Abstract

Pathogenesis in kala-azar is associated with depressed cellular immunity and significant elevation of antileishmanial antibodies. Since these antibodies are present even after cure, analysis of the parasite-specific isotypes and immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclasses in kala-azar patients may shed new light on the immune responses during progression and resolution of infection. Using leishmanial membrane antigenic extracts, we investigated the relative levels of specific IgG, IgM, IgA, IgE, and IgG subclasses in Indian kala-azar patient sera during disease, drug resistance, and cure. Acute-phase sera showed strong stimulation of IgG, followed by IgE and IgM and lastly by IgA antibodies. IgG subclass analysis revealed expression of all of the subclasses, with a predominance of IgG1 during disease. Following sodium stibogluconate (SAG) resistance, the levels of IgG, IgM, IgE, and IgG4 remained constant, while there was a decrease in the titers of IgG2 and IgG3. In contrast, a significant (2.2-fold) increase in IgG1 was observed in these individuals. Cure, in both SAG-responsive and unresponsive patients, correlated with a decline in the levels of IgG, IgM, IgE, and all of the IgG subclasses. The stimulation of IgG1 and the persistence, most importantly, of IgE and IgG4 following drug resistance, along with a decline in IgE, IgG4, and IgG1 with cure, demonstrate the potential of these isotypes as possible markers for monitoring effective treatment in kala-azar.

Human visceral leishmaniasis (VL), or kala-azar, a systemic fatal disease, is caused by Leishmania donovani, an intracellular protozoan parasite that infects and multiplies in the macrophages of the spleen, liver, bone marrow, and lymph nodes. The disease is associated with severe immunosuppression as evidenced by the failure to respond to L. donovani antigens in terms of delayed-type hypersensitivity, lymphoproliferation, and interleukin-2 (IL-2) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production in vitro (13, 15, 37, 40). Enhanced induction of IL-10 and/or IL-4 mRNA in tissues and elevated levels of IL-4, IL-10, and IgE over IFN-γ in serum (20, 26, 28, 46, 48) suggest that a dominant Th2 response suppresses the activity of Th1 during disease. With successful drug therapy, T-cell proliferation and IL-2 and IFN-γ production in response to Leishmania antigen are restored (13, 40). Cured individuals, however, show Leishmania-reactive T cells with Th1- and Th2-type lymphokines coexisting after infection (7, 26, 27). Thus, the heterogeneous set of cytokine responses provoked by kala-azar during disease and resolution of infection reflects a complex Th1-Th2 cell picture that is difficult to delineate for indicators of clinical improvement.

VL is also marked by high levels of Leishmania-specific antibodies (10, 34) which appear soon after infection and before the development of cellular immunologic abnormalities. While the antibody titers in kala-azar have been exploited for specific diagnosis, their role in resolution of disease and protective immunity is largely unknown. It is, however, evident that resistance in a large population of individuals residing in areas of endemicity is detectable only by the development of specific antibodies and/or T-cell response to leishmanial antigens (17, 29, 40). In our attempts to induce protection against L. donovani infection in BALB/c mice, we have demonstrated the involvement of cell-mediated and humoral immune responses in resistance against the disease (2, 4). Analysis of the immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclasses revealed preferential stimulation of IgG1 in infected mice and of IgG2a and IgG2b in protected mice (2, 3). A study of Leishmania membrane antigen (LAg)-specific Ig isotypes in Indian kala-azar patients revealed the elevation of IgG, IgM, IgE, and IgG subclass antibodies, with IgG3 being specifically associated with this disease (5). In this study, we report the LAg-specific Ig isotypes and IgG subclasses in the sera of kala-azar patients during active disease, drug unresponsiveness, and successful cure, to establish a correlation of these isotypes with progression and resolution of infection. These observations may have important implications for vaccine development as well as noninvasive assessment of the success of treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Since resistance to pentavalent antimonials, the mainstay of VL chemotherapy, is on the rise, especially in India (25, 46), the prediction of clinical relapse would be desired.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects.

The subjects of the present investigation were 5- to 70-year-old VL patients (n = 15) living in areas of eastern India, where kala-azar is endemic. The patients (5 females and 10 males) were admitted to the School of Tropical Medicine, Calcutta, India. Diagnosis of the disease and drug unresponsiveness were confirmed parasitologically by the presence of Leishmania amastigotes in spleen and/or bone marrow aspirates. Blood was obtained after diagnosis, before the initiation of chemotherapy, posttreatment, and after cure. Treatment with 20 injections of sodium stibogluconate (SAG), the first-line drug (20 mg/kg of body weight), led to successful cure in 10 patients, whereas five failed to respond to SAG and were retreated with the second-line drug, amphotericin B (seven injections; 1 mg/kg of body weight). Serum samples were taken from each of the 15 patients at least twice: on day 0 (i.e., before initiation of therapy) and 50 days after successful treatment or 45 days after unsuccessful treatment with SAG. Samples from the latter five patients were taken again at 75 days following successful treatment with amphotericin B. A total of 35 different samples obtained were studied in two groups. All patients had given informed consent to participate in this study.

Antigen preparation.

L. donovani AG83, originally isolated from an Indian kala-azar patient, was cultured in vitro for antigen preparation as described earlier (2). Briefly, stationary-phase promastigotes, harvested after the third or fourth passage, were washed four times in ice-cold 0.02 M phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2 (PBS), and suspended at a concentration of 1.0 g of cell pellet (ca. 5 × 1010 stationary-phase promastigotes) in 50 ml of cold 5 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.6. The suspension was vortexed six times for 2 min each on ice with 10-min intervals in between and centrifuged at 2,310 × g for 10 min. The crude ghost membrane pellet thus obtained was resuspended in 10 ml of the same Tris buffer and sonicated three times for 1 min each on ice in an ultrasonicator. The suspension was finally centrifuged at 4,390 × g for 30 min, and the supernatant containing the LAg was harvested and stored in aliquots at −70°C until use. The amount of protein obtained from 1.0 g of cell pellet, as assayed by the method of Lowry et al. (31), was 16 mg.

ELISA for parasite-specific Igs.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of IgG, IgM, IgA, IgE, and IgG subclass antibodies to LAg was carried out on polystyrene round-bottom microtiter plates (Tarsons) as described earlier (5). LAg extracted from L. donovani was applied to the plates at 20 μg/ml in 0.02 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) and incubated at 4°C overnight. After the plates were washed three times with PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween 20, excess reactive sites were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin for 3 h at room temperature, washed as before, and subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with the kala-azar sera serially diluted in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin. After washing, peroxidase-conjugated goat polyclonal antibodies directed against human IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgE (Sigma Immunochemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) were applied at a 1:5,000 dilution in PBS for 3 h at room temperature. After four washes, o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride was applied as an enzyme substrate for 45 min, and the optical density was read at 492 nm in an ELISA reader.

For the determination of human IgG subclass antibodies, the LAg-washed wells incubated with serially diluted kala-azar sera were treated with mouse anti-human IgG subclass-restricted monoclonal antibodies (Sigma Immunochemicals) at a 1:3,000 dilution for 3 h at room temperature. After three washes, peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma Immunochemicals) was applied at a 1:5,000 dilution overnight at 4°C. The color reaction was carried out as described above, and the optical density was read at 492 nm. Titers were determined from the extensive titration of each serum sample as the dilution of serum required to reach half-maximal absorbance (A492 = 1.0).

Western blot analysis.

After sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the LAg was electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose by using a Transblot apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Immunoblot assays were performed by the method of Rolland-Burger et al. (38) with slight modifications. The blot was blocked overnight in 100 mM Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.6) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (T-20) (8), washed once with 0.05% T-20 in Tris-buffered saline (washing buffer), and incubated for 1 h with kala-azar acute-phase, SAG-resistant, or convalescent-phase serum. Acute-phase and SAG-resistant sera were diluted at 1:500, and convalescent-phase sera were diluted at 1:100, in washing buffer. The blots were then washed three times for 20 min each and incubated for 1 h with 1:500-diluted peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Sigma Immunochemicals), followed by three washes as described above. The last wash was done without T-20. Enzymatic activity was revealed with 15 mg of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma Immunochemicals) in 30 μl of TBS containing 15 μl of 30% H2O2.

Statistical analysis.

All data comparisons were analyzed for statistical significance with the two-tailed paired Student t test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Specific antibody responses of antimony-resistant Indian kala-azar patients.

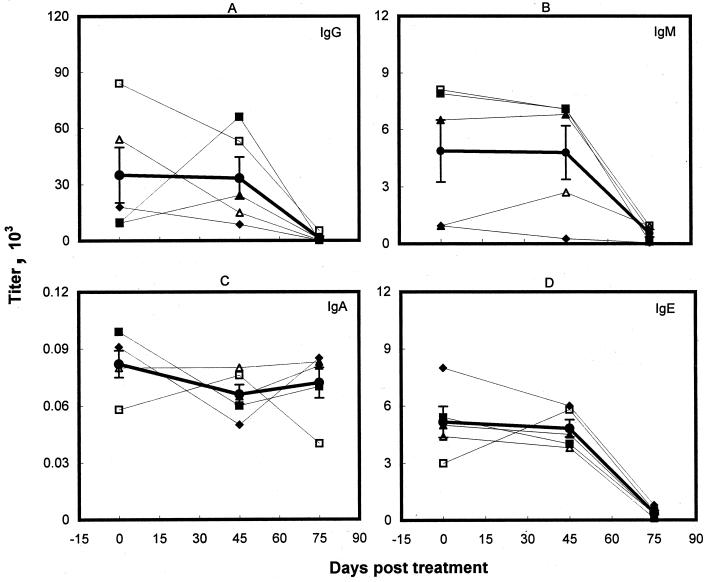

Five symptomatic kala-azar patients who failed to respond to the conventional treatment with pentavalent antimonials were retreated successfully with amphotericin B. The serological profile of the Ig isotypes and IgG subclasses in this group were studied at 0, 45, and 75 days posttreatment. Major laboratory findings of this longitudinal study are shown in Fig. 1 and 2 and Table 1. High titers of anti-LAg IgG antibodies before the initiation of therapy were reduced insignificantly (Fig. 1A; Table 1) after unsuccessful treatment with SAG. Individually, three patients exhibited a decrease in the IgG titers, whereas two showed an increase in the levels. After successful cure with amphotericin B, however, the IgG antibodies in all of the patients were significantly lowered, demonstrating a 96% reduction in the levels in comparison to the unresponsive state (P < 0.05). Despite the decrease, strong IgG titers (1,350 ± 969) persisted even after cure. In contrast, very low levels of LAg-specific IgA isotypes were detected in untreated VL patients, with almost no change after SAG and amphotericin B treatment and after cure (Fig. 1C; Table 1). Low levels of IgM observed during disease on average remained constant after unsuccessful SAG treatment, although some variation was observed from patient to patient. Following treatment with amphotericin B, the IgM levels in all of the patients were reduced, and the average reduction was statistically significant (Fig. 1B; Table 1). Levels of IgE observed during disease remained almost constant after SAG treatment, with only one patient showing a twofold increase in the titer (Fig. 1D). After cure, however, a decrease in the level of IgE was observed in all of the patient sera, and the percent reduction was most significant for IgE (P < 0.001) (Table 1) in comparison with other Ig isotypes.

FIG. 1.

Levels of LAg-specific IgG (A), IgM (B), IgA (C), and IgE (D) in the sera of Indian kala-azar patients before treatment and following SAG unresponsiveness and cure. Symbols represent individual patients, and the same symbols indicating the same patients are used in Fig. 2. The heavy line represents the mean (± standard error) of the Ig isotype level for five individuals.

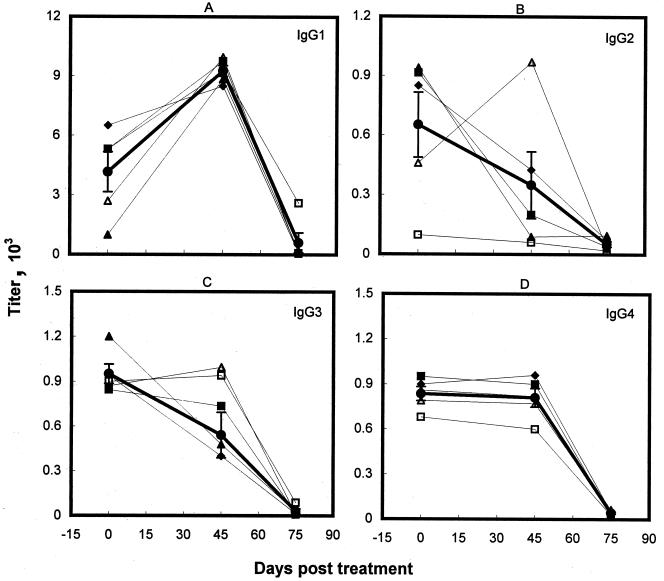

FIG. 2.

Specific IgG subclass levels in kala-azar patient sera before treatment and following SAG resistance and cure. The symbols and the heavy line are as described for Fig. 1.

TABLE 1.

Changes in LAg-specific mean IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgG subclass levels in kala-azar patients following drug resistance and cure

| Isotype | % Reduction

of level in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| SAG-resistant seraa (45 days posttreatment; n = 5) | Sera after

successful treatment

|

||

| Amphotericin B cureb (75 days posttreatment; n = 5) | SAG curea (50 days posttreatment; n = 10) | ||

| IgG | 4.8 | 96d | 91f |

| IgM | 1.8 | 88.5e | 80e |

| IgA | 19.5 | −9.1c | −1.3c |

| IgE | 6.6 | 92g | 97h |

| IgG1 | −123cf | 93.5h | 90.6g |

| IgG2 | 46.5d | 85 | 88.5f |

| IgG3 | 43d | 94e | 91g |

| IgG4 | 3 | 95h | 91h |

Calculated as [(level before treatment) − (level after SAG treatment)] × 100/(level before treatment).

Calculated as [(level during SAG resistance) − (level after amphotericin B cure)] × 100/(level during SAG resistance).

A negative value represents an increase.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.02.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

P << 0.001.

Analysis of the sera for their patterns of IgG subclass antibodies reactive with LAg extracted from L. donovani revealed significantly higher levels of IgG1 in comparison to IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 in untreated VL patients (P < 0.02) (Fig. 2). After unsuccessful SAG treatment, IgG1 increased significantly (P < 0.01), by 2.2-fold in comparison to the untreated state. The increase in IgG1 titer was observed in all five individual patients tested and reached almost equivalent levels (Fig. 2A; Table 1). In contrast, the levels of IgG2 and IgG3 were reduced significantly (Fig. 2; Table 1). Of the five sera tested, only one patient serum showed an increase in the IgG2 and IgG3 levels after SAG treatment. The anti-LAg IgG4 response, however, remained almost constant with antimony therapy, showing minimal variation from patient to patient. Following successful cure with amphotericin B, the levels of all of the IgG subclasses were reduced significantly, with maximum declines in IgG3 and IgG4 antibodies (P << 0.001). Nevertheless, significant LAg-specific IgG1 titers (606 ± 499) persisted in clinically cured individuals.

Serological responses of VL patients successfully cured with SAG.

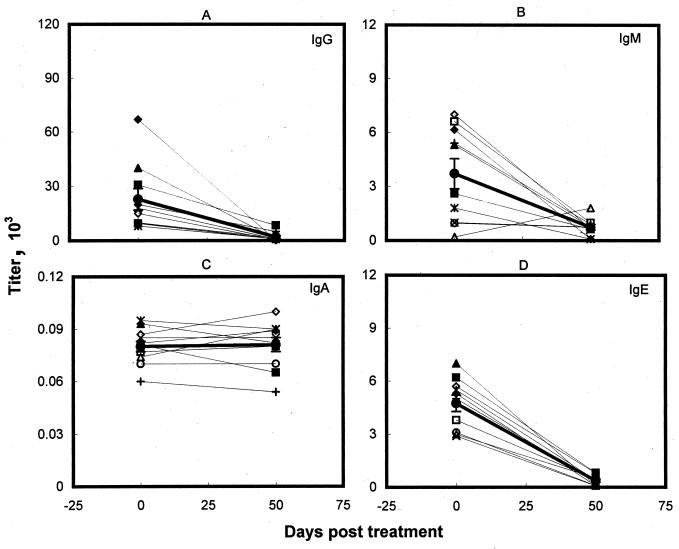

Of the 15 patients investigated in this study, 10 responded to the standard regimen of antimony with good clinical results and parasitological cures. As observed earlier, before treatment was started, all of the patients tested had strong anti-LAg IgG antibodies. After cure, the level of IgG dropped significantly in all of the patient sera (Fig. 3A; Table 1) but still remained measurable (1,971 ± 834). A significant fall in IgE and IgM levels was also observed in all patients except one, who showed an increase in IgM titer (Fig. 3B; Table 1) at the end of treatment. In contrast, the comparatively lower level of anti-LAg specific IgA remained steady before and after therapy with SAG (Fig. 3C). Cure with antimony also corresponded with the most significant decline (97%; P << 0.001) in IgE antibodies.

FIG. 3.

LAg-specific IgG (A), IgM (B), IgA (C), and IgE (D) serum antibodies of kala-azar patients before and after SAG therapy. Symbols represent individual patients, and the same symbols depict the same patients in Fig. 4. The heavy line represents the mean (± standard error) of the Ig isotype level for 10 samples.

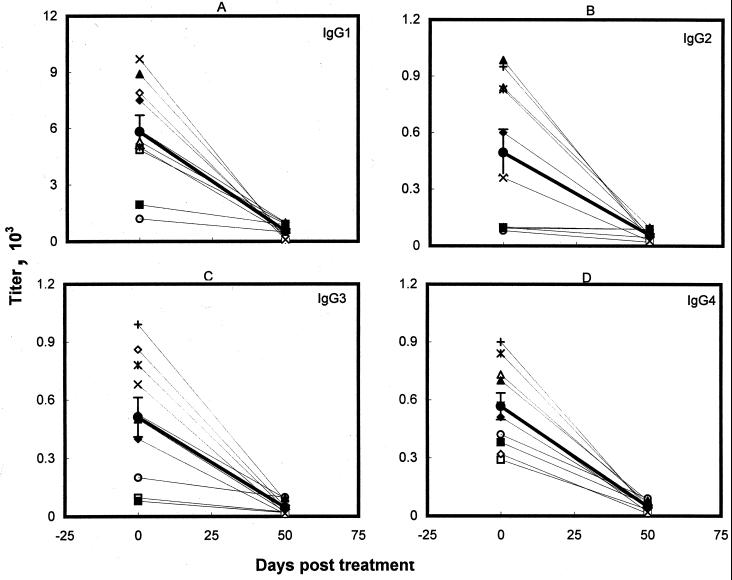

Analysis of the IgG subclass antibodies of the paired pre- and posttreatment serum samples of 10 patients successfully cured with SAG revealed a significant decrease (P < 0.01) in the titers of all of the IgG subclasses (Fig. 4; Table 1). This decline, observed in all of the patients, was most significant for IgG4 antibodies (P << 0.001). Low but significant IgG1 titers (548 ± 115) remained after cure.

FIG. 4.

IgG subclass antibody titers of Indian kala-azar patients before and after treatment with SAG. The symbols and the heavy line are as described for Fig. 3.

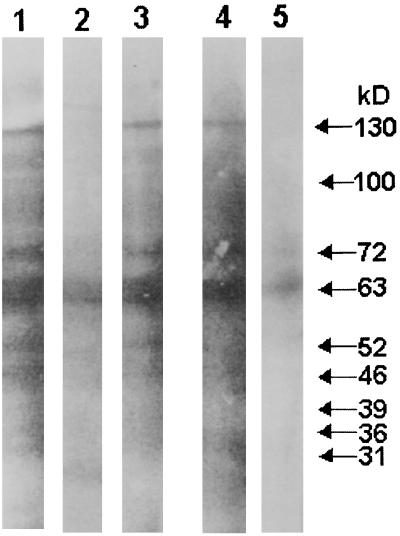

Immunoblot analysis of L. donovani antigens reacting with Indian kala-azar sera.

Membrane antigens of L. donovani run on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels were transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblotting with pre- and posttreatment kala-azar sera. Serum specimens from two patients, one unresponsive to antimony and cured with amphotericin B and the other successfully cured with SAG, were investigated for their reactivity with LAg. Before therapy, both of the patients showed strong reactions with more than 17 antigenic components ranging in molecular mass from 24 to 163 kDa (Fig. 5, lanes 1 and 4). The major reactive components recognized by these untreated samples were 130, 100, 72, 63, 52, 46, 39, 36, and 31 kDa. The serum specimen from the patient unsuccessfully treated with SAG reacted with almost all of the antigenic components recognized before therapy but with an overall lower intensity (Fig. 5, lane 2). After successful cure, the major polypeptides recognized by both the sera (130, 72, 63, 46, and 36 kDa) were similar (Fig. 5, lanes 3 and 5) and were fewer in number than the components of LAg reactive with pretreatment sera. However, the extents of reactivity for both of the serum specimens were variable.

FIG. 5.

Immunoblots of LAg with sera from untreated and cured kala-azar patients. Lanes 1 to 3, reactivity with untreated, SAG-unresponsive, and amphotericin B-cured sera of one kala-azar patient at 0, 45, and 75 days posttreatment, respectively. Lanes 4 and 5, reactivity with untreated and SAG-cured sera of another kala-azar patient at 0 and 50 days posttreatment, respectively. The reactivities with the major bands are indicated on the right.

DISCUSSION

Immunologic abnormalities and successful host defense in VL have been shown to be associated with T-cell responses. The detection of high titers of antileishmanial antibodies has been exploited mainly for the development of serological tests for diagnosis, and very little attention has been given to analysis of antibodies at the isotype and subclass levels in relation to pathogenesis. Most of the serological assays developed so far, however, fail to obviate the need for microscopy as the “gold standard” for diagnosis. Based mainly on the detection of IgG antibodies, these tests show cross-reactivity with other pathogens, including those causing malaria, tuberculosis, or leprosy, which are coendemic with kala-azar, and may remain positive for cured VL sera for long periods of time (19, 22, 35, 38). In a recent report we have demonstrated the Ig subclass distribution and the specificity of IgG3 for the diagnosis of kala-azar (5). In the present study we report the differential response of Ig subclass antibodies after successful chemotherapy and the distinct pattern for drug unresponsiveness in the sera of Indian kala-azar patients.

Acute infection, as reported earlier (5), correlated with elevated levels of IgG, IgM, IgE, and IgG subclasses in both SAG-responsive and unresponsive patients. Although some differences in the levels of these isotypes were observed in the two groups, the difference was statistically significant for only IgG3 and IgG4, their titers being higher in the drug-resistant group. Successful drug therapy demonstrated significant reductions in the levels of IgG, IgM, IgE, and all IgG subclasses in both groups. This decrease in the antibody levels was observed in all but one serum sample, for IgM. The orders for the significance of reduction in the mean levels of antibody responses, however, were IgE > IgG > IgM > IgA and IgG4 > IgG1 > IgG3 > IgG2 for the SAG-cured patients and IgE > IgM > IgG > IgA and IgG1 > IgG4 > IgG3 > IgG2 for the amphotericin B-treated individuals. This difference arose because of the change in the pattern of the isotypes following unsuccessful SAG treatment. Antimony unresponsiveness induced varying effects on the levels of IgG, IgA, IgG2, and IgG3 in the different patients, while the response was more consistent for IgG1, IgG4, and IgE. Average titers revealed insignificant changes in the levels of IgG, IgM, IgA, IgE, and IgG4 and a significant decrease in the response of IgG2 and IgG3. The most noticeable effect, however, was the increase in the titers of IgG1 antibodies observed in all of the patients, rising to almost equal levels. Although it is not understood how these changes in the isotype patterns occur from pretreatment to drug unresponsiveness or cure, it appears that the enhancement of IgG1 after unsuccessful therapy may be a possible marker for the identification of SAG resistance in VL patients. Since almost all of the isotypes decrease markedly with resolution of disease, the steady state of IgE, IgM, and IgG4 in SAG-unresponsive sera may serve as additional markers for drug resistance. Conversely, successful therapy could possibly be monitored by the decline especially in IgE and IgG4 and additionally in IgG1 in SAG-unresponsive amphotericin B-treated individuals. These preliminary results are sufficiently promising to warrant further validation to determine their potential as markers in kala-azar.

Leishmania-specific elevations of IgG subclasses in VL patients have been reported for Somali, Sudanese, and Venezuelean populations. Similar to our observations, Venezuelan and Somali patient sera had dominant IgG1 antibodies (41, 47). However, in Sudanese patients there was maximum generation of IgG3 and IgG4 production (18). Again, cure correlated with a decrease in only IgG3 and IgG1 antibody titers in the Sudanese patient sera. The discrepancies in these results may be due partly to ethnic variation and differences in parasitic genotypes and partly to the specificities of the antibodies for the antigens studied (21, 44). In order to identify the immunodominant leishmanial proteins in our antigen preparation and their involvement in the pathological consequences, follow-up sera from two kala-azar patients were reacted with immunoblots of LAg. Both of the acute-phase sera showed similar reactivities to various leishmanial antigens. A number of the major antigens recognized (130, 100, 72, 63, 52, 46, 39, 36, and 31 kDa) are expressed by different forms of leishmaniasis (9, 12, 14, 30) and recognize VL sera from different geographic regions (6, 23, 32, 33, 36, 38, 42). While SAG resistance did not induce a major change in the antigenic reactivity, sera obtained after successful therapy recognized fewer bands in LAg. Of interest is the disappearance of the 39- and 31-kDa antigens, which were found to be nonreactive in cured kala-azar patients and asymptomatic subjects by other workers (32, 43).

Since the immunologic mechanisms underlying the profound stimulation of the specific Ig isotypes in patients with kala-azar remain undefined, the modulation of their response with chemotherapy also is not understood. Cytokines produced by helper T cells have been implicated in the regulation of isotype switching by activated B cells, and in mice IFN-γ, preferentially secreted by the Th1 subset, has been shown to stimulate the production of complement-fixing IgG2a and IgG3 antibodies (16, 45). The signature cytokines of Th2 cells, IL-4 and IL-5, are recognized as helpers for B lymphocytes and stimulate the production of high levels of IgE, IgM, and non-complement-fixing IgG isotypes such as IgG1 in mice or its homologue IgG4 in humans (1, 39). In murine models of Leishmania infections, a Th2–IL-4–IgG1 response has been associated with susceptibility and a Th1–IFN-γ–IgG2a response has been associated with protective immunity (2, 3, 11). Similarly, significant stimulation of IgM, IgE, and IgG4 in kala-azar patients may be correlated with the elevation of a Th2 response. Simultaneous elicitation of IgG1, IgG3, and IgG2, however, is difficult to explain. Since IgG1 and IgG3 have the greater ability to fix complement in humans and to mediate inflammatory reactions (24), which is also the principal function of Th1 cells, elevation of these isotypes may reflect the activity of the Th1 subset. The occurrence of both Th1 and Th2 subsets of T-helper cells during active VL has been well documented through the detection of serum and lesional cytokines (20, 26, 46, 48). Since a distinct pattern of cytokines has not been identified with drug resistance and even after cure, assessment of the immune status of patients through cytokine analysis is still not feasible (7, 27, 28). In contrast, a steady level of IgM, IgE, and IgG4 following unsuccessful drug therapy may be correlated with disease persistence during clinical relapse. The increase in IgG1 reflects its inability to down regulate the disease-promoting effects of Th2 cells. Resolution of infection corresponds to a decline most significantly of IgE and IgG4, which further points to the significance of Th2 cells in the pathogenesis of kala-azar and its regulation in the control of the disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the patients of the School of Tropical Medicine, Calcutta, India, who participated to this study. We thank J. Das and D. K. Ganguly, past and present directors, respectively, of the Indian Institute of Chemical Biology, Calcutta, for supporting this work.

This work was supported through grants from the CSIR and the DST, Government of India, and the UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. K.A. is a research fellow supported by ICMR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas A K, Murphy K M, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–793. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afrin F, Ali N. Adjuvanticity and protective immunity elicited by Leishmania donovaniantigen encapsulated in positively charged liposomes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2371–2377. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2371-2377.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afrin F, Ali N. Isotype profiles of Leishmania donovaniinfected BALB/c mice: preferential stimulation of IgG2a/b by liposome associated promastigote antigens. J Parasitol. 1998;84:743–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali N, Afrin F. Protection of mice against visceral leishmaniasis by immunization with promastigote antigen incorporated in liposome. J Parasitol. 1997;83:70–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anam K, Afrin F, Banerjee D, Pramanik N, Guha S K, Goswami R P, Gupta P N, Saha S K, Ali N. Immunoglobulin subclass distribution and diagnostic value of Leishmania donovaniantigen-specific immunoglobulin G3 in Indian kala-azar patients. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:231–235. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.2.231-235.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badaro R, Benson D, Eulalio M C, Freire M, Cunha S, Netto E M, Predral-Sampaio D, Madureira C, Burns J M, Houghton R L, David J R, Reed S G. rK39: a clonal antigen of Leishmania chagasithat predicts active visceral leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:758–761. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahrenscheer J, Kemp M, Kurtzhals J A L, Gachihi G S, Kharazmi A, Theander T G. Interferon-γ and interleukin-4 production by human T cells recognizing Leishmania donovaniantigens separated by SDS-PAGE. APMIS. 1995;103:131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batteiger B, Newhall W J V, Jones R B. The use of Tween 20 as blocking agent in the immunological detection of proteins transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. J Immunol Methods. 1982;55:297–307. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(82)90089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouvier J, Etges R, Bordier C. Identification of promastigote surface protease in seven species of Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1987;24:73–79. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(87)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bray R S. Immunodiagnosis of leishmaniasis. In: Cohen S, Sadun E H, editors. Immunology of parasite infections. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1976. pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bretscher P A, Wei G, Menon J N, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. Establishment of stable, cell-mediated immunity makes “susceptible” mice resistant to Leishmania major. Science. 1992;257:539–542. doi: 10.1126/science.1636090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns J M, Jr, Shreffler W G, Benson D R, Ghalib H W, Badaro R, Reed S G. Molecular characterization of a kinensin-related antigen of Leishmania chagasithat detects specific antibody in African and American visceral leishmaniasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:775–779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carvalho E M, Badaro R, Reed S G, Jones T C, Johnson W D. Absence of gamma interferon and interleukin 2 production during visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Investig. 1985;76:2066–2069. doi: 10.1172/JCI112209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Champsi J, McMahon-Pratt D. Membrane glycoprotein M-2 protects against Leishmania amazonensisinfection. Infect Immun. 1988;56:3272–3279. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.12.3272-3279.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cillari E, Liew F Y, Campo P L, Milano S, Mansueto S, Salerno A. Suppression of IL-2 production by cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with active visceral leishmaniasis in Sicily. J Immunol. 1988;140:2721–2726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coffman R L, Lebman D A, Rothman P. The mechanism and regulation of immunoglobulin isotype switching. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:229–270. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desjeux P. Human leishmaniasis: epidemiology and public health aspects. World Health Stat Q. 1992;45:267–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elassad A M S, Younis S A, Siddig M, Grayson J, Petersen E, Ghalib H W. The significance of blood levels of IgM, IgA, IgG and IgG subclasses in Sudanese visceral leishmaniasis patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;95:294–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fargeas C, Hommel M, Maingon R, Dourado C, Monsigny M, Mayer R. Synthetic peptide-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for serodiagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:241–248. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.241-248.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghalib H W, Piuvezam M R, Skeiky Y A W, Siddig M, Hashim F A, El-Hassan A M, Russo D M, Reed S G. Interleukin 10 production correlates with pathology in human Leishmania donovaniinfections. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:324–329. doi: 10.1172/JCI116570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh A K, Dasgupta S, Ghose A C. Immunoglobulin G subclass-specific antileishmanial antibody responses in Indian kala-azar and post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:291–296. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.3.291-296.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hailu A. Pre- and post-treatment antibody levels in visceral leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:673–675. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaffe C L, Zalis M. Purification of two Leishmania donovanimembrane antigens recognized by sera from patients with visceral leishmaniasis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1988;27:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jefferis R. Structure/function relationships of IgG subclasses. In: Shakib F, editor. The human IgG subclasses: molecular analysis of structure, function and regulation. London, United Kingdom: Pergamon Press; 1990. pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jha T K, Olliaro P, Thakur C P N, Kanyok T P, Singhania B L, Singh I J, Singh N K P, Akhoury S, Jha S. Randomised controlled trial of aminosidine (paromomycin) ν sodium stibogluconate for treating visceral leishmaniasis in North Bihar, India. Br Med J. 1998;316:1200–1205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karp C L, El-Safi S H, Wynn T A, Satti M M H, Kordofani A M, Hashim F A, Hag-Ali M, Neva F A, Nutman T B, Sacks D L. In vivo cytokine profiles in patients with kala-azar. Marked elevation of both interleukin 10 and interferon-gamma. J Clin Investig. 1993;91:1644–1648. doi: 10.1172/JCI116372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kemp M, Kurtzhals J A L, Bendtzen K, Poulsen L K, Hansen M B, Koech D K, Kharazmi A, Theander T G. Leishmania donovani-reactive Th1- and Th2-like T-cell clones from individuals who have recovered from visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1069–1073. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.1069-1073.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenny R T, Sacks D L, Gam A A, Murray H W, Sundar S. Splenic cytokine responses in Indian kala-azar before and after treatment. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:815–819. doi: 10.1086/517817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurtzhals J A L, Hey A S, Theander T G, Odera E, Christensen C B V, Githure J I, Koech D K, Schaefer K U, Handman E, Kharazmi A. Cellular and humoral immune responses in a population from the Baringo District, Kenya, to Leishmaniapromastigote lipophosphoglycan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:480–488. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kutner S, Pellerin P, Breniere S F, Desjeux P, Dedet J P. Antigenic specificity of the 72-kilodalton major surface glycoprotein of Leishmania braziliensis braziliensis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:595–599. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.3.595-599.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marty P, Lelievre A, Quaranta J-F, Suffia I, Eulalio M, Gari-Toussaint M, Le Fichoux Y, Kubar J. Detection by western blot of four antigens characterizing acute clinical leishmaniasis due to Leishmania infantum. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:690–691. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mary C, Lamouroux D, Dunan S, Quilici M. Western blot analysis of antibodies to Leishmania infantumantigens: potential of the 14-kD and 16-kD antigens for diagnosis and epidemiologic purposes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:764–771. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neogy A B, Nandy A, Dastidar B G, Chowdhury A B. Antibody kinetics in kala-azar in response to treatment. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1987;81:727–729. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1987.11812177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pal A, Mukerji K, Basu D, Naskar K, Mullick K K, Ghosh D K. Evaluation of direct agglutination test (DAT) and ELISA for serodiagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in India. J Clin Lab Anal. 1991;5:303–306. doi: 10.1002/jcla.1860050502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qu J-Q, Zhong L, Masoom-Yasinzai M, Abdur-Rab M, Aksu H S Z, Reed S G, Chang K-P, Gilman-Sachs A. Serodiagnosis of Asian leishmaniasis with a recombinant antigen from the repetitive domain of a Leishmaniakinensin. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:543–545. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rezai H R, Ardehali S M, Amirhakimi G, Kharazami A. Immunological features of kala-azar. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:1079–1083. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rolland-Burger L, Rolland X, Grieve C W, Monjour L. Immunoblot analysis of the humoral immune response to Leishmania donovani infantumpolypeptides in human visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1429–1435. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.7.1429-1435.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothman P, Coffman R L. Immunoglobulin heavy chain class-switching. In: Herzenberg L A, editor. Weir's handbook of experimental immunology. 5th ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1996. pp. 19.1–19.14. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sacks D L, Lal S L, Shrivastava S N, Blackwell J, Neva F A. An analysis of T cell responsiveness in Indian kala-azar. J Immunol. 1987;138:908–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiddo S A, Huldt G, Nilsson L-A, Ouchterlony O, Thorstensson R. Visceral leishmaniasis in Somalia. Significance of IgG subclasses and of IgE response. Immunol Lett. 1996;50:87–93. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(96)02529-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shreffler W G, Burns J M, Jr, Badaro R, Ghalib H W, Button L L, McMaster W R, Reed S G. Antibody responses of visceral leishmaniasis patients to gp63, a major surface glycoprotein of Leishmaniaspecies. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:426–430. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh S, Gilman-Sachs A, Chang K-P, Reed S G. Diagnostic and prognostic value of k39 recombinant antigen in Indian leishmaniasis. J Parasitol. 1995;81:1000–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skeiky Y A W, Benson D R, Costa J L M, Badaro R, Reed S G. Association of Leishmaniaheat shock protein 83 antigen and immunoglobulin G4 antibody titers in Brazilian patients with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5368–5370. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5368-5370.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snapper C M, Paul W E. Interferon γ and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate Ig isotype production. Science. 1987;236:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sundar S, Reed S G, Sharma S, Mehrotra A, Murray H W. Circulating T helper 1 (Th1) cell- and Th2 cell-associated cytokines in Indian patients with visceral leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:522–525. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ulrich M, Rodriguez V, Centeno M, Convit J. Differing antibody IgG isotypes in the polar forms of leprosy and cutaneous leishmaniasis characterized by antigen-specific T cell anergy. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;100:54–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zwingenberger K, Harms G, Pedrosa C, Omena S, Sandkamp B, Neifer S K. Determinants of the immune response in visceral leishmaniasis. Evidence for the predominance of endogenous interleukin 4 over interferon gamma production. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;57:242–249. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(90)90038-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]