Abstract

Background:

Defects in energetics are thought to be central to the pathophysiology of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), yet the determinants of ATP availability are not known. The purpose of this study is to ascertain the nature and extent of metabolic reprogramming in human HCM, and its potential impact on contractile function.

Methods:

We conducted proteomic and targeted, quantitative metabolomic analyses on heart tissue from patients with HCM and from non-failing control human hearts.

Results:

In the proteomic analysis, the greatest differences observed in HCM samples compared to controls were increased abundances of extracellular matrix and intermediate filament proteins, and decreased abundances of muscle creatine kinase and mitochondrial proteins involved in fatty acid oxidation. These differences in protein abundance were coupled with marked reductions in acyl carnitines, byproducts of fatty acid oxidation, in HCM samples. Conversely, the ketone body 3-hydroxybutyrate, branched chain amino acids, and their breakdown products, were all significantly increased in HCM hearts. ATP content, phosphocreatine, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and its phosphate derivatives, NADP and NADPH, and acetyl CoA were also severely reduced in HCM compared to control hearts. Functional assays performed on human skinned myocardial fibers demonstrated that the magnitude of observed reduction in ATP content in the HCM samples would be expected to decrease the rate of cross-bridge detachment. Moreover, left atrial size, an indicator of diastolic compliance, was inversely correlated with ATP content in hearts from patients with HCM.

Conclusions:

HCM hearts display profound deficits in nucleotide availability with markedly reduced capacity for fatty acid oxidation, and increases in ketone bodies and branched chain amino acids. These results have important therapeutic implications for the future design of metabolic modulators to treat HCM.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy, hypertrophy, metabolism, proteomics, translational studies

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) affects 1 in 500 people, making it the most common genetic cardiovascular condition of Mendelian inheritance.1 Patients with HCM experience a progressive disease course and many suffer serious adverse events including heart failure, arrhythmias, and early mortality.2 The sarcomere is the primary locus of HCM variants, with 40–50% of patients with HCM carrying pathogenic variants in one of eight genes coding for sarcomere proteins.3 A limited number of non-sarcomere genes with an established strong association with HCM collectively make up a small fraction of cases,4, 5 with the remainder being classified as “genotype negative” HCM. A large proportion of this latter category are increasingly being recognized as polygenic with modifying environmental factors.6 Despite the diverse monogenic and polygenic causes of HCM, there is considerable overlap in the phenotypic manifestations and clinical outcomes.2

Over the past three decades, there has been an enormous effort by basic and translational scientists to understand the molecular events that lead to HCM. While genetic cellular and animal models have yielded highly valuable insights into disease pathogenesis, these models do not always faithfully recapitulate features of human HCM. A number of studies using septal myectomy specimens from patients with HCM have identified increased myofilament calcium sensitivity,7 increased actomyosin ATPase activity,8 calcium dyshomeostasis,9 protein quality control abnormalities,10 and multiple differences in protein abundance11–13 when compared to control hearts. While some disease-related aberrations are more pronounced, or in some cases specific to sarcomeric HCM, many appear to be genotype-independent and thus may represent shared downstream pathways related to secondary cardiac remodeling.

Impaired cardiac energetics is one shared downstream pathway that is believed to be central to HCM pathophysiology.14, 15 Energetic defects have been long been recognized in genetic mouse models of HCM,16, 17 as well as in patients,18, 19 with significant reductions in energy reserve reflected by a decreased ratio of phosphocreatine (PCr) to adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In patients with HCM, a lower PCr:ATP ratio is associated with progression of cardiac fibrosis as measured by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.20 This reduction in energy stores has been postulated to relate to increased ATP consumption at the sarcomere,21, 22 but emerging data suggest that the ability of HCM hearts to generate ATP may also be impaired. Dysregulation of specific enzymes involved in cardiac metabolism has recently been described in HCM.11, 13 In particular, reduced abundances of enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation and a reduction in the abundance of acyl carnitines in human HCM suggest a metabolic “shift” away from fatty acids as the primary fuel source of the normal heart.11, 23 A similar shift in substrate utilization has been demonstrated in experimental models of pathologic cardiac hypertrophy.24 In the healthy heart, β-oxidation of fatty acids produces the majority of acetyl-CoA that feeds into the TCA cycle to generate ATP.25 In conditions of chronic myocardial stress that lead to heart failure, metabolic reprogramming of myocardial fuel utilization from free fatty acids to glycolysis occurs likely as an initially adaptive mechanism to reduce the consumption of oxygen. But over time, it is believed that this shift results in insufficient ATP production to meet the energetic demands of the heart, thus contributing to the pathogenesis of myocardial dysfunction. 25, 26 Whether adaptive changes can be elicited in response to this metabolic re-programming is uncertain. Further, it is not clear whether the magnitude by which ATP is reduced in HCM would limit cross bridge dynamics, such that it could contribute in a causal way to disease pathophysiology.

With these knowledge gaps in mind, we conducted paired proteomic and metabolomic analyses of heart samples obtained from patients with HCM with defined genotypes undergoing septal myectomy, and compared the results from septal samples from non-failing control human hearts. The proteomic analyses revealed an upregulation of extracellular matrix proteins and intermediate filament / Z-disc proteins, and downregulation of inner mitochondrial membrane proteins, as well as muscle creatine kinase, in all of the HCM samples compared to control samples, independent of patient genotype.11, 13 Quantitative targeted metabolomics analysis revealed marked reductions in fatty acids in all HCM groups compared to control samples, particularly long chain acyl carnitines. Conversely, the ketone body 3-hydroxybutyrate, lactate, and the 3 branched chain amino acids, were all significantly increased in HCM samples. ATP and other trinucleotides, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and its phosphate derivatives, NADP and NADPH, were also severely reduced in HCM hearts. Using a human skinned myocardial fiber assay, we demonstrate that the magnitude of observed reduction in ATP content in the HCM hearts would be expected to decrease the rate of cross-bridge detachment, implying a direct effect of ATP availability on myofilament function that could contribute to impaired relaxation. Moreover, cardiac ATP content was inversely correlated with left atrial size, suggesting a relationship between ATP content and the magnitude of diastolic dysfunction.

Methods

The authors are committed to make the data, methods used in these analyses, and materials used to conduct research available to any researcher for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedures.

Patient sample acquisition.

Myocardial tissue was obtained from the interventricular septum of unrelated subjects with HCM at the time of surgical myectomy for symptomatic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction at the University of Michigan as described previously.9 The hearts are perfused with blood cardioplegia at 4 degrees Celsius. Control donor hearts were identified through a research protocol with Gift of Life and all had normal systolic function and minimal to no hypertrophy. Donor hearts were perfused with HTK-enriched (histidine, tryptophan, and ketogluterate) cardioplegia solution at 4 degrees Celsius before removal, and tissue was snap-frozen in liquid N2 in the operating room immediately upon explantation. A portion of each septal sample was used for these studies. This study had the approval of the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board, and subjects gave informed consent. See expanded methods and materials in the online supplemental materials.

For the functional assays, epicardial biopsies were obtained from patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting at the University of Vermont Medical Center. A ~10–30 mg piece of muscle was excised from the left ventricular free wall and immediately submerged in oxygenated ice-cold Krebs buffer containing 30 mM, 2,3-butanedione monoxine.27 These procedures were in accordance with the human subjects protocol approved by the Internal Review Board of the University of Vermont Medical Center and all patients gave informed consent.

Sample preparation for proteomic analyses.

A small portion (1–2 mg) of each frozen heart biopsy was digested to peptides with trypsin and processed as described.28 See online supplemental materials.

Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LCMS) for proteomic analyses.

The tryptic peptides were separated by liquid chromatography and directly infused into a mass spectrometer for identification and quantification of peptide abundances as described.28 Data were collected in data dependent MS/MS mode with the top five most abundant ions being selected for fragmentation and record as Thermo.raw files as previously described.28 See online supplemental materials.

Quantification of protein abundances.

Protein abundances were determined from the LCMS analyses using a label-free quantification routine from the top 5 ionizing peptides for each protein as described.28 See online supplemental materials.

Statistical analysis of proteomic data.

Protein abundances between groups were compared. To correct for the non-linear distribution in the normalized peptide abundances caused by large differences in the intrinsic ionization efficiencies of each peptide, the values were transformed using the natural log. The natural log transformation produces a normal distribution which was then subjected to a Student’s t-tests.

Unpaired student’s t-tests were performed in Excel (Microsoft) on array of natural log abundances from all peptides for a given protein in the HCM samples versus control (donor) accounting for both intra- and inter-group variability. Unpaired student’s t-test were run on the large array of the natural log normalized abundances from all peptides in all the proteins within each subcellular compartment to determine if related proteins differed significantly between the HCM groups and the donor control (e.g. testing if mitochondrial content was significantly reduced in the HCM groups).

The pooled standard deviation of each average protein ratio was calculated using a Taylor Expansion to the standard deviation for each grouped peptide ratio. That grouped peptide ratio standard deviation was pooled into a grouped protein ratio standard deviation by accounting for the degrees of freedom within each group. The standard error of the mean (SEM) was then calculated by dividing the pooled standard deviation by the square root of the number of samples within both the HCM and control groups. The SEM reflects both inter- and intra-group variability. A Bonferroni correction was performed to account for multiple comparisons (0.05/527 = 0.000095), and a P value of ≤ 0.0001 was considered statistically significant.

Quantitative targeted LCMS metabolomics.

About 100 mg of each frozen heart sample was lyophilized overnight, powdered, and weighed to make homogenates for each targeted LCMS metabolomics assay (acylcarnitines, amino acids, organic acids, nucleotides, and malonyl and acetyl CoA). Metabolites were extracted in cold aqueous/organic solvent mixtures according to validated, optimized protocols.29, 30 See online supplemental materials.

Statistical analysis of metabolomic data and correlation analyses.

Statistical analysis and visualizations for the metabolomics data were performed using R 4.0.3. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for the comparison between two experimental groups. For experiments with more than 2 groups, an ANOVA was performed using the aov R function. Post-hoc testing of significant results was performed using Tukey’s HSD test. PCA analysis was performed using the FactoMineR R package and visualized using the factoextra R package. Heatmaps were creating using the Complexheatmap R package. Correlation analyses were performed in R using the cor.test function and the Spearman Rank Sum non-parametric method. P values were adjusted for multiple test correction using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

Estimation of ATP concentration in vivo.

To estimate the concentration of ATP available for actomyosin cross-bridge cycling (i.e. contractility), the abundance of ATP measured per gram of lyophilized heart powder was converted to a concentration. The dry weights of the lyophilized powered were assumed to be 20% of the total mass of the samples 31, 32 and each gram of water was assumed to occupy 1 mL of the tissue. Only 60% of this concentration was assumed to be available for actomyosin cross-bridge cycling based on previous estimates of ATP usage in cardiac muscle.33

Determination of the effect of ATP on actomyosin cross-bridge detachment in skinned human epicardial tissue.

To determine the effect of ATP on actomyosin cross bridge detachment, as a proxy for muscle relaxation, the myocardial biopsies were skinned, subject to a range of ATP concentrations and mechanics were measured. The samples were bathed in a mild detergent, 0.1% Triton X-100, to remove lipid membranes from the myocytes, and sculpted to cylindrical shape of at least 500 micron length and 140–200 micron diameter. The samples were attached to aluminum clips, placed between a length motor and force transducer, and stretched to 2.2 micron sarcomere length. The myofilaments were then activated with increasing concentrations of Ca2+ in the presence of magnesium ATP (MgATP) over a 0.01 to 5.0 mM range. A double-exponential function was fitted to the change in recorded tension, in response to the quick stretch, to characterize the rate of tension release (krel), which corresponds to the rate of myosin cross-bridge detachment.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical data.

Heart donors and patients with HCM across the 3 genotype groups (Genotype negative, myosin binding protein C (MYBPC3), or beta-myosin (MYH7) variants) were well matched for age and sex (Table 1, Table S1). Most of the samples came from patients of white race. Eleven percent of patients with HCM were diabetic. Mean maximal wall thickness, left ventricular outflow tract gradient, and left atrial size were similar among the 3 HCM groups. Mean ejection fraction was higher in the HCM-MYBPC3 and HCM-MYH7 patients compared to the donors. All patients were symptomatic prior to myectomy (New York Heart Association Class II or III), with more MYH7 variant carriers being Class III. All patients were receiving either a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker at the time of myectomy, with 4 patients in the HCM-MYH7 group being on both medications.

Table 1 –

Patient Demographics and Clinical Data

| Non-failing (n=8) | HCM – No sarcomere variants (n=12) | HCM - MYBPC3 (n=19) | HCM - MYH7 (n=10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52 ± 6 | 53 ± 3 | 42 ± 3 | 46 ± 4 |

| Sex (% male) | 37.5 | 50 | 37 | 60 |

| Race (% White) | 87.5 | 100 | 89 | 90 |

| Body mass index | - | 34 ± 2 | 33 ± 2 | 31 ± 2 |

| Diabetes (% yes) | 0 | 17 | 16 | 0 |

| Maximal wall thickness (mm) | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 19.5 ± 1.3 | 23.3 ± 1.2 | 22 ± 1.6 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 64 ± 1.6 | 67 ± 1.7 | 70 ± 1.4 | 75 ± 1.0 |

| Maximal LVOT gradient (mmHg) | - | 98 ± 15 | 97 ± 9 | 111 ± 10 |

| Left atrial diameter (mm) | - | 43.4 ± 0.7 | 49.6 ± 1.5 | 49.6 ± 1.9 |

| NYHA Class (% Class III) | 0 | 42 | 37 | 80 |

| Beta blockers (%) | 0 | 75 | 79 | 80 |

| Calcium channel blockers (%) | 0 | 25 | 21 | 40 |

HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, LVOT = left ventricular outflow tract, NYHA = New York Heart Association. 4 patients in the HCM-MYH7 group were taking both beta blockers and calcium channel blockers.

Proteomic profiling revealed marked differences in abundance of proteins involved in contractility, the extracellular matrix, and energy metabolism in HCM compared to control hearts.

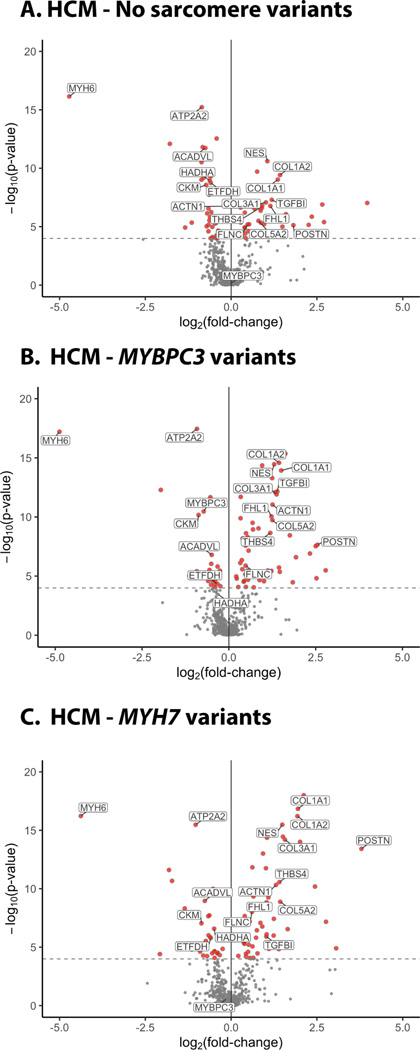

A total of 509 proteins were identified in all samples from control and HCM hearts (Table S2). After adjusting for multiple comparisons, a statistically significant difference (P<0.0001) was found for 88 proteins in at least one HCM group and 57 proteins in all 3 HCM groups compared to control hearts (Figure 1). Differences in protein abundance between the HCM and control groups were largely independent of genotype.

Figure 1. Volcano plots summarizing findings from proteomics analysis of human HCM and control hearts.

Proteins with increased (+ log) or decreased abundance (- log) are shown as a function of fold change over control hearts for HCM samples with (A) no sarcomere variants, (B) MYBPC3 variants, and (C) MYH7 variants. Proteins that were significantly different from control, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (P<0.0001), are shown in red and a subset of the individual proteins are labeled. N=6 controls, 18 HCM-MYBPC3, 9 HCM-MYH7, and 12 HCM - No sarcomere variant.

Several sarcomere contractile proteins were differentially expressed in HCM compared to control hearts. Most notabe was a 40% reduction in myosin-binding protein C in samples from patients with truncating MYBPC3 variants, as we have shown previously. 28 The other differences in sarcomeric proteins did not amount to large changes in the proteome. For example, abundance of the alpha-myosin isoform (MYH6) was 96% lower in HCM hearts. However, the alpha-myosin isoform comprises only ~2% of total myosin in control hearts and 0.02% in HCM hearts, as the beta isoform (MYH7) is the predominant isoform expressed.

Several Z-disc, intermediate filament, and cytoskeletal proteins were upregulated 1.2 – 2.8-fold in HCM samples compared to controls, including the skeletal isoform of alpha-actinin (ACTN1), four and a half LIM domains protein 1 (FHL1), synaptopodin 2 (SYNPO2L), nestin (NES), filamin C (FLNC), vinculin (VCL), phosphoglucomutase (PGM5), and obscurin (OBSCN). Several extracellular matrix proteins were increased 1.5 – 5.4-fold in HCM samples compared to controls, including type 1, 5 and 6 collagens, fibronectin (FN1), thrombospondin 4 (THBS4), biglycan (BGN), versican (VCAN), and lumican (LUM). Cardiac fibroblast proteins established as important mediators of cardiac fibrosis were also more highly abundant in HCM compared to control hearts, including transforming growth factor 1 (TGFB1, 2.3 – 2.6-fold) and periostin (POSTN, 3.5 – 13.9-fold).34

Other major differences in protein abundances between HCM and control samples included reductions in several mitochondrial proteins and in proteins involved in cardiac fuel metabolism and energetics. Among these were enzymes catalyzing key steps in long chain fatty acid beta-oxidation, including very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (ACADVL) and hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (HADHA), and electron transport, flavoprotein dehydrogenase (ETFDH). In addition, there was a 43% reduction in creatine-kinase M-type, an enzyme involved in energy transduction, suggesting the potential for impairment in ATP generation in HCM hearts. A major consumer of ATP, the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium transport protein 2 (ATP2A2) the encodes SERCA2a, was also significantly reduced in HCM samples.

Quantitative, targeted metabolomic analysis reveals marked reduction of fatty acid derivatives and ATP, increased ketone bodies, and increased branched chain amino acids in HCM samples.

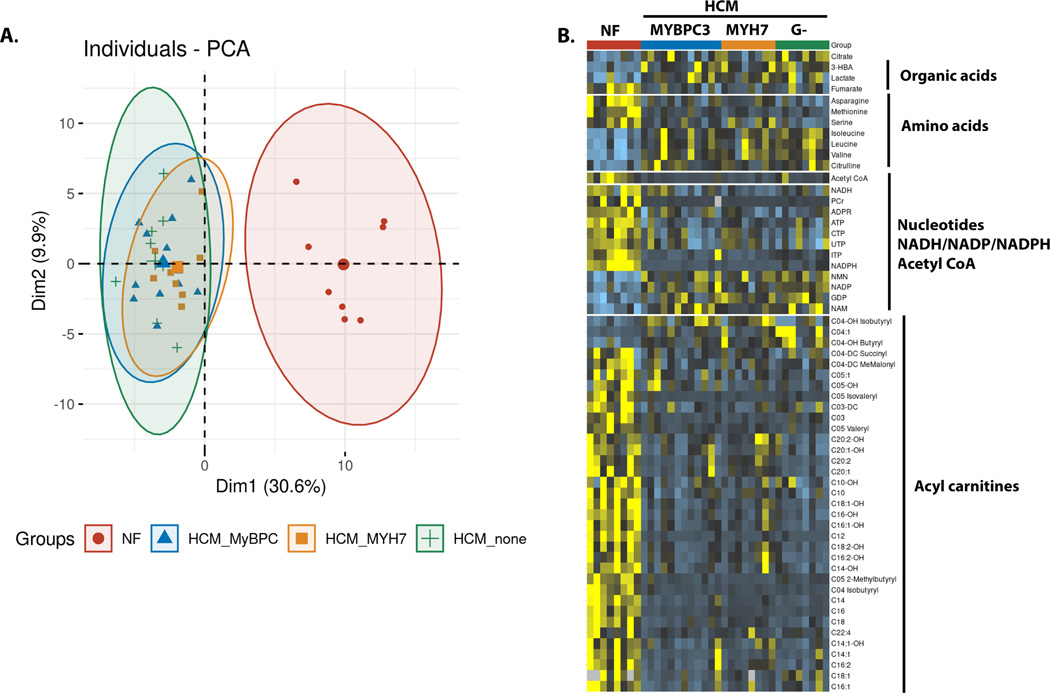

Given the lower abundance of multiple proteins involved in fuel and energy homeostasis in HCM samples, we sought to investigate metabolite pool sizes to determine whether the proteomic changes impacted metabolic availability. Using a targeted quantitative metabolomics platform, we identified a total of 104 metabolites, of which 59 significantly differed between at least one of the HCM groups compared to control samples after applying a false discovery rate adjustment (Table S3). A principal component analysis scree plot showed that the first component accounted for most of the variability in metabolite abundance (Figure S1). This first principal component was defined by disease status, and demonstrated overlapping clusters of the HCM groups, which were completely distinct from the control group (Figure 2A). Metabolite abundance was independent of genotype, sex, and age (Figure S2). There were no differences between diabetic (n=3) and non-diabetic (n=25) hearts.

Figure 2. Metabolomic analysis of HCM and control hearts.

(A) PCA plot showing the overall distinction between the control hearts and the 3 HCM groups. The 3 HCM groups overlap with each other with more variability in the HCM – no sarcomere variant group. (B) Heat map showing the individual metabolites that were significantly different in the HCM compared to the control heart samples after adjustment by false discovery rate. N=8 for controls, HCM- MYH7, HCM-no sarcomere variant and N=12 for HCM-MYBCP3.

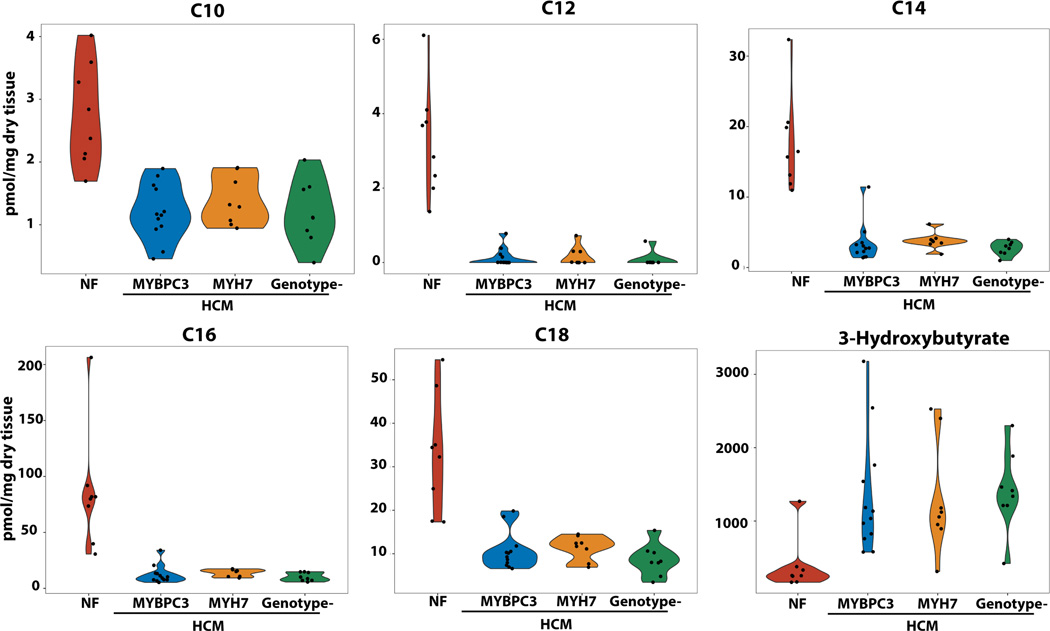

The most striking difference in individual metabolites was the uniform reduction in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation intermediates in HCM samples compared to control samples, particularly long-chain acyl carnitines which were reduced ~70–95% (Figure 2B and 3). The expression of the enzymes involved in long chain fatty acid oxidation, ACADVL, HADHA and ACAA2, were positively correlated with several long chain acyl carnitines (Table S4).

Figure 3. Metabolomic analysis showing representative abundances of long-chain acyl-carnitines and ketone bodies in HCM and control hearts.

Abundances of C10, C12, C14, C16 and C18 were markedly and uniformly depleted in all HCM groups, independent of genotype, compared to control hearts. Ketone bodies were increased in abundance across all 3 HCM groups. ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc comparison were used to compare groups with P<0.0001 for all comparisons of HCM groups to control. N=8 for controls, HCM- MYH7, HCM-no sarcomere variant and N=12 for HCM-MYBCP3.

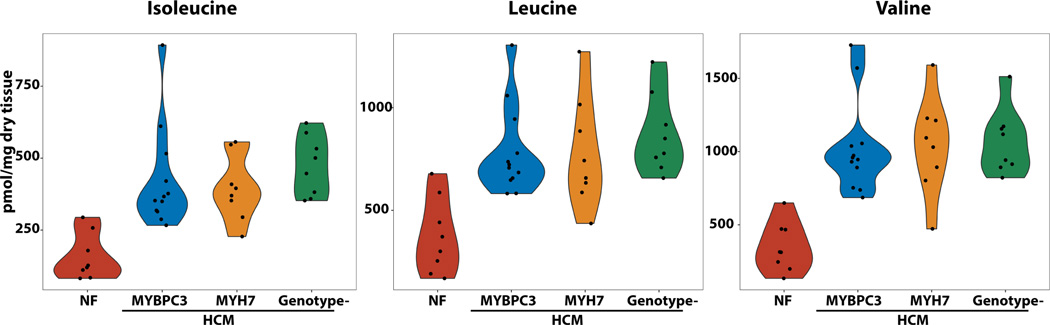

Conversely, the ketone body 3-hydroxybutyrate, lactate, and the 3 branched chain amino acids (BCAAs = leucine, isoleucine and valine) were all significantly increased in HCM hearts (Figure 2B, Figure 3 and 4). The protein expression of BDH1, which catalyzes the interconversion of beta-hydroxybutyrate to acetoacetate, and OXCT1, which catalyzes the reversible transfer of coenzyme A from succinyl-CoA to acetoacetate, were modestly decreased and increased respectively (P<0.05, Supplemental Table 2). While the net effects of these differences is difficult to predict, elevation of a breakdown product of ketones, C04-OH Butyryl, in HCM compared to control samples suggests an increase in ketone oxidation. Interestingly, protein expression of enzymes of long chain fatty acid oxidation were negatively correlated with levels of C04-OH Butyryl (Table S4), suggesting that increased ketone oxidation could be an adaptive response to decreased flux through the fatty acid oxidation pathway. For the BCAAs, several enzymes involved in their catabolism (BCAT2, HIBADH and MCCC2) were decreased in abundance (P<0.05 across all groups), suggesting accumulation of BCAAs due to defective catabolism. However, a breakdown carnitine product for valine, C04-OH Isobutyryl, was elevated in HCM hearts suggesting increased utilization of BCAAs for fuel metabolism.

Figure 4. Metabolomic analysis showing increased abundance of branched chain amino acids in the hearts of patients with HCM compared to controls.

N=8 for controls, HCM- MYH7, HCM-no sarcomere variant and N=12 for HCM-MYBCP3. P<0.0001 for all comparisons of HCM to control hearts.

Most TCA cycle intermediates were not different among the groups, except for an increase in citrate and decrease in fumarate in the HCM compared to control hearts (Figure 2B, Table S3). Of the non-BCAA amino acids, asparagine, methionine and serine were reduced and citrulline was increased in HCM compared to control hearts.

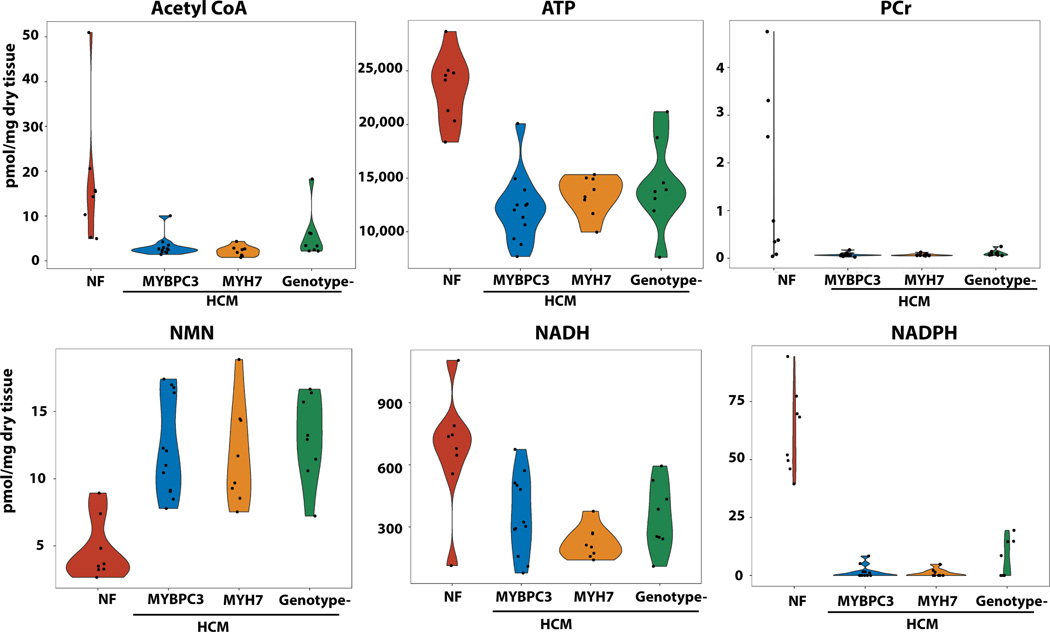

The trinucleotides ATP, CTP, and UTP were all markedly reduced in abundance in HCM samples compared to controls (Figure 2B, Figure 5, Table S3). Phosphocreatine levels were dramatically reduced by >90% in all HCM groups compared to controls (Figure 5). Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and its phosphate derivatives, NADP and NADPH, were also significantly reduced, while their precursors, nicotinamide (NAM) and NAM mononucleotide (NMN), were increased in HCM hearts. Acetyl CoA, the central molecule that delivers acetyl groups to the citric acid cycle to be oxidized for ATP production, was markedly reduced in HCM hearts. Together, this metabolomic analysis suggests a shift in substrate availability with marked reductions in fatty acids and increases in ketone bodies, BCAA, and their respective breakdown products.

Figure 5. Metabolomic analysis showing reductions of acetyl CoA, trinucleotides, NADH and NADPH with increased abundance of NMN, the precursor of NAD in HCM samples compared to controls.

N=8 for controls, HCM- MYH7, HCM-no sarcomere variant and N=12 for HCM-MYBCP3. P<0.0001 for all comparisons of HCM to control samples.

ATP-dependent cross-bridge detachment in skinned human cardiac muscle.

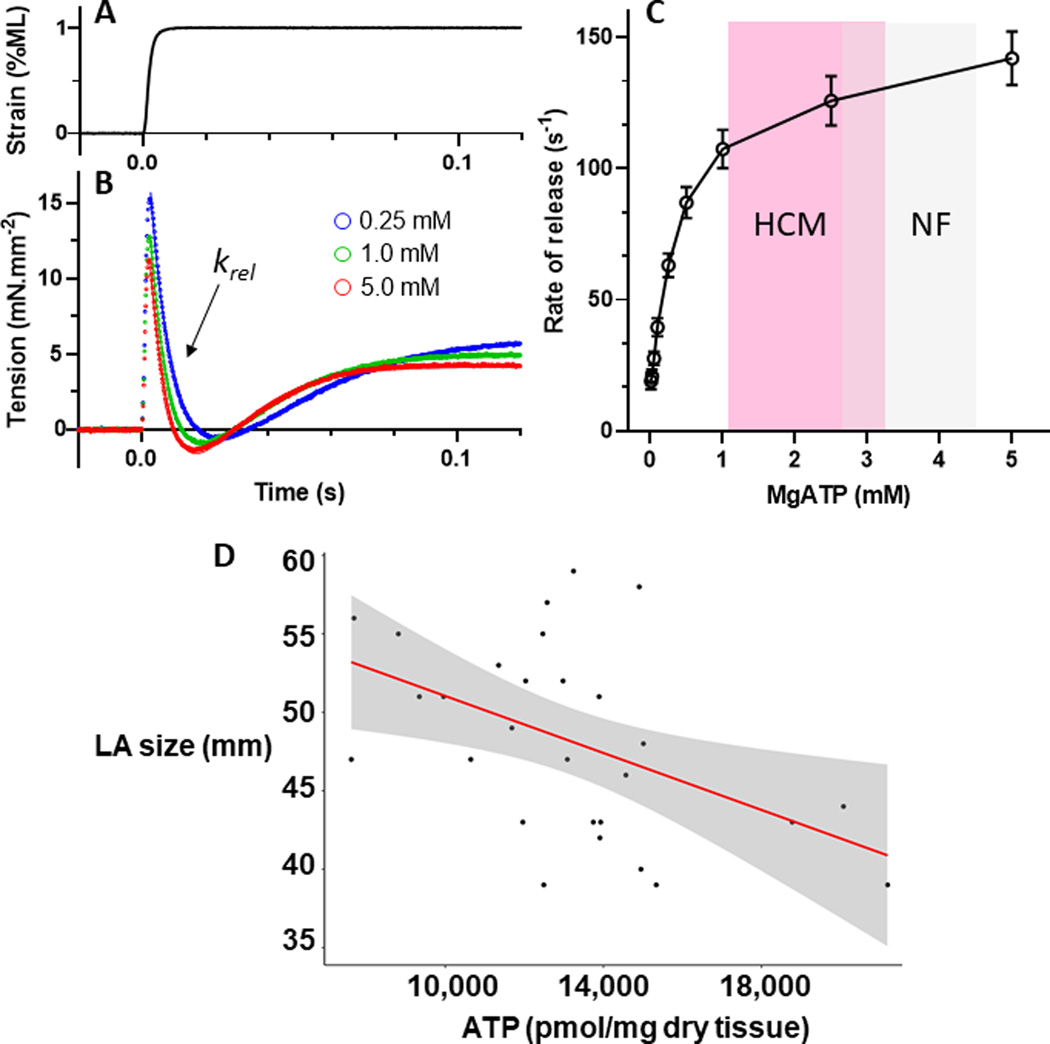

In order to determine whether the difference in ATP content between HCM and control samples could impact cardiac mechanics, we measured the kinetics of cross-bridge detachment in skinned human cardiac fibers as a function of ATP (Figure 6). The application of a quick 1% stretch in muscle length (Figure 6A) at maximal Ca2+-activation conditions (pCa 4.8) resulted in a rapid increase in tension, followed by a slower decrease as the myosin cross-bridges detached from the actin filament (Figure 6B). The rate of the cross-bridge release (krel) was slowed as the ATP concentration was diminished over the range of 0.01 mM to 5 mM (Figure 6C). Contrasting the mean and range of values for ATP content in HCM and control samples, the reduction in ATP content in the HCM hearts is expected to result in a ~10% decrease in the rate of cross-bridge detachment when compared to control hearts.

Figure 6. Rate of myosin cross-bridge detachment slows at lower MgATP concentrations.

A. A quick stretch of 1% muscle length (ML) was applied to demembranated epicardial muscle that had been biopsied from patients undergoing coronary bypass grafting. B. The recorded tension response (solid lines) at maximum Ca2+-activation was fit to the double-exponential function (dotted lines). The rate of myosin crossbridge detachment is reflected in the rate of tension release (krel) immediately following the stretch. C. Lower concentrations of MgATP resulted in slower krel and would be expected to reduce relaxation function in the cardiac cycle during transition from late systole to early diastole. Mean ± SEM, n=32 samples from 14 patients. D. Inverse correlation between left atrial diameter (mm) and the content of ATP in the corresponding heart tissue for each patient. Correlation analysis was performed using the Spearman rank sum non-parametric test, yielding a r of −0.47, P=0.01. N=40 individual values.

Correlation between ATP levels and diastolic dysfunction in patients.

Left atrial size, a sensitive indicator of the magnitude of diastolic dysfunction and marker of prognosis in patients with HCM,35 was measured from echocardiograms performed just prior to each patient’s myectomy. Left atrial size was inversely correlated with the content of ATP in each corresponding patient’s heart sample (Figure 6D), suggesting a relationship between ATP availability and whole heart diastolic dysfunction.

Discussion

Our comprehensive proteomic analysis of heart tissue from patients with HCM demonstrated an increased abundance of extracellular matrix proteins and mediators of cardiac fibrosis, consistent with prior studies.11, 13 We also observed increased abundance of multiple Z-disc and intermediate filament proteins in HCM heart samples as compared to the controls. Many of these proteins have well-established roles in sensing biomechanical stress, signal transduction, and myofibrillar repair and stabilization.36, 37 An increase in the abundance of such proteins may be an adaptive response to increased mechanical stress.38

In pairing the proteomic and metabolomic analyses, we identified reductions in cardiac proteins that were linked with metabolic changes in heart samples obtained from patients with HCM compared to those from control samples. Importantly, these defects were independent of genotype, age or sex. The energetic deficit in HCM is thought to relate in part to increased ATP consumption at the sarcomere due to increased myofilament calcium sensitivity and/or a reduced number of cross-bridges in the super relaxed state as a fundamental consequence of pathogenic sarcomere variants.21, 22 This long-standing paradigm is supported by findings of reduced PCr:ATP ratios and myocardial efficiency in gene variants carriers even prior to the development of overt hypertrophy.18 However, primary deficits in ATP generation may also contribute to decreased energetic capacity. In this study, we observed a 43% reduction in creatine-kinase M-type, which catalyzes the reversible transfer of a phosphate moiety between PCr and MgADP to generate ATP.39 There is strong experimental evidence that rigor tension is tightly linked to myofibrillar bound CK which compartmentalizes adenine nucleotides for utilization by myosin ATPase.39, 40 Therefore, the marked reductions in CK, PCr and ATP would be predicted to cause a rise in diastolic tension based on published literature. Our own data examining the kinetics of cross bridge detachment in human skinned cardiac fibers as a function of ATP concentration would support this prediction. The finding that left atrial size inversely correlates with the content of ATP in corresponding heart tissue provides an additional link between ATP availability and diastolic dysfunction in HCM.

We observed a marked reduction in the abundance of proteins involved in β-oxidation of fatty acids and in the content of acyl carnitines in hearts from patients with HCM compared to control hearts. These findings are highly reminiscent of those from explanted hearts from patients with end-stage heart failure with reduced ejection fraction,41 and are in agreement with findings from a recently published study in human HCM.23 We also observed increased levels of lactate, the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate, and the 3 branched chain amino acids in HCM hearts, similar to human failing hearts.42, 43 These findings diverged from those by Ranjbarvaziri et al in which lactate and BCAAs did not differ between HCM and control hearts, and ketone bodies were not reported.23 The fact that the metabolic signature of HCM is so similar to end-stage heart failure in terms of the direction and magnitude of change would not have been anticipated from experimental data, where no differences in metabolite levels were observed in the setting of pathologic hypertrophy in the absence of LV dysfunction or heart failure.24 Patients with HCM undergoing myectomy, while symptomatic from left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, are typically well compensated and have normal to increased left ventricular ejection fractions. The surprising similarities between the metabolic profiles of HCM and more advanced heart failure therefore suggest that these metabolic changes occur relatively early, and represent a canonical response to different forms of pathologic stress and remodeling, independent of the inciting trigger. Recently it has been shown that reduced flux through the fatty acid oxidation pathway and increased glucose utilization is necessary for cardiac hypertrophic growth.44 Therefore, therapies aimed at restoring these metabolic defects have the potential to prevent or attenuate adverse cardiac hypertrophic remodeling and could have widespread benefit across a spectrum of cardiomyopathies.

The marked metabolic shift in substrate availability in human HCM has important therapeutic implications. Metabolic modulation is an attractive strategy because energy deprivation is considered likely to contribute directly to the pathophysiology of HCM. Indeed, our studies using skinned human cardiac trabeculae suggest that having limited levels of ATP as measured in HCM samples could contribute directly to diastolic dysfunction by decreasing the rate of actomyosin cross-bridge attachment. Moreover, left atrial size inversely correlated with ATP content in corresponding hearts. Since these metabolic defects were common across all genotypic forms of HCM, the therapeutic benefit of metabolic modulation would also be expected to be generalizable. Perhexiline was the first metabolic modulator to be tested in a clinical trial of patients with HCM.45 Perhexiline is an inhibitor of CPT1, which transports fatty acids across the outer mitochondrial membrane. The rationale behind this strategy was to induce a metabolic substrate shift away from fatty acids toward glycolysis which consumes less oxygen per ATP generated. This phase 2 trial showed some modest improvements in symptoms, diastolic filling time and cardiac energetics in patients taking perhexiline relative to placebo-treated patients, but the drug was not pursued further because of multi-organ toxicity. Trimetazidine, an inhibitor or 3 ketoacyl-coA thiolase that catalyzes the last step in fatty acid β-oxidation to acetyl CoA, was also tested in a subsequent randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of patients with nonobstructive HCM.46 Patients treated with trimetazidine demonstrated a decrease in their exercise capacity relative to patients treated with placebo and no improvements in any of the secondary endpoints. This trial therefore signaled a potential for harm of inhibiting fatty acid β-oxidation in patients with HCM. This outcome is perhaps not surprising, in light of the profound downregulation of enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation and reduction in the content of acyl carnitines in the hearts of patients with HCM demonstrated in the present study.

A more promising therapeutic approach would be to bypass the deficit in fatty acid oxidation by enhancing the availability of alternate fuel sources for the production of ATP. Therapeutic ketosis is one such approach that has recently garnered considerable interest for treating patients with heart failure.25, 47, 48 An elevation in k etone bodies has been observed in hearts from patients with end-stage heart failure with reduced ejection fraction,42 and the contribution of ketones to ATP production in the human failing heart was recently shown to be 16.4%, almost 3-fold higher than the non-failing heart.49 Ketone body metabolism has been shown to represent an adaptive response to energy deprivation in animal models,50 further supporting the concept of a metabolic shift toward ketone metabolism as a viable therapeutic strategy. The ketone body, β-hydroxybutyrate, was elevated ~3.5-fold in hearts of patients with HCM compared to controls hearts, which could be an adaptive response to the decreased availability of acyl carnitines. Although we are not able to directly measure flux through any given pathway, elevation of the ketone breakdown product, C04-OH Butyryl, and an inverse correlation between this ketone breakdown and the expression of enzymes involved in long chain fatty acid oxidation, suggest an adaptive increase in ketone oxidation in HCM hearts compared to controls. This response could be augmented pharmacologically, either by direct administration of ketone ester formulations,47, 51 or by drugs that stimulate ketone body production from the liver. This is one of several mechanism by which sodium glucose co-transporter inhibitors (SGLT2i) have been postulated to afford marked cardiovascular benefit in patients with heart failure and reduced or preserved ejection fraction,52 recently demonstrated in large randomized clinical trials.53–55 The similar metabolic profile in HCM and failing hearts suggests that the benefits of SGLT2i could extend to patients with HCM, and provides a rationale for future clinical trials.

The branched chain amino acids, valine, leucine, and isoleucine, were elevated 2.5–3 fold in HCM hearts compared to control, similar to experimental models and human heart failure.43, 56 This may also represent an adaptive response to provide an alternate fuel source when fatty acids are depleted. However, the relative contribution of amino acids to the production of ATP is quite small (<5%),49 and it is unclear whether an increased abundance of BCAAs would make a meaningful difference. Suppression of BCAA catabolism appears to be a maladaptive component of myocardial remodeling,57 and therefore enhancement of BCAA catabolism in the heart or other organs may still be a reasonable target for reasons other than enhancing ATP production.

Modulation of NAD+ metabolism is another emerging strategy for therapeutic application in heart failure. Reduced bioavailability of NAD+ has been reported with aging and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and most recently in an experimental model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.58 In the latter study, administration of the NAD+ precursor, nicotinamide riboside (NR), or an activator of NAMPT, both attenuated cardiac dysfunction. Most of NAD+ in the heart is synthesized via the salvage pathway.59 Nampt, which catalyzes the conversion of NAM to NMN, is downregulated in pressure overload hypertrophy and myocardial ischemia. Interestingly, both NAM and NMN were significantly elevated in human HCM hearts compared to control hearts, suggesting that Nampt was not the rate limiting enzyme for NAD+ production. Since ATP is required for the conversion of NAM to NMN, and NMN to NAD+, perhaps the reduced bioavailability of NADH, NADP and NADPH in HCM hearts is related to reduced availability of ATP. If that were the case, then provision of NAD+ precursors or NAMPT activators would not be predicted to have therapeutic benefit in HCM.

Our study has some limitations. First, heart samples are only available from patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM. Therefore, we are unable to determine whether these findings are generalizable to patients with non-obstructive HCM, or to patients at an earlier stage of disease, including pre-clinical sarcomere variant carriers. As with any study comparing diseased to non-diseased hearts, hearts from patients with HCM are more fibrotic, which could in theory cause a “dilutional” effect of proteins and metabolites from cardiomyocytes. However, peptides derived from collagen proteins accounted for only 2% of the total peptides in the control samples and 4% in the HCM samples, arguing that this is unlikely to be a significant issue. Finally, the kinetics of actomyosin cross bridge attachment and ATP response curves may differ in the HCM samples compared to those measured in trabeculae from patients with coronary heart disease, due to changes in the phosphorylation of the myofilament contractile proteins.7

In conclusion, we identified a profound reduction in nucleotide availability in heart tissue samples from patients with HCM compared to control samples, a marked downregulation of enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation correlating with a reduction in the pool of acyl carnitines, accompanied by a possible adaptive increase in ketone oxidation. These results provide significant biological insights that lend support to the paradigm that reduced ATP availability contributes to the pathophysiology of HCM. These findings also have important therapeutic implications, and suggest that strategies aimed to reduce the capacity of the HCM heart to oxidize fatty acids could be ineffective or potentially harmful. Alternatively, augmentation of compensatory responses to increase utilization of alternate fuel sources, particularly ketones, holds promise for treatment of a variety of patients with different forms of cardiac hypertrophic remodeling that lead to heart failure.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is new?

Enzymes involved in long chain fatty acid oxidation were markedly downregulated and correlated with significant reductions in the content of long chain acyl carnitines in hearts from patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) compared to control heart tissue.

The ketone body 3-hydroxybutyrate, the 3 branched chain amino acids, and their breakdown products were all significantly increased in HCM heart samples compared to controls. These differences were independent of the patient’s genotype, age or sex.

Cardiac ATP content was markedly reduced in HCM heart samples and was inversely correlated with left atrial size, suggesting a relationship between nucleotide availability and the magnitude of diastolic dysfunction.

What are clinical implications?

These observations lend support to the paradigm that reduced availability of ATP contributes to the pathophysiology of HCM.

Strategies aimed to reduce the capacity of the HCM heart to oxidize fatty acids could be ineffective or potentially harmful.

Augmentation of compensatory responses to increase utilization of alternate fuel sources, particularly ketones, holds promise for treatment of patients with HCM and other forms of cardiac remodeling that lead to heart failure.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the Penn Metabolomics Core for conducting the metabolomics studies.

Sources of Funding:

DPK: NIH R01 HL128349, R01HL151345; ZA: NIH R01 HL152446, DOD W81XWH18–1-0503, SMD: UPenn discretionary funding and Presidential Professorship, MJP: NIH ROOHL 123041, R01 HL157487

Disclosures:

Dr. Previs is a consultant for Tara Biosystems. Dr. Day is a consultant for Bristol Myers Squibb, Tenaya Therapeutics, BioMarin Therapeutics, Lexeo Therapeutics, and Pfizer. Dr. Day also receives support from Bristol Myers Squibb for the SHaRe registry. Dr. Margulies is a consultant for Bristol Myers Squibb and receives research support from Amgen. Dr. Kelly is a consultant for Pfizer, Amgen, GSK, Myonid Therapeutics and Centaurus Therapeutics.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- HCM

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- PCr

phosphocreatine

- NADH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- LCMS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- BCAA

branched chain amino acid

- SGLT2i

sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor

References

- 1.Maron BJ and Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2013;381:242–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho CY, Day SM, Ashley EA, Michels M, Pereira AC, Jacoby D, Cirino AL, Fox JC, Lakdawala NK, Ware JS, et al. Genotype and Lifetime Burden of Disease in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Insights from the Sarcomeric Human Cardiomyopathy Registry (SHaRe). Circulation. 2018;138:1387–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho CY DS, Ashley EA, Michels M, Pereira A, Jacoby D, Cirino AL, Fox JC, Lakdawala NK, Ware JS, Caleshu CA, et al. Genotype and Lifetime Burden of Disease in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2018;138:1387–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh R, Buchan R, Wilk A, John S, Felkin LE, Thomson KL, Chiaw TH, Loong CCW, Pua CJ, Raphael C, et al. Defining the genetic architecture of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: re-evaluating the role of non-sarcomeric genes. European heart journal. 2017;38:3461–3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingles J, Goldstein J, Thaxton C, Caleshu C, Corty EW, Crowley SB, Dougherty K, Harrison SM, McGlaughon J, Milko LV, et al. Evaluating the Clinical Validity of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Genes. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2019;12:e002460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper AR, Goel A, Grace C, Thomson KL, Petersen SE, Xu X, Waring A, Ormondroyd E, Kramer CM, Ho CY, et al. Common genetic variants and modifiable risk factors underpin hypertrophic cardiomyopathy susceptibility and expressivity. Nat Genet. 2021;53:135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sequeira V, Wijnker PJ, Nijenkamp LL, Kuster DW, Najafi A, Witjas-Paalberends ER, Regan JA, Boontje N, Ten Cate FJ, Germans T, et al. Perturbed length-dependent activation in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with missense sarcomeric gene mutations. Circ Res. 2013;112:1491–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witjas-Paalberends ER, Guclu A, Germans T, Knaapen P, Harms HJ, Vermeer AM, Christiaans I, Wilde AA, Dos Remedios C, Lammertsma AA, et al. Gene-specific increase in the energetic cost of contraction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by thick filament mutations. Cardiovascular research. 2014;103:248–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helms AS, Alvarado FJ, Yob J, Tang VT, Pagani F, Russell MW, Valdivia HH and Day SM. Genotype-Dependent and -Independent Calcium Signaling Dysregulation in Human Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2016;134:1738–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Predmore JM, Wang P, Davis F, Bartolone S, Westfall MV, Dyke DB, Pagani F, Powell SR and Day SM. Ubiquitin proteasome dysfunction in human hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies. Circulation. 2010;121:997–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coats CJ, Heywood WE, Virasami A, Ashrafi N, Syrris P, Dos Remedios C, Treibel TA, Moon JC, Lopes LR, McGregor CGA, et al. Proteomic Analysis of the Myocardium in Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11:e001974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuldt M, Dorsch LM, Knol JC, Pham TV, Schelfhorst T, Piersma SR, Dos Remedios C, Michels M, Jimenez CR, Kuster DWD et al. Sex-Related Differences in Protein Expression in Sarcomere Mutation-Positive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:612215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuldt M, Pei J, Harakalova M, Dorsch LM, Schlossarek S, Mokry M, Knol JC, Pham TV, Schelfhorst T, Piersma SR, et al. Proteomic and Functional Studies Reveal Detyrosinated Tubulin as Treatment Target in Sarcomere Mutation-Induced Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2021;14:e007022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Velden J, Tocchetti CG, Varricchi G, Bianco A, Sequeira V, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Hamdani N, Leite-Moreira AF, Mayr M, Falcao-Pires I, et al. Metabolic changes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathies: scientific update from the Working Group of Myocardial Function of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovascular research. 2018;114:1273–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yotti R, Seidman CE and Seidman JG. Advances in the Genetic Basis and Pathogenesis of Sarcomere Cardiomyopathies. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2019;20:129–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spindler M, Saupe KW, Christe ME, Sweeney HL, Seidman CE, Seidman JG and Ingwall JS. Diastolic dysfunction and altered energetics in the alphaMHC403/+ mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JClinInvest. 1998;101:1775–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Javadpour MM, Tardiff JC, Pinz I and Ingwall JS. Decreased energetics in murine hearts bearing the R92Q mutation in cardiac troponin T. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;112:768–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crilley JG, Boehm EA, Blair E, Rajagopalan B, Blamire AM, Styles P, McKenna WJ, Ostman-Smith I, Clarke K and Watkins H. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to sarcomeric gene mutations is characterized by impaired energy metabolism irrespective of the degree of hypertrophy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;41:1776–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valkovic L, Clarke WT, Schmid AI, Raman B, Ellis J, Watkins H, Robson MD, Neubauer S and Rodgers CT. Measuring inorganic phosphate and intracellular pH in the healthy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy hearts by in vivo 7T (31)P-cardiovascular magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2019;21:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raman B, Ariga R, Spartera M, Sivalokanathan S, Chan K, Dass S, Petersen SE, Daniels MJ, Francis J, Smillie R, et al. Progression of myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: mechanisms and clinical implications. European heart journal cardiovascular Imaging. 2019;20:157–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toepfer CN, Garfinkel AC, Venturini G, Wakimoto H, Repetti G, Alamo L, Sharma A, Agarwal R, Ewoldt JF, Cloonan P, et al. Myosin Sequestration Regulates Sarcomere Function, Cardiomyocyte Energetics, and Metabolism, Informing the Pathogenesis of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2020;141:828–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Dijk SJ, Paalberends ER, Najafi A, Michels M, Sadayappan S, Carrier L, Boontje NM, Kuster DW, van Slegtenhorst M, Dooijes D, et al. Contractile dysfunction irrespective of the mutant protein in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with normal systolic function. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ranjbarvaziri S, Kooiker KB, Ellenberger M, Fajardo G, Zhao M, Vander Roest AS, Woldeyes RA, Koyano TT, Fong R, Ma N, et al. Altered Cardiac Energetics and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2021;144:1714–1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai L, Leone TC, Keller MP, Martin OJ, Broman AT, Nigro J, Kapoor K, Koves TR, Stevens R, Ilkayeva OR, Vega RB, et al. Energy metabolic reprogramming in the hypertrophied and early stage failing heart: a multisystems approach. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:1022–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honka H, Solis-Herrera C, Triplitt C, Norton L, Butler J and DeFronzo RA. Therapeutic Manipulation of Myocardial Metabolism: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021;77:2022–2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGarrah RW, Crown SB, Zhang GF, Shah SH and Newgard CB. Cardiovascular Metabolomics. Circ Res. 2018;122:1238–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Runte KE, Bell SP, Selby DE, Haussler TN, Ashikaga T, LeWinter MM, Palmer BM and Meyer M. Relaxation and the Role of Calcium in Isolated Contracting Myocardium From Patients With Hypertensive Heart Disease and Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Leary TS, Snyder J, Sadayappan S, Day SM and Previs MJ. MYBPC3 truncation mutations enhance actomyosin contractile mechanics in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2019;127:165–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanfear DE, Gibbs JJ, Li J, She R, Petucci C, Culver JA, Tang WHW, Pinto YM, Williams LK, Sabbah HN and Gardell SJ. Targeted Metabolomic Profiling of Plasma and Survival in Heart Failure Patients. JACC Heart failure. 2017;5:823–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gardell SJ, Hopf M, Khan A, Dispagna M, Hampton Sessions E, Falter R, Kapoor N, Brooks J, Culver J, Petucci C, et al. Boosting NAD(+) with a small molecule that activates NAMPT. Nature communications. 2019;10:3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clarke NE and Mosher RE. The water and electrolyte content of the human heart in congestive heart failure with and without digitalization. Circulation. 1952;5:907–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benson ES. Composition and state of protein in heart muscle of normal dogs and dogs with experimental myocardial failure. Circ Res. 1955;3:221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muangkram Y, Noma A and Amano A. A new myofilament contraction model with ATP consumption for ventricular cell model. J Physiol Sci. 2018;68:541–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teekakirikul P, Eminaga S, Toka O, Alcalai R, Wang L, Wakimoto H, Nayor M, Konno T, Gorham JM, Wolf CM, et al. Cardiac fibrosis in mice with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is mediated by non-myocyte proliferation and requires Tgf-beta. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:3520–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nistri S, Olivotto I, Betocchi S, Losi MA, Valsecchi G, Pinamonti B, Conte MR, Casazza F, Galderisi M, Maron BJ and Cecchi F. Prognostic significance of left atrial size in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (from the Italian Registry for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy). The American journal of cardiology. 2006;98:960–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leber Y, Ruparelia AA, Kirfel G, van der Ven PF, Hoffmann B, Merkel R, Bryson-Richardson RJ and Furst DO. Filamin C is a highly dynamic protein associated with fast repair of myofibrillar microdamage. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:2776–2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheikh F, Raskin A, Chu PH, Lange S, Domenighetti AA, Zheng M, Liang X, Zhang T, Yajima T, Gu Y, et al. An FHL1-containing complex within the cardiomyocyte sarcomere mediates hypertrophic biomechanical stress responses in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:3870–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christodoulou DC, Wakimoto H, Onoue K, Eminaga S, Gorham JM, DePalma SR, Herman DS, Teekakirikul P, Conner DA, McKean DM, et al. 5’RNA-Seq identifies Fhl1 as a genetic modifier in cardiomyopathy. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:1364–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ventura-Clapier R, Veksler V and Hoerter JA. Myofibrillar creatine kinase and cardiac contraction. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;133–134:125–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veksler VI, Lechene P, Matrougui K and Ventura-Clapier R. Rigor tension in single skinned rat cardiac cell: role of myofibrillar creatine kinase. Cardiovascular research. 1997;36:354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupte AA, Hamilton DJ, Cordero-Reyes AM, Youker KA, Yin Z, Estep JD, Stevens RD, Wenner B, Ilkayeva O, Loebe M, et al. Mechanical unloading promotes myocardial energy recovery in human heart failure. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2014;7:266–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bedi KC Jr., Snyder NW, Brandimarto J, Aziz M, Mesaros C, Worth AJ, Wang LL, Javaheri A, Blair IA, Margulies KB and Rame JE. Evidence for Intramyocardial Disruption of Lipid Metabolism and Increased Myocardial Ketone Utilization in Advanced Human Heart Failure. Circulation. 2016;133:706–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun H, Olson KC, Gao C, Prosdocimo DA, Zhou M, Wang Z, Jeyaraj D, Youn JY, Ren S, Liu Y, et al. Catabolic Defect of Branched-Chain Amino Acids Promotes Heart Failure. Circulation. 2016;133:2038–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ritterhoff J, Young S, Villet O, Shao D, Neto FC, Bettcher LF, Hsu YA, Kolwicz SC Jr., Raftery D and Tian R. Metabolic Remodeling Promotes Cardiac Hypertrophy by Directing Glucose to Aspartate Biosynthesis. Circ Res. 2020;126:182–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abozguia K, Elliott P, McKenna W, Phan TT, Nallur-Shivu G, Ahmed I, Maher AR, Kaur K, Taylor J, Henning A, et al. Metabolic modulator perhexiline corrects energy deficiency and improves exercise capacity in symptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2010;122:1562–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coats CJ, Pavlou M, Watkinson OT, Protonotarios A, Moss L, Hyland R, Rantell K, Pantazis AA, Tome M, McKenna WJ, et al. Effect of Trimetazidine Dihydrochloride Therapy on Exercise Capacity in Patients With Nonobstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:230–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yurista SR, Chong CR, Badimon JJ, Kelly DP, de Boer RA and Westenbrink BD. Therapeutic Potential of Ketone Bodies for Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021;77:1660–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Selvaraj S, Kelly DP and Margulies KB. Implications of Altered Ketone Metabolism and Therapeutic Ketosis in Heart Failure. Circulation. 2020;141:1800–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murashige D, Jang C, Neinast M, Edwards JJ, Cowan A, Hyman MC, Rabinowitz JD, Frankel DS and Arany Z. Comprehensive quantification of fuel use by the failing and nonfailing human heart. Science. 2020;370:364–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horton JL, Davidson MT, Kurishima C, Vega RB, Powers JC, Matsuura TR, Petucci C, Lewandowski ED, Crawford PA, Muoio DM, et al. The failing heart utilizes 3-hydroxybutyrate as a metabolic stress defense. JCI Insight. 2019;4:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yurista SR, Matsuura TR, Sillje HHW, Nijholt KT, McDaid KS, Shewale SV, Leone TC, Newman JC, Verdin E, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Ketone Ester Treatment Improves Cardiac Function and Reduces Pathologic Remodeling in Preclinical Models of Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2021;14:e007684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopaschuk GD and Verma S. Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Benefits of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors: A State-of-the-Art Review. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5:632–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Brueckmann M, Ofstad AP, Pfarr E, Jamal W and Packer M. SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-Reduced and DAPA-HF trials. Lancet. 2020;396:819–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, Januzzi J, Verma S, Tsutsui H, Brueckmann M, et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;383:1413–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Kober L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Anand IS, Belohlavek J, et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. The New England journal of medicine. 2019;381:1995–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun H and Wang Y. Branched chain amino acid metabolic reprogramming in heart failure. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2016;1862:2270–2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neinast M, Murashige D and Arany Z. Branched Chain Amino Acids. Annu Rev Physiol. 2019;81:139–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tong D, Schiattarella GG, Jiang N, Altamirano F, Szweda PA, Elnwasany A, Lee DI, Yoo H, Kass DA, Szweda LI, et al. NAD(+) Repletion Reverses Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ Res. 2021;128:1629–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xiao W, Wang RS, Handy DE and Loscalzo J. NAD(H) and NADP(H) Redox Couples and Cellular Energy Metabolism. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018;28:251–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.