Abstract

Purpose of Review

This study aims to review state-of-the-art advances in Siglec-9-directed antibodies and to highlight specific aspects of Siglec-9 antibodies that are suitable to mount anti-tumor immunity.

Recent Findings

Controversies surrounding studies on Siglec-9 antibodies can confound future studies. In this review, we have highlighted some controversies, explained the distinction between Siglec-9 agonistic and antagonistic (endocytic) antibodies, and discussed their suitability in sustaining anti-tumor immunity.

Summary

Siglec-9 is an immune checkpoint target and an immunoinhibitory receptor that can engage either sialic acid ligands or agonistic antibodies. Through Siglec-9 sialic acid interactions, activated immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory signaling of the immune cells can lead to unfavorable immunosuppression. To overcome tumor-related immunosuppression, different types of Siglec-9 antibody blockade need to be developed. However, whether a Siglec-9-directed antibody is agonistic or antagonistic is probably affinity-dependent and not epitope-dependent. Additionally, unlike immune-modulatory antibodies such as agonistic antibodies (OX40, CD28, ICOS, and 4-1BB) or Fc-inert antibodies (PD1 and PD-L1) directed against cancer cells, the nature of antagonistic Siglec-9 antibodies is more suitable to enhance anti-tumor immunity and will be discussed.

Keywords: Siglec-9 antibody, Antagonism, Agonism, Affinity, Sialic acid

Introduction

First discovered in 2000, Siglec-9 (CD329) is a member of the CD33-related sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins with 84% sequence homology to Siglec-7 [1, 2]. Like most other immunoinhibitory Siglec family members, its cytoplasmic tail contains immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory (ITIM) and ITIM-like motifs. The classical mechanism of inhibitory Siglec-9 signaling upon binding to their sialic acid ligand, would result in phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the ITIM domain by SRC kinase and the recruitment of inhibitory tyrosine phosphatase Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase (SHP) SHP1 and/or SHP2 [3]. These lead to a range of cell-type-specific inhibitory functional signalings, such as suppressing neutrophil activation, CD8+ T cell, and NK cell effector functions [4, 5, 6••]. Furthermore, its basal expression is found in healthy human immune cell types such as monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and CD16Bright/CD56−/dim NK cells [2, 4, 7••]. of note, Siglec-9 is also weakly expressed on CD16dim/−/CD56Bright NK, B cells, tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells, and PD-1+/CD8+ T cells in humans but not found in NK cells and T cells in mice (Siglec-E, an ortholog of human Siglec-9) [4, 8–11].

Siglec-9 is an emerging immune checkpoint therapeutic target, and blockade appears to boost anti-cancer immunity [12]. However, the success of this targeted approach depends not only on the specific monoclonal antibodies but also on their ability to induce a proper immune function. Here, we will highlight the consistencies and attempt to resolve opposing studies that have yielded conflicting results. This review covers how different sialic acid and non-sialic acid blocking Siglec-9 antibodies can be agonistic or antagonistic (endocytic), leading to varying levels of intended anti-tumor immunity (Table 1), and provide a rationale when designing Siglec-9 antibodies.

Table 1.

An overview of Siglec-9-directed antibodies and their functions

| Effector function | Anti-Siglec-9 clone | Observation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocking, agonist | 191240 | Downregulated NF-κB activity in HEKBlue hTLR4 cells | [30] |

| Inhibited MUC1 binding to Siglec-9 myeloid cells and reduces TAM polarization | [13, 14•] | ||

| Inhibited T cell activation in a dose-dependent manner like clone E10-286 | [9] | ||

| Competed with LGALS3BP, a Siglec-9 ligand involved in inhibiting neutrophil activation | [16] | ||

| Failed to block Siglec-7 positive NK cells, resulting in cytotoxicity. Reduced cytotoxicity for Siglec-9 positive NK cells | [55] | ||

| Activated Siglec-9 positive neutrophils resulting in tumor cell killing | [11] | ||

| Inhibited MUC16 positive ovarian cancer cells binding to monocytes | [10] | ||

| Blocking (undefined) | Did not inhibit NK cell cytotoxicity against chronic myelogenous leukemia, K562 cells unlike clone E10-286. This finding may be refuted if the studied Siglec-9’s V-set was masked by sialic acids | [4] | |

| Reduced differentiation of monocytes to CD163+ macrophages in co-culture with tumor cell lines BxPC3 and PaTuS. Greater reduction was observed when used with anti-Siglec-7 | [15•] | ||

| Blocking, partial agonist | Loss of agonism with a monomeric 191240 Fab fragment | [9] | |

| Non-blocking, agonist | E10-286 | Inhibited Siglec-9 positive CD8+ T cells and IFNγ production. Triggers phosphorylation of Siglec-9 and SHP-1 | [6••] |

| Reduced CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity against mastocytoma P815 cells | [6••] | ||

| Inhibited T cell activation in a dose-dependent manner like clone 191240 | [9] | ||

| Did not compete with LGALS3BP, a Siglec-9 ligand involved in inhibiting neutrophil activation | [16] | ||

| Reduced activation of Siglec-9-positive neutrophils when compared to the clone 191240. This finding did not elaborate on binary sialic acid and clone E10-286 binding | [11] | ||

| Inhibited NK cell cytotoxicity against chronic myelogenous leukemia, K562 cells | [4] | ||

| Non-blocking, antagonist | 2D4 | Reduced Siglec-9 surface expression and exhibited anti-tumor responses when used in combination with pembrolizumab | [7••] |

| Blocking (undefined) | 68D4 and 224B1 | Activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Increased cytotoxicity of NK92 cell line against chronic myelogenous leukemia, K562 cells | [43••] |

| Blocking (undefined) | 8A1E9 | Increased NK cell cytotoxicity against chronic myelogenous leukemia, K562 cells | [20, 21••] |

| Blocking (undefined) | mAbA | Enhanced anti-tumor immunity in Siglec-7/-9 expressing mice, used in combination with an anti-Siglec-7 sialic acid blocking antibody | [12] |

| Blocking (undefined) | mAbA | Increased NK cell cytotoxicity against colorectal adenocarcinoma, HT29 cells | [18••] |

| Blocking (undefined) | KALLI | Siglec-9 mediated endocytosis of antibodies | [37, 56] |

| Agonist (undefined) | 1–3-A | Suppressed induction of LPS-mediated COX2 mRNA production in histiocytic lymphoma, U937 cells | [17] |

More than Just Sialic Acid-Binding Epitopes on Siglec-9 Receptor

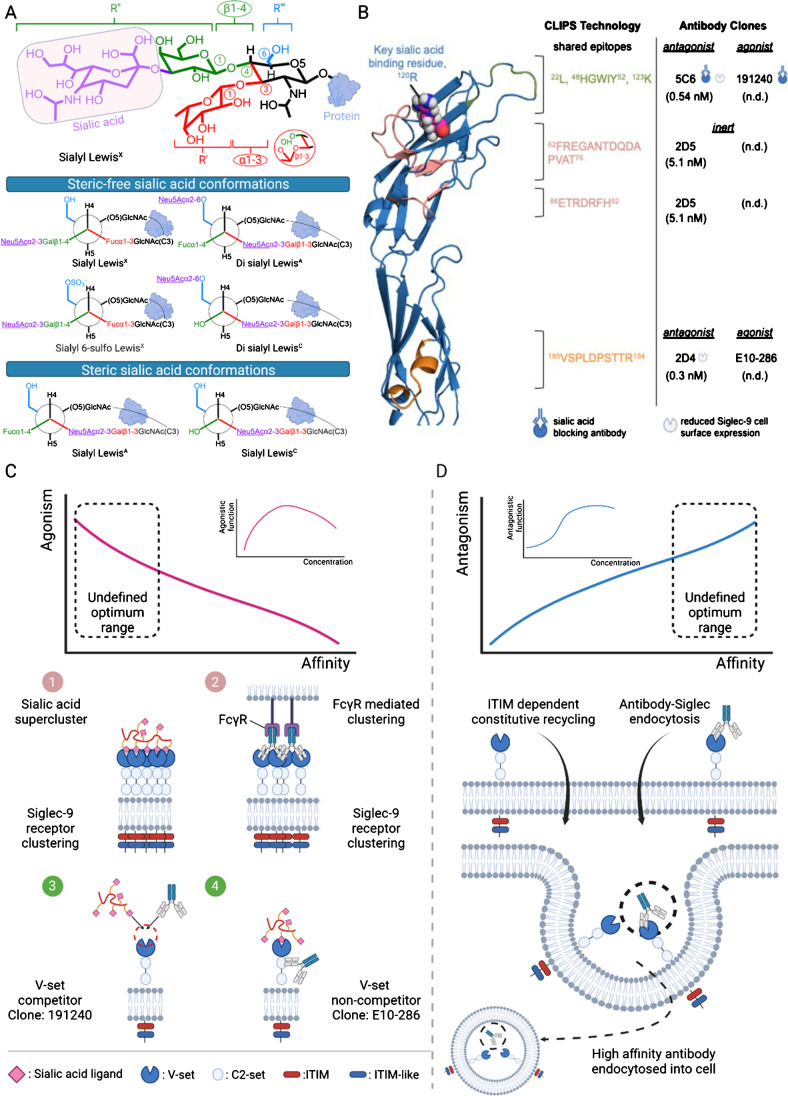

Studies on designing blocking antibodies that compete with the sialic acid-binding site may require an awareness of other possible cryptic binding sites. Hyper-sialylated cancer cells gain survival advantages from their ability to bind to Siglecs expressed on immune cells and manipulate the tumor microenvironment (TME) by inducing the formation of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) to promote their growth and metastasis while evading NK cell and T cell-mediated cytotoxicity [13, 14•, 15•]. Examples of glycoproteins in cancer that display an aberrantly sialylated glycan landscape capable of binding to Siglec-9 include mucin 1 (MUC1) and lectin galactoside-binding soluble 3 binding protein (LGALS3BP) [13, 16]. Earlier reports on Siglec-9 sialic acid ligands have shown that Siglec-9 displays preferential binding to a predominant sialic acid, Neu5Acα2-3, found on both sialyl 6-sulfo Lewisx and the cancer-associated sialyl Lewis x (sLewisx) [1, 17, 18••]. This is unlike its close homolog, Siglec-7, which preferably binds to Neu5Acα2-8Neu5Acα2-3 on gangliosides. This sialic acid ligand preference is attributed to key arginines in their binding grooves; Siglec-9 has one at R120, while Siglec-7 has two, R67 and R124 [1, 2, 19]. Furthermore, tryptophans W132 and W128 in Siglec-7 and Siglec-9, respectively, may engage alternate hydrophobic interaction with the glycerol moiety on the sialic acid [1, 18••]. Moreover, sialic acid in the 3rd position on the GlcNAc sugar is often poorly recognized by Siglec-9 receptor, as reported in a comprehensive binding study by Miyazaki et al. (2012) using glycan expressing colonic epithelial cells. In this study, Siglec-9 preferably binds sialic acids α2-3 linked Galβ1-4GlcNAc (sialyl LewisX) to sialic acids α2-3 linked Galβ1-3GlcNAc (sialyl LewisA/C, where LewisA carries an additional fucose sugar) [17]. A Newman projection shows that only the β1-4 linkage presents the sialic acid-bearing group in the 4th position on the GlcNAc or GalNAc sugar at a favorable steric-free position for Siglec-9 recognition (indicated as R’’) (Fig. 1A). Additionally, Siglec-9 prefers disialyl LewisA/C to sialyl LewisA/C ligand, which is again explained using the Newman projection, which exposes one sialic acid in the R’’’ group position. These suggest that terminal sialic acid ligands have to be exposed for Siglec-9 or Siglec family interaction. Indeed, two independent studies by Angata et al. (2000) and Beatson et al. (2016) also showed that Siglec-9 binds very weakly to sialic acid α2-3 linked Galβ1-3GalNAc (ST) [1, 13], with no observable Siglec-9 binding to both ST-coated glycan array and ST-coated polymers in vitro. Taken together, the 3rd position on the GlcNAc or GalNac sugar puts the sialic acid-bearing group in an unfavorable steric position (R’ group position) for Siglec-9 receptor recognition.

Fig. 1.

Siglec-9 and its partner sialic acids or directed antibodies. A Newman projection-based explanation for different sialic acid ligand binding preferences. Only the sialic acid (Neu5Ac, a predominant form)-bearing groups located at the 4th and 6th positions on GlcNAc/GalNAc (on R’’ and R’’’, respectively) remain exposed for Siglec-9 receptor recognition. In the steric conformations, the sialic acid in the 3rd position on GlcNAc/GalNAc (on R’) is in close proximity to the bulky O-linked protein. GalNAc in MUC1-ST is not shown. B The unsolved Siglec-9 receptor was modeled using AlphaFold, and the previously determined conformational epitopes were mapped onto it [7••, 53]. Full antagonistic antibodies that deplete surface Siglec-9 receptor density such as 5C6 and 2D4 have a binding affinity in low nM. Here, an inert antibody, clone 2D5, binds weakly and neither blocks sialic acid binding nor depletes surface Siglec-9 receptor density. It is still unknown about the binding affinity range for agonistic antibodies such as clones 191240 and E10-286. A structural interpretation shows that sialic acid-binding epitope plays no role in dictating the antagonism of an antibody. n.d. denotes not determined. C (Top) A mechanistic overview of Siglec-9 receptor oligomerization driven by (1) sialic acid supercluster or (2) FcγR-mediated agonistic antibody clusters. (Bottom) Diagram illustrating the competitive and non-competitive nature of agonistic antibodies (3) clone 191240 and (4) clone E10-286. The dose–response relationship of agonistic antibodies is bell-shaped [38, 54]. The optimum affinity range associated with agonism remains unknown. D A mechanistic overview of Siglec-9 endocytosis when strongly bound to antagonistic antibodies. This phenomenon may be harnessed by antibody conjugates to deliver cytotoxic drugs into the cancer cells. The dose–response relationship of antagonistic antibodies is sigmoidal [38]. The optimum affinity range associated with antagonism remains unknown. Figures 1C and D were made in BioRender

Besides sialic acid binding, Beatson et al. continued to show that Siglec-9 expressing myeloid cells can bind strongly to MUC1-ST, suggesting boosted interaction involving Siglec-9, sialic acid, and MUC1 protein. This binding was abolished in asialoMUC1 (MUC1-T) [13]; this underscored a cryptic protein–protein interaction between the MUC1 protein backbone and Siglec-9 receptors, as alternative epitopes for Siglec-9 antibodies.

Mapping Conformational Epitopes of Siglec-9 Antibodies

Identifying a monoclonal antibody’s epitope is integral for characterizing binding or blocking specificities. However, the choice of linear peptides for epitope mapping may misinform conformational epitopes. For example, Choi et al. have employed Siglec-9-derived linear peptides to report clone 191240 binding to the membrane-proximal C2-set and later showed their most potent clone 8A1E9 binding at the N-terminal region [20, 21••]. Instead, using CLIPS cyclization, Rosenthal et al. showed that the conformational epitopes for clone 191240 are at the N-terminal region. Unlike Choi et al.’s study, Rosenthal et al.’s report is more consistent with the sialic acid blocking nature of clone 191240 at the N-terminal ligand binding site on Siglec-9 receptor [7••]. Alternatively, soluble Siglec-9 protein can be produced with several point mutations to get a more accurate description of antibody recognition. Nonetheless, Choi et al. have reported a potent Siglec-9 antibody that targets the N-terminal region with enhanced anti-tumor activity in vitro.

Agonistic Siglec-9-Directed Antibodies for Anti-inflammatory Therapies

Agonistic Siglec-9 antibodies mimic natural sialic acid ligands, which induce SHP-1 phosphorylation and trigger inhibitory cell signaling. Siglec-9 cross-linking due to sialic acid clusters can deplete neutrophils, a normal mechanism in Siglecs on leukocytes to downregulate inflammation [22, 23]. Notably, FcγR expressed on antigen-presenting cells can crosslink agonist antibodies bound to receptors and result in receptor cross-linking or oligomerization. Receptor oligomerization is a prerequisite for activating downstream signaling in tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, but Siglec receptor oligomerization still remains poorly understood [24]; CD22 is reported to be a multimer; Siglec-5, Siglec-8, and Siglec-11 are thought to be disulfide-linked dimers [25–28]. Siglec-7 and Siglec-9 exist as monomers [29, 30]. Nonetheless, soluble sialoside analog pS9-sol is unable to induce Siglec-9 receptor oligomerization. On the other hand, membrane-tethered pS9-L provided evidence of induced Siglec-9 receptor clustering [30]. This indirectly suggests that Siglec-9 antibody (FcγR mediated) multimerization may trigger Siglec-9 receptor clustering [31].

Here, two popular human Siglec-9 antibody clones, sialic acid blocking clone 191240 and non-sialic acid blocking clone E10-286 (using Siaα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAc on glycan array), have been described as agonistic antibodies [32]. In this review, we have mapped their binding epitopes onto the Siglec-9 receptor based on a competitive antibody study (Fig. 1B) [7••]. The clone E10-286 was found to be more agonistic than clone 191240, resulting in a stronger inhibition of Siglec-9 expressing NK cell cytotoxicity [4]. This concurs with the possibility that the Siglec-9 receptor can engage both sialic acid and clone E10-286 as binary ligands (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, clone 191240 would compete for the same sialic acid-binding cleft, thus likely resulting in a weaker agonistic effect.

Agonism is not limited to intact antibodies because antibody fragment (hS9-Fab03) has also been shown to be specific to Siglec-9 and exhibit immunoinhibitory effects in PBMC- or THP-1-differentiated macrophages [33]. However, in their study, hS9-Fab03 generated in E. coli BL21 cells as agonists of toll-like receptors may carry endotoxins [34].The authors did not perform endotoxin removal on the hS9-Fab03 in their LPS-stimulated studies. Thus, it remains debatable about the true avidity of the antibody fragment. Next, Siglec-9 can be an autoantigen, whereby agonistic anti-Siglec-9 autoantibodies are found in IVIg preparations for treating autoimmune diseases, which explain the observed neutropenia among patients [35, 36]. In comparison, synthetic Siglec-9 agonists or glycopolymers have been used to curb neutrophil hyperinflammation in COVID-19 by favoring apoptosis and not NETosis [23].

There is another debatable finding associated with macrophages. Laubli et al. have used LS180 tumor co-cultures and observed a marginal increase in the number of tumor-associated CD11b+CD206+ M2 macrophages using agonistic Siglec-9 antibody clone 191,240 [11]. On the other hand, Beatson et al. first observed a significant increase in the number of PD-L1+CD206+ M2 macrophages in the presence of MUC1-ST. Second, Beatson et al. further showed that MUC1-ST-induced TAM-like macrophage formation can be blocked using the same clone 191240, which contradicts Laubli et al. [13]. More studies are needed to validate both opposing studies on the propensity of M2 macrophage polarization. In this unique situation, Siglec-9 agonism via SHP-1 is deemed as the therapeutic way to treat both cancer and infectious diseases via reducing the TAM-like macrophage population [23].

Designing Antagonistic (Endocytic) Siglec-9-Directed Antibodies for Cancer Therapies

Many studies have observed reduced tumor growth in Siglec-9 knockout experiments in vivo and in vitro, which are the Rosetta stones to develop Siglec-9 antibodies to treat cancer today. In oncology, epithelial tumor cells overexpress heavily glycosylated mucins that bind to Siglec-9 [10, 13]. Additionally, Siglec-9 is overexpressed on primary acute myeloid leukemia cells but absent in progenitor cells in patient bone marrow samples [37]. These suggest that blocking Siglec-9 sialic acid interactions can become potential therapeutic strategies. Interestingly, a naturally occurring Siglec-9 K131Q (A391C) polymorphism (rs16988910) with diminished sialic acid binding was associated with improved early overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients in only the first 2 years but not in subsequent years [11]. This finding motivated others to develop antagonistic Siglec-9 antibodies that can either reduce Siglec-9 expression on the cell surface and/or inhibit Siglec-9 ligand interactions and reduce tumor growth and volume [12]. This is unlike the development of agonistic antibodies (OX40, CD28, ICOS, 4-1BB) in clinical development against cancer, which has been nicely reviewed elsewhere [38].

Today, there is still no known clinical trial using antagonistic Siglec-9 antibodies to treat cancer. The idea of antagonistic Siglec-9 antibodies that serves to potentiate immune reactivity towards cancer is not new. The mechanistic nature of antagonistic antibodies in depleting surface Siglec-9 receptors is via endocytosis in a tyrosine-ITIM dependent manner [37]. However, an empirical approach is still needed to characterize the antibody using cell-based or in vivo models [39–41]. Unlike “stepping on the gas” OX40-targeted agonistic antibodies which can activate OX40 on activated T cells to potentiate T cell receptor (TCR) signaling and depletes the number of FoxP3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), Siglec agonism suppresses immune reactivity, which is more appropriate for anti-inflammatory therapies [23, 42]. Ideally, the design of Siglec-9 antibodies as cancer therapeutics should not activate downstream ITIM inhibitory signaling pathways, a brake in immune responses.

The design of agonistic or antagonistic antibodies is not epitope-specific. For example, both clones E10-286 (an agonist) and 2D4 (an antagonist) can target the same epitopes found away from the sialic acid-binding region on the Siglec-9 receptor. As an antagonist, clone 2D4 has earlier been shown to downregulate surface Siglec-9 expression on monocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages by up to 80% for 21 days [7••]. The depletion of Siglec-9 surface expression would favorably overcome immunosuppression due to limited immunoinhibitory Siglec-sialic acid interactions. Indeed, in another study, Choi et al. have reported a sialic acid blocking Siglec-9 antibody that reduced the tumor burden of humanized immunodeficient NOD scid gamma mice inoculated with SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells. They also found that sialic acid blocking Siglec-9 antibodies in combination with a MUC1 vaccine increased CD4+ and CD8+ MUC1-specific, IFN-γ-expressing T cells and NK cell CD56 expression and cell count when compared to mice that were untreated or only vaccinated [20, 21••]. Of note, in a separate study, reduced melanoma tumor volume was observed in humanized mice when clone 2D4 was used in combinatorial treatment with Keytruda®, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor compared to 2D4 untreated mice [7••].

Although the features of antagonistic antibodies are not well-defined, the general rule is one with the highest binding strength. In some cases, the native sialic acid ligand binds weakly and may be out-competed by the higher affinity antibody. In other cases, the antagonistic antibody does not compete with sialic acid ligand. For instance, both antagonistic antibody clones 5C6 (sialic acid blocking) and 2D4 (non-sialic acid blocking) bind with low nanomolar affinity, which falls in the range of high-affinity antibodies (10−9 M) but not very high-affinity antibodies (10−12 M) [7••]. In comparison, an inert antibody, a weaker affinity binding clone 2D5, can bind to macrophages (93.2%) but not strongly to monocytes (9.1%) and dendritic cells (34.2%), when compared to clone 2D4 (macrophages, 99.1%; monocytes, 95%; dendritic cells, 99.3%) [7••]. Notably, the clone 2D5 also does not cause reduced surface Siglec-9 receptor expression like clones 5C6 and 2D4 (Fig. 1B). In a separate study, weaker affinity clone 5C6 and negative control 53C3 did not induce any stimulatory effects on effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as suggested by the absence of CD69 and CD25 [43••]. For this reason, more studies are needed to evaluate the optimum binding affinities of Siglec-9-directed antibodies to be full antagonist and neither inert nor agonistic.

Finally, increasing evidence also highlights that FcγR clustering via the Fc region can enhance agonistic antibody-mediated receptor clustering, ADCC, and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) [44]. However, for antagonistic antibodies, the endocytic event leading to Siglec-9 downregulation is independent of FcγRs. Therefore, silencing or removal of the Fc regions to minimize interactions with FcγRs might be a key consideration in the design of future antagonistic antibodies. For example, Fc-inert antibodies against PD-1 and PD-L1 have shown clinical efficacy against melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, NSCLC, and urothelial carcinoma as FDA-approved therapeutics [45–48]. We have included well-defined Fc mutations to guide the design of such Fc-inert Siglec-9-directed antibodies in Table 2.

Table 2.

Known FcR mutations to either enhance or abolish FcR binding. Siglec-9 downregulation is independent of FcγRs. Therefore, silencing or removal of the Fc region to minimize interactions with FcγRs is a key consideration in the design of antagonistic antibodies and vice versa. Of note, FcγRs-independent receptor cross-linking/agonism has also been reported due to hexameric antibody formation in solution due to mutations made on the Fc region [44, 59]. #The authors misannotated L235A as F235A

| Effector function | Mutations | Fc isotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silence binding to Fcγ receptors | E233P, L234V, L235A, G236 del., P238A, D265A, N297A, A327Q/G, and P329A | IgG1 | [7••] |

| V234A, G237A, P238S, H268A, V309L, A330S, and P331S | IgG2 | ||

| E233P, F234V, L235A#, G237A, N297A/Q, and E318A | IgG4 | ||

| Silence binding to Fcγ receptors | L234A, L235A, G237A, P238S, H268A, A330S, and P331S | IgG1 | [57] |

| Enhance binding to FcγRIIB and FcγRIIA (Arg 131 allotype) | S267E and L328F | IgG1 | [44] |

| Enhance binding to FcγRIIB | E233D, G237D, P238D, H268D, P271G, and A330R | IgG1 | [58] |

| Formation of hexamers in solution | E345R, E430G, and S440Y | IgG1 | [59] |

Other Forms of Siglec-9 Antibodies as Anti-Cancer Agents

As of writing, no Siglec-9 antibody conjugate is in clinical trials for treating cancer. In the case of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), surface Siglec-9 is expressed to a similar magnitude as CD33 in 7 out of 21 AML cases [37]. Antagonistic antibodies can undergo endocytosis; thus, antibody–drug conjugate design can take advantage of the constitutive recycling of Siglec-9 as seen in certain malignancies such as AML (Fig. 1D). Similar strategies to deplete Siglec-expressing tumors have also been employed, for example, gemtuzumab ozogamicin is a calicheamicin-conjugated humanized anti-CD33 mAb (IgG4) used for delivering cytotoxic payloads into Siglec-3 expressing target AML cells and is administered at a lower dosage of 3 mg/m2 to reduce the chance of human fatalities [49]. In another approach, an inert antibody fused to sialidase, anti-HER2 sialidase, cleaves off sialic acids recognized by Siglec-7/-9 and has resulted in NK-mediated killing of HER2-positive breast tumor cells [50]. However, many factors such as affinity, epitope specificity, and receptor occupancy still remain unclear for inert Siglec-9-directed antibodies, which bind but do not activate ITIM inhibitory signaling.

Conclusion

Siglec-9 is emerging as an immune checkpoint target for cancer immunotherapy [51•]. In this review, we have highlighted some controversies and certain differentiating features of a binding sialic acid ligand and an antagonistic Siglec-9 antibody to mount anti-tumor immunity. These features include exposed sialic acid in glycan-bearing groups and reduce surface Siglec-9 receptor density and endocytic and higher affinity. It is also clear that agonistic Siglec-9 antibodies are more appropriate for anti-inflammatory therapies such as depletion of neutrophils associated with severe COVID-19 [52]. On the other hand, little is known about the binding affinity range distinguishing agonistic, inert, and antagonistic Siglec-9-directed antibodies. Nonetheless, high (nM) affinity antibodies have been associated with antagonism, and in this case, antagonistic Siglec-9 antibodies can piggyback on the endocytosing Siglec-9 receptors to either reduce surface Siglec-9 receptor density or deliver cytotoxic drugs into the cancer cells, in an epitope non-specific manner.

The challenges of identifying antagonistic Siglec-9 antibodies still remain largely empirical. There is no biophysical guideline that can reliably predict antagonism. In this review, we have observed high-affinity antibodies (KD ~ low 10–9 M) as likely antagonistic for Siglec-9 antibodies that may reduce surface Siglec-9 receptor expression and inhibit a “brake” in immunosuppression in cancer. But more studies are still needed to correlate higher binding affinities and Siglec-9 antibody antagonism. Also, whether higher affinity sialic acid ligands can synergize with antagonism either alone or as a binary antibody-sialic acid conjugate instead of sialidase conjugate. Presently, only full functional characterization can confirm that the antibody functions as an antagonist—a cancer cell killing approach. In this regard, we have included known characteristics of an antibody that may help guide the design of a new generation of Siglec-9-directed antibodies.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during the current review are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jun Hui Shawn Wang, Nan Jiang, and Amit Jain declare no conflict of interest. Jackwee Lim has received funding from the A*STAR Career Development Fund 2022 to study the Siglec family members.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical collection on Evolving Therapies

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Angata T, Varki A. Cloning, characterization, and phylogenetic analysis of Siglec-9, a new member of the CD33-related group of Siglecs: evidence for co-evolution with sialic acid synthesis pathways. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22127–22135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002775200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang JQ, Nicoll G, Jones C, Crocker PR. Siglec-9, a novel sialic acid binding member of the immunoglobulin superfamily expressed broadly on human blood leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22121–22126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avril T, Floyd H, Lopez F, Vivier E, Crocker PR. The membrane-proximal immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif is critical for the inhibitory signaling mediated by Siglecs-7 and -9, CD33-related Siglecs expressed on human monocytes and NK cells. J Immunol Am Assoc Immunol. 2004;173:6841–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jandus C, Boligan KF, Chijioke O, Liu H, Dahlhaus M, Démoulins T, et al. Interactions between Siglec-7/9 receptors and ligands influence NK cell-dependent tumor immunosurveillance. J Clin Inv. Am Soc Clin Inv. 2014;124:1810–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI65899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lizcano A, Secundino I, Dohrmann S, Corriden R, Rohena C, Diaz S, et al. Erythrocyte sialoglycoproteins engage Siglec-9 on neutrophils to suppress activation. Blood Am Soc Hematol. 2017;129:3100–3110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-751636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.•• Haas Q, Boligan KF, Jandus C, Schneider C, Simillion C, Stanczak MA, et al. Siglec-9 regulates an effector memory CD8+ T-cell subset that congregates in the melanoma tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Res. American Association for Cancer Research Inc. 2019;7:707–18. This study highlights a combinatorial approach using both anti-Siglec-9 and anti-PD-1 to enhance CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.•• Rosenthal Arnon, Monroe Kate, Lee Seung-Joo. Anti-siglec-9 antibodies and methods of use thereof. Patent US20210095023A1. 2021. This study describes the use of CLIPS technology to map conformational epitopes recognized by anti-Siglec-9 clones 2D4, 2D5, 191240, E10–286, and 5C6.

- 8.Gonzalez-Gil A, Schnaar RL. Siglec ligands. Cells. 2021;10:1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Stanczak MA, Siddiqui SS, Trefny MP, Thommen DS, Boligan KF, von Gunten S, et al. Self-associated molecular patterns mediate cancer immune evasion by engaging Siglecs on T cells. J Clin Inv Am Soc Clin Inv. 2018;128:4912–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI120612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belisle JA, Horibata S, Jennifer GA, et al. Identification of Siglec-9 as the receptor for MUC16 on human NK cells, B cells, and monocytes. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Läubli H, Pearce OMT, Schwarz F, Siddiqui SS, Deng L, Stanczak MA, et al. Engagement of myelomonocytic Siglecs by tumor-associated ligands modulates the innate immune response to cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:14211–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ibarlucea-Benitez I, Weitzenfeld P, Smith P, Ravetch J v. Siglecs-7/9 function as inhibitory immune checkpoints in vivo and can be targeted to enhance therapeutic antitumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet]. 2021;118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Beatson R, Tajadura-Ortega V, Achkova D, Picco G, Tsourouktsoglou TD, Klausing S, et al. The mucin MUC1 modulates the tumor immunological microenvironment through engagement of the lectin Siglec-9. Nat Immunol Nature Publishing Group. 2016;17:1273–1281. doi: 10.1038/ni.3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.• Beatson R, Graham R, Grundland Freile F, et al. Cancer-associated hypersialylated MUC1 drives the differentiation of human monocytes into macrophages with a pathogenic phenotype. Commun Biol. 2020;3(1):644. This study describes Siglec-9 signaling pathways that drive the formation of TAMs in breast cancer patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.• Rodriguez E, Boelaars K, Brown K, et al. Sialic acids in pancreatic cancer cells drive tumour associated macrophage differentiation via the Siglec receptors Siglec-7 and Siglec-9. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1270. This study describes Siglec-9 signaling pathways that drive the formation of TAMs in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Läubli H, Alisson-Silva F, Stanczak MA, Siddiqui SS, Deng L, Verhagen A, et al. Lectin galactoside-binding soluble 3 binding protein (LGALS3BP) is a tumor-associated immunomodulatory ligand for CD33-related siglecs. J Biol Chem Am Soc Biochem Mol Biol Inc. 2014;289:33481–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Miyazaki K, Sakuma K, Kawamura YI, Izawa M, Ohmori K, Mitsuki M, et al. Colonic epithelial cells express specific ligands for mucosal macrophage immunosuppressive receptors Siglec-7 and -9. J Immunol Am Assoc Immunolog. 2012;188:4690–700. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.•• Cornen Stéphanie, Rossi Benjamin, Wagtmann Nicolai, Gauthier Laurent. Siglec-9-neutralizing antibodies. Patent US20200369765A1. 2020. This study describes the Siglec-9 blocking antibodies in reducing tumor size in colorectal adenocarcinoma, HT29 cells.

- 19.Yamakawa N, Yasuda Y, Yoshimura A, et al. Discovery of a new sialic acid binding region that regulates Siglec-7. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Choi H, Ho M, Adeniji OS, Giron L, Bordoloi D, Kulkarni AJ, Puchalt AP, Abdel-Mohsen M, Muthumani K. Development of Siglec-9 blocking antibody to enhance anti-tumor immunity. Front Oncol. 2021;11:778989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.•• Kar Muthumani, Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen, David Weiner, Shyam Somasundaram. Monoclonal antibodies against Siglec-9 and use thereof for immunotherapy. Patent WO2021247821. 2021. This study describes the Siglec-9 blocking antibodies in promoting NK cell cytotoxicity against chronic myelogenous leukemia, K562 cells.

- 22.Yu H, Gonzalez-Gil A, Wei Y, Fernandes SM, Porell RN, Vajn K, et al. Siglec-8 and Siglec-9 binding specificities and endogenous airway ligand distributions and properties. Glycobiology Oxford Univ Press. 2017;27:657–668. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwx026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delaveris CS, Wilk AJ, Riley NM, Stark JC, Yang SS, Rogers AJ, et al. Synthetic Siglec-9 agonists inhibit neutrophil activation associated with COVID-19. ACS Cent Sci Am Chem Soc. 2021;7:650–657. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kucka K, Wajant H. Receptor oligomerization and its relevance for signaling by receptors of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;8:615141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Han S, Collins BE, Bengtson P, Paulson JC. Homomultimeric complexes of CD22 in B cells revealed by protein-glycan cross-linking. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:93–97. doi: 10.1038/nchembio713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cornish AL, Freeman S, Forbes G, et al. Characterization of siglec-5, a novel glycoprotein expressed on myeloid cells related to CD33. Blood. 1998;92(6):2123–2132. doi: 10.1182/blood.V92.6.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Floyd H, Ni J, Cornish AL, Zeng Z, Liu D, Carter KC, et al. Siglec-8 A novel eosinophil-specific member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:861–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angata T, Kerr SC, Greaves DR, Varki NM, Crocker PR, Varki A. Cloning and characterization of human Siglec-11: a recently evolved signaling molecule that can interact with SHP-1 and SHP-2 and is expressed by tissue macrophages, including brain microglia. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24466–24474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicoll G, Ni J, Liu D, Klenerman P, Munday J, Dubock S, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel siglec, siglec-7, expressed by human natural killer cells and monocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34089–34095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delaveris CS, Chiu SH, Riley NM, Bertozzi CR. Modulation of immune cell reactivity with CIS binding Siglec agonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2012408118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wilson NS, Yang B, Yang A, Loeser S, Marsters S, Lawrence D, et al. An Fcγ receptor-dependent mechanism drives antibody-mediated target-receptor signaling in cancer cells. Cancer Cell Cell Press. 2011;19:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlin AF, Uchiyama S, Chang YC, Lewis AL, Nizet V, Varki A. Molecular mimicry of host sialylated glycans allows a bacterial pathogen to engage neutrophil Siglec-9 and dampen the innate immune response. Blood. 2009;113(14):3333–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Chu S, Zhu X, You N, Zhang W, Zheng F, Cai B, Zhou T, Wang Y, Sun Q, Yang Z, Zhang X, Wang C, Nie S, Zhu J, Wang M. The fab fragment of a human Anti-Siglec-9 monoclonal antibody suppresses LPS-induced inflammatory responses in human macrophages. Front Immunol. 2016;7:649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Mamat U, Wilke K, Bramhill D, et al. Detoxifying Escherichia coli for endotoxin-free production of recombinant proteins. Microb Cell Fact. 2015;14:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.von Gunten S, Schaub A, Vogel M, Stadler BM, Miescher S, Simon HU. Immunologic and functional evidence for anti-Siglec-9 autoantibodies in intravenous immunoglobulin preparations. Blood. 2006;108:4255–4259. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Gunten S, Yousefi S, Seitz M, Jakob SM, Schaffner T, Seger R, et al. Siglec-9 transduces apoptotic and nonapoptotic death signals into neutrophils depending on the proinflammatory cytokine environment. Blood. 2005;106:1423–1431. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biedermann B, Gil D, Bowen DT, Crocker PR. Analysis of the CD33-related siglec family reveals that Siglec-9 is an endocytic receptor expressed on subsets of acute myeloid leukemia cells and absent from normal hematopoietic progenitors. Leuk Res. 2007;31:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayes PA, Hance KW, Hoos A. The promise and challenges of immune agonist antibody development in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17(7):509–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Weiss A, Manger B, Imboden J. Synergy between the T3/antigen receptor complex and Tp44 in the activation of human T cells. J Immunol. 1986;137(3):819–825. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.137.3.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Takahashi T, Ishida Y, Sakaguchi S. Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(2):135–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Kjaergaard J, Tanaka J, Kim JA, Rothchild K, Weinberg A, Shu S. Therapeutic efficacy of OX-40 receptor antibody depends on tumor immunogenicity and anatomic site of tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2000;60(19):5514–5521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bulliard Y, Jolicoeur R, Zhang J, Dranoff G, Wilson NS, Brogdon JL. OX40 engagement depletes intratumoral Tregs via activating FcγRs, leading to antitumor efficacy. Immunol Cell Biol Nature Publishing Group. 2014;92:475–480. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.•• Heinz Laubli, Simone Schmitt, Christoph Esslinger. Anti-Siglec-9 antibody molecules. Patent WO2021094545. 2021. This study describes Siglec-9 blocking antibody which activates CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as increased cytotoxicity of NK92 cell line against chronic myelogenous leukemia, K562 cells. Additionally, they showed that weak binding anti-Siglec-9 clone 5C6 demonstrated no functional activity.

- 44.Zhang D, Goldberg MV, Chiu ML. Fc engineering approaches to enhance the agonism and effector functions of an Anti-OX40 antibody. J Biol Chem Am Soc Biochem Mol Biol Inc. 2016;291:27134–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Vaddepally RK, Kharel P, Pandey R, Garje R, Chandra AB. Review of indications of FDA approved immune checkpoint inhibitors per NCCN guidelines with the level of evidence. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(3):738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Ahmed SR, Petersen E, Patel R, Migden MR. Cemiplimab-rwlc as first and only treatment for advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2019;12(10):947–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Barone A, Hazarika M, Theoret MR, et al. FDA approval summary: pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(19):5661–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Zhang Q, Huo GW, Zhang HZ, Song Y. Efficacy of pembrolizumab for advanced/metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis. Open Med (Wars). 2020;15(1):447–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Norsworthy KJ, Ko C-W, Lee JE, Liu J, John CS, Przepiorka D, et al. FDA approval summary: Mylotarg for treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia. Oncologist Oxford Univ Press (OUP) 2018;23:1103–1108. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao H, Woods EC, Vukojicic P, Bertozzi CR. Precision glycocalyx editing as a strategy for cancer immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:10304–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.• Wu Y, Huang W, Xie Y, Wang C, Luo N, Chen Y, Wang L, Cheng Z, Gao Z, Liu S. Siglec-9, a putative immune checkpoint marker for cancer progression across multiple cancer types. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9:743515. This study highlights the broad application of Siglec-9 as an immune checkpoint target across various cancers. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Lim J, Puan KJ, Wang LW, et al. Data-driven analysis of COVID-19 reveals persistent immune abnormalities in convalescent severe individuals. Front Immunol. 2021;12:710217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature Nature Research. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chodorge M, Züger S, Stirnimann C, Briand C, Jermutus L, Grütter MG, et al. A series of Fas receptor agonist antibodies that demonstrate an inverse correlation between affinity and potency. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1187–1195. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hudak JE, Canham SM, Bertozzi CR. Glycocalyx engineering reveals a Siglec-based mechanism for NK cell immunoevasion. Nat Chem Biol Nature Publishing Group. 2014;10:69–75. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khatua B, Bhattacharya K, Mandal C. Sialoglycoproteins adsorbed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa facilitate their survival by impeding neutrophil extracellular trap through siglec-9. J Leukoc Biol Wiley. 2012;91:641–655. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0511260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodrigues E, Jung J, Park H, et al. A versatile soluble siglec scaffold for sensitive and quantitative detection of glycan ligands. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Mimoto F, Katada H, Kadono S, Igawa T, Kuramochi T, Muraoka M, et al. Engineered antibody Fc variant with selectively enhanced FcγRIIb binding over both FcγRIIaR131 and FcγRIIaH131. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2013;26:589–598. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzt022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diebolder CA, Beurskens FJ, de Jong RN, Koning RI, Strumane K, Lindorfer MA, et al. Complement is activated by IgG hexamers assembled at the cell surface. Science (1979). Am Assoc Adv Sci. 2014;343:1260–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during the current review are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.