Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the association between pre-intubation respiratory support and outcomes in patients with acute respiratory failure, and to determine the impact of immunocompromised diagnoses on outcomes after adjustment for illness severity.

DESIGN

Retrospective multicenter cohort study.

SETTING

Eighty-two centers in the Virtual Pediatric Systems database.

PATIENTS

Children 1 month through 17 years old intubated in the PICU who received invasive mechanical ventilation for ≥24 hours.

INTERVENTIONS

None.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) and/or non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) was used prior to intubation in 1,825 (34%) of 5,348 PICU intubations across 82 centers. When stratified by immunocompromised (IC) status, 50% of patients had no IC diagnosis, while 41% were IC without prior hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) and 9% had prior HCT. Compared to patients intubated without prior support, pre-intubation exposure to HFNC (aOR 1.33, 95%CI 1.10–1.62) or NIPPV (aOR 1.44, 95%CI 1.20–1.74) was associated with increased odds of PICU mortality. Within subgroups of IC status, pre-intubation respiratory support was associated with increased odds of PICU mortality in IC patients (HFNC: aOR 1.50, 95%CI 1.11–2.03; NIPPV: aOR 1.76, 95%CI 1.31–2.35) and HCT patients (HFNC: aOR 1.75, 95%CI 1.07–2.86; NIPPV: aOR 1.85, 95%CI 1.12–3.02) compared to IC/HCT patients intubated without prior respiratory support. Pre-intubation exposure to HFNC/NIPPV was not associated with mortality in patients without an IC diagnosis. Duration of HFNC/NIPPV >6hr was associated with increased mortality in IC HCT patients (HFNC: aOR 2.41, 95%CI 1.05–5.55; NIPPV: aOR 2.53, 95%CI 1.04–6.15) patients compared HCT patients with <6hr HFNC/NIPPV exposure. After adjustment for patient and center characteristics, both pre-intubation HFNC/NIPPV use (median 15%, range 0–63%) and PICU mortality varied by center.

CONCLUSIONS

In immunocompromised pediatric patients, pre-intubation exposure to HFNC and/or NIPPV is associated with an increased odds of PICU mortality, independent of illness severity. Longer duration of exposure to HFNC/NIPPV prior to IMV is associated with increased mortality in HCT patients.

Keywords: Acute respiratory failure, high-flow nasal cannula, noninvasive ventilation, immunocompromised status, hematopoietic cell transplantation, pediatric critical care

INTRODUCTION

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) and non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) are commonly employed in the initial management of children with acute respiratory failure to provide a higher level of respiratory support without the adverse effects of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) (1–3). HFNC and NIPPV improve gas exchange and decrease work of breathing in respiratory failure, allowing many children to recover without IMV (4–7). However, recent data suggest that the 25–30% of children who fail HFNC/NIPPV may be at higher risk of worse outcomes than patients who receive IMV as the initial therapy (8–10), and that this risk may be influenced by patient factors (11–13).

The management of acute respiratory failure in children with immunocompromised (IC) status and history of hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) may warrant special consideration. We have previously identified an increased risk of sepsis-related mortality associated with IC and HCT status (14). In that report, IC and HCT patients had higher rates of respiratory failure and were more likely to be hospitalized prior to their acute deterioration than patients without IC diagnoses (14). A recent analysis of pediatric HCT patients with respiratory failure identified an alarming rate of cardiac arrest at the time of tracheal intubation for patients with pre-intubation exposure to NIPPV (12). Longer PICU length of stay prior to intubation has been associated with increased mortality in HCT patients (15), while earlier NIPPV has been associated with increased mortality in IC patients (16). In the absence of clinical trial data to support the use of HFNC/NIPPV in IC and HCT patients with acute respiratory failure, observational data to guide clinical decision making regarding the timing and mode of noninvasive support are essential to help intensivists manage these high-risk patients.

We have previously used diagnosis and procedural codes from the multicenter Virtual Pediatric Systems (VPS, LLC) database to accurately phenotype IC diagnoses and history of HCT in patients with sepsis (14). In the present study, we identify a large, multicenter cohort of patients who underwent tracheal intubation, assess the prevalence of IC diagnoses among these patients, determine the association between pre-intubation respiratory support and PICU mortality, and identify center-level variation of patient outcomes after adjustment for demographics and illness severity. We hypothesized that pre-intubation respiratory support would be associated with increased PICU mortality in a time-dependent manner for all patients included in the analysis, that PICU mortality would vary by IC status, and that patient outcomes would vary by center.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study using the multicenter VPS database after review by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia IRB (#20–018107). All patient records in the VPS database during the study period (1/1/2014 to 12/31/2019) were queried for a procedure code for endotracheal intubation, a required data field for all participating VPS sites. For patients with multiple intubations, only the first intubation after PICU admission was included for analysis. Patients aged <1 month or ≥18 years at PICU admission were excluded, as well as patients with tracheostomy and those with home non-invasive or invasive ventilatory support. We excluded patients who were intubated outside of the PICU, as well as patients who received IMV for <24 hours. Patients from low-volume centers which reported ≤10 intubations during the study period were also excluded.

Exposure and Outcomes

All available data were extracted from the VPS database, including demographic information, source of admission, coded diagnoses and procedures, Paediatric Index of Mortality (PIM)-2 (17) severity of illness data, length of stay, and clinical outcome. The primary outcome was all-cause PICU mortality, which is reported by all participating centers. The primary exposure was use of HFNC and/or NIPPV prior to endotracheal intubation; for patients with sequential exposures to both modes of support, the final mode of support prior to intubation was defined as the exposure. We defined these exposures based on procedure codes for HFNC, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), and bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP); these procedures are required variables and indicate the timing and duration of exposure. Immunocompromised status was defined by ICD-9-CM code (eTable 1) (14) and classified as a trichotomous exposure in our analysis (no IC diagnosis vs IC without HCT vs HCT). Identified IC diagnoses included malignancy, solid organ transplant, congenital immunodeficiency, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and aplastic anemia.

Statistical Analyses

Differences in baseline patient characteristics, IC diagnoses, and exposure to HFNC and NIPPV were analyzed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. To measure the association of mortality with pre-intubation exposure to HFNC/NIPPV and evaluate variation in PICU mortality across centers, we constructed mixed-effect (ME) logistic regression models using a series of a priori defined patient factors and center factors known to be associated with mortality. We additionally tested for variance in rates of asthma and sepsis across IC diagnoses. Because rates of sepsis varied by IC status, we completed a post-hoc sensitivity analysis incorporating sepsis diagnosis into the model. Exposure to HFNC or NIPPV was modeled as a single categorical variable. Immunocompromised diagnoses were also modeled as a single categorical variable; HCT was modeled as an effect modifier based on our prior study of sepsis-related mortality in HCT patients (14). The base ME model included no fixed effects and only a center-level random effect; the estimated variance of the random effect reflected the magnitude of the mortality variation across hospitals. In this model, a significant test of variance >0 suggests that the center-level variation is statistically significant. We subsequently added HFNC/NIV exposure, IC diagnoses, and a priori patient factors previously associated with PICU mortality – age, sex, PIM-2 score – to this model as fixed effects to assess if the variance of the center-level random effect remained significant. Finally, we added a center-level variable defining the mean monthly volume of intubations (independent of IC status) to the model as a fixed effect to assess the contribution of center volume to center-level variance in PICU mortality.

We also conducted a secondary analysis to assess PICU mortality based on duration of pre-intubation exposure to HFNC and NIPPV. In this analysis, we first determined the PICU mortality by quintiles of HFNC/NIPPV duration and assessed the ordinal trend in mortality within each IC subgroup using the Cuzick test of trend. Noting a time-dependent effect on mortality, we then dichotomized patients based on a 6-hour duration of HFNC/NIPPV exposure, with the rationale that a 6-hour observation time represented a clinically meaningful trial of pre-intubation respiratory support. A similar 6-hour observation time period has also been used to assess response to pediatric ARDS therapies in the PARDIE study (18). We then constructed two separate mixed effects models restricted to only patients with HFNC and NIPPV exposures respectively, adjusted for the same fixed and random effects as the primary model. Analyses were performed using Stata/IC 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) with statistical significance defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Patients who require Tracheal Intubation

During the study period, we identified 5,348 patients who met inclusion criteria across 82 centers (see eFigure 1 for details of the study population). Of patients requiring IMV, 34% (1,825/5,348) were exposed to HFNC/NIPPV prior to intubation. Immunocompromised and/or HCT diagnoses were identified in 49% of patients (2,638/5,348) and 59% of nonsurvivors (682/1,148). Demographics, patient characteristics, and clinical outcomes are shown in Table 1, stratified by IC diagnoses. As expected, age, PIM-2 score, source of admission, sepsis prevalence, limitations of technological support, and rate of pre-intubation respiratory support all varied by IC status (all p<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients who required tracheal intubation, by immunocompromised status

| Variable | No IC diagnosis (n=2,710) |

IC, not HCT (n=2,179) |

HCT (n=459) |

p a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Distribution, n (%) | ||||

| 1 month to 23 months | 1,588 (59) | 529 (24) | 142 (31) | <0.001 |

| 2 years to 5 years | 414 (15) | 559 (26) | 98 (21) | |

| 6 years to 12 years | 335 (12) | 574 (26) | 104 (23) | |

| 13 years to 18 years | 373 (14) | 517 (24) | 115 (25) | |

| Male sex, n (%) | 1,474 (54) | 1,174 (54) | 249 (54) | 0.51 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 36 (1) | 24 (1) | 1 (<1) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 96 (4) | 120 (5) | 11 (2) | |

| Black or African American | 484 (18) | 274 (13) | 54 (12) | |

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 12 (<1) | 3 (<1) | 0 (0) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 353 (13) | 342 (16) | 49 (11) | |

| White | 1,226 (45) | 976 (45) | 157 (34) | |

| Other/Unspecified | 503 (19) | 440 (20) | 187 (41) | |

| PIM-2 POD, median [IQR] | 1.42 [0.85–4.84] | 2.91 [0.91–4.97] | 4.13 [1.05–5.68] | <0.001 |

| Admission source, n (%) | ||||

| Emergency department | 1,193 (44) | 556 (26) | 39 (9) | <0.001 |

| Hospital ward | 1,062 (39) | 1,306 (60) | 392 (85) | |

| Operating room | 244 (9) | 180 (8) | 16 (3) | |

| Other | 211 (8) | 137 (6) | 12 (3) | |

| Severe sepsis/septic shock, n (%) | 387 (14) | 456 (21) | 173 (38) | <0.001 |

| Asthma diagnosis, n (%) | 208 (8) | 138 (6) | 38 (8) | 0.12 |

| Limitations of care, n (%)b | 230/2,305 (10) | 249/1,933 (13) | 95/402 (24) | <0.001 |

| Pre-intubation support, n (%) | ||||

| None | 1,731 (64) | 1,547 (70) | 245 (53) | <0.001 |

| HFNC | 444 (16) | 315 (15) | 114 (25) | |

| NIPPV | 535 (20) | 317 (15) | 100 (22) |

Kruskal-Wallis H test for continuous variables, χ2 test for categorical variables, α = 0.05.

Limitations of care data was unavailable for 16% of study participants (No IC diagnosis: 19%; IC, not HCT: 14%; HCT: 13%).

IC: Immunocompromised; HCT: hematopoietic cell transplant; PIM-2: Paediatric Index of Mortality-2; IQR: Interquartile Range; HFNC: high-flow nasal cannula; NIPPV: noninvasive positive pressure ventilation.

Association Between Mode of Respiratory Support and PICU Mortality

For our primary analysis, we measured the association between pre-intubation mode of respiratory support with PICU mortality using a mixed effects logistic regression model. We built the model starting with a center-level random effect and added the following fixed effects: age, sex, PIM-2 score, and center-level volume of intubations per month. In this preliminary model, pre-intubation exposure to HFNC (aOR 1.33, 95% CI 1.10–1.62) and NIPPV (aOR 1.44, 95% CI 1.20–1.74) were associated with an increased odds of PICU mortality compared to patients intubated without prior respiratory support. We then added history of IC diagnoses and history of HCT to the model; results of this final ME model are shown in Table 2. Among IC patients without a history of HCT, pre-intubation exposure to HFNC (aOR 1.50, 95% CI 1.11–2.03) and NIPPV (aOR 1.76, 95% CI 1.31–2.35) conferred an increased odds of PICU mortality compared to IC patients without pre-intubation respiratory support. Among HCT patients, pre-intubation HFNC (aOR 1.75, 95% CI 1.07–2.86) and NIPPV (aOR 1.85, 95% CI 1.12–3.02) exposure was associated with an increased odds of mortality compared to HCT patients without pre-intubation respiratory support. Because rates of sepsis varied by cohort, we conducted a post-hoc sensitivity analysis incorporating sepsis diagnosis into the model which revealed similar findings to the above analysis; results are shown in eFigure 2.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds of PICU mortality, stratified based on pre-intubation exposure to respiratory support

| Pre-Intubation Respiratory Support | No IC Diagnosis aOR [95% CI]a |

IC, not HCT aOR [95% CI]a |

HCT aOR [95% CI]a |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) |

| HFNC | 0.95 [0.70 – 1.29] | 1.50 [1.11 – 2.03] | 1.75 [1.07 – 2.86] |

| NIPPV | 1.03 [0.78 – 1.36] | 1.76 [1.31 – 2.35] | 1.85 [1.12 – 3.02] |

Mixed effects model, adjusted for patient-level fixed effects (IC diagnosis, age, gender, PIM-2 score) and center-level fixed effects (mean monthly volume of tracheal intubations). For each category of IC status, patients intubated without pre-intubation exposure to HFNC/NIPPV serve as the reference group.

IC: Immunocompromised; HCT: hematopoietic cell transplant; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; HFNC: high-flow nasal cannula; NIPPV: noninvasive positive pressure ventilation.

Association Between Duration of Respiratory Support and PICU Mortality

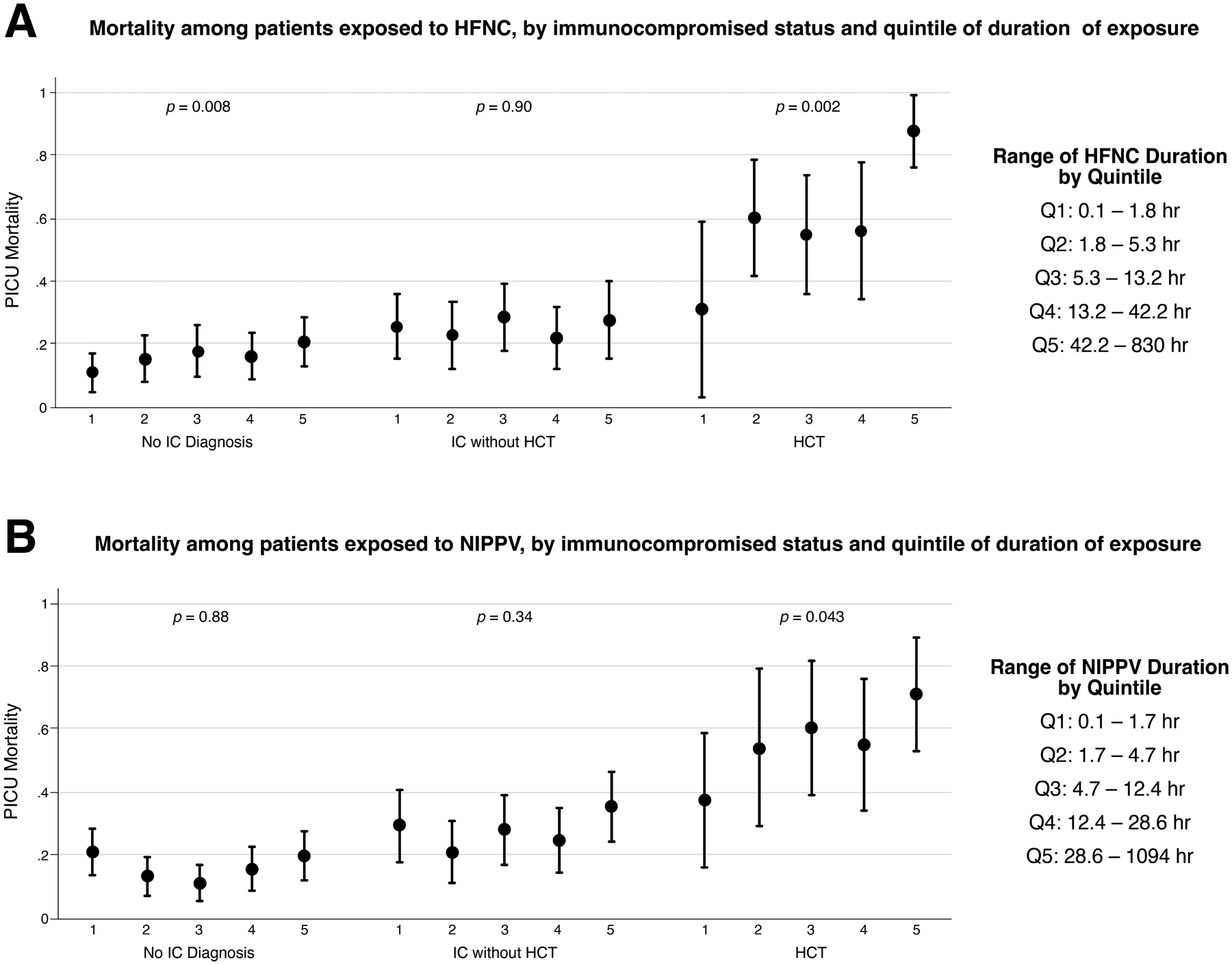

Our analysis of pre-intubation respiratory support as a time-dependent exposure included primary stratification into quintiles of duration of HFNC and NIPPV exposure, as shown in Figure 1. In this analysis, the relationship between exposure duration and outcome varied by IC diagnosis. Among HCT patients, mortality increased across quintiles of duration of exposure to HFNC (p=0.002) and NIPPV (p=0.043). This time-dependent effect was not seen in IC patients without HCT, or in patients without IC diagnosis. We also noted a bimodal distribution of mortality associated with duration of NIPPV exposure in patients without HCT.

Figure 1.

PICU mortality by quintiles of HFNC (Panel A) and NIPPV (Panel B) duration, stratified by IC diagnoses. For each quintile, the center circle represents the quintile mortality rate, and the bars represent the 95% confidence interval around this mortality rate. The Cuzick test of trend was used to assess the ordinal trend in mortality within each IC subgroup.

We further dichotomized patients based on a 6-hour duration of HFNC/NIPPV exposure and tested the association between duration HFNC and NIPPV exposures and PICU mortality, adjusted for the same fixed and random effects as the primary model. As shown in Table 3, HCT patients had an increased odds of mortality associated with >6hr duration of pre-intubation HFNC (aOR 2.41, 95% CI 1.05–5.55) and NIPPV (aOR 2.53, 95% CI 1.04–6.15) exposure compared to HCT patients with duration of exposure ≤6hr. Longer duration of HFNC/NIPPV exposure was not associated with increased mortality in IC patients without HCT, or in patients without an IC diagnosis.

Table 3.

Adjusted odds of PICU mortality, based on duration of pre-intubation respiratory support

| Pre-Intubation HFNC Exposure | Pre-Intubation NIPPV Exposure | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| aOR [95% CI]a | aOR [95% CI]b | ||

| No IC Dx | No IC Dx | ||

| HFNC ≤6hr (n=194) | (reference) | NIPPV ≤6hr (n=262) | (reference) |

| HFNC >6hr (n=250) | 1.44 [0.83– 2.53] | NIPPV >6hr (n=273) | 0.91 [0.56– 1.48] |

| IC, not HCT | IC, not HCT | ||

| HFNC ≤6hr (n=134) | (reference) | NIPPV ≤6hr (n=135) | (reference) |

| HFNC >6hr (n=181) | 0.83 [0.49 – 1.43] | NIPPV >6hr (n=182) | 1.19 [0.70 – 2.04] |

| HCT | HCT | ||

| HFNC ≤6hr (n=44) | (reference) | NIPPV ≤6hr (n=36) | (reference) |

| HFNC >6hr (n=70) | 2.41 [1.05 – 5.55] | NIPPV >6hr (n=64) | 2.53 [1.04 – 6.15] |

Mixed effects model, adjusted for patient-level fixed effects (IC diagnosis, age, gender, PIM-2 score) and center-level fixed effects (mean monthly volume of tracheal intubations), restricted to patients who received HFNC prior to tracheal intubation. For each category of IC status, patients intubated without pre-intubation exposure to HFNC serve as the reference group.

Mixed effects model, adjusted for patient-level fixed effects (IC diagnosis, age, gender, PIM-2 score) and center-level fixed effects (mean monthly volume of tracheal intubations), restricted to patients who received NIPPV prior to tracheal intubation. For each category of IC status, patients intubated without pre-intubation exposure to NIPPV serve as the reference group.

IC: Immunocompromised; HCT: hematopoietic cell transplant; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; HFNC: high-flow nasal cannula; NIPPV: noninvasive positive pressure ventilation.

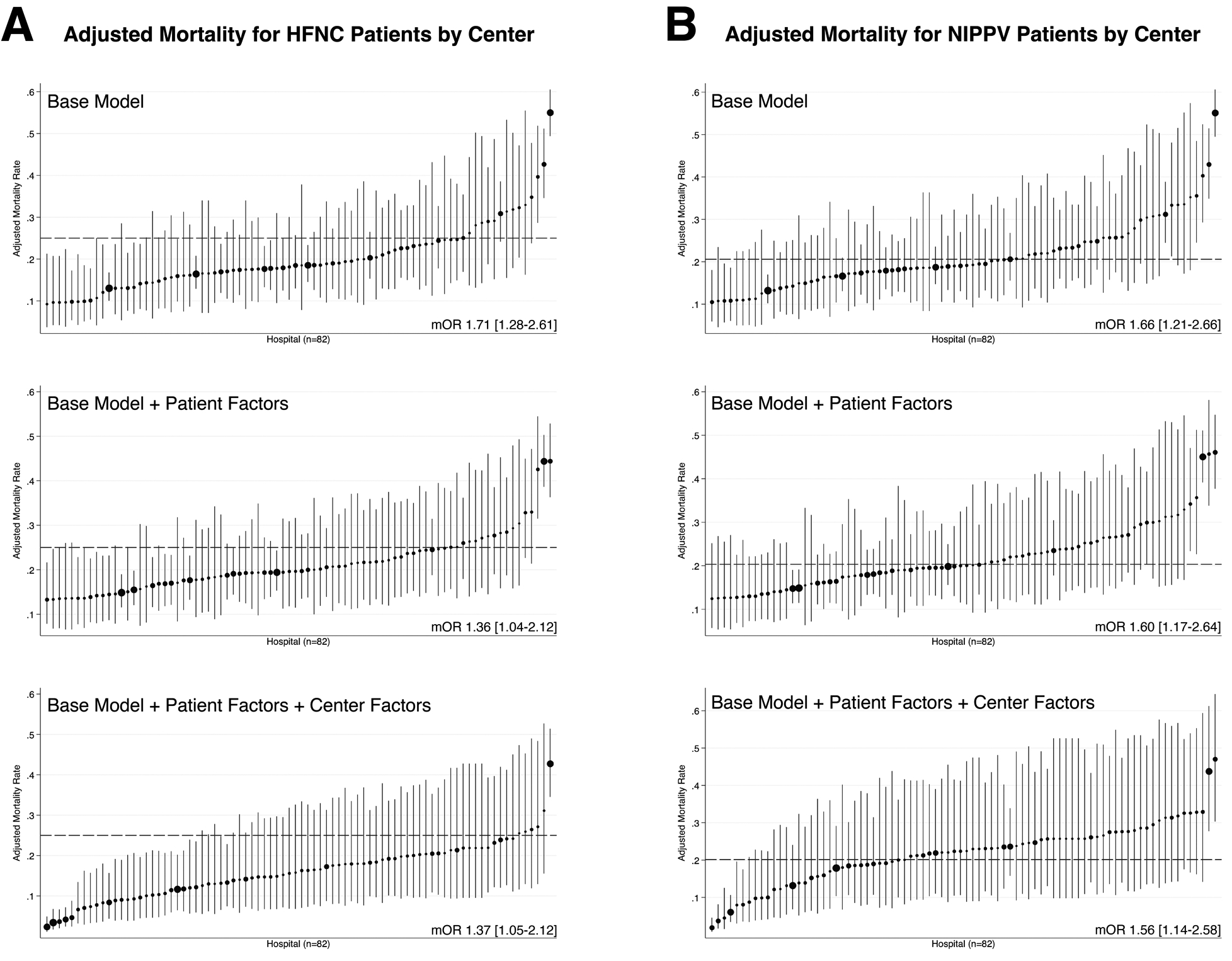

Center-Level Variance in PICU Mortality

Pre-intubation HFNC/NIPPV use and PICU mortality varied significantly across the 82 centers in this study. Pre-intubation HFNC use by center varied from 0–55% (median 14%), and pre-intubation NIPPV use by center varied from 0–63% (median 15%). To evaluate center-level variance in PICU mortality, we constructed two independent ME models – for pre-intubation HFNC and NIPPV exposure – and utilized stepwise addition of patient- and center-level fixed effects to our model. Center-level variance was significant in the base ME models. The addition of pre-intubation respiratory support, IC diagnoses, and patient factors (age, sex, and PIM-2 score) to the model decreased center-level variance in PICU mortality, but this variance remained significant in both models (p<0.001). The subsequent addition of duration of pre-intubation respiratory support and mean monthly volume of intubations further decreased this variance, which remained statistically significant in both models (p<0.001).

Figure 2 displays the adjusted PICU mortality rate by center for patients with pre-intubation exposure to HFNC and NIPPV, with stepwise adjustment for patient-level and center-level fixed effects. The median odds ratio, which quantifies the heterogeneity of outcomes between centers (19), is displayed for each successive model. For both modes of pre-intubation respiratory support, addition of patient-level and center-level factors to the model reduces, but does not eliminate, the heterogeneity of outcomes, suggesting that unmeasured institutional characteristics also contribute to center-level variance in PICU mortality.

Figure 2.

Center-level variation in adjusted PICU mortality for patients with pre-intubation exposure to HFNC (Panel A) or NIPPV (Panel B). For both panels, the graphs show adjusted mortality in the base model (top figure), the base model + patient factors (middle figure), and the base model + patient factors + center volume (bottom figure). The size of the point estimate corresponds to the volume of patients from each participating hospital. Error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. The adjusted mortality rate for the entire cohort is indicated by a broken line on each graph, and the median odds ratio is indicated at the lower right corner.

DISCUSSION

This large, multicenter cohort study was designed to evaluate the association between pre-intubation respiratory support and PICU mortality in immunocompromised children. Using a well-defined cohort of patients from the VPS database, we found that pre-intubation exposure to HFNC or NIPPV was associated with an increased odds of PICU mortality, a finding which aligns with a recent report from the RESTORE study (20). When we further stratified this risk by IC diagnoses, we discovered that this association was driven by patients with IC diagnoses or HCT, as an increased odds of mortality was no longer seen in the patients without IC diagnoses after adding these exposures to our models. By assessing pre-intubation respiratory support as a time-dependent exposure, we demonstrated that IMV after a prolonged exposure to HFNC/NIPPV was associated with increased mortality in HCT patients. Finally, we demonstrated substantial variation in PICU mortality across centers in children with pre-intubation exposure to HFNC/NIPPV, even after adjustment for severity of illness, IC status, and center volume.

Our primary analysis yields several novel insights into specific IC phenotypes relevant to clinicians and clinical researchers. First, IC diagnoses are very common among children with respiratory failure who require IMV, present in 49% of the cohort and 59% of PICU mortalities. Second, our results confirm that a history of HCT is a major risk factor for PICU mortality among patients with acute respiratory failure. These findings are congruent with recent reports which have identified high levels of morbidity and mortality associated with respiratory failure and sepsis in pediatric HCT patients (12, 14, 21). The increased risk associated with HCT status is likely multifactorial (22), conferred by prolonged T cell immunosuppression (23), lung injury due to conditioning regimens and peri-transplant alloimmune disease (24), and increased exposure to infectious agents (25). Third, we found that in the absence of IC diagnosis or HCT, exposure to pre-intubation respiratory support is not associated with an increased odds of PICU mortality. Because patient immune status has a major impact on clinical outcomes in this cohort, careful consideration of IC diagnoses will be important in the design of future trials to identify best practices regarding noninvasive management of pediatric respiratory failure. Finally, we have identified a variable association between duration of pre-intubation respiratory support and clinical outcomes based on IC diagnoses. While longer duration of exposure is associated with increased PICU mortality in select populations, it will be important for future, prospective studies to evaluate physiologic criteria which predict success/failure during a time-limited trial of noninvasive support in pediatric respiratory failure.

In our primary analysis, we identified that IC status as an important risk factor for mortality in pediatric respiratory failure. Importantly, we also identified that mode and duration of pre-intubation respiratory support does not convey an increased risk of PICU mortality in patients without an IC diagnosis. While some prior studies have collected limited data regarding IC diagnoses (20, 26), our results indicate that subgroups of IC and HCT patients may be responsible for the increased risk associated with pre-intubation respiratory support. Based on our findings, we recommend that future trials of pediatric acute respiratory failure stratify patients based on IC and HCT status to accurately account for the impact of these conditions on relevant patient outcomes.

We found that PICU mortality varied significantly across the 82 centers in our cohort. While some variance was explained by patient-level factors, including IC diagnoses and illness severity scores, as well as the center-level volume of intubations, significant variance among centers remained after both adjustments. Substantial variability in the use and duration of HFNC/NIPPV in pediatric respiratory failure has been previously reported (27–29). Our results suggest that this variation in care practices may be associated with differences in patient outcomes, although other unmeasured causes of patient- and center-level variance may also influence this finding. These data, combined with similar recent data showing increased mortality associated with pre-intubation NIPPV use in the RESTORE trial (20), suggest a strong rationale for a prospective study of noninvasive respiratory support in pediatric acute respiratory failure.

While retrospective studies of pediatric critical illness have inherent limitations, our study has several notable strengths. We have previously demonstrated that the multicenter VPS dataset can be used to identify an accurate cohort of IC patients (14), and in the present analysis we have leveraged that cohort to yield important new insights into PICU mortality among IC patients with respiratory failure who require intubation and IMV. Unlike administrative datasets, data in VPS is extracted by expert, trained coders according to standard data definitions subject to quarterly inter-rater reliability testing. This dataset also includes required reporting of PICU procedures and robust severity of illness data, which allows for careful selection and adjustment for covariates. Despite these strengths, there are important limitations which must be considered when interpreting these results. IC phenotypes were identified by diagnosis code, and thus no information regarding current disease status, severity of clinical phenotype, stage of malignancy, and concurrent disease-modifying therapies were available for analysis. Due to this data limitation, we were also unable to identify and assess patients who are immunocompromised due to chronic immunosuppressive therapies, and IC phenotypes could not be confirmed with clinical criteria. The timing and indications for HCT, conditioning regimen, transplant type, source of cells, and transplant-related complications are unavailable in VPS. Inclusion of these variables would allow for further in-depth risk stratification of these high-risk patients. Furthermore, data regarding the etiology of respiratory failure are largely unavailable in VPS, thus limiting our ability to assess confounding by indication. Because VPS only reports data starting from PICU admission, we are unable to quantify the duration of HFNC/NIPPV exposure prior to PICU admission. This information bias may have underestimated the duration of pre-intubation support in some patients admitted from an inpatient ward and could also impact clinical outcomes if patients were inadequately supported prior to PICU admission. Code status is only recorded in VPS from PICU admission, which limits our ability to account for dynamic discussions regarding limitations of technological support which often occur in a rapidly deteriorating patient. Finally, because our study question was limited to patients who required endotracheal intubation, we cannot comment on the role of HFNC/NIPPV in patients who successfully recover without the need for IMV.

CONCLUSIONS

In this large, multicenter study of noninvasive respiratory support prior to tracheal intubation, IC diagnoses were present in 49% of patients who required tracheal intubation and 59% of nonsurvivors. After adjustment for measured confounders, exposure to HFNC and NIPPV prior to intubation was associated with an increased odds of mortality in IC and HCT patients, but not among patients without an IC diagnosis. Increased duration of pre-intubation HFNC/NIPPV was also associated with increased PICU mortality in HCT patients. As expected, there was significant variation in PICU mortality among centers.

As our understanding of optimal care practices for pediatric respiratory failure continues to develop, we must pay careful attention to the high-risk cohort of children with IC conditions. We recommend that IC patients should be rapidly reassessed after introduction of HFNC/NIPPV, as patients who require IMV after HFNC/NIPPV appear to have increased mortality. Further research into the appropriate duration and mode of support for IC and HCT patients with respiratory failure is critical to improving survival in this heterogeneous, high-risk cohort of patients. The presence of substantial variation in use of HFNC/NIPPV and PICU outcomes across centers highlights the need for a prospective study of best practices regarding noninvasive support in pediatric acute respiratory failure, with particular attention to patients with prior HCT.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

VPS data was provided by Virtual Pediatric Systems, LLC. No endorsement or editorial restriction of the interpretation of these data or opinions of the authors has been implied or stated. This manuscript has been reviewed by the PALISI Scientific Committee and the VPS Research Committee.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

Financial support was provided by the Endowed Chair, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. Dr. Lindell is also supported by the Thrasher Research Fund. Dr. Fitzgerald is also supported by NIDDK K23DK119463. Dr. Rowan is also supported by NHLBI K23HL150244. Dr. Flori is also supported by NHLBI R01HL149910 and NICHD R21HD097387. Ms. Napolitano is supported by AHRQ R18HS024511 and has research or consulting relationships with Drager, Smiths Medical, Philips/Respironics, Actuated Medical, and VERO-Biotech. Dr. Nishisaki is also supported by AHRQ R18 HS024511. For the remaining authors, no conflicts were declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Munoz-Bonet JI, Flor-Macian EM, Brines J, Rosello-Millet PM, et al. : Predictive factors for the outcome of noninvasive ventilation in pediatric acute respiratory failure. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010; 11(6):675–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fortenberry JD, Del Toro J, Jefferson LS, Evey L, et al. : Management of pediatric acute hypoxemic respiratory insufficiency with bilevel positive pressure (BiPAP) nasal mask ventilation. Chest 1995; 108(4):1059–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baudin F, Gagnon S, Crulli B, Proulx F, et al. : Modalities and Complications Associated With the Use of High-Flow Nasal Cannula: Experience in a Pediatric ICU. Respir Care 2016; 61(10):1305–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris JV, Ramnarayan P, Parslow RC, Fleming SJ: Outcomes for Children Receiving Noninvasive Ventilation as the First-Line Mode of Mechanical Ventilation at Intensive Care Admission: A Propensity Score-Matched Cohort Study. Crit Care Med 2017; 45(6):1045–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teague WG: Noninvasive ventilation in the pediatric intensive care unit for children with acute respiratory failure. Pediatr Pulmonol 2003; 35(6):418–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganu SS, Gautam A, Wilkins B, Egan J: Increase in use of non-invasive ventilation for infants with severe bronchiolitis is associated with decline in intubation rates over a decade. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38(7):1177–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernet V, Hug MI, Frey B: Predictive factors for the success of noninvasive mask ventilation in infants and children with acute respiratory failure. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005; 6(6):660–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yanez LJ, Yunge M, Emilfork M, Lapadula M, et al. : A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of noninvasive ventilation in pediatric acute respiratory failure. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2008; 9(5):484–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Payen V, Jouvet P, Lacroix J, Ducruet T, et al. : Risk factors associated with increased length of mechanical ventilation in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012; 13(2):152–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clayton JA, McKee B, Slain KN, Rotta AT, et al. : Outcomes of Children With Bronchiolitis Treated With High-Flow Nasal Cannula or Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2019; 20(2):128–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emeriaud G, Napolitano N, Polikoff L, Giuliano J Jr., et al. : Impact of Failure of Noninvasive Ventilation on the Safety of Pediatric Tracheal Intubation. Crit Care Med 2020; 48(10):1503–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowan CM, Fitzgerald JC, Agulnik A, Zinter MS, et al. : Risk Factors for Noninvasive Ventilation Failure in Children Post-Hematopoietic Cell Transplant. Front Oncol 2021; 11:653607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayordomo-Colunga J, Medina A, Rey C, Diaz JJ, et al. : Predictive factors of non invasive ventilation failure in critically ill children: a prospective epidemiological study. Intensive Care Med 2009; 35(3):527–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindell RB, Nishisaki A, Weiss SL, Traynor DM, et al. : Risk of Mortality in Immunocompromised Children With Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. Crit Care Med 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowan CM, Gertz SJ, McArthur J, Fitzgerald JC, et al. : Invasive Mechanical Ventilation and Mortality in Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Multicenter Study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016; 17(4):294–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters MJ, Agbeko R, Davis P, Klein N, et al. : Randomized Study of Early Continuous Positive Airways Pressure in Acute Respiratory Failure in Children With Impaired Immunity (SCARF) ISRCTN82853500. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2018; 19(10):939–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slater A, Shann F, Pearson G, Paediatric Index of Mortality Study G: PIM2: a revised version of the Paediatric Index of Mortality. Intensive Care Med 2003; 29(2):278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khemani RG, Smith L, Lopez-Fernandez YM, Kwok J, et al. : Paediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome incidence and epidemiology (PARDIE): an international, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7(2):115–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsen K, Petersen JH, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Endahl L: Interpreting parameters in the logistic regression model with random effects. Biometrics 2000; 56(3):909–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopp W, Gedeit RG, Asaro LA, McLaughlin GE, et al. : The Impact of Preintubation Noninvasive Ventilation on Outcomes in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med 2021; 49(5):816–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindell RB, Gertz SJ, Rowan CM, McArthur J, et al. : High Levels of Morbidity and Mortality Among Pediatric Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients With Severe Sepsis: Insights From the Sepsis PRevalence, OUtcomes, and Therapies International Point Prevalence Study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017; 18(12):1114–1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nieder ML, McDonald GB, Kida A, Hingorani S, et al. : National Cancer Institute-National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute/pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium First International Consensus Conference on late effects after pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation: long-term organ damage and dysfunction. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011; 17(11):1573–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velardi E, Tsai JJ, van den Brink MRM: T cell regeneration after immunological injury. Nat Rev Immunol 2021; 21(5):277–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zinter MS, Lindemans CA, Versluys BA, Mayday MY, et al. : The pulmonary metatranscriptome prior to pediatric HCT identifies post-HCT lung injury. Blood 2021; 137(12):1679–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ardura MI: Overview of Infections Complicating Pediatric Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2018; 32(1):237–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yildizdas D, Yontem A, Iplik G, Horoz OO, et al. : Predicting nasal high-flow therapy failure by pediatric respiratory rate-oxygenation index and pediatric respiratory rate-oxygenation index variation in children. Eur J Pediatr 2021; 180(4):1099–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawaguchi A, Garros D, Joffe A, DeCaen A, et al. : Variation in Practice Related to the Use of High Flow Nasal Cannula in Critically Ill Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2020; 21(5):e228–e235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller AG, Gentle MA, Tyler LM, Napolitano N: High-Flow Nasal Cannula in Pediatric Patients: A Survey of Clinical Practice. Respir Care 2018; 63(7):894–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fanning JJ, Lee KJ, Bragg DS, Gedeit RG: U.S. attitudes and perceived practice for noninvasive ventilation in pediatric acute respiratory failure. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2011; 12(5):e187–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.