Abstract

Objective

To investigate the negative predictive value (NPV) of musculoskeletal US (MSUS) in arthralgia patients at risk for developing inflammatory arthritis.

Methods

An MSUS examination of hands and feet was performed in arthralgia patients at risk for inflammatory arthritis in four independent cohorts. Patients were followed for one-year on the development of inflammatory arthritis. Subclinical synovitis was defined as greyscale ≥2 and/or power Doppler ≥1. NPVs were determined and compared with the prior risks of not developing inflammatory arthritis. Outcomes were pooled using meta-analyses and meta-regression analyses. In sensitivity analyses, MSUS imaging of tender joints only (rather than the full US protocol) was analysed and ACPA stratification applied.

Results

After 1 year 78, 82, 77 and 72% of patients in the four cohorts did not develop inflammatory arthritis. The NPV of a negative US was 86, 85, 82 and 90%, respectively. The meta-analysis showed a pooled non-inflammatory arthritis prevalence of 79% (95% CI 75%, 83%) and a pooled NPV of 86% (95% CI 81, 89%). Imaging tender joints only (as generally done in clinical practice) and ACPA stratification showed similar results.

Conclusion

A negative US result in arthralgia has a high NPV for not developing inflammatory arthritis, which is mainly due to the high a priori risk of not developing inflammatory arthritis. The added value of a negative US (<10% increase) was limited.

Keywords: arthralgia, inflammatory arthritis, ultrasonography, outcome assessment healthcare, power Doppler, RA

Rheumatology key messages.

Meta-analysis showed a pooled a priori non-inflammatory arthritis risk of 79% (95% CI 75%, 83%) and negative predictive value (NPV) of 86% (95% CI 81, 89%).

The high a priori risk of not developing inflammatory arthritis largely explains the high NPV.

A negative musculoskeletal US result has limited added value in excluding progression to inflammatory arthritis in 1 year.

Introduction

Multiple studies have aimed to detect biomarkers that can help identify arthralgia patients that will develop RA. Recently, it was agreed that autoantibodies (especially ACPA), clinical symptoms and imaging-detected subclinical inflammation are important predictors [1]. Although evidence-based guidelines for the management of arthralgia patients are still absent, musculoskeletal US (MSUS) is often used in clinical practice to guide management decisions. A recent survey from the UK demonstrated that 82% of the consulted rheumatologists used imaging (mostly MSUS) to guide the management of ACPA+ at risk individuals without clinical synovitis. Furthermore, it was presented that up to 32% would directly discharge the patient if no subclinical inflammation was found on MSUS [2]. This suggests that the absence of imaging-detected subclinical synovitis is increasingly used in daily practice to exclude arthralgia patients from further follow-up. To date, studies on the prognostic value of MSUS in arthralgia focused on the positive predictive value of subclinical inflammation (especially power Doppler) in predicting the development of inflammatory arthritis or RA development [3–7]. Evidence on the value of a negative MSUS in ruling out future inflammatory arthritis or RA development in arthralgia patients (the negative predictive value, NPV) is mostly absent. This prompted us to perform the present study.

According to the rules of Bayes, predictive values are highly dependent on the prior risk of developing the disease [8]. The NPV, therefore, is strongly related to the prior risk of not getting inflammatory arthritis, which is quite considerable in arthralgia patients. Furthermore, a discrepancy between research and daily clinical practice is that imaging protocols in pre-RA research consist of comprehensive imaging protocols systematically evaluating the majority of small joints, whereas in daily practice only symptomatic joints are imaged. Although studies focused on identifying a limited joint-set to improve MSUS implementation in daily practice, no consensus has been reached [9–11]. Comparing an MSUS of all small joints or only symptomatic joints, to exclude future inflammatory arthritis development, has never been explored.

Therefore, our aim was to determine the added value of a negative MSUS for subclinical synovitis/tenosynovitis in excluding inflammatory arthritis development, using the full US protocol or only the symptomatic joints, in four cohorts with arthralgia patients at risk for RA, comprising both ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative arthralgia patients.

Methods

Cohorts

We studied arthralgia patients at risk for inflammatory arthritis development in four independent Dutch arthralgia cohorts. All patients underwent MSUS at baseline and were followed for inflammatory arthritis development for 1 year. Details of each cohort, including imaging protocol, are presented in the supplementary material available at Rheumatology online [12–15].

Briefly, cohort 1 is the SONAR study, a multicentre observational inflammatory arthralgia cohort. At baseline a bilateral MSUS examination was performed of the wrists, MCP joints 2–5, PIP joints 2–5 and MTP joints 2–5. To minimize intervariability, US examiners followed a standardized scanning protocol regarding acquisition and scoring.

Cohort 2 is the ACPA or RF-positive arthralgia cohort from Amsterdam. A bilateral MSUS examination of wrists, MCP 2–3, PIP 2–3, and MTP 2–3 and 5 was performed at baseline [13]. MSUS examinations were all performed by a single radiologist [Marlies Meursinge Reynders (M.M.R.)] experienced in musculoskeletal US, who was blinded to the clinical data.

Cohort 3 is a selected group of patients from the clinically suspect arthralgia cohort from Leiden who also underwent an MSUS-examination. At baseline, a bilateral MSUS examination of the MCP 2–5, PIP 2–5, MTP 2–5 and the wrists was performed. The images of US were scored for greyscale (GS) synovitis (according to the EULAR-OMERACT scoring method) by two examiners (S.O. and Rosaline van den Berg (R.v.d.B.), with an intraclass correlation coefficient 0.92).

Cohort 4 is the clinically suspect arthralgia cohort from Rotterdam. This is a multicentre observational cohort. Again, at baseline a bilateral MSUS examination was made of the MCP 2–5, PIP 2–5, MTP 2–5 and the wrists. Two experienced examiners, blinded to the clinical data, performed the MSUS (C.R. and E.v.M., intraclass correlation coefficient 0.97).

In all cohorts, subclinical synovitis was defined as GS ≥2 and/or power Doppler >0, which was based on previous research with healthy controls [4].

The imaging examiners were blinded to the clinical details and the rheumatologists were blinded to the imaging results. At each visit, patients were seen by the research nurse, who performed the physical examination, including a 44-tender joint count (44-TJC).

Outcome

All cohorts had inflammatory arthritis development after 1 year as outcome, which had to be detected by the treating rheumatologist at physical examination. Importantly, no DMARD treatment (including glucocorticoid injections) was allowed in the arthralgia phase before inflammatory arthritis development.

Analysis

A priori risks of not developing inflammatory arthritis and NPVs for a negative MSUS were calculated per cohort. The a priori risk of not developing inflammatory arthritis was defined as the proportion of patients not developing inflammatory arthritis after 1 year of follow-up. The NPV was determined as the percentage of patients with a negative MSUS (no subclinical synovitis) who did not develop inflammatory arthritis. Thereafter prior risks and NPVs were pooled using meta-analyses (‘metaprop’, STATA V.16) and tested for statistical significance using meta-regression [16].

Sub-analyses

Analyses were repeated only taking into account the tender small joints rather than the full MSUS protocol, this analysis best reflects daily practice where often only symptomatic joints are imaged. Joint tenderness was derived from the 44-TJC. In addition, analyses of the full and shorter MSUS protocol were stratified for ACPA status (negative vs positive). Also, a more stringent definition of subclinical synovitis was used (GS >1 and power Doppler ≥1), hence a negative MSUS was defined as no power Doppler, regardless of the GS score. Finally, a broader definition for defining subclinical inflammation was used taking into account both subclinical synovitis (GS ≥2 and/or power Doppler ≥1) and/or subclinical tenosynovitis (GS ≥1 and/or power Doppler ≥1). Thus, a negative MSUS was defined as synovitis GS <2 and power Doppler <1(no subclinical synovitis) and tenosynovitis GS <1 and power Doppler <1 (no subclinical tenosynovitis).

Ethics

For cohort 1 (SONAR study), written informed consent was obtained from the participants according to the declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands (MEC-2010-353) and was assessed for feasibility by the local ethical bodies of Maasstad Hospital and Vlietland Hospital. For cohort 2 (Amsterdam cohort), signed informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to inclusion. This study was approved by the Slotervaart ethics committee (U/1740/0327). For cohort 3 (clinically suspect arthralgia cohort), patient consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the local medical ethics committee of Leiden University Medical Center. For cohort 4 (clinically suspect arthralgia Rotterdam), patient consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands (MEC-2017-028) and was assessed for feasibility by the local ethical bodies of Maasstad Hospital and IJsseland Hospital.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 166, 162, 40 and 43 patients were included in cohorts 1, 2, 3 and 4. Baseline characteristics are presented in supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online. Most patients were women, the median symptom duration was 29, 57, 21 and 23 weeks, respectively. In cohort 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively 22, 56, 23 and 26% of patients were ACPA positive (autoantibody positivity was a prerequisite for cohort 2). Of the included patients 64% (n = 106), 69% (n = 112), 43% (n = 17) and 49% (n = 21) had a negative MSUS at baseline.

Negative predictive value of US at baseline

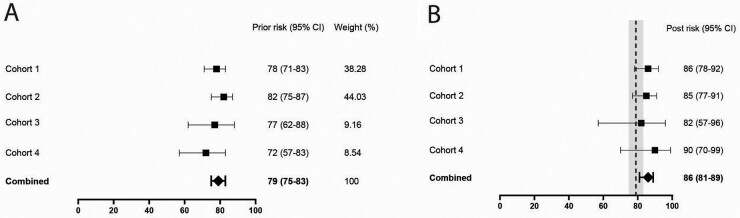

After 1 year the prior risk of not developing inflammatory arthritis was 78, 82, 77 and 72%. Of the patients with a negative MSUS at baseline, n = 91, n = 95, n = 14 and n = 19 did not develop inflammatory arthritis, corresponding to a NPV of 86, 85, 82 and 90% (Fig. 1A). Meta-analysis showed a pooled apriori non-inflammatory arthritis risk of 79% (95% CI 75%, 83%) and NPV of 86% (95% CI 81, 89%) (Fig. 1). Thus, the added value of a negative MSUS on not developing inflammatory arthritis was 7% when pooling data from the four cohorts.

Fig. 1.

Full US protocol

Prior risks of not developing inflammatory arthritis (A) and negative predictive values of musculoskeletal US (B) in the four cohorts. For comparison, the pooled prior risk and confidence interval from A are depicted in the grey column in (B).

US only in the symptomatic joints

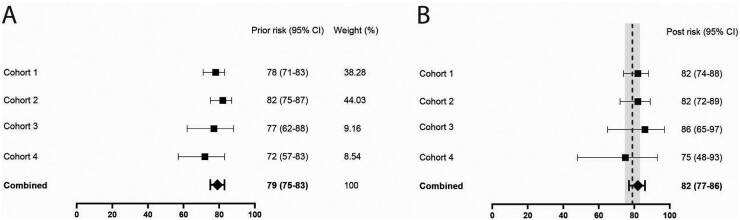

In clinical practice most often only tender joints are imaged. Analysing MSUS results from tender small joints in four cohorts revealed a pooled NPV of 82% (95% CI 77, 86%, Fig. 2), representing added value of 3% over the known apriori risk of 79%.

Fig. 2.

Short US protocol imaging only the tender small joints

Prior risks of not developing inflammatory arthritis (A) and negative predictive values of musculoskeletal US (B) in the four cohorts. For comparison, the pooled prior risk and confidence interval from A are depicted in the grey column in (B).

Analyses of ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative arthralgia separately

Stratification for ACPA showed a 67% (95% CI 57%, 77%) pooled prior risk of not developing inflammatory arthritis in ACPA positive patients. The pooled NPV was 76% (95% CI 65%, 85%). For ACPA-negative patients the pooled prior risk of not developing RA was 85% (95% CI 78%, 93%) and the pooled NPV 91% (95% CI 85%, 95%) (supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online). Assessing only the tender joints in ACPA-positive arthralgia showed a pooled prior risk of 67% and NPV of 71%. For ACPA-negative arthralgia this was 85% and 88%, respectively (supplementary Fig. S2, available at Rheumatology online).

Different US definitions

It was recently shown that especially the presence of power Doppler-positive synovitis, but also tenosynovitis, were predictive for the development of inflammatory arthritis in arthralgia patients [6, 17]. Therefore, two different MSUS definitions were analysed: a more stringent definition for test positivity (power Doppler >0 regardless of the GS score) and alternatively a broader definition (subclinical synovitis and/or tenosynovitis in GS/power Doppler). Similar findings regarding the prior and NPV values were obtained (supplementary Figs S3/S4, available at Rheumatology online).

All analyses showed overlapping 95% CI between prior risks and NPVs. None of the NPVs was significantly higher than the prior risk, as summarized in supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online.

Discussion

Risk stratification and decision making in arthralgia patients considered to be at risk of developing inflammatory arthritis or RA is challenging in clinical practice. Imaging is not only used to predict future development of inflammatory arthritis or RA, but is also increasingly used to identify patients that do not develop inflammatory arthritis and can be discharged from follow-up [2]. As scientific support for the latter was lacking, we performed an MSUS study in four cohorts. We indeed observed that a negative MSUS had a high NPV for not developing inflammatory arthritis (86%), however this was mainly due to the high apriori risk of not developing inflammatory arthritis. A negative MSUS increased risks of not developing inflammatory arthritis by 2–9% relative to the prior risk of not developing inflammatory arthritis.

Analyses were performed for a full MSUS protocol evaluating all small joints and scanning tender joints only. The added value of a negative MSUS was slightly higher when the full MSUS protocol was performed (range 6–9%), and lower when only symptomatic joints were imaged (range 2–4%). Previous research presented that subclinical inflammation is present in joints without tenderness [18, 19], which could explain the difference in NPV between the full and short US protocol.

Analyses of ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative arthralgia patients separately, showed differences in prior risks of not getting inflammatory arthritis, but the ‘added value’ of a negative MSUS was roughly similar. In daily practice, MSUS is mostly performed in symptomatic joints in ACPA-positive arthralgia, and in this setting a negative US added only 4% on not developing inflammatory arthritis, relative to the prior risk of not developing inflammatory arthritis.

Different clinical cohorts may recruit patients at different stages in the arthritis development continuum, therefore representing a heterogeneous population. Although the inclusion criteria of the cohorts were somewhat different, the results on the other hand were similar. This strengthened the validity and suggests generalizability of the results to MSUS in different places.

Some limitations should also be noted. Different machines and sonographers were used for the MSUS examinations. Nonetheless, the results were comparable and different machines are also used in daily clinical practice. Secondly, all analysis were univariate, though we did stratify for ACPA status, MSUS results must ideally be interpreted in combination with other predictive factors (e.g. clinical, genetic and serological data). Finally, the follow-up period might be considered short. On the other hand, previous studies in clinical suspect arthralgia already showed that most patients developed inflammatory arthritis within 6 months and that the conversion rate to inflammatory arthritis after 1 year of follow-up is low [15].

In conclusion, MSUS in arthralgia patients can be performed to identify subclinical inflammation in patients with an increased risk for RA. The accuracy of a positive MSUS is presented in different studies [4, 6, 20]. We showed that a negative MSUS is associated with a high-risk of not getting inflammatory arthritis. However, as the prior risk was already high and a negative MSUS result contributed <10%, performing MSUS might therefore not be necessary for the purpose of ruling out future inflammatory arthritis development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all participating patients for their contributions to the studies.

All authors contributed to the conception or design of the study. C.R., G.F., A.H.M.v.d.H.-v.M., E.v.M. and D.v.S. contributed to the data acquisition. C.R., G.F. and M.V. performed data analyses. C.R., P.H.P.d.J. and A.H.M.v.d.H.-v.M. wrote the first version of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the paper and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Funding: The research leading to these results has received funding from: Dutch Arthritis Foundation (SONAR cohort, clinically suspect arthralgia Leiden cohort, Amsterdam cohort, clinically suspect arthralgia Rotterdam), The European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (starting grant, agreement no. 714312) (clinically suspect arthralgia Leiden cohort).

Disclosure statement: R.F.v.V. has the following disclosures: research support (institutional grants): Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Lilly, Union Chimique Belge (UCB); support for educational programs (institutional grants): Pfizer, Roche; consultancy, for which institutional and/or personal honoraria were received: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Biotest, BMS, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, Sanofi, Servier, UCB, Vielabio; speaker, for which institutional and/or personal honoraria were received: AbbVie, Galapagos, GSK, Janssen, Pfizer, UCB. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Patient and public involvement: Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Contributor Information

Cleo Rogier, Department of Rheumatology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam.

Giulia Frazzei, Amsterdam Rheumatology and Immunology Center, Department of Rheumatology, Reade, Amsterdam.

Marion C Kortekaas, Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), Leiden, The Netherlands.

Marloes Verstappen, Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), Leiden, The Netherlands.

Sarah Ohrndorf, Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), Leiden, The Netherlands; Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

Elise van Mulligen, Department of Rheumatology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam; Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), Leiden, The Netherlands.

Ronald F van Vollenhoven, Amsterdam Rheumatology and Immunology Center, Department of Rheumatology, Reade, Amsterdam.

Dirkjan van Schaardenburg, Amsterdam Rheumatology and Immunology Center, Department of Rheumatology, Reade, Amsterdam.

Pascal H P de Jong, Department of Rheumatology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam.

Annette H M van der Helm-van Mil, Department of Rheumatology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam; Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), Leiden, The Netherlands.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

References

- 1. Mankia K, Siddle HJ, Kerschbaumer A. et al. Eular points to consider for conducting clinical trials and observational studies in individuals at risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1286–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mankia K, Briggs C, Emery P.. How are rheumatologists managing anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies-positive patients who do not have arthritis? J Rheumatol 2020;47:305–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Di Matteo A, Mankia K, Azukizawa M. et al. The role of musculoskeletal ultrasound in the rheumatoid arthritis continuum. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2020;22:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Duquenne L, Chowdhury R, Mankia K. et al. The role of ultrasound across the inflammatory arthritis continuum: focus on “at-risk” individuals. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:587827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van den Berg R, Ohrndorf S, Kortekaas MC. et al. What is the value of musculoskeletal ultrasound in patients presenting with arthralgia to predict inflammatory arthritis development? A systematic literature review. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nam JL, Hensor EM, Hunt L. et al. Ultrasound findings predict progression to inflammatory arthritis in anti-CCP antibody-positive patients without clinical synovitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:2060–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rakieh C, Nam JL, Hunt L. et al. Predicting the development of clinical arthritis in anti-CCP positive individuals with non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective observational cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1659–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Puga JL, Krzywinski M, Altman N.. Bayes’ theorem. Nat Methods 2015;12:277–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Backhaus M, Ohrndorf S, Kellner H. et al. Evaluation of a novel 7-joint ultrasound score in daily rheumatologic practice: a pilot project. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naredo E, Rodríguez M, Campos C. et al. ; Ultrasound Group of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology. Validity, reproducibility, and responsiveness of a twelve-joint simplified power doppler ultrasonographic assessment of joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van de Stadt LA, Bos WH, Meursinge Reynders M. et al. The value of ultrasonography in predicting arthritis in auto-antibody positive arthralgia patients: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:R98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van der Ven M, van der Veer-Meerkerk M, Ten Cate DF. et al. Absence of ultrasound inflammation in patients presenting with arthralgia rules out the development of arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2017;19:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Beers-Tas MH, Blanken AB, Nielen MMJ. et al. The value of joint ultrasonography in predicting arthritis in seropositive patients with arthralgia: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohrndorf S, Boer AC, Boeters DM. et al. Do musculoskeletal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging identify synovitis and tenosynovitis at the same joints and tendons? A comparative study in early inflammatory arthritis and clinically suspect arthralgia. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Steenbergen HW, Mangnus L, Reijnierse M. et al. Clinical factors, anticitrullinated peptide antibodies and MRI-detected subclinical inflammation in relation to progression from clinically suspect arthralgia to arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1824–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M.. Metaprop: a stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health 2014;72:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matthijssen XME, Wouters F, Sidhu N. et al. Tenosynovitis has a high sensitivity for early ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative RA: a large cross-sectional MRI study. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:974–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gessl I, Popescu M, Schimpl V. et al. Role of joint damage, malalignment and inflammation in articular tenderness in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:884–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burgers LE, Ten Brinck RM, van der Helm-van Mil AHM.. Is joint pain in patients with arthralgia suspicious for progression to rheumatoid arthritis explained by subclinical inflammation? A cross-sectional MRI study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58:86–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rogier C, Wouters F, van Boheemen L. et al. Subclinical synovitis in arthralgia: how often does it result in clinical arthritis? Reflecting on starting points for disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:3872–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.