Abstract

University students are a high-risk population with problematic online behaviours that include generalized problematic Internet/smartphone use and specific problematic Internet uses (for example, social media or gaming). The study of their predictive factors is needed in order to develop preventative strategies. This systematic review aims to understand the current state of play by examining the terminology, assessment instruments, prevalence, and predictive factors associated with problematic smartphone use and specific problematic Internet uses in university students. A literature review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines using four major databases. A total of 117 studies were included, divided into four groups according to the domain of problem behaviour: problematic smartphone use (n = 67), problematic social media use (n = 39), Internet gaming disorder (n = 9), and problematic online pornography use (n = 2). Variability was found in terminology, assessment tools, and prevalence rates in the four groups. Ten predictors of problematic smartphone use, five predictors of problematic social media use, and one predictor of problematic online gaming were identified. Negative affectivity is found to be a common predictor for all three groups, while social media use, psychological well-being, and Fear of Missing Out are common to problematic smartphone and social media use. Our findings reaffirm the need to reach consistent diagnostic criteria in cyber addictions and allow us to make progress in the investigation of their predictive factors, thus allowing formulation of preventive strategies.

Keywords: Problematic smartphone use, Problematic social media use, Internet gaming disorder, Predictors, Psychological variables, College students

Introduction

In recent years, the global percentage of Internet users has grown exponentially and smartphone has become the main device in its access (We Are Social and Hootsuite, 2022). The expansion of Internet access has changed the way people live, work, communicate, and learn and has become an essential environment in their development (Pinho et al., 2021). In the education sector, incorporation of the use of Internet services has led to multiple improvements in the teaching–learning process (Wu et al., 2010), and specifically at universities, has allowed eliminating geographical barriers and increasing flexibility (Santhanam et al., 2008; Yakubu et al., 2020).

However, university students do not only use the Internet for educational and academic purposes, but also to look for information, random navigation, entertainment, communication, gaming, social networks, and online shopping and, to a lesser extent, gambling and obtaining sexual information (Adorjan et al., 2021; Anand et al., 2018; Balhara et al., 2019; Maqableh et al., 2021; Servidio, 2014; Zenebe et al., 2021). These coincide with the purposes of smartphone use by this population (Coban & Gundogmus, 2019; Matar Boumosleh & Jaalouk, 2017).

The widespread availability of the Internet through smartphones and other devices is associated with multiple benefits, such as access to information and a space for social communication and entertainment. (e.g., Maia et al., 2020; Manago et al., 2012). However, Internet penetration in everyday life is a serious problem for an increasing number of people, rising to the level of problematic Internet use (PIU) or problematic smartphone use (PSU). These problematic behaviours are associated with negative consequences such as poor academic performance (Anderson et al., 2017; Grant et al., 2019), psychological distress (Busch & McCarthy, 2021; Chen et al., 2020; Odacı & Çikrikci, 2017; Radeef & Faisal, 2018; Weinstein et al., 2015), and disturbed sleep and daytime sleepiness (Ferreira et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2020a), to name a few.

Problematic Internet and smartphone use

Although there was already concern about addictive use of the internet by the end of the last century (Griffiths, 1995; Young, 1998a), today, there is currently greater recognition of technological addictions in mental health by both the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2013) and the World Health Organization (WHO, 2018), and excessive use of digital technologies has been recognised as a public health issue (WHO, 2015).

Today, several terms are often used to describe the phenomenon, such as addiction (Young, 1998a) or internet dependency (Dowling & Quirk, 2009). Among these, the term “problematic Internet use” (hereinafter, PIU) stands out, and it is defined as a pattern of maladaptive Internet use characterised by loss of control, the appearance of negative consequences, and obsessive thoughts when the Internet cannot be accessed (D'Hondt et al., 2015). This is an umbrella term (Fineberg et al., 2018) and accommodates the broad spectrum of non-adaptive behaviours online, which go beyond behavioural addiction (Billieux et al., 2015b; Starcevic, 2013). However, the terms "Internet addiction" and PIU are used inconsistently in the literature (Sánchez-Fernández et al., 2022).

Smartphone, because it is portable and gives easy access to internet, has the potential to create high dependency and is a powerful risk factor for problematic and addictive behaviours (Aljomaa et al., 2016; Carbonell et al., 2018). As a result, problematic smartphone use (PSU) is now being discussed more and more, such as excessive smartphone use that interferes with various areas of a person's life (Billieux et al., 2015a).

The current debate is whether PSU can be considered a sub-category of PIU or whether it is an independent phenomenon (Cheever et al., 2018). Recent studies have found that PIU and PSU overlap in some, but not all key features (Lee et al., 2020; Tateno et al., 2019), while others have established that these problematic behaviours all overlap (Kittinger et al., 2012; Montag et al., 2015).

Recent epidemiological studies have found a large variability in the prevalence rates of PIU and PSU in the general population (López-Fernández & Kuss, 2020; Sohn et al., 2019). In the case of university students, variability has also been found in the prevalence rates of PIU (4—51%), which may be explained by the lack of diagnostic criteria and cultural differences between samples (Sánchez-Fernández et al., 2022). However, despite this variability, these problems increase over time (López-Fernández & Kuss, 2020; Kuss et al., 2021; Pan et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2018) and university students tend to be at higher risk of PIU (Anderson et al., 2017; Ferrante & Venuleo, 2021; Kuss et al., 2014) and PSU (Roig-Vila et al., 2020).

Specific problematic Internet uses

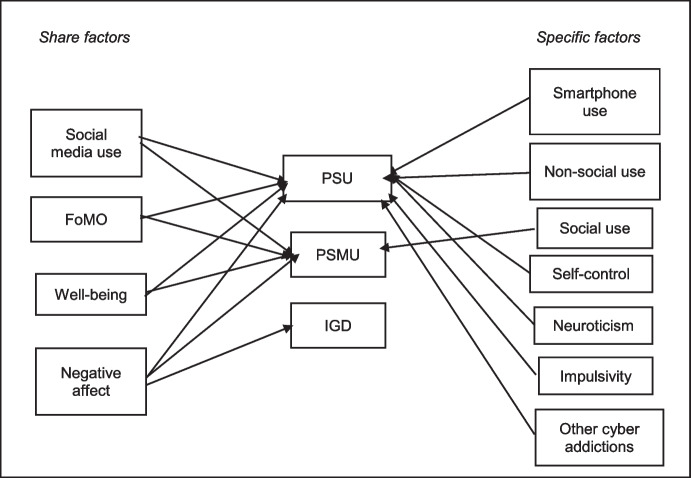

PIU/PSU is a broad term that may include a variety of problematic behaviours. In fact, individuals who use the Internet/smartphone excessively do not become addicted to the Internet/smartphone environment but to the behaviours they engage in when they are online (Király & Demetrovics, 2021; Meerkerk et al., 2009). That is why some authors are sceptical about the viability of PIU/PSU as a construct, and favour the examination of specific activities such as playing games or sexual activity (e.g., Starcevic & Aboujaoude, 2017). At the beginning of the century, Davis (2001) made a distinction between two different forms of pathological use of the Internet: general and specific. The general one includes a broader set of behaviours while the specific one refers to engagement with specific Internet functions or applications. Years later, Billieux (2012) argued for the existence of a spectrum of cyber addictions that would include problematic behaviours related to the smartphone, in general, and specific online activities such as video games and online gambling, pornography, and social networks. More recently, some authors have conceptualised problem behaviours mediated by the Internet and smartphones as being within a spectrum of related conditions associated with both shared and unique characteristics (Baggio et al., 2018). In this study, "specific problematic Internet uses" will refer to those problematic online behaviours that can be carried out via smartphone or any other device.

Previous reviews (Kuss et al., 2021; Lopez-Fernandez & Kuss, 2020) have established four main themes in terms of specific PIU: problematic social media use (PSMU), Internet gaming disorder (IGD), problematic Internet pornography use (PIPU), and problematic Internet gambling. These studies show great variability in terms of terminology (addiction coexisting with problematic use, disorder, or dependence, among others), as well as in measurement instruments and prevalence rates. So far, no systematised data focusing on the university student population have been found.

Conceptualisation of problematic Internet use behaviours

A number of diverse etiological models have been proposed in the conceptualisation of these problem behaviours (Ferrante & Venuleo, 2021). Davis (2001), in his cognitive behavioural model of pathological Internet use, proposes that psychopathology (distal cause) would give rise to the PIU, generalized or specific, through maladaptive cognitions (proximal cause such as low self-efficacy or negative self-evaluation). The behavioural symptoms of PIU are reinforcements of the maladaptive cognitions that result in a vicious circle and maintain pathological behaviour.

On the other hand, the person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model (Brand et al., 2016, 2019) argues that specific problematic uses of the Internet are the consequence of interactions between predisposing (personality-related characteristics, social cognitions, biopsychological factors and motivation to use), moderating (coping styles and Internet-related cognitive biases) and mediating (affective and cognitive responses to situational triggers) factors in combination with reduced executive functioning. These associations would be maintained by Pavlovian and instrumental conditioning processes within an addiction process. The authors also assume that the medium (internet, smartphone) is secondary in the origin of these problem behaviours and that, among the psychological and neurobiological mechanisms, some are common and others specific to each addictive behaviour (such as specific personality profiles) (Brand et al., 2016, 2019).

Risk and protective factors for problematic internet usage behaviours

Research on shared risk and protective factors unique to the spectrum of online problem behaviours is essential for advancing their conceptualisation and prevention, which in turn will have clear implications for the overall health and well-being of university students (Tugtekin et al., 2020). Problem behaviours mediated by the Internet and smartphones are associated with both shared and unique risk factors (Baggio et al., 2018; Billieux, 2012).

Previous reviews have examined risk factors for PIU, finding that being younger, being male, a higher family socio-economic status, duration of use, social networking and gaming, neuroticism, impulsivity, loneliness, depression, anxiety and general psychopathology increase the risk of generalized PIU (Aznar Díaz et al., 2020; Kuss et al, 2014, 2021); depression and aggression were the main risk factors for online gaming addiction, Internet gambling problems were associated with lower emotional intelligence and psychological distress, and problematic online pornography use was most frequently related to relationship problems, disruptive worry and behavioural dysregulation (Kuss et al., 2021). On the other hand, with regard to PSU, the review by Wacks and Weinstein (2021) concludes that it is associated with psychiatric, cognitive, emotional, medical and brain alterations. For their part, Busch and McCarthy's (2021) review of the predisposing factors to PSU found a great variety of backgrounds divided into four categories: Control (e.g. self-control or tolerance of uncertainty), Emotional health (e.g. anxiety and depression), Physical health (e.g. Individual's health status), Preconditions (e.g. family characteristics), Professional performance (e.g. academic performance), Social performance (e.g. personality) and Technology features (e.g. type of mobile phone use).

However, no consistent findings have been found in research on predictors of generalized and specific PIU and PSU in the university student population.

Prior to this study, the authors reviewed studies on risk and protective factors for generalized PIU in university students. Ten predictive factors for PIU have been identified and divided into three categories (patterns of use, psychological variables, and lifestyles). Among these, nine were risk factors (time spent online, video games, depression, negative affect, life stress, maladaptive cognitions, impulsivity, poor sleep quality, substance use (alcohol and drugs), and one was a protective factor (conscientiousness). However, all studies that focus on other technologies-related problem behaviours, such as PSU or specific PIU, were excluded from this review.

The purpose of the study

Consequently, the aim of this systematic review is to examine the studies of predictors of PSU and specific PIU (online gaming, social networking, online gambling, and online pornography) in university students that have been published since the inclusion of IGD in the DSM-5.

The research questions are: 1. What terminology is used to refer to PSU and specific PIU?, 2. What are the assessment tools used in the PSU and specific PIU evaluation?, 3. What is the prevalence of PSU and specific PIU?, 4. What are the risk and protective factors associated with PSU and specific PIU? From these questions, the objectives are as follows: 1. To become familiar with the terminology used, 2. To review the assessment tools, 3. To analyse prevalence and 4. To study the risk and protective factors associated with PSU and specific PIU.

Methodology

Systematic review methodology was used (Page et al., 2021). We included scientific research articles published between 2013, the year when "Internet gaming disorder" (IGD) in DSM-5 (APA, 2013) was officially recognised, and the expansion of smartphone use (Carbonell et al., 2018), and 2021, both years included, on predictive, risk and protective factors associated with PSU and specific problematic internet use (e.g., social networking) in university students. The Web of Science, Proquest (PsycINFO and Medline) and Scopus databases were used between October and December 2021. The keyword strategy used the terms, clusters, and Boolean operators listed in Table 1 (also translated into Spanish, French, and Italian). The search was done by article title, abstract and keywords.

Table 1.

Search strategy

| Identifier 1 | Identifier 2 | Identifier 3 | Identifier 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

(Problem* OR dependen* OR excess* OR compuls* OR addict* OR patholog* OR disorder) |

(Internet OR smartphone OR “mobile phone” OR “cell* phone” OR “video gam*” OR “online gam*” OR “social network*” OR "social media" OR “online pornography”) |

(factor* OR variabl* OR caus* OR antecedent* OR predictor*) | (undergraduate* OR "university student*" OR "college student*") |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (1) scientific articles; (2) study factors predicting PSU or specific PIU through predictive modelling; (3) university students from more than one area of knowledge; (4) 17 years or older; (5) use of validated instrument; (6) quantitative empirical data; (7) reported effect size; (8) access to full text; and (9) written in English, Spanish, French and Italian.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) studying predictors of PIU or other behavioural addictions that do not involve Internet use (e.g. offline gambling) or substance-related addictions (e.g. alcoholism); (2) lack of relevant data; (3) non-university sample; (4) under 17 years of age; (5) university students from a single field of knowledge; (6) sample collected during the covid-19 lockdown; (7) no predictive statistical model; (8) no use of validated instruments; (9) validation studies of assessment instruments; (10) unreported effect size; and (12) sources other than peer-reviewed journals (e.g. non-peer-reviewed journals, conference abstracts, chapters, books, corrections).

Selection of articles

The PRISMA protocol guidelines were followed (Page et al., 2021) (See Fig. 1). Our initial sample contained 117 articles. They were included in the present review after screening duplicates and articles that met the inclusion criteria mentioned, but not the exclusion criteria. The included studies were organized into four main subjects, one of them referring to a generalized problematic use of smartphones: Problematic Smartphone Use (PSU) and three on specific problematic uses of the internet: Problematic Social Media Use (PSMU), Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) and Problematic Internet Pornographic Use (PIPU). Since they analysed more than one variable, some studies have been repeated in two subject groups.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Diagram of study selection processes

At a second stage, articles whose predictive factors were supported by at least 3 studies were chosen, in order to address Objective 4. As a result of this second analysis, 83 articles were selected that studied 10 PSU factors, 5 PSMU factors, and 1 IGD factor.

Data extraction

The characteristics of the 117 studies selected are shown in Table 2. In terms of effect size, betas (ß), odds ratio (OR) and coefficient of determination (R2) were included. For betas, the cut-off points are used: Very small > 0 to < 0.1, small ≥ 0.1 to < 0.3, medium ≥ 0.3 to < 0.5 and large ≥ 0.5 (Cohen, 2013, Ferguson, 2016). For odds ratios (OR): Very small > 0 to < 1.5, small ≥ 1.5 to < 2, medium ≥ 2 to < 3, and large ≥ 3 (Sullivan & Feinn, 2012). With respect to the coefficient of determination (R2): Very small < 0.02, small ≥ 0.02, medium ≥ 0.13 and large ≥ 0.26 (Dominguez-Lara, 2017).

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of selected articles in alphabetical order (N = 117)

| Author, year of publication | Country | Sample size (proportion of female) | Age sample (years: range, M (SD)) | Variable | Assessment toola (prevalence: M (SD)/% (cut-off point)) | Predictive factors | Stadistical modelb (number of predictors), Measure of association | Direction and effect sizec | QAd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problematic smartphone use (PSU) | ||||||||||

| Prospective cohort studies | ||||||||||

| 1 | Cui et al., 2021 | China | 1181 (51%) | 18 – 21, 18.91 (0.85) | Problematic mobile phone use | MPATS (37.08 (13.62)) |

(I) T1 PMPU (II) T1 Bedtime procrastination (III) T1 Depressive symptoms |

CL (adjusting gender and age, bedtime procrastination, sleep quality and depressive symptoms) (I) 0.423** (II) 0.092** (III) 0.151** |

(I) M ( +) (II) VS ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 2 | Elhai et al., 2018b | USA | 261 (76.9%) | 19.73 (0.52) | Problematic smartphone use | SAS-SV (26.31 (10.35)) |

(I) Distress tolerance (II) Midfulness (III) Smartphone use frequency |

SEM (Sex, age, depression, anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, mindfulness, smartphone use frecuency) (I) − 0.20* (II) − 0.39*** (III) 0.14* |

(I) S (-) (II) M (-) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (7, 14) |

| 3 | Rozgonjuk et al., 2018 | Estonia | 366 (79%) | 19 – 55, 25.75 (7.70) | Problematic smartphone use | E-SAPS18 (33.58 (12.12)) |

(I) Social media use in lectures (II) Age |

SEM (Trait procrastanation, Social Media Use in Lectures, Age, Gender) (I) 0.345*** (II) -0.411*** |

(I) M ( +) (II) M (-) |

Fair (2, 7, 14) |

| 4 | Yuan et al., 2021 | China | 341 (75.7%) | 21.24 (2.72) | Problematic Smartphone Use | SAS-SV (35.23 (10.58)) |

(I) Gender (being female) (II) Depression symptoms (III) FoMO (IV) IGD (IGD) |

SEM (Age, gender, fear of missing out, IGD, depression) (I) 0.19*** (II) 0.15** (III) 0.18*** (IV) 0.26*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) |

Fair (3, 13, 14) |

| 5 | Zhang et al., 2021 | China | 352 (55%) | 17 – 23, 19.30 (1.16) | Mobile Phone addiction | MPATS (2.60 (0.60)) |

(I) Boredom proneness W1 (II) Mobile phone addiction W1 |

CL (boredom proneness (W1, W2), mobile phone addiction (W1)) (I) 0.10* (II) 0.69*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) L ( +) |

Good (14) |

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||||||

| 6 | Abbasi et al., 2021 | Malaysia | 250 (58%) | 80% 18–32 | Smartphone addiction | SAS-SV (NR) |

(I) Entertainment (II) Social networking sites (SNS) use (III) Game-related use |

SEM (smartphone content i.e. study, entertainment, SNS, and game-related usage) (I) 0.146** (II) 0.128* (III) 0.427*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) M ( +) |

Fair (2, 3, 14) |

| 7 | Alavi et al., 2020 | China | 1400 (68%) | 18 – 35, 25.17 (4.5) | Smartphone addiction | CPDQ (NR) |

(I) Sex [female VS Male] (II) Marital Status [Single VS Married] (III) Bipolar disorder (IV) Depression (V) Anxiety (VI) Somatization (VII) Dependent personality disorder (VIII) Compulsive personality disorder |

MLogR (Sex, Age, Marital status, avoidant personality disorder, PTSD, Cychlotymia, Panic Disorder, OCD, Anorexia, Bulimia, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, somatization, dependent personality disorder, and compulsive personality disorder) (I) 1.2* 1.7–2.8 (II) 1.5* 1.9–2.5 (III) 4.2* 1.27–14.1 (IV) 4.2* 4.6–39.2 (V) 1.2* 3.8–6.4 (VI) 2.8* 6.8–11.9 (VII) 3.1* 1.38–6.92 (VIII) 3.2* 1.4–6.7 |

(I) VS ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) L ( +) (IV) L ( +) (V) VS ( +) (VI) M ( +) (VII) L ( +) (VIII) L ( +) |

Fair (2, 3) |

| 8 | Alosaimi et al., 2016 | Saudi Arabia | 2367 (56%) | 50% 20–24 | Problematic use of mobile phones | PUMPS (60.8) |

(I) Consequences of the use of smartphones (II) Number of hours spent per day using smartphones (III) Year of study (IV) Number of applications used |

MR (consequences of smartphone use (negative lifestyle, poor academic achievement), number of hours per day spent using smartphones, years of study, and number of applications used) (I) 0.564*** (II) 0.225*** (III) 0.086*** (IV) 0.046** |

(I) L ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) VS ( +) (IV) VS ( +) |

Fair (3, 14) |

| 9 | Arpaci & Kocadag Unver, 2020 | Turkey | 320 (66%) | 20.36 (2.35) | Smartphone addiction | SPAI (NR) |

Women: (I) Neuroticism (II) Agreeableness (III) Conscientiousness Men: (I) Agreeableness |

SEM (gender differences in the relationship between “Big Five personality traits” and smartphone addiction) Women: (I) 0.18* (II) − 0.18* (III) − 0.16* Men: (I) − 0.33* |

Women: (I) S ( +) (II) S (-) (III) S (-) Men: (I) M (-) |

Fair (2, 3, 14) |

| 10 | Bian & Leung, 2014 | China | 414 (62%) | 60.1% 23 – 26 | Smartphone addiction | MPPUS (48.48 (12.75)) |

(I) Grade (II) Shyness (III) Loneliness (IV) Information seeking (V) Utility (IV) Fun seeking |

R (Age, Gender, Grade, Family monthly income, Psychological attributes, Shyness, Loneliness, Smartphone usage (Information seeking, Utility, Fun seeking, Sociability)) (I) –0.12* (II) 0.20*** (III) 0.21*** (IV) 0.16*** (V) 0.13** (IV) 0.17*** |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) (V) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) |

Good |

| 11 | Canale et al., 2021 | Italy | 795 (69.8%) | 18 – 35, 23.80 (3.02) |

Problematic Mobile Phone Use: Addictive mobile phone use; Antisocial mobile phone use; Dangerous mobile phone use |

PMPUQ – SV (Addictive mobile phone use: 12.88 (3.03); Antisocial mobile phone use: 9.78 (2.35); Dangerous mobile phone use: 7.94 (2.95))) |

Addictive mobile phone use: (I) negative urgency (II) behavioural inhibition (III) primary psychopathy (IV) social anxiety Antisocial mobile phone use: (I) lack of premeditation (II) sensation seeking (III) aggressive traits (IV) primary psychopathy Dangerous mobile phone use: (I) lack of premeditation (II) sensation seeking (III) primary psychopathy |

BA (Social anxiety, Neuroticism, Self-esteem, Psychological distress, Behavioural inhibition, Negative urgency, Positive urgency, Lack of premeditation, Aggression, Primary psychopathy, Secondary psychopathy, Sensation seeking, Extraversion, Reward responsiveness, Drive, Fun seeking) Addictive mobile phone use: (I) 0.22* (II) 0.11* (III) 0.06* (IV) 0.02* Antisocial mobile phone use: (I) 0.17* (II) 0.08* (III) 0.02* (IV) 0.07* Dangerous mobile phone use: (I) 0.30* (II) 0.11* (III) 0.11* |

Addictive mobile phone use: (I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) VS ( +) (IV) VS ( +) Antisocial mobile phone use: (I) S ( +) (II) VS ( +) (III) VS ( +) (IV) VS ( +) Dangerous mobile phone use: (I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 12 | Cebi et al., 2019 | Turkey | 571 (70.2%) | 18—22, 19.03 (1.32) | Problematic mobile phone use | PMPUS (59.87 (16.92)) |

(I) Experiential self-control (II) Reformative self-control |

PM (Experiential Self-Control, Reformative SelfControl) (I) -0.375* (II) -0.142* |

(I) M (-) (II) S (-) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 13 | Choi et al., 2015 | Korea | 463 (60%) | 20.89 (3.09) | Smartphone addiction | SAS (68.46 (24.95)) |

(I) Internet Addiction (II) Alcohol Use Disorders (III) State–Trait Anxiety Inventory scores (IV) Gender (being female) (V) Depression (VI) Character Strengths Test–temperance scores |

MR (Gender, Internet Adiction Test, State–Trait Anxiety Inventory, Trait Version, Character Strengths Test) (I) 0.184*** (II) 0.251*** (III) 0.224*** (IV) 0.293*** (V) − 0.215*** (VI) − 0.143** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) (V) S (-) (VI) S (-) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 14 | Coban & Gundogmus, 2019 | Turkey | 1465 (58.8%) | 18—65 (21.10 (1.99)) | Smartphone addiction | SAS-SV (46.9%, ≥ 31 M, ≥ 33 F) |

(I) using the smartphone for “social media use” (II) using the smartphone for “meeting new friends (III) “Use for studying/academic purpose” (IV) “use to follow the news” |

LogR (Social media use, Use for studying/academic purpose, Use for playing games, To meet new friends, Use for communication, For entertainment (watching series, movies, clips), To follow the news, For shopping) (I) OR 2.884, 95% CI 2.085 3.099 (II) OR 2.066, 95% CI 1.535 2.783 (III) OR 0.589, 95% CI 0.434 0.797 (IV) OR 0.645, 95% CI 0.485 0.857 |

(I) M ( +) (II) M ( +) (III) VS (-) (IV) VS (-) |

Fair (3, 14) |

| 15 | Enez Darcin et al., 2016 | Turkey | 367 (62%) | 19.5 (1.15) | Smartphone addiction | SAS (87.6 (26.45)) | (I) Brief Social Phobia Scale |

MR (UCLA Loneliness Scale (UCLA-LS), and Brief Social Phobia Scale (BSPS)) (I) 0.303*** |

(I) M ( +) | Fair (2, 14) |

| 16 | De Pasquale et al., 2019 | Italy | 400 (61%) | 20 – 24, 21.59 (1.43) | Problematic Smartphone Use | SAS-SV ( 41.35 (35.95)) | (I) Emotional stability |

R (Emotional Stability, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Openness to Experience) (I) -0.22** |

(I) S (-) | Fair (2, 14) |

| 17 | Elhai et al., 2018c | USA | 298 (76.8%) | 19.45 (2.17) | Problematic smartphone use | SAS (93.47 (25.30)) |

(I) boredom proneness (II) sex (III) smartphone use frequency |

SEM (depression, anxiety, boredom proneness, age, gender, smartphone use frecuency) Direct effects: (I) 0.44*** (II) 0.26*** (III) 0.31** |

(I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) M ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 18 | Elhai et al., 2018a | USA | 296 (76.7%) | 19.44 (2.16) | Problematic smartphone use | SAS (93.53 (25.38)) |

(I) FOMO (II) Negative Affectivity |

SEM (FoMO, negative affectivity (depression, anxiety, stress, proneness to boredom, and rumination)) (I) 0.33* (II) 0.32* |

(I) M ( +) (II) M ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 19 | Elhai et al., 2020b | China | 1034 (65.3%) | 19.34 (1.61) | Problematic smartphone use | SAS-SV (34.92 (11.39)) |

(I) Age (II) Sex (III) FOMO (IV) Smartphone Use Frequency |

SEM (age, sex, FOMO, Smartphone Use Frequency (SUF), depression, anxiety) Direct effects: (I) 0.12*** (II) 0.39*** (III) 0.61*** (IV) 0.22** |

(I) S ( +) (II) M ( +) (III) L ( +) (IV) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 20 | Elhai et al., 2020a | USA | 316 (66.8%) | 19.21 (1.74) | Problematic smartphone use | SAS-SV (27.41 (9.41)) |

(I) FOMO (II) Non-social use (process use) |

SEM (Sex, FOMO, social use, process use, depression, anxiety) (I) 0.59*** (II) 0.18* |

(I) L ( +) (II) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 21 | Elhai et al., 2020c | China | 1097 (81.9%) | 19.38 (1.18) | Problematic smartphone use | SAS-SV (37.36 (9.54)) |

(I) FOMO (II) Sex (female) (III) Anxiety (IV) Depression (V) Age (VI) Rumination |

Ridge, lasso and elastic net algorithms (FOMO, sex, age, depression, anxiety, rumination) (I) 0.23 0.33 0.24 (II) 0.12 0.11 0.11 (III) 0.11 0.11 0.11 (IV) 0.07 0.03 0.06 (V) 0.06 0.03. 0.05 (VI) 0.05 0.01 0.04 |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) VS ( +) (V) VS ( +) (VI) VS ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 22 | Erdem & Uzun, 2020 | Turkey | 485 (35.3%) | 17–19 years (n = 326, 67.22%) and 20–22 years (n = 149, 30.72%) | Smartphone addiction | TSAS (78.93 (23.21)) |

(I) Age (II) 3–6 h smartphone use versus < 3 h smartphone use (III) > 6 h smartphone use versus 3–6 h smartphone use (IV) 3–6 h Internet use versus < 3 h Internet use (V) > 6 h Internet use versus 3–6 h Internet use (VI) Agreeableness (VII) Conscientiousness (VIII) Neuroticism |

HMR (Age, gender, amount of daily average smartphone and Internet use, the big five personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience)) (I) − 0.11** (II) 0.23*** (III) 0.14* (IV) 0.12* (V) 0.28*** (VI) -0.15*** (VII) − 0.08* (VIII) 0.15*** |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) (V) S ( +) (VI) S (-) (VII) S (-) (VIII) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 23 | Forster et al., 2021 | USA | 1027 (21.68%) | Over 88% 18 -29 | Problematic smartphone use | SAS-SV (24.32%; ≥ 32) |

Household dysfunction: (I) Students who reported 1–3 household stressors, (II) Students who had ≥ 4 household stressors (III) Age |

LogR (Age, sex, race/ethnicity, financial hardship due to COVID-19, depression, social support from friends, Household Dysfunction (HHD)) (I) AOR 1.40, 95% CI 1.02–1.93 (II) AOR 2.03, 95% CI 1.21–3.40 (III) AOR 0.96, 95% CI 0.93–0.99 |

(I) VS ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) VS ( +) |

Good |

| 24 | Giordano et al., 2019 | Italy | 627 (45%) | 18 – 36, 22.77 (3.28) | Problematic smartphone use | SPAI (37.07 (10.60)) |

Females: (I) Selfie-related behavior Males: (I) Selfie-related behavior |

SEM (Age, Selfie-related behaviors and narcissism) Females: (I) 0.315* Males: (I) 0.299* |

Females: (I) M ( +) Males: (I) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 25 | Gökçearslan et al., 2016 | Turkey | 598 (71%) | 80% 18–21 20% + 22 | Smartphone addiction | SAS-SV (20.96 (7.56)) |

(I) Smartphone usage (II) Self-regulation (III) Cyberloafing |

SEM (Smartphone usage, Self-regulation, Cyberloafing, General self-efficacy) (I) 0.54*** (II) − 0.22*** (III) 0.14*** |

(I) L ( +) (II) S (-) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 26 | Gündoğmuş et al., 2021 | Turkey | 935 (54.4%) | 18 – 45, 21.89 (3.27) | Smartphone addiction | SAS-SV (48.6%, ≥ 31 M, ≥ 33 F) |

(I) gender (II) number of social media (III) Alexithymia |

LogR (age, gender, place of residence, monthly income, number of social media and Alexithymia) (I) OR = 1.496, 95% CI 1.117–2.002, p = 0.007 (II) OR = 1.221, 95% CI 1.134–1.315, p < 0.001 (III) OR = 1.074, 95% CI 1.059–1.090, p < 0.001 |

(I) VS ( +) (II) VS ( +) (III) VS ( +) |

Good |

| 27 | Handa & Ahuja, 2020 | India | 240 (45.4%) | 18—25 (88,3% 22–25) | Smartphone addiction | 18 items adapted from Zhitomirsky-Geffet and Blau (2016) (2.98 (0.58)) | (I) FOMO |

SEM (FOMO, loneliness) (I) 0.393*** |

(I) M ( +) | Fair (2, 14) |

| 28 | He et al., 2020 | China | 668 (55%) | 20.05 (1.38) | Excessive smartphone use | SAS-C (2.884 (0.566)) |

(I) Upward social comparison on SNSs (II) Perceived stress |

Mediation analysis (Perceived stress, Upward social comparison) (I) 0.184*** (II) 0.182** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 29 | Hong et al., 2021 | China | 206 (53.4%) | 18—22 | Smartphone addiction | Scale modified from the scale of smartphoneaddiction by Hong, Chiu, and Huang (2012) (Range: 11–59, Average: 33.82 (10.23)) |

(I) Daily time spent on phone calls and texting (II) Relationship with peers (III) Online descriptive social norms (IV) Remote descriptive social norms (V) Co-present descriptive social norms |

PM (Interpersonal relationships (‘Relationship with peers’, ‘Parent–child relationship’, ‘Relationship with remote callers’, and ‘Relationships with cyber friends’), social norm (‘Co-present descriptive social norms’, ‘Co-present injunctive social norms’, ‘Remote descriptive social norms’, ‘Remote injunctive social norms’, ‘Online descriptive social norms’, and ‘Online injunctive social norms’) and smartphone use patterns (daily use time, daily time spent on smartphone-based social media, daily time spent on smartphone-based information search, and daily time spent on smartphone-based entertainment)) (I) 0.14* (II) 0.16* (III) 0.15* (IV) 0.17* (V) − 0.19** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) (V) S (-) |

Good (14) |

| 30 | Hou et al., 2021 | China | 723 (71.9%) | 17 – 25, 19.96 (1.39) | Problematic Smartphone Use | MPAI (2.7 (0.71)) | (I) Anxiety symptoms |

SEM (Anxiety symptoms, Perceived social support) (I) 0.34*** |

(I) M ( +) | Fair (2, 14) |

| 31 | Jiang & Zhao, 2016 | China | 468 (55%) | 18 – 24, 20.71 (1.47) | Problematic mobile phone use | PMPUS (Male: 39.43 ± 10.17; Female: 43.08 ± 9.66) |

(I) Gender (being female) (II) Self-control Use patterns: (III) interpersonal (IV) transaction |

SEM (Gender, self-control and mobile phone use patterns (Interpersonal, Entertainment, Transaction) (I) 0.13 ** (II) − 0.37 *** Use patterns: (III) 0.15 ** (IV) 0.14** |

(I) S ( +) (II) M (-) Use patterns: (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 32 | Jiang & Zhao, 2017 | China | 468 (55%) | 20.71 (1.47) | Problematic mobile phone use | PMPUS (Males: 39.43 ± 10.17, Females: 43.08 ± 9.66) |

(I) Behavioral inhibition system (BIS) (II) Gender (being female) |

HR (gender, time since acquisition, BAS, BIS and self-control) (I) -0.68*** (II) 0.11* |

(I) L (-) (II) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 33 | Jiang & Shi, 2016 | China | 630 (51%) | 18 – 24, 20.63 (1.52) | Problematic mobile phone use | PMPUS (8.99%) |

(I) Self-control (II) Self-esteem (III) Self-efficacy |

LogR (Self-control, Self-esteem, Self-efficacy) (I) OR .899, 95% CI .869–.930 (II) OR 1.007, 95% CI .920–1.101 (III) OR 1.021, 95% CI .927–1.124 |

(I) VS (-) (II) VS ( +) (III) VS ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 34 | Khoury et al., 2019 | Brazil | 415 (54.5%) | 18 – 35, 23.6 (3.4) | Smartphone Addiction | SPAI (43.85%, ≥ 7) |

(I) Facebook addiction (II) Anxiety disorders (III) Female gender (IV) Substance use disorders (V) Age between 18–25 years old (VI) Impulsivity (VII) Low satisfaction with social support |

MR (Facebook addiction, Anxiety disorders, Female gender, Substance use disorders, Age, Impulsivity, Low satisfaction with social support) (I) OR 4.44, 95% CI 2.14–9.21 < 0.001 (II) OR 4.12, 95% CI 2.10–8.91 < 0.001 (III) OR 2.48, 95% CI 1.49–4.14 0.001 (IV) OR 2.48, 95% CI 1.29–4.77 0.007 (V) OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01–1.19 0.021 (VI) OR 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.08 < 0.001 (VII) OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.99 0.016 |

(I) L ( +) (II) L ( +) (III) M ( +) (IV) M ( +) (V) VS ( +) (VI) VS ( +) (VII) VS ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 35 | Kim et al., 2017 | Korea | 200 (63%) | 19 – 28, 21.6 (2.0) | Smartphone addiction | SAPS |

(I) Attachment avoidance (II) depression |

SEM (Attachment anxiety, Attachment avoidance, Depression, Loneliness) (I) − 0.37* (II) 0.34** |

(I) M (-) (II) M ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 36 | Kim & Koh, 2018 | Korea | 313 (58.1%) | 22 (3.4) | Smartphone addiction | SAPS (33.45 (7.67)) |

(I) Self-esteem (II) Anxiety |

SEM (Anxiety, self-esteem, avoidant attachment) (I) -0.19* (II) 0.18* |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 37 | Kim et al., 2019 | Korea | 608 (70%) | 22.8 | Smartphone addiction | SAPS (36% (40–43), 30.2% (≥ 44)) |

(I) stress (II) depression/anxiety symptom (III) suicidal ideation |

LogR (Psychological health: stress, depression/anxiety symptom, suicidal ideation) (I) OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.55–3.10 *** (II) OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.27–2.86** (III) OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.52–3.31*** |

(I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) M ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 38 | Koç & Turan, 2021 | Turkey | 734 (61,4%) | 19 – 25 | Smartphone addiction | SDQ (2468 (0.777)) |

(I) SNS intensity (II) Self-esteem |

SEM (SNS Intensity, self-esteem, subjective well being) (I) 0.643* (II) − 0.106* |

(I) L ( +) (II) S (-) |

Good (14) |

| 39 | Kuang-Tsan & Fu-Yuan, 2017 | Taiwan | 238 (55%) | 18 – 22 | Smart mobile phone addiction | MPAS (2.05) |

(I) Gender (being female) (II) Academic stress (III) Love-affair stress |

MR (Gender, Grade level, Academic stress, Stress of interpersonal relationship, Love-affair stress, Stress of self-career, Family life stress) (I) 0.119* (II) 0.145* (III) 0.371*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) M ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 40 | Kuru & Celenk, 2021 | Turkey | 412 (63.6%) | 18 – 35, 20.71 (2.52) | Smarphone addiction | SPAS-SV (29.50 (11.34)) |

Model 1: (I) Psychological inflexibility (II) Total effect anxiety (III) Direct effect anxiety Model 2: (I) Psychological inflexibility (II) Total effect depression |

Mediation analyses (Model 1: Anxiety, psychological inflexibility; model 2: depression, psychological inflexibility) Model 1: (I) 0.183* (II) 0.168* (III) 0.133** Model 2: (I) 0.183* (II) 0.165* |

Model 1: (I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) Model 2: (I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 41 | Laurence et al., 2020 | Brazil | 257 (72.8%) | 22.4 (3.8) | Problematic smartphone use | Brazilian version of the smartphone addiction scale (SAS-BR) (98.00 (26.73)) |

(I) Loneliness Smartphone social app importance: (II) whatsapp importance (III) Instagram importance Smartphone model (IV) Others (Iphone, not samsung) |

HMLR (Age, Sex, Family monthly income (BRL), smartphone social apps importance (Facebook, Whasapp, Instagram), loneliness, and smartphone model (samsung, others)) (I) 0.31*** Smartphone social app importance: (II) 0.26*** (III) 0.19** Smartphone model (IV) − 0.17** |

(I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) Smartphone model (IV) S (-) |

Good |

| 42 | Lian & You, 2017 | China | 682 (44.6%) | 18 – 24, 19.34 (1.26) | Smarphone addiction | MPAI (2.89 (0.66), 52,9% (scored highest 27%)) |

(I) Conscientiousness (II) Relationship virtues (III) Vitality virtues |

MR (Age, gender, conscientiousness, relationship virtue, vitality virtue) (I) − 0.20*** (II) 0.10* (III) 0.11* |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 43 | Lian, 2018 | China | 706 (46.8%) | 18 – 24, 19.62 (1.21) | Smarphone addiction | MPAI (2.64 (0.67)) |

(I) Conscientiousness (II) Interpersonal |

MR (Virtues (Interpersonal, Vitality, Conscientiousness)) (I) − 0.22*** SEM (two virtues (Conscientiousness, interpersonal), alienation) (II) -0.23** |

(I) S (-) (II) S (-) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 44 | Lin et al., 2021 | China | 863 (59%) | 17 – 23, 20.93 | Smarphone addiction | SAS-C (2.85 (0.55) |

(I) Time (II) Grade (III) Interpersonal sensitivity (IV) FoMO |

Moderated mediation effect analysis (Control variables: gender, time, grade, major, if the one-child, parenting style, growth environment; Independent variable: interpersonal sensitivity; Mediator: FoMO) (I) 0.30* (II) 0.05* (III) 0.35** (IV) 0.24** |

(I) M ( +) (II) VS ( +) (III) M ( +) (IV) S ( +) |

Good (2) |

| 45 | Lin & Chiang, 2017 | Singapore | 438 (53%) | 22.29 (1.63) | Smartphone dependency | MPAI (NR) |

(I) Gender (being female) Psychological attributes: (II) leisure boredom Smartphone activities: (III) mobile social media, (IV) mobile gaming, (V) mobile videos, (VI) traditional phone use |

SEM (Leisure boredom, Sensation seeking, The use of mobile social media, The use of mobile gaming, The use of mobile videos, The use of traditional phone activities) (I) -0.203*** Psychological attributes: (II) 0.238*** Smartphone activities: (III) 0.091*, (IV) 0.142**, (V) 0.170***, (VI) 0.091* |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) (III) VS ( +) (IV) S ( +) (V) S ( +) (VI) VS ( +) |

Fair (3, 14) |

| 46 | Liu et al., 2020 | China | 1169 (43.8%) | 17 – 23, 19.89 (1.25) | Smarphone addiction | MPAI (2.69 (0.70)) |

(I) Neuroticism (II) Childhood psychological maltreatment (III) Negative coping style |

SEM (neuroticism, negative coping style, childhood psychological maltreatment) (I) 0.19*** (II) 0.16*** (III) 0.40*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) M ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 47 | Liu et al., 2021 | China | 908 (52%) | 17 – 27, 21.04 (1.84) | Mobile Phone Dependence | PMPUQ and MPAI (2.72 (0.83)) |

Mediation analysis: (I) Attachment anxiety (II) Loneliness Moderated mediation analysis: (I) Attachment anxiety (II) Loneliness (III) Rumination |

Mediation analysis (Gender, Age, Attachment anxiety, Loneliness) (I) 0.16*** (II) 0.33*** Moderated mediation analysis (Gender, Age, Attachment anxiety, Loneliness, Rumination, Attachment Anxiety × Rumination, Loneliness × Rumination) (I) 0.16*** (II) 0.20*** (III) 0.18*** |

Mediation analysis: (I) S ( +) (II) M ( +) Moderated mediation analysis (I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 48 | Long et al., 2016 | China | 1062 (54%) | 17 – 26, 20.65 (1.54) | Problematic smartphone use | PCPUQ (21.3%, ≥ 4 of the first 7 questions and any of the last 5 questions) |

(I) science-humanities division (majoring in the humanities) (II) monthly income from the family (high monthly income from the family (≥ 1500 RMB)) (III) emotional symptoms (IV) perceived stress (V) perfectionism-related factors (high doubts about actions) (VI) perfectionism-related factors (high parental expectations) |

LogR (Gender, grade, science-humanities division, monthly income from the family, and all psychological risk factors (SAS Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, SDS Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale, PSS Perceived Stress Scale, CFMPS-DA Chinese Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale-Doubts about Actions subscale, CFMPS-PE CFMPS-Parental Expectations subscale, CFMPS-CM CFMPS- Concern over Mistakes subscale, CFMPS-OR CFMPS-Organization subscale, CFMPS-PS CFMPS- Personal Standards subscale)) (I) AOR 2.14, 95% CI 1.45–3.16 (II) AOR 2.45, 95% CI 1.46–4.13 (III) AOR 1.01, 95% CI 1.01–1.03 (IV) AOR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.10 (V) AOR 1.15, 95% CI 1.08–1.22 (VI) AOR 1.04, 95% CI 1.00–1.08 |

(I) M ( +) (II) M ( +) (III) VS ( +) (IV) VS ( +) (V) VS ( +) (VI) VS ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 49 | Matar Boumosleh & Jaalouk, 2017 | Líbano | 688 (47%) | 20.64 (1.88) | Smartphone addiction | SPAI (55.37 (15.04)) |

Depression: (I) depression score (II) personality type A (III) excessive smartphone use (≥ 5 h/ weekday) (IV) non-use of smartphone for calling family members (VI) use of smartphone for entertainment purposes Anxiety: (I) anxiety score (II) personality type A (III) excessive smartphone use (IV) non-use of smartphone to call family members (V) use of smartphone for entertainment purposes |

MLR (depression/anxiety, age, personality type, class, age at first use of smartphone, duration of smartphone use, and use of smartphone for calling family members, entertainment and other purposes) Depression: (I) 0.201*** (II) 0.130* (III) 0.262*** (IV) -0.148* (VI) 0.126* Anxiety: (I) 0.122* (II) 0.132* (III) 0.268* (IV) -0.160** (V) 0.125* |

Depression: (I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S (-) (VI) S ( +) Anxiety: (I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S (-) (V) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 50 | Pourrazavi et al., 2014 | Iran | 476 (60%) | 18 – 33 | Mobile phone problematic use | MPPUS (25.5%, NR) |

(I) Self-efficacy to avoid EMPU (II) Observational learning (III) Self-regulation (IV) Self-control (V) Attitude toward EMPU (VI) EMPU (excessive mobile phone use) |

MLR (Excessive mobile phone use, social cognitive theory constructs (self-efficacy, outcome expectation, and self-regulation), attitude, and self-control) (I) -0.34*** (II) 0.15*** (III) -0.09* (IV) -0.15*** (V) -0.20*** (VI) 0.09* |

(I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) VS ( +) (IV) S ( +) (V) S ( +) (VI) VS ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 51 | Roberts & Pirog III, 2013 | USA | 191 (41%) | 19 – 38, 21 (1) | Mobile phone addiction | MPAT (5.093 (1.272)) |

(I) Materialism (II) Impulsiveness |

PM (Impulsiveness, Materialism) (I) .332*** (II) .152* |

(I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 52 | Roberts et al., 2015 | USA | 346 (51%) | 19 – 24, 21 | Cell phone addiction | MRCPAS (NR) |

(I) Emotional instability (II) Introversion (III) Materialism (IV) Attention impulsiveness |

Hierarchical model (Seven personality factors: emotional instability, introversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, conscientiousness, materialism, and need for arousal) (I) 0.20** (II) 0.15* (III) 0.13** (IV) 0.22* |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 53 | Rozgonjuk et al., 2019 | USA | 261 (77%) | 19.73 (3.52) | Problematic smartphone use | SAS-SV (26.31 (10.35)) |

(I) Social smartphone use (II) Non social smartphone use |

SEM (Social smartphone use, Non social smartphone use, Intolerance of uncertainty) (I) 0.159* (II) 0.392*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) M ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 54 | Rozgonjuk & Elhai, 2021 | USA | 300 (76%) | 18 – 38, 19.45 (2.17) | Problematic smartphone use | SAS (93.47 (25.30)) |

(I) Age (II) Gender (being female) (III) Process smartphone use |

SEM (Age, Gender, Expressive suppression, social smartphone use, process smartphone use) (I) -0.114* (II) 0.153** (III) 0.556*** |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) (III) L ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 55 | Salehan & Negahban, 2013 | USA | 214 (39%) | 90% 18—30 | Mobile addiction | SDQ (NR) | (I) Use of mobile social networking applications |

SEM (Use of mobile social networking applications, SNS intensity, gender, network size) (I) 0.51* |

(I) L ( +) | Fair (2, 14) |

| 56 | Sun et al., 2021 | China | 800 (60%) | 19.06 (1.35) | Problematic smartphone use | MPATS (2.634 (0.699)) |

Mediation Model: (I) Age (II) Ostracism (III) Social self-efficacy Moderated Mediation Model: (IV) Rejection sensitivity (RS) |

Mediation Model (Gender, Age, Ostracism, Social self-efficacy) (I) 0.063* (II) 0.219*** (III) − 0.124** Moderated Mediation Model (Gender, Age, Ostracism, Social self-efficacy, Rejection sensitivity (RS), Ostracism × RS) (IV) 0.313*** |

(I) VS ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S (-) (IV) M ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 57 | Takao, 2014 | Japan | 396 (78%) | 18 – 25, 20.07 (1.35) | Problematic mobile phone use | MPPUS (103.7 (38.88)) |

(I) Gender (being female) (II) Extraversion (III) Low neuroticism (IV) Openness |

MR (Gender and five personality domains (extreversion, neuroticism, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness) (I) 0.12** (II) 0.24*** (III) -0.23*** (IV) 0.18*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S (-) (IV) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 58 | Wolniewicz et al., 2020 | USA | 297 (72%) | 19.70 (3.96) | Problematic smartphone use | SAS (91.52 (23.95)) |

(I) Age (II) FoMO (III) SUF |

SEM (age and sex (control variables), depression and anxiety severity (predictor variables), FOMO and boredom proneness as mediators (with boredom proneness statistically predicting FOMO)) (I) -0.26*** (II) 0.58*** (III) 0.19*** |

(I) S (-) (II) L ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 59 | Xiao et al., 2021 | China | 1267 (59%) | 18 – 30, 20.36 (0.97) | Problematic mobile phone use | MPAI (2.78 (0.72)) |

(I) alexithymia (II) social interaction anxiousness (III) boredom proneness |

Model 6 of SPSS PROCESS macro (multiple mediation model) (alexithymia, boredom proneness, social interaction anxiousness) (I) 0.25*** (II) 0.29*** (III) 0.19*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 60 | Yang et al., 2019 | China | 608 (74%) | 20.06 (1.98) | Mobile phone dependence | MPATS (42.81 (10.63)) |

(I) physical exercise (II) self-control |

Mediating Role Analysis (physical exercise, self-control) (I) -0.131** (II) -0.557*** |

(I) S (-) (II) L (-) |

Good (14) |

| 61 | Yang et al., 2021a, 2021b | China | 608 (74%) | 20.06 (1.98) | Mobile phone addiction | MPATS (78.29 (32–56), 8.06 (≥ 57)) |

(I) Gender (II) major (III) physical activity (PA) (IV) W1, separated net programs (V) W2, confrontation programs |

PROCESS macro (Model 1) (Gender, major, physical activity, W1, separated net programs; W2, confrontation programs; W3, difficulty beauty programs; PA*W1; PA*W2; PA*W3) (I) 0.271* (II) − 0.169* (III) − 0.266*** (IV) 0.263* (V) 0.445* |

(I) S ( +) (II) S (-) (III) S (-) (IV) S ( +) (V) M ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 62 | Yang et al., 2020a, 2020b | China | 1099 (59.6%) | 20.04 (1.25) | Problematic mobile phone use | MPAI (2.63 (0.63)) |

(I) Gender (being female) (II) Age (III) Boredom proneness (IV) Depression |

Mediation analysis (Gender, Age, Boredom proneness, Depression) (I) 0.44*** (II) − 0.05 (III) 0.27*** (IV) 0.17*** |

(I) M ( +) (II) VS (-) (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 63 | You et al., 2019 | China | 653 (54%) | 17 – 25, 19.94 (1.34) | Mobile phone addiction | Mobile phone addiction scale (Xiong et al., 2012) (2.73 ± 0.69) |

(I) Gender (II) socio-economic status (III) interpersonal sensitivity |

SEM (Gender, age, socio-economic status, social anxiety, self-esteem, interpersonal sensitivity) (I) 0.10* (II) 0.10** (III) 0.29** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Good (2) |

| 64 | Yuchang et al., 2017 | China | 297 (45%) | 17 – 24, 20.24 (1.08) | Smartphone Addiction | SAS-SV (23.75 (7.47), 27.92% (≥ 31 M, ≥ 33 F)) |

(I) Anxiety (II) self-esteem |

SEM (Anxiety attachment dimension, depend attachment dimension, close attachment dimension, dysfunctional attitudes, self-esteem) (I) -0.218** (II) − 0.357** |

(I) S (-) (II) M (-) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 65 | Zhang et al., 2020b | China | 764 (59%) | 19.83 (1.10) | Problematic Smartphone Use | MPAI (2.66 (0.58)) | (I) Interpersonal adaptation |

Moderated mediation analysis (Control variables: gender, grade; Predictor: parental attachment; Mediator: interpersonal adaptation; Moderator: self − control; Interaction: interpersonal adaptation × self-control) (I) − 0.10** |

(I) S (-) | Good (2) |

| 66 | Zhang et al., 2020a | China | 1304 (60%) | 18 – 22, 19.71 (1.03) | Smartphone use disorder | MPAI (1.99 (0.58)) |

(I) Future time perspective (II) Depression |

MLR (future time perspective (FTP), depression) (I) -0.13*** (II) 0.70*** |

(I) S (-) (II) L ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 67 | Zhu et al., 2019 | China | 356 (64%) | 17 – 19, 18.33 (0.57) | Smartphone use disorder | MPAI (2.51 (0.64)) |

(I) perceived discrimination (II) school engagement (III) parental rejection |

Mediation Model Test (perceived discrimination, school engagement, parental rejection) (I) -0.19** (II) -0.16** (III) 0.14* |

(I) S (-) (II) S (-) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| Problematic social media use (PSMU) | ||||||||||

| Prospective cohort studies | ||||||||||

| 68 | Brailovskaia et al., 2018 | Germany | 122 (82.8%) | 17 – 38, 21.70 (3.67) | Facebook Addiction Disorder | BFAS (8.98 (3.64)) | (I) Physical activity |

Bootstrapped mediation analysis (Physical activity, daily stress) (I) -0.796* |

(I) L (-) | Good (14) |

| 69 | Brailovskaia & Margraf, 2017 | Alemania | 179 (77%) | 17 – 58, 22.52 (5.00) | Facebook addiction disorder | BFAS (9.77 (3.86)) | (I) Narcissism |

Bootstrapped mediation analysis (Narcissism, Stress symptoms) (I) 0.259* |

(I) S ( +) | Good (14) |

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||||||

| 70 | Aladwani & Almarzouq, 2016 | Kuwait | 407 (46%) | 20.04 (1.16) | Compulsive social media use | CIUS (2.51 (0.71)) |

(I) Self-esteem (II) Interaction anxiousness |

PM (Self-esteem, Interaction anxiousness) (I) − 0.22* (II) 0.24** |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 71 | Balcerowska et al., 2019 | Poland | 486 (64%) | 21.56 (4.50) | Facebook addiction | BFAS (12.88 (4.93)) |

(I) Gender (II) Admiration demand (III) Self-sufficiency |

MHR (Gender, age, Big Five personality traits (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to experience, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness), and four dimensions of narcissism (Lead-ership, Vanity, Self-sufficiency and Admiration Demand)) (I) –0.23*** (II) 0.37*** (III) –0.18*** |

(I) S (-) (II) M ( +) (III) S (-) |

Good (14) |

| 72 | Casale et al., 2018 | Italy | 579 (54.6%) | 22.39 (2.82) | Social media problematic use | BSMAS (11.96 (4.99)) |

Females: (I) fear of missing out (II) self-presentational social skills (III) positive metacognitions Males: (I) fear of missing out (II) positive metacognitions |

SEM (Fear of negative evaluation, Fear of missing out, Self-presentational skills, Positive metacognitions) Females: (I) 0.34*** (II) 0.38*** (III) 0.42* Males: (I) 0.38* (II) 0.28* |

Females: (I) M ( +) (II) M ( +) (III) M ( +) Males: (I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 73 | Casale & Fioravanti, 2018 | Italy | 535 (50.08%) | 22.70 (2.76) | Facebook addiction | BFAS (1.67 (0.64)) |

(I) Need to belong (II) Need for admiration |

SEM (effects of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism on Fb addiction levels via the need to be admired and the need to belong) (I) 0.38* (II) 0.26* |

(I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 74 | Casale & Fioravanti, 2017 | Italy | 590 (53.2% female) | 22.29 (2.079) | Problematic Social Networking Sites Use | GPIUS-2 (33.14 (16.03)) |

(I) Experiences of Shame (II) Escapism (III) Control over self-presentation (IV) Approval/acceptance |

SEM (effects of shame on problematic SNS use through perceived relevance/benefits of CMC (i.e. control over self-presentation, escapism, and approval/acceptance) (I) 0.44* (II) 0.15* (III) 0.11* (IV) 0.27* |

(I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 75 | Chung et al., 2019 | Malaysia | 128 (52%) | 18 – 29, 19.73 (1.99) | Social media addiction | BSMAS (16.74 (4.16)) |

(I) Gender (being a female) (II) Social media usage (III) Psychopathy |

HMR ( Age, gender, social media usage, impulsivity, and the Dark Tetrad traits (Machiavellianism, narcissism, psychopathy, and sadism) (I) − 0.18* (II) 0.19* (III) 0.28** |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 76 | Demircioğlu & Köse, 2020 | Turkey | 400 (66%) | 18 – 42, 21.36 (2.20) | Social Media Addiction | Social Media Addiction Scale (2.18 (0.70)) |

(I) Fearful attachment (II) Preoccupied attachment (III) Self-esteem |

SEM (Fearful attachment, Preoccupied attachment, Secure attachment, Self-esteem; moderator: Gender) (I) 0.012* (II) 0.12** (III) -0.27*** |

(I) VS ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S (-) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 77 | Demircioğlu & Göncü Köse, 2021 | Turkey | 229 (68%) | 18 – 32, 21.51 (1.80) | Social Media Addiction | Social Media Addiction Scale (2.15 (0.70)) |

(I) Relationship satisfaction (II) fearful attachment (III) rejection sensitivity (IV) psychopathy |

SEM (Relationship satisfaction, Attachment styles (Secure Attach, Fearful Attach, Preoccupied Attach, Dismissive Attach), Rejection Sensitivity, Dark triad personality traits (Narcissism, machiavellianism, psychopathy)) (I)—0.16* (II) 0.14* (III) 0.15* (IV) 0.17* |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 78 | Dempsey et al., 2019 | USA | 291 (57.6%) | 18—25 (20.03 (3.06)) | Problematic Facebook Use | BFAS (11.33 (5.06)) |

(I) Age (II) FoMO (III) Rumination (IV) Facebook use frequency |

SEM (age and gender as covariates; FoMO, Rumination, depression severity, social anxiety, life satisfaction, Facebook use frequency) (I) 0.14* (II) 0.26*** (III) 0.13* (IV) − 0.35*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) M (-) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 79 | Duran, 2015 | Spain | 199 (72%) | 18–22 (females: 19.09 (1.29), males: 19.19 (1.28)) | Tuenti addiction | CERI (1.44 (0.79)) |

(I) Comunicación Privada (II) Actitud positiva hacia la aceptación madre como contacto Tuenti |

Análisis de regresión jerárquica (usos de la red social Tuenti, actitudes hacia la aceptación de los padres, y género) (Paso 1: Comunicación Privada, Aceptación madre; Paso 2: Comunicación Privada x Género) (I) 0.20* (II) -0.16* |

(I) S ( +) (II) S (-) |

Good (14) |

| 80 | Foroughi et al., 2021 | Malaysia | 364 (51.1%) | 19 – 26 | Instagram addiction | BFAS (NR) |

(I) recognition needs (II) social needs (III) entertainment needs |

SEM (Academic performance, depression, entertainment needs, information needs, Instagram addiction, life satisfaction, recognition needs, social anxiety, social needs, physical activity) (I) 0. 295** (II) 0.243** (III) 0.207** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 81 | Gao et al., 2021 | China | 849 (47%) | 19.0 (1.36) | Excessive WeChat use | Excessive WeChat Use scale (2.54 ( 0.76)) |

(I) Depression (II) Anxiety (III) WeChat use intensity |

Mediation analysis (Psychological needs satisfaction, anxiety, depression and WeChat use intensity) (I) 0.184*** (II) 0.194*** (III) 0.515*** |

(I) S (-) (II) S (-) (III) L ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 82 | Hong et al., 2014 | China | 215 (46%) | 18 – 22 | Facebook addiction | IAT (Withdrawal 5.55 (2.90); Tolerance 9.26 (3.58); Life problems 7.29 (3.29); Substitute satisfaction 8.49 (3.33)) |

(I) Depressive character (II) Facebook usage |

SEM (self-esteem, social extraversion, sense of self-inferiority, neuroticism, and depressive character, the mediating variable was Facebook usage) (I) 0.21* (II) 0.62*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) L ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 83 | Hong & Chiu, 2016 | China | 206 (53%) | 18 – 22 | Facebook addiction | IAT (Withdrawal and tolerance 6.37 (3.30); Life problems 5.93 (2.91); Substitute satisfaction 8.86 (3.66)) |

(I) Online psychological privacy (II) Facebook usage motivation (III) Facebook usage |

SEM (online psychological privacy, Facebook usage motivation, Facebook usage) (I) 0.302*** (II) 0.439*** (III) 0.296*** |

(I) M ( +) (II) M ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 84 | Hou et al., 2017a | China | 1245 (52%) | Sample 1: 20.7 (2.1); Sample 2: 19.8 (1.3) | WeChat Excessive Use | WeChat Excessive Use Scale (WEUS) (13.6% (15.1–21.4), 8.2% (21.4–27.7), 6.6% (> 27.7)) |

(I) External locus of control (II) Online social interaction |

Mediation analysis (external locus of control, online social interaction) (I) 0.14* (II) 0.30* |

(I) S ( +) (II) M ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 85 | Hou et al., 2017b | China | 499 (77.6%) | 19.90 (1.35) | Problematic SNS usage | FIQ (19.61 (6.15)) |

(I) Gender (being female) (II) Perceived stress (III) Psychological resilience |

HMR (Age, gender, Perceived stress, Psychological resilience, Stress ∗ resilience) (I) 0.16** (II) 0.21** (III) -0.09*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) VS (-) |

Good (14) |

| 86 | Hou et al., 2019 | China | 641 (74.4%) | 19.90 (1.37) | Problematic SNS usage | FIQ (19.43 (7.14)) |

(I) Age (II) Depression (III) Anxiety |

Moderated mediation model (Gender, age, Perceived stress, Depression, Anxiety) (I) 0.14** (II) 0.14* (III) 0.12* |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 87 | Jaradat & Atyeh, 2017 | Jordan | 380 (72.9%) | 86% 20 – 25 | Social Media Addiction | IAT (Withdrawal 2.63 (1.05); Tolerance 3.06 (1.20); Life problems 3.12 (0.96)); Substitute satisfaction 2.98 (0.10)) |

(I) Neuroticism (II) Openness (III) Extraversion |

Hypothetical model (the relationships among the five personality trait factors (neuroticism, openness, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness), Social media addiction and the moderator variables Gender, Age, College Expense and Experience) (I) -0.244*** (II) 0.182*** (III) 0.150*** |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Good |

| 88 | Jasso-Medrano & Lopez-Rosales, 2018 | Mexico | 374 (58.6%) | 18 – 24, 20.01 (1.84) | Addiction to social media | Social Network Addiction Questionnaire (2.33 (0.71)) |

(I) Frequency of the use of mobile devices (II) Daily hours of use (III) Suicidal ideation (IV) Depression |

SEM (Daily hours, mobile use, suicidal ideation, depression) (I) 0.21*** (II) 0.42*** (III) -0.21** (IV) 0.46*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) M ( +) (III) S (-) (IV) M ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 89 | Kircaburun & Griffiths, 2018 | Turkey | 752 (69%) | 18 – 24, 20.30 (1.46) | Instagram addiction | IAT (26.5% (38–58), 6.1% (59–73), 0.9% (> 73)) |

(I) Agreeableness (II) Self-liking (III) Daily Internet use |

SEM (self-liking between Instagram addiction and the Big Five personality dimensions (neuroticism, openness, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness)) (I) − 0.17** (II) − 0.14** (III) 0.20** |

(I) S (-) (II) S (-) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 90 | Kircaburun et al., 2020a, 2020b | Turkey | 460 (61%) | 18 – 26, 19.74 (1.49) | Problematic social media use | Social Media Use Questionnaire (24.10 (6.73)) |

(I) self-confidence (II) self/everyday creativity (III) depression |

SEM (task-oriented, self-confidence, risk-taking, self/everyday creativity, depression, loneliness, internal motivation, loneliness) (I) − 0.16* (II) − 0.23* (III) 0.23** |

(I) S (-) (II) S (-) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 91 | Kircaburun et al., 2020b | Turkey | 1008 (60.5%) | 17 – 32, 20.49 (1.73) | Problematic social media use | Social Media Use Questionnaire (15.21 (7.48)) |

(I) Gender (being female) (II) neuroticism (III) agreeableness (IV) extraversion (V) conscientiousness (VI) Instagram use (VII) Snapchat use (VIII) Facebook use (IX) Passing time (X) Maintaining existing relationships (XI) Meeting new people and socializing (XII) entertainmental use (XIII) informational and educational use |

HR (gender, age, personality traits (neuroticism, openness, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness), most used social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, Whatsapp, Twitter, Scapchat, Youtube, Google), and social media use motives (maintaining existing relationships, meet new people and socializing, make, express, or present more popular oneself, pass time, as a task management tool, entertainmental, informational and educational)) (I) − 0.19*** (II) 0.10*** (III) 0.06* (IV) − 0.08** (V) − 0.06* (VI) 0.10*** (VII) 0.08* (VIII) 0.06* (IX) 0.27*** (X) 0.12*** (XI) 0.12*** (XII) 0.08* (XIII) − 0.07* |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) (III) VS ( +) (IV) VS (-) (V) VS (-) (VI) S ( +) (VII) VS ( +) (VIII) 0.06* (IX) S ( +) (X) S ( +) (XI) S ( +) (XII) VS ( +) (XIII) VS (-) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 92 | Lee, 2019 | Malaysia | 204 (60%) | 18 – 27, 22.94 (3.43) | SNS addiction | BFAS (NR) |

(I) Age (II) Gender (being female) (III) Openness (IV) Psychopaty |

HR (Age, gender, five-factor model (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness), dark triad (psychopaty, machiavellianism,narcissism)) (I) -0.14* (II) -0.17* (III) -0.20** (IV) 0.23* |

(I) S (-) (II) S (-) (III) S (-) (IV) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 93 | Marino et al., 2016 | Italy | 815 (77%) | 18 – 35, 21.17 (2.15) | Problematic Facebook use | GPIUS-2 (28.74 (14.12)) |

(I) coping (II) conformity (III) enhancement (IV) extraversion (V) negative beliefs about thoughts (VI) cognitive confidence |

PM (Personality traits (agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, extraversion, and openness), Motives for using Facebook (coping, conformity, enhancement, and social motive) and metacognitions (positive beliefs about worry, negative beliefs about thoughts, lack of cognitive confidence, beliefs about the need to control thoughts and cognitive self-consciousness)) (I) 0.42** (II) 0.28** (III) 0.17** (IV) 0.09* (V) 0.12** (VI) 0.08* |

(I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) VS ( +) (V) S ( +) (VI) VS ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 94 | Punyanunt-Carter et al., 2018 | USA | 396 (71%) | 21.51 (2.41) | Social media addiction | BFAS (NR) |

(I) Introversion (II) Social media Communication Apprehension |

ML (Introversion, Social media Communication Apprehension) (I) -0.12* (II) 0.17** |

(I) S (-) (II) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 95 | Raza et al., 2020 | Pakistan | 280 (60%) | 90% 18 – 27 | Intensive Facebook usage | Items adapted from Su and Chan (2017) (NR) |

(I) Information seeking (II) Subjective norms (III) Social relationship |

PLS-SEM (Uses and gatifications theory: escape, information seeking, ease of use, social relationship, career opportunities, and education; theory of planned behavior: social influence, perceived behavioral, control, and attitude) (I) 0.105* (II) 0.229*** (III) 0.167*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 96 | Satici & Uysal, 2015 | Turkey | 311 (58%) | 18 – 32, 20.86 (1.61) | Problematic Facebook use | BFAS (32.43 (14.83)) |

(I) life satisfaction (II) subjective vitality (III) flourishing |

MR (life satisfaction, flourishing, subjective happiness, and subjective vitality) (I) -0.18** (II) -0.15* (III) -0.15** |

(I) S (-) (II) S (-) (III) S (-) |

Good (14) |

| 97 | Sayeed et al., 2020 | Bangladesh | 405 (49%) | 21.03 (1.94) | Facebook addiction | BFAS (36.9%) |

(I) domestic violence (II) sleeping more than 6–7 h per day (III) depressive symptoms (IV) spending 5 h or more per day using Facebook |

BLogR (University, Failure in love, Domestic violence, Smoking history, Sleeping status, Drug addiction, Depression status, Stressful life event, Facebook use per day, Facebook use for educational purposes, Online shopping) (I) AOR 2.519; 95% CI: 1.271–4.991; p < 0.01 (II) AOR 2.112; 95% CI: 1.246–3.582; p < 0.01 (III) AOR 1.667; 95% CI: 1.055–2.634; p < 0.05 (IV) AOR 1.670; 95% CI: 1.063–2.623; p < 0.05 |

(I) M ( +) (II) M ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 98 | Shan et al., 2021 | China | 607 (63%) | 18 – 23, 19.24 (1.01) | Social Networking Sites Addiction | Social Networking Sites Addiction Scale (2.85 (0.70)) |

Model 1 (I) Rejection sensitivity (II) Psychological capital Model 2 (I) Rejection sensitivity (II) Fearful avoidant style Model 5 (I) Rejection sensitivity (II) Psychological capital (III) Secure style |

Model 1. Multiple mediation regression analysis (Rejection sensitivity, Psychological capital, Attachment styles) (I) 0.152*** (II) − 0.151*** Model 2. Multiple mediation regression analysis (Rejection sensitivity, Psychological capital, Fearful avoidant style) (I) 0.134*** (II) 0.322*** Model 5. Multiple mediation regression analysis (Rejection sensitivity, Psychological capital, Secure style) (I) 0.152*** (II) -0.151*** (III) -0.166*** |

Model 1 (I) S ( +) (II) S (-) Model 2 (I) S ( +) (II) M ( +) Model 5. (I) S ( +) (II) S (-) (III) S (-) |

Good (14) |

| 99 | Sheldon et al., 2021 | USA | 337 (57%) | 23.35 (8.08) | Facebook addiction, Instagram addiction, Snapchat addiction | BFAS, replacing the word “Facebook” (1.91 (0.73)) with “Instagram” (2.26 (0.93)) and “Snapchat” (2.08 (0.94)) for those platforms, respectively |

Facebook addiction: (I) FOMO Instagram addiction: (I) FOMO Snapchat addiction: (I) FOMO (II) Social activity |

Facebook addiction: HLR (FOMO, Interpersonal interaction, Life satisfaction) (I) 0.35*** Instagram addiction: HLR (FOMO, conscientiousness, extraversion) (I) 0.43*** Snapchat addiction: HLR (FOMO, extraversion, social activity) (I) 0.40*** (II) 0.13* |

Facebook addiction: (I) M ( +) Instagram addiction: (I) M ( +) Snapchat addiction: (I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 100 | Siah et al., 2021 | Malaysia | 219 (57%) | 19 – 25, 21.46 (1.17) | Social Media Addiction | BSNAS (NR) |

(I) Narcissism (II) Avoidance (III) Gender |

SEM (Dark Triad Personalities (Machiavellianism,narcissism, psychopathy), Coping Strategies (avoidance, positive thinking, roblem solving, social support)) (I) 0.17* (II) 0.25* (III) 0.15*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 101 | Süral et al., 2019 | Turkey | 444 (75%) | 18 – 43, 20.45 (3.57) | Problematic social media use | SMUQ (2.71 (0.75)) |

(I) Trait emotional intelligence (TEI) (II) “maintain my existing relationships” (III) “meet new people and socialize” (IV) “express or present myself as being more popular” (MEPO) (V) “pass time” (PT) (VI) “entertain myself” (V) “manage my tasks and media (videos, photos, etc.)” |

PM (Trait emotional intelligence, Social Media Use Motives (“maintain my existing relationships”, “meet new people and socialize”, “express or present myself as being more popular”, “pass time”, (v) “entertain myself”, “manage my tasks and media (videos, photos, etc.)”, and “access information and education”)) (I) − 0.39*** (II) 0.09* (III) 0.13** (IV) 0.13** (V) 0.13* (VI) 0.11* (V) 0.08* |

(I) M (-) (II) VS ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) S ( +) (V) S ( +) (VI) S ( +) (V) VS ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 102 | Uysal, 2015 | Turkey | 229 (52%) | 18 – 27, 21 (1.64) | Problematic Facebook use | BFAS (30.09 (10.21)) |

(I) Social safeness (II) Flourishing |

MHR (Age, gender, social safeness, flourishing, internet usage time) (I) -0.29** (II) -0.24** |

(I) S (-) (II) S (-) |

Good (14) |

| 103 | Varchetta et al., 2020 | Italy | 306 (50%) | 18 – 30, 21.80 (3.19) | Social Media Addiction | BSMAS (2.21 (0.81) |

(I) FOMO (II) frequency of social network use during the main daily activities (Social Media Engagement Scale, SMES) |

LR (FOMO, SMES) (I) 0.61*** (II) 0.27*** |

(I) L ( +) (II) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 104 | Xie & Karan, 2019 | USA | 526 (41%) | 18 – 29, 24.21 (5.92) | Facebook addiction | BFAS (3.15 (0.71)) |

(I) Facebook use intensity (II) Facebook use for broadcasting (III) Trait anxiety |

HR (Block 1: age, gender, education, household income, white; Block 2: trait anxiety; Block 3: Facebook use intensity; Block 4: Facebook activities (Broadcasting, directed communication); Block 5: Gender × Trait anxiety) (I) 0.57*** (II) 0.20** (III) 0.12* |

(I) L ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Good (3) |

| 105 | Yu & Luo, 2021 | China | 390 (55%) | 19.09 (1.47) | Social Networking Addiction | SMD (2.80 (2.21)) |

(I) Reactive restriction (II) Limiting online behaviors |

LogR (Block 1: Gender, age; Block 2: Reactive restriction, internet-specific rules, limiting online bhaviors, quality of communication) (I) OR 1.78; 95%CI = 1.24–2.55 (II) OR 1.72; 95%CI = 1.11–2.65 |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 106 | Yu & Chen, 2020 | Taiwan | 316 (72%) | 20.95 (2.70) | Social Networking Addiction | BSMAS (NR) |

(I) frequency of Facebook Stories updates (II) time spent reading Facebook Stories |

MIMIC (Frequency of Facebook Stories updates, frequency of news feed updates, time spent reading Facebook Stories, time spent reading Facebook news feeds) (I) 0.49* (II) 0.13* |

(I) L ( +) (II) S (-) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) | ||||||||||

| Prospective cohort studies | ||||||||||

| 107 | Dang et al., 2019 | China | 283 (60%) | 18 – 27, 20.47 (1.15) | IGD | DSM-5 IGD scale (1.45 (1.97)) | (I) depression (W2) |

Prospective Model (trait emotional intelligence (W1), coping flexibility (W2), and depression (W2) on IGD tendency (W2)) (I) 0.29*** |

(I) S ( +) | Good (14) |

| 108 | Yang et al., 2021a, 2021b | China | 244 (70%) | 18 – 22 (19.88) | IGD | IAT (29.59 (13.07)) |

(I) grade point average (T1) (II) IGD (T1) |

CL (social cynicism, IGD, and grade point average, after controlling age and gender at T1) (I) -0.17** (II) 0.62*** |

(I) S (-) (II) L ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 109 | Yuan et al., 2021 | China | 341 (75.7%) | 21.24 (2.72) | IGD | IGD Questionnaire (Petry et al., 2014) (1.30 (1.98)) | (I) Depression symptoms (T1) |

Mediation model (Age, gender, depression (T1), FoMO (T2), problematic smartphone use (T3)) (I) 0.31*** |

(I) M ( +) | Fair (3, 13, 14) |

| 110 | Zhang et al., 2019 | China | 469 (58%) | 18 – 27, 19.29 (1.10) | IGD | DSM-5 IGD scale (1.445 (1.968)) |

(I) Purpose in life (W1) (II) IGD symptoms (W1) |

CL (W1, W2: Social support, Purpose in life, IGD symptoms) (I) − 0.173*** (II) 0.365*** |

(I) S (-) (II) M ( +) |

Good (14) |

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||||||

| 111 | Borges et al., 2019 | Mexico | 7022 (55%) | 72.4% 18 – 19 | IGD | Instrument based on the nine symptoms described in the DSM-5 and formulated by Petry et al. (2015) (5.2% DSM-5 IGD (positive to five or more criteria)) |

(I) Lifetime psychological (II) Lifetime medical treatment (III) Lifetime any treatment (IV) Severe impairment – home (V) Severe impairment – work/school (VI) Severe impairment – relationships (VII) Severe impairment – social (VIII) Severe impairment – total |

LogR (controlling for sex and age group, Lifetime psychological, Lifetime medical treatment, Lifetime any treatment, 12-month treatment, Severe impairment – home, Severe impairment – work/school, Severe impairment – relationships, Severe impairment – social, Severe impairment – total) (I) 1.9* [1.4–2.4] (II) 1.8* [1.1–3.0] (III) 1.8* [1.4–2.4] (IV) 2.1* [1.1–3.8] (V) 2.6* [1.7–4.1] (VI) 1.8* [1.1–2.8] (VII) 1.9* [1.3–3.0] (VIII) 2.4* [1.7–3.3] |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) (IV) M ( +) (V) M ( +) (VI) S ( +) (VII) S ( +) (VIII) M ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 112 | Kim & Kim, 2017 | Korea | 179 (39.1%) | 19 – 29, 75.4% 19 – 24 | Excessive online game usage | Items based in Young (1998b) and Chin (1998) (2.252 (0.832)) |

(I) Escaping from loneliness (II) Expanding online bridging social capital (III) Strengthening offline bonding social capital |

SEM (Escaping from loneliness, Expanding online bridging social capital, Strengthening offline bonding social capital) (I) 0.44*** (II) 0.221* (III) 0.185* |

(I) M ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| 113 | Li et al., 2016 | China | 654 (54%) | 18—22 (20.29 (1.39)) | Online game addiction | OGCAS (22.92 (9.22); 4.7% (≥ 32, and CIASa ≥ 5)) | (I) Avoidant Coping Styles |

SEM (Avoidant Coping Styles, stressful life events, neuroticism, stressful live events*neuroticism, Avoidant Coping Styles*neuroticism, controlling for relevant variables (i.e., gender and college year)) (I) 0.199*** |

(I) S ( +) | Fair (2, 14) |

| 114 | Li et al., 2021 | China | 508 (24%) | 18.54 (0.86) | Internet gaming addiction | GAS (2.99 (0.93) |

(I) Actual-ideal self-discrepancy (II) Avatar identification (III) Locus of control |

SEM (avatar identification, actual-ideal self-discrepancy, locus of control, locus of control*actual-ideal self-discrepancy, locus of control*avatar identification) (I) 0.15** (II) 0.24*** (III) 0.37*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) M ( +) |

Good (14) |

| 115 | Mills & Allen, 2020 | USA | 487 (50.3%) | 18 – 40, 19.50 (1.90) | IGD | IGD Scale (0.65 (0.77)) |

(I) Gender (male) (II) General motivation (III) Introjected (IV) Amotivation (V) Self-control |

SEM (Gender, Self-Control, Need Frustration, Need Satisfaction, Weekly Playtime, gaming motivations (general, intrinsec, identified, introjected, amotivation, external)) (I) NR (II) 0.59* (III) 0.36* (IV) 0.12* (V) -0.20* |

(I) NR (II) L ( +) (III) M ( +) (IV) S ( +) (V) S (-) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| Problematic internet pornography use (PIPU) | ||||||||||

| Prospective cohort studies | ||||||||||

| 116 | Grubbs et al., 2018 | USA | 1507 (34.5%) | 19.3 (2.2) | Perceived addiction to internet pornography | CPUI‐9 (1.7 (0.9)) |

(I) Gender (being male) (II) Access efforts (T1) (III) Perceived compulsivity (T1) (IV) Emotional distress (T1) |

MR (personality variables, moral disapproval, religiousness, pornography use and male gender) (I) 0.14* (II) 0.18** (III) 0.30*** (IV) 0.29*** |

(I) S ( +) (II) S ( +) (III) M ( +) (IV) S ( +) |

Fair (2, 14) |

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||||||

| 117 | Chen et al., 2018 | China | 808 (42%) | 17 – 22, 18.54 (0.75) | Problematic Pornography Use | PIPUS (7.13 (8.48)) |

(I) Age (II) Gender (being male) (III) Online sexual activities (IV) Third-person effect |

Bootstrapping (Age, gender, sexual sensation seeking, online sexual activities, third-person effect, online sexual activities * third-person effect) (I) − 0.05* (II) − 0.04*** (III) 0.50*** (IV) 0.36*** |

(I) VS (-) (II) VS ( +) (III) L ( +) (IV) M ( +) |

Good (14) |

AOR adjusted odds ratio; h hour; IGD Internet gaming disorder; M Average; min: minutes; NR not reported; OR odds ratio; SD Standard deviation; USA United states of America