Abstract

Deaths due to synthetic opioids have increased at higher rates for Blacks and Hispanics than for Whites in the last decade. Meanwhile, Blacks and Hispanics experience lower opioid treatment rates and have less availability of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) via office-based buprenorphine in their counties compared to Whites. Racial/ethnic residential segregation is a recognized barrier to equal availability of MAT, but little is known about how such segregation is associated with opioid and substance use treatment availability over time and across Census regions and urban-rural lines. We combined data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services for 2009, 2014, and 2019 with the 5-year American Community Surveys of 2009, 2014, and 2019 to examine associations between residential segregation indices of dissimilarity and interaction and substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population, including those providing MAT, in US counties. Estimating county-level two-way fixed effects models and controlling for county-level covariates, we find modest evidence of associations. Despite mostly null findings, an increased likelihood of exposure of Whites to Blacks in a county is associated with fewer substance use treatment facilities per 100,000, particularly those providing MAT via buprenorphine and located in Northeastern and Midwestern counties. Also, a more unequal distribution of Hispanics is associated with fewer facilities per 100,000 providing MAT, and this association is strongest in Southern and Western counties. These associations are driven by recent years (2014–2019) when synthetic opioids became the leading cause of opioid mortality and Blacks and Hispanics began dying at faster rates than Whites. Mixed evidence, however, tempers conclusions for how residential segregation drives racial/ethnic disparities in MAT availability.

Keywords: Medication-assisted treatment, Opioid use disorder, Racial/ethnic health disparities, Residential segregation, Substance use treatment services

Highlights

-

•

Synthetic opioid mortality rates for Blacks and Hispanics increased faster than for Whites between 2010 and 2019.

-

•

Residential segregation is associated with racial/ethnic disparities in access to healthcare, including opioid treatment.

-

•

Counties where Whites were less likely to interact with Blacks had more substance use treatment facilities per 100,000.

-

•

Counties with a more unequal distribution of Hispanicshad fewer substance use treatment facilities per 100,000.

-

•

The above associations are regionally dependent and strongest between 2014 and 2019.

1. Introduction

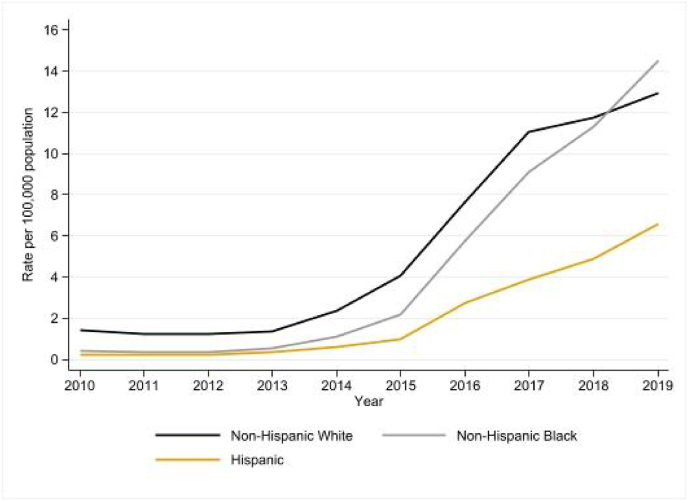

The US opioid epidemic has worsened in recent years, driving drug overdose mortality to record levels and having a greater impact on people of color. In 2019, 70,630 people died in the United States from a drug overdose, and over 70% of these deaths involved an opioid, an increase of over 6% from 2018 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). This increase is largely attributed to overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, which increased by over 15% from 2018 to 2019 (Mattson et al., 2021). Black and Hispanic individuals have been disproportionately impacted. Fig. 1 shows deaths per 100,000 population involving synthetic opioids other than methadone increased by 36- and 32-fold for non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals from 2010 to 2019, respectively, compared to a 9-fold increase for non-Hispanic White individuals (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Fueled by synthetic opioids and the arrival of COVID-19, US drug overdose deaths exceeded 93,000 in 2020 and 107,000 in 2021 (Ahmad et al., 2022), with rates higher for Blacks than Whites and growing faster for Hispanics than Whites in 2020 (Friedman & Hansen, 2022).

Fig. 1.

Synthetic opioid mortality rate per 100,000 (excluding methadone) by race/ethnicity, 2010-2019. Notes: Data from U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1999–2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2021. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999–2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html on Aug 17, 2022 5:10:44 p.m..

One explanation for these disparities is that barriers to treating opioid use disorder (OUD), including medication-assisted treatment (MAT) such as buprenorphine and methadone, differentiate along racial/ethnic lines. Prior research finds non-Hispanic White individuals have higher, although not statistically significant, odds than other racial and ethnic groups of initiating OUD treatment (Cantone et al., 2019). Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals who did not receive treatment for OUD in the 90 days leading up to an overdose are also less likely than their White counterparts to receive follow-up opioid treatment within 90 days following a nonfatal overdose (Kilaru et al., 2020). Blacks and Hispanics are also less likely than Whites to complete a single opioid treatment episode, although this is statistically significant in only three of the 42 largest US metropolitan statistical areas (Stahler & Mennis, 2018). Moreover, disparities between Whites and Blacks/Hispanics in accessing OUD treatment are found among subpopulations that may be in especially vulnerable situations. For example, Black Medicaid enrollees are less likely than White Medicaid enrollees to start MAT (Hollander et al., 2021); Black and Hispanic women with OUD during pregnancy are less likely than their White counterparts to receive MAT in the year before delivery (Schiff et al., 2020); and non-incarcerated Black individuals with criminal justice involvement are less likely than their White counterparts to have OUD treatment paid for by a court or by private insurance (Sanmartin et al., 2020).

Residential segregation is thought to cause racial/ethnic health disparities by creating differences in socioeconomic status or environmental conditions that affect health differently across racial/ethnic groups (Williams & Collins, 2001), and thus may be an underlying factor for the above racial/ethnic disparities in OUD treatment. Racially segregated communities have racial disparities in access to health care (Caldwell et al., 2017), a higher likelihood of residents reporting poor self-rated health (Subramanian et al., 2005), and tend to be more politically polarized and spend less on public goods (Trounstine, 2016). As a result, local opposition to siting health and social services such as substance use treatment programs in racially segregated communities could also limit access to substance use treatment for racial and ethnic minorities. Studies utilizing proxy (e.g. population shares) or formal measures of residential segregation have identified place-based disparities by race and ethnicity in receiving or having access to MAT. For example, Chang et al. (2022) found hospital-based OUD services, including MAT, are offered less in communities with a higher share of Black or Hispanic residents. Stein et al. (2018) found receipt of MAT across 14 states from 2002 to 2009 increased at a higher rate in counties with low poverty rates and low concentrations of Black or Hispanic residents than other county types. Similarly, Hansen et al. (2013) found that buprenorphine treatment rates were negatively associated with the percent of residents who are Black, Hispanic, and in poverty but vice versa for methadone treatment rates at the zip code level in New York City. Measuring the distribution instead of the composition of racial and ethnic groups within 3142 US counties, Goedel et al. (2020) found a decrease in the probability of a Black resident interacting with a White resident, or a White resident interacting with a Hispanic resident, was associated with more facilities per 100,000 population providing methadone, while a decrease in the probability of a White resident interacting with a Black or a Hispanic resident was associated with more facilities per capita providing buprenorphine.

These findings suggest place-based racial/ethnic inequality exists in having access to either agonist MAT, as buprenorphine is available for take-home through a waivered provider while methadone maintenance treatment is more stigmatized and burdensome, often requiring patients to be physically present, typically on a daily basis, at a federally licensed opioid treatment program (OTP) (Andraka-Christou, 2021). Such disparities may arise from a long history of racialized drug policies in the United States (Provine, 2011). OTPs were created in response to rising heroin use and crime in the 1970s and targeted to predominately Black urban communities, while the approval of buprenorphine under the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 aimed to expand MAT nationwide but targeted predominately White suburban communities disportionately affected by prescription opioid use (Andraka-Christou, 2021; Goedel et al., 2020; Hansen & Netherland, 2016).

While racial/ethnic disparities in office-based buprenorphine access are well-established (Goedel et al., 2020; Lagisetty et al., 2019), little is known about how residential segregation relates to opioid and other substance use treatment availability in treatment facilities over time and across Census regions and urban-rural lines. Understanding temporal heterogeneity of the association between residential segregation and substance use treatment availability is important due to growing racial/ethnic disparities in opioid-involved deaths and the evolving nature of the opioid epidemic, shifting from prescription-driven to heroin-driven to synthetic-driven in the last two decades (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). We thus explore whether the association between residential segregation and substance use treatment availability, including MAT, has strengthened over time as synthetic opioid death rates have increased at different rates along racial/ethnic lines. Residential segregation also varies across regions and over time. While staying relatively high and stable in some regions, such as in large Northeast and Midwest metropolitan areas (Williams & Collins, 2001), residential segregation has changed more rapidly in other areas. For example, Black residential segregation declined at a greater rate in the West from 1970 to 2009, and the regional differences in residential segregation are smaller in metropolitan areas of the West and South compared to those of the Midwest and Northeast (Iceland, Sharp, & Timberlake, 2013). We thus examine whether the association between residential segregation and substance use treatment availability vary across Census regions and metropolitan status.

We add to the literature on racial/ethnic disparities in opioid treatment by examining the relationship between residential segregation and the number of substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population within counties during the 2009–2019 period. Following Goedel et al. (2020), we use residential segregation measures of racial/ethnic evenness (dissimilarity index) and the likelihood of exposure between racial/ethnic groups (interaction index) within counties and estimate county-level two-way fixed effects regression models that control for time-invariant differences between counties and time-varying shocks affecting all counties within a state. We also explore whether this relationship differs by county metropolitan status, Census region, and period.

2. Methods

The University of Rhode Island Institutional Review Board and the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board confirmed the study is not human subject research and exempt from institutional review board review as the data are publicly available and not identifiable.

2.1. Data and study sample

Our primary data sources were the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) for 2009, 2014, and 2019 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010, 2015, 2020) and the 5-year American Community Surveys (ACS) of 2009, 2014, and 2019 (Manson et al., 2021). The N-SSATS directory is a near-census of substance use treatment facilities in the United States populated by the previous year's N-SSATS survey. Thus, the 2020 N-SSATS directory corresponds to facilities in the 2019 N-SSATS survey. The N-SSATS directory includes each facility's address and a list of services provided by the facility, including whether the facility provides MAT via methadone and/or buprenorphine. Response rates were 91.4% in 2019, 93.7% in 2014, and 93.4% in 2009. Ideally, we would use as many years of the N-SSATS directory as possible, but we are limited by the availability of census tract-level race and ethnicity population estimates from the 5-year ACS estimates in 2009, 2014, and 2019. Population estimates from the 3-year or single-year ACS reduces precision of the population estimates, particularly for tracts with small racial and ethnic minority populations. Merging the N-SSATS data with the ACS data yields a balanced panel of 3086 US counties over three years (2009, 2014, and 2019).

2.2. Outcomes

We calculated the number of substance use treatment facilities in a county and year from the 2010, 2015, and 2020 N-SSATS directory (populated by the 2009, 2014, and 2019 N-SSATS survey, respectively) provided by SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010, 2015, 2020). Unlike data from SAMSHA's OTP and buprenorphine locators used in Goedel et al. (2020), the N-SSATS directory data are available over time and that allows for panel analysis. Facilities surveyed in N-SSATS include both public and private substance use treatment facilities. Public facilities are operated by federal, state, county, or local governments while private facilities are operated by either nonprofit or for-profit organizations. Federally certified OTPs where methadone is provided are also included in N-SSATS. Solo practitioners, such as primary care providers, who prescribe buprenorphine in office-based settings are not included. In March 2022, we converted facility addresses to latitude and longitude coordinates to identify counties where the facilities are located using Google Maps Geocoding API and calculated the total number of substance use/mental health facilities (N-SSATS codes: SA, MHSAF, SUMH, and MHSA) and number of facilities that provide MAT via methadone (N-SSATS codes: DM, MM, MU, and MMW) or buprenorphine (N-SSATS code: BU) in a county in a given year. We then calculated the number of these facilities per 100,000 population in a county-year using population estimates from the 5-year ACS (Manson et al., 2021).

2.3. Independent variables

The independent variables of interest are measures of racial/ethnic segregation of non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic populations. We used two common measures of racial/ethnic segregation: the dissimilarity index and the interaction index (Massey & Denton, 1988). The dissimilarity index is a measure of population evenness that can be interpreted as the percent of the minority population that would need to move to have a uniform distribution of county population by race/ethnicity. The dissimilarity index ranges from 0 (no segregation) to 1.0 (maximum segregation). For example, a Black dissimilarity index of 0.6 means that 60% of Black residents would have to move to another neighborhood (census tract) to eliminate segregation across all neighborhoods in the county. The interaction index measures exposure and can be thought of as measuring the likelihood one race/ethnicity interacts with another. This index ranges from 0 to 1.0, with lower values indicating higher residential segregation. For example, a Black-White interaction index of 0.1 in a county means that the ratio of a minority Black resident interacting via sharing a residential area with a majority White resident to the number of Black residents in the county is 10%.

We calculated both racial/ethnic residential segregation measures using population estimates from the 2009, 2014, and 2019 5-year ACS. The dissimilarity index is calculated as:

Where is the non-Hispanic White population in census tract in county c in year , is the population of minority group in census tract in county in year , is the non-Hispanic White population in county in year , and is the minority population in county in year . We calculated the dissimilarity index for non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic residents.

The interaction index is calculated as:

where is the total population of group j in county in year and is the population of group in census tract in county in year . is the total population of tract i in county in year and is the population of group in census tract in county c in year t. , for example, is the interaction index between White and non-Hispanic Black residents in county in year . Unlike measures of composition, residential segregation indices capture how racial and ethnic groups are distributed within a geography. Fig. 2 shows how counties with equal measures of racial composition can have different measures of the residential segregation indices. The upper panel shows two counties with an equal share of two groups but different dissimilarity indices, and the lower panel shows counties with an equal population share but different interaction indices. Appendix Figure A1 shows a change in one index holding the other constant. The upper panel demonstrates a situation in which the probability of a White person interacting with a Black person increases but the dissimilarity for two racial groups stays the same. The lower panel demonstrates a situation in which the interaction between Whites and Blacks is held constant but the dissimilarity for two racial groups increases. Finally, because the interaction index depends on the distribution and the population share of the population groups, the probability of a Black or Hispanic resident interacting with a White resident is not always the same as a White resident interacting with a Black or Hispanic resident.

Fig. 2.

Example of racial and ethnic segregation indices.

2.4. Empirical strategy and statistical analysis

We used a two-way fixed effects strategy to estimate the association between racial/ethnic residential segregation measures and substance use treatment facilities per capita in counties. We estimate the following regression:

| (Equation 1) |

Where is the number of facilities per capita in county in year . We define facilities as the total number of substance use treatment facilities in the N-SSATS directory in a given year or the total number of facilities that report providing MAT via methadone and/or buprenorphine in a given year. We also examine MAT-providing facilities separately by whether they provide MAT via methadone or buprenorphine. and represent the dissimilarity indices for Black and Hispanic residents in county in year , respectively. Similarly, , , , and represent the interaction indices for White with Black (WB), Black with White (BW), White with Hispanic (WH), and Hispanic with White (HW) groups in county in year , respectively. County fixed effects, , account for time-invariant differences between counties that may be correlated with the number of substance use treatment facilities and distribution of population groups within a county. State-by-year fixed effects, , control for time-varying shocks that affect all counties within a state such as state-specific economic conditions, state-specific drug control policies such as prescription drug monitoring programs and attitudes related to substance use that may affect the market for substance use treatment. Thus, the associations between the racial/ethnic segregation indices and substance use treatment facilities per capita are identified from changes within a county over time. is a vector of time-varying county-level controls including the race-specific opioid-mortality rate over the previous five years from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's restricted-access mortality files (National Center for Health Statistics, 2021), natural log of personal income per capita from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, and median age from the ACS (Manson et al., 2021). Since the use of state-by-year fixed effects may provide more conservative estimates, we also ran regressions using county fixed effects and year fixed effects, controlling for Medicaid expansion status and state-level substance use policies, including mandatory prescription drug monitoring programs, naloxone access, good samaritan laws, “pill mill” laws, and prescription limit laws. These estimates are generally similar to those from our main specification with the exception of larger effects for White-Hispanic interaction (see Appendix Table A1).

All regression models were weighted using the county population and standard errors were clustered at the county level. Because opioid mortality rates have differed across racial and ethnic lines for different age groups in metropolitan areas (Allen, Nolan, Kunins, & Paone, 2019; Lippold et al., 2019) and non-urban residents may pay more attention to overdose deaths than urban residents (Gollust & Haselswerdt, 2021), possibly affecting substance use treatment availability, separate regression models were estimated for metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties using definitions from the 2013 United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2020). Regression models were also estimated separately for each Census region since racial/ethnic residential segregation has been historically higher and stable in large Northeast and Midwest metropolitan areas compared to newer metropolitan areas in the West and Southwest (Williams & Collins, 2001) and large concentrations of Blacks and Hispanics live in Southern and Southwestern rural areas, respectively, which have been subjected to a history of racial/ethnic and economic oppression (Caldwell et al., 2017; Lichter et al., 2012). Separate regression models were also estimated for two time periods in our dataset that match distinct waves of the opioid overdose epidemic: 2009–2014, or during the rise of heroin overdose deaths, and 2014–2019, or during the rise in synthetic opioid overdose deaths. Robustness tests were performed to determine whether a single state influenced the main results and whether estimates were sensitive to the inclusion of race/ethnicity population shares. All statistical analysis was performed in Stata version 17 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

Table 1 shows the summary statistics. There are roughly four substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population in a county, one of which provides methadone or buprenorphine as a form of MAT. The average county has a moderate level of racial and ethnicity minority dissimilarity, with about 53% of Black residents and 42% of Hispanic residents needing to move to create a uniform distribution of the population. The average likelihood of White residents interacting with Black residents is 8%, White residents interacting with Hispanic residents is 13%, Black residents interacting with White residents is 50%, and Hispanic residents interacting with White residents is 55%.

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

| Outcomes | |

| Substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 | 3.88 |

| (2.96) | |

| MAT-providing facilities per 100,000 | 1.24 |

| (1.44) | |

| Methadone-only MAT facilities per 100,000 | 0.394 |

| (0.513) | |

| Buprenorphine-only MAT facilities per 100,000 | 1.10 |

| (1.38) | |

| Racial/Ethnic segregation indices | |

| 0.525 | |

| (0.140) | |

| 0.420 | |

| (0.121) | |

| 0.079 | |

| (0.081) | |

| 0.129 | |

| (0.127) | |

| 0.496 | |

| (0.247) | |

| 0.547 | |

| (0.237) | |

| Controls | |

| Opioid mortality rate, White | 59.38 |

| (45.08) | |

| Opioid mortality rate, Black | 39.63 |

| (117.20) | |

| Opioid mortality rate, Hispanic | 23.54 |

| (106.68) | |

| Ln(personal income per capita) | 10.72 |

| (0.298) | |

| Median age | 37.58 |

| (4.21) | |

Notes: Number of observations: 9258. Sample means weighted by county population. Standard deviations in parentheses. Outcome data from the 2010, 2015, and 2020 N-SSATS directories. Racial/ethnic segregation indices and median age calculated using the 5-year 2009, 2014, and 2019 American Community Surveys. County mortality rates calculated from the restricted-access National Center for Health Statistics mortality data. County income per capita from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Table 2 shows the associations between the racial/ethnic segregation measures and the number of substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population. For all substance use treatment facilities in columns 1 and 2, all racial/ethnic segregation indices are negative, but only the White-Black interaction index is statistically significant at the 5% level. The estimate in column 2 suggests a 1 percentage point increase in the probability of a White person interacting with a Black person is associated with about 0.07 fewer substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population, a 2% decrease relative to the sample mean. Columns 3 and 4 present estimates for facilities providing MAT with methadone or buprenorphine per 100,000 population. These estimates show a statistically significant decrease in MAT-providing facilities as the indices for Hispanic dissimilarity and White-Black interaction increase. Using the estimates in column 4, a 1 percentage point increase in Hispanic dissimilarity is associated with 0.006 fewer MAT facilities per 100,000 population and a 1 percentage point increase in the likelihood a White person interacts with a Black person is associated with 0.05 fewer MAT facilities per 100,000 population. These effects are 0.5% and 4% of the sample mean, respectively.

Table 2.

Association between racial segregation indices and substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population.

| All facilities |

MAT facilities |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| −0.407 | −0.424 | −0.255 | −0.271 | |

| (0.372) | (0.372) | (0.218) | (0.219) | |

| −0.200 | −0.266 | −0.532* | −0.572* | |

| (0.415) | (0.412) | (0.302) | (0.302) | |

| −6.748** | −6.859** | −3.166 | −4.682** | |

| (2.955) | (3.044) | (2.308) | (2.308) | |

| 0.337 | 0.369 | 0.198 | 0.175 | |

| (0.494) | (0.494) | (0.270) | (0.268) | |

| −2.749 | −3.343 | −2.264 | −3.516 | |

| (3.353) | (3.213) | (2.360) | (2.285) | |

| −0.214 | −0.217 | −0.277 | −0.135 | |

| (0.787) | (0.777) | (0.658) | (0.639) | |

| N | 9258 | 9258 | 9258 | 9258 |

| 0.841 | 0.842 | 0.747 | 0.750 | |

| County fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State-year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County controls | No | Yes | No | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors clustered at county level. Outcome data are the number of substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population calculated from the 2010, 2015, and 2020 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services directories. Racial segregation indices and population shares calculated from the 5-year 2009, 2014, and 2019 American Community Surveys. Regression controls include the natural log of county income per capita, county race-specific opioid mortality rates, county median age, county fixed effects and state-year fixed effects. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table 3 presents the estimates for facilities that provide methadone in columns 1 and 2 and facilities that provide buprenorphine in columns 3 and 4. We do not find any statistically significant relationships between the racial and ethnic segregation indices and facilities that provide methadone. Among facilities providing buprenorphine, a 1 percentage point increase in the White-Black interaction index is associated with 0.05 fewer buprenorphine-only facilities per 100,000 population. These results suggest the association between White-Black interaction and MAT facilities found in Table 3 is driven by facilities that provide buprenorphine.

Table 3.

Association between racial segregation indices and MAT-providing facilities per 100,000 population by MAT offered.

| Methadone |

Buprenorphine |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| −0.015 | −0.020 | −0.253 | −0.266 | |

| (0.068) | (0.068) | (0.215) | (0.215) | |

| 0.017 | 0.002 | −0.454 | −0.483 | |

| (0.076) | (0.077) | (0.304) | (0.304) | |

| −0.311 | −0.553 | −3.268 | −4.799** | |

| (0.649) | (0.651) | (2.264) | (2.265) | |

| −0.031 | −0.035 | 0.303 | 0.275 | |

| (0.062) | (0.062) | (0.272) | (0.269) | |

| −0.501 | −0.661 | −0.969 | −2.185 | |

| (0.527) | (0.581) | (2.440) | (2.395) | |

| 0.023 | 0.039 | −0.109 | 0.041 | |

| (0.173) | (0.163) | (0.671) | (0.663) | |

| N | 9258 | 9258 | 9258 | 9258 |

| 0.835 | 0.836 | 0.730 | 0.732 | |

| County fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State-year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County controls | No | Yes | No | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors clustered at county level. Outcome data are the number of substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population calculated from the 2010, 2015, and 2020 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services directories. Racial segregation indices and population shares calculated from the 5-year 2009, 2014, and 2019 American Community Surveys. Regression controls include the natural log of county income per capita, county race-specific opioid mortality rates, county median age, county fixed effects and state-year fixed effects. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

3.1. Heterogeneity

To examine differences by urbanicity, we split the sample by metropolitan status using the 2013 USDA Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. Table 4 shows the associations between the racial/ethnic segregation measures and facilities per 100,000 population for metropolitan counties in columns 1–4 and non-metropolitan counties in columns 5–8. Splitting the sample by urbanicity reduces the precision of estimates, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions about differences in residential segregation and the availability of substance use treatment facilities between metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties. The major difference by urbanicity is the large, negative statistically significant association between White-Hispanic interaction for facilities in non-metropolitan counties. A 1 percentage point increase in White-Hispanic interaction is associated with about 0.2 fewer facilities per 100,000 in non-metropolitan counties, an effect that is 3% of the non-metropolitan county mean.

Table 4.

Association between racial segregation indices and substance use facilities per 100,000 population by metropolitan status.

| Metropolitan counties |

Non-metropolitan counties |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

MAT-providing |

All |

MAT-providing |

|||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| −0.388 | −0.470 | −0.513 | −0.586 | −0.701 | −0.678 | −0.077 | −0.071 | |

| (0.734) | (0.738) | (0.413) | (0.416) | (0.461) | (0.460) | (0.274) | (0.274) | |

| −0.495 | −0.766 | −0.161 | −0.310 | −0.186 | −0.158 | −0.507 | −0.513 | |

| (0.711) | (0.697) | (0.429) | (0.427) | (0.503) | (0.500) | (0.380) | (0.378) | |

| −5.213 | −5.917 | −1.393 | −2.670 | −5.243 | −5.037 | −3.359 | −3.968 | |

| (3.586) | (3.650) | (3.167) | (3.088) | (6.734) | (6.755) | (3.866) | (3.861) | |

| −0.520 | −0.482 | 0.486 | 0.341 | 0.548 | 0.558 | −0.026 | −0.005 | |

| (1.286) | (1.250) | (0.659) | (0.620) | (0.559) | (0.564) | (0.309) | (0.310) | |

| 1.162 | 0.191 | −1.348 | −2.403 | −16.81*** | −15.67*** | −1.717 | −2.963 | |

| (4.111) | (4.067) | (3.023) | (3.001) | (5.975) | (6.006) | (3.060) | (3.086) | |

| −0.012 | −0.214 | 0.889 | 0.951 | −0.484 | −0.429 | −1.045 | −0.922 | |

| (1.460) | (1.420) | (1.178) | (1.087) | (0.933) | (0.925) | (0.727) | (0.722) | |

| N | 3384 | 3384 | 3384 | 3384 | 5868 | 5868 | 5868 | 5868 |

| 0.881 | 0.882 | 0.834 | 0.839 | 0.799 | 0.799 | 0.633 | 0.634 | |

| County fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State-year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County controls | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors clustered at county level. Outcome data are the number of substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population calculated from the 2010, 2015, and 2020 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services directories. Racial segregation indices calculated from the 5-year 2009, 2014, and 2019 American Community Surveys. All regressions include controls for the natural log of county income per capita, county race-specific opioid mortality rates, county median age, county fixed effects and state-year fixed effects. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

We also explored whether these associations differ by the four Census regions in Table 5. For all facilities, the estimate for the White-Black interaction index is largest in Northeastern and Western counties, but only statistically significant in Southern counties. The Black dissimilarity index is also negative and statistically significant in Southern counties, suggesting a 1 percentage point increase in the Black dissimilarity index is associated with about 0.1 fewer facilities per 100,000 population in a county. We also find negative statistically significant estimates for the White-Hispanic interaction index and Hispanic-White interaction index in Western counties. These estimates suggest a 1 percentage point increase in the respective index decreases facilities per 100,000 population by about 0.2 and 0.1, respectively. For MAT facilities, there is a strong negative association between the White-Black and White-Hispanic interaction indices in Northeastern counties. Increased Hispanic dissimilarity is negatively associated with MAT-providing facilities in Southern counties and Western counties. In Midwest counties, increased White-Black interaction is negatively associated with MAT-providing facilities, while Hispanic-White interaction is positively associated with MAT-providing facilities. Increased Hispanic dissimilarity and White-Hispanic interaction are negatively associated with MAT-providing facilities in Western counties. Overall, these results show substantial heterogeneity across Census regions in how racial and ethnic segregation is related to substance use treatment availability.

Table 5.

Association between racial segregation indices and substance use facilities per 100,000 population by Census Region.

| All facilities |

MAT-providing facilities |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast(1) | South (2) | Midwest (3) | West (4) | Northeast (5) | South (6) | Midwest (7) | West (8) | |

| 1.325 | −0.964* | −0.202 | −0.249 | −1.015 | −0.133 | −0.213 | 0.360 | |

| (1.683) | (0.542) | (0.547) | (0.992) | (1.184) | (0.343) | (0.295) | (0.578) | |

| 0.630 | −0.736 | 0.433 | −1.707 | 0.606 | −0.834** | −0.027 | −2.940* | |

| (1.998) | (0.492) | (0.700) | (3.057) | (1.510) | (0.399) | (0.423) | (1.600) | |

| −19.71 | −5.875* | −5.180 | −11.83 | −22.26* | 0.249 | −16.85*** | −17.86 | |

| (16.25) | (3.169) | (9.610) | (33.67) | (13.19) | (2.160) | (5.893) | (23.28) | |

| 3.533 | 0.707 | 0.768 | −0.885 | 3.792 | −0.231 | −0.105 | 0.206 | |

| (3.583) | (0.828) | (0.575) | (1.321) | (2.733) | (0.515) | (0.324) | (0.657) | |

| −9.018 | −1.647 | −0.372 | −19.03** | −12.72** | −0.054 | 8.661 | −12.90** | |

| (5.843) | (3.925) | (10.53) | (8.945) | (4.936) | (2.447) | (7.168) | (5.310) | |

| −0.184 | −0.295 | 1.768 | −8.990** | −3.039 | −0.795 | 2.256** | 0.603 | |

| (3.717) | (0.943) | (1.497) | (4.532) | (3.327) | (0.766) | (0.944) | (2.112) | |

| N | 651 | 4110 | 3162 | 1335 | 651 | 4110 | 3162 | 1335 |

| 0.910 | 0.840 | 0.781 | 0.380 | 0.847 | 0.777 | 0.607 | 0.666 | |

| County fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State-year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors clustered at county level. Outcome data are the number of substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population calculated from the 2010, 2015, and 2020 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services directories. Racial segregation indices calculated from the 5-year 2009, 2014, and 2019 American Community Surveys. All regressions include controls for the natural log of county income per capita, county race-specific opioid mortality rates, county median age, county fixed effects and state-year fixed effects. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Finally, we explored heterogeneity by the two time periods in our study, 2009–2014 and 2014–2019. These periods capture two waves of rising opioid mortality, the first due to heroin which began around 2010 and the second due to synthetic opioids which began around 2013. The estimates in Table 6 show our main results are driven by the second period. The estimated effects for 2009–2014 are not statistically significant and, in some cases, different in sign from the main results. While there is not a statistically significant association between the Black dissimilarity index and substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population in the full sample period, we find a statistically significant negative association between increased dissimilarity of Black residents and facilities per 100,000 population in the 2014–2019 period.

Table 6.

Association between racial segregation indices and substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population by period.

| All facilities |

MAT facilities |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009–2014 |

2014–2019 |

2009–2014 |

2014–2019 |

|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| 0.349 | −1.221** | 0.062 | −0.068 | |

| (0.439) | (0.593) | (0.214) | (0.407) | |

| −0.090 | 0.300 | −0.115 | −0.632 | |

| (0.517) | (0.590) | (0.272) | (0.498) | |

| 0.325 | −9.532* | 0.101 | −8.122** | |

| (4.080) | (5.396) | (2.212) | (3.754) | |

| −0.186 | 1.449 | −0.172 | 0.707 | |

| (0.506) | (1.210) | (0.244) | (0.706) | |

| −5.285 | −0.427 | −1.846 | −4.548 | |

| (4.633) | (4.681) | (2.672) | (3.780) | |

| 0.610 | −0.484 | −0.423 | 0.854 | |

| (1.071) | (1.120) | (0.573) | (1.018) | |

| N | 6172 | 6172 | 6172 | 6172 |

| 0.896 | 0.899 | 0.836 | 0.816 | |

| County fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State-year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors clustered at county level. Outcome data are the number of substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population calculated from the 2010, 2015, and 2020 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services directories. Racial segregation indices and population shares calculated from the 5-year 2009, 2014, and 2019 American Community Surveys. All regressions include controls for the natural log of county income per capita, county race-specific opioid mortality rates, county median age, county fixed effects and state-year fixed effects. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

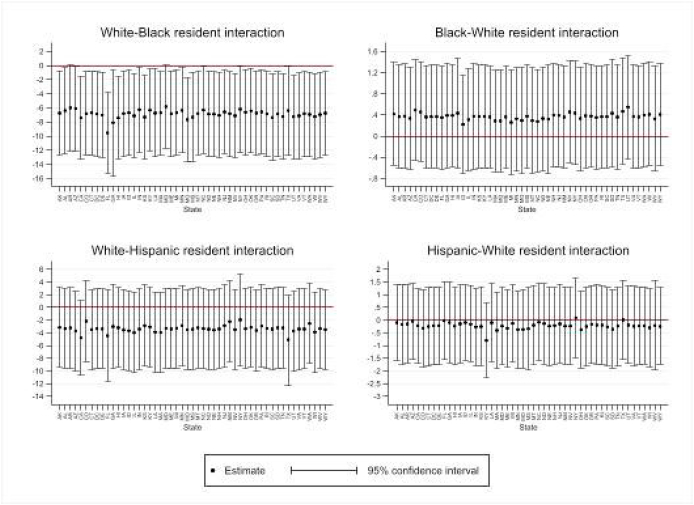

3.2. Robustness tests

We examined whether the results were driven by a single state by sequentially dropping one state and re-estimating our regressions. Appendix Figures A2 and A3 summarize the estimates from this exercise for all facilities and Appendix Figures A4 and A5 summarize the estimates for MAT-providing facilities. This exercise shows our results are not driven by counties in any single state. We tested the robustness of our estimates by controlling for the share of the population that is Black and Hispanic since the segregation indices only capture the evenness of racial composition and likelihood of interaction between population groups. Appendix Table A2 shows the main results in columns 1 and 3 and results controlling for population shares in columns 2 and 4. Controlling for population shares reduces precision of the White-Black interaction effect, although the magnitude is similar, but the Hispanic dissimilarity index remains statistically significant.

Finally, recent developments in the literature on two-way fixed effects estimates show that estimates may be biased in the presence of staggered treatment timing and heterogeneous treatment effects (de Chaisemartin & D’Haultfœuille, 2022; Goodman-Bacon, 2021; Imai & Kim, 2021). There is no strict treatment and control group in our setup, however, we attempt to address these concerns by excluding counties that have a segregation index that increases (decreases) in one period and decreases (increases) the next (“switchers”). Only a handful of counties meet this criteria jointly across all segregation indices, thus we consider each segregation index separately, apply the exclusion criteria, and re-estimate equation (1), but only including the specific segregation index. We then compare these estimates from estimating the same equation but using the full sample (see Appendix Table A3). Overall, the estimates excluding switchers are similar to those using the full sample. Finally, our separate analyses by period only uses two time periods (2009–2014 or 2014–2019), and we find our main results are similar to those from the 2014–2019 period.

4. Discussion

Opioid overdose rates have increased faster for Blacks and Hispanics than Whites (Friedman & Hansen, 2022) due in part to larger increases in the rate of opioid deaths involving synthetic opioids during the last decade (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Evidence-based MAT, including methadone and buprenorphine, saves lives affected by OUD (Volkow et al., 2014; Wakeman et al., 2020), but takeup is low. Only about 20% of the US population in need of substance use treatment received any treatment in 2019 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020), and Blacks and Hispanics have lower odds of initiating and completing OUD treatment than Whites (Cantone et al., 2019; Kilaru et al., 2020; Stahler & Mennis, 2018). These disparities in treatment are likely one factor driving increased opioid mortality among Blacks and Hispanics.

Residential segregation has long been identified as a primary factor in creating racial/ethnic disparities in health and access to care (Caldwell et al., 2017; Subramanian et al., 2005; Williams & Collins, 2001), and this relationship extends to OUD treatment (Goedel et al., 2020; Hansen et al., 2013; Stein et al., 2018). We examined whether residential segregation, proxied by racial and ethnic dissimilarity and interaction indices, were associated with the number of substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 in counties using data from the 2010, 2015, and 2020 N-SSATS directories (corresponding to the 2009, 2014, and 2019 surveys, respectively) and the 2009, 2014, and 2019 5-year ACS. Most hypothesis tests yielded null results; however, consistent with prior estimates (Goedel et al., 2020), we found substance use treatment facilities providing MAT, particularly buprenorphine, per 100,000 population were higher in counties where White residents were less likely to interact with Black residents. Notably, these associations were stronger in the 2014–2019 period when mortality from synthetic opioids became dominant, and it is particularly concerning since Black and Hispanic people have higher magnitudes of increases in deaths from synthetic opioids other than methadone, suggesting access to treatment may be a factor. Analyzing Census regions separately indicated that White-Black disparities in MAT access, driven by buprenorphine, were stronger in the Northeast and the Midwest. This suggests that growth in buprenorphine waivers in substance use treatment facilities (Dick et al., 2015) in these regions may have mostly benefited communities with greater shares of White residents while communities with greater shares of Black residents of these regions continue to rely on methadone treatment and remain subjected to its associated stigmatization and restrictions (Andraka-Christou, 2021). We also found that counties with more unevenly distributed Hispanic populations had fewer facilities providing MAT per 100,000 population. This effect was concentrated in the South and West Census regions, but White-Hispanic interaction was also negatively associated with MAT-providing facilities in the Northeast and Hispanic-White interaction was positively associated with MAT-providing facilities in the Midwest.

From 2014 to 2019, both dissimilarity indices decreased by about 0.02, the White-Black interaction index increased by 0.006, and the White-Hispanic interaction index increased by 0.024. This suggests counties became slightly more racially diverse and White residents became more likely to interact with Black and Hispanic residents, on average. Using these changes and the estimates in Table 2, the average county would have, per 100,000 population, 0.04 fewer substance use treatment facilities (0.006 (−6.859)) and about 0.02 fewer facilities ([(−0.02) (−0.575)] + [0.006 (−4.682)]) that provide methadone or buprenorphine in 2019. While these average changes are relatively small, about 5% and 1.2% of the sample means, respectively, some counties experienced large changes in these measures. For example, 381 counties (12% of the sample) had an increase between 0.1 and 0.8 in the Hispanic dissimilarity index and 510 counties (15% of the sample) had an increase between 0.01 and 0.16 in the White-Black interaction index.

White-Hispanic interaction did not show a statistically significant association with buprenorphine availability in substance use treatment facilities in the full sample, nor did Black-White interaction in the model with facilities that only provide methadone during the study period. This may be an important distinction from Goedel et al. (2020) who analyzed office-based buprenorphine providers and OTPs, because prior estimates could have been driven by county- or time-specific factors that were unaccounted for in a cross-sectional framework. When substance use treatment facilities were examined over the 2009–2019 period, the associations suggest the main evidence for disparities concerns greater buprenorphine provision per capita when White-Black interaction becomes less likely. Given the barriers to methadone maintenance treatment and the stigmatization of methadone patients (Andraka-Christou, 2021; Woo et al., 2017), expanding buprenorphine provision could help close the treatment gap and reduce opioid overdose mortality, but such expansion could exacerbate racial/ethnic inequities if buprenorphine is not made equally available to Black individuals and other people of color.

Despite research showing OUD impacts diverse races and ethnicities in metropolitan areas (Allen et al., 2019; Lippold et al., 2019) and treatment completion rates differ by race and ethnicity in some metropolitan areas (Stahler & Mennis, 2018), we did not find that racial/ethnic disparities in substance use treatment availability were markedly different across metropolitan classifications during the study period. The only statistically significant finding by urbanicity was the association between White-Hispanic interaction and substance use treatment facilities in non-metropolitan counties. Our study found that when the probability of a White resident interacting with a Hispanic resident increases, substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 decreases in non-metropolitan counties, although this association did not hold for facilities providing MAT.

Although our study did not detect many statistically significant associations, some of our results provide potentially conflicting evidence on the association between racial/ethnic segregation and the availability of substance use treatment facilities. More Hispanic segregation, measured by the dissimilarity index, was associated with fewer MAT-providing facilities. However, less White-Black segregation, measured by an increase in the White-Black interaction index, was also associated with fewer facilities. The White-Black interaction index is a measure of the likelihood Whites interact with Blacks, but does not provide information on potential interactions beyond the likelihood increasing or decreasing. One interpretation of this finding is that increased exposure of Whites to Blacks may increase racial animus and systemic racism involved in the location of substance use treatment facilities.

US drug policy has been historically racialized (Provine, 2011). For example, research shows a marked difference between legislation aimed at the crack cocaine scare of the 1980s and that which targeted the opioid crisis, with the former taking a more punitive stance, affecting mostly Blacks, and the latter being more prevention- and treatment-oriented, affecting mostly Whites (Kim, Morgan, & Nyhan, 2020). More systematic investigation is needed into whether treatment expansion and related opioid response efforts are racially biased in their placement, design, and impact. For example, experts have called for racial impact statements in which lawmakers consider and evaluate the impact of criminal justice reform efforts on racial disparities before voting on legislation (Hansen & Netherland, 2016; James & Jordan, 2018). A similar approach could be taken with the adoption and implementation of opioid and substance use treatment policies and related response efforts. In addition, prior research highlights the need for culturally-tailored interventions to address “sub-epidemics” among diverse populations within the larger opioid epidemic, as some people of color face greater cultural and structural barriers to substance use treatment than others (Lippold & Ali, 2020). How culturally-tailored interventions should be designed, and how effective they are in addressing such sub-epidemics, remains largely unknown. Policymakers have also been advised to expand buprenorphine access for people of color by opting into Medicaid expansion, increasing grant funding for buprenorphine expansion, offering incentives for buprenorphine prescribers working in communities of color, and covering the cost of ancillary services to improve buprenorphine retention rates for people of color (Andraka-Christou, 2021).

4.1. Limitations and future research

The distribution of races and ethnicities within a geography and availability of substance use treatment are endogenous. While we control for factors likely to affect the distribution of county residents and availability of substance use treatment facilities in a county, this study only provides correlational evidence between increased racial and ethnic segregation and the availability of substance use treatment facilities. The lack of precise county-level population estimates by race and ethnicity limited our analysis to three years, although this period spans the large increase in opioid mortality and introduction of fentanyl as a major contributor to opioid mortality. Data from the 2009 N-SSATS directory does not include information on the provision of naltrexone, an antagonist therapy also approved by the FDA to treat OUD, however data from the 2014–2019 shows increased Hispanic dissimilarity and increased White-Black interaction is associated with fewer naltrexone-providing facilities (see Appendix Table A4). The N-SSATS data also do not include all office-based providers of buprenorphine such as providers who work in private practice settings and not in substance use treatment facilities. SAMHSA's Buprenorphine Treatment Practitioner Locator provides such data but does not indicate when practitioners began providing, thus preventing longitudinal analysis. N-SSATS data also do not contain information on the quality or affordability of substance use treatment and MAT services, so our results may understate the association between racial and ethnic segregation and access to substance use treatment if areas with more racial/ethnic residential segregation have lower quality or more expensive services. According the 2020 N-SSATS report (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021), about 51 percent of facilities reported MAT clients' prescriptions originated or were prescribed by another entity, thus our results may overstate the relationship between racial segregation and access to MAT more generally. Finally, this study examined only two indices of racial/ethnic residential segregation, dissimilarity and interaction. Previous work points out that some residential segregation indices may be more relevant than others for health disparities research (Subramanian et al., 2005). Other indices of residential segregation could be explored in future work on racial/ethnic disparities in access to substance use treatment services.

Future research also has an opportunity to examine whether the recent exemption of required training for clinicians who prescribe buprenorphine to 30 or fewer patients (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2022) has addressed racial/ethnic disparities related to buprenorphine availability. Future work should also examine disparities involving American Indian or Alaskan Native individuals who are dying at the highest rate of all races and ethnicities from opioid overdose (Friedman & Hansen, 2022). Future research could also build on recent efforts to investigate “intersecting conditions” (Kong et al., 2022) that may affect or moderate racial/ethnic disparities in accessing buprenorphine treatment.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Michael DiNardi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. William L. Swann: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Serena Y. Kim: Data curation, Software, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Contributor Information

Michael DiNardi, Email: michael_dinardi@uri.edu.

William L. Swann, Email: william.swann@ucdenver.edu.

Serena Y. Kim, Email: serena.kim@ucdenver.edu.

Appendix.

Appendix Fig. A1.

Example of changing one index, holding the other constant

Appendix Fig. A2.

Robustness to dropping a single state, all substance use treatment facilities, dissimilarity indices

Note: Each panel shows the coefficient estimate and 95% confidence interval from estimating equation (1) and sequentially dropping each state from the sample.

Appendix Fig. A3.

Robustness to dropping a single state, all substance use treatment facilities, interaction indices

Note: Each panel shows the coefficient estimate and 95% confidence interval from estimating equation (1) and sequentially dropping each state from the sample.

Appendix Fig. A4.

Robustness to dropping a single state, MAT-providing facilities, dissimilarity indices

Note: Each panel shows the coefficient estimate and 95% confidence interval from estimating equation (1) and sequentially dropping each state from the sample.

Appendix Fig. A5.

Robustness to dropping a single state, MAT-providing facilities, interaction indices

Note: Each panel shows the coefficient estimate and 95% confidence interval from estimating equation (1) and sequentially dropping each state from the sample.

Table A1.

Association between racial segregation indices and substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population, county fixed effects and year fixed effects

| All facilities | MAT facilities | |

|---|---|---|

| −0.301 | −0.212 | |

| (0.384) | (0.218) | |

| −0.572 | −0.600** | |

| (0.434) | (0.298) | |

| −5.931* | −6.060*** | |

| (3.238) | (2.268) | |

| 0.0866 | 0.0390 | |

| (0.491) | (0.272) | |

| −11.05*** | −4.154** | |

| (2.595) | (1.843) | |

| −0.769 | −0.338 | |

| (0.886) | (0.613) | |

| N | 9261 | 9261 |

| 0.814 | 0.720 | |

| County fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| County and state controls | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors clustered at county level. Outcome data are the number of substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population calculated from the 2010, 2015, and 2020 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services directories. Racial segregation indices and population shares calculated from the 5-year 2009, 2014, and 2019 American Community Surveys. County controls include the natural log of county income per capita, county race-specific opioid mortality rates, county median age. State controls include indicators for prescription drug monitoring programs (including “must access”), “pill mill” laws, good samaritan laws, naloxone access laws,. All regressions include county fixed effects and year fixed effects. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table A2.

Association between racial segregation indices and substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population, controlling for population shares.

| All facilities |

MAT facilities |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main estimate | Controlling for population shares | Main estimate | Controlling for population shares | |

| −0.424 | −0.377 | −0.271 | −0.239 | |

| (0.372) | (0.395) | (0.219) | (0.240) | |

| −0.266 | −0.319 | −0.572* | −0.610** | |

| (0.412) | (0.411) | (0.302) | (0.303) | |

| −6.859** | −4.296 | −4.682** | −4.817 | |

| (3.044) | (5.550) | (2.308) | (4.896) | |

| 0.369 | 0.267 | 0.175 | 0.081 | |

| (0.494) | (0.503) | (0.268) | (0.285) | |

| −3.343 | −5.462 | −3.516 | −2.876 | |

| (3.213) | (6.603) | (2.285) | (4.572) | |

| −0.217 | −0.305 | −0.135 | −0.509 | |

| (0.777) | (0.851) | (0.639) | (0.662) | |

| Share White | 1.452 | 5.271 | ||

| (5.764) | (3.813) | |||

| Share Black | −1.542 | 5.360 | ||

| (6.319) | (5.177) | |||

| Share Hispanic | 3.228 | 3.067 | ||

| (10.63) | (7.250) | |||

| N | 9258 | 9258 | 9258 | 9258 |

| 0.842 | 0.842 | 0.750 | 0.750 | |

| County fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State-year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| County controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors clustered at county level. Outcome data are the number of substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population calculated from the 2010, 2015, and 2020 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services directories. Racial segregation indices and population shares calculated from the 5-year 2009, 2014, and 2019 American Community Surveys. All regressions include controls for the natural log of county income per capita, county race-specific opioid mortality rates, county median age, county fixed effects and state-year fixed effects. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Appendix Table A3.

Comparison of estimates from full sample and dropping “switchers”, all facilities

| Full sample (1) | Drop switchers (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Black dissimilarity | ||

| −0.312 | −0.601 | |

| (0.369) | (0.605) | |

| N | 9258 | 4179 |

| Panel B: Hispanic dissimilarity | ||

| −0.205 | −0.860 | |

| (0.391) | (0.673) | |

| N | 9258 | 3855 |

| Panel C: White-Black interaction | ||

| −6.001** | −7.182** | |

| (2.985) | (3.659) | |

| N | 9258 | 4479 |

| Panel D: Black-White interaction | ||

| 0.369 | −0.034 | |

| (0.482) | (0.837) | |

| N | 9258 | 4743 |

| Panel E: White-Hispanic interaction | ||

| −3.008 | −42.11*** | |

| (3.132) | (15.44) | |

| N | 9258 | 684 |

| Panel E: Hispanic-White interaction | ||

| 0.448 | −0.225 | |

| (0.747) | (1.091) | |

| N | 9258 | 5337 |

Notes: Standard errors clustered at county level. Outcome data are the number of substance use treatment facilities per 100,000 population calculated from the 2010, 2015, and 2020 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services directories. Racial segregation indices and population shares calculated from the 5-year 2009, 2014, and 2019 American Community Surveys. Estimates in column 1 use the full sample. Estimates in column 2 drop counties in which the segregation index measure increases and decreases in the sample period. All regressions control for the natural log of county income per capita, county race-specific opioid mortality rates, county median age, county fixed effects and state-year fixed effects. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table A4.

Association between racial segregation indices and substance use treatment facilities providing naltrexone per 100,000 population, 2014–2019

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| 0.021 | −0.0216 | |

| (0.463) | (0.466) | |

| −0.946* | −1.053** | |

| (0.511) | (0.511) | |

| −6.563 | −8.144** | |

| (4.178) | (3.881) | |

| 0.500 | 0.340 | |

| (0.681) | (0.683) | |

| −2.221 | −4.488 | |

| (4.429) | (3.963) | |

| 0.812 | 0.809 | |

| (1.040) | (1.027) | |

| N | 6172 | 6172 |

| 0.803 | 0.805 | |

| County fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| State-year fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| County controls | No | Yes |

Notes: Standard errors clustered at county level. Outcome data are the number of substance use treatment facilities providing Naltrexone per 100,000 population calculated from the 2015 and 2020 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services directories. Racial segregation indices and population shares calculated from the 5-year 2014 and 2019 American Community Surveys. Regression controls include the natural log of county income per capita, county race-specific opioid mortality rates, county median age, county fixed effects and state-year fixed effects. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Ahmad F.B., Cisewski J.A., Rossen L.M., Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm National Center for Health Statistics.

- Allen B., Nolan M.L., Kunins H.V., Paone D. Racial differences in opioid overdose deaths in New York City, 2017. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2019;179:576–578. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andraka-Christou B. Addressing racial and ethnic disparities in the use of medications for opioid use disorder. Health Affairs. 2021;40:920–927. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell J.T., Ford C.L., Wallace S.P., Wang M.C., Takahashi L.M. Racial and ethnic residential segregation and access to health care in rural areas. Health & Place. 2017;43:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantone R.E., Garvey B., O'Neill A., Fleishman J., Cohen D., Muench J., Bailey S.R. Predictors of medication-assisted treatment initiation for opioid use disorder in an interdisciplinary primary care model. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2019;32:724–731. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.05.190012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Multiple cause of death 1999-2019 on CDC WONDER online database. 2020. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Understanding the epidemic. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html March 17.

- de Chaisemartin C., D'Haultfœuille X. Two-way fixed effects and differences-in-differences with heterogeneous treatment effects: A survey. Econom. J. utac017. 2022 doi: 10.1093/ectj/utac017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.E., Franz B., Cronin C.E., Lindenfeld Z., Lai A.Y., Pagán J.A. Racial/ethnic disparities in the availability of hospital based opioid use disorder treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2022;138 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick A.W., Pacula R.L., Gordon A.J., Sorbero M., Burns R.M., Leslie D., Stein B.D. Growth in buprenorphine waivers for physicians increased potential access to opioid agonist treatment, 2002-11. Health Affairs. 2015;34:1028–1034. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J.R., Hansen H. Evaluation of increases in drug overdose mortality rates in the US by race and ethnicity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:379–381. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedel W.C., Shapiro A., Cerdá M., Tsai J.W., Hadland S.E., Marshall B.D.L. Association of racial/ethnic segregation with treatment capacity for opioid use disorder in counties in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust S.E., Haselswerdt J. A crisis in my community? Local-level awareness of the opioid epidemic and political consequences. Social Science & Medicine. 2021;291 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Bacon A. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. Journal of Econometrics. 2021;225:254–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2021.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H., Netherland J. Is the prescription opioid epidemic a white problem? American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106:2127–2129. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H.B., Siegel C.E., Case B.G., Bertollo D.N., DiRocco D., Galanter M. Variation in use of buprenorphine and methadone treatment by racial, ethnic, and income characteristics of residential social areas in New York City. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2013;40:367–377. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9341-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander M.A., Chang C.C., Douaihy A.B., Hulsey E., Donohue J.M. Racial inequity in medication treatment for opioid use disorder: Exploring potential facilitators and barriers to use. J. Alcohol Drug Depend. 2021;227 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iceland J., Sharp G., Timberlake J.M. Sun belt rising: Regional population change and the decline in black residential segregation. Demography. 2013;50:97–123. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0136-6. 1970–2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K., Kim I.S. On the use of two-way fixed effects regression models for causal inference with panel data. Political Analysis. 2021;29:405–415. doi: 10.1017/pan.2020.33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James K., Jordan A. The opioid crisis in black communities. Journal of Law Medicine & Ethics. 2018;46:404–421. doi: 10.1177/1073110518782949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilaru A.S., Xiong A., Lowenstein M., Meisel Z.F., Perrone J., Khatri U., Mitra N., Delgado M.K. Incidence of treatment for opioid use disorder following nonfatal overdose in commercially insured patients. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.W., Morgan E., Nyhan B. Treatment versus punishment: Understanding racial inequalities in drug policy. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2020;45:177–209. doi: 10.1215/03616878-8004850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y., Zhou J., Zheng Z., Amaro H., Guerrero E.G. Using machine learning to advance disparities research: Subgroup analyses of access to opioid treatment. Health Services Research. 2022;57:411–421. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagisetty P.A., Ross R., Bohnert A., Clay M., Maust D.T. Buprenorphine treatment divide by race/ethnicity and payment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:979–981. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter D.T., Parisi D., Taquino M.C. The geography of exclusion: Race, segregation, and concentrated poverty. Social Problems. 2012;59:364–388. doi: 10.1525/sp.2012.59.3.364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold K., Ali B. Racial/ethnic differences in opioid-involved overdose deaths across metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas in the United States, 1999−2017. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2020;212 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold K.M., Jones C.M., Olsen E.O., Giroir B.P. Racial/ethnic and age group differences in opioid and synthetic opioid–involved overdose deaths among adults aged ≥ 18 years in metropolitan areas—United States, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:967–973. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6843a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson S., Schroeder J., Van Riper D., Kugler T., Ruggles S. IPUMS; 2021. IPUMS national historical geographic information System: Version 16.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massey D.S., Denton N.A. The dimensions of residential segregation. Social Forces. 1988;67:281–315. doi: 10.1093/sf/67.2.281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson C.L., Tanz L.J., Quinn K., Kariisa M., Patel P., Davis N.L. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths – United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202–207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics The linkage of national center for health statistics survey data to the national death index – 2019 linked mortality file (LMF): Linkage methodology and analytic considerations. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-linkage/mortality-methods.htm

- Provine D.M. Race and inequality in the war on drugs. Annual Review of Law and Social Science. 2011;7:41–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102510-105445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartin M.X., McKenna R.M., Ali M.M., Krebs J.D. Racial disparities in payment source of opioid use disorder treatment among non-incarcerated justice-involved adults in the United States. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2020;23:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff D.M., Nielsen T., Hoeppner B.B., Terplan M., Hansen H., Bernson D., Diop H., Bharel M., Krans E.E., Selk S., Kelly J.F. Assessment of racial and ethnic disparities in the use of medication to treat opioid use disorder among pregnant women in Massachusetts. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahler G.J., Mennis J. Treatment outcome disparities for opioid users: Are there racial and ethnic differences in treatment completion across large US metropolitan areas? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2018;190:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein B.D., Dick A.W., Sorbero M., Gordon A.J., Burns R.M., Leslie D.L., Pacula R.L. A population-based examination of trends and disparities in medication treatment for opioid use disorders among Medicaid enrollees. Substance Abuse. 2018;39:419–425. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2018.1449166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S.V., Acevedo-Garcia D., Osypuk T.L. Racial residential segregation and geographic heterogeneity in black/white disparity in poor self-rated health in the US: A multilevel statistical analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:1667–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National directory of drug and alcohol abuse treatment facilities. 2010. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National directory of drug and alcohol abuse treatment facilities. 2015. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National directory of drug and alcohol abuse treatment facilities. 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Substance abuse and mental health services administration, national survey of substance abuse treatment services (N-SSATS): 2020. Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities. 2021 (Rockville, MD) [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . 2022. March 3. FAQs about the new buprenorphine practice guidelines.https://www.samhsa.gov/medicationassisted-treatment/become-buprenorphine-waivered-practitioner/new-practice-guidelines-faqs [Google Scholar]

- Trounstine J. Segregation and inequality in public goods. American Journal of Polymer Science. 2016;60:709–725. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service . 2020. Rural-urban Continuum codes.https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N.D., Frieden T.R., Hyde P.S., Cha S.S. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:2063–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman S.E., Larochelle M.R., Ameli O., Chaisson C.E., McPheeters J.T., Crown W.H., Azocar F., Sanghavi D.M. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.R., Collins C. Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J., Bhalerao A., Bawor M., Bhatt M., Dennis B., Mouravska N., Zielinski L., Samaan Z. ‘Don't judge a book by its cover’: A qualitative study of methadone patients' experiences of stigma. Substance Abuse. 2017;11 doi: 10.1177/1178221816685087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.