Abstract

Military parents’ combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms have been linked to poor parenting and child maladjustment. Emotion regulation (ER) difficulties are thought to underlie PTSD symptoms, and research has begun to link parental ER to parenting behaviors. Little empirical evidence exists regarding whether fathers’ ER is associated with child adjustment and what may be the underlying mechanism for this association. This study investigated whether deployed fathers’ ER was associated with child emotional and behavioral problems, and whether the associations were mediated by coercive parenting behaviors. The sample consisted of 181 deployed fathers with non-deployed female partners and their 4- to 13-year-old children. Families were assessed at three time points over 2 years. ER was measured using a latent construct of fathers’ self-reports of their experiential avoidance, trait mindfulness, and difficulties in emotion regulation. Coercive parenting was observed via a series of home-based family interaction tasks. Child behaviors were assessed through parent- and child-report. Structural equation modeling revealed that fathers with poorer ER at baseline exhibited higher coercive parenting at 1-year follow-up, which was associated with more emotional and behavioral problems in children at 2-year follow-up. The indirect effect of coercive parenting was statistically significant. These findings suggest that fathers’ difficulties in ER may impede their effective parenting behaviors, and children’s adjustment problems might be amplified as a result of coercive interactions. Implications for the role of paternal ER on parenting interventions are discussed.

Keywords: Coercive Parenting, Emotion Regulation, Military Fathers, Internalizing behavior problems, Externalizing behavior problems

Since 2001, nearly three million U.S. service members have been deployed to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and about half of them are parents (U.S. Department of Defense, 2016). Parental military deployment is a substantial source of stress for families because of the deployed parent’s prolonged absence from the family, the increased caregiving responsibility for the at-home parent, and family members’ worries about the safety of the deployed parent. Further stressors can arise if deployed family members experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, depression, or physical injuries after deployment (Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, 2006). Research has suggested that combat deployment and exposure to traumatic events impair service members’ emotion regulation capacities (i.e., the ability to modulate the experience of emotions in accordance with desired goals; Cole, Michel, & Teti, 1994; Monson, Price, Rodriguez, Ripley, & Warner, 2004; Thompson, 1994), and poor emotion regulation is considered an important factor in the development and maintenance of PTSD and other psychopathology such as anxiety and depressive disorders (Kashdan, Morina, & Priebe, 2009; Seligowski, Lee, Bardeen, & Orcutt, 2015). Following reintegration, parental impairments in emotion regulation may negatively affect children’s adjustment (Gewirtz & Davis, 2014; Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007) through processes such as coercive parenting (i.e., aversive behavior, negative reinforcement, and emotional escalations in parent-child interactions; Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989; Snyder et al., 2013). For example, reintegrating parents may become dysregulated by emotionally-laden parent-child interactions (e.g., child disruptive behavior) and respond aggressively or coercively (DeGarmo, Nordahl, & Fabiano, 2015; Snyder et al., 2016). Although extensive prior research has examined the link between coercive parenting and child adjustment (Snyder, 2016), fewer studies have examined whether and how parental emotion regulation – a key factor that supports parenting behaviors – might be associated with child adjustment over time. The goal of the current paper is to test this association in a sample of post-deployed National Guard/Reserve military fathers and their children, as well as to examine whether coercive parenting mediates the relationship, using multi-method, multi-informant longitudinal data.

Parental emotion regulation and child adjustment

Emotion regulation operates on both intrapersonal and interpersonal levels of functioning (Zaki, & Williams, 2013). The current study focuses on intrapersonal ER which indicates the degree to which individuals are aware of their emotions and are able to effectively regulate them. There is growing consensus that emotion regulation plays a central role in a variety of mental health problems (Werner, & Gross, 2010). For example, in the trans-diagnostic framework presented by the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), emotion regulation has been proposed as one of several core Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) underlying psychopathology (Fernandez, Jazaieri,& Gross, 2016).

Emotion regulation involves multifaceted experiential and behavioral processes. In the context of combat deployment, what may be particularly pertinent are the emotion regulation processes related to PTSD. In this study, we were interested in both negative and positive aspects of emotion regulation relevant to military personnel exposed to war. One negative aspect of emotion regulation is experiential avoidance, a core feature in PTSD, which reflects habitual attempts to control or disengage from painful inner experiences such as bodily sensations, memories (Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, & Strosahl, 1996). The ultimate goal of experiential avoidance (i.e., lack of psychological flexibility) is to minimize contact with one’s feelings and experiences, which may lead to limited opportunities to modify one’s belief about potential threat and danger (Kashdan, Breen, & Julian, 2010). Experiential avoidance has been linked to emotion dysregulation in populations exposed to trauma (Boden et al., 2013; Shepherd & Wild, 2014). In contrast, trait mindfulness, which is the tendency to attend to moment-to-moment experiences with acceptance and nonjudgment, reflects the intentional regulation of inner experiences and openness to negative feelings and thoughts (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007). Trait mindfulness has been consistently documented as an important aspect of adaptive emotion regulation (Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, 2009; Kabat-Zinn, 2003). The link between mindful awareness and non-judging with PTSD has been found among combat veterans (Wahbeh, Lu, & Oken, 2011). Therefore, we incorporated experiential avoidance and mindfulness in our conceptual framework and measurement of emotion regulation.

Parental emotion regulation influences interactions between parents and children, as well as children’s socioemotional development (Rutherford, Wallace, Laurent, & Mayes, 2015). Morris et al. (2007) proposed that parental emotion regulation affects child emotional development through three mechanisms. The first involves observing parents’ emotion regulatory practices, and later, as children’s language ability develops, via verbal discussion with caregivers (Rutherford et al., 2015). A second mechanism is via emotion-related parenting practices; in other words, parental emotion coaching and parents’ reactions to children’s emotion expressions and experiences. Third, children’s emotion regulation also develops as a function of the emotional climate of the family, for example, through parent-child attachment. Children learn effective emotional and behavioral regulation strategies via relationships with significant caregivers (Eisenberg, Spinard, & Morris, 2002). The development of these self-regulatory strategies is crucial for preventing the development of psychopathology. Parental emotion regulation may play an important role in child emotional and behavioral adjustment, such that it affects parenting behaviors and the socialization process around child emotional adjustment.

Parental Emotion Regulation and Parenting Behaviors

Parental emotion regulation is theoretically and empirically related to parenting behaviors, and poor emotion regulation may disrupt effective parenting behaviors (Crandall, Deater-Deckard, & Riley, 2015). Parental emotion regulation difficulties are often associated with overreactive or lax disciplinary behaviors (Lorber, 2012). This suggests that in emotion-eliciting interactions with children, dysregulated parents may either withdraw behaviorally, or fail to inhibit their own distress which increases the likelihood of harsh discipline as a way to control children’s behaviors. Dysregulated parents may also display more rejection behaviors, show less warmth and fewer supportive responses to children’s emotional expressions (Hughes & Gullone, 2010; Morelen, Shaffer, & Suveg, 2016; Sarıtaş, Grusec, & Gençöz, 2013). Parental emotion dysregulation is associated with problems with disciplinary behaviors and undermines the ability of parents to foster positive and emotionally responsive interactions with their children.

Effective emotion regulation is related to more positive parenting and less negative parenting across the course of childhood (Crandall et al., 2015; Xiao, Spinrad, & Carter, 2018). Shaffer and Obradović (2017) recently tested this relationship in a diverse sample and found that parents who had difficulty generating effective emotion regulation strategies had lower levels of positive collaborative behaviors with their children during observed interaction tasks. Other findings have also suggested the importance of parental emotion regulation on parent-child interaction quality and parenting behaviors (Sanders & Mazzucchelli, 2013).

Military fathers may be more vulnerable to emotion regulation difficulties due to deployment and war-related trauma exposure. Military training emphasizes emotion suppression and control to promote mission completion. As such, service members may avoid their painful feelings and thoughts (Lorber & Garcia, 2010). This inability to tolerate unwanted negative feelings may result in impaired parenting behaviors after returning home. Empirical evidence has shown that both length of deployment and PTSD symptoms were associated with poorer parenting among post-deployed fathers (Davis, Hanson, Zamir, Gewirtz, & DeGarmo, 2015; Gewirtz, Polusny, DeGarmo, Khaylis, & Erbes, 2010). Brockman et al. (2016) found that deployed fathers’ experiential avoidance was concurrently associated with less observed positive engagement and more observed withdrawal and avoidance during interactions with other family members. More research is needed to understand the relationship between emotion regulation and parenting behaviors among deployed fathers over time.

Coercive Parenting as a Potential Mediator

Parental punitive behaviors and lack of warm involvement have been associated with children’s oppositional and aggressive behavior problems (Stormshak, Bierman, McMahon, & Lengua, 2000). A meta-analysis found a strong association between harsh parental control and child externalizing problems (Pinquart, 2017). Social interaction learning theory (SIL) proposes that children develop conduct problems and antisocial behaviors through coercive interactions with their caregivers (Patterson, 2016). For example, parents escalate their anger and punishment in order to terminate their children’s noncompliant behaviors, which may result in the escalation of child aversive reactions (Forgatch, Beldavs, Patterson, & DeGarmo, 2008). These sorts of coercive behaviors are primarily present during conflict bouts. The association between coercive parenting and child externalizing behavior problems has been widely found across a variety of populations (e.g., Lansford et al., 2011; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992).

Under stressful life circumstances, such as deployment, military fathers’ PTSD symptoms are associated with their disrupted parenting (Gewirtz et al., 2010), which may put their children at greater risk for adjustment problems. For example, deployed parents – especially those experiencing combat stress-related symptoms - may become overreactive in emotion-laden interactions and respond in harsh and punitive ways to discipline their children. In addition, a meta-analysis examining the relationship between parenting and child delinquency indicated that fathers’ coercive behaviors and poor support could have larger effects on child externalizing problems than mothers’ (Hoeve et al., 2009). Developmental studies have also shown that coercive fathering is more predictive of child adjustment problems than mothers’ harsh parenting (Hoeve et al., 2012; Patterson & Dishion, 1988). Since deployed fathers may be vulnerable to compromised parenting secondary to emotion regulation impairments (DeGarmo, 2016), this study aimed to examine the mediating role of coercive parenting in the relation between deployed fathers’ emotion regulation and child externalizing problems.

Additionally, less is known about whether fathers’ coercive parenting is related to child internalizing behavior problems. A few studies have proposed a relationship between coercive family processes and child depressed mood and anxiety (Crowley & Silverman, 2016; Patterson & Capaldi, 1990), but these studies did not measure coercive parenting behaviors directly, nor were they longitudinal. This study sought to examine the longitudinal relationship between fathers’ coercive parenting and child internalizing problems.

The Current Study

This study utilized a longitudinal design to examine the mediating role of observed paternal coercive parenting behaviors on the relationship between paternal ER and child internalizing/externalizing problems in a sample of military families. This is the first study to explore these associations longitudinally, among military families. We hypothesized that 1) paternal emotion regulation will be inversely associated with child adjustment problems; 2) better paternal emotion regulation will be related to less coercive parenting behaviors; and, 3) paternal coercive parenting behaviors will mediate the relationship between paternal emotion regulation and child adjustment problems. To test our hypotheses, a multi-method approach was used to measure emotion regulation among deployed personnel who are at high risk of PTSD. Given the importance of both mindfulness and experiential avoidance to this particular population, we examined emotion regulation using a latent variable that also included the most widely used measure of emotion regulation difficulties (i.e., the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; Gratz & Roemer, 2004).

Methods

Participants

This study used a subset of data from the After Deployment, Adaptive Parenting Tools/ADAPT study (see Gewirtz, DeGarmo, and Zamir, 2018 for information on the larger study). The original sample included 336 military families with at least one parent who had been deployed since 2001 and at least one child between the ages of 4 to 13 years. The current study focused on 181 male National Guard or Reserves service members who were in two-parent families with civilian wives. The fathers were, on average, deployed twice (SD = 1.13, range: 1 – 8) The majority were Army National Guard or Army Reservists (74.6%), followed by Air National Guard, Air Reserve, Navy Reserve, and other branches. Across all deployments, 31.7% service members were deployed for 1 year or less, 33.9% for 1–2 years, 26.1% for 2–3 years, and 8.3% for 3 years or more. They were mostly in their thirties (M age = 37.76, SD age = 6.42), white (87.8%), and well-educated (52.0% completed at least a bachelor’s degree). Most of the fathers reported being married (89.5%). Families were mostly middle to upper-middle-class income earners with 67.4% of them reporting an annual household income above $60,000. The average age of the target child was 8.43 years (SD = 2.44, range: 4.15 – 13.72), and 46.3% of the children were boys. The families had 2.39 children on average (SD = .87, range: 1 – 5). Most children were Caucasian (82.9%), and the rest were multi-racial (5.0%), African American (2.8%), Asia/Pacific Islander (2.8%) or unknown (6.6%). Parents were asked their relationship (biological, step, adoptive, or foster) to children in the home, but the specific relationship of the target child to the father was not asked.

Procedures

Families were recruited through presentations at reintegration events, mailing from the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, flyers, social media, and by word of mouth. Interested families were directed to complete an online screener. Following the completion of the screening survey, eligible families could consent to participate and complete an initial in-home assessment. Parents and children were compensated monetarily for their participation. There were multiple waves of recruitment, and a target child was selected if more than one child was eligible within a family. The oldest child was selected in the family as the target child during the first wave of recruitment, then, to avoid oversampling older children, the youngest child was selected after the first wave. Parents could also make their own choice regarding the target child if the oldest or youngest child was unwilling or ineligible to participate.

Following the baseline assessment, 60% of families were randomized to the ADAPT intervention group, while 40% were randomized to the control group (i.e., online parenting resources and tip sheets). Participants in the intervention condition were delivered a group-based, preventive intervention program targeting at improving parenting practices (see Gewirtz, Pinna, Hanson, and Brockberg, 2014). A total of fourteen 2-hr weekly sessions were delivered in a group format, and each group consisted of 4–15 parents. The current study used data collected at baseline, 1-year after baseline assessment (approximately 6-month post-intervention) and 2-year post-baseline, when both self-report and observational data were collected. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota.

Measures

Parental emotion regulation.

A latent construct of parental emotion regulation was conceptualized by three indicators at baseline: difficulties in emotion regulation, experiential avoidance, and trait mindfulness.

Difficulties in emotion regulation was measured using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS, Gratz & Roemer, 2004), which is a multi-dimensional assessment for measuring the inability to module emotional responses via appropriate strategies or to manage impulsive behaviors when experiencing negative emotions. DERS is a 36-item self-report scale which includes six subscales: Nonacceptance, Difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviors, Impulse control difficulties, Lack of awareness, Limited strategies, and Lack of clarity. Participants were asked to rate on a 1 to 5 scale (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always). Sample items are “When I’m upset, it takes me a long time to feel better,” “When I’m upset, I lose control over my behavior,” and “I have difficulty making sense out of my feelings.” The Cronbach’s α of this scale in the current sample was .94. A composite score was created such that higher scores indicate more difficulties in emotion regulation.

Experiential avoidance was measured using the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire – II (AAQ-II; Bond et al., 2011), which is a unidimensional tool for assessing experiential avoidance or psychological inflexibility. The AAQ-II consists of 7 items with each item rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true). Sample items are “I’m afraid of my feelings,” “Worries get in the way of my success,” and “I worry about not being able to control my worries and feelings.” The Cronbach’s α was .93 for the current sample. A composite score was created such that a higher score indicates a higher level of experiential avoidance.

Trait mindfulness was assessed using the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer, 2006), which assesses multiple aspects of trait mindfulness. The FFMQ has been applied in samples of military service members (e.g., Kearney, McDermott, Malte, Martinez, & Simpson, 2013) and it has displayed good internal consistency and reliability (Baer et al., 2008). The FFMQ assesses five dimensions of mindfulness: 1) observing - attending to or noticing internal and external stimuli, such as sensations, emotions, cognitions, sights, sounds, and smells; 2) describing - noting or mentally labeling these stimuli with words; 3) acting with awareness - attending to one’s current actions, as opposed to behaving automatically or absent-mindedly; 4) non-judging of inner experience - refraining from evaluation of one’s sensations, cognitions, and emotions; and 5) non-reactivity to inner experience - allowing thoughts and feelings to come and go, without attention getting caught up in them. Participants rated 39 items on a 5-point scale from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). Sample items are “I have trouble thinking of the right words to express how I feel about things,” “I perceive my feelings and emotions without having to react to them,” “When I have distressing thoughts or images, I feel calm soon after.” A composite score was created to indicate overall mindfulness. The Cronbach’s α was .88 for the current sample.

Observed coercive parenting.

Parent-child interactions during structured family interaction tasks (FITs) were videotaped at baseline and 1-year in participants’ home. A series of dyadic or triadic tasks were conducted among father-child or father-mother-child, and each task was 5 min long. In this study, father-child problem solving, father-mother-child problem solving, and father-child conversation about (re)deployment were used to assess father coercive parenting practices. During the problem-solving tasks, parent(s) and the focal child were instructed to discuss a conflictual issue they had identified earlier (e.g., tidying room, doing homework) and to try to come up with a solution. During the deployment discussion, the father and the child were directed to discuss their thoughts and feelings related to a specific upsetting or emotional topic related to the previous deployment (e.g., missing child’s birthday) and to create a plan for the issue if there were to be a future deployment. The Macro-Level Family Interaction Coding System (MFICS; Brockman et al., 2016; Snyder, 2013) was used to score parent-child interactions. The MFICS was designed to describe the observable behavioral and emotional interaction of family members with children ages 5 to 15 years. The reactivity-coercion subscale is comprised of 17 Likert scale items (1 = not true, not occur, 5 = clearly evident, very descriptive), using an a priori, face-valid approach to assess the occurrence of behaviors reflecting irritability, bossiness, nattering and persistent negativity that may be accompanied by anger and contempt and escalate to threats. Four observers coded the videos and 25% of the video samples were selected to assess the reliability of the coding. The average ICCs for this subscale at baseline and 1-year follow-up were .90 and .91. A cross-task composite score was calculated as the average of the scale scores across the three father-child interaction tasks. The Cronbach’s α was .70 at baseline and .78 at 1-year follow-up for the current sample.

Parent-reported child adjustment problems.

Child internalizing and externalizing symptoms were assessed with the parent version of the Behavioral Assessment Scale for Children-Second Edition (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). The BASC-2 scales have been shown to be highly correlated with the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and have moderate to high internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). Parents were asked to rate the frequency of their children’s symptoms on a Likert scale from 0 (never) to 3 (almost always). Two versions were used for children aged 5–11 and beyond age 12, so the final analysis used age-normed T-scores. The externalizing problems composite score was created from the aggression, conduct problems, and hyperactivity subscales (α range = .80 - .89 at baseline and α range = .78 - .86 at 2-year), and internalizing composite score was created from the depression, anxiety, and somatization subscales (α range = .78 - .93 at baseline and α range = .75 - .90 at 2-year). Parent-reported internalizing and externalizing problems were moderately correlated between mothers’ and fathers’ reports at both baseline and 2-year follow-up (rs = .49 – 56). As such, average scores by mothers’ and fathers’ reports were created at baseline and 2-year follow-up to measure child internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Child self-reported depression.

Child depression was assessed with the Child Depression Inventory–Short Form (CDI-S; Kovacs, 1983). The CDI-S consists of 10 items measuring depression symptoms from emotional, cognitive, psychomotor, and motivational domains for children seven and up. Children are asked to select the phrase that best represents their feelings during the past 1 or 2 weeks from three phrases (e.g., “I am sad once in a while”/ “I am sad many times”/ “I am sad all the time”). Higher scores on the CDI-S reflect a higher level of depressive symptoms. The CDI-S has shown to be highly correlated with the CDI full scale (r = .86) with adequate psychometric properties (Allgaier et al., 2012). The Cronbach’s αs were .78 at baseline and .79 at 2-year follow-up for the current sample.

Covariates.

Treatment status was dichotomized (0 for controls and 1 for the intervention). In the current paper, the ADAPT treatment effect was considered as a covariate because the potential intervention effect was not a focus of this study. Parent-related covariates included parent education, parent age, years of marriage, length of deployment (in months), combat exposure, and parent depression. Years of marriage was the average of husband and wife reports of years married to the current spouse. Combat exposure was measured using the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI; King, King, Vogt, Knight, & Samper, 2006). Parent depression was measured using the 25-item, self-report Hopkins Symptom Checklist Depression Scale (HSCL-D, Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth, & Covi, 1974). Child-related covariates included child age and child gender (coded as 1 = male and 2 = female).

Missing data.

A portion of the data was missing due to attrition at 1- and 2-year follow-ups. In the current sample, 80.1% families were retained at 1-year, and 79.6 % families at 2-year. The amount of missing data on variables used in the present study ranged from 0% to 13.3% at baseline, 33.7% for observed parenting measures at 1-year, and 29.3% for parent-reported child adjustment at 2-year. Missing data analysis compared participants who had data missing at 1- and 2-year to those with complete data. Fathers with lower education were more likely to have missing data at 1- and 2-year, compared to fathers with higher levels of education (r = −.15 at 1-year and −.16 at 2-year). The Little’s test was conducted without the parent education variable and the test indicated that the data were missing completely at random, Little’s χ2 (169) = 175.14, p = .357. Therefore, father’s education level was controlled for in all analyses, and missing data were managed using full information maximum likelihood (FIML).

Analytic Strategy

Preliminary analyses were conducted using SPSS 24.0 for descriptive statistics and correlation matrices. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) measurement model was specified for the latent construct of fathers’ emotion regulation with three indicators (i.e., trait mindfulness, experiential avoidance, and difficulties in emotion regulation). Next, three structural models were employed to examine the direct effect of parental emotion regulation on each child outcome at 2-year follow-up, controlling for the corresponding child outcome at baseline and covariates. Then, coercive parenting at 1-year was added to the models as a mediator to test the indirect effect of parental emotion regulation on child outcomes controlling for baseline child outcome, baseline coercive parenting, and covariates. Given that the CDI was administered to children age seven or older, the aforementioned analyses were conducted with a subsample of families (N = 115) when child self-reported depression was used as the outcome variable. Finally, the impact of the intervention on the indirect effects was examined using multi-group analysis between those families assigned to the intervention versus service-as-usual conditions. To estimate indirect effects, the bias-corrected bootstrapping with 2000 iterations (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007) was conducted and the 95% confidence intervals. Model fit was evaluated using the recommended criteria by Hu and Bentler (1999); a model was considered acceptable with a comparative fit index (CFI) greater than .95, a standardized root mean-square residual (SRMR) below .08, and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) below .06. CFA and structural equation modeling were conducted in Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations among the key variables are presented in Table 1. The absolute values of the correlations among the three indicators for parental emotion regulation (i.e., difficulties in emotion regulation, experiential avoidance, and trait mindfulness) ranged from .56 to .68. Fathers’ depressive symptoms were positively correlated with difficulties in emotion regulation and experiential avoidance and negatively correlated with their trait mindfulness. Fathers with more severe combat exposure and longer marriage exhibited higher coercive parenting at 1-year. With respect to child adjustment, child self-reported depression was not significantly correlated with parent-reported internalizing or externalizing problems. Gender differences were observed in parent-reported adjustment problems, with girls exhibited higher internalizing problems whereas boys exhibited higher externalizing problems.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the key study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DERS BL | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. AAQ BL | .68 | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3. FFMQ BL | −.65 | −.56 | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 4. RC BL | .14 | .08 | −.02 | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. RC 1-year | .28 | .30 | −.17 | .50 | — | |||||||||||||||

| 6. PINT BL | .15 | .10 | −.13 | .01 | .05 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 7. PINT 2-year | .18 | .13 | −.04 | .06 | .22 | .64 | — | |||||||||||||

| 8. PEXT BL | .25 | .23 | −.20 | .02 | .07 | .31 | .19 | — | ||||||||||||

| 9. PEXT 2-year | .27 | .21 | −.16 | .08 | .23 | .11 | .36 | .68 | — | |||||||||||

| 10. CDI BL | .06 | .22 | .06 | −.13 | .05 | .02 | .05 | .19 | .13 | — | ||||||||||

| 11. CDI 2-year | .07 | .16 | −.01 | .07 | .26 | .10 | .16 | .07 | .09 | .57 | — | |||||||||

| 12. Treat | .03 | .07 | −.08 | −.01 | −.08 | −.11 | −.15 | −.16 | −.13 | −.05 | −.01 | — | ||||||||

| 13. PAge | −.16 | −.09 | .12 | −.01 | .08 | −.04 | −.01 | −.10 | −.14 | .07 | −.11 | −0.1 | — | |||||||

| 14. Educ | −.01 | −.10 | .16 | −.09 | −.18 | −.00 | −.06 | .03 | −.15 | −.05 | −.28 | −0.1 | .19 | — | ||||||

| 15. DRRI | .00 | .25 | −.00 | .16 | .28 | .09 | .12 | .13 | .12 | .03 | .15 | 0.4 | −.00 | .04 | — | |||||

| 16. DeployM | −.07 | .07 | −.02 | .02 | .16 | .03 | .11 | .04 | .16 | .02 | .08 | .12 | −.04 | −.08 | .35 | — | ||||

| 17. YMar | .03 | −.01 | −.02 | .02 | .20 | −.10 | .02 | −.09 | −.14 | −.20 | −.16 | .06 | .61 | .27 | −.01 | −.11 | — | |||

| 18. Dep | .59 | .56 | −.45 | .07 | .17 | .17 | .19 | .09 | .03 | .21 | .01 | .04 | −.07 | −.18 | .16 | .01 | −.01 | — | ||

| 19. ChildG | .03 | −.05 | −.01 | −.04 | −.00 | .21 | .25 | −.25 | −.24 | .09 | −.00 | −.03 | −.03 | −.03 | −.14 | .06 | −.06 | .10 | — | |

| 20. ChildAge | −.09 | −.08 | .08 | .05 | .05 | −.03 | −.02 | −.12 | −.19 | −.19 | −.18 | −.10 | .34 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.03 | .42 | 0.04 | −.02 | — |

| M | 69.04 | 15.99 | 131.63 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 100.28 | 98.64 | 113.43 | 111.11 | 3.41 | 3.45 | .60 | 37.76 | 5.28 | 8.91 | 3.85 | 9.83 | 1.46 | 1.54 | 8.43 |

| SD | 19.51 | 7.70 | 16.26 | .27 | .27 | 17.41 | 17.52 | 22.06 | 22.20 | 1.88 | 2.15 | .49 | 6.42 | 1.28 | 7.51 | 1.79 | 5.26 | .47 | .05 | 2.44 |

Note. DERS BL = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation (baseline); AAQ BL = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (baseline); FFMQ BL = Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (baseline); RC BL = observed parental reactivity and coercion (baseline); RC 1-year = observed parental reactivity and coercion (1-year follow-up); PINT BL = child internalizing problems (baseline); PINT 2-year = child internalizing problems (2year follow-up); PEXT BL = child externalizing problems (baseline); PEXT 2-year = child externalizing problems (2-year follow-up); CDI BL = child self-reported depression (baseline); CDI 2-year = child self-reported depression (2-year follow-up); Treat = treatment status (1 = intervention, 0 = control); Page = parent age; DRRI = Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory; DeployM = deployment month; YMar = Year of Marriage; Dep = Parents’ depression; ChildG = child gender (1 = male, 2 = female). Statistically significant correlation coefficients are bolded (α = .05).

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

We first conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the fit of the latent construct of parental emotion regulation. The measurement model was just-identified, with high factor loadings (.73 for trait mindfulness, −.90 for difficulties in emotion regulation, and −.76 for experiential avoidance). It suggested that the latent construct was an adequate indicator of parental emotion regulation, with higher scores reflecting better regulatory abilities.

Direct Effect of Parental ER on Child Adjustment

Secondly, we tested the direct effect of parental emotion regulation on child adjustment. Results revealed that the three indicators of parental emotion regulation were significantly correlated with child externalizing problems cross-sectionally at baseline (r = .20 - .25). However, fathers’ emotion regulation at baseline was not significantly associated with child externalizing problems (B = −.29, SE = .23, β = −.15, p > .05), internalizing problems (B = .06, SE = .17, β = −.04, p > .05), or self-rated depression (B = −.03, SE = .03, β = −.17, p > .05) at 2-years controlling for baseline levels of adjustment problems respectively. The model fit indices were shown in Table 2. Despite the nonsignificant direct effects, the indirect effects were tested because indirect effects can exist in the absence of direct associations (in this case, parental ER and child adjustment; Hayes, 2009; Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

Table 2.

Model fit indices for the direct effects, indirect effects, and the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effects

| Models | Outcome variable | χ2(df) | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | Indirect effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | 95% CI | ||||||

| Direct effects | Internalizing problems | 7.52(10) | 1.00 | .00 | .02 | ||||

| Externalizing problems | 7.92(10) | 1.00 | .00 | .02 | |||||

| Self-reported depression | 10.68(10) | 1.00 | .02 | .03 | |||||

| Indirect effects through coercive parenting | Internalizing problems | 49.77(34) | .96 | .05 | .03 | −.11 | .06 | −.07 | [−.28, −.02] |

| Externalizing problems | 55.70 (34) | .95 | .06 | .03 | −.14 | .07 | −.07 | [−.31, −.03] | |

| Self-reported depression | 43.57 (33) | .96 | .05 | .04 | −.02 | .01 | −.11 | [−.42, −.00] | |

Note. 95% CI = 95% confidence internals derived from the bias-corrected bootstrapping with 2000 iterations.

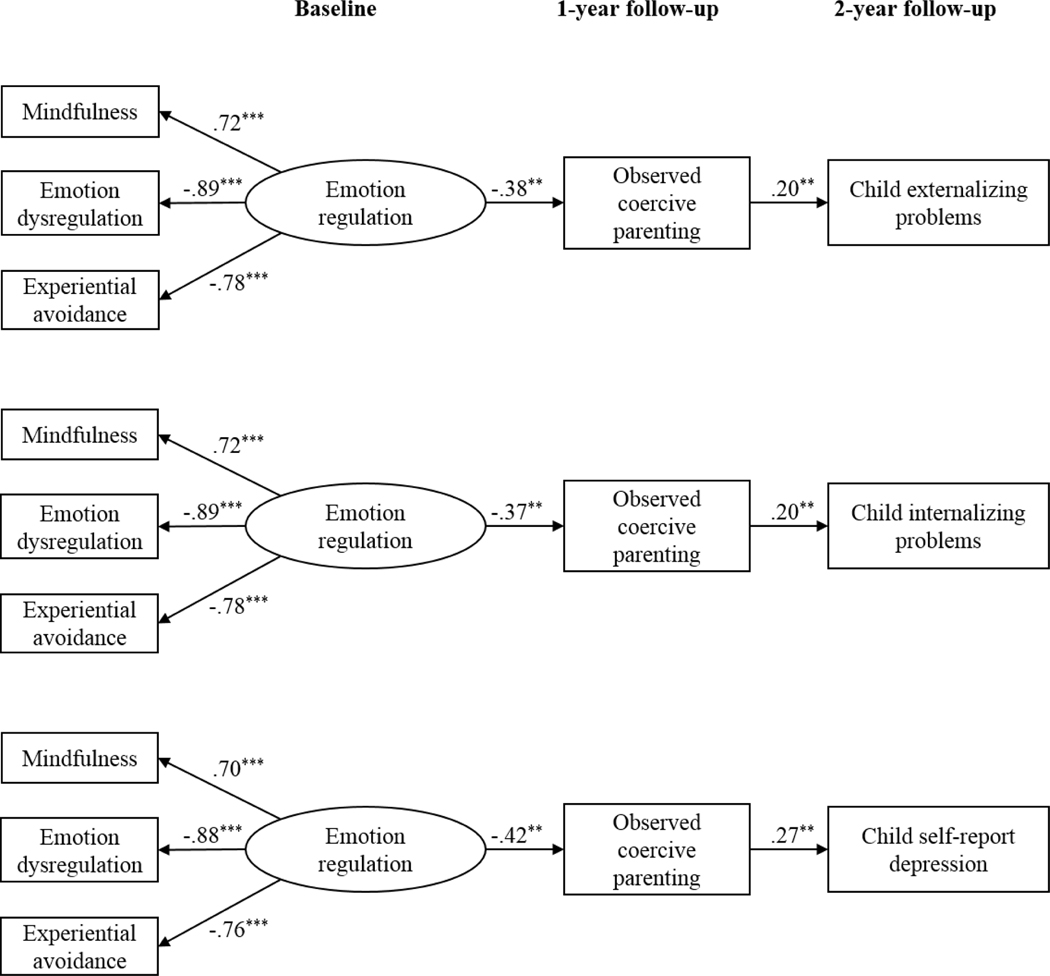

Indirect Effect of Parental ER on Child Adjustment

Finally, we tested the indirect effects of parental emotion regulation on child adjustment via coercive parenting. Results showed statistically significant indirect effects across the three measures of child adjustment. Specifically, fathers’ emotion regulation at baseline was negatively associated with observed coercive parenting at 1-year follow-up controlling for baseline levels of coercive parenting (B = −.01, SE = .00, β = −.38, p = .002 in the full sample, and B = −.01, SE = .00, β = −.42, p = .004 in the sample with child-reported depression as the outcome). Coercive parenting was, in turn, associated with parent-reported internalizing problems (B = 13.49, SE = 4.62, β = .20, p = .004), parent-reported externalizing problems (B = 16.29, SE = 5.69, β = .20, p = .005), and child self-reported depressive symptoms (B = 1.98, SE = .69, β = .27, p = .004) at 2-year follow-up controlling for the baseline levels of child adjustment respectively. The standardized path coefficients for each model were reported in Figure 1 and unstandardized and standardized path coeffects for all variables used in each model were presented in Supplementary Table 1 in the online supplementary materials. In addition, the indirect effects of fathers’ emotion regulation on internalizing problems (B = −.11, SE = .06, β = −.07, p = .037), externalizing problems (B = −.14, SE = .07, β = −.07, p = .040), and self-reported depressive symptoms (B = −.02, SE = .01, β = −.11, p = .048) via reduced coercive parenting behaviors were significant. The 95% confidence intervals of the unstandardized indirect effects were reported in Table 2. Child age and child gender were not found to be significantly associated with fathers’ coercive parenting at 1-year or child behavioral problems at 2-year controlling for the corresponding variables at baseline.

Fig. 1.

Structural equation path model for test of the mediating role of fathers’ coercive parenting on the relationship between fathers’ emotion regulation and child adjustment problems

Note. The sample size used in the first two models is 181, while the sample size used in the last model is 115 because children aged at least seven are eligible to report on the depression scale.

Multi-Group Analysis

A multi-group invariance test was conducted to examine group differences (i.e., intervention vs. control group) in the indirect effect of fathers’ emotion regulation on child adjustment via coercive parenting. A fixed model, with all paths (i.e., the path from parental emotion regulation to coercive parenting, the path from coercive parenting to child adjustment, and the path from parental emotion regulation to child adjustment) constrained to be equal across groups, was compared with the freely estimated model in terms of their model fit indices for each measure of child adjustment. The two groups were not significantly different according to the chi-square difference test (internalizing problems: Δχ2 = 1, df = 3, p > .05; externalizing problems: Δχ2 = 7, df = 3, p > .05; child self-report of depression: Δχ2 = 5, df = 3, p > .05). Therefore, this result supported the decision to collapse across the two groups and examine indirect effects including intervention status as a covariate.

Moderating effect of Child Age

A follow-up analysis was conducted for the moderating effect of child age on the relationship between fathers’ coercive parenting and child internalizing/externalizing problems. Results indicated that the moderation effects were not significant (internalizing: B = 3.71, SE = 2.08, β = .12, p > .05; externalizing: B = 2.72, SE = 2.59, β = .07, p > .05), which suggested that the relationship between coercive parenting at 1-year and child adjustment outcome at 2-years did not differ among children of different ages in the current sample.

Discussion

In the current study, we used longitudinal, multi-method and multi-informant data to examine the association between combat deployed military fathers’ emotion regulation and children’s adjustment problems, as well as the mediating role of coercive parenting for this association. Fathers’ emotion regulation was assessed as a latent construct, captured by multiple self-report measures such as difficulties in emotion regulation, experiential avoidance, and trait mindfulness. Analyses revealed that deployed fathers’ emotion regulation was not directly associated with subsequent child adjustment. Rather, fathers’ emotion regulation affected child adjustment indirectly through their coercive parenting behaviors.

Our results highlight the important role of coercive interactions between military fathers and their offspring, extending a large body of data on coercion to the military sphere. Fathers’ intrapersonal dysregulation likely affects child adjustment via their interpersonal emotion dysregulation (i.e., coercive parenting behaviors). These ineffective parenting behaviors may, in turn, reinforce children’s aversive behaviors as a way to terminate coercive parent-child interactions (Eddy, Leve, & Fagot, 2001). Military culture and the demands of war likely reinforce coercive interpersonal approaches and emotional suppression. These, together with disrupted emotion regulation abilities may place deployed military fathers at greater risk for aggressive or aversive parent-child interactions (Galovski & Lyons, 2004).

Consistent with prior studies, coercive parenting was found to be related to children’s externalizing problems over time (e.g., DeGarmo, 2010; Jaffee, Moffitt, Caspi, & Taylor, 2003). The use of observational measures to assess reactive-coercive parenting behaviors provides a more robust and less biased measure of parenting practices than self-reports (Snyder et al., 2006).

This study also found associations between coercive parenting behaviors and child internalizing symptoms, relationships that have been less well studied, especially among fathers. The existing literature has shown that maternal coercive parenting practices are related to children’s internalizing symptoms (e.g., Wu, 2007). A recent meta-analysis by Pinquart (2017) found that harsh control among parents was related to child internalizing symptomatology. Further, in a study of both mother and father general parenting practices, fathers’ parenting was more predictive of both child internalizing and externalizing symptomatology than mothers’ parenting among first-generation Latino families (Rodríguez, Davis, Rodríguez, & Bates, 2006). The current study extended and further validated those findings by focusing on fathers’ coercive parenting behaviors and looking at this relationship using a multi-informant approach (i.e., integrating parent-reports and child-reports of internalizing problems) in military families.

This study was innovative in considering the role of paternal emotional regulation on both paternal parenting practices and child psychopathology symptoms. This was an attempt to find potential targets for change within a two-generation framework. We hypothesized that parental functioning would have indirect effects on child emotional and behavioral functioning through parenting. Although the direct effect was not found, this study found that paternal emotion regulation was associated with children’s adjustment problems through its impact on fathers’ coercive behaviors. Prior studies have demonstrated the role of parental emotion regulation on parenting behaviors, which further exert influence on children’s emotion regulation and adjustment (Hughes & Gullone, 2010; Morelen, et al., 2016; Sarıtaş, et al., 2013). Cole and colleagues (1994) proposed that children internalize emotion regulation strategies based on the emotion displays modeled by their parents (Bariola, Gullone, & Hughes, 2011). For parents to be effective and adequate emotion and behavioral socialization agents for their child, they need to be able to adaptively manage their own emotions (Sanders, 2008). Data from the current study suggest that parent emotion regulation modeling and parenting behaviors are associated with children’s healthy emotional and behavioral development.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study focused on a sample of two-parent National Guard/Reserve families exposed to deployment and war-related experiences, limiting generalization to other populations experiencing different types of adversity. It would be of interest to extend these findings to other populations in which paternal emotion regulation may be negatively impacted. Second, the current sample of children included a wide age range (4 to 13 years old), limiting the ability to understand potential differences that parenting and paternal emotion regulatory abilities can have during different developmental stages. Further, internalizing and externalizing behaviors present and emerge in specific patterns dependent on child age. For example, children are more likely to experience both conduct and depression-related disorders during adolescence. Future studies could examine the effects of developmental stage on the relationship among paternal emotion regulation, coercive parenting, and child functioning.

The current study also did not examine how exposure to the intervention affected the relationships tested in this study. The focus on parents’ emotion regulation and coercive family interactions are central to the ADAPT parenting program (Gewirtz et al., 2014) for military families. The program integrated mindfulness components to target emotion regulation abilities, as well as Parent Management Training - Oregon model (GenerationPMTO) skills to reduce coercive parenting (Forgatch & Gewirtz, 2017; Forgatch & Patterson, 2010). However, in this study, intervention status was controlled as a covariate, and was not predictive of changes in fathers’ coercive parenting nor child adjustment problems. Despite this, another study using the same sample found that fathers’ emotion regulation difficulties at baseline moderated intervention effects on coercive parenting at 1-year follow-up (Zhang, 2018). Fathers with higher levels of emotion regulation difficulties showed significant reductions in coercive parenting at 1-year in the intervention group vs. control group, whereas fathers with fewer emotion regulation difficulties did not exhibit intervention effects. Therefore, the lack of evidence for intervention effects on coercive parenting may be due to the differential effects for fathers with low and high levels of emotion regulation at baseline. Another plausible reason was that fathers appeared to be slightly less satisfied with the intervention than mothers (Pinna, Hanson, Zhang, and Gewirtz, 2017), which may have led to fewer changes in their parenting behaviors post-intervention.

Conclusions and Implications

This study utilized a longitudinal design with multi-method and multi-informant measures to explore the role of father’s emotion regulation on coercive parenting practices and subsequent child externalizing and internalizing symptomatology. The results suggest that paternal emotion regulation and coercive interactions with children may increase risk for child psychopathology. This is particularly salient in the context of military deployment, because of the increased risk for psychopathology and emotional dysregulation in those exposed to traumatic stressors (i.e., war). These data extend the SIL framework and strengthen the literature on fathering that suggests that emotion dysregulation plays an important role in coercive parenting. Both emotion regulation and coercive parenting are malleable through interventions (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy and parenting intervention), suggesting that the current findings have clinical implications for the population of combat deployed military fathers and their children’s mental health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

The ADAPT study was funded by grants from NIDA R01 DA030114 to Abigail H. Gewirtz and R21 DA034166 to James Snyder. This research was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the National Institute of Health (T32 MH015755) to the second author. The third author’s work on this paper was supported by a National Research Service Award (NRSA) in Primary Prevention by the National Institute on Drug Abuse T32DA039772–03 (PI: Laurie Chassin) through the Department of Psychology at Arizona State University. The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the late James Snyder to this study, who developed the coding scheme and pioneered the conceptualization and measurement of family interactions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Contributor Information

Jingchen Zhang, Department of Family Social Science, University of Minnesota – Twin Cities.

Alyssa Palmer, Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota – Twin Cities.

Na Zhang, REACH Institute, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

Abigail H. Gewirtz, Department of Family Social Science and Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota – Twin Cities.

Reference

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Allgaier AK, Frühe B, Pietsch K, Saravo B, Baethmann M, & Schulte-Körne G. (2012). Is the Children’s Depression Inventory Short version a valid screening tool in pediatric care? A comparison to its full-length version. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 73, 369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, ... & Williams JMG (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15, 329–342. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bariola E, Gullone E, & Hughes EK (2011). Child and adolescent emotion regulation: The role of parental emotion regulation and expression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 198–212. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0092-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Westermann S, McRae K, Kuo J, Alvarez J, Kulkarni MR, ... & Bonn-Miller MO (2013). Emotion regulation and posttraumatic stress disorder: A prospective investigation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32, 296–314. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2013.32.3.296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, ... Zettle RD (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42, 676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockman C, Snyder J, Gewirtz A, Gird SR, Quattlebaum J, Schmidt N, ... DeGarmo D. (2016). Relationship of service members’ deployment trauma, PTSD symptoms, and experiential avoidance to postdeployment family reengagement. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 52–62. doi: 10.1037/fam0000152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM, & Creswell JD (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18, 211–237. doi: 10.1080/10478400701598298 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R, Gullone E, & Allen NB (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Michel MK, & Teti LOD (1994). The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 73–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01278.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall A, Deater-Deckard K, & Riley AW (2015). Maternal emotion and cognitive control capacities and parenting: A conceptual framework. Developmental Review, 36, 105–126. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley MJ, & Silverman WK (2016). Coercion dynamics and problematic anxiety in children. In Dishion TJ & Snyder JJ (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of coercive relationship dynamics (pp. 249–259). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis L, Hanson SK, Zamir O, Gewirtz AH, & DeGarmo DS (2015). Associations of contextual risk and protective factors with fathers’ parenting practices in the postdeployment environment. Psychological Services, 12, 250–260. doi: 10.1037/ser0000038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS (2010). Coercive and prosocial fathering, antisocial personality, and growth in children’s postdivorce noncompliance. Child Development, 81, 503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01410.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS (2016). Placing fatherhood back in the study and treatment of military fathers. In Gewirtz AH, Wadsworth SM, & Youssef AM (Eds.), Parenting and Children’s Resilience in Military Families (pp. 47–63). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Nordahl KB, & Fabiano GA (2015). Fathers and coercion dynamics in families: Developmental impact, implications, and intervention. In Dishion TJ & Snyder JJ (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of coercive relationship dynamics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, & Covi L. (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19, 1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy JM, Leve LD, & Fagot BI (2001). Coercive family processes: A replication and extension of Patterson’s coercion model. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 27, 14–25. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, & Morris AS (2002). Regulation, resiliency, and quality of social functioning. Self and Identity, 1, 121–128. doi: 10.1080/152988602317319294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez KC, Jazaieri H, & Gross JJ (2016). Emotion regulation: A transdiagnostic perspective on a new RDoC domain. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40, 426–440. doi: 10.1007/s10608-016-9772-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, & Gewirtz AH (2017). The evolution of the Oregon model of parent management training. In Weisz JR & Kazdin AE(Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (3rd ed., pp. 85–102). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, & Patterson GR (2010). Parent Management Training—Oregon Model: An intervention for antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In Weisz JR & Kazdin AE (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (pp. 159–177). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Beldavs ZG, Patterson GR, & DeGarmo DS (2008). From coercion to positive parenting: Putting divorced mothers in charge of change. In Kerr M, Stattin H, and Engels RCME (Eds.), What can parents do? New insights into the role of parents in adolescent problem behavior (pp. 191–209). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, & MacKinnon DP (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18, 233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galovski T, & Lyons JA (2004). Psychological sequelae of combat violence: A review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran’s family and possible interventions. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9, 477–501. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00045-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, & Davis L. (2014). Parenting practices and emotion regulation in National Guard and Reserve families: Early findings from the After Deployment Adaptive Parenting Tools/ADAPT study. In Wadsworth SM & Riggs DS (Eds.), Military deployment and its consequences for families (pp. 111–131). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, DeGarmo DS, & Zamir O. (2018). After deployment, adaptive parenting tools: 1-year outcomes of an evidence-based parenting program for military families following deployment. Prevention Science, 19, 589–599. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0839-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, Pinna KL, Hanson SK, & Brockberg D. (2014). Promoting parenting to support reintegrating military families: After deployment, adaptive parenting tools. Psychological Services, 11, 31–40. doi: 10.1037/a0034134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, Polusny MA, DeGarmo DS, Khaylis A, & Erbes CR (2010). Posttraumatic stress symptoms among National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq: associations with parenting behaviors and couple adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 599–610. doi: 10.1037/a0020571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, & Strosahl K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1152–1168. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.6.1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Dubas JS, Eichelsheim VI, Van Der Laan PH, Smeenk W, & Gerris JR (2009). The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Stams GJJM, Put CE, Dubas JS, Laan PH, & Gerris JRM (2012). A meta-analysis of attachment to parents and delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 771–785. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9608-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, & Milliken CS (2006). Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA, 295, 1023–1032. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes EK, & Gullone E. (2010). Discrepancies between adolescent, mother, and father reports of adolescent internalizing symptom levels and their association with parent symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66, 978–995. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, & Taylor A. (2003). Life with (or without) father: The benefits of living with two biological parents depend on the father’s antisocial behavior. Child Development, 74, 109–126. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Breen WE, & Julian T. (2010). Everyday strivings in war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: Suffering from a hyper-focus on avoidance and emotion regulation. Behavior Therapy, 41, 350–363. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Morina N, & Priebe S. (2009). Post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, and depression in survivors of the Kosovo War: Experiential avoidance as a contributor to distress and quality of life. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney DJ, McDermott K, Malte C, Martinez M, & Simpson TL (2013). Effects of participation in a mindfulness program for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 14–27. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LA, King DW, Vogt DS, Knight J, & Samper RE (2006). Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory: A collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences of military personnel and veterans. Military Psychology, 18, 89–120. doi: 10.1207/s15327876mp1802_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. (1983). The Children’s Depression Inventory. A self-rated depression scale for school-aged youngers. Unpublished manuscript, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Criss MM, Laird RD, Shaw DS, Pettit GS, Bates JE, & Dodge KA (2011). Reciprocal relations between parents’ physical discipline and children’s externalizing behavior during middle childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 225–238. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF (2012). The role of maternal emotion regulation in overreactive and lax discipline. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 642–647. doi: 10.1037/a0029109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber W, & Garcia HA (2010). Not supposed to feel this: Traditional masculinity in psychotherapy with male veterans returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47, 296–305. doi: 10.1037/a0021161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Price JL, Rodriguez BF, Ripley MP, & Warner RA (2004). Emotional deficits in military-related PTSD: An investigation of content and process disturbances. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17, 275–279. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029271.58494.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelen D, Shaffer A, & Suveg C. (2016). Maternal emotion regulation: Links to emotion parenting and child emotion regulation. Journal of Family Issues, 37, 1891–1916. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14546720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, & Robinson LR (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16, 361–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén O. (1998-2017). Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR (2016). Coercion theory: The study of change. In Dishion TJ & Snyder JJ (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of coercive relationship dynamics (pp. 7–22). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, & Capaldi DM (1990). A mediational model for boys’ depressed mood. In Rolf J, Masten AS, and Cicchetti D. (Eds.), Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology (pp. 141–163). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe B, & Ramsey E. (1989). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist, 44, 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, & Dishion TJ (1988). Multilevel family process models: traits, interactions, and relationships. In Hinde RA, & Stevenson-Hinde J. (Eds.), Relationships within families: Mutual influences (pp. 283–310). Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, & Dishion TJ (1992). Antisocial boys: A social interactional approach. Eugene, OR: Castalia. [Google Scholar]

- Pinna KL, Hanson S, Zhang N, & Gewirtz AH (2017). Fostering resilience in National Guard and Reserve families: A contextual adaptation of an evidence-based parenting program. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87, 185–193. doi: 10.1037/ort0000221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M. (2017). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 53, 873–932. doi: 10.1037/dev0000295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, & Kamphaus RW (2004). BASC-2: Behavior assessment system for children second edition manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez MD, Davis MR, Rodríguez J, & Bates SC (2006). Observed parenting practices of first-generation Latino families. Journal of Community Psychology, 34, 133–148. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford HJ, Wallace NS, Laurent HK, & Mayes LC (2015). Emotion regulation in parenthood. Developmental Review, 36, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR (2008). Triple P-Positive Parenting Program as a public health approach to strengthening parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 506–517. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR, & Mazzucchelli TG (2013). The promotion of self-regulation through parenting interventions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0129-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarıtaş D, Grusec JE, & Gençöz T. (2013). Warm and harsh parenting as mediators of the relation between maternal and adolescent emotion regulation. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 1093–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligowski AV, Lee DJ, Bardeen JR, & Orcutt HK (2015). Emotion regulation and posttraumatic stress symptoms: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 44, 87–102. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2014.980753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer A, & Obradović J. (2017). Unique contributions of emotion regulation and executive functions in predicting the quality of parent–child interaction behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology, 31, 150–159. doi: 10.1037/fam0000269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd L, & Wild J. (2014). Emotion regulation, physiological arousal and PTSD symptoms in trauma-exposed individuals. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 45, 360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, & Bolger N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J. (2013). Macro-Level Family Interaction Coding System (MFICS): Technical report. Unpublished manuscript, Wichita State University, Department of Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JJ (2016). Coercive family processes and the development of child social behavior. In Dishion TJ & Snyder JJ (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of coercive relationship dynamics (pp. 101–113). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Gewirtz A, Schrepferman L, Gird SR, Quattlebaum J, Pauldine MR, ... & Hayes C. (2016). Parent–child relationship quality and family transmission of parent posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and child externalizing and internalizing symptoms following fathers’ exposure to combat trauma. Development and Psychopathology, 28, 947–969. doi: 10.1017/S095457941600064X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Low S, Bullard L, Schrepferman L, Wachlarowicz M, Marvin C, & Reed A, (2013). Effective parenting practices: Social interaction learning theory and the role of emotion coaching and mindfulness. In Larzere RE, Morris AS, & Harrist AW (Eds.), Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 189–210). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Reid J, Stoolmiller M, Howe G, Brown H,amp Dagne G, & Cross W. (2006). The role of behavior observation in measurement systems for randomized prevention trials. Prevention Science, 7, 43–56. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0020-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bierman KL, McMahon RJ, & Lengua LJ (2000). Parenting practices and child disruptive behavior problems in early elementary school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 17–29. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 25–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01276.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Defense (2016). Profile of military community: Demographics 2016. Retrieved from https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2016-Demographics-Report.pdf

- Wahbeh H, Lu M, & Oken B. (2011). Mindful awareness and non-judging in relation to posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Mindfulness, 2, 219–227. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0064-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner K, & Gross JJ (2010). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A conceptual framework. In Kring AM & Sloan DM (Eds.), Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment (pp. 13–37). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu CI (2007). The interlocking trajectories between negative parenting practices and adolescent depressive symptoms. Current Sociology, 55, 579–597. doi: 10.1177/0011392107077640 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao SX, Spinrad TL, & Carter D. . (2018). Parental emotion regulation and preschoolers’ prosocial behavior: The mediating roles of parental warmth and inductive discipline. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 179, 246–255. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2018.1495611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki J, & Williams WC (2013). Interpersonal emotion regulation. Emotion, 13, 803–810. doi: 10.1037/a0033839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. (2018). Less is more: Emotion regulation deficits in military fathers magnify their benefit from a parenting program (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from the University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, http://hdl.handle.net/11299/200111. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.