Abstract

Background

The expression of m6A-related genes and their significance in COVID-19 patients are still unknown.

Methods

The GSE177477 and GSE157103 datasets of the Gene Expression Omnibus were used to extract RNA-seq data. The expression of 26 m6A-related genes and immune cell infiltration in COVID-19 patients were analyzed. Finally, we built and validated a nomogram model to predict the risk of COVID-19 infection.

Results

There were significant differences in 11 m6A regulatory factors between patients with COVID-19 and healthy individuals. The classification of disease subtypes based on m6A-related gene levels can be distinguished. COVID-19 patients in GSE177477 were classified into two categories based on m6A-related genes. The patients in cluster A were all symptomatic, while those in cluster B were asymptomatic. A significant correlation was also found between immune cells and m6A-related genes. Finally, seven m6A-related disease-characteristic genes, HNRNPA2B1, ELAVL1, RBM15, RBM15B, YTHDC1, HNRNPC, and WTAP, were screened to construct a nomogram model for predicting risk. The calibration curve, decision curve analysis, and clinical impact curve analysis were used to show that the nomogram model was effective and had a high net efficacy for risk prediction.

Conclusions

m6A-related genes were correlated with immune cells. The nomogram model effectively predicted COVID-19 risk. Moreover, m6A-related genes may be associated with the presence or absence of symptoms in COVID-19 patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, N6-methyladenosine, Risk, Immune

1. Introduction

A wide range of clinical symptoms are caused by the Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) and are exceedingly variable, including asymptomatic cases, pneumonia, and severe hypoxia (Fung et al., 2020). In individuals with COVID-19, the elderly, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity may significantly increase the risk of hospitalization and mortality (Muniyappa and Gubbi, 2020). The mechanisms behind the disparities in illness risk and outcomes across various groups remain obscure. Globally, elucidating the underlying pathophysiology and finding therapeutic approaches to COVID-19 has become imperative.

Several post-transcriptional RNA modifications have been identified in eukaryotic cells. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is one of the most frequent modifications found across mammalian RNA transcripts and is common in messenger RNAs and some non-coding RNAs (Chen et al., 2020; Roundtree et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018). m6A is incorporated into mRNA and is reversibly regulated by writers (methyltransferases) and erasers (demethylases) through cyclic enzymatic activity. m6A modification affects many events in mRNA metabolism, including maturation, folding, export, localization, translation, and degradation (Frye et al., 2016; Meyer and Jaffrey, 2017).

Many studies have confirmed the presence of m6A modifications in viral RNA transcripts and the importance of these modifications to the regulation of the viral life cycle (Dimock and Stoltzfus, 1977; Gokhale et al., 2016; Kane and Beemon, 1985; Lichinchi et al., 2016a). A relationship between m6A regulatory factors and COVID-19 has been found. Gokhale et al. (Gokhale et al., 2016) found that deletion of METTL3 and METTL4 increases the production of infectious viral particles of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5A along with the HCV infection rate. In addition, silencing of METTL3 and METTL4 enhances the replication of the Zika virus (Lichinchi et al., 2016b). Recent studies have examined the dysregulation of m6A modification in host cells infected with SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, when SARS-CoV-2 infects host cells, m6A modification machinery is re-localized, and there is an increase in the cellular abundance of m6A (Liu et al., 2021). In addition, compared to healthy individuals, patients with severe COVID-19 exhibit a significant reduction in expression of the m6A writer gene METTL3 and inflammatory genes are upregulated in lung tissues (Li et al., 2021a). Moreover, downregulation of m6A-related genes has been observed in the blood leukocytes of COVID-19 patients (Qiu et al., 2021). In addition, RBM15 expression was upregulated and correlated with COVID-19 disease severity (Meng et al., 2021). Therefore, we speculated that m6A-related genes might play a key role in the infection process of SARS-CoV-2. Whether m6A-related genes are associated with disease risk requires further investigation.

In the present study, the expression levels of 26 m6A regulatory factors in COVID-19 patients and healthy individuals were analyzed. Differential gene expression levels in COVID-19 patients were used to classify patients. In addition, the differential expression of immune cells and the correlation between immune cells and m6A-related genes were analyzed. Finally, machine learning was used to screen disease-characteristic genes, which were then applied to construct a nomogram model to predict the risk of COVID-19.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample sources

RNA-seq data was obtained from the GSE177477 (Masood et al., 2021) and GES157103 (Overmyer et al., 2021) datasets of the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (Barrett et al., 2013), including data from 129 cases of patients with COVID-19 and 44 cases of healthy controls. There were 29 patients with COVID-19 in GSE177477. Eleven of the 29 patients were symptomatic while 18 were asymptomatic. The GSE157103 dataset included 100 COVID-19 patients and 26 healthy controls. As the data was from a publicly available GEO database, informed consent was guaranteed. R software (version 4.1.1) was used to analyze the expression of m6A-related genes.

2.2. Cluster analysis of patients with COVID-19

Sample clustering based to gene expression data is useful for the detection of disease subtypes. Partitioning Around Medoids (PAM) algorithm was used to construct a consensus matrix for patient grouping. Therefore, we conducted a cluster analysis of COVID-19-infected patients according to the levels of differentially expressed m6A-related genes, and then selected the optimal number of clusters for classification. Principal component analysis (PCA) was then performed to evaluate the effectiveness of the classification system. “ConsensusClusterPlus,” “limma,” “pheatmap,” “reshape2,” “ggpubr,” and “ggplot2” packages were used to perform classification and visualization.

Furthermore, m6A scores were evaluated for each patient. The m6A score is a score index based on the principal component analysis (PCA) algorithm, which combines the scores of patients' PC1 and PC2. According to the median, patients were divided into “m6A-score high” and “m6A-score low” groups.

2.3. The relationship between m6A-related genes and immune cells

Next, we analyzed the expression of 23 types of immune cells after clustering based on m6A-related gene expression. The correlation between m6A-related genes and immune cells has been previously studied. “GSEABase,” “limma,” “pheatmap,” “reshape2,” “ggpubr,” and “ggplot2” packages were applied to perform classification and visualization.

2.4. Construction and validation of the nomogram predictive model

First, machine learning, including random forest (RF) and support vector machine (SVM) classifiers, was applied to select disease-characteristic genes. Then, the accuracy of these two algorithms was evaluated according to the residual and reverse cumulative distributions of the residuals. An algorithm with higher accuracy was selected to further screen the characteristic genes. Additionally, the area under the ROC curve was used to measure the accuracy of the two algorithms.

Finally, the screened genes were used to establish a nomogram prediction model to evaluate disease risk. Validation analysis was performed using 1000 bootstrap resampling. A calibration curve was then drawn to measure the relationship between the nomogram model's prediction and actual risk. We assessed the net benefit using decision curve analysis (DCA) and measured the clinical usability using clinical impact curve analysis (CICA). The R software packages “rms” and “rmda” were applied to construct the model.

3. Results

3.1. Differential expression of m6A-related genes in COVID-19

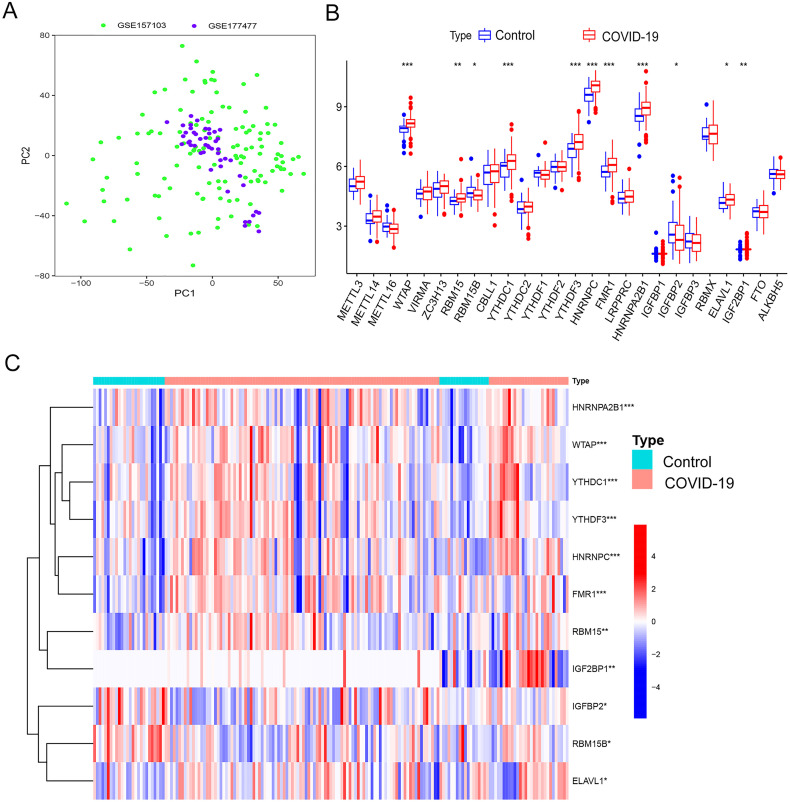

RNA-seq data was obtained from the GSE177477 and GES157103 datasets of the GEO database. PCA results showed that the batch effect was eliminated (Fig. 1A). We used data from 173 patients, including 129 with COVID-19 and 44 healthy subjects. We analyzed the differential expression of 26 m6A regulators in different populations, including 9 writers, 15 readers, and 2 erasers. As shown in Fig. 1B, there were significant differences in 11 regulatory factors between the two groups: WTAP, RBM15, RBM15B, YTHDC1, YTHDF3, HNRNPC, FMR1, HNRNPA2B1, IGFBP2, ELAVL1, and IGF2BP1. Furthermore, WTAP, RBM15, HNRNPC, YTHDC1, FMR1, HNRNPA2B1, ELAVL1, and YTHDF3 were significantly upregulated in COVID-19 patients, while RBM15B, IGFBP2, and IGF2BP1 were significantly down-regulated. The expression of these 11 m6A-related genes in all subjects is shown in Fig. 1C.

Fig. 1.

m6A-related gene expression levels. (A) PCA showed elimination of batch effects. (B)Differential expression of m6A-related genes between patients with COVID-19 and the control group. (C) Heat map of differential gene expression levels in each sample.

3.2. Cluster analysis

The best consensus matrix, k = 2, was obtained using the PAM algorithm (Fig. 2A). According to the expression of m6A-related genes, 129 patients with COVID-19 were divided into two categories: clusters A and B. The expression level of each m6A-related gene in each patient is shown in Fig. 2B. Significant differences was observed in the expression of m6A-related genes between clusters A and B (Fig. 2C). Finally, PCA results showed that clusters A and B could be distinguished according to m6A-related gene expression (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

COVID-19 patients were grouped into clusters based on the expression levels of m6A-related genes. (A) The best consensus matrix (k = 2). (B) Heat map of m6A-related gene expression in COVID-19 patients. (C) Differential expression in clusters A and B. (D) Principal component analysis indicated that clustering was effective.

Clustering of the 47 patients within the GSE177477 dataset alone revealed an interesting observation. The grouping obtained by clustering was consistent with that of the patients with or without concomitant symptoms. In other words, the patients in cluster A were all symptomatic, while those in cluster B were asymptomatic (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Supplementary Fig. 1.

COVID-19 patients in GSE 177477 were grouped into clusters based on the level of m6A-related genes. (A) the best consensus matrix k = 2. (B) Heat map of m6A-related gene expression in COVID-19 patients. (C) Differential expression in cluster A and B. (D) Principal component analysis indicated that clustering was effective.

3.3. The relationship between m6A-related genes and immune cells

Next, we assessed the differential expression of 23 types of immune cells in clusters A and B. Fig. 3A illustrates the significant differences between the two groups with respect to 11 types of immune cells. Eosinophils (p < 0.01), natural killer cells (p < 0.05), neutrophils (p < 0.001), and type 2 T helper cells (p < 0.05) were significantly up-regulated in cluster B. However, activated CD8 T cells (p < 0.001), CD56bright natural killer cells (p < 0.01), CD56dim natural killer cells (p < 0.001), MDSCs (p < 0.001), monocytes (p < 0.01), regulatory T cells (p < 0.05), and type 1 T helper cells (p < 0.01) were significantly up-regulated in cluster A.

Fig. 3.

The relationship between m6A-related gene expression levels and immune cells. (A) The expression of immune cells in different clusters. (B) The correlation between m6A-related gene expression levels and immune cells. (C) The expression of immune cells in high and low RBM15B gene expression groups.

The correlation between m6A and immune cells is shown in Fig. 3B. The gene RBM15B, which had a strong correlation, was selected for further analysis. Based on the RBM15B expression level, patients with COVID-19 were divided into two groups, high RBM15B expression and low RBM15B expression. Differences in immune cells were also compared between these two groups. Fourteen types of immune cells were significantly different between the RBM15B high expression and RBM15B low expression groups (Fig. 3C).

3.4. m6A score

We established a scoring system, the m6A-score, based on a composite score of m6A-related gene expression in COVID-19 patients. Each patient was assigned an m6A-score based on this analysis (Supplementary Table 1). The scores were compared between the different disease subtypes. The results indicated that the m6A score in m6A cluster B was higher than that in m6A cluster A (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

The m6A score and application of machine learning to screen disease signature genes. (A) m6A scores of clusters A and B. Residual (B) and reverse cumulative distribution of the residual (C) were used to compare the accuracy of RF and SVM algorithms. (D) RF and SVM algorithms were evaluated by ROC curves. (E) The optimal nTree was selected in the random forest analysis to screen disease-characteristic genes. (F) The importance score of the relevant gene was calculated.

3.5. RF and SVM algorithms for screening disease-feature genes

To examine the relationship between m6A-related genes and the disease risk of COVID-19 more accurately, we combined samples from two datasets, GSE177477 and GSE157103. The RF and SVM algorithms were used to screen the feature genes of the disease. We then compared the residual and reverse cumulative distributions of the residuals of these two algorithms. As shown in Fig. 4 B-C, regardless of the residual or reverse cumulative distribution of the residual, RF was better than SVM, which indicates that the RF algorithm is more accurate than the SVM algorithm. Furthermore, ROC curve analysis showed an AUC of 1 in RF and an AUC of 0.971 in SVM, which indicates that the screening of disease-characteristic genes was valid (Fig. 4D).

Then, a random forest algorithm with the nTree set to 500 was used to screen disease-characteristic genes, which revealed that the error was small and stable at an nTree of 188 (Fig. 4E). We then calculated the importance scores of 11 m6A-related genes. Finally, nine genes were screened based on an importance score of >5, including HNRNPC, WTAP, HNRNPA2B1, ELAVL1, RBM15, YTHDC1, YTHDF3, RBM15B, and FMR1 (Fig. 4F).

3.6. The nomogram prediction model

Based on the results of the random forest analysis and importance score, we selected seven genes to describe the impact of each gene on the risk of COVID-19 and set up a nomogram prediction model related to the disease (Fig. 5A). The seven m6A-related genes were HNRNPC, WTAP, HNRNPA2B2, ELAVL1, RBM15, YTHDC1, and RBM15B. The different expression levels of the seven genes were given corresponding scores. The total score could be used to predict the risk of COVID-19. In the risk prediction nomograms, YTHDC1 made the greatest contribution, suggesting that YTHDC1 was the most suitable for predicting the risk of disease infection. We then validated this model. The calibration curve showed good consistency between the predicted and observed results (Fig. 5B). DCA showed that the use of a nomogram model for predicting COVID-19 risk had a high net benefit (Fig. 5C). The CICA revealed that high-risk patients classified by the nomogram model had a high degree of coincidence with the actual positive patients (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Predictive models for the risk of COVID-19 patients. (A) The nomogram prediction model. (B) The calibration curve shows good consistency between the predicted results and the observed results. (C) Decision curve analysis shows a high net benefit. (D) Clinical impact curve analysis verifies the validity of the nomogram model.

4. Discussion

Despite advancements in vaccination, SARS-CoV-2 continues to cause severe acute respiratory syndrome and lung damage in a considerable number of patients. It is crucial for the host antiviral defense that the immune system responds to viruses invading the host cells by generating interferon (IFN), inflammatory cytokines, and chemokines. Nevertheless, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines can trigger cytokine storms in COVID-19 patients, leading to serious illnesses. SARS-CoV-2 is a member of the genus-Coronavirus, a positive-sense RNA virus (Lu et al., 2020). It has been revealed that m6A modifications are required to progress the RNA viral life cycle and the host cell's immune response (Dimock and Stoltzfus, 1977; Gokhale et al., 2016; Kane and Beemon, 1985; Lichinchi et al., 2016a). There is also evidence that SARS-CoV-2 genome translation to replication is regulated by the interaction between m6A-marked RNA and hnRNPA1 (Kumar et al., 2022).

Here, we analyzed m6A methylation modification in 129 COVID-19 patients and 44 healthy controls and found that eight genes, including WTAP, were significantly up-regulated in COVID-19, while three genes, including RBM15B, IGFBP2, and IGF2BP1, were significantly down-regulated. Changes in the expression of m6A-related genes indicate that the m6A methylome is aberrant in COVID-19 patients. A study on the Zika virus showed a decrease in the replication of the Zika virus when silencingm6A erasers, including FTO (Lichinchi et al., 2016b). WTAP participates in the m6A methyltransferase complex and m6A methylation modification by combining METTL3-METTL14 heterodimers (Fu et al., 2014). WTAP knockdown reduced methyl marks on m6A and decreased human Coronavirus OC43(HCoV-OC43) replication (Burgess et al., 2021). This evidence implies that a severe response may be due to uncontrollable virus replication. TGF-β controls the methylation of m6 A mRNA through SMAD2/3 interaction (Bertero et al., 2018). TGF-β was significantly different among groups with different disease states of COVID-19 (Ghazavi et al., 2021). Healthy controls do not exhibit any significant TGF-β1-expressing SARS-CoV-2-reactive Th cells (Ferreira-Gomes et al., 2021).

Next, according to the expression of m6A-related genes, COVID-19 patients were divided into two groups, cluster A and cluster B. Interestingly, the subgroup of GSE 177477 using the m6A-related gene cluster was the same as the group of patients with or without symptoms. This may be due to a deviation caused by an insufficient sample size, which is worthy of our attention. The transmission rate in asymptomatic patients is similar to that in symptomatic patients (Li et al., 2020). Our results provide an explanation for genetic effects on SARS-CoV-2 infection outcomes.

There was a significant difference in immune cells between clusters A and B in COVID-19 patients. Additionally, m6A is correlated with immune cells. A close association between m6A regulators and immune cell infiltration has been demonstrated in other studies (Cheng et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). Although it is not clear by what mechanism m6A-related genes regulate the immune response, this has provided us with a new perspective. It was found that depletion of METTL3 in host cells decreased the m6A level of SARS-CoV-2, further increased RIG-I binding, and enhanced the expression of downstream innate immune signaling pathways (Li et al., 2021a). Dendritic cells (DCs) with METTL3 silencing display immature properties, and prolong the survival of allografts (Wu et al., 2020). Deletion of METTL3 in T cells affects T cell differentiation and homeostatic expansion (Li et al., 2017). Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (hnRNPC) regulates neutrophil recruitment through its interaction with urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptors (uPARs) (Bhandary et al., 2009). Overexpression of HNRNPC in Parkinson's disease can inhibit the expression of inflammatory factors, such as IFN-β, IL-6, and TNF-α(Quan et al., 2021). Heterogeneous ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs), such as hnRNP-K can regulate macrophage recruitment and activation (Ostareck and Ostareck-Lederer, 2019). With the continuous increase in the number of COVID-19 infections, the study of the mechanisms of the disease immune response have become particularly important. Response characteristics are helpful for understanding pathogenesis, controlling infections and for developing vaccines. Cellular immunity caused by Coronavirus infections mainly involves antigen-presenting cells (e.g., macrophages) and T cells (Tang et al., 2020). Studies have shown that antigen presentation is inhibited in symptomatic COVID-19 patients (Masood et al., 2021). T cell responses can be detected in most COVID-19 patients (Braun et al., 2020; Grifoni et al., 2020; Thevarajan et al., 2020). T cell activation characterized by CD38 expression, can be used as a marker of the acute phase of COVID-19 (Sekine et al., 2020). Braun et al. found that peak reactive CD4 T cells were detected in 83% of COVID-19 patients and 35% of healthy controls (Braun et al., 2020). It is reasonable to speculate that there may be T cell cross-reactions which provide some protection against infection by SARS-CoV-2. This also helps to explain the different clinical outcomes of people infected with the virus. In severe COVID-19, sustained cytokine production and hyper-inflammation can be observed (Giamarellos-Bourboulis et al., 2020). Some studies have also found that plasma cell-like dendritic cells (pDCs) are rapidly consumed in severe COVID-19 patients (Laing et al., 2020).

Finally, seven disease-characteristic genes were screened using the random forest algorithm, including HNRNPA2B1, ELAVL1, RBM15, RBM15B, YTHDC1, HNRNPC, and WTAP. A nomogram prediction model based on these seven m6A-related genes was established to assess the risk of COVID-19. DCA and CICA further confirmed that the accuracy of the risk-scoring model. Some reports have established risk-scoring models based on m6A regulatory factors, but mainly in oncology, including ovarian cancer, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, and neuroblastoma (Li et al., 2021b; Wang et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). Nomogram prediction models for COVID-19 are based on baseline clinical characteristics. These nomogram models can predict the survival, or overall mortality, of patients (Dong et al., 2021; Moon et al., 2021). However, there are few prediction models based on m6A-related genes. Our study is the first to establish a nomogram model based on m6A regulatory factors to effectively predict the risk of COVID-19. This provides a new approach to clinical practice. This nomogram provides an easy-to-use individualized assessment tool. Using a nomogram, clinicians can calculate an overall score based on the expression of these seven m6A-related genes. The higher the total nomogram score, the greater the COVID-19 risk. The total score corresponds to different levels of risk in the nomogram, which provides clinical value for individualized decision-making.

There are still some limitations in the present study. Firstly, our sample came from two datasets, and so the number of patients was limited. To reduce deviation, multi-center samples and an expansion of the sample size will be required. Secondly, there was a lack of basic clinical characteristics of the patients, which may have affected the accuracy of the nomogram model. In addition, there may also be important variables among these clinical factors. Finally, the specific mechanisms of m6A-related genes in COVID-19 must be verified through further experiments.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the nomogram model based on seven m6A-related genes, including HNRNPA2B1, YTHDC1, ELAVL1, RBM15, RBM15B, WTAP, and HNRNPC, effectively predicted the risk of COVID-19. Among these, YTHDC1 was the most suitable for predicting the risk of infection. The m6A-related genes were significantly related to immune cells. Moreover, m6A-related genes may be associated with the presence or absence of symptoms in COVID-19 patients.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since all the research data are from open online databases, all informed consent can be guaranteed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study is available in the GSE177477 and GSE157103 dataset of Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE177477 and at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE157103, respectively.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the 900th Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force (Grant Number:2020Q02), the 900th Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force Fund (Grant Number: 2020Z12), the 900th Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Forceaa (Grant Number:2021JQ04), the 900th Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Forcea (Grant Number: 2021MS12), and Guiding Project of Social Development of Fujian Province (Grant Number: 2021Y0062).

Authors' contributions

Study concept and design (ALL), acquisition of data (LL, YL, and XA), analysis and interpretation of data (LL, YL, XA, BL, and JH), and drafting of the manuscript (LL, JH, XA, and BL). All authors contributed to study supervision and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

m6A score in patients with COVID-19.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the contributors to GEO for sharing open access to the expression profile data sets and gene-related information.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Barrett T., Wilhite S.E., Ledoux P., Evangelista C., Kim I.F., Tomashevsky M., Marshall K.A., Phillippy K.H., Sherman P.M., Holko M., Yefanov A., Lee H., Zhang N., Robertson C.L., Serova N., Davis S., Soboleva A. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets--update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D991–D995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertero A., Brown S., Madrigal P., Osnato A., Ortmann D., Yiangou L., Kadiwala J., Hubner N.C., de Los Mozos I.R., Sadée C., Lenaerts A.S., Nakanoh S., Grandy R., Farnell E., Ule J., Stunnenberg H.G., Mendjan S., Vallier L. The SMAD2/3 interactome reveals that TGFβ controls m(6)a mRNA methylation in pluripotency. Nature. 2018;555:256–259. doi: 10.1038/nature25784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandary Y.P., Velusamy T., Shetty P., Shetty R.S., Idell S., Cines D.B., Jain D., Bdeir K., Abraham E., Tsuruta Y., Shetty S. Post-transcriptional regulation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor expression in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009;179:288–298. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1787OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun J., Loyal L., Frentsch M., Wendisch D., Georg P., Kurth F., Hippenstiel S., Dingeldey M., Kruse B., Fauchere F., Baysal E., Mangold M., Henze L., Lauster R., Mall M.A., Beyer K., Röhmel J., Voigt S., Schmitz J., Miltenyi S., Demuth I., Müller M.A., Hocke A., Witzenrath M., Suttorp N., Kern F., Reimer U., Wenschuh H., Drosten C., Corman V.M., Giesecke-Thiel C., Sander L.E., Thiel A. SARS-CoV-2-reactive T cells in healthy donors and patients with COVID-19. Nature. 2020;587:270–274. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2598-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess H.M., Depledge D.P., Thompson L., Srinivas K.P., Grande R.C., Vink E.I., Abebe J.S., Blackaby W.P., Hendrick A., Albertella M.R., Kouzarides T., Stapleford K.A., Wilson A.C., Mohr I. Targeting the m(6)a RNA modification pathway blocks SARS-CoV-2 and HCoV-OC43 replication. Genes Dev. 2021;35:1005–1019. doi: 10.1101/gad.348320.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Jin L., Wang Z., Wang L., Chen Q., Cui Y., Liu G. N6-methyladenosine regulates PEDV replication and host gene expression. Virology. 2020;548:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Li H., Zhan H., Liu Y., Li X., Huang Y., Wang L., Zhang F., Li Y. Alterations of m6A RNA methylation regulators contribute to autophagy and immune infiltration in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.949206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimock K., Stoltzfus C.M. Sequence specificity of internal methylation in B77 avian sarcoma virus RNA subunits. Biochemistry. 1977;16:471–478. doi: 10.1021/bi00622a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y.M., Sun J., Li Y.X., Chen Q., Liu Q.Q., Sun Z., Pang R., Chen F., Xu B.Y., Manyande A., Clark T.G., Li J.P., Orhan I.E., Tian Y.K., Wang T., Wu W., Ye D.W. Development and validation of a nomogram for assessing survival in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis.: Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021;72:652–660. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Gomes M., Kruglov A., Durek P., Heinrich F., Tizian C., Heinz G.A., Pascual-Reguant A., Du W., Mothes R., Fan C., Frischbutter S., Habenicht K., Budzinski L., Ninnemann J., Jani P.K., Guerra G.M., Lehmann K., Matz M., Ostendorf L., Heiberger L., Chang H.D., Bauherr S., Maurer M., Schönrich G., Raftery M., Kallinich T., Mall M.A., Angermair S., Treskatsch S., Dörner T., Corman V.M., Diefenbach A., Volk H.D., Elezkurtaj S., Winkler T.H., Dong J., Hauser A.E., Radbruch H., Witkowski M., Melchers F., Radbruch A., Mashreghi M.F. SARS-CoV-2 in severe COVID-19 induces a TGF-β-dominated chronic immune response that does not target itself. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1961. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22210-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye M., Jaffrey S.R., Pan T., Rechavi G., Suzuki T. RNA modifications: what have we learned and where are we headed? Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016;17:365–372. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Dominissini D., Rechavi G., He C. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m6A RNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:293–306. doi: 10.1038/nrg3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung S.Y., Yuen K.S., Ye Z.W., Chan C.P., Jin D.Y. A tug-of-war between severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and host antiviral defence: lessons from other pathogenic viruses. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:558–570. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1736644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazavi A., Ganji A., Keshavarzian N., Rabiemajd S., Mosayebi G. Cytokine profile and disease severity in patients with COVID-19. Cytokine. 2021;137 doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155323. 155323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J., Netea M.G., Rovina N., Akinosoglou K., Antoniadou A., Antonakos N., Damoraki G., Gkavogianni T., Adami M.E., Katsaounou P., Ntaganou M., Kyriakopoulou M., Dimopoulos G., Koutsodimitropoulos I., Velissaris D., Koufargyris P., Karageorgos A., Katrini K., Lekakis V., Lupse M., Kotsaki A., Renieris G., Theodoulou D., Panou V., Koukaki E., Koulouris N., Gogos C., Koutsoukou A. Complex immune dysregulation in COVID-19 patients with severe respiratory failure. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.009. 992–1000.e1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokhale N.S., McIntyre A.B.R., McFadden M.J., Roder A.E., Kennedy E.M., Gandara J.A., Hopcraft S.E., Quicke K.M., Vazquez C., Willer J., Ilkayeva O.R., Law B.A., Holley C.L., Garcia-Blanco M.A., Evans M.J., Suthar M.S., Bradrick S.S., Mason C.E., Horner S.M. N6-Methyladenosine in Flaviviridae viral RNA genomes regulates infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:654–665. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grifoni A., Weiskopf D., Ramirez S.I., Mateus J., Dan J.M., Moderbacher C.R., Rawlings S.A., Sutherland A., Premkumar L., Jadi R.S., Marrama D., de Silva A.M., Frazier A., Carlin A.F., Greenbaum J.A., Peters B., Krammer F., Smith D.M., Crotty S., Sette A. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. 1489–1501.e1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W., Tan F., Huai Q., Wang Z., Shao F., Zhang G., Yang Z., Li R., Xue Q., Gao S., He J. 2021. Comprehensive Analysis of PD-L1 Expression, Immune Infiltrates, and m6A RNA Methylation Regulators in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane S.E., Beemon K. Precise localization of m6A in Rous sarcoma virus RNA reveals clustering of methylation sites: implications for RNA processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1985;5:2298–2306. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.9.2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Khandelwal N., Chander Y., Nagori H., Verma A., Barua A., Godara B., Pal Y., Gulati B.R., Tripathi B.N., Barua S., Kumar N. S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase inhibitor DZNep blocks transcription and translation of SARS-CoV-2 genome with a low tendency to select for drug-resistant viral variants. Antivir. Res. 2022;197 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2021.105232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing A.G., Lorenc A., Del Barrio I. Del Molino, Das A., Fish M., Monin L., Muñoz-Ruiz M., McKenzie D.R., Hayday T.S., Francos-Quijorna I., Kamdar S., Joseph M., Davies D., Davis R., Jennings A., Zlatareva I., Vantourout P., Wu Y., Sofra V., Cano F., Greco M., Theodoridis E., Freedman J.D., Gee S., Chan J.N.E., Ryan S., Bugallo-Blanco E., Peterson P., Kisand K., Haljasmägi L., Chadli L., Moingeon P., Martinez L., Merrick B., Bisnauthsing K., Brooks K., Ibrahim M.A.A., Mason J., Lopez Gomez F., Babalola K., Abdul-Jawad S., Cason J., Mant C., Seow J., Graham C., Doores K.J., Di Rosa F., Edgeworth J., Shankar-Hari M., Hayday A.C. A dynamic COVID-19 immune signature includes associations with poor prognosis. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1623–1635. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.B., Tong J., Zhu S., Batista P.J., Duffy E.E., Zhao J., Bailis W., Cao G., Kroehling L., Chen Y., Wang G., Broughton J.P., Chen Y.G., Kluger Y., Simon M.D., Chang H.Y., Yin Z., Flavell R.A. M(6)a mRNA methylation controls T cell homeostasis by targeting the IL-7/STAT5/SOCS pathways. Nature. 2017;548:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nature23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Pei S., Chen B., Song Y., Zhang T., Yang W., Shaman J. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Science (New York, N.Y.) 2020;368:489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Hui H., Bray B., Gonzalez G.M., Zeller M., Anderson K.G., Knight R., Smith D., Wang Y., Carlin A.F., Rana T.M. METTL3 regulates viral m6A RNA modification and host cell innate immune responses during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Rep. 2021;35 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109091. 109091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Ren C.C., Chen Y.N., Yang L., Zhang F., Wang B.J., Zhu Y.H., Li F.Y., Yang J., Zhang Z.A. A risk score model incorporating three m6A RNA methylation regulators and a related network of miRNAs-m6A regulators-m6A target genes to predict the prognosis of patients with ovarian cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.703969. 703969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichinchi G., Gao S., Saletore Y., Gonzalez G.M., Bansal V., Wang Y., Mason C.E., Rana T.M. Dynamics of the human and viral m(6)A RNA methylomes during HIV-1 infection of T cells. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1:16011. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichinchi G., Zhao B.S., Wu Y., Lu Z., Qin Y., He C., Rana T.M. Dynamics of human and viral RNA methylation during Zika virus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Xu Y.P., Li K., Ye Q., Zhou H.Y., Sun H., Li X., Yu L., Deng Y.Q., Li R.T., Cheng M.L., He B., Zhou J., Li X.F., Wu A., Yi C., Qin C.F. The m(6)A methylome of SARS-CoV-2 in host cells. Cell Res. 2021;31:404–414. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00465-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N., Bi Y., Ma X., Zhan F., Wang L., Hu T., Zhou H., Hu Z., Zhou W., Zhao L., Chen J., Meng Y., Wang J., Lin Y., Yuan J., Xie Z., Ma J., Liu W.J., Wang D., Xu W., Holmes E.C., Gao G.F., Wu G., Chen W., Shi W., Tan W. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet (Lond. Engl.) 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masood K.I., Yameen M., Ashraf J., Shahid S., Mahmood S.F., Nasir A., Nasir N., Jamil B., Ghanchi N.K., Khanum I., Razzak S.A., Kanji A., Hussain R., M E.R, Hasan Z. Upregulated type I interferon responses in asymptomatic COVID-19 infection are associated with improved clinical outcome. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:22958. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y., Zhang Q., Wang K., Zhang X., Yang R., Bi K., Chen W., Diao H. RBM15-mediated N6-methyladenosine modification affects COVID-19 severity by regulating the expression of multitarget genes. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:732. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04012-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K.D., Jaffrey S.R. Rethinking m(6)A readers, writers, and erasers. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017;33:319–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon H.J., Kim K., Kang E.K., Yang H.J., Lee E. Prediction of COVID-19-related mortality and 30-day and 60-day survival probabilities using a nomogram. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021;36 doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e248. e248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniyappa R., Gubbi S. COVID-19 pandemic, coronaviruses, and diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;318 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00124.2020. E736–e741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostareck D.H., Ostareck-Lederer A. RNA-binding proteins in the control of LPS-induced macrophage response. Front. Genet. 2019;10:31. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overmyer K.A., Shishkova E., Miller I.J., Balnis J., Bernstein M.N., Peters-Clarke T.M., Meyer J.G., Quan Q., Muehlbauer L.K., Trujillo E.A., He Y., Chopra A., Chieng H.C., Tiwari A., Judson M.A., Paulson B., Brademan D.R., Zhu Y., Serrano L.R., Linke V., Drake L.A., Adam A.P., Schwartz B.S., Singer H.A., Swanson S., Mosher D.F., Stewart R., Coon J.J., Jaitovich A. Large-scale multi-omic analysis of COVID-19 severity. Cell Syst. 2021;12:23–40.e27. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X., Hua X., Li Q., Zhou Q., Chen J. M(6)a regulator-mediated methylation modification patterns and characteristics of immunity in blood leukocytes of COVID-19 patients. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.774776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan W., Li J., Liu L., Zhang Q., Qin Y., Pei X., Chen J. Influence of N6-Methyladenosine modification gene HNRNPC on cell phenotype in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Dis. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/9919129. 9919129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree I.A., Evans M.E., Pan T., He C. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell. 2017;169:1187–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine T., Perez-Potti A., Rivera-Ballesteros O., Strålin K., Gorin J.B., Olsson A., Llewellyn-Lacey S., Kamal H., Bogdanovic G., Muschiol S., Wullimann D.J., Kammann T., Emgård J., Parrot T., Folkesson E., Rooyackers O., Eriksson L.I., Henter J.I., Sönnerborg A., Allander T., Albert J., Nielsen M., Klingström J., Gredmark-Russ S., Björkström N.K., Sandberg J.K., Price D.A., Ljunggren H.G., Aleman S., Buggert M. Robust T cell immunity in convalescent individuals with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.017. 158–168.e114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Liu J., Zhang D., Xu Z., Ji J., Wen C. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: the current evidence and treatment strategies. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1708. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevarajan I., Nguyen T.H.O., Koutsakos M., Druce J., Caly L., van de Sandt C.E., Jia X., Nicholson S., Catton M., Cowie B., Tong S.Y.C., Lewin S.R., Kedzierska K. Breadth of concomitant immune responses prior to patient recovery: a case report of non-severe COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26:453–455. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Cheng H., Xu H., Yu X., Sui D. A five-gene signature derived from m6A regulators to improve prognosis prediction of neuroblastoma. Cancer Biomark.: Sect. A Dis. Markers. 2020;28:275–284. doi: 10.3233/CBM-191196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Xu Z., Wang Z., Ren Z., Li L., Ruan Y. Dendritic cells with METTL3 gene knockdown exhibit immature properties and prolong allograft survival. Genes Immun. 2020;21:193–202. doi: 10.1038/s41435-020-0099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Hsu P.J., Chen Y.S., Yang Y.G. Dynamic transcriptomic m(6)A decoration: writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Res. 2018;28:616–624. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0040-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Wu Q., Li B., Wang D., Wang L., Zhou Y.L. M(6)A regulator-mediated methylation modification patterns and tumor microenvironment infiltration characterization in gastric cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2020;19:53. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01170-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Tao Z., Chen X. Identification of a three-m6A related gene risk score model as a potential prognostic biomarker in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. PeerJ. 2020;8 doi: 10.7717/peerj.8827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

m6A score in patients with COVID-19.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study is available in the GSE177477 and GSE157103 dataset of Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE177477 and at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE157103, respectively.

Data will be made available on request.