an important gap in the literature as this represents an unregulated area of practice for mental health professionals which has the potential to have significant impact on those young people accessing their content. Therefore, this study sought to examine (i) the most popular social media accounts owned by mental health professionals on two platforms – Instagram and TikTok (ii) the role. (if any) their content plays in improving mental health literacy, and finally (iii) what formats and tools do these influencers use to create content. Instagram and TikTok were selected as they were the two most popular platforms amongst young people aged 18 to 25 (Anderson and Auxier, 2021).

2. Method

2.1. Design

A cross-sectional analysis was conducted to identify the most popular mental health professional social media accounts on TikTok and Instagram. The search was conducted on 15 November 2021. Using the search function on Instagram (IG) and TikTok, a list of accounts was generated using the following search terms: psychologist, therapist, psychiatrist, and psychotherapist. Accounts of mental health professionals were identified and included if they met the following inclusion criteria: their profile stated that they were a licensed mental health professional with >100,000 followers. The baseline of 100,000 followers was selected as the cut-off as these accounts would classify as macro influencers, influencers who have a wide reach but usually focus on a specific field. Accounts that were private, not in English or had not posted in the last year were excluded. This search was completed independently by two researchers, CP and DM, and results were manually compared and verified.

2.2. Variables and data collection

The identified accounts were analysed for the number of followers, whether they had a verified status, country of origin, whether the influencer had a presence on both platforms (IG and TikTok), total number of posts (IG), total number of likes (TikTok), whether they included a disclaimer regarding their online services and provided links to their professional website.

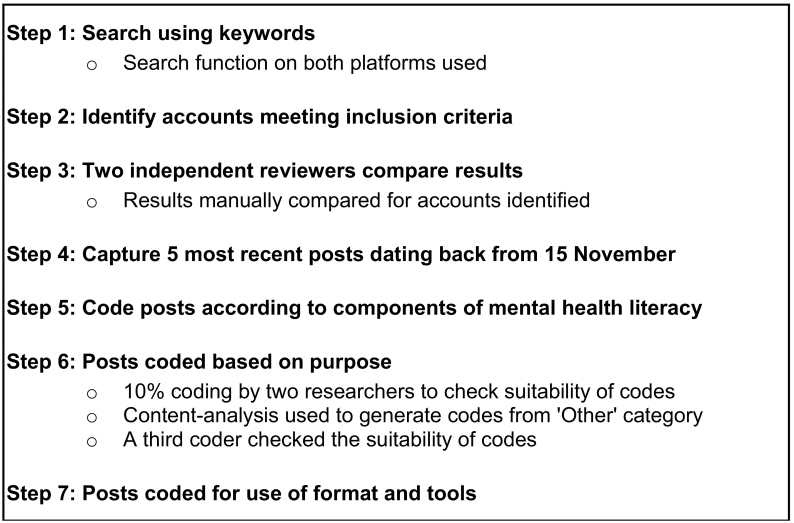

Following a similar methodology to Blakemore et al. (Blakemore et al., 2020), the five most recent posts dating back from 15 November, were then captured, and analysed using deductive content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). Given the high social media post volume, the number of posts (5) for review per account was chosen as representative sampling for the purpose of this study. Fig. 1 outlines the overall sampling and analysis process.

Fig. 1.

The steps followed in the sampling and analysis process.

To explore whether any of the posts promoted mental health literacy, codes were created using the 7 components outlined by Jorm et al. (Jorm, 2000), these include: (1) the ability to recognise specific disorders; (2) knowledge of how to seek mental health information; (3) knowledge of the risk factors of mental illness; (4) knowledge of causes of mental illness; (5) knowledge of self-treatments; (6) knowledge of professional help available; and (7) attitudes that promote recognition and appropriate help-seeking.

To determine the general purpose of the posts, an iterative approach was taken, CP and DM coded 10 % of the posts to check the suitability of the initial codes. During this first round of analysis, the general purpose of the post categories included: education/research (information related to medical facts or a published article), promotion (information about an event, product, or service), inspiration/support (quotes, spiritual or community messages), personal story, celebrity story, humour, news (related to mental health or other news), outreach/awareness (public service announcements, etc.). Using similar methodology from the existing literature (Blakemore et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2021), posts that did not fit the codebook were coded as other. It was determined that the ‘other’ category did not capture the richness of the data and so an inductive content analysis was used to generate a new code book from the ‘other’ posts. DC analysed a selection of posts that were coded as ‘other’ to check new codes. The new codes broke down the ‘education’ category into subcategories which captured the focus of the posts: mental health concern, personal growth, relationships, therapy, self-care, and parenting. The other general-purpose codes included: promotion, engagement, and outreach/awareness. Posts could be coded to have more than one purpose or meet more than one component of mental health literacy.

Inductive content analysis was also used to determine the formats and tools that were used in the posts, some of these were specific to the platform (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). For instance, ‘stitch’ and ‘duets’ is style common to TikTok but not employed on Instagram.

2.3. Analysis

All social media accounts were categorised, and their characteristics were described as means with percentages. The account characteristics were compared across platforms and between influencers and are represented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 below.

Table 1.

TikTok- mental health professionals with >100 k followers. US = United States.

| Account | No of followers | No of likes | Verified | Country | Disclaimer | Personal website | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dr Julie | 3 M | 34 M | Yes | US | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | your.tiktok.therap1st | 2.9 M | 142.1 M | No | US | No | Yes |

| 3 | the.truth.doctor | 1.6 M | 21.9 M | Yes | US | No | Yes |

| 4 | jakegoodmanmd | 1.2 M | 26.9 M | Yes | US | No | Yes |

| 5 | doctorshepard_md | 1.2 M | 22 M | Yes | US | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | micheline.maalouf | 1.1 M | 20.8 M | Yes | US | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Risethriverepeat | 589.1 k | 9.3 M | No | US | No | Yes |

| 8 | psyko_therapy | 585.5 k | 20.3 M | No | US | No | Yes |

| 9 | amoderntherapist | 562.9 k | 9.8 M | No | US | No | Yes |

| 10 | that.anxious.therapist | 534.9 k | 7.2 M | No | US | No | Yes |

| 11 | Drjoekort | 530.2 k | 5.5 M | No | US | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | lindsay.fleminglpc | 520.4 k | 14.2 M | Yes | US | No | Yes |

| 13 | bitesized_therapy | 469.7 k | 12.7 M | No | US | No | No |

| 14 | somymomsatherapist | 450.6 k | 8.5 M | No | US | No | No |

| 15 | dr.marielbuque | 407.6 k | 2 M | No | US | No | Yes |

| 16 | Drkirren | 389.3 k | 1.5 M | No | United Kingdom | No | Yes |

| 17 | Strongtherapy | 335.3 k | 6.7 M | No | US | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | notyouraveragetherapist | 328.6 k | 9.4 M | No | US | No | No |

| 19 | theangrytherapist | 323.2 k | 2.4 M | No | US | No | Yes |

| 20 | actually__alex | 298.8 k | 3.2 M | No | US | No | Yes |

| 21 | Therapyghost | 203.2 k | 4.8 M | No | US | No | Yes |

| 22 | justtherapythings | 189.7 k | 3.5 M | No | US | Yes | Yes |

| 23 | Drkatecalestrieri | 181.6 k | 1.6 M | No | US | No | Yes |

| 24 | Drkristencasey | 137.8 k | 1.8 M | No | US | Yes | Yes |

| 25 | Drkimsage | 128 k | 1.5 M | No | US | No | Yes |

| 26 | theconsciouspsychologist | 111 k | 1 M | No | South Africa | No | Yes |

| 27 | katiemckennatherapist | 108.3 k | 476.4 k | No | Ireland | No | Yes |

| 28 | relationship.therapist | 101.2 k | 1.7 M | No | US | Yes | Yes |

Table 2.

Instagram – mental health professionals with >100 k followers. US = United States.

| Account | No of followers |

No of posts |

Verified | Country | Disclaimer | Personal website | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | the.holistic.psychologist | 4.5 M | 1777 | Yes | US | No | Yes |

| 2 | nedratawwab | 1.2 M | 2235 | Yes | US | No | Yes |

| 3 | millenial.therapist | 1 M | 859 | No | US | No | Yes |

| 4 | myeasytherapy | 651 k | 782 | No | United Kingdom | No | Yes |

| 5 | drjulie | 488 k | 895 | Yes | United Kingdom | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | jakegoodmanmd | 307 k | 228 | Yes | US | No | Yes |

| 7 | holisticallygrace | 288 k | 721 | No | US | No | Yes |

| 8 | theangrytherapist | 271 k | 6015 | Yes | US | No | Yes |

| 9 | micheline.maalouf | 225 k | 493 | Yes | US | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | mombrain.therapist | 221 k | 477 | No | US | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | the.love.therapist | 220 k | 864 | No | US | No | Yes |

| 12 | dr.marielbuque | 201 k | 1967 | Yes | US | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | lovingmeafterwe | 153 k | 2036 | No | US | No | No |

| 14 | alyssamariewellness | 148 k | 934 | Yes | US | No | Yes |

| 15 | heybobbibanks | 137 k | 326 | No | US | Yes | Yes |

| 16 | bodyimage_therapist | 130 k | 705 | Yes | Australia | Yes | Yes |

| 17 | heytiffanyroe | 128 k | 2880 | No | US | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | the.truth.doctor | 125 k | 958 | Yes | US | Yes | Yes |

| 19 | drkatecalestrieri | 123 k | 1160 | Yes | US | Yes | Yes |

| 20 | ablackfemaletherapist | 119 k | 940 | No | US | Yes | Yes |

| 21 | amoderntherapist | 111 k | 380 | No | US | Yes | Yes |

| 22 | jordanpickellcounselling | 100 k | 281 | No | Canada | Yes | Yes |

Table 3.

Accounts with >100 k followers on both TikTok and Instagram.

| Account name | No of followers on TikTok | No of followers on Instagram | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DrJule | 3 million | 488 k |

| 2 | The.truth.doctor | 1.6 million | 125 k |

| 3 | Jakegoodmanmd | 1.2 million | 307 k |

| 4 | Micheline.maalouf | 1.1 million | 225 k |

| 5 | Amoderntherapist | 562.9 k | 111 k |

| 6 | dr.marielbuque | 407.6 k | 201 k |

| 7 | theangrytherapist | 323.2 k | 271 k |

| 8 | drkatecalestrieri | 181.6 k | 123 k |

Table 4.

General purpose of posts content analysis.

| General purpose of post | % of posts on TikTok | TikTok example post | % of posts on IG | IG example post |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education: | 67.86 % (95/140) | 66.43 % (93/110) | ||

| Mental Health Concern | 30.00 % (42/140) | Dr Julie | 12.86 % (18/110) | holisticallygrace |

| Self-care | 3.57 % (5/140) | that.anxious.therapist | 5.00 % (7/110) | Dr Julie |

| Personal growth | 12.14 % (17/140) | risethriverepeat | 31.43 % (44/110) | holisticallygrace |

| Relationships | 7.14 % (10/140) | theconsciouspsychologist | 12.86 % (18/110) | lovingmeafterwe |

| Parenting | 6.43 % (9/140) | therapyghost | 0.00 % (0/110) | |

| Therapy | 8.57 % (12/140) | Relationship.therapist | 4.29 % (6/140) | Dr Julie |

| Promotion | 2.86 % (4/140) | drkatecalestri | 28.18 % (31/110) | The.love.therapist |

| Engagement | 20.00 % (28/140) | justtherapythings | 2.73 % (3/110) | The.truth.doctor |

| Outreach/awareness | 7.86 % (11/140) | drjoekort | 1.82 % (2/110) | amoderntherapist |

Table 5.

Mental health literacy content analysis.

| Elements of MH literacy | % of posts on TikTok | TikTok example post | % of posts on IG | IG example post |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhances the ability to recognise specific disorders (talks about symptoms of specific disorders such as depression) | 23/57 % (33/140) | The.truth.doctor | 7.27 % (8/110) | myeasytherapy |

| Promotes knowledge of how to seek mental health information | 0 % (0/140) | 0.00 % (0/110) | ||

| Promotes knowledge of the risk factors of mental illness | 0.71 % (1/140) | drkimsage | 1.82 % (2/110) | bodyimage_therapist |

| Promotes knowledge of self-treatments or self-help strategies | 13.57 % (19/140) | drkristencasey | 17.27 % (19/110) | heybobbibanks |

| Promotes knowledge of professional help available | 6.43 % (9/140) | strongtherapy | 9.09 % (10/110) | jordanpickellcounselling |

| Promotes attitudes that promote recognition and appropriate help-seeking | 19.29 % (27/140) | Dr.marielbuque | 16.36 % (18/110) | amoderntherapist |

Table 6.

Formats used in posts in (a) TikTok, and (b) Instagram.

| Formats used in post | % of posts on TikTok |

|---|---|

| Text overlay | 52.86 % (74/140) |

| Therapist's own voice | 45 % (63/140) |

| Text-to-speech | 0.71 % (1/140) |

| Use of audio from another source | 17.86 % (25/140) |

| Use of music | 30.71 % (43/140) |

| Role-play | 14.29 % (20/140) |

| Q&A | 2.86 % (4/140) |

| Recorded live | 1.43 % (2/140) |

| Stitch | 5.00 % (7/140) |

| Duet | 5.00 % (7/140) |

| Personal story | 4.29 % (6/140) |

| Humour | 12.86 % (18/140) |

| Formats used in post | % of posts on IG |

|---|---|

| Text image | 66.36 % (73/110) |

| Picture/image | 7.27 % (8/110) |

| Use of music | 6.36 % (7/110) |

| Q&A | 3.64 % (4/110) |

| Video | 19.09 % (21/110) |

| Recorded live | 1.82 % (2/110) |

| Personal story | 0.91 % (1/110) |

| Humour | 2.73 % (3/110) |

3. Results

A total of 28 influencer accounts were identified on TikTok and 22 on Instagram (see Table 1, Table 2). A total of 8 accounts met the inclusion criteria on both TikTok and Instagram (see Table 3), however 32 influencer accounts had a presence on both platforms but met the inclusion criteria on only one of the platforms. The majority of the accounts on both TikTok and Instagram originated from the United States (n = 35), with the United Kingdom (n = 3), Canada (n = 1), Australia (n = −1), Ireland (n = 1), and South Africa (n = 1) also being represented. The median number followers on TikTok were 429,100 (full range 101,200–3,000,000) and 493,000 (full range 100,000–4,500,000) on Instagram. The median number of total likes on TikTok was 6,950,000 (full range 476,400–142,100,000) and the median number of posts on Instagram was 879.5 (full range 879.5–6015).

On TikTok, 6 (21.43 %) of the accounts had verified status versus 11 (50 %) accounts on Instagram. The mental professional's registration categories included: psychiatrist (n = 2), psychologist (n = 11), psychotherapist (n = 7), counsellor (n = 9), social worker (n = 6), and therapist (n = 6).

A greater number of accounts included disclaimer and crisis support information on Instagram (12/22 (54.55 %)) than on TikTok (8/28 (28.57 %)). Many of the influencers used the ‘stories’ function on Instagram to save the disclaimer to the top of their profiles and some influencers had a standard narrative that was included at the end of each post that highlighted both the disclaimer and crisis support information. However, most profiles have links that directed followers to a LinkedIn account, which often included links to a personal website and additional resources. These resources at times included charities or causes that the influencer supports, workbooks or factsheets, and other supports. It also included links to products and therapy practices.

A total of 140 posts were analysed on TikTok and 110 posts on Instagram A similar proportion of posts on both TikTok (67.86 % (95/140)) and on Instagram (66.43 % (93/110)) were categorised as having the purpose to educate (see Table 4). A greater proportion of posts on Instagram 28.18 % (31/110)) were for promotion purposes than on TikTok (2.86 % (4/140)). Within the ‘Education’ category, 30 % of TikTok posts focused on specific ‘mental health concerns’, whilst 31.43 % of posts of Instagram posts focused on ‘Personal Growth’ related content.

The results of the analysis for mental health literacy can be found in Table 5. When addressing elements of mental health literacy from this sample, a greater proportion of TikTok posts (23.57 % (33/140)) enhanced the ability to recognise specific disorders than on Instagram (7.27 % (8/110)). Instagram also had a slightly lower proportion of posts (16.36 % (18/110)) that promoted attitudes that promote recognition and appropriate help-seeking than TikTok (19.29 % (27/140)). No posts on either TikTok or Instagram were coded as ‘Promotes knowledge of how to seek mental health information.’

A diverse use of formats and tools were used across both platforms to create posts and content, see Table 6. A variety of audio formats were used in many TikTok posts, including the therapist's own voice, music, text-to-speech, and audio from another source such as posts. Instagram posts often utilised text images (66.36 % (73/110)) and static pictures, whilst some posts also made use of various audio formats and video (19.09 % (21/110)).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study with Instagram and TikTok to describe the nature of social media accounts held by mental health professionals who have achieved influencer status. Instagram and TikTok were selected for analysis as they were the two most popular platforms amongst young people aged 18 to 25 (Anderson and Auxier, 2021). This study highlights several points for consideration.

Many of the accounts originated from the United States and their professional registration categories were specific to the United States. To those from outside of the U.S., it may not be clear how the U.S. systems work and what these registration categories mean in terms of training and specialty. Although the number of international followers from each account can be difficult to specifically identify, the United States has a significant population, and it could be assumed that many of the influencers based in the United States would have a mostly North American following. Equally, many young people may not be familiar with different registration categories from within their own countries and what these mean in terms of access, service provision and approaches.

A greater number of influencers on Instagram included a disclaimer and crisis support information than on TikTok. The ‘bio' section on both TikTok and Instagram have character limits which may make it difficult to include in this section. Instagram provides the ‘stories' functionality at the top of a profile to include disclaimers and crisis support information. Triplett (Triplett et al., 2022) poses an important question, if Mental Health influencers do not make the limits of social media clear, for instance not including a disclaimer, what are the assumptions that the public are making about their availability, their ability to help and the boundaries of their interactions. Previous research has found that many young people seek help when in crisis and are looking for available options 24/7, and it is thus important to consider what assumptions are being made in relation the support they can receive from mental health influencers (Pretorius et al., 2019b).

Credibility has been identified as an important concern when young people are seeking help online for mental health concerns (Pretorius et al., 2019b). This study found that a limited number of the influencers on both TikTok and Instagram have verified status on these platforms. However, this did not appear to impact the number of followers when comparing influencers who had verified status and those who did not. There is likely an inferred element of credibility as the public assumes these individuals are in a position of authority because of their assumed education and licensed credentials (Triplett et al., 2022). Followers often feel connected to influencers and often form a ‘parasocial’ relationship with them and many commercial brands often work with influencers to improve the authenticity and trustworthiness of a brand, making them a powerful and valuable resource (Guo et al., 2020). For this reason, the role of an influencer in mental health must be carefully balanced within the ethics of the profession, best-practice for mental health professionals as influencers needs to be established. Anthony (Anthony, 2015) argues that whilst mental health professionals need to embrace the technological advancements taking place, they also need specialist training to be able to provide appropriate telehealth services, with critical thinking being an important component to that training.

Two of the authors of this study have specialist training in Psychology to a doctoral level and after reflection, noted that they were able to code posts as ‘Education’ because of their knowledge of the field. It was not clear that this would have been the case if other coders outside of the field had been coding the posts. Psychoeducation is an important part of the therapeutic process and this is the element that is being capitalised on in social media settings and in particular by these mental health professionals. Information that is usually shared on a one-to-one basis in a therapeutic setting is now being repackaged for mass consumption on social media and is simplified to appeal to a broader audience without the context of the therapeutic space. Whilst references to research were not often used in the selection of videos sampled for analysis, acknowledging the evidence-base should be an important consideration for mental health influencers. It is well established when seeking help-seeking online references to literature are important in establishing credibility (Pretorius et al., 2019a). In turn, mental health literacy could be positively impacted by providing references to scientific evidence.

Based on the analysis in this paper, we do not seek to draw concrete conclusion on the motivation of mental health professionals in maintaining Instagram or TikTok accounts. It is likely to include a combination of factors. We believe that for many social media is an extension of their core practice as provides of mental health support. Career and business development factors may also play a role. What is clear is that audience engagement is critical and was prioritised. Many of the posts in this sample appear to be for purposes of entertainment, as part of a strategy to keep or gain followers, to improve engagement, and potentially to encourage use of their ‘products’ or services. Whilst the objective of these accounts might not be to improve or facilitate mental health literacy or help-seeking, it is likely that these accounts do normalise talking about mental health, make mental health professionals more accessible and perhaps break down any myths of who or what a mental health professional are, which may in turn promote help-seeking (Alonzo and Popescu, 2021). The ‘sharing’ function promoted by various social media platform provides a means to spread mental health messaging which may further impact stigma reduction and normalises talking about mental health.

The notable number of followers and likes on both platforms, and the reach and potential impact offered, make them promising options through which to engage the public, and young people in particular. Several of the accounts identified in this study have over a million followers. These platforms and accounts provide a means through which to make mental health information more accessible, potentially supporting greater mental health literacy and overcoming some of the traditional barriers to engaging with mental health issues, including access, stigma, and a preference for self-reliance. Given the link between mental health literacy and help-seeking they also have the potential to act as a catalyst to further help-seeking. Both platforms included posts that support recognition of difficulties and promote help-seeking (Table 5). The degree to which these posts actually result in greater help-seeking is not something our analysis can address, but is an important question for future research.

While this question will require empirical investigation and carefully designed studies, one possible avenue to future research will be to analyse data already available, in the form of users' responses to posts on TikTok and Instagram. Analysis of these comments may provide valuable insight on the impact, positive and negative, that influencers have on their audience, why people find these accounts engaging, and whether the impact and conversations are distinct on different platforms. There was some overlap in the influencers analysed across Instagram and TikTok - with eight influencers meeting the inclusion criteria for analysis on both platforms. A further 32 influencer accounts had a presence on both platforms but met the inclusion criteria on only one of the platforms. This suggests the discourse across both platforms has many similarities. However, we are reluctant to draw conclusions on this, as it would be speculative given the analysis in the paper. In future is would be interesting to contrast the approaches taken on both platforms, considering the degree to which influencers present on both platforms tailor content on a platform specific basis. This analysis could provide insight on distinct approaches to achieving engagement on each platform.

5. Conclusion

Mental Health organisations and national health providers can learn from the mental health professionals such as those in this study in the ways and means in which they engage with followers and present psychoeducational content. Whilst corporate companies have already explored partnerships with influencers to improve their credibility and image, this needs to be explored in more depth. In disseminating valuable mental health information, mental health influencers can play an important role in improving help-seeking, however, could benefit from having access to guidelines that outline the help-seeking needs of those who are accessing their content.

6. Strengths and limitations

There are several limitations that need to be considered. The frequency of posts differed across influencers which increased the likelihood of including posts that may be informed by other global events happening simultaneously. It was beyond the scope of this study to analysis the entire collection of posts of each influencer, therefore only a selection of all posts was sampled. However future studies should look at analysing a greater portion of posts for each influencer, to identify overall themes and patterns. The totals provided for followers on are not presented as exact numbers on platforms and are likely rounded up.

Finally, while this paper has sought to understand the current landscape on TikTok and Instagram, it has not sought to provide explicit recommendations or guidance to mental health professionals using these platforms. Detailed recommendations in this regard represent an important objective for future research. One clear priority, from our perspective, is the provision of detailed guidance on how to balance evidence-based information with approaches that achieve audience engagement.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. This project was partly funded by Science Foundation Ireland (12/RC/2289_P2).

Contributor Information

Claudette Pretorius, Email: Claudette.pretorius@ucdconnect.ie.

Darragh McCashin, Email: darragh.mccashin@dcu.ie.

David Coyle, Email: d.coyle@ucd.ie.

References

- ACAMH Special Interest Group in Youth Mental Health The International Declaration on Youth Mental Health. 2013. http://www.iaymh.org/f.ashx/8909_Int-Declaration-YMH_print.pdf Available at: (Accessed: 13 July 2017)

- Alonzo D., Popescu M. Utilizing social media platforms to promote mental health awareness and help seeking in underserved communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2021;10(1) doi: 10.4103/JEHP.JEHP_21_21. Wolters Kluwer -- Medknow Publications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M., Auxier B. Social Media Use in 2021. Pew Research Center; 2021. pp. 1–6.https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Anthony K. Training Therapists to Work Effectively Online and Offline Within Digital Culture. Vol. 43. Routledge; 2015. pp. 36–42. (1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum M.L., et al. Role of social media and the internet in pathways to care for adolescents and young adults with psychotic disorders and non-psychotic mood disorders. Early Interv. Psychiatry. 2017;11(4):290–295. doi: 10.1111/eip.12237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore J.K., et al. Infertility influencers: an analysis of information and influence in the fertility webspace. J. Assist. Reprod. Genetics. 2020;37(6):1371–1378. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01799-2. 2020/05/07. Springer US. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonabi H., et al. Mental health literacy, attitudes to help seeking, and perceived need as predictors of mental health service use: a longitudinal study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2016;204(4):321–324. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000488. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brijnath B., et al. Do web-based mental health literacy interventions improve the mental health literacy of adult consumers? Results from a systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016;18(6) doi: 10.2196/JMIR.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley B., et al. My World Survey 2: The national study of youth mental health in Ireland. Dublin. 2019. http://www.myworldsurvey.ie/content/docs/My_World_Survey_2.pdf Available at:

- Eurostat Being young in Europe today, 2015 edition. 2015. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-statistical-books/-/KS-05-14-031 Available at:

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137–150. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3. The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gere B.O., Salimi N., Anima-Korang A. Social media use as self-therapy or alternative mental help-seeking behavior. IAFOR Journal of Psychology & the Behavioral Sciences. 2020;5((2):21–36. doi: 10.22492/IJPBS.5.2.02. The International Academic Forum (IAFOR) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear V.A., Armour K.M. Young People’s health-related learning through social media: what do teachers need to know? Teaching and Teacher Education. 2021;102:103340. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103340. Elsevier Ltd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczynski P., et al. Examining mental health literacy, help seeking behaviours, and mental health outcomes in UK university students. Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice. 2017;12(2):111–120. doi: 10.1108/JMHTEP-05-2016-0027. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver A., Griffiths K.M., Christensen H. Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young elite athletes: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-157. https://ucd.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1636821275?accountid=14507 Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M., et al. Keeping it fresh with hip-hop teens: promising targeting strategies for delivering public health messages to hard-to-reach audiences. Health Promotion Practice. 2020;21(1_suppl):61S–71S. doi: 10.1177/1524839919884545. SAGE Publications Inc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. Time Spent on Social Network Sites and Psychological Well-being: A Meta-analysis. Vol. 20. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.; 140 Huguenot Street, 3rd Floor New Rochelle, NY 10801 USA: 2017. pp. 346–354.https://home.liebertpub.com/cyber (6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Media Influencers, n.d.Social Media Influencers: Mega, Macro, Nano or Micro Influencers (no date). Available at: https://www.cmswire.com/digital-marketing/social-media-influencers-mega-macro-micro-or-nano/ (Accessed: 13 June 2022).

- Jorm A.F. Mental health literacy: Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000:396–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396. Cambridge University Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization'sworld mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):168–176. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18188442 Available at: (Accessed: 9 April 2020) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latha K., et al. Effective use of social media platforms for promotion of mental health awareness. J. Educ. Health Promotion. 2020;9:124. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_90_20. Wolters Kluwer - Medknow. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund J.A., et al. Exploring opportunities to support mental health care using social media: A survey of social media users with mental illness. Early Interv. Psychiatry. 2019;13(3):405–413. doi: 10.1111/eip.12496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund J.A., et al. Social media and mental health: benefits, risks, and opportunities for research and practice. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2020;5(3):245–257. doi: 10.1007/S41347-020-00134-X. Springer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly M., et al. Potential of social media in promoting mental health in adolescents. Health Promot. Int. 2019;34(5):981–991. doi: 10.1093/heapro/day056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnotta J., et al. Adolescents’ perceptions of their therapists’ social media competency and the therapeutic alliance. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2018;49(5–6):336–344. doi: 10.1037/PRO0000219. American Psychological Association Inc. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center . 2019. Social Media Factsheet.https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/ Available at: (Accessed: 29 March 2022) [Google Scholar]

- Power E., et al. Youth mental health in the time of COVID-19. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2020;37(4):301–305. doi: 10.1017/IPM.2020.84. Cambridge University Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius C., Coyle D. Young people’s use of digital tools to support their mental health during Covid-19 restrictions. Frontiers in Digital Health. 2021;0:175. doi: 10.3389/FDGTH.2021.763876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius C., et al. Young people seeking help online for mental health: cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Mental Health. 2019;6(8) doi: 10.2196/13524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius C., Chambers D., Coyle D. Young people’s online help-seeking and mental health difficulties: Systematic narrative review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019;21(11) doi: 10.2196/13873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickwood D.J., et al. Young People's Help-seeking for Mental Health Problems. Vol. 4. 2005. pp. 1–34.http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3159&context=hbspapers Available at: (Accessed: 13 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- Rickwood D.J., et al. Who are the young people choosing web-based mental health support? Findings from the implementation of Australia’s national web-based youth mental health service, eheadspace. JMIR Mental Health. 2016;3(3) doi: 10.2196/mental.5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott H., Biello S.M., Woods H.C. Social media use and adolescent sleep patterns: cross-sectional findings from the UK millennium cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J., et al. Research to clinical practice-youth seeking mental health information online and its impact on the first steps in the patient journey. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2022;145(3):301–314. doi: 10.1111/ACPS.13390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triplett N.T., et al. Ethics for mental health influencers: MFTs as public social media personalities. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2022:1–11. doi: 10.1007/S10591-021-09632-3. Springer. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- What is an Influencer?, n.d.What is an Influencer? - Social Media Influencers Defined [Updated 2022] (no date). Available at: https://influencermarketinghub.com/what-is-an-influencer/ (Accessed: 13 June 2022).

- Yang, Chen C., Holden S.M., Ariati J. Social media and psychological well-being among youth: the multidimensional model of social media use. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2021;24(3):631–650. doi: 10.1007/S10567-021-00359-Z. Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap J.E., et al. Mental health message appeals and audience engagement: Evidence from Australia. Health Promot. Int. 2019;34(1):28–37. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dax062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf H., et al. Association of a public health campaign about coronavirus disease 2019 promoted by news media and a social influencer with self-reported personal hygiene and physical distancing in the Netherlands. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(7) doi: 10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2020.14323. American Medical Association. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W., Zhang W.J., Tang L. What do social media influencers say about health? A theory-driven content analysis of top ten health influencers’ posts on Sina Weibo. Journal of Health Communication. 2021;26(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2020.1865486. Taylor & Francis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]