Abstract

Objective

Increased white blood cell count (WBC) is known to be associated with preeclampsia (PE). This study aimed to determine whether WBC count >10×109/L had significant impact on late-onset PE (LOPE) during the first and second trimesters.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted in 600 pregnant women from Shanghai Pudong Hospital in China from July 2019 to August 2020. They were classified into four groups: Group 1: WBC count ≤10×109/L at 10th–12th week and 24th–26th week; Group 2, WBC count ≤10×109/L at 10th–12th week but WBC count >10×109/L at 24th–26th week; Group 3, WBC count >10×109/L at 10th–12th week but WBC count≤10×109/L at 24th–26th week; Group 4, WBC count >10×109/L at 10th–12th week and 24th–26th week. Complete blood count results from 10th–12th week and 24th–26th week were obtained for each patient. Maternal laboratory values including white blood cell (WBC) count were compared between the four groups.

Results

34 women were diagnosed with LOPE at predelivery. The estimated incidence rate of LOPE during pregnancy was 3.6% in Group 1, 5.8% in Group 2, 7.2% in Group 3, and 11% in Group 4 for the respective WBC level of Group 1, 2, 3 and 4. After adjusting for potential influencing factors of PE, the respective relative risks for LOPE was 1.0 (reference), 1.76 (95% CI 0.37, 8.30), 2.23 (0.85, 5.89), and 3.07 (1.34, 7.02) (P for trend = 0.048).

Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that WBC count >10×109/L during the first and second trimesters is a risk of LOPE.

Keywords: White blood cell count, Neutrophil, Pregnant women, Inflammatory response, Late-onset preeclampsia

White blood cell count; Neutrophil; Pregnant women; Inflammatory response; Late-onset preeclampsia.

1. Introduction

Pre-eclampsia (PE) is a common complication during pregnancy, affecting 3–5% pregnant women. Epidemiological studies have shown that PE is a risk factor contributing to both maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality [1, 2], including maternal renal insufficiency, liver disorder, neurological complications and fetal growth restriction. PE can be subdivided into the early-onset phenotype (EOPE) and late-onset phenotype (LOPE) [3]. Previous studies have demonstrated that LOPE is a maternal constitutional disorder and related to white blood cell count (WBC) during the first trimester [4, 5].

Even though the pathogenesis of PE remains largely unknown, studies suggested that it may be related to the exaggeration of the systemic inflammatory process [6, 7], and more importantly some other studies considered it as an exaggerated intravascular inflammatory response to pregnancy [3, 8, 9]. In addition, intravascular inflammatory response is known to be related to inflammatory cytokines released from WBC. For example, neutrophils can release a variety of inflammatory cytokines to activate inflammatory cells and immune responses, leading to oxidative stress and endothelial injury, thereby promoting the progression of PE [10, 11, 12, 13]. Many studies in the literature have focused on comparing WBC changes in the first trimester and found that the increased level of WBC was a predictor of PE [5, 14]. The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and monocyte-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) are also reported to be effective in clinical assessment, disease severity evaluation, and prognosis prediction of PE [15]. However, WBC percentiles show different changes during different trimester in normal pregnancy [16], therefore the use of a single spot WBC count could not reflect the potential risk of PE precisely.

So, we conducted this prospective study to determine whether increased WBC level had significant impact on LOPE during the first and second trimesters in women with singleton nulliparous pregnancies delivered at our hospital by using two-spot screening.

2. Research design and methods

2.1. Study population

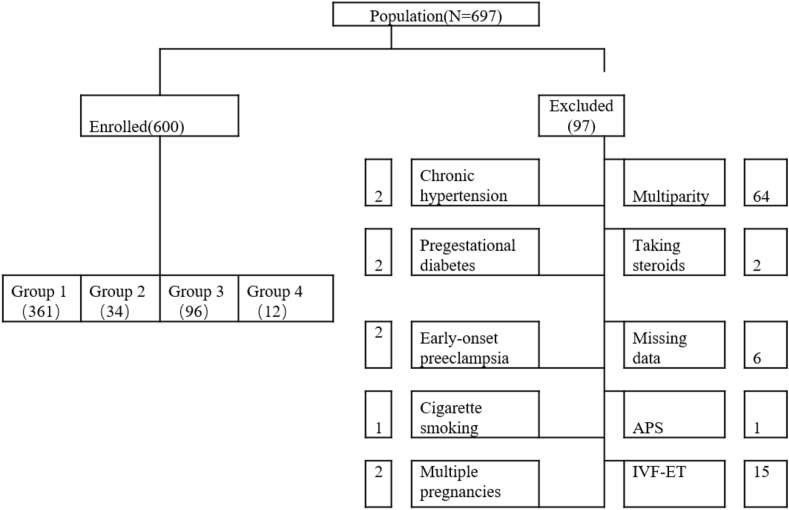

Included in this study were 697 pregnant women who had regular prenatal care and maintained complete data of prenatal care in Shanghai Pudong Hospital from July 2019 to August 2020. They were required to participate in antepartum screening at 10th–12th week and 24th–26th. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review committee of the said hospital. Of the 697 initially recruited pregnant women, 97 were excluded due to the following reasons: early-onset preeclampsia (EOPE), bacterial vaginosis, periodontal disease, multiparity, chronic hypertension, pregestational diabetes, thrombophilia, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), nephropathies, use of steroids, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, alcohol abuse, cigarette smoking, hematological diseases, comorbidities or major organ dysfunction, history of thyroid disease, in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET), multiple pregnancies, and hyperemesis history [17]. Finally, 600 nulliparity women were included in this study for analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the exclusion process in the study cohort. APS, Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (IVF-ET), In vitro fertilization-embryo transfer.

All subjects were screened for blood pressure at 10th–12th week and predelivery based on the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) definition of chronic hypertension criteria. The normal WBC reference range in our laboratory is 4–10×109/L; by reference to previous studies [18, 19, 20], we set the WBC cutoff value in this study at >10×109/L and our laboratory normal reference range. To examine the relationship between the WBC level and the incidence of PE during the first and second trimesters, we subcategorized the patients into four groups: Group 1: WBC count ≤10×109/L at 10th–12th week and 24th–26th week; Group 2, WBC count ≤10×109/L at 10th–12th week but WBC count >10×109/L at 24th–26th week; Group 3, WBC count >10×109/L at 10th–12th week but WBC count≤10×109/L at 24th–26th week; Group 4, WBC count >10×109/L at 10th–12th week and 24th–26th week.

2.2. Laboratory measurements

All the participants received an initial prenatal screening, including physical examination, anthropometric measurements, biochemical measurements, and lifestyle behaviours (smoking and alcohol use), reproductive history, menstrual history, and physical activity at 10th–12th week. A family history of hypertension was defined as the presence of a mother, father, sister, or brother with chronic hypertension diagnosed by a physician. Body mass index (BMI) was used as a measure of overall obesity (kg/m2). After a 10-min rest in a quiet room, systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured in the right arm using an electronic sphygmomanometer. WBC, red blood cell count (RBC) and platelet count (PLT) were measured by using a XN-1000i autoanalyser (Sysmex, Hyogo, Japan).

PE was diagnosed based on the criteria of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in 2020 [21]: (i) SBP 140 mmHg or more, or DBP 90 mmHg or more on two occasions at least 4 h apart after 20 weeks of gestation in a woman with a previously normal blood pressure. Systolic blood pressure of 160 mmHg or more or diastolic blood pressure of 110 mmHg or more (Severe hypertension can be confirmed within a short interval (minutes) to facilitate timely antihypertensive therapy). (ii) proteinuria (Protein/creatinine ratio ≥0.3 or dipstick reading of 1+) or (iii) in the absence of proteinuria, new-onset hypertension with the new onset of any of the following: Thrombocytopenia (Platelet count ≤100,000/microliter), renal insufficiency, Serum creatinine concentrations ≥1.1 mg/dl, elevated blood concentrations of liver transaminases to twice normal concentration, pulmonary oedema, cerebral or visual symptoms. Early-onset preeclampsia is diagnosed before 34 weeks of gestation whereas late-onset preeclampsia is diagnosed from 34 weeks of gestation [3].

2.3. Statistical analysis

All analyses were accomplished by using SPSS 20.0 software. Descriptive statistics included means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Continuous variables were tested by the Student's t test. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test and correlation between the incidence of PE was tested by Pearson's correlation. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CI were generated as indicated. Continuous variables were tested by one-way analysis of variance with the Duncan test set at a significance level of 5%. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association of white blood cell count with GDM, adjusting for the possible confounding factors. The level of significance was 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Enrolled criteria

As shown in the flow diagram of Figure 1, 697 women were initially enrolled in this study. Of them, 6 who had incomplete data and 91 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, 600 pregnant women were included for analysis. The final population for this analysis included 600 women for analysis.

3.2. Comparison of the baseline characteristics between the four groups

The results of comparison of the baseline characteristics between the four groups are shown in Table 1. Group 1, Group 2 and Group 3 had lower BMI and systolic blood pressure levels at predelivery compared to Group 4 (p < 0.05), but there was no a statistically significant difference among the groups in terms of maternal age (P = 0.286). 34 women (5.6%) were diagnosed with late-onset PE according to the criteria of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) in 2020.

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics according to change of white blood cell count.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 361 | 34 | 96 | 109 | |

| NO | 13 | 2 | 7 | 12 | |

| Maternal age (years) | 28.9 ± 4.49 | 29.35 ± 5.01 | 28.89 ± 4.55 | 28.04 ± 4.45 | 0.286 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| Prepregnant | 21.68 ± 3.17∗ | 23.39 ± 3.49 | 22.43 ± 3.48 | 22.71 ± 3.81 | 0.002 |

| Predelivery | 27.3 ± 3.44∗ | 28.94 ± 3.82 | 27.36 ± 4.29∗ | 29.02 ± 4.02 | <0.001 |

| Increment | 5.62 ± 2.01∗ | 5.55 ± 1.97 | 5.16 ± 2.09∗ | 6.31 ± 2.52 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | |||||

| Prepregnant | 56.25 ± 8.78∗ | 59.83 ± 10.59 | 57.74 ± 9.33 | 58.4 ± 10.34 | 0.037 |

| Predelivery | 70.85 ± 9.76∗ | 74.02 ± 11.96 | 71.2 ± 9.05∗ | 74.58 ± 10.99 | 0.004 |

| Increment | 14.59 ± 5.26∗ | 14.19 ± 5.31 | 13.36 ± 5.31∗ | 16.18 ± 6.19 | 0.004 |

| Diastolic blood pressure at delivery (mmHg) | 73.56 ± 8.85 | 75.09 ± 8.52 | 73.68 ± 9.49 | 76.16 ± 9.88 | 0.062 |

| Systolic blood pressure at delivery (mmHg) | 118.99 ± 10.88∗ | 117.21 ± 10.44∗ | 119.74 ± 10.04∗ | 123.58 ± 11.68 | 0.001 |

| Red blood cell count (×1012/L) | |||||

| between 10–12 gestational weeks | 4.05 ± 0.37∗ | 4.16 ± 0.4 | 4.11 ± 0.37 | 4.13 ± 0.43 | 0.08 |

| between 24–26 gestational weeks | 3.71 ± 0.34∗ | 3.86 ± 0.31 | 3.83 ± 0.38 | 3.84 ± 0.36 | <0.001 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | |||||

| between 10–12 gestational weeks | 212.92 ± 43.3∗ | 234.65 ± 35.9 | 216.85 ± 42.3∗ | 239.32 ± 46.9 | 0.001 |

| between 24–26 gestational weeks | 201.97 ± 48∗ | 200.06 ± 36.6∗ | 208.56 ± 50∗ | 224.9 ± 51.9 | <0.001 |

| First cesarean delivery | 10 | 2∗ | 5 | 9 | 0.088 |

| Infant gestation (weeks) | 39.1 ± 1.3 | 39.4 ± 1 | 38.9 ± 1.5 | 38.8 ± 1.3 | 0.102 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3367 ± 437 | 3574 ± 423∗ | 3275 ± 502 | 3384 ± 471 | 0.011 |

Data are means ± SD. Analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis by Duncan's test: ∗P < 0.05 with group 4; N is the total number in the group, No. is the number in the category with the preeclampsia.

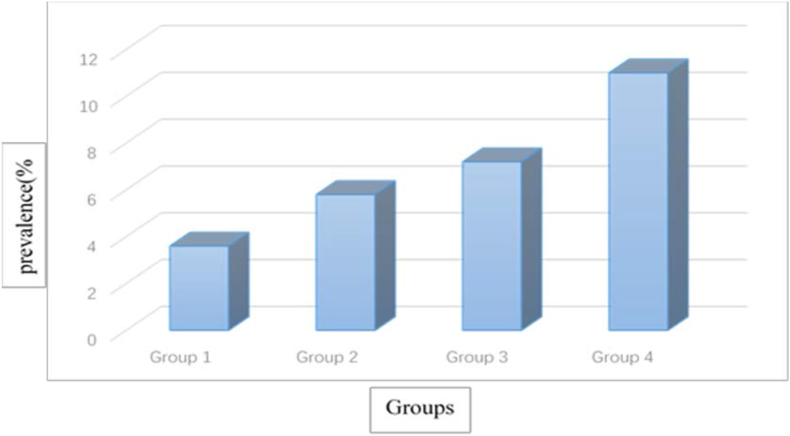

The significant differences in systolic blood pressure at predelivery. Weight and BMI were largely accounted for by group 1. And the other three subgroups accounted for the significant difference in systolic blood pressure at predelivery compared with the group 4. On further analysis, a significant positive correlation was found between the prevalence of late-onset PE and the duration of WBC count >10×109/L (P = 0.027): 3.6% in Group 1, 5.8% in Group 2, 7.2% in Group 3, and 11% in the Group 4 (Figure 2). To determine the independent effect of duration of WBC count >10×109/L on the progression of late-onset PE, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed adjusting for age and BMI, which showed a difference between the group 4 and the other three groups, but the other three groups did not show significant difference with each other. Duration of white blood cell count >10×109/L remained a significant factor associated with elevated prevalence of late-onset PE (adjusted OR3.07, 95% CI 1.34–7.02, P for trend = 0.048) after adjusting for age and BMI (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of late-onset PE in relation to the duration and timing of white blood cell count >10×109/L. Comparison by Pearson's correlation between incidence of late-onset PE and white blood cell count groups; P = 0.027.

Table 2.

Relationship between preeclampsia and groups.

| N | No. | % | Crude OR 95% CIa | Adjusted OR 95% CIb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 361 | 13 | 3.6 | 1 | 1 |

| Group 2 | 34 | 2 | 5.8 | 1.67 (0.36–7.74) | 1.76 (0.37,8.30) |

| Group 3 | 96 | 7 | 7.2 | 2.11 (0.84–7.43) | 2.23 (0.85,5.89) |

| Group 4 | 109 | 12 | 11 | 3.31 (1.46–7.49)∗ | 3.07 (1.34,7.02)∗ |

| Trend test | P = 0.005 | P = 0.048 |

N is the total number in the group, No. is the number in the category with the preeclampsia, and % is the proportion in the group with the preeclampsia. Model 1: unadjusted. Model 2: adjusted for age, BMI. ⁎ P < 0.05.

3.3. Comparisons of preeclampsia and non-preeclampsia women

Age, BMI, SBP and SBP levels in pregnant women with LOPE were significant higher than those in non-PE pregnant women (p < 0.001), but there was no a statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of diastolic blood pressure at 10th–12th week (P = 0.079). (Supplementary Table 4).

4. Discussion

Pre-eclampsia (PE) is a multisystem pregnancy disorder characterized by variable degrees of placental malperfusion, with release of soluble factors into the circulation. These factors cause maternal vascular endothelial injury, which leads to maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity [22]. Placental malperfusion is reported to be related to an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the antioxidant defence system [23]. To reduce the occurrence of severe adverse events, it is necessary to identify pregnant women at high risk of PE as early as possible for the sake of taking early intervention measures.

In this study, we analyzed maternal white blood cell count and differential profiles between non-preeclampsia women and preeclampsia women. Our data showed that the white blood cell count >10×109/L during the first and second trimesters was significantly correlated with LOPE. However, the other three groups did not show significantly differences in late-onset PE women.

In the past several years, some indicators of maternal complete blood count indices blood cell had been identified as predictors of PE, such as WBC and neutrophil count [24], higher neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio [7], and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio [13]. A retrospective study showed that neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio could predict preeclampsia with sensitivity and specificity rates of 79.1% and 38.7% [25], however, there were no large-scale and prospective studies to reproduce these results, although these test results were cheap and easily accessible, predictability of these biomarkers still needed to be verified.

It was found in our study that differential WBC count underwent significant changes in PE at 10th–12th week and 24th–26th week, and the result during the first trimester was similar with that reported in a retrospective case-control study [5]. Further, neutrophils showed the significant differences in late-onset PE women at 10th–12th week, but not at 24th–26th week. Lymphocyte count also showed significant differences in PE women at 24th–26th week, but not at 10th–12th week. The result of 10th–12th week were consistent with the observation of Tamar Tzur [26], who reported an increase in white blood cell count and neutrophil count in preeclamptic patients, however, although lymphocyte count increased in preeclamptic patients compared with non-preeclampsia women, the difference was not significant. Interestingly, the lymphocyte count showed statistical differences at 24th–26th week (Supplementary Table 4). So, the white blood cell count showed differences at 24th–26th week because of the lymphocyte count changes. The lymphocytes and specific cell adhesion molecules played an important role in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia during the third trimester [27]. We think that LOPE is a chronic and often slowly progressing disease, resulting in a chronic inflammatory status accompanied by slowly increased lymphocytes.

Leukocytosis is considered to be evidence of an increased inflammatory response in healthy pregnancies [28]. This also appears in patients who had been administered steroids [29], preterm delivery and in premature infants [30], or could be a marker of a chronic inflammatory process such as bacterial vaginosis or periodontal disease. In our study, we excluded bacterial vaginosis through screening the vaginal secretions at 10th–12th week. Besides, the white blood cell count did not show significantly differences in preterm delivery women at 10th–12th week and 24th–26th week (Supplementary Table 3), which is coincident with Nasrin Asadi ‘s research [31], so we believed that preterm delivery had been excluded to influence the leukocyte count changes. Therefore, we believed that our data of increased neutrophil count at 10th–12th week and 24th–26th week in late-onset preeclampsia represented the severity of inflammatory response during the disease process. In addition, the inflammatory response is long-time process and may exist through the whole process of pregnancy. Bernard et al showed that the total leukocyte count were significantly different from the time of hospital admission to the time of admission to the labor and delivery unit [32].

In this study, we mainly focused on pregnant women with white blood cell count >10×109/L during first and second trimester, and the result showed that a persistent increase in WBC count was independently associated with an increased risk of developing LOPE. Furthermore, the prevalence of late-onset PE was related with the timing and duration of persistent increased white blood cell count. These women also had significantly gestational increment in weight and BMI, which agreed with the finding that higher BMI at in the early pregnancy and predelivery were associated with higher prevalence of PE [17, 32], These findings may help explain the increased incidence of LOPE from Group 1 to Group 4 in this study (Table 2). From group 1 to group 3, there was no inter-group differences, it might reveal that the persistent white blood cell count >10×109/L was an important factor for the increased incidence of LOPE.

The cause-and-effect relationship between increased WBC count and PE is not clear. Placental mal-perfusion would release large numbers of soluble factors into the circulation, and these factors may cause maternal vascular endothelial injury, leading to maternal elevated neutrophil and WBC counts. Meanwhile, activated neutrophils and WBC secondary to the release of inflammatory cytokines may aggravate endothelial dysfunction and accelerate the progression of PE.

On the other hand, the diastolic blood pressure levels at predelivery did not show statistical differences among the four groups (P = 0.062), but the systolic blood pressure showed inter-group and intra-group differences (P < 0.001). We considered that inflammatory response did not cause blood volume change, but it might lead to the oxidative stress and endothelial injury, thereby promoting the vasoconstriction and giving rise to higher systolic blood pressure.

5. Limitation

This study has some limitation. First, it is a single-center study and the sample size in LOPE group is relatively small, so that this research may not be representative of the general population, knowing that different ethnicities may have different genetics in terms of WBC count during pregnancy. In addition, the parameters may be affected by clinical events. Although we tested the WBC count at different gestational weeks, it could not represent every gestational week. However, our study was prospective in nature, so that we could know about the exact duration of the process.

6. Conclusion

Despite some limitations, our data suggest that the risk of developing LOPE increases with persistent WBC >10×109/L during the first and second trimesters, which could be used to predict LOPE. Nevertheless, prospective multi-center studies are warranted to better reveal the association between persistent increase of WBC count and LOPE.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Kui Wu: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Wei Gong: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Hui-hui Ke: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Hua Hu: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Li Chen: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This study was supported by Talents Training Program of Pudong Hospital affiliated to Fudan University (Project no. PJ201902).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Contributor Information

Hua Hu, Email: Huhua20212022@163.com.

Li Chen, Email: chenli8369@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Chappell L.C., Cluver C.A., Kingdom J., Tong S. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2021;398(10297):341–354. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mol B.W.J., Roberts C.T., Thangaratinam S., Magee L.A., de Groot C.J.M., Hofmeyr G.J. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):999–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burton G.J., Redman C.W., Roberts J.M., Moffett A. Pre-eclampsia: pathophysiology and clinical implications. BMJ. 2019;366:l2381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raymond D., Peterson E. A critical review of early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2011;66(8):497–506. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3182331028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orgul G., Aydin Hakli D., Ozten G., Fadiloglu E., Tanacan A., Beksac M.S. First trimester complete blood cell indices in early and late onset preeclampsia. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;16(2):112–117. doi: 10.4274/tjod.galenos.2019.93708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiessl B. Inflammatory response in preeclampsia. Mol. Aspect. Med. 2007;28(2):210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yakistiran B., Tanacan A., Altinboga O., Erol A., Senel S., Elbayiyev S., et al. Role of derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, uric acid-to-creatinine ratio and Delta neutrophil index for predicting neonatal outcomes in pregnancies with preeclampsia. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022;1–6 doi: 10.1080/01443615.2022.2040968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redman C.W., Sargent I.L. Circulating microparticles in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 2008;29(Suppl A):S73–S77. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phipps E.A., Thadhani R., Benzing T., Karumanchi S.A. Pre-eclampsia: pathogenesis, novel diagnostics and therapies. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019;15(5):275–289. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0119-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang Q., Li W., Yu N., Fan L., Zhang Y., Sha M., et al. Predictive role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in preeclampsia: a meta-analysis including 3982 patients. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2020;20:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panwar M., Kumari A., Hp A., Arora R., Singh V., Bansiwal R. Raised neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and serum beta hCG level in early second trimester of pregnancy as predictors for development and severity of preeclampsia. Drug Discov Ther. 2019;13(1):34–37. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2019.01006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu N., Guo Y.N., Gong L.K., Wang B.S. Advances in biomarker development and potential application for preeclampsia based on pathogenesis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. X. 2021;9 doi: 10.1016/j.eurox.2020.100119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gogoi P., Sinha P., Gupta B., Firmal P., Rajaram S. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet indices in pre-eclampsia. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2019;144(1):16–20. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yücel B., Ustun B. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, platelet to lymphocyte ratio, mean platelet volume, red cell distribution width and plateletcrit in preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2017;7:29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J., Zhu Q.W., Cheng X.Y., Liu J.Y., Zhang L.L., Tao Y.M., et al. Assessment efficacy of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and monocyte-lymphocyte ratio in preeclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2019;132:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lurie S., Rahamim E., Piper I., Golan A., Sadan O. Total and differential leukocyte counts percentiles in normal pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2008;136(1):16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartsch E., Medcalf K.E., Park A.L., Ray J.G., High Risk of Pre-eclampsia Identification G Clinical risk factors for pre-eclampsia determined in early pregnancy: systematic review and meta-analysis of large cohort studies. BMJ. 2016;353:i1753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asadollahi K., Beeching N.J., Gill G.V. Leukocytosis as a predictor for non-infective mortality and morbidity. QJM. 2010;103(5):285–292. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcp182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cannon C.P., McCabe C.H., Wilcox R.G., Bentley J.H., Braunwald E. Association of white blood cell count with increased mortality in acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina pectoris. OPUS-TIMI 16 Investigators. Am. J. Cardiol. 2001;87(5):636–639. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01444-2. A10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kazmierski R., Guzik P., Ambrosius W., Kozubski W. Leukocytosis in the first day of acute ischemic stroke as a prognostic factor of disease progression. Wiad. Lek. 2001;54(3-4):143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia: ACOG practice bulletin, number 222. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;135(6):e237–e260. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chappell L.C., Cluver C.A., Kingdom J., Tong S. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2021;398(10297):341–354. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh T.T., Chen S.F., Lo L.M., Li M.J., Yeh Y.L., Hung T.H. The association between maternal oxidative stress at mid-gestation and subsequent pregnancy complications. Reprod. Sci. 2012;19(5):505–512. doi: 10.1177/1933719111426601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao D., Chen L., Li Q., Liu G., Wang W., Li J., et al. Predictive value of the peripheral blood parameters for preeclampsia. Clin. Lab. 2022;68(3) doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2021.210726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirbas A., Ersoy A.O., Daglar K., Dikici T., Biberoglu E.H., Kirbas O., et al. Prediction of preeclampsia by first trimester combined test and simple complete blood count parameters. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015;9(11):QC20–Q23. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/15397.6833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tzur T., Weintraub A.Y., Sergienko R., Sheiner E. Can leukocyte count during the first trimester of pregnancy predict later gestational complications? Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013;287(3):421–427. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2603-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bajnok A., Ivanova M., Rigo J., Jr., Toldi G. The distribution of activation markers and selectins on peripheral T lymphocytes in preeclampsia. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/8045161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lurie S., Frenkel E., Tuvbin Y. Comparison of the differential distribution of leukocytes in preeclampsia versus uncomplicated pregnancy. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 1998;45(4):229–231. doi: 10.1159/000009973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Denison F.C., Elliott C.L., Wallace E.M. Dexamethasone-induced leucocytosis in pregnancy. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1997;104(7):851–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb12035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barak M., Cohen A., Herschkowitz S. Total leukocyte and neutrophil count changes associated with antenatal betamethasone administration in premature infants. Acta Paediatr. 1992;81(10):760–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1992.tb12098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asadi N., Faraji A., Keshavarzi A., Akbarzadeh-Jahromi M., Yoosefi S. Predictive value of procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and white blood cells for chorioamnionitis among women with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2019;147(1):83–88. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang W., Han F., Gao X., Chen Y., Ji L., Cai X. Relationship between gestational weight gain and pregnancy complications or delivery outcome. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12921-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.