Abstract

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, schools had been adopting digital instruction in many parts of the world. The concept of digital literacies has also been evolving in complexity alongside the digital technologies that support it. However, little is known about what guidance available to support various levels of government in supporting digital literacies alongside digital instruction in local schools. The purpose of this study was to determine what guidance for digital literacies U.S. state departments of education had made available through their websites to local schools just prior to the onset of the pandemic. Using qualitative content analysis techniques, digital literacies guidance information was located on U.S. state departments of education websites and analyzed. Most states did not indicate that they used guidance from professional organizations about digital literacies. The 16 states that did have guidance used standards from the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), which have not been positioned by the organization as digital literacies standards, but instead reflect traditional understandings of Information Computing Technology (ICT). Implications of this study highlight potential strategies educational ministries might use to acknowledge and support digital literacies.

Keywords: Digital literacies, State educational policies, Professional educational organizations, Qualitative policy analysis, Digital learning, Digital education leadership, ISTE standards

Introduction

Digital technologies support meaning making and communication across modes (e.g., linguistic, visual, aural, and semiotic; Álvarez Valencia, 2016). These opportunities for making meaning with new technologies have been conceptualized as types of literacies because they rely on encoding/decoding processes to make meaning in social contexts (Hall, 1973/1991). As technologies have developed to display increasingly complex texts with video, music, animation, and more, digital literacies now encompass a wide and ever-growing variety of strategies, knowledges, and skills. While there is no unanimous agreement about what outcomes for young people are preferable for acquiring digital literacies, proposed goals include: advancing social democracy, maintaining a workforce, and supporting ongoing innovation and quality of life (Coldwell-Neilson, 2017). Each of these goals is a high-stakes one, not just for the learners, but for societies and communities. Therefore, it is important for learners to have opportunities to use digital literacies in their schooling.

Explicit attention to digital literacies as part of digital learning has become more important to formal educational experiences due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic. As school buildings in the United States and across the globe closed, teachers in many countries turned to using digitized instructional materials as part of government directives to provide education (Natanson & Strauss, 2020). While the uses of instructional materials that required digital literacies were expanding even before COVID-19 closed school buildings, the pandemic drew attention to the need to understand efforts to promote digital literacies (Digital Learning Collaborative, 2019). Understanding the digital literacies policies that U.S. states had when the pandemic began can provide important information to the states themselves and to other governing entities when decision makers are ready to revise policies that anticipate long-term school disruptions (Rice & Zancanella, 2021).

This local policy making is critical in the U.S. because the U.S. does not have a national educational policy (U.S. Department of Education, 2021). Instead, individual states develop educational policies in accordance with federal guidance that is usually tied to federal monies. Some policies at the state level are developed in state-level legislatures. Other policies are left to the discretion of state level educational officials hired to make such decisions. Therefore, it is to be expected that states would not be in alignment on any matter of educational policy. However, such differences provide the opportunity to see how different states have addressed important educational challenges so that states or countries with less developed policies can have models and examples in designing policies that work for them. Previous research suggests that many countries experience similar struggles to provide teachers with adequate policy guidance for using technologies generally and digital literacies specifically. For example, Dong and Newman (2018) found that teachers in China were using policy frameworks with inconsistent pedagogical recommendations for teaching digital literacies; Drajati et al., (2018) found that teachers in Indonesia had inconsistent access to common terms and language necessary for professional learning about technologies and information skills; and Luik et al. (2018) found that teachers in Estonia were integrating technologies into teaching without a pedagogical foundation. Considering findings from these studies, it seems useful to understand digital literacies policies and what organizations—with concomitant expertise and values—might be contributing to these.

To guide the leaders at the state level in the U.S., professional organizations with national and international reach have specialized in monitoring research and advocating for practice about digital literacies. Such organizations include the American Association of School Librarians (AASL), Computer Science Teachers of America (CSTA), International Society for Technology Education (ISTE), the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), and more. In addition, there are national consortiums that write standards and make recommendations about curriculum and instruction in the US, such as the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers, which created the Common Core State Standards (2010). There was also a consortium of 26 states that formed the NextGen Science Standards (2013) with support from the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA), the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), and the National Research Council (NRC).

While it might seem to be a positive development that professional organizations and standards for digital literacies were abundant prior to the pandemic, there is no previous research about what guidance existed for digital literacies in different countries or in smaller government levels, such as a U.S. state. This gap extended to a lack of knowledge about how information, standards, and other materials from professional organizations might contribute to policy implementation in schools and classrooms. To address this gap, researchers investigated the following questions:

What professional organizations’ guidance were U.S. states drawing on about digital literacies leading up to the pandemic?

What were the key descriptive features of that guidance?

Defining Digital Literacies

Various professional organizations may use various types of related terms to describe digital literacies. These terms suggest various purposes and values. Also, Digital literacies as a term, is ever-evolving due to its reliance on technologies that are ever expanding (Lankshear & Knobel, 2006). Due to this changeability, policies for digital literacies seem challenging to develop. In research projects, key terms for digital literacies also need to be expansive. Many of the literacies of the digital originated in the pre-digital period but have gained importance because of their links to more sophisticated practices (Bawden, 2008; Martin & Grudziecki, 2006). This has happened in much the same way that early household computers have a relationship with more modern machines. The more modern computers have greater memories and connective capacities and a larger array of options for using and producing text (Bawden, 2001, 2008). While the terminology around using and producing text with digital literacies has undergone considerable development, many of the same concepts that emerged in the 1960s governing technological knowledge and skills are still used today (Dakers, 2006; van Joolingen, 2004, slide 5). For example, machines like typewriters and even older computers still have screens and keyboards. Many of the same keystrokes are required to do the same task in the 1880s through to the 1980s and now in 2021.

Early definitions and terms

There were many attempts to define digital literacies that compare them to information literacies (Gilster, 1997; Eshet, 2002). Specifically, the Prague Declaration (UNESCO, 2003) emphasised the global importance of information literacy in the context of the “Information Society.” The statement used words such as identify, locate, evaluate, organize, create, and use to convey its intentions. Specifically, the UNESCO document predicted a so-called new Information Society and indicated that Information Literacy was a basic human right.

Expansion of terms to Include Media Forms

Evaluating media has a critical bearing on individual health decisions, elections, and more (Potter, 2018). Media literacy studies have come to encompass understandings about how messages are constructed and interpreted, including understanding how characteristics of the author/sender and the receiver are crucial in understanding the meaning of the message and its content (Bawden, 2008; Martin & Grudziecki, 2006). Most recently, this includes social media and gaming (Rhodes & Robnolt, 2009). Part of understanding media requires understanding how images, text, and/or sound are used together to make meanings for various audiences (Blackall, 2005; Cameron, 2000; Mills, 2016). Multimodality also highlights the importance of symbolic systems and social semiotics (Kress & Leeuwen, 2006). Together, these elements of information, media, and mode shape what Lankshear & Knobel (2003) described as New Literacies and they include post typographic forms of texts, such as images, sounds, haptic manipulation, and more. These literacies help users access, interpret, criticise, and participate in culture and society (Kahn & Kellner, 2006; Kellner, 2002; Snyder, 2002; Tyner, 2014).

Recent definitions and expansions of Digital Literacies

More recently Çam & Kiyici (2017) merged elements from multiple time periods and frames, including ICT, information literacy, technological literacy, visual literacy, and media literacy. This definition summarised many of the repeating, overlapping ideas from previous definitions and provided the guidance for this study.

The term “digital literacy” today can be defined as the technical knowledge and skills necessary for the individuals who want to lead a productive life, to continue their personal development with lifelong learning activities, and to contribute positively to society. With this definition, the literacies incorporated in digital literacy can be listed as Information Literacy, Visual Literacy, Software Literacy, Technology Literacy, and Computer Literacy (p. 30).

For literacy researchers, there have been additional expansions on the idea of digital literacies to include more critical evaluation (Alvermann & Sanders, 2019; Digital Literacy High-Level Expert Group, 2008). In addition, Kellner (2002; 2004) expanded the notion of literacies even further to include aspects of social power as a site for production and consumption of digital texts. This layer of criticality requires teachers to focus more on issues of audience and purpose than skills like typing or even coding as aspects of digital literacies. Using Kellner (2003) as a frame for critical digital literacies might be precarious in the current moment as many U.S. states are banning curriculum and instruction that even uses the word critical (Sawchuk, 2021). It is under these shifting definitions and expanding understandings about literacies that states are working to determine the importance of these and make educational policies about them. It is also in this context that digital literacies guidance at the state level, might use multiple terms and take on multiple forms.

Professional Organizations and Advocacy

Professional agencies in education in the U.S. and even globally in some cases have been developing various standards (e.g., ISTE, CTSA, Next Generation Science, NETEA, AASL) for the specific purpose of informing the research and practice. Moreover, organizations rely on entities to take up their standards to demonstrate that their organization is viable, deserving of their members, and worthy of additional members. Besides the practical matter of demonstrating their professional prowess, these professional organizations and the guidance they give should enable conversations about equity when they are taken up by entities such as states.

Professional organizations all over the world engage in developing standards or guidance to set expectations for professional practices as well as provide some managerial oversight (Wadmann et al., 2019). Within the U.S., and for education specifically, these organizations have advanced new standards, guided education policies, and influenced legislative and regulatory practices (Dauenhauer et al. 2019; 2014; McGuinn, 2012).

Within such professional organizations, prominent members, boards, and/or task forces use research and perhaps federal guidance to craft standards and make recommendations for practice. Since the state leadership and the professional organizations might have the same access to members, research, and federal guidance, it stands to reason that most states would come to develop or adopt the similar standards from a narrow range of organizations, rather than each state crafting their own separate standards from multiple sources (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Moreover, states that are close together geographically may also be more likely to rely on the same professional organizations for standards. With these ideas about the relationship between professional organizations and leaders in-state entities, we undertook this policy scan study to explore what guidance for digital literacies U.S. state departments of education were providing to local schools.

Methodology

This policy scan drew on strategies from Ortiz et al. (2020) for obtaining information from state databases. The following policy scan activities were undertaken in 2018 through 2019: (1) open google search processes, (2) targeted searches on the state websites, (3) selection of information for inclusion, (4) content analysis of included items, and (5) verifying analysis for trustworthiness.

Open Google Searches

The first round of searching consisted of open Google searches. One researcher entered the terms “digital literacies [state name]”, “technological literacies [state name],” “information technologies [state name]” and “information computing technologies [state name]” to allow for the widest search possible. From there, the links that were provided were followed to see if the search result was linked to the state office of education or was sponsored by them in any way. Whatever was linked was captured either as a link or downloaded as a document and stored with a file in the state’s name.

Targeted state website searches

The second task was to go directly to the state website and search for guidance about digital/technological literacies. A second researcher engaged in this step. Where possible, searches were entered into search fields on the sites. Another strategy was to follow tabs and hyperlinks to literacy information and determine if there were any resources for digital/technological literacies. Resulting sites and documents were downloaded or captured as a link and then added to a file with the state’s name. When this was done, the two researchers compared and compiled documents.

Selection of information for inclusion

Once the information from the folders had been compiled, it was time to determine which documents constituted guidance. The researchers used the following criteria to determine whether this was the case. First, the document or site needed to be formally prepared for public viewing. This usually indicated formatting, a title, and an explanation of where the document came from. Second, the document or site needed to specify that it was for use in planning instruction. Third, the document or site is needed to name specific student outcomes. These could be formal objectives, or they could be more general aims. Finally, the document needed to contain the phrase “digital literacies” or related terms to separate it from general technological implementation or assistance with technologically supported patterns like blended learning. A table was made with fields for each state. Items were added as they related to the research question. Specifically, researchers recorded content areas, the organizations within the state office of education or under their direction who were sponsoring the development of the document, and what professional organizations’ information was cited in the document.

Content analysis of included items

The results underwent conventional content analysis to determine findings (Hsiu-Fang & Shannon, 2005). Content analysis leads to the “interpretation of content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding or identifying of themes or patterns” (Zhang & Wildemuth, 2009, p. 1278). Using a qualitative design for this content analysis emphasized “concepts rather than simply words” (Fraenkel & Wallen, 2011, p. 389) and also conveyed facts in a manner that was coherent and useful (Sandelowski, 2010). The content analysis for this project was conducted by having two researchers—one researcher from the initial identification and one entirely new researcher—move through the data in the first table to identify patterns. Several emerged. One was the prevalence of the ISTE standards as professional organizations whose work had been cited from the standards. The two researchers then made a new table of the ISTE states documenting whether the topic headings from ISTE were intact, the grade level articulations like those from ISTE had been used, the ISTE standards had been used as a primary framework or there were also other organizations cited, certain subjects or content areas were mentioned, and the definition of digital or technological literacy was included. The table was coded for patterns by the two researchers and then checked for accuracy by the researcher from the first round who participated in the identification of initial documents but did not participate in the initial content analysis.

Verifying analysis for trustworthiness

In qualitative research, trustworthiness reflects an effort to “control for potential biases that might be present throughout the design, implementation, and analysis of the study” (Bloomberg & Volpe, 2012, p176). The study was designed to allow other researchers to track “the processes and procedures used to collect and interpret the data” (p. 163). The account described above should enable other researchers to follow the same procedures and arrive at generally the same conclusions. During this process it was critical to ensure that major steps were taken and completed promptly so that websites would not change or that established issues of consensus among the researchers for inclusion would not be forgotten or shifted.

This process of working steadily also supported us in developing objectivity (Bloomberg & Volpe, 2018). The goal was to ensure that the findings come directly from the research rather than the biases and subjectivity of the researcher to the greatest extent possible. To ensure this, researchers used team processes where two researchers performed the identification task with a separate verification and then a team with one original researcher and a new researcher performed the analysis with a separate verification researcher. Further, one of the researchers was a digital literacies scholar and may have carried notions with them about what guidance should look like but was checked by another researcher who studied other aspects of technology in schools. A third researcher who did not research technology at all also contributed by providing an outsider view of what should constitute guidance about digital literacies (Hammersley, 2012). Thus, the findings presented should present a strong objective interpretation of the information that was discovered.

Findings

The purpose of this study was to learn what professional agencies U.S. states had been drawing on for guidance about digital literacies on their department of education websites. Each state department of education website was searched for guidance, but not every state had a plan. What follows is a description of the guidance that was found.

Overall description of findings

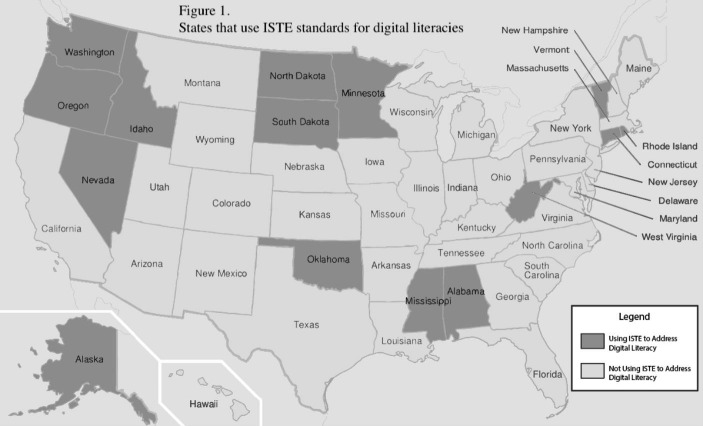

During the search process, the ISTE standards emerged as the most frequent source of professional guidance. Sixteen states used the ISTE standards as their primary source of guidance and support for digital literacies (See Fig. 1). Moreover, 11 states had adopted the standards as they were, with no modifications (Alabama, Alaska, Connecticut, Idaho, Mississippi, Nevada, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin). Nine states adopted the ISTE standards in concert with other professional organizations (Alabama, Minnesota, Mississippi, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Washington, Wisconsin). These organizations will be discussed later. Finally, eight states even included the same grade level articulations as those that ISTE uses (Alabama, Alaska, Idaho, Nevada, South Dakota, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin).

Fig. 1.

States that use ISTE standards for digital literacies

The states that used the ISTE standards placed them in context with a variety of subject matter orientations. Some states used the standards in more than one subject matter orientation: computer science (Alabama, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin); library science (Connecticut, Oregon, Wisconsin); general technology and information science (Idaho, Nevada, Washington, Wisconsin); Other sciences (Washington, Wisconsin); English language arts/general literacy (Mississippi, Washington, Wisconsin); mathematics (Mississippi, Washington, Wisconsin); and social science (Washington).

A few states that featured professional guidance about digital literacies used standards from groups other than ISTE. For example, the state of Washington had a document that incorporated guidance from NSCC, CTSA, and Next Generation Science Standards. Also, Washington referenced the largest number of subject matter specialties, including science, math, and technology, as well as library sciences, social studies, and English language arts. Table 1 contains sample descriptions from various states.

Table 1.

Additional Sample Descriptions of State Plans

| State | Description from Website |

|---|---|

| Alaska | The Alaska Digital Literacy Standards update the 2006 Alaska Technology Standards, bringing them into alignment with contemporary technology opportunities available to districts and students in Alaska. They focus on leveraging technology for learning, expression, digital citizenship, and communication. The standards are based on the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) student standards (2016 edition). |

| Idaho |

The standards align with the draft version of the K-12 Computer Science Framework (2016). The framework reflects the latest research in CS education, including learning progressions, trajectories, and computational thinking. The K-12 Computer Science Framework was steered by five organizations: Association for Computing Machinery, Code.org, Computer Science Teachers’ Association, Cyber Innovation Center, and National Math and Science Initiative; several states (MD, CA, IN, IA, AR, UT, ID, NE, GA, WA, NC), large school districts (NYC, Chicago, San Francisco); technology companies (Microsoft, Google, Apple); and individuals (university faculty, researchers, K-12 teachers, and administrators). |

| North Dakota | The North Dakota State content standards offer instructional guidance in core curriculum areas, while at the same time, they allow for, indeed encourage, a dynamic and living curriculum created at the local school district level. To ensure educational relevance, our state’s content standards are (1) based on academic standards developed nationally by various professional education associations, (2) validated by our state’s best educators based on classroom experience and local community expectations, and (3) widely supported by state and national education policymakers. |

| Oklahoma | The Oklahoma Society for Technology in Education (OKSTE) provides instructional support, innovative leadership, and professional development as learning communities fuse the science of teaching and learning with EdTech. OKSTE is an ISTE affiliate and will use that relationship to create cadres of learning communities that are innovation leaders in the authentic integration of EdTech in Oklahoma classrooms. |

| Rhode Island | The International Society of Technology in Education (ISTE) Standards act as a roadmap for educators and education leaders looking to re-engineer their schools and classrooms for digital age learning. |

| Vermont | The Vermont State Board of Education adopted the International Standards for Technology Education (ISTE) Standards for student learning. The adoption of this framework is aligned with the state’s Education Quality Standards. These standards outline what Vermont students should know and be able to do with respect to information technology and will guide and inform the work of our schools as they prepare students for college and careers that have been dramatically transformed by information technology. |

| Washington | Defines digital and media literacies and makes recommendations for legislative actions that support policies and practices. |

| West Virginia |

The West Virginia Board of Education and the West Virginia Department of Education are pleased to present Policy 2520.14, 21st Century Learning Skills and Technology Tools Content Standards and Objectives for West Virginia Schools. The West Virginia Standards for 21st Century Learning includes 21st century content standards and objectives as well as 21st century standards and objectives for learning skills and technology tools. This broadened scope of curriculum is built on the firm belief that quality engaging instruction must be built on a curriculum that triangulates rigorous 21 st century content, 21 st century learning skills and the use of 21st century technology tools. |

Exploration of several States’ plans

States that incorporated ISTE standards to address digital literacies generally agreed on the importance of preparing students for digital citizenship as a critical aspect of digital literacies. However, states took different paths to the creation of their digital literacy guidance. Two examples come from Alabama, a politically conservative state in the southeastern U.S. and Connecticut, a politically progressive state in the northeastern part of the U.S. Alabama spends less money per pupil than most states and has a lower graduation rate than many other states. Connecticut spends more money per pupil than most states and has a higher graduation rate and students score higher on college entrance tests than in most other states. These differences provide an opportunity for comparison and contrast of their plans.

Alabama

The Alabama public school system (prekindergarten through grade 12) operates within smaller districts governed by locally elected school boards and superintendents (Ballotpedia, 2021a). The state has about 750,000 students enrolled in roughly 1,700 schools in 173 school districts (Ballotpedia, 2021a). The state has about 52,000 teachers in their schools (Ballotpedia, 2021a). On average Alabama spends close to $9,000 per pupil and ranked it 39th highest in the nation in spending (Ballotpedia, 2021a). The state’s graduation rate hovers around 80%.

In terms of digital access, about 88.6% of all Alabamians have access to high-speed internet, defined as internet with download speeds of 25 megabits per second or faster (Smith, 2020). There are about 475,000 people in Alabama without access to high-speed internet, including large swathes of rural Alabama (Smith, 2020). In fact, nine of Alabama’s 67 counties have less than 30% access to broadband, all of which are counties where many Black families live, some of which have poverty rates of greater than 30% (Smith, 2020). In addition, the US census bureau estimates only 73.3% of households subscribed to broadband internet between 2014 and 2018, suggesting that even when households have access to broadband, they may not be able to afford it (Smith, 2020). The governor of Alabama allocated 100 million dollars of federal disaster relief money to broadband access and schools partnered with local business to provide free Wi-Fi to schools for remote instruction. Given these circumstances, many K-12 students in the state of Alabama need access to the internet alongside access to digital literacies. Also, K-12 students in the state seem to need stronger educational support overall.

Alabama created a task force that was charged with conceptualizing and creating a Course of study for digital literacies and computer science (Richardson, n.d). The task force in Alabama that created their pre-pandemic digital literacies policy document consisted of stakeholders that represented multiple areas of the state of Alabama’s educational system. The task force included members from local Boards of Education, faculty members from local universities, school technology specialists, and one representative from industry. The industries represented were technological in nature, such as a company that sold email sorting software.

The Alabama document focused drew on the ISTE standards, saying:

The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) Standards for Students emphasize the skills and qualities we want to foster in students, enabling them to engage and thrive in a connected, digital world (Richardson, n.d., p.1).

This does not say anything explicit about literacy, but rather that the skills and the ethos of the standards are the reason for their inclusion in the development of the course of study. For defining digital literacies, the group members generated the following definition:

Digitally literate students can use technology responsibly and appropriately to create, collaborate, think critically, and apply algorithmic processes. They can access and evaluate information to gain lifelong knowledge and skills in all subject areas. Alabama includes computational literacy in its definition of digital literacy. Our goal is digital and computational literacy for all Alabama students (Richardson, n.d., p. 1).

Their definition includes many of the goals advanced for digital literacies, including advancing social democracy through the goal to “collaborate” and “use technology responsibly” (Mora, 2016), maintaining a workforce through the emphasis on “computational literacy” (Pothier & Condon, 2019), and supporting ongoing innovation and quality of life through “lifelong knowledge and skills” (Coldwell-Nelson, 2017). In this course of study, the team who created the document hybridized many ideas about digital literacies and digital learning to create a guidance document for their state.

Connecticut

The Connecticut public school system (prekindergarten through grade 12) was operating within districts governed by locally elected school boards and superintendents (Ballotpedia, 2021b). Connecticut has about 560,000 students enrolled in a total of 1,200 schools in 200 school districts (Ballotpedia, 2021b). There were about 44,000 teachers in the public schools (Ballotpedia, 2021b). On average Connecticut spends about $17,000 per pupil per year, which ranked it fifth highest in the nation in spending (Ballotpedia, 2021b). The state’s graduation rate is about 86% (Ballotpedia, 2021b).

During the pandemic, Connecticut spent 60 million dollars in federal monies and private donations to ensure that all students had an internet-ready device for school. Prior to the pandemic, about half of Connecticut’s student population lacked an internet connection and/or an internet-ready device in their home (Thomas & Watson, 2020). Many of these families without access were people of color, particularly Black and Hispanic/Latinx families (Thomas & Watson, 2020). Even so, thousands of school children were left without a broadband connection when remote schooling resumed in the fall (Thomas & Watson, 2020). These facts illustrate that even in states that spent more money on education and generally had better outcomes, there were large disparities when it comes to access to the internet, devices, and thus, digital literacies.

In Connecticut the department of education created a document called Charting New Frontiers in Student-Centered Learning (Casey et al., 2017). To create the document, there were multiple councils assembled into one large advisory committee. These councils included topics of data and privacy, digital learning, and infrastructure. Individuals who participated in these councils were representatives from public schools—mostly at the administrative level, higher education, library directors, law firms, data security officers from universities, and technology vendors. The town manager of Coventry, Connecticut also participated as a community member. Overall, there was far less participation from school representatives, but more from other groups.

In terms of digital literacies, the plan offered no direct definition, but the document expressed the intention for libraries to be sites of digital literacies:

Connecticut’s libraries offer digital and media literacy, cybersecurity, and other technology training to students of all ages, helping to bring about a more literate citizenry that can better understand and support the power of technology to deepen and personalize learning (Casey et al., 2017, p. 47).

The document includes references to media, data privacy, as well as ICT skills through “training” to students. The goals for democratic participation are also evident (Coldwell-Nelson, 2017). What is different about this document from Alabama, other than the greater emphasis on digital skills over digital literacies. In Alabama, the definition offered had a more community-centered approach and a stronger articulation of lifelong benefits to the students. Also, the Connecticut document does not mention ISTE at all, but instead includes several state-based technology commissions and the national organization Innovation Partners of America.

Together, these two examples demonstrated how states were offering very different documents—some with very narrow definitions in terms of content, and some with more open definitions going into the pandemic. Importantly, these extant policies were the baseline or starting point for what states had been providing to schools before massive remote learning set in. The comparison also highlights the various ways that digital literacies might be included in guidance documents to varying degrees while still expressing similar values for students to understand technologies and engage with them in ways that benefit them and possibility their communities.

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to investigate the integration of professional guidance about digital literacies into U.S. state education policies. Researchers wanted to know whose guidance states were relying on and how the states had incorporated that guidance within the subject matter and grade levels. Limitations to this study included the fact that states may post, update, move, or remove information at their will so not all information located during the search period may be located now, but available data can be provided to others upon request. With keyword searches, there is always a chance that additional keywording would have yielded additional information. Our purpose of learning about guidance for digital literacies focused on connecting information to literacy pages on state department of education websites, but it is possible that state technology education officials have taken up digital literacies without posting information online as evidence. Also, state officials change periodically or shift responsibilities, making it difficult to identify persons who might have information or who may be posting it.

While it is not a limitation, but rather an issue of scope, we remind readers that we did not gather data about how those policies might have changed during the pandemic. We might anticipate that not very much policy making directly about digital literacy occurred, however, since it would seem more likely that states were scrambling just to get remote online learning set up so that some instruction could be given. What is clear from an analysis of the data is that states took a variety of approaches that in future work can be examined by policy makers to see if there is need of revision.

Finally, it is important to remember that ISTE standards are used by many states, but that the purpose of this research was to find guidance for digital literacies. Not every state that used ISTE standards placed the standards alongside notions of digital literaciesand not every state that used ISTE standards as digital literacies has made strong connections between the standards and digital literacies.

What Professional Organisations’ Guidance do U.S. States draw on about Digital Literacies?

Although 16 states used the ISTE standards somewhere in their digital literacy guidance and a handful used standards from other places, over half of the states did not mention any organization’s guidance in connection with digital literacies. This could mean that states were not prioritizing digital literacies or any of its related concepts (information literacies, technological literacies). It could also mean that states did not know where to go for guidance. Afterall, Lankshear and Knobel (2006) pointed out that defining and understanding digital literacies outside of academic spaces is an imprecise endeavor. Indeed, in the two case study states, many families of color and families in rural areas were without internet access and devices, which might take priority for digital literacies away from officials in favor of other needs, including basic needs for connections and devices. However, when states encountered difficulties moving to digital learning, some of those challenges might come from an apparent lack of clarity about what are digital literacies and what constitutes digital knowledge and skills (Cameron, 2000; Mills, 2016). Reciprocally, one needs digital literacies to advocate for and leverage access to the internet and devices, but one also needs an internet connection and a device to use and develop digital literacies.

For states that had guidance, many chose the ISTE standards. This was an interesting choice because the ISTE standards do not explicitly claim to be literacy standards. In an explanation of the recent revision of the standards, Trust (2018), who was one a member of the revision team, noted that the standards were focused on helping teachers in using technology to “support student learning and creative thinking, design digital age activities and assessments, model digital work, promote and model digital citizenship, and engage in professional growth and leadership” (p. 1). Notice the similarity of these standards to many of van Joolingen’s (2004) definition of ICT literacies as:

the interest, attitude, and ability of individuals to appropriately use digital technology and communication tools to access, manage, integrate and evaluate information, construct new knowledge, and communicate with others to participate effectively in society (slide 5).

Reading the information from Trust (2018) and van Joolingen (2004) together, it is evident that ISTE standards touch on many of the same priorities as ICT literacies although ISTE has never claimed to be a literacy organization or claimed the ISTE standards are about literacies. Such circumstances again, raise the issue as to whether there is a meaningful distinction at this point in technological development between digital literacies and the knowledge, skills, and dispositions to engage in digital learning generally (Cameron, 2000; Mills, 2016). There may not be a meaningful distinction for state-level officials who design, approve, and promote this guidance. Other countries striving to support digital learning might also overlook digital literacies as a distinct need or embed it within general learning without reflection.

Further, while there was a wide variety of guidance taken up by states who were using guidance, there were some notable organizations that were not represented. One such example was the National Council of Teachers of English, which has a committee called Digital Literacies in Teacher Education (D-LITE). The D-LITE group has published several iterations of Beliefs about Integrating Technology into the English Language Arts Classroom (Lynch et al., 2018). Other countries might also have organizations that have guidance that has not been accessed by government leaders and could prove helpful.

Another challenge in the U.S. and abroad might be the participation of educational technology vendors in policy making without proper transparency. Such participation was more of an issue in Connecticut where there are many headquarters for educational technology companies versus Alabama, which prioritized wide participation from local school experts. Leaders in the U.S. and other countries might consider who is participating in these policy discussions, what their motives might be, and what can be done, not necessarily to discourage or eliminate vendor participation, but to declare it and understand its limitations the same as any other group. For example, many other countries struggle with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that sometimes come into countries and promise support for underserved groups; however, people from those countries do not always trust that they are not just seeking government money from poor countries as a source of profit (Author, 2019).

In summary, the fact that the states that do have plans mostly drew their guidance from the same organization, even though that was not explicitly a literacy organization, supports the theory that many U.S. state leaders have converged on similar policies to ease the burden of trying to generate totally separate guidance within their states (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). While there was only one state that had executive representation from ISTE on their board (Nevada), many of the planning board members may be members of ISTE and their familiarity with ISTE many have led them to think that adopting the standards was time and money saving. Again, the researchers of this study find nothing wrong with the ISTE standards—they merely question whether their wide use as literacy standards occurred because there was no real distinction between digital literacies and digital learning skills in policy makers’ minds, or these leaders were unable to reflect on the differences due to time, cost, or other pressures. This is also an important question in the U.S. and internationally when research studies use terms like ICT and e-learning as catch-all phrases for any learning that uses digital elements. As research, policy, and practice communities, we should be asking what the value is in having and using certain terms with precision, or if the terms should be left to local decision makers.

What are the key descriptive features of the Guidance documents?

As for question 2 about how professional guidance has been integrated, the answer is that in cases where the standards are used, they are used in their entirety. Moreover, the grade level distinctions recommended by ISTE were often included. Only a few states, such as Minnesota, Washington, and Alabama, had developed comprehensive digital literacies guidance that drew on multiple sources and had been customized to the needs of the states. Regardless of the unique needs that probably exist in every state, the common needs are the ones that are in the best position to be met because they enable complete adoption of standards that already exist and again, carry the perception of saved time and money (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). While it is beyond the scope of this research to say how and whether local schools used the guidance, it is interesting to consider how participation in the creation of the plans might shape later use of them in the places that matter: classrooms. This also seems important in the international arena where there may be differing levels of federal oversight of education.

Implications

Now that the pandemic has changed education and offered insight into the best and worst of digital education experiences for school children and their teachers, there is a need to make stronger plans for digital learning during times of disruption and beyond (Rice & Zancanella 2021). Along these lines, the current study has several important implications for practice, research, and policy.

Practice

High quality digital literacy learning is not an accident and does not seem to be coercible in the moment of crisis (Rice & Zancanella, 2021). Therefore, educational agencies need to study guidance from professional organizations in their respective countries about digital literacies use to craft sound policies and practices. We also feel that these conversations can include all digital learning, but that some explicit conversation about digital literacies is important, given the interrelationship between digital literacies and digital learning. It is our contention that digital literacies is more than just ICT knowledge repackaged from the 1960 and 1970s (Martin & Grudziecki, 2006). In a true frame of digital literacies, practices that are oriented around analysis and evaluation of digital texts and tools, alongside awareness of audience and purpose for what is composed in digital spaces are most important (Alvermann & Sanders, 2019; Kellner, 2002; 2004; Mills, 2016).

Finally, U.S. state agencies and policy making agencies in other countries should consider how to make this guidance appropriate for the schools in their stewardship (U.S. Department of Education, 2021). There seems to be strong opportunities to make plans that draw on local strengths and expertise, such as was done in Alabama, since there has been so little federal guidance about digital literacies in the U.S. and so many national organizations with advice seem to stand at the ready. For countries without a wealth of professional organizations, leaders might consider looking to a geographic neighbor with shared history and values as a starting point. For example, Canada developed a nationwide overview of the digital literacy strengths and needs across their provinces and outlined steps that might be taken to develop policies at the level of provinces. (Hoechsmann & DeWaard 2015). Their work might be useful for countries like the U.S. that share some aspects of political organization, history, and geographic proximity. In turn, Canadian officials might consider what professional organizations in their country or internationally might have additional insight for policies that leverage the strengths for their various provinces.

Research

Future research projects should look at how states with various types of guidance from various agencies fared during the transition to emergency remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic (Education Week, 2020). This research might be done in countries outside the U.S. with whatever guidance these political units were using. Besides achievement data, perception work might be useful in finding out whether educators within the state at various levels know about the guidance or use it. Moreover, some individual school districts and agencies might have their plans that draw on various sources of guidance. It seems worth investigating how these plans are formed and how professional organizations’ guidance makes its way (or does not) into the plans. In other countries, similar work might determine what educators in classrooms know about the policies for digital literacies (if there be any) in their jurisdictions. It might also be helpful to look at what aspects of guidance are most important to set a foundation for digital literacies development and digital learning in schools. For example, findings from a study in Ireland suggest that broadband access might be a critical foundational step for establishing engagement for digital learning generally (Mac Domhnaill et al., 2021).

Future research about professional learning about digital literacies provided by U.S. states or other agencies and local school entities internationally might shed additional light on how professional guidance makes it to teachers and into their practice. For example, it seems important to understand how teachers understand guidance about digital and technology education in cases where digital literacies and its accompanying ideologies about power construction and community practices are included and when they are not (Kellner, 2002; 2004). This is especially important considering that many U.S. states and many countries were scrambling to acquire internet connections and devices for students when the COVID-19 pandemic shut down many school buildings (Mac Domhnaill et al., 2021; Smith, 2020; Thomas & Watson, 2020). Who receives devices and access and why they have it are part of the critical digital literacies that students need (Kellner, 2002; 2004).

Policy

While ISTE redesigned its Standards for Educators regarding how to use technology to learn, collaborate, lead, and empower students based on input solicited from more than 2,000 educators and administrators, generally, the relationship between standards and academic research remains unclear (Trust, 2018). While practice to policy to research is certainly a possible pathway to understanding, there are alternative pathways that begin with collaborative research with practitioners and then move to policy before recommending procedures for practice.

While there were U.S. states that used ISTE standards that did not expressly connect the standards with digital literacies, several of them did. In terms of policies, ISTE might consider how many state-level agencies have adopted their standards into their digital literacies guidance. What should ISTE do with this information? They might be more explicit about how their standards promote digital literacies. They might also distance themselves from literacies and focus more on their work as a general technological organization. Other political units and entities might also consider reviewing the guidance they give to ensure that digital literacies are specifically addressed according to how it is conceptualized and applied in local settings. The questions remain: Is there a meaningful distinction between digital literacies and digital learning in the minds of practitioners and policy makers? Should there be?

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to understand what professional agencies were providing the guidance that U.S. states were adding to their state department of education websites as part of their support for local schools. By locating and analyzing the various plans, the ISTE standards for technology learning were the most popular, but most states offer no guidance at all. However, the states that have adopted the ISTE standards, did seem to follow the isomorphic pattern of geographical clustering (Fig. 1). These findings suggest that leaders in various regions should consider including guidance that is focused on literacies directly, even when they have guidance about learning generally (Alvermann & Sanders, 2019; Kellner, 2002; 2004). With the COVID-19 pandemic’s disruption of schooling and the continuation of the trend toward the digital instructional materials, now is the time for states to make strategic decisions about how to include digital literacies in their formal guidance.

Data Availability

Some data may be available upon request.

Declarations

Conflicting Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mary F. Rice, Email: maryrice@unm.edu

Mark Bailon, Email: mbailon@unm.edu.

References

- Álvarez Valencia JA. Meaning making and communication in the multimodal age: ideas for language teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal. 2016;18(1):98–115. doi: 10.14483/calj.v18n1.8403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvermann, D. E., & Sanders, R. K. (2019). Adolescent literacy in a digital world. In R. Hobbs, & P. Mihailidis (Eds.), The International Encyclopedia of media literacy (pp. 1–6). John Wiley & Sons.

- Ballotpedia (2021a). Public education in Alabama. Retrieved from https://ballotpedia.org/Public_education_in_Alabama

- Ballotpedia (2021b). Public education in Connecticut. https://ballotpedia.org/Public_education_in_Connecticut

- Bawden, D. (2008). Origins and concepts of digital literacy. In C. Lankshear, & M. Knobel (Eds.), Digital literacies: concepts, policies and practices (pp. 17–32). Peter Lang.

- Blackall L. Digital literacy: how it affects teaching practices and networked learning futures-a proposal for action research in. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning. 2005;2(10):14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Çam, E., & Kiyici, M. (2017). Perceptions of prospective teachers on digital literacy.

- Malaysian OnlineJournal of Educational Technology, 5(4),29–44.

- Cameron, D. (2000). Book review: Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. By Bill Cope, Mary Kalantzis (eds.) (2000). Routledge. Changing English, 7(2), 203–207.

- Casey, D., Duty, L., & Kisiel, R. (2017). Chartering new frontiers in student-centered learning. Connecticut Association of School Superintendents.

- Dakers, J. (Ed.). (2006). Defining technological literacy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Digital Learning Collaborative (2019). Snapshot 2019: A review of K-12 online, blended, and digital learning. Retrieved from https://www.evergreenedgroup.com/keeping-pace-reports

- Digital Literacy High-Level Expert Group (2008). Digital literacy European commission working paper and recommendations from Digital literacy high-level expert group. Brussels, Belgium. Retrieved from http://www.ifap.ru/library/book386.pdf

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields.American Sociological Review,147–160.

- Dong C, Newman L. Enacting pedagogy in ICT-enabled classrooms: conversations with teachers in Shanghai. Technology Pedagogy and Education. 2018;27(4):499–511. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2018.1517660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drajati, N. A., Tan, L., Haryati, S., Rochsantiningsih, D., & Zainnuri, H. (2018). Investigating English language teachers in developing TPACK and multimodal literacy.Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics,575–582.

- Education, & Week (2020). Map: Coronavirus and school closureshttps://www.edweek.org/ew/section/multimedia/map-coronavirus-and-school-closures.html

- Eshet, Y. (2002). Digital literacy: A new terminology framework and its application to the design of meaningful technology-based learning environments. In P. Barker & S. Rebelsky (Eds.) Proceedings of EDMEDIA, 2002 World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia, & Telecommunication (pp. 493–498). AACE.

- Fraenkel, J. R., & Wallen, N. E. (2011). How to design and evaluate research in education. McGraw-Hill.

- Gilster, P. (1997). Digital literacy. Wiley. Hall, S (1991 [1973]) Encoding, decoding. In S. During (ed.) The Cultural Studies Reader, (pp. 90–103). Routledge.

- Hammersley, M. (2012). What is qualitative research?. A&C Black.

- Hsiu-Fang, H., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Qualitative health research. Three Appro.

- Kahn, R., & Kellner, D. (2006). Reconstructing technoliteracy. Defining technological literacy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kellner, D. (2002). Multiple literacies and critical pedagogies: new paradigms. In P. P. Trifonas (Ed.), Revolutionary pedagogies (pp. 218–244). Routledge.

- Kellner D. Technological transformation, multiple literacies, and the re-visioning of education. E-learning and Digital Media. 2004;1(1):9–37. doi: 10.2304/elea.2004.1.1.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G. R., & Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: the grammar of visual design (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2003). New literacies: changing knowledge and classroom learning. Open University Press.

- Lankshear C, Knobel M. Digital literacy and digital literacies: policy, pedagogy and research considerations for education. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy. 2006;1:12–24. doi: 10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2006-01-03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luik P, Taimalu M, Suviste R. Perceptions of technological, pedagogical and content knowledge (TPACK) among pre-service teachers in Estonia. Education and Information Technologies. 2018;23(2):741–755. doi: 10.1007/s10639-017-9633-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, T., Hicks, T., Bartels, J., Beach, R., Connors, S., Damico, N., Doerr, Stevens, C., Hicks, T., LaBonte, K., Loomis, S., McGrail, E., Moran, C., Pasternak, D., Piotrowski, A., Rice, M., Rish, R., Rodesiler, L., Rybakova, K., Sullivan, S., Sulzer, M., Thompson, S., Young, C., & Zucker, L. (2018). Beliefs for integrating technology into the English Language Arts classroom Retrieved from http://www2.ncte.org/statement/beliefs-technology-preparation-english-teachers/

- Martin A, Grudziecki J. DigEuLit: concepts and tools for digital literacy development. Innovation in Teaching and Learning in Information and Computer Sciences. 2006;5(4):249–267. doi: 10.11120/ital.2006.05040249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Domhnaill C, Mohan G, McCoy S. Home broadband and student engagement during COVID-19 emergency remote teaching. Distance Education. 2021;42(4):465–493. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2021.1986372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinn P. Fight club: are advocacy organizations changing the politics of education. Education Next. 2012;12(3):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin VL, West JE, Anderson JA. Engaging effectively in the policy-making process. Teacher Education and Special Education. 2016;39(2):134–149. doi: 10.1177/0888406416637902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills, K. A. (2016). Literacy theories for the digital age: Social, critical, multimodal, spatial, material and sensory lenses. Multilingual Matters.

- Mora RA. Translating literacy as global policy and advocacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 2016;59(6):647–651. doi: 10.1002/jaal.515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Natanson, H., & Strauss, V. (2020). America is about to start online learning, round 2: For millions of students, it won’t be any better. Washington Post (August 20, 2020). Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/america-is-about-to-start-online-learning-round-2-for-millions-of-students-it-wont-be-any-better/2020/08/05/20aaabea-d1ae-11ea-8c55-61e7fa5e82ab_story.html

- National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common Core State Standards. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers.

- Next Generation Science Standards (2013). Retrieved from https://www.nextgenscience.org/

- Ortiz K, Mellard D, Rice MF, Deschaine ME, Lancaster S. Providing special education services in fully online statewide virtual schools: a policy scan. Journal of Special Education Leadership. 2020;33(1):3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pothier, W. G., & Condon, P. B. (2019). Towards data literacy competencies: Business students, workforce needs, and the role of the librarian.Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship,1–24.

- Potter, W. J. (2018). Media literacy. Sage. Rhodes, J.A., & Robnolt, V.J. (2009). Digital literacies in the classroom. In L. Christenbury, R. Bomer, & P. Smagorinsky (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent literacy research (pp. 153–169). Guilford.

- Rice M, Zancanella D. Framing policies and procedures to include digital literacies for online learning during and beyond crises. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. 2021;65(2):183–188. doi: 10.1002/JAAL.1194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, E. (n.d.). Alabama course of study: Digital literacy and computer science. Alabama Department of Education.

- Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health. 2010;33(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawchuk, S. (2021). What is critical race theory? and Why is it under attack? Education Week (May 18, 2021). https://www.edweek.org/leadership/what-is-critical-race-theory-and-why-is-it-under-attack/2021/05

- Smith, M. (2020). No child left offline: Tackling the digital divide in Alabama. A + Education Partnership. Retrieved from https://aplusala.org/blog/2020/08/17/no-child-left-offline-tackling-the-digital-divide-in-alabama/

- Snyder, I. (Ed.). (2002). Silicon literacies: communication, innovation and education in the electronic age. Psychology Press.

- Thomas, J. R., & Watson, A. (2020). Almost all K-12 students in CT now have internet access. What’s the plan for seniors and others without school-aged families? CT Mirror. Retrieved from https://ctmirror.org/2020/10/27/almost-all-k-12-students-in-ct-now-have-internet-access-whats-the-plan-for-seniors-and-others-without-school-aged-families/

- Trust T. 2017 ISTE Standards for educators: from teaching with technology to using technology to empower learners. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education. 2018;34(1):1–3. doi: 10.1080/21532974.2017.1398980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO (2003). Conference report of the information literacy meeting of experts. Prague, September 20–23, 2003. Retrieved from http://www.nclis.gov/libinter/infolitconf&meet/post-infolitconf&meet/FinalReportPrague.pdf

- United States Department of Education (2021). The federal role in educationhttps://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/fed/role.html

- van Joolingen, W. (2004). The PISA framework for assessment of ICT literacy Retrieved from http://www.ericlondaits.com.ar/oei_ibertic/sites/default/files/biblioteca/7_pisa_framework.pdf

- Wadmann S, Holm-Petersen C, Levay C. ‘We don’t like the rules and still we keep seeking new ones’: the vicious circle of quality control in professional organizations. Journal of Professions and Organization. 2019;6(1):17–32. doi: 10.1093/jpo/joy017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., & Wildemuth, B. M. (2009). Unstructured interviews. Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science. University of Texas Press.

- Dauenhauer B, Keating X, Stoepker P, Knipe R. State physical education policy changes from 2001 to 2016. J SchHealth. 2019; 89: 485-493. DOI: 10.1111/josh.12757 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bloomberg, L. D., & Volpe, M. (2018). Completing your qualitative dissertation: A road map from beginning to end. Sage.

- Tyner, K. (2014). Literacy in a digital world: Teaching and learning in the age of information. Routledge.

- Sandelowski Margarete. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health. 2010;33(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell-Neilson, J. (2017). Digital literacy–a driver for curriculum transformation. Research and development in higher education: Curriculum Transformation, 40, 84-94.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some data may be available upon request.