Abstract

Background:

Research priorities are often set by expert clinicians and researchers.

Objective:

Apply an established process in patient-centered research to engage survivors and their caregivers in prioritizing research topics in prostate cancer.

Design, setting, and participants:

A Prostate Cancer Patient Survey Network (PSN), formed in partnership with Us TOO and the NASPCC, engaged in a series of mixed-methods studies to prioritize comparative effectiveness research questions. This was accomplished through an iterative process that included two survey rounds and multidisciplinary working groups.

Results and limitations:

There were 591 and 706 survey respondents in the first and second rounds, respectively, with most having had localized prostate cancer (58.1%). Survey participants represented 45 states in the US. Five of the top eleven prioritized research questions related to treatment decision-making and/or survivorship care. The following had the highest overall importance ratings: What is the comparative effectiveness of different: (1) strategies to improve counseling regarding the side effects of prostate cancer treatment; (2) tools for decision-making in localized prostate cancer; and (3) sequences of treatments for metastatic prostate cancer?

Conclusions:

We present a unique, patient-centered list of prioritized research questions among prostate cancer patients and their caregivers. These research questions may inform funding decisions for organizations that support research, and should be considered as priorities for clinicians, researchers, and institutions conducting prostate cancer research.

Patient summary:

Prostate cancer is a common disease that affects 1 in 9 men over their lifetime. Researchers usually identify questions to study without asking men with prostate cancer. Here we asked survivors of prostate cancer and their caregivers to help us. They identified research questions and topics that are important to them. Researchers can focus on this list of questions to help men with prostate cancer. Groups who pay for research studies can make these questions their priority.

Keywords: Comparative effectiveness research, Community-based participatory research, Patient-centered outcomes research, Prostate cancer, Research priorities

INTRODUCTION

The Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) was authorized by Congress in 2010 and was charged with helping patients, caregivers, healthcare providers, and other stakeholders navigate the challenges of making health decisions. Through PCORI, patient-centered research has emerged as a discipline rooted in core tenets of patient and community engagement. A patient-centered research study is consequently built on principles of reciprocal relationships, co-learning, partnership, and transparency, honesty, and trust.1 Successfully navigating these fundamental components of patient-centeredness and engagement drives quality and value in health-related research activities for all stakeholders.2 Prostate cancer is the most common non-dermatologic malignancy among men in the US.3 The annual cost of prostate cancer care in the US was estimated around $19.8 billion in 2020.4 And yet few large clinical studies exist presently that were built on a foundation of engagement and patient-centeredness in prostate cancer care.

In 2018, our team demonstrated a novel research approach that utilized a Patient Survey Network (PSN) to prioritize comparative effectiveness research questions for bladder cancer patients.5 This work created a template for sustainable patient engagement in the preparatory phase of patient-centered and community-based oncologic research. The bladder cancer PSN provided patients and caregivers the opportunity to drive research prioritization in bladder cancer care, and the product of this work set funding agendas and fueled the development of a clinical trial.6 In this study, we aimed to use the learned experiences from the bladder PSN to develop and prioritize comparative effectiveness research questions in prostate cancer. We estimated that patient and caregiver priorities for research may uncover priorities that differ from the current investigator-driven priorities in prostate cancer clinical trials and research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a prospective study in which we assessed research priorities among prostate cancer patients and their caregivers. In partnership with the prostate cancer advocacy networks Us TOO and the National Alliance of State Prostate Cancer Coalitions (NASPCC), we developed the Prostate Cancer PSN to engage patients in a mixed-method, qualitative process to generate and rank patient-derived comparative effectiveness research questions. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this study.

We queried the membership of both Us TOO and the NASPCC via their email distribution networks to invite prostate cancer survivors and their caregivers to join the Prostate Cancer PSN. These invitations were circulated a total of 3 times over the course of 4 weeks for each round of the survey. Patients and caregivers who were interested in joining the Prostate Cancer PSN provided electronic informed consent which was entered into a HIPAA-compliant, secure REDCap database. Participants provided their demographic data including date of birth, age at diagnosis, gender, race/ethnicity, state of residence, household income, education level (highest attained degree), prostate cancer staging category (i.e., localized, recurrent, or advanced/metastatic), treatments received, and date of last treatment. Similarly, enrolled caregivers were asked to provide their date of birth, gender, race/ethnicity, state of residence, income, education level, and information about the prostate cancer staging category of the patients for whom they cared. All Prostate Cancer PSN participants were asked about their willingness to be contacted for future PSN iterations.

Survey Development and Administration

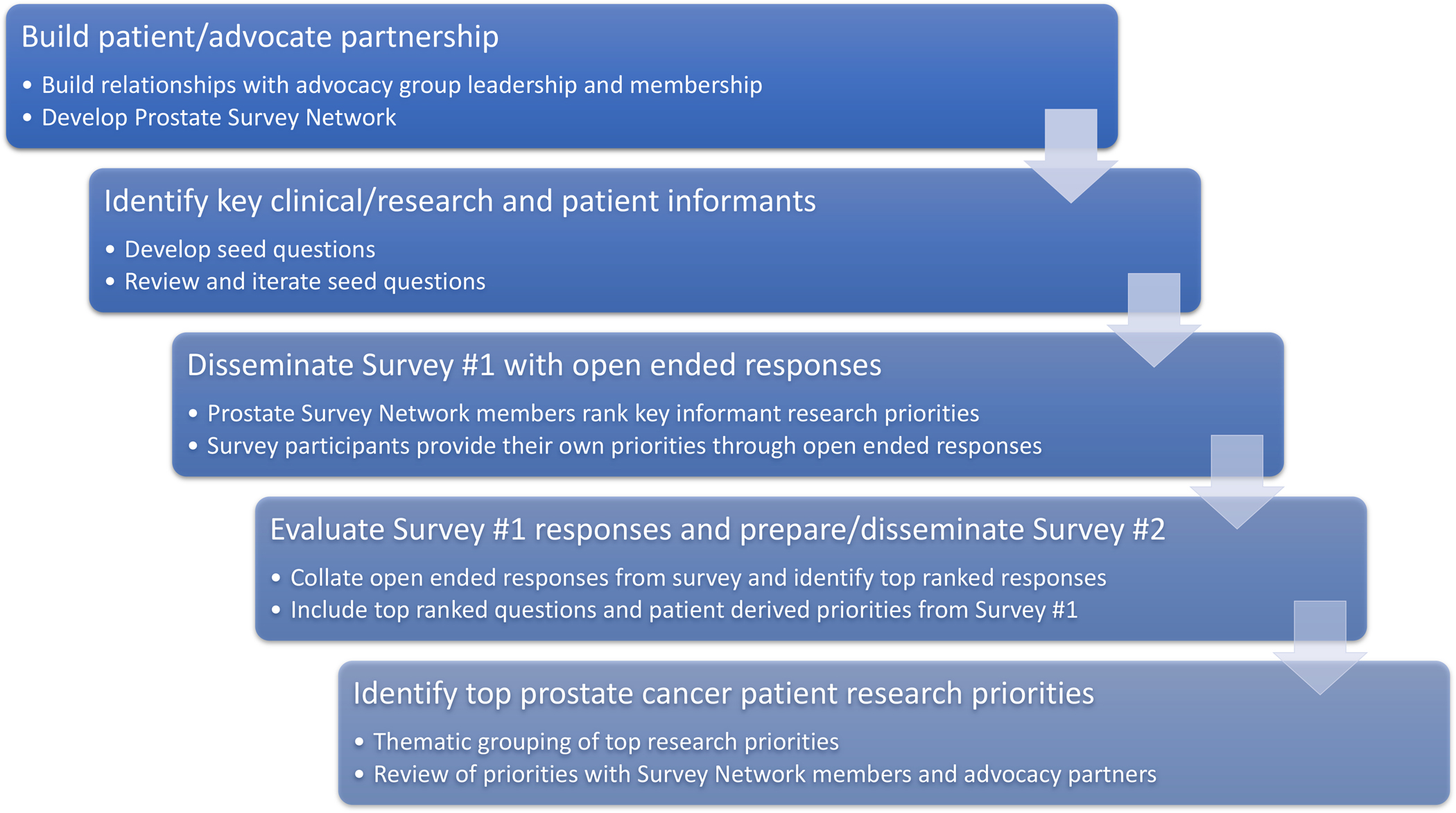

An initial list of prostate cancer-related research questions was derived from iterative review by expert prostate cancer researchers (Figure 1). These seed questions were categorized into three topic areas: (1) localized, (2) recurrent, and (3) advanced prostate cancer. These seed questions were reviewed by our patient advocate partners (J.S., M.C., M.G., T.K.), edited, amended, and revised into a first-round survey. Survey modifications included rewording existing seed questions to make the language more patient-centered and clear, and the addition of research questions felt to be important to prostate cancer patients.

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of a patient-centered approach to developing research priorities in prostate cancer.

In the first round of the survey distributed in November-December 2019, participants were asked to rate the importance of the research questions using a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from “very important” to “not important”. Additionally, survey participants were asked to denote their highest ranked question among the listed comparative effectiveness research questions. Lastly, survey participants were provided with an opportunity to contribute their own research questions with an open-text response format.

The free text responses from the first phase of this study were compiled and rewritten as comparative effectiveness research questions. Two researchers (Y.N., A.L.) grouped the open text comparative effectiveness research questions into themes and identified the most commonly contributed research questions, which were shared with our patient advocate partners to confirm the final questions to be incorporated into the final second-round survey.

In the second-round survey, distributed in April-May 2020, the top-ranked first-round comparative effectiveness research questions and survey participant-derived comparative effectiveness research questions were recirculated to the Prostate Cancer PSN members. As part of our modified Delphi process for building consensus around the research priorities, we intentionally designed the study so that the same participants could take part in multiple rounds of the survey. The same approach was taken for the prioritization of research questions in our Bladder Cancer PSN.5 Additional communications were sent through Us TOO and NASPCC email distribution lists. Participants again rated the importance of the research questions and denoted their highest ranked question among the listed comparative effectiveness research questions.

Survey Analysis

The research questions were sorted by importance ratings and by frequency of priority ranking. The rankings were identical to the importance ratings for all prostate cancer categories. We present descriptive statistics for the demographics of the Prostate Cancer PSN and for the ranked PSN questions.

RESULTS

There were 591 survey respondents for the first-round and 706 respondents for the second-round of the Prostate Cancer PSN. Among second round-survey respondents that responded to the question, 493 of 590 (83.6%) agreed to be contacted for future PSN interactions. Table 1 displays the demographic and clinical characteristics of survey respondents. The majority of PSN members were white (91.2%). Respondents were geographically distributed across the US, with participants from 45 of the 50 United States. The most common treatments received among PSN members were radical prostatectomy, androgen deprivation therapy, and external beam radiation therapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Prostate Cancer Patient Survey Network (PSN) participants.

| Prostate Cancer PSN

Participant |

||

|---|---|---|

| Patient | Caregiver | |

|

| ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 69.7 (7.6) | 62.3 (10.3) |

| Gender, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 638 (100) | 22 (40.0) |

| Female | 33 (60.0) | |

| Race, No. (%) | ||

| White | 576 (92.0) | 48 (87.3) |

| Black | 32 (5.1) | 1 (1.8) |

| Other | 18 (2.9) | 4 (7.3) |

| US Census region, No. (%) | ||

| West | 183 (28.7) | 11 (20.0) |

| Midwest | 164 (25.7) | 18 (32.7) |

| South | 169 (26.5) | 12 (21.8) |

| Northeast | 100 (14.9) | 9 (16.4) |

| Outside the US | 21 (3.1) | 5 (9.1) |

| Years since diagnosis, mean (SD) | 7.1 (6.5) | 6.5 (4.7) |

| Treatments received, No. (%) | ||

| Radical prostatectomy | 320 (50.1) | 27 (49.1) |

| Androgen deprivation therapy | 272 (42.6) | 24 (43.6) |

| External beam radiation therapy | 238 (37.3) | 12 (21.8) |

| Active surveillance | 92 (14.4) | 6 (10.9) |

| Focal therapy | 90 (14.1) | 7 (12.7) |

| Other systemic therapies | 132 (20.7) | 15 (27.3) |

| Other or no treatments | 98 (15.4) | 9 (16.4) |

| Caregiver type, No. (%) | ||

| Spouse/partner | 35 (63.6) | |

| Other family member | 8 (14.5) | |

| Friend | 10 (18.2) | |

This table presents demographic data of Survey 2 respondents

Most patient PSN members had localized prostate cancer (58.1%) compared with 16.1% with recurrent prostate cancer, and 24.4% with advanced prostate cancer. A plurality of caregivers cared for men with localized prostate cancer (46.8%). A large percentage of caregivers were associated with advanced prostate cancer patients (42.6%) with a smaller proportion of caregivers of men with recurrent prostate cancer (8.5%). The majority of caregivers were spouses or partners of men with prostate cancer.

Round 1 PSN participants ranked the seed questions in the first-round survey (Supplementary Table 1). Participants contributed 228 open text responses which were categorized into 119 comparative effectiveness research questions pertinent to localized prostate cancer, 109 questions pertinent to recurrent prostate cancer, and 116 research questions classified as relevant to advanced prostate cancer. These questions were thematically grouped into 119 unique questions and sorted by frequency of mentions by PSN participants. For the second-round survey, the top ranked questions from the first-round survey were combined with 5 open text responses for localized prostate cancer, 4 open text responses for recurrent prostate cancer, and 4 open text responses for advanced prostate cancer.

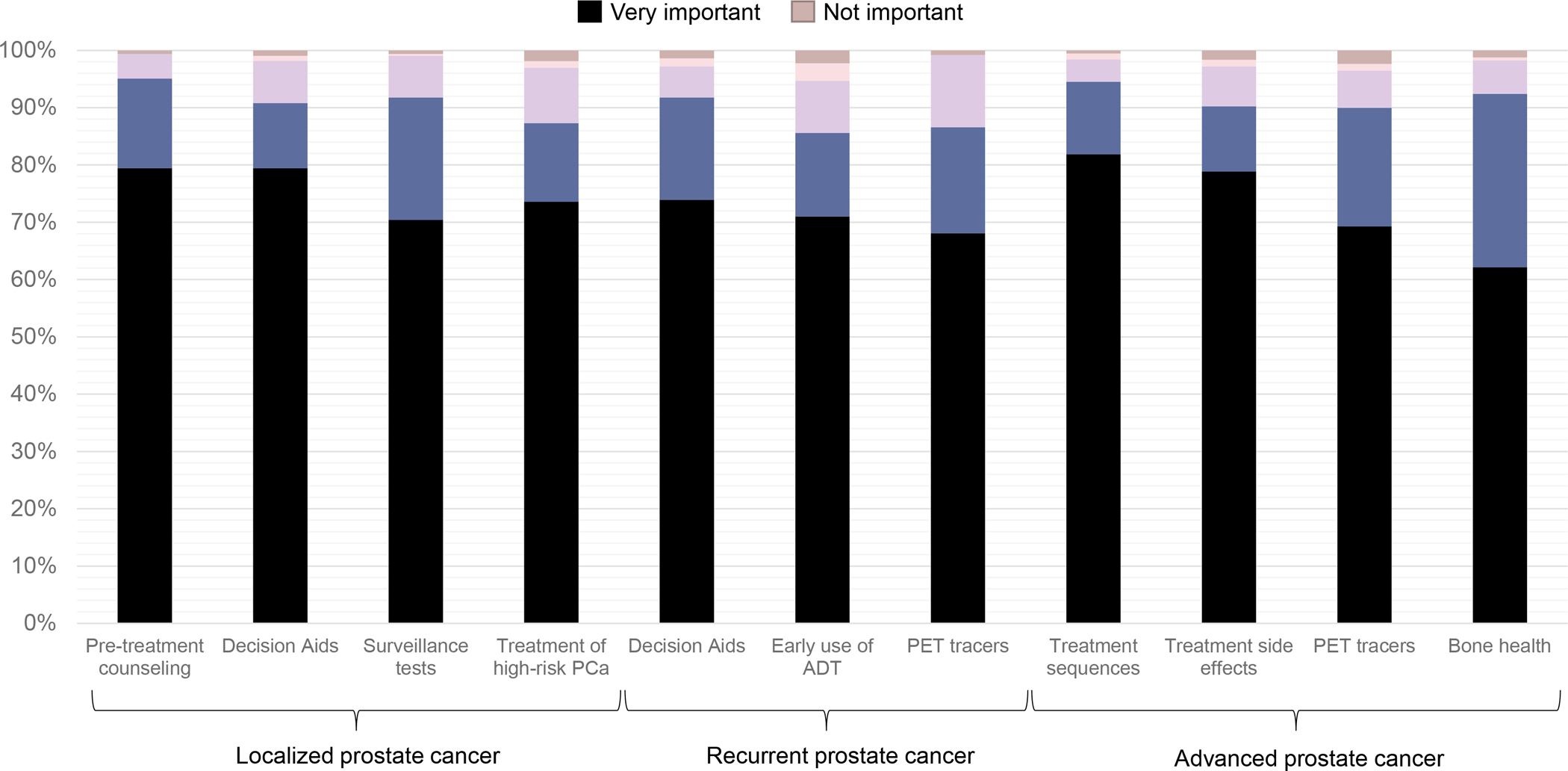

Table 2 presents the final prioritized research questions. No open text response question was ranked among the top comparative effectiveness research questions. Five of the top eleven research questions related to decision-making or survivorship care. The importance ratings of the top research questions are displayed in Figure 2. The research questions with the highest overall importance ratings were: (1) What is the comparative effectiveness of different strategies to improve counseling regarding the side effects of prostate cancer treatment?; (2) What is the comparative effectiveness of different tools for decision-making in localized prostate cancer?; and (3) What is the comparative effectiveness of different sequences of treatments for metastatic prostate cancer?

Table 2.

Final Prostate Cancer Patient Survey Network (PSN) comparative effectiveness research questions for localized, recurrent, and advanced prostate cancer.

| Localized Prostate Cancer | Recurrent Prostate Cancer | Advanced Prostate Cancer |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1. What is the comparative effectiveness of

different strategies to improve counseling regarding the side effects of

prostate cancer treatment? 2. What is the comparative effectiveness of different tools for decision-making in localized prostate cancer? 3. What is the comparative effectiveness of different schedules and tests for prostate cancer surveillance? 4. What is the comparative effectiveness of different treatments for high-risk prostate cancer? |

1. What is the comparative

effectiveness of different tools for decision-making in recurrent

prostate cancer? 2. What is the comparative effectiveness of early versus deferred androgen deprivation therapy in recurrent prostate cancer? 3. What is the comparative effectiveness of different PET tracers in detecting recurrent prostate cancer? |

1. What is the comparative effectiveness of

different sequences of treatments for metastatic prostate

cancer? 2. What is the comparative effectiveness of different systemic therapies with respect to QOL and side effects? 3. What is the comparative effectiveness of different PET tracers in detecting metastatic prostate cancer? 4. What is the comparative effectiveness of different strategies to preserve bone health in advanced prostate cancer? |

|

Additional PSN-derived

questions:a • What is the comparative effectiveness of different indications for treatment on active surveillance? • How does the comparative effectiveness of prostate cancer treatments vary by patient race/ethnicity? • What is the comparative effectiveness of strategies (pelvic PT, etc.) to expedite functional recovery (urinary and sexual) after treatment? • What is the comparative effectiveness of strategies to address penile shortening, anorgasmia, and climacturia? • How does the use of patient advocates or patient navigators impact patient health outcomes? |

Additional PSN-derived

questions:a • What is the comparative effectiveness of salvage prostatectomy compared with cryotherapy and other treatment options for recurrent prostate cancer? • What is the comparative effectiveness of risk tools that allow for individualized predictions of death from prostate cancer? • How does the use of patient advocates or patient navigators impact patient health outcomes? |

Additional PSN-derived

questions:a • What is the comparative effectiveness of medical marijuana and other complimentary therapies for managing the effects of treatment for advanced prostate cancer? • What is the comparative effectiveness of risk tools that allow for individualized predictions of death from prostate cancer? • How does the use of patient advocates or patient navigators impact patient health outcomes? |

PSN-derived comparative effectiveness research question from open text responses in the first-round survey.

Figure 2.

Importance ratings of the prioritized comparative effectiveness research questions in the Prostate Cancer Patient Survey Network (PCa: prostate cancer; ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; PET: positron-emission tomography)

DISCUSSION

We engaged prostate cancer patients and caregivers to develop and prioritize prostate cancer patient-centered comparative research questions. For localized prostate cancer, we found that survey respondents prioritized research questions that facilitated treatment decision-making, functional outcomes following treatment, and the intensity of surveillance. PSN priorities for recurrent prostate cancer focused on decision-making and predictive tools, the timing of androgen deprivation, the intensity of post-treatment surveillance, novel imaging studies, and supportive services. For advanced prostate cancer, we found that PSN members prioritized the comparative effectiveness of different systemic treatment sequences, novel imaging studies, quality of life and side effects of systemic therapies, naturopathic/complementary therapies, risk prediction tools, and the role of supportive services (i.e., palliative care and/or patient advocates/navigators) on survivorship. These research priorities highlight a wide range of patient priorities that largely focus on decision-making, quality of life, and survivorship care.

Patient engagement in the development and prioritization of research questions in prostate cancer can direct attention toward potentially more meaningful and inclusive research. The PSN-derived research questions were uniquely distinct from the questions embedded into the first-round survey by clinic, research, and patient advocate experts. The iterative process of patient engagement centers the patient voice in driving research from inception (i.e., the preparatory phase) through translation (i.e., execution/translational phase). This approach also compliments current patient-centered clinical strategies, which have demonstrated improvements in the quality-of-care patients receive.2

Patient-derived clinical questions have demonstrated success in affecting national research agendas and directing funding toward patient-centered clinical trials. In partnership with the Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network, Smith, et al.,5 derived a series of research priorities in the clinical categories of non-muscle-invasive, muscle-invasive, and metastatic bladder cancer. Two of the prioritized research questions for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer evaluating the comparative effectiveness of salvage intravesical therapies and the role of radical cystectomy in bladder cancer that fails intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) were selected as a funding priority for the PCORI Pragmatic Clinical Studies mechanism in 2017, which currently supports the CISTO Study (Comparison of Intravesical Therapy and Surgery as Treatment Options for Recurrent Bladder Cancer, NCT 03933826). Thus, there is precedent for translating these research priorities into interventional trials that aspire to improve patient care and affect outcomes that are important to patients.6

There are several limitations of this survey analysis that warrant discussion. First, we prioritized recruiting a cohort of Prostate Cancer PSN members enriched for Black men and their caregivers given the disproportionate burden of prostate cancer in this population.7 Despite our partnership with two national advocacy organizations, only 5% of participants in our survey identified as Black or African American. The lack of a representative sample of Black men and, more broadly, men of other races, limits the generalizability of our elicited research priorities; these priorities may not reflect the preferences and needs of non-White men and their support networks. To address this specific issue, we are focusing our engagement efforts on prostate cancer advocacy groups and community organizations (i.e., faith-based organizations) dedicated exclusively to Black men. Our goal is to represent the research priorities of all men with prostate cancer. Black men may have different interests and needs than the mostly white men included in the PSN.

Second, our survey may have employed language that was a barrier for men with lower health literacy. In our prior experience, we encountered challenges with orienting patients to how to construct comparative effectiveness research questions. We attempted to overcome this by rephrasing these questions with more accessible language. For example, rather than asking patients to rate the question, “what is the comparative effectiveness of different aids to support decision-making in localized prostate cancer,” we asked PSN members “how useful are the different tools designed to help people make decisions about treatment for prostate cancer that is restricted to the prostate?” However, despite iteration of the wording of these questions with our patient advocate partners, the survey may still have been inaccessible to men of lower health literacy. Lastly, there are several other considerations around social and health factors that may impact research priorities (i.e., age, health literacy, income, etc.) that could not be evaluated in stratified analyses due to our smaller sample size and lack of data. We acknowledge that future engagement activities around priorities should account for these factors in their design to ensure that research priorities are generalizable to the specific needs of sub-populations, especially those that are marginalized or high-risk

There are several strengths of this study, which include the size of the PSN and the use of community partners to drive this early phase of engagement and patient-centered research in prostate cancer. We used a mixed-methods approach for engagement that included surveys, clinical/research expert opinion, and patient/caregiver working groups. This was conducted in an iterative process as part of the preparatory phase of engagement with prostate cancer survivors that we expect will drive funding and research priorities hereafter. We repeated the two-round survey structure of the BCAN-PSN, which mimics the consensus-building processes of the Delphi method. The second round of the survey permits first-round respondents to view the rankings from all PSN members which may influence their perception of the importance of certain research questions. And the second-round allows for the incorporation of organically contributed questions from first round PSN participants which we thematically grouped, counted, and rewrote as comparative effectiveness research questions.

The research priorities derived from the Prostate Cancer PSN provide us with opportunity to address pressing clinical and survivorship-oriented issues among prostate cancer patients and their caregivers, which we intend to accomplish by widely disseminating these selected topics to research funders (i.e., National Cancer Institute, Department of Defense, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute). Given the changing therapeutic landscape of prostate cancer care, this research prioritization exercise will need to be repeated regularly. The low representation of Black men in our study highlights the importance of an engagement strategy that is unique to a patient population often disenfranchised from, and distrustful of, medical research. Our next series of engagement activities will focus on partnership, collaborative learning, and research prioritization with Black men and their advocates and caregivers.

CONCLUSION

We present a unique and patient-centered list of research priorities for localized, recurrent, and advanced prostate cancer developed through a series of stakeholder and patient engagement activities. These priorities demonstrate the importance of decision-making, quality of life, and survivorship care for prostate cancer survivors and caregivers. These research questions can inform funding decisions for organizations that support prostate cancer research. The process of designing and recruiting the Prostate Cancer PSN, similar to the BCAN PSN, can serve as a model for conducting the preparatory phase of patient engagement in cancer research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We are thankful for the prostate cancer patients and caregivers who selflessly shared their lived experiences through the various phases of this study. We are also thankful for the continued support and partnership of US TOO and NASPCC in all phases of this work.

Funding:

This work was supported in part by the following National Institutes of Health and Department of Defense awards: the Pacific Northwest Prostate Cancer SPORE (NCI P50CA097186), NIH/NCI P30 CA015704, and DOD W81XWH-17–2–0043.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No authors report relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.PCORI Engagement Rubric. PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) website. Published February 4, 2014. Accessed December 20, 2020. http://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf

- 2.Forsythe LP, Carman KL, Szydlowski V, et al. Patient Engagement In Research: Early Findings From The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(3):359–367. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mariotto AB, Enewold L, Zhao J, Zeruto CA, Yabroff KR. Medical Care Costs Associated with Cancer Survivorship in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(7):1304–1312. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith AB, Chisolm S, Deal A, et al. Patient-centered prioritization of bladder cancer research: Patient Engagement in Research. Cancer. 2018;124(15):3136–3144. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith AB, Lee JR, Lawrence SO, et al. Patient and public involvement in the design and conduct of a large, pragmatic observational trial to investigate recurrent, high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer. 2021. In press. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(3):211–233. doi: 10.3322/caac.21555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.