Abstract

The concepts of entrepreneurial bootstrapping and bricolage study identical problems; however, there exists a lack of integration between the two. Entrepreneurial bootstrapping and bricolage are resourcefulness behaviors that could potentially be critical dynamic capabilities that help firms accumulate, reconfigure and recombine resources to adapt to the dynamic and resource-constrained environment. This paper aims to focus on the missing integration of the two behaviors by investigating their convergence systematically using published literature. The study involves a bibliometric co-citation, bibliographic coupling, network, and Theory, Context, Characteristics, Methodology analysis to understand the existing literature more methodically to get a comprehensive picture of the behaviors. The results have provided more clarity on the conceptual convergence of these behaviors by analyzing their intellectual structures and research trends. The two entrepreneurial behaviors exhibit a mutual contribution to each other's literature, suggesting scholars to explore a probable integration of the two pieces of literature in future studies.

Keywords: Bootstrapping, Bricolage, Bibliometrics, Entrepreneurship, Co-citation, Bibliographic coupling

Introduction

Innumerable entrepreneurship and strategy scholars have discussed the precisely planned path entrepreneurs take to reach well-defined business goals (Shane and Venkataraman 2000). In reality, entrepreneurs’ scarcity of resources makes it difficult to follow these paths (Baker and Nelson 2005; Sarasvathy 2001). Despite the dynamic role of small firms in the economy (Audretsch 2002), most startups find it difficult to access or procure the resources required to gain a competitive advantage. However, scholars also note that such resource deficiencies often spur creativity in the enterprise and force the entrepreneur and their team to innovate to find solutions to resource constraints (An et al. 2018; Baker and Nelson 2005). Startups exist in environments characterized by not just resource constraints but also uncertainty and risk (Nelson and Lima 2020). One critical entrepreneurial skill is operating and surviving in these conditions by employing resourcefulness behaviors like entrepreneurial bootstrapping and bricolage. However, more scholarly research in entrepreneurship is needed to study these entrepreneurial behaviors adequately. For years, scholars have emphasized the significance of resources for a new venture (Hoang and Antoncic 2003) and acknowledged that access and arrangement of these resources are critical to the successful establishment of a new firm (Ebben and Johnson 2006). Therefore, it is crucial to study resource mobilization behaviors that help entrepreneurs discover and exploit business opportunities.

The two resourcefulness behaviors considered for this study are entrepreneurial bootstrapping and bricolage. Bootstrapping involves accumulating and acquiring business resources without using formal and traditional sources of finance (Rutherford et al. 2012). Bricolage refers to the extemporized approach of making do with whatever resources entrepreneurs have in hand (Baker et al. 2003). Section 2 explains the two concepts in detail. The concepts of entrepreneurial bootstrapping and bricolage study identical problems; however, their integration in literature seems missing or incomplete. Both entrepreneurial behaviors explain resourcefulness behaviors that are often informal and involve using resources in hand to overcome resource scarcity. While scholars compare bricolage with other related resource processes like effectuation, causation, and improvisation, its relationship with bootstrapping still needs more scholarly attention. The existing conceptualization of bricolage and bootstrapping presents avenues for research in synergy, as bricolage could be a strategic activity for entrepreneurs choosing to bootstrap, as both behaviors trigger actions that help entrepreneurs mobilize resources in unconventional ways without accessing resources from traditional sources. Even though the two behaviors are not entirely synonymous with each other, the strong connections between the two seem blurred in academic research (Rutherford et al. 2022). This lack of integration between the two kinds of literature could possibly lead to ignoring critical insights into the academic understanding of entrepreneurial resource management behaviors. Until this study, existing academic research has not adequately considered systematically studying the two resourcefulness behaviors, aiming to understand their unique similarities and differences. Therefore, research with a synergy of these entrepreneurial concepts presents a promising research gap.

The current study involves a bibliometric and TCCM analysis to help understand the existing literature more methodically to get a comprehensive picture of the behaviors (Grégoire and Cherchem 2020; Singh and Dhir 2019; Zupic and Čater 2015). This analysis will contribute to ascertaining the rational structures of both areas and understanding their complementarities and differences (Habib and Afzal 2019; Rey-Martí et al. 2016). Further, with the increase in the number of publications in both the literature, growing theoretical bases, and diverse methodologies, this bibliometric approach of studying the two behaviors together assists in understanding the evolution of both individually and in harmony. It also helps overcome the idiosyncrasies that might arise in reviewing a large number of works, given the capabilities and biases of a researcher subjectively reviewing them alone (Kessler 1963; Stefano et al. 2010; Verbeek et al. 2002; Vogel and Güttel 2013; Zupic and Čater 2015).

Overall, this study contributes to enhancing our understanding of the dynamics of resource management by entrepreneurs who operate in uncertain environments using flexible and informal approaches. It enhances our understanding of the missing integration and similarities in the two behaviors that could potentially be critical dynamic capabilities that help firms accumulate, reconfigure and recombine resources to adapt to the business environment. This study identified the intellectual structures and research trends of the two approaches using a systematic combined analysis of the two bodies of literature. The findings highlight that bootstrapping helps bolster the resource base, which is further made more flexible and innovative by the creative reinvention of resources using bricolage. Bricolage could also be a strategic action that is triggered when entrepreneurs decide to bootstrap their ventures strategically. These two behaviors complement each other as bootstrapping helps arrange for the finances, material resources, knowledge, and skills that are then creatively applied by the bricoleurs. Therefore, studying the two approaches together is interesting while considering their unique aspects (accumulation vs. deployment).

Conceptual background

Resource theories in management have emphasized the critical role of resources for venture survival and success (Barney 1991; Penrose 1996). Nevertheless, newer ventures find it difficult to access and avail business resources from conventional sources due to lack of credibility, liability of smallness and newness, information asymmetry, and innumerable risks involved (Freeman et al. 1983; Witt 2004). Some entrepreneurs also choose to voluntarily opt out of raising resources with external help (Winborg 2009). Regardless of the motivation (resource scarcity or strategic choice), resource management of entrepreneurial ventures in dynamic business environments without any explicit external help is a promising area of research. This paper focuses on two such resource mobilization behaviors—bootstrapping and bricolage.

The first area of research is entrepreneurial bootstrapping, which refers to using informal methods to meet resource needs without taking external funds as debt or diluting equity (Winborg and Landström 2001). It involves using creative means to acquire financial and non-financial business resources by spending little or no money. Scholars in this area have described it as innovative resource management which aims to minimize the cost of operations while also avoiding external influence on the venture board by investors (Ebben and Johnson 2006). This helps entrepreneurial ventures overcome their resource limitations while also being in complete control of the firms’ strategic decisions. Even without the explicit use of the term ‘bootstrapping’, informal ways of gathering resources like delaying payments, accelerating receivables, reinvesting cash flows, using personal savings, and exploiting social and professional networks have been used by entrepreneurs (Churchill and Thorne 1989). Bhide (1992) then introduced the term ‘bootstrapping’ to explain this innovative resource management method employed by entrepreneurs.

Academics in entrepreneurial research emphasize the unconventional methods used by startup founders to acquire business capital and resources while ensuring freedom of action for themselves in the functioning of their businesses (Grichnik et al. 2014; Winborg 2009). Entrepreneurial bootstrapping typically takes place in two forms- financial bootstrapping for acquiring financial funding from informal sources and resource bootstrapping for gathering all the business resources (non-financial) without taking any external help (Harrison et al. 2004). Scholars have also highlighted the completive advantages to a bootstrapped venture vis a vis other players as bootstrappers tend to work more efficiently with the limited resource base they own or can access (Harrison et al. 2004; Vanacker et al. 2011).

The second resource mobilization behavior considered for this study is entrepreneurial bricolage, which refers to making do by utilizing the existing resource base of the venture. It involves using already owned or easily and freely available resources for unconventional purposes (Baker and Nelson 2005). The concept of bricolage has its roots in anthropology, where Levi-Strauss (1967) introduced it to describe how the actions of an engineer and a bricoleur differ. It was then adapted in entrepreneurship research to explain how founders combine and recombine resources at hand to create new markets and grow (Baker et al. 2003; Baker and Nelson 2005).

Empirical research in this area suggests that resource reconstruction in the bricolage process helps such founders build a new product or market for their customers instead of finding a place for them in the existing markets and industries. These studies in bricolage have suggested that bricoleurs primarily show three specific characteristics. First, bricoleur entrepreneurs do not wait for their inputs, finances, and resources to be available at a covetable level, thereby having a definite bias towards taking action. Second, bricoleurs prefer to take full advantage of their social networks, resources, and skills. Finally, bricoleur entrepreneurs combine and recombine existing resources to come up with new solutions to their entrepreneurial challenges (Baker and Nelson 2005). According to their study, bricoleurs focus on finding a solution to their obstacles instead of wasting valuable time deliberating about the appropriateness of resources at hand. Resources at hand encompass any resources that are cheaply, freely, or easily accessible and available to an entrepreneur (human capital, raw material, know-how, and others). Table 1 explains the similarities and differences between the two resource-focused entrepreneurial behaviors.

Table 1.

Similarities and differences between entrepreneurial bricolage and bootstrapping

| Similarities | Entrepreneurial bricolage and bootstrapping | Selected References |

|---|---|---|

| Resource dependence | Focus on the critical role of resources for operations and survival of the business and generally prevalent in resource-scarce environments; resource-led innovation | Baker and Nelson (2005), Baker et al. (2003), Bhide (1992), Ebben (2009), Ebben and Johnson (2006), Fisher (2012), Grichnik et al. (2014), Welter et al. (2016) |

| Focus on action | Focus is on taking action to meet business goals by managing with the existing resources without any external help to take actions to control the uncertain environment | |

| Experimentation | Unconventional and innovative ways of experimenting with the resources available; "do-it-yourself" approaches | |

| Networks and communities | Critical role of the entrepreneurs' social capital and network to access resources and test products | |

| Dependence on entrepreneur (action-taker) | Entrepreneur (human capital, social capital, and behavior patterns) is at the center of resource management decision-making in order to exploit business opportunities |

| Differences | Entrepreneurial bricolage | Entrepreneurial bootstrapping | Selected references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus | To bolster the ventures' limited resource base without external funds or resources | To redefine the use of resources at hand by opting for alternative practices and combinations of existing resources | Archer et al. (2009), Baker and Nelson (2005), Bhide (1992), Fisher (2012), Grichnik et al. (2014), Löfqvist (2017), Vanacker et al. (2011), Welter et al. (2016), Winborg (2009) |

| Resources and uncertainty | Generally, in case critical resources required for business operations are not available to the business | Generally, resource scarcity forces entrepreneurs to bootstrap; could also be a voluntary and strategic activity | |

| Expertise and experience of entrepreneurs | Generally, both nascent and experienced entrepreneurs engage in bricolage | Entrepreneurs with more managerial experience tend to be better at bootstrapping their businesses | |

| Opportunity exploitation and resources | Focus is not exactly on exploitation of opportunities but on using resources available at hand | Focus is on exploiting opportunities despite no external funding |

Another related concept of resource management is effectuation, introduced by Sarasvathy (2001). This behavior highlights that in uncertain business environments, entrepreneurs change their focus from the end goals to the means they control. These could be individual characteristics like the entrepreneur’s professional or personal network, knowledge, and skills, or could be the venture’s means like its physical, organizational, or human resources. The focus here is to take action by exploiting the existing means, thereby allowing goals to form during this process of exploration (March 1991). The idea is to identify and exploit opportunities with the given means. Just like entrepreneurial bricolage and bootstrapping, the entrepreneurs’ attention here is on critical resource exploitation by taking action, given the uncertainties of dynamic and resource-constrained business environments. However, unlike bricolage which both new and serial entrepreneurs can undertake, effectuation is more often practiced by experienced entrepreneurs who resort to means-driven actions. Entrepreneurs who apply effectual behavior focus on affordable loss instead of the returns they expect at the end while also focusing on their relationships and partnerships instead of competition. They focus on exploiting contingencies to reach newer outcomes instead of an already set goal (Fisher 2012).

Most of the prominent theories in entrepreneurship suggest that entrepreneurs, who can recognize and capitalize on opportunities supported by a clear long-term vision and predetermined goals, and well-defined plans and strategies while having access to the best resources and talent, are the ones who are able to succeed in this competitive business environment (Shane and Venkataraman 2000; Wiklund and Shepherd 2005). However, recent studies suggest that ventures can sail through in these dynamic ecosystems without having access to all of the aforementioned advantages. Therefore, it is crucial to study behaviors like bootstrapping and bricolage which contribute to the evolution as well as the development of dynamic capabilities of a firm. Such behaviors increase the flexibility of ventures while also honing their abilities to look for alternative resource uses and use recombination of accessible resources to create value for the business.

Method

Bibliometric analysis is a systematic statistical method for analyzing academic research publications (Donthu et al. 2021; Zupic and Čater 2015). It highlights frontiers within research areas to understand their overview, gaps, trends, networks, knowledge producers, and themes (Donthu et al. 2021; Rey-Martí et al. 2016; Zupic and Čater 2015). Compared to traditional literature reviews, bibliometric analysis enables analyzing large quantities of academic and scholarly research data, which is easily accessible due to new technology tools (Hood and Wilson 2001; Merigó et al. 2015). The study also involves a systematic review of bootstrapping and bricolage literature following the TCCM approach (Paul and Rosado-Serrano 2019; Singh and Dhir 2019). This simple but comprehensive framework involves a detailed review of literature by focussing on theory development (T), context (C), characteristics (C), and methodology (M) employed. Citation analysis of bibliometrics helped identify the most cited works in both the literature, which was followed by their content analysis as suggested by Paul and Rosado-Serrano (2019), taking guidance from Keupp and Gassmann (2009), Nicholls-Nixon et al. (2011) and Terjesen et al. (2016). This analysis helped identify the gaps in the existing literature to propose new directions for future research.

Data collection and sampling

The data was collected from the Scopus database, covering a broad range of literature from peer-reviewed journals (“Appendix 1”). For searching relevant literature, the keywords used were “bricolage*”, and “bootstrap*”. The keywords “entrepreneur*”, “startup”, “start-up”, “founder” were also used while searching to ensure filtering out papers that were not directly related to the entrepreneurship literature. The literature was collected for a 30-year period from 1991 to mid-2021 from the Business and Management areas. The search also examined other related areas like psychology and sociology. The first refined search resulted in 565 documents. To reduce the bias in selecting the final studies for this analysis, refining for done to the final sample (Zupic and Čater 2015) to include studies related to entrepreneurial bootstrapping and bricolage, which are a part of the business entrepreneurship literature. For inclusion, the papers were required to discuss the resource management of entrepreneurs or be closely related theoretical concepts along with bootstrapping and bricolage. This refining also helped remove the documents that contained bootstrapping procedures of the PLS-SEM methodology. The final sample excluded papers that did not directly relate to business management, entrepreneurship, strategic resource management, and innovation themes. A similar search in the Web of Science database showed a 93% overlap with the Scopus sample.

Another scholar helped validate the final sample by independently reading the basic details of all the documents chosen, removing papers that did not appear suitable for the analysis by consensus. It included papers that did not necessarily pertain to entrepreneurship or business management literature. The Cohen-Kappa (1960) coefficient was 0.86 for agreement on the documents included in the final sample. The measure was significant at p = 0.01. As per the guidelines by Landis and Koch (1977), a significant kappa statistic of over 0.81 shows an almost perfect agreement between the two raters. In case of disagreements, the papers were discussed with fellow researcher to decide whether to include them in the sample. A final sample of 239 papers, including 167 papers in the bricolage literature and 72 papers in the bootstrapping literature, were considered.

Since research in any scientific field is not conducted in isolation but by a community of people, it is imperative to understand literature from a temporal dimension, as the development and maturity of a scientific discipline involve incremental efforts as it progresses in leaps through different paradigms (Kuhn, 1962). This approach helped analyze the knowledge base of bootstrapping and bricolage literature. Apart from the seminal works explaining the concept, bootstrapping literature consists of multi-disciplinary works on different aspects of entrepreneurial bootstrapping like motives behind opting for it, stages of business development, women entrepreneurship and gender differences, business environment, human and social capital, firm performance and growth, technology orientation as well as the strategic role of the entrepreneur. Similarly, for the bricolage literature, multi-disciplinary works discuss resource constraints, institutional voids, social entrepreneurship, related concepts like effectuation and causation, technical entrepreneurship, intrapreneurship, and impact on firm performance. More recently, scholars have also studied the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurial resourcefulness behaviors.

Analysis procedures

The first bibliometric analysis procedure applied was co-citation analysis, a commonly used bibliometric procedure that measures how frequently two articles are cited together in the sample (Hjørland 2013; McCain 1990). This helps identify and understand the thematic clusters of the most cited publications (Donthu et al. 2021). Co-citation analysis measures the proximity between works on the sample, assuming that works related in terms of their concepts get cited together (Zupic and Čater 2015). Therefore, the co-citation analysis will help identify the intellectual structure of the bootstrapping and bricolage literature (Rossetto et al. 2018). To make the co-citation results more meaningful, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), one of the most commonly employed clustering methods in a co-citation bibliometric analysis, was performed (McCain 1990; Zupic and Čater 2015).

For performing the EFA, the co-citation matrix, extracted from Bibexcel (Persson et al. 2009) software, was further converted to a Pearson’s coefficient correlation matrix. The SPSS software helped identify factors by applying the principal component method and scree tests with Varimax rotation and Kaiser normalization (Kaiser 1960; Lin and Cheng 2010; Watkins 2018). This ensured the maximum number of works load to minimum identified factors (Pilkington and Liston-Heyes 1999). The works with a factor loading over 0.4 were considered important for the analysis (Hair et al. 2010; Peterson 2000; Zhao 2006). Exploratory factor analysis is the most suitable method in such a study because it enables loading the cited works to more than one factor, which implies the contributions of these works across different factors and literature (Zupic and Čater 2015). Thus, works loaded to multiple factors were assigned to the factor with the highest loading while also analyzing its role in the other factors (Vogel and Güttel 2013). Works with a factor loading of more than 0.7 are considered the most critical works for the respective factor (McCain 1990; Zupic and Čater 2015). The number of articles considered for co-citation analysis was reduced to 71 most cited works after cleaning the raw data for duplicates (like multiple entries of the same paper in Scopus) from the top cited articles. Bibexcel software assisted in extracting co-citation data. This follows Lotka’s law which states that a smaller proportion of highly cited articles can represent an area of research (Nath and Jackson 1991). A network analysis then helped to increase the robustness of the co-citation analysis (Vogel and Güttel 2013) by using the NETDRAW, UCINET (Borgatti et al. 2002) software, and the co-citation matrix. Network analysis will help visualize the intellectual structure of the literature. The nodes in the network diagram represent the works or the publications, with the ties depicting their proximity.

The next analysis of the bibliometric study is a bibliographic coupling that assumes that works that refer to the same literature are similar in their content and themes (Kessler 1963). This helps to identify similarities in works by considering the overlapping publications referred to in the papers (Vogel and Güttel 2013; Zupic and Čater 2015). A bibliographic coupling analysis assists in establishing the research front and themes in the studied literature (Baker et al. 2021; Vasconcelos Scazziota et al. 2020). While co-citation analysis focuses on how two documents get cited together, a bibliographic coupling analysis focuses on the publications cited in the sample (Donthu et al. 2021). It helps understand how similar works are by analyzing how frequently studies in the selected sample have a common reference.

A co-occurrence matrix was extracted from Bibexcel software to analyze which pairs of documents share the same references for performing the bibliographic coupling analysis. This analysis follows the same process used for co-citation, network analysis, and clustering. Documents with more than five couplings were used for the analysis, thus reducing the number of cited documents in the bibliographic coupling matrix to 58. This helped manage the data better by reducing documents with lesser couplings while also increasing the robustness of the analysis by using references of higher intensity (Vasconcelos Scazziota et al. 2020). As in the co-citation analysis, this analysis generates a network diagram for bibliographic coupling using the same parameters as the co-citation analysis.

A detailed analysis of the works that fall into each cluster for co-citation and bibliographic coupling analysis helped label the different clusters, following a structured reading of the studies in each factor (Vogel and Güttel 2013). This process followed the guidelines from the work of Denyer and Tranfield (2009) for this review. The cross-loadings in the factors analysis help understand the conceptual convergence and overlaps in the two pieces of literature. If an article has a factor loading over 0.40 in not just one but two factors, it implies that it conceptually adds to the literature of the other factor. For instance, as in Table 2, the work of Desa (2012) is a part of factor 1 (0.568 factor loading), but it also contributes to factor 2 and factor 3 as it has a factor loading of greater than 0.4 for those two factors as well.

Table 2.

Co-citation analysis factor loadings

| Paper authors | Year | Highest factor loading | Co-citation factors | Paper authors | Year | Highest factor loading | Co-citation factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooper, Gimeno-Gascon and Woo | 1994 | CC1-0.941 | CC1 | Wernerfelt | 1984 | CC2-0.675 | CC2, CC1,CC3 |

| Cassar | 2004 | CC1-0.852 | CC1 | Barney | 1991 | CC2-0.663 | CC2, CC1,CC3 |

| Bhide | 1992 | CC1-0.838 | CC1 | Ciborra | 1996 | CC2-0.65 | CC2, CC1 |

| Berger and Udell | 1998 | CC1-0.829 | CC1 | Short, Moss and Limpkin | 2009 | CC2-0.643 | CC2, CC1 |

| Adler and Kwon | 2002 | CC1-0.821 | CC1 | Desa and Koch | 2014 | CC2-0.64 | CC2, CC1,CC3 |

| Harrison, Mason and Girling | 2004 | CC1-0.805 | CC1 | Linna | 2013 | CC2-0.629 | CC2, CC1,CC3 |

| Winborg and Landstrom | 2001 | CC1-0.803 | CC1, CC2 | Zahra et al | 2008 | CC2-0.624 | CC2, CC1 |

| Grichnik et al | 2014 | CC1-0.775 | CC1, CC2 | Jacob | 1977 | CC2-0.614 | CC2, CC1,CC3 |

| Ebben and Johnson | 2006 | CC1-0.774 | CC1, CC2 | Mair and Marti | 2009 | CC2-0.596 | CC2, CC1,CC3 |

| Baker and Nelson | 2005 | CC1-0.773 | CC1 | Sirmon, Hitt and Ireland | 2007 | CC2-0.567 | CC2, CC1,CC3 |

| Baker | 2007 | CC1-0.766 | CC1 | Garud and Karnøe | 2003 | CC2-0.565 | CC2,CC1,CC3,CC4 |

| Jones and Jayawarna | 2010 | CC1-0.755 | CC1, CC2 | Levi Strauss | 1966 | CC2-0.564 | CC2,CC1,CC3,CC4 |

| Van Auken | 2005 | CC1-0.749 | CC1 | Fisher | 2012 | CC2-0.535 | CC2,CC1,CC3,CC4 |

| Winborg | 2009 | CC1-0.745 | CC1, CC2 | Shane and Venkataraman | 2000 | CC2-0.532 | CC2,CC1,CC3,CC4 |

| Baker, Miner and Eesley | 2003 | CC1-0.682 | CC1, CC2, CC3 | Sarasvathy | 2001 | CC2-0.529 | CC2,CC1,CC3,CC4 |

| Wu, Liu, Zhang | 2017 | CC1-0.657 | CC1, CC3 | Alvarez and Busenitz | 2001 | CC3-0.781 | CC3 |

| Ferneley and Bell | 2006 | CC1-0.629 | CC1, CC2, CC3 | Hambrick and Mason | 1984 | CC3-0.734 | CC3, CC1 |

| Zahra | 2009 | CC1-0.617 | CC1, CC2, CC3 | Lumpkin and Dess | 1996 | CC3-0.7 | CC3, CC4 |

| Halme, Lindeman and Linna | 2012 | CC1-0.585 | CC1, CC2, CC3 | Salunke, Weerawardena, Mccoll-Kennedy | 2013 | CC3-0.624 | CC3, CC1,CC2 |

| Miner, Bassof and Moorman | 2001 | CC1-0.575 | CC1, CC2, CC4 | Bechky and Okhuysen | 2011 | CC3-0.6 | CC3, CC1,CC2 |

| Di Domenico, Haugh and Tracey | 2010 | CC1-0.57 | CC1, CC2, CC3 | Senyard, Baker and Davidsson | 2009 | CC3-0.599 | CC3,CC1,CC4 |

| Duymedjian and Rüling | 2010 | CC1-0.57 | CC1, CC2, CC3 | Davidsson, Baker and Senyard | 2017 | CC3-0.591 | CC3, CC1,CC2 |

| Desa | 2012 | CC1-0.568 | CC1, CC2, CC3 | Hoang and Antoncic | 2003 | CC4-0.857 | CC4 |

| Phillips and Tracey | 2007 | CC1-0.567 | CC1, CC2,CC3,CC4 | Granovetter | 1985 | CC4-0.811 | CC4 |

| Desa and Basu | 2013 | CC1-0.564 | CC1, CC2, CC3 | Alvarez and Barney | 2007 | CC4-0.701 | CC4,CC1,CC3 |

| Mair and Marti | 2009 | CC1-0.549 | CC1, CC2, CC3 | Perry, Chandler and Markova | 2012 | CC4-0.699 | CC4,CC3 |

| Senyard et al. | 2014 | CC1-0.549 | CC1, CC2, CC3 | Read, Song and Smit | 2009 | CC4-0.695 | CC4,CC1,CC3 |

| Stinchfield, Nelson and Wood | 2013 | CC1-0.538 | CC1, CC2,CC3,CC4 | Mcmullen and Shepherd | 2006 | CC4-0.666 | CC4,CC3 |

| Meyer and Rowan | 1977 | CC2-0.81 | CC2, CC4 | Berends et al | 2014 | CC4-0.567 | CC4,CC1,CC3 |

| Seelos and Mair | 2005 | CC2-0.701 | CC2, CC1 | Welter, Mauer and Wuebker | 2016 | CC4-0.55 | CC4,CC1,CC3 |

| Weick | 1993 | CC2-0.677 | CC2, CC1 | Shane | 2000 | CC4-0.546 | CC4,CC1,CC2,CC3 |

Co-citation factors column consists of factors that studies are loaded to (> 0.4 factor loading), the first one depicting the highest factor loading

% of Variance Explained: CC1: 33.2%; CC2: 24.9%; CC3: 21.5%; CC4: 15.5%; % of Variance Accumulated: 95.1%

Results

Co-citation analysis: understanding the intellectual structure

The first analysis procedure applied was co-citation analysis. The factor analysis identified four factors that explain 95% of the variation. Table 2 details the co-citation factors along with the factor loadings. The factor loading analysis process included the exclusion of multiple seminal works dealing with the basics of case study analysis, theory building, statistical methodologies, and qualitative data biases from the articles analyzed for co-citation as they do not contribute directly to the bootstrapping and bricolage literature.

The first factor was labeled entrepreneurial resourcefulness (CC1). The works in this factor primarily discuss small business resourcing behaviors (Cassar 2004; Berger and Udell 1998). The works in bootstrapping consist of seminal work explaining the concept of bootstrapping, the motives behind bootstrapping, changes in this behavior over time, the role of social and human capital, and the impact of bootstrapping on product development and firm performance (Cooper et al. 1994; Ebben and Johnson 2006; Grichnik et al. 2014; Harrison et al. 2004; Jones and Jayawarna 2010; van Auken 2005; Winborg 2009; Winborg and Landström 2001). The bricolage works consist of documents explaining resource recombination and making do with what is in hand (Baker 2007; Baker and Nelson 2005). Here, the factor loadings highlight works in bricolage and their impact on firm performance and innovation (Duymedjian and Rüling 2010; Ferneley and Bell 2006; Miner et al. 2001; Senyard et al. 2014; Stinchfield et al. 2013; Wu et al. 2017). An overlap can be noted here with the other three factors as authors discuss resourcefulness behaviors in social entrepreneurship, impact on entrepreneurial orientation, and subsequent performance (Desa and Koch 2014; Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Seelos and Mair 2005; Senyard et al. 2009; Short et al. 2009). Multiple studies loaded to the other three factors have a contribution to factor CC1 as well (greater than 0.4-factor loading). An overlap between the two pieces of literature is present in this factor as the papers analyzed are cited in works from both behaviors with a focus on getting maximum value out of the resources already owned or easily accessible.

The second factor was labeled resourcing social entrepreneurship (CC2), as it primarily consisted of works that discuss how bricolage and bootstrapping are in the case of a social enterprise (Desa and Koch 2014; Mair and Marti 2009; Seelos and Mair 2005; Short et al. 2009; Zahra et al. 2009). Some of the works here also highlight the role of organizational structure and resilience while discussing how ventures display innovative resourcefulness behaviors to survive in a dynamic resource-deficient environment (Jacob 1977; Linna 2013; Meyer and Rowan 1977; Sirmon et al. 2007; Weick 1993). This factor consists of factor loadings of some classic resource theory work like that of Wernerfelt (1984) and Barney (1991), along with the anthropology paper on bricolage (Honigmann and Levi-Strauss 1967). Further, this factor consists of academic literature on similar behaviors like effectuation, causation, and tinkering (Fisher 2012; Jacob 1977; Sarasvathy 2001). This factor also consists of works that overlap between the two pieces of literature. The works cited by both bricolage and bootstrapping behaviors discuss how social entrepreneurs frequently face resource shortages and resort to innovative ways of resource use by seeking help from their networks to improve firm performance. Factor CC2 also has contributions from works that primarily load to the other three factors.

The third factor was labeled entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance (CC3). It consists of works that discuss how an organization’s resource management reflects its founders and team members (Hambrick and Mason 1984) and how multidimensional entrepreneurial orientation impacts firm performance (Lumpkin and Dess 1996). The works extend the resource-based theory by considering entrepreneurial cognition and the ability to combine resources as a critical component of a firm’s resource management and performance (Alvarez and Busenitz 2001; Senyard et al. 2009). Moreover, it discusses how businesses strategically combine resources to gain a sustained competitive advantage (Salunke et al. 2013). The works loaded on this factor are also cited in both works of literature. Studies loaded to other factors also contribute to factor CC3, as seen in Table 2.

The final factor was labeled social networks and decision-making (CC4). This consisted of works highlighting how business behaviors and decision-making depend on social networks (Granovetter 1985; Hoang and Antoncic 2003). The need to highlight and study the critical role of entrepreneurial action in these related concepts like bricolage, bootstrapping, and effectuation helps to understand these creative aspects of entrepreneurial behavior better (Berends et al. 2014; Perry et al. 2012; Read et al. 2009; Welter et al. 2016). Additionally, it discusses the role of entrepreneurial action and prior knowledge in the opportunity discovery process (Alvarez and Barney 2007; Shane 2000). This factor also consists of works that overlap between the two pieces of literature, as the studies cited by both these behaviors emphasize the importance of sharing resources with their networks for innovatively mobilizing scarce resources. Factor CC4 also has contributions from factors that primarily load to other co-citation factors.

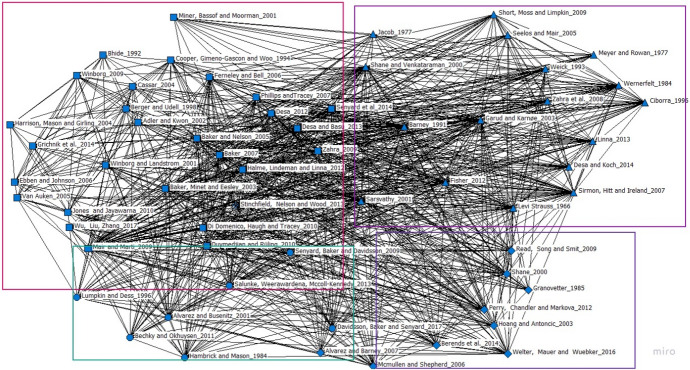

Next, a network analysis helped to increase the robustness of the co-citation analysis. Figure 1 shows the co-citation network, which helped visualize the intellectual structure of the literature. The nodes in the network diagram represent the works or the publications, with the ties depicting their proximity. As in other multidimensional scaling methods, this network layout aims to optimize the node distance. So, in the figure, the path length or the number of edges between two nodes helps measure centrality in the network (Vogel and Güttel 2013). The boxes help to identify the four factors of co-citation analysis. The line thickness connecting the two nodes represents how frequently those documents are co-cited. Since the works loaded on one factor are also connected with the references of the other factors, this network analysis helps understand this overlap, as shown in Fig. 1. This helps understand the relationship between them not just as a network diagram but also by assisting in analyzing their density. Therefore, network analysis enables more than just visualization (Pilkington and Chai 2008; Vogel and Güttel 2013). The density was analyzed to understand how different a factor or subgroup is from the network (Table 3). The density is the ratio of the number of realized ties to all the possible links or ties within the subgroup (Vasconcelos Scazziota et al. 2020; Vogel and Güttel 2013). It represents the extent to which a particular subgroup has a common base. While all factors are dense, CC2 and CC3 have higher densities.

Fig. 1.

Co-citation network

Table 3.

Network Analysis Metrics for Co-citation

| Factor | Symbol in Fig. 1 | Nodes | Density | Variance explained % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC1 | Square | 28 | 0.50 | 33.2 |

| CC2 | Up Triangle | 18 | 0.81 | 24.9 |

| CC3 | Circle | 7 | 0.67 | 21.5 |

| CC4 | Diamond | 9 | 0.56 | 15.5 |

Bibliographic coupling: understanding the research front

The next analysis was a bibliographic coupling. This analysis considered works with more than five couplings. The factor analysis of the bibliographic coupling matrix identified five factors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bibliographic coupling analysis factor loadings

| Paper authors | Year | Highest factor loading | Bibliographic coupling factors | Paper authors | Year | Highest factor loading | Bibliographic coupling factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An et al. | 2020 | BC1-0.915 | BC1 | Weerakoon, Gales and McMurray | 2019 | BC1-0.915 | BC1 |

| An et al. | 2018 | BC1-0.912 | BC1 | Wierenga | 2019 | BC1-0.887 | BC1 |

| An et al. | 2018 | BC1-0.912 | BC1 | Witell et al | 2017 | BC1-0.906 | BC1 |

| Bacq et al. | 2015 | BC1-0.901 | BC1 | Wu, Liu and Zhang | 2017 | BC1-0.89 | BC1 |

| Bellavitis et al. | 2017 | BC1-0.585 | BC1,BC3 | Yachin | 2017 | BC1-0.886 | BC1 |

| Bojica, Istanbouli and Fuentes-Fuente | 2014 | BC1-0.694 | BC1,BC4 | Yu et al | 2019 | BC1-0.887 | BC1 |

| Bojica et al | 2017 | BC1-0.829 | BC1 | Yu et al | 2020 | BC1-0.894 | BC1 |

| Brown, Mawson and Rowe | 2019 | BC1-0.916 | BC1 | Zhao et al | 2021 | BC1-0.9 | BC1 |

| Cheung et al. | 2019 | BC1-0.913 | BC1 | Horváth | 2019 | BC2-0.956 | BC2 |

| Davidsson, Baker and Senyard | 2017 | BC1-0.889 | BC1 | Weigand and Schulte | 2020 | BC2-0.95 | BC2 |

| Desa and Basu | 2013 | BC1-0.895 | BC1 | Al Issa | 2021 | BC2-0.916 | BC2 |

| Hooi et al. | 2016 | BC1-0.902 | BC1 | Block, Fisch and Hirschmann | 2021 | BC2-0.769 | BC2 |

| Hota, Mitra and Qureshi | 2019 | BC1-0.908 | BC1 | Waleczek et al | 2018 | BC2-0.751 | BC2,BC1 |

| Jannsen, Fayolle and Wuilaume | 2018 | BC1-0.913 | BC1 | Jayawarna, Jones and Marlow | 2015 | BC3-0.979 | BC3 |

| Korsgaard, Müller and Welter | 2021 | BC1-0.824 | BC1 | Jones and Jayawarna | 2010 | BC3-0.873 | BC3 |

| Ladstaetter, Plank and Hemetsberger | 2018 | BC1-0.912 | BC1 | Jayawarna, Jones and Macpherson | 2014 | BC3-0.852 | BC3 |

| Olive-Tomas and Harmeling | 2020 | BC1-0.9 | BC1 | Vanacker et al | 2011 | BC3-0.687 | BC3, BC5 |

| Salunke, Weerawardena and McColl-Kennedy | 2013 | BC1-0.873 | BC1 | Moghaddam et al | 2017 | BC3-0.568 | BC3 |

| Sarkar | 2018 | BC1-0.918 | BC1 | Hsiao, Ou and Chen | 2014 | BC4-0.87 | BC4 |

| Schulte-Holthaus | 2018 | BC1-0.912 | BC1 | Ritvala, Salmi and Andersson | 2014 | BC4-0.856 | BC4 |

| Servantie and Rispal | 2018 | BC1-0.92 | BC1 | Beckett | 2016 | BC4-0.528 | BC4 |

| Sivathanu and Pillai | 2019 | BC1-0.911 | BC1 | Beckett | 2016 | BC4-0.528 | BC4 |

| Tasavori, Kwong and Pruthi | 2017 | BC1-0.911 | BC1 | Neely and Van Auken | 2010 | BC5-0.8 | BC5 |

| Tindiwensi et al. | 2020 | BC1-0.809 | BC1 | Neely and Van Auken | 2009 | BC5-0.776 | BC5 |

| Tsilika et al. | 2020 | BC1-0.91 | BC1 | Malmström | 2014 | BC5-0.647 | BC5,BC3 |

| Scazziota et al. | 2020 | BC1-0.901 | BC1 | Franquesa and Brandyberry | 2009 | BC5-0.412 | BC5 |

Bibliographic Coupling factors column consists of factors that studies are loaded to (> 0.4 factor loading), the first one depicting the highest factor loading

% of Variance Explained: BC1: 50.7%; BC2: 9.4%; BC3: 9.4%; BC4: 6.3%; BC5: 6.3%; % of Variance Accumulated: 82.3%

The first factor was labeled resource mobilization in constrained environments (BC1), as it primarily consists of works that discuss how entrepreneurs overcome the challenge of gathering resources that they might not have easy access to (Korsgaard et al. 2021; Wierenga 2020). Some of these works discuss how it is even more difficult for enterprises, especially social ventures, to operate in emerging economies (Cheung et al. 2019; Hota et al. 2019). Academicians also highlight the role of entrepreneurial bricolage in agricultural farming and creative industries (Schulte-Holthaus 2018; Tindiwensi et al. 2021). Others discuss how firms create value through their decision-making logic and resource mobilization while employing resourcefulness behaviors to improve their creativity and innovation performance (An et al. 2018, 2020).

The second factor was labeled venture performance and growth (BC2), which consists of studies that analyze the role of bootstrapping on venture performance. Studies reveal that a firm's financial performance depends on its founders’ business goals and priorities between freedom and maximizing wealth. Findings indicate that the need for capital is driven more by demand instead of supply (Weigand and Schulte 2020). Further, other works highlight a positive relationship between the use of bootstrapping and the venture’s financial performance when moderated with strategic improvisation (Al Issa 2020). Scholars have found that the COVID-19 pandemic has also positively affected bootstrapping, helping ventures manage their liquidity and stay afloat (Block et al. 2021). Further, research also finds that bootstrapping is positively associated with employment growth when positively moderated by the training of entrepreneurs (Horváth 2019). Finally, due to its positive impact on venture performance and growth, bootstrapping is a strategic push driven by the founder(s) and not just a last resort (Waleczek et al. 2018).

The third factor was labeled resourcing through networks (BC3), as it consists of works that analyze the effect of social networks on bootstrapping activities. While bootstrapping has been favorable for most new ventures, studies have found gender differences in utilizing social networks to access resources (Jayawarna et al. 2015). Another study confirms that social networks influence venture sales, growth, and profits, mediated by bootstrapping activities (Jones and Jayawarna 2010). A study highlights that entrepreneurs who have support from their family networks from a young age are better at shaping entrepreneurial ambitions into results (Jayawarna et al. 2011). Contrary to these outcomes, some scholars also highlight that using networks to arrange resources might lead to uncertain outcomes due to a lack of formal arrangement (Vanacker et al. 2011). However, immigrant entrepreneurs prefer a single or few strong network sources over multiple weak sources (Moghaddam et al. 2017).

The fourth factor was labeled resource-led innovation (BC4). The works here discuss how entrepreneurs can innovatively use resources deemed worthless by ventures. Scholars highlight resource transformation, leveraging, and exchange that assists bricoleurs in employing frugal resource combinations (Hsiao et al. 2014). The existing literature has also commented on using bricolage for large companies that might be better off by focusing on more entrepreneurial and pragmatic incremental changes instead of big radical innovations. Moreover, even players in the food industry use entrepreneurial bricolage to innovate based on decision systems to respond and act, focus on iterative learning, and creatively combine resources at hand. (Beckett 2016).

The final factor is labeled slack and strategy (BC5). The works in this cluster highlight strategic and creative resource mobilization. Scholars have recognized three strategic bootstrappers—quick-fix bootstrappers, proactive bootstrappers, and efficient bootstrappers—who adopt strategies like using temporary resources, focusing on operational issues, and even focusing on external activities present in their value chain (Malmström 2014). Scholars find that small firms apply resource invocation using slack resources very differently from larger organizations (Franquesa and Brandyberry 2009). Scholars have noted that factors like founder education, age, and gender impact their strategies to gather resources and funds for their ventures (Neeley and Auken 2009). Another study points out that female business owners are more affected by metrics like firm performance, revenues, and overdraft privileges, due to the inherent gender bias present in capital availability. They tend to strategically improve their revenue-based cash flows that can be re-invested in their businesses (Neeley and van Auken 2010).

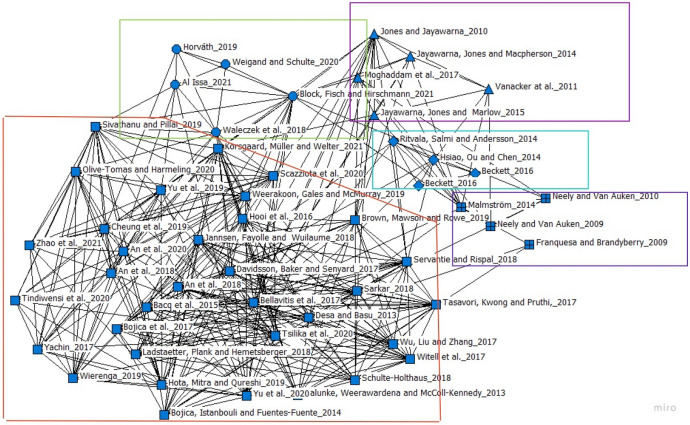

Figure 2 shows the network diagram of the bibliographic coupling analysis. It is analyzed as explained in Sect. 4.1. Clusters of bootstrapping papers can be seen on the right side of the network diagram, and we can note a cluster of bricolage literature at the bottom. Table 5 describes the results of the density analysis. The density values of most clusters depict that the factors are very dense (some factors have near-perfect density).

Fig. 2.

Bibliographic coupling network

Table 5.

Network analysis metrics for bibliographic coupling

| Factor | Symbol in Fig. 2 | Nodes | Density | Variance explained % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC1 | Square | 35 | 0.45 | 50.78 |

| BC2 | Circle | 5 | 1.00 | 9.44 |

| BC3 | Up Triangle | 5 | 0.90 | 9.43 |

| BC4 | Diamond | 4 | 1.00 | 6.33 |

| BC5 | Box | 4 | 0.50 | 6.30 |

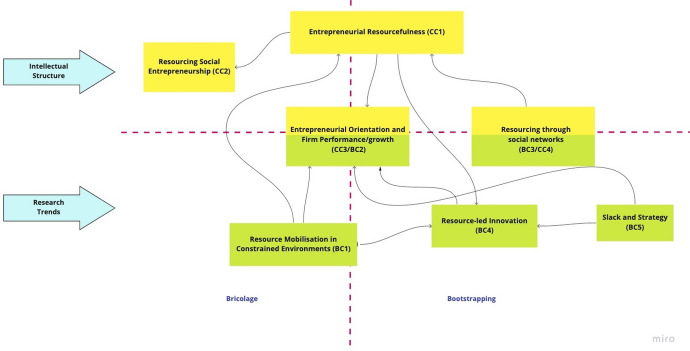

Integration of the bibliometric results

The harmony between the results of co-citation and bibliographic coupling is essential to understand the synergies between the two pieces of literature (Vasconcelos Scazziota et al. 2020). Figure 3 shows the integration of results based on the content of the studies loaded to each factor. The intellectual structure of the literature comes from the co-citation analysis and the research trends from the bibliographic coupling. In our analysis, factor CC1 (entrepreneurial resourcefulness) finds support by works in factor BC3/CC4 (both discussing resourcing through social networks) that discuss how entrepreneurs use their social networks to acquire limited resources for their firms. Entrepreneurs use their networks not just to gain the information required to acquire resources at the best terms but also to gain the requisite goodwill to access them from their networks. Factor BC1 (resource mobilization in constrained environments) deals with the mobilization of resources in resource-constrained environments to act on available opportunities. Therefore, factor BC1 (resource mobilization in constrained environments) leads entrepreneurs to employ bootstrapping and bricolage (entrepreneurial resourcefulness: CC1) in underdeveloped factor markets with institutional voids. The resource constraints due to the lack of supportive institutions, especially in developing countries, act as a catalyst toward resourcefulness in this situation. Further, the concept of bricolage (entrepreneurial resourcefulness: CC1) often finds a place in the social entrepreneurship literature (resourcing social entrepreneurship: CC2). Thus, factor CC1 (entrepreneurial resourcefulness) helps social ventures (CC2: resourcing social entrepreneurship) scale their businesses by accessing and creatively using resources to impact base-of-the-pyramid communities by finding innovative solutions to customers’ problems while also focusing on both the financial and social impact of their actions. Resource-led innovation (BC4) and the consequent firm performance (CC3 and BC2) find support in resource mobilization using bootstrapping and bricolage. The resource-led hit-and-trial and improvisational ways of resource mobilization, with already owned or cheaply available resources, often balance out with the routine actions to provide exceptional firm performance.

Fig. 3.

Result integration

Moreover, in terms of innovation, works in factor CC1 (entrepreneurial resourcefulness) explicitly state how entrepreneurs can create unanticipated innovations by creatively employing limited and mostly otherwise worthless resources. This is more critical in resource-constrained environments (BC1) characterized by low-income settings and institutional voids, as the focus is not on using available resources and supporting institutions for conventional purposes but on a more hands-on approach to taking action even without the right resources and support. Finally, the presence of slack (slack and strategy: BC5) resources in the business also support innovation in the firms as it encourages exploration and allows experimentation with the excess resources, thereby promoting initiative. Scholars have suggested that ventures with slack resources tend to strategically experiment and take risks that might benefit their innovativeness (resource-led innovation: BC4) and finally result in better venture performance (CC3/BC2). Different entrepreneurs adopt bootstrapping strategies (slack and strategy: BC5) to achieve their business goals by innovatively transforming their available resource base to create value. Literature suggests that these resourcefulness behaviors are often a planned strategic push from the entrepreneur and not a last resort due to resource shortages.

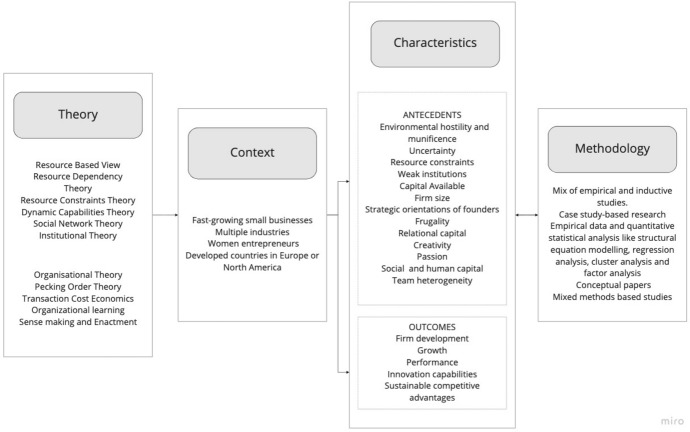

TCCM analysis

This analysis involves a systematic review of bootstrapping and bricolage literature following the TCCM approach (Paul and Rosado-Serrano 2019; Singh and Dhir 2019). Figure 4 details the TCCM framework which helped identify the various gaps in the existing literature to propose new directions for future research.

Fig. 4.

TCCM Framework

Theory development

With the increase in academic research on entrepreneurship, scholars have identified multiple theoretical perspectives that help explain the resource mobilization behaviors of entrepreneurs in resource constraints. Due to the differences in the resourcing strategies of big companies and entrepreneurial firms, scholars have used classic theories for studying entrepreneurial behaviors with a modified perspective. Some of the prominent ones are resource dependency theory (Pfeffer and Salancik 2015), resource constraint theory (Loasby and Leibenstein 1976), resource-based view (Barney 1991), dynamic capabilities theory (Teece et al. 1997), pecking order of theory (Myers and Majluf 1984), institutional theory (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Meyer and Rowan 1977) and traditional finance theory, organizational learning (Argyris and Schön 1997).

The resource-based view and resource dependency theory suggest that a business's success depends on the resources it can acquire, which have an important role to play in achieving competitive advantage (Desa and Basu 2013; Harrison et al. 2004; Jayawarna et al. 2011; Jones and Jayawarna 2010). These theories have been used in this context as the resource dependency theory also holds that firms should reduce their reliance on external parties for resource acquisition. The resource constraint theory highlights how entrepreneurs operate their ventures by combining and recombining available resources under constraints (Baker and Nelson 2005). Scholars have also mentioned the traditional finance theory and Myers pecking order theory which imply that the financing decisions of a business are influenced by the cost of debt or equity while funding initial capital needs using flexible internal sources (Brush et al. 2006; Carter and van Auken 2005; Neeley and van Auken 2010; van Auken 2005; Vanacker et al. 2011). There is also the prevalence of transaction cost economics (Williamson 1979) in analyzing which source of capital is most suitable for newer ventures (Bellavitis et al. 2017). Literature also uses organizational theory to predict the behaviors of entrepreneurs who are bootstrapping their startups (Ebben and Johnson 2006).

Further, institutional theory also finds a place in the studies due to the importance of the external business environment and activities undertaken by startup founders who leverage resources available to them to create new institutions (Bellavitis et al. 2017; Desa 2012; Phillips and Tracey, 2007; Politis et al. 2012). Multiple researchers have chosen social network theory to explain how entrepreneurs gather resources from their networks (Bizri 2017; Carter et al. 2003; Dabić et al. 2020; Evers and O’Gorman 2011; Jonsson and Lindbergh 2013). Even though multiple theories in literature have briefly explained entrepreneurial actions like bricolage and bootstrapping, there is still a need to identify theories that explain patterns of these resource mobilization behaviors. The current literature offers little direction toward understanding how entrepreneurs creatively accumulate and employ resources at hand innovatively to survive resource limitations.

Context

Academic research in bootstrapping and bricolage currently focuses on fast-growing small businesses across multiple industries. Scholars have also conducted various studies focusing on women entrepreneurs and how their resource mobilization behaviors differ from their male counterparts (Brush et al. 2006; Carter et al. 2003). However, most of the existing research focuses on studying ventures in developed countries in Europe or North America (Baker et al. 2003; Brush et al. 2006; Carter et al. 2003; Carter and van Auken 2005; Ebben 2009; Ebben and Johnson 2006; Senyard et al. 2014). Both the literature consist of multi-disciplinary works on different aspects of resource management like strategic motives, stages of the business, and uncertainty and institutional voids in the environment (Brush et al. 2006; Ebben and Johnson 2006; Mair and Marti 2009; Winborg 2009). There has also been a considerable focus on the human and social capital aspect along with their impact on how the business eventually performs (Ebben 2009; Grichnik et al. 2014; Jayawarna et al. 2011; Stinchfield et al. 2013; Vanacker et al. 2011). Recent literature also studies the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurial resource management behaviors, given the need to build resilience in challenging crisis driven markets (Brown et al. 2020; Kuckertz et al. 2020; Ma and Yang 2022). Overall, contextually fragmented research for developed countries is available, making it difficult to generalize and draw conclusions.

Characteristics

Studies have identified various antecedents like environmental factors such as environmental hostility and munificence, uncertainty, resource (knowledge and financial) constraints, and weak institutions, business factors like traditional financial capital access, firm size, and entrepreneurial factors like strategic orientations of founders, frugality, relational capital, creativity and passion, social capital and human capital, team heterogeneity (An et al. 2018; Grichnik et al. 2014; Grichnik and Singh 2010; Iqbal et al. 2021; Miao et al. 2017; Michaelis et al. 2020; Rahman et al. 2020; Rutherford et al. 2017; Stenholm and Renko 2016; Su et al. 2020). Further, academicians have also studied the impact of these resource mobilization behaviors on firm development, growth, performance, innovation capabilities, and sustainable competitive advantages (Brush et al. 2006; Ebben 2009; Ernst et al. 2015; Fisher 2012; Harrison et al. 2004; Jones and Jayawarna 2010; Salunke et al. 2013; Senyard et al. 2014; Vanacker et al. 2011). Despite the literature on the antecedents and outcomes of bricolage and bootstrapping, the results often conflict. While some studies suggest a positive impact of bootstrapping and bricolage on firm performance, others highlight that they can result in inferior quality business offerings and unconventional solutions that may not be suitable for the customers in the long run (Baker and Nelson 2005; Jones and Jayawarna 2010; Rutherford et al. 2012). Therefore, there is a need for more empirical research on the antecedents and outcomes of these resourcefulness behaviors.

Methods

Prior works in entrepreneurial bootstrapping and bricolage consist of a mix of empirical and inductive case-based papers. The case study-based research uses an inductive grounded theory method suitable for understanding activities in real-time both within and outside the venture to understand how these resource management activities unfold in entrepreneurial ventures (Baker et al. 2003; Baker and Nelson 2005; Ferneley and Bell 2006; Halme et al. 2012; Harrison et al. 2004; Jonsson and Lindbergh 2013; Mair and Marti 2009). Moreover, multiple studies use empirical data and quantitative statistical analysis like structural equation modeling, regression analysis, cluster analysis, and factor analysis (Brush et al. 2006; Carter et al. 2003; Ebben and Johnson 2006; Jones and Jayawarna 2010; Neeley and van Auken 2010; Senyard et al. 2014; Winborg 2009; Winborg and Landström 2001). Further, many highly cited works in this literature consist of conceptual papers (Baker 2007; Boxenbaum and Rouleau 2011; Duymedjian and Rüling 2010; Phillips and Tracey 2007; Stinchfield et al. 2013; Welter et al. 2016). Future research can also incorporate some mixed methods based studies which are currently very limited (Desa 2012; Kuckertz et al. 2020).

Discussion

Despite the similarities in their resourcefulness nature, the concepts of entrepreneurial bootstrapping and bricolage are yet to be integrated systematically into literature. Both behaviors act as potential key dynamic capabilities that help firms access, enhance and integrate limited resources that might be deemed obsolete or worthless. While bootstrapping primarily deals with how entrepreneurs access financial, material, and knowledge resources for their businesses, bricolage involves creatively applying these resources to enhance their limited resource base. Bootstrapping helps bolster the resource base, which is further made more flexible and innovative by creative reinvention of resources using bricolage. While bootstrapping deals with using informal ways to access, borrow or share resources creatively, bricolage involves deploying these resources in novel ways to extract value from them that others might ignore, making bricolage a strategic action triggered when entrepreneurs decide to strategically bootstrap their ventures. Refer to Sect. 2 for a better understanding of the differences and similarities between the two concepts.

The bricolage literature focusing more on resource mobilization in resource-limited environments with institutional voids might benefit from bootstrapping techniques. Meanwhile, research trends in bootstrapping focus on resource-led innovations, strategic use of slack resources, and strategic application of resource acquisition activities. Bricolage activities complement these research trends by involving a creative reinvention of slack resources to strategically innovate a firm's resource management. Both entrepreneurial bootstrapping and bricolage focus on the critical role of resources for operations and survival of the business in a resource-scarce environment by emphasizing taking action by managing with the existing resources without any external help to strategically respond to the uncertain environment. The unconventional “do-it-yourself" approaches and the critical role of the entrepreneurs’ social capital to access resources and test products emphasize the central role of the entrepreneur (human capital, social capital, and behavior patterns) in both behaviors. The resource led innovation and creative reinvention is critical to discovering and exploiting business opportunities.

The joint analysis of these two studies using bibliometric techniques demonstrates that the two behaviors have evolved drastically and that the latest research trends suggest a possible convergence of the two. The bibliographic coupling analysis helped understand the research trends to better understand the evolution of publications and probable joint paths hinting at a convergence between the two. Further, the intellectual structure (co-citation) analysis enables a better understanding of the origins and relationship between the two pieces of literature. Studying the two together facilitates discerning their embedded patterns and interrelationships while incorporating the entire published literature in this area (Duran-Sanchez et al. 2019; Vasconcelos Scazziota et al. 2020). Therefore, a combined effort from bricolage and bootstrapping can help build a more resilient venture and be in a better position to tackle any such resource disruptions in the case of a crisis or otherwise. This study is an effort in this direction as it suggests a probable integration between the two approaches that might help entrepreneurship scholars understand entrepreneurial resource behaviors better.

Bibliographic coupling analysis shows that both behaviors show pre-dominance of research on their impact on firm performance (venture performance and growth: BC2). The results of co-citation analysis strengthen this by presenting firm performance (entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: CC3) as a crucial part of the intellectual structure of the two pieces of literature. Bootstrappers depend on their social networks to access resources, given the uncertainties that entrepreneurs operate in. Therefore, research on using entrepreneurial social capital (both weak and strong ties) has been a prominent research trend that can potentially benefit from bricolage. Using network bricolage (Baker et al. 2003) could be transformational in this aspect as it involves working with people in a firm's network. Bricolage will help work around the resource limitations to find new solutions to entrepreneurial problems using their creativity and networking skills.

A systematic co-citation analysis highlighted the intellectual structure of the approaches. The factor analysis suggests that, though some of these works deal directly with one of the two areas, they are also present in the other literature. Thus, a clear overlap between the two pieces of literature is present. All the factors identified in the co-citation analysis involved works referenced in both the literature. Factor CC1 pertaining to entrepreneurial resourcefulness details classical and seminal works in both approaches, along with the works that helped develop the understanding of these behaviors. Although factor CC2 deals with resourcing social entrepreneurship ventures that generally use bricolage for resource management, co-citation analysis results highlight the presence of bootstrapping, improvisation, and tinkering literature in this factor. Moreover, firm performance and entrepreneurial orientation (Factor CC3) discusses how an organization and its resource management reflect its founders and team members. The bootstrapping and bricolage literature highlights the resource-based theory by considering entrepreneurial cognition and the ability to access, accumulate and combine resources as a critical component of a firm’s resource management and performance. Finally, as noted above, research around the use of social networks (Factor CC4) for accessing and creatively deciding to use resources has proved to be an important intellectual structure aspect.

This bibliometric analysis helped to identify the differences and similarities in the knowledge base and intellectual structure (Grégoire and Cherchem 2020; Zupic and Čater 2015). The first contribution of this study is to consider these two approaches in synergy to understand them better together. These two behaviors complement each other as bootstrapping helps arrange for the finances, material resources, knowledge, and skills that are then creatively applied by the bricoleurs. Therefore, studying the two approaches together is interesting while considering their unique aspects (accumulation vs. deployment). This study will help direct scholarly attention toward including these behaviors in existing frameworks. With the increase in the number of publications, growing theoretical bases, and diverse methodologies, the current literature, which lacks integration of the two related concepts, can benefit from this bibliometric study as it helps overcome the idiosyncrasies that might arise in reviewing a large number of works, given the capabilities and biases of a researcher subjectively reviewing them alone. The results of this study depend on the systematic techniques of science mapping that helped analyze the combined literature in ways impossible through existing qualitative reviews.

Another contribution of this study is, thus, to direct literature toward understanding how bootstrapping can be considered a precursor or first step to bricolage behaviors. The two behaviors together can assist new ventures in accumulating and arranging resources in ingenious ways to build resilient businesses and provide a complete picture of the resource management processes of new entrepreneurial ventures. Academicians can also work towards the development of a common measurement scale to facilitate combined empirical research in this direction. Therefore, this study adds a new perspective for entrepreneurship researchers to explore the combined or sequential application of bootstrapping and bricolage. Finally, the TCCM analysis also helps propose some probable research gaps directed toward identifying theories that can undergo empirical tests using mixed-methods research to explain patterns of these resource mobilization behaviors. Therefore, scholars in this area should consider a joint analysis of these two approaches to develop a common measurement and test it using the qualitative grounded theory approach and empirically in quantitative studies.

Conclusion, limitations, and future work

In this study, the aim was to systematically analyze the literature on bootstrapping and bricolage to help understand the existing literature more methodically by enabling us to assimilate the contributions of scholars to get a comprehensive picture of the behaviors (Grégoire and Cherchem 2020; Zupic and Čater 2015). As suggested by Gregóire and Cherchem (2020), this bibliometric analysis further helped understand the rational structures of both the areas and the complementarities and differences between them (Donthu et al. 2021; Habib and Afzal, 2019; Rey-Martí et al. 2016). A co-citation analysis of both behaviors combined helped us understand the intellectual structures of the literature. A research trend analysis supported this as a result of the bibliographic coupling. Further, the combined TCCM analysis highlighted the theoretical developments, contexts, characteristics, and methodologies used in the two pieces of literature and suggested existing gaps in the literature.

Since the concepts of bootstrapping and bricolage have mostly developed in isolation and there exists a missing integration between the two, this study can be used as a starting point to further research on how these two behaviors can potentially converge and contribute to each other. The two entrepreneurial behaviors of bootstrapping and bricolage demonstrate convergence and mutually contribute to each other's literature. Overall, this study contributes to enhancing our understanding of the dynamics of resource management by entrepreneurs who operate in uncertain environments using flexible and informal approaches. This systematic empirical approach can also help to analyze other conceptually similar approaches in entrepreneurship. These concepts can then be applied together to contribute to other entrepreneurship and strategic management fields.

Future studies should consider the following research agendas to add to the research in this area (i) Fitting these two related behaviors in one existing framework to guide entrepreneurs employing these informal methods to sail through the challenges of the post COVID-19 pandemic; (ii) Developing a standard measurement scale for the two closely related behaviors; (iii) Generalization and validation of the measurement instrument through both qualitative and empirical research; (iv) Extending the proposed integration by delving deeper into the theoretical integration of the two streams of literature; (v) Exploring the shared antecedents of these two behaviors and devising a hierarchical framework to understand their interrelationships; (vi) Studying and adding to the literature of different combinations of action theories in entrepreneurship like bricolage and improvisation, bootstrapping and jugaad, bricolage and effectuation to develop a more generalizable and broader model or framework of entrepreneurial resource management behaviors; (vii) Exploring similar experimental research designs to further study theoretical integration and thematic similarities of various entrepreneurial behaviors whose resemblance is not explained by existing models in the entrepreneurship literature; (viii) Exploring the unique mechanisms through which social entrepreneurs create resource opportunities by employing both bootstrapping and bricolage (ix) Understanding the unique position of social enterprises in building and leveraging the credibility and creating economic and social value while bootstrapping for acquiring and mobilizing business resources.

Although the sample of documents for this study comes from one of the most comprehensive databases, some published works were outside the scope of the database. Future studies can consider a similar analysis by considering works from other databases. The sample of this study had more works in the bricolage literature as it has a higher number of research publications. This might be responsible for a stronger influence of bricolage works on the overall analysis. Moreover, publications with more referenced documents might influence the analysis. Even though bibliometric studies present a structured and systematic way of analyzing literature, they can not replace the in-depth analysis derived from a complete content analysis based study. Future studies analyzing bootstrapping and bricolage together can focus more on in-depth qualitative content-based analysis. As understood from the TCCM analysis, further studies should also consider mixed-method research in these areas for newer contexts like developing nations.

Scholars studying entrepreneurial resource behaviors can also use a similar analysis to explore convergence and differences between other approaches like improvisation, effectuation, and jugaad. Further, apart from researching these behaviors theoretically, scholars should also shift their focus on empirical qualitative and quantitative studies to understand how these approaches unfold in the case of resource-deficient ventures struggling their way through volatile pandemic hit markets. Apart from helping to understand resourcefulness behaviors in synergy, this study can further spur deliberation and research over other concepts which add value to the field of entrepreneurial research. Finally, this study should can act as a base for directing research toward exploring new ways in which entrepreneurs use these two behaviors together by developing a common measure for the two and testing it empirically in different entrepreneurial contexts.

Appendix 1: Top journals for the sample selected

| S. No. | Sources (Journals) | No. of. articles |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Entrepreneurship and Regional Development | 16 |

| 2 | Journal of Business Venturing | 9 |

| 3 | International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research | 7 |

| 4 | Venture Capital | 7 |

| 5 | International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation | 6 |

| 6 | Small Business Economics | 6 |

| 7 | Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice | 4 |

| 8 | Journal of Business Research | 4 |

| 9 | Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship | 4 |

| 10 | Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal | 4 |

| 11 | Technological Forecasting and Social Change | 4 |

| 12 | International Business Review | 3 |

| 13 | International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal | 3 |

| 14 | International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management | 3 |

| 15 | International Journal of Innovation Management | 3 |

| 16 | Journal of Business Venturing Insights | 3 |

| 17 | Journal of Entrepreneurship In Emerging Economies | 3 |

| 18 | Journal of Product Innovation Management | 3 |

| 19 | Management Decision | 3 |

| 20 | Technology Analysis and Strategic Management | 3 |

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mansi Singh, Email: mansi.singh@dms.iitd.ac.in.

Sanjay Dhir, Email: sanjaydhir@dms.iitd.ac.in.

Harsh Mishra, Email: hmishra@quantic.edu.

References

- Al Issa H-E. The impact of improvisation and financial bootstrapping strategies on business performance. EuroMed J Bus. 2020;16(2):171–194. doi: 10.1108/EMJB-03-2020-0022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez SA, Barney JB. Discovery and creation: alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Revis Organ Contex. 2007 doi: 10.15603/1982-8756/roc.v3n6p123-152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez SA, Busenitz LW. The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. J Manag. 2001 doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063(01)00122-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An W, Zhang J, You C, Guo Z. Entrepreneur’s creativity and firm-level innovation performance: bricolage as a mediator. Technol Anal Strateg Manag. 2018;30(7):838–851. doi: 10.1080/09537325.2017.1383979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An W, Rüling C-C, Zheng X, Zhang J. Configurations of effectuation, causation, and bricolage: implications for firm growth paths. Small Bus Econ. 2020;54(3):843–864. doi: 10.1007/s11187-019-00155-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archer GR, Baker T, Mauer R. Towards an alternative theory of entrepreneurial success: integrating bricolage, effectuation and improvisation. Front Entrep Res. 2009;29(6):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris Ch, Schön DA. Organizational learning: a theory of action perspective. Reis. 1997 doi: 10.2307/40183951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch DB. The dynamic role of small firms: evidence from the U.S. Small Bus Econ. 2002;18(1):13–40. doi: 10.1023/A:1015105222884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. Resources in play: bricolage in the toy store(y) J Bus Ventur. 2007;22(5):694–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T, Nelson RE. Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Adm Sci Q. 2005;50(3):329–366. doi: 10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T, Miner AS, Eesley DT. Improvising firms: Bricolage, account giving and improvisational competencies in the founding process. Res Policy. 2003;32(2 SPEC):255–276. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00099-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker HK, Kumar S, Pandey N. Thirty years of small business economics: a bibliometric overview. Small Bus Econ. 2021;56(1):487–517. doi: 10.1007/S11187-020-00342-Y/TABLES/16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barney J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag. 1991 doi: 10.1177/014920639101700108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett RC. Entrepreneurial bricolage: developing recipes to support innovation. Int J Innov Manag. 2016 doi: 10.1142/S1363919616400107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bellavitis C, Filatotchev I, Kamuriwo DS, Vanacker T. Entrepreneurial finance: new frontiers of research and practice: Editorial for the special issue embracing entrepreneurial funding innovations. Ventur Cap. 2017;19(1–2):1–16. doi: 10.1080/13691066.2016.1259733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berends H, Jelinek M, Reymen I, Stultiëns R. Product innovation processes in small firms: combining entrepreneurial effectuation and managerial causation. J Prod Innov Manag. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jpim.12117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AN, Udell FG. The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. J Bank Financ. 1998 doi: 10.1016/S0378-4266(98)00038-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhide A. Bootstrap finance: the art of start-ups. Harv Bus Rev. 1992;70(6):109–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizri RM. Refugee-entrepreneurship: a social capital perspective. Entrep Reg Dev. 2017;29(9–10):847–868. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2017.1364787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, Fisch C, Hirschmann M. The determinants of bootstrap financing in crises: evidence from entrepreneurial ventures in the COVID-19 pandemic. Small Bus Econ. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11187-020-00445-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP, Everett MG, Freeman LC. Ucinet for windows: software for social network analysis. Harvard: Analytic Technologies; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Boxenbaum E, Rouleau L. New knowledge products as bricolage: Metaphors and scripts in organizational theory. Acad Manag Rev. 2011;36(2):272–296. doi: 10.5465/amr.2009.0213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]