Abstract

Background and Aim:

Pandemic and consequent lockdowns are likely to affect the drug market by the sudden disruption of the supply chain. We explored the change in the availability, access, purity, and pricing during lockdown from respondents seeking treatment for drugs, alcohol, and tobacco dependence.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 404 respondents from seven treatment centers across India. A structured questionnaire assessed the change in availability, access, quality, and price of substances used during the first phase (March 24–April 14) and the second phase (April 15–May 3) of lockdown.

Results:

A majority of the respondents in treatment used tobacco (63%) and alcohol (52%). Relatively few respondents used opioids (45%) or cannabis (5%). Heroin (44%) was the most common opioid the respondents were treated for. Seventy-five percent, 65%, and 60% of respondents treated for alcohol, tobacco, and opioid problems, respectively, reported a reduction in the availability and access during the first phase of the lockdown. In the second phase, respondents with alcohol and tobacco dependence reported greater availability than those with opioid and cannabis dependence. The reported price of all substances increased more than 50% during the first phase of lockdown and remained higher throughout the second phase. Deterioration in purity was reported by more than half of the people who used opioid.

Conclusion:

Lockdown could have affected both licit and illicit drug markets, albeit to a varying degree. The observed changes seemed short-lasting, as suggested by the recovering trends during the second phase of lockdown.

Keywords: COVID-19, India, lockdown, substance availability, substance quality

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). COVID-19 was first reported in China in December 2019 and subsequently declared as a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020.[1] Governments globally are acting to contain and control the pandemic by deploying all available health resources. The disruption of normal services has put an unprecedented strain on health, social, and economic systems in all countries including India.[2,3]

People who use drugs and alcohol are in an especially vulnerable position during COVID-19. Due to the psychological impact of COVID-19, the prevalence of substance use is likely to increase.[4] Those who use substances are likely to have greater chances of exposure because of risky behaviors and poor precautionary measures. They might also experience worse COVID-19 outcomes.[5] Further, due to the unprecedented nature of the pandemic and associated consequences, impacts have been observed in the availability and access to drugs and alcohol.[6,7] Surveys among addiction professionals as well as drug users suggest a variable impact on the supply and price of drugs.[8] Reports available suggest that lockdown may have also contributed to increased incidences of withdrawal or possible overdoses.[9] According to the United Nations Office on Drug and Crime (2020), measures implemented to counter the COVID-19 pandemic have variably affected all aspects of illegal drug markets. Increased alcohol sales and use were observed in the USA, Europe, UK, Canada, and Australia during the initial weeks of lockdown.[10,11,12,13] In India, alcohol production, sales, and purchase were barred with an overnight prohibition order following the nationwide lockdown. Indirect evidence from newspaper reports, online trends data, and data from the treatment-seeking population suggested decreased alcohol availability during this period.[14,15]

However, many of these reports were based on individuals’ opinions and media reports from carers. Thus, these may not reflect the actual availability, access, street pricing, and quality of drugs.[16] Further, while data is available for Europe and North American countries, no studies explore the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on India’s drug availability and pricing.

India announced a complete lockdown on March 25 to contain the spread of COVID-19. The initial phase lasted for 21 days, that is, till April 14, after which the lockdown was subsequently extended till May 3. During this period, all nonessential activities, including shops, work, and travel, were suspended and people were asked to stay in their homes, except for the most critical of circumstances.[17] Alcohol and tobacco are considered nonessential commodities in India, and in compliance with the lockdown orders, all production, sales, and purchase were prohibited. Though the curbs during both lockdown phases were similar, the first lockdown was much unexpected and brought everything to a sudden halt. Hence, we had expected a greater change in drug use availability and pattern during phase 1 than phase 2. We conducted the present study to investigate the availability, access, purity, and price of licit and illicit drugs among treatment-seeking populations presenting to various tertiary care medical college hospitals in India.

We recruited multiple centers from different regions of India. The nationwide survey reported a wide variation in the prevalence of drug and alcohol use across the country. For example, the prevalence of alcohol use in the past 12 months was 35% in the state of Chhattisgarh and 1% in Bihar.[18] Similarly, 7% of the general population in Mizoram had used illicit opioids in the last year, whereas the prevalence was 0.1% in Bihar. Moreover, there are stark state-wise differences in the socioeconomic indicators such as gross domestic product, literacy, and employment.[12] These factors together and independently could also influence drug and alcohol use.[18]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study procedure

We reached out to 12 publicly funded tertiary care medical colleges with psychiatry centers offering addiction treatment facilities across India; 11 agreed to participate in the study. We chose the centers to capture data from different regions in India. Each center got the study protocol approved by its respective institutional ethical committee. The study period was between June 15 and September 15, 2020 and varied for each center in accordance with restarting of outpatient services. Among the 11 centers, three continued to have their psychiatry services closed as the existing services were diverted to the care of patients with COVID-19, while another one dropped out of the study. Hence, the final data were collected from seven centers from different regions of India – North (Chandigarh, Rohtak, Rishikesh), West (Jodhpur), Central (Raipur), and East (Bhubaneswar, Patna). Six out of these seven centers have dedicated addiction psychiatry treatment facilities.

Participants

We conducted a face-to-face or telephonic interview with patients attending substance abuse treatment centers following the nationwide lockdown withdrawal. We used a cross-sectional study design with convenience sampling. Patients with substance use disorders visiting the outpatient psychiatry/addiction services were recruited. Patients meeting the following inclusion criteria were included: (i) first registration to the outpatient services for substance use disorders, or patients already registered in the clinic; (ii) patients ≥18 years of age; (iii) patients with current substance use (we defined the current use as any substance use in the last 1 month of study recruitment); and (iv) patients providing informed consent for participation in the study. We excluded subjects presenting with (i) severe complicated withdrawal requiring urgent medical attention, (ii) acute comorbid physical or severe mental illness, and (iii) subjects who were stable and maintained abstinence during the lockdown period.

Development and description of the questionnaire

We used a pretested structured questionnaire exploring multiple aspects of substance-related behaviors during the lockdown. We intended to document the “change” (in reference to the prepandemic period) in various substance-related aspects that were associated with the first (from March 24 to April 14, designated as a period ‘A’) and second phase (from April 15 to May 3, defined as period ‘B’) of lockdown. We considered the change in the participants’ primary drug of concern (primary drug being for which the treatment was sought). Prepandemic reference point was defined as a month before the imposition of lockdown. The questionnaire consisted of close-ended, Likert-type questions. There were four levels to the response of each question. The scale anchor point was “change” of the construct (e.g., street price of the “primary” substance) in reference to the prepandemic time. One of the levels was “no change,” and there were two levels in the negative direction (e.g., “costly” and “much costly” price) and one level in the positive direction (e.g., “cheap”). We defined “costly” as a 25%–50% hike in the street price of the drug and much costly as a more than 50% hike. “Cheap” was defined by at least 25% reduction of the street price. For this particular paper, we describe the findings related to substance availability, accessibility, quality, and pricing. To clearly identify the interruption level, we explored supply-related challenges using two variables: availability and accessibility. These constructs were defined as follows: (1) availability: information regarding the presence of drugs and alcohol in the market or usual sources (e.g., known peddler, friends); (2) access: the ease at which drugs and alcohol could be procured; (3) quality: an overall subjective measure, based on the effect of the substance after consumption and the change in color, texture, or other physical features; and (4) pricing: cost of a particular substance in the black market. These variables could be considered as drug and alcohol “supply related.” For this article, we discussed the results of the changes happening in the supply side of drugs and alcohol during the pandemic. Detailed description of the questionnaire and results related to aspects of demand reduction-related findings are presented elsewhere.[19]

We have adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. A written informed consent was obtained from all the in-person respondents. Consent was taken verbally and through online forms. The study was approved by the ethics committees of all seven institutes in which the study was conducted.

Statistical analysis

There was no missing data for the sociodemographic and clinical variables. Some responses (<1%) were missing for supply-related variables for two phases of the lockdown, and those cases were excluded. Descriptive statistics were used for the analysis.

RESULTS

Out of the 404 responses, 241 (59.7%) were collected by face-to-face interview. A total of 163 participants were recruited through telephonic interview. Around 200 participants were approached through telephone. Those who did not consent to participate were excluded. Center-wise distribution of the participants was as follows: Bhubaneswar (79, 19.6%), Rohtak (67, 16.6%), Chandigarh (100, 24.8%), Jodhpur (51, 12.6%), Patna (41, 10.1%), Raipur (38, 9.4%), and Rishikesh (28, 6.9%).

Sociodemographic profile of the sample

Majority of the respondents were male (97.3%), married (69.1%), Hindus (85%), living in a nuclear family (55%), from urban background (52.7%), and currently unemployed or never employed (37.1%). Table 1 describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample in detail.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 393 (97.3) |

| Female | 11 (2.7) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married | 125 (30.9) |

| Married | 279 (69.1) |

| Education status | |

| Illiterate | 15 (3.7) |

| Literate | 9 (2.2) |

| Primary | 35 (8.7) |

| Middle | 73 (18.1) |

| Higher secondary | 161 (39.85) |

| Graduation | 82 (20.30) |

| PG | 29 (7.18) |

| Employment | |

| Never employed | 28 (6.9) |

| Presently unemployed | 122 (30.2) |

| Presently employed | 90 (22.3) |

| Part-time | 24 (5.9) |

| Self-employed | 120 (29.7) |

| Student | 17 (4.2) |

| Any other | 3 (0.7) |

| Living | |

| Joint family | 174 (43.1) |

| Nuclear family | 222 (55.0) |

| Background | |

| Rural | 159 (39.4) |

| Urban | 213 (52.7) |

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 347 (85.9) |

| Muslims | 14 (3.5) |

| Sikhs | 41 (10.1) |

Clinical profile of the sample

We evaluated the patients on all the substances consumed by them (current use) and the substance for which they sought treatment (primary substance). Among the substances in current use, the most common substance was tobacco (63.4%), followed by alcohol (52%) and opioids (45.3%), while alcohol (41%) and opioids (38.9%) were the most common primary substances reported [Table 2]. Fifty-seven percent (n = 232) were using more than one substance.

Table 2.

Clinical profile of the sample

| Substance | Primary substance, n (%) | Current use, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 166 (41.1) | 210 (52) |

| Opioids | 158 (38.9) | 182 (45) |

| Heroin | 74 (46.8) | 80 (44) |

| Natural | 57 (36.1) | 63 (34.6) |

| Pharmaceuticals | 27 (17.1) | 39 (21.4) |

| Cannabis | 21 (5.2) | 76 (18.8) |

| Tobacco | 53 (13.1) | 256 (63.4) |

| Others | 7 (1.7) | 10 (2.5) |

Supply-related variables during the lockdown

Among the 404 respondents, 210 (52%), 168 (41.5%), 244 (60.4%), and 75 (18.6%) provided details for alcohol, opioids, tobacco, and cannabis, respectively.

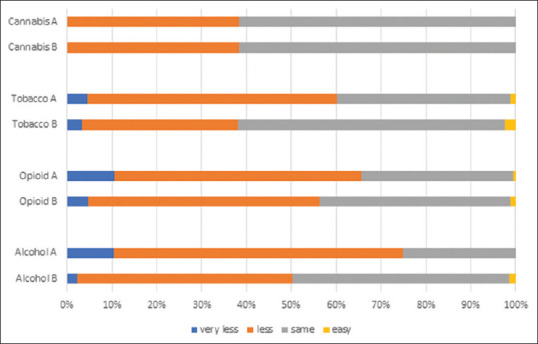

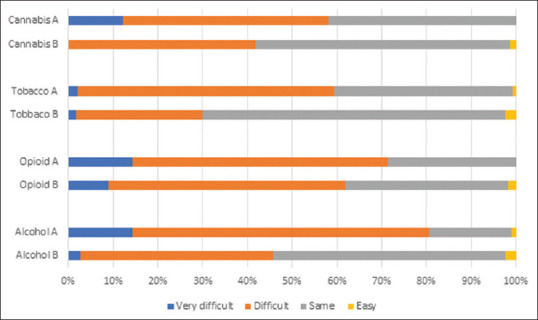

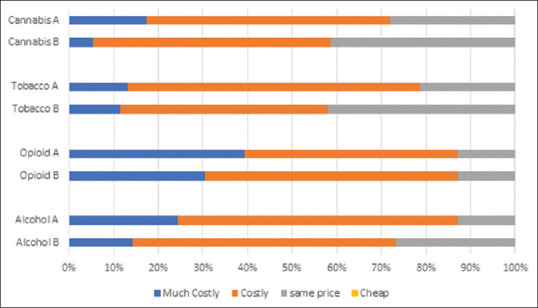

During the first phase of the lockdown, 10% and 65% reported very less and less availability and 81% reported difficulty (very difficult or difficult) in accessibility of alcohol. In comparison, during the second phase of lockdown, availability (50% reporting any difficulty) and accessibility (46% reporting any difficulty) improved [Figures 1 and 2]. Reported cost of alcohol continued to remain high during both phases, with much higher cost in the first phase (88% vs. 73%) [Figure 3]. Also, deterioration in the quality of alcohol was reported during the first and second phases.

Figure 1.

Availability of different substances during the lockdown (A- first phase from March 24 to April 14, 2020; B- second phase from April 15 to May 3, 2020)

Figure 2.

Accessibility to different substances during the lockdown (A- first phase from March 24 to April 14, 2020; B- second phase from April 15 to May 3, 2020)

Figure 3.

Cost of different substances during the lockdown (A- first phase from March 24 to April 14, 2020; B- second phase from April 15 to May 3, 2020)

For opioids, over one-half and two-thirds of the respondents reported any difficulty in availability and accessibility during the first phase. The situation improved slightly during the second phase, with still over half of the respondents reporting difficulty with availability and accessibility. Interestingly, a small proportion reported ease in availability and accessibility of opioids, particularly during the later phase of the lockdown. Half of the sample reported deterioration in quality and over 85% reported increased prices of opioids during both phases of the lockdown period.

While those reporting decreased availability of cannabis (39%) remained constant over both phases, accessibility was limited more during the first phase (58%) compared to the second phase (41%). Over 70% (18% much costly, 54% costly) reported increased cannabis prices during the lockdown, while during the second phase, this number was 59%(5% much costly, 54% costly).

For tobacco, three-fifths reported less availability and accessibility during the first phase of lockdown, while 38% and 30% reported less availability and accessibility, respectively, during the second phase. Seventy-nine percent and 59% reported increased prices during the first and second lockdown phases, respectively.

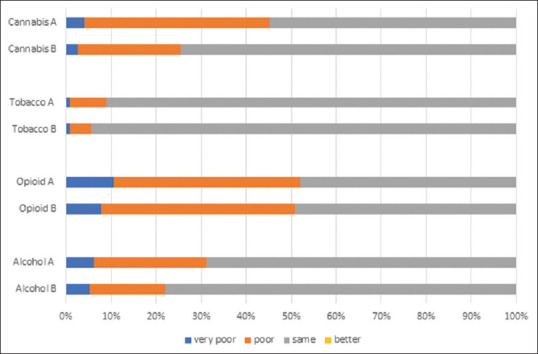

Highest deterioration in quality was observed for opioids (52% vs. 51%), followed by cannabis (45% vs. 25%) and alcohol (31% vs. 22%) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Quality of the substances during the lockdown (A- first phase from March 24 to April 14, 2020; B- second phase from April 15 to May 3, 2020)

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first multicenter study that reported the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on the availability, accessibility, street pricing, and quality of alcohol and drugs in India. The main findings of our study were as follows. During the first phase of the lockdown, 75%, 65%, and 60% of respondents with alcohol, tobacco, and opioid dependence, respectively, reported a reduction in the availability and access. In the second phase, respondents with alcohol and tobacco dependence reported greater availability than those with opioid and cannabis dependence. The reported price of all substances increased more than 50% during the first phase of lockdown and remained higher throughout the second phase. Deterioration in purity was reported by more than half of the opioid users. A lesser proportion of participants reported poorer quality of alcohol and cannabis.

Alcohol sales in India are regulated and sold through government-licensed shops. As the lockdown was announced, owing to the ambiguity, alcohol shops remained open at most places in India for the initial few days, followed by complete prohibition. In our study, 75% reported limitation in alcohol availability, while 80% reported some difficulty in accessing alcohol during the first phase of lockdown. Such an abrupt disruption in alcohol availability has been documented to result in an increased presentation of complicated withdrawals in the past[20] and during the current pandemic[9] as well. Increased risk of such detrimental outcomes and in the absence of a national-level alcohol policy, debates ensued among health professionals to consider providing alcohol as an emergency provision.[14,21] By the second phase of the lockdown, alcohol availability and accessibility improved, as only 50% of the respondents reported such issues. One of the interesting findings is that even during the first phase of the lockdown, one-fifth of the individuals had access to alcohol, which further increased to one in two during the next phase of the lockdown. This seems to suggest that despite the complete closure of the alcohol shops, alternate channels sprouted and ensured alcohol availability from illicit channels. This, in turn, would have impacted the prices, which 80% of respondents confirmed in our study. This high street price persisted during the subsequent phase of lockdown as well. The abrupt prohibition pushed people to seek desperate measures as a significant increase in the relative search volume was observed for alcohol withdrawal, extracting alcohol from sanitizer, offline and online alcohol home delivery.[15] The Global Status Report on alcohol observed that nearly half of the per capita alcohol consumed in the South East Asian Region countries was unrecorded alcohol, that is, obtained from alternate (including illicit) sources (WHO, 2019). It is likely that to meet the demands and maximize profits, a concoction of illegal liquor and Indian-made foreign liquor would have been sold.[20] Almost one-third of the respondents reported deterioration in the quality of alcohol. The impact of such spurious practices has been observed in later periods of the pandemic as well, where incidents of hooch tragedy (poisoning due to illicit liquor) are being reported in different parts of India.[21]

Tobacco, being a nonessential commodity, was prohibited for sale. But despite such restrictions, two-fifths of our patients did not report any significant issues with the availability or access of tobacco and related products during the first phase of lockdown. This subsequently had improved during the later phase. Thus, just like alcohol, it is very likely that alternate channels opened up to ensure availability at premium prices. In fact, our study finds that over 80% of people reported a hike in prices, with over 10% reporting almost doubling of prices. Such increased pricing persisted during the later phase as well. A survey of tobacco users in treatment found that 45% reported decreased availability, with 27% reporting increased prices.[1] In the wake of the pandemic, some countries mandated tobacco products as essential commodities to ensure regular availability.[21] However, as reports emerge linking smoking with adverse COVID-19 outcomes, calls to use pandemic as an opportunity to control the tobacco epidemic have been made.[22] As lockdown measures restricted tobacco products’ availability, it was speculated that may have motivated people to finally quit. Our findings suggest that indeed the majority of individuals found it difficult to access tobacco and those who did had to pay a premium. Thus, it is likely that lockdown may have put people into forced abstinence, but it remains unclear how many of those sustained their abstinence once lockdown was called off.

Over 70% reported difficulty in accessibility, while 65% reported decreased availability of opioids during the initial phase of lockdown, with a slightly lesser number reporting such challenges during the later phase. This suggests that the lockdown impacted the supply chain, which persisted throughout the lockdown period, unlike alcohol, tobacco, or cannabis. Further, this impact was visible in the prices of opioids, as about 90% reported an increase in the price of opioids during the whole lockdown period, with more (39% vs. 30%) reporting a doubling of prices during the first phase. In a European drug survey conducted during April, half of the respondents reported drug shortage and 40% reported increased prices.[23] Two-fifths of addiction professionals from over 75 countries reported decreased availability and increased prices of opioids during the lockdown.[8] Our findings suggest that the shortage of opioids and pricing changes was more acutely felt in India than available evidence from other countries. Such changes in opioid availability and pricing understandably led to poor quality. Over 50% reported deterioration in the quality of available opioids in our study, which again is a figure higher than other international findings. It is very likely that the strict lockdown imposed in India severely restricted the movements and significantly impacted the opioid market. This would have caused shortages of opioids with no clarity on future consignments, and as a result, dealers ended up mixing the available drugs to meet the local demands.

Reports suggest that under certain circumstances, lockdown restrictions can actually work in favor of drug dealers and may make drug trafficking easy, as law enforcement may be diverted toward pandemic-related service.[7,24] In our study, a small minority reported easy availability and better accessibility of drugs and alcohol, especially during the second phase of the lockdown. Drug dealers would likely have adopted innovative ways to reach out to their clients, despite strict restrictions.[25] Anecdotal evidence from our clinics suggests home delivery of drugs and alcohol was one of the most favored approaches. There is a possibility that such alternate routes may have continued to flourish even after the lockdown measures, making drugs more accessible to vulnerable populations.

The following are the strengths of our study. (i) This was a multi-site study with centers from the northern, eastern, western, and central parts of the country. All these publicly funded treatment centers have a wide catchment area, spanning across the neighboring states. The heterogeneity offered by such a diverse sample should increase the generalizability of our study findings. (ii) Direct interviews of the end-users should make the study results more reliable and valid than the impressionistic reports of professionals and media houses. (iii) Use of uniform survey questionnaire, administered by a trained psychiatrist with at least 1 year of clinical experience in addiction psychiatry, has further added to the reliability of our results. (iv) Minimal missing data, too, adds to the credibility of the study findings. (v) Finally, our sample comprised individuals with drug and alcohol dependence. People who continued to use substances throughout the COVID-19 lockdown periods were more likely to have a better understanding of aspects of the market related to supply of their drugs of concern. Reports from this group would possibly be more reflective of the ground reality than reports from occasional users.

There are certain limitations in our study. Firstly, since data was collected a few months after the lockdown period, recall bias could not be ruled out. Secondly, our scope was only limited to alcohol, opioids, tobacco, and cannabis, as other substances were reported rarely. Thirdly, we were not able to establish any association between the availability of different substances and quitting behaviors. Fourthly, ours was a clinic-based study on the treatment-seeking population; hence, the results may have limited population-level generalizability. The convenience sampling, too, might have affected the generalizability of the study results. Fifth, we did not do any objective assessment of drug and alcohol use; hence, the possibility of false reporting owing to social desirability could not be denied. Finally, we did not gather information regarding the age of the participants, other comorbidities, duration of substance use, and other clinical details. Lack of these information may limit the generalizability of our results.

CONCLUSION

Lockdown has potentially impacted both licit and illicit drug markets, albeit to a varying degree. The observed changes seemed short-lasting, as suggested by the recovering trends during the second phase of lockdown as the restrictions’ intensity was lifted gradually. In the future, it would be interesting to see how these changes in the drug and alcohol market affected the use and treatment-seeking behavior. The potential public health implications of the abrupt disruption of supply, without provisions of improved treatment opportunities, should also be examined in future studies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19):A review. JAMA. 2020;324:782–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic:Interim report, 2020. [Last accessed on 2021 May 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2020.1 .

- 3.Arya S, Gupta R. COVID-19 outbreak:Challenges for Addiction services in India. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51:102086. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volkow ND. Collision of the COVID-19 and addiction epidemics. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:61–2. doi: 10.7326/M20-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunlop A, Lokuge B, Masters D, Sequeira M, Saul P, Dunlop G, et al. Challenges in maintaining treatment services for people who use drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17:26–7. doi: 10.1186/s12954-020-00370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvey T, Scheibein F, Saad NA, Shirasaka T, Dannatt L, Stowe M, et al. The changing landscape of alcohol use and alcohol use disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic-Perspectives of early career professionals in 16 countries. J Addict Med. 2020;14:e284–6. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Trana A, Carlier J, Berretta P, Zaami S, Ricci G. Consequences of COVID-19 lockdown on the misuse and marketing of addictive substances and new psychoactive substances. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:584462. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.584462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farhoudian A, Radfar SR, Mohaddes Ardabili H, Rafei P, Ebrahimi M, Zonoozi AK, et al. A Global Survey on Changes in the Supply, Price, and Use of Illicit Drugs and Alcohol, and Related Complications During the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:646206. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.646206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narasimha VL, Shukla L, Mukherjee D, Menon J, Huddar S, Panda UK, et al. Complicated alcohol withdrawal—An unintended consequence of COVID-19 lockdown. Alcohol Alcohol. 2020;55:350–3. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agaa042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossow I, Bye EK, Moan IS, Kilian C, Bramness JG. Changes in alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic—Small change in total consumption, but increase in proportion of heavy drinkers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:4231–2. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran TD, Hammarberg K, Kirkman M, Nguyen HT, Fisher J. Alcohol use and mental health status during the first months of COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:810–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huckle T, Parker K, Romeo JS, Casswell S. Online alcohol delivery is associated with heavier drinking during the first New Zealand COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021;40:826–34. doi: 10.1111/dar.13222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehm J, Kilian C, Ferreira-Borges C, Jernigan D, Monteiro M, Parry CD, et al. Alcohol use in times of the COVID 19:Implications for monitoring and policy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39:301–4. doi: 10.1111/dar.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh A, Choudhury S, Basu A, Mahintamani T, Sharma K, Pillai RR, et al. Extended lockdown and India's alcohol policy:A qualitative analysis of newspaper articles. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;85:102940. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh A, e-Roub F, Krishnan NC, Choudhury S, Basu A. Can google trends search inform us about the population response and public health impact of abrupt change in alcohol policy? A case study from India during the covid-19 pandemic. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;87:102984. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giommoni L. Why we should all be more careful in drawing conclusions about how COVID-19 is changing drug markets. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;83:102834. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta R, Arya S. Social analysis of the governmental-based health measures:A critique. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;36:126–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ambekar A, Agrawal A, Rao R, Mishra AK, Khandelwal SK. Magnitude of Substance Use in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India; 2019. [Last accessed on 2021 May 20]. on Behalf of the Group of Investigators for the National Survey on Extent and Pattern of Substance Use in India. Available from: https://socialjustice.gov.in/writereaddata/UploadFile/Survey%20Report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arya S, Ghosh A, Mishra S, Swami MK, Prasad S, Somani A, et al. A multicentric survey among patients with substance use disorders during the COVID-19 lockdown in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2022;64:48–55. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_557_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narasimha VL, Mukherjee D, Shukla L, Benegal V, Murthy P. Election bans and alcohol banes:The impact of elections on treatment referrals at a tertiary addiction treatment facility in India. Asian J Psychiatry. 2018;38:27–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2018.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupte H, Mandal G, Jagiasi D. How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected tobacco users in India:Lessons from an ongoing tobacco cessation program. Tob Prev Cessat. 2020;6:1–5. doi: 10.18332/tpc/127122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clancy L, Gallus S, Leung J, Egbe C. Tobacco and COVID-19:Understanding the science and policy implications. Tob Induc Dis. 2020;18:1–4. doi: 10.18332/tid/131035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.COVID-19 and Drug Markets Survey –Week One Summary, 2021. Available from: https://www.crew.scot/covid-drug-markets-survey-week-one/

- 24.Barratt MJ, Aldridge J. No magic pocket:Buying and selling on drug cryptomarkets in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and social restrictions. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;83:102894. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.United Nations Office of Drug and Crime, COVID-19 and the drug supply chain:From production and trafficking to use. 2020. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/covid/Covid-19-and-drug-supply-chain-Mai2020.pdf .