This editorial refers to ‘Identification of undiagnosed atrial fibrillation using a machine learning risk-prediction algorithm and diagnostic testing (PULsE-AI) in primary care: a multi-centre randomized controlled trial in England', by N.R. Hill et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjdh/ztac009.

To see things in the seed, that is genius.

Lao-Tzu

Undiagnosed atrial fibrillation (AF) is an important cause of stroke.1 AF screening may enable prompt detection of AF and initiation of oral anticoagulation (OAC) to prevent stroke.2 The 2007 SAFE trial reported a roughly 50% increase in AF diagnosis with screening individuals aged ≥65 years using electrocardiography (ECG) with or without pulse palpation,3 resulting in a Class I recommendation from the European Society of Cardiology4 and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand5 for AF screening using ECG among individuals aged ≥65 years.

However, more recent studies suggest that mass screening may not be effective.6,7 The efficiency of AF screening may be improved by AF risk estimation,8 which is feasible using clinical risk scores.9 However, such scores have had limited uptake due to complexity, modest predictive performance, and lack of automation.10 Machine learning, a form of artificial intelligence (AI) comprising a variety of models utilizing iterative adjustment to minimize prediction error,11 has demonstrated promise in disease risk prediction and has potential to address many of these limitations. Beyond prediction and screening, AI can influence how we treat patients with AF and potentially impact outcomes.

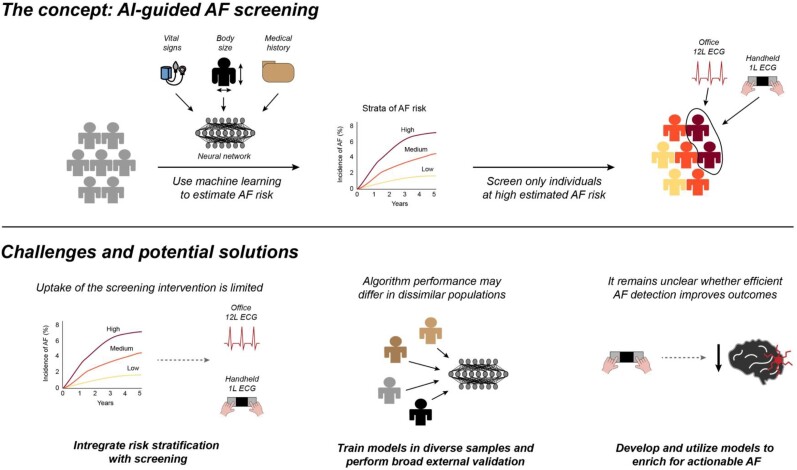

This issue of European Heart Journal: Digital Health reports the results of prediction of undiagnosed atrial fibrillation using a machine learning algorithm (PULsE)-AI,12 a multi-centre randomized controlled trial testing use of a neural network AI model to identify individuals at high AF risk, who were then targeted for screening using 12-lead ECG and serial one-lead handheld ECG (Figure 1). Across six general practices in England, 23 745 participants aged ≥30 years without known AF were randomly allocated to intervention (n = 11 849) and control (n = 11 896) arms. A total of 768 individuals in the intervention arm with high AI-predicted risk of AF were offered AF screening, of whom 256 (33.3%) accepted. Individuals in the control group received usual care. Over the 20-month study period (extended from 6 months due to the COVID-19 pandemic), the incidence of the primary endpoint of AF, atrial flutter, and fast atrial tachycardia was 5.63 and 4.93% among individuals at high predicted AF risk in the intervention and control arms, respectively, which was not a statistically significant difference [odds ratio (OR) 1.15, 95% CI 0.77–1.73, P = 0.486]. Among intervention participants who actually underwent screening, however, the rate of the primary endpoint was 9.41%, which was substantially greater than the control rate (OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.31–3.73, P = 0.003).

Figure 1.

Overview of artificial intelligence-guided atrial fibrillation screening. Depicted is a summary of artificial intelligence-guided atrial fibrillation screening, the overall concept assessed in the PULsE-artificial intelligence study. The top panel provides an overview of the concept of artificial intelligence-enabled atrial fibrillation risk estimation to guide screening, in which only individuals who are estimated to have elevated atrial fibrillation risk using artificial intelligence are offered the screening intervention. The bottom panel highlights several challenges associated with artificial intelligence-based atrial fibrillation screening, with potential solutions proposed below.

Discussion

PULsE-AI is an important demonstration of prospective randomized assessment of an AI model intended to guide clinical practice. Despite a recent proliferation of AI-based models to predict disease,11 there has been comparably little integration of AI models into real-world clinical practice.10,11 Valid concerns surrounding clinical AI models include the potential for overfitting (i.e. poorer performance in populations distinct from those in which models were derived), thereby limiting their generalizability. Beyond this there are also concerns regarding whether AI models may disrupt clinical workflows on account of complexity, computation time, or provider apprehension.10 To this end, randomized assessment is critical to establish whether prospective deployment of AI models is feasible, valid, and clinically effective. Only by meeting such a standard will AI models gain widespread acceptance in clinical practice.

In this case, despite successful implementation, AI-enabled screening did not meaningfully improve AF detection, with similar AF diagnosis rates between the intervention and controlarms. Nevertheless, the AF diagnosis rate was roughly two-fold higher among those randomized to intervention who ultimately underwent screening, when compared with controls. Although the latter per-protocol analysis is subject to selection bias and must be interpreted with caution, it highlights the reality that for any AI-based intervention to be effective, it must be broadly acceptable to its target population. To this end, only a third of individuals invited to screening ultimately adhered. The authors propose that unfamiliarity with contemporary technology (e.g. one-lead ECG) may have been an important barrier. Importantly, this highlights the risk of furthering disparities in care especially amongst the elderly, rural, and disenfranchised communities. However, given evidence suggesting that electronic risk management may improve outcomes in AF,13 we submit that a fully remote screening option may have improved participation, particularly given the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, in the future both AF risk estimation and active screening may even be performed using the same mobile technology (Figure 1).

PULsE-AI also provides an important demonstration of the potential for risk estimation to improve the efficiency of AF screening. The AI algorithm the investigators deployed was generally accurate, as individuals predicted to have elevated AF risk (i.e. AF probability ≥7.4%, a threshold corresponding to 90% specificity in the algorithm’s derivation) had an AF diagnosis rate of approximately 5%, as compared to 0.6% among individuals not classified as high-risk. Although there is evidence for some miscalibration, since one would expect an AF diagnosis rate greater than 5% when using a risk threshold of 7.4%, such enrichment remains powerful when compared to recent AF screening trials which report AF incidence rates of roughly 1–2%/year among individuals aged ≥65 years (i.e. those with a guideline-based indication for AF screening4,5). Future work is needed to establish whether AF risk estimation may be deployed more broadly to prioritize individuals for AF screening and whether such screening improves outcomes.

Although the work by Hill et al.12 is an important advance, several important considerations remain. Notably, their algorithm utilizes a vast array of detailed clinical risk factor information to generate predictions. Recent models utilizing AI-enabled analysis of raw data (e.g. ECG14,15) may reduce reliance on electronic health record-based clinical inputs which may be subject to misclassification. Beyond this, even very efficient AF detection may fail to improve outcomes if screen-detected AF is not truly actionable. Future work is needed to assess whether AI-based methods can be used to enrich for actionable AF and better integrate diagnosis with initiation of oral anticoagulationand other preventive interventions. Third, prospective evaluation is key, but AI-based risk models also require broad external validation in dissimilar populations (e.g. outside the UK) before generalizability can be established.

In summary, PULsE-AI provides demonstration of the feasibility of AI-based AF risk estimation and provides a good example of how to deploy and assess clinical AI-based interventions. Whether AI-enabled AF risk estimation can improve the efficiency of AF screening and lead to improved outcomes will need further investigation. It is quite possible that these calculated risks will yield considerable rewards.

Contributor Information

Shaan Khurshid, Demoulas Center for Cardiac Arrhythmias, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, GRB 8-842, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Cardiovascular Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Jagmeet P Singh, Demoulas Center for Cardiac Arrhythmias, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, GRB 8-842, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Cardiovascular Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Data availability

This editorial does not include any original data.

References

- 1. Michaud GF, Stevenson WG. Atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khurshid S, Healey JS, McIntyre WF, Lubitz SA. Population-based screening for atrial fibrillation. Circ Res 2020;127:143–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fitzmaurice DA, Hobbs FDR, Jowett S, Mant J, Murray ET, Holder R, Raftery JP, Bryan S, Davies M, Lip GYH, Allan TF. Screening versus routine practice in detection of atrial fibrillation in patients aged 65 or over: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007;335:383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan G-A, Dilaveris PE, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Kalman JM, La Meir M, Lane DA, Lebeau J-P, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Pinto FJ, Thomas GN, Valgimigli M, Van Gelder IC, Van Putte BP, Watkins CL, ESC Scientific Document Group . 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021;42:373–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. NHFA CSANZ Atrial Fibrillation Guideline Working Group, Brieger D, Amerena J, Attia J, Bajorek B, Chan KH, Connell C, Freedman B, Ferguson C, Hall T, Haqqani H, Hendriks J, Hespe C, Hung J, Kalman JM, Sanders P, Worthington J, Yan TD, Zwar N. National Heart Foundation of Australia and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Australian clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation 2018. Heart Lung Circ 2018; 27:1209–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lubitz SA, Atlas SJ, Ashburner JM, Trisini Lipsanopoulos AT, Borowsky LH, Guan W, Khurshid S, Ellinor PT, Chang Y, McManus DD, Singer DE. Screening for atrial fibrillation in older adults at primary care visits: the VITAL-AF randomized controlled trial. Circulation 2022;145:946–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Uittenbogaart SB, Verbiest-van Gurp N, Erkens PMG, Lucassen WAM, Knottnerus JA, Winkens B, van Weert HCPM, Stoffers HEJH. Detecting and diagnosing atrial fibrillation (D2AF): study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khurshid S, Mars N, Haggerty CM, Huang Q, Weng L-C, Hartzel DN, Lunetta KL, Ashburner JM, Anderson CD, Benjamin EJ, Salomaa V, Ellinor PT, Fornwalt BK, Ripatti S, Trinquart L, Lubitz SA. Predictive accuracy of a clinical and genetic risk model for atrial fibrillation. Circ Genom Precis Med 2021;14:e003355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alonso A, Krijthe BP, Aspelund T, Stepas KA, Pencina MJ, Moser CB, Sinner MF, Sotoodehnia N, Fontes JD, Janssens ACJW, Kronmal RA, Magnani JW, Witteman JC, Chamberlain AM, Lubitz SA, Schnabel RB, Agarwal SK, McManus DD, Ellinor PT, Larson MG, Burke GL, Launer LJ, Hofman A, Levy D, Gottdiener JS, Kääb S, Couper D, Harris TB, Soliman EZ, Stricker BHC, Gudnason V, Heckbert SR, Benjamin EJ. Simple risk model predicts incidence of atrial fibrillation in a racially and geographically diverse population: the CHARGE-AF consortium. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rajpurkar P, Chen E, Banerjee O, Topol EJ. AI in health and medicine. Nat Med 2022;28:31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deo RC. Machine learning in medicine. Circulation 2015;132:1920–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hill NR, Groves L, Dickerson C, Ochs A, Pang D, Lawton S, Hurst M, Pollock KG, Sugrue DM, Tsang C, Arden C, Davies DW, Martin A-C, Sandler B, Gordon J, Farooqui U, Clifton D, Mallen C, Rogers J, Camm AJ, Cohen AT. Identification of undiagnosed atrial fibrillation using a machine learning risk prediction algorithm and diagnostic testing (PULsE-AI) in primary care: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial in England. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2022;ztac009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guo Y, Lane DA, Wang L, Zhang H, Wang H, Zhang W, Wen J, Xing Y, Wu F, Xia Y, Liu T, Wu F, Liang Z, Liu F, Zhao Y, Li R, Li X, Zhang L, Guo J, Burnside G, Chen Y, Lip GYH, Guo Y, Lip GYH, Lane DA, Chen Y, Wang L, Eckstein J, Thomas GN, Tong L, Mei F, Xuejun L, Xiaoming L, Zhaoliang S, Xiangming S, Wei Z, Yunli X, Jing W, Fan W, Sitong Y, Xiaoqing J, Bo Y, Xiaojuan B, Yuting J, Yangxia L, Yingying S, Zhongju T, Li Y, Tianzhu L, Chunfeng N, Lili Z, Shuyan L, Zulu W, Bing X, Liming L, Yuanzhe J, Yunlong X, Xiaohong C, Fang W, Lina Z, Yihong S, Shujie J, Jing L, Nan L, Shijun L, Huixia L, Rong L, Fan L, Qingfeng G, Tianyun G, Yuan W, Xin L, Yan R, Xiaoping C, Ronghua C, Yun S, Yulan Z, Haili S, Yujie Z, Quanchun W, Weidong S, Lin W, Chan E, Guangliang S, Chen Y, Wei Z, Dandi C, Xiang H, Anding X, Xiaohan F, Ziqiang Y, Xiang G, Fulin G. Mobile health technology to improve care for patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:1523–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khurshid S, Friedman S, Reeder C, Di Achille P, Diamant N, Singh P, Harrington LX, Wang X, Al-Alusi MA, Sarma G, Foulkes AS, Ellinor PT, Anderson CD, Ho JE, Philippakis AA, Batra P, Lubitz SA. Electrocardiogram-based deep learning and clinical risk factors to predict atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2022;145:122–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raghunath S, Pfeifer JM, Ulloa-Cerna AE, Nemani A, Carbonati T, Jing L, vanMaanen DP, Hartzel DN, Ruhl JA, Lagerman BF, Rocha DB, Stoudt NJ, Schneider G, Johnson KW, Zimmerman N, Leader JB, Kirchner HL, Griessenauer CJ, Hafez A, Good CW, Fornwalt BK, Haggerty CM. Deep neural networks can predict new-onset atrial fibrillation from the 12-lead electrocardiogram and help identify those at risk of AF-related stroke. Circulation 2021;143:1287–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This editorial does not include any original data.