Abstract

Background:

Female representation varies geographically among orthopaedic residency programs, with the southern region of the United States reported as having relatively lower rates of female orthopaedic surgeons.

Purpose:

To determine the gender and geographic distributions of US-based orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons and analyze geographic patterns between their training locations and present-day practices.

Study Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Methods:

American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine (AOSSM) fellowship completion data from the 2016-2021 academic years were analyzed with regard to gender and fellowship location. Medical school, residency, and current practice locations were obtained via internet searches for all individuals identified within the databases. Locations were categorized into regions based on the US Census Bureau definitions. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed on the data.

Results:

A total of 1268 sports orthopaedic surgeons who graduated fellowship from 2016 to 2021 were analyzed: 141 (11%) were female and 1127 (89%) were male. The percentage of female sports medicine surgeons in fellowship remained constant (11%-12%) from 2016 to 2021. On average, the annual percentage of female orthopaedic sports medicine fellows was 7.2% in the South, 10.4% in the West, 14.2% in the Midwest, and 14.7% in the Northeast. Based on the orthopaedic sports medicine fellowship graduates from 2016 to 2021, the mean percentage of current female orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons in practice was 7.4% in the South, 11.7% in the Northeast, 12.8% in the Midwest, and 14.4% in the West.

Conclusion:

Approximately 11% of our sample was female; however, this percentage varied heavily by region, with the southern region having significantly lower rates of gender diversity.

Keywords: gender diversity, women in orthopaedics, demographics, orthopaedic sports medicine fellows

Fifty years ago, women accounted for <10% of medical school matriculants in the United States; now, they represent over half of enrolled medical students. 22 Despite this increase, women remain considerably underrepresented in surgery. While general surgery residency leads the way with women encompassing 41% of residents, in the United States, orthopaedics has the lowest percentage at 15%. 4 Additionally, from 2014 to 2019, 29% of US orthopaedic residency programs had <1 female resident. 25 On a global level, 1 study that evaluated 31 countries in 2019 found that the mean percentage of female orthopaedic surgeons per country was 5.5%. 14 Furthermore, in 2019 women accounted for only 6.5% of fellows of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 9

Various reasons have been cited for these gender biases. Studies have indicated that female mentorship and clinical exposure significantly influence female interest and subsequent application rates to orthopaedic residency programs. 13,19 Another critical factor appears to be the presence or lack thereof of mandatory preclinical musculoskeletal instruction, with 1 study demonstrating a 75% increase in female orthopaedic residency applications at institutions that mandate such instruction. 2

Despite these challenges, improving gender parity in orthopaedics remains a paramount concern. As such, 2 pipeline initiatives, the Petty Initiative and Nth Dimensions, were established to promote early orthopaedic exposure to improve gender diversity. 15,16 Furthermore, the Ruth Jackson Society was founded as a support and networking group for female orthopaedic surgeons, with the goal to provide resources to promote and increase diversity and inclusion in orthopaedic surgery and leadership roles. 20,24 A gender-diverse orthopaedic community may improve patient outcomes, as others have shown that many patients prefer physicians of similar race and sex. 10,17 This is especially important since women have been found to have higher rates of orthopaedic intervention. 5 Additionally, increased diversity may improve the training experience of orthopaedic residents by increasing cultural competency and promoting an inclusive environment. 8,21

Prior studies examining gender diversity among orthopaedic training programs have shown that female representation varies geographically, with the South training fewer women than the West or Northeast regions. 7,18 The purpose of our study was to determine the gender and geographic distributions of American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine (AOSSM) fellowship–trained surgeons and analyze geographic patterns among the locations of their medical schools, residencies, fellowships, and present-day practices in the United States.We hypothesized that there would be significant variation in female representation of orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons by geographic region.

Methods

Study Design

In March 2021, AOSSM provided an up-to-date list of demographic data for 2016-2021 AOSSM fellowship–trained surgeons. This list contained the fellow’s full name, gender, fellowship institution, and year of fellowship completion. From these data, we conducted internet searches for each individual’s location of medical school, residency, and current practice. Demographic data were collected from a physician’s front-facing biographical webpage or current hospital affiliation. When this was not available, the most current career networking and directory websites were used (eg, LinkedIn, Doximity, Healthgrades, WebMD, Vitals). Information from these online sources, such as fellowship location and completion date, was cross-referenced among them and with AOSSM-provided data to ensure accuracy.

If insufficient data were found online to ensure accuracy, no data from the online search were recorded, and the location was recorded as “unknown.” Those whose locations were unknown and those who were still in fellowship during the 2020-2021 academic year were not included in these calculations. All locations outside the United States were documented as “international.” If multiple medical school and/or residency/internship locations were listed on the front-facing biographical webpages, only the most recent was designated as the location for that training level. Locations were classified to observe geographic and gender associations on a national level. Locations were also classified into regions as defined according to US Census Bureau definitions 23 :

Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont

Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Ohio, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin

South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia

West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming

Statistical Analysis

Gender diversity was measured with descriptive statistics at all training levels and geographic locations and then averaged over the 6-year period. Descriptive statistics were used to determine physician retention and geographic training flow patterns for men and women. For our study, retention rate—defined by physicians currently practicing at the same geographic region in which they previously trained—was calculated as a percentage, by dividing the number of individuals of a certain gender, region, and training level by the number of current practicing surgeons in that same gender group and region.

A chi-square test was performed to assess for an association among training locations. To do this, locations were cross-tabulated by medical school and residency, residency and fellowship, fellowship and current practice, medical school and current practice, and residency and current practice (R Version 4.2.0). Association was determined to be significant if P < .05.

Results

General Demographics

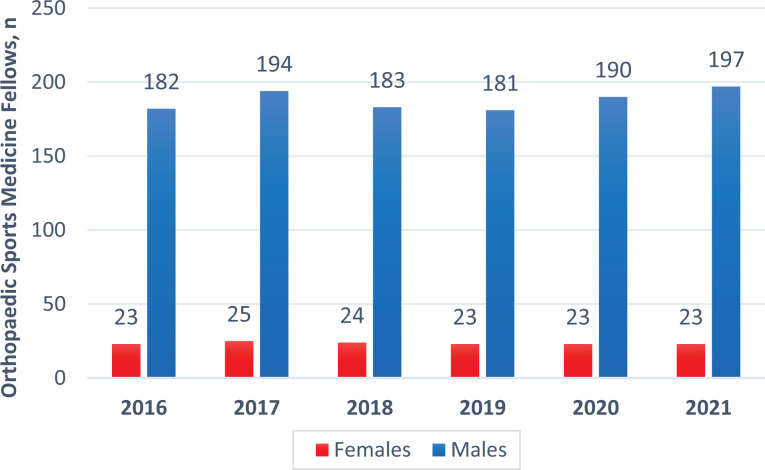

The AOSSM fellowship completion data comprised 1287 AOSSM fellows. After removal of repeats for fellows who completed dual fellowships (in either another field or an additional sports medicine fellowship), 1268 were left: 141 (11%) women and 1127 (89%) men (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of female and male orthopaedic sports medicine fellows between 2016 and 2021 in the United States.

Current Practice

In our sample, 233 individuals were in the process of completing a fellowship; therefore, their future practice location could not be evaluated. Furthermore, 19 were practicing internationally and 87 could not be found. The geographic region with the most current practicing orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons was the South (n = 333), followed by the West (n = 221), Midwest (n = 220), and Northeast (n = 155). On average, the percentage of current practicing female orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons was 7.4% in the South, 11.7% in the Northeast, 12.8% in the Midwest, and 14.4% in the West (Figure 2). Comparing the number of sports surgeons to the general population with congruent gender for each area, the ratio is male-dominant. This difference was most evident in the South, there was 1 female sports surgeon per 2,561,766 females and 1 male sports surgeon per 199,793 males. It was followed by the northeast region, with 1 female sports surgeon per 1,508,875 women and 1 male sports surgeon per 200,838. In the Midwest, there was 1 female sports surgeon per 1,238,232 females and 1 male sports surgeon per 176,137. Lastly, in the West, there was 1 female sports surgeon per 1,227,068 and 1 male sports surgeon per 206,778 males.

Figure 2.

Geographic heat map for rate of female practicing surgeons for each region in the United States.

Fellowship Locations

Between 2016 and 2021, there were 388 AOSSM fellowship positions in the South, 345 in the West, 308 in the Northeast, and 227 in the Midwest. Among all regions combined, female-held fellowship positions stayed constant (11%-12%) during this period. The mean percentage of female fellows per region was 7.2% in the South, 10.4% in the West, 14.2% in the Midwest, and 14.7% in the Northeast.

Residency Locations

A total of 90 physicians completed residency internationally, and the location for 58 could not be found. Of the remaining aspiring orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons, 322 completed residency in the Midwest, 322 in the South, 315 in the Northeast, and 161 in the West. On average, the percentage of female orthopaedic residents who later specialized in sports medicine was 6.8% in the South, 12.1% in the Midwest,12.5% in the West, and 13.9% in the Northeast (Table 1).

Table 1.

Female Representation for Various Regions and Training Levels (2016-2021) a

| Region | Residency | Fellowship | Current Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| South | 6.8 | 7.2 | 7.4 |

| Northeast | 13.9 | 14.7 | 11.7 |

| Midwest | 12.1 | 14.2 | 12.8 |

| West | 12.5 | 10.4 | 14.4 |

a Values are presented as percentages.

Migratory Patterns Between Training and Current Practice Locations

Regarding the rate of male and female physicians who remained in the same geographic region (ie, retention rate) between medical school and current practice, the West region had the highest (76.4%), followed by the South (71.6%), Midwest (58.9%), and Northeast 46.5%) (P < .001). The retention rate from residency to current practice was highest in the West (72.4%) and South (72.4%), followed the Midwest (51.8%) and Northeast (44.8%, P < .001). In terms of the retention rate from fellowship to current practice, the South had the highest (61.8%), followed by the West (51.4%), Midwest (48.1%), and Northeast (32.5%) (P < .001).

For the male cohort alone, the West had the highest retention rate (72.8%) between medical school and current practice, followed by the South (72.8%), Midwest (58.9%), and Northeast (46.4%) (P < .001). The retention rate between residency and current practice was highest in the South (74.5%), followed by the West (72.2%), Midwest (50.2%), and Northeast (44.4%) (P < .001). The retention rates between fellowship and current practice were the lowest. The South had the highest retention rate (63.6%), followed by the Midwest (50.0%), West (49.3%), and Northeast (32.2%) (P < .001). The South and West had the highest retention of physicians among all training levels, while the Northeast had the lowest.

For the female cohort, the retention rate between medical school and current practice regions was highest in the West (69.2%), followed by the South (59.2%), Midwest (58.6%), and Northeast (46.6%) (P < .001). Between residency and current practice, the retention rate was again highest in the West (73.3%), followed by the Midwest (62.5%), Northeast (47.2%), and South (40.0%) (P < .001). For the rates of physicians who remained in the same location between fellowship and current location, the West had the highest (70.3%), followed by the South (41.6%), Midwest (36.6%), and Northeast (35.5%).

Discussion

In this study, we found that significant gender disparities persist in orthopaedic surgery, as only 141 of the 1268 AOSSM fellows (11%) were female. We also found that although the southern region had the largest total number of orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons, it consistently had the lowest percentage of female representation at all training levels and among all sports medicine surgeons. During residency, the southern region had 6.8% female representation as compared with the Midwest (12.1%), West (12.5%), and Northeast (13.9%). During fellowship, the southern region had 7.2% female representation, as opposed to the West (10.4%), Midwest (14.1%), and Northeast (14.7%). As practicing orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons, female representation in the South was 7.4% as compared with the Northeast (11.7%), Midwest (12.8%), and West (14.4%). Although this is a small improvement from the 2010-2014 period, during which approximately 9% of sports medicine fellowship positions were held by women, the proportion of female orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons has remained mostly static. 6 In that regard, this persistent gender gap remains concerning. Therefore, we sought to analyze the gender and geographic distributions for the AOSSM and discuss possible causative factors for any disparities.

Our findings indicate that female representation in orthopaedic sports medicine varied significantly by geographic location. The South consistently had the lowest rates of female representation as compared with the other regions. This difference among regions was significant, as we observed that at each training level, the rate of female representation in the South was commonly half that in the other regions. However, given that the South consistently had one of the largest numbers of total positions, if not the largest, this lower gender diversity did not translate to having the smallest number of women.

These findings are consistent with prior studies that demonstrated lower female representation in southern orthopaedic residencies and orthopaedic surgeons in current practice. 7,18 A factor that could be contributing to this difference is regional retention rates between men and women. For men, the South and Midwest had higher retention rates for residency and fellowship, whereas the Northeast had the lowest. For women, the West had the highest retention rate in all training levels, but the South had one of the lowest for residency.

Prior studies have suggested that these regional differences may be due to either applicant-related factors, such as fewer women applying to southern programs, or program-related biases. 18 Bratescu et al 3 found that a personal history of interest in sports is the top motivation for applying to an orthopaedic sports medicine fellowship but that mentorship is the chief modifiable factor in the decision process. Furthermore, other studies have stated that female mentorship is a key factor among potential female residency applicants and that it also influences fellowship choice. 13,18 However, given the gender disparity observed here, along with studies noting that only 3.3% (3/90) of orthopaedic sports medicine fellowship directors were female, a lack of female mentorship may serve to propagate this disparity. 1 Increasing the availability of female role models who are visible in leadership positions may be one strategy to improve gender parity. 12

These findings have practical clinical applications. Multiple studies have demonstrated that women tend to have a preference for a provider of the same gender and that women have higher rates of orthopaedic surgical interventions. 5,10,11 However, on average, there is 1 female orthopaedic sports medicine surgeon per 1,633,985 women, as opposed to 1 male per 195,887 men: an 8-fold difference. Notably, this discrepancy was most evident in the South, where there was 1 female orthopaedic sports medicine surgeon per 2,561,766 women and 1 male per 199,793 men: a 13-fold difference.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, although the AOSSM-provided fellowship list may be highly accurate, the online search engines used to find remaining training and current practice locations may not be as accurate. Second, although the results of this study mimic the gender disparity within the field of orthopaedics, they are not necessarily generalizable to orthopaedics, given that our sample was entirely composed of those who chose to undergo a sports medicine fellowship. These geographic differences are therefore limited to sports medicine fellowships. Additionally, the current location of all fellows graduating in 2021 is unknown, as the online search occurred before they had graduated. Another limitation is the grouping of geographic regions. We used the census map of the United States, which has been used in literature, but whether that is optimal is a matter of debate. Last, our study evaluated only the geographic locations and gender of orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons. Our study also evaluated only female orthopaedic residents who went into sports medicine, limiting our ability to make any definitive conclusions about the overall field. The factors that contributed to these findings are just speculations. Further studies may investigate if female orthopaedic surgeons choose programs based on program demographics as well as if the extent to which the duration of training in a specific region influences future practice location.

Conclusion

The current study demonstrates the gender disparity within orthopaedic sports medicine as well as the significant differences in female representation among geographic regions within the United States. Although the South had the largest number of orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons, it consistently had the lowest percentage of female representation. Further studies are necessary to examine trends, barriers, and solutions to increase the diversity of the field throughout the nation.

Footnotes

Final revision submitted July 26, 2022; accepted August 7, 2022.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the US government. One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: C.F.J. has received education payments from Arthrex and hospitality payments from Stryker. J.S. has received grant support from Arthrex and education payments from Kairos Surgical and SportsTek Medical. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval was not sought for the present study.

References

- 1. Belk JW, Littlefield CP, Mulcahey MK, McCarty TA, Schlegel TF, McCarty EC. Characteristics of orthopaedic sports medicine fellowship directors. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(2):2325967120985257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bernstein J, Dicaprio MR, Mehta S. The relationship between required medical school instruction in musculoskeletal medicine and application rates to orthopaedic surgery residency programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(10):2335–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bratescu RA, Gardner SS, Jones JM, et al. Which subspecialties do female orthopaedic surgeons choose and why? Identifying the role of mentorship and additional factors in subspecialty choice. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2020;4(1):e19.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2018-2019. JAMA. 2019;322(10):996–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borkhoff CM, Hawker GA, Wright JG. Patient gender affects the referral and recommendation for total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1829–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cannada LK. Women in orthopaedic fellowships: what is their match rate, and what specialties do they choose? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(9):1957–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chapman TR, Zmistowski B, Prestowitz S, Purtill JJ, Chen AF. What is the geographic distribution of women orthopaedic surgeons throughout the United States? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478(7):1529–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):90–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DeMaio M. Making the case (again) for gender equity. AAOS Now. June 1, 2019. https://www.aaos.org/aaosnow/2019/jun/youraaos/youraaos05/

- 10. Derose KP, Hays RD, McCaffrey DF, Baker DW. Does physician gender affect satisfaction of men and women visiting the emergency department? J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(4):218–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dineen HA, Patterson JMM, Eskildsen SM, et al. Gender preferences of patients when selecting orthopaedic providers. Iowa Orthop J. 2019;39(1):203–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hiemstra LA, Wittman T, Mulpuri K, et al. Dissecting disparity: improvements towards gender parity in leadership and on the podium within the Canadian Orthopaedic Association. J ISAKOS. 2019;4:227–232. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hill JF, Yule A, Zurakowski D, Day CS. Residents’ perceptions of sex diversity in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(19):e1441–e1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. International Orthopaedic Diversity Alliance. Diversity in orthopaedics and traumatology: a global perspective. Effort Open Rev. 2020;5(10):743–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lattanza LL, Meszaros-Dearolf L, O’Connor MI, et al. The Perry Initiative’s medical student outreach program recruits women into orthopaedic residency. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(9):1962–1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mason B, Ross WA, Bradford L. Nth dimensions evolution, impact, and recommendations for equity practices in orthopaedics. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2022;30(8):350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Noel OF, Berg A, Onyango N, Mackay DR. Ethnic and gender diversity comparison between surgical patients and caring surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(10):e3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rajani R, Haghshenas V, Abalihi N, Tavakoli EM, Zelle BA. Geographic differences in sex and racial distributions among orthopaedic surgery residencies: programs in the South less likely to train women and minorities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2019;3(2):e004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rohde RS, Wolf JM, Adams JE. Where are the women in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(9):1950–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ruth Jackson Orthopaedic Society. Accessed May 12, 2022. http://www.rjos.org/

- 21. Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, Wilkerson L. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1135–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stewart A. Women have closed med school enrollment gap; others remain. American Academy of Family Physicians. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/news/blogs/leadervoices/entry/20200228lv-diversity.html

- 23. US Census Bureau. 2010. Census regions and divisions of the United States. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-maps/2010/geo/2010-census-regions-and-divisions-of-the-united-states.html

- 24. Vajapey S, Cannada LK, Samora JB. What proportion of women who received funding to attend a Ruth Jackson Orthopaedic Society meeting pursued a career in orthopaedics? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(7):1722–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van Heest AE, Agel J, Samora JB. A 15-year report on the uneven distribution of women in orthopaedic surgery residency training programs in the United States. JB JS Open Access. 2021;6(2):e20.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]