Abstract

By using improved transformation methods for Wangiella dermatitidis, and a cloned fragment of its chitin synthase 4 structural gene (WdCHS4) as a marking sequence, the full-length gene was rescued from the genome of this human pathogenic fungus. The encoded chitin synthase product (WdChs4p) showed high homology with Chs3p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and other class IV chitin synthases, and Northern blotting showed that WdCHS4 was expressed at constitutive levels under all conditions tested. Reduced chitin content, abnormal yeast clumpiness and budding kinetics, and increased melanin secretion resulted from the disruption of WdCHS4 suggesting that WdChs4p influences cell wall structure, cellular reproduction, and melanin deposition, respectively. However, no significant loss of virulence was detected when the wdchs4Δ strain was tested in an acute mouse model. Using a wdchs1Δ wdchs2Δ wdchs3Δ triple mutant of W. dermatitidis, which grew poorly but adequately at 25°C, we assayed WdChs4p activity in the absence of activities contributed by its three other WdChs proteins. Maximal activity required trypsin activation, suggesting a zymogenic nature. The activity also had a pH optimum of 7.5, was most stimulated by Mg2+, and was more inhibited by polyoxin D than by nikkomycin Z. Although the WdChs4p activity had a broad temperature optimum between 30 to 45°C in vitro, this activity alone did not support the growth of the wdchs1Δ wdchs2Δ wdchs3Δ triple mutant at 37°C, a temperature commensurate with infection.

Chitin, a linear molecule of β-(1-4)-linked N-acetylglucosamine, is a major structural constituent of the fungal cell wall (16, 49). Chitin quantity varies in different fungi and in different cell types of the same fungus (3, 8, 59). It is a minor (1%) component of cell walls of most yeasts, but amounts are usually higher in the cell walls of filamentous fungi (14). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, more than 90% of the chitin is located in the region of the yeast cell bud scar (38). However, greater amounts of mislocalized chitin occur in a variety of cell division cycle mutants of S. cerevisiae, indicating that chitin synthesis is temporally and spatially regulated during the yeast cell cycle (44, 47). In vegetative hyphae of filamentous fungi, chitin deposition is most concentrated in septa and at the apexes of growing hyphae (25, 59).

Chitin synthases are responsible for the polymerization of chitin and are primarily zymogens associated with fungal plasma membranes (12). In both S. cerevisiae and Candida albicans, three chitin synthase structural genes (CHS) have been identified and characterized (10, 37). Numerous other CHS genes have been identified in other fungi. Based on derived amino acid sequences of PCR products, fungal chitin synthases were first grouped as three classes (7). Additional classes were then defined, and now at least five isozyme classes are recognized (33). However, only in the case of S. cerevisiae has each isozyme (Chs) been linked with some certainty to specific functions during cell growth and development (9, 11, 51, 57). In this fungus, Chs3p, which belongs to the class IV group of chitin synthases (7), produces 90% of the cell wall chitin in yeast cells budding normally, and this chitin is localized both in the lateral wall and in the chitin ring that serves as the bud emergence locus (57). Although no single Chs enzyme is essential for the viability of S. cerevisiae, strains without functional class II (Chs2p) and class IV (Chs3p) isozymes lose viability (11, 16). In contrast to this central role for the class IV enzyme in S. cerevisiae, in filamentous fungi the class III chitin synthases, which have no homolog in yeast, are most often reported to be essential for normal hyphal growth (34, 61, 62). In fact, the class IV chitin synthases identified in Neurospora crassa, Aspergillus nidulans, and A. fumigatus have been regarded as redundant enzymes (1, 5, 40), even though additional genes encoding class IV chitin synthase homologs were found in both Aspergillus species (33, 35, 52).

Wangiella (Exophiala) dermatitidis is an asexual fungal pathogen of humans that is associated with cutaneous and subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (30). In vivo, this member of the Fungi Imperfecti produces a variety of vegetative growth forms with dark, melanized (dematiaceous) cell walls, such as ovoid yeasts, pseudohyphae, hyphae and isotropically enlarged, spherical cells, and multicellular forms (20, 32, 41). In vitro, yeast cells of W. dermatitidis are easily manipulated in ways that allow morphological transitions to isotrophic multicellular forms and hyphae (18, 24, 28, 54). This inherent vegetative polymorphism of W. dermatitidis allows it to serve as a valuable model for the study of the more than 100 other dematiaceous fungi known to cause human infection (31, 55). The numerous new transformation and gene disruption systems developed for the molecular manipulation of this organism (31, 45, 64) also make it an unusually attractive model for determining the function of potential cell wall-related virulence factors, such as chitin, in dimorphic and polymorphic pathogenic fungi.

In yeast cells of W. dermatitidis, chitin is found in relatively low amounts and is localized primarily in septal regions (19, 26, 54, 56). Multicellular forms and hyphae also have chitin in their septa but have considerable additional chitin in other cell wall areas (54–56). Because these morphological transitions are accompanied not only by increases in chitin but also increases in cell wall 1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene melanin (19, 54), melanin biosynthesis has been studied extensively and shown to contribute significantly to the pathogenicity and virulence of W. dermatitidis (21–23, 48). However, the specific role of chitin and its contribution to virulence have not been similarly established for this pathogen.

Three different genes (WdCHS) encoding class I, II, and III chitin synthases were initially identified in W. dermatitidis by PCR and Southern blotting and then cloned by screening genomic and cDNA libraries (7, 31, 36, 56, 58, 63). In this study, we describe the cloning, characterization, and effects of disruption of the fourth WdCHS gene (WdCHS4) of W. dermatitidis, and we also characterize the enzymatic activity of its gene product (WdChs4p). Our results showed that this gene is most likely constitutively expressed, that its product is grouped to class IV, and that the chitin contributed by WdChs4p influences wall structure, cell surface properties, cellular reproduction, and melanization but not virulence. Our results also showed that WdChs4p could not alone support growth at 37°C of a triple chitin synthase mutant of W. dermatitidis having only an intact WdCHS4 gene. However, because this triple mutant grew adequately at 25°C, we were able to characterize the activity of the class IV-type isozyme of W. dermatitidis in the absence of any confounding influence of its other WdChs activities. Furthermore, our comparative studies of the wild-type strain with strains having only WdCHS4 disrupted and with the triple mutant derived by the sequential disruption of WdCHS1, WdCHS2, and WdCHS3 but not WdCHS4, allowed us to suggest why WdChs4p of W. dermatitidis may not be particularly important to virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

General propagation of the laboratory wild-type strain of W. dermatitidis 8656 (ATCC 34100; E. dermatitidis CBS 527.6), the type strain (ATCC 28869), and the temperature-sensitive mutants Mc3 (wdcdc2; ATCC 38716) and Hf1 was either in the rich medium YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) or the synthetic medium CDN (19), which was prepared by adding the following components (grams per liter) to 0.05 M sodium succinate buffer (pH 6.5): glucose, 30; NaNO3, 3; K2PO4, 1; MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.5; FeSO4 · 7H2O, 0.01; NH4Cl, 0.625; and thiamine, 0.003. The chitin synthase wdchs1Δ wdchs2Δ double mutant and wdchs1Δ wdchs2Δ wdchs3Δ triple mutant of W. dermatitidis were obtained by consecutive gene disruptions using vectors with phleomycin, sulfonyl urea, and hygromycin resistance genes as selective markers (reference 63; details to be reported elsewhere). Escherichia coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), which was used for the subcloning and plasmid preparation, was grown in LB medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml).

Preparation and analysis of nucleic acids.

Genomic DNA was isolated by spheroplasting with Zymolyase-20T (ICN Biomedicals, Inc., Aurora, Ohio) followed by detergent lysis, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation as previously described (39). Total RNA was isolated by the hot phenol method (2). Southern and Northern blotting were performed by standard methods (2) except for Southern blotting of the karyotype, which was done as previously described (64). DNA fragments (25 ng) used for probes in Southern and Northern analysis were labeled with [α32P]dATP by using a Prime-a-Gene kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Plasmids containing WdCHS4 gene fragments were automatically sequenced by the Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology of The University of Texas at Austin. Sequence analysis was performed with the Wisconsin Package G software (Genetics Computer Group, Inc.). PCR amplifications, using Taq DNA polymerase and nucleotides obtained from Promega, were carried out in a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.) for 1 cycle of 4 min at 94°C, then 29 cycles of 2 min at 94°C, 3 min at 50°C, and 4 min at 72°C, and finally 1 cycle similar to the previous ones but with a 10-min elongation step. The 366-bp PCR fragment of the WdCHS4 gene was amplified from W. dermatitidis 8656 genomic DNA by using primers CAL1-1 (5′ CAAGTGTTTGAGTACTATATTTCGCAT 3′) and CAL1-2 (5′ CGTAGAATTAATCCATCTTCGACGCTG 3′). The 876-bp fragment was amplified from a truncated WdCHS4 clone by using primers CAL1-1 and CAL1-3 (5′ GTCATAGTCACGGTAGGG 3′).

Plasmid construction.

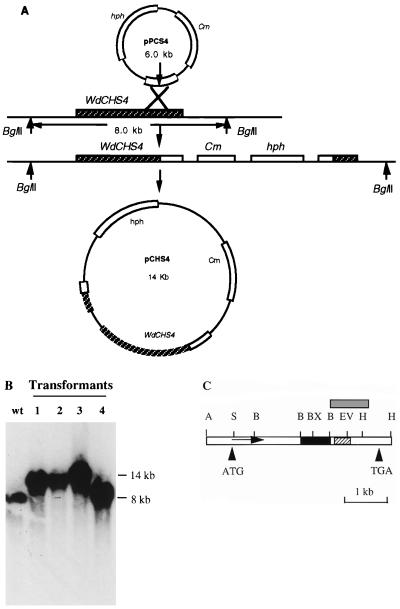

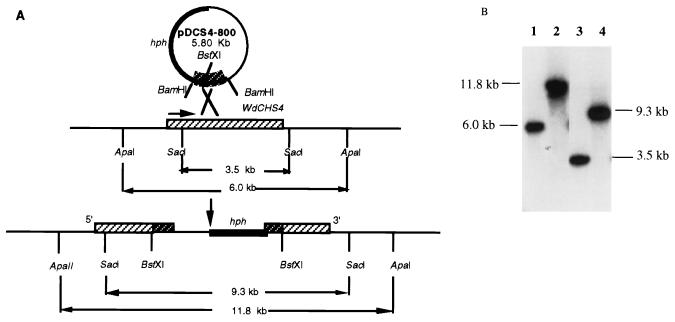

The marker rescue plasmid pPCS4 (Fig. 1A) was constructed by inserting the 870-bp ApaI-SacI fragment from pBF4 (provided by B. Feng) containing the 3′-end sequence of WdCHS4 into pCB1004 (provided by J. Sweigard, DuPont Co., Wilmington, Del.), which is a pBluescript SK(+)-based vector that contains the hygromycin phosphotransferase gene (hph) from E. coli, which confers resistance to hygromycin B (HmB), and the tryptophan synthase (trpC) promoter from A. nidulans (13). The 870-bp fragment was originally cloned by library screening using the 366-bp PCR product as a probe (see above). The WdCHS4 disruption plasmid pDCS4 (see Fig. 4A) was constructed by inserting an 800-bp BamHI fragment from the rescued plasmid, pMRCHS4, into pAN7-1 (45), which, unlike pCB1004, contains the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gpd) promoter and the trpC terminator from A. nidulans, in addition to the hph gene.

FIG. 1.

Cloning WdCHS4 by a marker rescue technique. (A) The partial WdCHS4 gene fragment (876 bp) was used in a marker rescue method to clone the whole gene by integrating this fragment with HmB resistance (hph) and chloramphenicol resistance (Cm) gene markers into the WdCHS4 locus. The recombinant plasmid pPCS4, which carried this PCR fragment in the pCB1004 vector, was linearized with EcoRV and transformed into W. dermatitidis 8656 yeast cells. (B) Southern hybridization analysis of four transformants in which pPCS4 was integrated into the W. dermatitidis genome. Genomic DNA of the wild type (wt) and transformants 1 to 4 was extracted, digested with BglII, and subjected to Southern blotting using a 876-bp WdCHS4 PCR fragment as a probe. Transformants 1, 2, and 3 showed hybridization consistent with site-specific integration into the WdCHS4 locus, whereas the plasmid was ectopically integrated in transformant 4. (C) Restriction map of WdCHS4. The gray box represents the 876-bp fragment used for marker rescue, the black box represents the 800-bp BamHI-digested fragment used for gene disruption, and the hatched box represents the 366-bp PCR fragment used for library screening. Restriction enzyme abbreviations: A, ApaI; B, BamHI; BX, BstXI; H, HindIII; S, SacI.

FIG. 4.

Disruption of WdCHS4 gene in W. dermatitidis. (A) Predicted structure for integration of pDCS4-800 at the wdchs4 locus. (B) Southern hybridization analysis of the wdchs4Δ-1 disruptant strain. The recombinant plasmid pDCS4-800 linearized with BstXI was transformed into W. dermatitidis 8656. Southern blots of genomic DNA from W. dermatitidis 8656 (lanes 1 and 3) and wdchs4Δ-1 strain (lanes 2 and 4), digested with ApaI (lanes 1 and 2) and SacI (lanes 3 and 4), were hybridized with a 0.8-kb WdCHS4 BamHI fragment.

Transformations.

Yeast cells of W. dermatitidis cultivated for 20 h in YPD at 25°C were harvested and chilled on ice for 30 min, after which time the cells were washed twice and resuspended in cold 10% glycerol. Plasmid (∼5 μg) was then mixed with this cell suspension (200 μl), and electroporation was conducted at 1.45-kV field strength, 200-Ω resistance, and 25-mF capacitance, corresponding to a time range 4 to 6 ms. Transformed cells were incubated with YPD (1 ml) with shaking at 25°C for 3 h before being spread on HmB (40 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)-containing YPD plate medium, which was incubated at 25°C for 4 to 6 days.

Microscopy.

Cellular morphology was documented by using a Zeiss ICM 405 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Oberkochen, Germany) with Nomarski differential interference, phase-contrast optics, a 63× oil immersion objective, and M35 automatic camera. The procedure for preparing specimens for scanning electron microscopy (17) was modified as follows. Cells were harvested from log-phase CDN cultures and fixed overnight in sodium cacodylate-buffered 25% glutaraldehyde at 4°C. The fixed cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, attached to coverslips pretreated with 50 μl of poly-l-lysine (2 mg/ml; molecular weight, 4,000,000), and dehydrated in an ethanol-acetone (10, 25, 40, 50%, and 100% ethanol) series followed by an acetone-amyl acetate (50, 40, 25, 15, and 5% acetone) series. The dehydrated specimens were then submerged in amyl acetate for 15 min, critical-point dried (Tousimis Samdri-790), and sputter coated (Ladd model 30800) with gold for 60 s at 2.5 kV and 20 mA. Specimens were examined in a Philips 515 scanning electron microscope.

Chitin content and chitin synthase activity assays.

Chitin contents were measured by a modification of the procedure described by Yabe et al. (60). Log-phase yeast cells were harvested from 20-ml cultures, suspended in 4 M HCl (1 ml), and boiled for 4 h. After dilution of hydrolysates with H2O (19 ml), the amount of hexosamine in a diluent (1 ml) was determined by the Elson-Morgan method (6), using N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (GlcNAc) (Sigma) as a standard. Cell dry weights for calculation of chitin content per milligram of cells were determined by collection of cells from 20-ml cultures on preweighed 0.45-mm-pore-size membrane filters (type HA; Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.), which were subsequently washed with distilled water and then dried at 65°C to a constant weight.

Cell membranes were prepared and activities of chitin synthase was determined by the method of Orlean (43). Membrane proteins were dissolved in TM buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 40 mM MgCl2) except for the membrane protein of the chitin synthase wdchs1Δ wdchs2Δ wdchs3Δ triple mutant, which was dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl. Concentrations of membrane protein were measured by using the Coomassie protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). All chitin synthase assays were carried out in 50-μl reaction mixtures consisting of 3 μl of 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 3 μl of 40 mM magnesium acetate, 2 μl of 0.8 M GlcNAc (Sigma), 5 μl of 10 mM UDP-N-acetyl-d-[U-14C]glucosamine (specific activity, 271 mCi/mmol; Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) and 10 mM UDP-GlcNAc (Sigma), and 30 μg of membrane protein. For trypsin-activated chitin synthase activity measurements, trypsin (2 μl of 1 mg/ml) from bovine pancreas (type III; Sigma) was added to the membrane preparations, which were subsequently incubated at 30°C for 15 min. Soybean trypsin inhibitor (2 μl of 1.5 mg/ml; Sigma) was then added to terminate trypsin digestion. The mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min, and reactions were stopped by adding 1% trichloroacetic acid (1 ml). After the chitin precipitate was collected by filtration on 25-mm-pore-size glass fiber filters (type A/E; Gelman Science, Ann Arbor, Mich.), the filters were washed with 95% ethanol (5 ml) and radioactivity was counted with a model LS 6800 liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Inc., Irvine, Calif.).

Virulence studies of wdchs4Δ-1 in mice.

Test strains (wdchs4Δ-1, the wild type, and the vector control strain with pAN7) of W. dermatitidis were cultured in 5 ml of YPD overnight at 30°C with shaking. An aliquot of the overnight culture was used to inoculate 50-ml YPD cultures, which were then grown overnight to mid-log phase. Cultures were harvested and washed three times with sterile water. Yeast forms were counted on a hemacytometer and adjusted to a final density of 7 × 107 cells/ml. The virulence of these strains was then tested in a immunocompetent (normal) mouse model system. Male ICR mice (22 to 25 g; Harlan Sprague-Dawley) were housed five per cage; food and water were supplied ad libitum, according to National Institutes of Health guidelines for the ethical treatment of animals. Mice (10 per strain) were inoculated via the lateral tail vein with 100 μl of the cell suspension (7 × 107 cells/ml), such that each mouse received a final dose of 7 × 106 cells. To determine the number of viable yeast forms injected into each mouse, an aliquot of the suspension used for injection was diluted and plated in top agar (0.1% Noble agar) onto YPD plates. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 to 72 h, and percent viability was determined. Mice were checked three times daily for survival or signs of infection. Visible signs of infection were torticollis, ataxia, or lethargy. Infected mice were considered moribund when they were unable to access food or water. Moribund mice were humanely sacrificed by cervical dislocation under anesthesia.

Statistics analysis.

Differences in chitin and chitin synthase activities among groups were evaluated for statistical significance by the parametric one-way analysis of variance Newman-Keuls test for paired data. The analysis was performed with PRISM version 2.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, Calif.). Probability values of <0.05 were considered significant. Survival fractions in virulence tests were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival curves were tested for significant difference (P < 0.01) by the Mantel-Haenszel test using GraphPad Prism version 3.00 for Windows.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the WdCHS4 gene was assigned GenBank accession no. AF126146.

RESULTS

Cloning of the WdCHS4 gene by a marker rescue approach.

The WdCHS4 gene was initially identified as a 366-bp fragment by PCR amplifications (29, 46) using primers based on the conserved sequences of the CHS3 gene of S. cerevisiae, which encodes the class IV isozyme Chs3p in that fungus. Because only an 870-bp fragment of the 3′ end of WdCHS4 gene could be cloned by the library screening approaches used previously for WdCHS1, WdCHS2, and WdCHS3 (31), a marker rescue strategy (27) was used to clone WdCHS4. Plasmid pPCS4 was linearized with EcoRV and then transformed into W. dermatitidis by electroporation. Homologous recombination between the plasmid and the genome resulted in an interrupted repeat that contained one hybrid intact WdCHS4 gene and one hybrid 876-bp sequence (Fig. 1A). Genomic DNA of four transformants digested with BglII and subjected to Southern analysis showed that three had the expected site-specific integration pattern (Fig. 1B). Because Southern blotting suggested that no BglII site was present in the WdCHS4 gene or in pPCS4, a plasmid carrying the WdCHS4 gene was recovered by digestion of genomic DNA of one transformant (Fig. 1B, lane 1) with BglII, followed by ligation, transformation of E. coli XL1-Blue, and selection for chloramphenicol-resistant clones. Two transformants were obtained. The 14-kb plasmid pMRCHS4 from one clone was isolated, and the 5.2-kb WdCHS4 gene was located by restriction enzyme mapping (Fig. 1C).

WdCHS4 is a homolog of CHS3 of S. cerevisiae.

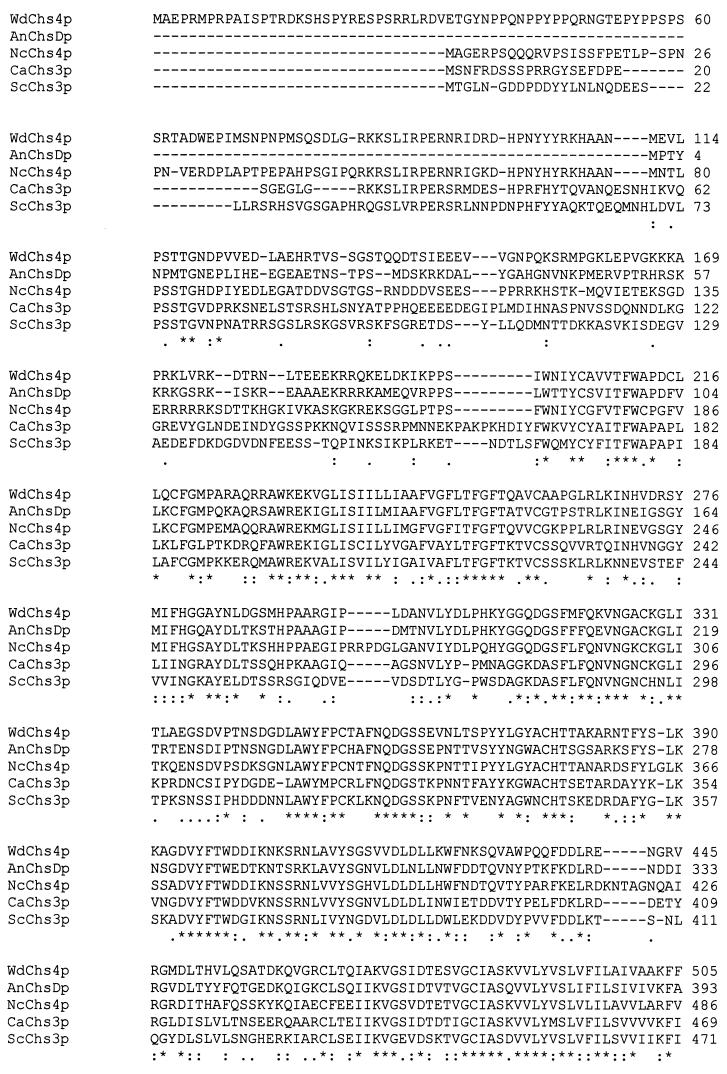

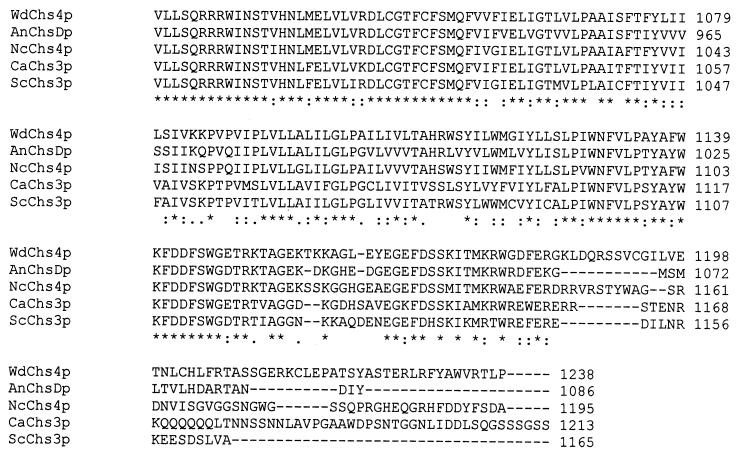

After a series of subclonings, the WdCHS4 gene was completely sequenced. Three in-frame ATGs were found at its 5′ end. Two TA-rich motifs at positions −56 and −20 bp were identified upstream of the first putative translation start site. The deduced 1,238 amino acids, with a calculated mass of 138.8 Kda and a pI of 9.07, encoded by the 3,714-bp open reading frame showed 52.2% identity to Chs3p encoded by CHS3 of S. cerevisiae (9, 57), and 68.8, 68.4, and 54.2% identity to the other class IV chitin synthases encoded by CHS4 of N. crassa (5), CHSD of A. nidulans (40), and CHS3 of C. albicans (53), respectively (Fig. 2). Two highly conserved regions were identified as amino acids 201 to 512 and 664 to 1183. The latter region has homology to corresponding regions in all members of the other classes of chitin synthases and is reported to contain the enzyme's catalytic domain (42). Hydropathy analysis (data not shown) indicated that WdChs4p is a seven-transmembrane protein with hydrophilic regions located near both its amino and carboxyl termini and a neutral region at its center, which are similar to those of other class IV chitin synthases but different from those of other chitin synthase classes. In contrast to the other three WdCHS genes of W. dermatitidis (unpublished data), no evidence for an intron was found in the single open reading frame of WdCHS4. Karyotypic analysis with the wild-type strain (ATCC 34100) and the type strain (ATCC 28869) probed with the WdCHS4 366-bp PCR product showed strong hybridization only with chromosome IV (data not shown), which has an estimated size of 3 to 3.5 Mb and is the smallest of the four chromosomes resolved in both strains (64).

FIG. 2.

Multiple sequence comparison by CLUSTAL analysis of the deduced amino acid sequences of five class IV chitin synthases: WdChs4p, AnChsDp (ChsDp from A. nidulans), NcChs4p (Chs4p from N. crassa), CaChs3p (Chs3p from C. albicans), and ScChs3p (Chs3p from S. cerevisiae). ∗, identical or conserved residue in all sequences in the alignment; :, conserved substitution; ., semiconserved substitution.

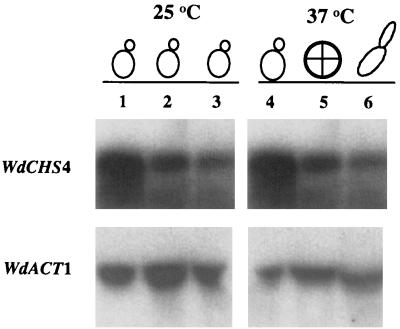

Expression levels of the WdCHS4 gene are not dramatically affected by temperature shift, morphological transition, or disruption of other WdCHS genes.

The two temperature-sensitive morphological mutants of W. dermatitidis, Mc3 (cdc2) and Hf1, convert to isotropic forms and hyphae with thicken cell walls, respectively, when shifted from 25 to 37°C in YPD, whereas the wild-type strain retains its ability to grow as a yeast when cultured identically. Total RNA extracted from these strains, grown at 25 and 37°C for 24 h, was subjected to Northern analysis using a 0.8-kb BamHI fragment of WdCHS4 as a probe. A single transcript of about 3.7 kb was detected in each strain cultured at both temperatures, and no dramatic increase in transcription level was apparent in cells of the same strain shifted from 25 to 37°C, using actin expression levels as controls (Fig. 3). Total RNA of the other chitin synthase single gene disruption strains, the wdchs1Δ, wdchs2Δ, and wdchs3Δ mutants (31, 58, 63), was also probed by Northern blotting (data not shown). The transcription levels of WdCHS4 in all of these single wdchsΔ strains were similar to that in the wild type, indicating that defects in other chitin synthase genes in W. dermatitidis did not significantly affect the expression level of WdCHS4. These data further suggested that neither the shift of these strains to high temperature nor the transitions of yeast cells to other vegetative phenotypes dramatically affected WdCHS4 transcription.

FIG. 3.

Northern blot analysis of WdCHS4 expression. Total RNA (20 μg) was prepared from wild-type W. dermatitidis 8656 (lanes 1 and 4) and the temperature-sensitive morphological mutants Mc3 (lanes 2 and 5) and Hf1 (lanes 3 and 6) grown at 25 and 37°C, respectively, for 24 h and electrophoresed in a formaldehyde-containing 1.2% agarose gel before transfer to a nylon membrane. The membrane was probed with a 32P-labeled 0.8-kb BamHI fragment of WdCHS4 and a 0.6-kb PCR fragment of the actin gene (WdACT1) of W. dermatitidis, as indicated.

The WdCHS4 gene is not essential for W. dermatitidis viability.

Using a strategy similar to that used to clone WdCHS4, we used plasmid pDCS4, which contains an 800-bp BamHI fragment of WdCHS4, to disrupt this gene in such a way that site-specific integration at the wdchs4 locus by homologous recombination would result in two truncated fragments of WdCHS4 separated by the vector sequence and the hph gene (Fig. 4A). Total DNA from three transformants obtained on YPD-HmB medium was digested with ApaI or SacI and then subjected to Southern blotting using a WdCHS4 BamHI 0.8-kb fragment as a probe. The expected band shifts from 6.0 to 11.8 kb with ApaI-digested DNA and from 3.5 to 9.3 kb with SacI-digested DNA confirmed that these transformants were WdCHS4 disruptants (Fig. 4B; data only for wdchs4Δ-1 are shown). Northern blotting also indicated that the 3.6-kb transcript shifted to the higher-molecular-weight position in the wdchs4Δ disruption strain (data not shown). Disruption of WdCHS4 was also achieved by using plasmid pHY1, which contained the same WdCHS4 800-bp fragment but with the sulfonyl urea resistance gene marker. Southern blotting proved that at least one viable sulfonyl urea-resistant WdCHS4 disruption strain has also been obtained, which was named wdchs4Δ (sur) (62a).

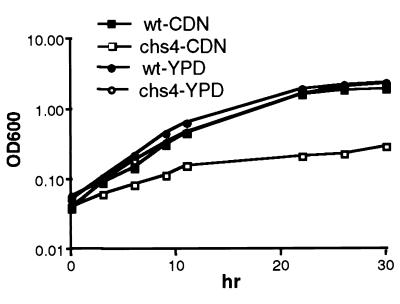

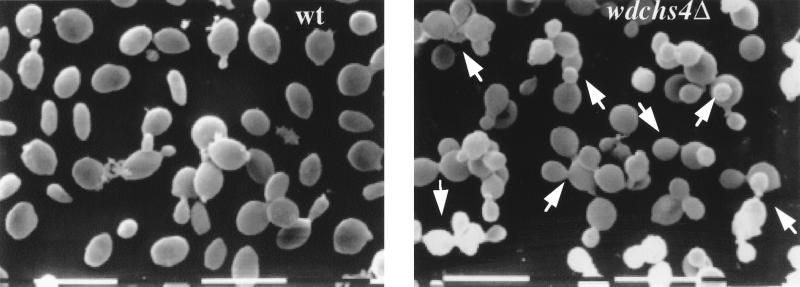

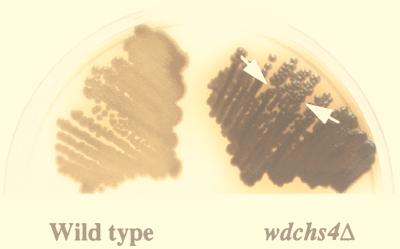

The wdchs4Δ-1 disruptant strain grows slowly in poor medium and shows abnormal yeast clumping, budding kinetics, and pigmentation.

At 25°C, the growth rates of wdchs4Δ-1 and wild-type strains were similar in both broth YPD and CDN media (data not shown). At 37°C, the growth rate of wdchs4Δ-1 was close to that of the wild type in YPD but significantly lower than that of the wild type in CDN medium (Fig. 5), suggesting that WdChs4p makes a significant contribution to the rate of cell growth in W. dermatitidis under some nutrient-poor growth conditions. The wdchs4Δ-1 cells were also observed by light microscopy to have a clumping tendency and a higher density (they tended to settle faster than the wild type) at both 25 and 37°C when cultured in liquid medium (data not shown). Although calcofluor staining for chitin and fluorescence microscopy showed no obvious differences in cell wall and septal regions between wdchs4Δ-1 and its wild-type parent, a larger population of the multiply budding yeast cells was detected among the disruptant cells in CDN medium at 37°C (Table 1). Scanning electron microscopy showed that the wdchs4Δ-1 cells not only tended to clump but also had abnormal multiple budding patterns among cells cultured in CDN at 37°C (Fig. 6). Furthermore, it was noted that colonies of the disruption strain grown on agar (Fig. 7), as well as cells cultured in liquid medium and culture supernatant fluids after centrifugation (data not shown), were darker than those of the wild-type strain after growth for only a few days at 25 or 37°C, indicating that more melanin was being incorporated into their cell walls and being leaked from the wdchs4Δ-1 disruptant cells. However, the darker wdchs4Δ-1 strain could not cross-feed the white melanin-deficient wdpks4Δ-1 mutant (data not shown) in which the polyketide synthase gene was disrupted (23a), indicating that pigmented molecules secreted from this mutant were not precursors of melanin polymers but were probably polymerized melanin itself. Similar, if not identical, abnormal phenotypes have been observed with all other wdchs4Δ strains, including the wdchs4Δ (sur) strain, although none of these strains have been characterized to the same extent as wdchs4Δ-1. Finally, no significant (P > 0.01) differences in survival rates were detected in immunocompetent 4-week-old ICR mice inoculated intravenously with the wild-type strain, a vector control strain with pAN7-1 integrated ectopically, or the wdchs4Δ-1 mutant (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Comparison of the growth rates at 37°C of W. dermatitidis 8656 (wild type [wt]) and its wdchs4Δ-1 mutant (chs4) in YPD or CDN medium. Late log-phase cultures were transferred to YPD or CDN medium to the final optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.06 (measured with a Beckman model 25 spectrophotometer). Cells were grown at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Results shown are the average of two independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

Comparisons of yeast cell morphologies of wild-type and wdchs4Δ-1 strains

| Strain | Mean % of different

morphologies ± SEM

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unbudded | Singly budded | Multiply budded | |

| Wild type | 57.6 ± 3.28 | 37.0 ± 3.87 | 5.4 ± 1.14 |

| wdchs4Δ | 23.4 ± 5.13 | 53.8 ± 6.30 | 22.6 ± 3.72 |

FIG. 6.

Scanning electron micrograph showing morphology of wild-type (wt) and wdchs4Δ-1 cells grown in CDN liquid medium at 37°C for 24 h. Arrows point to multiple budding yeast cells. Bars, 10 μm.

FIG. 7.

Growth of wild-type and wdchs4Δ-1 strains on YPD agar medium incubated at 37°C for 4 days. Colonies of the wdchs4Δ-1 strain are darker than those of the wild type. Arrows point to zones in the YPD agar where melanin has accumulated.

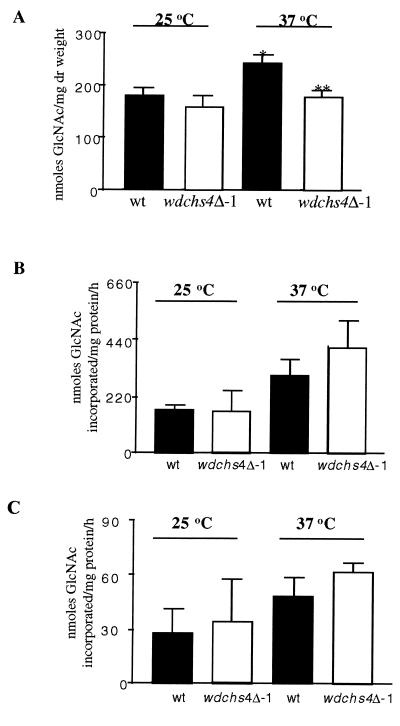

Chitin content, but not chitin synthase activity, is reduced in the wdchs4Δ-1 disruptant at 37°C.

The chitin content of wdchs4Δ-1 was found to be significantly less than that of the wild-type strain at 37°C, but not at 25°C (Fig. 8A). This result was the first indication that any wdchsΔ in W. dermatitidis could be correlated with a significant reduction in cell wall chitin (references 58 and 63 and this work). Apparently our current chitin assay method is not sensitive enough to detect minor changes, if they exist, in the chitin contents of the wdchs4Δ-1 mutant at 25°C or in other single wdchs1Δ, wdchs2Δ, and wdchs3Δ mutants at either 25 or 37°C. Surprisingly, however, the chitin synthase activity in the wdchs4Δ-1 strain did not decrease like that of the other wdchs disruption mutants grown identically (58, 63), but instead exhibited a consistent minor but not statistically significant increase under the 37°C growth condition (Fig. 8B and C). These contradictory data from assaying chitin contents and chitin synthase activities may reflect that other chitin synthases compensate for the loss of WdChs4p.

FIG. 8.

(A) Comparison of chitin contents of the wild type (wt) and wdchs4Δ-1 mutant incubated at 25 and 37°C. Results are derived from three independent experiments. Standard deviations are shown. The significantly different (P < 0.05) chitin content between the wild-type strain grown at 25 and at 37°C is indicated by a single asterisk, whereas significant difference (P < 0.05) between the wild-type and wdchs4Δ-1 strains at 37°C is indicated by two asterisks. (B and C) WdChs activities of the wild type and wdchs4Δ-1 mutant incubated at 25 or 37°C and assayed with (B) or without (C) trypsin treatment. Results for each treatment are derived from three independent experiments. Standard deviations are shown. No significantly different (P > 0.05) activities were found between the wild-type and wdchs4Δ-1 strains at each temperature.

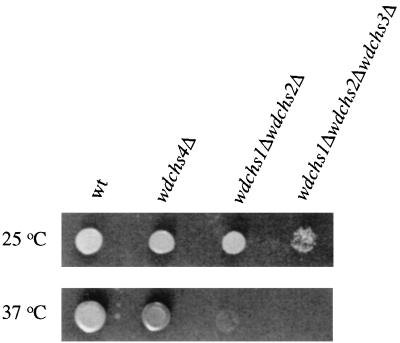

WdChs4p is characterized in the wdchs1Δ wdchs2Δ wdchs3Δ triple mutant.

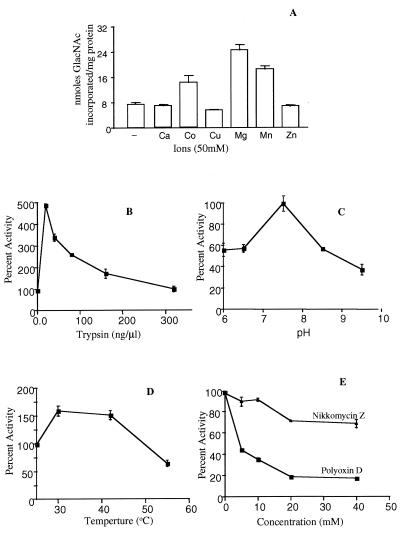

Using three different selective markers, we obtained the wdchs1Δ, wdchs2Δ, wdchs3Δ triple mutant through three consecutive disruptions (63). Although this mutant grew much less vigorously, had an obviously abnormal phenotype compared to the wild-type or even the wdchs4Δ-1 mutant, and would not grow at all at 37°C, adequate growth could be obtained at 25°C (Fig. 9) for WdChs4p assays: since all four chitin synthase structural genes are thought to have been identified in W. dermatitidis, WdChs4p was regarded as the only chitin synthase present in this triple mutant, and thus its activity could be characterized directly in membrane protein samples by biochemical assay. Compared with the total chitin synthase activities of the wild type and the wdchs4Δ-1 mutant (Fig. 8B), WdChs4p activity in the triple mutant was very low (Fig. 10A). As expected, it could be activated by trypsin treatment (Fig. 10B), indicating that although WdChs4p was a zymogen, it did not contribute the majority of chitin synthase activity in vitro. As also expected, certain divalent cations were found to be required for stimulating the activity of the trypsin-treated membranes above basal levels. Among the six cations examined, Mg2+ was more effective than either Co2+ or Mn2+ for stimulating WdChs4p activity, whereas Ca2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ were ineffective (Fig. 10A). Although the pH profile was found to be stringent for WdChs4p, with the optimal pH for maximal activity determined to be 7.5 (Fig. 10C), WdChs4p had lower activity at 25°C and a broad temperature tolerance, from 30 to 45°C (Fig. 10D). Moreover, WdChs4p was demonstrated to be more sensitive in vitro to polyoxin D than to nikkomycin Z (Fig. 10E), which are two antifungal agents that are known to competitively inhibit chitin synthases (16).

FIG. 9.

Temperature sensitivity test for the wild-type (wt) and wdchs4Δ-1, wdchs1Δwdchs2Δ and wdchs1Δwdchs2Δwdchs3Δ mutant strains. The strains were grown on YPD plates at 25 and 37°C, as indicated, for 3 days.

FIG. 10.

Biochemical characteristics of WdChs4p activity of membranes from the wdchs1Δ chs2Δ chs3Δ triple mutant. Membrane proteins were isolated from mutant cells grown in YPD liquid medium at 25°C for 40 h. The results were derived from two independent experiments, and the assay of each sample was duplicated. Standard deviations are shown.

DISCUSSION

Although a PCR fragment homologous to CAL1, the class IV chitin synthase-encoding gene of S. cerevisiae had been identified in W. dermatitidis some time ago (29, 46), the full-length WdCHS4 gene was resistant to cloning by the library screening approaches used for WdCHS1, WdCHS2, and WdCHS3. Therefore, a gene marker rescue approach involving transformation was used to clone this gene. One advantage of this method was that once a fragment of WdCHS4 was obtained, it was easily integrated with a shuttle vector into its endogenous genomic locus by homologous recombination, and then regions both upstream and downstream were recovered by selectively digesting genomic DNA, transforming it into E. coli, and isolating replicative plasmids. A second advantage was that the two truncated gene copies derived from this integration resulted in a gene disruption. Thus, insights into the function of the tagged gene were obtained even before the gene was cloned.

The deduced WdCHS4 gene product was found to have most homology to the class IV chitin synthases of the filamentous fungi N. crassa (5) and A. nidulans (40) and less homology to those of the yeast species S. cerevisiae (9, 57) and C. albicans (53), confirming again that the essentially filamentous, but polymorphic, asexual fungus W. dermatitidis is more closely related to filamentous ascomycetes than to known or suspected yeast ascomycete species (7, 29). Unlike members of other classes, which have four transmembrane domains at C-terminal regions, WdChs4p has seven transmembrane domains distributed at both ends of the protein and between which are located putative catalytic regions. It also has a unique N-terminal region, as is common to all class IV chitin synthases characterized to date, including Chs3p of S. cerevisiae.

The wdchs4Δ-1 strain is the only wdchs disruption mutant detected to have a significantly reduced chitin content at 37°C according to our current measurement protocols, indicating that WdChs4p makes more chitin in W. dermatitidis, at least at 37°C, than do the other isozymes. This is in agreement with the finding that the class IV chitin synthase of S. cerevisiae is the major producer of chitin in that fungus (9). Moreover, the clumping tendency and the multiple budding of the yeast cells of all the wdchs4Δ mutants were similar to the phenotype reported for the CAL1 mutants of S. cerevisiae (50). We suspect that this phenotype is indicative of structural changes in cell wall and in septal regions, although aberrant septation was not revealed by calcofluor staining. Also, the increased melanin released from wdchs4Δ cells suggests that melanin might normally be deposited in the chitin matrix synthesized by WdChs4p. In this respect, we hypothesize that melanin in W. dermatitidis is bound or trapped by the cell wall matrix contributed by WdChs4p but is not retained as efficiently in the cell walls of wdchs4Δ mutants. Alternatively, the regulation of the melanin biosynthesis pathway might be related to chitin synthesis. In this scenario, the chitin in the cell wall synthesized by WdChs4p might inhibit melanin synthesis by a feedback regulation mechanism.

Total chitin synthase activity in the wdchs4Δ-1 mutant did not show significant changes compared to that of the wild type, which is similar to the situation with wdchs1Δ mutants (63) but not of wdchs2Δ or wdchs3Δ mutants (58). This may be due to the fact that four classes of chitin synthases have been identified in W. dermatitidis (31, 56). Possibly one or all of the other chitin synthases, and most likely WdChs2p, which is a class I chitin synthase and contributes most of the zymogenic activity associated with membranes of W. dermatitidis (63, 64), compensates for the lost WdChs4p activity when WdCHS4 is deleted. Alternatively, the lost WdChs4p activity is possibly compensated for by WdChs3p activity, which is induced to higher levels of production at 37°C (58). Finally, this paradox might simply be explained by the minor amount of chitin synthase activity contributed by WdChs4p in the wild-type strain, which could not be shown to be reduced significantly in the wdchs4Δ-1 strain. Evidence for a low level of activity of WdChs4p comes from studies of the wdchs triple mutant, which has about 10-fold-lower total activity per milligram membrane protein than the wild-type strain (compare data in Fig. 10A with those in Fig. 8B).

During the polymorphic transitions of W. dermatitidis, the transcription levels of WdCHS4 did not appear to change significantly in comparisons between cells of the same strain shifted to 37°C, even though significantly more chitin is deposited in the cell walls of the multicellular forms and hyphae (19, 26, 54). The expression level of WdCHS4 was also similar to the wild-type level in the wdchs1Δ, wdchs2Δ, and wdchs3Δ strains grown under standard growth conditions (58a). Thus, the expression of this gene is probably constitutive during polymorphic growth, even in the absence of one or another single chitin synthase. These particular results argue against the possibility introduced above, that the disruption of WdCHS4 might induce a higher expression of other WdCHS genes for compensation, and instead suggest that WdChs4p, like Chs3p in S. cerevisiae (15), is regulated at the translational or posttranslational level. However, it is still very possible that the expression levels of WdCHS4 are correlated with specific events associated with yeast cell cycle progression, particularly the event of septation, which is a possibility not addressed in this study.

The successful use of multiple selective markers in our WdCHS gene disruption experiments (31) allowed us to eliminate the three other WdCHS genes in W. dermatitidis, which in turn permitted the measurement of only the class IV chitin synthase activity of WdChs4p. The protein responsible for this activity was directly determined to be a zymogen, which could be activated in vitro when treated with trypsin, even without the protection of substrate UDP-GlcNAc. Our direct assay of the WdChs4p activity also revealed its remarkable preference for certain divalent ions, suggesting that metal ions are essential and specific for chitin synthase activity in vitro: the higher efficiency of Mg2+ to stimulate the enzyme activity versus that of Co2+ suggests that the binding of Mg2+ was stronger than that of Co2+, which is in agreement with the study of Chs3p of S. cerevisiae (57). The optimal pH (pH 7.5) of WdChs4p was also similar to Chs3p of yeast. However, the broad temperature optimum for WdChs4p activity, unlike that for Chs3p (25°C) (10), which is probably a reflection of the thermotolerance known to be associated with W. dermatitidis, may suggest that this enzyme is particularly well suited for functioning at the higher temperatures associated with its poorly characterized saprophic environment and with human infection. Like the other chitin synthases of S. cerevisiae, WdChs4p was also sensitive to polyoxin D and nikkomycin Z in vitro, indicating that this chitin synthase shares domains that can be targeted by these and other drugs.

The disruption of WdCHS4 produced cells that showed no significant reduction in virulence in an acute mouse model. We speculate that this absence of virulence loss after the disruption of WdCHS4 is because its product, WdChs4p, is not a particularly important contributor of the specific chitin(s) required for the survival and growth of W. dermatitidis at temperature of infection. This speculation is based on our observations that the wdchs1Δ wdchs2Δ wdchs3Δ triple mutant of this pathogen, which presumably has only WdChs4p activity, grew at 25°C (albeit poorly) but not at 37°C, even though chitin synthase activity could be measured in vitro over a broad temperature range, including 37°C. Possibly at temperatures of infection, the WdChs4p zymogen is not activated in vivo or, if activated, does not function efficiently enough to compensate for the loss of the chitin contributed normally by one or more of the other chitin synthases. We further speculate that the chitin contributed by WdChs4p is not localized to positions in cells necessary to compensate for the loss of the chitin products of other chitin synthases of W. dermatitidis, which are most important for normal yeast growth. We base this suggestion on our observation in this and other studies (63) that the cells of the triple mutant that survive at 25°C, like those of the wdchs1Δ wdchs2Δ double mutant, are very swollen, multinucleate, largely inhibited in cell separation, and defective in normal septum formation (reference 63 and results to be reported elsewhere). In contrast, as shown in the present work, the disruption of WdCHS4 alone results in only relatively minor perturbations, which although more pronounced at 37°C are mainly manifested by clumpiness, multiple budding, and slower growth in poor but not rich medium, none of which should significantly alter virulence in the rich environments associated with most infections. Thus, additional similar studies, involving the cloning and disruption of each of the other WdCHS genes of W. dermatitidis individually and in as many combinations as possible, are required before the contributions of each of their products to saprophytic and parasitic growth and survival of this pathogen can be satisfactorily defined. Such studies are in progress and are at very advanced stages (31, 58, 63, 64).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. M. Karuppayil and B. Feng for supplying PCR fragments of the WdCHS4 gene, Z. Yin for helping with the pulsed-field electrophoresis, C. R. Cooper, Jr., for the use of a CHEF gel apparatus, W. Chen for supplying the WdACT1 gene used for a probe in Northern analysis, P. McIntosh for help with scanning electron microscopy, and H. Yarbrough for constructing and characterizing wdchs4Δ (sur) mutant.

This work was supported by grant AI 33049 to P.J.S. from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aufauvre-Brown A, Mellado E, Gow N A R, Holden D W. Aspergillus fumigatus chsE: a gene related to CHS3 of Saccharomyces cerevisiaeand important for hyphal growth and conidiophore development but not pathogenicity. Fungal Genet Biol. 1997;21:141–152. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1997.0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Bent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartnicki-Garcia S, Reyes E. Chemical composition of sporangiophore walls of Mucor rouxii. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1968;165:32–42. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(68)90185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell A A, Wheeler M H. Biosynthesis and functions of fungal melanins. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1986;24:411–451. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beth Din A, Specht C A, Robbins P W, Yarden O. chs-4, a class IV chitin synthase gene from Neurospora crassa. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;250:214–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02174181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boas N F. Method for the determination of hexosamines in tissues. J Biol Chem. 1953;204:553–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowen A R, Chen-Wu J L, Momany M, Young R, Szaniszlo P J, Robbins P W. Classification of fungal chitin synthases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:519–523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun P C, Calderone R A. Chitin synthesis in Candida albicans: comparison of yeast and hyphal forms. J Bacteriol. 1978;135:1472–1477. doi: 10.1128/jb.133.3.1472-1477.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulawa C E. CSD2, CSD3, and CSD4 genes required for chitin synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the CSD2 gene product is related to chitin synthases and to developmentally regulated proteins in Rhizobium species and Xenopus laevis. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1764–1776. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulawa C E. Genetics and molecular biology of chitin synthase in fungi. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:505–534. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.002445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulawa C E, Slater M, Cabib E, Au-Young J, Sburlati A, Adair W L, Robbins P W. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae structural gene for chitin synthase is not required for chitin synthase in vivo. Cell. 1986;46:213–215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90738-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cabib E, Silverman S J, Sburlati A, Slater M L. Chitin synthesis in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) In: Kuhn P J, Trinci A P J, Jung M J, Goosey M W, Copping L G, editors. Biochemistry of cell wall and membranes in fungi. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll A M, Sweigard J A, Valent B. Improved vectors for selecting resistance to hygromycin. Fungal Genet Newsl. 1994;41:22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassone A. Cell wall of pathogenic yeasts and implication for antimycotic therapy. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1986;12:635–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi W, Santos B, Duran A, Cabib E. Are yeast chitin synthases regulated at the transcriptional or the posttranscriptional level. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7685–7694. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.7685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cid V J, Duran A, del Rey F, Synder M P, Nombela C, Sanchez M. Molecular basis of cell integrity and morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:345–386. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.345-386.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole G T. Preparation of microfungi for scanning electron microscopy. In: Aldrich H C, Todd W J, editors. Ultrastructure techniques for microorganisms. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper C R, Jr, Szaniszlo P J. Evidence for two cell division cycle (CDC) genes that govern yeast bud emergence in the pathogenic fungus Wangiella dermatitidis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2069–2081. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2069-2081.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper C R, Jr, Harris J L, Jacobs C W, Szaniszlo P J. Effects of polyoxin on cellular development in Wangiella dermatitidis. Exp Mycol. 1984;8:349–363. [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Hoog G S, Takeo K, Yoshida S, Gottlich E, Nishimura K, Miyaji M. Pleoanamorphic life cycle of Exophiala (Wangiella) dermatitidis. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1994;65:143–153. doi: 10.1007/BF00871755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dixon D M, Polak A, Szaniszlo P J. Pathogenicity and virulence of wild-type and melanin-deficient Wangiella dermatitidis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1991;25:97–106. doi: 10.1080/02681218780000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixon D M, Szaniszlo P J, Polak A. Dihydroxynaphthalene (DHN) melanin and its relationship with virulence in the early stages of phaeohyphomycosis. In: Cole G T, Hoch H C, editors. The fungal spore and disease initiation in plants. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 297–318. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dixon D M, Migliozzi J, Cooper C R, Solis O, Breslin B, Szaniszlo P J. Melanized and non-melanized multicellular form mutants of Wangiella dermatitidisin mice: mortality and histopathology studies. Mycoses. 1992;35:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1992.tb00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Feng, B., and P. J. Szaniszlo. Unpublished data.

- 24.Geis P A, Jacobs C W. Polymorphism of Wangiella dermatitidis. In: Szaniszlo P J, editor. Fungal dimorphism: with emphasis on fungi pathogenic for humans. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1985. pp. 205–233. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gooday G W, Gow N A R. Enzymology of tip growth in fungi. In: Health I B, editor. Tip growth in plant and fungal cells. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris J L, Szaniszlo P J. Localization of chitin in walls of Wangiella dermatitidisusing colloidal gold-labeled chitinase. Mycologia. 1986;78:853–857. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung M K, Oakley B R. Identification of an amino acid substitution in the benA, β-tubulin gene of Aspergillus nidulansthat confers thiabendazole resistance and benomyl supersensitivity. Cell Motil Cytoskel. 1990;17:87–94. doi: 10.1002/cm.970170204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karuppayil S M, Szaniszlo P J. Importance of calcium to the regulation of polymorphism in Wangiella (Exophiala) dermatitidis. J Vet Med Mycol. 1997;35:379–388. doi: 10.1080/02681219780001471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karuppayil S M, Peng M, Mendoza L, Levins T A, Szaniszlo P J. Identification of the conserved coding sequence of three chitin synthase genes in Fonsecaea pedrosoi. J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34:117–125. doi: 10.1080/02681219680000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwon-Chung K J, Bennet J E. Medical mycology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea and Febiger; 1992. pp. 337–555. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwon-Chung K J, Goldman W E, Klein B, Szaniszlo P J. Fate of transforming DNA in pathogenic fungi. Med Mycol. 1998;36(Suppl. I):38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsumoto T, Matsuda T, McGinnis M R. Clinical and mycological spectra of Wangiella dermatitidis. Mycoses. 1993;36:145–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1993.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellado E, Aufauvre-Brown A, Specht C A, Robbins P W, Holden D W. A multigene family related to chitin synthase genes of yeast in the opportunistic pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;246:353–359. doi: 10.1007/BF00288608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellado E, Aufauvre-Brown A, Gow N A R, Holden D W. The Aspergillus fumigatus chsC and chsGgenes encode class III chitin synthases with different functions. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:667–679. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5571084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mellado E, Specht C A, Robbins P W, Holden D W. Cloning and characterization of chsD, a chitin synthase-like gene of Aspergillus fumigatus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;143:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mendoza A L. Cloning and molecular characterization of the chitin synthase 1 (WdCHS1) gene of Wangiella dermatitidis. Ph.D. thesis. The University of Texas at Austin; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mio T, Yabe T, Sudoh M, Satoh Y, Nakajima T, Arisawa M, Yamada-okabe H. Role of three chitin synthase genes in the growth of Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2416–2419. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2416-2419.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molano J, Bowers B, Cabib E. Distribution of chitin in the yeast cell wall: an ultrastructural and chemical study. J Cell Biol. 1980;85:199–212. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Momany M, Szaniszlo P J. DNA isolation from Wangiella. In: Maresca B, Kobayashi G S, editors. Molecular biology of pathogenic fungi—a laboratory manual. New York, N.Y: Telos Press; 1994. pp. 519–520. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Motoyama T, Fujiwara M, Kojima N, Horiuchi H, Ohta A, Takagi M. The Aspergillus nidulans genes chsA and chsDencode chitin synthases which have redundant functions in conidia formation. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;251:442–450. doi: 10.1007/BF02172373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nachman S A, Alpan O, Malowitz R, Spitzer E D. Catheter-associated fungemia due to Wangiella (Exophiala) dermatitidis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1011–1013. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.1011-1013.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagahashi S, Sudoh M, Ono N, Saweda R, Yamaguchi E, Uchida Y, Mio T, Tagaki M, Arisawa M, Yamada-Okabe H. Characterization of chitin synthase 2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Implication of two highly conserved domains as possible catalytic sites. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13961–13967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orlean P. Two chitin synthases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5732–5739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orlean P. Yeast III. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 229–362. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng M, Cooper C R, Jr, Szaniszlo P J. Genetic transformation of the pathogenic fungus Wangiella dermatitidis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;44:444–450. doi: 10.1007/BF00169942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peng M, Karuppayil S M, Mendoza L, Levins T A, Szaniszlo P J. Use of the polymerase chain reaction to identify coding sequences for chitin synthase isozymes in Phialophora verrucosa. Curr Genet. 1995;27:517–523. doi: 10.1007/BF00314441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roberts R L, Bowers B, Slater M L, Cabib E. Chitin synthesis and localization in cell division cycle mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:922–930. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.5.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schnitzler N, Peltroche-Llacsahuanga H, Bestier N, Zundorf J, Lutticken R, Haase G. Effect of melanin and carotenoids of Exophala (Wangiella) dermatitidison phagocytosis, oxidative burst, and killing by human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1999;67:94–101. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.94-101.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sentandreu R, Hettero E, Martinez-Garcia J P, Larriba G. Biogenesis of the yeast cell walls. In: Roodyn D B, editor. Subcellular biochemistry. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1989. pp. 193–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shaw J A, Mol P C, Bowers B, Silverman S J, Valdivieso M H, Duran A, Cabib E. The function of chitin synthases 2 and 3 in the Saccharomyces cerevisiaecell cycle. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:111–123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silverman S J, Sburlati A, Slater M L, Cabib E. Chitin synthase 2 is essential for septum formation and cell division in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4735–4739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Specht C A, Liu Y, Robbins P W, Bulawa C E, Iartchouk N, Winter K R, Riggle P J, Rhodes J C, Dodge C L, Culp D W, Borgia P T. The chsD and chsE genes of Aspergillus nidulansand their roles in chitin synthesis. Fungal Genet Biol. 1996;20:153–167. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sudoh M, Nagahashi S, Doi M, Ohta A, Takagi M, Arisawa M. Cloning of the chitin synthase 3 gene from Candida albicansand its expression during yeast-hyphal transition. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;241:351–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00284688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Szaniszlo P J, Jacobs C W, Geis P A. Dimorphism: morphological and biochemical aspects. In: Howard D H, editor. Fungi pathogenic for humans and animals, part A. Biology. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1983. pp. 323–426. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Szaniszlo P J, Mendoza L, Karuppayil S M. Clues about chromoblastomycotic and other dematiaceous fungal pathogens based on Wangiella as a model. In: Vanden Bossche H, Odds F C, Kerridge D, editors. Dimorphic fungi in biology and medicine. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 241–255. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Szaniszlo P J, Momany M. Chitin, chitin synthase and chitin synthase conserved region homologues in Wangiella dermatitidis. In: Maresca B, Kobayashi G, Yamaguchi H, editors. NATO ASI series. H69. Molecular biology and its application to medical mycology. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1993. pp. 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Valdivieso M H, Mol P C, Shaw J A, Cabib E, Duran A. Cloning of CAL1, a gene required for activity of chitin synthase 3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:101–109. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Z. Cloning and characterization of the chitin synthase 3 (WdCHS3) and chitin synthase 4 (WdCHS4) genes of Wangiella dermatitidis and expression studies of WdCHS3. Ph.D. thesis. The University of Texas at Austin; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 58a.Wang, Z. Unpublished data.

- 59.Wessels J G H. Cell wall synthesis in apical hyphal growth. Int Rev Cytol. 1986;104:38–79. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yabe T, Yamada-Okabe T, Kasahara S, Furuichi Y, Nakajima T, Ichishima E, Arisawa M, Yamada-Okabe H. HKR1 encodes a cell surface protein that regulates both cell wall β-glucan synthesis and budding pattern in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:477–483. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.477-483.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yanai K, Kojima N, Takaya N, Horiuchi H, Ohta A, Takagi M. Isolation and characterization of two chitin synthase genes from Aspergillus nidulans. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58:1828–1835. doi: 10.1271/bbb.58.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yarden O, Yanofsky C. Chitin synthase 1 plays a major role in cell wall biogenesis in Neurospora crassa. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2420–2430. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12b.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62a.Yarbrough, H., and P. J. Szaniszlo. Unpublished data.

- 63.Zheng L. Establishment of genetic transformation systems in and molecular cloning of the chitin synthase 2 (WdCHS2) gene, and characterization of the WdCHS1 and WdCHS2 genes of Wangiella dermatitidis. Ph.D. thesis. The University of Texas at Austin; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zheng L, Szaniszlo P J. Cloning and use of the WdURA5 gene as a hisG cassette selection marker for potentially disrupting multiple genes of Wangiella dermatitidis. Med Mycol. 1999;37:85–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]