Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an important cause of morbidity in Saudi Arabia.

OBJECTIVES:

Determine the incidence, clinical profile, course and outcomes of IBD in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

DESIGN:

Medical record review

SETTING:

Tertiary care center

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

Data were extracted from the medical records of all patients with IBD admitted to King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh, from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2019. The complications of IBD were classified as gastrointestinal or extraintestinal. Comorbidities were classified as either systemic diseases or gastrointestinal diseases.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES:

Epidemiology, clinical manifestations and complications of IBD.

SAMPLE SIZE AND CHARACTERISTICS:

435 patients with IBD, median (IQR) age at presentation 24.0 (14.0) years, 242 males (55.6%)

RESULTS:

The study population consisted of 249 patients with Crohn's disease (CD) (57.2%) and 186 with ulcerative colitis (UC) (42.8%). Nearly half were either overweight or obese. Abdominal pain, diarrhea and vomiting were the most common presenting symptoms. The most common extraintestinal manifestations were musculoskeletal (e.g., arthritis and arthralgia). Colorectal cancer was diagnosed in 3.2%. Patients with other gastrointestinal (GI) comorbidities were at higher risk of developing GI complications of IBD (P≤.05). Biological agents were used to treat 212 patients (87%) with CD and 102 patients (57%) with UC.

CONCLUSIONS:

The number of patients diagnosed with IBD and their body mass index increased each year over the period of interest. However, the rate of surgical intervention and number of serious complications fell. This improvement in outcomes was associated with a higher percentage of patients receiving biological therapy.

LIMITATIONS:

Incomplete data. Some patients diagnosed and/or followed up at other hospitals.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

None.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory process that primarily damages the gastrointestinal (GI) tract but may involve other organs. The most common forms of IBD are ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD).1,2 The prevalence of IBD is highest in Western countries, specifically North America and Northern Europe.3,4 It is estimated that the prevalence of IBD in American adults is 1.3% (approximately 3 million people).5

There is little data on IBD in the Middle East. However, some data suggest that the disease is common.6,7 A retrospective study of colonic biopsies performed from January 2002 to July 2007 at a tertiary center in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, reported that 136 (19.1%) of 711 biopsies were diagnostic of IBD.8 Another retrospective study of 312 cases managed at a tertiary center in Riyadh between 1970 and 2008 concluded that the incidence of IBD is increasing in Saudi Arabia.9 Yet, there is no data on the epidemiology and outcomes of patients with IBD in Saudi Arabia from the last decade. The present study investigated the epidemiology, clinical profile and course of patients with IBD admitted to our institution from 2009 to 2019. The study also aimed to identify the patient characteristics that are associated with a higher risk of GI complications and a need for surgical intervention.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was conducted at King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (KAMC-R). The medical records of all adult patients admitted to KAMC-R with a diagnosis of either CD or UC, between 2009 and 2019 were reviewed. Patients under 14 years of age were excluded. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia [RC20/112/R, 2/5/2020]. Data extracted from medical records included the demographics, risk factors for IBD, presenting symptoms, comorbidities, anatomical involvement, medications, surgical interventions, and the complications of IBD. Comorbidities were differentiated from complications. Some comorbidities may or may not be associated with IBD. The complications of IBD are closely related to the course of the disease.

Comorbidities were classified as either systemic diseases or gastrointestinal diseases. Gastrointestinal comorbidities included liver disease (hepatitis), GI infections (Clostridium difficile, Helicobacter pylori, Intestinal tuberculosis), pancreatobiliary complications, GI autoimmune disease, GERD, celiac disease, GI malignancy, and IBS. While systemic comorbidities included endocrine (e.g. diabetes), cardiovascular (e.g. hypertension), respiratory, musculoskeletal, and other conditions.

The complications of IBD were classified into one of two groups (i.e. gastrointestinal and extraintestinal complications). Gastrointestinal complications included fistulas, strictures, abscesses, intestinal obstruction, perforation, polyps, adhesions, anal fissures, toxic megacolon, cysts and gastrointestinal cancers (gastric and colorectal cancer). Extraintestinal manifestations were further subdivided into hepatobiliary (e.g. primary sclerosing cholangitis), ocular (e.g. episcleritis, conjunctivitis), dermatological (e.g. erythema nodosum), musculoskeletal (e.g. arthralgia, arthritis, back pain) and other manifestations (e.g. unspecified ulcer, periodontitis, bronchiolitis).

The sample size was calculated using the formula n=z2*p(1-p)/d2. Z is the level of confidence and we used 95%, the value of z corresponding to this is 1.96. P is the expected prevalence of IBD (2% based on a published study). The effect size, d, is equal to 0.02. Based on the above parameter, we estimated a need for at least 188 patients in our sample.

The Statistical Analysis System (SAS 2013, SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses. Standard descriptive analyses were performed. Categorical data are presented as frequency and percentage. Continuous data are presented as mean standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR). The chi-square test and the Fisher exact test were used to compare categorical data. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The present study included 435 patients with IBD including 249 with CD (57.2%) and 186 (42.8%) with UC (Table 1). Most were males (n= 242; 55.6%). While more men (149, 59.8%) were diagnosed with CD than women (100, 40.2%; P=.03), the sex distribution of UC was equivalent.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (n=435).

| Characterisitics | Overall | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | P value | Missing data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| Median (IQR) age at presentation (years) | 24.0 (14.0) | 22.0 (10) | 27.0 (18.8) | <.001 | |

| Age at time of present study years mean (SD) | 38.3 (16.2) | 35.2 (13.5) | 42.4 (18.5) | ||

| Age group at presentation | |||||

| 17-40 years | 280 (64.4) | 172 (69.1) | 108 (58.1) | .0008 | 0 |

| <17 years | 97 (22.3) | 57 (22.9) | 40 (21.5) | ||

| >40 years | 58 (13.3) | 20 (8.0) | 38 (20.4) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 242 (55.6) | 149 (59.8) | 93 (50.0) | .041 | 0 |

| Female | 193 (44.4) | 100 (40.2) | 93 (50.0) | ||

| Nationality | |||||

| Saudi | 405 (94.4) | 231 (93.9) | 174 (95.1) | .599 | 6 |

| Non-Saudi | 24 (5.6) | 15 (6.10) | 9 (4.9) | ||

| Risk factors | |||||

| Smoking | 59 (14.5) | 42 (17.7) | 17 (10.0) | .029 | 28 |

| Family history | 20 (5.2) | 9 (4.0) | 11 (6.9) | .209 | 52 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Systemic | 197 (45.5) | 105 (42.2) | 92 (50.0) | .106 | 2 |

| Gastrointestinal | 102 (23.5) | 41 (16.5) | 61 (32.8) | <.0001 | 0 |

Data are n (%) unless noted otherwise.

The age distribution was not normally distributed; the median (IQR) age at presentation of IBD was 24.0 (14.0) years. Over 60% presented between 17 and 40 years of age. Close to 20% of patients presented after 40 years of age. At presentation, the median age of the patients with UC was greater than that of the patients with CD (P=.0008).

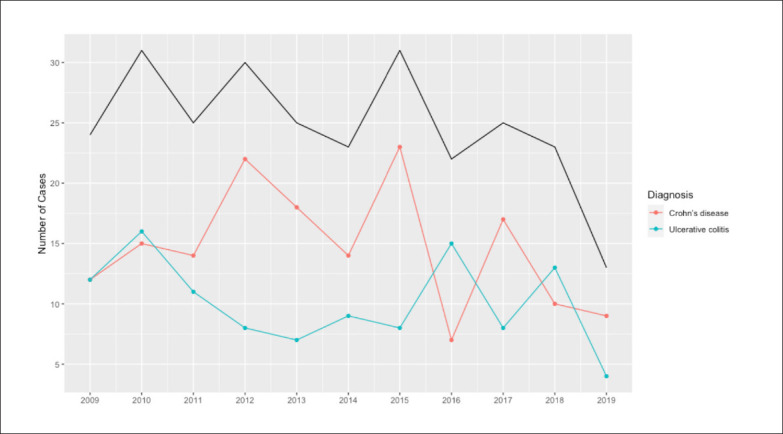

Approximately 5% reported having a family history of the same form of IBD. Of the patients with CD, 42 (17.7%) reported smoking cigarettes. Fewer patients with UC reported smoking (20, 5.2%). Systemic comorbidities were present in 197 (45.5%) patients and other gastrointestinal comorbidities were diagnosed in 102 (23.5%) patients (Table 1). Despite a fluctuation in the total number of patients diagnosed each year, the overall incidence of IBD seemed to plateau throughout the period of interest (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The annual incidence of inflammatory bowel disease from 2009 to 2019 (black line=total cases).

While the BMI of 145 patients (35.4%) was normal (18.5-24.9), 79 (18%) were underweight (BMI <18.5) and 117 (30%) were overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9). Seventy-four (18%) patients were obese (BMI >30). The BMI of the patients with CD and UC was not significantly different (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Body mass index category of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (n=435, ulcerative colitis: black, Crohn's disease: blue).

Gastrointestinal complications were more common in CD than in UC (P<.0001) (Table 2). The colon was involved in 152 patients (64.4%) with CD. Joint manifestations (i.e., arthritis and arthralgia) developed in 55 (13%) patients with IBD; the association of IBD with arthralgia was significant (10.9%; P=.0034) (Table 3). Colorectal cancer (the most common malignancy) was diagnosed in 14 (3.2%) patients with IBD. Of systemic comorbidities, endocrine disorders (mainly diabetes) were the most common (n=73, 16.8%) (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 2.

Gastrointestinal complications and malignancies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease

| Specific complication | Overall | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | P value | Missing data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal complications | 248 (61.4) | 199 (82.6) | 49 (30.1) | <0001 | 35 |

| Fistula | 150 (37.5) | 141 (59) | 9 (5.6) | <0001 | 35 |

| Strictures | 103 (25.7) | 97 (40.6) | 6 (3.7) | <0001 | 34 |

| Abscess | 89 (22.3) | 78 (32.6) | 11 (6.8) | <0001 | 35 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 58 (14.5) | 49 (20.5) | 9 (5.6) | <0001 | 34 |

| Perforation | 20 (5) | 17 (7.1) | 3 (1.9) | .0190 | 35 |

| Polyps | 18 (4.5) | 9 (3.8) | 9 (5.6) | .4008 | 35 |

| Adhesions | 17 (4.2) | 15 (6.3) | 2 (1.2) | .0202 | 34 |

| Anal fissure | 16 (4) | 13 (5.4) | 3 (1.9) | .1160 | 34 |

| Toxic megacolon | 2 (0.5) | 0 | 2 (1.2) | .1626 | 34 |

| Cyst | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | .4040 | 34 |

| Colon involvement in Crohn's disease | 152 (34.9) | 152 (64.4) | NA | NA | 13 |

| Gastrointestinal malignancy | |||||

| Gastric cancer | 4 (1.0) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.9) | .3076 | 34 |

| Colorectal cancer | 14 (3.2) | 9 (3.6) | 5 (2.7) | .5881 | 22 |

Data are n (%).

Table 3.

Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease.

| Specific manifestation | Overall | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | P value | Missing data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraintestinal manifestation | ||||||

| Hepatobiliary | Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 18 (4.1) | 9 (4.8) | 9 (3.6) | .5259 | 0 |

| Ocular | Eye manifestations | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | .999 | 34 |

| Episcleritis | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | .999 | 34 | |

| Conjunctivitis | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | .4040 | 34 | |

| Skin | Erythema nodosum | 5 (1.3) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.9) | .3975 | 34 |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgia | 45 (10.9) | 17 (7.1) | 28 (16.2) | .0034 | 22 |

| Arthritis | 13 (3) | 7 (2.8) | 6 (3.2) | .7940 | 1 | |

| Back pain | 36 (9) | 19 (8) | 17 (10.5) | .3891 | 35 | |

| Other | Unspecified ulcerc | 27 (6.8) | 14 (5.9) | 13 (8.0) | 13 (8.0) | 35 |

| Periodontitis | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | .999 | 35 | |

| Bronchiolitis | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | .999 | 34 |

Data are n (%).

Table 4.

Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

| Overall | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | P value | Missing data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal comorbidities | 102 (23.5) | 41 (16.5) | 61 (32.8) | <.0001 | 0 |

| Liver disease | 35 (8.1) | 14 (5.6) | 21 (11.3) | .0315 | 0 |

| Hepatitis | 19 (4.4) | 7 (2.8) | 12 (6.5) | .0661 | 0 |

| Infectious | 34 (7.8) | 18 (7.2) | 16 (8.6) | .5976 | 0 |

| Clostridium difficile | 11 (2.5) | 4 (1.6) | 7 (3.8) | .2176 | 0 |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | 9 (2.1) | 6 (2.4) | 3 (1.6) | .7385 | 0 |

| Intestinal tuberculosis | 6 (1.4) | 6 (2.4) | 0 | .0401 | 0 |

| Pancreatobiliary (gallbladder, biliary tract and pancreas) | 27 (6.2) | 9 (3.6) | 18 (9.7) | .0095 | 0 |

| Autoimmune | 14 (3.2) | 2 (0.8) | 12 (6.5) | .0014 | 0 |

| Celiac | 7 (1.6) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (3.2) | .0456 | 0 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 13 (3) | 4 (1.6) | 9 (4.8) | .0839 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal malignancy | 10 (2.3) | 3 (1.2) | 7 (3.8) | .0192 | 2 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 9 (2.1) | 4 (1.6) | 5 (2.7) | .5060 | 0 |

| Other gastrointestinal comorbidities | 7 (1.6) | 4 (1.6) | 3 (1.6) | .999 | 0 |

| Diverticular | 4 (1) | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | .6390 | 0 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | .999 | 0 |

Data are n (%).

Table 5.

Systemic comorbidities in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

| Overall | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | P value | Missing data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic Comorbidities | 197 (45.5) | 105 (42.2) | 92 (50.0) | .1057 | 2 |

| Endocrine | 73 (16.8) | 25 (10.0) | 48 (25.95) | <.0001 | 1 |

| Diabetes | 52 (12) | 12 (4.8) | 40 (21.6) | <.0001 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular | 70 (16.1) | 31 (12.5) | 39 (21.1) | .0156 | 1 |

| Hypertension | 47 (10.8) | 19 (7.6) | 28 (15.1) | .0128 | 1 |

| Respiratory | 28 (6.5) | 15 (6.02) | 13 (7.0) | .6741 | 1 |

| Musculoskeletal | 28 (6.5) | 12 (4.9) | 16 (8.7) | .1133 | 3 |

| Renal | 25 (5.9) | 12 (4.8) | 13 (7.0) | .3290 | 1 |

| Psychological | 25 (5.8) | 12 (4.8) | 13 (7.0) | .3290 | 1 |

| Dyslipidemia | 25 (5.8) | 9 (3.6) | 16 (8.7) | .0260 | 1 |

| Hematological | 23 (5.3) | 12 (4.8) | 11 (6) | .6044 | 1 |

| Non-gastrointestinal infectious | 26 (6) | 17 (6.8) | 9 (4.9) | .3942 | 1 |

| Non-gastrointestinal malignancy | 13 (3) | 3 (1.2) | 10 (5.4) | .0192 | 2 |

| Non-gastrointestinal autoimmune | 11 (2.5) | 8 (3.2) | 3 (1.6) | .3667 | 1 |

Data are n (%).

Gastrointestinal complications were higher in men (CD: P=.0251; UC: P=.0231), and patients with other GI comorbidities (CD: P=.0164; UC: P=.0015) (Tables 6 and 7). Patients with CD who had GI complications were more likely to be treated with biological agents than those who did not have GI complications (P=.0002). In CD, perianal symptoms were associated with an increased risk of surgical intervention (P=.0119). In UC, extraintestinal manifestations were associated with an increased risk of developing GI complications (P<.0001) and the need for surgical intervention (P=.0509) (Table 7). The higher operation rate in smokers with UC did not reach statistical significance (P=.0575). Corticosteroids were more frequently used to treat patients with UC (79, 45.4%) than CD (70, 29.0%) (Table 8). Biological agents were used to treat 212 patients (87%) with CD and 102 patients (57%) with UC. Surgical interventions were more commonly required to treat the GI complications of CD (Table 9).

Table 6.

Association between risk factors and outcomes of gastrointestinal complications and operations in Crohn's disease.

| Gastrointestinal complications | Surgery | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Yes | P value | Missing | Total | Yes | P value | Missing data | |

| Age at presentation | ||||||||

| <16 years | 54 (22.4) | 42 (77.8) | .5787 | 8 | 56 (23) | 29 (51.8). | 3023 | 5 |

| 17-40 years | 169 (70.1) | 142 (84) | 169 (69.3) | 82 (48.5) | ||||

| > 40 years | 18 (7.5) | 15 (83.3) | 19 (7.8) | 6 (31.6) | ||||

| Disease burden | ||||||||

| Systemic comorbidities | 102 (42.3) | 80 (78.4) | .1466 | 8 | 104 (42.6) | 54 (51.9) | .2844 | 5 |

| Gastrointestinal comorbidities | 39 (16.2) | 27 (69.2) | .0164 | 8 | 40 (16.4) | 16 (40) | .2710 | 5 |

| Extensive disease | 126 (55) | 108 (85.7) | .3947 | 20 | 125 (54.1) | 63 (50.4) | .7290 | 18 |

| Perianal symptoms | 30 (12.8) | 25 (83.3) | .8951 | 15 | 30 (12.7) | 8 (26.7) | .0119 | 12 |

| Extraintestinal manifestation | 39 (16.3) | 32 (82.1) | .8245 | 10 | 39 (16.5) | 17 (43.6) | .4642 | 12 |

| Family history | 9 (4.1) | 7 (77.8) | .6504 | 30 | 9 (4) | 5 (55.6) | .7471 | 27 |

| Smoking | 41 (17.8) | 36 (87.8) | .4106 | 19 | 42 (17.9) | 24 (57.1) | .2404 | 14 |

| Treatment | ||||||||

| Biological treatment | 209 (87.8) | 180 (86.1) | .0002 | 11 | 209 (87.8) | 103 (49.3) | .2525 | 11 |

| Steroid treatment | 68 (28.6) | 53 (77.9) | .2118 | 11 | 70 (29.4) | 31 (44.3) | .4713 | 11 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 95 (39.4) | 72 (75.8) | .0251 | 8 | 96 (39.3) | 42 (43.8) | .2901 | 5 |

| Male | 146 (60.6) | 127 (87) | 148 (60.7) | 75 (50.7) | ||||

Data are n (%).

Table 7.

Association between risk factors and outcomes of gastrointestinal complications and operations in ulcerative colitis.

| Gastrointestinal complications | Surgery | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Yes | P value | Missing | Total | Yes | P value | Missing data | |

| Age at presentation | ||||||||

| 17-40 years | 97 (59.5) | 31 (32) | .2786 | 23 | 103 (60.2) | 21 (20.4) | .3796 | 15 |

| <16 years | 32 (19.6) | 6 (18.8) | 33 (19.3) | 4 (12.1) | ||||

| >40 years | 34 (20.9) | 12 (35.3) | 35 (20.5) | 9 (25.7) | ||||

| Disease burden | ||||||||

| Systemic comorbidities | 83 (51.6) | 28 (33.7) | .2619 | 25 | 83 (49.1) | 18 (21.7) | .4865 | 17 |

| Gastrointestinal comorbidities | 57 (35) | 26 (45.6) | .0015 | 23 | 60 (35.1) | 15 (25) | .2177 | 15 |

| Extensive disease | 33 (21.3) | 11 (33.3) | .8107 | 31 | 33 (20.1) | 8 (24.2) | .5778 | 22 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 47 (29.0) | 28 (59.6) | <.0001 | 24 | 49 (30.4) | 15 (30.6) | .0509 | 25 |

| Family History | 11 (7.5) | 1 (9.1) | .1762 | 39 | 11 (7.2) | 0 | .2177 | 34 |

| Smoking | 13 (8.3) | 4 (30.8) | .2434 | 30 | 13 (8.1) | 5 (38.5) | .0575 | 26 |

| Treatment | ||||||||

| Biological treatment | 93 (58.9) | 23 (24.7) | .1469 | 28 | 99 (59.3) | 13 (13.1) | .0294 | 19 |

| Steroid treatment | 73 (46.2) | 22 (30.1) | .7931 | 28 | 76 (45.5) | 16 (21.1) | .4495 | 19 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 82 (50.3) | 18 (22) | .0231 | 23 | 85 (49.7) | 13 (15.3) | .1350 | 15 |

| Male | 81 (49.7) | 31 (38.3) | 86 (50.3) | 21 (24.4) | ||||

Data are n (%).

Table 8.

Medications in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.a

| Overall | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-ASA | 297 (71.6) | 141 (58.5) | 156 (89.7) | <.0001 |

| Azathioprine | 252 (60.7) | 164 (68.0) | 88 (50.6) | .0003 |

| Corticosteroid | 149 (35.9) | 70 (29.0) | 79 (45.4) | .0006 |

| Infliximab | 124 (29.9) | 90 (37.3) | 34 (19.5) | <.0001 |

| Adalimumab | 93 (22.4) | 76 (31.5) | 17 (9.8) | <.0001 |

| Vedolizumab | 28 (6.8) | 17 (7.1) | 11 (6.3) | .7692 |

| Omeprazole | 17 (4.1) | 13 (5.4) | 4 (2.3) | .1374 |

| Ustekinumab | 14 (3.4) | 12 (5) | 2 (1.2) | .0502 |

| Methotrexate | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | .4193 |

Data are n (%).

The medication history of 20 patients was not available.

Table 9.

Surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

| Overall | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | P value | Missing data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery (overall) | 192 (46.3) | 151 (62.4) | 41 (23.8) | <.0001 | 30 |

| Adhesiolysis | 10 (2.5) | 8 (3.4) | 2 (1.2) | .2050 | 31 |

| Stricturoplasty | 4 (1) | 4 (1.7) | 0 | .1445 | 31 |

| Abscess drainage | 43 (10.6) | 40 (17) | 3 (1.8) | <.0001 | 31 |

| Fistula repair | 32 (7.9) | 28 (11.9) | 4 (2.4) | .0003 | 31 |

| Partial colectomy | 22 (5.5) | 18 (7.6) | 4 (2.4) | .0253 | 31 |

| Right hemicolectomy | 28 (6.9) | 27 (11.4) | 1 (0.6) | <.0001 | 31 |

| Total colectomy | 15 (3.7) | 2 (0.9) | 13 (7.7) | .0006 | 31 |

| Proctocolectomy | 19 (4.7) | 2 (0.9) | 17 (10.12) | <.0001 | 31 |

| Ileocaecal resection | 49 (12.1) | 48 (20.3) | 1 (0.60) | <.0001 | 31 |

| Small bowel resection | 53 (13.1) | 52 (22.0) | 1 (0.6) | <.0001 | 31 |

Data are n (%).

DISCUSSION

In the West, the incidences of UC and CD are thought to be plateauing.10 The increasing incidence of IBD in the present cohort suggests that IBD may previously have been under diagnosed or misdiagnosed. However, the literature on the epidemiology of IBD in Saudi Arabia is inconsistent. The reported incidence has varied between 8 and 74 cases per year.9 This may be because most of the data are derived from single center studies. A national registry would greatly increase the accuracy of the data on the epidemiology of IBD in Saudi Arabia.

The incidence of IBD is higher in women worldwide.11 In the present study, a male predominance was found in CD, but the sex distribution of UC was equal. A male predominance has previously been reported in many Asian countries (including Saudi Arabia).12,13

A retrospective study in Saudi Arabia reported a higher prevalence of CD in men but UC was more common in women.9 The factors which influence the gender distribution of IBD are complex and multifactorial. There are biological and non-biological factors. Biological factors include select gender-specific genes and hormonal differences.13,14 Non-biological factors include age, geographical issues and access to health care.13,14

The prevalence of obesity in the general population in Saudi Arabia is high. Seventy percent of the population is either overweight or obese.15 It has been reported that the rate of obesity is increasing in parallel with IBD worldwide.16 Indeed, nearly half of the present cohort were either overweight or obese (Figure 2). Few studies have investigated the relationship between obesity and IBD. The treatment of IBD may increase the risk of obesity. The use of steroids is clearly relevant. One year of corticosteroid therapy can increase body weight by more than 10 kg.16 Biological agents may also increase weight, albeit to a lesser degree, as does the cessation of smoking.16,17 Other risk factors must be identified and prevented to mitigate the risk of obesity in this cohort.

Extraintestinal manifestations of IBD cause significant morbidity and mortality, affecting quality of life. Extraintestinal manifestations were diagnosed in 133 (31%) patients of the present cohort. The joints were involved (e.g., arthritis and arthralgia) in 55 (13%) patients of this cohort. These were the most common extraintestinal manifestations and were more often associated with UC. Previous studies have attributed this to the increased use of steroids in these patients.18 This hypothesis is supported by the findings of the present study. The prevalence of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) was 4% in the present study. An earlier study from Canada reported that 5% of patients with UC had PSC.19 The risk of colorectal carcinoma is increased ten-fold in patients with IBD who develop PSC.20,21 Thus, it is important to consider investigation for PSC during the follow-up of patients with IBD.22,23

The prevalence of psychological disorders which included depression and anxiety in our cohort was low (25, 6%) in comparison to other studies.24,25 Psychological issues may have been underdiagnosed because of the stigma associated with psychiatric diseases and the limited time available for communication between patients and physicians in the outpatient setting.26,27 In contrast to previous reports, neither smoking nor family history of IBD were associated with worse outcomes in the present study (P>.05).28 Cigarette smoking is a culturally sensitive topic. It may have been underreported.

Consistent with previous reports, male sex was associated with a higher incidence of GI complications in both CD and UC. However, this did not translate into an increased rate of surgery.14 In patients with UC, extraintestinal manifestations were associated with increased complications and surgery rates. This has been reported previously.29 Considering the associated morbidity and the negative impact on patients’ prognosis and quality of life, the early identification and treatment of the extraintestinal manifestations of IBD are vital.

The use of biological agents is associated with high rates of clinical and histological remission.30 In our cohort, 88% of patients with CD received biological therapy. This reflects the widespread adoption of the top-down strategy at our institution. This approach is based on the theory that the early introduction of biological therapy can reduce the risk of complications in the long term.31 In the present study, the patients with UC who received biological treatment required less surgical intervention. Only 37% of the patients with CD and 10% of the patients with UC required surgical intervention. The need for surgical intervention was significantly less in our cohort than that reported in a previous study from Saudi Arabia published in 2009.9 This may reflect improved control of IBD in the patients in our cohort who received biological treatment.

This large retrospective study of patients managed at a single center over the last decade has some limitations. Electronic medical records were only available from January 2016 so paper-based files were used to collect data prior to 2016. Some data (e.g., fecal calprotectin) were not available in the paper charts. Some patients were diagnosed and/or had follow-up in other hospitals. The data available for these patients were somewhat limited. Furthermore, data on fistulas were collected without differentiation between abdominal and perianal fistulae. This is because the precise nature and location of fistulae was rarely documented in the patients’ medical records.

In conclusion, the number of patients diagnosed with IBD at our institution per annum seems to have plateaued in the last decade. Crohn's disease was diagnosed more frequently than UC. IBD has a male preponderance and mainly affects people in their second and third decade. Smoking and a family history of IBD were not associated with worse outcomes. Joint involvement was the most common extraintestinal manifestation. The prevalence of PSC and psychological disorders were relatively low. Our observations suggest a significant decrease in the need for surgical intervention in patients with UC who received biological treatment. This is likely to reflect an improvement in the treatment of IBD in Saudi Arabia. However, almost half of the patients with IBD were either overweight or obese.

Funding Statement

Funding: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of America. The Facts About Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2014;2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. Mechanism of disease - review article. NEJM. 2009;361:2066-2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2017 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:17-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390:2769-2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlhamer JM, Zammitti EP, Ward BW, Wheaton AG, Croft JB. Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years — United States, 2015. MMWR. 2016;65;1166-1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdulla M, Al Saeed M, Fardan RH, Alalwan HF, Ali Almosawi ZS, Almahroos AF, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in Bahrain: single-center experience. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2017;10:133-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butt MT, Bener A, Al-Kaabi S, Yakoub R. Clinical characteristics of Crohn s disease in Qatar. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:1796-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khawaja AQ, Sawan AS. Inflammatory bowel disease in the Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:537-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fadda MA, Peedikayil MC, Kagevi I, Kahtani KA, Ben AA, Al HI, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in Saudi Arabia: a hospital-based clinical study of 312 patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:276-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mak WY, Zhao M, Ng SC, Burisch J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East meets west. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:380-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piovani D, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Bonovas S. Inflammatory bowel disease: estimates from the global burden of disease 2017 study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:261-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng SC. Emerging Trends of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Asia. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2016;12:193-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brant SR, Nguyen GC. Is there a gender difference in the prevalence of Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis? Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2008;14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rustgi SD, Kayal M, Shah SC. Sex-based differences in inflammatory bowel diseases: a review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820915043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.M Alqarni SS. A Review of Prevalence of Obesity in Saudi Arabia. J Obes Eat Disord. 2016;02. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh S, Dulai PS, Zarrinpar A, Ramamoorthy S, Sandborn WJ. Obesity in IBD: epidemiology, pathogenesis, disease course and treatment outcomes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:110-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulgund A, Stein D. Is Biologic Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Contributing to the Obesity Epidemic? Just Weight One Year. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:3420-3421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bon L, Scharl S, Vavricka S, Rogler G, Fournier N, Pittet V, et al. (2019). Association of IBD specific treatment and prevalence of pain in the Swiss IBD cohort study. PLoS ONE, 14(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan GG, Laupland KB, Butzner D, Urbanski SJ, Lee SS. The burden of large and small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis in adults and children: a population-based analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergquist A, Ekbom A, Olsson R, Kornfeldt D, Lööf L, Danielsson A, et al. Hepatic and extrahepatic malignancies in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2002;36:321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fevery J, Verslype C, Lai G, Aerts R, Van Steenbergen W. Incidence, diagnosis, and therapy of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3123-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talwalkar JA, Lindor KD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:62-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loftus EV Jr, Harewood GC, Loftus CG, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, et al. PSC-IBD: a unique form of inflammatory bowel disease associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 2005;54:91-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuller-Thomson E, Sulman J. Depression and inflammatory bowel disease: findings from two nationally representative Canadian surveys. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:697-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iglesias M, Barreiro de Acosta M, Vázquez I, Figueiras A, Nieto L, Lorenzo A, et al. psychological impact of Crohn's disease on patients in remission: anxiety and depression risks. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas : organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Patologia Digestiva. 2009;101; 249-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taft TH, Keefer L. A systematic review of disease-related stigmatization in patients living with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:49-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taft TH, Bedell A, Naftaly J, Keefer L. Stigmatization toward irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease in an online cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicolaides S, Vasudevan A, Long T, van Langenberg D. The impact of tobacco smoking on treatment choice and efficacy in inflammatory bowel disease. Intest Res. 2021;19:158-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connor M. Ulcerative Colitis-Epidemiology, Pathogenesis and Complication. 14th Ed. Ireland, South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molander P, Kemppainen H, Ilus T, & Sipponen T. (2020). Long-term deep remission during maintenance therapy with biological agents in inflammatory bowel diseases. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 55(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao R, Hu PJ. The Future of IBD Therapy: Where Are We and Where Should We Go Next? Dig Dis. 2016;34:175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]