Abstract

The worldwide disaster caused by COVID-19 and its variants has changed the behavior and psychology of consumers. Panic buying and hoarding of various commodities continue to emerge in our daily life. Meanwhile, many scholars have focused on the causes of panic buying and hoarding of physical products like daily necessities and food during the outbreak of COVID-19. In fact, the phenomenon of panic buying and digital hoarding of paid social Q&A and other digital content products is very prominent, both in the outbreak period of COVID-19 epidemic and the current coexistence stage. However, the existing literature lacks empirical research to explore this phenomenon, and the psychological mechanism behind it has not been clearly revealed. Therefore, at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, based on the SOBC framework, we developed a theoretical model and explored the causes of panic buying and digital hoarding in paid social Q&A. The data collected from 863 paid social Q&A users in China are empirically tested. The results show that the characteristics of paid social Q&A (usefulness, ease of use, professionalism and value) can cause emotional contagion among platform users, activate their willingness to pay, and finally lead to digital hoarding and panic buying behavior of COVID-19 co-existence stage. In addition, the sensitivity to pain of payment moderates the relationship between emotional contagion and willingness to pay. Compared with the spendthrifts, the tightwads are more willing to pay. The conclusions will have positive significance for improving the retail service of digital content platform and promoting the consumption of digital content.

Keywords: Paid social Q&A, Panic buying, Digital hoarding, Emotional contagion, Sensitivity to pain of payment

1. Introduction

COVID-19 and its mutants (such as Omicron, Delta, lambda, etc.) have caused worldwide economic and medical damage, which has brought fear, panic and uncertainty to people nearly around the world. Panic buying has become one of the typical characteristics of consumer behavior during and aftermath of COVID-19. For example, people snapped up toilet paper, important medicines, masks, liquid soaps, gloves, groceries, and food in the United States, Britain, Australia, Portugal, South Korea, and China during COVID-19 [1,2,28]. In addition to the panic buying and hoarding behaviors caused by the fear of shortage of physical products, people's mental pressure and unemployment worries caused by the epidemic have also significantly increased their consumption of digital content products [3].

Different from panic buying and hoarding of physical products, panic buying of digital content products is generally manifested in the immediate payment and participation of users online. With the content perishability of digital content products, users’ digital hoarding behaviors are generally more manifested in collecting a large number of blogger materials or contents in their favorites on the digital content platform [4]. For example, paid social Q&A, a typical digital content product in China, was also one of the targets of hoarding and panic buying during COVID-19, about 90% of Chinese online learners have purchased paid knowledge products, and the most frequently purchased products are column subscriptions, paid lectures and paid questions and answers1. In addition, some bloggers specialized in career, education, skill improvement and other columns has been favorited by users as many as 470,000 times on the Zhihu social Q&A platform.

Therefore, panic buying and hoarding behaviors of both physical products and digital content products have become a global phenomenon. Many existing literatures have studied the panic buying and hoarding behaviors of daily necessities, medicines and food during the period of COVID-19 [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. Scholars believe that individual psychological factors [[5], [6], [7]] and social psychological factors are the main factors triggering people panic buying and hoarding food during the epidemic [[8], [9], [10]]. The COVID-19 is known as “the deadliest plague of the century” [17], it damages not only the material world of human beings, but also the spiritual world. However, there is still a lack of discussion to systematically explore the antecedents, consequences and processes of panic buying and digital hoarding behaviors of digital content products related to human spiritual world in the current literature.

With the development of digital media, the global consumption of digital content has shown a significant growth trend in recent years [18]. As a typical digital content product, paid social Q&A is an innovative application in the Internet field [19]. For example, Quora, Pearl, Stack Exchange, Zhihu and Himalaya are typical social Q&A platforms. During the prevalence of COVID-19 and its mutants, the global offline real economy suffered heavy losses. On the contrary, on many digital content platforms in China, like Zhihu, Weibo and Himalaya, the sales of paid products increased tremendously, more than half of Chinese users have bought knowledge paid products, among which the growth characteristics of young and highly educated people are obvious. Does consumer strong desire for social Q&A stem from the fear of accidental unemployment [[20], [21], [22]], layoffs, salary cuts, loan cuts and bankruptcy affected by COVID-19? Or from the fear of quarantine, COVID-19 infection and death [23]? Perhaps people want to seek information through paid social Q&A to explore possible epidemic survival solutions. A Previous study has shown that operators of paid social Q&A websites try to encourage participants to share their knowledge or promote reciprocity from the extrinsic incentive by using virtual scores [24]. Unlike free social Q&A, paid social Q&A require questioners to pay. Other onlookers who are curious about the answers also need to pay [25]. In addition, sharing the income paid by audience for paid social Q&A products is the main factor to encourage questioners and respondents to contribute content, improve participation and promote content purchase [26]. Therefore, questioners and respondents have the opportunity to get additional monetary rewards, their knowledge sharing behavior and social contact are also stimulated [27]. Therefore, we have to think about a question: is the “recover” of paid social Q&A due to the sharing mechanism (the mechanism for the questioner and the respondent to share the expenses from the paid audiences), the virtual scores incentive, “COVID-19 boom” or paid social Q&A characteristics? Moreover, because digital content products are inherently perishable, that is, the degree to which users' interest and attention in content are attenuated with time. High-perishable content only attracts users at specific time points. Once it expires, the value, attention and usefulness of some paid social Q&A content will drop sharply [26]. Meanwhile, different from the free mode, one problem that can't be ignored about paid social Q&A is the user's willingness to pay. From the type of payers, as users of paid social Q&A-Tightwads and Spendthrifts, which group shows stronger willingness to pay? Consequently, the answers to these questions above are crucial for the development of digital content platform enterprises, social Q&A products, and user conception about content consumption in a long run [29]. However, there is still a lack of deeper research on these issues in the theoretical field. This study has three novel contributions:

-

(1)

It is a challenge to define the panic buying and digital hoarding of digital content products in the coexistence stage with COVID-19. This study tries to make an original conceptual contribution, and it is the first empirical study by using the SOBC framework to conceptualize panic buying and digital hoarding in social paid Q&A. To some extent, this study makes up for the blank of the current literature on panic buying and digital hoarding of digital content products.

-

(2)

According to the Emotional Contagion Theory, with the popularity of social media, emotions break through the limitations of time and space, spread synchronously with information as the carrier, and eventually spread to the whole social network [30]. This diffusion process will infect individuals who have originally no emotional tendency, and the transmission speed and scope are much greater than the traditional group emotional contagion [31]. In addition, the pain of payment theory suggests that individuals with different sensitivity to pain of payment (tightwad vs. spendthrift) will show different behavior under the same stimulation [32,33]. The purpose of this study is to identify and test the differences in emotional contagion of users with different sensitivity to payment pain when faced with some characteristics of paid social Q&A, and to explore the differences in their willingness to pay based on the above theory.

-

(3)

This study confirms the psychological mechanism of panic buying and digital hoarding of paid social Q&A users, which can make up for the current literature vacancy. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, the findings can help users with different sensitivity to pain of payment to evaluate and adjust their digital content consumption control ability, and also help digital content platform enterprises to master the core needs of different types of users, enhance user stickiness and achieve sustainable development in the coexistence stage.

Other parts of this study are structured as follows: Firstly, based on the SOBC framework, this paper reviews the relevant literature on paid social Q&A characteristics, emotional contagion, sensitivity to pain of payment, panic buying and digital hoarding respectively; Secondly, based on the SOBC framework, the research hypotheses and research models are proposed; Thirdly, we specify the process of research design, data collection and questionnaire design; Finally, we make an empirical test on the research hypothesis and discuss the research results. Finally, this study makes an empirical analysis of the research hypothesis, and discusses the research results. The last part is theoretical contribution, practical suggestions, future research prospects and limitations.

2. Literature review and hypothetical development

2.1. SOBC framework

The SOBC (Stimulus-Organism-Behavior-Consequence) framework is used to explain the complex mechanism of human behavior [34], which can provide the foundation for the conceptualization of behavioral consequences. Relevant studies have adopt the SOBC framework to study the antecedents or mechanisms in the consumption field [[35], [36], [37]].

2.1.1. Stimulus in the SOBC framework (S): Paid social Q&A characteristics

Panic buying and digital hoarding of paid social Q&A can be understood as the consequences triggered by external stimulus, that is, external stimulus (such as some paid social Q&A characteristics) can start user emotional contagion mechanism (such as language-mediated association and perspective taking) at the internal psychological level of consumers, and then drive behavioral responses (such as willingness to pay), which further lead to certain consequences (such as digital hoarding and panic buying). Therefore, this study believes that the SOBC framework [34] can provide a suitable framework for analyzing the antecedents and consequences of panic buying and digital hoarding of paid social Q&A.

Since digital content is served through online and mobile platforms, its characteristics can be considered from the information system quality characteristics and the content quality characteristics [38]. Paid social Q&A is a typical digital content product, so its characteristics also include the information system quality characteristics and the content quality characteristics. Previous studies have shown that dissatisfaction with information quality and system quality prompted users to give up free social Q&A, while satisfaction with the two factors prompted them to choose paid social Q&A [25,39]. Specially, the information system quality characteristics have a positive impact on perceived user interests and satisfaction, which can further affect the continuous intention of users to consume and provide information in information exchange virtual communities [40]. The information system quality characteristics of paid social Q&A mainly include usefulness and ease of use [38]. Usefulness indicates the degree to which users trust using information systems to improve business performance; Ease of use mainly refers to the ease of learning of the system and the relax of service use. Moreover, in paid online environment, users show higher expectations for content quality [41], so the content quality characteristics of paid social Q&A mainly include professional [42] and value [43]. Professional refers to the quality of content created by users; Value refers to user money burden and income perception when using new technologies and services. Accordingly, we take usefulness, ease of use, professional and value as the stimulus (S) in the SOBC framework.

2.1.2. Organism in the SOBC framework (O): Emotional contagion

Emotional contagion means that the self-emotions may be affected by others' emotions through conscious or unconscious ways [44]. From the perspective of unconscious way, some studies believe that emotional contagion is primitive, emotional imitation formed unconsciously in which individuals learn others' language and other information independently, and finally achieve emotional unification and express similar emotions [45]. From the perspective of conscious way, believes that emotional contagion is a kind of emotional cognition with conscious involvement, which is controlled by individual advanced cognition [46]. The cognitive mechanisms of conscious emotional contagion mainly include language-mediated association and perspective taking. Language-mediated association mainly refers to inducing the perceiver to imagine the same situation by describing the situation of others through language, which further conduces the same emotional experience [46]. Perspective taking generally refers to “viewing the world from others' eyes”, which is a psychological process in which individuals imagine or speculate others' views and attitudes from others or their situations [47]. Further research shows that social media, which contains emotional content, is becoming an important carrier of online public opinion. Users are vulnerable to emotional contagion when reading these contents [31]. For example, the emotions expressed on Facebook can produce a large-scale contagion effect through social networks [48]. Under the threat of COVID-19 outbreak, using social media alone may not be closely related to abnormal mental health consequences [49]. On the contrary, it may be more critical to ponder the content of interaction with COVID-19. Therefore, in this study, emotional contagion is used to express the psychological process (including conscious and unconscious ways) between external stimulus and behavioral intention, which mainly refers to the emotional contagion process formed by users after being stimulated by paid social Q&A characteristics and triggering behavioral intention. For example, at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, questions and answers on unemployment prevention, skill improvement or health protection flooded into the paid social Q&A platforms, which trigger users’ willingness to pay of paid social Q&A through emotional contagion among platform users. Therefore, this study takes emotional contagion as the organism (O) in the SOBC framework.

2.1.3. Behavior in the SOBC framework (B): Willingness to pay

Willingness to pay refers to the possibility that consumers want to buy goods or services [50], mainly represents the amount people are willing to pay for consumption products or services they want to obtain [51]. This concept is usually used to measure consumers’ perception and evaluation of products or services. The willingness to pay for social Q&A refers to the willingness of users to pay voluntarily for answers on social Q&A platforms [52,53]. Previous studies have shown that the diversity of answers, credibility, cognition of questions, acceptable price and expectation of potential benefits constitute the motivation of users to pay for paid social Q&A [41]. In addition, based on the Pain of Payment Theory, consumers will generate pain of payment in the consumption process, which plays an important role in restraining consumption [54]. Specially, lower pain of paying will spur consumption willingness [33,55]. Individuals with strong sensitivity to pay of payment are the tightwad, while individuals with less sensitive to pay of payment are the spendthrift [32]. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, both the spendthrift and the tightwad users are affected by emotional contagion from the perspective of the sensitivity to pain of payment of paid social Q&A. But which type of users show stronger willingness to pay, and are more easily to digital hoarding and panic buying? The existing literature is still lack of discussion on these issues. Therefore, this study takes willingness to pay as behavior (B) in the SOBC framework.

2.1.4. Consequence in the SOBC framework (C): Panic buying and digital hoarding

Panic buying is a herding behavior with a large number of products purchase after a disaster, which mainly occurs when consumers are expected to suffer a disaster and lack of resources [56]. COVID-19 brings a global catastrophic emergency, which has caused psychological and social stress to individuals [57,60]. When consumers see others hoarding goods on social media which can be seen as a collective behavior, they may even take the same approach. People worried about the shortage of food and daily necessities are 7.5% likely to take panic buying. These consumers think that buying more than what they need can bring security, and they take it as a way to relieve negative emotions [61]. Therefore, at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, panic buying has been taking place both offline and online.

At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, the concurrent abnormal consumption phenomenon is the hoarding behaviors both offline and online. Hoarding originates from the psychological adaptation mechanism in the process of evolution- “fear” [64]. Different from the hoarding behaviors of basic daily necessities and food, digital hoarding, like keeping useless data for a long time or unwilling to delete the accumulated data for fear of being useful in the future [65] refers to the accumulation of digital files at the cost of individual reducing target retrieval ability, which ultimately leads to individual stress and confusion [66]. Knowledge is vital to improve self-worth and gain social status in the future. Information is an important source for acquiring knowledge as a “currency”. Individuals hoard important information to maintain self-advantages [67]. Therefore, digital hoarding is related with people needs to satisfy their security sense, certainty and control. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, users take digital hoarding behaviors to resist the harmful effects of COVID-19.

To sum up, paid social Q&A panic buying can be understood as user immediate payment and participation in paid social Q&A in this study. User digital hoarding behaviors are generally more manifested in collecting a large number of blogger materials or content in the user favorites on the digital content platform. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, behavioral intentions and consequences are triggered through emotional contagion. In addition, panic buying and digital hoarding of paid social Q&A are generally separated and asynchronous. Panic buying of paid social Q&A may not be accompanied by digital hoarding of relevant content. Panic buying and digital hoarding are manipulated as two independent dependent variables in this paper. Therefore, this study takes panic buying and digital hoarding as the consequences (C) in the SOBC framework.

2.2. Hypothesis development and research model

2.2.1. S–O: The relationship between paid social Q&A characteristics and emotional contagion

The information system quality characteristics (usefulness and ease of use) and the content quality characteristics (professional and value) of paid social Q&A are the main stimulus factors at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19. Because of unemployment and intensified competition caused by COVID-19, the information system quality characteristics and the content quality characteristics of paid social Q&A may cause emotional contagion among users. In our study paid social Q&A characteristics include usefulness, ease of use, professional and value.

Usefulness refers to the extent to which users believe that using information systems can improve their business performance [[67], [68], [69]]. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, the usefulness of paid social Q&A refers to the extent to which users perceive that the use of paid social Q&A services is valuable to themselves and beneficial to their work and life. Ease of use refers to the characteristics of easy operation and easy learning of systems and services [67,68]. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, the ease of use of paid social Q&A refers to user perceived ease of use in the paid social Q&A service system and the service. Professional refers to user subjective perception of content quality and disseminator quality [42]. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, the professional of paid social Q&A refers to user subjective cognition of the professionalism, authority of the questioners and respondents of paid social Q&A as well as the quality of the content they create. Price is regarded as the monetary sacrifice for acquiring products [70]. Apart from the perception of price, knowledge consumers also receive additional value and benefits from the communication between knowledge content creators and consumers due to the benefit sharing mechanism (the mechanism by which questioners and respondents can share the expenses of paying users) on the social Q&A platform [71]. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, the value of paid social Q&A refers to the perceived money payment, benefits and interaction when users browse content or participate in paid social Q&A, that is, a trade-off between perceived gains and perceived losses [50].

In addition, recent studies have confirmed that emotions can be transmitted digitally [30,72]. Therefore, the professional level of COVID-19 content information in paid social Q&A can affect user emotional response. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, the “ask” and “answer” on the paid social Q&A platform contain massive content with the keyword of “COVID-19”, which is generated by user questions, answers and discussions about “COVID-19”. Once users find the questions, answers or discussions are professional in paid social Q&A, and can be useful to themselves, they will generate language-mediated association: imagine the same situation by describing others’ situations in language, and further induce the same emotional experience [46]. If the questioner thinks that using the Q&A service is valuable, he will be more willing to pay for these questions [73]. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, when browsing, reading and participating in paid social Q&A, users are exposed to a large number of contents about pandemic health protection, death, infection, unemployment, and economic recession. The views and emotions of some opinion leaders, industry experts and members are easy to trigger emotional imitation and emotional cognition through social Q&A [31]. At the same time, users also generate active perspective taking when they view the questions, discussions or answers in the paid social Q&A useful, accurate or convenient to themselves. Perspective taking is a psychological process. Individuals imagine or speculate the views and attitudes of others from the situation of others or others [47], which generally refers to “viewing the world from the eyes of others”. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, taking others views as cognitive evidence through paid social Q&A, users spread emotions in social media, in which language-mediated association and active perspective taking are the main mechanisms of emotional contagion. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a

The stronger level of the Usefulness in the information system quality characteristics of the paid social Q&A is, the stronger level of the emotional contagion will users get.

H1b

The stronger level of the Ease of Use in the information system quality characteristics of the paid social Q&A is, the stronger level of the emotional contagion will users get.

H2a

The stronger level of the Professional in the content quality characteristics of the paid social Q&A is, the stronger level of the emotional contagion will users get.

H2b

The stronger level of the Value in the content quality characteristics of the paid social Q&A is, the stronger level of the emotional contagion will users get.

2.2.2. O–B: The relationship between emotional contagion and willingness to pay

According to the intergroup emotion theory (IET), individual emotional response is affected by the emotional response of other members in group interaction. When the core group members or opinion leaders appear in the media, most other members of the group are vulnerable to the emotions of these typical members, and imitate their emotions [74]. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, ordinary individual has limited understanding and cognition of COVID-19. Professional opinions, answers, views and research judgments on safety threats, unemployment and economic stress caused by COVID-19 and how to protect them is crucial. Therefore, ordinary people will seek professional and authoritative answers from opinion leaders through paid social questions and answers. Cost, financial benefits, self-improvement and other factors are important antecedents of perceived value of social Q&A [46], and perceived value also affects the questioner’ s willingness to pay [75].

From the perspective of emotional priming, this study explores how paid social Q&A characteristics trigger user willingness to pay through emotional contagion. The difference in user emotional contagion stems from the stimulus difference in paid social Q&A characteristics, which also affects their willingness to pay. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, emotion is closely related to consumption [76], which also enhances consumer willingness to pay. Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or specific Internet forums are important channels for people sharing views, personal experiences, happy events, worries or fears. This is reflected in the sharp increase in terms related to COVID-19 on these channels, which has reached millions by March 2020 [77]. On social media, when consumers find others snapping up and hoarding goods which can be seen as a collective behavior, they will even adopt the same approach, so their willingness to pay increase. Thus, the hypothesis is proposed as below:

H3

The stronger level of the emotional contagion users get, the stronger level of the willingness to pay will users show.

2.2.3. B–C: The relationship between willingness to pay and panic buying and digital hoarding

In the field of consumer behavior, fear appeal has a significant relationship with online purchase [78]. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, people consulted, exchanged, discussed various topics about the epidemic on paid social Q&A posts, and sought the best answers to decline the fear brought by COVID-19. Relevant studies also show that panic buying is significantly related to more frequent shopping and spending more money [12,58,59]. At the same time, during the second wave of COVID-19, Apple pay or Google pay was used by 13% of the generation Z, compared with only 1% of the Generation X and the Generation Y [3]. Therefore, the stronger level of the willingness to pay for social Q&A services (especially mobile payment), the more they spend, the higher purchase frequency, the easier users will trigger panic buying behavior for digital content products at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19.

In addition, the reasons for digital hoarding may be stem from the “fear of infection” [62] and “fear of economic recession”, fear of death [63] and unemployment [79]. To improve competitiveness and obtain the career security sense, the behavior of hoarding digital information is exacerbated. This collection provides convenience for users to pay for Q&A consultation in the future. Furthermore, the reason why the paid social Q&A platform designs a collection function is the expectation of users paying for the digital hoards in their favorites in the future. Therefore, the digital hoarding of social Q&A products is related to user willingness to pay. The digital hoarding of social Q&A products has its particularity, especially refers to the collection behavior of Q&A posts, bloggers’ personal data, etc. On the social Q&A platform. As long as participating in paid social Q&A in the future, user may pay to the blogger and show their willingness to pay. More studies have shown that the reason for user digital hoarding may be to take the stored information as a form of evidence to protect against possible threats in the future [80]. Therefore, digital hoarding is not only an “emotional storage” to solve psychological needs, but also an “instrumental storage” to obtain security sense [81]. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, digital hoarding further aggravates user anxiety, intensifies involution, and exerts serious harm to user psychological resources. The stronger level of the willingness to pay users show, the easier it will be to trigger digital hoarding. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a

The stronger level of the willingness to pay users show, the easier it will be to trigger panic buying.

H4b

The stronger level of the willingness to pay users show, the easier it will be to trigger digital hoarding.

2.2.4. Individual differences in sensitivity to pain of payment

Pain of payment is an emotional response that consumers experience when making payment behavior [82], refers to the psychological pain that an individual feels when people separate from money [54], which is a kind of psychological pain that is different from physiological pain [33,83]. When an individual feel too much or too little pain in paying in his consumption behavior, it may lead to two psychological problems: compulsive shopping and compulsive non-shopping [54].

Pain of payment is not only a situational factor, but also an individual difference variable. Different individuals have different sensitivities to pain of payment. Some people are more sensitive to pain than others [86]. A study divided consumers into two basic types based on the sensitivity to pain of payment: those who feel intense pain when spending money and spend less than what they need are the tightwad; those who feel slight pain when spending money and spend more than what they need are the spendthrift [32]. The consumption influence of differences in pain of payment is moderated by the framework effect. Specially, the tightwad are more sensitive to information, while the spendthrift people are less sensitive to pain of payment [86].

In addition to the difference of the sensitivity of individual consumers, individual difference in pain of payment also depends on different payment methods. The feeling of separation between people and money is different under different ways of payment (cash payment vs. virtual currency payment). People who choose cash payment can intuitively feel the loss of money [82], as a result, the pain of cash payment is more intense [[83], [84], [85]]. While new payment methods (such as credit-card payment and mobile payment) make people lose the realistic sense of monetary separation in transactions [87], and reduce their pain of payment. When paying virtual currency, consumers feel less pain [82].

Different from previous studies, we concentrate more on the differences in the willingness to pay of users with different sensitivity to pain of payment (tightwad vs. spendthrift) after getting emotion contagion from paid social Q&A in the mobile payment environment at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19. This study holds that even under the condition of the same mobile payment, there are differences in payment pain of individual consumers. The sensitivity of pain of payment provides a reference framework for distinguishing the degree of emotional contagion and their consumption control ability of different users when using and experiencing paid social Q&A at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19. More precisely, the spendthrift may be more likely to ignore the stimulus from paid social Q&A. They are less sensitive to the positive or negative questions and answers in paid social Q&A, and their degree of emotional contagion is lower. As a result, their willingness to pay is weaker. On the contrary, the tightwad pays more attention to the content presented in the paid social Q&A. They are more sensitive to group emotions, and their degree of emotional contagion is higher. As a result, their willingness to pay is stronger. Previous studies have used the sensitivity of pain of payment as the moderate variable to study the impact of payment methods on pain of payment [86,88]. Thus, the hypothesis is proposed as below:

H5

The sensitivity of pain of payment (tightwad vs. spendthrift) moderates the relationship between emotional contagion from paid social Q&A and user willingness to pay. Specially, compared with the spendthrift, the tightwad are more susceptible to emotional contagion, and their willingness to pay is stronger.

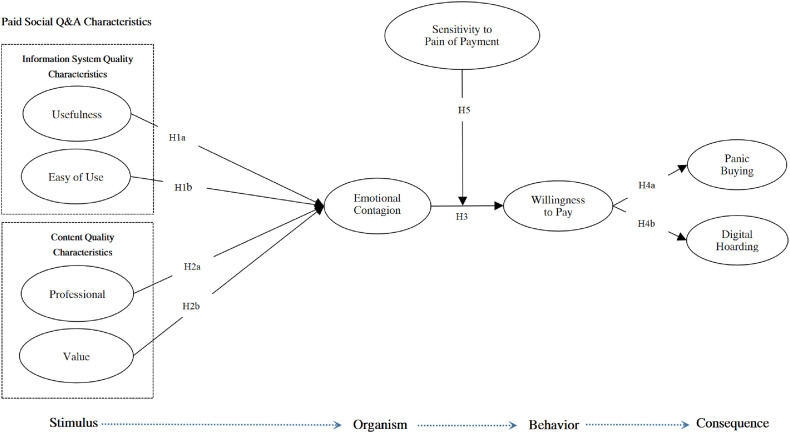

Based on the SOBC framework, the intergroup emotion theory and the pain of payment theory, we propose a theoretical model (see Fig. 1 ). At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, paid social Q&A characteristics (the usefulness, ease of use, professional and value) are extracted from the two dimensions of information system quality and content quality in this study. We further study the process that these characteristics trigger user willingness to pay through emotional contagion, leading to digital hoarding and panic buying. Besides, we explore the moderating role of sensitivity to pain of payment (tightwad vs. spendthrift) between the relationship of emotional contagion and willingness to pay.

Fig. 1.

The Research model.

3. Method

3.1. Participants and procedures

Our research background is based on Zhihu (www.zhihu.com) paid social Q&A products launched on August 2018. More than 150,000 Zhihu respondents have provided personalized and scene-based solutions to consultants through one-on-one consultation. At the same time, these public consultations were paid by millions of Zhihu users to attend in 1 yuan RMB. In May 2021, the paid social Q&A products in Zhihu launched the voice/video consultation function. Compared with the traditional graphic consultation service, the respondent and the consultant can chat face to face, get more immediate feedback, describe and solve more complicated problems, and build a closer emotional connection and trust relationship between the respondent and the consultant. At present, in the live broadcast room in Zhihu, the answering host can attach his own paid consultation portal, and viewers with personalized questions can initiate “one-to-one” consultation to the answering host through the paid consultation portal displayed by the answering host in the live broadcast. By April 2022, the monthly average number of active users in Zhihu reached 101.6 million, up by 19.4% year-on-year, the number of paid members was 6.89 million, up 72.8% year-on-year, and the payment rate was 6.8%2.

This study aims to investigate user willingness to pay, panic buying and digital hoarding behaviors at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19 from the perspective of emotional contagion. Therefore, the proper respondents should have real browsing, payment and collection experience of paid social Q&A at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. On April 22, 2020, the World Health Organization said at a press conference in Geneva that COVID-19 will coexist with mankind for a long time. This study took this point in time as the starting time of “the coexistence period between COVID-19 and human beings”. We have established the user database of social Q&A platform in cooperation with our professional technology company, and screened out the users (n = 1972) who used, paid and collected experiences in Zhihu from December 2020 to March 2022, and randomly selected 1022 users from the sample pool. Then, we invited them to participate in the survey by email on April 15th, 2022. This time span is chosen because these users had snapped up and hoarded digital content products during the coexistence period in COVID-19, which is consistent with the purpose of our research, and the conclusions drawn from this batch of data are more reliable and accurate.

In the invitation email, we inserted a network survey link of “WJX” (https://www.wjx.cn). By providing rewards to the interviewed users (we paid each participant $5 as a reward), we invited them to click on the link to enter the “WJX” platform to fill in the questionnaire. The survey was completed on May 28, 2022. A total of 987 questionnaires were issued, eliminating 124 questionnaires with incomplete items. Finally, 863 valid samples were obtained, with an effective return rate of 87.4%. In addition, we screened out the data of tightwads and spendthrifts from 863 respondents through Tightwad-Spendthrift Scale to test their sensitivity to pain of payment, which was used in the final analysis of this study. The final valid sample (n = 863) consisted of 357 females (41.37%) and 506 males (58.63%). The sample had a mean age of 33.62 years (range 18–49). Education was assessed through three options, and participants were asked to make a choice: 14.72% selected “High school or below”, 64.19% selected “Bachelor degree”, 21.09% selected “Master degree and above”, and no one left the question blank. Monthly income was assessed through four options, 12.51% selected “$1000 and below”, 29.43% selected “$1000 -$2000”, 36.97% selected “$2000 -$3000”, 21.09%selected “$3000 and above”. 97.57% of the respondents reported that they were influenced by COVID-19, and 97.91% respondents used mobile payment. Paid social Q&A form was assessed through three options, and participants were asked to make a choice: 50.41% selected “Image-text”, 29.78% selected “Voice”, 19.81% selected “Video”, and no one left the question blank. In addition, among the final valid sample, 429 samples are tightwads and 434 samples are spendthrifts after the sensitivity to pain of payment test (see Table 1 ). We assured the participants that their responses were confidential and anonymous and would be used only for research.

Table 1.

Respondents’ demographic profile (N = 863).

| Characteristics | All |

Sensitivity to Pain of Payment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tightwads |

Spendthrifts |

|||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 506 | 58.63 | 232 | 45.85 | 274 | 54.15 |

| Female | 357 | 41.37 | 202 | 56.58 | 155 | 43.42 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–29 | 336 | 38.93 | 125 | 37.21 | 211 | 62.79 |

| 30–39 | 323 | 37.43 | 246 | 76.16 | 77 | 23.84 |

| 40–49 | 204 | 23.64 | 86 | 42.16 | 118 | 57.84 |

| Education | ||||||

| High school and below | 127 | 14.72 | 51 | 40.16 | 76 | 59.84 |

| Bachelor degree | 554 | 64.19 | 322 | 58.12 | 232 | 41.88 |

| Master degree and above | 182 | 21.09 | 134 | 73.63 | 48 | 26.37 |

| Monthly income | ||||||

| $1000 and below | 108 | 12.51 | 45 | 41.67 | 63 | 58.33 |

| $1000 -$2000 | 254 | 29.43 | 112 | 44.09 | 142 | 55.91 |

| $2000 -$3000 | 319 | 36.97 | 130 | 40.75 | 189 | 59.25 |

| $3000 and above | 182 | 21.09 | 101 | 55.49 | 81 | 44.51 |

| Influence by COVID-19 | ||||||

| Yes. | 842 | 97.57 | 412 | 48.93 | 430 | 51.07 |

| No. | 21 | 2.43 | 5 | 23.81 | 16 | 76.19 |

| Mobile payment use | ||||||

| Yes. | 845 | 97.91 | 472 | 55.86 | 373 | 44.14 |

| No. | 18 | 2.09 | 3 | 16.67 | 15 | 83.33 |

| Paid social Q&A form | ||||||

| Image-text | 435 | 50.41 | 322 | 74.02 | 113 | 25.98 |

| Voice | 257 | 29.78 | 51 | 19.84 | 206 | 80.16 |

| Video | 171 | 19.81 | 45 | 26.31 | 126 | 73.68 |

| Total | 863 | 100 | 429 | 100 | 434 | 100 |

3.2. Variable measurement

We conducted a survey in Chinese. According to the suggestions of scholars and experts, we have adjusted and translated the items and language descriptions of the initial scale, and made a pretest in 80 samples, and verified the translated scale, finally forming a measurement scale that conforms to the understanding habits of the respondents in China. Items utilize were a 5-point Likert Scale from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Table 2 lists the measurement items of variables.

Table 2.

Constructs and measurement items used in this study.

| Variables | Measurement Items |

|---|---|

| Usefulness(UF) | (Davis, 1989; Moores, 2012; Cheng and Liu, 2017) |

| UF1 | The use of paid social Q&A improves my work and life efficiency at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| UF2 | The use of paid social Q&A makes me feel control over my work and life at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| UF3 | The use of paid social Q&A makes it easier for me to understand, know and predict COVID-19, which saves my time. |

| UF4 | The use of paid social Q&A makes it easier for me to improve my knowledge of COVID-19 health protection and relieve my psychological stress. |

| Easy of Use(EU) | (Davis, 1989; Moores, 2012) |

| EU1 | I feel it is easy to use the paid social Q&A service system at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| EU2 | I feel it is convenient to use the paid social Q&A service system at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| EU3 | It is clear and easy for me to understand the interactive operation of the paid social Q&A service system at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| EU4 | It is easy for me to remember how to use the paid social Q&A service system to ask questions or give answers at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| Professional(PF) | (Du and Xu, 2018) |

| PF1 | The respondents of the paid social Q&A are professional at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| PF2 | The respondents of the paid social Q&A are authoritative at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| PF3 | The content created by the questioners and respondents of the paid social Q&A is professional in the aftermath of COVID-19. |

| PF4 | The content created by the questioners and respondents of the paid social Q&A is authoritative in the aftermath of COVID-19. |

| Value(VL) | (Kim et al., 2012) |

| VL1 | It is valuable for questioners to pay directly for questions rather than spending a lot of time looking for answers from free Q&A at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| VL2 | It is valuable for questioners to pay directly for questions rather than spending a lot of efforts looking for answers from free Q&A at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| VL3 | The questioner can get additional benefits by paid Q&A. I think it is valuable. |

| VL4 | Through output of content, respondents can gain support and recognition from users, and gain corresponding benefits. I think it is valuable. |

| Emotional Contagion(EC) | (Davis, 1980b) |

| EC1 | In the paid social Q&A, when I see warm and touching questions and answers (such as encouraging words) related to COVID-19, I will be touched. |

| EC2 | In the paid social Q&A, when I see sad and melancholy content related to COVID-19, I almost always feel sympathy for the characters. |

| EC3 | In the paid social Q&A, when I see someone's experience of being hurt under the influence of COVID-19, I feel sad and want to help them. |

| EC4 | In the paid social Q&A, when I don't agree or like someone's questions or answers about COVID-19, I usually try to “put myself in his shoes” for a while. |

| EC5 | In the paid social Q&A, I will try to imagine COVID-19 from the perspective of my netizens, so as to better understand my netizens. |

| Willingness to Pay(WTP) | (Zhang et al., 2019) |

| WTP1 | When the answer's heterogeneous resources on paid social Q&A, I am willing to pay at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| WTP2 | When more credible answers exist on paid social Q&A, I am willing to pay at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| WTP3 | When the question I am interested in, or urgent or very important, appears on paid social Q&A, I am willing to pay at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| WTP4 | When the price is affordable on paid social Q&A, I am willing to payat the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| WTP5 | When the expecting potential revenue exist on paid social Q&A, I am willing to pay at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| Panic Buying(PB) | Lins and Aquino (2020) |

| PB1 | The panic about COVID-19 made me spend more on paid social Q&A. |

| PB2 | One way to reduce the uncertainty is to ensure that there are enough paid social Q&A products I need on social Q&A platform at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| PB3 | When I think that paid social Q&A may be time-limited, I will panic, so I will pay for a large number of social Q&A products at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| Digital Hoarding(DH) | (Neave et al., 2019) |

| DH1 | If I delete certain files in my paid social Q&A platform favorites, I feel apprehensive about it afterwards at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| DH2 | I resist having to delete certain files in my paid social Q&A platform favorites at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

| DH3 | Deleting certain files in my paid social Q&A platform favorites would be like losing part of myself at the stage of coexistence with COVID-19. |

3.2.1. Usefulness

The Usefulness Scale is a four-item, self-report inventory that was created for the present study by adapting from Refs. [[67], [68], [69]]. The subjects were asked to complete the scale, based on their true feelings. Higher scores reflect a higher level of usefulness of information system quality characteristics of paid social Q&A. This measure was translated to Chinese and found to have good reliability and validity. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good construct validity (χ2/df = 2.37, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.97, and TLI = 0.98). In our study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.883.

3.2.2. Easy of use

The Easy of Use Scale is a four-item, self-report inventory that was created for the present study by adapting from Refs. [67,68]. The subjects were asked to complete the scale, based on their true feelings. Higher scores reflect a higher level of easy of use of information system quality characteristics of paid social Q&A. This measure was translated to Chinese and found to have good reliability and validity. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good construct validity (χ2/df = 1.86, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.94, and TLI = 0.95). In our study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.875.

3.2.3. Professional

The Professional Scale is a four-item, self-report inventory that was created for the present study by adapting from Ref. [42]. Higher scores reflect a higher level of professional of content quality characteristics of paid social Q&A. The scale has been used in Chinese university students with good reliability and validity [42]. In our study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.881.

3.2.4. Value

The Value Scale is a four-item, self-report inventory that was created for the present study by adapting from Ref. [43]. The subjects were asked to complete the scale, based on their true feelings. Higher scores reflect a higher level of Value of content quality characteristics of paid social Q&A. This measure was translated to Chinese and found to have good reliability and validity. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good construct validity (χ2/df = 2.33, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.97, and TLI = 0.98). In our study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.868.

3.2.5. Emotional contagion

The Emotional Contagion Scale is a five-item, self-report inventory that was created for the present study by adapting from two sub-scales (Empathic Concern Scale and Perspective-taking Scale) of Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) which was developed by Ref. [89]. The subjects were asked to complete the scale, based on their true feelings. Higher scores reflect a higher level of emotional contagion effected by paid social Q&A characteristics. This measure was translated to Chinese and found to have good reliability and validity. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good construct validity (χ2/df = 2.28, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.96, and TLI = 0.95). In our study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.912.

3.2.6. Willingness to pay

The Willingness to Pay Scale is a five-item, self-report inventory that was created for the present study by adapting from Ref. [41]. The subjects were asked to complete the scale, based on their true feelings. Higher scores reflect a higher level of willingness to pay for paid social Q&A. The scale has been used in Chinese university students with good reliability and validity [41]. In our study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.876.

3.2.7. Panic buying

The Panic Buying Scale is a three-item, self-report inventory that was created for the present study by adapting from Ref. [90]. The subjects were asked to complete the scale, based on their true feelings. Higher scores reflect a higher level of panic buying for paid social Q&A. This measure was translated to Chinese and found to have good reliability and validity. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good construct validity (χ2/df = 2.12, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.92, and TLI = 0.93). In our study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.865.

3.2.8. Digital hoarding

The Digital Hoarding Scale is a three-item, self-report inventory that was created for the present study by adapting from Ref. [91]. Higher scores reflect a higher level of digital hoarding for paid social Q&A. This measure was translated to Chinese and found to have good reliability and validity. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good construct validity (χ2/df = 2.16, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.94, and TLI = 0.95). In our study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.871.

3.2.9. Sensitivity to pain of payment

Tightwad-Spendthrift Scale [32] was used to measure sensitivity to pain of payment in this study. This scale comprises four items that measure respondents' spending habits on their usual shopping trips. The subjects were asked to complete the scale, based on their true feelings. A higher score on this scale indicates that the respondent experiences more pain of payment and is a tightwads (Cronbach's alpha = 0.852), this measure was translated to Chinese and found to have good reliability and validity. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good construct validity (χ2/df = 1.87, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.96, and TLI = 0.97). A lower score on this scale indicates that the respondent experiences less pain of payment and is a spendthrift (Cronbach's alpha = 0.844), this measure was translated to Chinese and found to have good reliability and validity. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good construct validity (χ2/df = 2.24, RMSEA = 0.08, CFI = 0.95, and TLI = 0.96).

3.2.10. Control variables

Several demographic variables are included in this study, because they will affect consumption decisions and willingness to pay. We controlled several variables, such as gender, age, education, monthly income, influence by COVID-19, mobile payment use and paid social Q&A form. These variables may affect the relationship among variables in this study.

4. Data analysis

SPSS 22.0 and Amos 26.0 were used for data analysis and testing. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were performed to confirm the validity of each item of the variables, and the reliability of each variable was measured using Cronbach's alpha. Six demographic variables were included in this study which are Gender, Age, Education, Monthly income, Influence by COVID-19 and Mobile payment use. After cleaning the data, the total numbers of respondents included in this study analysis were 863. We have tested the normality of the data, and the bivariate correlation of multiple comparisons has been corrected. Analyses revealed that there was no significant impact of these demographic variables on the main model variables.

4.1. Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 3 depicts the Mean, Standard Deviation and Correlations among the study variables. Usefulness (M = 3.263, SD = 0.424), easy of use (M = 3.348, SD = 0.336), professional (M = 4.114, SD = 0.517), value (M = 3.179, SD = 0.427), emotional contagion (M = 3.237, SD = 0.328), willingness to pay (M = 3.192, SD = 0.518), panic buying (M = 4.112, SD = 0.418), digital hoarding (M = 3.266, SD = 0.422), and sensitivity to pain of payment (M = 3.132, SD = 0.326). Correlation analysis showed that usefulness (r = 0.226, p < 0.001), easy of use (r = 0.139, p < 0.01), professional (r = 0.215, p < 0.01) and value (r = 0.187, p < 0.01) were significantly positively correlated with emotional contagion. Emotional contagion was significantly positively correlated with willingness to pay (r = 0.217, p < 0.05). Willingness to pay was significantly positively correlated with panic buying (r = 0.164, p < 0.05) and digital hoarding (r = 0.112, p < 0.05). The results above preliminary support the subsequent regression analysis.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among variables.

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-UF | 3.263 | 0.424 | – | |||||||

| 2-EU | 3.348 | 0.336 | 0.329*** | – | ||||||

| 3-PF | 4.114 | 0.517 | 0.238** | 0.321** | – | |||||

| 4-VL | 3.179 | 0.427 | 0.332** | 0.225*** | 0.234* | – | ||||

| 5-EC | 3.237 | 0.328 | 0.226*** | 0.139** | 0.215** | 0.187** | – | |||

| 6-WTP | 3.192 | 0.518 | 0.147*** | 0.224** | 0.112** | 0.145*** | 0.217* | – | ||

| 7-PB | 4.112 | 0.418 | 0.124* | 0.138*** | 0.126*** | 0.212** | 0.215** | 0.164* | – | |

| 8-DH | 3.266 | 0.422 | 0.136* | 0.213*** | 0.221*** | 0.138* | 0.124** | 0.112* | 0.109* | – |

| 9-SPP | 3.225 | 0.338 | −0.109 | 0.215* | 0.226** | 0.213 | 0.195 | 0.213 | 0.118* | −0.215* |

Note: N = 863, UF, Usefulness; EU, Easy of Use; PF, Professional; VL,Value; EC, Emotional Contagion; WTP, Willingness to Pay; PB, Panic Buying; DH, Digital Hoarding; SPP, Sensitivity to Pain of Payment.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The existence of common method bias in the data set was tested by using the Harman's one-factor test. The items of all eight factors (e.g., usefulness, easy of use, professional, value, emotional contagion, willingness to pay, panic buying, and digital hoarding) were all combined into a single factor and compared with that of the eight-factor model. The goodness of fit indices of the one-factor model (χ2 = 1776.32, df = 484, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.16, CFI = 0.65, TLI = 0.63, SRMR = 0.08) were significantly poorer than those of the eight-factor model (χ2 = 789.82, df = 475, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.05) suggesting that common method bias is not a serious concern in our data set. The test results show that the considered study items explained 28.33% of the variance when extracted as a single factor, less than the suggested threshold of 50% [92].

4.2. Confirmatory factor analysis

Data on paid social Q&A characteristics (usefulness, easy of use, professional, and value), emotional contagion, willingness to pay, panic buying, digital hoarding, and sensitivity to pain of payment were collected at one time, therefore it was necessary to conduct Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to compare different models. The fit of the nine-factor model was then compared with two alternative model. The seven-factor model (one in which usefulness was combined with easy of use, and professional was combined with value) was estimated in this study. Another model (six-factor) was also estimated, in which paid social Q&A characteristics (usefulness, easy of use, professional, and value) were combined on one factor, emotional contagion remained as a second factor, willingness to pay remained as a third factor, panic buying remained as a forth factor, digital hoarding remained as a fifth factor, and sensitivity to pain of payment remained as a sixth factor. The fit indices of these alternative models were weak compared to the nine-factor model, providing support for the distinctiveness of the model used in this study. CFA results revealed that nine factors structure provided a better fit (χ2 = 387, df = 198, CFI = 0.94, GFI = 0.92, IFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.05) as compared to the alternative models (see Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among variables.

| Model | χ2 | Df | CFI | GFI | IFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nine-factor model | 387 | 198 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Seven-factor model | 533 | 235 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Six-factor model | 552 | 238 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

4.3. Structural model

The model fit indices revealed that the model had a good fit with Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.93, Incremental Fit Index (IFI) = 0.92, and Standard Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.05, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.06.

The results of the structural model are presented in Fig. 2 . Usefulness (β = 0.227, p < 0.01), easy of use (β = 0.315, p < 0.01), professional (β = 0.118, p < 0.01), and value (β = 0.338, p < 0.001) all had positive influences on emotional contagion, thus supporting H1a, H1b, H2a, and H2b. Emotional contagion positively influenced willingness to pay (β = 0.219, p < 0.01), supporting H3. Willingness to pay were shown to have positive effects on panic buying (β = 0.125, p < 0.05) and digital hoarding (β = 0.119, p < 0.01), supporting H4a and H4b.

Fig. 2.

Structural analysis results. Note: Standardized coefficients. Numbers in parentheses are standard errors. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

In conclusion, this study identified usefulness, easy of use, professional and value as important characteristics that motivate consumers to be attracted by paid social Q&A. In addition, consumers’ emotions are susceptible to infection by these four characteristics of paid social Q&A, which also effectively increases their willingness to pay, and leads to digital hoarding and panic buying.

4.4. Moderation analysis

Analysis revealed (see Table 5 ) that control variables (e.g., gender, age, education, monthly income, and influence by COVID-19 and mobile payment use) did not explained any significant amount of variance in the willingness to pay (Step 1). Step 2 shows that the direct effect of emotional contagion was significant on willingness to pay (β = 0.427, p < 0.01). Step 3 shows the result of adding the interaction term (emotional contagion × sensitivity to pain of payment). As shown in Table 5 (step 3), the interactions (emotional contagion × sensitivity to pain of payment) was found significant for advertising attitudes (β = 0.125, p < 0.001). This analysis produced a significant main effect and a significant interaction effect (See Fig. 3 ).

Table 5.

Results for main effect and moderated regression analyses.

| Predictors | Willingness to Pay |

|

|---|---|---|

| β | ΔR2 | |

| Step1: | ||

| Control Variables | ||

| Gender | 0.013 | |

| Age | −0.042 | |

| Education | −0.083 | |

| Monthly Income | 0.052 | |

| Influence by COVID-19 | 0.114 | |

| Mobile Payment Use | 0.025 | |

| Step2: | ||

| Main Effects | ||

| Emotional Contagion | 0.427** | |

| Sensitivity to Pain of Payment | −0.068 | 0.285** |

| Step3: | ||

| Interaction Terms | ||

| Emotional Contagion × Sensitivity to Pain of Payment | 0.125*** | 0.018** |

Note: **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Fig. 3.

The Moderating effect of Sensitivity to Pain of Payment on the relationship between EC and WTP.

To further reveal the interaction effect, a simple slope test was performed. As shown in Fig. 3, the results show that when low sensitivity to pain of payment (Spendthrift) (below one standard deviation), the influence of emotional contagion (EC) on willingness to pay (WTP) decreases, and the positive relationship between emotional contagion (EC) and willingness to pay (WTP) is not significant (β = 0.26, ns.); When high sensitivity to pain of payment (Tightwad) (above one standard deviation), the positive relationship between emotional contagion (EC) and willingness to pay (WTP) is significant (β = 0.43, p < 0.001), that is, Tightwad is more sensitive to the changes of emotional contagion. Thus, those high in sensitivity to pain of payment (Tightwads) will show more positive willingness to pay toward paid social Q&A. H5 is supported.

5. Discussion and conclusion

5.1. Discussion

Firstly, results show that at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, the Usefulness (H1a) and Ease of Use (H1b) of information system quality characteristics positively affect user emotional contagion. At the same time, the Professional (H2a) and Value (H2b) of content quality characteristics positively affect user emotional contagion. This consequence means that the emotions of paid social Q&A users (including questioners, respondents and participants) can easily be transmitted to others on paid social Q&A platform which is highly useful and easy to use. Besides, emotional contagion can also easy to occur in paid social Q&A posts and communities with strong professional and valuable content. This results better confirm that the reason for the “resurgence” of paid social Q&A is not “COVID-19 boom”, the sharing mechanism [26] or the virtual scores incentive [24], but the information system quality characteristics and the content quality characteristics.

Secondly, results also show that user emotional contagion positively affect their willingness to pay (H3). The determination of H3 confirms the preconditions for willingness to pay of paid social Q&A users (including questioners, respondents and participants). At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, they inquired, communicated and interacted in paid social Q&A platforms, posts and communities. Emotions are transmitted and infected among users through the mechanism of language-mediated association and active perspective taking. Significantly different from the free social Q&A, “payment” is a necessary operation. Therefore, the stronger degree of emotional contagion in paid social Q&A user experience, the stronger degree of the willingness to pay he will possess. For example, at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, others' situation described by the language in social Q&A induces other users to imagine the same situation, thus causing the same emotional experience [46]. When seeing the warm and touching questions and answers related to COVID-19 in the social Q&A (like words encouraging active response to the epidemic), users can be easily moved; when seeing sad and tearful contents (like people die or separate affected by the epidemic), users can easily feel sympathy for the roles in the contents, so they are more willing to pay and participate in it. Our research also confirmed that users can “observe the world from others’ eyes” through paid social Q&A platform [47]. They can find that they are not alone through paid social Q&A as other people around the world are suffering from more arduous difficulties.

Thirdly, the hypotheses proposed in this study on the relationship between users’ willingness to pay for social Q&A services and panic buying (H4a) and digital hoarding (H4b) are also supported by the empirical results. Understanding the reasons for consumer panic buying and hoarding behaviors at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19 can be useful to reduce negative impacts, control escalation and ensure preparedness for future consumption behavior [61]. Our research results show that at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19 consumers not only panic buying or hoard physical products (like toilet paper, masks, antiseptic solution, rice, etc.), but also knowledge payment digital products. For example, during the period of COVID-19, 63.1% of Chinese consumers have purchased content products. The sales of paid social Q&A increase tremendously, which indirectly reflects that in a populous country, like in China, the economic and competitive pressure caused by COVID-19 have been further intensified. Emotions like fear and panic spread through various knowledge payment platforms. People are easily infected by the emotions of others. They are afraid of being laid off, so they generate the willingness to pay. They seek answers and helps by panic buying or hoarding social Q&A products to alleviate their fear and anxiety. Previous studies have shown that the panic buying behavior for physical goods is significantly stronger in wealthier geographical regions [14]. Unlike the supply chain shortage triggered by panic buying and hoarding for physical products, paid social Q&A products with its replicability rarely cause knowledge supply chain problems. We believe that during the epidemic, user panic buying and digital hoarding for paid social Q&A also have certain positive effects to some extent, which can help people better reduce their “fear of infection” and “fear of economic recession”, reduce their fear of death and unemployment, and even get improve their job security perception from the employment advice of paid social Q&A. However, the appropriateness of user panic buying and digital hoarding of social Q&A products is still worth to study further, as excessive panic buying and digital hoarding of knowledge paid products also do serious harm to user psychological resources.

Besides, consumers can generate pain of payment in the consumption process, which plays an important role in restraining consumption [54]. Specially, lower level of pain of payment may strengthen consumer willingness to pay [33]. Previous studies on pain of payment have confirmed that digital payment produces lower pain than cash payment, which makes consumer willingness to pay stronger, that is, “the less pain, the more buying” [85,87,88]. The results of this study confirm the moderating effect of sensitivity to pain of payment (tightwad vs. spendthrift) (H5). Compared with the spendthrift, the tightwad are more likely to be infected by the emotions of other users in paid social Q&A, and their willingness to pay is also stronger. That is to say, users who are more sensitive to pain of payment are more susceptible to emotional contagion and their willingness to pay for paid social Q&A are stronger. The analysis of moderating effect showed with the increase of emotional contagion degree, users who have high level of sensitivity to pain of payment, their willingness to pay will increase. However, with the increase of emotional contagion degree, users who have low level of sensitivity to pain of payment maintains, their willingness to pay unchanged. One of the possible reason is that at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, even in the same digital payment environment, users with high sensitivity to pain of payment are more easier to get emotional contagion and are more willing to pay, that is, “the more pain, the more buying”. Our results extend the theoretical boundary of the research on pain of payment in the digital payment environment to a certain extent (that is, expanding the research paradigm from “the less pain, the more buying” to “the more pain, the more buying”).

5.2. Conclusion

This study investigated the paid social Q&A characteristics (the usefulness, ease of use, professional and value) affect user willingness to pay through emotional contagion among platform users, and then lead to panic buying and digital hoarding at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19. The SOBC framework was used for theoretical analysis. Because it helps to link the stimulus factor–paid social Q&A characteristics (the usefulness, ease of use, professional and value) with user internal psychological processes, which is reflected in user willingness to pay of paid social Q&A and their further panic buying and digital hoarding behaviors. Specifically, by collecting and analyzing 863 survey data of Chinese users, five research conclusions are obtained in this study: (1) the stronger level of the usefulness and ease of use in the information system quality characteristics is, the stronger level of the emotional contagion the users suffer; (2) the stronger level of the Professional and Value the content quality characteristics is, the stronger level of the emotional contagion the users suffer; (3) user emotional contagion is positively related to the willingness to pay in paid social Q&A; (4) the stronger level of users' willingness to pay for social Q&A, the more likely trigger the users’ panic buying and digital hoarding; (5) The moderating analysis shows that sensitivity to pain of payment moderates the relationship between the emotional contagion received by users on paid social Q&A platforms and their willingness to pay. Compared with the spendthrift, the tightwad are more susceptible to emotional contagion, and their willingness to pay is stronger. Finally, gender, age, education, monthly income, influence by COVID-19 and mobile payment use have no confounding effect on dependent variables. Therefore, this study has theoretical and practical significance to some extent. We confirm the psychological mechanism of panic buying and digital hoarding of paid social Q&A services, which makes up for current literature gap. At the same time, our findings can help different users (tightwad vs. spendthrift) to evaluate and adjust their digital content consumption control ability in the face of disasters. Besides, our findings also helps digital content platform enterprises master the core needs of different types of users in the disaster situation, enhance user stickiness, and achieve sustainable development.

5.3. Theoretical contributions

This research makes some novelty and pioneer theoretical contributions to the research of panic buying of digital content products. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, it is more appropriate for us to study consumer panic buying behavior from the perspective of emotional contagion. At the same time, this study also broke through the limitation of existing researches, combining panic buying, digital hoarding, emotional contagion and the paid social Q&A characteristics. We find that there is a significant positive correlation between the characteristics of paid social question and answer and emotional contagion. At the same time, there is a significant positive correlation between emotional contagion and panic buying, while emotional contagion is also positively correlated with digital hoarding. The findings not only broaden the research scope of paid social Q&A characteristics and panic buying, but also further promote the development of research in the field of digital content consumption.

The first outstanding contribution in this research is to investigate the incentives of panic buying and digital hoarding behaviors for paid social Q&A products from the perspective of emotional contagion, which expands the scope of existing research. Base on the SOBC model, this study provides new evidence for the argument that consumers' emotional contagion can significantly influence their buying behavior, and expands the research on the antecedents of panic buying. We believe that the essence of this process of emotional infection through paid social Q&A platform is a digital emotional contagion. Digital emotional contagion should be understood as the mediated emotional contagion. As its intermediary, the goal of digital media companies is to expose individuals to stronger emotions with higher frequency [72], thus bringing more consumption. A previous survey evidence from Japan suggest that it has both bright and dark sides of social media usage during the COVID-19 [93]. Similar, will the sales promotion of the social Q&A products based on digital emotional contagion deepen the “involution” and cause more anxiety and psychological damage to users? Or will it help users resist the psychological stress caused by disasters such as COVID-19? These are still important issues worth exploring in academic circles and digital media companies. Our research provides an exploratory idea for further research.

Secondly, this study has important theoretical guidance for the practical application of the SOBC model in the paid social Q&A user group. The results show that the information system quality characteristics and the content quality characteristics of paid social Q&A can affect the probability of user emotional contagion, and trigger their willingness to pay, which in turn will cause panic buying and digital hoarding behaviors. This result not only expands the research of the influence brought by panic buying, but also further expands the study on the antecedents of emotional contagion. As billions of people were forced to stay at home at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, the number of users of paid social Q&A increased dramatically. In this unique environment, our research further confirms that the paid social Q&A characteristics play an important role in triggering consumer individual emotions and spreading group emotions.

Thirdly, this study firstly introduce the conception of sensitivity to pain of payment as the moderator in the field of paid social Q&A, and find that the positive relationship between emotional contagion and user willingness to pay for paid social Q&A is moderated by the sensitivity to pain of payment. The sensitivity to pain of payment provides a reference framework for distinguishing different consumer (tightwad vs. spendthrift) possibility of emotional contagion at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19 and their ability of consumption control when facing panic situations (whether panic buying and digital hoarding will occur). The conclusion enriches the coping mechanism to prevent panic buying and digital hoarding.

Finally, different from previous studies on panic buying for consumer general daily necessities at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, we explore the impact of paid social Q&A products on panic buying and digital hoarding through the digital content industries. We believe that user panic buying and digital hoarding behaviors for social Q&A also has certain positive effects, which can help people better reduce their “fear of infection” and “fear of economic recession”, reduce their fear of death and unemployment, and improve their sense of job security. However, the appropriateness of user panic buying and digital hoarding of social Q&A services is still a problem worthy for deeper study.

5.4. Managerial implications

The COVID-19 has caused great obstacles to the global economy, resulting in serious economic recession, companies and industries closing and unemployment rate rising [94]. Therefore, the current research on panic buying is of great value for current global marketing and enterprise decision-making [95]. Reviewing previous studies, digital content payment has become a new consumption trend in China especially in recent years. The results of the study have important practical significance for corporate decision makers, marketing managers of the social Q&A platform, consumers, media and government departments.

Firstly, this study shows that the paid social Q&A characteristics are positively related to emotional contagion. Emotional contagion can easily trigger user willingness to pay, and ultimately lead to panic buying and digital hoarding. Therefore, it is necessary for the enterprise decision makers and marketing managers of the social Q&A platform to understand the emotional perception and needs of users at the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, deeply cultivate high-quality and healthy content, prevent false news and bad advertising, reduce the spread of panic emotions, and guide consumers to consume rationally, so as to effectively improve the development performance of the paid social Q&A products. Secondly, this study also obtained an interesting but very important finding: sensitivity to pain of payment moderates the relationship between emotional contagion and willingness to pay. Users with higher level of sensitivity to pain of payment are more vulnerable to emotional contagion, stimulate their willingness to pay, and eventually trigger panic buying and digital hoarding. At the current stage of coexistence with COVID-19, even in the same digital payment environment, user sensitivity to pain of payment is different. Users with stronger level of pain of payment (the tightwad) are more likely to get emotional contagion through paid social Q&A, and are more likely to generate their willingness to pay, that is, “the more pain, the more buying”. In this sense, the sensitivity to pain of payment promotes the consumption behavior of digital content to a certain extent. This interesting discovery is a new interpretation of the traditional research viewpoint that “pain payment can inhibit consumer behavior” [54] under the background of Internet. Finally, paid social Q&A platform enterprises and government departments can take some stabilization measures to reduce panic, which may effectively reduce user panic buying and digital hoarding behaviors.

5.5. Limitation and future research