Abstract

Pasteurella aerogenes is known as a commensal bacterium or as an opportunistic pathogen, as well as a primary pathogen found to be involved in abortion cases of humans, swine, and other mammals. Using broad-range DNA probes for bacterial RTX toxin genes, we cloned and subsequently sequenced a new operon named paxCABD encoding the RTX toxin PaxA in P. aerogenes. The pax operon is organized analogous to the classical RTX operons containing the activator gene paxC upstream of the structural toxin gene paxA, which is followed by the secretion protein genes paxB and paxD. The highest sequence similarity of paxA with known RTX toxin genes is found with apxIIIA (82%). PaxA is structurally similar to ApxIIIA and also shows functional analogy to ApxIIIA, since it shows cohemolytic activity with the sphingomyelinase of Staphylococcus aureus, known as the CAMP effect, but is devoid of direct hemolytic activity. In addition, it shows to some extent immunological cross-reactions with ApxIIIA. P. aerogenes isolated from various specimens showed that the pax operon was present in about one-third of the strains. All of the pax-positive strains were specifically related to swine abortion cases or septicemia of newborn piglets. These strains were also shown to produce the PaxA toxin as determined by the CAMP phenomenon, whereas none of the pax-negative strains did. This indicated that the PaxA toxin is involved in the pathogenic potential of P. aerogenes. The examined P. aerogenes isolates were phylogenetically analyzed by 16S rRNA gene (rrs) sequencing in order to confirm their species. Only a small heterogeneity (<0.5%) was observed between the rrs genes of the strains originating from geographically distant farms and isolated at different times.

The gram-negative bacterium Pasteurella aerogenes was first isolated from porcine intestine and described as a gas-producing Pasteurella-like organism (30). Reported cases of isolation in animals have included the buccal flora of wild boars (33), the urine of rabbit, or the uterine cervix discharge of cow (3). In humans P. aerogenes has been isolated from lesions caused by cats, pigs, or wild boar (27, 30, 32).

Clinically, the isolation of P. aerogenes is mainly associated with abortion cases. The first case described in which P. aerogenes was directly involved as a pathogen was an abortion in swine, where it was isolated from several organs of the aborted fetuses (30). At least two additional cases of P. aerogenes-induced abortion in swine have been reported (13, 21). Abortion cases, where P. aerogenes could be responsible, were also reported in other mammals. It was isolated in pure culture from the uterus and peritoneal cavity of a rabbit which died 4 days after abortion (34). Also a human case is described where P. aerogenes could be isolated from a stillborn child and from its mother's vaginal vault (P. Thorsen, B. R. Moller, M. Arpi, A. Bremmelgaard, and W. Fredericksen, Letter, Lancet 343:485–486, 1994). During pregnancy, the mother had been working as an assistant on a pig farm. Other clinical cases are described in swine suffering from various diseases, where P. aerogenes was isolated from the lungs and respiratory system and quite often from intestines with gastroenteritis (3, 30), but its relevance as a primary pathogen in clinical findings other than abortion is doubtful. Despite the description of P. aerogenes as a potential pathogen, nothing is known about its possible virulence factors involved in pathogenicity.

RTX (repeats in the structural toxin) toxins, are a class of pore-forming protein toxins which are often found among various species of Pasteurellaceae and play an important role in pathogenicity (16). They were found in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (ApxIA [20], ApxIIA [8], and ApxIIIA [7]), in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (AaltA [24]), Pasteurella haemolytica (LktA [28]), and P. haemolytica-like (PllktA [6]) and in Actinobacillus suis (AshA [5]). The operons are similarly organized in a CABD pattern where C codes for the activation protein, A encodes the structural toxin, and B and D code for proteins involved in the secretion of the toxin. We have therefore analyzed various strains of P. aerogenes, including strains from abortion cases in swine, for the presence of RTX genes by using a recently developed broad range detection system for this family of toxin genes (26). We describe a new RTX protein and its operon that was found in clinical P. aerogenes isolates and present a functional characterization of this toxin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 13 Pasteurella aerogenes strains consisting of the type strain ATCC 27883T and 12 field isolates were used in this study (Table 1). The field strains were freshly isolated at our diagnostic unit from clinical material of swine. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 2 reference strain ATCC 27089 (S1536) was included as control strain. For the analysis of the cohemolytic activity (CAMP) of RTX toxins (19) we used a beta-hemolytic Staphylococcus aureus expressing the sphingomyelinase and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 3 reference strain ATCC 27090 (S1421) secreting only ApxIIIA. Strains were grown either on Columbia Agar Base (Oxoid Unipath, Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) or on 5% sheep blood agar plates at 37°C overnight.

TABLE 1.

Swine isolates analyzed in this study

| Strain no. | Isolation no. | RTX operon | CAMP | Origin | Pathological finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aerogenes | |||||

| ATCC 27883T | − | Intestine | Diarrhea | ||

| JF2011 | P811/97 | − | Intestine | Diarrhea | |

| JF1319 | P1290/94 | pax | + | Placenta | Abortus |

| JF2118 | P325/98 | pax | + | Placenta | Abortus |

| JF2006 | P787/97 | pax | + | Fetus | Abortus |

| JF2032 | 99/890 | pax | + | Young piglet | Sepsis |

| JF2034 | 99/968 | − | Intestine | Diarrhea | |

| JF2039 | P894/97 | − | Liver | Sepsis | |

| JF2142 | P542/98 | − | Intestine | Diarrhea | |

| JF2072 | P28/98 | − | Liver | Sepsis | |

| JF2101 | 99/1449 | − | Intestine | Diarrhea | |

| JF2185 | P772/98 | − | Bronchus | Pneumonia | |

| JF2154 | P577/98 | − | Bronchus | Pneumonia | |

| A. pleuropneumoniae | |||||

| ATCC 27089a | apxII, apxIII | + | Lung | Pleuropneumonia | |

| ATCC 27090b | apxII, apxIII | + | Abscess | Periarticular abscess |

Serotype 2 reference strain S1536.

Serotype 3 reference strain S1421.

Escherichia coli K-12 strains DH5α and HMS174 were used for gene cloning and expression, respectively. Strain JF522 harboring the hlyBD secretion genes on the plasmid pLG575 (29) was used in the CAMP test of recombinant pax constructs. All Escherichia coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani broth supplemented, when necessary, with ampicillin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), or a combination of both for selection and maintenance of plasmids.

Probe preparation.

Broad-range probes for RTX gene detection, leading to the discovery of a potential RTX gene in P. aerogenes, are described elsewhere (26). The apxIIICA and apxIIIBD probes from A. pleuropneumoniae were described previously (17). For generation of specific P. aerogenes paxCA, probe primers PAX14 (5′-ATTCGGGGATAACCATGCAC-3′; positions 306 to 325 on paxC) and PAX10 (5′-CGCACCACTTAATTCACGAG-3′; positions 2055 to 2035 on paxA) were used. For the paxBD-specific probe, primers PAX4 (5′-CTGGGATAAACAGCTAGCAAG-3′; positions 1077 to 1097 on paxB) and PAX15 (5′-TAACGTAAGCTGTTTGTCACG-3′; positions 925 to 945 on paxD) were used.

All probes were generated by PCR with digoxigenin-labeled dUTP (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The labeling reaction was carried out in a 50-μl volume containing 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 20 pmol of primer (each), 1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.5 nmol of digoxigenin-11–dUTP, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), and 100 ng of genomic DNA. PCR conditions for the pax-specific probes were 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 54°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s.

DNA extraction and Southern blot.

Extraction of genomic DNA was done by using either the QIAamp Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Basel, Switzerland) or the method of Pitcher et al. (31). Chromosomal DNA was digested by restriction enzyme, size separated on a 0.7% agarose gel, and vacuum transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) by using an LKB 2016 VacuGene Vacuum Blotting Pump (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology AB, Bromma, Sweden).

Hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled probes was done according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) in a rotating hybridization oven. Posthybridization washing steps were performed at middle stringency, defined as twice for 5 min at room temperature in 2× SSC–0.1 % sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and twice for 15 min at room temperature in 0.2× SSC–0.1 % SDS (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.01 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0). Chemiluminescent detection with CDP Star (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) as a substrate was done by using X-ray films.

Cloning and DNA sequence analysis.

Chromosomal DNA of P. aerogenes JF1319 and plasmid pBluescriptII SK(−) were digested with corresponding restriction enzymes. Fragments were extracted from gel by using the Jetsorb Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Genomed, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany). After ligation, transformation of E. coli K-12 strain DH5α was done by the CaCl2 procedure (2). Plasmid DNA was extracted by the alkaline lysis method (4), treated with RNase, and purified by phenol-chloroform extraction or by use of the Qiagen Miniprep Kit (Qiagen).

Sequential exonuclease III-generated deletions of cloned genes for subsequent DNA sequence analysis were carried out by using the double-stranded Nested Deletion Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Pharmacia Biotech, Dubendorf, Switzerland).

Sequencing was done by dye terminator-labeled fluorescent cycle sequencing by using Prism reagents and an ABI310 automated sequencer (PE Biosystems, Norwalk, Conn.). All sequences were edited on both strands by using the Sequencher program (GeneCodes, Ann Arbor, Mich.). Sequence comparisons were done by using BLAST (1).

Analysis of 16S rRNA genes.

All strains investigated were tested genetically for their phylogenetic relationship by sequencing a 1.4-kb fragment of the 16S rRNA gene (rrs) as described previously (25). The rrs gene was amplified by using the universal 16S primers 16SUNI-L (5′-AGAGTTTGATCATGGCTCAG-3′) and 16SUNI-R (5′-GTGTGACGGGCGGTGTGTAC-3′). PCR was performed with a PE9600 automated thermal cycler with MicroAmp tubes (PE Biosystems) by using a polymerase with proofreading activity in order to avoid artifacts in the DNA sequences. The reaction was carried out in a 50-μl volume containing 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 20 pmol of primer (each), 1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 2.5 U of Pwo DNA polymerase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), and 100 ng of genomic DNA as a template. PCR conditions were as follows: 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 54°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s. A final extension step for 7 min at 72°C was included. The PCR product was subsequently purified with the PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and sequenced as described above by using the set of primers described elsewhere (25).

Recombinant pax clones and CAMP test.

Recombinant plasmids harboring either paxCA genes or the entire paxCABD operon were generated by PCR with the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) by using genomic DNA of JF1319 as a template. Plasmid pPaxCA was constructed by using primers paxCA-L (5′-GGACTAGTAGACATAAAAAAATACCAAT-3′; positions −95 to −76 on paxC) and paxCA-R (5′-CCGCTCGAGCATATTAGGATTGCTATTA-3′; positions 33 to 15 bp after the paxA stop codon), and plasmid pPaxCABD was constructed by using primers paxCA-L and paxBD-R (5′-CCGCTCGAGGTTTGATCTTCTACAAAT-3′; positions 21 to 4 bp after the paxD stop codon). After amplification the PCR products were digested with SpeI and XhoI and cloned into the corresponding sites of plasmid pBluescript II SK(−).

The CAMP test for cohemolytic activity (9) was performed on 5% sheep blood-agar plates by using a beta-hemolytic Staphylococcus aureus strain as described previously (19). The CAMP reaction was done with erythrocytes from different species. Blood was aseptically taken from swine, rabbits, horses, and humans in the presence of Alsever's solution. Agar plates were then prepared by overlaying Blood-Agar-Base (Oxoid, Hampshire, England) plates with Trypticase soy agar (BBL Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) supplemented with 0.1% CaCl and 5% blood.

Expression of histidine-tailed fusion protein and mouse immunization.

Primers PAXHIS-L (5′-GGACTAGTTGGTCTGCAATATGGGGTAAG-3′; positions 93 to 113 on paxA) and PAXHIS-R (5′-CGCGGATCCTTTTCCCTCTGGATCA-3′; positions 132 to 114 on paxB) were used to generate a PCR fragment from paxA. This fragment, containing the border between paxA and paxB genes, including the paxA-specific stop codon, was cloned in frame into the SpeI/BamHI site of the pET-His vector. The recombinant histidine-tailed PaxA, missing the first 31 amino acids (aa) was expressed in E. coli HMS174. The culture was grown to an optical density at 650 nm of 0.5, induced with 10 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 2 h, and then harvested. Cells were centrifuged 10 min at 2,500 rpm, and the pellet was dissolved in a 1/10 solution of sonication buffer (NaH2PO4 50 mM; NaCl, 300 mM) and sonicated in a Branson Sonifier 250 by using the microtip for 2 min, with an output control of 1 with cooling on ice. Sonicated cells were centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 rpm, and the pellet was dissolved in 20 ml of 6 M guanidinium-HCl–0.1 M NaH2PO4–0.01 M Tris (pH 8.0) and incubated overnight with gentle shaking at 4°C. The dissolved sonication pellet was centrifuged 20 min at 10,000 rpm, and the supernatant was loaded onto a 2.5-ml Ni-nitriloacetic acid-agarose column (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) which was prewashed with 10 ml of H2O and 10 ml of 6 M guanidinium-HCl–0.2 M acetic acid and then equilibrated with 2 × 10 ml of 6 M guanidinium-HCl–0.1 M NaH2PO4–0.01 M Tris (pH 8.0). The loaded column was washed with 10 ml of 6 M guanidinium-HCl–0.1 M NaH2PO4–0.01 M Tris (pH 8.0) and then eluted with 10-ml aliquots of elution buffer (8 M urea, 0.1 M NaH2PO4, 0.01 M Tris) at pH values of 8.0, 7.0, 6.0, 5.0, and 4.5. Fractions of 1 ml were collected and analyzed on an SDS-gel. Fractions containing the histidine-tailed PaxA were pooled, dialyzed against TE (0.1 M Tris, 1 mM EDTA; pH 7.5), and used for mouse immunization.

Nucleotide accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences were deposited under GenBank accession numbers U66491 (ATCC 27883T), U66492 (JF1319), AF139577 (JF2011), AF139578 (JF2118), AF139579 (JF2006), AF139580 (JF2032), AF139581 (JF2034), AF139582 (JF2039), AF139583 (JF2142), AF139584 (JF2072), AF139585 (JF2101), AF139586 (JF2185), and AF139587 (JF2154). The sequence of the pax operon is deposited under accession number U66588.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing the pax operon.

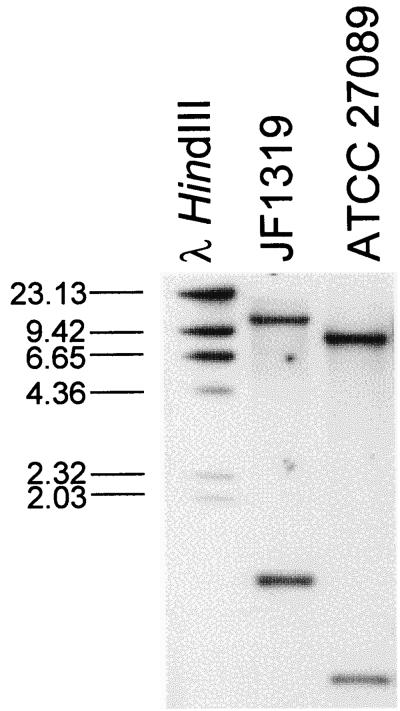

Based on the observation that a P. aerogenes field isolate (JF1319) hybridized with a set of broad-range DNA probes for the detection of RTX toxin genes (26), we characterized the hybridization signal in more detail. The strongest hybridization was seen with a subset consisting of the apxIIIA-derived gene probe. Genomic DNA of P. aerogenes JF1319 and of the A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 2 reference strain ATCC 27089 (S1536), used as a control for the apxIII operon, was digested with EcoRI and blotted onto nylon membranes. Southern blots were subsequently hybridized with a probe specific for apxIIICA (Fig. 1). In the control strain A. pleuropneumoniae ATCC 27089 this results in the detection of two bands as expected from the sequence of the apxIIIA operon. One band at 730 bp resulted from a fragment containing the 3′ half of apxIIIC and a short part of apxIIIA. The other band at 9 kb covers the 3′ part of apxIIIA as well as the two genes apxIIIB and apxIIID, coding for the secretion proteins. In P. aerogenes JF1319, two bands were observed which clearly differed from apxIII. The bands were located at 1.3 and ca. 11 kb, suggesting a different gene (Fig. 1). When an apxIIIBD-specific probe was used, the 11-kb band of P. aerogenes also hybridized analogous to the 9-kb band of A. pleuropneumoniae (data not shown). This shows that P. aerogenes also contains RTX secretion genes B and D and suggests the presence of a complete RTX operon.

FIG. 1.

Southern blot of P. aerogenes and A. pleuropneumoniae with apxIIICA as probe. Genomic DNA of P. aerogenes JF1319 from a swine abortion case and A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 2 reference strain ATCC 27089 (S1536) was digested with EcoRI. After electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel and transfer to nylon membrane, the filter was hybridized with the digoxigenin-labeled apxIIICA-derived probe.

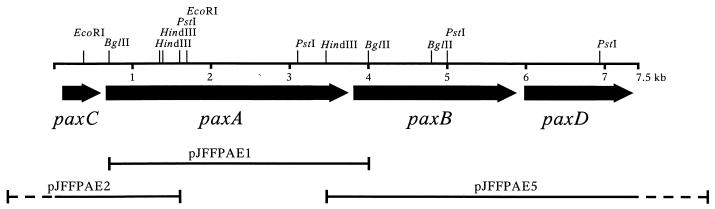

The genes of the putative RTX determinant of P. aerogenes field isolate JF1319 were cloned and sequenced. For this purpose a 3.3-kb BglII fragment hybridizing to the apxIIICA probe was cloned into the BamHI restriction site of plasmid pBluescriptII SK(−) resulting in pJFFPAE1. This clone was used as a probe to find additional fragments covering the RTX operon. Thereby a 2.8-kb PstI fragment and a 5.5-kb HindIII fragment were cloned, resulting in pJFFPAE2 and pJFFPAE5, respectively. By using subclones of these basic clones and by using in addition the primer walking method we were able to sequence the complete operon in both directions. The new RTX operon was named pax (for P. aerogenes RTX toxin) in accordance with nomenclature of RTX toxins (18). Accordingly, the gene encoding the potential structural RTX toxin paxA, the gene for the activator paxC, and the two genes coding for putative secretion genes paxB and paxD. A map of the pax operon, which shows the characteristic features of RTX operons, and the basic clones used for its sequence determination are shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Restriction map of pax operon from P. aerogenes JF 1319 and positions of the different clones used for determination of its sequence. The black arrows represent the four genes in the pax operon, with the arrowheads showing the direction of transcription.

Characterization of the pax operon.

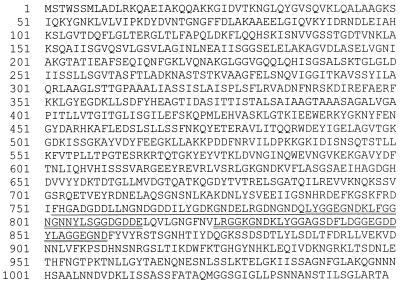

The paxC gene is 510 bp long coding for a putative 169-aa (17.5-kDa) activator protein. It shows 82% similarity to the apxIIIC gene. The paxA gene is 3.15 kb long, encodes a presumed 1,049-aa toxin of 107.5 kDa and also shows 82% similarity to apxIIIA. The deduced protein sequence of PaxA (Fig. 3) contains seven characteristic glycine-rich nonapeptide repeats based on the consensus L/I/ F-X-G-G-X-G-N/D-D-X (36). Four similar repeats precede these classical patterns. The potential secretion protein genes paxB, which spans 2,136 bp and codes for a calculated 711-aa protein of 73 kDa, and paxD, which encodes a presumed 477-aa protein (49 kDa), are also present on the operon and show typical features of ABC transporters. The paxB gene is 83% similar to apxIIIB, the paxD gene 82% similar to apxIIID. Table 2 summarizes the similarities of the pax DNA and amino acid sequences with RTX genes described in other Pasteurellaceae and the alpha-hemolysin of E. coli.

FIG. 3.

Amino acid sequence of PaxA. The seven consensus glycine-rich nonapeptide sequences are double underlined. The four preceding similar nonapeptide repeats are underlined.

TABLE 2.

Similarity of the nucleotide and amino acid sequence of Pax proteins and their genes to other RTX determinants in Pasteurellaceae and to Hly of E. coli

| Locus | DNA or protein | % Identity (DNA) or % similarity (protein)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PaxC | PaxA | PaxB | PaxD | ||

| ApxI | DNA | 63 | 63 | 74 | 70 |

| Protein | 72 | 76 | 94 | 80 | |

| ApxII | DNA | 67 | 62 | ||

| Protein | 78 | 80 | |||

| ApxIII | DNA | 82 | 82 | 83 | 83 |

| Protein | 91 | 94 | 97 | 95 | |

| Lkt | DNA | 63 | 65 | 74 | 68 |

| Protein | 76 | 82 | 93 | 81 | |

| Plkt | DNA | 63 | 65 | 74 | 67 |

| Protein | 81 | 82 | 93 | 82 | |

| Aalt | DNA | 68 | 60 | 72 | 64 |

| Protein | 74 | 73 | 91 | 78 | |

| Hly | DNA | 66 | 62 | 71 | 61 |

| Protein | 74 | 78 | 94 | 78 | |

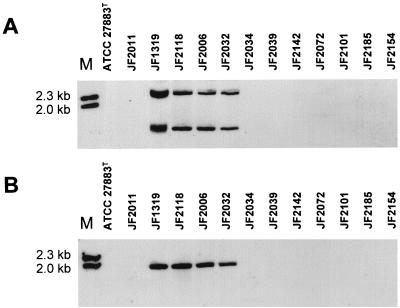

Presence of pax in P. aerogenes strains.

In order to determine the prevalence of pax in this species, all P. aerogenes strains (Table 1) were screened for pax by Southern blots with PstI-digested genomic DNA and probes specific for paxCA and paxBD. The results in Fig. 4 show the characteristic bands for the pax operon in four P. aerogenes strains isolated from abortus cases or from a young piglet with septicemia originating from geographically distant farms and isolated in different years (JF1319, JF2118, JF2006, and JF2032). The P. aerogenes type strain, as well as the resting eight strains that were isolated from clinical material of pathologies other than abortus, did not show any signal with the pax-derived gene probes (Table 1).

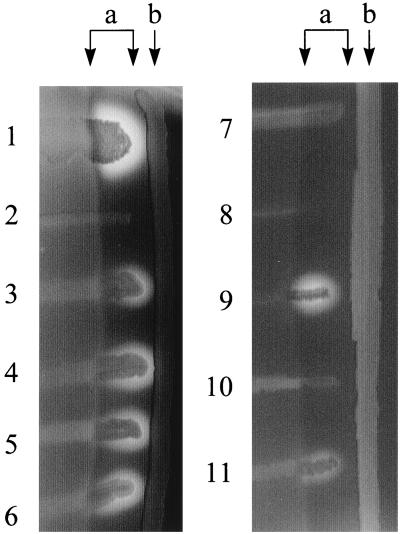

FIG. 4.

Southern blot of P. aerogenes strains. Genomic DNA of the type strain ATCC 27883T and 12 clinical isolates was digested with PstI, electrophoresed on 1% agarose gel, and transferred to nylon membranes. (A) Hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled paxCA derived probe. (B) Hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled paxBD-derived probe. M, λHindIII marker, showing the 2.3- and the 2.0-kb fragments.

Identification of P. aerogenes by sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene (rrs).

Since the phenotypic identification of P. aerogenes has shown to be sometimes ambiguous, we further identified all strains selected for this study by sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (rrs). A few strains which were initially identified by phenotypic methods to be P. aerogenes were revealed by the sequence data to be other species of the family of Pasteurellaceae and were thus not included in this study. Among the P. aerogenes strains isolated from clinical material, variations in the rrs sequences ranged from two to six different nucleotides (<0.5% variation) compared to the type strain rrs sequence. Some strains showed ambiguous bases at a few positions, indicating the presence of more than one rrs operon. Strains JF2011, JF2154, and JF2039, as well as strains JF1319 and JF2118, had identical sequences. By comparison of our sequence of the type strain with the one previously deposited by others (accession number M75048), we could resolve all of the unidentified bases in the latter. In addition, we detected three differences between sequence M75048 and our sequence of the type strain (U66491).

Functional analysis of the PaxA toxin.

Since paxA-containing P. aerogenes did not show direct hemolytic activity on sheep and swine erythrocytes, we performed the CAMP test (9) for cohemolytic activity of this new RTX protein. Cohemolytic activity is known to be associated with Apx toxins, including ApxIIIA (19, 22). For this purpose all P. aerogenes strains were grown in the vicinity of a beta-hemolytic S. aureus. As a CAMP-positive control for RTX toxins we used the A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 3 reference strain. This strain only secretes the nonhemolytic, but CAMP-positive, cohemolytic ApxIIIA which shows hemolysis only in the diffusion zone of the shingomyelinase of S. aureus. Whereas all four pax-positive isolates produced a clear hemolytic zone comparable to the ApxIIIA control, none of the pax-negative strains showed a CAMP effect (Fig. 5 and Table 1).

FIG. 5.

CAMP test with P. aerogenes isolates and recombinant E. coli K-12 strains. Strains were grown in the vicinity of S. aureus (b). The diffusion zone of the sphingomyelinase is also indicated (a). The four pax-positive P. aerogenes isolates JF1319 (lane 3), JF2006 (lane 4), JF2032 (lane 5), and JF2118 (lane 6) show a distinct zone with complete hemolysis, as does A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 3 reference strain ATCC 27090 (lane 1). The P. aerogenes type strain (lane 2), which does not contain the pax operon, shows no CAMP effect. The CAMP effect in P. aerogenes is due to the presence of pax, as shown with an E. coli K-12 DH5α transformed with the plasmid pPaxCABD containing the complete functional operon (lane 9). Neither the DH5α wild-type strain (lane 7) nor the strain containing only paxCA genes on plasmid pPaxCA (lane 8) show the CAMP reaction. A mild CAMP effect is also seen in E. coli 5K strain harboring the hlyBD genes on plasmid pLG575 and plasmid pPaxCA (lane 11) but not in the control strain containing only hlyBD (lane 10).

In order to prove that the cohemolytic activity is due to PaxA, we constructed two recombinant plasmids containing either the entire pax operon (plasmid pPaxCABD) or only the CA genes (plasmid pPaxCA). E. coli DH5α was then transformed with these plasmids. In addition, strain 5K containing hlyBD genes on a plasmid (29) was transformed with plasmid pPaxCA. The results of using the various clones in the CAMP test are shown in Fig. 5. DH5α becomes CAMP positive when containing the entire pax operon (Fig. 5, lane 9). No CAMP effect is seen with the wild-type E. coli host strain (Fig. 5, lane 7) or the strain containing the vector with the CA genes (Fig. 5, lane 8). On the other hand, strain 5K with hlyBD alone shows no hemolysis (Fig. 5, lane 10) but it becomes cohemolytic if paxCA genes are also present (Fig. 5, lane 11). The less intensive cohemolysis of this last construct might be due to the fact that the hlyBD gene products secrete PaxA less efficiently than does the endogenous paxBD-encoded secretion machinery.

In order to determine whether the cohemolytic CAMP effect was specific to a given host, blood-agar plates prepared with erythrocytes from different species were used. For both RTX toxins, PaxA and ApxIIIA, the cohemolytic zone differed on the various erythrocytes (Table 3). Whereas on sheep blood the cohemolysis was generally more intense, it was less strong on human and rabbit erythrocytes and weak on pig and horse erythrocytes. On pig erythrocytes both PaxA and ApxIIIA showed about the same strength of cohemolysis, while on erythrocytes of the other species PaxA was less active than ApxIIIA.

TABLE 3.

CAMP cohemolytic activity of PaxA and ApxIIIA on erythrocytes of different species

| Blood source | Reactiona with:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pax+P. aerogenes | Pax−P. aerogenes | ApxIII+A. pleuropneumoniae | |

| Human | + | − | ++ |

| Horse | − | − | (+) |

| Pig | (+) | − | (+) |

| Rabbit | + | − | ++ |

| Sheep | ++ | − | +++ |

+++, strong CAMP reaction; (+), distinct CAMP cohemolysis still visible.

Purified recombinant polyhistidine-tailed PaxA protein showed a serological cross-reaction with the ApxIIIA toxin from A. pleuropneumoniae, thus giving further evidence of the close relationship between these two toxins (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

P. aerogenes is known to belong to the normal intestinal flora of swine, as well as to act as an opportunistic pathogen (21, 30). Human cases of infection are rare and may occur after being bitten or gored by swine or via dog and cat bites or scratches. Due to its dual role as normal flora and an opportunistic pathogen, its pathogenicity is poorly understood and difficult to investigate. One study was done by inoculating mice with different strains of P. aerogenes. The various strains affected the mice heterogeneously, and two of the ten strains tested led to death after 24 h (33).

Despite its recognition as a mainly opportunistic pathogen, there are sporadic reports of P. aerogenes as a pathogen in abortion cases. Already in the first description of P. aerogenes, McAllister and Carter (30) describe an abortion case as the only clinical finding where P. aerogenes was involved as a primary pathogen. Other cases of abortion in swine were later reported by Hommez and Devriese (21), as well as by Fodor et al. (13). Thorsen et al. (Letter, Lancet 343:485–486, 1994) recently published a case report of human abortion due to P. aerogenes.

We report here the identification of a new RTX toxin gene, paxA, and its corresponding cohemolytic phenotype, which associates with specific P. aerogenes strains isolated from abortion cases in swine or from septicemia of young piglets. Other P. aerogenes strains which were isolated from different clinical samples of pigs with uneven pathological findings were devoid of the pax operon and did not produce CAMP cohemolysis.

The pax operon shows high similarity to the apxIII operon of A. pleuropneumoniae. Due to its high similarity (94%) to ApxIIIA and due to its immunological relatedness to ApxIIIA the activity of PaxA could be similar. ApxIIIA is nonhemolytic but strongly cytotoxic for alveolar macrophages and neutrophils (16) and shows a cohemolysis with the S. aureus sphingomyelinase known as the CAMP reaction (19). The same cohemolytic effect was observed with P. aerogenes harboring the pax operon, whereas none of the pax-negative isolates showed the CAMP effect. The cohemolytic CAMP reaction of PaxA was observed on erythrocytes from different hosts. This finding is in agreement with other hemolytic or cohemolytic RTX toxins for which also no host specificity as determined by erythrocyte lysis was found.

We could demonstrate that the cohemolytic activity in P. aerogenes is specifically caused by the presence of the pax operon (Fig. 5). Transforming E. coli K-12 with the entire pax operon was sufficient to convert this CAMP-negative strain into a CAMP-positive one. The same phenotype conversion was observed when transforming only the paxCA genes into a K-12 strain containing functional genes for the hly-specific secretion proteins (hlyBD) but not when the paxCA genes alone were present. This shows that PaxA must be secreted via a type I secretion system to exert its activity. This set of experiments shows further that the PaxA protein can be secreted not only by its own paxBD-encoded secretion system but also by the secretion system encoded by the hlyBD genes of the E. coli alpha-hemolysin operon. Nevertheless, the CAMP effect in the latter (Fig. 5, lane 11) seems weaker than in the strain harboring the entire pax operon. This could be the result of a less-efficient secretion of paxA via the hly secretion pathway compared to its own specific pathway.

Interestingly, no consensus sequence for a ribosomal binding site can be found in front of any of the four genes of the pax operon. However, the cloned paxCABD operon, including a region of approximately 100 bp upstream the first gene paxC, was well expressed in the functional protein in E. coli hosts, resulting in the characteristic CAMP effect.

The CAMP cohemolytic activity has also been described for other Pasteurellaceae which are known pathogens as Pasteurella haemolytica (15) (now Mannheimia haemolytica), Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (23), or Pasteurella granulomatis (35) (now Mannheimia granulomatis). The precise role of the cohemolytic activity of the PaxA toxin has still to be established. However, the CAMP effect serves as a useful test that will allow investigators to rapidly differentiate PaxA-toxigenic strains from other P. aerogenes and to study the role of PaxA-producing P. aerogenes in abortion in swine.

A detailed genotypic study of the rrs sequence of all strains allowed us to confirm solidly the species P. aerogenes for all strains used in this study. A few strains which were initially identified phenotypically as P. aerogenes were revealed to be other Pasteurellaceae after 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis and were thus excluded. This revealed the importance of genotypic verification of the species P. aerogenes, since unambiguous identification of the species P. aerogenes by phenotypic means seems to be hampered by certain biochemical reactions. Comparison of the 16S rRNA (rrs) gene sequences of the 13 P. aerogenes strains included in this study revealed only minor variation in its rrs genes, i.e., <0.5%. This is within the range of intraspecies variation (10, 14). Based on their rrs sequence, all strains map at the very same position on the phylogenetic tree of Pasteurellaceae described by Dewhirst et al. (12). There was no correlation between the presence of the pax operon and the 16S rRNA gene sequences, which raises the hypothesis that pax might not be clonal and therefore could be located on a relatively mobile DNA. It could thereby be lost or acquired by certain P. aerogenes strains. This would help to explain the ambiguous role of P. aerogenes as a pathogen leading to severe complications such as abortus or septicemia of newborn piglets in certain cases due to PaxA-toxigenic strains and as a bacterium of low epidemiologic impact in many other circumstances (nontoxigenic strains). In this respect the detection of pax could be an indicator for virulent representatives of this species. The role of PaxA in abortion remains speculative for the moment. Nevertheless, since RTX toxins are known inducers of cytokines such as interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor, they are thought to have an immunomodulating effect (11). Therefore, it is conceivable that in the special immune status of pregnancy this modulating effect could finally lead to abortion.

In summary, the new RTX toxin PaxA is the first potential virulence factor described in P. aerogenes. PaxA showed cohemolytic activity in the CAMP test. This simple diagnostic test allows researchers to differentiate PaxA-toxigenic P. aerogenes from other, probably less virulent P. aerogenes strains. Since PaxA and its operon paxCABD was specifically found in P. aerogenes isolated from cases of abortion or septicemia in newborn piglets, we speculate that PaxA is involved in the virulence of P. aerogenes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Y. Schlatter and M. Krawinkler for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grant 5002-38920 from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bercovier H, Perreau P, Escande F, Brault J, Kiredjian M, Mollaret H H. Characterization of Pasteurella aerogenes isolated in France. In: Kilian M, Frederiksen W, Biberstein E L, editors. Haemophilus, Pasteurella, and Actinobacillus. London, England: Academic Press AP; 1981. pp. 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burrows L L, Lo R Y. Molecular characterization of an RTX toxin determinant from Actinobacillus suis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2166–2173. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2166-2173.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang Y F, Ma D P, Shi J, Chengappa M M. Molecular characterization of a leukotoxin gene from a Pasteurella haemolytica-like organism, encoding a new member of the RTX toxin family. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2089–2095. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2089-2095.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang Y F, Shi J R, Ma D P, Shin S J, Lein D H. Molecular analysis of the Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae RTX toxin-III gene cluster. DNA Cell Biol. 1993;12:351–362. doi: 10.1089/dna.1993.12.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang Y F, Young R, Struck D K. Cloning and characterization of a hemolysin gene from Actinobacillus (Haemophilus) pleuropneumoniae. DNA. 1989;8:635–647. doi: 10.1089/dna.1.1989.8.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christie R, Atkins N E, Munch-Petersen E. A note on a lytic phenomenon shown by group B streptococci. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1944;22:197–200. doi: 10.1038/icb.1945.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clayton R A, Sutton G, Hinkle P S, Jr, Bult C, Fields C. Intraspecific variation in small-subunit rRNA sequences in GenBank: why single sequences may not adequately represent prokaryotic taxa. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:595–599. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-3-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czuprynski C J, Welch R A. Biological effects of RTX toxins: the possible role of lipopolysaccharide. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:480–483. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)89016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dewhirst F E, Paster B J, Olsen I, Fraser G J. Phylogeny of 54 representative strains of species in the family Pasteurellaceae as determined by comparison of 16S rRNA sequences. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2002–2013. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.6.2002-2013.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fodor L, Hajtos I, Glavits R. Abortion of a sow caused by Pasteurella aerogenes. Acta Vet Hung. 1991;39:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox G E, Wisotzkey J D, Jurtshuk P., Jr How close is close: 16S rRNA sequence identity may not be sufficient to guarantee species identity. Int J Syst Bact. 1992;42:166–170. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-1-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraser G. The hemolysis of animal erythrocytes by Pasteurella haemolytica produced in conjugation with certain staphylococcal toxins. Res Vet Sci. 1962;3:104–110. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frey J. Exotoxins of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. In: Donachie W, Lainson F A, Hodgson J C, editors. Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, and Pasteurella. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frey J, Beck M, Vandenbosch J F, Segers R P A M, Nicolet J. Development of an efficient PCR method for toxin typing of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae strains. Mol Cell Probes. 1995;9:277–282. doi: 10.1016/s0890-8508(95)90158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frey J, Bosse J T, Chang Y F, Cullen J M, Fenwick B, Gerlach G F, Gygi D, Haesebrouck F, Inzana T J, Jansen R, Kamp E M, Macdonald J, MacInnes J I, Mittal K R, Nicolet J, Rycroft A N, Segers R P A M, Smits M A, Stenbaek E, Struck D K, Vandenbosch J F, Willson P J, Young R. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae RTX-toxins: uniform designation of haemolysins, cytolysins, pleurotoxin and their genes. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1723–1728. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-8-1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frey J, Kuhn R, Nicolet J. Association of the CAMP phenomenon in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae with the RTX toxins ApxI, ApxII and ApxIII. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;124:245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frey J, Meier R, Gygi D, Nicolet J. Nucleotide sequence of the hemolysin I gene from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3026–3032. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3026-3032.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hommez J, Devriese L A. Pasteurella aerogenes isolations from swine. Zentbl Vet Med B. 1976;23:265–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1976.tb00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansen R, Briaire J, Kamp E M, Gielkens A L J, Smits M A. The CAMP effect of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae is caused by Apx toxins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;126:139–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilian M. The haemolytic activity of Haemophilus species. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1976;84:339–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1976.tb01950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolodrubetz D, Dailey T, Ebersole J, Kraig E. Cloning and expression of the leukotoxin gene from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1465–1469. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.5.1465-1469.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhnert P, Capaul S, Nicolet J, Frey J. Phylogenetic positions of Clostridium chauvoei and Clostridium septicum based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:1174–1176. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhnert P, Heyberger-Meyer B, Burnens A P, Nicolet J, Frey J. Detection of RTX toxin genes in gram-negative bacteria with a set of specific probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2258–2265. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2258-2265.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lester A, Gernersmidt P, Gahrnhansen B, Sogaard P, Schmidt J, Frederiksen W. Phenotypical characters and ribotyping of Pasteurella aerogenes from different sources. Zentbl Bakteriol Int J Med Microbiol. 1993;279:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo R Y, Strathdee C A, Shewen P E. Nucleotide sequence of the leukotoxin genes of Pasteurella haemolytica A1. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1987–1996. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.1987-1996.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackman N, Nicaud J M, Gray L, Holland I B. Genetical and functional organisation of the Escherichia coli haemolysin determinant 2001. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;201:282–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00425672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAllister H A, Carter G R. An aerogenic Pasteurella-like organism recovered from swine. Am J Vet Res. 1974;35:917–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitcher D G, Saunders N A, Owen R J. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guanidium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scheftel J M, Rihn B, Metzger M P, Frache P, Marx D, Monteil H, Rohr S, Escande F, Minck R. Infection d'une plaie par Pasteurella aerogenes chez un chasseur après blessure due a une charge de sanglier. Med Mal Infect. 1987;17:267–268. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheftel J M, Rihn B, Metzger M P, Monteil H, Obry F, Escande F, Minck R. Incidence de Pasteurella aerogenes chez le gibier en Alsace. Med Mal Infect. 1987;17:462–464. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thigpen J E, Clements M E, Gupta B N. Isolation of Pasteurella aerogenes from the uterus of a rabbit following abortion. Lab Anim Sci. 1978;28:444–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veit H P, Wise D J, Carter G R, Chengappa M M. Toxin production by Pasteurella granulomatis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;849:479–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb11101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welch R A, Bauer M E, Kent A D, Leeds J A, Moayeri M, Regassa L B, Swenson D L. Battling against host phagocytes: The wherefore of the RTX family of toxins? Infect Agents Dis. 1995;4:254–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]