Abstract

Since vaccination remains the only effective protection against orthopox virus-induced diseases such as smallpox or monkeypox, the strategic use and stockpiling of these vaccines remains of significant public health importance. The approved liquid-frozen formulation of Bavarian Nordic's Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA-BN) smallpox vaccine has specific cold-chain requirements, while the freeze-dried (FD) formulation of this vaccine provides more flexibility in terms of storage conditions and shelf life.

In this randomized phase 3 trial, the immunogenicity and safety of 3 consecutively manufactured lots of the FD MVA-BN vaccine was evaluated. A total of 1129 healthy adults were randomized to 3 treatment groups (lots 1 to 3) and received 2 vaccinations 4 weeks apart.

For both neutralizing and total antibodies, a robust increase of geometric mean titer (GMT) was observed across all lot groups 2 weeks following the second vaccination, comparable to published data. For the primary results, the ratios of the neutralizing antibody GMTs between the lot group pairs ranged from 0.936 to 1.115, with confidence ratios well within the pre-specified margin of equivalence. Results for total antibodies were similar. In addition, seroconversion rates were high across the 3 lots, ranging between 99.1 % and 99.7 %.

No safety concerns were identified; particularly, no inflammatory cardiac disorders were detected. The most common local solicited adverse events (AEs) reported across lot groups were injection site pain (87.2%) and erythema (73.2%), while the most common general solicited adverse events were myalgia, fatigue, and headache in 40.6% to 45.5% of all participants, with no meaningful differences among the lot groups. No related serious AEs were reported.

In conclusion, the data demonstrate consistent and robust immunogenicity and safety results with a freeze-dried formulation of MVA-BN.

Clinical Trial Registry Number: NCT03699124.

Keywords: Vaccine, Smallpox, Monkeypox, Orthopoxvirus, Freeze-dried, MVA-BN, Modified vaccinia Ankara, Lot consistency

1. Introduction

While the efforts of global vaccination campaigns using vaccinia-based vaccines succeeded in eradicating smallpox in 1980 [1], [2], the strategic use and storage of these vaccines is of continued public health importance. Large national vaccine stockpiles are maintained by countries around the world as a means of protecting against the intentional release of smallpox virus in an act of bioterrorism [3], [4]. Smallpox vaccination also is recommended for individuals at risk for occupational exposure, including certain healthcare professionals, laboratory workers [5] and military personnel [6]. Additionally, protection against other related orthopoxviruses, such as monkeypox, can be provided through vaccinia-based smallpox vaccines [5], [7]. This use of smallpox vaccine remains highly relevant because human monkeypox infections appear to have increased over the past decade, with the potential for human-to-human spread [8], [9], [10], [11]. In response to monkeypox, vaccinia-based vaccines have been administered as part of a clinical trial in areas of Africa where the virus is endemic [12] and in countries, like the United Kingdom, where travelers have presented with monkeypox disease [13], [14] and transmitted it to others upon their return [15].

Bavarian Nordic A/S produces a smallpox vaccine that is based upon the highly attenuated modified vaccinia Ankara strain (MVA-BN). As of January 2022, the liquid-frozen formulation of MVA-BN is registered in Europe for active immunization against smallpox in adults (tradename: IMVANEX®), in the US for the prevention of smallpox and monkeypox disease in adults at high risk for infection (tradename: JYNNEOS®) and in Canada for active immunization against smallpox, monkeypox, and related orthopoxvirus infection and disease (tradename: IMVAMUNE®).

MVA-BN has been attenuated to the point of being unable to replicate in mammals and has a superior safety profile compared to other replication-competent vaccinia-based smallpox vaccines. Such other live vaccines (e.g., ACAM2000) are associated with increased incidences of acute myo-/pericarditis (∼1:200) and cardiac-related adverse events such as dyspnea at rest (∼1:100) [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. In contrast, no confirmed cases of inflammatory cardiac disease have been observed following administration of MVA-BN to nearly 8000 clinical trial participants at the time of US licensure in 2019 [21], [22]. Also, unlike other approved smallpox vaccines, MVA-BN has a favorable safety profile for individuals with atopic dermatitis [23], [24] and immunodeficiency [25], [26], [27]. Thus, the MVA-BN vaccine addresses a number of safety concerns that limit the use of previous generations of smallpox vaccines [21], [22].

To enhance both the long-term storage and the ease of distribution of smallpox vaccine stockpiles, a freeze-dried (FD) formulation of MVA-BN was developed. Previous trials using MVA-BN have demonstrated noninferior immune responses and comparable safety profiles between lyophilized and liquid frozen formulations [28], [29]. Assessments of the long-term stability of the freeze-dried formulation (FD MVA-BN) are ongoing.

In this report, FD MVA-BN is further characterized by assessing the consistency of immunogenicity across 3 consecutively produced vaccine lots. This phase 3 lot-to-lot consistency trial not only provides valuable insight into the reliability of the freeze-dried formulation manufacturing process but also allows for further characterization of the safety and reactogenicity of FD MVA-BN in over 1000 clinical trial participants.

2. Methods

2.1. Trial design

This was a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, phase 3 trial conducted at 12 sites in the United States over an approximately 1-year period, ending in 2020. All trial-related procedures were conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the relevant institutional review boards (IRBs) at each site.

The primary objective of the trial was to show the consistency of neutralizing antibody immune responses to 3 consecutively produced lots of FD MVA-BN. The secondary objectives were to assess uncommon adverse reactions, with a focus on cardiac signs and symptoms indicating myo-/pericarditis, and to collect additional humoral immune response data. It was planned that approximately 1110 adults would be randomized (1:1:1) to receive treatment with 1 of 3 FD MVA-BN production lots (Lot Groups 1, 2, and 3) using an automated randomization system stratified by clinical trial site. Participants in each Lot Group received 1 injection at Week 0 and again at Week 4.

2.2. Participants

Healthy men and women between 18 and 45 years of age, without a medical history of autoimmune or coronary heart disease, were eligible if they had a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 18.5 and < 35 kg/m2, an electrocardiogram (ECG) without clinically significant findings, hematology and chemistry laboratory values within prespecified normal limits, total bilirubin levels ≤ 1.5 times the upper limit of normal in the absence of evidence of significant liver disease, and no prior smallpox vaccination. Participants with an immediate family member who experienced an onset of ischemic heart disease prior to 50 years of age were also excluded, along with participants who had abused alcohol or illicit drugs within 6 months of screening. Women of childbearing potential were instructed to use an acceptable method of contraception, could not be actively breastfeeding, and were required to have a negative pregnancy test at screening and on each vaccination day.

2.3. Vaccine

MVA-BN is a highly attenuated, purified, live, vaccinia-based vaccine [30]. The FD MVA-BN bulk drug substance was produced at Bavarian Nordic A/S (Kvistgård, Denmark) according to GMP standards, and the final drug product was filled, formulated, and labeled by IDT Biologika GmbH (Dessau-Rosslau, Germany). The freeze-dried vaccine was provided as lyophilized aliquots with a nominal virus titer of 1 × 108 Inf.U/0.5 mL dose. Clinical site personnel reconstituted each aliquot with 0.65 mL of water for injection (WFI) and then administered 0.5 mL subcutaneously in the upper (deltoid) region of the subject's nondominant arm. Participants in each lot group received both of their injections from the same batch (C00020, C00021, and C00022 for Lot Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively). FD MVA-BN was shipped and stored between –25 °C and –15 °C (-13°F to +5°F) and WFI was shipped separately at 20 °C to 25 °C (68°F to 77°F) and then stored between 15 °C and 30 °C (59°F to 86°F) at the clinical site prior to use.

2.4. Immunogenicity assessments

Immunogenicity parameters to assess lot-to-lot consistency included total and neutralizing antibody GMTs; seroconversion rates; the ratio, or consistency, of GMTs between group lot pairs; and a correlation analysis between total and neutralizing antibody titers in each lot group. Total serum antibodies were measured using a vaccinia-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and neutralizing antibodies were measured using a vaccinia-specific plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT). Samples for these assessments were drawn at baseline (Week 0) and 2 weeks after the second FD MVA-BN vaccination (Week 6). This postvaccination assessment timepoint was chosen because peak antibody titers are consistently observed 2 weeks following the second vaccination in individuals who have not been previously vaccinated against smallpox [24], [26], [31], [32], [33]. The PRNT and ELISA antigens were Western Reserve and MVA, respectively. Both methods were validated and were performed as previously described for a prior phase 2 trial [26] with the following modifications: For the ELISA, an optical density cut-off value of 0.35 was used, and for the PRNT, the neutralization was performed in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/0.1 % human serum albumin. The lower limits of quantification (LLOQs) for the ELISA and PRNT assays were 200 and 20, respectively.

2.5. Safety assessments

Assessments of solicited and unsolicited adverse events were used to characterize the overall safety and reactogenicity of FD MVA-BN and to make comparisons across lot groups. Solicited adverse events constituted a set of pre-defined, expected local reactions (erythema, swelling, pruritus, induration and pain) as well as general events (elevated body temperature, headache, chills, myalgia, nausea and fatigue) listed on a memory aid. This memory aid was provided to participants for 2 solicitation periods of 8 days each, which included each vaccination day and the week that followed. Intensity of solicited adverse events was graded according to prespecified criteria defined for each local and general event. All local solicited events were considered related to trial vaccine, while relatedness of general events was assessed by the investigator.

Unsolicited events were collected from the day the first vaccine was administered (at Week 0) until 4 weeks following the last vaccination (overall vaccination period) and consisted of any adverse event that was either not listed on the memory aid or had occurred outside the 8–day solicitation periods. Any unsolicited adverse events ongoing 4 weeks following the last vaccination were followed until resolution or until the 6-month follow-up visit. Both the intensity of the event and its relationship to the trial vaccine were assessed by the investigator. Any SAEs or adverse events of special interest (AESIs) experienced during the 6-month follow–up period were also collected.

As a precaution, AESIs in this trial were defined as any: (1) cardiac symptoms, (2) clinically significant ECG changes, or (3) troponin I values that were above the upper limit of normal and developed since the first vaccination. Participants developing an AESI were to return for physical and cardiac examinations or further diagnostic tests, if clinically indicated, and were followed up until resolution or stabilization, or until the end of the 6-month follow-up period.

Safety hematology and chemistry laboratory tests were performed at screening and 2 weeks after each vaccination, and—if clinically indicated—at any other visit.

2.6. Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS-Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

A simulation was performed to estimate the required number of analyzable participants per group based on several underlying assumptions. A two-sided 95 % significance level was used, and assumptions of within- and between-lot variability were made based on prior data. An equivalence margin (Δ), within which the difference between lots would be considered equivalent, of ± 0.301 on the log10 scale (a 2-fold difference) was assumed. An analyzable sample size of 315 participants in each group was calculated to yield a power of at least 90 % to show equivalence for all 3 FD MVA-BN lot groups. In order to account for a dropout rate of about 15 %, observed in previous MVA-BN trials, a total of 370 participants was planned for each group.

Analyses of immunogenicity endpoints were based on the per protocol set (PPS), which included those who received all vaccinations and adhered to the protocol without major deviations with the potential to substantially affect the immunogenicity results. Geometric mean titers (GMTs), or the antilogarithms of the means of the log10 titer transformations, were calculated for neutralizing antibodies (measured by PRNT) and total antibodies (measured by ELISA) at baseline and 2 weeks following the second vaccination. For titers that were below the limit of quantification (LLOQ), a value of half the LLOQ was assigned for calculation purposes.

The primary analysis is presented as GMT ratios between lot groups and their 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). The primary endpoint of equivalence between any 2 lot groups was defined as a CI around the ratio of the GMTs, measured 2 weeks after the second vaccination, that was within the prespecified margin of equivalence of 0.5 to 2. The secondary outcome of total antibody titers was analyzed using the same method of comparison and likewise presented as GMT ratios and confidence intervals.

A sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome was repeated on the Full Analysis Set (FAS) using multiple imputation (MI) for missing data, assuming titer values were missing at random and lognormally distributed. Year of birth, sex, and race were used as predictors. MI was used to create 100 complete sets of results that accounted for the random variability in titer values. The log-transformed differences and associated standard errors were combined over the imputations and then back-transformed to the original scale.

Seroconversion in this trial was defined as either the appearance of antibody levels ≥ LLOQ for participants who had a titer level below LLOQ at baseline, or a doubling (or more) of the antibody titer compared to baseline for participants who had a titer ≥ LLOQ at baseline.

Analyses of safety endpoints were based on the FAS, comprised of all randomized participants who received at least 1 vaccination. Safety data were summarized descriptively, and unsolicited adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 22.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics and characteristics

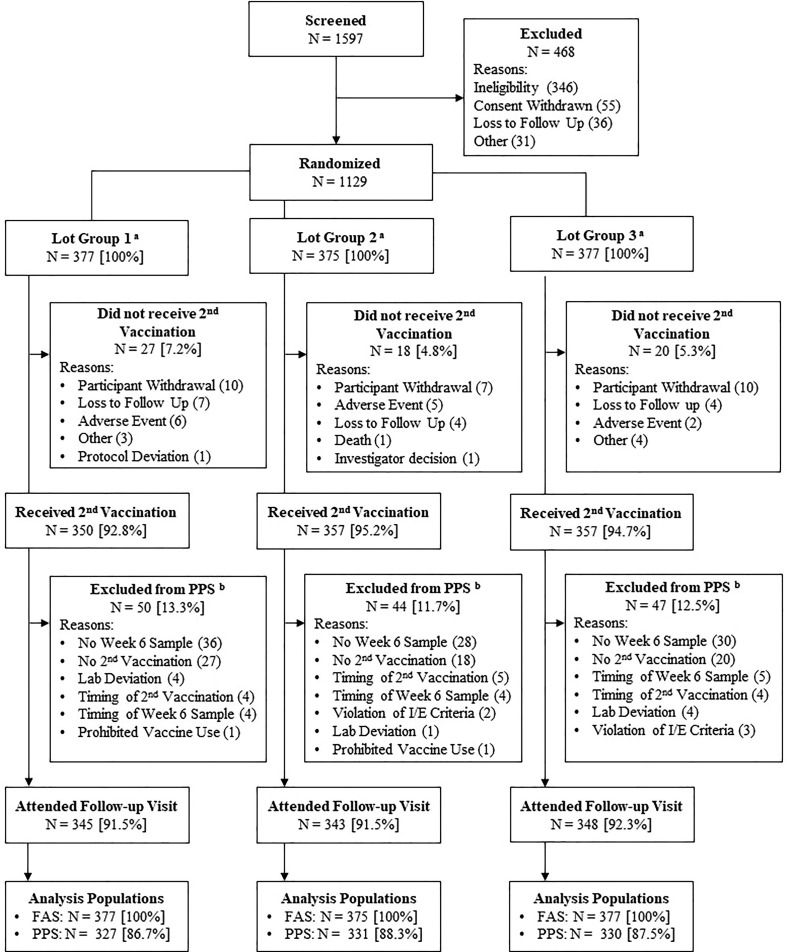

A total of 1129 participants were randomized, with 377 participants in Lot Group 1, 375 participants in Lot Group 2, and 377 participants in Lot Group 3 (Fig. 1 ). All randomized participants received the first vaccination and were included in the FAS for evaluation of safety. Across lot groups, the majority of participants also received the second vaccination (92.8 % to 95.2 %), with participant-elected withdrawal being the most common reason for having an incomplete immunization schedule. Very few participants did not receive the second vaccination due to an adverse event. Of those who received both vaccinations, the most common reason for exclusion from the PPS immunogenicity analyses was not having a serum sample collected 2 weeks following the second vaccination (at Week 6). However, most participants across lot groups were included in the immunogenicity analyses (86.7 % to 88.3 %) and attended the follow-up visit (91.5 % to 92.3 %).

Fig. 1.

Subject Disposition (All Participants) Abbreviations: FAS = full analysis set; I/E = inclusion/exclusion criteria; PPS = per protocol set. Note: Participants excluded on account of timing were either vaccinated or had serum draws at timepoints substantially outside the timeframe specified in the protocol. a All randomized participants received the first dose of trial vaccine and were included in the FAS for the purpose of evaluating safety. b Some participants may have been excluded from the PPS for more than one reason; thus, the individual reason counts may add up to be more than the total number of participants excluded.

The demographic and baseline medical history characteristics across lot groups was comparable (Table1 ). Overall, the median age of participants was 30.0 years, with 52.6 % of all volunteers falling in the age range of > 18 to 30 years, and 55.8 % of participants were female. Most participants were either of White (77.9 %) or Black or African American (15.2 %) race, and predominantly not Hispanic or Latino (93.1 %) ethnicity. Overall, in this generally healthy adult population, the most common medical history conditions were anxiety (17.2 %), seasonal allergy (17.0 %), depression (16.3 %), and history of drug hypersensitivity (13.8 %). No participants had a known history of receiving a smallpox vaccine or a poxvirus-based vaccine or had a typical vaccinia scar.

Table 1.

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics (Full Analysis Set).

| Characteristic Statistic |

Lot Group 1 (N = 377) |

Lot Group 2 (N = 375) |

Lot Group 3 (N = 377) |

Overall (N = 1129) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Informed Consent (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 30.7 (7.31) | 30.6 (7.29) | 30.7 (7.50) | 30.7 (7.36) |

| Min, Max | 18, 45 | 18, 45 | 18, 45 | 18, 45 |

| Age Group (years), n (%) | ||||

| 18 to 30 | 203 (53.8) | 196 (52.3) | 195 (51.7) | 594 (52.6) |

| > 30 to 45 | 174 (46.2) | 179 (47.7) | 182 (48.3) | 535 (47.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 210 (55.7) | 213 (56.8) | 207 (54.9) | 630 (55.8) |

| Male | 167 (44.3) | 162 (43.2) | 170 (45.1) | 499 (44.2) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 26.56 (4.367) | 26.48 (4.476) | 26.36 (4.389) | 26.47 (4.408) |

| Min, Max | 18.5, 34.9 | 18.5, 34.8 | 18.5, 35.1 | 18.5, 35.1 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 292 (77.5) | 295 (78.7) | 293 (77.7) | 880 (77.9) |

| Black or African American | 58 (15.4) | 55 (14.7) | 59 (15.6) | 172 (15.2) |

| Asian | 17 (4.5) | 13 (3.5) | 13 (3.4) | 43 (3.8) |

| Other | 7 (1.9) | 9 (2.4) | 8 (2.1) | 24 (2.1) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (1.1) | 8 (0.7) |

| Pacific Islandera | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (0.2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 348 (92.3) | 354 (94.4) | 349 (92.6) | 1051 (93.1) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 28 (7.4) | 20 (5.3) | 25 (6.6) | 73 (6.5) |

| Not Reported | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.8) | 5 (0.4) |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; BMI = body mass index; SD = standard deviation; N = number of participants in the specified group; n = number of participants within a specified group (N); %, percentage based on N.

Including Native Hawaiian.

3.2. Immunogenicity results

As expected in an unvaccinated population, most participants did not have detectable vaccinia-specific neutralizing and/or total antibody levels at baseline (97.8 % and 99.5 %, respectively). Those with neutralizing or total antibody levels at or above the LLOQ were roughly evenly distributed across lot groups (Table2 ).

Table 2.

Antibody Titers and Ratios Between Groups at 2 Weeks After the Second Vaccination (Per Protocol Set).

|

Lot Group 1 (N = 327) |

Lot Group 2 (N = 331) |

Lot Group 3 (N = 330) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutralizing Antibodies (Assessed by PRNT) | |||

| Baseline, n | 326 | 331 | 330 |

| <LLOQ, n (%) | 321 (98.5) | 322 (97.3) | 322 (97.6) |

| 2 Weeks After Second Vaccination (Visit 4), n | 327 | 331 | 330 |

| GMT | 252.7 | 269.9 | 242.0 |

| 95 % CI [LCL, UCL] | [231.3, 276.0] | [243.2, 299.7] | [219.5, 266.8] |

| GMT Ratio Compared to Group 3 | 1.044 | 1.115 | |

| 95 % CI [LCL, UCL] | [0.915, 1.191] | [0.967, 1.287] | |

| Equivalence Meta | Yes | Yes | |

| GMT Ratio Compared to Group 2 | 0.936 | ||

| 95 % CI [LCL, UCL] | [0.816, 1.073] | ||

| Equivalence Met a | Yes | ||

| Total Antibodies (Assessed by ELISA) | |||

| Baseline, n | 326 | 331 | 330 |

| <LLOQ, n (%) | 324 (99.4) | 329 (99.4) | 329 (99.7) |

| 2 Weeks After Second Vaccination (Visit 4), n | 327 | 331 | 330 |

| GMT | 1222.0 | 1311.0 | 1226.1 |

| 95 % CI [LCL, UCL] | [1123.3, 1329.4] | [1195.7, 1437.5] | [1118.1, 1344.6] |

| GMT Ratio compared to Group 3 | 0.997 | 1.069 | |

| 95 % CI [LCL, UCL] | [0.880, 1.129] | [0.939, 1.218] | |

| GMT Ratio compared to Group 2 | 0.932 | ||

| 95 % CI [LCL, UCL] | [0.823, 1.056] | ||

Abbreviations: CI = Confidence Interval; ELISA = Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay; LCL = Lower Confidence Limit; LLOQ = Lower Limit of Quantitation; N = number of subjects in the PPS in the specified group; n = number of subjects with available titer values; PRNT = Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test; UCL = Upper Confidence Limit.

Note: Geometric means were calculated using the mean of the log10 transformed titer values, with corresponding 95% CIs based on a t-test.

Note: Antibody titers below the LLOQ were given a value of half of the LLOQ. The LLOQ was 20 for PRNT and 200 for ELISA.

Equivalence (only assessed for neutralizing antibodies) was met if the LCL > 1/2 and UCL < 2 for PRNT.

Two weeks following the second vaccination (at Week 6), neutralizing antibody GMTs had increased from non-detectable to 252.7 for Lot Group 1, 269.9 for Lot Group 2, and 242.0 for Lot Group 3. The ratios of GMTs between lot group combinations ranged between 0.936 and 1.115, with 95 % confidence limits ranging between 0.816 and 1.287. Since the CIs of the neutralizing antibody GMT ratios all fell within the prespecified interval of 0.5 to 2.0, the lot groups were considered equivalent, and the primary endpoint of the trial was met. The sensitivity analysis on the FAS using multiple imputation to compensate for missing values yielded ratios of neutralizing antibody GMTs between the lot groups that were closer to 1 than the results for the PPS. Values ranged between 0.947 and 1.095, and all CIs were within the interval of 0.5 to 2.0.

Similar findings were observed for total antibodies, with a response observed 2 weeks following the second vaccination of GMTs ranging from 1222.0 to 1311.0 across lot groups. Although equivalence was not formally assessed for this secondary endpoint, the ratios of GMTs between lot groups and their 95 % CIs were in the same range as the primary endpoint (Table2).

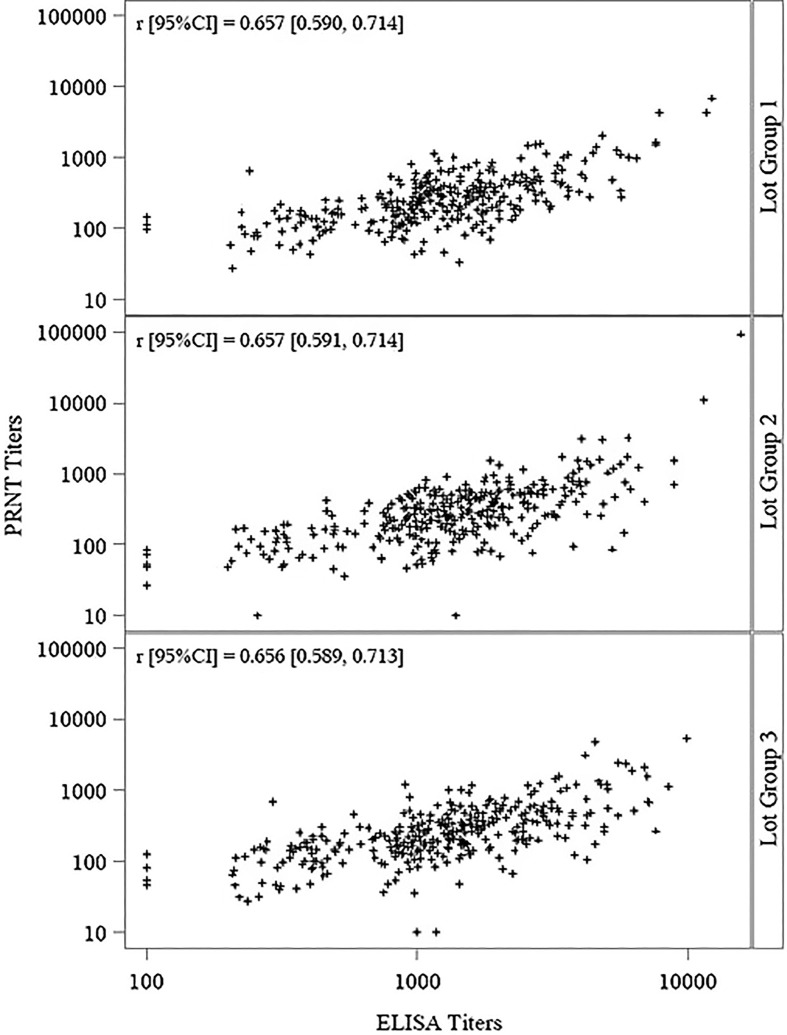

Seroconversion rates 2 weeks following the second vaccination were above 98.0 % for both neutralizing and total antibodies in all groups, with no statistically significant differences among the 3 lot groups for neutralizing and total antibodies (p = 0.7102 and p = 0.6916, respectively) (Table3 ). Total and neutralizing antibody levels were highly correlated within each of the lot groups (Fig. 2 ). Pearson correlation coefficients (r values) ranged between 0.656 and 0.657, with p-values < 0.0001 for each lot group and overall.

Table 3.

Seroconversion Rates 2 Weeks Following the Second Vaccination (Per Protocol Set).

| Sampling Time Point |

Lot Group 1 (N = 327) |

Lot Group 2 (N = 331) |

Lot Group 3 (N = 330) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutralizing Antibodies (Assessed by PRNT), n | 326 | 331 | 330 |

| Seroconversion, n (%) | 325 (99.7) | 328 (99.1) | 327 (99.1) |

| 95 % CI [LCL, UCL] | [98.3, 100.0] | [97.4, 99.8] | [97.4, 99.8] |

| p-valuea | 0.7102 | ||

| Total Antibodies (Assessed by ELISA), n | 326 | 331 | 330 |

| Seroconversion, n (%) | 323 (99.1) | 325 (98.2) | 326 (98.8) |

| 95 % CI [LCL, UCL] | [97.3, 99.8] | [96.1, 99.3] | [96.9, 99.7] |

| p-valuea | 0.6916 | ||

Abbreviations: CI = Confidence Interval; ELISA = Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay; LCL = Lower Confidence Limit; LLOQ = Lower Limit of Quantitation; N = number of subjects in the specified group; n = number of subjects with available titer values; PRNT = Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test; UCL = Upper Confidence Limit.

Seroconversion was defined as either the appearance of antibody titers ≥ LLOQ for subjects with a titer below LLOQ at baseline, or a doubling (or more) of the antibody titer compared to the baseline titer for subjects with a titer equal or above the LLOQ at baseline.

The LLOQ for PRNT was 20 and 200 for ELISA.

95% CI: Clopper-Pearson 95% 2-sided confidence intervals for the proportion of seroconverted subjects.

Comparison of Lot Groups 1 to 3 using Freeman-Halton exact test.

Fig. 2.

Correlation Between Total and Neutralizing Antibodies (Per Protocol Set) Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; ELISA = Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay; PRNT = Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test. Notes: Values below the LLOQ for each method were imputed to half the value of the LLOQ. Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was calculated on the log10 titers.

3.3. Safety results

Local solicited AEs were experienced by 91.2 % of all participants. (Table4 ). The most common local solicited AEs were injection site pain and injection site erythema reported for 87.2 % and 73.2 % of all participants, respectively (Table6). Across all local solicited AEs categories, <12.0 % were of Grade 3 intensity, with the longest mean duration being 15.6 days for injection site induration and all other events having mean durations ranging from 4.6 to 6.9 days. Across all local solicited AEs categories, the mean duration was longer following the first vaccination (4.7 to 18.4 days) compared to after the second vaccination (3.7 to 5.5 days). Most prominently, the mean duration for injection site induration after the first vaccination (18.4 days) was longer compared to after the second vaccination (5.5 days).

Table 4.

Summary of Solicited and Unsolicited Adverse Events for the Overall Vaccination Period (Full Analysis Set).

|

Lot Group 1 (N = 377) n (%) [events] |

Lot Group 2 (N = 375) n (%) [events] |

Lot Group 3 (N = 377) n (%) [events] |

Overall (N = 1129) n (%) [events] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsolicited AEs | 88 (23.3) [1 4 3] | 110 (29.3) [1 7 2] | 98 (26.0) [1 6 2] | 296 (26.2) [4 7 7] |

| Relateda | 33 (8.8) [58] | 38 (10.1) [54] | 37 (9.8) [48] | 108 (9.6) [1 6 0] |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 6 (1.6) [7] | 8 (2.1) [10] | 7 (1.9) [10] | 21 (1.9) [27] |

| Grade ≥ 3 Related | 2 (0.5) [2] | 0 | 1 (0.3) [1] | 3 (0.3) [3] |

| Led to Withdrawal from Second Vaccination | 6 (1.6) [11] | 4 (1.1) [5] | 2 (0.5) [7] | 12 (1.1) [23] |

| Led to Trial Withdrawal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatal | 0 | 1 (0.3) [1] | 0 | 1 (0.1) [1] |

| Local Solicited AEsb | 338 (89.7) [1967] | 348 (92.8) [2082] | 344 (91.2) [2025] | 1030 (91.2) [6074] |

| Led to Vaccine Deferral | 1 (0.3) [1] | 0 | 1 (0.3) [1] | 2 (0.2) [2] |

| Led to Vaccine Discontinuation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General Solicited AEsc | 253 (67.1) [8 1 1] | 267 (71.2) [9 1 2] | 266 (70.6) [9 1 5] | 786 (69.6) [2638] |

| Relateda | 246 (65.3) [7 7 3] | 256 (68.3) [8 4 9] | 252 (66.8) [8 3 4] | 754 (66.8) [2456] |

| Led to Vaccine Deferral | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.8) [3] | 3 (0.3) [3] |

| Led to Vaccine Discontinuation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serious Adverse Events | 1 (0.3) [1] | 3 (0.8) [3] | 1 (0.3) [1] | 5 (0.4) [5] |

| Relateda | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 0 | 2 (0.5) [2] | 1 (0.3) [1] | 3 (0.3) [3] |

|

Cardiac AEs of Special Interestd |

2 (0.5) [2] | 3 (0.8) [3] | 1 (0.3) [3] | 6 (0.5) [8] |

| Relateda | 0 | 1 (0.3) [1] | 0 | 1 (0.1) [1] |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 1 (0.3) [1] | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) [1] |

Abbreviations: AE = Adverse Event; ECG = Electrocardiogram; N = number of subjects in the specified group; n = number of subjects reporting an AE in the specified category.

Note: This summary includes all AEs, SAEs, AESIs, Grade ≥ 3 AEs, and fatalities reported during the overall vaccination period only. The overall vaccination period is the time from first vaccination through the second vaccination + 35 days or the date of the last visit, whichever is later. Adverse events are presented separately for the two vaccination periods and additionally for the follow-up period in the Supplemental Materials.

Related AEs were either considered at least possibly related to trial vaccine by the investigator or had missing information pertaining to relatedness.

Local solicited AEs included redness, swelling, induration, pruritus, and pain within 8 days after each vaccination. All local solicited AEs were considered related to trial vaccine, as defined in the protocol.

General solicited AEs included pyrexia, headache, myalgia, chills, nausea, and fatigue within 8 days after each vaccination. General solicited AEs were considered related when the investigator considered them at least possibly related to vaccination or when information on relatedness was missing.

Cardiac AEs of special interest were defined as any cardiac sign or symptom that developed after the first vaccination, including ECG changes determined to be clinically significant and cardiac enzyme troponin I levels above the upper limit of normal. These were the only AEs of special interest defined in this trial.

Table 6.

Summary of Solicited Adverse Events (Full Analysis Set).

|

Lot Group 1 (N = 377) n (%) |

Lot Group 2 (N = 375) n (%) |

Lot Group 3 (N = 377) n (%) |

Overall (N = 1129) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Solicited Adverse Events | ||||

| Injection Site Pain, n (%) | 325 (86.2) | 330 (88.0) | 329 (87.3) | 984 (87.2) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 46 (12.2) | 45 (12.0) | 43 (11.4) | 134 (11.9) |

| Mean Duration, days [SD] | 6.9 [4.41] | 7.1 [4.44] | 6.7 [3.64] | 6.9 [4.18] |

| Injection Site Erythemaa, n (%) | 271 (71.9) | 283 (75.5) | 272 (72.1) | 826 (73.2) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 44 (11.7) | 42 (11.2) | 29 (7.7) | 115 (10.2) |

| Mean Duration, days [SD] | 7.1 [6.53] | 6.5 [5.06] | 6.6 [5.39] | 6.7 [5.68] |

| Injection Site Swellinga, n (%) | 215 (57.0) | 233 (62.1) | 236 (62.6) | 684 (60.6) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 17 (4.5) | 25 (6.7) | 12 (3.2) | 54 (4.8) |

| Mean Duration, days [SD] | 6.7 [6.47] | 6.0 [5.04] | 5.9 [4.52] | 6.2 [5.38] |

| Injection Site Indurationa, n (%) | 215 (57.0) | 226 (60.3) | 229 (60.7) | 670 (59.3) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 11 (2.9) | 8 (2.1) | 6 (1.6) | 25 (2.2) |

| Mean Duration, days [SD] | 18.0 [24.04] | 13.9 [13.12] | 15.0 [15.01] | 15.6 [17.94] |

| Injection Site Pruritus, n (%) | 210 (55.7) | 230 (61.3) | 198 (52.5) | 638 (56.5) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 10 (2.7) | 7 (1.9) | 10 (2.7) | 27 (2.4) |

| Mean Duration, days [SD] | 5.0 [5.70] | 4.4 [3.24] | 4.4 [3.87] | 4.6 [4.37] |

| General Solicited Adverse Events | ||||

| Myalgia, n (%) | 166 (44.0) | 173 (46.1) | 175 (46.4) | 514 (45.5) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 13 (3.4) | 10 (2.7) | 20 (5.3) | 43 (3.8) |

| Mean Duration, days [SD] | 4.1 [2.80] | 4.0 [3.27] | 4.1 [3.30] | 4.1 [3.13] |

| Fatigue, n (%) | 140 (37.1) | 171 (45.6) | 171 (45.4) | 482 (42.7) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 15 (4.0) | 13 (3.5) | 14 (3.7) | 42 (3.7) |

| Mean Duration, days [SD] | 3.9 [5.16] | 3.1 [2.70] | 3.6 [3.57] | 3.5 [3.86] |

| Headache, n (%) | 146 (38.7) | 157 (41.9) | 155 (41.1) | 458 (40.6) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 14 (3.7) | 11 (2.9) | 10 (2.7) | 35 (3.1) |

| Mean Duration, days [SD] | 3.2 [2.85] | 3.1 [2.49] | 3.2 [3.59] | 3.2 [3.01] |

| Nausea, n (%) | 75 (19.9) | 81 (21.6) | 78 (20.7) | 234 (20.7) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 6 (1.6) | 6 (1.6) | 6 (1.6) | 18 (1.6) |

| Mean Duration, days [SD] | 2.6 [2.98] | 2.7 [2.76] | 2.7 [2.50] | 2.6 [2.74] |

| Body Temperature Increasedb, n (%) | 47 (12.5) | 60 (16.0) | 63 (16.7) | 170 (15.1) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | 6 (0.5) |

| Mean Duration, days [SD] | 2.3 [1.87] | 1.9 [1.91] | 1.9 [1.92] | 2.0 [1.90] |

| Chills, n (%) | 58 (15.4) | 54 (14.4) | 57 (15.1) | 169 (15.0) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 5 (1.3) | 4 (1.1) | 6 (1.6) | 15 (1.3) |

| Mean Duration, days [SD] | 2.3 [2.01] | 2.3 [2.71] | 2.3 [2.19] | 2.3 [2.30] |

Abbreviations: N = number of participants in the specified group; n = number of participants reporting an AE in the specified category.

For injection site erythema, swelling, and induration, the intensity was graded based on the maximum diameter: Grade 0 (none): 0 mm, Grade 1: < 30 mm, Grade 2: ≥ 30 to < 100 mm, Grade 3: ≥ 100 mm.

For body temperature increased, intensity was graded as: Grade 0 (none): < 99.5⁰F (or < 37.5⁰C), Grade 1: ≥ 99.5⁰F to < 100.4⁰F (or ≥ 37.5°C to < 38.0°C), Grade 2: ≥ 100.4⁰F to < 102.2⁰F (or ≥ 38.0⁰C to < 39.0⁰C), Grade 3: ≥ 102.2⁰F to < 104.0⁰F (or ≥ 39.0⁰C to < 40.0⁰C), Grade 4: ≥ 104.0⁰F (or ≥ 40.0⁰C).

General solicited AEs were experienced by 69.6 % of all participants during the overall vaccination period, with nearly all events considered related to trial vaccine (Table4). The most common general solicited AEs were myalgia, fatigue, and headache in 40.6 % to 45.5 % of all participants (Table6). Across all general solicited AEs categories, <4.0 % were of Grade 3 intensity, with mean durations between 2.0 and 4.1 days. The mean duration of general solicited AEs was slightly longer after the first vaccination (2.0 to 4.3 days) compared to after the second vaccination (1.8 to 3.2 days).

Unsolicited AEs were reported for 26.2 % of all participants during the overall vaccination period (the time from the first vaccine dose until the last visit or 35 days after the second vaccine dose, whichever is later), with 9.6 % experiencing events considered at least possibly related to the vaccine by the investigator (Table4). Grade 3 and higher unsolicited AEs were reported for 1.9 % of participants, with 0.3 % having events of this intensity deemed related to trial vaccine. Overall, the most common unsolicited adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection (5.8 %), injection site nodule (2.9 %), and an increase in blood potassium (2.4 %). All other adverse events were experienced by 1.3 % or fewer of the overall trial population (Table5 ). A slightly higher proportion of all participants reported unsolicited AEs after the first vaccination (18.1 %) as compared to after the second vaccination (13.5 %).

Table 5.

Most Common Unsolicited Adverse Events for the Overall Vaccination Period (Full Analysis Set).

| Preferred Term |

Lot Group 1 (N = 377) n (%) [events] |

Lot Group 2 (N = 375) n (%) [events] |

Lot Group 3 (N = 377) n (%) [events] |

Overall (N = 1129) n (%) [events] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 19 (5.0) [19] | 25 (6.7) [26] | 21 (5.6) [23] | 65 (5.8) [68] |

| Injection site nodule | 11 (2.9) [11] | 10 (2.7) [10] | 12 (3.2) [12] | 33 (2.9) [33] |

| Blood potassium increased | 6 (1.6) [6] | 11 (2.9) [11] | 10 (2.7) [10] | 27 (2.4) [27] |

| Injection site discoloration | 3 (0.8) [3] | 5 (1.3) [5] | 7 (1.9) [7] | 15 (1.3) [15] |

| Injection site bruising | 5 (1.3) [5] | 4 (1.1) [4] | 3 (0.8) [3] | 12 (1.1) [12] |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 (0.3) [1] | 4 (1.1) [4] | 4 (1.1) [4] | 9 (0.8) [9] |

| Vaccination site bruising | 2 (0.5) [2] | 3 (0.8) [4] | 2 (0.5) [2] | 7 (0.6) [8] |

| Anxiety | 2 (0.5) [2] | 2 (0.5) [2] | 2 (0.5) [3] | 6 (0.5) [7] |

| Ligament sprain | 4 (1.1) [4] | 1 (0.3) [1] | 1 (0.3) [1] | 6 (0.5) [6] |

| Pyrexia | 0 | 3 (0.8) [3] | 3 (0.8) [3] | 6 (0.5) [6] |

Abbreviations: N = number of subjects in the specified group; n = number of subjects reporting an adverse event in the specified Preferred Term category.

A total of 9 serious AEs (SAEs) were experienced by 9 participants (0.8 %) across the 3 lots, 5 (0.4 %) during the overall vaccination period (Table4) and 4 (0.4 %) during the follow-up period (Supplemental Materials), with none considered related to trial vaccine. Those SAEs that occurred during the overall vaccination period included events of depression, colitis, foot deformity, and alcoholic pancreatitis. Also, a 44-year-old male with a medical history of asthma died of unknown causes 28 days after the first vaccination. During the 6-month follow-up period, SAEs included groin abscess, panic attack, and spontaneous abortion, and a 37-year-old male died of unknown causes 167 days after the last vaccination. All non-fatal SAEs had resolved by the time of the last follow-up assessment.

One pregnancy occurred approximately 7 days after a participant received a second vaccination and resulted in a live birth.

A total of 8 cardiac-related AEs of special interest (AESIs) were experienced during the overall vaccination period by 6 participants (0.5 % across the 3 lots) (Table4). Importantly, no inflammatory cardiac disorders were observed. One participant with a medical history of dyspnea, allergic rhinitis, and heart murmur experienced a Grade 2 event of exertional dyspnea 6 days after receiving the first vaccination. The participant had not reported any symptoms of dyspnea at screening. While the investigator assessed this event as possibly related to trial vaccine, the sponsor considered the relationship unlikely. Concomitant medication and medical history suggested that exertional dyspnea had been a repeated symptom for this subject, and the 6-day period between vaccination and respiratory symptom onset did not clearly suggest a causal relationship. All other cardiac-related AESIs were considered unrelated to trial vaccine by both the investigator and the sponsor. The outcomes of all AESIs were reported as resolved, with the exception of one case of supraventricular extrasystoles in a participant who was lost to follow-up.

Withdrawal from the second vaccination occurred due to unsolicited AEs in only 1.1 % of all participants, with no participants withdrawing from the second vaccination on account of solicited AEs (Table4). No AEs led to withdrawal from the trial, and there were no meaningful differences in solicited or unsolicited AEs across lot groups.

4. Discussion

Vaccines stand as one of the greatest achievements of modern medicine to improve public health. Even so, vaccine instability remains a challenge during both development and distribution, particularly for vaccines using live, attenuated virus [34], [35]. Though lyophilization is a primary method for improving vaccine stability, freeze-drying live vaccines generally remains complex, but affords greater long-term stability and facilitates a longer product shelf life [35].

Fortunately, lyophilization of live, replicating poxvirus vaccines was achieved over a century ago and then improved in the 1900s. The resulting vaccines (e.g., Dryvax, Lancy-Vaxina) were used in the successful eradication of smallpox, and the World Health Assembly declared the world free of smallpox in 1980. These live vaccines were then replaced by cell-cultured poxvirus vaccines (ACAM2000, CCSV), which still contained replicating virus. The cell-cultured vaccines were found to have similar safety concerns [36], [37], including, as previously noted, the occurrence of acute myocarditis and pericarditis, as well as the potential for local replication and onward transmission. MVA-BN was developed as a safer, nonreplicating vaccine in a liquid-frozen formulation administered by subcutaneous injection, rather than by skin scarification with a bifurcated needle. In 2008, the US Strategic National Stockpile added MVA-BN to its reserves of essential medical supplies to strengthen national security and protect US interests in the event of a smallpox outbreak.

Early development of MVA-BN also included a freeze-dried formulation. For the post-eradication world, lyophilized poxvirus vaccines provide potential advantages for long-term storage of stockpiled doses and for their distribution in the event of an emergency. Given this and the safety profile that was observed with liquid-frozen MVA-BN, the freeze-dried formulation was recently targeted for further development and testing. The shelf life of the current FD MVA-BN vaccine is not yet known, nor is the extent of the need for cold chain management, as stability assessments are ongoing. Shelf life of stockpiled vaccine likely is optimized by storage at −20 °C. However, the titer of the freeze-dried formulation has remained above the minimum specification level at 2 °C to 8 °C for 5 years, certainly supporting the possibility to ship and/or store the vaccine under refrigerated conditions before use in the event of an emergency.

While enhancing long-term storage and easing cold-chain requirements of vaccine stockpiles is of great value to public health initiatives [34], [38], demonstrating the consistency and robustness of the production process is an important step towards the future licensing of this FD MVA-BN formulation. This phase 3 trial investigating lot-to-lot consistency of the vaccine with regard to immunogenicity provided such evidence. For neutralizing antibody responses, there was no statistical difference in the titers induced by 3 consecutively produced lots of FD MVA-BN 2 weeks after the last vaccination, and seroconversion was nearly complete across groups, ranging between 99.1 % and 99.7 %.

Comparison of the two MVA-BN formulations was undertaken in 2 previous trials, which demonstrated that the humoral response to FD MVA-BN is noninferior to the LF formulation of the vaccine [28], [29]. The immunogenicity findings in this trial not only demonstrate consistency among the lots used for this trial, but also consistency with the growing body of evidence for the humoral response induced by MVA–BN, regardless of formulation. Previous studies have repeatedly shown that MVA-BN induces peak humoral responses 2 weeks following the second vaccination [24], [26], [31], [32], [33]. If one compares the peak responses across trials, including this trial, total antibody titers were reliably in the 3 log10 range, at which protection against infection is provided. There was some variability in the neutralizing antibody titers across different trials, but this variability is largely accounted for by modifications to the PRNT methods used in different trials. Therefore, while this trial demonstrates that high antibody titers are consistently generated across multiple production lots of FD MVA-BN, it also adds to the evidence that lyophilization does not appear to compromise the immunogenicity of the vaccine.

The favorable safety profile of MVA-BN is further supported by the findings of this trial, with no vaccine-related serious adverse events. Importantly, no cardiac inflammatory disorders were reported in any participants vaccinated with FD MVA-BN, in marked contrast to what has been observed with replicating smallpox vaccines [16], [17], [18]. As with other MVA-BN trials, the most commonly reported adverse events after administration of FD MVA-BN were solicited local and general reactions that were mostly mild to moderate in nature and self-limiting. These events also were evenly distributed across the 3 lot groups with regard to frequency, intensity, and duration. Similarly, unsolicited adverse events were evenly distributed across lot groups, with no apparent clusters of events affecting specific body systems. Therefore, these results demonstrate consistency across production lots in terms of reactogenicity as well as immunogenicity.

5. Conclusions

The results of this clinical trial show consistent immunogenicity for FD MVA-BN, with statistically equivalent neutralizing antibody titers 2 weeks after the second vaccination across multiple lot groups. Both neutralizing and total antibody responses were robust and similar to those observed in previous clinical trials. Safety and reactogenicity of FD MVA-BN were also comparable across lot groups and consistent with the known safety profile of MVA-BN. The summary of this evidence supports the appropriateness of FD MVA-BN as an alternative to liquid-frozen vaccine and demonstrates the reliability of the manufacturing process. Further information on long-term stability could confirm its advantages for stockpiling and emergency distribution.

Disclosures.

Edgar Turner Overton: None.

Darja Schmidt, Sanja Vidojkovic, Erika Menius, Katrin Nopora, Jane Maclennan, Heinz Weidenthaler: Employees of Bavarian Nordic.

Declarations.

The trial protocol was reviewed and approved by the relevant IRBs/ECs prior to its start and throughout its conduct, and subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation in the trial. The trial was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was performed in compliance with Good Clinical Practices.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank clinical operations and analysis colleagues for their support during the conduct of the trial, including: Eva Kreitmeir, Tracie Pickler, DeShara Eley-Abdullah, Cindy Handelsman, Teresa Perschy, Andrea Bentz, Rainer Richter, Monika Flür, Nicole Baedeker (all of Bavarian Nordic), Erin Reagoso and Cindy Dukes (of ICON clinical research organization), all of the clinical trial site investigators and personnel; the members of the data safety monitoring board: Frank V. Sonnenburg, Harish Doppalapudi and Herwig Kollaritsch; and also Jacqueline Powell, Barbara Martin, Thomas Meyer and Liddy Chen (of Bavarian Nordic) for medical writing assistance.

Funding.

The study was funded through a contract with the US Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (HHSO100201700019C).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.10.056.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Breman J.G., Arita I. The confirmation and maintenance of smallpox eradication. N England J Med. 1980;303(22):1263–1273. doi: 10.1056/nejm198011273032204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fenner F. Smallpox: emergence, global spread, and eradication. Hist Philos Life Sci. 1993;15(3):397–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayr A. Smallpox vaccination and bioterrorism with pox viruses. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;26(5–6):423–430. doi: 10.1016/S0147-9571(03)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Artenstein A.W., Grabenstein J.D. Smallpox vaccines for biodefense: need and feasibility. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7(8):1225–1237. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.8.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen B.W., Harms T.J., Reynolds M.G., Harrison L.H. Use of Vaccinia Virus Smallpox Vaccine in Laboratory and Health Care Personnel at Risk for Occupational Exposure to Orthopoxviruses - Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:257–262. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6510a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Defense. Update to clinical policy for the Department of Definse Smallpox Vaccination Program (memorandum), https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Policies/2008/04/01/Update-to-Clinical-Policy-for-the-Department-of-Defense-Smallpox-Vaccination-Program [accessed 19 Oct 2021].

- 7.McCollum A.M., Damon I.K. Human monkeypox. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(2):260–267. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durski K.N., McCollum A.M., Nakazawa Y., Petersen B.W., Reynolds M.G., Briand S., et al. Emergence of Monkeypox - West and Central Africa, 1970–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(10):306–310. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6710a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed K.D., Melski J.W., Graham M.B., Regnery R.L., Sotir M.J., Wegner M.V., et al. The detection of monkeypox in humans in the Western Hemisphere. N England J Med. 2004;350(4):342–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen E., Abubakar I., Ihekweazu C., Heymann D., Ntoumi F., Blumberg L., et al. Monkeypox - Enhancing public health preparedness for an emerging lethal human zoonotic epidemic threat in the wake of the smallpox post-eradication era. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;78:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—a potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Petersen B.W., Kabamba J., McCollum A.M., Lushima R.S., Wemakoy E.O., Muyembe Tamfum J.-J., et al. Vaccinating against monkeypox in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Antiviral Res. 2019;162:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaughan A., Aarons E., Astbury J., Balasegaram S., Beadsworth M., Beck C.R., et al. Two cases of monkeypox imported to the United Kingdom, September 2018. Euro Surveill. 2018;23(38) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.38.1800509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erez N., Achdout H., Milrot E., Schwartz Y., Wiener-Well Y., Paran N., et al. Diagnosis of Imported Monkeypox, Israel, 2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(5):980–983. doi: 10.3201/eid2505.190076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaughan A., Aarons E., Astbury J., Brooks T., Chand M., Flegg P., et al. Human-to-Human Transmission of Monkeypox Virus, United Kingdom, October 2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(4):782–785. doi: 10.3201/eid2604.191164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassimatis D.C., Atwood J.E., Engler R.M., Linz P.E., Grabenstein J.D., Vernalis M.N. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1503–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engler RJ, Nelson MR, Collins LC, Jr., et al. A prospective study of the incidence of myocarditis/pericarditis and new onset cardiac symptoms following smallpox and influenza vaccination. PloS one 2015;10(3):e0118283. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Su J.R., McNeil M.M., Welsh K.J., Marquez P.L., Ng C., Yan M., et al. Myopericarditis after vaccination, Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 1990–2018. Vaccine. 2021;39(5):839–845. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eckart R.E., Love S.S., Atwood J.E., et al. Incidence and follow-up of inflammatory cardiac complications after smallpox vaccination. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(1):201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin A.H., Phan H.-A., Barthel R.V., Maisel A.S., Crum-Cianflone N.F., Maves R.C., et al. Myopericarditis and pericarditis in the deployed military member: a retrospective series. Mil Med. 2013;178(1):18–20. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-12-00226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bavarian Nordic. JYNNEOS Prescribing Information. 1 ed, 2019.

- 22.Volkmann A., Williamson A.L., Weidenthaler H., et al. The Brighton Collaboration standardized template for collection of key information for risk/benefit assessment of a Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vaccine platform. Vaccine. 2020;39(22):3067–3080. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenberg R.N., Hurley M.Y., Dinh D.V., et al. A Multicenter, Open-Label, Controlled Phase II Study to Evaluate Safety and Immunogenicity of MVA Smallpox Vaccine (IMVAMUNE) in 18–40 Year Old Subjects with Diagnosed Atopic Dermatitis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0138348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Sonnenburg F., Perona P., Darsow U., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of modified vaccinia Ankara as a smallpox vaccine in people with atopic dermatitis. Vaccine. 2014;32(43):5696–5702. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenberg R.N., Overton E.T., Haas D.W., et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and surrogate markers of clinical efficacy for modified vaccinia Ankara as a smallpox vaccine in HIV-infected subjects. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(5):749–758. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Overton E.T., Stapleton J., Frank I., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic smallpox vaccine in vaccinia-naive and experienced human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals: an open-label, controlled clinical phase II trial. Open Forum. Infect Dis. 2015;2(2):ofv040 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Overton E.T., Lawrence S.J., Stapleton J.T., et al. A randomized phase II trial to compare safety and immunogenicity of the MVA-BN smallpox vaccine at various doses in adults with a history of AIDS. Vaccine. 2020;38(11):2600–2607. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NCT01668537. A phase II trial to compare a liquid-frozen and a freeze-dried formulation of IMVAMUNE (MVA-BN) smallpox vaccine in vaccinia-naïve healthy subjects, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01668537?term=POX-MVA&cond=Smallpox+%28Variola%29&draw=2&rank=6&view=results [accessed 01 Nov 2021].

- 29.Frey S.E., Wald A., Edupuganti S., et al. Comparison of lyophilized versus liquid modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) formulations and subcutaneous versus intradermal routes of administration in healthy vaccinia-naïve subjects. Vaccine. 2015;33(39):5225–5234. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suter M., Meisinger-Henschel C., Tzatzaris M., et al. Modified vaccinia Ankara strains with identical coding sequences actually represent complex mixtures of viruses that determine the biological properties of each strain. Vaccine. 2009;27(52):7442–7450. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frey S.E., Winokur P.L., Hill H., Goll J.B., Chaplin P., Belshe R.B. Phase II randomized, double-blinded comparison of a single high dose (5×10(8) TCID50) of modified vaccinia Ankara compared to a standard dose (1×10(8) TCID50) in healthy vaccinia-naïve individuals. Vaccine. 2014;32(23):2732–2739. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Krempelhuber A., Vollmar J., Pokorny R., et al. A randomized, double-blind, dose-finding Phase II study to evaluate immunogenicity and safety of the third generation smallpox vaccine candidate IMVAMUNE. Vaccine. 2010;28(5):1209–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vollmar J., Arndtz N., Eckl K.M., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of IMVAMUNE, a promising candidate as a third generation smallpox vaccine. Vaccine. 2006;24(12):2065–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumru O.S., Joshi S.B., Smith D.E., Middaugh C.R., Prusik T., Volkin D.B. Vaccine instability in the cold chain: mechanisms, analysis and formulation strategies. Biologicals : journal of the International Association of Biological Standardization. 2014;42(5):237–259. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen L.J.J., Daoussi R., Vervaet C., Remon J.P., De Beer T.R.M. Freeze-drying of live virus vaccines: A review. Vaccine. 2015;33(42):5507–5519. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanchez-Sampedro L., Perdiguero B., Mejias-Perez E., Garcia-Arriaza J., Di Pilato M., Esteban M. The evolution of poxvirus vaccines. Viruses. 2015;7(4):1726–1803. doi: 10.3390/v7041726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tack D.M., Karem K.L., Montgomery J.R., et al. Unintentional transfer of vaccinia virus associated with smallpox vaccines: ACAM2000((R)) compared with Dryvax((R)) Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(7):1489–1496. doi: 10.4161/hv.24319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lloyd J., Cheyne J. The origins of the vaccine cold chain and a glimpse of the future. Vaccine. 2017;35(17):2115–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.