Abstract

The regression analysis method is being widely adopted to analyse the tunnel strain, most of which ignore the strain-softening effect of the rock mass and fail to consider the influence of support pressure, initial stress state, and rock mass strength classification in one fitting equation. This study aims to overcome these deficiencies with a regression model used to estimate the tunnel strain. A group of geological strength indexes (GSI) are configured to quantify the input strength parameters and deformation moduli for the rock mass with a quality ranging from poor to excellent. A specific semi-analytical procedure is developed to calculate the tunnel strain around a circular opening, which is validated by comparison with those using existing methods. A nonlinear regression model is then established to analyse the obtained tunnel strain, combining twelve fitting equations to relate the tunnel strain and the factors including the support pressure, GSI, initial stress state, and critical softening parameter. Particularly, three equations are for the estimation of the critical tunnel strain, critical support pressure, and tunnel strain under elastic behaviour, respectively; and the other nine equations are for the tunnel strain with different strain-softening behaviours. The relative significance between the GSI, the initial stress and the support pressure on the tunnel strain is assessed.

Subject terms: Civil engineering, Solid Earth sciences

Introduction

The tunnel closure should be predicted appropriately as it is utilised to determine the stability of the rock mass and has been adopted in the engineering practices to guide the preliminary support design. Many analytical and numerical methods were proposed to assess the ground reaction curve with different failure criteria, flow rules, and failure behaviours of the rock mass1–6. The solutions reveal the relationship between the tunnel strain and the support pressure, which are efficacious for determining the support type with a particular geological condition. However, many solutions are often too cumbersome for practical applications due to its complicated derivation, equations, and multiple geological parameters. In this aspect, empirical methods seem to be more accessible to the engineering practisers due to their simplicity. Rock mass rating7–9, geological strength index10, and tunnelling quality index Q11,12 are the commonly utilised systems to guide the tunnel design by adequately quantifying the strength and deformation properties of the rock mass. Based on previous case back-analysis with assumed rock mass behaviours, the empirical methods often fail to account for the input geological parameters for a specific case. Thus, the strain redistribution and support performance cannot always be well-estimated by the empirical methods.

The regression analysis method has been adopted by many researchers to evaluate the tunnel strain as it takes advantage of the accuracy of the numerical tools and the convenience of the empirical schemes13–21. In the existing studies, great amount of data result was obtained using iterative procedures to analyse the large number of tunnelling cases. Multiple geological parameters for each tunnel case were simplified into a single strength parameter, and the rock mass deformation was quantified artificially as a function of the strength parameter using a nonlinear regression model. Among the studies, the functions enable to obtain the tunnel strain or the plastic zone radius for various tunnel cases with various geological scenarios. However, the limitation is obvious due to the difficulty when considering the strain of rock mass showing strain-softening behaviours, which is proved to be a common behaviour in numerous rock tests3. Also, many studies adopted only one fitting equation in the regression model, failing to consider the support pressure, the initial stress, and the strength classification (such as RMR, GSI, and the compressive strength). As a result, the application of analysis results with one fitting equation is limited to particular initial stress or rock mass quality.

In this paper, the index GSI is assigned with a group of values to represent the strength parameters and the deformation moduli for a strain-softening rock mass having various qualities. The tunnel strain around a circular opening under a hydrostatic stress state is obtained through a numerical scheme, which is validated through comparison with the previous studies. A more accurate estimation of the tunnel strain is further derived by semi-analytical procedures with different input geological parameters. Twelve fitting equations are proposed with the regression analysis method to correlate the tunnel strain with the support pressure, the GSI, the initial stress state, and the critical softening parameter; In particular, three equations are for the critical tunnel strain, the critical support pressure, and the tunnel strain in the elastic zone, and nine equations are for the tunnel strain in the plastic zone with different strain-softening behaviours.

Problem setup

Assumptions

Some assumptions are considered prior to the analysis:

A circular opening, with a radius of R0, is under a hydrostatic stress field of asymmetrically distributed around it; the radial stress and the tangential stress correspond to the minor and major principal stresses and , respectively;

Plane strain condition is considered as the deformation along the longitudinal direction of the tunnel is virtually uniform;

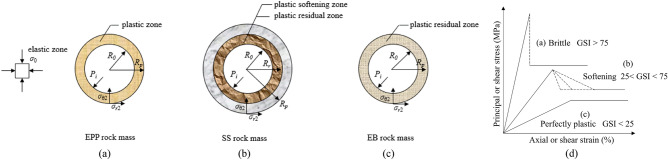

Material of the rock mass is isotropic, continuous, and initially elastic. Near underground excavations where confinement is reduced, most rock mass exhibits post-peak strength loss, which is called strain-softening property. The rock mass presents strain-softening (SS) behaviour; the elastic-perfectly-plastic (EPP) and elastic-brittle-plastic (EBP) behaviours are also considered, which are taken as special cases of the SS behaviour. The SS, EPP, and EBP behaviours of the rock mass induced by excavation operations are shown in Fig. 1. A support pressure pi is evenly imposed around the tunnel. σr2 and σθ2 represent the radial and tangential stresses at the elasto-plastic boundary, respectively. Within a SS rock mass, σr1 and σθ1 are the radial and tangential stresses at the plastic softening-residual boundary, respectively. The radii of the plastic softening and residual areas are symbolised as Rp and Rr, respectively. For the EPP and EBP rock masses, the radius of plastic area is represented as Rp

-

The softening parameter η characterises the softening quantity in the rock mass and is calculated as the gap between the tangential and radial plastic strains for the axisymmetric problem:

1 The critical value of η is denoted as η*, which occurs at the moment that the rock mass strength decays to its residual value. Specially, η* has values of ∞ and 0 for the EPP and EBP rock masses, respectively.

-

The Hoek–Brown (H-B) failure criterion is satisfactory in the quick estimate of the rock mass strength24:

where σci represents the uniaxial compression strength of the intact rock; mb, s and a are strength parameters of the Hoek–Brown rock mass. Because of the axisymmetric condition, the radial stress σr and the tangential stress σθ correspond to the minor and major principal stresses σ3 and σ1, respectively. Equation (3) can be transformed as:3 4 According to the geological observations in the field, Reference10,24,25 constructed the relation between the strength parameters (mb, s and a) and GSI. The empirical equations are listed as follows:5 6

where D is a coefficient influenced by the disturbance from blast impact and the stress relaxation. An optimised blasting operation with an accurate drilling control technique is assumed during the tunnel excavation, thereby, the damage to the tunnel wall is negligible and D is regarded as 0 by Hoek26. mi in Eq. (5) characterises the friction between the composition minerals.7

Figure 1.

Schematic graph of excavation problem and stress–strain relationship: (a) for EPP rock mass; (b) for SS rock mass; (c) for EBP rock mass; (d) stress–strain relationships (reference from3).

Strength classification of rock mass

The strength classification systems, such as the RMR, Q, and GSI, were successfully applied to many tunnel excavations. Various empirical equations by the systems are feasible to characterise the strength and deformation behaviours of the rock mass. Herein, GSI is incorporated to quantify the rock mass properties. Advantages of the GSI are demonstrated in three aspects: GSI is directly correlated to the strength constants in the Hoek–Brown failure criterion24; GSI can be estimated by RMR and Q systems, thus some strength parameters related to RMR can also be represented by GSI; and the residual strength of the strain-softening rock mass could be calculated from the peak value of GSI based on the equation proposed27.

Correlation between RMR and GSI

In the latest version, the relationship between GSI and RMR is:

| 8 |

It is noted that Eq. (8) is specialised for the dry condition of the rock mass and thus is not applicable to the weak rock mass with the RMR below 18.

Residual value of GSI

The guideline for the GSI was presented in25, which are to characterise the peak strength parameters of the EPP rock mass. Considering the strain-softening effect, Reference27 extended the GSI framework to consider the residual strength. In their study, through the in-situ block shear test at a number of real construction sites, the residual value of the GSI, denoted as GSIr, was expressed with a function of the peak value of GSI, denoted as GSIp:

| 9 |

Here, GSIp varies between 25 and 75 with 5 even intervals to consider the rock mass from very poor to excellent qualities. GSIr is calculated by substituting GSIp into Eq. (9) with values of GSIp and GSIr listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

GSIp and GSIr.

| GSIp | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 75 |

| GSIr | 17.9 | 20.1 | 21.9 | 23.4 | 24.6 | 25.6 | 26.3 | 26.9 | 27.2 | 27.4 | 27.5 |

Geological parameters

Within the plastic softening area

The parameters , , and for the SS rock mass can be calculated as2:

| 10 |

where represents any of , and . The peak and residual values of the strength parameters are denoted with superscripts ‘p’ and ‘r’, respectively, having , , , and , , . The value of decays linearly with the increase in when the rock mass is undergoing plastic softening, while it keeps unchanged with the value of above the critical value . equates to within the EPP rock mass and is within the plastic area of the EBP rock mass. The deformation modulus and strength parameters, such as and , also need to be determined. A number of compression tests show that deteriorates for the rock mass beyond the peak state28,29. It is proposed that wanes from its peak value to the residual during the softening stage since the rock mass quality is weakened, and the variations of and also obey Eq. (10)4. Therefore, , , and within the plastic softening area are all assumed to obey Eq. (10).

As observed in Eq. (10), the prerequisite for obtaining , , , , and in the softening area is to predict the peak and residual values (, , , , , , ,, , , , ). Based on GSIp and GSIr, the derivation of , , , , , , ,, , , , is presented in the following.

Within the plastic elastic and plastic residual areas

Deformation modulus

Empirical equations to determine Er were proposed with GSI and RMR.

Reference7:

| 11 |

Reference30:

| 12 |

Reference31:

| 13 |

Simplified Hoek and Diederichs equation32:

| 14 |

With GSIp and GSIr listed in Table 1, the calculated and from Eqs. (11)–(14) are shown in Table 2. In Table 3, Erp and Err can be estimated as the average values from Eqs. (11)–(14).

Table 2.

| GSIp | Equation (11) | Equation (12) | Equation (13) | Equation (14) | GSIr | Equation (11) | Equation (12) | Equation (13) | Equation (14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 3.162 | 2.700 | 1.050 | 17.883 | 2.099 | 1.198 | 0.953 | ||

| 30 | 4.217 | 4.288 | 1.645 | 20.069 | 2.381 | 1.575 | 1.126 | ||

| 35 | 5.623 | 6.400 | 2.567 | 21.897 | 2.645 | 1.946 | 1.295 | ||

| 40 | 7.499 | 9.113 | 3.986 | 23.403 | 2.885 | 2.291 | 1.452 | ||

| 45 | 10.000 | 12.500 | 6.138 | 24.623 | 3.094 | 2.599 | 1.592 | ||

| 50 | 10 | 13.335 | 16.638 | 9.341 | 25.585 | 3.271 | 2.861 | 1.712 | |

| 55 | 20 | 17.783 | 21.600 | 13.965 | 26.320 | 3.412 | 3.072 | 1.809 | |

| 60 | 30 | 23.714 | 27.463 | 20.365 | 26.852 | 3.518 | 3.232 | 1.883 | |

| 65 | 40 | 31.623 | 34.300 | 28.719 | 27.205 | 3.590 | 3.340 | 1.934 | |

| 70 | 50 | 42.170 | 42.188 | 38.828 | 27.399 | 3.631 | 3.401 | 1.962 | |

| 75 | 60 | 56.234 | 51.200 | 50.000 | 27.453 | 3.642 | 3.418 | 1.970 |

Table 3.

Estimated values of Erp and Err.

| GSIp | Erp (MPa) | GSIr | Err(MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 75 | 54.359 | 27.453 | 3.010 |

| 70 | 43.296 | 27.399 | 2.998 |

| 65 | 33.660 | 27.205 | 2.955 |

| 60 | 25.385 | 26.852 | 2.878 |

| 55 | 18.337 | 26.320 | 2.764 |

| 50 | 12.328 | 25.585 | 2.615 |

| 45 | 7.160 | 24.623 | 2.429 |

| 40 | 5.149 | 23.403 | 2.209 |

| 35 | 3.648 | 21.897 | 1.962 |

| 30 | 2.537 | 20.069 | 1.694 |

| 25 | 1.728 | 17.883 | 1.417 |

Strength constant mi

In the previous works, such as Reference33–35, was approximated by two methods. One is to determine the classification of from the rock type, such as in Hoek and Brown34. The other method is to estimate from the rock mass quality. Although the latter method tends to be subjective, it enables to establish a direct relationship between and the rock mass strength classification14. Therefore, the latter method is utilised in this study to correlate with GSI. The test data of for different GSI by Hoek and Brown33 and Hoek and Marinos36 is listed in Table 4. The data for estimating by GSI can be best-fitted by,

| 15 |

Table 4.

| (a) GSI | 75 | 50 | 30 | 75 | 75 | 65 | 20 | 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mi | 25 | 12 | 8 | 16.3 | 17.7 | 15.6 | 9.6 | 10 |

| (b) GSI | 20 | 5 | 13 | 28 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mi | 8.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 11.0 |

The coefficient of determination R2 reaches 81.38%, which indicates that the fitting line is in agreement with the test results. By Eq. (15) (see Fig. 2), the calculated mip and mir with different GSIp and GSIr are presented in Table 5.

Figure 2.

Fitting for mi.

Table 5.

Estimated values of mip and mir.

| GSIp | mip | GSIr | mir |

|---|---|---|---|

| 75 | 19.507 | 27.453 | 9.101 |

| 70 | 18.512 | 27.399 | 9.087 |

| 65 | 17.500 | 27.205 | 9.038 |

| 60 | 16.469 | 26.852 | 8.949 |

| 55 | 15.417 | 26.320 | 8.814 |

| 50 | 14.342 | 25.585 | 8.627 |

| 45 | 13.240 | 24.623 | 8.380 |

| 40 | 12.108 | 23.403 | 8.063 |

| 35 | 10.942 | 21.897 | 7.666 |

| 30 | 9.734 | 20.069 | 7.176 |

| 25 | 8.477 | 17.883 | 6.575 |

| 20 | 7.157 | 15.298 | 5.840 |

It is admitted that mi is the inherent characteristic of the intact rock. In this respect, mi corresponds to GSI = 100. But from many references33–36, it is found that generally a greater GSI gives rise to a larger value of mi. Hence, in the analysis, a rough and immature relation between GSI and mi is proposed as shown in Eq. (15) is proposed. The aim of Eq. (15) is to solve the tunnel strain as one of the input parameter in the latter. And according to Eq. (15), the tunnel strain is greater in comparison to a constant mi with no reduction. Then, the tunnel design will be conservative and safe. In this respect, Eq. (15) is reasonable. Furthermore, the sensitive analysis for the influence of multiple mechanical parameters on the tunnel strain has also been undertaken. It is found that in comparing with other input parameters such as the deformation modulus and the compressive rock strength, the effect of mi on the rock deformation is trivial. In this aspect, although Eq. (15) is subjective, it seems to be not very important factor that affect the results in this analysis.

Strength constants mb, s and a

According to Eqs. (5) to (7), when the disturbance factor D is 0, and can be obtained from GSIp, GSIr, , and ; and , , , can be calculated from GSIp and GSIr. The estimated result is listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Estimated values of mbp, sp, ap and mbr, sr, ar.

| GSIp | mbp | sp | ap | GSIr | mbr | sr | ar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75 | 7.988 | 62.177 | 0.501 | 27.453 | 0.682 | 0.316 | 0.527 |

| 70 | 6.341 | 35.674 | 0.501 | 27.399 | 0.680 | 0.314 | 0.527 |

| 65 | 5.014 | 20.468 | 0.502 | 27.205 | 0.671 | 0.307 | 0.527 |

| 60 | 3.947 | 11.744 | 0.503 | 26.852 | 0.656 | 0.295 | 0.528 |

| 55 | 3.090 | 6.738 | 0.504 | 26.320 | 0.634 | 0.278 | 0.529 |

| 50 | 2.405 | 3.866 | 0.506 | 25.585 | 0.605 | 0.257 | 0.530 |

| 45 | 1.857 | 2.218 | 0.508 | 24.623 | 0.568 | 0.230 | 0.532 |

| 40 | 1.421 | 1.273 | 0.511 | 23.403 | 0.523 | 0.201 | 0.535 |

| 35 | 1.074 | 0.730 | 0.516 | 21.897 | 0.471 | 0.170 | 0.539 |

| 30 | 0.799 | 0.419 | 0.522 | 20.069 | 0.413 | 0.139 | 0.544 |

| 25 | 0.582 | 0.240 | 0.531 | 17.883 | 0.350 | 0.109 | 0.550 |

| 20 | 0.411 | 0.138 | 0.544 | 15.298 | 0.284 | 0.082 | 0.560 |

Compressive strength of intact rock σci

Here, σci by GSI is calculated in three steps.

-

Estimation of σcm/σci

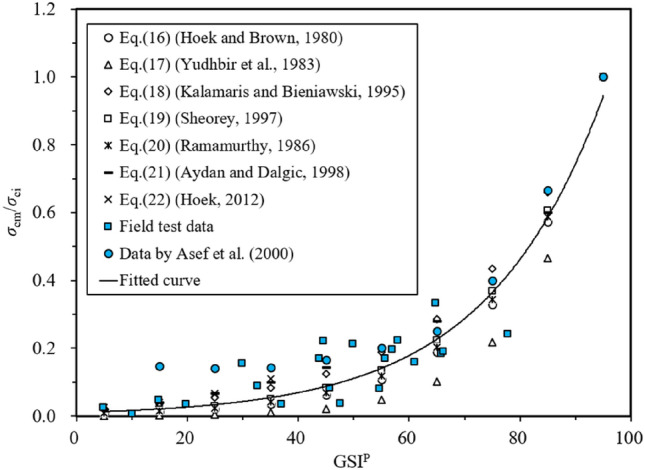

Considering different RMR, the reduction factor σcm/σci was proposed by Wilson37 to characterise the rock mass strength decreasing from its peak value to the residual. Assuming RMR-5 equals to GSI (see Eq. (8)), the estimated σcm/σci by Asef et al.14 are listed in Table 7. Other fitting equations for σcm/σci in the literature are presented in Eqs. (16) to (22):

Reference34:16 Reference38:17 Reference39:18 Reference40:19 Reference41:20 Reference42:21 Reference26:22 The GSI was given values from 5 to 95 with 10 intervals, which is to compute σcm/σci through Eqs. (16) to (22). The otained σcm/σci by Eqs. (16) to (22), by Asef et al.14, and the field data retrieved from realistic construction sites42 are plotted in Fig. 3. With the estimated σcm/σci, the best-fitting equation is expressed as:23 The coefficient of determination R2 is 95.84%, which indicates the prediction by Eq. (23) is acceptable.

-

Estimation of σcm and σci.

Reference43 claimed that σcm can be described as a function of RMR:24

Table 7.

Estimated values of σcm/σci proposed by Asef et al.14.

| RMR | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 |

| σcm/σci | 0.147 | 0.142 | 0.142 | 0.166 | 0.200 | 0.250 | 0.400 | 0.666 | 1.000 |

Figure 3.

Fitting for σci/σcm.

Table 8.

Estimated values of σcip and σcir.

| GSIp | σcip (MPa) | GSIr | σcir (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 75 | 237.222 | 27.4 | 66.781 |

| 70 | 219.950 | 27.4 | 66.629 |

| 65 | 201.942 | 27.2 | 66.088 |

| 60 | 183.276 | 26.9 | 65.111 |

| 55 | 164.134 | 26.3 | 63.656 |

| 50 | 144.813 | 25.6 | 61.682 |

| 45 | 125.708 | 24.6 | 59.160 |

| 40 | 107.271 | 23.4 | 56.066 |

| 35 | 89.957 | 21.9 | 52.406 |

| 30 | 74.155 | 20.1 | 48.201 |

Semi-analytical procedure

Governing equation

For the case of plane strain, the equilibrium equation is:

| 26 |

In terms of small strain case, the displacement compatibility is:

| 27 |

Stresses and strains in the plastic softening zone

The generalised H-B failure criterion33 is :

| 28 |

where and are the major and minor principal stresses. is the uniaxial compression strength of intact rock. and are the strength constants, respectively. According to Eq. (28), the yielding function of the rock mass surrounding a circular opening is:

| 29 |

First, , the radial stress at the elastic–plastic boundary is solved by combing Eq. (26) with Eq. (29) through Runge–Kutta method.

A constant radial stress increment is assumed for each annulus, i.e.:

| 30 |

where and are the radial stresses at the inner and outer boundaries of each annulus (i.e. r = r(i) and r(i-1)).

The plastic strain is expressed as:

| 31 |

where and are the radial and tangential strains at r = r(i); and are the radial and tangential strains at r = r(i-1); and are the radial and tangential plastic strain increments; and are the radial and tangential elastic strain increments.

According to Hooke’s law, the elastic strain increments can be correlated to the stress increments, i.e.:

| 32 |

The relation between and can be given as:

| 33 |

where is the dilatancy coefficient and can be written as:

| 34 |

where is the dilatancy angle, it should be noted that is not equal to the friction angle when the non-associated flow rule is employed.

In order to solve the strain components, Eq. (27) can be rewritten as:

| 35 |

where is the radial displacement at r = r(i); substituting Eqs. (32) and (33) into Eqs. (31) and (36), one gains:

| 36 |

| 37 |

| 38 |

where

In accordance with Reference4, the relation between and can be derived as:

| 39 |

As illustrated in Eqs. (36), (37) and (39), , and are independent of the radius , or . This means that with no need to obtain the value of , stress and strain components in the plastic softening zone can be solved first.

Radii of plastic softening and residual zones

IN the plastic residual zone, by incorporating Eq. (29) into Eq. (26), one obtains:

| 40 |

where and sr are the strength parameters in the residual zone. The boundary conditions for Eq. (41) are: (1) r = R0, σr = pi; and (2) r = Rr, σr = σr1. Hence, the following equation can be derived from Eq. (40):

| 41 |

Equation (41) illustrates that can be obtained by use of , and . In fact, from Eq. (40), the relation between and can be derived as follows:

| 42 |

where j is the number of the annulus immediately outside the plastic softening-residual boundary. Equation (42) shows that can be solved by .

In addition, when only the plastic softening zone is formed, Eq. (42) can be rewritten into:

| 43 |

Radial displacement of plastic softening and residual zones

Essentially, after obtaining , in the plastic softening zone can be solved by Eq. (38). As for u in the plastic residual zone, it can be obtained in a closed-form as shown in Eq. (44)44. Since the plastic softening zone is considered herein, and of Eq. (44) are substituted for and of Eq. (38) presented in the elastic-brittle-plastic solution44.

| 44 |

where G is the shear modulus, G = E/2(1 + μ).

Verification

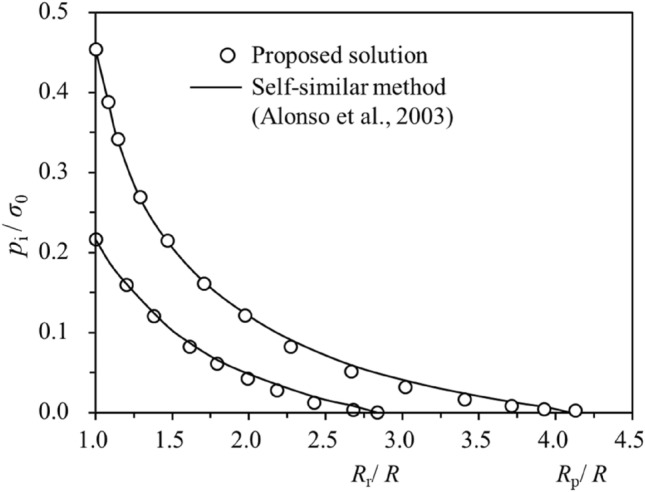

The strength parameters for a group of tunnel excavation cases are used to verify the proposed semi-analytical procedure (Table 9). The cases are from the References2,3,6. Figure 4 demonstrates the distribution of the normalised radial displacement predicted by the semi-analytical procedure and a self-similar method2 for the SS rock masses with different dilatancy behaviours, which show good agreement with each other. The normalised support pressure versus the normalised plastic radii is plotted in Fig. 5. Comparison of the Ground Reaction Curves for the SS rock mass obtained from the semi-analytical procedure and self-similar method2 are presented in Fig. 6, also showing good convergence. Therefore, the semi-analytical procedure proposed in this study is sufficiently reliable in predicting the tunnel strain for the SS rock masses. It should be noted that EPP and EPB rock masses can be regarded as the special cases for the SS rock masses. In this aspect, the above can also serve as a verification of the EPP and EPB rock masses.

Table 9.

Parameters of the tunnel cases for verification.

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ψ/° | φp/2 | φp/4 | φp/8 | 0 | 3.75 | 3.1 |

| φp/° | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 24.81 |

| φr/° | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 15.69 |

| η* | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.017 |

| Er/GPa | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 3.837 | 3.837 |

| 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| R0/m | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.744 | |

| 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.397 | |

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 12 |

Figure 4.

Variations of dimensionless support pressure pi/σ0 versus dimensionless radial displacement u0Er/ 2R0(1 + μ)(σ0 – σr2) for case C1, C2, C3 and C4.

Figure 5.

Variations of dimensionless support pressure pi/σ0 versus plastic radius Rr/R0, or Rp/R0 for case C5.

Figure 6.

Ground reaction curve for case C6.

In some existing studies, efforts were given to calculate the tunnel strain ɛθ for the EPP rock mass with a wide range of qualities13–16. Particularly, Reference16 established a regression model with 20 < RMR < 90:

| 45 |

Based on Eqs. (8), (45) can be transferred to the following equation,

| 46 |

The value of εθ predicted by the proposed procedures in this study can be compared with that by Eq. (46).

Then GSIp was varied between 40 and 65 with 5 intervals to compare the proposed method with that by Reference16. For each GSIp value, σ0 ranges from 2.7 to 13.5 MPa, pi is 0 and R0 is 5 m. εθ_Basarir is obtained by dividing u0 by R016. The comparison of εθ obtained from the semi-analytical procedure and εθ_basarir by the scheme in Reference16 shows good agreement with the coefficient of determination R2 up to 90.8% (see Fig. 7). Then the rationality of the input geological parameters (Erp, Err, σcip, σcir, mip, mir, mbp, mbr,sp, sr, ap, and ar) in this study can be validated to some extent.

Figure 7.

Comparison between εθ and εθ_Basarir.

Regression model for tunnel strain

The strain εθ can be fitted as a function of GSIp, σ0 and pi/σ0 by a nonlinear regression method. The equations for εθ in the plastic and elastic areas differ from each other:

| 47a |

| 47b |

In Eq. (38), the critical strain εθ2 and the critical support pressure σr2 need to be determined prior to solving εθ. Combining Eqs. (26) and (27), fitting equations for σr2 and εθ2 can be written as:

| 48a |

| 48b |

The Taylor series polynomial regression (PR) can be adopted to solve f1, f3 and f4. Particularly for f1, a nonlinear function can be constructed as:

| 49 |

For f3 and f4, the variable y (εθ2 or σr2) depends on x1 (GSIp) and x2 (σ0), as:

| 50 |

As for f2, the relation between the variable y (εθ) and the independent variables x1 (GSIp), x2 (σ0), and x3 (pi/σ0) can be derived from Eq. (28) as:

| 51 |

To obtain the coefficients in Eqs. (40) to (42), εθ for a large number of tunnelling cases are calculated by the proposed iterative procedure. The input geological parameters (GSIp, GSIr, Erp, Err, σcip, σcir, mbp, mbr, sp, sr, ap, and ar) for the calculation are given in Tables 1, 3, 6, and 8. Nine values for η* within cases A1 to A9 are listed in Table 10. σ0 varies from 5 to 50 MPa with intervals of 5 MPa. pi/σ0 ranges from 0 to 1 MPa and 10 to 20 values are selected for different combination of pi and σr2. f2, f3 and f4 are merely correlated to the peak geological parameters in the elastic zone. The regression model is composed of twelve equations: three equations are for f2, f3 and f4, and nine equations are for f1. Then the coefficients can be determined with the Levenberg Marquardt iteration algorithm (see Tables 11 and 12), which is validated through the analysis of variance ANOVA. The predictions with the twelve equations match well with those by the semi-analytical procedure.

Table 10.

Critical plastic softening parameter η*.

| Case | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 | A7 | A8 | A9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| η* | 0 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.025 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 | ∞ |

Table 11.

Coefficients in f4, f3, and f2.

| f4 | f3 | f2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1 (10–5) | 42.5845 | a1 | − 0.28589 | a1 | 0.000273 |

| b1 (10–5) | 2.88088 | b1 | 0.0338 | b1 | − 0.01925 |

| b2 (10–5) | 1.1807 | b2 | 0.91007 | c1 | 0.47982 |

| c1 (10–5) | 0.075412 | c1 | − 0.00195 | d1 | − 3.57994 |

| c2 (10–5) | 0.043128 | c2 | 0.00938 | ||

| c3 (10–5) | 0.035988 | c3 | − 0.01975 | ||

| d1 (10–5) | 0.000485 | d1 (10–5) | 2.44631 | ||

| d2 (10–5) | 0.000479 | d2 (10–5) | − 7.68786 | ||

| d3 (10–5) | 0.000468 | d3 (10–5) | 1.3393 | ||

| d4 (10–5) | 0.000488 | d4 (10–5) | 5.4923 |

Table 12.

Coefficients in f1: (a) when η* = ∞, 1, 0.5, 0.1, 0.05; (b) when η* = 0.025, 0.01, 0.005, 0.

| (a) η* | ∞ | 1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.05 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | 0.37576 | − 0.74117 | − 0.61639 | 1.08615 | 3.27504 |

| b1 | − 0.3432 | − 0.24502 | − 0.2742 | − 0.43415 | − 0.58165 |

| b2 | − 16.0768 | − 16.14255 | − 16.55177 | − 16.45784 | − 19.47774 |

| b3 | 0.32959 | 0.41235 | 0.46672 | 0.53739 | 0.53157 |

| c1 | 0.00788 | 0.00246 | 0.00225 | 0.00656 | 0.00967 |

| c2 | 19.49741 | 21.77123 | 22.57404 | 21.46441 | 27.19204 |

| c3 | − 0.00289 | − 0.00176 | − 0.00156 | − 0.00362 | − 0.00485 |

| c4 | 0.33925 | 0.34786 | 0.36874 | 0.38357 | 0.45668 |

| c5 | − 0.07987 | − 0.22695 | − 0.26771 | − 0.70855 | − 0.82604 |

| c6 | − 0.00862 | − 0.02094 | − 0.02172 | − 0.01372 | − 0.00686 |

| d1 | − 0.00059963 | − 0.01182 | − 0.00343 | 0.00441 | 0.00765 |

| d2 (10–5) | 2.24755 | 0.707777 | − 0.862592 | 4.88805 | 10.3286 |

| d3 (10–5) | 4.96784 | 15.5397 | 17.8538 | 8.07328 | − 8.19822 |

| d4 | − 0.01828 | 0.29111 | 0.37644 | 0.83708 | 0.87071 |

| d5 | − 0.00656 | − 0.02268 | − 0.00153 | 0.00261 | 0.00278 |

| d6 | − 15.49841 | − 18.33127 | − 18.88734 | − 19.65351 | − 25.08435 |

| d7 (10–5) | − 1.72834 | − 0.615086 | − 0.667556 | − 3.36496 | − 5.69299 |

| e1 (10–4) | − 7.9539 | − 29.9 | − 33.9 | − 21.9 | − 36.7 |

| e2 (10–4) | 14.6 | 23.1 | 16.2 | − 76.6 | − 95.5 |

| e3 (10–5) | 9.11563 | 8.73084 | 10.4683 | 1.56558 | − 2.26792 |

| e4 (10–7) | − 2.61481 | − 9.51432 | − 11.4793 | − 0.354321 | 12.6512 |

| e5 | 0.06741 | − 0.27619 | − 0.2907 | − 0.48179 | − 0.34204 |

| f1 (10–9) | 0.532421 | 1.95193 | 3.18653 | − 3.039 | − 8.42 |

| f2 | − 0.00215 | − 0.00076716 | 0.00017157 | 0.00582 | 0.00517 |

| (b) η* | 0.025 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | 3.37806 | − 1.23767 | − 0.45896 | 3.37629 | |

| b1 | − 0.56164 | − 0.16611 | − 0.15858 | − 0.47128 | |

| b2 | − 21.86517 | − 21.45617 | − 19.50907 | − 16.89839 | |

| b3 | 0.48318 | 0.52196 | 0.38419 | 0.25426 | |

| c1 | 0.0088 | − 0.00075226 | − 0.00132 | 0.00759 | |

| c2 | 33.78561 | 37.16971 | 26.33782 | 28.57907 | |

| c3 | − 0.00656 | − 0.00627 | − 0.00162 | − 0.00173 | |

| c4 | 0.51334 | 0.43875 | 0.29709 | 0.15241 | |

| c5 | − 0.96887 | − 0.66871 | − 0.00379 | 0.38674 | |

| c6 | − 0.00277 | − 0.00527 | − 0.0063 | 0.00259 | |

| d1 | 0.01421 | 0.00686 | − 0.0018 | − 0.00575 | |

| d2 (10–5) | 14.2824 | 10.6465 | − 4.79792 | − 2.97141 | |

| d3 (10–5) | − 19.9824 | 2.54789 | 19.5277 | − 4.91271 | |

| d4 | 0.85951 | 0.57685 | − 0.19027 | − 0.13331 | |

| d5 | 0.0037 | 0.00075557 | − 0.01386 | − 0.02578 | |

| d6 | − 30.75648 | − 32.48237 | − 20.64928 | − 36.72157 | |

| d7 (10–5) | − 4.78882 | 2.51696 | 2.35951 | − 5.6103 | |

| e1 (10–4) | − 68.6 | − 81.9 | 25.7 | 109.2 | |

| e2 (10–4) | − 97.7 | − 19.3 | 94.2 | − 39.7 | |

| e3 (10–5) | − 7.26793 | − 3.79109 | 12.6535 | 32.7694 | |

| e4 (10–7) | 19.6994 | − 4.32378 | − 20.7783 | 4.66801 | |

| e5 | − 0.18899 | − 0.15045 | 0.17124 | 0.25735 | |

| f1 (10–9) | − 10.6367 | − 2.62886 | 13.3079 | 2.50107 | |

| f2 | 0.00376 | − 0.00163 | − 0.00931 | 0.00429 |

Parametric study

Variation of tunnel strain with different critical softening parameters

Values of εθ are calculated by the proposed regression model, which are plotted for Cases A1 to A9 versus GSIp, σ0, and pi/σ0, respectively, as in Figs. 8 and 9. In Fig. 8, GSIp is variable, σ0 is 30 MPa and pi/σ0 is 0.1, and in Fig. 9, pi/σ0 is variable, GSIp is 30 and σ0 is 5 MPa. When GSIp is 70 or 75, and pi/σ0 is 0.3, εθ maintains constant. The reason is that GSIp and pi/σ0 are relatively large, so that the rock mass takes elastic deformations and is independent of η*. With plastic deformations in the rock mass, εθ decreases to a substantial constant with the increase in η*. The decrease of εθ is induced by the shrinkage of the plastic residual area. If η* is nil, all rock mass within the plastic area is characterised with the residual strength; and the maximum εθ is therefore reached; as η* increases, εθ falls rapidly since the softening area expands; and εθ becomes stable when the softening zone dominates in the plastic area. The expansion of the plastic residual area is the critical factor enhancing the deformation within the rock mass. In the practical engineering, the measures to decrease the plastic residual zone can substantially improve the tunnel stability. Furthermore, εθ falls quickly and becomes constant within a small η* for excellent quality rock mass, whereas εθ for the weak rock mass decreases slowly and the decline process is prolonged until a plateau is reached (see Fig. 9). Hence, the rock mass deformation decreases more suddenly with a better quality rock while η* increases.

Figure 8.

Variation of εθ versus cases A1 to A9: (a) GSIp ranges from 25 to 75; (b) GSIp = 65, 70, 75.

Figure 9.

Variation of εθ versus cases A1 to A9: (a) pi/σ0 ranges from 0 to 0.3; (b) pi/σ0 = 0.25, pi/σ0 = 0.30.

Difference of tunnel strain between the EPP and EBP rock masses

εθ for the EPP rock mass is symbolised by εθ_EPP. The increase ratio of εθ for the EBP rock mass in comparison to the EPP counterpart is denoted by Δεθ/εθ_EPP. Δεθ/εθ_EPP versus GSIp for variations in σ0 and pi/σ0 is plotted in Fig. 10.

Figure 10.

Variation of Δεθ/εθ_EPP versus GSIp : (a) pi/σ0 = 0; (b) pi/σ0 = 0.1; (c) pi/σ0 = 0.2; (d) pi/σ0 = 0.3.

When pi/σ0 is 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3, Δεθ/εθ_EPP decreases as GSIp increases (see Fig. 10b–d). Hence, while pi/σ0 exceeds 0.1, the effect of η* on εθ for the weakest rock mass (GSIp = 25) is the greatest, which should be highlighted. While pi is 0, and σ0 ranges from 10 to 20 MPa, Δεθ/εθ_EPP rises but then decreases with the increase in GSIp (Fig. 10a). The maximum Δεθ/εθ_EPP appears while GSIp is around 45 or 50. In this case, the influence of η* on εθ for the moderate rock mass (GSIp = 45, 50) is the largest. For GSIp is 50 and σ0 is 20 MPa, Δεθ/εθ_EPP reaches almost 10.64 for pi/σ0 is 0 but drops to 1.77 for pi/σ0 is 0.1 (see Fig. 10a,b). This means that the growth of pi effectively weakens the softening effect on the deformation for moderate quality rock mass with high initial stress. Furthermore, when GSIp is greater than 55 and pi/σ0 exceeds 0.1, Δεθ/εθ_EPP for most cases is 0, which means εθ by EPP and EBP rock masses are equivalent (see Fig. 10b–d). This is because that the rock mass undergoes an elastic deformation. Therefore, if pi/σ0 reaches 0.1, the rock mass deformation is inconsiderable and irrespective of η* for the excellent rock mass quality (GSIp ≥ 55).

Sensitive analysis

Figure 11 illustrates the sensitivity analysis concerning the tunnel strain ɛθ, showing the relative significance of the most significant input data (i.e. GSIp, σ0 and pi/σ0) on this final output (i.e. ɛθ). Three base cases with different rock mass qualities are given in Table 13. In the sensitive analysis, σ0 varies between 5 and 30 MPa with even intervals of 5 MPa. pi/σ0 ranges from 0 to 0.225 with 0.025 intervals. GSIp ranges from 25 to 75 with 5 intervals. GSIp, σ0 or pi/σ0 is represented by the variable m. GSIp, σ0 or pi/σ0 in cases B1 to B3 is represented by mbase. ɛθ calculated by cases B1 to B3 is represented by ɛθ,base.

Figure 11.

Sensitive analysis of GSIp, σ0 and pi/σ0 on εθ: (a) cases B1; (b) case B2; (c) case B3.

Table 13.

GSI, σ0 and pi/σ0 for cases B1 to B3.

| Case B1 | Case B2 | Case B3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSIp | 70 | 50 | 30 |

| σ0 (MPa) | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| pi/σ0 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

In comparison with the EBP rock mass, εθ/εθ,base of the EPP rock mass with the moderate and weak rock qualities tends to be closer to the line for εθ/εθ,base is 1 (see Fig. 11b,c). In this respect, εθ for the EBP rock mass is more sensitive to the change in GSIp, pi/σ0 and σ0. However, for the excellent quality rock mass, εθ/εθ,base of EBP rock mass coincides with that of EPP rock mass (Fig. 11a). This is attributed to that the rock mass exhibits the elastic behaviour, and thus εθ is independent of the plastic parameters. In this respect, the influence of GSIp, pi/σ0 or σ0 on εθ by EPP and EBP rock masses are equivalent.

Among the input parameters GSIp, σ0 and pi/σ0, the change in GSIp gives rise to the greatest change in εθ. Especially for the excellent rock mass, εθ/εθ,base by GSIp is considerably higher than σ0 and pi/σ0 (Fig. 11a). Therefore, GSIp is of vital importance in controlling εθ. The relative significance of pi/σ0 and σ0 varies with different conditions. For the EBP rock mass, when pi/σ0 decreases and σ0 increases with an equivalent variation, εθ/εθ,base affected by pi/σ0 is always higher than that by σ0; and it becomes remarkably higher while pi/σ0 decreases to a small value. Hence, for the EBP rock mass, when pi/σ0 decreases and σ0 increases, the influence of pi/σ0 on εθ is larger than that of σ0. For all the other conditions, the influence of σ0 on εθ is greater than that of pi/σ0. For instance, for the EPP rock mass, the change in σ0 causes a larger variation in εθ; for the EBP rock mass, when pi/σ0 increases and σ0 decreases with the equivalent variation, a decrease of σ0 yields a higher reduction of εθ. As the weak rock mass shows the EPP behaviour33, the reduction of σ0 exerts greater influence than the increase in pi/σ0 in controlling the rock deformation for the weak rock mass. In the tunnelling engineering, the reduction of σ0 and the increase of pi/σ0 can be obtained by relieving the stress and installing the rigid support, respectively.

Conclusions

Various GSI were considered to quantify the input geological parameters for the strain-softening rock masses with various qualities. A specialised numerical scheme was presented to calculate the tunnel strain around a circular opening within the rock mass. The proposed semi-analytical procedure and the input geological parameters were validated through comparison of the tunnel strain obtained by the semi-analytical procedure with that predicted by the previous studies. With the obtained input geological parameters, more accurate quantification of the tunnel strain was obtained by a semi-analytical procedure. A regression model, composed of 12 fitting equations, was further proposed: 3 equations were to calculate the critical tunnel strain, the critical support pressure and the tunnel strain with elastic behaviour, and 9 equations were for the tunnel strain with different strain-softening behaviours. The model provides practical guidelines to assess the deformations of the rock mass prior to the tunnel construction. Following conclusions can then be drawn:

The tunnel strain wanes to a constant value with the critical softening parameter keeps increasing, which is mainly ascribed to the shrinkage of the plastic residual area. Reversely, the rock deformation is mainly raised due to the expansion of the plastic residual area. In the practical engineering, the measures to decrease the plastic residual area can substantially improve the tunnel stability.

While the support pressure exceeds a certain value (pi/σ0 ≥ 0.1), the critical softening parameter makes the most significant influence on the tunnel strain for the weakest rock mass (GSIp = 25). In comparison, with no support pressure (pi/σ0 ≥ 0) and relatively high initial stress (σ0 ≥ 10 MPa), the influence of the critical softening parameter for the moderate rock mass (GSIp is around 45 or 50) is the most significant. While the support pressure that acted on the good rock mass quality (GSIp ≥ 55) exceeds a certain value, the rock mass deformation becomes inconsiderable.

While the rock mass exhibits a strain-softening behaviour, the tunnel strain for the EBP rock mass can be affected by the change in the rock mass quality, the support pressure and the initial stress state. Among the three input geological parameters (i.e. GSIp, the support pressure, and the initial stress), GSIp is of vital importance in controlling the tunnel strain. The relative significance of the support pressure and initial stress varies with different conditions. For the EBP rock mass, with the support pressure decreases and the initial stress increases, the tunnel strain is mostly influenced by the variation in the support pressure. For all other conditions, the initial stress state becomes the critical factor.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52279118, 52009129 and 51909248).

List of symbols

- η

Softening parameter

- ,

Radial and tangential stresses

- ,

Radial and tangential strains at r = r(i)

- ,

Radial and tangential strains at r = r(i-1)

- ,

Radial and tangential plastic strains

- ,

Radial and tangential plastic strain increments

- ,

Radial and tangential elastic strain increments

Radial displacement at r = r(i)

- p0

Initial ground stress

- μ

Poisson’s ratio

- σ1, σ3

Major and minor principal stresses at failure, respectively

- GSI

Geological Strength Index

- GSIp, GSIr

Peak and residual values of the Geological Strength Index

- ψ

Dilatancy angle

Dilatancy coefficient

- φ

Friction angle

Uniaxial compression strength of intact rock

- mb, s, a

Strength parameters of the Hoek–Brown rock mass

mb, s and α

- D

Disturbance coefficient

- RMR

Rock Mass Rating

- η*

Critical value of the softening parameter

Strength of a rock mass

- σr(i),σr(i-1)

Radial stresses at the inner and outer boundaries of each annulus

- Erp , Err

Peak and residual values of the deformation modulus

Radial stress at the elastic–plastic boundary

Author contributions

Contributor roles taxonomy: Y.D. and L.C.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation and writing-original draft; Q.S.: data curation, formal analysis; Y.D.: visualization, project administration; J.Z., Z.G. and L.C.: writing—review and editing.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Einstein HH, Schwartz CW. Discussion of the article: Simplified analysis for tunnel supports. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. ASCE. 1979;106(7):835–838. doi: 10.1061/AJGEB6.0001013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso E, Alejano LR, Varas F, Fdez-Manin G, Carranza-Torres C. Ground response curves for rock masses exhibiting strain-softening behaviour. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 2003;27:1153–1185. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alejano LR, Rodriguez-Dono A, Alonso E, et al. Ground reaction curves for tunnels excavated in different quality rock masses showing several types of post-failure behaviour. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2009;24(6):689–705. doi: 10.1016/j.tust.2009.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YK, Pietruszczak S. A new numerical procedure for elasto-plastic analysis of a circular opening excavated in a strain-softening rock mass. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2008;15(2):187–213. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang SL, Yin XT, Tang H, Ge XR. A new approach for analyzing circular tunnel in strain-softening rock masses. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2010;47:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2009.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song F, Rodriguez-Dono A. Numerical solutions for tunnels excavated in strain-softening rock masses considering a combined support system. Appl. Math. Model. 2021;92:905–930. doi: 10.1016/j.apm.2020.11.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bieniawski ZT. Determination rock mass deformability: Experience from case histories. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1978;15:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0148-9062(78)90956-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bieniawski ZT. Rock Mechanics Design in Mining and Tunnelling. A. A. Balkema; 1984. pp. 97–133. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bieniawski ZT. Engineering Rock Mass Classifications. Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoek E. Strength of rock and rock masses. ISRM News J. 1994;2(2):4–16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barton, N. Rock mass classification, tunnel reinforcement selection using the Q-system. In Proceedings of the ASTM Symposium on Rock Classification Systems for Engineering Purposes. Cincinnati, Ohio (1987).

- 12.Barton N. Some new Q-value correlations to assist in site characterisation and tunnel design. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2002;39:185–216. doi: 10.1016/S1365-1609(02)00011-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoek, E. Tunnel support in weak rock. In Symposium of Sedimentary rock Engineering, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–22 (1998).

- 14.Asef MR, Reddish DJ, Lloyd PW. Rock-support interaction analysis based on numerical modelling. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2000;18(1):23–37. doi: 10.1023/A:1008968013995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sari D. Rock mass response model for circular openings. Can. Geotech. J. 2007;44:891–904. doi: 10.1139/t07-034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basarir H, Genis M, Ozarslan A. The analysis of radial displacements occurring near the face of a circular opening in weak rock mass. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2010;47:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2010.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goh ATC, Zhang WG. Reliability assessment of stability of underground rock caverns. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2012;55:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2012.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang WG, Goh ATC. Regression models for estimating ultimate and serviceability limit states of underground rock caverns. Eng. Geol. 2015;188:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.enggeo.2015.01.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong YK, Cui L, Zhang X. Multiple-GPU parallelization of three-dimensional material point method based on single-root complex. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Eng. 2002;123(6):1481–1504. doi: 10.1002/nme.6906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen Q, Zheng J-J, Cui L, Pan Y, Cui B. A procedure for interaction between rock mass and liner for deep circular tunnel based on new solution of longitudinal displacement profile. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022;26(1):280–298. doi: 10.1080/19648189.2019.1657960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan N, Jiang J, Dong Y, Guo L, Song L. Approach for evaluating instantaneous impact forces during submarine slide-pipeline interaction considering the inertial action. Ocean Eng. 2022;245:110466. doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2021.110466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui L, Sheng Q, Dong Y‐K, Xie M‐X. Unified elasto‐plastic analysis of rock mass supported with fully grouted bolts for deep tunnels. Int J Numer Anal Methods Geomech. 2022;46(2):247–271. doi: 10.1002/nag.3298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui L, Sheng Q, Dong Y, Ruan B, Xu D-D. A quantitative analysis of the effect of end plate of fully-grouted bolts on the global stability of tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021;114:104010. doi: 10.1016/j.tust.2021.104010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoek, E., Carranza-Torres, C. & Corkum, B. Hoek-Brown criterion-2002 edition. In Proc NARMS-TAC Conference, Toronto, Vol. 1, 267–273 (2002).

- 25.Hoek E, Kaiser PK, Bawden WF. Support of Underground Excavations in Hard Rock. Balkema; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoek, E. Blast Damage Factor D Technical note for RocNews-February 2, 2012, Winter 2012 Issue (2012).

- 27.Cai M, Kaiser PK, Tasaka Y, Minami M. Determination of residual strength parameters of jointed rock mass using the GSI system. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2007;44:247–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2006.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudson JA, Harrison JP. Engineering Rock Mechanics—An Introduction to the Principles. Elsevier; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Q, Jiang BS, Wang SL, Ge XR, Zhang HQ. Elasto-plastic analysis of a circular opening in strain-softening rock mass. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2012;50:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2011.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serafim, J. L. & Pereira, J. P. Considerations of the geomechanics classification of Bieniawski. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Engineering Geology and Underground Construction Vol. 1, 1133–1142 (A.A. Balkema, 1983).

- 31.Read, S. A. L., Richards, L. R. & Perrin, N. D. Application of the Hoek-Brown failure criterion to New Zealand greywacke rocks. In Proceeding of the 9th International Congress on Rock Mechanics. Paris, France, 25–28 August 1999, 655–660 (A.A. Balkema, 1999).

- 32.Hoek E, Diederichs MS. Empirical estimation of rock mass modulus. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2006;43:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2005.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoek E, Brown ET. Practical estimates of rock mass strength. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1997;34(8):1165–1186. doi: 10.1016/S1365-1609(97)80069-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoek E, Brown ET. Underground Excavations in Rock. Institution of Mining and Metallurgy; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basarir H. Analysis of rock-support interaction using numerical and multiple regression modelling. Can. Geotech. J. 2008;45:1–13. doi: 10.1139/T07-053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoek, E. & Marinos, P. Predicting tunnel squeezing problems in weak heterogeneous rock masses. Tunnels Tunnel. Int.32(11), 45–51; 32(12), 34–36 (2000).

- 37.Wilson AH. A method of estimating the closure and strength of lining required in drivages surrounded by a yield zone. International Journal of Rock Mechanics, Mining Sciences and Geomechanics Abstracts, 1980, 17: 349–355. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1980;47:170–178. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yudhbir, R. K., Lemanza, W. & Prinzl, F. An empirical failure criterion for rock masses. In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on Rock Mechanics, Vol. 1, B1–B8 (A.A. Balkema, 1983).

- 39.Kalamaris, G. S. & Bieniawski, Z. T. A rock mass strength concept for coal incorporating the effect of time. In Proceedings of the 8th International Congress on Rock Mechanics, Vol. 1, 295–302 (A.A. Balkema, 1995).

- 40.Sheorey PR. Empirical Rock Failure Criteria. A.A. Balkema; 1997. p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramamurthy T. Stability of rock masses. Indian Geomech. J. 1986;16(1):1–74. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aydan, O. & Dalgic, S. Prediction of deformation behaviour of 3-lanes Bolu tunnels through squeezing rocks of North Anatolian fault zone (NAFZ). In Proceedings of the Regional Symposium on Sedimentary Rock Engineering, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–22, November 1998 (Public Construction Commission of Taiwan, 1998).

- 43.Trueman, R. An Evaluation of Strata Support Techniques in Dual Life Gateroads (Ph.D. thesis). (University of Wales, 1988).

- 44.Park KH, Kim YJ. Analytical solution for a circular opening in an elastic-brittle-plastic rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2006;43:616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2005.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.