Abstract

The aim of This study was to assess the concentration of potential toxic elements (PTEs) in wheat, flour of Sangak, and Lavash bread samples and the possible effect of the milling process due to a depreciation of the device. Levels of PTEs in tested samples (n = 270) from 10 factories in Iran were determined by ICP-OES (inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry). In addition, the associated human health risk due to consumption of wheat, Sangak and Lavash bread flours in adults and children was estimated. In this approach, percentile 95% hazard quotient (HQ), Hazard index (HI), and Total Hazard Index (THI) was used as a symptom for endangering the consumer people health. A significant difference was detected in Ni concentration between wheat and two brands of flours i.e., Sangak and Lavash samples. The PTEs concentration order in the wheat and flour samples was Fe > Zn > Cu > Ni > Cr > Pb > As > Cd, respectively. Consistent with findings, the concentration of PTEs in all samples was less than the permitted limit set by the European Commission and JECFA committee. The non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic human health risk assessment (HRA) was calculated. Bread consumption per capita is 0.45 kg for adults and 0.27 kg for children per day. The results showed that both adults and children groups are not at remarkable health risk for PTEs at mean HQ, HI, THI <1 and ELCR <10E-4, but for HRA at the percentile 95% showed there is HRA of non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic disease for children group (HQ, HI, THI >1 and ELCR >10E-4).

Keywords: Potential toxic elements (PTEs), Wheat, Flour, Monte Carlo simulation, Health risk assessment

Potential toxic elements (PTEs); Wheat, Flour; Monte Carlo simulation; Health risk assessment.

1. Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and wheat flour are some of the main important foodstuffs in many countries [1]. Wheat flour is used to make a variety of confectionery and bakery products. The existence of metallic and potential toxic elements has become a global concern in recent years in the world [2, 3, 4]. It is estimated that more than 90% of exposure to PTEs is due to receiving these compounds through water and food [3]. The contamination of crops with excessive amounts of PTEs such as Nickel (Ni), Arsenic (As), chromium (Cr), Cadmium (Cd), Iron (Fe), Lead (Pb), Zinc (Zn), and Copper (Cu)can mainly originate from either anthropogenic sources and human activities including mining, usage of sewage sludge for irrigation and even the use of fertilizers and pesticides [1]. The FDA/WHO permissible limit has defined as 0.02, 1.63, 0.41, 0.21, 3 and 27.4 mg per kilogram for chromium, nickel, lead, Cadmium, Copper, and Zinc (mg/kg) in whole grain, respectively [5]. Also, according to the European Commission standard (EU), 0.24 mg/kg is declared for both Pb and Cd in wheat [6, 7, 8]. Though some PTEs including Zn, Cu, and Fe are needed, excessive these metallic trace elements intake may cause adverse health effects.

Given stability, non-biodegradability, and bioaccumulation potential, metallic elements may accumulate in the bone, lung, liver, and kidneys, causing serious damage of organ where they can severely disrupt the normal biological function of vital organs and glands [9]. The frequent exposure to metallic elements may induce neurotoxicity, mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, teratogenicity, and genotoxicity, as well as injured psychosocial performance, immunological predicaments, and endocrine disorders [10, 11]. Previous studies on the PETs have determined that exposure to high concentrations of metals (Ni, As, Cd, Cr, and Pb) through food can result in numerous health problems, such as skin cancer, dermal lesions, peripheral vascular problems, and peripheral neuropathy [12]. Chronic exposure to Pb can lead to problems such as decreased IQ and growth disorders in children as well as increased higher blood pressure in adults [13]. Also, cadmium can increase the risk of cancers during the lifetime of exposed people such as lung, bladder and prostate cancers. Itai-Itai painful bone disease was also caused by excess recommended amounts of cadmium [3]. Several PTEs, such as Fe, Zn, and Cu are necessary elements of metabolic processes, including enzymes and cytochromes that in an inseparable way linked to the microbiota metabolic function [14]. Mercury and its compounds are a global pollutants that leads to birth defects [15].

Plants and crops can absorb metallic and essential trace elements from plant growth media (soil, water, and air) via plant organs such as roots, leaves, and grains. Heavy metals in polluted air can contaminate water and soil, and plants can also be contaminated in this way [16]. Not only can be crops contaminated during the planting and harvesting time, but elements also can absorb during food processing [14]. Product processing can affect the amount of these PTEs in the final products, such as oil extraction, milling, and baking. Most milling machines are made of hardened steel and alloy of Fe with Ni, chromium, Cu, Mo, and Si [17]. Passing the grains through the milling rollers may increase the metallic trace elements, especially when depreciating. Therefore, it seems that the contamination of some metallic trace elements will increase during the milling process.

On the other hand, to increase the grade extraction (%), the upper layers of wheat grain were removed during milling, so the amount of metallic and essential trace elements could be reduced. Previous studies have proven that the amount of some trace elements decreases during the milling process [17, 18, 19]. Cubadda et al. [20] indicated an average reduction of 31% in Cd and 36% in As concentration of semolina in comparison with the whole grain with the lowest Pb concentration in grain and flour. Ekholm et al. [21] have reported a 2–14 mg/kg concentration of Cu in cereals. Khaniki et al. [22] assessed the amount of Zn as 14.2 mg/kg, 12.1 mg/kg, and 10.7 mg/kg in Sangak, Lavash, and Barbari bread, respectively. In another study, the content of Fe, as the second metal in Sweden's wheat flour and wheat bran, was found between 12.4 and 240.4 mg/kg in bran and 6.76–20.1 mg/kg in wheat flour. Also, a significant reduction of Fe was observed [23].

Considering the high usage of wheat flour in bakery and confectionery products worldwide, especially in Iran, it is necessary to assess the amount of metallic and essential elements in wheat grain and wheat flour. Also, the epidemiological evidence has indicated that only comparing toxic metal concentrations with standard amounts cannot exactly represent the health effects of exposure; consequently, attaining probabilistic human health risk assessment (HRA) is essential to access some new information. The probabilistic health risk assessment allows obtaining maximum information from uncertain and input quantities [24]. Therefore, the aim of the present study follows: (1) in order to determine the metallic and essential trace elements levels (Cd, As, Cr, Pb, Ni, Cu, Zn, and Fe) in 270 samples of wheat grain, Lavash, and Sangak flour (two kinds of flour with different extraction) in Iran (2019) with Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES), (2) to assess the potential health risk trough the Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) model.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Samples collection

All samples were taken from different factories in different areas of Iran (A-J) in 2019. Samples (wheat grain and flour) were collected and stored in clean bags (polythene) based on the protocols of the laboratory for analyses and kept at 4 °C until analysis. Iranian flours are divided into four categories with different grade extraction (%), whole flour (95–100%), Khabazi (85–87%), Star flour (77–81%), and Zeros (72%), which are used for making Sangak bread, Lavash or Taftoon bread, Barbari or fantasy bread and finally cakes or cookies, respectively.

2.2. Sample preparation

The preparation steps were carried out according to Miedico et al. [25]. Briefly, H2O2 (30% v/v) and HNO3 (65% v/v) with a rate of 9:1 (v/v) were poured into the 5 g homogenized samples into a Teflon vessel (Mettler Toledo s.p.a., Novate Milanese, Milan, Italy). Then, samples were placed in a microwave reaction system (Ethos-One; Milestone s.r.l. Sorisole, Bergamo, Italy) with the process schedule including: up to 120 °C in 20 min and constant for 10 min; up to 190 °C (20 min) and constant (20 min); step of cooling for 30 min in order to reach temperature of the room. The digestive solution was filtrated by the Whatman filter paper (NO. 42) and diluted with 20% HNO3 until the lucid solution was attained. After the step of cooling, the solution was poured into a 50 mL volumetric flask up to the mark with deionized water. Finally, samples were kept at 4 °C before analysis.

2.3. Instrumental analysis

The PETs concentration in each sample was determined through the inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Torch type Flared end EOP Torch 2.5 mm). Plasma was constituted of Argon, and RF generator power was 1400 W. The spray chamber and detector were Cyclonic Modified Lichti and CCD, respectively. The sample delivery pump type was a software-controlled, four-channel; peristaltic pump that enables exact sample flows. Other features of the device such as plasma gas flow, nebulizer gas flow, and auxiliary gas flow were 14.5, 0.85, and 0.9 (L/min), respectively. Sample initial stabilization time, rinse time, and uptake time was preflight 45 total, 45, and 240 total seconds, respectively. Time of Delay and time among replicate analyses were zero (0 s). The RF generator frequency was 27.12 MHz (resonance frequency). Also, the speed of the prewash pump (according to rpm) was 60 rpm for 15 s, 30 rpm for 30 s, and time of prewash was 45 s. Finally, the speed of sample injection pump was 30 rpm. The measurement was repeated in triplicates. Instrument parameters, the LOD (limit of detection), and the LOQ (limit of quantification) were used for ICP-OES analysis and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Instrument parameters used for metal analysis.

| Metals | Wavelength (nm) | LOD (μg/L) | LOQ (μg/L) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | 214.438 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.99 |

| Pb | 220.353 | 2.16 | 6.49 | 0.99 |

| As | 189.042 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.99 |

| Ni | 221.648 | 0.94 | 2.82 | 0.99 |

| Cu | 324.754 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 0.99 |

| Zn | 213.9 | 0.27 | 0.81 | 0.99 |

| Fe | 259.941 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 0.99 |

| Cr | 205.618 | 0.46 | 1.38 | 0.99 |

2.4. Calibration standard

Individual stock standard solutions were prepared with the following concentrations: 100, 500, and 1000 ppm. Standard solutions that prepared daily and were added to the blank samples (10 mL), then vortexed for 1 min. The mixed internal standard was applied for the ICP-OES technique to eliminate the matrix effects [26].

2.5. Recovery studies

To investigate the recovery, the spiked blank samples at concentration levels 100, 500, and 1000 ppm were prepared for triplicates and the samples were treated based on the preparation mentioned above. The recoveries were assessed with the spiked calibration curves drawn by the Excel program.

2.6. Recovery, LODs, and LOQs

Table 1 shows the relative standard deviations (%), mean recoveries (according %), LODs, and LOQs (mg/kg) determined using ICP-OES analysis at three levels of spiking. Through this method, the LODs and the LOQs for Pb, Ni, Cu, As, Zn, Fe, Cr, and Cd were calculated in all types of samples, respectively. According to repeatability, all samples gave a relative standard deviation (RSD)that was lower than 20 percent with n equal 3 (n = 3) at each level of spiking.

2.7. Human health risk assessment (HRA)

Health risk assessment (HRA) has 4 main steps are conducted respectively, first step is hazard identification, in this study, all heavy metals carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic effects were investigated by review literature. The second step is a dose-response assessment, in this step effect of increasing heavy metals dose and the amount of adverse effect was investigated. The third step is exposure assessment which is specific to any study area and was identified the individual exposure to the heavy metals, finally the fourth step is risk characterization which can quantify the risk and it's equal to Hazard Quotient (HQ). In this study, the human health risk for Cd, As, Ni, Cr, and Pb via consumption of Lavash and Sangak flour were assessed in children and adults age groups. Although Zn, Cu, and Fe are essential but intake of these metallic trace elements may surpass the capacity of homeostatic controls and produce biological changes and adverse health effects. Accordingly, the health risk assessment of these elements is either conducted. In the risk assessment, the use of average value in risk equations causes uncertainty, therefore for hurdle the uncertainty in the present study used Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) as a probabilistic method in Oracle Crystal Ball software (version 11.1.2.4, Oracle, Inc., USA) [27, 28, 29, 30, 31]. MCS was used for Equation. 1. The number of trails to each HQ was at 10,000 and percentile 95% of the HQ in the MCS model was considered a symptom and bad scenario for the consumer's health risk [32, 33].

2.8. Health risk assessment of non-carcinogenic disease

Exposure to different media such as bread which can include many chemical traces such as heavy metals enables to occur non-carcinogenic adverse effect. In many studies, calculating chronic daily intake (CDI) according to mg/kg developed by Chien et al. was used to calculate the probability of occurring non-carcinogenic effect according to Eq. (1) [24]:

| (1) |

In this equation, C is the PTEs concentration in the bread samples (mg/kg), IR is the daily bread intake during Iranian people (kg/day), exposure frequency (EF) to breads (365 days per year), exposure duration (ED) of different age groups (children = 4 to 19 and adults = 20 to +80 year), BW shows average bodyweight that differs between children and adults of Iranian people, the averaging time (AT) for each age group (ED × EF). All parameters for health risk assessment related to PTEs in the bread are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Values of parameters for health risk assessment related to heavy metals in the breads in deferent age groups.

| Parameters | Unit | Symbol | Distribution | Children | Adults | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bread Intake Rate | kg/d | IR | Lognormal | 0.27 | 0.45 | [34] |

| Exposure Frequency | Days/Year | EF | Uniform | 365 | 365 | [35] |

| Exposure Duration | Year | ED | Uniform | 6 | 70 | [35] |

| Body Weight | kg | BW | Normal | 20 | 70 | [36] |

| Average Time non-carcinogen | Days | AT | Uniform | 2190 | 25550 | [35] |

| Average Time carcinogen | Days | AT | Uniform | 25550 | 25550 | [35] |

For this purpose, in the current study used HQ model for each PTEs was according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). HQ equation shown below [24].

| (2) |

where CDI is the mg of PETs intake per kilogram body weight in a day (mg/kg.day), which is calculated by Eq. (1) [37]. Oral reference dose of PTEs indicated by RfDO. RfDO (mg/kg.day) for Cd, As- inorganic, Ni, Cu, Cr, Fe, Zn, Al and Pb using 0.001, 0.0003, 0.011, 0.04, 0.003, 0.7, 0.3, 1 and 0.0035, respectively [38, 39, 40].

The interpretation for the determined HQ value is: HQ < 1 showns that no noxious health effects due to exposure to the detected contaminant concentrations, whiles HQ value higher than 1 suggests potential adverse health risk of non-carcinogenic disease may incur upon exposure [41].

To take note of metallic trace elements ’risks to gather for adult and children from consumption of Lavash, Sangak flour and other bread which produced by wheat flour separately, four Hazard Index (HI) was calculated using Eq. (3) [42]:

| (3) |

HQi is the HQ individual flour type and age group. For obtaining the Total Hazard Index (THI) in children and adults, Eq. (4) was used [43].

| (4) |

The risk of non-carcinogenic is not likely to happen if HQ, HI, or THI <1, while non-carcinogenic risks are probable if HQ, HI, or THI >1 [42], and can have an adverse effects to human health (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

THI assessment in wheat bread, sangak and lavash bread for children and adults.

2.9. Carcinogenic health risk assessment

In the current study to determine carcinogenic risk assessment of PTEs in the bread, the Excessive Lifetime Cancer Risk (ELCR) was used, which was introduced by the U.S. EPA (Eq. (1)) [24]. To assess carcinogenic risk, CDI was used as Eq. (1) and just there was a diference with non-carcinogen CDI which on compute carcinogenic CDI for all age group AT was equal to ED × 70 (25550). To calculate ELCR the cancer slope factor (CSF) of each PTEs which has carcinogenic property multiple to CDI as below (Eq. (5)), the CSF for As, Pb, Ni, Cr and Cd is 1.5, 8.5, 0.91, 0.5 and 6.1, respectively:

| (5) |

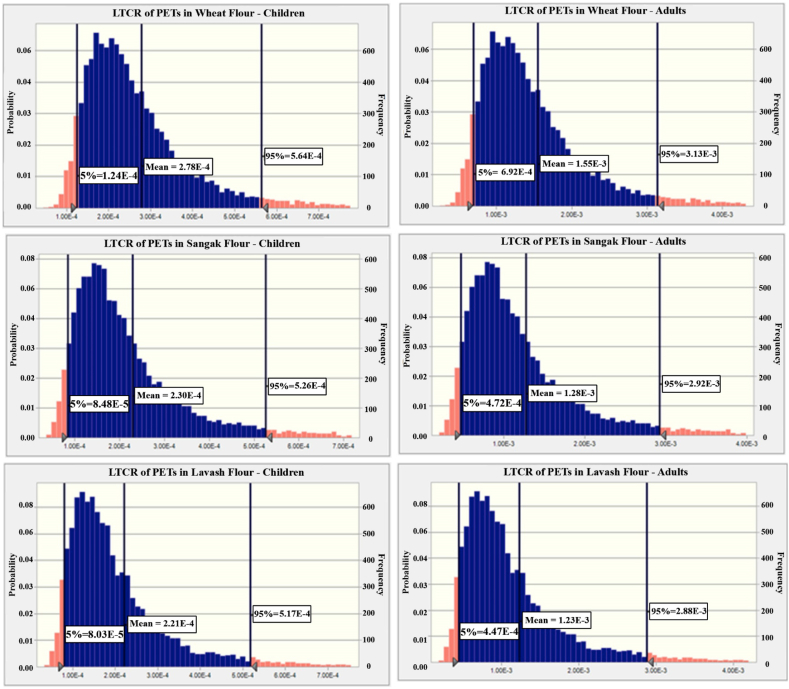

After calculating ELCR the amount of probable carcinogenic risk should compromise with the WHO target, if 95th percentile of simulated ELCR was less than 10−6 it means that there is not any excessive cancer risk related PTEs in the bread and low priority for further consideration, if 95th percentile of ELCR was between 10−4 to 10−6 means that further investigation before either taking action or designing low priority was required and it is WHO target, and if 95th percentile of calculated ELCR or LTCR (lifetime cancer risk) was more than 10−4, it means that further investigation before taking action was required (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

LTCR assessment in wheat bread, sangak and lavash bread for children and adults.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Kolomogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the parametric or nonparametric of the data. All data were normal. Therefore, one-way and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for the results to calculate the significance of the mean difference in the concentrations of metals in samples at 95% confidence level. ANOVA was used to find the difference between the types of flour consumed in 10 regions of Iran and the spatial distribution. For different types of flour and different PTEs concentration, multiple regression was performed was used by SPSS software, version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The concentration of PTEs

Figure 1 summarizes the levels of metallic trace elements and presents a comparison of the PTEs in samples including wheat grain, Sangak, and Lavash flours. These results determine that the lowest and highest average concentration of PTEs were Cd (ND and 0.008 ± 0.001 mg/kg), Pb (ND and 0.017 ± 0.001 mg/kg), As (ND and 0.0006 ± 0.002 mg/kg), Cu (0.330 ± 0.098 and 0.065 ± 0.013 mg/kg) and Zn (0.353 ± 0.162 and 2.145 ± 0.035 mg/kg) in whole samples, respectively. Also, concentration range of Fe, Ni, and Cr was calculated 0.177 ± 0.074 to 02.59 ± 0.516 mg/kg, 0.026 ± 0.004 to 0.615 ± 0.106 mg/kg, and 0.013 ± 0.002 to 1.005 ± 0.025 mg/kg, respectively.

Figure 1.

The concentration of PTEs (mg/kg) in wheat, Sangak and Lavash flour.

3.2. Effect of milling on PTEs

Some studies show the reducing effect due of the milling process on metallic and essential trace elements as well as other contaminant concentrations in wheat and flours [34, 44, 45]. Pastorelli et al. [46], have reported that milling and refining methods lead to a further reduction in the Cd concentration in cereals. Ekholm et al. [21], has shown that concentrations of Cd were found to be < 0.01 in cereals and 0.1 (mg/kg) in wheat bran, which is following the standards. A 31% mean reduction in Cd concentration of semolina was indicated in comparison with the whole grain [20]. Mousavi-Khaneghah et al. [3], reported that the milling could decrease the level of Pb in some cereal grains below the permissible limit. In another study, Khaniki et al. [22], has investigated the Pb level in the different types of Lavash, Sangak, and Taftoon bread marketed in Tehran. The results demonstrated the lowest Pb concentration in Barbari bread (0.27 mg/kg), the highest lead concentration was in Sangak bread, and the mean Pb concentration was below the permissible limit. The highest Pb concentration was shown in the pollard and bran and the lowest Pb concentration was in grain and flour [20]. Albergamo et al. [47], reported that wheat milling resulted in an average reduction of 15%–65% As, due to the elimination of exterior parts of the grains. Oniya et al. [19], described the Cr level in the samples as above the recommended limit of 2.3 (mg/kg). The mean Cr concentration for the different bread ranged from 0.34 to 2.7 mg/kg. It was obtained in Barbaria, Sangak, Lavash, and Baguette as follows 1.3, 0.8, 0.7, and 0.9 (mg/kg), respectively [48]. Ertl and Goessler [49], showed that Cr concentration is affected by milling processing, the mean of which is about twice of grain flour and also indicated that Cr concentration does not go above 0.20 mg per kilogram for both pasta and bread samples, besides 0.047 mg/kg for grains and flour. the findings of the current study were similar to the study of Ertl and Goessler [49]. They evaluated the PTEs levels in pasta, different bread, flour, and grain samples marketed in Austria. Ni concentration range was 0.018–0.91 mg/kg and the concentration of Cu is within a range of 1.0–8.1 mg/kg in flour. But several studies have shown Ni concentrations less than 1 mg/kg [3, 19]. In Ekholm et al. [21] study, Ni concentration of cereals was determined in a range of around 0.06 mg/kg to 1.86 mg/kg.

From the point of nutritional value and health aspect, Reducing or increasing the amount of Cu, Zn, and Fe is a substantial matter. Several studies reported that Cu has a mean concentration between 1.8 to 11 mg/kg in cereal [50, 51]. Ertl and Goessler [49], stated that Cu concentrations in flour were 1.0–8.1 mg/kg. Ekholm et al. [21], reported that Cu concentration in cereals was 2–14 mg/kg. Ludajić et al. [23], reported Zn concentration in the bran is higher 11 times than in the flour. This is in agreement with what is observed by Tóth [17], who showed Zn concentration varied in the range from 17.6 to 33.7 mg/kg in wheat grains. Ertl and Goessler [49], determined ranges of Zn content were from 3.8 - 50 mg/kg in grains and flours, which is like to 7.2–48 mg/kg found in bread and pasta samples. Iron, like zinc, is essential for the body's biological activity, especially hemoglobin and oxygen transport. Nonetheless, over-intake can disturb health effects. Adu et al. [18], determined Fe concentration in a range of 6.020 mg/kg for maize flour and 9.27 mg/kg for AAS. Khaneghah et al. [3], reported that the milling could reduce the concentration of Fe in cereal. Winiarska-Mieczan et al. [52], reported that the Fe has an average content of 17.9 mg/kg ± 10.3 in selected cereal samples marketed in Poland. Therefore, it is important to monitor the concentration of trace metal in flour.

In this study like to previous studies, a decrease in PETs has been observed in the samples due to the milling process. The mean concentration of PETs in wheat, Sangak and Lavash flour was Fe > Zn > Cu > Ni > Cr > Pb > As > Cd, respectively (Figure 1). Also, the general pattern for the distribution of Pb, Cd, As, Cu, and Zn in all factories was wheat > Sangak > Lavash. But there is no clear pattern in Fe concentration in all samples compared to wheat and flours in some factories. The amount of Cr and Ni, like most elements, decreases from wheat to flour, but in the J factory, it has increased in Lavash. The processing procedures play a significant role in toxic element concentration among different cereal-based foods. The maximum and minimum mean values observed that the general pattern for the distribution of Cd, Pb, As, Ni, Cu, Cr, and Zn in a different area of flour were as follows: C > D = J > A = G = I = B > F = H = E, respectively. Based on the results, the outer layer (perisperm, bran, and the aleurone layer) of wheat is richer in metallic and essential trace elements compared with the endosperm and embryo in confirmation of other studies. As a result, the outer layers separated during wheat flour processing that is used for the production of sangak flour with high extraction grade and Lavash flour with low extraction grade, and the concentration of most of the elements was decreased. Milling has a significant effect on the removal of Cd (96%) and As (90.91%), and Pb (73.7%) in the final products (Lavash) with a higher extraction percentage. According to previous studies, different quality of rollers and age of devices release different amounts of trace elements [17, 18], The amount of Ni and Cr, like most elements, decreases from wheat to flour due to the accumulation in outer layers. Considering that a milling machine is made of aluminum with Ni and Cr in some factories, it seems that is one of the reasons for increasing them in the sample analyzed. If the out-of-date devices were applied in factories, the increase in the metallic trace elements release used in the rollers may become meaningful (Table 3). The type of alloy used, the age of the device, and the amount of depreciation can be important factors that have received little attention in food safety [53].

Table 3.

The highest concentration of PETs (mg/kg) and the relationship with the type of alloy used and depreciation in the milling roller.

| metals | Zn | Fe | Cr | Cu | Ni | As | Pb | Cd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depreciation of the device (year) | Under 5 | Under 15 | Under 15 | Under 5 | Under 15 | Under 15 | Under 5 | Under 15 |

| Metal used in construction | Steel | Iron | Aluminum with chrome and nickel rollers | Steel | Aluminum with chrome and nickel rollers | Steel | Steel | Steel |

| Factory code | I | G | J | I | J | D | I | C |

| Maximum value | 2.14 | 2.77 | 1.01 | 0.33 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.09 |

| Sample | Wheat | Lavash | Lavash | Wheat | Lavash | Wheat | Wheat | Wheat |

Besides the above factors, for the essential elements such as Fe, Zn, and Cu the fortification process should also be considered. Among the nutrients, the highest decrease in the final product was detected in Cu (50.96%) and then in Zn [48]. The obtained results show that Fe content ranged from 0.17–2.77 mg/kg in wheat flour. Based on data analysis, the average difference is significant (P < 0.05) and the quantities of all PETs in samples did not exceed the maximum permitted values established by FAO/WHO [54], and European Commission [8, 55]. In some factories, the milling machine can be produced from iron with molybdenum, nickel, chromium, copper, and silicon. Thus, leaching of Ni, Cr, and Fe may occur from stainless steel utensils into food [18]. As well, fortification in some factories has increased the amount of Fe in Lavash, (G factory) and the very high iron content of the flour samples demonstrated a fortification process because of the health benefit. In the present research, Lavash flour was fortified in some factories due to their labeling information.

In the study of Feyzi et al. In 2016 in Shahrekord, a total of 40 bread samples were collected from Shahrekord, and data analyzed by ICP-OES, showed the average levels of As, Zn, Hg, Cd, Pb, Ni, Fe, and Cu in Lavash bread samples were 12.5, 30316, 4.38, 9.48, 931.2, 98.03, 2324, and 14286 μg/kg, respectively. In addition, Pb concentration was higher than the maximum permissible content, which was probably related to the industrial plant activities and machines around farms [56]. According to the results, the high content of daily consumption of chromium, lead, cadmium, and mercury in bread causes adverse health effects on people. Therefore, it is essential to prevent the entry of PTEs into wheat, bread, rice, and other agricultural products in the stages of cultivation, harvesting and milling, storing flour and baking bread [48]. The level of nickel in flat breads was higher than in other cases. In a study conducted in Romania, the lead content of wheat bread was 0.22 based on mg/kg [57]. The amount of lead heavy metal in Barbaria bread samples was less than the average concentration in Sangak bread samples, which may be related to wheat flour contamination and bread production [22].

Wheat may be contaminated with PET during its growing season. Subsequently, these metals will be transferred to flour prepared from contaminated wheat and then to bread samples [58]. Wheat seeds, bran, and Aleurone are richer in metals and minerals compared to endosperm. So, About 61 percent of all mineral materials are in the Aleurone layer of grain [59]. Aleurone separation in wheat flour, which is used to prepare Barbari, Lavash, and Taftoon bread, a significant PTEs concentration reduction in these bread compared to Sangak bread was observed [48, 60]. Transport of PTEs through road traffic, movement of wind and water-soluble materials suspended in the streets to agricultural fields in the city, as well as atmospheric diffusion and precipitation and ion adsorption of soluble metals on the surface, ground agriculture, and water resources can increase the heavy metals concentration, especially Pb, Cd, and Cu in this way in the samples [53, 61].

In general, food poisoning due to PTEs often occurs for three reasons, including environmental pollution, accidental occurrence, and accidental inclusion pending processing or second contamination during food storage or production [62]. In a study in Turkey, survey research showed that there was metal contamination in a pasta factory, and in wheat samples in the pasta production process, the amount of cadmium increased, which indicates contamination in the pasta production and processing stage [63]. In general, possible sources of contamination of flat breads (Lavash, Barbaria, Taftoon, and Sangak) with PTEs can include the wheat semolina stage, which is contaminated with environmental contaminants. In the next stage, which is the addition of water, salt, baking soda, and yeast, contamination occurs due to the contamination of the ingredients of bread dough with various PTEs. In the mixing and kneading stage, preparing bread dough and shaping due to contact with surfaces contaminated with heavy metals, in the baking stage due to air pollution and fuel consumption, and in the packaging and consumption stage by individuals in order to the heavy metals present in materials used for packaging and environmental pollution occur [64, 65]. Removal of PTEs sources in the step of production and old equipment replacement can reduce the lead concentration [66, 67, 68, 69]. In general, the location of bakeries inside the city and near the industrial and densely populated areas of the city are very important for pollution problems [45, 48, 53]. It is notable, concentration of PETs in bread in other studies was higher than the flour and wheat of these samples due to reasons that were said above [45].

3.3. Probabilistic human health risk

Calculated percentile 95% of HQ for As, Cd, Ni, Cu, Cr, Fe, Zn, and Pb in adult and children's consumers of Lavash and Sangak flour in Iran was shown in Figure 2. The rank order of metallic trace elements according to HQ for adult consumers of Lavash was As > Ni > Cd > Cu ≅ Fe ≅ Zn > Cr > Pb. While for Sangak was As ≅ Ni ≅ Cd > Zn ≅ Cu > Fe > Cr > Pb. The rank order of measured metallic trace elements based on HQ in children's consumers of Lavash was As > Ni > Cd > Zn > Fe ≅ Cu > Cr > Pb. While for Sangak was As ≅ Ni > Cd > Cu ≅ Fe ≅ Zn > Cr > Pb. HQ in children remains higher than the adult cause of lower BW [42]. Meanwhile, the mean HQ value in both children and adults was lower than 1. Rank order for HI in both adults and children was: Lavash HI, children > Sangak HI, children > Lavash HI, adult > Sangak HI, adult. The mean HI value of Lavash was higher than Sangak in adults and children but lower than 1. The calculated mean THI for adults via consumption of Sangak and Lavash at the same time was 0.18 and for children was 0.75. Therefore, continuous consumption of Lavash and Sangak flour can't cause adverse health effects. However, the cumulative mean HQ from Lavash and Sangak flour in children is near 1 value and needs attention [70].

In the Ghanati et al. study [66], in all samples including sweets, wheat flour, wheat, pasta, and bread the value of HQ of any element is less than one, which is in line with the current study. Lei et al. study [71], assessed the HMs concentrations in wheat flour samples in the historical irrigated area of Northwest China. This study highlighted the wheat flour health risks due to consumption of it by both children and adults. Results showed that metallic trace elements did not make non-carcinogenic risk in the studied area in order to HI was lesser than 1; except for children in Jing yang county; carcinogenic risk for Cd concentration was obtained, which showed a potential adverse human health risk for consumers. In the preparation of bread, flour is the main raw material but also water used that may contain metallic trace elements. On the other side, processing equipment also could add metallic trace elements [72].

3.4. Uncertainty analysis

In the risk assessment methods uncertainty analysis is necessary to consider the fact that there are some differences between humans and animals (some risk assessment parameters obtain from animal experiments), there are some differences between human which lives in the same community, also certainty analysis can cover the gape of the researches and help to researchers. In this study, as shown in Figure 2 the THI of PTEs in wheat and different flours for bread types by considering appropriate confidence intervals (95%) were evaluated by Oracle Crystal Ball software (version 11.1.2.4.850) with 10000 iterations [73]. In the assessment of health risk, all actions should be considered the conservative situation, so in the present study, 95th percentile is considered as an action cut point. To assess non-carcinogenic by MSC, Eqs. (1) to (4) was used. Figure 2 shows that 95th percentile of simulated THI in the children group for the wheat grain, Sangak and Lavash were 1.42, 1.41 and 1.44, respectively, all of them were more than one (THI>1) so for this age group, the identified PTEs concentration was threaten human health and can have some adverse effect subsequently. Also, Figure 2 shows that 95th percentile of simulated THI in the adult group for the wheat grain, Sangak, and Lavash were 0.69, 0.67, and 0.68, respectively, and because all THI in adults was less than one (THI < 1) so there was not any threat agent for human health.

To assess carcinogenic properties by MSC considering Eq. (1) and Eq. (5) was used, the results that revealed in Figure 3 demonstrated that among the children group the 95th percentile of simulated ELCR for the wheat grain, Sangak and Lavash was 5.64E-04, 5.26E-04 and 5.17E-04 respectively, which all of them there were in WHO target (1E-04 < ELCR < 1E-06), so further investigation before either taking action or designing low priority was required. Also, Figure 3 shows that 95th percentile of simulated ELCR in the adult for the wheat grain, Sangak and Lavash were 3.13E-03, 2.99E-03 and 2.88E-03, respectively, so further investigation before taking action was required. The amount of simulated ELCR in adults was more than in children because intake rate and exposure duration were more than children, whereas body weight can reduce the risk but the effect of this parameter in assessed carcinogenic property was insignificant, so before any action more investigation and precautions were required.

4. Conclusion

In this study, the PTEs concentrations were determined in wheat, Lavash, and Sangak flours. The level of all metallic and essential trace elements was lesser than the FDA/WHO and standard permissible limits of European Commission. The highest PTEs concentration was observed in wheat samples and it was decreased by milling and reduction of the grade extraction (%). For the total mean concentration of Ni, Cr, and Fe among the different wheat and flour samples, the difference was significant. The MCS method for health risk assessment indicated that risk of carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic disease for adults is at Safe health risk associated with PTEs due to the wheat, Lavash and Sangak flour ingestion (percentile 95% of HQ, HI, THI <1, and ELCR<10E-4). But, for children, health risk assessment via the MCS method indicated that risk of both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic diseases for them are concerned and exceeded the permissible limit of health risk associated with PTEs due to the ingestion of wheat, Lavash, and Sangak flour of bread (percentile 95% of HQ, HI, THI >1 and ELCR> 10E-4). So, regular quality control of wheat flour is necessary in factories in order to provide safe and healthy foodstuffs and prevent the PTEs presence in the chain of food. Examining all the stages of the milling separately and the impact of each stage can be evaluated in future studies. There may also be a lack of attention to developing protocols to periodically control devices.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Mohadeseh Pirhadi; Shahrokh Nazmara: Performed the experiments.

Mahsa Alikord; Gholamreza Jahed Khaniki; Ayub Ebadi Fathabad: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Behrouz Tajdar-oranj; Mohammad Rezvani Ghalhari: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Parisa Sadighara: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (project No. IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1397.300).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Yaradua A., Alhassan A., Saulawa L., Nasir A., Matazu K., Usman A., Idi A., Muhammad I., Mohammad A. Evaluation of health effect of some selected heavy metals in maize cultivated in Katsina state, North west Nigeria. Asian Plant Res. J. 2019:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fakhri Y., Abtahi M., Atamaleki A., Raoofi A., Atabati H., Asadi A., Miri A., Shamloo E., Alinejad A., Keramati H. The concentration of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in honey: a global systematic review and meta-analysis and risk assessment. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019;91:498–506. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khaneghah A.M., Fakhri Y., Nematollahi A., Pirhadi M. Potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in cereal-based foods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020;96:30–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terzano R., Rascio I., Allegretta I., Porfido C., Spagnuolo M., Khanghahi M.Y., Crecchio C., Sakellariadou F., Gattullo C.E. Fire effects on the distribution and bioavailability of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in agricultural soils. Chemosphere. 2021;281 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaafarzadeh N., Panahi Fard M., Jorfi S., Zahedi A., Feizi R. Non-carcinogenic risk assessment of Cr and Pb in vegetables grown in the industrial area in the southwest of Iran using Monte Carlo Simulation approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2022;16:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahimi M., Rahimi G., Ebrahimi E., Moradi S. Assessing the distribution of cadmium under different land-use types and its effect on human health in different gender and age groups. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2021;28:49258–49267. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-12881-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hossain M., Badawy S., El-Motaium R., Abdel-Lattif H., Ghorab E.-S.M. Risk assessment of lead distribution in soils, rice (Oryza sativa L.) and wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in Damietta Governorate, Egypt. J Environ Sci Curr Res. 2021;4:2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Commission E. In: Commission Regulation. Union O.J.E., editor. 2006. , setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. (EC) No 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dallatu Y.A., Shallangwa G.A., Ibrahim W.A. Effect of milling on the level of heavy metal contamination of some Nigerian foodstuffs. Int. J. Chem. Mat. Environ. Res. 2016;3:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rani R., Sharma P., Kumar R., Hajam Y.A. Bacterial Fish Diseases. Elsevier; 2022. Effects of heavy metals and pesticides on fish; pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yazdanfar N., Vakili Saatloo N., Sadighara P. Contamination of potentially toxic metals in children’s toys marketed in Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2022:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-20720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miranzadeh M.B., Mostafaii G., Kafaei R., Rezvani Ghalhari M., Atoof F., Hoseindoost G., Karamali F. Determination of heavy metals in cream foundations and assessment of their dermal sensitivity, carcinogenicity, and non-carcinogenicity. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shokri S., Abdoli N., Sadighara P., Mahvi A.H., Esrafili A., Gholami M., Jannat B., Yousefi M. Risk assessment of heavy metals consumption through onion on human health in Iran. Food Chem. X. 2022;14 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rai P.K., Lee S.S., Zhang M., Tsang Y.F., Kim K.-H. Heavy metals in food crops: health risks, fate, mechanisms, and management. Environ. Int. 2019;125:365–385. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amoli J.S., Barin A., Ebrahimi-Rad M., Sadighara P. Cell damage through pentose phosphate pathway in fetus fibroblast cells exposed to methyl mercury. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2011;31:685–689. doi: 10.1002/jat.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y., Zhou S., Jia Z., Liu K., Wang G. Temporal and spatial distributions and sources of heavy metals in atmospheric deposition in western Taihu Lake, China. Environ. Pollut. 2021;284 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tóth B., van Biljon A., Labuschagne M. 2018. Effects of Low Nitrogen and Low Phosphorus Stress on Iron, Zinc and Phytic Acid Content in Two Spring Bread Wheat Cultivars. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adu J.K., Fafanyo D., Orman E., Ayensu I., Amengor C.D., Kwofie S. Assessing metal contaminants in milled maize products available on the Ghanaian market with atomic absorption spectrometry and instrumental neutron activation analyser techniques. Food Control. 2020;109 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oniya E.O., Olubi O.E., Ibitoye A., Agbi J.I., Agbeni S.K., Faweya E.B. Effect of milling equipment on the level of heavy metal content of foodstuff. Phys. Sci. Int. J. 2018;20:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cubadda F., Raggi A., Zanasi F., Carcea M. From durum wheat to pasta: effect of technological processing on the levels of arsenic, cadmium, lead and nickel--a pilot study. Food Addit. Contam. 2003;20:353–360. doi: 10.1080/0265203031000121996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekholm P., Reinivuo H., Mattila P., Pakkala H., Koponen J., Happonen A., Hellström J., Ovaskainen M.-L. Changes in the mineral and trace element contents of cereals, fruits and vegetables in Finland. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2007;20:487–495. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khaniki G.R.J., Yunesian M., Mahvi A.H., Nazmara S. Trace metal contaminants in Iranian flat breads. J. Agric. Soc. Sci. 2005;1:301–303. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludajic G.I., Pezo L.L., Filipovic J.S., Filipovic V.S., Kosanic N.Z. Determination of essential and toxic elements in products of milling wheat. Hem. Ind. 2016;70:707–715. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chien L.-C., Hung T.-C., Choang K.-Y., Yeh C.-Y., Meng P.-J., Shieh M.-J., Han B.-C. Daily intake of TBT, Cu, Zn, Cd and as for fishermen in Taiwan. Sci. Total Environ. 2002;285:177–185. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(01)00916-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miedico O., Pompa C., Tancredi C., Cera A., Pellegrino E., Tarallo M., Chiaravalle A.E. Characterisation and chemometric evaluation of 21 trace elements in three edible seaweed species imported from south-east Asia. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017;64:188–197. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Correia F.O., Silva D.S., Costa S.S.L., Silva I.K.V., da Silva D.R., José do Patrocínio H.A., Garcia C.A., Maranhao T.d.A., Passos E.A., Araujo R.G. Optimization of microwave digestion and inductively coupled plasma-based methods to characterize cassava, corn and wheat flours using chemometrics. Microchem. J. 2017;135:190–198. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tajdar-Oranj B., Shariatifar N., Alimohammadi M., Peivasteh-Roudsari L., Khaniki G.J., Fakhri Y., Mousavi Khaneghah A. The concentration of heavy metals in noodle samples from Iran’s market: probabilistic health risk assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018;25:30928–30937. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3030-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ru Q.-M., Feng Q., He J.-Z. Risk assessment of heavy metals in honey consumed in Zhejiang province, southeastern China. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013;53:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fathabad A.E., Shariatifar N., Moazzen M., Nazmara S., Fakhri Y., Alimohammadi M., Azari A., Khaneghah A.M. Determination of heavy metal content of processed fruit products from Tehran's market using ICP-OES: a risk assessment study. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018;115:436–446. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fathabad A.E., Tajik H., Najafi M.L., Jafari K., Khaneghah A.M., Fakhri Y., Conti G.O., Miri M. The concentration of the potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in the muscle of fishes collected from Caspian Sea: a health risk assessment study. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021;154 doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2021.112349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jafari K., Fathabad A.E., Fakhri Y., Shamsaei M., Miri M., Farahmandfar R., Khaneghah A.M. Aflatoxin M1 in traditional and industrial pasteurized milk samples from Tiran County, Isfahan Province: a probabilistic health risk assessment. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2021;33:103–116. [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Voet H., de Mul A., van Klaveren J.D. A probabilistic model for simultaneous exposure to multiple compounds from food and its use for risk–benefit assessment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007;45:1496–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fathabad A.E., Jafari K., Tajik H., Behmanesh M., Shariatifar N., Mirahmadi S.S., Conti G.O., Miri M. Comparing dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls in most consumed fish species of the Caspian Sea. Environ. Res. 2020;180 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.108878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pirsaheb M., Fakhri Y., Karami M., Akbarzadeh R., Safaei Z., Fatahi N., Sillanpää M., Asadi A. Measurement of permethrin, deltamethrin and malathion pesticide residues in the wheat flour and breads and probabilistic health risk assessment: a case study in Kermanshah, Iran. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2019;99:1353–1364. [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S.E.P. Agency . National Center for Environmental Assessment; Washington, DC: 2011. Exposure Factors Handbook: 2011 Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rezvani Ghalhari M., Kalteh S., Asgari Tarazooj F., Zeraatkar A., Mahvi A.H. Health risk assessment of nitrate and fluoride in bottled water: a case study of Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2021;28:48955–48966. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-14027-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nazaroff W., Alvarez-Cohen L. John Willey & Sons, in, Inc; 2001. Environmental Engineering Science. [Google Scholar]

- 38.USEPA . National Center for Environmental Assessment.; 2019. Integrated Risk Information System.https://www.epa.gov/iris U.S.E.P. Agency. (Ed.), U.S.Environmental Protection Agency. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghaffari H.R., Kamari Z., Ranaei V., Pilevar Z., Akbari M., Moridi M., Khedher K.M., Fakhri Y., Khaneghah A.M. The concentration of potentially hazardous elements (PHEs) in drinking water and non-carcinogenic risk assessment: a case study in Bandar Abbas, Iran. Environ. Res. 2021;201 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Florian D., Barnes R., Knapp G. Comparison of microwave-assisted acid leaching techniques for the determination of heavy metals in sediments, soils, and sludges. Fresen. J. Anal. Chem. 1998;362:558–565. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raza M., Hussain F., Lee J.-Y., Shakoor M.B., Kwon K.D. Groundwater status in Pakistan: a review of contamination, health risks, and potential needs. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;47:1713–1762. [Google Scholar]

- 42.USEPA Exposure Factors Handbook 2011 Edition (Final) 2011. http://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/risk/recordisplay.cfm?deid=236252

- 43.Shi W., Zhang F., Zhang X., Su G., Wei S., Liu H., Cheng S., Yu H. Identification of trace organic pollutants in freshwater sources in Eastern China and estimation of their associated human health risks. Ecotoxicology. 2011;20:1099–1106. doi: 10.1007/s10646-011-0671-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Irogbeyi L., Nweke I., Akuodor G., Prince U., Ebere A. Evaluation of levels of potassium bromate and some heavy metals in bread and wheat flour sold in aba metropolis, south eastern Nigeria. Asia Pacif. J. Med. Toxicol. 2019;8:71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghasemi S., Hashemi M., Gholian Aval M., Khanzadi S., Safarian M., Orooji A., Tavakoly Sany S.B. Effect of baking methods types on residues of heavy metals in the different breads produced with wheat flour in Iran: a case study of mashhad. J. Chem. Heal. Risks. 2022;12:105–113. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pastorelli A.A., Angeletti R., Binato G., Mariani M.B., Cibin V., Morelli S., Ciardullo S., Stacchini P. Exposure to cadmium through Italian rice (Oryza sativa L.): consumption and implications for human health. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018;69:115–121. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albergamo A., Bua G.D., Rotondo A., Bartolomeo G., Annuario G., Costa R., Dugo G. Transfer of major and trace elements along the “farm-to-fork” chain of different whole grain products. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018;66:212–220. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naghipour D., Amouei A., Nazmara S. A comparative evaluation of heavy metals in the different breads in Iran: a case study of rasht city. Health Scope. 2014;3 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ertl K., Goessler W. Grains, whole flour, white flour, and some final goods: an elemental comparison. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018;244:2065–2075. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hammed W.A., Koki I.B. Determination of lead and cadmium content in some selected processed wheat flour. Int. J. Chem. Mat. Environ. Res. 2016;3:56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Podio N.S., Baroni M.V., Badini R.l.G., Inga M., Ostera H.c.A., Cagnoni M., Gautier E.A., García P.P., Hoogewerff J., Wunderlin D.A. Elemental and isotopic fingerprint of Argentinean wheat. Matching soil, water, and crop composition to differentiate provenance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:3763–3773. doi: 10.1021/jf305258r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winiarska-Mieczan A., Kowalczuk-Vasilev E., Kwiatkowska K., Kwiecień M., Baranowska-Wójcik E., Kiczorowska B., Klebaniuk R., Samolińska W. Dietary intake and content of Cu, Mn, Fe, and Zn in selected cereal products marketed in Poland. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019;187:568–578. doi: 10.1007/s12011-018-1384-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ashot D.P., Sergey A.H., Radik M.B., Arthur S.S., Mantovani A. Risk assessment of dietary exposure to potentially toxic trace elements in emerging countries: a pilot study on intake via flour-based products in Yerevan, Armenia. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020;146 doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.J. F. W. C. A. Commission. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pirhadi M., Shariatifar N., Bahmani M., Manouchehri A. Heavy metals in wheat grain and its impact on human health: a mini-review. J. Chem. Heal. Risks. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feyzi Y., Malekirad A., Fazilati M., Salavati H., Habibollahi S., Rezaei M. Metals that are important for food safety control of bread product. Adv. Bio. Res. 2017;8 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nicoleta M., Ramona L., Rita G., Muntean E. Institiute of Public Health Nopoca; Romania: 1996. Heavy Metals Content in Some Food Products. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moroșan E., Secareanu A.A., Musuc A.M., Mititelu M., Ioniță A.C., Ozon E.A., Raducan I.D., Rusu A.I., Dărăban A.M., Karampelas O. Comparative quality assessment of five bread wheat and five barley cultivars grown in Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph191711114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoseney R.C. American Association of Cereal Chemists, Inc.; St. Paul: 1994. Principles of Cereal Science and Technology; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharifovich K.N., Sanokulovich R.K. Udk 664.8 baking properties and quality expertise wheat flour. Europ. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020;7:6333–6340. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kessel I., O’Connor J.T. Springer; 2013. Getting the lead Out: the Complete Resource on How to Prevent and Cope with lead Poisoning. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jawad I., Allafaji S.H. The levels of trace metals contaminants in wheat grains, flours and breads in Iraq. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2012;6:88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Demirozu B., Saldamli I. Metallic contamination problem in a pasta production plant. Turk. J. Eng. Environ. Sci. 2002;26:361–366. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sezer B., Unuvar A., Boyaci I.H., Köksel H. Rapid discrimination of authenticity in wheat flour and pasta samples using LIBS. J. Cereal. Sci. 2022;104 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harrington S.A., Connorton J.M., Nyangoma N.I., McNelly R., Morgan Y.M., Aslam M.F., Sharp P.A., Johnson A.A., Uauy C., Balk J. bioRxiv; 2022. A Two-Gene Strategy Increases the Iron and Zinc Concentration of Wheat Flour and Improves mineral Bioaccesibility for Human Nutrition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghanati K., Zayeri F., Hosseini H. Potential health risk assessment of different heavy metals in wheat products. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. (IJPR): Int. J. Phys. Res. 2019;18:2093. doi: 10.22037/ijpr.2019.1100865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.T. Bossou, D.S. Dabade, O.D. Bello, J. Dossou, Risk assessment of lead in wheat flour bread consumed in Benin, J. Appl. Biosci., 164 17056–17064.

- 68.Abou-Zaid F.O., El-Sayed E.Z., Abu-Shama H.S. Dried date powder addition in balady bread processing and its effect on the hepatotoxicity induced by some heavy metals. Egypt. J. Food Sci. 2022;50:61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Basaran B. Comparison of heavy metal levels and health risk assessment of different bread types marketed in Turkey. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022;108 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Charles I.A., Ogbolosingha A.J., Afia I.U. Health risk assessment of instant noodles commonly consumed in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2018;25:2580–2587. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0583-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lei L., Liang D., Yu D., Chen Y., Song W., Li J. Human health risk assessment of heavy metals in the irrigated area of Jinghui, Shaanxi, China, in terms of wheat flour consumption. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015;187:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-4884-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mohammadi F., Marti A., Nayebzadeh K., Hosseini S.M., Tajdar-Oranj B., Jazaeri S. Effect of washing, soaking and pH in combination with ultrasound on enzymatic rancidity, phytic acid, heavy metals and coliforms of rice bran. Food Chem. 2021;334 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bazeli J., Ghalehaskar S., Morovati M., Soleimani H., Masoumi S., Rahmani Sani A., Saghi M.H., Rastegar A. Health risk assessment techniques to evaluate non-carcinogenic human health risk due to fluoride, nitrite and nitrate using Monte Carlo simulation and sensitivity analysis in Groundwater of Khaf County, Iran. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2020:1–21. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.