Abstract

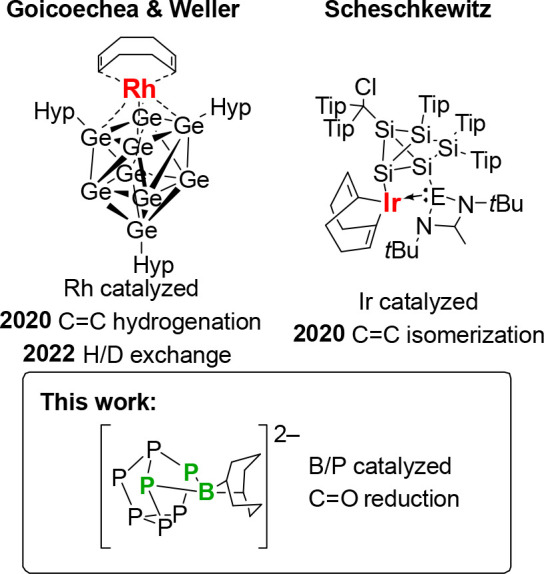

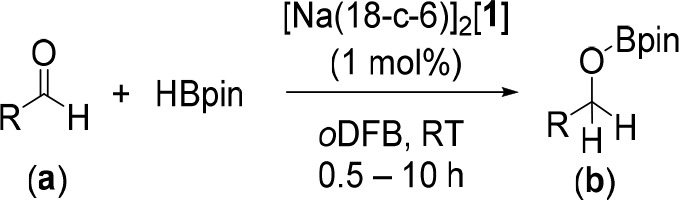

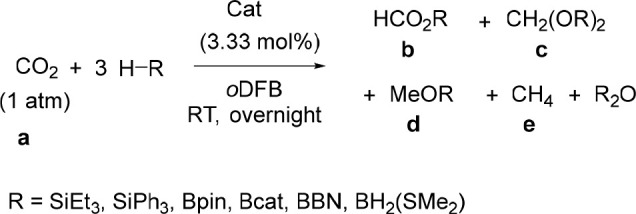

The first fully characterized boron-functionalized heptaphosphide Zintl cluster, [(BBN)P7]2– ([1]2–), is synthesized by dehydrocoupling [HP7]2–. Dehydrocoupling is a previously unprecedented reaction pathway to functionalize Zintl clusters. [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] was employed as a transition metal-free catalyst for the hydroboration of aldehydes and ketones. Moreover, the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2) was efficiently and selectively reduced to methoxyborane. This work represents the first examples of Zintl catalysis where the transformation is transition metal-free and where the cluster is noninnocent.

Introduction

Methanol (CH3OH) is a clean fuel and a highly important raw material for chemical industries.1−3 Over half of the world’s methanol is upcycled into everyday products, including pharmaceuticals, adhesives, agrochemicals, and paints/coatings. Producing methanol from carbon dioxide (CO2) has attracted global attention, because it converts a greenhouse gas into a resource that can re-enter the energy cycle. This approach is “two birds one stone” in contributing to global climate control and sustainable energy efforts.4,5 On an industrial scale, the conversion of atmospheric CO2 into methanol was first realized in 2012 by the George Olah Plant (Iceland), which produces up to 4500 m3 of methanol per year.6 The intrinsic stability of CO2 means that catalysts are essential for efficient reduction, and these are often based on expensive metals.7 The large-scale development and utilization of CO2 reduction necessarily requires any process to be sustainable and cost-effective, and so identifying less expensive and sustainable alternatives to these metals is an important target.

Heterogeneous phosphorus-containing materials represent one possible alternative to transition metals and are currently being explored for CO2 reduction.8,9 The synthesis of well-defined molecular analogues of these phosphorus materials offers the opportunity for mechanistic investigation, and molecular clusters offer an important middle ground between molecules and bulk solids. Zintl clusters, in particular, can be thought of as molecular mimics for heterogeneous materials:10 for example, the structure of [P7]3– can be viewed as a fragment of red phosphorus,11−14 which is an inexpensive and abundant material, albeit a challenging one to study because of its poor solubility. In contrast, [P7] cages, especially those that have been functionalized, are soluble in common laboratory solvents, offering a broader range of handles for in situ investigation. An improved understanding of reactivity patterns for [P7] could be extended to corresponding reactions with materials based on the many allotropes of phosphorus.

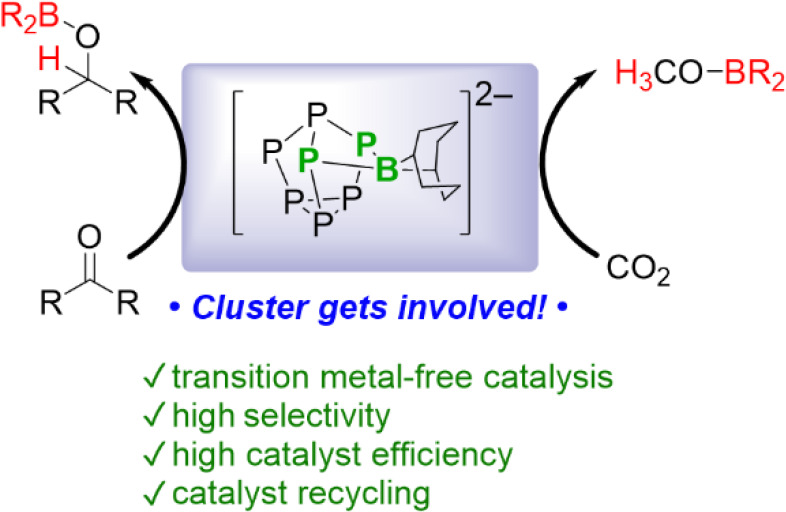

Only a small number of catalytic applications involving Zintl-derived clusters have been reported, where the cluster typically acts as a spectator ligand, supporting active rhodium or iridium centers10,15,16 (Figure 1) Catalysis of the reverse water–gas shift reaction by a Ru/Sn Zintl cluster, [Ru@Sn9]6–, has been reported in the recent literature, although the degree to which the cluster remains intact when deposited on a CeO2 surface remains to be established.17

Figure 1.

Zintl cluster catalysts. Hyp = Si(SiMe3)3, Tip = 2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl, E = Si, Ge, or Sn.

The reaction chemistry of clusters based on the [P7] framework is an emerging field,11,12,18 but salt metathesis with group 14 electrophiles has already proven to be a powerful route to functionalizing the cluster. Further, in 2012, Goicoechea and co-workers reported the use of the protonated heptapnictide clusters [HPn7]2– (Pn = P, As) in hydropnictination reactions with carbodiimides and isocyanates.19−21 They also reported that the [Pn7]3– (Pn = P, As) cluster reacted with alkynes to afford 1,2,3-tripnictolides,22,23 while reaction with carbon monoxide afforded the [PCO]− anion.24 In 2021, we reported that the trisilylated derivatives (R3Si)3P7 (R = Me, Ph) captured 3 equiv of heteroallene and underwent subsequent small-molecule exchange reactions.25

Herein we report that Zintl clusters based on the [P7] architecture are catalytically competent for borohydride reductions. Specifically, we prepare the transition metal-free functionalized heptaphosphide Zintl cluster shown in Figure 1 and establish its ability to catalyze the reduction of C=O bonds. Our initial focus is on the reduction of organic aldehydes and ketones, where the progress of reactions can readily be monitored via NMR spectroscopy, and then move on to heteroallenes where two double bonds are present. This then leads naturally to a survey of CO2 hydroboration, where complete selectivity to methoxyborane is observed. This Zintl catalyst displays turnover numbers, turnover frequencies, recyclability, and selectivity that are competitive with main group catalysts reported in the literature, under mild conditions.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Catalyst and Stoichiometric Studies

Inspired by advances made in molecular frustrated Lewis pair (FLP) chemistry,26−33 the synthesis of boron-functionalized group 15 Zintl clusters capable of C=O bond reductions was targeted. First, using literature protocols the [P7]3– salt34 and [HP7]2– salt19 were prepared. The [HP7]2– anion was then reacted with the 9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane dimer (HBBN dimer) to give [M(18-c-6)]2[(BBN)P7] ([M(18-c-6)]2[1]) as either the sodium or potassium salt, shown in Scheme 1, along with the elimination of H2: gas formation could be observed during these reactions. This dehydrocoupling chemistry has no precedent in current synthetic strategies toward functionalizing Zintl clusters. Salt metathesis reactions using BBNOTf (OTf = triflate), Cy2BI, or Cy2BOTf with [P7]3– did not result in functionalization of the cluster, but instead gave NMR spectra consistent with decomposition of the cluster.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of [M(18-c-6)]2[1].

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy studies of [M(18-c-6)]2[1] revealed five resonances in the 31P NMR spectrum, each exhibiting extensive P–P coupling, along with a single relatively sharp resonance in the 11B NMR spectrum at 11.14 ppm (Supporting Information, Figures S2 and S4). These spectroscopic features are consistent with the [P7] cage having a mirror plane and κ2-coordination of the BBN moiety to the cluster. Similar 31P NMR spectroscopic features were reported for the structurally related [(Ph2In)P7]2– cluster.35 Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies were performed on both sodium and potassium salts [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] and [K(18-c-6)]2[1]. In both cases, consistent with the spectroscopic data, the BBN moiety in [1]2– is coordinated to the [P7] fragment in a κ2-coordination mode (Figure 2). The average B–P bond length of 2.072 Å in[1]2– is somewhat longer than B–P bonds in typical borylphosphines (R2P–BR2, 1.889–1.953 Å) and considerably longer than those in typical phosphinoborenes (R2P=BR2, 1.762–1.857 Å), where P=B π bonding is significant. The sum of the angles around phosphorus is 276°, also typical of borylphosphines (284–328°) rather than phosphinoborenes (359.8–328.3°).36,37

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of [(BBN)P7]2– ([1]2–) in the [Na(18-c-6)]2[(BBN)P7] salt. Anisotropic displacement ellipsoids pictured at 50% probability. Hydrogen atoms, THF solvent molecules, and [Na(18-c-6)]+ countercations omitted for clarity. Phosphorus: orange; boron: green; carbon: white. Selected bond length [Å]: B1–P2 2.052(8), B1–P3 2.082(7), P1–P2 2.213(2), P1–P3 2.216(2), P1–P4 2.128(3), P2–P5 2.182(2), P3–P6 2.185(2), P4–P7 2.136(2), P5–P6 2.235(2), P5–P7 2.236(3), P6–P7 2.218(2); selected bond angles [deg]: P2–B1–P3 93.3(3).

All efforts to react [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] directly with H2 were unsuccessful. However, stoichiometric reactions of [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] with carbonyls, including benzaldehyde and acetophenone, and heteroallenes such as phenyl isocyanate and CO2, resulted in an immediate color change from orange to red. Unfortunately, and despite multiple efforts, XRD diffraction quality crystals could not be obtained from any of these reactions, but in situ31P and 11B NMR spectroscopy confirmed the disappearance of [Na(18-c-6)]2[1], along with the formation of novel (asymmetric)25 functionalized clusters that would be consistent with formation of a carbonyl or heteroallene adduct (see Supporting Information, Figures S126–S138). We note that others have previously isolated and crystallographically characterized adducts of carbonyls or heteroallenes with FLPs where the C–O bond bridges the B···P gap.38−41 The clear color change and disappearance of [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] in these carbonyl and heteroallene reactions but not with H2 follows established reactivity patterns for borylphosphines42 rather than phosphinoborenes.43

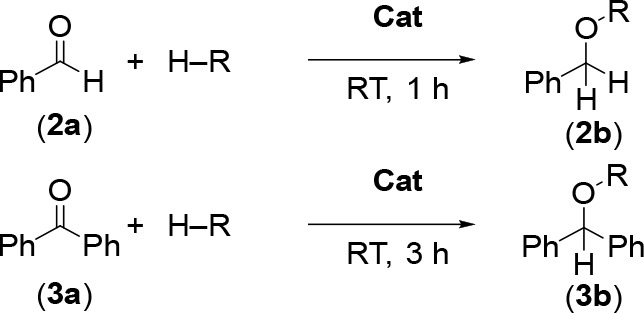

Catalytic Reduction of Carbonyls

[M(18-c-6)]2[1] salts (M = Na, K) were then explored for their potential as catalysts in the reduction of carbonyls, a transformation that is widely employed by the pharmaceutical, agrochemical, polymer, and fine chemical industries.44 Initially the reduction of benzaldehyde and benzophenone was targeted (Table 1). In tetrahydrofuran (THF) with 5 mol % [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] catalyst loading and the mild reductant pinacolborane (HBpin), the hydroboration of benzaldehyde (2a) and benzophenone (3a) was quickly achieved at room temperature (RT) to give the benzyloxyboranes 2b and 3b in high yields. Lowering the catalysts loading under the same conditions decreased the conversion, but it was found that a change of solvent to ortho-difluorobenzene (oDFB) improved the yield, giving near quantitative conversions even at 1 mol % catalyst loadings, under similar conditions. Hydrosilylation of the carbonyls using triethylsilane and triphenylsilane was also tested, but no reactions were observed. Changing the countercation from sodium to potassium did not affect catalyst performance. Control reactions confirmed that catalyst [M(18-c-6)]2[1] was necessary and also that the unfunctionalized K3P7 salt was completely inactive in this hydroboration. The [Na(18-c-6)]2[HP7] salt was also tested as a precatalyst and displayed lower catalytic performance compared to [M(18-c-6)]2[1].

Table 1. Reaction Condition Optimization for the Hydroboration of Carbonyls.

| catalyst (mol %) | T, °C | H–R | solvent | 2b conv (%)a | 3b conv (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] (5) | RT | HBpin | THF | 92 | 80 |

| [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] (1) | RT | HBpin | THF | 76 | 48 |

| [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] (1) | RT | HBpin | oDFB | >99(94) | >99(96) |

| [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] (1) | 50 | Et3SiH | oDFB | 0 | 0 |

| [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] (1) | 50 | Ph3SiH | oDFB | 0 | 0 |

| [K(18-c-6)]2[1] (1) | RT | HBpin | THF | 75 | 52 |

| [K(18-c-6)]2[1] (1) | RT | HBpin | oDFB | >99 | >99 |

| [Na(18-c-6)]2[HP7] (5)b | RT | HBpin | oDFB | 69 | 60 |

| K3P7 (5) | RT | HBpin | THF | 0 | 0 |

| [K(18-c-6)]3[P7] (5) | RT | HBpin | THF | 0 | 0 |

| none | RT | HBpin | THF | 0 | 0 |

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Isolated yields are given in parentheses.

Precatalyst.

Using 1 mol % [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] in oDFB, the scope of aldehyde hydroborations was expanded to include the substrates shown in Table 2. Similar to the hydroboration of benzaldehyde (2a), hydroboration of 2-formyl pyridine (4a) showed quantitative conversion to 4b after 30 min. In contrast, introducing electron-withdrawing groups in the 4-position of the benzaldehyde resulted in longer reaction times. In the case of (1,1′-biphenyl)-4-carbaldehyde (5a), 4-(pyridin-4-yl)benzaldehyde (6a), 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzaldehyde (7a) and 4-bromobenzaldehyde (8a), complete conversion to the hydroborated products 5b–8b was obtained after 5–10 h. Electron-donating groups on the 2-position of the benzaldehyde (aldehydes 9a and 10a) also required longer reaction times to give complete conversion, presumably due to increased steric crowding. Unsaturated aliphatic substituted aldehydes 11a and 12a showed selective hydroboration of the C=O bond and yielded products 11b and 12b, respectively. Hydroboration of acetylaldehyde (13a) was found to result in a mixture of paraldehyde and the desired hydroborated product 13b.

Table 2. Catalytic Hydroboration of Aldehydes.

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Isolated yields are given in parentheses.

5 equiv of substrate was used because it quickly evaporates from the reaction mixture.

Next, the scope of ketone hydroborations was extended (Table 3). Substituting one phenyl group of benzophenone for a 2-pyridyl group (3a vs 14a) leads to a significantly longer reaction time (3 vs 18 h, respectively). In contrast, the hydroboration of di(pyridyl) ketone (15a) only required 30 min to give complete conversion to 15b. Coordination of the pyridyl group on the aldehyde to free HBpin could be a factor in determining the rate of these reactions; in support of this proposal, it was found that one of the pyridine nitrogens of 15b coordinates to the Bpin boron center in its crystal structure (Supporting Information, Figure S66). Similar to the hydroboration of benzophenone (3a), acetophenone (16a) and thiophene-2-carboxaldhyde (17a) gave complete conversion to 16b and 17b, respectively, after 30 min.

Table 3. Catalytic Hydroboration of Ketones.

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Isolated yields are given in parentheses.

The incorporation of electron-withdrawing substituents resulted in longer reaction times, for example in the case of 1-(perfluorophenyl)ethan-1-one (18a) and acetylferrocene (19a), which required 72 h to give high conversions to 18b and 19b, respectively. The sterically bulky adamantanone (20a) gave 20b after 18 h. The alkyl-substituted ketone cyclobutyl methyl ketone (21a) resulted in 21b after 2 h. Introduction of ethynyl and alkenyl groups on the ketone (22a and 23a) resulted in the formation of byproducts, decreasing the conversion to the desired hydroborated product.

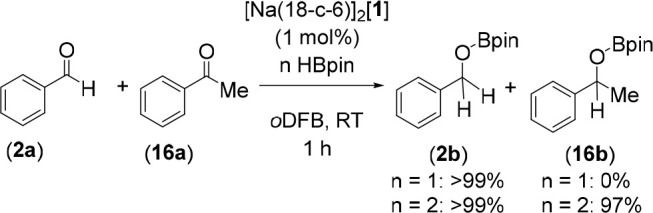

To investigate the chemoselectivity of carbonyl hydroborations, a competition reaction was carried out between benzaldehyde, 2a, and acetophenone, 16a, with 1 equiv of HBpin (Scheme 2). Exclusive hydroboration of benzaldehyde was observed under these conditions, but addition of a second equivalent of HBpin resulted in hydroboration of the acetophenone as well. Neither 2b or 16b was found to undergo deoxygenation in the presence of an excess of HBpin. The selectivity of reduction toward aldehydes in the presence of ketones is consistent with literature precedent45−47 and with the data in Table 1, which shows higher degrees of conversion for 2a compared to 3a.

Scheme 2. Competition Reaction between Benzaldehyde (2a) and Acetophenone (16a).

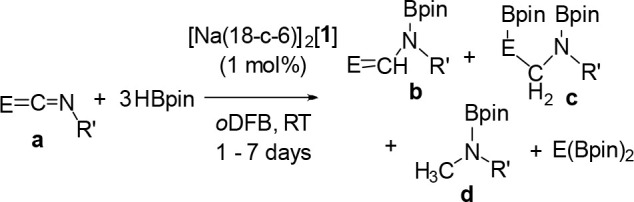

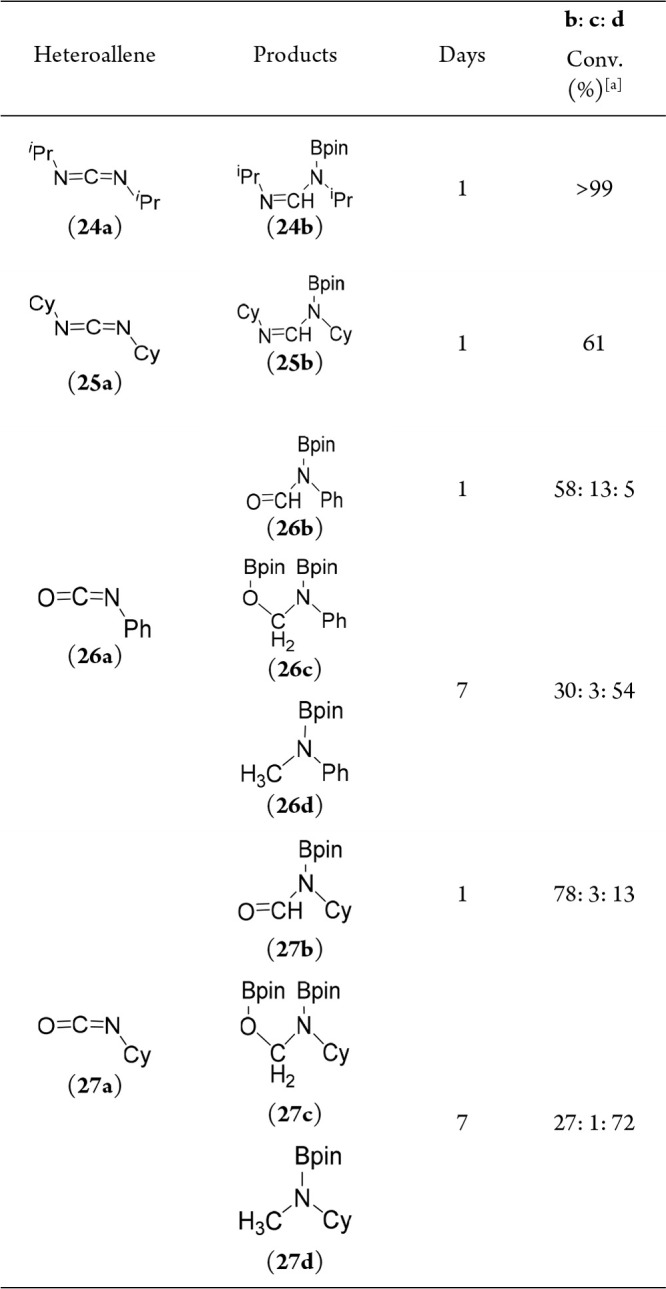

Catalytic Reduction of Heteroallenes

Encouraged by the catalytic hydroboration of carbonyls, we next extended the scope to heteroallenes, including both carbodiimides and isocyanates (Table 4). Three equivalents of HBpin was used in these transformations to probe the potential for deoxygenation or denitrogenation. Hydroboration of carbodiimide (iPrN)2C (24a) gave exclusively the mono-hydroborated product iPr(Bpin)NCHNiPr (24b), with no evidence for bis-hydroborated or denitrogenated products even over prolonged reaction times and at elevated temperatures (50 °C). The same reaction with (CyN)2C (25a) also gave the mono-hydroborated product, (Cy(Bpin)N)CHNCy (25b), whereas the hydroboration of isocyanates PhNCO (26a) and CyNCO (27a) gave detectable mixtures of the mono-hydroborated (26b and 27b), bis-hydroborated (26c and 27c), and deoxygenated (26d and 27d) products. Longer reaction times favored the deoxygenated products 26d and 27d, with 54–72% conversion obtained after 7 days.

Table 4. Hydroboration of Heteroallenes.

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy, based on C–H bond formation.

Catalytic Reduction of CO2

Isocyanates (RN=C=O) are, of course, structurally related to the greenhouse gas CO2 (O=C=O), and so the successful deoxygenation of isocyanates to methyl amines motivated further investigations into the catalytic reduction of CO2. Molecular main group catalysts to convert CO2 to products such as formic acid (HCOOH), methanol (CH3OH), methane (CH4), and carbon monoxide (CO) have been previously reported,48 perhaps the best known of which are the FLP catalysts used to hydroborate or hydrosilylate CO2.29,49

Triethylsilane and triphenylsilane were tested in the catalytic reduction of CO2 and gave no conversion (Table 5), confirming that, as was the case for the carbonyl compounds, silanes are not suitable reducing agents to drive the reduction of CO2 using[Na(18-c-6)]2[1] as a catalyst. Next, 3 equiv of HBpin with 3.33 mol % [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] was pressurized with 1 atm of CO2 at RT and found to give a mixture of products. In good agreement with literature reported chemical shifts,50 the formic acid (Table 5, b), acetal (Table 5, c), methanol (Table 5, d), and methane (Table 5, e) oxidation levels could be identified in the reaction mixture. Using 3.33 mol % [Na(18-c-6)]2[1], common borane reductants and solvents were screened (see Supporting Information Section 5.1). Catecholborane (HBcat) and borane dimethylsulfide (BH3·SMe2) did not result in detectable amounts of product, but when the HBBN dimer, which has pinned back aliphatic groups and an accessible hydride, is used as the reductant, the conversion is 95% with a product distribution of 1:9 formylborane (28b):methoxyborane (28d). Control experiments confirmed that the naked [P7]3– clusters (as K or K(18-c-6) salts) or HBBN dimer as catalyst is not independently catalytically active (Table 5, entries 7–9). The tris-functionalized P7 cluster (Me3Si)3P7 was also prepared34 and found to be catalytically inactive (Table 5, entry 10). These controls confirm that the BBN moiety and P7 cluster of [1]2– cooperate to enable catalytic activity.

Table 5. Screening Conditions for CO2 Reduction.

| entry | catalyst | H–R | b conv (%)a | c conv (%)a | d conv (%)a | e conv (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] | Et3SiH | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] | Ph3SiH | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] | HBpin | 3 | 1 | 31 | 10 |

| 4 | [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] | HBcat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] | BH3·SMe2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] | (HBBN)2 | 11 | 0 | 84 | 0 |

| 7 | none | (HBBN)2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | K3P7 | (HBBN)2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | [K(18-c-6)]3P7 | (HBBN)2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | (Me3Si)3P7 | (HBBN)2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy, based on C–H bond formation.

The effect of varying reaction conditions with the HBBN dimer as the reductant is summarized in Table 6. Reducing the catalyst loading from 3.33 mol % to 0.33 mol % increased the selectivity toward methoxyborane (MeOBBN, 28d) to >99%, while the introduction of toluene as a cosolvent improved solubility of (HBBN)2 and thus increased the turnover frequency (TOF). Increasing the temperature from RT to 50 °C further increased the TOF to 300 while lowering the catalyst loading to 0.01 mol %, giving the maximum turnover number (TON) of 9800. Cluster decomposition is observed above 50 °C, limiting catalyst screening conditions at high temperatures. The maximum TON and TOF (Table 6, entries 3 and 5) are high compared to previously reported main group catalysts for this transformation (see Supporting Information Table S7).

Table 6. Catalytic Hydroboration of CO2 to MeOBBN.

| entry | [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] (X mol %)a | time (h) | T (°C) | 28d conv (%)b | TONb | TOF (h–1)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1c | 0.33 | 12 | RT | >99 | 300 | 25 |

| 2 | 0.33 | 10 | RT | >99 | 300 | 30 |

| 3 | 0.33 | 1 | 50 | >99 | 300 | 300 |

| 4 | 0.1 | 32 | RT | >99 | 1000 | 31 |

| 5 | 0.01 | 480 | RT | 98 | 9800 | 20 |

| 6 | 0.01 | 40 | 50 | 95 | 9476 | 237 |

Relative to B–H bonds.

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy, based on C–H bond formation.

Alternative conditions: only oDFB as solvent.

Boron–phosphorus FLP systems reported by Fontaine and Stephan also show excellent activity with TONs between 2950 and 5556 and TOFs between 176 and 853 h–1.51,52 However, these catalysts required more forcing conditions (higher temperature and/or pressure) than the ones reported here. Under the mild conditions described here TOFs in the range 2.6–50 h–1 and TONs between 99 and 648 have been reported by Goicoechea, Datta and Mandal, Cantat, Song, and Ramos.53−57 Meaningful comparisons can be made between [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] and Cantat’s P(MeNCH2CH2)3N catalyst.58 Both show similar maximum TOFs ([Na(18-c-6)]2[1]: 237 h–1; P(MeNCH2CH2)3N: 287 h–1), but significantly higher maximum TONs can be achieved with catalyst [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] ([Na(18-c-6)]2[1]: 9800; P(MeNCH2CH2)3N: 6043).

In addition to the excellent TON observed, catalyst [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] was found to be surprisingly robust: after complete catalytic hydroboration of CO2 to methoxyborane (28d) no decomposition of [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] was detected by NMR spectroscopy. To investigate whether catalyst [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] could be recycled, the reaction sample was reloaded with 3 equiv of HBBN and 1 atm of CO2. Again, at RT, complete conversion to 28d was observed overnight. Catalyst [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] was recycled a total of seven times with no loss of catalyst activity, consistent with living catalysis. After these cycles, water hydrolysis of methoxyborane gave methanol in complete conversion: 0.62 mmol of methanol was produced using 0.9 μmol of catalyst (a 689-fold excess of methanol).

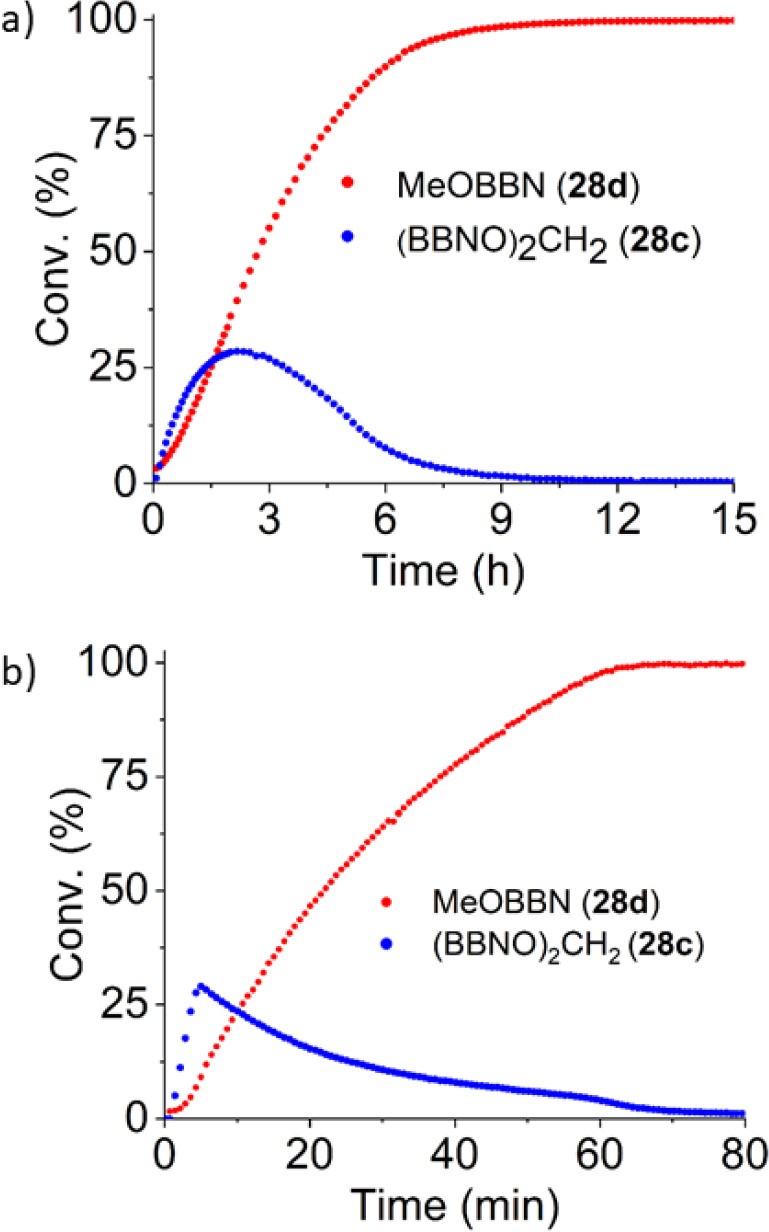

The CO2 hydroboration with HBBN dimer was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy with 0.33 mol % [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] at room temperature and 50 °C (Table 6, entries 2, 3). In both cases, intermediate CH2(OBBN)2 (28c) quickly formed and then was consumed (Figure 3). Meanwhile 28d is formed gradually throughout the reaction. In line with literature reports, the intermediate formyl-BBN (28b) was not detected under these conditions and is presumed to be significantly more reactive toward hydroboration compared to CO2, 28c, and 28d.

Figure 3.

Tracked reaction: (a) reaction at RT; (b) reaction at 50 °C.

Stoichiometric reduction of CO2 using equimolar [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] and HBBN exclusively gave HC(O)OBBN (28b). Further, reaction of [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] with 2 equiv of HBBN under a CO2 atmosphere again exclusively gave 28b, indicating that CO2 is not trapped and reduced to 28b then further reduced to 28c and 28d while intact on the catalyst. Rather, the evidence suggests that 28b is released after one addition of borane but then re-enters the catalytic cycle to form 28c and 28d.

Mimicking catalytic conditions, 28b could be independently prepared in situ by addition of an excess of HBBN to formic acid in oDFB/toluene over 20 h. After generation of 28b, there is no further reaction with excess HBBN. However, when [1]2– was added to the reaction mixture, formation of 28c and 28d was observed. This observation is consistent with (1) the need for [1]2– in the reduction of 28b and (2) 28b being an intermediate in CO2 hydroboration and not a side product.

Mechanistic Investigations

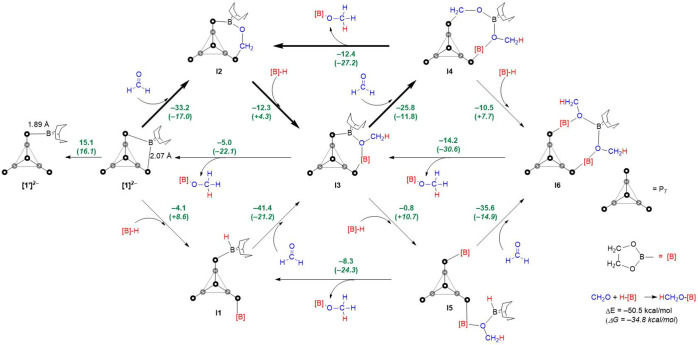

In order to probe the mechanistic landscape for the reduction of C=O functional groups, we have performed DFT calculations on the simplest model substrate, formaldehyde (Figure 4). The optimized structure of [1]2– reproduces the crystallographic data with good accuracy: the optimized B–P bond lengths are 2.07 Å (vs 2.052(8) and 2.082(7) Å in Figure 2), while P1–P2 and P1–P3 are 2.21 Å vs crystallographic values of 2.213(2) and 2.216(2) Å, respectively. In its equilibrium structure, the boron center in [1]2– is saturated by two B–P bonds, but a wider survey of the potential energy surface reveals a second shallow local minimum only 15.1 kcal/mol above the equilibrium structure, where the BBN fragment is coordinated to only one of the two phosphorus centers (isomer [1′]2–, Figure 4). In this case the single B–P bond length is 1.89 Å, precisely in the range for borylphosphines.

Figure 4.

Energies and zero-point-corrected free energies (in parentheses) of possible steps on the [1]2–-catalyzed reduction pathway of H2C=O with HBpin. All calculations were performed at the wB97XD, def2-TZVP level. All energies are given in kcal/mol. The energies in each of the six triangles sum to the overall energy of CH2O + H–[B] → HCH2O–[B], and each therefore constitutes a viable catalytic cycle. Based on the experimental evidence supporting the presence of I2 and I4, we favor the cycle highlighted with bold arrows as the dominant one (see text for more detailed discussion).

In the mechanistic scheme shown in Figure 4, a number of possible intermediates that are related by the addition of [B]H or formaldehyde or by the release of the product MeO[B] are identified. The changes in energy and zero-point-corrected free energy for the overall reaction H2CO + [B]H → MeO[B] are −50.5 and −34.8 kcal/mol, respectively, and the energies around each of the six triangles shown in Figure 4 sum to exactly these values. The cycle in the top left of the figure involves exothermic addition of H2CO to [1]2– to form I2, followed by marginally exothermic addition of H[B] to form the methoxy derivate, I3, where the OMe group bridges the two boron centers. Loss of the product to regenerate [1]2– is then moderately exothermic (−5.0 kcal/mol) but strongly favored on the free energy scale (−22.1 kcal/mol). The alternative pathway via initial activation of the borohydride (lower left triangle in Figure 4) proceeds via a marginally exothermic first step followed by a very exothermic binding and reduction of formaldehyde (ΔE = −41.4 kcal/mol). Both cycles, [1]2– + CH2O + [B]H → I1 or I2 → I3 → [1]2– + MeO[B], therefore present a plausible cascade leading from reactants to products. We note, however, that only one of the two B–P bonds has been activated in I3, leaving open the possibility of a further series of reactions involving reaction of I3 with second equivalents of formaldehyde and borohydride to form I6 (via I4 or I5 depending on the order of addition) followed by release of MeO[B] to regenerate I3. The energies of the various steps in the cycle I3 + CH2O + [B]H → I4 or I5 → I6 → I3 + MeO[B] are strikingly similar to those for the original cycle ([1]2– + CH2O + [B]H → I1 or I2 → I3 → [1]2– + MeO[B]), other than a marginal decrease in exothermicity of the steps that involve binding of substrate and an increased exothermicity of the final release of product, both of which reflect the greater steric crowding as more molecules are assembled around the catalyst. Nevertheless, it is clear that the second B–P bond in I3 remains capable of binding further substrate molecules.

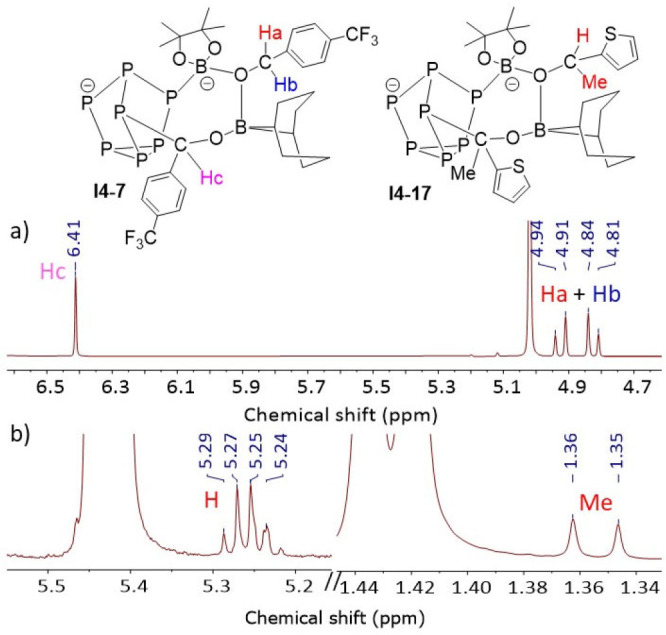

Some support for the presence of I4 in solution comes from monitoring of the hydroboration of 5a, 7a, 11a, 14a, and 17a (see Supporting Information, Section 6.4). 1H NMR studies on the hydroboration of 5a, 7a, and 11a reveal the presence of a second-order AB spin system with similar chemical shifts and coupling as the hydroborated products (selected spectra, Figure 5a). The AB spin system is consistent with the presence of a pair of enantiotopic protons displaying a 10–12 Hz geminal coupling, an assertion that is further supported by 1H correlated NMR spectroscopy (COSY) studies (Supporting Information, Figure S142). 1H diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy (DOSY) studies on the hydroboration of 7a (Supporting Information, Figure S143) confirmed that the species giving rise to the AB spin system has the lowest diffusion coefficient, indicating that it is the largest species present in the reaction mixture, in line with the proposed structure for I4 given in Figure 4. In contrast, the analogues of I4 detected from the hydroboration of the ketones 14a and 17a, where only a single proton is present, display similar resonances but without further geminal coupling (selected spectra, Figure 5b). The characteristic resonances for I4 are observed only during the reaction and disappear when the reaction is complete. Moreover, addition of 500 equiv of 7b to in situ generated I2 did not result in formation of I4, confirming the irreversibility of the I4 → I2 step.

Figure 5.

1H NMR spectroscopic monitoring of hydroboration of (a) 7a and (b) 17a.

In contrast, a direct spectroscopic signature of I2 could not be identified in any of the reactions with aldehydes or ketones. However, we note that insertion of carbonyl groups into P–B bonds has precedent in the work by Fontaine and Ramos, where C–O bonds in the crystallographically characterized products are typically in the range 1.39–1.40 Å.57 The optimized structure of I2 (Supporting Information, Figure S165) shows a similarly activated C–O bond (C–O = 1.37 Å, B–O = 1.47 Å), along with a short P–C bond length of 1.89 Å. Moreover, during stoichiometric CO2 capture experiments with [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] using 13C-labeled CO2, we observe a doublet at 194.13 ppm with 1JCP = 49 Hz in the 13C{1H} NMR spectrum. A C–P coupling constant of this magnitude is qualitatively consistent with the presence of a direct C–P bond as in I2 (or indeed I4), and the DFT-computed value (wB97XD/def2-TZVP) in the analogue of I2 with CO2 (see Supporting Information, Figure S170) rather than formaldehyde as substrate is 41 Hz.

The presence of significant concentrations of I4 would, in principle, also opens up the possibility of a third cycle, I2 + CH2O + [B]H → I3 → I4 → I2 + MeO[B] (Figure 4, top, center), where the total exothermicity of −50.4 kcal/mol is distributed evenly across the borohydride binding, formaldehyde binding, and product release steps (−12.3, −25.8, and −12.4 kcal/mol, respectively). In their recent study of CO2 reduction using Ph2PCH2CH2BBN, Ramos et al. have argued that trapping of CO2 by the B/P FLP leads to formation of a formaldehyde adduct analogous to I2,57 which, in fact, acts as the active catalyst in the dominant CO2 reduction cycle. By analogy, [1]2– would then be a precursor, lying outside the main cycle, while I2 is the active catalyst. Musgrave and co-workers have highlighted the “anticatalytic” role of the Lewis base in frustrated Lewis pairs:59 the Lewis base, in binding to the nucleophilic site (the carbonyl carbon here), reduces its susceptibility to subsequent attack by the reducing agent. In the present context, the very strong binding of formaldehyde to [1]2– (−33.2 kcal/mol) will reduce its susceptibility to attack by borohydride, and so the somewhat weaker binding of the second aldehyde (I3 + H2CO → I4, −25.8 kcal/mol) may accelerate its subsequent reduction by borohydride. The computed energetics, combined with the spectroscopic evidence for the presence of I2 and I4 in solution and the literature precedent for species like I2 to act as catalysts, leads us to propose that this cycle is likely to dominate the reaction. At this point, however, we offer an important caveat, that the binding of the carbonyl group is strongly dependent on the size of the R and R′ groups: the −33.2 kcal/mol computed for the binding of H2CO to [1]2– is reduced to −25.2 kcal/mol for benzaldehyde (PhCHO). The energetics in Figure 4 for the simplest model aldehyde, formaldehyde, therefore offer an overview of potential intermediates on the mechanistic landscape, but should not be taken to apply quantitatively to any of the experimental data summarized in Tables 1–3.

Stoichiometric studies between [Na(18-c-6)]2[1], acetophenone, and HBpin confirmed (Scheme 3) compound 16b to be the major product, but its BBN analogue 16b′ was also detected as a minor product in a 95:5 ratio. One possible source of the minor isomer is the methoxy-bridged intermediate, I3 in Figure 4, where the oxygen is almost symmetrically bonded to both boron centers (B–O = 1.59 and 1.60 Å to the BBN and [B] groups, respectively). Cleavage of the two almost equivalent B–O bonds could then lead to either 16b or 16b′. At the wB97XD/def2-TZVP level, decomposition to give 16b′ (+ [B]–P7) was found to be less favorable by 15.1 kcal/mol (ΔG = −16.2 kcal/mol) than to 16b (+ [1]2–), qualitatively consistent with the observed product distribution. The formation of 16b′ in the experiment does, however, indicate a 5% degradation of the catalyst under these conditions. Of course, a cluster functionalized with Bpin ([(Bpin)P7]2–) could also be catalytically active, following equivalent pathways to those shown in Figure 4, and a catalytic role for [(Bpin)P7]2– would be consistent with our description of the [Na(18-c-6)]2[HP7] salt as a precatalyst in Table 1. We have not, however, been able to isolate or independently synthesize this species and test its catalytic performance, despite multiple attempts to do so. It is noteworthy that catalyst degradation via this route is not an issue when the HBBN dimer is used as a reducing agent, as it is in our experiments on CO2 hydroboration, simply because the analogue of I3 is then symmetric.

Scheme 3. Stoichiometric Hydroboration of Acetophenone.

The mechanism of the CO2 and heteroallene reduction reactions will be the subject of a further study, but it seems likely that, in their initial stages, at least, they will share many common features with the formaldehyde reaction shown in Figure 4. The geometries of the analogues of I2 with CO2, HNCNH, and HC≡CCHO shown in Supporting Information, Figure S170, certainly show no significant differences in the binding mode of the substrate to [1]2–.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a boron-functionalized group 15 Zintl cluster, [(BBN)P7]2– ([1]2–), is prepared and found to be competent in the catalytic hydroboration of C=O bonds. Aldehydes, ketones, carbodiimides, isocyanates, and CO2 are all reduced, and, in the case of CO2 hydroboration, based on catalyst performance alone, [Na(18-c-6)]2[1] is competitive with other main group catalysts. Further, high selectivity to methoxyborane under mild conditions and catalyst recycling is established. This work represents the first application of a Zintl cluster in transition metal-free catalysis and establishes clearly that the cluster itself can play an active role in the catalytic cycle beyond that of a spectator ligand.

Acknowledgments

We thank the EPSRC for funding (EP/V012061/1) and supporting a DTA studentship (B.v.I.). We thank the Royal Society (RGS/R1/211101) for supporting a consumables budget. We are also grateful to the UK Materials and Molecular Modelling Hub for computational resources, which is partially funded by EPSRC (EP/P020194/1 and EP/T022213/1). We also thank Gareth Smith for mass spectrometric analyses, Anne Davies and Martin Jennings for elemental analyses, and Ralph Adams for NMR spectroscopic enquiries. S.F.A. acknowledges the Saudi government for a postgraduate scholarship.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- RT

room temperature

- HBpin

pinacolborane

- HBBN

9-borabicyclo(3.3.1)nonane

- oDFB

ortho-difluorobenzene

- XRD

X-ray diffraction

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- OTf

triflate

- DFT

density functional theory

- FLP

frustrated Lewis pair

- COSY

correlation spectroscopy

- DOSY

diffusion-ordered spectroscopy

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c08559.

The general information, experimental procedures, characterization data, and computational details (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Müller L. J.; Kätelhön A.; Bringezu S.; McCoy S.; Suh S.; Edwards R.; Sick V.; Kaiser S.; Cuéllar-Franca R.; El Khamlichi A.; Lee J. H.; von der Assen N.; Bardow A. The Carbon Footprint of the Carbon Feedstock CO2. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13 (9), 2979–2992. 10.1039/D0EE01530J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Zhang G.; Song C.; Guo X. Catalytic Conversion of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol: Current Status and Future Perspective. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 8, 62119. 10.3389/fenrg.2020.621119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roode-Gutzmer Q. I.; Kaiser D.; Bertau M. Renewable Methanol Synthesis. ChemBioEng. Reviews 2019, 6 (6), 209–236. 10.1002/cben.201900012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwarere S. A.; Ramjugernath D. In Carbon Dioxide to Energy: Killing Two Birds with One Stone; Raghavan K. V.; Ghosh P., Eds.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2017; pp 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Roy S.; Cherevotan A.; Peter S. C. Thermochemical CO2 Hydrogenation to Single Carbon Products: Scientific and Technological Challenges. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3 (8), 1938–1966. 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b00740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goeppert A.; Czaun M.; Jones J.-P.; Surya Prakash G. K.; Olah G. A. Recycling of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol and Derived Products – Closing the Loop. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43 (23), 7995–8048. 10.1039/C4CS00122B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Jaén S.; Virginie M.; Bonin J.; Robert M.; Wojcieszak R.; Khodakov A. Y. Highlights and Challenges in the Selective Reduction of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 564–579. 10.1038/s41570-021-00289-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G.-Q.; Hu J.; Long X.; Zou J.; Yu J.-G.; Jiao F.-P. A Critical Review on Black Phosphorus-Based Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction Application. Small 2021, 17 (49), 2102155. 10.1002/smll.202102155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung C.-M.; Er C.-C.; Tan L.-L.; Mohamed A. R.; Chai S.-P. Red Phosphorus: An Up-and-Coming Photocatalyst on the Horizon for Sustainable Energy Development and Environmental Remediation. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122 (3), 3879–3965. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townrow O. P. E.; Chung C.; Macgregor S. A.; Weller A. S.; Goicoechea J. M. A Neutral Heteroatomic Zintl Cluster for the Catalytic Hydrogenation of Cyclic Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (43), 18330–18335. 10.1021/jacs.0c09742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turbervill R. S. P.; Goicoechea J. M. From Clusters to Unorthodox Pnictogen Sources: Solution-Phase Reactivity of [E7]3– (E = P–Sb) Anions. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (21), 10807–10828. 10.1021/cr500387w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn B.; Mehta M. Frontiers in the Solution-Phase Chemistry of Homoatomic Group 15 Zintl Clusters. Dalton Trans 2020, 49 (42), 14758–14765. 10.1039/D0DT02890H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragulescu-Andrasi A.; Miller L. Z.; Chen B.; McQuade D. T.; Shatruk M. Facile Conversion of Red Phosphorus into Soluble Polyphosphide Anions by Reaction with Potassium Ethoxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55 (12), 3904–3908. 10.1002/anie.201511186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo M.; Dragulescu-Andrasi A.; Miller L. Z.; Pak C.; Shatruk M. Nucleophilic Activation of Red Phosphorus for Controlled Synthesis of Polyphosphides. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59 (8), 5483–5489. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c00108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poitiers N. E.; Giarrana L.; Huch V.; Zimmer M.; Scheschkewitz D. Exohedral Functionalization vs. Core Expansion of Siliconoids with Group 9 Metals: Catalytic Activity in Alkene Isomerization. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (30), 7782–7788. 10.1039/D0SC02861D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townrow O. P. E.; Duckett S. B.; Weller A. S.; Goicoechea J. M. Zintl Cluster Supported Low Coordinate Rh(i) Centers for Catalytic H/D Exchange Between H2 and D2. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 7626–7633. 10.1039/D2SC02552C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Zhang C.; Wang X.; Guo J.; Sun Z.-M.; Zhang H. Site-Selective CO2 Reduction over Highly Dispersed Ru-SnOx Sites Derived from a [Ru@Sn9]6– Zintl Cluster. ACS Catal. 2020, 10 (14), 7808–7819. 10.1021/acscatal.0c01253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. J.; Weinert B.; Dehnen S. Recent Developments in Zintl Cluster Chemistry. Dalton Trans 2018, 47 (42), 14861–14869. 10.1039/C8DT03174F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turbervill R. S. P.; Goicoechea J. M. Studies on the Reactivity of Group 15 Zintl ions with Carbodiimides: Synthesis and Characterization of a Heptaphosphaguanidine Dianion. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48 (10), 1470–1472. 10.1039/C1CC12089A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turbervill R. S. P.; Goicoechea J. M. Hydropnictination Reactions of Carbodiimides and Isocyanates with Protonated Heptaphosphide and Heptaarsenide Zintl Ions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 2014 (10), 1660–1668. 10.1002/ejic.201301011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turbervill R. S. P.; Goicoechea J. M. Hydrophosphination of Carbodiimides Using Protic Heptaphosphide Cages: A Unique Effect of the Bimodal Activity of Protonated Group 15 Zintl Ions. Organometallics 2012, 31 (6), 2452–2462. 10.1021/om300072z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turbervill R. S. P.; Goicoechea J. M. An Asymmetrically Derivatized 1,2,3-Triphospholide: Synthesis and Reactivity of the 4-(2′ -Pyridyl)-1,2,3-triphospholide Anion. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52 (9), 5527–5534. 10.1021/ic400448x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turbervill R. S. P.; Jupp A. R.; McCullough P. S. B.; Ergöçmen D.; Goicoechea J. M. Synthesis and Characterization of Free and Coordinated 1,2,3-Tripnictolide Anions. Organometallics 2013, 32 (7), 2234–2244. 10.1021/om4001296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jupp A. R.; Goicoechea J. M. The 2-Phosphaethynolate Anion: A Convenient Synthesis and [2 + 2] Cycloaddition Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52 (38), 10064–10067. 10.1002/anie.201305235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn B.; Vitorica-Yrezabal I.; Whitehead G.; Mehta M. Heteroallene Capture and Exchange at Functionalised Heptaphosphane Clusters. Chem.—Eur. J. 2022, 28 (6), e202103737 10.1002/chem.202103737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W. The Broadening Reach of Frustrated Lewis Pair Chemistry. Science 2016, 354 (6317), aaf7229 10.1126/science.aaf7229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W. Catalysis, FLPs, and Beyond. Chem. 2020, 6 (7), 1520–1526. 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lam J.; Szkop K. M.; Mosaferi E.; Stephan D. W. FLP Catalysis: Main Group Hydrogenations of Organic Unsaturated Substrates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48 (13), 3592–3612. 10.1039/C8CS00277K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley A. E. O. H. D.FLP-Mediated Activations and Reductions of CO2 and CO; Springer: Berlin, 2012; Vol. 334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan D. W.; Erker G. Frustrated Lewis Pair Chemistry: Development and Perspectives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54 (22), 6400–6441. 10.1002/anie.201409800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N.; Zhang W.-X. Frustrated Lewis Pairs: Discovery and Overviews in Catalysis. Chin. J. Chem. 2020, 38 (11), 1360–1370. 10.1002/cjoc.202000027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine F.-G.; Stephan D. W. On the Concept of Frustrated Lewis Pairs. Philos. Trans. A Math Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 375 (2101), 20170004. 10.1098/rsta.2017.0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta M.; Caputo C. B. In Synthetic Inorganic Chemistry; Hamilton E. J. M., Ed.; Elsevier, 2021; Chapter 5, pp 169–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cicač -Hudi M.; Bender J.; Schlindwein S. H.; Bispinghoff M.; Nieger M.; Grützmacher H.; Gudat D. Direct Access to Inversely Polarized Phosphaalkenes from Elemental Phosphorus or Polyphosphides. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016 (5), 649–658. 10.1002/ejic.201501017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp C.; Zhou B.; Denning M. S.; Rees N. H.; Goicoechea J. M. Reactivity Studies of Group 15 Zintl Ions Towards Homoleptic Post-Transition Metal Organometallics: A ‘Bottom-Up’ Approach to Bimetallic Molecular Clusters. Dalton Trans 2010, 39 (2), 426–436. 10.1039/B911544G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J. A.; Pringle P. G. Monomeric Phosphinoboranes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 297–298, 77–90. 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Power P. P. Boron-Phosphorus Compounds and Multiple Bonding. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1990, 29 (5), 449–460. 10.1002/anie.199004491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini F.; Lyaskovskyy V.; Timmer B. J. J.; de Kanter F. J. J.; Lutz M.; Ehlers A. W.; Slootweg J. C.; Lammertsma K. Preorganized Frustrated Lewis Pairs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (1), 201–204. 10.1021/ja210214r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peuser I.; Neu R. C.; Zhao X.; Ulrich M.; Schirmer B.; Tannert J. A.; Kehr G.; Fröhlich R.; Grimme S.; Erker G.; Stephan D. W. CO2 and Formate Complexes of Phosphine/Borane Frustrated Lewis Pairs. Chem.—Eur. J. 2011, 17 (35), 9640–9650. 10.1002/chem.201100286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harhausen M.; Fröhlich R.; Kehr G.; Erker G. Reactions of Modified Intermolecular Frustrated P/B Lewis Pairs with Dihydrogen, Ethene, and Carbon Dioxide. Organometallics 2012, 31 (7), 2801–2809. 10.1021/om201076f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mömming C. M.; Otten E.; Kehr G.; Fröhlich R.; Grimme S.; Stephan D. W.; Erker G. Reversible Metal-Free Carbon Dioxide Binding by Frustrated Lewis Pairs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48 (36), 6643–6646. 10.1002/anie.200901636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szynkiewicz N.; Ordyszewska A.; Chojnacki J.; Grubba R. Diaminophosphinoboranes: Effective Reagents for Phosphinoboration of CO2. RSC Adv. 2019, 9 (48), 27749–27753. 10.1039/C9RA06638A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geier S. J.; Gilbert T. M.; Stephan D. W. Synthesis and Reactivity of the Phosphinoboranes R2PB(C6F5)2. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50 (1), 336–344. 10.1021/ic102003x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shegavi M. L.; Bose S. K. Recent Advances in the Catalytic Hydroboration of Carbonyl Compounds. Catalysis Science & Technology 2019, 9 (13), 3307–3336. 10.1039/C9CY00807A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S.; Provis-Evans C. B.; James A. P.; Webster R. L. Hydroboration of Aldehydes, Ketones and CO2 under Mild Conditions Mediated by Iron(iii) Salen Complexes. Dalton Trans 2021, 50 (31), 10696–10700. 10.1039/D1DT02092G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamang S. R.; Findlater M. Iron Catalyzed Hydroboration of Aldehydes and Ketones. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82 (23), 12857–12862. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b02020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee D.; Osseili H.; Spaniol T. P.; Okuda J. Alkali Metal Hydridotriphenylborates [(L)M][HBPh3] (M = Li, Na, K): Chemoselective Catalysts for Carbonyl and CO2 Hydroboration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (34), 10790–10793. 10.1021/jacs.6b06319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- P S.; Mandal S. K. From CO2 Activation to Catalytic Reduction: A Metal-Free Approach. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (39), 10571–10593. 10.1039/D0SC03528A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine F.-G.; Courtemanche M.-A.; Légaré M.-A.; Rochette É. Design Principles in Frustrated Lewis Pair Catalysis for the Functionalization of Carbon Dioxide and Heterocycles. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 334, 124–135. 10.1016/j.ccr.2016.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamang S. R.; Findlater M. Cobalt Catalysed Reduction of CO2 via Hydroboration. Dalton Trans 2018, 47 (25), 8199–8203. 10.1039/C8DT01985A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtemanche M.-A.; Légaré M.-A.; Maron L.; Fontaine F.-G. A Highly Active Phosphine–Borane Organocatalyst for the Reduction of CO2 to Methanol Using Hydroboranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (25), 9326–9329. 10.1021/ja404585p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Stephan D. W. Phosphine Catalyzed Reduction of CO2 with Boranes. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50 (53), 7007–7010. 10.1039/C4CC02103G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Lo S.-K.; Smith C.; Goicoechea J. M. Pincer-Supported Gallium Complexes for the Catalytic Hydroboration of Aldehydes, Ketones and Carbon Dioxide. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27 (69), 17379–17385. 10.1002/chem.202103009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sau S. C.; Bhattacharjee R.; Vardhanapu P. K.; Vijaykumar G.; Datta A.; Mandal S. K. Metal-Free Reduction of CO2 to Methoxyborane Under Ambient Conditions Through Borondiformate Formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55 (48), 15147–15151. 10.1002/anie.201609040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Neves Gomes C.; Blondiaux E.; Thuéry P.; Cantat T. Metal-Free Reduction of CO2 with Hydroboranes: Two Efficient Pathways at Play for the Reduction of CO2 to Methanol. Chem.—Eur. J. 2014, 20 (23), 7098–7106. 10.1002/chem.201400349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Xu M.; Song D. Organocatalysts with Carbon-Centered Activity for CO2 Reduction with Boranes. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51 (56), 11293–11296. 10.1039/C5CC04337A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A.; Antiñolo A.; Carrillo-Hermosilla F.; Fernández-Galán R. Ph2PCH2CH2B(C8H14) and Its Formaldehyde Adduct as Catalysts for the Reduction of CO2 with Hydroboranes. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59 (14), 9998–10012. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c01152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondiaux E.; Pouessel J.; Cantat T. Carbon Dioxide Reduction to Methylamines Under Metal-Free Conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53 (45), 12186–12190. 10.1002/anie.201407357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C.-H.; Holder A. M.; Hynes J. T.; Musgrave C. B. Roles of the Lewis Acid and Base in the Chemical Reduction of CO2 Catalyzed by Frustrated Lewis Pairs. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52 (17), 10062–10066. 10.1021/ic4013729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.