Abstract

Purpose

Violence against healthcare professionals has become an emergency in many countries. Literature in this area has mainly focused on nurses while there are less studies on physicians, whose alterations in mental health and burnout have been linked to higher rates of medical errors and poorer quality of care. We summarized peer-reviewed literature and examined the epidemiology, main causes, consequences, and areas of intervention associated with workplace violence perpetrated against physicians.

Recent Findings

We performed a review utilizing several databases, by including the most relevant studies in full journal articles investigating the problem. Workplace violence against doctors is a widespread phenomenon, present all over the world and related to a number of variables, including individual, socio-cultural, and contextual variables. During the COVID-19 pandemic, incidence of violence has increased. Data also show the possible consequences in physicians’ deterioration of quality of life, burnout, and traumatic stress which are linked to physical and mental health problems, which, in a domino effect, fall on patients’ quality of care.

Summary

Violence against doctors is an urgent global problem with consequences on an individual and societal level. This review highlights the need to undertake initiatives aimed at enhancing understanding, prevention, and management of workplace violence in healthcare settings.

Keywords: Violence, Physicians, Workplace, Burnout, Psychiatry, Emergency departments

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines physical and psychological workplace violence as “incidents where staff are abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances related to their work, including commuting to and from work, involving an explicit or implicit challenge to their safety, well-being or health” [1].

Workplace violence is a worldwide problem with a higher incidence in sectors requiring intense human interactions, of which the healthcare sector is a prominent example. For the World Medical Association, violence against healthcare professionals is “an international emergency that undermines the very foundations of health systems and impacts critically on patient’s health” [2]. This is not a new phenomenon, as written in 1892 by the anonymous author of a landmark article on violence against doctors, which at that time seemed to be an infrequent phenomenon “[…] no physician, however conscientious or careful, can tell what day or hour he may not be the object of some undeserved attack, malicious accusation, black mail or suit for damages; ‘ for sufferance is the badge of all our race” [3].

During the last years, the number of violent acts against healthcare workers has incredibly increased [4••], although the real dimension is not known because of significant under-reporting [5•]. Recent research points out that as much as 48% of non-fatal workplace violence incidents take place in healthcare settings, and up to 50% of healthcare workers experience some form of violence in their career [6], especially but not only from patients with psychiatric disorders [7, 8•, 9].

In general, healthcare professionals (mainly nurses) have a 16 times increased risk of violence as compared to workers in other sectors and are four times more likely to require time away from work as a result of violence [10], with some more recent data concerning specifically violence against physicians.

While the majority of incidents are verbal, a considerable amount is constituted by physical assault, battery, stalking, or sexual harassment (Table 1). Also, a distinction should be made between affective violence (or defensive violence) which, according to several authors, mobilizes the emotional “fight or flight” response system, towards evading a stimulus that is perceived as a threat; while predatory violence (or intentional, premeditated violence) involves planning a deliberate attack on a target, often one who is the subject of some type of grievance [11].

Table 1.

Type of violence against physicians in the different settings

| Physical violence |

|---|

| Physical assaults (e.g., open violent behavior, use of weapons) |

| Aggression (e.g., kicking, spitting, scratching, hitting, grabbing, biting, throwing objects) |

| Sexual violence |

| Harassment |

| Assault |

| Intimidation |

| Verbal remarks |

| Psychological violence |

| Verbal abuse |

| Intimidation behaviour |

| Verbal threats |

| Ethnical and racial harassment |

| Reputation smearing |

| Mobbing |

| Bullying |

Aggressions in the workplace have been associated with somatic injuries, but also with psychological consequences, such as burnout, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. Literature in this area has mainly focused on experiences of violence against nurses (e.g., [12]), while there are less studies on physicians, in whom the secondary emotional distress and burnout are important [13, 14•] and have been linked to higher rates of medical errors and poorer quality of care [15•]. The figures of patient-initiated violence against doctors are globally impressively high, to the point that some authors begin to refer to it as a “viral epidemic” [16], if not a “pandemic” [17].

On this background, the main aim of this narrative review is to focus attention on workplace violence against physicians perpetrated by patients or families, which falls into the wider category of type II workplace violence, referred to as client-on-worker-violence [18]. We examined both the prevalence in different countries (and across specialties) to account for possible culture- or healthcare system-driven differences and prevention and management strategies. As a second aim, we dedicated a section to the current COVID-19 pandemic, to explore whether this unexpected emergency and the associated widespread disinformation and politicization has increased hostile reactions and influenced the patterns of patient-initiated violence against physicians.

Methods

We searched electronic databases of PubMed and Google Scholar, with various combinations of keywords, [(hospital * OR healthcare OR health* OR doctor * OR physician * OR surgeon *) AND (violence OR aggression * OR harassment)]. Sources of information used for literature search were PubMed, Cochrane Library, Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE), and PsychINFO. In addition, a manual search was conducted based on literature references. We focused on recent articles in English language from all over the world. Full-text review of the included studies was carried out, and data were extracted on study’s characteristics and outcomes. All the possible disagreements were resolved with consensus in the presence of senior authors (RC, LG).

Results

The analysis of the literature allowed us to extrapolate data that can be separated into the following: (1) epidemiological data regarding the prevalence of violence against physicians, (2) causes and risk factors for violence in these settings, (3) consequences of healthcare related violence, and (4) strategies to prevent or limit violence against physicians.

Epidemiology of Aggression and Violence Against Physicians

Analysis of rates of violence against doctors is limited by the variability of findings and inconsistences in the definition of violence categories (e.g., “verbal aggression,” “threats,” “physical assault,” “battery”), as well as heterogeneity of measures, which may compromise reliability among studies. Therefore, reports of workplace violence against physicians vary greatly, although there is a consensus of high prevalence in critical care services, where rates can reach over 85% [19]. This is especially true for emergency departments (EDs), intensive care units (ICUs), psychiatry, and mental health units (MHUs), which represent worldwide the most frequent theaters of patient-initiated violence [20–22] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primary studies of prevalence of workplace violence in different areas of the world

| Authors and year | Country | Healthcare setting | Number of participants | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American College of Emergence Physicians 2018 | USA | EDs | > 3,500 physicians | 47% physically assaulted; 60% of them in the previous year |

| Ferri et al. 2016 | Italy | General hospital | 745 HCPs | 45% exposed to violence; 12% of them physicians |

| Vorderwülbecke et al. 2015 | Germany | Primary care | 831 physicians | 91% exposed to violence in their career; 73% in the previous year |

| De Jager et al. 2019 | Belgium | Hospital and community | 3726 physicians | 37% exposed to violence in the previous year; 33% verbal, 30% psychological, 14% physical, 10% sexual |

| ONAM Workgroup 2018 | Spain | Private and public hospital and community | 2419 physicians | Of 2419 physicians reporting some form of violence, 51% were men. Primary care most interested area (54%). Public sector most affected (89%) |

| Jatic et al. 2019 | Bosnia Herzegovina | Primary care |

558 HCPs 181 physicians |

Overall violence prevalence: 90.3% Physicians more exposed than nurses to indirect physical violence |

| Sharma et al. 2019 | India | Tertiary care hospital | 295 HCPs |

53% of junior residents and 61% senior residents exposed to verbal violence Physical violence mostly against residents with less than 5-year experience |

| Jain et al. 2021 | India | General hospital | 307 residents |

86% exposed to violence. 94% of episodes: verbal Most frequent reason: patient’s death |

| Kaur et al. 2019 | India | Hospital and community | 617 physicians | 77% exposed to violence in their career |

| Singh et al. 2019 | Uttar Pradesh | General hospital | 305 residents | 69.5% exposed to violence; 70% verbal; 47.2% physical; 20% threats |

| Ahmed et al. 2017 | Pakistan | Primary care | 524 physicians | 85% exposed to mild, 62% to moderate, 38% to severe violence in the previous year |

| Fang et al. 2020 | Northern China | General hospital | 884 physicians and 537 residents | 73% of physicians and 24.8% of residents exposed to psychological violence; 10.9% of physicians and 1.5% of residents exposed to physical violence in previous year |

| Tian et al. 2020 | China | General hospital | 934 physicians | 16% exposed to physical violence; 50% to emotional violence; 30% to threats; 19.1 to verbal sexual harassment; 7.8% to sexual assault |

| Cheung et al. 2020 | Macau | Hospital and community | 107 physicians | 38.3 exposed to verbal violence; 3.7 to physical violence; 12.1% to bullying; 3.7 to sexual harassment; 3.7 to racial harassment |

| Kaya et al. 2016 | Turkey | EDs | 112 physicians | 76.6% exposed to violence |

| Oğuz et al. 2020 | Turkey | Paediatric clinic | 75 physicians | 56% exposed to violence in the previous year. 8.8% incidents physical. Physicians more exposed than other HCPs |

| Çevik et al. 2020 | Turkey | Hospital and community | 948 physicians | 83% exposed to violence in their career. 72% verbal |

| Hamdam et al. 2015 | Palestine | EDs | 142 physicians | 88% exposed to verbal violence and 29% to physical violence in the previous year |

| Nevo et al. 2017 | Israel | Hospital and community | 145 physicians | 59% exposed to verbal violence and 9% to physical violence in the previous year |

| Shafran-Tivka et al. 2017 | Israel | General hospital | 230 physicians | 27% exposed to verbal threats; 74% to other forms of verbal violence in the previous 6 months |

| Mohamad et al. 2021 | Syria | General hospital | 1226 residents | 85% exposed to violence in the previous year |

| Alhamad et al. 2021 | Jordan | General hospital | 969 physicians | 63% exposed to violence in the previous year. 62% verbal;6% physical; 32% non specified |

| Al Amazi et al. 2020 | Saudi Arabia | General hospital | 351 HCPs | 59% of physicians exposed to violence. Physicians the most exposed HCPs |

| Kasai et al. 2018 | Myanmar | General hospital | 196 physicians | 8.7% exposed to verbal violence and 1% to physical violence in the previous year |

| Elamin et al. 2021 | Sudan | General hospital | 387 physicians | 50.4% exposed to in the previous year. 92% verbal |

| Seun-Fadipe et al. 2019 | Nigeria | General hospital | 99 physicians | 44.4% exposed to violence in a 7-month time span |

| Akami et al. 2019 | Nigeria | Psychiatric hospital | 30 physicians | 29% exposed to physical violence in the previous year. 73% in their career |

| Olashore et al. 2018 | Botswana | Psychiatric hospital | 10 physicians | 40% exposed to violence in their career |

EDs emergency departments, HCPs healthcare professionals, ONAM National Observatory of Aggression to Physicians

North America

In U.S. general hospitals, violence from patients constitutes a serious occupational hazard as confirmed by the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics reports, outlining that between 2011 and 2013 nearly 75% of 24,000 workplace assaults per year occurred in the healthcare sector (6). These data, however, might reflect only the tip of the iceberg, as it has been found that the actual prevalence of workplace violent incidents was as much as three times that reported by the federal survey, since verbal incidents are not recorded [23]. As mentioned above, violent incidents increase further when focusing on high-exposure settings, including EDs, as confirmed by the American College of Emergency Physicians (5), and MHUs, where rates of workplace physical violence against physicians appear even higher than those in EDs, with 40% of psychiatrists reporting physical assaults over the course of their careers [24].

Europe

In Europe, violence rates against physicians are equally worrisome.

In Germany, data show that about 90% of 831 doctors had faced some form of aggression in their career and about 70% in the previous year [25]. A similar overall prevalence of violence was found among 558 primary healthcare professionals in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Compared to nurses, physicians were more often subjected to humiliation, false allegations, rumors, etc., and among physicians, women experienced verbal violence more often than their male counterparts [26].

In Italy, hospital violence is common [27], especially among psychiatrists, who have been reported at high risk for verbal aggression, injuries, threats with dangerous objects, stalking, and physical aggression [28]. In contrast, Italian ED physicians were reported to experience violence less frequently than other professionals [29]. The risk of death of doctors should be also considered. In a 30-year review of homicides of Italian doctors in the workplace, 21 were registered: in about half of the cases, the perpetrator was not affected by any mental disorders and the killer was one of the doctor’s patients; in about one-third, he/she was a patient’s relative, and in one-fifth, a patient at first consultation [30•].

In Spain, 2,419 episodes of different forms of aggression against physicians were registered during a 5-year period. The scant denunciation by physicians in Spain contributes, as for the other countries, to the underestimation of the real dimensions of the phenomenon [31].

Asia

In the developing countries, alarming incidents of all forms of violence against doctors have been reported in the last decades, to the point that in some states, safety of doctors has become a critical issue [32, 33]. Globally, India is the “leading country” regarding violence against physicians [34] with data indicating that up to 75% of doctors face some form of violence in their working life [35] and a higher prevalence among physicians with less than 5 years of experience [36–38]. Similar data were reported in Pakistan [39].

High prevalence rates of both physical and psychological violence against physicians have been documented in Chinese hospital settings, where aggressive episodes appear rising over time [40••], including murder of physicians [41], although accurate statistics are lacking [42•, 43–47]. China is also the theater of a culture-based phenomenon known as Yi Nao, literally defined as “health care disturbance,” which is perpetrated by gangs with a designated leader who threatens and assaults hospital professionals, damage equipment, and prevent normal medical activities. The most frequent aim of Yi Nao is to force hospitals to reduce medical care costs. Yi Nao has increased tenfold over the years with 118,000 Yi Nao incidents across the country just in 2015 [48••].

High rates of violence against physicians have been reported in Turkey (more than 70% of specialty physicians reported some form of violence) [49, 50]; in Palestine, on both West Bank and Gaza Strip EDs, especially among younger personnel [51]; in Israel [52]; in Jordan [53]; in Syria [54]; and in Iraq [55, 56]. Data showed however, as in other countries, that only 16.4% of assaulted workers reported the violent acts to the authority because of the perception of uselessness and fear of negative consequences [57].

Africa

In Africa, there is still paucity of research [58]. In a cross-sectional study carried out in 2020 in Sudan [59], 50% of doctors reported they had been victims of some form of violence (mainly verbal violence and, as for other countries, among younger doctors). A Nigerian study showed similar findings among physicians in general [60] while the prevalence of physical violence against mental health professionals showed that 33% of the doctors report physical assaults in the previous 12 months and 73% in their whole career [61]. Slightly lower but still significant figures were reported in Botswana [62].

Violence Against Physicians in the COVID-19 Period

After the WHO declaration of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) secondary to the SARS-CoV2 virus, as an international public health emergency [63], data were presented regarding the high risk for frontline clinicians to be exposed to negative consequences, including infections, fatigue, anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion, burnout, and also workplace violence [64, 65, 66•]. Although, initially, physicians and nurses were celebrated as heroes, there is evidence of increased violence against health professionals associated with the COVID-19 pandemic [67••].

This is not a new phenomenon, since historically, likelihood of attacks from patients and/or families becomes higher as clinicians need to implement unwelcome yet essential prevention and control measures, such as quarantining patients, or banning family visits, both of which may disrupt communications between staff and patients/families.

Studies carried out in different countries, such as Brazil [68], Egypt [69], Jordan [70], and Canada [71], showed that key correlates of COVID-19-related workplace violence (including being beaten, threatened, and verbally offended), along with working in MHUs or EDs, were the following: being involved in direct care of infected patients; having infected family/friends/colleagues; not having children or partners; and a high workload. Similar data were reported in India and Pakistan [72, 73] Iraq [74], Mexico [75], and Peru [76], but not in Israel where at least at the beginning of the pandemic, there was a general decrease of violent incidents in comparison to the corresponding period in 2019 [77].

According to the World Medical Association, the figures of violence vary from country to country. [78]. However, although violence rates are higher in conflict zones and developing countries, the phenomenon does not spare high-income, industrialized, and peaceful countries, such as France, the UK, Australia, and the USA [79, 80].

Causes and Consequences of Violence Against Physicians

The development and implementation of effective workplace violence prevention programs that account for risks faced by physicians require the assessment of causes, risk factors, and consequences of violence against physicians.

Causes

There are several causes and risk factors favoring violence against physicians. Some include professional and individual physician-related factors; some are related to communication and doctor-patient relationship issues; some are related to the patients and their personal or clinical condition; finally, a complex intertwining of social, organizational, and political factors should be also considered [81, 82•] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors increasing the risk of occupational violence in health care settings (from Kumari et al., modified)

| Workplace and policy issues | Patient factors | Physicians factors | Doctor-patient relationship | Sociocultural issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-Poor demarcation between staff-only area and patient area -Overcrowded, uncomfortable, or noisy waiting rooms -Poor access to exits, poor lighting, blind spots without surveillance -Unsecured furnishings which could be used as weapons -Poor policies and work practices including understaffing, cutting staff resources, no investment in staff training, or development of guidelines -Increased bureaucracy |

-Medical causes (e.g., delirium, intoxication, substance abuse) -Psychosocial stressors -Previous negative experiences with healthcare -History of violence -Psychiatric disturbances including personality disorders -Interpersonal style of control or dominance -Poor impulse control -Family conflicts |

-Lack of staff training in communication skills, treatment of conditions associated with violent behavior, de-escalation techniques -Working alone -Limited experience -Poor control on one’s own emotions (e.g., anger, anxiety, frustration) -Emotional exhaustion, burnout, or psychological distress symptoms |

-Patients: frustration, perception of not being respected, not being listened to, or being treated unfairly -Increased waiting times -Physicians: detachment and interpersonal frictions -Poor customer services |

- Poverty, unemployment, and social marginalization - Language barriers - Cultural differences - Reduced respect for authority, negative media messages - Population density, especially in metropolitan areas - Violence as a way to receive attention |

Working with health authorities to implement policies and guidelines for the prevention and management of violence (e.g., education programs, specific procedures, and guidelines)

Among physician-related factors, lack of communication skills and empathy, unkindness, and negative or hurtful comments clearly predispose the patient’s reaction. Also, physician younger age, inexperience, gender (i.e., female), and not knowing how to de-escalate and when and how to escape are part of the problem. Regarding the interpersonal doctor-patient relationship, dissatisfaction with prescriptions and treatment methods, disagreement with doctors, and unawareness of own body language are frequent initiators of violence.

Among patient factors, personality traits predisposing to aggression, history of violence, the influence of drugs and alcohol, confusion states, high levels of stress, and accumulation of negative life events reduce the threshold to aggression. Also, long waiting time for diagnostic examinations, treatments, and physician consultation may increase dissatisfaction, with risk of irritability, aggressivity, and, eventually, escalation to violent behaviors.

As far as organizational factors are concerned, certain settings (as said, EDs, MHUs), lack of resources and of staffing (e.g., staff reduction for budget reasons), and poor workplace conditions (e.g., architectural design of location, uncomfortable physical conditions of the rooms) are correlated to an increased risk of violence [83]. Also, action on the hospital administration to solve several problems (e.g., lack of support for staff, reduced interest for the staff mental health, burnout, and other psychological job-related complications; lack of violence-prevention programs, staff empowerment, and shared governance) is important, although data about the efficacy of intervention are contrasting not showing [84•] or showing [85•] positive effects.

A special topic has to do with “political” factors that can create conflicts in the population through confusing messages. From one side, politicians (and political parties) tend to announce and proclaim the effectiveness and efficacy of the healthcare system and the powerful investment in public health; on the other side, there is no country where the funds to the healthcare system are cut by the governments, with reduction of resources and a negative influence of on the quality of care. This can cause the request by citizens to have a perfect service fixing all problems, while in reality, what they have to face is characterized by limits and the deficits of the system itself (e.g., long waiting lists to receive attention; burned-out staff).

A further political implication has been made evident in COVID time when the public policy stances taken by healthcare organizations, including physicians or groups of physicians, can place physicians into the crosshairs of highly charged, divisive, controversial political struggles and in turn can increase the likelihood of affective and predatory violence. Specific examples of “politically motivated” or “politically related” violence against physicians might include the following:

Escalating confrontations over masks, vaccination status, arguments with patients demanding care using medications that lack scientific support for treatment of COVID, and refusal of acute care for COVID due to patient’s disbelief in COVID

Physician burnout in the face of dealing with the front-line consequences of these political divides, leading to diminished reserve and greater risk of arguments with patients resulting in affective violence

Increased targeting of physicians who perform abortions in the wake of increased controversy about legal changes related to abortion rights, as has recently occurred in the USA

Increased targeting of physicians working in gender reassignment in the context of increased controversy about gender identity issues

Lastly, culturally and socially, a negative attitude towards healthcare providers has to do with a social stance of unlimited expectations of health and longevity and the implicit belief that technologic progress has given to medical science a curative solution for all the health problems. As a result, both individual patients and society may present a splitting mechanism towards doctors, with an intense de-idealization when the reality is that invulnerability and immortality are not part of the world and that a number of health problems cannot be “fixed” (according to the often forgotten message that medicine, as the science of the human, cures sometimes, relieves often, but should comforts always) [86].

Consequences

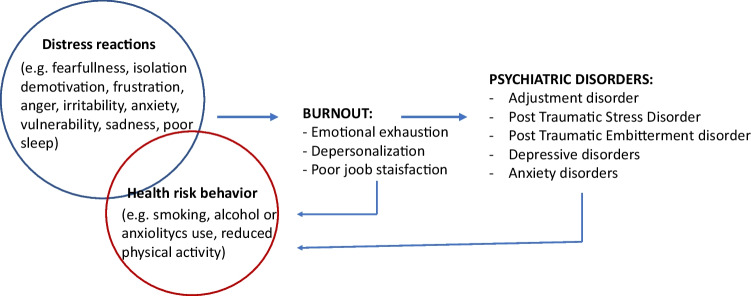

Violence incidents bear consequences that go further than the moment of exposure, both on a physical and, sometimes most importantly, on a psychological and moral basis, with a potential influence not only on the individual but also on their family and social relationships (spillover effect). In addition, repeated episodes of aggression, or a major traumatic one, may dramatically erode patient-physician trust and lead to poorer health outcomes [87•, 88] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Consequences of exposure to violence incidents

In this regard, loss of occupational performance has been reported as the most common result of exposure to violence, with changes in attitudes and decision making and increase of defensive medicine behavior (e.g., excessive prescriptions of drugs and investigations, inappropriate referrals, and consultation requests) [89, 90].

Solid data document that physicians who faced violence are at a great risk to develop psychological problems, such as depression, insomnia, post-traumatic stress symptoms with flashbacks, avoidance and hypervigilance, intense fear episodes, and anxiety, leading to deterioration of quality of life, absenteeism, and, in extreme circumstances, decision to quit the medical profession. Loss of self-esteem and feelings of shame, along with a sense of lowered safety and defeat, can occur as long-term sequelae of cumulative minor violence exposures or of a major dramatic episode. These consequences have been shown significantly higher in cases of physical violence or sexual harassment than in cases of verbal abuse and more in women than in men [91]. Both verbal and physical violence, however, impacted on subjective sleep quality, tobacco consumption, headache, eating disorders, and lifestyle deterioration, with psychological distress partially mediating the relationship between work-related violence and health damage [92, 93•, 94].

Burnout symptoms (i.e., emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and detachment in the relationship with patients, demotivation, and loss of job satisfaction) are statistically more frequent in physicians subjected to verbal and physical violence [95•, 96].

A further form of psychological reaction in physicians’ victims of violence could be embitterment and its psychopathological form, defined post-traumatic embitterment disorder (PTED) [97••]. Unlike PTSD, PTED is characterized by the fact that the event is experienced as unjust, as a personal insult, and as a violation of basic beliefs and values, with a predominant sense of embitterment and emotional arousal when reminded of the event, as the key core psychological components of the disorder. Also, mood impairment; downheartedness unspecific somatic complaints; phobic symptoms; social withdrawal; reduction of energy, motivation, and drive; and increase in irritability with possible aggression towards oneself and others can be present While studies have been conducted about these clinical conditions in the workplace, more data are needed regarding embitterment and PTED secondary to violence against physicians [98].

Prevention and Management of Workplace Violence in Healthcare Setting

Although most incidents can be avoidable, studies on violence against physicians have been designed to quantify the problem, and few have described experimental methods to prevent such violence. Three recent critical reviews of the literature documented moderate evidence that integrated prevention programs might decrease the risks of patient-initiated violence [99•]. These programs incorporate at least two different areas of intervention, based on the most frequent causes of violence, including both organizational and the healthcare staff levels (Table 4).

Table 4.

Possible interventions for physicians exposed to violence

| Training and education on violence prevention (e.g., communication skills, non-violent crisis interventions, de-escalation techniques) and treatment (e.g., use of tranquilizers, restrains) tailored for physicians |

| Correct attention to high-risk patients (e.g., patients with drug or substance intoxication, confusion); correct interpretation of signs of aggressivity |

| Enhanced security measures in the clinical settings (e.g., help or panic buttons, direct telephone lines to security and police), safety environment (e.g., lighting, mirrors, cameras) |

| Development of safety standards within healthcare facilities (e.g., protocols, mandatory reporting of events, zero tolerance of violence (violence is not part of the job!) |

| Timely response after violence against physicians (e.g., debriefing, psychological assessment, and/or psychiatric treatment) |

First Level of Intervention

A first level of action concerns the organizational area, from simple interventions to more specific ones. Excessive waiting time for care and clients’ disinformation about the reasons for waiting has been documented as a key factor kindling violence, along with lack of violence prevention measures, and lack of drugs or needed services is responsible for at least 15% episodes. Therefore, leaflets, clear information about the possible problems in the daily organization, and attention to comfort are part of these procedures. Hospitals which offer more comfortable physical conditions (e.g., private rooms with an air-conditioning system, or television) show lower rates of patient-initiated violence towards physicians (violence inhibitors). In facilities where procedures and culture of reporting are lacking, violence episodes occur significantly more frequently than in those where reporting systems are effective [100••, 101•]. The issue of under-reporting of violent incidents is extremely important and can be caused by several reasons which should be carefully examined in order to make the whole care system more aware. With respect to this, one reason for physicians and nurses to not report violence against them is because of previous experience of no action taken (e.g., administration tending to minimize these phenomena to protect the image of the institute; tendency to accept that violence is part nurses’ and physicians’ work environment); fear of the consequences (e.g., further threats or wish to revenge from the perpetrator if legal reports are made, worry or guilt feelings to have done mistakes in the relationship with the patient); and lack of management support (e.g., tendency to consider this as a problem of the single individual as a scapegoat, rather than a problem of the system) [15•]. Prompting healthcare professionals to always report incidents in a non-judgmental way and disseminating a policy based on protecting the staff (e.g., “violence is not part of the job” initiative in the USA) [6] increase the chances to make violence prevention programs more effective. More specific infrastructure changes, including high-security systems, cameras, alarm systems, improved lighting, rapid access to police, or hospital security, are a necessary part of the organization of healthcare systems, both in clinics and hospitals.

At organizational level, it is also necessary to consider changes in politics, culture, and society, in both the hospital and the media communication, which plays a key role in the public perception of the healthcare system. Political factors, such as the presence or absence of an effective public healthcare system, are another variable at stake: patients’ and families’ heightened anxiety about the disease and finance difficulties in sustaining the cost of healthcare are an important component of violence initiation.

Second Level of Intervention

A second area of intervention targets physician-related risk factors of violence and aims at promoting behavioral changes. In general, an inappropriate staff attitude can account for up to 20% of cumulative rates of physical and verbal aggression episodes in ICUs [102, 103]. Tailored training initiatives in self-awareness, communications skills, de-escalation techniques, improvement of staff-patient, and inter-staff relationships are necessary. After a violent aggression, debriefing, regular follow-up sessions, and psychological support should be performed with the aim to acknowledge and reassure not only the victim, but also the entire staff. A tense and unempathetic working atmosphere, dissatisfaction, and feelings of distress or fear, burnout, and low-quality interactions with colleagues are, in fact, further risk factors of violence exposure in physicians. The recognition of the difference between interventions to prevent or mitigate acts of affective violence versus predatory violence is also important.. Therefore, in the healthcare system, in the prevention of predatory violence, one of the most important concepts is that individuals who perpetrate such violence usually exhibit a variety of behavioral warning signs amidst numerous risk factors for targeted violence in the lead up to the ultimate act of violence. Thus, the capacity to recognize warning signs of violence and how to deal with should be part of training. Of course, an adequate number of staff personnel should be warranted, since not only the quality of training but also the necessary number of resources is important if a correct and complete response to patients’ needs is the aim of the system.

Last, as previously said, training and intervention should focus on the tendency of physicians not to report the aggression. Being victims of violence (therefore a bad act) when doing one’s own profession of care (therefore a good act) is a cause of sense of injustice that can cause not only burnout (i.e., emotional exhaustion, poor personal accomplishment, detachment towards patients) but demoralization and embitterment. Programs revolving around a “zero tolerance” policy that seeks to share a workplace culture of awareness and safety, “see something, say something – then we can do something [to stop something bad from happening]”, will help the doctor to work through his/her possible sense of guilt or shame and victimization.

Discussion

This review examined violence against physicians from a multifaceted point of view, highlighting the complexity of a phenomenon whose roots are to be found in intertwined cultural, societal, and organizational factors. A worldwide widespread and disturbing pattern of violence towards physicians is in fact occurring, and the medical profession, dignified and valued in the past, seems to be losing not only its sacredness, but even its reputation [104].

Finding a solution to invert this trend is not an easy task, and the few studies that have focused on interventions to reduce violence against physicians have highlighted the unlikelihood of finding a simple, one-size-fits-all approach, since the problem is multidimensional and extremely complex.

A major obstacle appears to be the underestimation of the phenomenon. As said, a number of doctors subjected to violence do not report the incident, and a high percentage of those who report decide to not proceed nor undertake any legal action, frequently considering any acting useless.

The absence of standard procedures for reporting violence and the lack of any encouragement to disclose violence events play a further deterrent role. Many hospitals have neither structured policies/procedure to prevent and manage violent abuses by patients, nor comprehensive training programs on workplace violence. In this light, physicians’ safety appears to assume a lower priority compared with patient safety, and even when present, programs are designed and conceived for patient safety—not worker safety—as the primary goal.

In the paucity of data that define effective steps to prevent violence against physicians, approaches to the problem should be undertaken at various levels. Legislators should consider effective consequences for violence against healthcare workers as a special class of offense; incident reporting procedures should be adopted, and physicians are encouraged to overcome fear of stigmatization and violence acceptance culture. Training programs and the implementation of cost-effective, evidence-based solutions should be ensured.

Our review shows some limitations. First, results presented here are drawn from a literature synthesis and therefore share the limits of the original research, such as the risk of under-reporting, the lack of homogeneity in the definition of violence, and the fact that nearly every study was based on voluntary retrospective surveys, an approach that risks both selection and recall bias. Another important element concerns the subjectivity of physicians, as the interpretation of the episodes of aggression can vary among the victims. A further consideration is that there is not a unique tool (e.g., questionnaire, interview, checklist) used to evaluate the phenomenon in the included studies. Thus, while the impact of violence can be measured by using traditional symptomatic scales to measure depression, anxiety, PTSD, or PTED, the development of specific measures for violence is necessary [105].

Conclusion

Violence against physicians is an urgent global problem with consequences on an individual and societal level. Physicians’ deterioration of quality of life, burnout, and traumatic stress are linked to physical and mental health problems, with poor job performance, low organizational commitment, and turnover intentions which, in a domino effect, fall on patients’ quality of care.

In this light, it appears crucial that, like all other workers, healthcare workers have the right to safety at work acknowledged. Further research should be particularly focused on detecting evidence-based strategies of the prevention and management of violence against physicians under a multidisciplinary perspective.

Acknowledgements

The editors would like to thank Dr. Philip Saragoza for taking the time to review this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Rosangela Caruso, Tommaso Toffanin, Federica Folesani, Bruno Biancosino, Francesca Romagnolo, Michelle B. Riba, Daniel McFarland, Laura Palagini, Martino Belvederi Murri, Luigi Zerbinati, and Luigi Grassieach declare no potential conflicts of interest. Michelle Riba is an editor of Current Psychiatry Reports but did not review this article or make editorial suggestions regarding accepting or rejecting this article. She receives royalties or a stipend from Springer, Guilford, Cambridge, American Psychiatric Press Inc., and Current Psychiatry Reports. Luigi Grassi has received royalties for books from Springer and personal fees from EISAI and ANGELINI for scientific consultancy outside the submitted work.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Complex Medical-Psychiatric Issues

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.WHO Violence against health workers. 2020. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/workplace/en/

- 2.World Medical Association. 73rd World Health Assembly, Agenda Item 3: Covid-19 pandemic response. (2020). Available online at: https://www.wma.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/WHA73-WMA-statement-on-Covid-19-pandemic-response-.pdf. Accessed 7 Jun 2020

- 3.Letter to the editor: assaults upon Medical Men’ JAMA 1892; 18:399–400.

- 4.•• Nowrouzi-Kia B, Chai E, Usuba K, Nowrouzi-Kia B CJ. Prevalence of type ii and type iii workplace violence against physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Occup Environ Med NIOC Heal Organ. 2019;10:99–110. This paper reviews and meta-analyzes prevalence of violence perpetrated against physicians. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.• Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr 28;374(17):1661–9. The review focuses on the current knowledge about workplace violence in various US health care settings, including the prevalence across professions, potential risk factors, and the use of metal detectors in preventing violence. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Guidelines for preventing workplace violence for healthcare and social service workers (osha.gov). OSHA 3148-06R 2016. https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/osha3148.pdf

- 7.Odes R, Chapman S, Harrison R, Ackerman S, Hong O. Frequency of violence towards healthcare workers in the United States' inpatient psychiatric hospitals: a systematic review of literature Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(1):27–46. doi: 10.1111/inm.12812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.• Caruso R, Antenora F, Riba M, Murri MB, Biancosino B, Zerbinati L, et al. Aggressive behavior and psychiatric inpatients: a narrative review of the literature with a focus on the european experience. Curr Psychiatr Rep. 2021 Apr 7;23(5):29. This is a review specifically aiming at illustrating the risk of violence in the general hospital by patients with psychiatric disorder. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Weltens I, Bak M, Verhagen S, Vandenberk E, Domen P, van Amelsvoort T, Drukker M. Aggression on the psychiatric ward: prevalence and risk factors. A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2021 Oct 8;16(10): e0258346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Census of fatal occupational injuries (CFOI). current and revised data. Washington, DC. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshcfoi1.htm

- 11.McEllistrem JE. Affective and predatory violence: a bimodal classification system of human aggression and violence. Aggress Violent Beh. 2004;10:1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2003.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pariona-Cabrera P, Cavanagh J, Bartram T. Workplace violence against nurses in health care and the role of human resource management: a systematic review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2020. 11 2020 Jul;76(7):1581–1593 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Duan X, Ni X, Shi L, Zhang L, Ye Y, Mu H, Li Z, Liu X, Fan L, Wang Y. The impact of workplace violence on job satisfaction, job burnout, and turnover intention: the mediating role of social support. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1164-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.• Mento C, Silvestri MC, Bruno A, Muscatello MRA, Cedro C, Pandolfo G, Zoccali RA. Workplace violence against healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020;51:101381. This paper shows that workplace violence might lead to various negative impacts on health workers’ psychological and physical health, such as increase in stress and anxiety levels and feelings of anger, guilty, insecurity, and burnout.

- 15.• Chakraborty S, Mashreky SR, Dalal K. Violence against physicians and nurses: a systematic literature review. J Publ Health (Berl.). 2022;1–19. 10.1007/s10389-021-01689-6. The paper summarizes the findings of a large series of studies on violence showing that adequate policy making and implementation and operational research are required to further mitigate the episodes of violence especially in emergency departments.

- 16.Reddy IR, Ulkrani J, India V, Ulkrani V. Violence against doctors: a viral epidemic?. Ind J Psychiatr. 2019 Apr;61:S782–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Ghosh K. Violence against doctors: a pandemic in the making. Eur J Inter Med. 2018;50:e9–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pompeii L, Dement J, Schoenfisch A, et al. Perpetrator, worker and workplace characteristics associated with patient and visitor perpetrated violence (type II) on hospital workers: a review of the literature and existing occupational injury data. J Safety Res. 2013;44:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashton RA, Morris L, Smith I. A qualitative meta-synthesis of emergency department staff experiences of violence and aggression. Int’l Emer Nurs. 2018;39:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wuellner SE, Bonauto DK. Exploring the relationship between employer recordkeeping and underreporting in the BLS Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses. Am J Ind Med. 2014;57:1133–1143. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowalenko T, Gates D, Gillespie GL, Succop P, Mentzel TK. Prospective study of violence against ED workers. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:197–205. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Kumar NS, Munta K, Kumar JR, Rao SM, Dnyaneshwar M, Harde Y. A survey on workplace violence experienced by critical care physicians. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2019;23(7):295–301. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenman KD, Kalush A, Reilly MJ, Gardiner JC, Reeves M, Luo Z. How much work-related injury and illness is missed by the current national surveillance system? J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:357–365. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000205864.81970.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly EL, Subica AM, Fulginiti A, Brekke JS, Novaco RW. A cross-sectional survey of factors related to inpatient assault of staff in a forensic psychiatric hospital. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:1110–1122. doi: 10.1111/jan.12609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vorderwülbecke F, Feistle M, Mehring M, Schneider A, Linde K. Aggression and violence against primary care physicians—a nationwide questionnaire survey. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112(10):159–165. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jatic Z, Erkocevic H, Trifunovic N, Tatarevic E, Keco A, Sporisevic L, Hasanovic E. Frequency and forms of workplace violence in primary health care. Med Arch. 2019;73(1):6–10. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2019.73.6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferri P, Silvestri M, Artoni C, Di Lorenzo R. Workplace violence in different settings and among various health professionals in an Italian general hospital: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2016;9:263–275. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S114870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grassi L, Peron L, Marangoni C, Zanchi P, Vanni A. Characteristics of violent behaviour in acute psychiatric in-patients: a 5-year Italian study Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001 Oct;104(4):273–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Civilotti C, Berlanda S, Iozzino L. Hospital-based healthcare workers victims of workplace violence in Italy: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):5860. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.• Lorettu L, Nivoli AMA, Daga I, Milia P, Depalmas C, Nivoli G, Bellizzi S. Six things to know about the homicides of doctors: a review of 30 years from Italy. BMC Publ Health. 2021 Jul 5;21(1):1318. The paper examines the risk of murder among physicians, with the conclusion that doctors should be aware that the risk of being killed is not limited to hospital settings and that their patients’ family members might also pose a threat to them. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.National Observatory of Aggressions to Physicians (ONAM) Workgroup, General Council of Official Medical Associations of Spain (CGCOM). National report on aggressions to physicians in Spain 2010-2015: violence in the workplace-ecological study. BMC Res Notes. 2018 Jun 4;11(1):347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Ranjan R, Singh M, Pal R, Das JK, Gupta S. Epidemiology of violence against medical practitioners in a developing country (2006–2017). 2018;5(3):153–160

- 33.Marwah A, Ranjan R, Singh M, Meeenakshi, Das JK, Pal R. Safety of doctors at their workplace in India perspectives and issues. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2018;9:139.

- 34.Ghosh K. Violence against doctors: a wake-up call. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148(2):130–133. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1299_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh M. Intolerance and violence against doctors. Indian J Pediatr. 2017;84(10):768–773. doi: 10.1007/s12098-017-2435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh G, Singh A, Chaturvedi S, Khan S. Workplace violence against resident doctors: a multicentric study from government medical colleges of Uttar Pradesh. Indian J Pub Health. 2019;63(2):143–146. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_70_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma S, Gautam PL, Sharma S, Kaur A, Bhatia N, Singh G, Kaur P, Kumar A. Questionnaire-based evaluation of factors leading to patient-physician distrust and violence against healthcare workers. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2019 Jul;23:302–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Jain G, Agarwal P, Sharma D, Agrawal V, Yadav SK. Workplace violence towards resident doctors in Indian teaching hospitals: a quantitative survey. Trop Doct. 2021;51(3):463–465. doi: 10.1177/00494755211010005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed F, Khizar Memon M, Memon S. Violence against doctors, a serious concern for healthcare organizations to ponder about. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2017;15(25):3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.•• Lu L, Dong M, Wang SB, Zhang L, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, Li J, Xiang YT. Prevalence of workplace violence against health-care professionals in China: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational surveys. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2020 Jul;21(3):498–509. This is a comprehensive meta-analysis on prevalence of workplace violence among healthcare professionals in China included 47 studies and 81,771 professionals. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Zhang X, Li Y, Yang C, Jiang G. Trends in workplace violence involving health care professionals in China from 2000 to 2020: a review. Med Sci Monit. 2021 Jan 8;27:e928393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Li P, Xing K, Qiao H, Fang H, Ma H, Jiao M, Hao Y, Li Y, Liang L, Gao L, Kang Z, Cui Y, Sun H, Wu Q, Liu M. Psychological violence against general practitioners and nurses in Chinese township hospitals: incidence and implications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):117. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0940-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall BJ, Xiong P, Chang K, Yin M, Sui XR. Prevalence of medical workplace violence and the shortage of secondary and tertiary interventions among healthcare workers in China. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018 Jun;72(6):516-518. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Fang H, Wei L, Mao J, Jia H, Li P, Li Y, Fu Y, Zhao S, Liu H, Jiang K, Jiao M, Qiao H, Wu Q. Extent and risk factors of psychological violence towards physicians and Standardised Residency Training physicians: a Northern China experience. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):330. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01574-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma J, Chen X, Zheng Q, Zhang Y, Ming Z, Wang D, Wu H, Ye H, Zhou X, Xu Y, Li R, Sheng X, Fan F, Yang Z, Luo T, Lu Y, Deng Y, Yang F, Liu C, Liu C, Li X. Serious workplace violence against healthcare providers in China between 2004 and 2018. Front Public Health. 2021;15(8):574765. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.574765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian Y, Yue Y, Wang J, Luo T, Li Y, Zhou J. Workplace violence against hospital healthcare workers in China: a national WeChat-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):582. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08708-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheung T, Lee PH, Yip PSF. Workplace violence toward physicians and nurses: prevalence and correlates in Macau. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(8):879. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.•• Liu T, Tan X. Troublemaking in hospitals: performed violence against the healthcare professions in China Health Sociol Rev. 2021 Jul;30(2):157–170. Very complete review of the phenomenon of Yi Nao in China as a form of violence against physicians and health workers in general. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Kaya S, Bilgin Demir İ, Karsavuran S, Ürek D, İlgün G. Violence against doctors and nurses in hospitals in Turkey. J Forensic Nurs. 2016 Jan-Mar;12(1):26-34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Çevik M, Gümüştakim RŞ, Bilgili P, Ayhan Başer D, Doğaner A, Saper SHK. Violence in healthcare at a glance: the example of the Turkish physician. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2020;35(6):1559–1570. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamdan M, Abu HA. Workplace violence towards workers in the emergency departments of Palestinian hospitals: a cross-sectional study. Hum Resour Health. 2015;7(13):28. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0018-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nevo T, Peleg R, Kaplan DM, Freud T. Manifestations of verbal and physical violence towards doctors: a comparison between hospital and community doctors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):888. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4700-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alhamad R, Suleiman A, Bsisu I, Santarisi A, Al Owaidat A, Sabri A, et al. Violence against physicians in Jordan: An analytical cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16(1): e0245192. 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Mohamad O, AlKhoury N, Abdul-Baki MN, Alsalkini M, Shaaban R. Workplace violence toward resident doctors in public hospitals of Syria: prevalence, psychological impact, and prevention strategies: a cross-sectional study. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00548-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lafta RK, Falah N. Violence against health-care workers in a conflict affected city. Med Confl Surviv. 2019;35(1):65–79. doi: 10.1080/13623699.2018.1540095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haar RJ, Read R, Fast L, Blanchet K, Rinaldi S, Taithe B, Wille C, Rubenstein LS. Violence against healthcare in conflict: a systematic review of the literature and agenda for future research. Confl Health. 2021 May 7;15(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Al Anazi RB, AlQahtani SM, Mohamad AE, Hammad SM, Khleif H. Violence against health-care workers in governmental health facilities in Arar City, Saudi Arabia. ScientificWorldJournal. 2020;20(2020):6380281. doi: 10.1155/2020/6380281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Njaka S, Edeogu OC, Oko CC, Goni MD, Nkadi N. Workplace violence (WPV) against healthcare workers in Africa: a systematic review. Heliyon. 2020;6(9):e04800. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elamin MM, Hamza SB, Abbasher K, Idris KE, Abdallah YA, Muhmmed KAA, Alkabashi THM, Alhusseini RT Mohammed SES, Mustafa AAM. Workplace violence against doctors in Khartoum State, Sudan, 2020. Sudan J Med Sci. 2021;16(2):301–319.

- 60.Seun-Fadipe CT, Akinsulore AA, Oginni OA. Workplace violence and risk for psychiatric morbidity among health workers in a tertiary health care setting in Nigeria: prevalence and correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:730–736. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Akanni OO, Osundina AF, Olotu SO, Agbonile IO, Otakpor AN, Fela-Thomas AL. Prevalence, factors, and outcome of physical violence against mental health professionals at a Nigerian psychiatric hospital. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2019;29(1):15–19. doi: 10.12809/eaap1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olashore AA, Akanni OO, Ogundipe RM. Physical violence against health staff by mentally ill patients at a psychiatric hospital in Botswana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):362. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3187-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.World Health Organization. The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. 2020. Available online at: http://www.hoint.com. Accessed 30 Mar 2020

- 64.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(e203976):6. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao K, Zhang G, Feng R, Wang W, Xu D, Liu Y, et al. Anxiety, depression and insomnia: a cross-sectional study of frontline staff fighting against COVID-19 in Wenzhou, China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292(113304):4. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.• Devi S. COVID-19 exacerbates violence against health workers. Lancet. 2020;396(10252):658. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31858-4. This paper reports that hundreds of incidents of violence and harassment occurred in healthcare settings as a consequence of COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.•• Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;S0889–1591:30523–30527. Study reporting the psychological and physical consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Bitencourt MR, Alarcão ACJ, Silva LL, Dutra AdC, Caruzzo NM, Roszkowski I, et al. Predictors of violence against health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: a crosssectional study. PLoS ONE 2021;16(6):e0253398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Arafa A, Shehata A, Youssef M, Senosy S. Violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study from Egypt. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2021 Sep 30:1–7. 0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Ghareeb NS, El-Shafei DA, Eladl AM. Workplace violence among healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in a Jordanian governmental hospital: the tip of the iceberg. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28(43):61441–61449. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15112-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cukier A, Vogel L. Escalating violence against health workers prompts calls for action. CMAJ. 2021;193(49):E1896. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1095980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McKay D, Heisler M, Mishori R, Catton H, Kloiber O. Attacks against health-care personnel must stop, especially as the world fights COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1743–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31191-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bhatti OA, Rauf H, Aziz N, Martins RS, Khan JA. Violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of incidents from a lower-middle-income country. Ann Glob Health. 2021;87(1):41. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lafta R, Qusay N, Mary M, Burnham G. Violence against doctors in Iraq during the time of COVID-19. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8):e0254401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rodríguez-Bolaños R, Cartujano-Barrera F, Cartujano B, Flores YN, Cupertino AP, Gallegos-Carrillo K. The urgent need to address violence against health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Care. 2020;58(7):663. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Muñoz Del Carpio-Toia A, Begazo Muñoz Del Carpio L, Mayta-Tristan P, Alarcón-Yaquetto DE, Málaga G. Workplace violence against physicians treating COVID-19 patients in Peru: a cross-sectional study. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021 Oct;47(10):637-645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Basis F, Moskovitz K, Tzafrir S. Did the events following the COVID-19 outbreak influence the incidents of violence against hospital staff? Isr J Health Policy Res. 2021;10(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13584-021-00471-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.World Medical Association Condemns Attacks on Health Care Professionals. 2020. Available online at: https://www.wma.net/news-post/world-medicalassociation-condemns-attacks-on-health-care-professionals/. Accessed 7 Jun 2020.

- 79.McKay D, Heisler M, Mishori R, Catton H, Kloiber O. Attacks against health-care personnel must stop, especially as the world fights COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1743–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Alsuliman T, Mouki A, Mohamad O. Prevalence of abuse against frontline health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in low and middle-income countries. East Mediterr Health J. 2021;27(5):441–442. doi: 10.26719/2021.27.5.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shafran-Tikva S, Chinitz D, Stern Z, Feder-Bubis P. Violence against physicians and nurses in a hospital: how does it happen? A mixed-methods study Isr J Health Policy Res. 2017;6(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s13584-017-0183-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.• Kumari A, Kaur T, Ranjan P, Chopra S, Sarkar S, Baitha U. Workplace violence against doctors: characteristics, risk factors, and mitigation strategies J Postgrad Med. 2020 Jul-Sep;66(3):149–154. This is a comprehensive review of workplace violence against doctors, discussing the prevalence, degree of violence, predictors, impact on physical and psychological health, and intervention strategies to devise practical actions against workplace violence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Spelten E, Thomas B, O'Meara PF, Maguire BJ, FitzGerald D, Begg SJ. Organisational interventions for preventing and minimising aggression directed towards healthcare workers by patients and patient advocates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Apr 29;4(4):CD012662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.• Raveel A, Schoenmakers B. Interventions to prevent aggression against doctors: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019 Sep 17;9(9):e028465. This review failed to gather sufficient numerical data to perform a meta-analysis. A large-scale cohort study would add to a better understanding of the effectiveness of interventions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.• Wirth T, Peters C, Nienhaus A, Schablon A. Interventions for workplace violence prevention in emergency departments: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Aug 10;18(16):8459. The paper examines the role of intervention in reducing violence against physicians, and it shows a positive effect in the form of a reduction of violent incidents or an improvement in how prepared staff were to deal with violent situations [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Gordon J. Medical humanities: to cure sometimes, to relieve often, to comfort always. MJA. 2005;182:5–8. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06543.x [PubMed]

- 87.• Kaur A, Ahamed F, Sengupta P, Majhi J, Ghosh T. Pattern of workplace violence against doctors practising modern medicine and the subsequent impact on patient care, in India. PLoS One. 2020 Sep 18;15(9):e0239193. The paper indicates that workplace violence has a significant effect on the psycho-social well-being of doctors, as well as on patient management. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Vento S, Cainelli F, Vallone A. Violence against healthcare workers: a worldwide phenomenon with serious consequences. Front Publ Health. 2020;8:570459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 89.Mittal S, Garg S. Violence against doctors - an overview. J Evolution Med Dent Sci. 2017;6(2948–2751):7. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Morganstein JC, West JC, Ursano RJ. Work-Associated Trauma. In: Brower KJ, Riba MB (Eds) Physician mental health and well-being research and practice. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017. p. 33–60.

- 91.Geoffrion S, Goncalves J, Marchand A, Boyer R, Marchand A, Corbière M, Guay S. Post-traumatic reactions and their predictors among workers who experienced serious violent acts: are there sex differences? Ann Work Expo Health. 2018;62(4):465–474. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxy011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lever I, Dyball D, Greenberg N, Stevelink SAM. Health consequences of bullying in the healthcare workplace: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(12):3195–3209. doi: 10.1111/jan.13986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.• Magnavita N, Di Stasio E, Capitanelli I, Lops EA, Chirico F, Garbarino S. Sleep problems and workplace violence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurosci. 2019 Oct 1;13:997. This review indicates that occupational exposure to physical, verbal, or sexual violence is associated with sleep problems. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Cannavò M, La Torre F, Sestili C, La Torre G, Fioravanti M. Work related violence as a predictor of stress and correlated disorders in emergency department healthcare professionals. Clin Ter. 2019 Mar-Apr;170(2): e110-e123. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 95.• Hacer TY, Ali A. Burnout in physicians who are exposed to workplace violence. J Forensic Leg Med. 2020 Jan;69:101874. Research study showing that doctors who were exposed to violence at work were exposed to verbal and psychological violence more than physical violence and especially psychological violence had a significant negative effect on burnout. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 96.Shi J, Wang S, Zhou P, Shi L, Zhang Y, Bai F, Xue D, Zhang X. The frequency of patient-initiated violence and its psychological impact on physicians in China: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0128394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.•• Linden M, Arnold CP. Embitterment and posttraumatic embitterment disorder (PTED): an old, frequent, and still underrecognized problem Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90(2):73-80. The paper analyzes the history of post-traumatic embitterment disorder as a consequence of traumatic events, including those happening in the workplace. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 98.Linden M, Arnold CP. Embitterment in the Workplace. In: Grassi L, McFarland D, Riba MB, editors. Depression, burnout and suicide in physicians. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 137–146.

- 99.• Lozano JM, Martínez Ramón JP, Morales Rodríguez FM. Doctors and nurses: a systematic review of the risk and protective factors in workplace violence and burnout. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Mar 22;18(6):3280. The review indicates that risk factors for workplace violence in healthcare sector are structural, organizational, and personal (e.g., age, gender) while protective factors are the quality of the working environment, mutual support networks, or coping strategies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.•• Aljohani B, Burkholder J, Tran QK, Chen C, Beisenova K, Pourmand A. Workplace violence in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Publ Health. 2021 Jul;196:186–197. This paper reviews and meta-analyzes ED workplace violence. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 101.• Maguire BJ, O'Meara P, O'Neill BJ, Brightwell R. Violence against emergency medical services personnel: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Ind Med. 2018 Feb;61(2):167–180. This review underlines that emergency unit leaders and personnel should work together with researchers to design, implement, evaluate, and publish intervention studies designed to mitigate risks of violence to EMS personnel. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 102.Udoji MA, Ifeanyi-Pillette IC, Miller TR, Lin DM. Workplace Violence against anesthesiologists: we are not immune to this patient safety threat. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2019;57(3):123–137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Harthi M, Olayan M, Abugad H, Abdel WM. Workplace violence among health-care workers in emergency departments of public hospitals in Dammam. Saudi Arabia East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(12):1473–1481. doi: 10.26719/emhj.20.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Grassi L, Daniel McFarland D, Riba MB. Medical professionalism and physician dignity: are we at risk of losing it? In: Grassi L, Daniel McFarland D, Riba MB, editors. Depression, Burnout and Suicide in Physicians. Berlin: Springer; 2022. p. 11–25.

- 105.Kumari A, Singh A, Ranjan P, Sarkar S, Kaur T, Upadhyay AD, Verma K, Kappagantu V, Mohan A, Baitha U. Development and validation of a questionnaire to evaluate workplace violence in healthcare settings. Cureus. 2021;13(11):e19959. doi: 10.7759/cureus.19959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]